Summary

Security forces in the Democratic Republic of Congo killed at least 62 people and arrested hundreds of others during protests across the country between December 19 and 22, 2016, after President Joseph Kabila refused to step down at the end of his constitutionally mandated two-term limit.

As people took to the streets – blowing whistles, banging on pots and pans, and shouting that Kabila’s time in office was up – government security forces fired live ammunition and teargas at the protesters. Some witnesses heard soldiers yell at them: “We are here to exterminate you all!” Activists and opposition leaders were thrown in jail in the days leading up to and during the protests, while security forces wounded, threatened, detained, or denied access to international and Congolese journalists covering the protests. In the aftermath of the demonstrations, authorities denied relatives access to hospitals and morgues, making it impossible for many families to bury their loved ones.

In the lead-up to the December protests, and as domestic and international pressure on Kabila escalated, senior Congolese security force officers had mobilized at least 200 and likely many more former M23 rebel fighters from neighboring Uganda and Rwanda to protect Kabila and help quash the anti-Kabila protests.

The M23 combatants were recruited between October and early December 2016 from military and refugee camps in Uganda and Rwanda—where many M23 fighters have been based since the armed group’s defeat in eastern Congo in November 2013. Once in Congo, the M23 fighters were deployed to the capital, Kinshasa, and the eastern and southern cities of Goma and Lubumbashi. They were given new uniforms and weapons and integrated into the police, army, and units of the Republican Guard, the presidential security detail. Congolese security force officers—including many from previous Rwandan-backed rebellions who had since integrated into the Congolese army—looked after them, paying them well and providing them with food and accommodation. To protect the president and quash protests, the M23 fighters were given explicit orders to use lethal force, including at “point-blank range” if necessary.

“Many M23 were deployed to wage a war against those who wanted to threaten Kabila’s hold on power,” one M23 fighter told Human Rights Watch. “We received orders to shoot immediately at the slightest provocation by civilians,” another said.

Many of the recruited M23 fighters were sent back to Uganda and Rwanda in late December and early January 2017. Congolese security forces again covertly recruited M23 fighters from Rwanda and Uganda between May and July 2017. They were sent to Kisangani in northeastern Congo where they were awaiting training, allegedly to prepare them for future “special operations” to respond to any threats to Kabila’s hold on power.

This report documents the repression of peaceful protesters, activists, journalists, and political opposition leaders and supporters in Congo in December 2016 and the covert recruitment of members of an abusive armed group, the M23, to help carry out this repression. With more protests planned in the coming weeks – nearly one year past the end of Kabila’s constitutional mandate – the findings in this report raise concerns about further violence and repression.

Following the days of violence around December 19, 2016 and significant international and regional pressure, Kabila’s ruling coalition agreed to a Catholic Church-mediated power-sharing agreement with the main opposition coalition on December 31. The deal called for presidential elections to be held by the end of December 2017 and included a clear commitment that Kabila would not run for a third term or amend the constitution. Yet Congo’s ruling coalition defied key tenets of the so-called New Year’s Eve agreement, failing to organize elections or implement the confidence-building measures to ease political tensions.

On November 5, 2017, the national electoral commission (CENI) published an electoral calendar, setting December 23, 2018 as the date for presidential, legislative, and provincial elections – more than two years after the end of Kabila’s constitutionally mandated two-term limit. The CENI also cited numerous financial, logistical, legal, political, and security “constraints” that could impact the timeline.

Leaders from civil society and the political opposition denounced the calendar as merely another delaying tactic to unconstitutionally extend Kabila’s presidency. They have called on Kabila to step down by the end of 2017 and for a transition without Kabila to be organized, led by individuals who could not be candidates in future elections and with the primary aim of organizing credible elections, restoring constitutional order, and allowing for a new system of governance where basic rights are respected.

Meanwhile, Kabila has sought to entrench his hold on power through corruption, large-scale violence, and brutal repression. Kabila’s refusal to step down in accordance with the constitution has plunged Congo into a web of political, security, human rights, and economic crises that have not subsided, and that could have devastating consequences for the entire sub-region. The covert operations to recruit former rebel fighters from an abusive armed group to protect Kabila and suppress any resistance, documented in this report, show how far Kabila and his coterie are willing to go to maintain their grip on power.

High-level engagement and sustained, targeted and well-coordinated pressure on Kabila and his government at the national, regional, and international levels are urgently needed to press Kabila to abide by the constitution and step down to allow for the organization of credible elections as soon as possible.

Glossary

Military, Law Enforcement, and Intelligence Agencies

Armed Forces of the Democratic Republic of Congo (Forces armées de la République démocratique du Congo, FARDC): created in 2003, the Congolese national army is estimated to have between 133,000 and 145,000 personnel. The force has a long record of serious human rights violations. Those responsible for abuses are rarely held to account. Furthermore, the government has a longstanding practice of integrating former fighters from abusive armed groups into the army without formal training or vetting to exclude those implicated in past abuses. President Joseph Kabila, who holds the rank of major general, serves as commander-in-chief of the army. Gen. Didier Etumba has been the army’s chief of staff since 2008.

National Intelligence Agency (Agence nationale de renseignements, ANR): under the control of the president, the agency is mandated to investigate crimes against the state, such as treason and conspiracy. In recent years, the ANR has arbitrarily arrested scores of human rights and pro-democracy youth activists and opposition leaders, many of whom were held incommunicado for weeks or months, without charge and without access to their families or lawyers. Some detainees were badly mistreated or tortured, including with electric shocks and a form of near-drowning. Local and international human rights monitors and Congolese lawyers have limited access to ANR detention centers across the country and in some places, like Kinshasa, have no access at all. Kalev Mutondo has been the director of the ANR since 2011.

National Police Force (Police nationale congolaise, PNC): created in 2002, Congo’s national police force is estimated to have some 100,000 police officers. Congo’s police have a record of abusive and corrupt behavior that has engendered distrust among the population. Gen. Charles Bisengimana was the acting and later official national police commissioner from 2010 until July 17, 2017, when he was replaced by Lt. Gen. Dieudonné Amuli Bahigwa, the former deputy chief of staff in charge of operations and military intelligence of the Congolese army.

Republican Guard (Garde républicaine): the elite presidential security detail made up of some 18,000 soldiers, including many from the former Katanga province (home province of Joseph Kabila’s father). The Republican Guard is mandated to protect the president, presidential premises, and “distinguished guests.” The Republican Guard is deployed at airports, border posts, and other strategic sites, and carries out security functions far beyond its mandated role, including protection and oversight of mines and other assets owned or controlled by the president’s family. Gen. Ilunga Kampete has been the commander of the Republican Guard since 2014.

Armed Groups in Eastern Congo

(Several dozen armed groups are currently active in eastern Congo. Here we only discuss current and former armed groups that are mentioned in this report.)

Congolese Rally for Democracy (Rassemblement congolais pour la démocratie, RCD): a former Congolese rebel group backed by Rwanda, active during the “second Congo war” from 1998 to 2003.

National Congress for the Defense of the People (Congrès national pour la défense du peuple, CNDP): Rwandan-backed Congolese rebel group established in 2006 ostensibly to defend, protect, and ensure political representation for the several hundred thousand Congolese Tutsi living in eastern Congo and several tens of thousands of Congolese refugees, most of them Tutsi, living in Rwanda. The group’s fighters were responsible for widespread war crimes. Many CNDP fighters had been part of the RCD (see above). In early 2009, following a secret deal between Congo and Rwanda, CNDP fighters were integrated into the Congolese army and immediately participated in joint military operations with the Rwandan and Congolese armies against the FDLR (see below).

March 23 Movement (Mouvement du 23 mars, M23): a rebellion led by mostly Tutsi officers who had been part of the CDNP (see above), before integrating into the army in early 2009, then defecting in early 2012. The name comes from the March 23, 2009 agreement between the CNDP and the Congolese government, which the M23’s leaders said had not been respected by the government. The M23 relied on significant support from Rwandan military officials who planned and commanded operations, trained new recruits, and provided weapons, ammunition, and other supplies. Hundreds of young men and boys were recruited in Rwanda and forced to cross the border into Congo and fight with the M23. Between April 2012 and November 2013, when the group was defeated, M23 fighters committed widespread abuses, including summary executions, rape, and recruitment of children, including by force.

Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (Forces démocratiques de libération du Rwanda, FDLR): a largely Rwandan Hutu armed group based in eastern Congo. Some of its members participated in the genocide in Rwanda in 1994. Since then, Rwandan Hutu militias based in eastern Congo have reorganized politically and militarily, going through various name and leadership changes. The rebel group’s current configuration, the FDLR, was established in 2000. Its forces have been involved in numerous serious abuses against Congolese civilians. Since 2012, the group’s military commander, Sylvestre Mudacumura, has been sought on an arrest warrant from the International Criminal Court for nine counts of war crimes allegedly committed in eastern Congo in 2009 and 2010. He remains at large.

Nyatura: with the start of the M23 rebellion in early 2012, Congolese Hutu armed groups spread throughout Masisi territory and parts of Rutshuru, Walikale, and Kalehe territories in eastern Congo’s North Kivu and South Kivu provinces. New groups were formed and older groups re-established themselves. While many of these groups have their own individual names, or are named after their commanders, they are often referred to collectively as the Nyatura, which means “hit hard” in Kinyarwanda, a language spoken in Rwanda and by some in eastern Congo and southern Uganda. Nyatura fighters, often operating together with the FDLR (see above), have been responsible for widespread abuses, including summary executions, rapes, and recruitment of children, including by force. Since the M23’s defeat in late 2013, some Nyatura groups have allied with former M23 fighters.

Recommendations

To President Joseph Kabila

- Publicly order state security forces to end unlawful and excessive use of force and other forms of repression against protesters, activists, and the political opposition;

- Ensure an immediate end to all recruitment and deployment of M23 fighters by the Congolese security forces;

- Respect the constitution and the New Year’s Eve agreement by stepping down from the presidency by the end of December 2017.

To the Government of the Democratic Republic of Congo

- Take all necessary measures to stop the unlawful and excessive use of force by the security forces and other forms of repression against protesters and the political opposition;

- Investigate and appropriately prosecute those responsible for serious human rights violations, regardless of position or rank;

- Ensure that all Congolese, including civil society groups and opposition parties, are able to participate in peaceful demonstrations and other political activities without disruption;

- Release all political prisoners and end politically motivated prosecutions of individuals for exercising their basic rights to freedom of expression, association and peaceful assembly;

- Open all media outlets that have been arbitrarily shut down, and ensure that access to information, including independent international media outlets, social media platforms, and text message communication, is not blocked;

- Ensure that Congolese and international human rights defenders and journalists are able to work in Congo without interference;

- Support efforts to bring to justice M23 commanders implicated in war crimes, crimes against humanity and other serious abuses, in accordance with the Nairobi Declarations, signed in December 2013;

- Support the implementation of a credible Disarmament, Demobilization, and Reintegration (DDR) program for M23 combatants who are not wanted for serious international crimes, including long-term follow-up and support programs after they reintegrate into civilian life, in accordance with the Peace, Security, and Cooperation Framework for the Democratic Republic of Congo and the Region (“Framework Agreement”), signed in February 2013, and the Nairobi Declarations.

To the Governments of Rwanda and Uganda

- Cease any support by Ugandan and Rwandan officials to the recruitment and mobilization of M23 fighters in Uganda and Rwanda by the Congolese security forces;

- Investigate and prosecute as appropriate Rwandan or Ugandan civilian and military officials for unlawfully assisting the recruitment of M23 fighters;

- Cooperate with efforts to bring to justice M23 commanders implicated in war crimes, crimes against humanity and other serious abuses, and ensure that any such commanders who have fled to Rwanda or Uganda are not shielded from justice, as called for in the Framework Agreement.

To the African Union, Southern African Development Community, International Conference on the Great Lakes Region, and other regional leaders

- Publicly and privately denounce the unlawful and excessive use of force during protests in Congo, and the recruitment of M23 fighters to participate in suppressing these protests;

- In accordance with the Framework Agreement, seek to ensure that any arrangement between the Congolese government and the M23 excludes integration into the Congolese army of M23 leaders implicated in war crimes and other serious abuses, including those on UN and US sanctions lists;

- Press for the arrest and prosecution of military commanders, including members of the M23, implicated in war crimes and other serious abuses;

- Support a peaceful transfer of power by urging President Kabila to step down from the presidency and helping to ensure that concerns about Kabila’s physical security after he leaves office are addressed.

To the UN Secretary-General and Security Council and International Donors, including the EU, US, China, and International Organisation of La Francophonie

- Publicly and privately denounce the unlawful and excessive use of force during protests in Congo, and the recruitment of M23 fighters to participate in suppressing these protests;

- Seek to ensure that any arrangement between the Congolese government and the M23 excludes integration into the Congolese army of M23 leaders implicated in war crimes and other serious abuses, including those on UN and US sanctions lists;

- Press for the arrest and prosecution of military commanders, including members of the M23, implicated in war crimes and other serious abuses;

- Support the implementation of a credible Disarmament, Demobilization, and Reintegration (DDR) program for M23 combatants who are not wanted for serious international crimes, including long-term follow-up and support programs after they reintegrate into civilian life;

- Impose new targeted sanctions, including travel bans and assets freezes, against those most responsible for serious human rights violations in Congo. These should include senior government, intelligence, and security force officials implicated in the recruitment, support and funding of M23 fighters;

- Suspend all support to Congolese security forces, direct financial support to the Congolese government, and support to the electoral process until there is demonstrated willingness to organize credible elections and ensure a climate conducive to free, fair elections, and until concrete steps are taken to end widespread rights abuses across the country and hold those responsible, regardless of rank, to account. Such steps could include: a public, explicit commitment by Kabila that he will step down and will not seek to amend the constitution; the release of political prisoners and activists in detention; dropping politically motivated charges against political opposition leaders and activists; opening arbitrarily banned media outlets; and arresting and appropriately prosecuting senior officials responsible for serious human rights abuses;

- If the government does not implement such measures before the end of 2017, impose sanctions on Kabila himself and work with regional leaders to press Kabila to step down from power and help ensure that concerns about Kabila’s physical security after he leaves office are addressed;

- If Kabila does leave office before elections are organized, actively monitor and support efforts to establish a transitional authority, which would be led by individuals who could not be candidates in upcoming elections and which would have the primary aim of organizing credible, peaceful elections, restoring constitutional order, and allowing for a new system of governance based on the rule of law and strong democratic institutions;

- Continue support to the UN peacekeeping mission, UN agencies and nongovernmental organizations providing humanitarian and development assistance, and Congolese civil society and human rights organizations, including by redirecting any direct financial support to the Congolese government to these organizations.

To the UN Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of Congo (MONUSCO)

- Publicly and privately denounce the unlawful and excessive use of force during protests in Congo, and the recruitment of M23 fighters to participate in suppressing these protests, as well as other political repression and serious human rights abuses;

- Take all possible steps to protect civilians, including by using peacekeepers to deter violence and unlawful use of force by Congolese security forces in Kinshasa and other major cities;

- Be prepared to rapidly deploy peacekeepers to respond to serious security incidents and threats to civilians across the country;

- Support the implementation of a credible Disarmament, Demobilization, and Reintegration (DDR) program for M23 combatants who are not wanted for serious international crimes, including long-term follow-up and support programs after they reintegrate into civilian life.

To the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court

- Monitor the situation in Congo closely and undertake a visit to the country at an opportune time;

- Publicly denounce violence and repression in the country, and consider investigating recent serious crimes for possible prosecution.

Methodology

This report documents the repression of political protests around December 19, 2016, and the covert recruitment of M23 fighters from Uganda and Rwanda in late 2016 to participate in the suppression of protests.

Human Rights Watch’s findings are based on over 120 interviews, including with victims of abuses, witnesses, family members of victims, local activists, Congolese security force officers, Congolese government officials, UN officials, diplomats, and 21 former M23 fighters, commanders, and political leaders. [1] Human Rights Watch conducted field research in Kinshasa, Goma, and Lubumbashi in Congo and in Brussels, Belgium from December 2016 to November 2017, as well as during three research trips in Uganda and one in Rwanda in the first quarter of 2017.

