Summary

Ayu is a petite, soft-spoken 13-year-old girl from a village near Garut, in the mountains of West Java, Indonesia.[1] She is one of five children in her family, and her parents are farmers who cultivate tobacco and other crops on a small plot of land. “Since I was a kid, I’ve been going to the fields,” she said. “My parents plant tobacco. Mostly I help my parents and sometimes my neighbors. I have an older sister, an older brother, and two younger siblings. They help too.”

Ayu is in her first year of junior high school, and she mostly helps on the farm outside of school—early in the morning before classes, in the afternoons, and on weekends and holidays. But she told Human Rights Watch she occasionally missed school to work in tobacco farming. “My mom asked me to skip school last year when it was the harvest,” she said.

She told Human Rights Watch she vomits every year while harvesting tobacco:

I was throwing up when I was so tired from harvesting and carrying the [harvested tobacco] leaf. My stomach is like, I can’t explain, it’s stinky in my mouth. I threw up so many times…. My dad carried me home. It happened when we were harvesting. It was so hot, and I was so tired…. The smell is not good when we’re harvesting. I’m always throwing up every time I’m harvesting.

The symptoms she described—vomiting and nausea—are consistent with acute nicotine poisoning, an occupational illness specific to tobacco farming that occurs when workers absorb nicotine through their skin while having contact with tobacco plants.

Ayu also helps her father mix the toxic pesticides he applies to the tobacco. “I just put three or four cups of the chemical in the bucket, put in the water, and mix it with [a piece of] wood, and my dad puts it in the tank,” she explained. “The smell is so strong. It makes my stomach sick.” Like most of the farmers in her village, Ayu’s parents sell the tobacco they grow to the leader of their village, who pools together tobacco from dozens of farmers, transports it to a warehouse in Central Java, and sells it to a tobacco trader there. The trader buys tobacco from many different suppliers, repackages it, and sells it on the open market to Indonesian and multinational tobacco manufacturing and leaf supply companies.

This report—based on extensive research including interviews with more than 130 children who work on tobacco farms in Indonesia—shows that child workers are being exposed to serious health and safety risks. The dangers include acute nicotine poisoning from contact with tobacco plants and leaves, and exposure to toxic pesticides and other chemicals. Few of the children we interviewed, or their parents, were trained on safety measures or knew the health risks of the work. While Indonesian child labor laws are generally in line with international standards, our research shows that inadequate regulations and poor enforcement of the law, particularly in the small-scale farming sector, leave children at risk. The report concludes with detailed recommendations to the Indonesian government, tobacco companies, and other relevant players in the tobacco industry, including that authorities should immediately prohibit children from performing any tasks that involve direct contact with tobacco, and that companies should improve their human rights due diligence procedures to identify and end hazardous child labor on tobacco farms.

***

Indonesia is the world’s fifth-largest tobacco producer, home to more than 500,000 tobacco farms nationwide. Though domestic and international laws prohibit children under 18 from performing hazardous work, thousands of children like Ayu work in hazardous conditions on tobacco farms in Indonesia, exposed to nicotine, toxic pesticides, extreme heat, and other dangers. This work could have lasting consequences on their health and development.

The government of Indonesia has a strong legal and policy framework on child labor. Under national labor law, 15 is the standard minimum age for employment, and children ages 13 to 15 may perform only light work that is not dangerous and does not interfere with their schooling. Children under 18 are prohibited from performing hazardous work, including any work in environments “with harmful chemical substances.” Indonesia’s list of hazardous occupations prohibited for children does not specifically ban work handling tobacco. Human Rights Watch believes that available evidence demonstrates that any work involving direct contact with tobacco in any form constitutes work with harmful chemical substances, and should be prohibited for all children.

Nicotine is present in all parts of tobacco plants and leaves at all stages of production. Public health research has shown that tobacco workers absorb nicotine through their skin while handling tobacco, particularly when the plant is wet. Studies have found that non-smoking adult tobacco workers have similar levels of nicotine in their bodies as smokers in the general population. Nicotine is a toxin, and nicotine exposure has been associated with lasting adverse consequences on brain development. The use of protective equipment is insufficient to eliminate the dangers of working with tobacco and may lead to other dangers, such as heat illness.

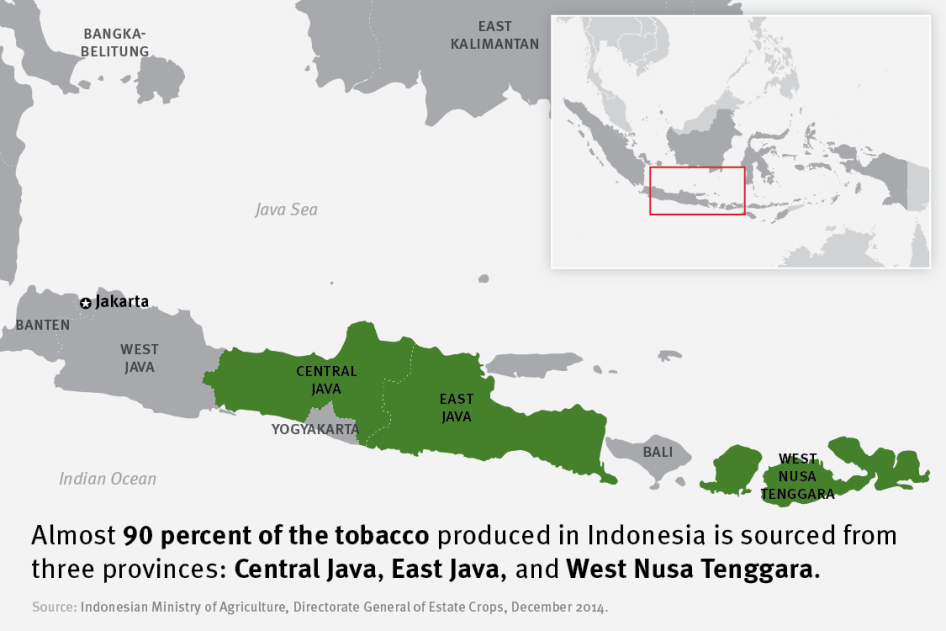

Despite the domestic and international prohibitions on hazardous child labor, Human Rights Watch documented children engaging in hazardous work in tobacco farming in four Indonesian provinces, including the three provinces responsible for almost 90 percent of tobacco production each year: East Java, Central Java, and West Nusa Tenggara. Children we interviewed worked directly with tobacco plants, handled pesticides, and performed dangerous physical labor in extreme heat, putting them at risk of short and long-term health consequences.

Some of the hazards faced by child tobacco workers in Indonesia are not unique to tobacco farming. Children working in other crops may also be exposed to pesticides, work in high heat, and face other dangers. However, handling tobacco is inherently hazardous work for children, due to the nicotine in the plant, and tobacco farming inevitably requires workers to have significant contact with the plant during cultivation, harvesting, and curing.

Many Indonesian companies and the largest multinational tobacco companies in the world purchase tobacco grown in Indonesia and use it to manufacture tobacco products sold domestically and abroad. Several of the largest multinational tobacco companies in the world have acknowledged the risks to children of participating in certain tasks on tobacco farms. These companies ban children under 18 from performing some of the most hazardous tasks on farms in their supply chains, such as harvesting tobacco or applying pesticides to the crop. But none of these companies have policies and procedures sufficient to ensure that tobacco entering their supply chains was not produced with hazardous child labor. As a result, these companies risk contributing to the use of, and benefitting from, hazardous child labor.

On three research trips between September 2014 and September 2015, Human Rights Watch interviewed a total of 227 people, including 132 children ages 8 to 17 who reported working on tobacco farms in 2014 or 2015, and 88 other individuals, such as parents of child workers, tobacco farmers, tobacco leaf buyers and sellers, warehouse owners, village leaders, health workers, representatives of nongovernmental organizations, and others. In addition, we met or corresponded with officials from several government bodies, including the Ministry of Manpower and Transmigration, the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Agriculture, the Ministry of Education and Culture, and the Indonesian Child Protection Commission.

