“We Stood, They Opened Fire”

Killings and Arrests by Sudan’s Security Forces during the September Protests

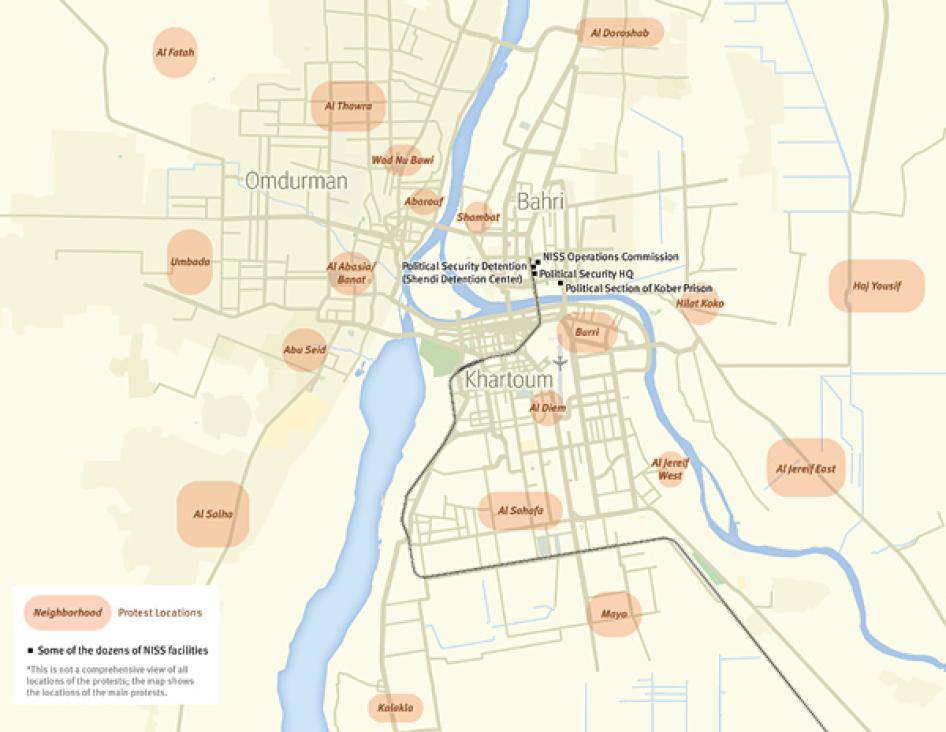

Map of Khartoum and Omdurman, Sudan

Summary

In the last week of September 2013, a wave of popular protests broke out in Wad Madani, Khartoum, Omdurman, and other towns across Sudan after President Omar al-Bashir announced an end to fuel subsidies and introduced other austerity measures. Government security forces responded to the protests with force, including lethal force in the form of live ammunition. More than 170 people, including children, were reported killed in the government response, and hundreds more wounded, arrested and detained, some for weeks or months without charge or access to lawyers or family visits. Detainees, particularly those from Darfur, were subjected to torture and other forms of ill-treatment.

More than six months on, the Sudanese government has yet to investigate or hold accountable those responsible for the killings and other related abuses. Research by Human Rights Watch and other groups indicates that the government took deliberate measures to suppress independent reporting on the events and to prevent families of victims from accessing justice. The government continues to hold activists in connection with the protests in unknown locations, and many families still do not know the whereabouts of their detained relatives.

The Sudanese government’s response to evidence that security forces are responsible for unlawful killings, arbitrary detention, torture, and related abuses has been to deny and minimize the scale of the violence and human rights violations. Although authorities have promised to investigate the allegations, there has been no public evidence of any progress so far to investigate those responsible for the killings and other abuses.

Victims’ families that have sought to have police or prosecutors open cases into the killings of their loved ones have faced obstacles, including refusals to investigate individual cases, as well as refusals to provide key documents such as autopsy reports, preventing them from pursuing justice. Meanwhile Sudan has continued to use excessive force including live ammunition to suppress peaceful protests, resulting in more deaths during protests in the capital in 2014.

This report, based on research conducted between September and December 2013 in-country, interviews via e-mail and telephone, documents some of the most serious abuses that took place during the September protests. The report calls on the Sudanese government to carry out promised investigations, hold those responsible to account, immediately end its use of excessive and lethal force against protestors, and respect and facilitate the right to peaceful assembly and protest. International actors involved in Sudan should break their silence and press for swift action.

Recommendations

To the Government of Sudan

Excessive Use of Force against Protesters

- Law enforcement and security organs in Sudan should not permit forces to use live ammunition against unarmed protesters. All such organs should issue clear orders to their forces that any use of force must be strictly necessary and proportionate to a real and imminent threat, and that use of excessive force will be punished. Resort to lethal force should be limited to specialized units, with the appropriate training, when such force is strictly necessary to save life.

- The Ministry of Justice should complete and make public the results of their investigations into the killings and injuries that occurred during the September and October 2013 protests across Sudan. The investigation should provide a full accounting of the dead and injured, the circumstances surrounding each incident resulting in death or injury, evidence that indicates the extent to which government security forces are implicated in human rights violations, and credible evidence of any third party responsibility for the abuses.

- The Ministry of Interior should ensure that security forces respond to and cooperate with investigations. Legal immunities for any security forces implicated in shooting civilians should be waived by the relevant authorities.

Arbitrary Detentions

- The NISS should immediately release any individual still being held in connection with the protests who have not been brought before a judicial body, lawfully charged with an offence, and remanded by the judicial body to face trial promptly in accordance with international fair trial standards.

- The National Intelligence and Security Services (NISS) should publish the names of all people in detention, identify all places of detention, and ensure relatives, legal counsel, and independent monitors all enjoy access to the detainees.

- The National Assembly should reform the 2010 National Security Act so that it conforms to international law, in particular to ensure that all detainees be brought promptly before a judicial officer to be charged and face a fair trial in a reasonable time or released and that they can effectively exercise the right to challenge the lawfulness of their detention.

Treatment in Detention

- Ensure that conditions of detention conform to the United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners, including those in relation to the detention of minors; permit and facilitate visits by legal counsel, medical personnel and family members.

- Investigate all allegations of mistreatment, torture, and death in detention, and promptly take steps to prosecute and/or discipline any NISS officials, police and other officials responsible for the abuse.

- Publicly and unequivocally condemn the practice of torture and other forms of mistreatment in detention. Take all necessary measures, including instructing the police, armed forces and security personnel to end all mistreatment of detainees, making clear that there is never a justifiable reason for mistreatment, including extracting confessions, retribution for alleged support of rebel groups, or other punishment.

