Locked Up Far Away

The Transfer of Immigrants to Remote Detention Centers in the United States

I. Summary

I lived in upstate New York for 10 years with my four children and my wife ... ICE said I was deportable because of an old marijuana possession conviction where I never served a day in jail, just paid a fine of $250 ... They took me to Varick Street [detention center in New York City] for a few days and then sent me straight to [detention in] New Mexico. In New York when I was detained, I was about to get an attorney through one of the churches, but that went away once they sent me here to New Mexico.... All my evidence and stuff that I need is right there in New York. I’ve been trying to get all my case information from New York ... writing to ICE to get my records. But they won’t give me my records, they haven’t given me nothing. I’m just representing myself with no evidence to present.[1]

Each year in the United States, several hundred thousand non-citizens[2] (378,582 in 2008) are arrested and detained by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officials. They are held in a vast network of more than 300 detention facilities, located in nearly every state in the country. Only a few of these facilities are under the full operational control of ICE—the majority are jails under the control of state and local governments that subcontract with ICE to provide detention bed space.

Although non-citizens are often first detained in a location near to their place of residence, for example, in New York or Los Angeles, they are routinely transferred by ICE hundreds or thousands of miles away to remote detention facilities in, for example, Arizona, Louisiana, or Texas. Detainees can also cycle through several facilities in the same or nearby states. Previously unavailable data obtained by Human Rights Watch show that over the 10 years spanning 1999 to 2008, 1.4 million detainee transfers occurred. The large numbers of transfers are due to ICE’s broad use of detention as a tool of immigration control, especially after restrictive immigration laws were passed in 2006, and the absence of effective policies and standards to prevent unnecessary transfers.

Any governmental authority holding people in its custody, particularly one responsible for detaining hundreds of thousands of people in dozens of institutions, will at times need to transport them between facilities. In state and federal prison systems, for example, inmate transfers are relatively common, even required, in order to minimize overcrowding, respond to medical needs, or properly house inmates according to their security classifications. Transfers in state and federal prisons, however, are much better regulated and rights-protective than transfers in the civil immigration detention system where there are few, if any, checks. The difference in the ways the US criminal justice and immigration systems treat transfers is doubly troubling because immigration detainees, unlike prisoners, are technically not being punished. But thus far ICE has rejected recommendations to place enforceable constraints on its transfer power.

This report examines the scope and human rights impacts of US immigration transfers. It draws on extensive, previously unpublished ICE data Human Rights Watch obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request, as well as scores of interviews with detainees, family members, advocates, attorneys, and officials. As detailed below, we found that such transfers are even more common than previously believed and are rapidly increasing in number, more than doubling from 2003 (122,783) to 2007 (261,941) and likely exceeding 300,000 in 2008 once the final numbers are in. The impact on detainees and their families is profound.

Transfers erect often insurmountable obstacles to detainees’ access to counsel, the merits of their cases notwithstanding. Transfers impede their rights to challenge their detention, lead to unfair midstream changes in the interpretation of laws applied to their cases, and can ultimately lead to wrongful deportations.

Transfers also take a huge personal toll on detainees and their families, often including children. As one attorney who represents immigration detainees explained:

The transfers are devastating—absolutely devastating. [The detainees] are loaded onto a plane in the middle of the night. They have no idea where they are, no idea what [US] state they are in. I cannot overemphasize the psychological trauma to these people. What it does to their family members cannot be fully captured either. I have taken calls from seriously hysterical family members—incredibly traumatized people—sobbing on the phone, crying out, “I don’t know where my son or husband is!”[3]

Many detainee transfers are unnecessary and the harms avoidable. ICE needs a transfer policy with greater clarity of purpose and protections against abuse. As detailed in the recommendations section below, better transfer standards can be developed with just a few simple reforms.

An agency charged with enforcing the laws of the United States should not need to resort to a chaotic system of moving detainees around the country in order to achieve efficiency. Immigrant detainees should not be treated like so many boxes of goods—shipped to the location where it is most convenient for ICE to store them. Instead, ICE should hold true to its mission of enforcing the laws of the United States and allow reasonable and rights-protective checks on its transfer power.

The Impact of Transfers on Detainees’ Rights

The current US approach to immigration detainee transfers interferes with several important detainee rights. To understand the conditions immigration detainees face, it is instructive to compare their situation to that of federal and state prisoners.

In the US criminal justice system, pretrial detainees enjoy the right, protected by the Sixth Amendment to the US Constitution, to face trial in the jurisdiction in which their crimes allegedly occurred.[4] Immigrant detainees enjoy no comparable right to face deportation proceedings in the jurisdiction in which they are alleged to have violated immigration law, and are routinely transferred far away from key witnesses and evidence in their trials. In all but rare cases a transfer of a criminal inmate occurs once an individual has been convicted and sentenced and is no longer in need of direct access to his attorney during his initial criminal trial. Immigrant detainees can be transferred away from their attorneys at any point in their immigration proceedings, and often are. Finally, transferred criminal inmates can usually be located through a state or federal prisoner locator system, which is accessible to the public and in many cases is updated every 24 hours. There is no similar publicly accessible immigrant detainee locator system, meaning that detainees can be literally “lost” from their attorneys and family members for days or even weeks after being transferred.

All immigrant detainees, however, have the right, protected under US law as well as human rights law, to be represented in deportation and related hearings by the attorney of their choice. Transfers of immigrant detainees severely disrupt the attorney-client relationship because attorneys are rarely, if ever, informed of their clients’ transfers. Attorneys with decades of experience told us that they had not once received prior notice from ICE of an impending transfer. ICE often relies on detainees themselves to notify attorneys, but the transfers arise suddenly and detainees are routinely prevented from or are otherwise unable to make the necessary call. As a result, attorneys often spend days, even weeks tracking down the new location of their clients. Once a transferred client is found, the challenges inherent in conducting legal representation across thousands of miles can completely sever the attorney-client relationship.

Even when an attorney is willing to attempt long distance representation, the issue is entirely within the discretion of immigration judges, whose varying rules about phone or video appearances can make it impossible for attorneys to represent their clients. In other cases, detainees must struggle to pay for their attorneys to fly to their new locations for court dates, or search, usually in vain, for local counsel to represent them. Transfers create such significant obstacles to existing attorney-client relationships that ICE’s special advisor, Dora Schriro, recommended in her October 2009 report that detainees who have retained counsel should not be transferred unless there are exigent reasons.

Still, immigrants who have already retained an attorney prior to transfer are the most fortunate. Detainees are often transferred hundreds or thousands of miles away from their families and home communities before they have been able to secure legal representation. Almost invariably, there are fewer prospects for finding an attorney in the remote locations to which they are transferred. It is therefore not surprising that in 2008, the most recent year for which figures are available, 60 percent of non-citizens appeared in immigration court without counsel.

Although most detained non-citizens have the right to a timely “bond hearing”—a hearing examining the lawfulness of detention (a right protected under US law as well as human rights law)—our research shows that ICE’s policy of transferring detainees without taking into account their scheduled bond hearings often seriously delays those hearings. In addition, transferred detainees are often unable to produce the kinds of witnesses (such as family members or employers) that are necessary to obtain bond, which means that they usually remain in detention.

Once they are transferred, the vast majority of non-citizens must go forward with their deportation cases in the new, post-transfer location. Some may ask the court to change venue back to the pre-transfer location, where evidence, witnesses, and their attorneys are more readily accessible. Unfortunately, for a variety of reasons discussed in this report, it is very difficult for a non-citizen detainee to win a change of venue motion.

Transfer can also have a devastating impact on detainees’ ability to defend against deportation, despite their right to present a defense. Transfer often makes it impossible for non-citizens to produce evidence or witnesses relevant to their defense. In addition, the transfer of detainees often literally changes the law that is applied to them. For example, the act of sending a detainee from one jurisdiction to another can determine whether she may ask an immigration judge to allow her to remain in the United States.

Transfer can pose unique problems for detainees who are minor children, without a parent or custodian to offer them guidance and protection. ICE is required to send these unaccompanied minors as soon as possible to a specialist facility run by the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) that is the least restrictive, smallest, and most child-friendly facility available. Placing children in these facilities is a laudable goal, and one that protects many of their rights as children. Unfortunately, there are very few ORR facilities in the United States. Therefore, children are often transferred even further than their adult counterparts, away from attorneys willing to represent them and from communities that might offer them support. The delays and interference with counsel caused by these long-distance transfers of children can cause them to lose out on important immigration benefits available to them only as long as they are minors, such as qualifying for Special Immigrant Juvenile Status, which would allow them to remain legally in the United States.

