Summary

Whenever they want to do mining again, they should do it far from the people and not the way they did it this time. They should explain to everyone what the advantages and disadvantages are. People need to know what to expect.

—Nagomba E., Mwabulambo, March 8, 2016

Nagomba E., 75, has lived all her life in Mwabulambo, a small rural community in northern Malawi. Like most women in the area, she works as a farmer to support her family—her husband and three grandchildren who survived their own parents—growing rice, maize, and cassava close to her home.

In 2008, she was surprised to find strangers driving big trucks and carrying heavy machinery near her crop fields. They were workers of Eland, a coal mining company. While the government had already given the company a license to operate a mine right by her village, Nagomba and her neighbors first heard about the mine when they saw the trucks.

When she eventually learned that they were digging coal, she hoped it would bring development to the village and some benefits such as job opportunities and healthcare infrastructure for her and her family. Instead, the mining company cut the community’s existing drinking water supply by destroying the water pipes running through the mining area. They left the community with a few boreholes and river water for drinking and domestic use. Nagomba used to have access to tap water near her house. Since the pipes were destroyed, she has had to make the strenuous hike down to the river about four times a day to fetch water. She worries that the river may be polluted from the mine, and she is uncertain if water from the river is safe to drink.

With little information from the company, Eland Coal Mining Company, or the government about the health and environmental impacts associated with mining or how to protect her family against them, Nagomba and other community members also face considerable health risks, especially in the absence of a community health center.

A few months after the trucks arrived, Eland, with the government’s approval, told Nagomba’s family and more than a dozen of their neighbors to move from the land the community had used as farms and upon which they had built their homes for several generations. They were told the company needed the land. The company gave Nagomba’s family just 50,000 Malawian Kwachas (MWK) (about US$150) as compensation: an amount that, she says, fell short of the basic material costs to buy new land and replace her house. As a result, her family was forced to sell two cows to cover the expenses needed to build a new home, and they lost some of their fields. Later on, the company started using coal to fill holes in the dust road leading from the main road to the mine. Nagomba believes that some of the coal floated into her remaining fields by the road and caused her harvest to decrease significantly.

Two years later, in 2010, the mining company asked Nagomba and her family to move again. This time they refused. “I really wish I had known before moving the first time that where we built our second house was a location that would be used for mining later on,” Nagomba said. In 2015, Eland closed operations in Mwabulambo, leaving behind piles of coal and several open pits filled with water next to Nagomba’s house.

Nagomba is worried about her family’s future. She thinks that children and animals could fall into the open pits and that the river water she and other villagers are using might be polluted because the company has not cleaned up the mining site. The local government officer in charge of environmental inspections at the mine left in 2015, and Nagomba has not seen any government or company official in more than a year.

***

Stories like that of Nagomba are all too common in Malawi’s mining communities. Over the past 10 years, Malawi’s government has promoted private investment in mining and resource extraction as a way to diversify its economy, which previously was mostly comprised of agricultural production. Malawi possesses considerable mineral deposits, including large uranium and coal reserves in the north as well as gemstones and rare earths in the south. The government has issued a high number of prospecting licenses for many parts of the country, allowing exploration for oil and gas extraction in areas including those around Lake Malawi that are protected United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage sites.

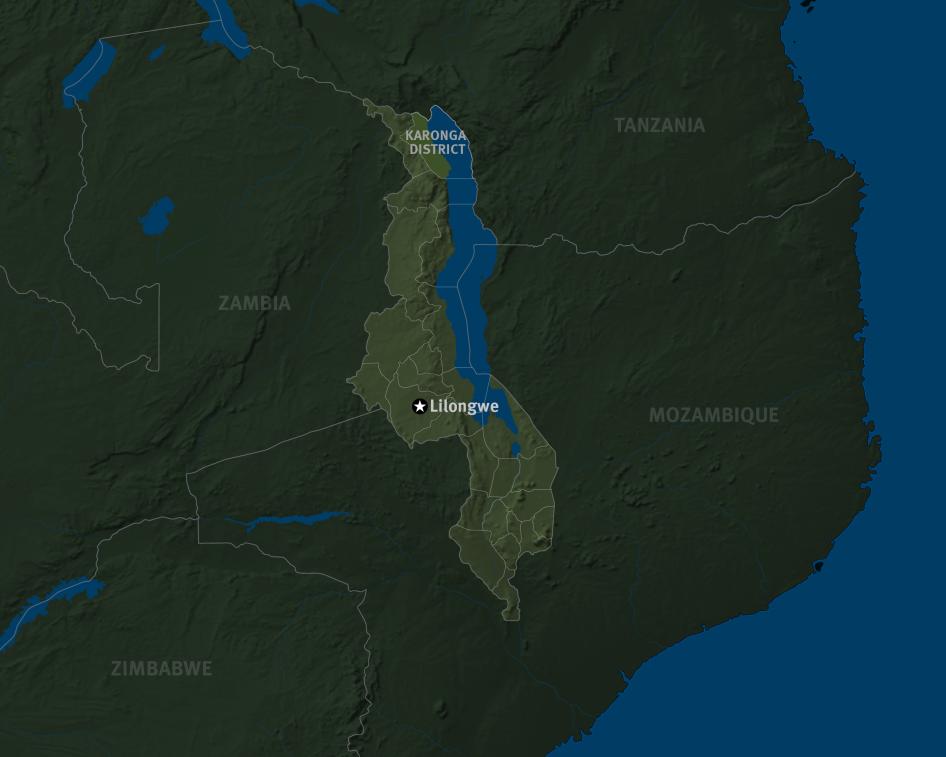

Karonga, where Nagomba lives, is located on the northwestern shores of Lake Malawi and on the border with Tanzania. Karonga has been the country’s test case for coal and uranium mining. It is the district where the first uranium mine opened in 2009, and where two out of the four biggest coal mines in the country are now located.

The government hopes that private sector investment from Malawian and international companies will transform the country, creating jobs and improving residents’ livelihoods as well as their access to water, health care, education, and other infrastructure.

But this development strategy poses significant risks to local communities. As multinational extractive companies—including from Australia and Cyprus—have started to explore and mine in Karonga district and neighboring districts around the lake, communities have voiced serious concerns about potential environmental damage, which in turn threatens people’s rights to health, water, food, and housing. More than 10 existing and potential future extraction sites are located on the shores and tributaries of Lake Malawi, a fragile ecosystem and a key source of livelihood for over 1.5 million Malawians. Where mining activities require land acquisitions, communities are worried they might lose their lands and homes without due process, adequate compensation, or suitable alternatives.

Based on more than 150 interviews with community members, government officials, civil society groups, and company representatives, this report examines the human rights impacts of Malawi’s nascent mining industry on communities living in and around the country’s mining areas and assesses the nature and extent of the information about mining to which local residents have access. Using Karonga district in northern Malawi as a case study, the report documents how Malawi currently lacks adequate legal standards and safeguards to ensure the necessary balance between developing the mining industry and protecting the rights of local communities. It examines how weak government oversight and lack of information leave local communities unprotected and uninformed about the risks and opportunities associated with mining.

While Malawi has some laws and policies that protect the rights of communities potentially affected by mining—some of which mention the need to monitor impacts of mining licenses and to compensate them for certain losses—they are poorly implemented and enforced. The result is that key government watchdogs stand by as spectators while mining operations are allowed to progress, regardless of the negative impact they may have on local communities or the environment.

A new draft law, the Mines and Minerals Bill (MM Bill), while relatively progressive in many respects, fails to address one of the core problems described in this report: a lack of transparency about the risks related to mining.