Human Rights Watch interviewed 13 M23 fighters who were recruited between October and early December 2016 from Uganda and Rwanda and sent to Kinshasa (nine fighters), Goma (two fighters) and Lubumbashi (two fighters) to protect President Kabila and repress any anti-Kabila protests. All returned to Uganda or Rwanda in late December or early January. They were interviewed privately and individually – most had been in different groups and did not travel to Congo together. Human Rights Watch also interviewed six M23 commanders and political leaders who were involved in planning and overseeing the transfers but did not themselves travel to Congo, two M23 political leaders who were aware of the recruitment efforts, and several other individuals close to the M23 movement and witnesses present during the mobilization efforts or transfers.

Human Rights Watch interviewed nine Congolese security and intelligence officers who spoke without attribution about the operation, including five based in Kinshasa and four in Goma.

Due to security concerns, the names of many interviewees and other identifying information have been withheld. All interviews were conducted on the basis of informed consent. The majority of interviews were conducted in person; a few were conducted over the phone. No one was provided compensation for being interviewed. The interviews were conducted in French, Swahili, Lingala, Kinyarwanda, English, and German.

Human Rights Watch shared its research findings with senior Congolese, Rwandan, and Ugandan government officials and with the M23 political leadership in advance of publication of this report. The Congolese and Rwandan governments did not officially respond. The Ugandan response and the M23’s response are reflected in the findings of the report and included in Section VII.

I. Political Context

The Democratic Republic of Congo is facing a worsening political, economic, and security crisis. President Joseph Kabila was due to step down in December 2016 at the end of his constitutionally mandated two-term limit.[2] But he has managed to hold on to power by delaying elections and overseeing a brutal crackdown against those calling for the constitution to be respected.

Human Rights Watch documented the extrajudicial executions by security forces of at least 171 people protesting election delays in 2015 and 2016.[3] Many more were injured. The deadliest crackdown was during the week of September 19, 2016, when many Congolese took to the streets to protest the electoral commission’s failure to announce presidential elections, 90 days before the end of Kabila’s second term, as required by the constitution. Security forces responded with excessive force, killing at least 66 people and setting at least three opposition party headquarters on fire.[4]

Tensions escalated through December 2016, with the future of Kabila and the country increasingly uncertain. In the face of mounting national, regional, and international pressure—including targeted United States and European Union sanctions against top Congolese officials—President Kabila’s ruling coalition agreed to a Catholic Church-mediated dialogue with the opposition and some civil society representatives in late 2016.[5] A deal was signed on December 31, 2016, which included clear commitments to hold elections by the end of 2017 and that Kabila would not be a candidate or try to amend the constitution.[6] It further specified that the main opposition coalition, known as the Rassemblement, would lead the transitional government and a national oversight council, and that “confidence building” measures would be taken to open political space.

Yet nearly a year after the so-called New Year’s Eve agreement was signed, these commitments have largely been ignored while elections are far from sight. A prime minister was appointed who had been dismissed from the main opposition party, the Union for Democracy and Social Progress (UDPS), and the government and oversight council do not include any current members of the Rassemblement. The confidence-building measures have not been implemented, as the crackdown on political opponents continues.

Security forces killed at least 90 people as part of a crackdown against members of the Bundu dia Kongo (BDK) political religious sect protesting Kabila’s extended presidency in Kinshasa and Kongo Central province in January, February, March, and August 2017. Some of the BDK members also used violence, killing at least five police officers.[7] During a protest called by pro-democracy activists and opposition leaders in Goma on October 30, security forces shot dead five civilians, including an 11-year-old boy, and wounded 15 others.

Hundreds of opposition leaders and supporters, human rights and pro-democracy youth activists, and peaceful protesters were arbitrarily arrested and detained. Many were held in secret detention for weeks or months, without charge and without access to their families or lawyer. Others were put on trial on trumped up charges.[8] In July, unidentified armed men shot and nearly killed a judge in Lubumbashi who refused to hand down a ruling against opposition leader and presidential aspirant Moïse Katumbi.[9]

Authorities have also prevented international and Congolese journalists from doing their work, including by arresting them, denying access, or confiscating their equipment and deleting footage. At least around 40 journalists were detained in 2017.[10] Numerous Congolese media outlets close to the opposition have been shut down, at least five of which remain blocked at time of writing.[11] The signal for Radio France Internationale (RFI), the international news outlet most followed in Congo, was blocked in Kinshasa between November 2016 and August 2017, and in June 2017 authorities refused to renew the accreditation for the RFI correspondent in Congo.[12] The following month, the Reuters correspondent was unable to renew his Congolese visa.[13] Human Rights Watch’s senior researcher in Congo was also barred from the country in August 2016.[14]

Senior Congolese officials have blamed election delays, in part, on violence in the southern Kasai region, where up to 5,000 people have been killed, 1.4 million displaced from their homes, and 600 schools attacked or destroyed since August 2016.[15] Nearly 90 mass graves are scattered across the region,[16] and most are believed to contain bodies of civilians and militia fighters killed by government forces.[17] In March, two United Nations investigators—Michael Sharp, an American, and Zaida Catalán, a Swedish and Chilean citizen—were executed while investigating serious human rights violations in the Kasai region.[18] Human Rights Watch investigations and an RFI report suggest government responsibility for the double murder.[19]

The resource-rich country is also facing serious economic challenges, due in part to widespread corruption, a reluctance to invest in a country amid a political crisis and with an uncertain future, and a lack of transparency of Congolese government finances, including the state mining company.[20] The Congolese franc has lost over 30 percent of its value compared to the dollar in the past year. This has contributed to massive youth unemployment, families across the country struggling to make ends meet, and government employees getting reduced or late payments, or no salary at all.[21] In late June, the International Monetary Fund told the Congolese government that “a credible path toward political stability” will probably be a condition for any future financial assistance.[22] Meanwhile, the Kabila family has continued to enrich itself, with a “network of businesses that reaches into every corner of Congo’s economy,” according to investigations by the New York University-based Congo Research Group and the international financial media agency Bloomberg News.[23]

Due to the impasse in implementing the New Year’s Eve agreement, the Catholic bishops withdrew from their mediation role in March.[24] In June, they blamed the country’s dire security, human rights, economic, and political crises on the failure of a small group of people to hold elections in accordance with the constitution, and they called on the Congolese people to “stand up” and take their destiny into their own hands.[25]

On June 15, former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan and nine former African presidents launched an “urgent appeal” to Kabila and other Congolese leaders for a peaceful, democratic transition. They said that the future of the country is in “grave danger” and that the political crisis “represents a threat to the stability, prosperity and peace of the Great Lakes region, and indeed for Africa as a whole.”[26]

Officials from Congo’s southwestern neighbor Angola also appear increasingly concerned about Kabila’s inability to resolve the crises facing the country, including the violence in the Kasai region that forced more than 33,000 people to flee across the border into Angola.[27]

The EU and US imposed additional targeted sanctions against top Congolese officials responsible for serious human rights abuses and for attempts to delay or derail the elections on May 29 and June 1, 2017.[28]

In early November, days after US Ambassador to the UN Nikki Haley visited Congo and called on Kabila and other officials to organize elections by the end of 2018, the CENI published an electoral calendar, setting December 23, 2018 as the date for presidential, legislative, and provincial elections – more than two years after the end of Kabila’s constitutionally mandated two term-limit. The CENI also cited numerous financial, logistical, legal, political, and security “constraints” that could impact the timeline.[29]

Leaders from civil society and the political opposition denounced the calendar as merely another delaying tactic to unconstitutionally extend Kabila’s presidency.[30] They have called on Kabila to step down by the end of 2017 and for a “citizens’ transition” without Kabila to be organized, led by individuals who could not be candidates in future elections and with the primary aim of organizing credible elections, restoring constitutional order, and allowing for a new system of governance where basic rights are respected.[31]

Despite the mounting pressure, Kabila has shown no sign that he is preparing to step down or allow for a peaceful, democratic transition.[32] Activists and opposition leaders have called for more demonstrations in the coming weeks, and there is a risk of further violence and repression as Kabila and those around him may again seek to suppress protests and further entrench their hold on power.