- Ratify the United Nations Convention Against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading and Treatment or Punishment and its Optional Protocol, which allows independent, international experts to conduct regular visits to places of detention.

Freedom of Expression

- Immediately stop all censorship of newspapers and other media outlets in violation of freedom of expression guarantees..

- Take all measures including issuing public orders to security services to end harassment of journalists and human rights defenders and ensure those found responsible for harassment are subject to disciplinary measures or criminal prosecution.

To the African Union, United Nations, European Union and Member States

- All concerned governments should press Sudan to immediately end the use of excessive lethal force against protesters and related human rights abuses, and to hold accountable those responsible for killings and other abuses in connection with the September protests.

- The African Commission on Human and People’s Rights should authorize its own fact finding mission into the allegations of serious human rights violations and continued use of lethal force against protesters and formally request Sudan make public its investigation into the September violations.

- The UN Human Rights Council’s Independent Expert on the situation of human rights in the Sudan should report on the killings and injuries that occurred during the September and October 2013 protests across Sudan, and on the Sudanese government’s response including its investigation and any follow-up steps to provide justice for victims.

- The United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights should press for an OHCHR country office in Sudan to monitor the human rights situation, especially in view of the ongoing use of excessive force against protesters and unlawful detentions.

Methodology

This report is based on in-country and telephone and e-mail research by a Human Rights Watch senior researcher in the Africa Division and three research consultants. The majority of research was conducted between September and December 2013. Researchers interviewed more than 30 people, including family members, witnesses to shooting incidents, former detainees, lawyers, and social activists. Interviews were conducted in English or Arabic in a private setting or using secure communication.

Human Rights Watch also consulted a wide range of secondary resources,

including videos and statements from witnesses compiled by Sudanese groups,

some of which are posted on YouTube and other social media. Researchers

corroborated all such reports with interviews and other evidence.

Many of those interviewed, fearing harassment, arrest, or other forms of reprisals, have requested not to be named, and as a result, many names have been left out.

I. Background

Sudan experienced some of the largest and most intense public protests in years in September 2013. The protests started in Wad Madani, the capital of the Al Gezira state in east-central Sudan the day after a September 22 speech by President Omar al-Bashir in which he announced austerity measures including the end to fuel subsidies.[1] The measures were among Sudan’s responses to the effects of the loss of 75 percent of oil revenue following the independence of South Sudan in 2011.[2]

The demonstrations swiftly spread to the country’s capital, Khartoum, neighboring Omdurman, and other towns including Port Sudan, Atbara, Gedarif, Nyala, Kosti, and Sennar, and continued sporadically into October. The most concentrated period of protests was from September 24 to 29 and the government’s crackdown was the harshest that week, with more than 170 people shot dead and many more injured and arrested.

Many of the protests developed without prior planning. In Omdurman, for example, high school students spontaneously started a demonstration in Al-Thawra al-Shingeti neighborhood on the morning of Tuesday, September 24, chanting, “We are protesting against those who steal our sweat,” and “The people want to topple the regime.” The protests were largely peaceful although during the first few days, in some locations groups of youths damaged property, notably police or other government buildings, vehicles, public transportation, and petrol stations in Khartoum, Omdurman, and Wad Madani. Some demonstrators also burned tires and hurled stones or bricks at security forces.

President al-Bashir and other authorities cited the rioting and destruction as the reason for deploying “well-prepared” armed forces in large numbers as a “Plan B” to suppress protests.[3] Authorities have blamed the Sudan Revolutionary Forces (SRF), the rebel coalition between Darfur groups and the SPLA-North that formed in late 2011, for organizing the September protests, a claim the rebel groups have denied.[4] Sudanese rights activists have alleged the government hired thugs to engage in acts of sabotage and vandalism especially of petrol stations to discredit the protests.[5] Human Rights Watch was not able to confirm either of these allegations.

In an apparent attempt to deter protest, authorities started arresting activists, political opposition party members, and journalists days before protests began.[6] More than 800 people were estimated to have been arrested in connection with the protests. Authorities also censored and confiscated newspapers, arrested people for recording or speaking out about the protests, and blocked the Internet for 24 hours on September 25 and 26.[7] These steps most certainly silenced voices in the country, but many Sudanese citizens evaded the censorship by reporting on events through social media, widely sharing videos of street scenes, lists of those killed and injured, and victims’ descriptions of events.[8]

The scale of the violence and killings of protesters in September was unprecedented in the capital. The most comparable recent use of such force in Khartoum and Omdurman was the 2008 response to a coup attempt by the Sudanese rebel group, Justice and Equality Movement.[9] In Darfur, by contrast, the government has often used lethal force against protesters. On September 19, just days before the fuel subsidy protests, security forces fired at protesters in Nyala, South Darfur, who were demonstrating against a rise in attacks on merchants by pro-government militia. The security forces killed at least seven protesters including two children.[10]

The killing of protesters in Khartoum and Omdurman had a snowball effect, prompting more protests and violence against protesters, including at the funerals for the victims. The government continues to use live ammunition to disperse peaceful protests in the capital. On March 11, 2014, security forces used live ammunition to disperse a group of Darfuri student protesters at Khartoum University, killing one and injuring several. The students were protesting recent government attacks on civilians in Darfur.[11] The police denied the shooting but said they would investigate.

Protests arose within a wider context of pervasive and grave violations of international human rights and humanitarian law.[12] Many Sudanese and international analysts have taken the government’s resort to lethal force in Khartoum and Omdurman as a sign of the National Congress Party’s (NCP) fragile grip on power. The interruption of oil flows following the independence of South Sudan in 2011 had sparked economic protests on a smaller scale, but the party also faced growing dissent over allegations of economic mismanagement and corruption, its protracted wars in Darfur, Southern Kordofan and Blue Nile, and its repression to stifle dissent of any kind.[13]

At the political level, the September protests polarized not only the opposition parties, many of whose members were locked up for weeks or months, but also provoked dissent within the NCP and Islamist movements. In late September, the president’s former adviser, Ghazi Salahuddin al-Atabani, who formed a new Islamist party three months later, condemned the killings and demanded a reversal of the austerity measures in a memo signed by 31 politicians.[14]

The government has not reversed the measures or investigated the killings, but by late October had released the most prominent political detainees. Opposition parties, initially united in condemning the violence,[15] became less vocal with their demands for justice in the following months but various civil society groups have supported the formation of solidarity committees for families of those killed, injured, and detained, to help them seek justice.