This report makes recommendations to strengthen existing laws, to improve the proposed MM Bill and Access to Information Bill (ATI Bill), and to enforce existing regulatory protection standards.

Malawi’s extractive industries are still in their infancy and there are opportunities for the government and investors to respect rights and minimize the risks faced by communities and natural ecosystems, even as they push for economic development. These include ensuring that the draft mining bill protects the rights of local communities, including their right of access to information; that the social and environmental impact of new mining projects is comprehensively and credibly assessed and addressed; that resettlements are implemented with full respect for rights; and that there are enough regulators to evaluate new proposals and follow up with onsite visits. It is important that the government assesses how much damage has already been done due to mining projects, and that it ensure that communities are properly informed about the potential benefits and risks of existing and future projects.

Mining Practice and Promises

Global industry standards have evolved to recognize that unless mine operators exercise caution and vigilance, it is likely that mining will harm surrounding communities. In Malawi and globally, there is evidence that without effective government regulation, not all companies behave responsibly. Even companies that make serious efforts to do so often fall short without proper government oversight. The United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights provide basic steps companies should take to respect human rights, including conducting due diligence to avoid causing or contributing to human rights abuses through their operations; avoiding complicity in abuses; and taking steps to mitigate them if they occur.

Several extractive companies have come to Karonga district in the past 10 years seeking to exploit natural resources, particularly uranium and coal. As in Nagomba’s case, communities do not often have prior knowledge of proposed mining operations since consultation is either insufficient or nonexistent. This is especially worrying as mining operations have had a major impact on the daily functioning of these communities, often complicating access to water, health, cropland, and food, and forcing relocations of community members. At the same time, companies operating in the district, including Paladin Africa Limited (Paladin), Eland Coal Mining Company, and Malcoal, have largely failed to deliver on promises to build schools, health centers or clinics, and boreholes, and to create employment opportunities for community members.

None of the communities in Karonga or civil society organizations interviewed by Human Rights Watch indicated they opposed, in principle, exploration or mining activities on their lands. However, community members repeatedly stressed inadequate information about mining-related health risks; inadequate participation in decision-making about the relocation process; a lack of proper notification before resettlement; inadequate compensation for losses from mining; a lack of government oversight to help mitigate current and future risks to health, water, food security, land and livelihoods; and a lack of awareness of their rights or companies’ responsibilities under national laws and international standards.

For example, in the coal and uranium mining areas in Karonga district that Human Rights Watch visited, residents said that they face health and livelihood risks due to the mining and suffer from increasing rates of illnesses that could be mining-related. Some complained that trucks pass along narrow village roads, coating homes and local schoolhouses in dust, and worried about the potential for serious respiratory diseases and other health impacts that scientific studies have associated with exposure to mining-related pollution. Several villagers also claimed that mining had destroyed water pipes or contaminated other water sources such as boreholes they depend on for drinking and irrigation. Farmers complained that dust in the air, coal on the road, and poor water quality impacted their crops and decreased the harvest of their fields, threatening economic ruin. Mining in Karonga district has also resulted in some families being resettled, often without adequate warning, decent resettlement conditions, or compensation.

In some cases, the harm that communities have suffered due to nearby mining operations is reported by the media or documented in studies conducted by international and civil society organizations. But in many other instances, the data simply does not exist to confirm or refute alleged negative impacts or their links to mining operations. Some community activists may wrongly attribute health or environmental problems to nearby mining operations. Others may fail to perceive a link that does in fact exist. The lack of healthcare infrastructure in these communities makes monitoring and addressing the health impacts of mining operations nearly impossible. This uncertainty is part of the problem. Government regulators repeatedly fail to determine whether companies are complying with their legal responsibilities, or whether they are causing harm to nearby communities.

Out of three companies featured in this report and contacted by Human Rights Watch, only one company, Paladin, said that they are monitoring the environmental impact of their mining activities in Malawi and are sharing these reports with the government. But they have never published their results, leaving communities unable to properly assess the risks associated with mining or mitigate the impacts that it can have on livelihoods. None of the companies contacted made any monitoring results available to Human Rights Watch.

Impact on Women

Human Rights Watch found that when mining has negative consequences for communities, women are disproportionately impacted. Malawi’s Constitution and policies recognize women’s right to full and equal protection in the law as well as their right to non-discrimination on the basis of their gender or marital status. However, in practice, their rights are largely curtailed by socio-cultural gender norms and patriarchal beliefs and attitudes.

It has often been particularly difficult for women to access information about mining and its risks—important to them as family caregivers—because their participation in meetings with companies or the government was limited. Women could be directly or indirectly excluded from such meetings. For example, if and when meetings were called by companies or the government they were not typically announced ahead of time, and women would often be busy working on their fields or at home at the time of such meetings. As a result of the short notice, they would not have the time to make the necessary arrangements to be able to attend. Even when women were present, they were sometimes unable to engage due to gender norms that restrict women participation in public gatherings or because of language issues. That is, meetings were sometimes conducted in English or Chichewa, which rural women in Karonga district typically do not speak.

In Malawi, women, both young and old, are often the primary caregivers at home and are also largely responsible for growing crops on the fields that feed the family. Therefore, when mining and climate change impacted crop productivity and contributed to food shortages, women have had to work long hours to make up for the shortfall and sustain the family. Also, concerns about water pollution compelled many women and girls to walk longer distances to fetch water from what they believed was a less contaminated source, further away from the mines. This exposed them to dangers and left them with less time to attend school, earn money, and rest.

The communities in Karonga district follow largely patrilineal systems of land inheritance, and men tend to have more decision-making power concerning land transfers. As a result, women have little say in how compensation is spent.

Government Role

Many human rights abuses described in this report result from the government’s failure to effectively monitor, let alone systematically address, the impacts of mining operations.

International and regional human rights law obliges Malawi’s government to protect the rights of its citizens from potential harmful impacts of mining operations and to ensure that communities have access to information about these impacts and risks before, during, and after operations.

Malawi’s current regulatory framework for mining and the environment is outdated. The laws were passed long before current mining operations started and afford communities little protection from environmental pollution and harmful social impacts. While impact assessments should be mandatory for all projects that potentially affect the environment and community health, Malawi’s regulatory framework regarding Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs) for mining operations remains unclear and incomplete as it does not require the assessments of social impacts. Malawi’s mining law also provides little guidance with regard to environmental impacts of mining, leaving the scope and cycle of environmental monitoring at the discretion of government officials. It also largely fails to make information about mining and related risks available and accessible to affected communities. Land laws establish a variety of forms of land tenure and set out standards for land transfers or compulsory acquisitions. However, there is no national resettlement policy, and, in practice, land rights for individuals and communities near mining sites are highly insecure.

The draft MM Bill the government is developing does not address the core problem described in this report: access to adequate information. Quite the contrary, one of its major weaknesses is a broad confidentiality provision that would essentially prevent communities from accessing information about the risks related to mining. This is happening at a time when Malawi has just joined the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI)—a global network aimed at improving transparency in mining governance— as a candidate country and is preparing and negotiating an ATI Bill. Even though the draft ATI Bill from November 2015 appeared to be acceptable to most relevant stakeholders, the government revised the bill again in February 2016. Unlike the 2015 draft, the revised bill does not provide for the establishment of an independent oversight body; it limits the principle of maximum disclosure to documents created after the adoption of the law; and it gives the minister of information the power to determine “fees payable for processing requests for information,” which can discourage poor people from requesting information.