Finally, the transfer of immigrants across long distances to remote locations takes a heavy emotional toll on detainees and their loved ones. Physical separation from family members when immigrants are detained in remote locations impossible for their relatives to reach creates severe emotional and psychological suffering.

New Data on Detainee Transfers

Given the serious rights violations that can occur, Human Rights Watch is concerned by the widespread and increasing use of transfers by ICE. Data obtained from ICE by Human Rights Watch for this report and analyzed by the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC) at Syracuse University reveal that transfers have increased sharply in recent years: of the 1.4 million transfers that have occurred between 1999 and 2008, more than half (53 percent) took place in the last three of those 10 years.

The data show a clear link between ICE’s reliance on subcontractors to house immigrant detainees and the burgeoning number of transfers. The majority of detainees are held in numerous state and local jails and prisons that ICE pays to provide bed space. However, whenever these state and local facilities need to free up space for persons accused or convicted of crimes, or whenever they decide housing ICE detainees is undesirable for whatever reason, ICE must move detainees out. As a result, the vast majority of transfers occur through such subcontracted facilities.

Although transfers occur into, out of, and within almost every state in the country, the three states most likely to receive transfers are Texas, California, and Louisiana. The numbers are so high in each of Louisiana and Texas that the federal Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit (which covers Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas) is the jurisdiction that receives the most transferred detainees. Transfers to states covered by the Fifth Circuit are of particular interest to an assessment of the impact of immigration transfers because the circuit court is widely known for decisions that are hostile to the rights of non-citizens and because the states within its jurisdiction collectively have the lowest ratio of immigration attorneys to immigration detainees in the country.

While it is impossible to determine conclusively based on our data whether there is a net inflow of transfers to the Fifth Circuit—and we certainly do not conclude that it is intentional ICE policy to create such an inflow—the data show a large disparity between transfers received in (95,114) and originating from (13,031) the Fifth Circuit state of Louisiana. As detailed below, a detainee whose deportation hearing might have been about to be heard in another jurisdiction may well find out, after transfer to a facility within the Fifth Circuit, that his or her chances of successfully fighting deportation have just evaporated.

ICE Policy

As an agency responsible for the custody and care of hundreds of thousands of people, it is clear that ICE will need to transfer detainees. The question is whether all or most of the 1.4 million transfers that have occurred over the past 10 years were truly necessary, especially in light of how transfers interfere with immigrants’ rights to access counsel and to fair immigration procedures.

Despite such problems, ICE has remained staunchly opposed to limiting its transfer power. According to the agency, any such limits would curtail its ability to make the best and most cost-effective use of the detention beds it has access to across the country. In a time of fiscal downturn in the United States such efficiency concerns are important, but they should never come at the expense of basic human rights. This is especially true for those detainees who have attorneys to consult, defenses to raise in their deportation hearings, and witnesses and evidence to present at trial. Some detainees may not have such issues at stake. But for those who do, the United States government and its immigration enforcement agency should not be allowed to act without restraint.

Due to changes in ICE leadership under the Obama administration, there may be opportunities in the near term for ICE to reduce its increasing reliance on transfers. In August 2009, ICE announced a policy shift to

move away from our present decentralized, jail-oriented approach to a system wholly designed for and based on ICE’s civil detention authorities. The system will no longer rely primarily on excess capacity in penal institutions. In the next three to five years, ICE will design facilities located and operated for immigration detention purposes.[5]

As a part of this plan to create new detention facilities solely for immigration purposes, ICE should strive to reduce transfers. The agency should ensure that the new facilities are under its full operational control and are located close to the places where the majority of detainees are arrested. Agency regulations should be amended to require that the Notice to Appear (NTA) (the document giving the government’s reasons for believing an immigrant is deportable) is filed with the immigration court closest to the location where the detainee is arrested. In addition, new guidelines should be issued by ICE and the Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) so that detainee transfers occur only in instances in which they do not threaten basic human rights. Once ICE’s transfer guidelines are developed, they should be made a part of US federal regulations so that if the guidelines are violated, they can be enforced in court. Finally, Congress should consider making a simple amendment to immigration laws to place a reasonable check on ICE’s transfer authority.

Transfers do not need to stop entirely in order for ICE to respect detainees’ rights. They merely need to be reduced through the establishment of enforceable guidelines, regulations, and reasonable legislative restraints.

II. Recommendations

To place reasonable checks on ICE’s transfer authority:

The United States Congress should amend the Immigration and Nationality Act to:

- Require that the Notice to Appear be filed with the immigration court nearest to the location where the non-citizen is arrested and within 48 hours of his or her arrest, or within 72 hours in exceptional or emergency cases; and/or

The assistant secretary for ICE should:

- Promulgate regulations requiring ICE detention officers and trial attorneys to file the Notice to Appear with the immigration court nearest to the location where the non-citizen is arrested and within 48 hours of his or her arrest, or within 72 hours in exceptional or emergency cases.

- Promulgate regulations prohibiting transfer until after detainees have had a bond hearing.

To reduce transfers of immigration detainees:

The assistant secretary for ICE should:

- Build new detention facilities or contract for new detention bed space in locations that are close to where most immigration arrests occur.

- Ensure that new detention facilities are under ICE’s full operational control, so that the agency is not obliged to transfer detainees from sub-contracted local prisons or jails when the facility so requests.

- Require the use of alternatives to detention whenever and wherever possible.

To address deprivation of access to counsel caused by transfers:

The assistant secretary for ICE should:

- Build new detention facilities or contract for new immigration detention bed space in locations where there is a significant immigration bar or legal services community.

- Revise the 2008 Performance Based National Detention Standards (PBNDS) to require ICE/Detention and Removal Operations (DRO) to refrain from transferring detainees who are represented by local counsel, unless ICE/DRO determines that: (1) the transfer is necessary to provide adequate medical or mental health care to the detainee, (2) the detainee specifically requests such a transfer, (3) the transfer is necessary to protect the safety and security of the detainee, detention personnel, or other detainees located in the pre-transfer facility, or (4) the transfer is necessary to comply with a change of venue ordered by the Executive Office for Immigration Review.

- Amend the “Detainee Transfer Checklist” appended to the PBNDS to include a list of criteria that ICE/DRO must consider in determining whether a detainee has a preexisting relationship with local counsel, and require that ICE/DRO record one or more of the four reasons enumerated above for transfer of a detainee with retained counsel and communicate the reason(s) to that counsel.

- Reinstate the prior transfer standard that required notification to counsel “once the detainee is en route to the new detention location,” and require that all such notifications are completed within 24 hours of the time the detainee is placed in transit.

- Collaborate with the Executive Office for Immigration Review to pilot a project providing low-cost or pro bono legal services to immigrants held in remote detention facilities.

The Executive Office for Immigration Review should:

- Issue guidance for immigration judges requiring them to allow appearances by detainees’ counsel as well as detainees themselves via video or telephone whenever a detainee has been transferred away from local counsel, family members, community ties, or other key witnesses.

To remedy interference with detainees’ bond hearings caused bytransfers:

The assistant secretary for ICE should:

- Amend the Detainee Transfer Checklist appended to the PBNDS to include a list of criteria that ICE/DRO must consider in order to determine whether a detainee has received a bond hearing, or has been found ineligible for such a hearing by an immigration judge, or has consented to transfer without such a hearing.

- Pursue placement of the detainee in alternative to detention programs prior to transfer.

To reduce the interference with detainees’ capacity to defend against removal caused by transfers:

The assistant secretary for ICE should:

- Revise the PBNDS to require ICE/DRO to refrain from transferring detainees who have family members, community ties, or other key witnesses present in the local area unless ICE/DRO determines that: (1) the transfer is necessary to provide medical or mental health care to the detainee, (2) the detainee specifically requests such a transfer, (3) the transfer is necessary to protect the safety and security of the detainee, detention personnel, or other detainees located in the pre-transfer facility, or (4) the transfer is necessary to comply with a change of venue ordered by the Executive Office for Immigration Review.

- Amend the Detainee Transfer Checklist appended to the PBNDS to include designation of one or more of the four reasons enumerated above for transferring detainees away from family members, community ties, or other key witnesses present in the local area.