Human Rights Watch sent letters to four Indonesian companies and nine multinational tobacco manufacturing and leaf supply companies, to share our research findings and request information on each company’s policies and practices regarding child labor in Indonesia. As detailed below, seven multinational companies responded in detail. We sent several letters and made numerous phone calls to each of the four Indonesian companies in an effort to secure a meaningful response, but none provided any substantive response. Human Rights Watch analyzed the human rights due diligence procedures of those companies that responded in detail to our letters as thoroughly as possible, based on information provided by the companies, publicly available information on their websites, and interviews with child workers, tobacco farmers, and traders in Indonesia.

Most of the children interviewed by Human Rights Watch started working in tobacco farming before age 15, the standard minimum age for employment in Indonesia. Approximately three quarters of the children we interviewed began working in tobacco farming by age 12. Most children worked on tobacco farms throughout the season, from planting through the harvest and curing process.

Children interviewed for this report typically worked on small plots of land farmed by their parents or other family members. In addition to working on land farmed by their families, many children also worked on land farmed by their neighbors and other members of their communities. Some children did not receive any wages for their work, either because they worked for their own families or exchanged labor with other families in their communities. Other children received modest wages.

Children in all four provinces said that they worked in tobacco farming to help their families. The World Bank reports that 14.2 percent of Indonesia’s rural population lives below the national poverty line, almost double the urban poverty rate. According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), “poverty is the main cause of child labor in agriculture” worldwide. Human Rights Watch research found that family poverty contributed to children’s participation in tobacco farming in Indonesia. “I want to help my parents make a living,” said 11-year-old Ratih, who worked on her parents’ tobacco farm in Jember, East Java. Sinta, a 13-year-old girl who worked on tobacco farms in her village in Magelang, Central Java, said, “I work so I can help my parents, to make life easier. To make it not such a difficult life.”

“My kids are helping me in the field so I can save money on labor,” said Ijo, a farmer in his mid-40s and father of four interviewed in Garut, West Java, in 2015. He said he was conflicted about his 12-year-old son helping him on the farm: “Of course I don’t want my kids working in tobacco because there’s a lot of chemicals on it, and it could harm my kids. But they wanted to work, and we are farmers.… I need more money to pay the laborers. But my son can help all season. You can imagine that I can save a lot of money when he joins me in the field. It’s complicated.”

Hazardous Work in Tobacco Farming

While not all work is harmful to children, the ILO defines hazardous work as “work which, by its nature or the circumstances in which it is carried out, is likely to harm the health, safety or morals of children.” The ILO considers agriculture “one of the three most dangerous sectors in terms of work-related fatalities, non-fatal accidents, and occupational diseases.”

Human Rights Watch found that many aspects of tobacco farming in Indonesia pose significant risks to children’s health and safety. Children working on tobacco farms in Indonesia are exposed to nicotine, toxic pesticides, and extreme heat. The majority of children interviewed for this report described sickness while working in tobacco farming, including specific symptoms associated with acute nicotine poisoning, pesticide exposure, and heat-related illness, as described below. Some children reported respiratory symptoms, skin conditions, and eye irritation while working in tobacco farming.

All children interviewed for this report described handling and coming into contact with tobacco plants and leaves containing nicotine. In the short term, absorption of nicotine through the skin can lead to acute nicotine poisoning, called Green Tobacco Sickness. The most common symptoms of acute nicotine poisoning are nausea, vomiting, headaches, and dizziness. Approximately half of the children we interviewed in Indonesia in 2014 or 2015 reported experiencing at least one symptom consistent with acute nicotine poisoning while working in tobacco farming. Many reported multiple symptoms. For example, Nadia, a 16-year-old girl in Bondowoso, East Java, said she vomits every year in the harvest season while bundling and sorting harvested tobacco leaves with other women and girls in her village. “Sometimes I get a headache. Sometimes I’m even throwing up … [It happens] when we string the leaves because we’re sitting in the middle of a bundle of tobacco.… It happens when the tobacco is still wet and just coming from the fields.… Every time it’s the beginning of the season, we’re throwing up.”

Rio, a tall 13-year-old boy, worked on tobacco farms in his village in Magelang, Central Java, in 2014. He told Human Rights Watch, “After too long working in tobacco, I get a stomachache and feel like vomiting. It’s from when I’m near the tobacco for too long.” He likened the feeling to motion sickness, saying “It’s just like when you’re on a trip, and you’re in a car swerving back and forth.”

The long-term effects of nicotine absorption through the skin have not been studied, but public health research on smoking suggests that nicotine exposure during childhood and adolescence may have lasting consequences on brain development. The prefrontal cortex, the part of the brain responsible for executive function and attention, is one of the last parts of the brain to mature and continues developing throughout adolescence and into early adulthood. The prefrontal cortex is particularly susceptible to the impacts of stimulants, such as nicotine. Nicotine exposure in adolescence has been associated with mood disorders, and problems with memory, attention, impulse control, and cognition later in life.

Many child tobacco workers interviewed for this report also said they handled or applied pesticides, fertilizers, or other chemical agents to tobacco farms in their communities. Some children also reported seeing other workers apply chemicals in fields in which they were working, or in nearby fields. A number of children reported immediate sickness after handling or working in close proximity to the chemicals applied to tobacco farms.

Sixteen-year-old Musa, for example, said he used a tank and handheld sprayer to apply a liquid chemical to his family’s tobacco farm in Garut, West Java, in 2015. He said he became very ill the first time he applied pesticides, after mixing the chemicals with his bare hands: “The first time, I was vomiting.… For two weeks, I couldn’t work. I went to the doctor. The doctor told me to stop being around the chemicals. But how can I do that? I have to help my parents. Who else can help them but me? … I mixed it with my hands. Suddenly I was dizzy. My parents told me to go home. I stayed home for two days, and my dad told me to rest for longer. It was a terrible feeling. For two weeks, I was always, always vomiting.”

Rahmad, a 10-year-old boy, described being exposed to pesticides while working on his family’s farm in Sampang, East Java, in 2015, “When my brother is spraying, I am cleaning the weeds. It stinks…. It smells like medicine. I feel sick. I feel headaches, and not good in my stomach. I’m in the same field…. Every time I smell the spray I feel dizzy and nauseous.”

Children are uniquely vulnerable to the adverse effects of toxic exposures as their brains and bodies are still developing. Pesticide exposure has been associated with long-term and chronic health effects including respiratory problems, cancer, depression, neurologic deficits, and reproductive health problems. In particular, many pesticides are highly toxic to the brain and reproductive health system, both of which continue to grow and develop during childhood and adolescence.

Few of the children interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that they had received any education or training about the health risks of working in tobacco farming. Very few children said that they wore any type of protective equipment while handling tobacco, and many said they wore no or inadequate protective equipment while working with pesticides or other chemicals.

Many children described working in high heat on tobacco farms. Some children we interviewed said that they had fainted, and others said that they felt faint or dizzy or suffered headaches when working in very high temperatures. Working in extreme heat can place children at risk of heat stroke and dehydration, and children are more susceptible than adults to heat illness.

Most children interviewed reported that they suffered pain and fatigue from engaging in prolonged repetitive motions and lifting heavy loads. Some children also said they used sharp tools and cut themselves, or worked at dangerous heights with no protection from falls.

Impact on Education

Most children interviewed by Human Rights Watch said they attended school and worked in tobacco farming only outside of school hours—before and after school, and on weekends and school holidays. However, Human Rights Watch also found that work in tobacco farming interfered with schooling for some children.

A few children had dropped out of school before turning 15—the compulsory age for schooling in Indonesia—in order to work to help support their families. These children often said their families could not afford to put them through school, or relied on them to work. Even though the Indonesian government guarantees free public education, and interviewees in most communities said they did not have to pay school fees to attend public schools, the costs of books, uniforms, transportation to and from school were prohibitive for some families. For example, Sari, a bright-eyed, 14-year-old girl in Magelang, Central Java, told Human Rights Watch she dreamed of becoming a nurse, but she stopped attending school after sixth grade in order to help support her family. “I want to go back to school to achieve my dreams for the future, but we don’t have much money to do that.”