II. December 2016 Crackdown

Prior to the end of President Joseph Kabila’s second and final term in office, according to the constitution, Congolese security forces deployed heavily in cities and towns across the country. Police and military forces patrolled the streets in armored vehicles and warned groups of 10 or more people gathered that they would be dispersed by force—including in Kinshasa, Lubumbashi, Goma, Bunia, Beni, Walikale, Kindu, Uvira, Kalemie, Mbuji-Mayi, Mbandaka, and Lisala. This appeared to be a deliberate attempt to deter protests and keep demonstrators off the streets. On December 19, 2016, the last day of Kabila’s mandate, there were “villes mortes” (literally “dead cities”), or general strikes, across the country; shops and businesses were closed, and people largely stayed indoors and kept their children home from school. Many of those who dared to protest were arrested or dispersed by security forces.

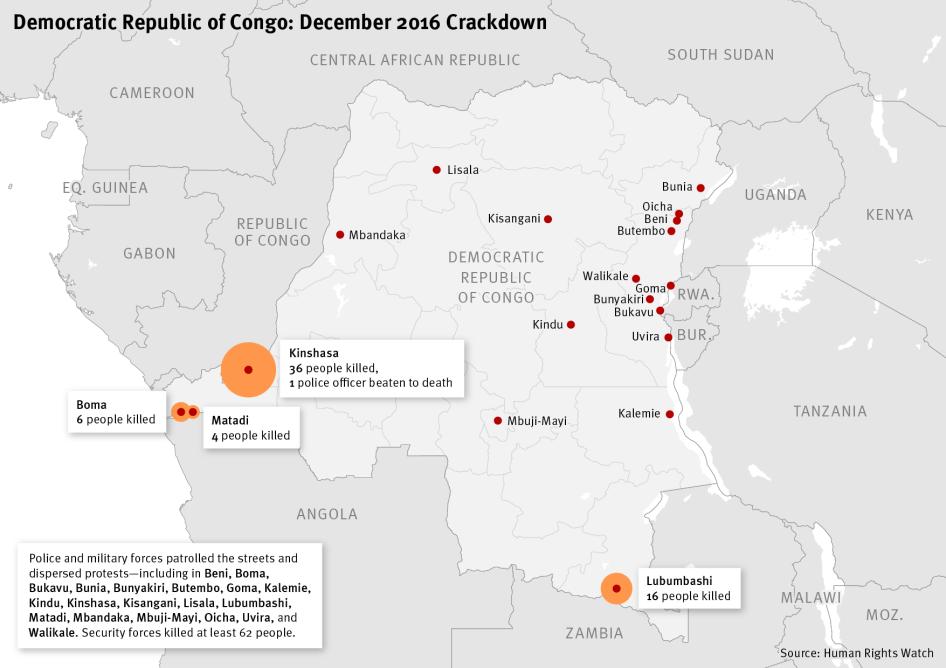

Beginning in the early hours of December 20—once Kabila was no longer seen by many to be the “legitimate” president—more people took to the streets, blowing whistles, banging on pots and pans, and shouting that Kabila’s time in office was up. Security forces, including the M23 combatants integrated into their units, used unnecessary and excessive force to quash the protests, killing at least 62 people between December 20 and 22, including 36 in Kinshasa, 16 in Lubumbashi, 6 in Boma, and 4 in Matadi. A police officer was also killed, reportedly by a stray bullet.[33]

Security forces also arrested hundreds of people in mid and late December while they were protesting or planning to protest, gathered outdoors in groups, or just wearing red—which had become a symbol of Kabila’s “red card,” a soccer reference telling him his time in power was up.[34] Many of the arrests in the days leading up to December 20 targeted activists and opposition youth leaders who were most active in organizing the protests and mobilizing participation. Arresting them in advance seemed to have had an important deterrent effect in limiting the scale of protests. In Kinshasa, Republican Guard soldiers conducted door-to-door searches in certain neighborhoods on December 20, arresting suspected protesters.

As part of a broader crackdown on the media, security forces also wounded, threatened, detained or denied access to at least 11 international and Congolese journalists covering the protests in Kinshasa, Mbuji-Mayi, and Goma around December 19, and they expelled five Belgian journalists on December 16.[35] On the morning of December 19, authorities blocked the signals of several Congolese news outlets close to the opposition.[36] They also instructed international telecommunication companies to shut down or restrict access to social media networks, in particular to prevent the sharing of photos and videos, including an appeal by the late opposition leader Étienne Tshisekedi to no longer recognize the authority of the president, which was posted on YouTube on December 19.[37]

In the aftermath of the demonstrations, authorities in Kinshasa denied relatives access to hospitals and morgues, making it impossible for many families to bury their loved ones. A morgue official told Human Rights Watch that they had received instructions from the health ministry not to disclose any information on the cases of people who had been killed.[38] He also said that the police officers assigned to guard the morgue were all replaced in early January 2017 to help prevent the disclosure of information.[39] Another morgue official said that police officers had taken three bodies of victims killed during the December protests from the morgue where he worked to an unknown destination during the night of January 21 to 22.[40]

Family members in Lubumbashi also had difficulties finding and burying their loved ones. A morgue official said that they had received instructions not to talk to any visitors who asked about people killed or wounded during the December protests. He also said that intelligence officers had taken the wounded out of the morgue and brought them to an undisclosed location.[41]

Authorities had used similar tactics in September 2016, preventing families from burying victims after security forces used excessive and unnecessary lethal force during earlier protests in Kinshasa, killing at least 66 people.[42]

In a report published on February 28, 2017, the UN Joint Human Rights Office in Congo said that security forces killed at least 40 people, wounded at least 147 others, and arrested over 917 people during protests across the country between December 15 and 31. The killings were the “result of a disproportionate use of force and the use of live ammunition by defense and security forces, particularly FARDC [Congolese army] soldiers, to prevent and contain public demonstrations,” the report said, adding that some cases seem to “demonstrate an intentional shoot-to-kill approach by FARDC soldiers.”[43] The report notes the use of “lethal force and live ammunition on upper parts of the body, by the Congolese defense and security forces,” and that “many victims were injured as a result of cruel, inhumane or degrading treatment during arrest and detention.”[44]

According to the Congolese police spokesperson, 22 people were killed during protests across the country between December 18 and 21, and 275 others were arrested.[45]

Accounts from Victims and Witnesses to December Repression

Kinshasa

In Kinshasa, Republican Guard and army soldiers and police[46] fired live rounds to disperse protesters in Matete, Ngaba, Kinseso, Kimbanseke, Masina, Limete, Lemba, Ndjili, Barumbu, Lingwala, Selembao, Mont-Ngafula and Ngiri-Ngiri neighborhoods—killing at least 36 people, and wounding around 50 others between December 19 and 21. On December 20, Republican Guard soldiers conducted door-to-door searches in Matete and Lemba neighborhoods, arresting scores of suspected protesters.