The government should dramatically improve the process for considering mining project proposals to ensure that it assesses and addresses possible environmental and social impacts in a comprehensive and credible manner. This means mandating a greater and more explicit focus on environmental risks and human rights in the licensing and monitoring process in the proposed Mines and Minerals bill. Implementation will also require adequate numbers and capacity of regulators so new proposals can be evaluated properly, including through site visits wherever appropriate. The government should also ensure that communities are properly informed about the potential benefits and risks of mining and are involved in developing mitigation strategies to address any adverse impacts. Moreover, the government should require compensation for loss of land and other resources and ensure that effective and accessible grievance mechanisms provide redress to those who suffer harm.

Government and Company Responses

Several public officials interviewed by Human Rights Watch openly admitted that they do not know how prevalent or how serious the impacts of mining on communities are and that they are not proactively providing information about the risks to affected communities. In fact, some government officials said that the government essentially leaves companies to regulate themselves, a practice that is inconsistent with Malawi’s obligations under international human rights law and that has consistently proven disastrous in other countries, including neighboring countries in southern Africa.

Malawi’s government has also acknowledged the impact mining can have on the health and livelihoods of people living in nearby communities. Government officials are aware of the weaknesses of the regulatory system and admitted that authorities sometimes fail to adequately protect environmental health and monitor pollution due to capacity problems or lack of internal coordination among government agencies at the various levels of government.

In interviews with Human Rights Watch, the government committed to increasing the number of health facilities for residents in mining communities and to including a focus on social issues in guidelines for EIAs. The Ministry of Natural Resources, Energy and Mining promised to visit each mine once per month. In a meeting with Human Rights Watch, officials of the ministry said that they were working with Eland to set up a closure plan to ensure the safety of the residents. However, at time of writing no updates about the implementation of these steps were communicated to Human Rights Watch.

The three companies examined in this report have a mixed track record on preventing, mitigating, and monitoring social and environmental harms from mining.

In a letter to Human Rights Watch, Paladin stated that the company maintains safety, health, radiation, and environmental management programs. Paladin also pointed to a Human Rights Policy, highlighting Paladin’s commitment to respecting human rights. However, it is not clear how these programs or the Human Rights Policy intend to assess and mitigate the environmental and social impacts of mining. In an interview with Human Rights Watch, Paladin Malawi said that the company does not publicly disclose monitoring results regarding water testing or other potential environmental impacts. Paladin did not reply to Human Rights Watch’s request for information about the monitoring results at their mine in Kayelekera.

Malcoal stated in an email to Human Rights Watch that they “strive to help the government to reduce rural poverty by providing employment while at the same time taking care of our communities and the environment.” Malcoal disputed that any resettlements had taken place in Kayelekera but did not comment on any of the other issues raised in this report.

Representatives of Eland Coal Mining Company informed Human Rights Watch in writing and by phone that their mine has suspended operations. At the time of writing, they had yet to reply to Human Rights Watch’s request for comment on the substantive issues raised in this report, including plans for rehabilitation of the mining site.

The Way Forward

The government of Malawi should take preventive measures to ensure that mining projects are planned and carried out in a way that does not violate the rights of local communities, and that minimizes displacement and disruption of livelihoods. This includes the addition of provisions to the draft MM Bill that require robust environmental and health monitoring at all stages of the mining process and ensure access to information as guaranteed under the constitution.

The government should also put in place effective mechanisms to oversee the activities and impacts of mining during and after operations. This involves robust reporting requirements for companies and regular, unannounced inspections by the government. The government needs to ensure that impact assessments and periodic inspections contain relevant details, including the potential impacts that exploration, active mining, and abandoned mines may have on communities and their rights; steps the government and companies will take to continually inform and communicate with affected communities; and how adverse rights impacts will be mitigated or avoided. The government should also ensure effective coordination between different ministries and national, regional and district government bodies involved in mining governance and oversight.

Finally, the government needs to effectively disseminate information to communities that may be adversely affected by operations of extractive industries before, during, and after operations. Impact assessments, environmental monitoring reports, and resettlement plans should be easily and readily available and accessible to the public by providing short summaries in non-technical language; translating the summaries and the full reports into local languages; posting them on the Internet; providing copies in public buildings such as local schools; and holding information sessions in directly affected communities.

Key Recommendations

To the Government of Malawi

- Include provisions in the draft Mines and Minerals Bill that require robust environmental and health monitoring at all stages of the mining process and ensure access to information as guaranteed under the constitution.

- Ensure coordination between different ministries and national, regional and district government bodies involved in mining governance and oversight.

- Revise the draft Access to Information Bill to ensure that minimum requirements for access to information follow international best practices and are in line with the model law by the African Union.

To the Ministry of Natural Resources, Energy and Mining

- Ensure that impact assessments and periodic inspections contain relevant details, including the potential impacts that exploration, active mining, and abandoned mines may have on communities and their rights; steps the government and companies will take to continually inform and communicate with affected communities; and how adverse impacts will be mitigated or avoided.

- Ensure impacts on marginalized populations, such as women and children, are monitored and addressed.Such monitoring should cover the cumulative impacts on the environment and livelihoods, including impacts resulting from extractive industries, social changes, and climate change.

- Ensure that impact assessments, environmental monitoring reports, and resettlement plans are easily and readily available and accessible to the public, including by providing short summaries in non-technical language; translating the summaries and the full reports into local languages; posting them on the Internet; providing copies in public buildings such as local schools; and holding information sessions in directly affected communities.

- Promptly fill all vacancies for inspectors in the Ministry of Mining and at the district level including the vacant environmental officer position in Karonga district. Increase the number and capacity of staff and resources available to conduct more regular in-field assessments, including unannounced inspections.

To the Ministry of Lands, Housing and Urban Development

- Provide a process for fair compensation and remedy negative human rights impacts of relocation in mining communities, including through compensation for losses that have already occurred. Pay special attention to the impacts on women and ensure they are appropriately compensated for their losses.

To the Ministry of Health

- Actively monitor health indicators and disease patterns in mining communities and ensure that results are easily available and accessible to the public.

- Develop a national strategy to improve health in mining communities and increase access to healthcare in mining areas, taking into account the increased health risks for marginalized populations. Include measures to support family caregivers, especially women.

To the Ministry of Agriculture, Irrigation and Water Development

- Map out the boundaries of watersheds potentially impacted by mining operations and actively monitor water throughout watersheds under the influence of mining to identify potential contamination, including monitoring waste water discharges, ground and surface water sources, and drinking water in mining communities on an ongoing basis. Ensure that results are easily available and accessible to the public.

To the Mzuzu Regional Office of Mines and to the Karonga District Commissioner

- Ensure that environmental monitoring reports are easily available and accessible to the public in the northern region.

To Companies Extracting Minerals in Malawi

- Improve public access to information and transparency by strengthening communication with local and national civil society and with affected community members. Make the outcomes of environmental assessments, periodic environmental monitoring reports, resettlement action plans, and updates on implementation available in easily accessible formats and fora. Include short summaries of each document available in non-technical language. Summaries and full reports should be translated into local languages, made available online, and posted in public buildings.

- Provide a process for fair compensation and remedy negative human rights impacts of relocation in mining communities, including compensation for losses that have already occurred. Pay special attention to the impacts on women and ensure they are appropriately compensated for their losses.

Methodology

This report is based on research conducted between July 2015 and July 2016, including six weeks of field research in Malawi. Human Rights Watch visited the capital city, Lilongwe; the regional capital Mzuzu; as well as mining sites in Karonga district and Rumphi district. Human Rights Watch undertook field work in two rural communities in Karonga district. The district was chosen for the research because large-scale and mid-scale mining activities in this area are most advanced. The first large-scale uranium mine was opened in Karonga in 2009, and two out of four major coal mines are located in the area.