Some children said they missed some days of school during busy times of the growing season. Eleven-year-old Rojo, the oldest child in his family, said he missed school to work in tobacco farming three or four times during the 2014 harvest season in Sampang, East Java: “My dad asked me to go to the field earlier, and not go to school,” he said. “I was worried I wouldn’t pass the exams.”

Some children interviewed said they found it difficult to combine school and work, and described fatigue and exhaustion or difficulty keeping up with schoolwork. Awan, a slender 15-year-old boy from Pamekasan, East Java, described how he balanced school and work during the high season: “When the harvest is coming, I have to wake up early in the morning, and I have to be [work] in the fields until 6:30 a.m., then go to school, and then continue in the fields in the afternoon…. We go [to the fields] around 4:30 or 5 a.m. It’s still dark, but I use a headlamp. I feel like I want to sleep longer. It’s tiring.” He told Human Rights Watch that this grueling schedule made it difficult for him to keep up with his schoolwork: “It’s harder to study than it is before the harvest,” he said. “It makes me so tired.”

Government Response

Under international law, the Indonesian government has an obligation to ensure that children are protected from the worst forms of child labor, including hazardous work, which is defined as “work which, by its nature or the circumstances in which it is carried out, is likely to harm the health, safety or morals of children.”

Indonesia has ratified several international conventions concerning child labor, including the ILO Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention, the ILO Minimum Age Convention, and the United Nations (UN) Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC). The ILO Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention requires member states to take immediate action to prevent children from engaging in the worst forms of child labor and to provide direct assistance for the removal of children already engaged in the worst forms of child labor.

Indonesia has strong laws and regulations regarding child labor, aligned with international standards, and has implemented a number of social programs to address child labor. Under Indonesian law, the general minimum age for employment nationwide is 15. Children ages 13 to 15 may participate in light work as long as the work does not interfere with their physical, mental, or social development. Indonesian labor law prohibits hazardous work by everyone under 18, and a 2003 decree from the Minister of Manpower and Transmigration details the list of specific tasks that are prohibited for children under 18. The list explicitly prohibits children from working in environments “with harmful chemical substances.” Under this provision, any work involving direct contact with tobacco in any form should be considered prohibited due to the high probability of exposure to nicotine and pesticides.

However, gaps in the legal and regulatory framework, and inadequate enforcement of child labor laws and regulations leave children at risk. The Indonesian government’s hazardous work list does not specify that the prohibition on children’s work with harmful chemical substances includes work handling tobacco, despite the dangers of nicotine exposure. This ambiguity leaves children vulnerable.

In addition, the government of Indonesia does not effectively enforce child labor laws and regulations in the small-scale farming sector. The Ministry of Manpower and Transmigration—the agency responsible for the enforcement of child labor laws and regulations—has about 2,000 inspectors carrying out labor inspections nationwide, in all sectors, far too few for effective labor enforcement in a country of more than 250 million people. In a meeting with Human Rights Watch, a ministry representative explained that labor inspections are done only in large-scale agro-industry, not in the small-scale agricultural sector where the vast majority of children interviewed for this report worked.

Tobacco Supply Chain and Corporate Responsibility

While governments have the primary responsibility to respect, protect, and fulfill human rights under international law, private entities, including businesses, also have a responsibility to avoid causing or contributing to human rights abuse, and to take effective steps to ensure that any abuses that do occur are effectively remedied. This includes a responsibility to ensure that businesses’ operations do not use, or contribute to the use of, hazardous child labor.

The United Nations (UN) Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, which the UN Human Rights Council endorsed in 2011, maintain that all companies should respect human rights, avoid complicity in abuses, and ensure that any abuses that occur in spite of these efforts are adequately remedied. The guidelines, widely accepted as an authoritative articulation of businesses’ human rights responsibilities, specify that businesses should carry out effective human rights due diligence, a process to identify potential risks of human rights abuse connected to their operations and take effective steps to prevent and mitigate negative human rights impacts linked to their operations. Businesses also have a responsibility to ensure that the victims of any abuses that occur in spite of these efforts are able to secure an appropriate remedy.

Tobacco grown in Indonesia enters the supply chains of Indonesian tobacco companies of various sizes, as well as the world’s largest multinational tobacco companies. The largest companies operating in Indonesia include three Indonesian tobacco manufacturers—PT Djarum (Djarum), PT Gudang Garam Tbk (Gudang Garam), and PT Nojorono Tobacco International (Nojorono)—and two companies owned by multinational tobacco manufacturers—PT Bentoel Internasional Investama (Bentoel), owned by British American Tobacco (BAT), and PT Hanjaya Mandala Sampoerna Tbk (Sampoerna), owned by Philip Morris International. Other Indonesian and multinational companies also purchase tobacco grown in Indonesia, as described below.

Tobacco farmers interviewed by Human Rights Watch sold tobacco in a number of ways. Most farmers sold tobacco leaf on the open market through intermediaries, or “middlemen.” In this system, small farmers described selling tobacco to a central farmer or leader in the village, or a local buyer, who would pool tobacco from many small producers and sell it to warehouses owned by local businessmen or by larger national or multinational companies purchasing tobacco leaf.

As an alternative to this system, some farmers had relationships with individual tobacco companies and had opportunities to sell tobacco directly to representatives of the company, rather than through intermediary traders. Under this system, some farmers signed written contracts to sell tobacco directly to tobacco product manufacturing or leaf supply companies.

Human Rights Watch interviewed more than 60 tobacco farmers, tobacco leaf buyers and sellers, and warehouse owners in the four provinces where we conducted research. We identified human rights risks, including child labor and occupational health and safety hazards, in both the open market system and the direct contracting system.

Most farmers and traders selling tobacco exclusively through the traditional open market system acknowledged that it was common for children to work in tobacco cultivation. Most of them stated that neither the government nor those purchasing tobacco leaf had ever communicated with them regarding child labor standards or expectations. Interviewees said that they were not aware of any attempts on the part of buyers, including companies with explicit policies that prohibit child labor, to verify the conditions in which tobacco was grown or inspect for child labor.

Farmers producing and selling tobacco through the direct contracting system said that they had received some training and education about child labor and health and safety from the tobacco companies with whom they contract. At the same time, Human Rights Watch found that companies’ human rights due diligence practices were not sufficient to eliminate hazardous child labor in the supply chain. Most farmers in the direct contracting system reported that children under 18 still participated in many tobacco farming tasks, and some farmers insisted there were no restrictions at all on children’s work in tobacco farming. Most farmers said there was no meaningful consequence or penalty if children were found working, even in the event of repeated violations. In the absence of any meaningful penalties, many farmers largely disregarded any efforts by companies to dissuade them from allowing children to work.

Human Rights Watch found that companies purchasing tobacco on the open market and through the direct contracting system risk purchasing tobacco produced by children working in hazardous conditions.

Human Rights Watch sought information regarding the human rights due diligence policies and procedures of 13 companies, including four Indonesian tobacco product manufacturers, seven multinational tobacco product manufacturers, and two multinational leaf merchant companies. Ten companies responded. Of the four Indonesian tobacco companies, two replied (Nojorono and Wismilak), but neither provided a detailed or comprehensive response to the questions we posed. A representative of Wismilak sent an email to Human Rights Watch stating that the company could not respond in detail because it is not “directly connected with the tobacco farmers,” but did not identify other actors in the supply chain who are directly in contact with growers. Nojorono replied in a letter and referred Human Rights Watch to GAPPRI (Gabungan Perserikatan Pabrik Rokok Indonesia), a cigarette manufacturer’s association, for information regarding tobacco farming, including child labor. Human Rights Watch subsequently wrote to GAPPRI, but they declined to meet with us. The largest Indonesian tobacco companies, Djarum and Gudang Garam, did not respond to Human Rights Watch, despite repeated attempts to reach them.

All of the multinational companies purchasing tobacco from Indonesia that responded to Human Rights Watch have child labor policies that are largely aligned and appear consistent with international standards, in particular key ILO conventions. However, none of the companies prohibit children from performing all tasks that could pose threats to their health and safety. This means that none of the companies have policies sufficient to ensure that all children are protected from hazardous work on tobacco farms in their supply chains.