A witness described how Republican Guard soldiers fired on demonstrators in Kisenso neighborhood on December 20, soon after UN peacekeepers drove by:

When two MONUSCO vehicles with peacekeepers drove down the avenue, people started clapping and chanting slogans about Kabila’s mandate being up. Just after they passed, Republican Guard soldiers stormed into the neighborhood and began firing live bullets to chase the demonstrators who fled into houses to take cover. I was looking out from the window of my home. All of a sudden, I saw my neighbor, who’d been standing outside his house, yell and fall over. I got really scared. Then the soldiers entered into the compound and picked up my neighbor’s body. He was bleeding terribly. We didn’t know where they took him. His family found his body three days later in one of the morgues, after having searched for him in prisons and hospitals across the city.[47]

A woman said that her son was shot dead by Republican Guard soldiers in Lemba neighborhood on December 20:

The Republican Guard soldiers had been deployed in our neighborhood since the day before [December 19]. Then that morning, as the protests were happening, they started harassing the population, stealing phones, watches, and other valuables from people in the neighborhood. When a man resisted as the soldiers tried to steal his phone, the soldiers started firing their guns. My son, who had gone out to buy bread, was hit by a bullet in the forehead, and he died on the spot. He hadn’t participated in the protests.[48]

A man said that his son was shot in Limete neighborhood on December 20:

My son was eating breakfast on the corner of the avenue. Then at about 10 a.m., the soldiers who came to chase the protesters out of our neighborhood fired in every direction. My son was hit by a bullet in his right leg. He later died of his wounds.[49]

In the early hours of December 20, a taxi driver stepped out of his house in Kinshasa’s Masina neighborhood to take a phone call. Soldiers deployed to crack down on protesters saw him talking on his phone and accused him of “calling rebels to plan an attack against Kinshasa.” They arrested him and brought him to a nearby camp. His family went to negotiate his release, but soldiers told them to return home and “cry over his death.” Shortly after, neighbors found his body in a hole next to the road, just hundreds of meters away from his home.[50]

The Kinshasa representative for the activist group Filimbi, Carbone Beni, was arrested on December 13 alongside other activists outside the building in Kinshasa where the Catholic Church-mediated talks were being held and brought to a military camp. Beni said:

I was brought to an underground cell known as “Zaire” [Congo’s former name] … When you enter [there], it’s like you’re no longer in Congo. You’re in the dark. They showed me [a tablet computer with Beni’s interviews in international media], and said, “So, you say: ‘Bye bye Kabila’ [name of a Filimbi campaign], but now it’s you who will leave, because Kabila will never leave.” … They gave orders to another officer to guard me, adding that I “should not see the sun.”[51]

Beni’s family had no news about him until his wife received a handwritten note from him on December 26, informing her that he was being held at the Tshatshi military camp. Beni was finally released on January 11, after 29 days of secret detention in Kinshasa, first at the military camp and later at an intelligence agency detention center.[52]

Members of the youth movement Struggle for Change (LUCHA), Gloria Sengha and Musasa Tshibanda, were arrested on December 16. Sengha later said that she had been thrown into a car, blindfolded and beaten. “They said, ‘Do you know where we’ll bring you? We will kill you, since you want to make Kabila leave [power]. We will kill you,’” she told Human Rights Watch. “I was scared. I told myself: ‘This is the end of me; this is my death.’”[53] Held in incommunicado detention first at Camp Tshatshi and then at the 3Z detention center of the intelligence services, she was interrogated about LUCHA and its supporters. She received little food and water until her release on December 27. Tshibanda was released on February 8, 2017.[54]

Franck Diongo, a member of parliament and president of the opposition party Movement of Progressive Lumumbists (MLP), was arrested on December 19 in Kinshasa. Security forces arrested him and his colleagues after they had apprehended three men who, according to Diongo, were Republican Guard soldiers wearing civilian clothes. Diongo said he feared they had been sent to attack him.[55] Congo’s Supreme Court of Justice sentenced Diongo to five years in prison on December 28, 2016, following a hasty trial that he attended in a wheelchair and on an intravenous drip, which his lawyers said was due to the treatment he endured during arrest and detention. According to Diongo and his lawyers, this amounted to torture. Diongo was convicted of “aggravated arbitrary arrest” and “illegal detention.” As a member of parliament, Diongo was tried by the Supreme Court; he has no possibility to appeal the judgement.[56]

A Congolese journalist said that he was abducted by people he believes were linked to the government after getting in a taxi in Kinshasa following the protests on December 20:

One of the people with me in the taxi pointed a gun at me, before putting a hood over my head. They then brought me to a house where they interrogated me about my origins. They eventually let me go and told me to stop writing articles that upset the authorities and to stop saying things that annoy them.[57]

Lubumbashi

In Lubumbashi, major violence broke out between December 20 and 22. Republican Guard and army soldiers fired on protesters, some of whom threw rocks at security forces and looted or set fire to police offices and cars, ambulances, trucks, and other buildings in Gecamines, Kisanga, and Katuba neighborhoods. In total, security forces fatally shot at least 16 protesters and wounded 40 others.

A local activist described what he saw on Lubumbashi’s Kasumbalesa road in the Kenya neighborhood on December 20:

Protesters had erected barricades along the road. The police tried to clear the road but the protesters didn’t want that, so they started throwing stones and other things. The police shot in the air to try to disperse them. When men in military uniforms with ski masks covering their faces arrived on the scene, that’s when the killing started. I myself saw six dead bodies while I was trying to flee.[58]

Another witness said that a protester was shot at point-blank range by soldiers on December 20:

While the protesters were chanting hostile slogans about the authorities and the end of Kabila’s mandate, soldiers came to disperse them with live bullets. A young man I knew was shot in his throat and died on the spot. This angered the crowd of protesters who then set the Katuba courthouse on fire.[59]

A witness said that a young mechanic was killed when security forces arrived to disperse looters at a public hospital on December 20:

The soldiers first fired in the air to disperse the looters at the hospital. As the looters fled into the surrounding neighborhood, the soldiers followed them. Hearing the gunshots nearby, the mechanic, who was with a client, decided to go home. While leaving his client’s home, he came across the soldiers who’d been chasing the looters. They grabbed him, and the man went down on his knees, begging them not to kill him and explaining that he had just left the house of his client and wasn’t among the looters. Despite this, they shot him in the head. The soldiers then took his body and brought it to one of the public morgues.[60]

A woman described how her brother-in-law was killed during the demonstrations on December 20:

Between 8:30 and 9 a.m., we found out that there were demonstrations on the road near our house. Just after that, we started hearing gunshots. People were fleeing in all directions. Some people ran towards us and said that [my brother-in-law] was shot. My husband got the courage to search for him, but in vain. We later learned that soldiers had taken his body to the morgue.[61]

Goma

In Goma, security forces arrested over 100 people between December 15 and 31, according to the UN.[62] This includes many of those who were planning the protests and mobilizing others to participate. This seems to have had an important deterrent effect in preventing large-scale protests from going forward on December 20.[63]

On December 17 in Goma, two men in uniform arrested two members of the Engagement for Citizenship and Development (ECiDé) opposition political party, Christian Badose and André Bisimwa. First detained at the military intelligence premises, they were transferred to the military prosecutor’s office, and then to the general prosecutor’s office. They were released on December 28, with no charges brought against them.[64]

On December 18, LUCHA activist Bienfait Katalanwa was abducted in Goma’s city center by four men in civilian clothes and released the following evening.[65]

On December 19, at least 41 people were arrested. Among those arrested were 12 representatives of the Rassemblement opposition party coalition – including the ECiDé, Social Movement for Renewal (MSR), National Party for Development and Democracy (PND), and UDPS political parties – who were leading a peaceful march down the street in the center of Goma. They were arrested in the presence of a team of UN human rights observers and transferred to the police intelligence prison. The human rights observers were later denied access to them.

Sephora Bidwaya, a young UDPS activist among those arrested on December 19 told Human Rights Watch about the “revolting conditions” at Goma’s Munzenze prison, where they were held:

They distribute food to us – just a large bowl of beans – once every other week. Most people here sleep on the floor. The situation is really appalling.… We should be released immediately because we haven’t committed any crimes.… We were only calling for the respect of the constitution, which is a legitimate thing![66]

Sephora and the 11 others were eventually released on September 9, 2017.

On December 21, police arrested 19 LUCHA activists as they tried to hold a peaceful sit-in outside the governor’s office. They were released on December 27. An international journalist observing the protest was detained for several hours.[67]

Boma

In Boma, in the southwestern Kongo Central province, on December 20, police and soldiers killed at least six people when they fired live rounds to disperse protesters chanting that Kabila’s “time was up” in the Kalamu, Nzandi, and Kabondo neighborhoods. Several witnesses said that they heard soldiers tell the protesters: “We are here to exterminate you all!”[68] One witness said he heard a soldier say, “The person whose mandate you say has ended is in Kinshasa; go make noise there. Here, we will exterminate you one by one.”[69]

Security forces also shot and wounded about a dozen people. Many of those targeted had not participated in the protests, but were hiding in homes, seeking shelter from the gunfire. Some of those targeted were taking advantage of the chaos to loot in Kalamu neighborhood.