The Executive Office for Immigration Review should:

- Issue guidance for immigration judges that strongly discourages them from changing venue away from a location where the detainee has counsel, family members, community ties, or other key witnesses, unless the detainee so requests or consents, or unless other justifications exist for such a motion apart from ICE agency convenience. Such guidance should also encourage changes of venue to locations where detainee family members, community ties, or other key witnesses are located.

- Issue guidance for immigration judges that prioritizes in-person testimony, but when such testimony is not possible requires judges to allow video or telephonic appearances by family members and other key witnesses. Any decision to disallow these types of appearances should be noted on the record along with the reason for the decision.

- Issue guidance requiring immigration judges considering change of venue motions to weigh whether a requested change of venue would result in a change in law that is unfavorable to the detainee.

To ensure that transfer of detainees does not interfere with the ability of counsel and family members to locate and communicate with detainees:

The assistant secretary for ICE should:

- Require ICE/DRO to develop a reliable tracking system that enables prompt identification of the location where any detainee is being held.

- Require that local ICE field offices maintain up-to-date information about the location of all detainees in their custody and make that information readily available to family members and attorneys of detainees who inquire about the location of a detainee.

- Revise the PBNDS to provide that if a detainee who has been transferred is unable to make a telephone call at his or her own expense within 12 hours of arrival at the new location, the detainee shall be permitted a single domestic telephone call at the federal government’s expense.

To address interference with counsel and other detrimental legal outcomes caused by the transfers of unaccompanied minors:

The assistant secretary for ICE, together with the ORR director, should:

- Provide age-appropriate ORR facilities for all unaccompanied minors near to their counsel or in locations where there is access to counsel, and, in the case of unaccompanied minors who have resided in the United States for longer than one year, their former place of residence in the United States.

To improve agency accountability and management practices as well as accurate accounting of operational costs involved in transfers:

The assistant secretary for ICE should:

- Require detention operations personnel to promptly enter the date of transfer, originating facility, receiving facility, reasons for transfer, and counsel notification into the Deportable Alien Control System, or any successor system used by ICE to track the location of detainees.

- Include costs associated with inter-facility transfers of detainees as a category distinct from transfers made to complete removals from the US in annual financial reporting by the agency.

The Executive Office for Immigration Review should:

- Maintain statistics on the total number of motions to change venue filed by the government versus those filed by non-citizens, and the number granted in each category.

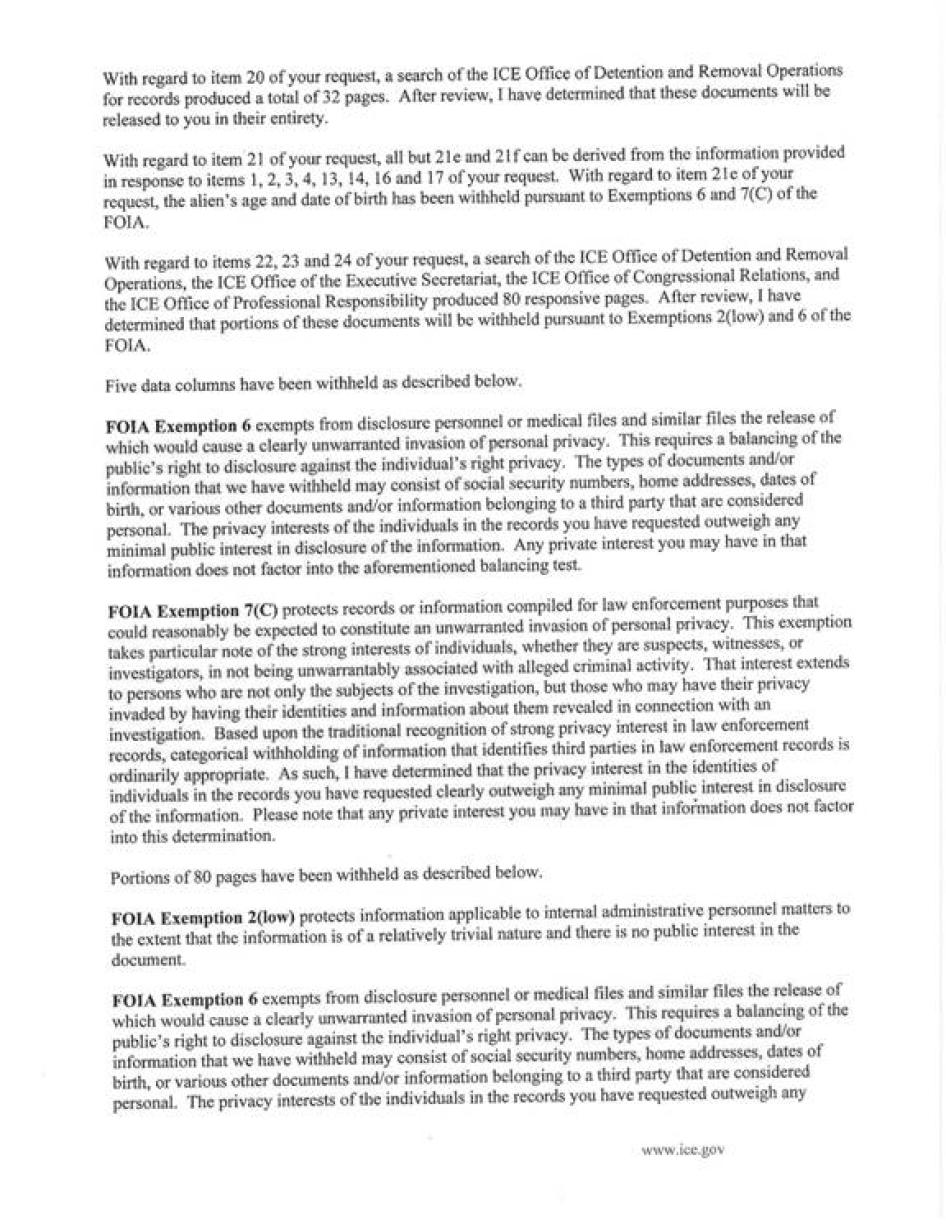

III. Methodology

This report is based on 81 interviews conducted by Human Rights Watch with non-citizen detainees in Texas, Arizona, and New Mexico; detainees’ family members, immigrants’ rights advocates, and attorneys located throughout the United States; and ICE officials located in Washington, DC, Arizona, and Texas. Human Rights Watch also reviewed 158 pages of correspondence between ICE and detainees, their family members, and their congressional representatives, which were produced for Human Rights Watch by ICE in response to our Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request.

The data on transfers (hereinafter “transfers dataset”) were obtained by Human Rights Watch from ICE on September 29, 2008, in response to a request we filed on February 27, 2008, under the Freedom of Information Act.[6] The numbers were analyzed by the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse at Syracuse University.

The files released by ICE contain basic information concerning each exit of a detainee from a detention facility during the period October 1, 1998, through mid-April 2008. This information includes the nationality and gender of the detainee, the facility in which he or she had been detained, the ICE regional hub (known as a “docket control office” or “DCO”), and the dates of entry to and exit from this particular facility, as well as the date on which the immigrant had first been detained. A code also identified the exit reason such as “deported” or “removed,” “voluntary departure,” or “transfer.” However, no information concerning the reason for a transfer was provided.

The first step in TRAC’s research was to develop an analysis database. Initially, this required processing the 68 separate data files that had been released (each containing tens of thousands of records) and combining them into a single database of 3,376,269 records for further analysis. In addition, supplemental translation databases were prepared to map each coded entry to its definition. Consistency checks were also run against available published data. Finally, we checked each record for missing data and for undefined codes to minimize data entry errors.

TRAC also gathered additional information to classify each of the 1,524 detention facilities that appeared in the data. TRAC had previously obtained information on some of the facilities through separate research. For the remaining facilities, TRAC conducted telephone interviews and sought out other publicly available sources identifying the nature of each facility. Using this information each of the detention facilities was classified into broad categories, including “Service Processing Centers” (ICE owned and operated), “Intergovernmental Service Agreement facilities” (state and local jails under contract with ICE), “private contract detention facilities,” “federal Bureau of Prisons facilities” (under contract with ICE), “Office of Refugee Resettlement facilities” (under contract with ICE), and “Detention and Removal Operations juvenile facilities” (ICE owned and operated). Based upon address, each detention facility was also classified by state and by the federal court circuit in which it was located.