Human Rights Watch analyzed the information on human rights due diligence provided by those companies that responded to our letters. Few of the companies are sufficiently transparent regarding their human rights due diligence procedures, particularly regarding their monitoring of their child labor policies throughout the supply chain, as well as the results of internal monitoring and external audits. Transparency is a key element of effective and credible human rights due diligence. Among the companies we studied, Philip Morris International appears to have taken the greatest number of steps to be transparent about its human rights policies and monitoring procedures, including by publishing on its website its own progress reports as well as several detailed reports by third party monitors.

Most multinational tobacco companies operating in Indonesia source tobacco through a mix of direct contracts with farmers and purchasing tobacco leaf on the open market, with some companies relying more heavily on one or the other purchasing model. Many companies acknowledged that they carry out little or no human rights due diligence in the open market system. However, all companies sourcing tobacco from Indonesia have responsibilities to carry out robust human rights due diligence activity and ensure that their operations do not cause or contribute to human rights abuse, even in complex, multilayered supply chains. Although most of the companies who responded to Human Rights Watch acknowledged child labor and other human rights risks in the open market system, none of the companies described having procedures in place that are sufficient to ensure that tobacco entering their supply chains was not produced with hazardous child labor.

The Way Forward

Based on the findings documented in this report, our analysis of international standards and public health literature, and interviews with experts on farmworker health, Human Rights Watch believes that any work involving direct contact with tobacco in any form should be considered hazardous and prohibited for children under 18, due to the health risks posed by nicotine, the pesticides applied to the crop, and the particular vulnerability of children whose bodies and brains are still developing.

We recognize that small-scale farming is an important part of Indonesia’s agricultural sector, and that in some areas, children have participated in family farming for generations. Though it may take time to change attitudes and practices around children’s role in tobacco farming, significant change is possible. In Brazil—the world’s second-largest tobacco producer and a country, like Indonesia, where tobacco is cultivated largely on small family farms—Human Rights Watch found that a strict and clear government ban on child labor in tobacco farming, and comprehensive health and safety education and training, were helping to eliminate hazardous child labor in the crop. The Brazilian government had established meaningful penalties for child labor violations, applied both to farmers and the companies purchasing tobacco from them, and the penalties pushed people to end or limit their children’s work on the farm. Indonesian authorities should take note of this approach.

As part of its efforts to eradicate the worst forms of child labor by 2022, the government of Indonesia should update its list of hazardous occupations for children, or enact a new law or regulation, to prohibit explicitly any work involving direct contact with tobacco in any form. There may be some light work on tobacco farms that is suitable for children, particularly in the early stages of tobacco production. For example, planting tobacco while wearing suitable gloves or watering tobacco plants with small, lightweight buckets or jugs could be acceptable tasks for children, as long as they were not working in extreme heat or dangerous conditions, and the work did not interfere with their schooling. However, Human Rights Watch believes that many aspects of tobacco farming in Indonesia constitute hazardous child labor under international standards, particularly most tasks involved in topping, harvesting, and curing tobacco, as there is no viable way to limit children’s direct contact with tobacco during these stages of production.

The government should vigorously investigate and monitor child labor and other violations in small-scale agriculture, including through unannounced inspections at the times and locations at which children are most likely to be working.

In addition, Indonesian authorities should take immediate steps to protect child tobacco workers from danger. The government should implement an extensive public education and training program in tobacco farming communities to promote awareness of the health risks to children of work in tobacco farming, particularly the risks of exposure to nicotine and pesticides.

All companies purchasing tobacco from Indonesia should adopt or revise global human rights policies prohibiting hazardous child labor anywhere in the supply chain, including any work in which children have direct contact with tobacco in any form. Companies should establish or strengthen human rights due diligence procedures with specific attention to eliminating hazardous child labor in all parts of the supply chain, and regularly and publicly report on their efforts to identify and address human rights problems in their supply chains in detail.

Methodology

Human Rights Watch conducted field research for this report in 2014 and 2015 in tobacco farming communities in 10 different districts located in four provinces of Indonesia: West Java, Central Java, East Java, and West Nusa Tenggara.

During three research trips between September 2014 and September 2015, Human Rights Watch interviewed 132 children ages 8 to 17 who reported working on tobacco farms, including 10 children in West Java, 19 children in Central Java, 88 children in East Java, and 15 children in West Nusa Tenggara.

In addition, Human Rights Watch interviewed 88 other individuals, including parents of child workers, tobacco farmers, tobacco leaf buyers and sellers, warehouse owners, village leaders, health workers, representatives of nongovernmental organizations, and others. In addition, we met or corresponded with officials from several government bodies, including the Ministry of Manpower and Transmigration, the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Agriculture, the Ministry of Education, and the Indonesian Child Protection Commission. In total, Human Rights Watch interviewed 227 people for this report.

Human Rights Watch identified interviewees through outreach in tobacco farming communities, and with the assistance of journalists, researchers, local leaders, and organizations serving farming families.

Interviews were conducted in Indonesian, Javanese, Madurese, Sasak, or Balinese with the help of interpreters. Human Rights Watch interviewed most children individually, though some children were interviewed in small groups. When possible, Human Rights Watch held interviews in private, though in a few cases, interviewees preferred to have another person present.

Human Rights Watch informed all interviewees of the purpose of the interview, its voluntary nature, and the ways in which the information would be collected and used. Human Rights Watch did not provide anyone with compensation in exchange for an interview. Many of the children interviewed were provided with a few food items to share with their families, as is culturally appropriate.

Participants gave oral informed consent to participate and were assured anonymity. Interviews were semi-structured and covered a range of topics related to health, safety, and education. Most interviews lasted 30 to 60 minutes, and all interviews took place in person.

The names of interviewees have been changed to protect their privacy, confidentiality, and safety. All of the accounts reported here, unless otherwise noted, reflect experiences children had while they were working on tobacco farms in 2014 or 2015.

Human Rights Watch also analyzed relevant laws and policies and conducted a review of secondary sources, including statistical reports prepared by the Indonesian government, data compiled by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, public health studies, and other sources.

In November 2015, Human Rights Watch sent letters to nine multinational tobacco manufacturing and leaf supply companies, and four Indonesian companies to share our research findings and request information on each company’s policies and practices regarding child labor in Indonesia. Our correspondence with the companies can be found in the appendix to this report, available on the Human Rights Watch website.

Terminology

In this report, “child” and “children” are used to refer to anyone under the age of 18, consistent with usage under international law.

The term “child labor,” consistent with International Labour Organization standards, is used to refer to work performed by children below the minimum age of employment or children under age 18 engaged in hazardous work.

As described below, children interviewed for this report said they worked in a variety of different situations on tobacco farms, including as unpaid workers on farms owned or operated by their family members, as hired workers, and as part of labor exchanged between families. Throughout the report, we use the terms “worker” or “farmworker” to refer to children working in any of these circumstances. In general, we use the term “farmer” to refer to the person with primary responsibility for a farm’s operations.

Indonesia is a large and diverse country, and Human Rights Watch did not use a random sampling method. The children we interviewed may not be representative of the broader population of child tobacco workers nationwide. Still, Human Rights Watch observed patterns and similarities in our field research in four provinces of Indonesia over the course of two tobacco growing seasons (2014 and 2015). While specifying the number of children performing hazardous work in tobacco farming in Indonesia is beyond the scope of the methodology used here, our research strongly suggests that many children in Indonesia beyond those we interviewed are working in similarly hazardous conditions on tobacco farms.

I. Background: Tobacco in Indonesia

Tobacco Production

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Indonesia is the world’s fifth largest producer of unmanufactured tobacco, behind China, Brazil, India, and the United States.[2] Most of the tobacco leaf produced in Indonesia is used for domestic production, but a large quantity of leaf is also exported.[3] In 2013, for example, Indonesia exported about one-fourth of the country’s total tobacco production, an export value of almost US$200 million.[4]

The Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture reports that tobacco is grown in 15 of the country’s 34 provinces, but almost 90 percent of the tobacco produced in Indonesia is sourced from three provinces: East Java, Central Java, and West Nusa Tenggara.[5] The vast majority of Indonesia’s tobacco—98 percent—is grown by “smallholders,”[6] farmers that own or operate small plots of land, usually no more than a few hectares, and sometimes less than one hectare.[7]

According to data from the World Bank, Indonesia had a total population of 254.5 million people in 2014, and 34.3 percent of people “of working age” were involved in agricultural work that year.[8] In 2014, there were a total of 543,181 tobacco farmers in Indonesia.[9]

Tobacco Farming and Curing Process

Several types of tobacco are grown in Indonesia, including Virginia (or “flue-cured”), burley, oriental, and other varieties. Indonesia is a vast country, and tobacco farming and curing practices vary depending on the climate and terrain of the region and the types of tobacco grown.