Sudan’s political elite remains deadlocked over next steps for Sudan’s political future, including the conduct of elections or adopting a new constitution. On January 27, 2014, al-Bashir gave a widely publicized speech promising policy reform and calling for a national dialogue.[16] On April 6, Bashir ordered the release of “political detainees” in an apparent concession to opponents.[17] However, the political parties have yet to agree on the terms of this process and the government has yet to meet opponents’ demands for more political space and a better enabling environment for such a national political process. At time of writing, activists and students remained in NISS detention in locations across Sudan.

II. Excessive Force against Protesters

Starting September 23 the government responded quickly to the spread of protests and demonstrations by moving large numbers of armed security forces, both uniformed and in plain clothes, to neighborhoods where protests were taking place or expected to take place. Eyewitnesses told Human Rights Watch, other organizations, and media that forces included armed police, riot police, central reserve police, the military, national security forces, and pro-government militia, and that they shot tear gas canisters, rubber bullets, and live bullets into crowds and at protesters.

In Wad Madani, credible sources reported that security forces shot live ammunition into crowds of peaceful protesters on September 23, reportedly killing as many as 12 protesters.[18] In Khartoum and Omdurman, security forces started using live ammunition on September 24. Media reports and witness interviews indicate that September 25 and September 27, a Friday, were the most violent days, on which the highest number of protesters were killed or arrested in both towns.

In early October a Sudanese doctor’s union estimated that more than 210 people were killed just in Khartoum and Omdurman, and hundreds seriously injured.[19] Human Rights Watch was not able to independently verify the figures, still a point of contention. Independent monitoring groups provided credible evidence of 170 deaths, most from shootings to the head and torso.[20] Activists’ lists indicate most were in their late teens and early twenties, but also include elderly people, children, and a two-year-old infant.[21] Some of the shootings of protesters in Khartoum and Omdurman during the week of September23 are described in the sections below.

Under international law, law enforcement may use only such force as is necessary and proportionate to maintain public order, and may only intentionally use lethal force if strictly necessary to protect human life. Although some protesters reportedly hurled stones or bricks at police and destroyed property in some locations, such acts of criminal damage do not justify intentional use of lethal force. International standards also require that governments ensure arbitrary or abusive use of force and firearms by law enforcement officials is punished as a criminal offense.

The government has acknowledged that 87 people died, but officials maintain that saboteurs and rebels used firearms and were responsible for the deaths and injuries.[22] The government has not provided any credible evidence to support these claims, nor has Human Rights Watch independently found or been presented with such evidence.

Human Rights Watch received evidence of the government’s use of live ammunition and that a large number of deaths were caused by gunshot wounds. Forensic evidence showing that many of the protesters sustained gunshot wounds to the head and torso also suggests the shootings were intentional and possibly targeted at specific protesters. In some cases witnesses told Human Rights Watch they recognized the shooter as a member of the security forces, while in other incidents witnesses pointed to circumstantial evidence such as the location of the forces, the sound of gunshots, and the location of victims.

To properly establish criminal responsibility for each of the deaths, the authorities should fulfill their obligation to conduct a thorough investigation that includes examination of all forensic and crime scene evidence, such as complete and detailed autopsy reports, bullet casings, security forces operation reports; eye-witnesses testimony, and the testimony of government security forces who participated in specific operations in each neighborhood.

Unlawful Killings in Khartoum

On September 25, Hazza Eldin Jafar Hassan, age 18, was shot dead during demonstrations near his house in Bahri, Khartoum North. His mother told Human Rights Watch he was shot in the head around 3p.m. by security forces in beige uniforms riding in a white vehicle.[23] A student who participated in the protest with Hazza told researchers he saw several land cruisers carrying security forces wearing camouflage uniforms, approaching the protesters:

The first [vehicles] fired rubber bullets and tear gas on us and the last two [vehicles] fired live bullets. I was standing on the side of the street when I heard the gunshots. I fell on the ground and…after it stopped I looked up to see Hazaa lying on the ground motionless. I crawled to him and flipped him over only to find him soaked in blood. He was bleeding from a gunshot wound to his head. He was already dead.[24]

Hazza’s mother, in a statement posted on YouTube, said family and friends found his body and carried him away amid continued gunshots. “We were carrying the body and still in pain over his death, they were still firing bullets around and tear gas,” she recalled.[25]

According to witnesses, the same evening, as family members and friends gathered for Hazza’s funeral in the Shambat neighborhood, Hazza’s friend Bashir al Nur Hammed, age 20, was shot in the leg and the head, and died on the spot.[26] Though Human Rights Watch could not establish details of the shooting, witnesses said national security forces driving in white vehicles were responsible.

In another example from September 25, armed police forces shot and killed Sara Abdelbagi, a 29-year-old student. She was with other family members outside her uncle’s house in al-Doroshab neighborhood, where they had gathered after hearing that Sara’s 14-year-old cousin, Suheib, had been shot dead by security forces the same day. Sara’s younger sister described the incident:

When we arrived there was a large crowd of women, neighbors and friends outside our uncle’s house. There was agitation, anger. The riot police surrounded us, also some national security agents in plainclothes. Then we heard multiple gunshots and I turned to see Sara. I saw her falling to the ground…bleeding profusely. She was shot in the left side of her stomach near her left kidney.[27]

On September 27, dubbed “Martyr’s Friday” by Sudanese political activists, demonstrations against the killing of protesters started after midday prayers. Dozens were believed to have been killed on September 27, amongst them Dr. Salah al-Din Sanhouri, a 28-year old pharmacist, who was shot in the back during a protest in the Burri neighborhood of Khartoum. Sanhouri’s death became a symbol of the crackdown and rallying cry for anti-government protesters during the protests and in the media.[28]

In Bahri, Khartoum North, on September 27, national security officials shot and killed 20-year-old Osama Mohammadein el Amin while attempting to disperse a large group of protesters marching from toward the North Bahri courts complex. One witness recalled how, after police allowed a protest continue, armed security forces waiting at the complex beat protesters with sticks and shot at the crowd:

The national security officials armed with Kalashnikov rifles and wearing camouflage, riding in four-wheel Toyota Land Cruisers, blocked our way. They threw teargas at us and told us to disperse […]. They started to beat us with sticks. We turned back toward the courts and stayed on the main road. While we were there we heard a gunshot and I saw Osama who was standing in front of me in the middle of the road fall down. He was shot in the head above his left eyebrow. At that time, there were national security agents in plainclothes and police standing in front of the courts. I am not sure who exactly shot him, but the gunshot came from them.[29]