Human Rights Watch interviewed more than 150 people for this report, including 78 people living in mining communities; 9 company representatives; and more than 45 people who currently work, or have worked, on mining issues in Malawi and neighboring countries, including: staff of international and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), health administrators, and academic researchers. We also spoke to 24 government officials, including five from the Ministry of Natural Resources, Energy and Mining, two from the Ministry of Health, two from the Ministry of Information, two from the Ministry of Lands, Housing and Urban Development, one from the Ministry of Agriculture, Irrigation and Water Development and six local political representatives.

Of the 78 community members, 45 were adult women and 33 were adult men. Six were traditional leaders. Interviews were conducted in Chichewa, Tumbuka, and Nkhonde via an interpreter. All interviewees provided verbal informed consent and were assured that they could end the interview at any time or decline to answer any questions. Where requested or appropriate, this report uses pseudonyms to protect their privacy. Interviewees were not compensated for speaking to us.

Human Rights Watch reviewed secondary sources—including mining inspection reports, academic research, and media reports—to corroborate information from community members. We also reviewed Malawian laws and policies. In March and August 2016, Human Rights Watch met with government officials at the relevant ministries in Lilongwe. In July 2015, February 2016, and July 2016 Human Rights Watch wrote to the mining companies cited in this report to request information on the steps taken to address the lack of access to information and other human rights issues documented in this report. In response to our request Human Rights Watch received a letter from Paladin in August 2015, an email from Eland in August 2015, and several emails from Malcoal in July 2016. Human Rights Watch also met with then-Paladin Malawi Manager Greg Walker in August 2015.

I. Background

Extractive Industries in Malawi

In this country, as I have said so many times before, we have no mines, no factories. The soil is our only mine, in fact. And all the money that we have here comes from the soil. It comes from the soil in the form of [m]aize, [g]roundnuts, [b]ananas, [b]eans, [p]eas, [t]obacco, [c]offee, [c]otton, [r]ice and so forth.[1]

—Former President Hastings Kamuzu Banda, Lilongwe, 1964

Like many other countries in southern Africa, Malawi is rich in a range of natural resources. Among these are deposits of coal, gemstones, rare earths, cement, uranium, oil, and gas.[2] While the largest coal fields are located in northern Malawi (Karonga and Rumphi districts), most of the gemstones and rare earths can be found in the south. More significant considering Malawi’s small size are the uranium reserves found in Karonga district, which amount to 0.5 percent of global deposits.[3] Oil and gas deposits around Lake Malawi are currently under exploration.

During more than 30 years of dictatorship from 1961 to 1994, former President Hastings Banda promoted farming as the path to development and prosperity. He opposed the extraction of minerals, even denying their existence.[4] In the absence of other industries, most Malawians lived as subsistence farmers in the countryside.

Today, Malawi’s extractive industries only make up a small portion of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). This is in contrast to most neighboring countries, such as Zambia and Zimbabwe, where mining has long made substantial contributions to the national economy.[5] The mining sector has grown since 2009, with growth rates of 14.9 percent in 2012 and 6.9 percent in 2013.[6] Several mines stalled their operations with the collapse of global commodity prices in 2014, which explains the modest contribution of the mining sector to Malawi’s GDP in recent years. The amount that the mining sector contributes to Malawi’s GDP has fluctuated over the years and data on the matter varies across sources. One government report put the 2014 contribution at around 3 percent, while another one only attributes 0.9 percent of the GDP to mining for the same year.[7] President Peter Mutharika suggested in 2015 that mining was contributing 6 percent to the country’s GDP in that year.[8]

When market prices recover, the government expects substantial increases in Malawi’s extractive output. For 2016, government analysts anticipated growth of 3.6 percent.[9] The government has already approved an estimated total of 500 licenses for industrial and artisanal mining and has repeatedly affirmed its plans to diversify the economy. There are currently only 50 large-scale active mining licenses in Malawi. The number of prospecting licenses for future large scale industrial mining is at 74, which, if all came to production, would more than double the number of active mining operations.[10]

In 2011, the World Bank provided the government with US$25 million in credit for its Mining Governance and Growth Support Project, which aims to increase efficiency and transparency within the mining sector. In 2015, the government published the results of a countrywide, geophysical airborne survey which showed geophysical data about mineral occurrences in Malawi. The extractive sector is likely to attract more investment.[11]

Several existing and potential mining sites, including those for energy resources such as uranium and coal, are located along the shores and tributaries of Lake Malawi, a fragile ecosystem and key source of livelihood for lakeside communities of more than 1.5 million people. In 2009, Paladin (Africa) Limited, a Malawian-incorporated subsidiary of Australia-based Paladin Energy Ltd., started production in Malawi’s first large-scale uranium mine, with around 10,000 tons of yellowcake uranium deposits and a projected capacity of 1,500 tons of yellow cake uranium a year.[12] While the mine is currently not in production because of declining uranium prices after the 2011 nuclear accident in Fukushima, Japan, Paladin remains on “care and maintenance," with the possibility of resuming activities in the near future. Exploration for uranium continues in other parts of Malawi such as Mzimba district.[13]

Malawi is also beginning to explore ways to further exploit its coal reserves totaling at least 22 million tons.[14] Malawi’s coal production declined from around 67,000 tons in 2013 to under 63,000 tons in 2014 due to fuel shortages.[15] In 2015 the four largest coal mines had a combined capacity of 10,000 tons per month, with an average workforce in the coal sector of around 600 people between 2013 and 2015.[16]

According to the World Bank-funded 2016 Strategic Environmental and Social Assessment of the Minerals Sector, the Department of Mines has issued 10 mining licenses and 13 prospecting licenses for coal. Most of these licenses were issued for areas located in northern Malawi, including the Lufira coal field where the Eland coal mine is located and the North Rukuru coal field where Malcoal Mining Limited (Malcoal) operates.[17] The assessment also reports that several planned coal power plants are set to open in Malawi, which could increase coal mining and production.[18] In 2015, Chinese companies announced intentions to invest in coal power plants in the Mwanza District of southern Malawi.[19] The cost of a new plant is estimated at $600 million, the bulk of which will be carried by a Chinese bank with contributions from the Malawi government.[20]

Further exploration for oil and gas extraction are underway, including in areas around the lake that are protected UNESCO World Heritage sites. The government started to issue petroleum exploration licenses between 2011 and 2014, awarding prospecting licenses to four multinational companies.[21] Criticism from civil society and allegations of corruption voiced by the attorney general slowed the licensing process down and the attorney general recommended a cancelation of the exploration licenses.[22]

In 2014 UNESCO published a report warning of the risks to Lake Malawi’s ecosystem and asking the government not to issue exploration licenses for areas within the national park.[23] With respect to threats originating outside the protected area, the report also recommended that the government “[p]revent[s] pollution of the lake and its inflowing rivers through effective regulation and control of mining effluents, other industrial and domestic pollution and agrochemicals.”[24] In the same year, the World Heritage Committee urged “the State Party to cancel the oil exploitation permit which overlaps with the property and reiterated its position that oil, gas and mineral exploration and exploitation are incompatible with World Heritage status.”[25] In July 2016, the committee reiterated its recommendations from 2014 and requested a progress report on their implementation in February 2017 and again in December 2017.[26]

Poverty and Impacts of Climate Change

Today, Malawi remains one of the world’s poorest countries. A series of droughts and floods in 2015, followed by another long period of drought in 2016, adversely impacted Malawi's economy, which is heavily reliant on its agricultural sector.[27] The country's GDP growth slowed from 6.2 percent in 2014 to 3 percent in 2015, and inflation has been growing rapidly.[28] These droughts have caused numerous food shortages, especially of maize, leading to increased food insecurity in the country.[29] In April 2016, the government declared a state of national disaster after drought conditions continued on from the 2015 season. To help the country weather the economic storm caused by the droughts, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) recently released to Malawi $76.8 million in extra loans, which is in addition to existing programs.[30]

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and other scientific studies, the African continent is already experiencing the effects of climate change in many regions.[31] For example, a recent study characterized countries in southern Africa as “global hotspots” of climate change, noting a high likelihood of drought or flooding and declining crop yields or ecosystem damages in the future.[32] The effects of climate change will put an additional strain on local economies, which already see increasing poverty and high population growth rates.