Additional analysis variables were then added to the database. For example, using the information on recorded dates, TRAC was able to compute the length of stay in a facility (number of days) and the fiscal year in which the transfer took place. Using this information along with the reasons a detainee was released from (“exited”) a detention facility, TRAC was able to classify records into those facilities where a detainee was placed on the initial day of detention (“originating” facilities) versus facilities to which the detainee was later transferred (“receiving” facilities).

The data also reveal that often a chain of transfers occurred. For example, records show that many immigrants were transferred to a facility and then shortly thereafter transferred out of the facility to another detention location. Unfortunately, it was not possible to match the transfers concerning the same individual because the files for the most part did not identify the particular detainee involved. As a result, while it was possible to classify in aggregate the originating and receiving detention facilities, it was not possible to directly connect the originating and receiving facility on individual transfers since each record only identified the originating detention facility and did not identify the particular facility to which a detainee was transferred.

Once the analysis database was developed, the actual analysis was carried out in two phases. The focus of the first phase was on the detainee population and transfer trends. All records where the exit reason was recorded as a transfer were included in this phase of the analysis. TRAC first examined changes over time in the volume of transfers. Second, TRAC analyzed national origin, gender, and other characteristics of the transferred detainee population and assessed whether there were any significant changes in the make-up of this population over time.

The second phase of the analysis focused upon the geographic location and other characteristics of the detention facilities, for both the originating facility and the receiving facility for the transfer. While it is known that transfers occur for many reasons, there was no information on why an individual transfer took place. For example, a transfer may occur to move a detainee close to the deportation location just prior to the detainee’s removal, or a detention facility may serve only as a convenient stopover between the originating and the intended destination facility. At some locations, ICE has specialized facilities that play a role in the intake process so that on initial pickup an immigrant may pass through more than one detention facility as part of the routine intake process.

While it would have been desirable to exclude these types of transfers from the analysis since they were not the focus of the study, there was no direct way to identify such records because the reason for the transfer was not given. However, it was possible to identify transfers involving “transient” stays—detention facilities in which the immigrant did not remain overnight. As a partial control, the set of receiving detention facilities analyzed in this phase of the research excluded any record where the immigrant arrived and left on the same day (“zero-day stays”) since these types of transfers clearly were outside the focus of this research. Similarly, the set of originating facilities excluded transfers within the same DCO that involved a zero-day stay to reduce double-counting of originating facilities where the intake process during the same day involved multiple facilities.

The resulting sets of originating and receiving detention facilities were then separately analyzed. For each set, facilities were ranked by the volume of transfers. Counts and rankings for originating and receiving detention facilities were also developed by type and by geographic location (state as well as federal court circuit).

IV. The Power to Apprehend, Detain, and Deport

Every day non-citizens in the United States are apprehended by Immigration and Customs Enforcement and placed in a vast network of detention centers that, during the most recent year for which figures are available (2008), housed 378,582 persons.[7] The majority of these non-citizen detainees are held in about 300 state and local jails which, under contract with ICE, receive a daily fee for their bed space. ICE also detains immigrants in nine service processing centers which it operates, as well as in six privately-run contract detention facilities, 42 contracted juvenile facilities, and two family detention centers.

Non-citizens can be apprehended and detained by ICE for a variety of reasons. Many are taken into custody because the legality of their presence in the US is disputed and authorities want to hold them pending a decision on their deportation (or “removal”)[8] from the United States.[9] Authorities also detain non-citizens arriving in the United States without valid travel or identity documents,[10] including those seeking asylum from persecution, who are detained until they have had a “credible fear” interview with an asylum officer.[11] In practice, many such asylum seekers are detained even after they have had a successful credible fear interview and have applied for parole or release from detention under conditions intended to guarantee their appearance at future hearings.[12] Finally, existing laws require authorities to detain most non-citizens who are facing deportation after having served a criminal sentence, including those who are legally in the country (for example, with lawful permanent resident status).[13]

The power to issue a warrant to apprehend and detain any non-citizen pending his or her deportation officially rests with the attorney general of the United States.[14] On a day-to-day basis, that power is exercised by immigration officers. An immigration officer also may question a non-citizen as to his or her right to remain inside the United States, and may take into custody without a warrant any non-citizen believed to be in violation of any immigration law who is “likely to escape before a warrant can be obtained for his arrest.”[15] Finally, the attorney general may enter into a written agreement with local law enforcement officials to arrest and detain non-citizens.[16] In recent years, there has been a marked increase in these agreements with police and sheriff’s departments around the country: In 2007, only eight law enforcement agencies took part in agreements with ICE to enforce immigration laws; now a total of 47 agencies in 17 states participate, with 90 more waiting to sign up as of May 2008.[17]

Once a non-citizen has been detained, the immigration authorities have 48 hours to make a determination as to whether he or she should remain in custody. If the immigration authorities continue to believe that the non-citizen is present in the United States in violation of immigration laws, they must also decide whether to issue a Notice to Appear in that same 48-hour window.[18] The NTA is the document that states the agency’s factual basis for believing an individual has violated the immigration laws, and in most cases, why he or she should be removed from the United States. It is the linchpin for any non-citizen wishing to defend against the government’s claim that he or she should be deported from the United States.

While the NTA must ordinarily be given to the detainee within 48 hours of arrest, that deadline is waived “in the event of an emergency or other extraordinary circumstance in which case a determination will be made within an additional reasonable period of time.”[19] This extraordinary circumstance loophole was most infamously used by the US government in its treatment of immigrant detainees after the September 11, 2001 attacks.[20] It does not appear to be in use today. However, a similar policy remains in effect due to a memo issued in 2004 by then Undersecretary of Border and Transportation Security Asa Hutchinson, which extended the 48-hour deadline for service of an NTA to 72 hours in case of emergency, but also stated that prolonged detention without an NTA is permitted “[w]henever there is a compelling law enforcement need including, but not limited to, an immigration emergency resulting in the influx of large numbers of detained aliens that overwhelms agency resources.”[21]

Under this broad guidance, there is no legally enforceable deadline by which the NTA must be served on the detained immigrant. The lack of a deadline is illustrated by the “many detainees identified by NGOs and attorneys who are sitting in detention for days, weeks, and sometimes months at a time without having received an NTA.”[22]

There is also no deadline for ICE to file the NTA with the immigration court. This absence of a filing deadline is significant because it is only after this filing occurs that the immigration court has jurisdiction over the case. In other words, it is only after the government files the NTA that the place or “venue” for the deportation hearings is set.[23] For example, if an immigrant is taken into custody in Pennsylvania and held there for several weeks before an NTA is filed with the immigration court, and then ICE chooses to transfer him to a detention center in Texas and files an NTA there, his entire legal case has been transferred to Texas.

The fact that the government determines where a particular immigrant’s case will be heard by deciding when and where to file the NTA (for example, waiting until after a transfer has occurred) places a great deal of power in the government’s hands. The power that the government has in determining venue is significant because sweeping changes to US immigration law passed by Congress in 1996 made many more non-citizens subject to deportation, and made it much more difficult for them to defend against their deportation.[24]

The United States Congress should amend the immigration laws, or ICE should issue regulations requiring the agency to file the NTA with the immigration court nearest to the place of arrest and within 48 hours of taking a non-citizen into custody, or within 72 hours in exceptional or emergency cases. These relatively simple legislative or regulatory fixes would provide a measure of necessary control over transfers and enhance fairness in immigration proceedings.

V. Efficient Warehousing: Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s Power to Transfer Detainees

The determining factor in deciding whether or not to transfer a detainee is whether the transfer is required for [ICE’s] operational needs.[25]

Immigration Transfers Compared with Criminal Transfers

Transfers should be expected in any large, multi-institutional system of incarceration. The fact that they occur in ICE facilities is not surprising, nor would it be a cause for alarm if reasonable limits were in place. If the agency worked to emulate best practices on transfers set by state and federal prison systems, it would reduce the chaos and limit harmful rights abuses. Instead, ICE claims an almost unfettered power to transfer detainees at will, resulting in a disorderly system of detainee musical chairs that often violates non-citizens’ rights.