In the areas where Human Rights Watch conducted research, farmers typically cultivate small plots of land that they or their families own or rent, and rotate tobacco with several other crops at different times of the year, such as rice or vegetables, depending on variations in rainfall. Many farmers grow tobacco to sell for profit and cultivate rice and other crops primarily for their own consumption.

Most farmers, even farmers cultivating small plots of land, rely on labor from outside of their immediate families to grow tobacco. Families often said adults and children exchanged work days with many of their neighbors or hired day laborers to work during the labor-intensive parts of the growing season. In the description that follows, we refer to all individuals working in tobacco farming as “farmworkers,” a term meant to encompass family labor, exchange labor, and hired labor.

The tobacco growing season begins near the start of the dry season in May or June when farmworkers till soil to prepare fields, and plant tobacco seeds in small beds. Farmworkers tend to the seedlings until they are a few centimeters tall, and then transplant them by hand into fields.

After planting the seedlings in fields, farmworkers water the tobacco plants by hand every day, or multiple times a day, for several weeks, often using buckets attached to a wooden frame worn across the shoulders. They maintain the tobacco until it is mature enough to harvest—uprooting weeds by hand or with sharp hoes, removing worms and insects by hand, and applying fertilizers and pesticides as needed at various points in the season. In some communities, farmworkers “top” the tobacco (break off large flowers that sprout at the tops of plants) and remove nuisance leaves to help the plant grow.

In the areas visited by Human Rights Watch, farmworkers harvest tobacco leaves entirely by hand, often in stages, through a series of separate harvests starting from the bottom of the plant. Farmworkers pick the tobacco leaves off of the stalks, gather them under their arms, and load them into sacks to be transported to barns or homes for curing.

Human Rights Watch observed a variety of curing methods in different regions of Indonesia. In many communities in East Java and Central Java, tobacco is “sun-cured,” or dried in the sun. Farmworkers stack and fold harvested leaves into small bundles, leave the bundles to dry for a few days indoors, and then thinly slice the tobacco with sharp knives and spread it on bamboo mats to dry in the sun. When the tobacco has dried, workers then roll and compress it into large sacks in preparation for selling. In other parts of East Java, farmworkers dry tobacco by piercing four to five tobacco leaves and stringing them onto small, sharp bamboo sticks and leaving them in fields to dry before preparing them for selling.

In West Nusa Tenggara, most farmers interviewed cultivated Virginia, or “flue-cured” tobacco, which is dried in heated curing barns. Farmworkers typically tie harvested leaves to wooden sticks with string, and then load the sticks of leaves into the rafters of brick curing barns heated by fire. Workers maintain fires in small ovens external to the barns that distribute heat through pipes (“flues”). The leaves are dried in barns for several days before being removed. In these areas, farmworkers classify cured leaves into several categories according to the color and size of the leaves, and compress them to form bales.

Tobacco Consumption in Indonesia

Although the sale of tobacco products to children is prohibited by law, more than one-third of boys ages 13 to 15 in Indonesia currently use tobacco products.[10] According to the Ministry of Health, more than 3.9 million children ages 10 and 14 become smokers every year, and at least 239,000 children under the age of 10 have started smoking.[11] Smoking increases rapidly among adults, with nearly three of four males ages 15 and older smoking. By contrast, roughly 5 percent of women and girls ages 15 and older smoke.[12]

More than 40 million Indonesian children under 15 are exposed to passive smoking.[13] According to the World Health Organization (WHO), passive smoking can increase the risk of lung cancer in nonsmokers by between 20 and 30 percent, and the risk of heart disease by 25 to 35 percent.[14] Secondhand smoke also increases the risk of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), and may cause serious health problems in children, including more frequent and severe asthma attacks, respiratory infections, and ear infections.[15]

Despite these outcomes, Indonesia is one of the few countries in the world that has not become a party to the World Health Organization’s Framework Convention on Tobacco Control,[16] a global public health treaty that aims “to protect present and future generations from the devastating health, social, environmental and economic consequences of tobacco consumption and exposure to tobacco smoke.”[17] National laws permit many types of tobacco advertising, promotion, and sponsorship.[18] The 2014 Global Youth Tobacco Survey, a nationally representative school-based survey of nearly 6,000 seventh to ninth-grade students in Indonesia, found that more than 60 percent of students saw tobacco advertisements or promotions at points of sale, or saw tobacco use on television, videos, or movies. Almost 10 percent of respondents said they owned something with a tobacco brand logo on it.[19]

Kretek, cigarettes made from a combination of tobacco and ground cloves, are particularly popular in Indonesia and have been used there since the 1800s. A 2015 study of kretek smoking in Indonesia found an estimated 90 percent of adult smokers consumed kretek, which, like all tobacco products, are associated with serious health consequences.[20] WHO estimates that tobacco use kills up to half of its users—more than five million people worldwide, and roughly 240,000 people in Indonesia, each year.[21]

II. Child Labor in Tobacco Farming in Indonesia

The International Labour Organization (ILO) estimates that more than 1.5 million children ages 10 to 17 work in agriculture in Indonesia each year.[22] The United States Department of Labor (DOL) reports that more than 60 percent of working children ages 10 to 14 in Indonesia are involved in the agricultural sector, including in fishing, as well as in the production of rubber, palm oil, and tobacco.[23] In a meeting with Human Rights Watch, the Ministry of Manpower and Transmigration, the government institution responsible for labor issues, told Human Rights Watch it estimates about 400,000 children nationwide are involved in child labor in fishing and agriculture.[24] According to ILO, East Java and Central Java are the provinces with “the largest incidence of child labourers” in agriculture.[25]

Human Rights Watch could not find any official estimates of the number of children involved in child labor in tobacco farming in Indonesia each year. We requested information from both the Ministry of Manpower and Transmigration and the Ministry of Agriculture regarding the number of children estimated to be working in tobacco farming, and neither office could provide relevant data.[26]

Child Tobacco Workers

Consistent with the findings of other reports on child labor in tobacco farming in Indonesia,[27] most of the children interviewed by Human Rights Watch started working in tobacco farming before age 15, the minimum age for employment in Indonesia. [28] Approximately three quarters of the child tobacco workers we interviewed began working in tobacco farming by age 12.[29]

Children’s Jobs on Tobacco FarmsChildren interviewed by Human Rights Watch for this report said they performed one or more of the following tasks while working on tobacco farms:[30]

|

Most child tobacco workers interviewed for this report worked on small plots of land farmed by their parents or other family members. They typically said they worked alongside their parents, siblings, and other family members, and often worked on other crops as well, such as rice or vegetables. In addition to working on land farmed by their own families, many children also worked on land farmed by their neighbors and other members of their communities. Some children said they work on up to 20 other families’ farms. Some children did not receive any compensation for their work, either because they worked for their own families or exchanged labor with other families in their communities. Other children received wages, as described below.

Regardless of the circumstances of their work, child tobacco workers generally reported participating in a range of tasks on tobacco farms depending on the type of tobacco grown and the curing process utilized in the region. Most children worked throughout the season, from planting through the harvest and curing process. In some communities, work in tobacco farming was gendered, with certain tasks performed primarily by women and girls, and other tasks performed primarily by men and boys.