While Malawi’s current carbon emissions are among the lowest in the world—about 0.1 metric tons of carbon dioxide emission per capita—increasing fossil fuel extraction, including coal mining, contributes to global climate change, which in turn affects food security.[33]

Human Rights Concerns

The extractive industries can be a highly destructive and dangerous industry if not managed and regulated responsibly.[34] Researchers and activists around the world also increasingly perceive it to be an industry that benefits foreign investors while the local economy sees little benefit, and, most importantly, local communities are left empty-handed.[35]

Critics have long alleged that the push for industrialization and growth needs to be accompanied by a government-regulated“social license”—a legal and policy framework to ensure that local communities will not suffer harm—instead of leaving social responsibility to the discretion of mines and other industrial projects.[36] Even the world’s major mining firms generally acknowledge that mining can be dangerous when not carried out responsibly and that painstaking evaluation of possible negative impacts is imperative.[37] In particular, mining activities can impact several fundamental human rights, including the rights to health, water, food, and housing.

Negative health risks are common in mineral mining. The risks are especially high in uranium mining due to its radioactivity and toxicity.[38] Individuals who work in or live near uranium mining activities can face a broad array of health challenges associated with exposure to uranium, including cancers and kidney and respiratory diseases.[39] While most existing studies focus on the health impact of uranium mining on miners, several studies show that uranium can also lead to health problems in nearby communities.[40] Manifestations of negative health impacts are often delayed, however, because the initial cell damage is not lethal.[41]

Health outcomes are also worsening for individuals who work in or live near coal mining activities. Rates of illnesses such as lung and other types of cancers, respiratory and kidney diseases, heart attacks, and high blood pressure are increasing within these communities.[42] Air contamination caused by mining activities affect the health of nearby communities. For example, fugitive dust, small airborne particles generated by the blasting of heavy equipment used in surface coal mining, contains particulate matter that can be toxic to human health.[43] Also, the transport of coal releases dust and rocks, particularly when trucks are uncovered, which can cause respiratory symptoms in surrounding communities.[44] Children in these communities often suffer increased rates of asthma.[45]

Finally, mining also significantly contributes to climate change, which in turn adversely impacts governments’ ability to realize the rights to health, water, and food. Although disaggregated statistics covering the global mining sector are not available, mining has been recognized as a significant contributor to human-made climate change by emitting significant amounts of greenhouse gases during production and through the extraction of fossil fuels.[46]

Minimizing Risks and Protecting Rights

International law requires governments to take effective steps to minimize or mitigate risks and harms stemming from mining operations and to monitor and respond to resulting impacts.[47] Human rights law also imposes procedural obligations with regard to access to information, participation in the formulation and implementation of government policy, and access to a remedy. These obligations are meant to protect the rights of local communities before, during, and after mining operations.[48]

On company responsibilities, the United Nations (UN) Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (Guiding Principles) detail basic steps companies should take to respect human rights, including conducting due diligence to avoid causing or contributing to human rights abuses through their operations; avoiding complicity in abuses; and taking steps to mitigate them if they occur. Several voluntary industry initiatives similarly emphasize the important role of risk assessments and regular and transparent monitoring.[49]

First, governments and companies should take preventive measures to ensure that mining projects are planned and carried out in a way that does not violate the rights of local communities and that minimizes displacement and disruption of livelihoods. A central element of any efforts to minimize risks is to assess environmental and social impacts throughout the lifecycle of mining. Governments’ obligations under international human rights law to protect and prevent mean they should investigate the actual and potential implications of mining operations, including generating and collecting information related to environmental and social impacts before mining starts. Data collection should include assessments of:

- Hazardous properties and other potential risks from mining;

- The likelihood of impacts on community members, including those at higher risk;

- The risk of harm to people, communities and the environment; and

- Options that are available to prevent harm.

Impact assessments for mining operations should include baseline data for pollutants in water, food, and other natural resources and should evaluate how the project will affect marginalized groups and individuals. Land use also requires careful planning and robust monitoring to minimize the impacts of resettlement on the rights of affected communities.

Second, governments should establish effective mechanisms to oversee the activities and impacts of mining during and after operations and publish updates on the potential health and environmental risks. Such mechanisms involve robust reporting requirements for companies and regular unannounced inspections by the government. Affected groups and individuals should be given the opportunity to contribute to monitoring activities, and data should be disaggregated. Governments should also ensure that adequate healthcare infrastructure is in place to monitor the potential health impacts of the mining activity on communities.

Third, governments should effectively disseminate information to communities that may be adversely affected by operations of the extractive industries before, during, and after operations. Access to information is a prerequisite for communities to participate in discussions with the government and mining companies. Meaningful participation relies upon, and cannot be achieved without, information. Participation also helps to ensure that development projects involving land and natural resources adequately and equitably address the rights of affected communities. The availability and accessibility of information also enables affected communities—especially those vulnerable to mining’s potential impacts—to seek redress for harms suffered.

II. Gaps and Weaknesses in Malawi’s Legal Framework

The 1981 Mines and Minerals Act (MMA) is the principal law currently governing mining in Malawi, and provides for the licensing and regulation of private mining companies. It also contains a section setting out some environmental protection standards throughout the lifecycle of mining.[50] General standards for protecting the environment, including Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs), and monitoring are laid out in the 1996 Environment Management Act (EMA). The 1983 Petroleum (Exploration and Production) Act governs oil exploration and production. The 2013 Water Resources Act regulates the use of natural water sources for mining activities and the discharge of water from mining operations.

Discretionary Protection and Monitoring Standards

Malawi’s legal and regulatory framework does not ensure proper assessment of the risks from environmental pollution before the mining starts and fails to effectively protect the rights of nearby communities by rigorous monitoring during and after operations. Environmental and social impact assessments and ongoing monitoring are intended to ensure scrutiny and rigor in evaluating the possible negative impacts of proposed new mines and in developing mitigation strategies. Unfortunately, weak regulations for impact assessments and monitoring have rendered this key safeguard largely ineffectual in Malawi.

First, legal standards for EIAs leave too much discretion to authorities. While impact assessments should be mandatory for all projects that potentially impact the environment and community health, Malawi’s regulatory framework on EIAs for mining operations remains incomplete and unclear. Per the MMA it is at the minister’s discretion to require an EIA to be carried out before a license for a mining project is approved.[51] The EMA in conjunction with the 1997 Guidelines for Environmental Impact Assessments (EIA Guidelines) have been interpreted to impose mandatory EIAs for mining projects, but the EIA Guidelines are vague about the types of mining projects that require an EIA.[52] In any event, the current environmental legislation entirely fails to require applicants to evaluate the social impacts of mining on nearby communities.