One resident said that his wife was killed on December 20 when a soldier followed her to the house where she had taken shelter, to flee the soldiers who were firing on protesters in their neighborhood:

My wife was inside [the house], and the soldier arrived soon after. He first fired warning shots and demanded that the door be opened. The owner of the house refused to obey. The soldier then counted out loud to three, and then he fired two shots into the house. One of the bullets hit my wife in the head.[70]

Another man said that solders had shot and killed his 35-year-old son during protests in their neighborhood on the morning of December 20 as he was standing next to him:

My son was shot by a bullet in the head. As he fell down, I immediately bent down. A bullet then passed right above my head and hit the window. If I had remained standing, I too would have been killed. We were standing in front of our house, and we weren’t among the protesters or looters. This soldier aimed and fired at us with the intention of killing us. My son has now left [the world] just like that, for no reason at all.[71]

Matadi

In Matadi, the capital of Kongo Central province, security forces used excessive and unnecessary force to disperse protesters chanting that Kabila’s mandate had ended, killing at least four people on December 20. They also conducted door-to-door searches in Mvuzi and Nzanza neighborhoods, arresting several people. Some protesters engaged in looting.

A woman said that her grandson was killed during the protests on December 20:

My grandson went out about 9 a.m. to buy bread a few meters away from the house. When the police started firing live bullets to disperse the protesters who were chanting about the end of the president’s mandate, he was struck by a stray bullet that entered his forehead and exited through his neck. He was only 16-years-old, and he wasn’t at all a rowdy boy.[72]

Other Cities

Several dozen people, mostly youth, were arrested in the early hours of December 20 in the eastern town of Oicha for making noise with whistles and pots clamoring for Kabila to leave office. Local civil society activists reported that many were mistreated in detention. They were released the following day.[73]

On December 21, seven LUCHA activists and a bystander were arrested in Mbuji-Mayi, Kasai Oriental province, while they were discussing their upcoming activities. Six of them were released the next day while two others, Jean-Paul Mualaba Biaya and Nicolas Mbiya Kabeya, were eventually acquitted on February 1, 2017, and then released.

In the morning of December 22, at least 14 activists from LUCHA, Filimbi, and Réveil des Indignés were arrested during a sit-in in front of the provincial assembly in Bukavu. They were released the same day.[74]

Mobilization of Youth Gangs

Congolese authorities instructed members of youth leagues and street gangs in Kinshasa and Goma to infiltrate and provoke violence among protesters in order to give a pretext to security forces to disperse the demonstrations by force. Two members of a pro-government youth league in Kinshasa said that they received their instructions during a meeting in Kinshasa on December 18 with senior officials who promised them 120,000 Congolese francs (US$77) each.[75] The recruits said that some soldiers were mixed in among the members of youth leagues, and that they were divided into four groups. The person responsible for each group was given a revolver. Members of youth leagues in Kinshasa were given similar instructions to infiltrate protests in September 2015 and September 2016.[76]

In Goma, two young men said that they had been working closely with security forces for a long time, infiltrating youth movements to gather intelligence in return for alcohol and up to 5,000 Congolese Francs (US$3.20).[77]

Looting and Violence by Protesters

Some protesters engaged in violence, throwing stones at security forces or vehicles, while others burned tires in the streets and looted shops and public and private buildings.

In Kinshasa, protesters burned the headquarters of the ruling People’s Party for Reconstruction and Democracy (PPRD) on December 20 in Matete neighborhood. The same day, in Lubumbashi, protesters ransacked or burned several government buildings, including health and environment ministry offices, a courthouse, police stations, and a local administration office. Gas stations, the so-called “Joseph Kabila Stadium,” and private vehicles were also targeted.

In Boma, protesters in the Kalamu neighborhood looted or ransacked shops, including some owned by individuals linked to government officials, Chinese-owned shops (China is perceived as a close ally of Kabila), and government buildings in Kalamu neighborhood.

In Matadi, protesters also looted privately owned shops, while others clashed with security forces. At least 10 police officers were injured by stones that were thrown by protesters, and one soldier had a broken leg after being attacked by a machete, apparently to avenge the death of a protester who had been killed by the security forces.

III. Background on the M23

The Rwandan-backed M23 rebellion began in April 2012, under the leadership of Gen. Bosco Ntaganda, who is now on trial at the International Criminal Court in The Hague, where he faces 18 counts of war crimes and crimes against humanity charges.[78] In 2012 and 2013, M23 fighters committed widespread war crimes in eastern Congo, including summary executions, rapes, and forced recruitment of children.[79]

The M23 was made up largely of former members of the National Congress for the Defense of the People (Congrès national pour la défense du peuple, or CNDP), a previous Rwandan-backed Congolese rebel group, whose fighters were integrated into the Congolese army in 2009. The CNDP had purportedly been established to defend, protect, and ensure political representation for the several hundred thousand Congolese Tutsi living in eastern Congo, and several tens of thousands of Congolese refugees, most of them Tutsi, living in Rwanda. The group’s fighters were also responsible for widespread war crimes.[80] Many CNDP fighters had previously been part of another Congolese rebel group backed by Rwanda, the Rally for Congolese Democracy (Rassemblement congolais pour la démocratie, RCD), during the “second Congo war,” from 1998 to 2003.

Over the years, many former commanders and individuals close to the various Rwandan-backed rebellions have been given senior posts in the Congolese security forces and government.

The M23 relied on significant support from Rwandan military officials who planned and commanded operations, trained new recruits, and provided weapons, ammunition, and other supplies.[81] Hundreds of young men and boys were recruited in Rwanda and forced to fight with the M23 in Congo. The M23 also relied on support from senior Ugandan government officials, according to the UN Group of Experts.[82] The group controlled large swathes of Rutshuru and Nyiragongo territories in North Kivu.

International attention on the crisis grew when the M23 seized the main eastern city of Goma in late November 2012, again with significant Rwandan military support. The M23 withdrew from Goma on December 1, when the Congolese government agreed to peace talks.

On February 24, 2013, 11 African countries (later joined by two other countries) signed the Peace, Security and Cooperation Framework for the Democratic Republic of Congo and the Region in Addis-Ababa, under the auspices of UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon. The signatories – including Congo, Rwanda, and Uganda – agreed not to interfere in the internal affairs of neighboring countries; not to tolerate or provide support of any kind to armed groups; neither to harbor nor provide protection of any kind to anyone accused of war crimes, crimes against humanity, acts of genocide or crimes of aggression, or anyone falling under the UN sanctions regime; and to cooperate with regional justice initiatives.[83]

As Rwanda was under increased pressure to stop supporting the abusive armed group and its commander, Ntaganda (who was already sought on an arrest warrant from the ICC), the M23 split and the faction led by Ntaganda was defeated by the faction led by another M23 officer, Sultani Makenga, in March 2013. Apparently fearing for his life, Ntaganda turned himself in at the United States embassy in Kigali, and he was soon transferred to The Hague. Most of the fighters loyal to Ntaganda then took refuge in Rwanda.[84] Makenga’s group was eventually defeated by the Congolese army—with support from the UN peacekeeping mission in Congo, MONUSCO, and its Force Intervention Brigade (FIB)—in November 2013. Most of Makenga’s fighters then took refuge in neighboring Uganda.[85]

Following the group’s defeat, the Congolese government and M23 signed the so-called Nairobi Declarations in December 2013, concluding a dialogue that started in 2012 and was mediated by then Ugandan defense minister Dr. Crispus Kiyonga.[86] As per the individual declarations, the Congolese government committed to give an amnesty to combatants not otherwise sought for serious crimes and to: respect and implement transitional security arrangements that would include cantonment, disarmament, demobilization and social reintegration of M23 combatants; release political prisoners; support the return and resettlement of Congolese refugees and internally displaced people; carry out national reconciliation efforts; implement governance as well as socio-economic reforms; and establish a mechanism for evaluating and following up on the Nairobi declarations.

The M23, in turn, committed to renounce its rebellion; comply with and implement transitional security arrangements; produce a list of its imprisoned members; transform into a political party in accordance with Congo’s laws and constitution; encourage the return and resettlement of refugees and internally displaced persons; and participate in a national reconciliation commission and a mechanism for implementing, monitoring and evaluating the Nairobi declarations.

Progress on implementing the Nairobi Declarations and the earlier Framework Agreement over the past four years has been limited. The M23 may continue to pose a threat to civilians until M23 leaders responsible for serious international crimes are brought to justice and eligible M23 combatants are repatriated so that they can participate in a credible disarmament, demobilization and reintegration (DDR) program that provides them a viable alternative to rebellion. While the M23’s original leader, Ntaganda, has been on trial at the ICC for crimes committed in 2002 and 2003 in Ituri district when he was part of another rebellion, no other M23 leaders have been arrested or brought to justice for crimes committed during the M23 rebellion.

The Nairobi declarations were clear that M23 leaders allegedly responsible for war crimes and other grave international crimes would not benefit from an amnesty. More than a dozen M23 commanders are sought on Congolese and international arrest warrants for war crimes and crimes against humanity.[87] Seven of these individuals are on UN and US sanctions lists that subject them to a travel ban and assets freeze.[88] In July 2013, the Congolese government officially requested the extradition of four M23 leaders from Rwanda to Congo, namely Eric Badege, Baudouin Ngaruye, Jean-Marie Runiga, and Innocent Zimurinda. Human Rights Watch is not aware of any recent efforts to follow up on the extradition requests. Three of the four were involved in organizing the operations to quash protests in Congo in December 2016, which is a violation of the Nairobi declarations.[89]

In November 2013, the Ugandan government reported that a total of 1,456 M23 combatants were in Kisoro, Uganda,[90] although other estimates were significantly lower.[91] After disarming them and handing their weapons over to the Congolese government, Ugandan authorities reportedly relocated 1,312 M3 combatants to Hima in Kasese district. The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and the expanded joint verification mechanism (EJVM) of the International Conference of the Great Lakes Region (ICGLR) visited them there. Fifty children were reportedly handed over to the ICRC.[92]

Around 1,300 combatants were then reportedly transferred to the Bihanga military training camp in December 2013. The UN peacekeeping mission, EJVM, journalists and others visited M23 fighters there. In May 2014, a Congolese government delegation visited Bihanga to register combatants following the signing of the amnesty law three months prior.[93]

Later that year, in December 2014, a total of 182 former M23 elements were repatriated from Uganda to the Kamina military camp in Congo. The same month, the UN reported that about 1,000 ex-M23 elements had refused to be repatriated and fled the camp in Bihanga, reportedly moving to the Rwamwanja refugee camp, 26 kilometers from Bihanga.[94] Their refusal to return came in the context of reports that more than 100 other demobilized combatants and dependents had died from starvation and disease in a remote military camp in Congo after officials failed to provide adequate food and health care.[95] At time of writing, the situation of many other ex-combatants in camps around the country remains dire, with DDR programs stalled and many lacking the means to start a new life and tempted to join an armed group to make ends meet.[96]

In January 2015, M23 official René Abandi resigned from his position as coordinator tasked to oversee implementation of the Nairobi declarations, alleging that the Congolese government was violating its commitments.[97] Other M23 leaders also expressed concern and fear about the security in cantonment camps in Congo.[98] In October that year, the political leader of the M23 wing in Uganda, Bertand Bisimwa, declared that the M23 group residing in Uganda would no longer honor its commitment under the Nairobi declarations given the perceived obstruction and unwillingness of the Congolese government.[99]

In December 2015, only 646 M23 combatants were reportedly present in Bihanga camp in Uganda with nearly 500 others recorded as absent. Thirteen M23 were later repatriated to Kamina in Congo, bringing the number of total M23 combatants repatriated from Uganda to Congo to a total of 195 by the end of 2015, two years after the Nairobi declarations had been signed. By that time, 309 were still present and accounted for in Rwanda out of about 600 M23 who had fled to Rwanda in March 2013.[100]

In April 2016, Uganda hosted a meeting with regional stakeholders to discuss the delayed implementation of the Nairobi declarations. A month later, M23 representatives traveled to Kinshasa to attend a meeting between signatories to the declarations.[101]

While some M23 fighters were being recruited in late 2016 to protect Kabila in the country’s main cities, others crossed the border from Uganda and Rwanda to eastern Congo’s Rutshuru and Nyiragongo territories, ostensibly to create a new rebellion. Sporadic skirmishes with the Congolese army were reported in late 2016 and early 2017. The Congolese ambassador to the United Nations in New York wrote to the UN Security Council in January 2017, warning that the renewed “war” with the M23 could delay plans for the organization of elections. While some M23 fighters and commanders may genuinely oppose the Congolese government and support a renewed rebellion, several M23 combatants told Human Rights Watch that the government used some of the renewed fighting as a diversion and that some elements of the M23 continued to get support from and maintain good relations with some senior Congolese security force officers.[102]

On January 18, 2017, the Ugandan government reportedly arrested 101 M23 combatants who had escaped from Bihanga camp and said others had been “quietly escaping into the general public and some to unknown places.”[103] Another 40 M23 rebels were discovered to have escaped earlier on January 12.[104]

Also in January, the Rwandan government announced that a group of unarmed people claiming to be M23 combatants had fled from Congo to Rwanda.[105]

On February 9, 2017, an intelligence officer and captain at the Bihanga Army Training School said that they could not account for 750 M23 rebels.[106] A few days later, a Ugandan army spokesperson said that 44 ex-M23 combatants, who had fled to Uganda following clashes with the Congolese army, had been arrested and were being held in the military camp in Kisoro, Uganda.[107] In early September 2017, Uganda could account for 214 combatants physically present while another 887 remain unaccounted for.[108]

On October 18, a Congolese army spokesperson announced the repatriation of 51 M23 combatants from Uganda to Congo, and he added that over 300 M23 combatants had already been repatriated since the start of 2017. He said they were currently in training centers as part of the demobilization and reinsertion program for former combatants.[109]

Ugandan authorities have repeatedly expressed their dissatisfaction with the stalemate of hundreds of M23 members residing in their country. In 2014, for example, a Ugandan military spokesperson lamented that “we don’t have money [to feed them]. They are a burden for us.”[110] In an official correspondence to Human Rights Watch on September 5, 2017, the Ugandan Minister of Defense and Veteran Affairs Adolf Mwesige wrote, “currently, the Ex-M23 combatants in Uganda are neither prisoners, NOR refugees because they are NOT prisoners, some of them have moved out of the cantonment and scattered in other surroundings areas, including refugee camps and other country sides in search for employment to raise cash for basic essentials such as clothing and et al.” He also clarified that Uganda “still bears the burden of accommodation, feeding, clothing and general welfare of ex-M23 combatants. This is being done against a constrained budget. Bearing in mind that these members are neither in prison nor in a refugee camp, containing their movement has been difficult. Their repatriation therefore is overdue and should be expedited.”[111]

The failure to officially repatriate the majority of M23 combatants to Congo, grant them refugee status in Uganda or Rwanda (Uganda is in the process of granting refugee status, the government said in September 2017[112]), or possibly relocate them to another country appears to have played a role in convincing many M23 combatants to return to Congo and partake in the December 2016 repression.

IV. M23 Recruitment and Role in December 2016 Crackdown

Based on interviews with 21 M23 fighters, commanders and political leaders and nine Congolese security force officers, Human Rights Watch estimates that at least around 200 M23 fighters were recruited in Uganda and Rwanda by Congo’s government and deployed to Kinshasa, Lubumbashi, and Goma around December 19, 2016. The actual number is likely significantly higher.

While senior M23 officers were aware of the operation and helped facilitate the transfers, it was largely the rank-and-file combatants—who would not be recognized by the Congolese population or the security forces—who were sent to Congo. Numerous security officials in Congo, Rwanda, and Uganda, as well as at least 20 senior M23 officers, organized and helped facilitate the covert transfers across the three countries, involving long overland drives and flights. Congolese security service officials paid M23 combatants relatively large sums of money and fed and accommodated them during the deployment.

Motivations of M23 Combatants

M23 fighters told Human Rights Watch that they agreed to participate in the operation to protect Kabila because they were paid well, they were well taken care of before and during their deployment to Congo, and they were simply following the orders of their commanders. Some said that they had been promised senior ranks and prestigious positions in the Congolese army or a return to Congo after spending years abroad in difficult circumstances. Eight of the M23 combatants interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that their superiors had told them that only Kabila would protect and promote their interests in Congo, so they had to do what they could to make sure he stayed in power. They were told that the presidency, in turn, did not trust its regular army and favored the M23 for their loyalty and ruthlessness in executing orders.[113]

One high-ranking M23 officer in Uganda told Human Rights Watch:

We continue to be supported here by people inside the Congolese government. We regularly receive money from Kinshasa, like other units of the FARDC [Congolese army]. The M23 is essentially working for Kabila [now].

The only way for Kabila to stay in power is if he remains strong, but you aren’t strong if you don’t entirely control your army and that’s where the M23 comes in. We have the best soldiers loyal to President Kabila other than those who integrated into the army after they were with [the previous rebel groups] RCD and CNDP.

We were warned that “the power in Congo will tumble if we don’t mobilize behind Kabila, who has helped us for a long time. If he’s no longer there, nobody would speak about us [Congolese Tutsi] in Congo anymore. We need to mobilize or it will also be the end of us.”[114]

Another M23 officer in Uganda said:

A Congolese general told us the president was in danger and therefore all of Kabila’s friends are also in danger. The general explained to us in clear and simple terms why we must help Kabila, saying that Congolese from the west [of the country] don’t appreciate those of us who come from the east. If Kabila leaves office, it’s the end for the people from the east. They will be chased out of Kinshasa like dogs or sorcerers. This is why we must all rally to protect the president.[115]

An M23 combatant in Uganda said Kabila’s lack of trust in his own army was a reason for him to turn to the M23 for help:

M23 combatants went to Kinshasa because the president has lost confidence in his own military. He only trusts soldiers from the east: North and South Kivu [provinces]; many of them once worked with the RCD and CNDP. A lot of M23 were deployed to wage a war against those who want to put Kabila’s power in danger.[116]

Another combatant said that “Kabila called us in, the M23,” adding: “We’ve supported him. We also know that he supports us in a variety of ways. It’s thanks to him that we live here, in Uganda. It’s thanks to him that many members from our [Tutsi] community found senior positions in the army, the police, and even in the public administration.”[117]

An M23 fighter in Rwanda said that former CNDP and RCD officers in the Congolese army had told M23 officers that “the new ranks” for M23 fighters will be announced “soon,” that the high ranks “will be accompanied by better positions, and that the M23 will control the entire army in North Kivu and South Kivu provinces. But while waiting for this to happen, the M23 must also support the president in his final battles, and this fight is to ensure he can stay in power beyond December 19, 2016.”[118]

A lieutenant colonel in the Congolese army elaborated on the motivation behind recruiting M23 into the ranks of the Congolese forces:

You know the presence of soldiers has always frightened civilians. That’s why President Kabila decided to deploy M23 on the streets of the major cities [in Congo] so that all those civilians who wanted to protest would be too afraid to leave their homes.[119]

Recruitment in Uganda

Throughout 2016, but especially toward the end of the year, senior Congolese security officials went to Uganda, including the refugee camps in Rwamwanja and Kyaka, as well as the military camp Bihanga, to meet with senior M23 officials and inform them about the operation to send M23 fighters to Congo at the end of the year. They also gave M23 officers significant amounts of money to finance the operation. Some M23 officers and fighters also received phone calls from their contacts in the Congolese security forces, encouraging them to support and participate in the operation.

An M23 officer told Human Rights Watch about a Congolese army general’s regular visits to Uganda in 2016: “All of his trips were meant to prepare the people who could protect the president at the end of his mandate.”[120]

Around November 21, 2016, senior M23 officers invited dozens of M23 fighters based in Rwamwanja camp in Uganda to a meeting at a hotel in Katalieba, not far from the camp. During the meeting, the officers told them about the operation and explained why they needed to go to Congo to protect Kabila. The M23 fighters ate and drank well, and each of them left the meeting with an envelope containing US$300 to $500—a lot of money for M23 fighters who had not had any official employment for years.

Human Rights Watch interviewed several of the M23 fighters who had participated in the meeting. One of them said, “There was a lot of food and drinks at the meeting. I was surprised by the reception and how many of us were there. Each of us could drink whatever and how much he liked.”[121]

Another combatant said that he decided to attend the meeting at the hotel because he “had had heard that … money was already circulating in Rwamwanja for those who would accept to go to Congo to protect President Joseph Kabila.” When he got to the meeting, he said he was “surprised to see such a large number of people available to go on a mission to Congo. After the meeting, I received an envelope containing $500. I was really happy. There was also a lot of food for us.”[122]

Another M23 fighter said he was recruited by M23 Col. Yusuf Mboneza, who was in charge of military operations for the M23.[123] He said that Mboneza told him that a Congolese army officer had brought money to Rwamwanja to finance the transfer of M23 fighters to Congo. “It wasn’t difficult, because there was money to give around,” he said. “Personally, I received $300.”[124] Another M23 combatant told Human Rights Watch he participated with several M23 leaders, including Colonel Mboneza and a high-ranking Congolese army official, in a meeting to plan the recruitment of M23 combatants.[125]

A shopkeeper told Human Rights Watch about the “climate of mobilization” in Rwamwanja in November and December:

We thought they were getting ready for a new liberation war in Congo. In November and December, a lot of money circulated in the camp. The young men [M23 fighters] had a lot of money. One of them would come with a 100 dollar bill to buy a beer. This was really unusual. I don’t know when exactly they left, but by the beginning of December, the camp was nearly empty of young men. Some of them returned in late December; others came back in January. When they returned, we thought they must have had a great opportunity because they came back with money. Some later returned again to Congo [in 2017].[126]

Recruitment in Rwanda

In Rwanda, M23 fighters have been dispersed across several refugee camps, including Kiziba camp in Kibuye district, Western province, and Kigeme camp in Nyamagabe district, Southern province. In October 2016, senior M23 officials met with Congolese army officers in Gisenyi and Goma (neighboring cities in Rwanda and Congo, respectively). They were given large sums of money and instructions to start mobilizing the troops and prepare them for the operation in Congo in December.

“They got an important sum of money,” one M23 fighter told Human Rights Watch, referring to what the Congolese army officers paid the M23 commanders. “I don’t know the exact amount, but I can tell you that a lot of them started new construction projects in Goma since they got these payments.”[127]

M23 officials and senior officers then did a tour of the military and refugee camps to start mobilizing the M23 fighters. During this period, while awaiting the deployment to Congo, one M23 fighter in Rwanda described how the M23 commanders treated them:

[They] took really good care of us then. They gave us food and rations and even bought [alcoholic] drinks for us. We wondered where this generosity came from, and we realized later that it was part of their strategy to keep us close to them so we would be ready to deploy anytime. And we realized they had received money to take care of us during this period.[128]

Another M23 fighter described how they used word of mouth to spread the message: He said his commander came to mobilize them and “told us to go to the others, our colleagues and friends. That’s how the information spread to all the M23 fighters.”[129]

Journey to Congo

The M23 fighters travelled from the refugee and military camps in Uganda and Rwanda to their deployment in Kinshasa, Lubumbashi, and Goma in numerous different groups that varied in size, from a handful of M23 fighters to several dozen.[130] Some of the M23 fighters in Rwanda travelled to Congo on their own. They took different routes and travelled on different days to avoid drawing attention to their movements. Along the way, Ugandan, Rwandan, and Congolese officials, including army officers and border agents, facilitated their journeys, providing vehicles, flights, army uniforms, accommodation, food, and free passage.