Wages

Some child tobacco workers did not receive any compensation for their work, either because they worked for their own parents, or because their families exchanged work days with other farmers in their communities. For example, Agus, a 17-year-old boy in Magelang, Central Java, who had left school and hoped to become “a successful farmer,” explained that his family trades work with the neighbors in his village. “I work for the neighbors. If I have the chance, I help the neighbors with planting and harvesting.… I don’t get paid because the neighbors also help my parents in their field.” Interlocking his fingers, he added, “It’s brotherhood around here. We help each other.”[31]

Awan, a 15-year-old tobacco worker in Pamekasan, East Java, described a similar system between his family and the other families in his village. When asked if he was paid when working for his neighbors, he said, “No, they never pay me. They give me bread or drinks. I have to help them because if I help them, they’ll help me too. We have to help each other finish the harvest before it [the tobacco] turns yellow [spoils].”[32]

Kristina, a 17-year-old girl with a narrow face, played with her mauve scarf while she described the labor exchange in her Pamekasan, East Java, community: “I help other neighbors who plant tobacco besides my parents because they will help me and my family when the harvest comes. We don’t need pay from the neighbors. Otherwise my dad would lose a lot of money paying them back…. My dad can’t afford to pay a lot of neighbors [to work on his farm], so he asks me to help them. We don’t take money from the neighbors.”[33]

Human Rights Watch interviewed 17-year-old Matius outside his family’s home in Pamekasan, East Java, in 2015. He described a similar system, “The tradition here is helping each other, so I help my neighbors and all of my family. Sometimes they give me money. But sometimes we have to pay it back by exchanging work. Like if I’m harvesting now, my neighbors will help me, and when they harvest, my family will help them, without paying.”[34]

Other children said they were paid a daily rate for their work, most often when working for neighbors or extended family members. Among the children who were paid, most reported earning modest wages ranging from 5,000 rupiah (US$0.35) to 20,000 rupiah ($1.45) for a few hours of work, depending on the task they performed.[35] Children who worked longer hours reported earning approximately 20,000 to 50,000 rupiah ($1.45 to $3.60) per day.[36] Some interviewees reported that men and boys were paid higher daily wages than women and girls.[37]

Some children in East Java and West Nusa Tenggara said their neighbors or extended family members paid them piece rate wages for tying or stringing tobacco leaves to bamboo sticks before curing, often 1,000 rupiah ($0.07) for 8 to 12 sticks of leaves. They reported that they earned between 12,000 and 30,000 rupiah ($0.85 to $2.15) per day for a few hours of such work.[38]

Why Children Work

Children in all four of the provinces where Human Rights Watch carried out research said that they worked in tobacco farming to help their families. Many parents and children also described a long tradition in their communities of children participating in small-scale family farming.

Poverty

The World Bank reports that 14.2 percent of Indonesia’s rural population lives below the national poverty line, almost double the urban poverty rate.[39] According to the ILO International Programme on the Elimination of Child Labour (IPEC), “poverty is the main cause of child labor in agriculture” worldwide.[40] Human Rights Watch research found that family poverty contributed to children’s participation in tobacco farming in Indonesia.

Many farmers interviewed for this report said tobacco was the main crop they cultivated for profit, as they used other crops primarily for subsistence. Some said they struggled to survive on the earnings from the tobacco season. Many said they carried debts to neighbors or family members, and described seasons in which they did not make the profit they had hoped for due to bad weather, an excess supply of tobacco, or other factors. One farmer interviewed by Human Rights Watch in Temanggung, Central Java, explained that excess supply drove down the price of tobacco in 2014: “The rate is low because a lot of farmers are growing tobacco. This is the last year I want to sell tobacco. It’s really hard, and I lost a lot of money.”[41] Many farmers noted that they had little control over the price and classification of the tobacco, which determined their earnings.

Many children said they worked because they wanted to help their parents maintain the farm and provide for the family, and some felt their work could help their families save time and money from the cost of hiring laborers. Human Rights Watch interviewed Ratih, an 11-year-old girl who works on her parents’ tobacco farm in Jember, East Java, after she returned home from sports practice one morning in 2015. “I feel sorry for my parents that they’re working,” she said. “So I help them … I want to help my parents make a living.”[42] Ratih is one of four children in her family. Her mother explained that she started bringing her children to the fields with her when they were young, in part so that she and her husband did not have to hire laborers at every stage of the growing season, and in part so she could watch over the children while she worked in the fields. “My kids help us in the field because it costs a lot of money to ask someone to water the tobacco. So since they were [young] kids, my girls have been going to the field to help me and play there. I can’t take care of my girls here [at home] while I’m working in the fields, so I bring them with me.”[43]

“My kids are helping me in the field so I can save money on labor,” said Ijo, a farmer in his mid-40s and father of four interviewed in Garut, West Java, in 2015. He said he was conflicted about his 12-year-old son helping him on the farm. “Of course I don’t want my kids working in tobacco because there’s a lot of chemicals on it, and it could harm my kids. But they wanted to work, and we are farmers.… I need more money to pay the laborers. But my son can help all season. You can imagine that I can save a lot of money when he joins me in the field. It’s complicated.”[44]

Some children used their earnings to help their families purchase food and other basic necessities. Sari, a 14-year-old girl who stopped attending school after sixth grade in order to work on farms in Magelang, Central Java, told Human Rights Watch in 2014, “I’m working to help my parents and family buy food and anything else they need.” Sinta, a 13-year-old girl who works in the same village, said, “I work so I can help my parents, to make life easier. To make it not such a difficult life.”[45]

Other children worked to raise money for their school books or uniforms, or for snacks and meals at school. Human Rights Watch interviewed 13-year-old Utari, a small girl who wore gold earrings and a yellow shirt and shorts, in Probolinggo, East Java, in 2014. She said she used the wages she earned bundling tobacco leaves to pay for her school supplies: “I use my earnings to pay for school. I use the money to buy books and my uniform. My books cost 24,000 rupiah [approximately US$1.75 per semester]. I buy the books myself,” she said.[46]

Tradition

In addition to family poverty, ILO-IPEC cites “traditional attitudes towards children’s participation in agricultural activities” as a cause of child labor.[47] Many people interviewed for this report stated that it was common for children to work in the fields as part of traditional family farming practices. “As a tradition as farmers, our children go to the fields to be a small help,” said Hanif, a 45-year-old farmer in Probolinggo, East Java, interviewed by Human Rights Watch in 2015.[48] Maya, a farmer and mother of six children ages 9 to 28 in Garut, West Java, explained why her children helped on her farm. “It’s common here, and they help a lot. Sometimes we don’t have much money to pay laborers,” she said. “We are farmers.”[49]

III. Hazardous Work in Tobacco Farming

While not all work is harmful to children, the International Labor Organization (ILO) defines hazardous work as “work which, by its nature or the circumstances in which it is carried out, is likely to harm the health, safety or morals of children.”[50] The ILO considers agriculture “one of the three most dangerous sectors in terms of work-related fatalities, non-fatal accidents, and occupational diseases.”[51]

Human Rights Watch found that many aspects of tobacco farming in Indonesia pose significant risks to children’s health and safety, consistent with our findings on hazardous child labor in tobacco farming in the United States.[52] Children working on tobacco farms in Indonesia are exposed to nicotine, toxic pesticides, and extreme heat. The majority of children interviewed for this report described sickness while working in tobacco farming, including specific symptoms associated with acute nicotine poisoning, pesticide exposure, and heat-related illness, as described below. Some children also reported respiratory symptoms, skin conditions, and eye irritation while working in tobacco farming.

Most children interviewed for this report suffered pain and fatigue from engaging in prolonged repetitive motions and lifting heavy loads. Some children also said they used sharp tools and cut themselves, or worked at dangerous heights with no protection from falls. Many children slipped and fell while working in wet, muddy fields, in some cases splashing themselves with chemicals they were carrying in buckets or tanks.

Few of the children interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that they had received any education or training about the health risks of working in tobacco farming. Very few children wore any type of protective equipment while handling tobacco, and many wore no or inadequate protective equipment while working with pesticides or other chemicals.