An additional problem is the weak provisions on public participation during the EIA process. According to Section 26 (1) of the EMA, the public will be invited to send written comments on the EIA, but the nature and structure of public hearings remain at the discretion of the director of environmental affairs (“where necessary”). Furthermore, consultation is not mandatory prior to the commission of the EIA. While the EIA Guidelines are slightly more emphatic about the role of public consultation in the EIA process, the government’s role in ensuring meaningful participation remains discretionary.[53]

Second, Malawi’s mining law provides little guidance with regard to the environmental impacts of mining. In considering whether or not to approve a project, the director is required to “take into account” any likely environmental impact of the project.[54] This provision is weak and highly discretionary, as neither the EMA nor MMA specify the ways in which this impact should be measured or the criteria that need to be fulfilled for the project to go ahead.

Third, according to the EMA, the director of environmental affairs shall conduct “periodic environmental audits of any project” after a project has been approved and begun operating.[55] However, the current law does not specify how often these audits should be carried out and what they entail. As a result, regular monitoring and enforcement of environmental protection measures remain at the discretion of the director and the implementing entities such as the district environmental officers.

|

Integrating Human Rights Risks into Impact Assessments Neighboring countries in southern Africa have found ways to incorporate social impacts, especially impact on human health, into the legal regime for environmental assessments with varying levels of implementation.[56] In Zambia, the 2015 Mines and Minerals Law requires authorities to consider environment and human health “in deciding whether or not to grant any mining right or mineral processing licence.”[57] According to Section 80 (1) b “the need to ensure that any mining or mineral processing activity prevents any adverse socio-economic impact or harm to human health, in or on the land over which the right or license is sought” shall be taken into account.[58] There are several tools that help governments develop specific guidelines to assess the impacts of mining on marginalized groups and individuals.[59] For example, the Social Water Assessment Protocol developed by Nina Collins and Alan Woodley at the Centre for Social Responsibility in Mining at the University of Queensland, Australia includes modules on gender, indigenous peoples, and health.[60] A pilot study in Ghana conducted an assessment on the basis of the water assessment tool, which was designed to capture the social context around mining operations and integrated human rights considerations.[61] The Toolbox for Socio-Economic Assessment, developed by the International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM) member and mining company AngloAmerican, covers a broad range of issues: stakeholder engagement, resettlement, indigenous peoples, planning for mine closure, and delivering benefits.[62] |

Legal Barriers to Accessing Environmental Health Information

While Malawi’s Constitution sets out various procedural rights that apply to environmental decision-making, such as the right of access to information, the current regulatory regime on mining does not promote access to environmental and health information.[63]

The current MMA contains provisions that could render any information delivered to the government for mining-related activities confidential. In particular Section 7 of the MMA, the Prohibition Against Disclosure of Information, could be read as preventing the release of environmental monitoring and related information for the duration of the mining license’s validity, unless both the director and the holder of the mineral right agree otherwise.[64]

While Section 52 of the EMA appears to emphasize the importance of access to information for the general public, the limitations contained in the same provision act to significantly limit this content. Section 52 (3) of the EMA contains a confidentiality provision relating to the publication or disclosure of proprietary information relating to the environment.[65]

|

Legal Provisions that Advance Access to Information Neighboring countries have adopted and implemented laws that promote transparency and public access to environmental information.[66] In Zimbabwe, the 2003 Environmental Management Act contains a specific provision on the right of access to environmental information.[67] The Access to Information and Protection of Privacy Act also contains provisions that seek to protect public health and the environment in Section 28 (1) (b). The law requires that the head of a public body disclose to members of the public or interested or affected persons information concerning the risk of significant harm to the health or safety of members of the public or the risk of significant harm to the environment. Such information is to be provided whether or not a request has been made to the public body.[68] In Tanzania, the 2004 Environmental Management Act states that documents including those relatingto environmental matters in any mining concession; environmental management plans; proposals for preventing pollution; plans for treating waste or reclaiming land and water resources; and environmental impact assessments for proposed mining operations are publicly accessible records.[69] Tanzania has also enacted the Extractive Industries (Transparency and Accountability) Act, which requires the minister of energy and minerals to publish—online or via widely accessible media—concessions, contracts, and licenses relating to the extractive industries and the implementation of environmental management plans.[70] |

III. Karonga District: Malawi’s Mining Experiment

Karonga is the northernmost district of Malawi, with Lake Malawi to the east, Tanzania to the north, and highlands to the west and south. The district was isolated until 1981, when the national highway was extended to the district from the south.

Still one of Malawi’s poorest regions, the majority of the district’s 250,000 residents depend on subsistence farming and international and governmental food aid. The terrain is flat and fertile along the lake and increasingly hilly toward the west. The main sources of income for most families are farming maize, rice, and cassava and fishing in the lake.

Momentum and national interest in Karonga’s extractive industries was first ignited by the commissioning of Kayelekera’s uranium mine in 2007. Kayelekera is a community consisting of nine villages and located 52 kilometers west of Karonga amid rolling hills covered with patchy forest. It is located about halfway between the district capital of Karonga town and Chitipa. The population in this area has grown significantly over the past decade—in part due to an influx of migrant laborers—with about 3,000 people living there at its peak in 2009.[71]

The uranium mine in Kayelekera is the largest mine in Malawi. In fact, it is the first and only large-scale mine defined by heavy equipment, sophisticated technology, and a workforce in the hundreds of employees.[72] The mine, which became fully operational in 2009, is operated by Paladin—a company based in western Australia—while the Malawian government maintains a 15 percent stake. Between 2011 and 2014 the mine’s output was near capacity, producing about 1,000 tons of yellowcake per year.[73] In 2014, operations were temporarily stopped due to low uranium prices globally, with the mine placed on so-called “care and maintenance,” but the company continues to employ over 200 workers.[74]

Several other mining ventures followed Paladin’s example. These include Karonga-based Malcoal and Eland Coal Mining that are two of the country’s four biggest coal mines, along with Mchenga and Kaziwiziwi in Rumphi district. Together, these mines make up 95 percent of the total coal production with a combined capacity of 10,000 tons per month.[75]

|

Mine |

Ownership |

Sector |

Location |

Start of operations |

Status in August 2016 |

|

Malcoal (coal mine) |

Malcoal (Malawi), subsidiary of IntraEnergy (Australia) |

Coal |

Kayelekera, Karonga |

2006 |

Active |

|

Eland (coal mine) |

Eland Coal Mining Company (Malawi), subsidiary of Independent Oil Resources (Cyprus) |

Coal |

Mwabulambo, Karonga |

2009 |

Closed |

|

Kayelekera (uranium mine) |

Paladin Africa Limited (Malawi), subsidiary of Paladin Energy Ltd (Australia) |

Uranium |

Kayelekera, Karonga |

2009 |

On Hold |

The Malcoal open pit coal mine is based on the back of a mountain close to a river, about 3 kilometers from the Paladin mine. Formerly known as Nkhachira, the mine was taken over by Malcoal in 2013.[76] As of June 2015, Malcoal was a joint venture with 90 percent owned by Australian Intra Energy Corporation (through its subsidiary East Africa Mining Limited) and 10 percent owned by Consolidated Mining Industries Limited, a private Malawian entity.[77] Malcoal was reported to have closed down operations because of a shrinking local market at the end of 2015, but the mine was operational as of July 2016.[78] Intra Energy has also announced plans to construct a coal-fired power station at Chipoka, Salima, with coal supplies coming from the mining site in Kayelekera.[79]

Mwabulambo coal mine, an open pit mine located 30 kilometers north of the district capital, is operated by Eland Coal Mining Company, a Malawian company. Eland is a subsidiary of the Isle of Man based Heavy Mineral Limited, which is in turn owned by Independent Oil & Resources PLC, a company based in Cyprus.[80] Over 70 percent of Independent Oil & Resources PLC is owned by the Norwegian oil magnate Berge Gerdt Larsen and members of his family.[81] The coal mine is located on a flat and fertile area near Lake Malawi where residents have traditionally relied on subsistence farming, especially rice farming. It is unclear when and if operations will resume after they stopped in 2015. According to information given by Jan Egil Moe, chairman of the board of Independent Oil & Resources PLC, in July 2015, “Eland Coal Mine has suspended operations as the operations were not sustainable, and is in the process of being liquidated.”[82] However, site visits in August 2015 and March 2016 suggested that the company still employs a local watchman and has not started rehabilitating the area.