While some detainees are held in the ICE facility or contract facility closest to the place where they are taken into custody, ICE claims the legal authority to transfer immigrants to detention anywhere in the country—from the Dale Correctional Facility in Vermont, to Otero Service Processing Center in New Mexico, and from the Northwest Detention Facility in Tacoma, Washington, to the Oakdale Federal Detention Center in Louisiana. ICE claims that its authority to transfer detained immigrants is contained in section 241 of the Immigration and Nationality Act, which states:

The Attorney General shall arrange for appropriate places of detention for aliens detained pending removal or a decision on removal. When United States Government facilities are unavailable or facilities adapted or suitably located for detention are unavailable for rental, the Attorney General may expend ... amounts necessary to acquire land and to acquire, build, remodel, repair, and operate facilities (including living quarters for immigration officers if not otherwise available) necessary for detention.[26]

This language, which focuses on ICE’s authority to construct detention centers (“more of a bricks and mortar orientation”[27]), does not clearly address ICE’s transfer power. Nevertheless, the provision has been cited by courts as the source of that power, and the interpretation has gone largely unchallenged.[28] The agency claims that “[t]he INA contains no language limiting ICE’s ability to move detainees from one facility to another.”[29] Courts have tended to agree, responding to concerns expressed by detainees about long-distance transfers with relative indifference.[30]

It is hardly surprising that ICE, believing it has limitless transfer powers, pays little attention to a non-citizen’s prior place of residence when deciding where to transfer him or her. Former Assistant Secretary Julie Myers repeatedly emphasized that ICE maintains the discretion to detain people wherever there is bed space.[31] As a result, the government reports publicly that “[d]etainees are often transferred from one facility to another.”[32] Immigrants are treated like so many boxes of goods—shipped to the warehouse with the cheapest and largest amount of space available to store them. One ICE official told Human Rights Watch, “we transfer where beds are available. It’s out of operational necessity.”[33] A report released in October 2009 by Dr. Dora Schriro, special advisor on ICE detention and removal, stated:

Although the majority of arrestees are placed in facilities in the field office where they are arrested, significant detention shortages exist in California and the Mid-Atlantic and Northeast states. When this occurs, arrestees are transferred to areas where there are surplus beds.[34]

In discussions with Human Rights Watch, ICE has claimed that the frequency of detainee transfers and its inability to limit their use is partly related to its arrangements with Intergovernmental Service Agreement facilities (IGSAs), which are state and local jails that contract with ICE to hold detainees. In the case of detainees in the custody of one of these facilities, an ICE official told Human Rights Watch,

They can pick up the phone and say “I want this guy out of here by the end of the day.” We can’t make the facility keep the person, so we have to transfer. We don’t transfer as a punitive measure, we’re not out to get them ... but when a facility requests it, we have to move the detainee out.[35]

Data analysis conducted for this report confirms ICE’s explanation: the majority of detainee transfers originate from the patchwork of local prisons and jails operating under IGSA contracts with ICE. ICE’s haphazard system of placing detainees in a variety of facilities, many of which it has very little control over, helps to explain why its transfer system is equally haphazard.

ICE’s chaotic transfer system stands in marked contrast to operational standards used in state and federal prison systems. Although immigration detainees are not technically being punished, transfers of criminal inmates held in state and federal jails and prisons are more closely regulated than transfers of immigrant detainees held in ICE facilities.

Some of the limits on transfers in the criminal system can be attributed to the Sixth Amendment to the US Constitution,[36] which provides criminal defendants the right to face trial in the jurisdiction in which their crimes are alleged to have occurred. As a result, nearly all criminal defendants are held near the location of their trial, and cannot be transferred while court proceedings are ongoing. The federal Bureau of Prisons’ (BOP) inmate transfer protocol makes explicit mention of the need to coordinate with the federal court system before transfers are implemented. It contemplates that even after the trial is over, criminal defendants may need to be “retained at, or transferred to, a place of confinement near the place of trial or the court of appeals, for a period reasonably necessary to permit the defendant to assist in the preparation of his or her appeal.”[37] The protocol continues:

Ordinarily, complicated jurisdictional or legal problems should be resolved before transfer. Ordinarily, the sending Case Management Coordinator will determine if an inmate has legal action pending in the district in which confined. If so, the individual should not be transferred without prior consultation.[38]

Jeanne Woodford, former director of the California Department of Corrections and former warden at California’s San Quentin State Prison, explains that in California’s prison system:

During trial, most inmates have court holds on them. You cannot transfer an inmate who has a court hold on him or her. The prosecuting authority will come to pick the inmate up for trial.... There should be court holds in the immigration system. It really is very unfair to start a court case in New Jersey and then transfer the inmate to California.[39]

However, there is no system of “court holds” in the immigration system, and the prosecuting authority—the federal government—is of the view that immigrants can be detained anywhere in the United States. In addition, immigrant detainees enjoy no right to face deportation proceedings in the state or locality in which their immigration law violation allegedly occurred. Therefore, as discussed later in this report, immigrant detainees are routinely transferred far away from their attorneys, key witnesses, and evidence in their trials.

Transfers are common in the criminal context once court proceedings have ended, but even then, transfers are often regulated by policy. Acceptable reasons for transfers in the federal prison system arise when a particular inmate needs to be incarcerated at a higher or lower security level, is nearing his or her release date and should be transferred “within 500 miles of his or her release residence,”[40] has medical or psychiatric needs that cannot be addressed at the current institution, needs to participate in a program not offered at the current institution, or needs to be sent “temporarily” to another facility for security reasons (often caused by overcrowding).[41]

Similarly, Jeanne Woodford believes that some transfers in the criminal system are appropriate and necessary

[t]o get people access to facilities that can meet their needs—be they mental health, drug treatment, educational, or vocational training. It’s appropriate to transfer people for medical and mental health needs. It’s often too costly to provide for intensive medical needs in each and every facility and it is better to address some of these needs in one place. Of course, transfers should occur only because the medical treatment cannot be accommodated in the original facility.[42]

Although access to medical care is one of ICE’s stated rationales for detainee transfers, none of the detainees interviewed by Human Rights Watch for this report had been transferred for medical reasons. Similarly, none of the attorneys interviewed for this report recalled ever representing a client who had been transferred to meet his or her medical needs. Indeed, research by our organization and others has documented serious problems with discontinuity in detainees’ medical care due to medications and records failing to follow when a detainee is transferred between facilities. ICE sends only a summary of a detainee’s medical records when sending him or her to one of the state and county jails where ICE rents bed space.[43]

Finally, criminal systems track transfers in computerized databases with much more rigor than ICE. For example, the BOP transfer protocol requires that the reason for transfer and whether or not an inmate is eligible for a parole hearing must be entered into the central computer and approved by superiors prior to any transfer.[44] Most of the information relating to ICE transfers is not uploaded into a centralized system; it is sent with the detainee in hard copy on a series of forms and files. Moreover, the reasons for transfer or eligibility for bond are never tracked.[45] In addition, in marked contrast to ICE’s policies, most prison inmates can be easily located through a state or federal prisoner location system, which is accessible to the public and in many cases is updated every 24 hours.[46] There is no similar publicly accessible immigrant detainee locator system managed by ICE, meaning that detainees can be literally “lost” from their attorneys and family members for days or even weeks after a transfer. The lack of such a locator system prompted ICE Special Advisor Schriro to recommend in her October 2009 report that “ICE should create and maintain a current detainee locator system on the ICE website.”[47]

While it is unrealistic for ICE to completely cease transferring detainees, implementing procedures and controls on transfers akin to those already in place in the criminal context would go a long way toward protecting detainees’ rights. Unfortunately, the agency has refused to do anything more than adopt a vaguely worded and unenforceable set of standards to govern its transfer power.

ICE’s Internal Transfer Standards

In 2000, the Immigration and Naturalization Service (ICE’s predecessor) adopted a set of detention standards to provide minimum safeguards for the fair and humane treatment of detainees.[48] These standards were subsequently revised in June 2004[49] and again by ICE in December 2008 after a lengthy review process that included input from nongovernmental organizations.[50] The detention standards are merely internal agency guidelines and do not have the binding authority of federal regulations or statutory law.

Three subsets of those standards are most important from a rights perspective: first, the standards on permissible reasons for transfer; second, the standards on when and how detainees are to be informed that they are being transferred; and third, the standards on when and how detainees’ attorneys are to be informed that their clients are being transferred.

The 2004 standards provided a vague set of reasons for which ICE may transfer detainees, including medical needs, change of venue, recreation, security, and “other needs of ICE,” which included “various reasons, such as to eliminate overcrowding or to meet special detainee needs, etc.”[51] Nowhere was ICE required to indicate which of these amorphous reasons was motivating a particular transfer decision.