Nicotine

All children interviewed for this report described handling and coming into contact with tobacco plants and leaves at various points in the growing season. Nicotine is present in tobacco plants and leaves in any form,[53] and public health research has shown that tobacco workers absorb nicotine through their skin while handling tobacco.[54] Studies have found that non-smoking adult tobacco workers have similar levels of nicotine in their bodies as smokers in the general population.[55]

In the short term, absorption of nicotine through the skin can lead to acute nicotine poisoning, called Green Tobacco Sickness. The most common symptoms of acute nicotine poisoning are nausea, vomiting, headaches, and dizziness.[56]

Approximately half of the children we interviewed in Indonesia in 2014 or 2015 reported experiencing at least one specific symptom consistent with acute nicotine poisoning while handling tobacco, including nausea, vomiting, headaches, and dizziness. Children said they experienced these symptoms while removing flowers and competing leaves from tobacco plants, harvesting leaves, carrying harvested leaves, wrapping or rolling leaves to prepare them for drying, working in curing barns, and working with dried tobacco.[57]

Vomiting and Nausea

Some children in East Java, Central Java, West Java, and West Nusa Tenggara described nausea and vomiting while working in tobacco farming.

Some children said they vomited while harvesting tobacco leaves. For example, Wani, 16, and Nina, 18, have been working together on tobacco farms in Sampang, East Java, for several years. Wani, who wore a delicate black lace headscarf, told Human Rights Watch she vomited while harvesting in 2014: “I’ve been vomiting from the smell of the tobacco leaf. And I’ve gotten a headache too.” Nina also said she vomited while harvesting wet tobacco leaves in 2014: “The wet leaves are smellier than the dry leaves,” she explained. “That’s what made me throw up.”[58]

Aman, 18, has been helping on his father’s tobacco farm in Sumenep, East Java, since he was in junior high school. He said he got violently ill while harvesting tobacco in 2014 and had to seek medical treatment at the hospital: “I was vomiting but I couldn’t get it out, it was stuck in my throat.… It happened twice. Last year and the year before. I went to the hospital both times…. Last year was the worst. They gave me oxygen and an IV [intravenous therapy]. It felt like hot in my stomach and then I was dizzy all the time.”[59]

Thirteen-year-old Ayu, one of five children in her family, told Human Rights Watch she vomits every year while harvesting tobacco on farms in her village near Garut, West Java: “I was throwing up when I was so tired from harvesting and carrying the [harvested tobacco] leaf. My stomach is like, I can’t explain, it’s stinky in my mouth. I threw up so many times…. My dad carried me home. It happened when we were harvesting. It was so hot, and I was so tired…. The smell is not good when we’re harvesting. I’m always throwing up every time I’m harvesting.”[60]

Some children had never vomited, but said they often felt nauseated and queasy while working around tobacco. Rio, a tall 13-year-old boy, worked on tobacco farms in his village in Magelang, Central Java, in 2014. He told Human Rights Watch, “After too long working in tobacco, I get a stomachache and feel like vomiting. It’s from when I’m near the tobacco for too long.” He likened the feeling to motion sickness, saying “It’s just like when you’re on a trip, and you’re in a car swerving back and forth.”[61]

Eddi, 16, stopped going to school in fifth grade in order to help his parents on their farm in Magelang, Central Java. He told Human Rights Watch he got sick while harvesting tobacco in 2014: “When I take off the leaves, the leaves have a liquid and it’s smelly. I have to harvest a lot of leaves. I feel weak and I get a headache.” He also suffered nausea during the harvest: “I feel queasy,” he said. “My stomach hurts.”[62]

Indirah, a 14-year-old girl whose parents work as hired laborers on several tobacco farms in Jember, East Java, said she feels nauseated every year during the tobacco harvest: “When I’m picking the leaves, I feel like I want to throw up. It’s an uncomfortable feeling. It’s just like nausea. It happened last season. Mostly every season I feel like that. I haven’t thrown up, but I feel queasy. It’s uncomfortable.”[63]

Other children reported nausea and vomiting while bundling and sorting harvested or dried tobacco leaves, or working in curing barns. For example, 14-year-old Leah said she vomited in a tobacco field during the harvest in 2014, and again, later in the season, while she was sorting and bundling harvested leaves in her village in Garut, West Java. “When we’re choosing [classifying and bundling] tobacco leaves, it’s dirty. Last season, I was throwing up…. It was so painful in my stomach. It felt like burning and my throat, it was so hard to swallow.”[64] Her mother explained, “[When we are] wrapping leaves, the smell is so strong. I know [she] was vomiting because the smell was so strong.”[65]

Nadia, a 16-year-old girl in Bondowoso, East Java, whose parents grow chili, corn, rice, tomatoes, and tobacco, said she vomits every year in the harvest season while bundling and sorting harvested tobacco leaves with other women and girls in her village. “Sometimes I get a headache. Sometimes I’m even throwing up… [It happens] when we string the leaves because we’re sitting in the middle of a bundle of tobacco.… It happens when the tobacco is still wet and just coming from the fields. It only happens at the beginning of the season when we haven’t adapted yet. Every time it’s the beginning of the season, we’re throwing up.”[66]

Thirteen-year-old Yulia, who worked in curing barns in East Lombok, West Nusa Tenggara, in 2014, said she felt queasy while carrying dried tobacco leaves. “I feel sick to my stomach because I have to lean over and smell it [the tobacco] again and again,” she said. She described painful dry heaving: “It hurts because it’s like you want to throw up, but the food won’t come out. It’s better if you can actually throw up.”[67] “I was nauseous when I was loading the tobacco into the barn,” said Riko, a 15-year-old boy who worked on his uncle’s tobacco farm in East Lombok, West Nusa Tenggara, in 2015. “I don’t know why it happened. I felt weak. I threw up two times behind the barn…. It’s happened more than once. This season, just one time. Last season, it happened two times.”[68]

Headaches and Dizziness

Children in all four of the provinces where Human Rights Watch carried out research described getting headaches, and feeling dizzy, lightheaded, and weak while handling tobacco at different stages of the production process.

Emilia, a 12-year-old girl who hopes to be a teacher, told Human Rights Watch that she felt lightheaded while stacking green tobacco leaves and wrapping them into bundles in her village in Probolinggo, East Java, in 2014. “When I’m wrapping, I feel dizzy and I get headaches. I feel like I see stars.”[69] William, 16, said he got sick when topping tobacco in Sampang, East Java, in 2014. “My body is like … I don’t know how to describe it. Like weak. Suddenly I feel like I’ve lost all my energy. It happens when I cut the flowers.”[70]

Human Rights Watch interviewed 14-year-old Raden while he was on a break from school in Sumenep, East Java, in June 2015. He described feeling dizzy and lightheaded while harvesting tobacco: “When we’re harvesting, I often feel sick because of the smell of the wet tobacco leaves, and I get a strong headache…. Sometimes it’s hard to breathe when there’s a lot of tobacco leaves near me. I can’t describe it. I get such a headache. I’m dizzy. I see stars, and everything just looks bright.”[71]

Peni, 13, started working in tobacco farming in her community in Magelang, Central Java, at age 12. “When I’m harvesting, I feel dizzy,” she said, describing her work in 2014. “It’s because the tobacco leaf smells. It’s like you’ve been spinning around.”[72] Fourteen-year-old Topan also worked in Magelang, Central Java, in 2014, and described similar feelings when harvesting: “I feel dizzy and get a headache when I’m harvesting. It feels like throbbing in my head because of the smell and the heat.”[73]

Yulia, age 13, worked with her younger sister and her cousin at tobacco curing barns in East Lombok, West Nusa Tenggara, in 2014. Sitting on the floor in her brown school uniform, she described getting headaches while working around dried tobacco. “When I untie the dry tobacco, the smell is so bad,” she said. “It gives me a headache. I don’t know how to explain it, but the smell makes my head feel so heavy, I just want to lie down.” She also described feeling dizzy while working. “It feels like I’m seeing stars all over my head, and I just want to fall down. It’s like an earthquake.”[74] Dewi, 11, worked at the same East Lombok curing barns in 2014 and reported similar symptoms while working with dried tobacco. “When I untie the tobacco, the smell goes right up my nose. It makes me dizzy,” she told Human Rights Watch. “When you feel dizzy, you hardly know what direction to go. You’re like swaying and don’t know where you are.”[75]

Exposure to Nicotine

All of the child tobacco workers interviewed by Human Rights Watch were exposed to nicotine while handling and coming into contact with tobacco plants and leaves at various points in the growing season. Many children said their clothes got wet while working in fields of tobacco plants wet with morning dew. Working in wet, humid conditions increases the risk of nicotine poisoning as nicotine dissolves in the moisture on the leaf and is more readily absorbed through the skin.[76]

The experience of Dumadi, a 12-year-old worker in Garut, West Java, was typical among the child tobacco workers interviewed by Human Rights Watch: “It’s wet when we harvest…. I use the ugliest clothes for harvesting because if I use my best clothes, they’ll get dirty and black, so I have to use old clothes…. Of course it’s wet. On sunny days, I’m sweaty. And in the mornings, the tobacco has dew. My clothes get really wet.” He said he looked drenched after returning home from the fields. “It’s as if it rained,” he said.[77]

Some children said they felt sick while working in wet clothes. Fourteen-year-old Indirah in Jember, East Java, said, “It’s wet because there’s still dew in the tobacco leaves. My clothes get wet. It’s an uncomfortable feeling, and I’m working in the sweaty clothes.” She said she felt sick while working in wet fields, though she attributed her sickness to the smell of the tobacco: “It’s because there’s a lot of leaves in the field. The smell of a lot of tobacco makes me sick.”[78]

Sixteen-year-old David, a worker in Probolinggo, East Java, said working in wet clothes, as well as the tar from the tobacco leaf irritated his skin: “When you’re harvesting, your skin will be so dry and sticky from the glue [tar on the tobacco leaves].” He noticed particular irritation in the area under his arm where he held tobacco leaves: “My skin sometimes it gets itchy on my underarm. When I take off the leaves, I carry them under my arms because the sacks are a little far from the field. So we have to carry a big bundle to the edge of the field. That’s why my clothes get wet because the tobacco leaves are wet. And it’s especially wet under my arm,” he said, rubbing his upper torso.[79]

Most children said tobacco leaves left a black, sticky residue on their hands, and some said their hands smelled sour or tasted bitter while they ate, even after washing. For example, 10-year-old Farah, who started helping on her father’s Sampang, East Java, tobacco farm when she was 9, said, “I don’t wear gloves. My hands are black after I’ve been taking off the leaves. The smell is like a chemical, and it feels sticky.” She said the smell remained on her hands even after washing, “When I finish helping my dad take off [harvest] the leaf, it tastes bitter in my mouth. When I come home for dinner, I’ve already washed my hands, but the food tastes bitter.”[80]

Health Risks of Nicotine Exposure

While Human Rights Watch cannot determine the exact causes of the illnesses reported by the children we interviewed without more detailed biological screening and examination, the symptoms presented above are consistent with acute nicotine poisoning, known as Green Tobacco Sickness, an occupational health risk specific to tobacco farming. Green Tobacco Sickness occurs when workers absorb nicotine through their skin while having contact with tobacco plants, particularly when plants are wet.[81] Research has shown nausea, vomiting, dizziness, and headaches are the most common symptoms of acute nicotine poisoning.[82]

Acute nicotine poisoning generally lasts between a few hours and a few days,[83] and although it is rarely life-threatening, severe cases may result in dehydration which requires emergency treatment.[84] Children are particularly vulnerable to nicotine poisoning because of their size, and because they are less likely than adults to have developed a tolerance to nicotine.[85]

The long-term effects of nicotine absorption through the skin have not been studied, but public health research on smoking suggests that nicotine exposure during childhood and adolescence may have lasting consequences on brain development.[86] The prefrontal cortex, the part of the brain responsible for executive function and attention, is one of the last parts of the brain to mature and continues developing throughout adolescence and into early adulthood.[87] The prefrontal cortex is particularly susceptible to the impacts of stimulants, such as nicotine. Nicotine exposure in adolescence has been associated with mood disorders, and problems with memory, attention, impulse control, and cognition later in life.[88]

Pesticides and Other Chemicals

Many child tobacco workers interviewed for this report said they handled or applied pesticides, fertilizers, or other chemical agents to tobacco farms in their communities, often without wearing suitable protective equipment. Some children also reported seeing other workers apply chemicals in fields in which they were working, or in nearby fields. A number of children reported immediate sickness after handling or working in close proximity to the chemicals applied to tobacco farms. They described a range of symptoms including nausea, vomiting, stomach pain, headaches, dizziness, skin irritation, rashes, coughing, and difficulty breathing.

Children Applying Pesticides

Children in all four provinces where Human Rights Watch carried out research described mixing pesticides, sometimes with their hands, or applying pesticides or other chemical agents to tobacco plants using tanks, often worn on their backs, and handheld sprayers. Many of the children felt immediately ill after handling the chemicals, describing vomiting, headaches, dizziness, itchy skin, and other symptoms.

Musa, a 16-year-old boy who hopes to become a soccer player, said he used a tank and handheld sprayer to apply a liquid chemical to his family’s tobacco farm in Garut, West Java, in 2015. He said he became violently ill the first he applied pesticides, after mixing the chemicals with his bare hands: “The first time, I was vomiting. … For two weeks, I couldn’t work. I went to the doctor. The doctor told me to stop being around the chemicals. But how can I do that? I have to help my parents. Who else can help them but me? … I mixed it with my hands. Suddenly I was dizzy. My parents told me to go home. I stayed home for two days, and my dad told me to rest for longer. It was a terrible feeling. For two weeks, I was always, always vomiting.”[89]

Argo, 15, told Human Rights Watch he applied a liquid chemical to his parents’ tobacco farm in Pamekasan, East Java, in 2015. “I pour it in the water, and I shake it up, and then I spray it all over the tobacco,” he said. “There’s a tank I wear on my back.” He described an incident when he felt suddenly, acutely ill while applying pesticides without protective equipment: “Once I was vomiting. It was when it was planting time, and I didn’t use the mask, and the smell was so strong, I started throwing up. I drank water right after, but I had to keep working so my dad wouldn’t get mad at me. It felt like something strange bubbling up in my throat.”[90]

“Last year, I started learning how to spray the fields,” said Sartoro, 16, who has been working in tobacco farming for his parents, relatives, and neighbors in Probolinggo, East Java, since he was 13. “I mix three of the small bottles [of liquid] with a big bucket of water and pour it into the tank.… I get dizzy when I smell it. It’s a headache like someone punched you in the head. It gives you pain in your stomach because the smell is so strong. I feel queasy.”[91]

Sari, a 14-year-old girl who stopped attending school after sixth grade in order to work on her family’s Magelang, Central Java, tobacco farm, told Human Rights Watch: “I help my father spray with the tanks. I don’t know how to mix the water with the pesticides, but I’ve sprayed the plants with the pesticides after my father mixed it. It [the tank] hurts my shoulders. I feel bad when I spray. It’s almost like I’m going to pass out. It smells terrible.”[92]

Fifteen-year-old Catur, a thin boy who started working in tobacco at age 12, told Human Rights Watch that he mixed and applied pesticides while working in Magelang, Central Java, in 2014: “I use a tank that I put on my back. My right hand pumps the water and my left hand sprays the chemicals. I mix the chemicals into the water. I use one capful for each tank…. I get dizzy because the smell is so bad. It happens often, very often.” He added, “The chemicals get on my skin. It’s itchy.”[93]

Rexi, 15, Topan, 14, and Michael, 15, are friends and worked together in tobacco farming in their Magelang, Central Java, village in 2014. Human Rights Watch interviewed the boys together, and all three said they mixed and applied pesticides to tobacco farms in 2014. Rexi told Human Rights Watch, “The smell makes me feel sick.… I get a stomachache and feel queasy when I’m spraying the pesticides.” Rexi also said the chemicals irritated his skin: “My skin gets a rash when the chemicals get on it. I get red bumps on my hands because I mix it with my hands.” Michael described a similar reaction to working with pesticides: “I can’t stand the smell. It’s a bad smell, like overripe fruit. I get a headache when I’m spraying.… It’s a really strong smell. It makes it hard for me to breathe.” Topan also reported difficulty breathing while mixing and applying pesticides in 2014: “It’s too smelly, that’s why it’s hard to breathe. So we have to work fast. It’s like you can’t get enough air.”[94]