Before Mining Starts

In Malawi’s Karonga district the government and companies have failed to comprehensively assess environmental and social risks and impacts before mining operations begin and have not communicated potential risks with affected communities.

Insufficient Consultation about Risks of Mining

Silence reigns in this country over the mining issue, especially uranium.… When ignorance reins, it’s the poor that suffer. Nobody, whether mine or government officials, takes responsibility to educate people on the hazards of mining. People lack basic education about uranium and coal mining.[83]

—Archibald Mwakasungla, chairman of Uraha Foundation, Karonga, August 2015[84]

Many residents of mining communities, especially women, interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that they did not receive sufficient information about mining and its potential risks before the operations started.

One woman at Mwabulambo, where Eland started operating in 2007, said that she “didn’t know anything about the mining before the machines came in.”[85] "They didn’t give us any information, they just started digging,” she said. Another female resident of Mwabulambo “just saw vehicles coming through…. No government official came to tell us what was going on.”[86]

A 46-year-old woman in Mwabulambo recalled:

The first thing I remember was that a white man came into the village and asked children about the rocks in this area. The people found out that there is coal. They started talking to the government, but they didn’t discuss their plans with us. They only told us that we would all become very rich once they start with the mining. We didn’t know anything about mining and we believed them.[87]

EIAs are supposed to be carried out before mining starts production, and according to EIAs reviewed by Human Rights Watch, companies held community meetings in Mwabulambo and Kayelekera before the mining started or at an early stage of exploration. However, it is not clear how inclusive and comprehensive these consultations were. The EIA for Eland coal mine explicitly states that “[a]lthough a lot of effort was made to ensure gender balance …, women, especially at village levels, were not keen to provide their comments and inputs.”[88] The EIA for Nkhachira Coal Mine, Malcoal’s predecessor, reports that the managing director informed the people that there is a “requirement for establishment or improvements of some infrastructures including health center, Police Unit, potable water, maize mills, roads and many more,” but does not mention any potential risks posed by coal mining.[89]

Villagers interviewed by Human Rights Watch in fact emphasized that the community meetings, if they happened at all, often did not include information about how the project would impact the environment and their livelihoods, including planned use of land, water, and other natural resources.[90]

The minister of mining pointed out that the Mwabulambo and Kayelekera communities’ knowledge about the health centers and schools promised by the companies can be seen as a “sign that they [the communities] have been consulted, otherwise they wouldn’t know that there is a promise.” [91] However, even if this type of information was given prior to the start of mining operations, promising benefits to the community cannot be a replacement for providing adequate information about the associated risks and mitigation strategies. [92]

Government officials confirmed that the current legal framework does not require companies to include and communicate social impacts and health risks of mining, such as threats to water sources or specific impacts on marginalized populations, and does not provide for avenues through which communities may access environmental health information.[93]

|

Environmental Impact Assessments The 2006 EIA for the Nkhachira coal mine in Kayelekera, which was taken over by Malcoal in 2013, stated that the environmental risk of the mine was “minimal.” However, a Human Rights Watch review found that it failed to comprehensively address the potential impact of mining activity on ground water or surface water, including the risk of acid mine drainage.[94] While the EIA indicated that the nearby community would experience greater levels of dust, noise, and traffic that would negatively impact their quality of life, it contained no recommendation for regular monitoring of the local water and air during or after the mine’s operation. [95] The EIA for the Eland coal project, which Human Rights Watch also reviewed, stated that there was “minimal environmental risk.”[96] The only step it identified to minimize health risks to the community was to prohibit access to the mine site, stating that “any trespassers to be disciplined by the village committee.”[97] The report made no mention of any potential impacts on women or children or how the risks were to be communicated to them. Australian experts on the environmental impact of mining criticized Paladin’s EIA, conducted in 2006 by Knight Piésold Ltd consulting firm, because it lacked adequate, high quality environmental and radiological baseline data; an appropriate long-term tailings management plan; adequate characterization and discussion of potential acid mine drainage issues; and it provided an inappropriate rehabilitation plan.[98] Human Rights Watch’s review found that the EIA also failed to discuss gender specific risks of mining and that it was unclear if and how the results of their monitoring programs would be made available to the general public, especially to women.[99] |

Relocations

The company put white crosses on all the houses that should be relocated. They also put such a cross on our house…. They first came in March 2012 and said that we need to move in April. But they only waited one week and then came back to say that now is the time to move. We didn’t know where to go. We had to sleep outside for a couple of days. It was difficult to move as this was in the rainy season and we ended up putting up at someone’s verandah and under the tree.[100]

—Resident, Mwabulambo, March 2016.

Mining in Karonga district has resulted in the resettlement of some families often without adequate warning, decent resettlement conditions, or compensation.

Malawi’s laws and policies do not adequately regulate resettlement or land transfers for commercial investment. Although Malawi’s Constitution, the Land Act, and the Mines and Minerals Act (MMA) offer some standards for compulsory land acquisition through the government, they do not provide adequate safeguards or sufficient guidance on this process or related compensation.[101]

Government officials from the Ministry of Lands, Housing and Urban Development told Human Rights Watch that the land acquired by mining companies in Karonga district was customary land. Community members and NGO representatives also mostly suggested that this was previously customary land.

When the government claims customary land, they bear the responsibility of resettling and compensating those using such land. According to the constitution, “[f]air and adequate compensation must be given in the event of compulsory acquisition.”[102] The Land Act also stipulates that “any person who … suffers any disturbance … loss or damage to any interest which he ... may have … in such land, shall be paid such compensation for such disturbance, loss or damage as shall be reasonable.”[103] With regard to mining, the MMA also provides for fair and reasonable compensation for disturbance of land rights and damage to any crops, trees, buildings, stock, etc.[104]

However, the principal secretary at the Ministry of Lands, Housing and Urban Development told Human Rights Watch that people who have been using customary land in mining communities will not be compensated for the land as such because they do not possess a land title.[105]

Neither of the existing laws defines what “reasonable” compensation is and, to date, Malawi does not have a national resettlement policy that guides the process of resettlements and compensation.[106] This exacerbates a broader problem of insecure land tenure, especially for customary land that is communally owned.[107]

|

Land Tenure in Malawi There are a variety of land laws in Malawi which establish various types of tenure. The 1965 Land Act categorizes land as public (government or unallocated customary land) or private (freehold, leasehold, or customary estate).[108] The 2016 Land Bill comprises more than 10 land-related bills, including bills on customary law, land acquisitions, physical planning, and the role of local government role.[109] A new customary law was adopted by parliament in July 2016 and was assented into law by the president in September 2016. Very few people in rural Malawi have private land titles.[110] Approximately 80 percent of all land in Malawi is considered customary land under Malawi’s 1965 Land Act. Customary land is defined as land falling within the jurisdiction of a recognized traditional authority.[111] In the northern region of Malawi, 83 percent of all land is held as customary land.[112] In the district of Karonga, the share of customary land amounts to 98 percent.[113] Although a preponderance of communities in Malawi pass customary land down from mother to daughter (matrilineal), in the northern region most villages use a patrilineal system, passing land down among male heirs. In Karonga, 99 percent of land is patrilineal.[114] |

Under the Land Acquisitions Act, compensation is determined by the lands commissioner or by agreement between parties.[115] According to Section 9, if compensation is not agreed upon by the parties, it will be assessed by the government. Criteria to be considered when calculating compensation are the value of the land, the value of the improvements made to the land, and how much the land has appreciated in value since the land was originally acquired.