The same day in the Safia area of Bahri, Dr. Samar Mirghani Abu-Naouf, a pharmacist, recorded on her phone the killing of a boy by police officers during protests in her neighborhood. “While I was filming a boy was shot and fell dead right in front of me, around two meters away. I was in a state of shock. I started screaming and I continued filming. I had documented the entire killing of the boy. The officers then approached me and snatched my phone,” she recalled. Shortly after this, officers detained and beat her. (More details in Section IV, below)

In Kelakla, in southern Khartoum, a participant in a peaceful protest outside of al Iskan mosque, Mohammed (not his real name), described getting hit by a bullet. He said he was with 30 others protesting against the price increases when a police car “moved toward us, then went past us, but then a few meters later they immediately fired live bullets.” The group dispersed, then regrouped a half an hour later and started to demonstrate again. “As soon as we got close [to the police], they started shooting at us. I felt numbness in the thigh of my left leg. I saw blood seeping from it and could not run. I just crawled to the first house I could find.” The same witness also saw the shooting of Al Sadiq Abu Zaid Izeldin, age 17, who died of his wound.[30]

A large proportion of reported killings occurred in poorer suburbs like Mayo and Haj Yousif. Among the confirmed killings were Abdullah Yousif Suliman, a 68-year old merchant, wounded by gunshots near Souq Sita, a market in Mayo, who died four days later; and 19-year-old Omar Khalil Ibrahim Khalil and 15-year-old Saleh Sadiq Osman Sadiq, both killed at the Haj Yousif bus station by gunshots to the head on September 25.[31]

Shooting Incidents in Omdurman

Omdurman, one of the three towns that form the capital, Khartoum, saw large popular protests in several neighborhoods starting September 24. As in Khartoum, armed security forces who were deployed to disperse protests opened fire with live ammunition on protesters, killing scores. The following are some confirmed cases:

In al-Fatah, a poor suburb populated largely by Darfuri and Nuba communities, student protests started on September 25 against the rise in fuel prices and living expenses. “No one was carrying anything in their hands apart from their school bags,” a witness told Human Rights Watch. When the protesters reached the police station, uniformed police and community police in plainclothes began firing live ammunition toward the protesters, causing them to disperse.

A short while later, at around 10:30 a.m., one of them fired a round of live ammunition at the protesters and killed a 17-year-old high school student, Mohammed Ahmed al Tayeb. Witnesses identified the shooter as a member of the community police who owned a shop in the neighborhood that was subsequently looted. “After this incident the protesters got angrier and started to throw stones and set fire to tires, and the police responded with bullets,” the witness recalled. Some of the security forces went to the roof of a building and fired at protesters, killing and injuring several more.[32]

In the al-Banat area on the same day, police shot Mosa’ab Mustafa, a 29-year-old painter during a protest. According to witnesses, a crowd of protesters moved toward the police station and police officers shot bullets into the air and tear gas to disperse them. One witness heard one of the police officers say “shoot the long hair,” referring to Mosa’ab:

The policeman [on the right side] then pointed his Kalashnikov toward the crowd and fired a single gunshot. I saw Mosa’ab fall on the ground. He was twitching but then got up again and blood was seeping from his chest. He was gasping for air and walked for one meter before falling again.[33]

Mosa’ab’s father, who described the killing on a video posted to YouTube, said the doctor confirmed that the bullet had entered through his son’s back and exited his chest.[34]

In Althowra, Salaheldin Daoud Mohammed Daoud, a 65-year old amputee who lost his right arm in a car accident in 1966, and advocated for the rights of persons with disabilities, was shot in the knee while doing an errand near his home. In his neighborhood national security officers were shooting at youths, who were throwing bricks and stones. After a lull in the shooting Daoud, left his home, but was then shot in the left knee, requiring amputation of his left leg. “I don’t think they targeted me specifically, but they targeted the youth,” he said.[35]

In Umbada, Wad Nubawi, Aborouf, and other diverse suburbs, many more protesters including young students were reported killed and injured during the week. In Umbada, Nureldin Altayib Nureldin Dahab, age 14, was shot dead on September 25 by guards from the national security who entered the neighborhood in vehicles then chased youths on foot.[36] In Aborouf, on September 25, police fired live bullets at protesters peacefully marching toward the police station, according to a witness who spoke to Human Rights Watch. A bullet hit Ahmed Badawi Osman, in his mid-twenties, in the head, killing him.[37]

Beatings of Protesters

In addition to shootings, security forces also severely beat protestors to disperse or punish them, or while arresting them. In one example from Wad Medani on September 23, Rania Mamoun, a journalist, and her two siblings were arrested during protests, beaten, and detained by security forces for a night at a police station. In a public statement entitled, “A day in hell: my testimony from the arrest,” Mamoun writes:

My brother was hit on the head. I was hit by a large number of soldiers who circled me like flies. The beating was intense and meant to hurt and abuse….They dragged me on the ground and called me all sorts of names then threatened me with gang rape….With the continued beatings I reached the stage where I did not feel pain with every new strike that followed.[38]

In another example on the evening of September 25 during protests in Amarat district of Khartoum, Altayib (not his real name), age 49, was badly beaten by armed national security officers when he tried to intervene in the brutal beating of a 19-year-old boy:

They were dragging [the boy] on the ground and beating him with sticks and their gun butts. I told myself I must do something to rescue this boy. I came closer and told them, ‘Please if he did something wrong, take him to your office and investigate but what you are doing is inhuman.’ Then one of the high-ranking officers replied, ‘Who are you? Are you telling us what to do?’ and ordered me to get inside their pickup truck. Then about six of them grabbed me by the hands and legs and threw me on the back of the truck, then started beating me with sticks and plastic pipes and some were [stomping] on me with their boots.[39]

Yousif el-Mahdi, a political activist, told Human Rights Watch how on September 29 following the funeral for Salah Sanhouri, national security officers arrested and beat him up. “A group of four or five officers in khaki uniforms beat me with their batons then threw me into the back of one of their pick-up trucks. I was made to lay on my front along with a young man who had also been tracked down and beaten,” he recalled.[40]

III. Arrests, Detentions, Ill-treatment and Torture

Before, during, and after the protests, national security officials arrested hundreds of people. By September 27, authorities reported they had already arrested 600 people, while human rights organizations reported over 800 arrests.[41] Although many of the protesters were released within hours or days, often following summary trials resulting in punishment of lashing or fines, large numbers remained in detention for weeks and even months, many without charge or access to family or lawyer visits.

Of those who were legally charged in connection with crimes committed during the September demonstrations, several dozen remained in detention as of late March 2014, including journalist Ashraf Omar Khogli, and four minors who face charges of burning a police station. Sudanese lawyers have called for the release of all remaining detainees held in connection with the protests, and an end to the property crimes trials, which they describe as deeply flawed and in violation of the Child Act of 2010.[42] Human Rights Watch has not independently monitored these cases.

Many others, including youth activists, political party members, journalists, and human rights defenders were arrested because of their perceived anti-government views and role in organizing the demonstrations and were never legally charged. Former detainees reported a common pattern of being arrested often at night from their homes, taken to the nearest NISS office and interrogated, then transferred to a detention facility, either in a NISS building or in the NISS-run wing of a prison in various locations around Sudan. They were held in locations across the country for periods ranging from a few days to weeks or months.[43]

Many of the detainees who spoke to Human Rights Watch reported that they were beaten, verbally abused, and forced to hand over passwords to e-mail or Facebook accounts, and were released only after signing a promise not to participate in protests or other actions against the state. The treatment appeared worse for Darfuris, especially student members of the United Popular Front, a Darfuri student groups linked to the Sudan Liberation Army faction led by Abdel Wahid al-Nur. Some told Human Rights Watch that they had been, or seen others be, subjected to electrical shocks.

Sudan’s NISS operates dozens of official and unofficial detention facilities in Khartoum and Omdurman alone, some in office buildings and others in residential compounds. Many detainees were held at the NISS political headquarters in Bahri. The facility consists of several buildings including one known as “Guantanamo” due to its extreme temperatures, bright lights and reputation for use of torture tactics against detainees held there.[44]

One former detainee, Ahmed (not his real name), age 45, a member of the Communist Party, told Human Rights Watch he was arrested at his workplace in Khartoum on the evening of September 22, before the protests began, and held incommunicado for over a month. After an initial period of intensive beating and interrogation at other NISS places of detention in Omdurman and Khartoum, he said officials transferred him to the NISS political headquarters in Bahri, where he and other detainees were beaten, forced to do the “rabbit hop” and made to sit in a hot courtyard for several hours on his first day in that facility. He was then locked up in an air-conditioned 3x3 cell at very cold temperatures and bright lights and deprived of sleep, decent food, and medical assistance for much of the following four weeks.[45]

Another former detainee, Mohamed Ali Mahamadu, an Al Akhbar newspaper journalist originally from Darfur, was arrested at his workplace and detained from September 28 to December 5, held for much of the time at the Bahri facility. NISS officers first took him to an office in Bahri, where they interrogated him and accused him of leading protests in Umbada, Omdurman and of having contact with rebels from Darfur. They interrogated him for two days, beating him with plastic pipes and kicking him; on the second day he fainted and woke up in a hospital, then later that day taken back to the NISS office. He was held in solitary confinement for over 60 days, subjected to bright lights, death threats and insults such as “you are abed,” [slave] and “sit down you dog,” and beaten at various times. At the time of his release, he estimated more than 80 other detainees were still inside the NISS detention facility and that some of the young Darfuris among them appeared badly tortured.[46]

While treatment in detention varied, depending on the political and social profile of the detainee, in all cases, detainees reported experiencing some form of verbal abuse such as racist and sexist slurs.

Dalia el Roubi, a member of both Sudan Change Now, a youth activist group, and Nafeer, a humanitarian assistance group – both of whose members were targeted for arrested and detention without charge during and after the demonstrations – recalled: “One agent told me, ‘you know Dalia when people like you provide support to slaves you’re sabotaging the country. Don’t you know where all these demonstrations took place? They occurred in the areas full of slaves.’” She explained that “In the morning many agents entered the room and insulted us, ‘Do you think you are decent women? You are wearing trousers. You are street girls.”[47]

In another example, national security officers who arrested female opposition party member taunted, “Why would red people like you [Arabs] open your homes to abeed [slaves]?” Abdelaziz had been hosting a meeting with four Darfuri students in her home in Khartoum at the time of her arrest. The officers arrested everyone in the house, beat the Darfuris, and detained the opposition party member without charge for four days.[48]

Under international law, anyone arrested should immediately be informed of the reason for their arrest and promptly informed of the charges against them and brought before a judicial officer. There is an absolute prohibition on the torture, or other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment of any individual. Detainees are also entitled to family visits and medical treatment, as well as basic decent conditions of detention.

Sudan’s National Security Act of 2010, which permits detention for up to four and a half months without judicial review, violates international standards and should be promptly reformed. Sudan should also uphold the UN minimum standards on conditions of detention, condemn, and prosecute all acts of mistreatment and torture, and ratify the UN Convention Against Torture and its Optional Protocol, which require respect for the prohibition of torture under all circumstances including the investigation and holding to account of anyone responsible for violating the prohibition.

IV. Restrictions on Media and Expression

Sudanese authorities suppressed information about the protests and the violence by censoring the media and arresting and detaining journalists, creating an effective media blackout inside Sudan. Even before the protests, authorities had clamped down on newspapers reporting on the economic situation.[49]

On September 25, the editors of major papers were summoned and ordered not to publish articles related to the demonstrations or rise in fuel prices unless citing police or NISS sources. As a result three daily newspapers suspended their publications from September 25 to 27, while NISS officials confiscated editions of three others.[50]

In Wad Madani, security officers arrested journalist Altigani Ali, who had planned to cover the protests, on September 25. On September 28, authorities arrested journalists Amal Habbani in Khartoum and Abdelatif al-Daw in al-Gadarif, detaining them without charge for several weeks. Authorities also arrested Jaffar Khidir, a known poet and pro-democracy activist in al-Gedarif, on September 24 and 28.[51]

On September 30, at a televised press conference by the Minister of Interior, journalist Burhan Abdelmoniem accused officials of covering up the killings, asking, “why do you insist on lying?”[52] National security officers arrested him on the spot, but released him the same day. Other journalists and bloggers have also told Human Rights Watch that they have been harassed since September in connection with their reporting about the government’s crackdown.[53]

International journalists were also summoned for questioning, and authorities shut down both Sky News Arabia and Al Arabiya TV stations for several weeks.[54] Sudan’s Minister of Information had blamed “foreign media” for inciting unrest.

In addition, on September 25 and 26, much of the country’s networks were shut down, preventing access to the Internet for 24 hours. According to analysis by Access, an independent international monitoring group, “on September 25 and 26 a substantial portion of the country’s networks became unreachable, effectively removing Sudan from the broader Internet at the height of protests in Khartoum. This shutdown occurred on all major data providers (Canar Telecom, Sudatel, MTN Sudan, and Zain Sudan) and appears to have been the result of actions taken by the service providers.”[55] Sudanese rights groups allege that government authorities instructed service providers to suspend service, a claim that Human Rights Watch could not independently corroborate.

Authorities also targeted people who were recording or sharing information or speaking out against the government during the protests. On September 27, security forces arrested Dr. Samar Mirghani and snatched her phone as she was recording the killing of a protester.[56] She was charged with public disturbance crimes and in October sentenced to a fine of 5,000 Sudanese pounds (US$1,000), or jail time.

On the night of September 28 security officers arrested Abdel Fatah al-Rufai, a 65-year-old Communist Party member, from his home because he spoke at a funeral earlier in the week condemning the government’s killing of protesters.[57]

Dr. Osama Murtada, a medical director of Omdurman hospital, was arrested and interrogated after giving an interview to BBC Arabic on September 25 about the number of demonstrators that were killed and injured received at his hospital.[58] In addition, in early October, the head of the Doctor’s Union, Ahmed al-Sheikh, was arrested briefly for reporting on the numbers of casualties, which he estimated at more than 210.[59]

V. Government Response to the Violence

The government responded to protests by sending heavily armed forces to areas where protests were expected. On September 25, the government announced it would deploy the army to protect government buildings and gas stations.[60] The next day, NISS announced the readiness of 2,000 agents “to end the chaos and destruction in the streets of Khartoum.”[61]

Sudan’s First Vice President Ali Osman Taha announced on September 26 the government would not go back on its decision to end fuel subsidies and claimed that they government was not against peaceful demonstrations but “will not tolerate terrorists and saboteurs,” inciting further protests. He also threatened to summon supporters of the ruling party onto the streets in order to “protect public and private property from saboteurs and vandals.”[62]

Authorities explicitly blamed the SRF rebels for plotting the protests and denied that security forces killed any protesters, attributing the violence alternately to homeless people, saboteurs, outlaws, and foreign conspiracy.[63] On October 2, during a military graduation ceremony, President al- Bashir disavowed responsibility for the violence, blaming “unnamed parties” of “seeking to destabilize Sudan and exploiting events for killing, looting and vandalism.”[64]

Authorities continue to deny responsibility for the deaths and injuries, and minimize the number of arrested. On November 6, Taha refuted the figures of those killed. “I can confirm that they are not more than 80 based on criminal records as opposed to the number that has been circulating in the media, which is 220. That number is incorrect,” he said.[65] The government still officially maintains that 84 people were killed.

Failure to Investigate

Sudanese authorities promised to investigate the violence, but to date the investigations have focused on property damage and looting rather than on loss of human life. On September 26, media cited a government petroleum official stating 69 gas stations were affected by the riots with varying degrees of damage, and a public transport company stating that 15 buses were destroyed and 105 partially damaged.[66]

On October 1, the Minister of Interior established a committee to investigate the damage caused to government and private properties during the protests. On November 4, the Minister of Justice, Mohamed Bushara Dousa, promised to investigate the killings.[67]

The government has proceeded with summary trials and dozens of criminal prosecutions of protesters for property damage crimes, but has taken no apparent action to hold accountable those responsible for killing and injuring protesters, or for abuses against detainees.

On December 23 a group representing families of those killed, injured and detained handed a complaint to the Human Rights Commission demanding accountability for those responsible for the killings, the release of all detainees, and for unfair trials to stop. The Commission Chair told the petitioners that she would try to accelerate the government’s investigation, those present told Human Rights Watch. Families again petitioned the Human Rights Commission on March 27. On April 6, the government announced the release of all “political detainees,” (not necessarily related to the September protests) but activists told Human Rights Watch many remain in detention in locations across the country. [68]

In February 2014, following a visit by the UN Independent Expert, the Minister of Justice repeated promises to investigate but no findings have been made public about the protester killings and related abuses.[69]

Obstructions to Justice

Lawyers and family members who tried to pursue justice for the killings described obstacles in obtaining necessary medical documents and lodging criminal claims against perpetrators. Families of deceased and wounded often had trouble obtaining documentation stating a cause of death or describing injuries from morgues or hospitals. Without this evidence police were reluctant to open cases.

Moatassim al-Haj, a lawyer who represents victims’ families, explained, “there are 104 reports of deaths in different police stations in Khartoum during the protests, and about 99 percent have been described in the official reports as “death in mysterious circumstances,” so police do not take any further action.[70]

In the case of Ahmed al-Badawi Osman, killed in the Aborouf neighborhood of Omdurman, for example, family members went to the police station six days in a row to open a case, but were told they could not without a medical report stating the cause of death. The family did not succeed in obtaining a medical report from the hospital, and as a result the police have not opened a case.

Lawyers and activists helping victims’ families told Human Rights Watch that of more than 50 families who tried to bring cases, they only knew of one – brought by the family of Sara Abdelbagi – that had proceeded to trial. In that case, family members and witnesses pressed the police to revise the cause of death after they initially indicated “mysterious circumstances” in order to move the case forward.[71]

Police also simply refused to open investigations, regardless of the evidence, claiming that perpetrators are unknown. In the case of Bashir Musa Ibrahim, killed in Kelakla on September 25, a family member explained: “We went to the police post three times to register a complaint but the police refused to open any complaint for the victim. We still have a desire to proceed with the legal process because there were some witness who told us they saw the police man who shot Bashir.”[72]

Witnesses and lawyers who spoke to Human Rights Watch, as well as other human rights organizations who monitored the situation in the aftermath of the demonstrations, reported that national security officials intimidated and warned families not to try to sue police or security officers for the killings.[73] Some also said that police or security officials had paid or offered to pay compensation. Human Rights Watch could not confirm these allegations.

VI. International Response

The international response to the protester killings was muted, with a few initial statements but no sustained efforts to press Sudan on its promises to investigate the killings and related abuses.

On September 27, the UN Office for the High Commissioner for Human Rights issued a statement expressing “deep concern about the reports that a significant number of people have been killed during the demonstrations across Sudan since Monday,” and called on “all parties to refrain from resorting to violence and on protesters to maintain the peaceful nature of their demonstrations.”[74]

The same day the United States Department of State also issued a statement condemning the “brutal crackdown on protesters in Khartoum” and expressed concern about the arrest and detention of activists and called on the government to “provide the political space necessary for a meaningful dialogue with the Sudanese people.”[75]

On September 30, the European Union’s High Representative also expressed concern over the loss of life, excessive use of force, and detentions.[76] The African Union did not react to the protests, and the UN remained silent except through statements of the UN Independent Expert on the situation in Sudan, Mashood Adebayo Baderin. On October 3, Baderin expressed concern about the large number of arrests and detentions since September 23, and heavy censorship of local media. On February 19, 2014, following a visit to Sudan, he stated: “The international community expects a thorough investigation of the human rights violations that occurred during the September demonstrations,” and noted that the government had informed him that it set up two committees to investigate the September incidents. “I regret to note that five months after these incidents, the committees set up by the Government have not yet issued their reports or findings on the incidents.”[77]

The UN, AU, EU, and member states of those bodies should apply more public and sustained pressure on Sudan to provide accountability for the violence in September and end its continued use of live ammunition against peaceful protesters, unlawful detentions, and media restrictions.

VII. Acknowledgements

This report was researched and written by Jehanne Henry, senior researcher in the Africa division at Human Rights Watch. Leslie Lefkow, deputy director in the Africa division edited and reviewed the report. Aisling Reidy, senior legal advisor, and Babatunde Olugboji, deputy Program director, provided legal and program reviews. Elise Keppler, associate director of the International Justice Program, also reviewed the report. Joyce Bukuru, associate in the Africa division, provided additional editorial assistance. Kathy Mills and Fitzroy Hepkins provided production assistance.

Human Rights Watch wishes to thank the many Sudanese victims and witnesses who confided in researchers, sometimes at great personal risk, to tell their stories, and human rights activists in Sudan who contributed, in various ways, to the production of this report.

[1] See Omar al-Bashir speech September 22, 2013, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l6sIJemkuhU.

[2] Inflation has accelerated dramatically since 2011. See IMF, Sudan: Interim Poverty Reduction Strategy October 2013, para. 24, available at http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/scr/2013/cr13319.pdf.

[3] On October 21, President Omar al Bashir told a Saudi Arabian newspaper that because of the “acts of sabotage and destruction” the government resorted to “plan B,” deploying well prepared forces at the scene of all protests. “The whole story was finished in 48 hours.” See Okaz newspaper, at www.okaz.com.sa

[4] “Sudan’s NCP accuses SRF rebels & opposition of inciting protests,” Sudan Tribune, September 24, 2013, at http://www.sudantribune.com/spip.php?article48167 (accessed March 20, 2014).

[5] Human Rights Watch confidential interview with youth activist, Khartoum, December 14, 2013.

[6] “Dozens Killed During Protests,” September 27, 2013, Human Rights Watch news release, http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/09/27/sudan-dozens-killed-during-protests; “Rising Death toll of peaceful protesters and Internet blackout,” September 26, 2013, Girifna, at http://www.girifna.com/8702 (accessed March 21, 2014).

[7] “Dozens Killed During Protests,” Human Rights Watch news release, September 27, 2013, https://www.hrw.org/news/2013/09/27/sudan-dozens-killed-during-protests.

[8] See, e.g. Girifna, at http://www.girifna.com; Sudan Change Now, at http://www.sudanchangenow.org, and “Abena” Facebook page, at https://www.facebook.com/pages/ابينا-Abena-شهداء-الثورة/517525344992015.

[9] Human Rights Watch, “Crackdown in Khartoum: Mass Arrests, Torture and Disappearances Since the May 10 Attack,” June 2008, http://www.hrw.org/reports/2008/06/16/crackdown-khartoum-0.

[10] “Dozens Held Without Charge,” November 27, 2013, Human Rights Watch news release, http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/11/27/sudan-dozens-held-without-charge-0.

[11] “Renewed Attacks on Civilians in Darfur,” March 21, 2014, Human Rights Watch new release, http://www.hrw.org/news/2014/03/21/sudan-renewed-attacks-civilians-darfur

[12] In 2005, the UN Security Council referred the situation in Darfur to the International Criminal Court for investigation of serious crimes committed there in violation of international law. Currently there are four fugitives from the ICC for crimes committed in Darfur, including Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir who is sought on charges of genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity. In 2014, violence has surged in Darfur with new large scale attacks on civilians. Human Rights Watch news release, March 21, 2014, https://www.hrw.org/news/2014/03/21/sudan-renewed-attacks-civilians-darfur.

[13] “Under Siege”, Human Rights Watch Report, December 11, 2012, https://www.hrw.org/reports/2012/12/11/under-siege.

[14] See, e.g. ”Reformists Split from Sudan’s Ruling Party,” Al Jazeera Online, October 26, 2013, http://www.aljazeera.com/news/africa/2013/10/reformists-split-from-sudan-ruling-party-2013102616654477391.html.

[15] “NCF demands UN investigation into killing of anti-government protesters in Sudan,” Radio Dabanga, October 20, 2013, at https://www.radiodabanga.org/node/57533 (accessed March 20, 2014).

[16] “Bashir Seeks Political, Economic Rennaisance,” Arabiya English, January 28, 2014, http://english.alarabiya.net/en/perspective/analysis/2014/01/28/Bashir-seeks-political-economic-renaissance-for-Sudan.html

[17] “Bashir Orders Release of Political Detainees,” Sudan Tribune, April 6, 2014, at http://www.sudantribune.com/spip.php?article50561 (accessed April 8, 2014).

[18] See Girifna, September 26, http://www.girifna.com/8702 (quoting Sudan Change Now report September 24, 2013).

[19] Amnesty International press statement, October 2, 2013, http://www.amnesty.org/en/news/sudan-escalates-mass-arrests-activists-amid-protest-crackdown-2013-10-02

[20] See, e.g., “Over 170 dead, including 15 children, and 800 detained as demonstrations spread throughout Sudan,” ACJPS press statement, October 4, 2013

[21] Human Rights Watch has seen lists from Abena, Sudan Change Now, Amal, and the National Committee in Solidarity with Families of Victims, on file. See footnote 9.

[22] James Copnall, “Sudan Feels the Heat from Fuel Protests,” BBC, November 14, 2013, at http://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-24938224.

[23] Human Rights Watch interview with Awadiya Khider Ahmed, Khartoum, October 16, 2013.

[24] Human Rights Watch interview with witness (name withheld) in Khartoum, September 29, 2013.

[25] Testimony of Awadiya Khidr Ahmed, posted by Sudan Change Now: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xcqyOW0liI8.

[26] Human Rights Watch interviews with witnesses (names withheld) in Khartoum, October 16, 2013.

[27] Human Rights Watch interview with Eman Abdelbagi in Khartoum, October 10, 2013.

[28] “A Killing by Sudanese Security Forces Stokes the Anger of a Protest Movement,” The New York Times, http://www.nytimes.com/2013/10/06/world/africa/killing-in-sudan-stokes-the-anger-of-a-protest-movement.html?pagewanted=all.

[29] Human Rights Watch interview with witness (name withheld) Khartoum, December 8, 2013.

[30] Human Rights Watch interview with the witness (name withheld) Khartoum, September 29, 2013.

[31] Human Rights Watch interviews with witnesses in Mayo area, Khartoum, December 10-11, 2013.

[32] Human Rights Watch interviews in al-Fatah, Omdurman, December 16, 2013.

[33] Human Rights Watch interview with witness (name withheld) Khartoum, October 21, 2013.

[34]YouTube interview, October 9, 2013, posted by Sudan Change Now, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lr9SLrY2fW8.

[35] Human Rights Watch interview with doctor (name withheld) December 19, 2013; See interview with Daoud, posted on Witness, http://blog.witness.org/2013/11/video-testimony-of-a-sudan-revolts-police-abuse-victim/ .

[37] Human Rights Watch interview with uncle of deceased, Khartoum October 18, 2013.

[38] Mamoun’s statement to the media, available at http://www.girifna.com/8797 (accessed March 30, 2014).

[39] Human Rights Watch interview with witness (name withheld), Khartoum, December 14, 2013.

[40] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Yousif el Mahdi, March 1, 2014.

[41] See, e.g., African Center for Justice and Peace Studies, www.acjps.org.

[42] “Young Protesters’ Trials Violate Sudanese Childrens Act,: lawyer” December 17, 2013, at https://www.radiodabanga.org/node/61974; E-mail communications with Siddig Yousif, head of the Sudanese Committee for Solidarity with the victims and detainees, March, 2014.

[43] “Dozens Held Without Charge,” Human Rights Watch news release, November 27, 2013, https://www.hrw.org/news/2013/11/27/sudan-dozens-held-without-charge.

[44] Human Rights Watch interviews with former detainees (names withheld), Khartoum, February 10, 2014.

[45] Human Rights Watch interview with former detainee (name withheld), Khartoum, November 13, 2013.

[46] Human Rights Watch interview with Mahamado, Khartoum, December 12, 2013.

[47] Human Rights Watch interview, Khartoum, October 10, 2013.

[48] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with opposition party member (name withheld), October 21, 2013.

[49] “Sudan: Dozens Killed During Protests,” Human Rights Watch news release, September 27, 2013. Censorship increased in 2014 with multiple suspensions and confiscations. See, .e.g. Reporters Without Borders, “Eleven Newspapers Seized in Less than a Week,” March 10, 2014, at http://en.rsf.org/sudan-eleven-newspapers-seized-in-less-10-03-2014,45967.html (accessed April 8, 2014).

[50] ”Over 170 dead,” ACJPS news release, October 4, 2013, at http://www.acjps.org/?p=1663.

[51] Ibid.

[52] “Why do you insist,” Sudan Tribune, September 30, 2013, at http://www.sudantribune.com/spip.php?article48254; see the YouTube video link of the press conference, at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X2gKUSSozgg (accessed March 20, 2014).

[53] Human Rights Watch telephone interviews with journalists and bloggers (names withheld) in Khartoum, February and March 2014.

[54] “Sudan Shuts Down Skye News,” Al Ahram Online, September 27, 2013, http://english.ahram.org.eg/NewsContent/2/8/82666/World/Region/Sudan-shuts-down-Sky-news-Arabia,-AlArabia-TV-offi.aspx.

[55] Access letter to data providers, on file with Human Rights Watch, dated October 11, 2013.

[56] See Mirghani’s statement to BBC at “Sudan Feels the Heat from Fuel Protests,” November 14, 2013, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-24938224.

[57] Human Rights Watch interview with Abdel Fatah al-Rufai, Khartoum, December 16, 2013.

[58] ACJPS statement, October 4, 2013, http://www.acjps.org/?p=1663, (accessed April 12, 2014).

[59] Sudan Tribune, “Head of doctor’s union taken into custody by Sudanese security,” October 5, 2013, http://www.sudantribune.com/spip.php?article48329 (accessed March 20, 2014).

[60] “Deadliest Day in Sudan’s Fuel Subsidies Protests”, Sudan Tribune, September 26, 2013, http://www.sudantribune.com/spip.php?article48182.

[61] See website of Sudan’s National Intelligence and Security Services (Arabic)

[62] Alsharq al-Awsat, September 26, 2013, No. 12721 (in Arabic)

[63] “Defiant Bashir slams ‘bandits’ and ‘traitors’ who planned recent protests”, Sudan Tribune article, October 10, 2013, http://www.sudantribune.com/spip.php?article48388 (accessed April 10, 2014).

[64] “Sudan President denies his involvement in killing of protesters,” Sudan Tribune article, October 2, 2013, http://www.sudantribune.com/spip.php?article48271 (accessed April 10, 2014).

[65] See Al Jazeera Arabic interview, November 6, posted on SudaniNet.net, at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MjTnyAlTzRs.

[66] “Sudan cuts internet for 48 hours as fears mount of new post-Friday prayer protests”, Sudan Tribune, September 27, 2013, http://sudantribune.com/spip.php?article48192.

[67] “Sudan raises death toll in fuel subsidy protests to 84”, Sudan Tribune, http://www.sudantribune.com/spip.php?article48705.

[68] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Siddig Yousif Ibrahim, head of the national committee for solidarity with families of those killed and detained, April 8, 2014.

[69] OHCHR press statement, 21 February, 2014, http://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=14269&LangID=E.

[70] Human Rights Watch interviews in Khartoum, December 10, 2013 and by telephone March 7, 2014.

[71] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with a lawyer involved in the case, Khartoum, March 15, 2014.

[72] Human Rights Watch confidential interview with family member, Khartoum, November 6, 2013. One common explanation by officials for refusing to open cases against security forces is that the forces have legal immunity under Sudanese laws. Human Rights Watch has long urged Sudan to repeal immunity provision.

[73] Human Rights Watch interview with witnesses in Omdurman, October 18 and December 16, 2013; interview with staff member of prosecutors’ office in Omdurman, December 3, 2013.

[74] OHCHR press statement, September 27, 2013, http://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=13793&LangID=E.

[75] US State Department press statement, September 27, 2013, http://www.state.gov/r/pa/prs/ps/2013/09/214865.htm.

[76] EU Catherine Ashton statement, September 30, 2013. http://eeas.europa.eu/delegations/sudan/documents/01032013.pdf.

[77] OHCHR press statement, February 20th, 2014, http://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=14269&LangID=E.