In addition, when a detainee was being transferred in accordance with the 2004 standards, he or she was informed only “immediately prior” to leaving the pre-transfer facility and would “normally not be permitted to make or receive any telephone calls.”[52]Finally, the detainee’s attorney was notified of the transfer only once the detainee was “en route” to the new detention facility.[53]

Because Human Rights Watch believed these vague standards permitted human rights violations to occur, we were pleased to learn that ICE and its department of Detention and Removal Operations were reviewing them and would be issuing a new set of standards in 2008. We brought our concerns to the attention of ICE in a series of letters and through participation in several in-person meetings with senior ICE officials and colleague organizations.[54] Unfortunately, the revised transfer standards issued in December 2008 were almost no improvement over the old.

Once again, although this time even more explicitly, the agency states that its own operational concerns must dictate the transfer decision: “[t]he determining factor in deciding whether or not to transfer a detainee is whether the transfer is required for operational needs, for example, to eliminate overcrowding.”[55] The standards go on to state that detainees may be transferred after taking into account security, legal representation, change of venue, and medical needs.[56]

While operational needs are the “determining factor” and therefore override all other considerations, the inclusion of legal representation as a factor to take into account provides some improvement over the 2004 standards:

ICE/DRO will consider whether the detainee is represented by legal counsel. In such cases, ICE/DRO shall consider alternatives to transfer, especially when the detainee is represented by local, legal counsel and where immigration court proceedings are ongoing.[57]

In addition, the 2008 standards state that “[w]hile ICE/DRO transfers detainees from one facility to another for a variety of reasons, a transfer of a detainee shall never be retaliatory.”[58]

With regard to informing detainees of an impending transfer, the 2008 standards are virtually identical to the 2004 standards, stating that a “detainee shall not be informed of the transfer until immediately prior to leaving the facility.” After being informed, “the detainee shall normally not be permitted to make or receive any telephone calls.”[59]

Finally, the 2008 standards provide attorneys even less notice of their clients’ transfers than the 2004 standards, stating that “the attorney shall be notified of the transfer once the detainee has arrived at the new detention location.”[60] By contrast, the 2004 standards provided that attorneys should be informed once their client was “en route” to the new location. In reality, this distinction has little effect on a detainee’s rights, since in either case the attorney has no chance to petition a court to stop the transfer.[61]

Not only are the 2008 standards unacceptably vague, they are also not codified as federal regulations, and cannot be enforced in court. The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) has refused to turn the standards into regulations, saying that the 2008 standards are preferable to enforceable regulations because they provide the “necessary flexibility to enforce standards that ensure proper conditions of confinement.”[62]

VI. New Data on Frequency and Patterns of Detainee Transfers

In recent years, Human Rights Watch has received numerous anecdotal accounts from immigration attorneys across the country alleging that ICE was transferring immigrant detainees with increasing frequency. However, there were no publicly available data against which we could check these claims. Therefore, in February 2008 we submitted a request to ICE under the Freedom of Information Act seeking detailed information about the agency’s transfer practices since 1998. In September 2008 we received a response.[63] While the agency did not disclose much of the information we had requested, what it did disclose allowed us to analyze quantitatively what we had heard about anecdotally for years.

Trends in the Frequencies and Types of Detainee Transfer

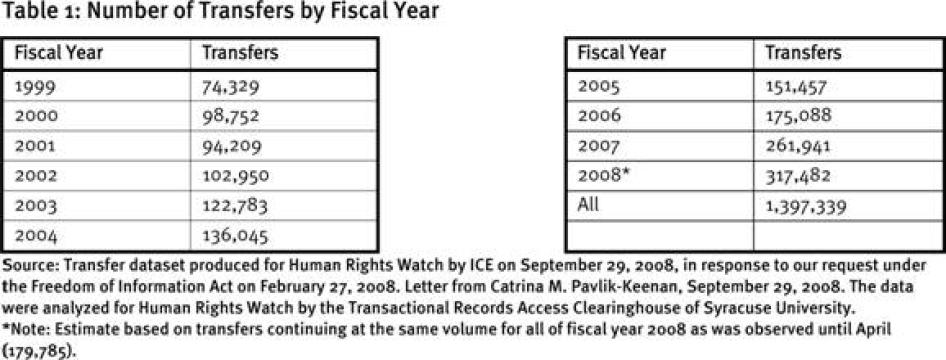

The data reveal that between 1999 and 2008, ICE made 1,397,339 transfers of immigrants between detention facilities. Over those 10 years, the use of transfers has been on the rise, as Table 1 and Figure A show. In 2007, 261,941 transfers occurred, more than doubling the number of transfers (122,783) that occurred just four years earlier in 2003. Since the data produced by ICE for Human Rights Watch record each transfer movement but are not linked to individual detainees, and since our qualitative research has shown that some individual detainees are transferred multiple times, the number of detainees who have experienced transfer is less than the total number of transfer movements.

Figure A: Number of Transfers by Fiscal Year

Source: See Table 1, above.

*Note: Estimate based on transfers continuing at the same volume for all of fiscal 2008 as was observed until April (179,785). This estimate was calculated using a conservative straight-line projection, as opposed to accounting for any exponential growth in transfers.

During the 10 years for which we obtained data, the 20 nationalities most often transferred are shown in Table 2, below. For any given year between 1999 and 2008, these nationalities tended to be the most frequently transferred. Table 3 shows the proportional representation for each of the top 10 nationalities across the 10 years studied.

Table 3: Trends in Nationality of Transferred Detainees, 1999-2008

Nationality |

1999 |

2000 |

2001 |

2002 |

2003 |

2004 |

2005 |

2006 |

2007 |

2008 |

Mexico |

41% |

41% |

38% |

41% |

39% |

36% |

35% |

36% |

36% |

40% |

Guatemala |

6% |

7% |

6% |

8% |

9% |

10% |

13% |

14% |

14% |

14% |

Honduras |

7% |

7% |

7% |

7% |

9% |

8% |

13% |

15% |

14% |

12% |

El Salvador |

8% |

9% |

8% |

7% |

8% |

8% |

9% |

12% |

15% |

12% |

Dominican Republic |

3% |

3% |

3% |

3% |

3% |

3% |

3% |

2% |

2% |

2% |

China |

5% |

5% |

4% |

4% |

2% |

3% |

2% |

2% |

1% |

1% |

Cuba |

5% |

4% |

5% |

4% |

3% |

3% |

1% |

1% |

1% |

1% |

Brazil |

0% |

0% |

1% |

1% |

2% |

5% |

5% |

1% |

2% |

1% |

Jamaica |

3% |

2% |

2% |

2% |

2% |

2% |

1% |

1% |

1% |

1% |

Colombia |

1% |

1% |

3% |

2% |

2% |

2% |

1% |

1% |

1% |

1% |

Source: See Table 1, above.

We were interested in whether particular nationalities were transferred more or less frequently than their proportion of the detained population would suggest. As illustrated by Table 4, during 2008, nationals from Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras made up larger proportions of the transferred detainee population than their proportional time spent in detention would indicate. Mexicans had the largest disparity (8 percent) between their percentage of total transfers and percentage of bed days in detention.

Table 4: Nationalities in detention compared with transfers, 2008

Country |

Percent of total bed days in detention |

Percent of total transfers |

Mexico |

32% |

40% |

El Salvador |

11% |

12% |

Guatemala |

10% |

14% |

Honduras |

10% |

12% |

Dominican Republic |

3% |

2% |

China |

2% |

1% |

Brazil |

2% |

1% |

Jamaica |

2% |

1% |

Cuba |

< 2% |

1% |

Colombia |

< 2% |

1% |

Sources: See Table 1; Department of Homeland Security, Office of Immigration Statistics, “Immigration Enforcement Actions: 2008,” July 2009, http://www.dhs.gov/xlibrary/assets/statistics/publications/enforcement_ar_08.pdf (accessed November 5, 2009), p. 3.

As with nationality, the gender of persons transferred also remained relatively constant between 1999 and 2008. For any given year, female detainees made up between 9 and 11 percent of the persons transferred, averaging 10 percent across the 10 years studied, as shown in Table 5, below.

Table 5: Gender of Transferred Detainees, 1999-2008

Gender |

1999-2008 |

All |

1,397,339 |

Male |

1,254,698 |

Female |

142,459 |

Unknown |

182 |

Source: See Table 1, above.

Geographic Patterns in Detainee Transfers

To examine the geographic patterns in detainee transfers, records were classified into two groups—those pertaining to detention facilities originating transfers and those pertaining to facilities receiving transfers. Details on the classification process are provided in the methodology section of this report.

Limitations in the information ICE released did not permit analysis of flows of detainees between specific pairs of facilities. This was because while a transfer record showed the detention facility a particular detainee originated from, it did not identify the facility to which he or she was transferred. And because the identity of the detainee was not provided, it was not possible to match up records on the originating and receiving detention facilities for a given transfer. In addition, it is known that a significant portion of transfers take place between facilities in the same state. For these reasons, we cannot assess how many transfers originating in a particular state actually left that state, nor can we assess how many transfers received in a state began from a location outside of that state.

Over the 10 years studied (1999-2008), the following two tables show the states in which detainee transfers originated (Table 6), and the states that received transferred detainees (Table 7). These tables show that there is a great deal of transfer traffic originating in and going to Arizona, California, Florida, Pennsylvania, and Texas. However, Louisiana is far more likely to receive transferred detainees than it is to originate transfers, and California, New Jersey, New York, and Oregon are more likely to originate transfers than they are to receive transferred detainees.

Table 6: States Originating Transfers, 1999-2008

State |

Detainee Transfers Originated |

Rank |

|

State |

Detainee Transfers Originated |

Rank |

TX |

168,106 |

1 |

|

OH |

5,114 |

28 |

CA |

153,320 |

2 |

|

KS |

4,764 |

29 |

AZ |

106,416 |

3 |

|

NE |

4,622 |

30 |

FL |

45,572 |

4 |

|

AR |

4,003 |

31 |

PA |

26,082 |

5 |

|

MN |

3,113 |

32 |

NY |

24,224 |

6 |

|

NM |

3,007 |

33 |

OR |

19,576 |

7 |

|

IN |

2,729 |

34 |

NJ |

18,503 |

8 |

|

WI |

2,667 |

35 |

NC |

16,602 |

9 |

|

SC |

2,650 |

36 |

IL |

13,621 |

10 |

|

OK |

2,630 |

37 |

LA |

13,031 |

11 |

|

RI |

2,505 |

38 |

VA |

12,672 |

12 |

|

MT |

2,492 |

39 |

CO |

11,327 |

13 |

|

SD |

2,208 |

40 |

TN |

11,321 |

14 |

|

NH |

1,793 |

41 |

GA |

10,600 |

15 |

|

VI |

1,787 |

42 |

WA |

10,137 |

16 |

|

CT |

1,685 |

43 |

MO |

9,810 |

17 |

|

ME |

1,546 |

44 |

MI |

9,551 |

18 |

|

VT |

1,349 |

45 |

UT |

9,100 |

19 |

|

AK |

1,326 |

46 |

PR |

7,578 |

20 |

|

WV |

1,249 |

47 |

KY |

7,243 |

21 |

|

WY |

1,148 |

48 |

MD |

6,643 |

22 |

|

ND |

1,048 |

49 |

MA |

6,523 |

23 |

|

MS |

799 |

50 |

AL |

6,517 |

24 |

|

HI |

539 |

51 |

ID |

5,974 |

25 |

|

GU |

69 |

52 |

NV |

5,626 |

26 |

|

DE |

10 |

53 |

IA |

5,394 |

27 |

|

DC |

5 |

54 |

Source: See Table 1, above.

Table 7: States Receiving Transfers, 1999-2008

State |

Detainee Transfers Received |

Rank |

|

State |

Detainee Transfers Received |

Rank |

TX |

166,628 |

1 |

|

ID |

5,313 |

28 |

CA |

99,556 |

2 |

|

IA |

5,026 |

29 |

LA |

95,114 |

3 |

|

NC |

4,175 |

30 |

AZ |

85,551 |

4 |

|

UT |

3,619 |

31 |

PA |

43,598 |

5 |

|

OK |

2,974 |

32 |

FL |

42,319 |

6 |

|

AR |

2,082 |

33 |

IL |

29,505 |

7 |

|

CT |

2,062 |

34 |

GA |

25,929 |

8 |

|

RI |

1,869 |

35 |

WA |

17,714 |

9 |

|

KY |

1,757 |

36 |

AL |

16,858 |

10 |

|

IN |

951 |

37 |

CO |

16,567 |

11 |

|

ME |

685 |

38 |

VA |

15,317 |

12 |

|

MT |

673 |

39 |

MI |

14,173 |

13 |

|

SD |

531 |

40 |

NY |

11,510 |

14 |

|

NH |

518 |

41 |

NJ |

9,975 |

15 |

|

SC |

488 |

42 |

NM |

9,925 |

16 |

|

ND |

422 |

43 |

OR |

9,503 |

17 |

|

NV |

413 |

44 |

WI |

9,223 |

18 |

|

VT |

242 |

45 |

MD |

8,570 |

19 |

|

MS |

217 |

46 |

MA |

8,240 |

20 |

|

AK |

136 |

47 |

MO |

8,134 |

21 |

|

WY |

58 |

48 |

PR |

7,722 |

22 |

|

GU |

34 |

49 |

TN |

7,650 |

23 |

|

WV |

31 |

50 |

NE |

7,169 |

24 |

|

DE |

23 |

51 |

MN |

6,979 |

25 |

|

HI |

20 |

52 |

KS |

6,941 |

26 |

|

DC |

16 |

53 |

OH |

5,870 |

27 |

|

VI |

3 |

54 |

Source: See Table 1 above.

Tables 8 and 9 below show that the facility most likely to originate transfers is the Florence Staging Facility in Arizona, while the facility most likely to receive transfers is the Mira Loma Detention Center in California. The tables also show that certain facilities, such as Laredo Contract Detention Facility and Port Isabel SPC in Texas, frequently originate transfers, but are not in the top 20 receiving facilities, while Eloy Federal Contract Facility in Arizona and Pine Prairie Correctional Center in Louisiana frequently receive transfers but are not in the top 20 originating facilities.

Table 8: Top Facilities Originating Transfers, 1999-2008

Facility |

Number |

Rank |

Florence Staging Facility (AZ) |

63,288 |

1 |

Los Cust Case (CA)* |

52,274 |

2 |

Laredo Contract Det. Fac. (TX) |

46,602 |

3 |

Port Isabel SPC (TX) |

31,112 |

4 |

Harlingen Staging Facility (TX) |

27,690 |

5 |

Mira Loma Detention Center (CA) |

20,823 |

6 |

Krome North SPC (FL) |

17,210 |

7 |

Corrections Corporation of America (CCA)—San Diego (CA) |

16,041 |

8 |

CCA, Florence Correctional Center (AZ) |

14,218 |

9 |

El Centro SPC (CA) |

13,705 |

10 |

Florence SPC (AZ) |

13,610 |

11 |

Varick Street SPC (NY) |

11,991 |

12 |

Mecklenburg (NC) County Jail (NC) |

10,496 |

13 |

San Pedro SPC (CA) |

9,346 |

14 |

Kern County Jail (Lerdo) (CA) |

9,291 |

15 |

York County Jail (PA) |

8,091 |

16 |

El Paso SPC (TX) |

7,343 |

17 |

Orleans Parish Sheriff (LA) |

6,124 |

18 |

Tucson INS Hold Room (AZ) |

6,106 |

19 |

Willacy County Detention Center (TX) |

4,767 |

20 |

Source: see Table 1, above.

*Note: While the codebook provided to Human Rights Watch does not clarify what this facility code refers to, and TRAC was unable to clarify through its own research, we hypothesize that it might refer to individuals held in the custody of the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department.

Table 9: Top Facilities Receiving Transfers, 1999-2008

Facility |

Number |

Rank |

Mira Loma Detention Center (CA) |

30,987 |

1 |

York County Jail (PA) |

27,728 |

2 |

Eloy Federal Contract Facility (AZ) |

27,674 |

3 |

Florence Staging Facility (AZ) |

26,789 |

4 |

Pine Prairie Correctional Center (LA) |

26,268 |

5 |

Tensas Parish Detention Center (LA) |

26,205 |

6 |

South Texas Detention Complex (TX) |

25,375 |

7 |

San Pedro SPC (CA) |

24,266 |

8 |

Houston Contract Detention Facility (TX) |

21,583 |

9 |

Willacy County Detention Center (TX) |

19,528 |

10 |

Oakdale Federal Detention Center (LA) |

16,287 |

11 |

Florence SPC (AZ) |

15,796 |

12 |

Denver Contract Detention Facility (CO) |

14,202 |

13 |

Stewart Detention Center (GA) |

13,358 |

14 |

Etowah County Jail (AL) |

12,106 |

15 |

Los Cust Case (CA)* |

11,976 |

16 |

Port Isabel SPC (TX) |

11,014 |

17 |

Krome North SPC (FL) |

10,868 |

18 |

Bradenton Detention Center (FL) |

9,401 |

19 |

Tri-County Jail (IL) |

8,090 |

20 |

Source: see Table 1, above.

*Note: For a description of this code, see Table 8, above.

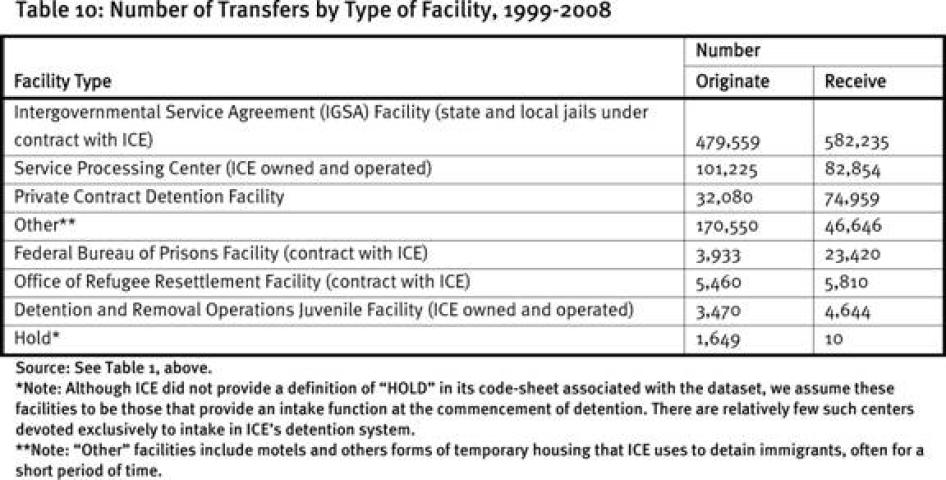

There are also trends in the types of facilities originating and receiving transfers. The majority of detainees are held in numerous state and local jails and prisons that ICE pays to provide bed space under Intergovernmental Service Agreements (IGSAs). Table 10, below, shows that IGSAs originate and receive by far the most transferred detainees. This finding is not surprising because ICE must move detainees out whenever state and local subcontractors need to free up space for persons accused or convicted of crimes, or whenever they decide housing ICE detainees is undesirable for whatever reason.

Since transfers between facilities often occur across large distances, they can have the effect of altering the law applied to a detainee’s case, which is determined by the federal circuit court of appeals with jurisdiction over the facility where the detainee is housed. The following table shows the federal circuits with jurisdiction over the detention centers most likely to originate and receive detainee transfers. As Table 11 shows, facilities within the Ninth Circuit are the most likely to originate transfers, although facilities within the Ninth Circuit also receive a very large number of transferred detainees. Facilities within the Eleventh Circuit are more likely to receive detainees than they are to originate transfers, while facilities within the Fourth, Sixth, and Second Circuits are more likely to originate detainee transfers than they are to receive them.

Table 11 also shows that detention facilities within the Fifth Circuit (a federal circuit known for legal precedent hostile to the rights of immigrants)[64] are most likely to receive transfers, although facilities located in the Fifth Circuit also originate a large number of transfers. While it is impossible to determine if there is a net inflow of transfers to the Fifth Circuit, our interviews tend to indicate that a number of detainees from other jurisdictions end up there. Moreover, the data show a large disparity between transfers received in (95,114) and originating from (13,031) Louisiana. Therefore, while this report does not conclude that there is an intentional ICE policy of transferring detainees to the Fifth Circuit, it appears that for at least one of the three states within the Fifth Circuit’s jurisdiction, there is a significant inflow of detainees from elsewhere.

Transfers can also have a serious impact upon detainees’ access to counsel. As Table 12 shows, in many cases detainees are transferred to circuits with relatively few immigration attorneys. In order to obtain a rough idea of the number of immigration attorneys in a particular circuit, we obtained the number of members of the American Immigration Lawyers Association (AILA) by state.[65] Since not all immigration attorneys are members of AILA, and not every member of AILA is a practicing immigration attorney, these numbers can only provide a rough indication of the distribution of immigration attorneys in the various circuits. Table 12 shows that the circuit most likely to receive detainees, the Fifth Circuit, has the worst (highest) detainee/attorney ratios; whereas the circuits least likely to receive detainees—the Second and the DC Circuits—have the best (lowest) detainee/attorney ratios.

Table 12: Transferred Detainee to Immigration Attorney Distributions

Circuit |

Rank by Number of Detainee Transfers Received 1999-2008 |

AILA Members as of August 2009 |

Transferred Detainee to AILA Member Ratio |

5th |

1 |

934 |

280.47 |

10th |

5 |

388 |

103.31 |

3rd |

4 |

600 |

89.33 |

9th |

2 |

2642 |

82.86 |

8th |

7 |

436 |

69.59 |

11th |

3 |

1283 |

66.33 |

7th |

6 |

634 |

62.59 |

6th |

8 |

629 |

46.82 |

1st |

10 |

516 |

36.89 |

4th |

9 |

801 |

35.68 |

2nd |

11 |

1507 |

9.17 |

DC |

12 |

321 |

0.05 |

Sources: see Tables 1 and 10, above. AILA membership totals provided to Human Rights Watch by AILA on August 31, 2009.

Finally, in the course of the 10 years studied, 19,384 transfers occurred originating from and going to detention facilities specifically set up to house juveniles. As Table 13 illustrates, certain juvenile detention facilities experience the bulk of transfer traffic: the largest numbers of juvenile detainees are transferred from and to Hutto[66] and IES in Texas, as well as to and from Southwest Key Juvenile Shelter in Arizona, and Barrett Honor Camp in California.

Table 13: Transfer Activity at Juvenile Detention Centers 1999-2008

Facility |

State |

Total Transfer Activity |

Hutto CCA |

TX |

2,722 |

International Emergency Shelter (IES) |

TX |

2,242 |

Southwest Key Juvenile Facility |

AZ |

1,975 |

Barrett Honor Camp |

CA |

1,955 |

Juvenile Facility (Chicago) |

IL |

1,374 |

Southwest Key Juvenile Facility |

TX |

1,046 |

Boystown |

FL |

932 |

Catholic Charities (Houston) |

TX |

569 |

Casa San Juan |

CA |

540 |

Berks County Family Shelter |

PA |

523 |

Southwest Key Juvenile Facility |

CA |

500 |

Gila County Juvenile Detention Center |

AZ |

419 |

Berks County Juvenile |

PA |

400 |

Southwest Key Juvenile Facility (Houston) |

TX |

391 |

Los Padrinos Juvenile Hall |

CA |

385 |

Liberty City Juvenile Detention Center |

TX |

378 |

Southwest Initiatives Group, LLC |

TX |

334 |

Southwest Youth Village |

IN |

251 |

Berks County Secured Juvenile |

PA |

173 |

Corpus Christi Facility |

TX |

143 |

Southwest Key Juvenile (San Jose) |

CA |

129 |

Northern Oregon Juvenile Detention |

OR |

125 |

Alternative House |

TX |

118 |

All |

|

19,358 |

Source: See table 1, above.

Costs of Transfer

ICE provides no publicly available analysis of the savings or costs associated with transfers. It also does not provide information on the rationales for transfers in particular cases, which might help the agency and others to better understand the savings or costs associated with its practices. For example, although none of the detainees interviewed for this report had been transferred for medical reasons, it is certainly the case that some percentage of transfers are completed in order to provide immigrant detainees with necessary medical care, and that providing such care prevents illness, loss of life, and costly lawsuits. However, there is no way to estimate these savings since the agency does not make public, or even record in a centralized database, the reasons for detainee transfers. Even if one accepts the notion that transfers for medical care provide cost savings to the agency, it is also true that transfers for medical care are not adequately addressing detainee medical needs: ICE’s failure to care for the medical needs of non-citizen detainees (resulting in deaths in several cases) has been the subject of numerous lawsuits, prominent newspaper stories, and congressional action.[67]