According to the Ministry of Lands, Housing and Urban Development, the process of assessing compensation is carried out by the regional offices of the ministry.[116] The results will be shared with the affected people and district commissioner who will be responsible for implementation.

Further guidance for resettlement in the case of government seizure of customary land can be found in the 2013 Mines and Minerals Policy and the 2002 National Land Policy. According to the Mines and Minerals Policy, “[c]ompensation and resettlement of land owners and communities affected by mining” is identified as a social issue that “the government will adequately address.”[117] According to the National Land Policy, “all land acquisition, including the acquisition of customary land, by the government requires negotiations and payment of compensation at fair market prices.”[118]

While these policies state that it is the responsibility of the government to compensate and resettle those displaced in mining activities, the National Land Policy indicates the mining companies also bear some responsibility. Specifically, the policy states that “mining rights will include conditions for practicing conservation methods including setting aside funds for compensation to those adversely affected by the activity and mining and quarrying operators will be required to meet the costs of reclaiming land.”[119]

With no national guidelines or regulations on resettlement, the mining companies operating in Karonga district have been inconsistent in how they go about this process.[120]

Although the Karonga district commissioner told Human Rights Watch that relocation processes fall under her authority, they said they were unaware of the current situation of relocated families at the Eland or Malcoal mines.[121] The principal secretary at the Ministry of Lands, Housing and Urban Development said that they were not aware of any irregularities in the relocation processes in Karonga district.[122]

Complicating the relocation process is the role of local chiefs in negotiating deals for resettled families when customary lands are involved. Both Malawi’s 1967 Land Act and the 2016 Customary Land Bill reaffirm the notion that customary land is administered by the chiefs for the community.[123] In recent years, however, numerous conflicts over land have arisen because chiefs appear to have participated in land deals without fully consulting local residents or gaining their consent.[124] In an interview with Human Rights Watch, Karonga District Commissioner Rosemary Moyo said that, in some cases, chiefs may have taken some of the money meant for the resettled families.[125] Several villagers in Kayelekera and Mwabulambo said that they believed the chiefs had received money from the companies in exchange for agreeing to the relocations.[126] Asked about the allegations of corruption levied against him, Chief Kayelekera told Human Rights Watch: “Whenever I answer questions people will say I am saying the wrong thing.”[127]

In Kayelekera, community members said that Malcoal resettled at least 12 households about 5 kilometers away from the actual mining site in September 2013.[128] A school teacher confirmed to Human Rights Watch that the 12 families who were moved lived next to the Malcoal offices, across the street from the primary school.[129] Even though some of the families had already heard about the planned relocation, three families told Human Rights Watch that they did not know when the move was going to happen. In the process, furniture was destroyed and several animals were killed. A 20-year-old woman at Kayelekera recalled:

The people from the company came to us and said they wanted to build a police station where our house was.… They didn’t give us any notice and just chased us away. Two of our goats died because of a bulldozer. They were in a cage and couldn’t escape while we were busy protecting our furniture.… We couldn’t say anything because the machines were already there. We didn’t manage to save all our belongings. We lost some pots, bags and many other things.[130]

Another woman, whose family was contacted by Malcoal’s workers in June 2013, said that the company had told her family that they “could come any time to make us move.”[131] Three months later, company workers came back to tell them that they have to leave. “They came with bulldozers and told us to pack our stuff immediately,” she said.[132]

Malcoal disputes the assertion that Malcoal has resettled community members. Mr. Hastings Jere, director of Malcoal, said in an email to Human Rights Watch that there was “not even a single villager or village … to be relocated to pave way for mining.”[133] The company did not specifically respond to our request for further information about any resettlements at a later stage, or to the accounts provided by families who reported that they were relocated from their homes, which were near the Malcoal offices.

In Mwabulambo, community members said that more than 30 households were relocated from customary land at different stages of Eland’s operations between 2008 and 2015. Human Rights Watch interviewed individuals from four of these households.[134] They complained that the company did not notify them sufficiently in advance of the resettlement, and they criticized the company and the government more generally about a lack of transparency regarding the terms of the relocation and compensation. [135] They reported that, while they had heard about the relocations before, the actual timing of the resettlement came as a surprise, and they had to leave their homes before they managed to build new ones. One family even had to stay under a tree for about a month because they had to move so quickly.[136]

Eland Coal Mining Company did not respond to our request for information about the resettlement process in Mwabulambo.

In Kayelekera, none of the relocated families Human Rights Watch interviewed said they had received compensation for any of their losses when they were resettled by Malcoal. “We had to ask the chief for new land and had to pay 30,000 MWK (about $90) for it. We had also lost our fields and needed to buy new ones,” one woman said. “The company didn’t pay us any compensation.”[137]

Another family in Kayelekera said that Malcoal’s manager had initially promised to compensate them. “In June 2013 [Malcoal] workers came and wrote down our name and assessed the value of our house. They said that they could come any time to make us move and that we may receive compensation,” the woman remembered. But when the company workers came back three months later, “they came with bulldozers and told us to pack our stuff immediately. They didn’t say anything about compensation anymore.”[138]

In Mwabulambo, each family received some form of compensation from Eland when it relocated them, ranging from 50,000 to 200,000 MWK (about $150 to $600), but the basis for individual payments remains unclear.[139] A community representative interviewed by Human Rights Watch suggested that these were standard amounts that the company paid to each relocated family—independent of the actual value of their belongings—and that they had increased payments over time in response to mounting pressure from the community.[140] A representative of a local NGO who worked with the community for many years said “no one knows” the formula used to determine compensation.[141] A 58-year-old widow and mother of 12 said: “We were never told why we received 50,000 MWK (about $150). They just told us this is the amount you get.”[142] Another family who had also been paid 50,000 MWK (about $150) had to sell two cows to be able to build a new house.[143]

Several families said they could not maintain the same standard of living after resettlement due to the minimal compensation they received. A woman from Mwabulambo said:

Even though they offered us very little money, we had no choice but to move. They said that they own the land and put us under pressure. We didn’t have the power to resist and we were afraid of the risks of coal. 50,000 MWK (about $150) is too little money. We had a brick house in the old location. But the money wasn’t enough to build a new one, so now we only have a mud house.… The area where we had our fields was also taken away by the miners. There is only a small part that we can still use.[144]

In addition to the lack of adequate compensation for the house and other property, several families told Human Rights Watch that the relocation had reduced their income because the new land they acquired after the move was not as fertile. A woman in Kayelekera told Human Rights Watch that her family was relocated to “a really bad piece of land” by Malcoal in 2013. She explained that the land from where they were moved had good soil; she was able to grow maize, cassava, sweet potato, and groundnuts. She used to harvest 30 to 50 bags of maize per season, but now she only has 10 bags or less.[145] Another woman from Mwabulambo who was relocated by Eland said: