Summary

In a village in the southern region of Sédhiou, 23-year old Fanta told Human Rights Watch about a secret “relationship” she had with her 30-year-old teacher, which began when she was 16. “I felt the shame in class … my classmates knew I was going out with him,” Fanta told Human Rights Watch. And so did other teachers, “but they said nothing.”

Fanta realized she was pregnant when she was 17. When her father tried to come to an arrangement with the teacher – a usual step taken by families who want to settle issues discretely to avoid facing their village’s scorn—he denied being the father of the child Fanta was expecting. “I told him ‘you have ruined my girls’ education,’ but he denied everything,” Fanta’s father, Cheikh, told Human Rights Watch. Even after it became evident that Fanta was pregnant, the school never investigated the matter, and the principal did not reach out to her, Fanta felt even more ashamed by the teacher’s denial: “I felt humiliated in front of my classmates.”

In Senegal, girls like Fanta face high levels of sexual and gender-based violence, including sexual exploitation, harassment and abuse, by teachers and other school officials. Unfortunately, these girls have few options for justice. Such cases are not often reported or investigated by school authorities. In some cases, families prefer to negotiate with men who make girls pregnant, including reaching agreement with the men to provide financial support for the girls during pregnancy, rather than to seek redress through official channels. But in many other cases, these girls would not inform their families because the taboos and stigma associated with such pregnancies are so damaging.

The scale and prevalence of sexual abuse against students is unknown, however, research by United Nations agencies, nongovernmental organizations, and academics indicates that school-related sexual and gender-based violence is a serious problem in the country’s education system.

Based on research conducted in 2017 in Senegal’s southern-most regions of Kolda, Sédhiou and Ziguinchor, as well as in and around the capital, Dakar, this report exposes the oft-underreported practice of school-related sexual exploitation, harassment and abuse primarily perpetrated by teachers and school officials and urges the government of Senegal to adopt key measures to stop these unlawful practices –which sometimes also constitute criminal offenses—in its schools.

This report, using the World Health’s Organization definition of sexual exploitation as any “actual or attempted abuse of position of vulnerability, differential power or trust, for sexual purposes,” documents how adolescent girls are exposed to sexual exploitation, harassment, and abuse by teachers and school officials in public middle and upper secondary schools.

Human Rights Watch interviewed 42 girls and young women ranging in age from 12 to 25 years, and held group discussions with a total of 122 secondary school girls, most of whom attended 14 public middle (écoles moyen) and 8 upper-secondary (lycées) schools across different regions of the country.

Human Rights Watch found that some teachers abuse their position of authority by sexually harassing girls and engaging in sexual relations with them, many of whom are under 18. The teachers often lure them with the promise of money, good grades, food, or items such as mobile phones and new clothes. Female students—and to a certain extent, teachers and school officials—often characterized it as “relationships” between teachers and students. Human Rights Watch believes that this type of characterization undermines the gravity of the abuse, affects reporting, and blurs the perpetrators’ perception of the severity of these abuses. Many of the cases documented in this report should be treated, and prosecuted, as sexual exploitation and abuse of children.

Sexual exploitation and harassment by teachers takes place in a variety of ways: some teachers would approach their students –during classes, or school evening activities — demanding a favor or requesting their phone numbers. When girls turned down teachers’ proposals, they believed the teachers punished them for rejecting their advances by awarding them lower grades than they deserved, ignoring and not letting them participate in class discussions or exercises. Often, the exploitation and harassment span months or in one case, years.

Girls are also affected by the gender stereotypes and sexual overtones they experience in class. Some girls told Human Rights Watch their teachers use inappropriate language or gestures –for example, describing girls’ bodies or clothes in a sexual manner—when talking to students directly or referring to other students in their class. Some girls feel wary when they know a teacher is making advances on a friend or classmate. When these types of harassment or abuse take place, teachers, parents, or even classmates, often blame the girls for attracting unnecessary attention from teaches, or provoking teachers with their outfits.

Senegal lacks a binding national code of conduct that outlines the obligations of teachers, school officials and education actors vis-à-vis students. However, teachers in Senegal, like their peers in many other countries, swear to adhere to a non-binding ethical and professional oath when they begin their teaching careers, pledging never to use their authority over students for sexual purposes.

Teachers’ behaviors outlined in this report are not only a gross violation of these professional and ethical obligations, but also a crime under Senegalese law when the girls are below age 16. Harassment and coercion of students for sexual purposes and the abuse of their power and authority over a child by teachers carries the maximum sentence of 10 years.

There have been reports in the Senegalese media of rape by teachers in schools across the country, raising serious concerns about what many girls may be going through. Since 2013, media reports show that at least 24 primary and secondary school teachers have been prosecuted for rape or acts of pedophilia – both constitute sexual offenses under Senegalese law. Although it is important that these prosecutions have taken place, our findings suggest that prosecution, professional sanction by superiors, or redress for other forms of sexual violence, particularly sexual exploitation, has been limited.

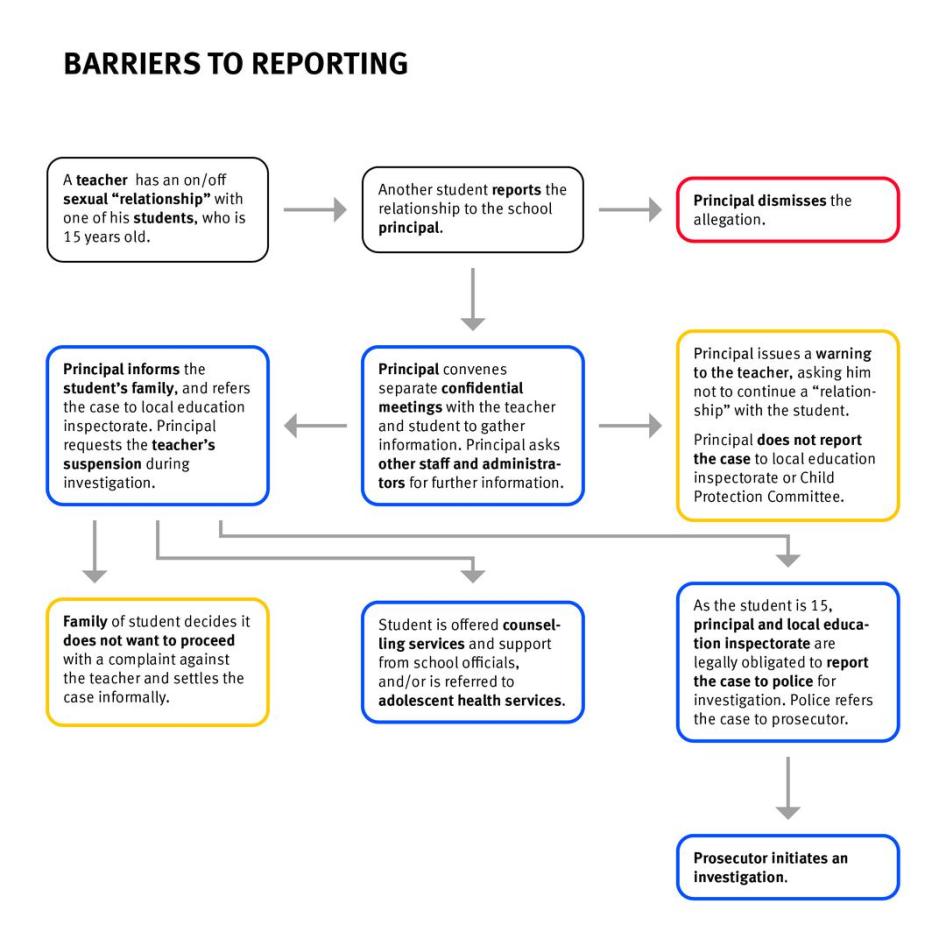

But many cases of sexual exploitation and harassment by teachers have gone unreported, and school authorities have not held perpetrators accountable. This is partly because reporting cases of sexual abuse or violence in schools overwhelmingly relies on a principal’s decision to act on or ignore a complaint, and because families are reluctant to report cases to the police. Although some principals take allegations seriously, they try to conduct informal investigations, talk to staff discretely, and address problems internally, to protect their staff, retain teachers, or prevent scrutiny from education inspectorates or child protection committees.

In addition, talking about sexual exploitation, harassment, and abuse is considered a taboo topic for many girls. Moreover, many students do not fully understand what sexual offenses are. Education about the full spectrum of offenses, or how to prevent and report sexual exploitation, harassment or abuse is scarce, and certainly not part of a national effort.

Even when girls who are sexually exploited, harassed or abused want to come forward, they are reluctant to report cases within schools for fear of being stigmatized or shamed. When they do come forward, senior school officials do not always take their word for it, and in some cases, are told that they have provoked their teachers. This has led to mistrust among students, and a feeling that reporting abuses will amount to nothing. As a result, girls affected by sexual exploitation, harassment, or other forms of abuse, rarely see their cases investigated, or see their perpetrators brought to account through the judiciary and the Ministry of National Education.

To its credit, the government has taken steps to tackle sexual violence and gender-based discrimination in schools as part of broader efforts to increase girls’ access to, and retention in, secondary education. In 2013, it adopted a robust child protection strategy, which launched child protection committees at all administrative levels. With international support, the government has also targeted some resources, seeking to end teenage pregnancies, and to empower girls. Many of these programs have not yet been taken to scale, remain contingent on donor’s financial support and have failed to address widespread sexual exploitation in schools.

Many school teachers, according to Human Rights Watch research, are genuinely working to ensure that students study in a safe learning environment, so that they can successfully complete their education. Many focus on tackling school-related sexual abuse. For example, some school principals have, on their own initiative, adopted zero tolerance policies for school-related abuses, and have openly talked about unlawful and unacceptable behaviors, to make girls feel comfortable with reporting any abuse or harmful behavior. Also, some committed teachers have dealt with these issues through child rights and child protection trainings, and organized awareness raising events at school to break down the taboos associated with these abuses.

Existing efforts to ensure retention of girls in secondary schools have often complemented school-based initiatives to curb teenage pregnancy rates. These have tended to focus on opening extra-curricular spaces for students to discuss family planning, and how to avoid HIV and sexually transmitted infections.

But the government needs to do a lot more to ensure students have access to adequate comprehensive sexual and reproductive health education. The government has been needlessly slow to adopt a national comprehensive sexual and reproductive health curriculum. At time of writing, it was reluctant to include content on sexuality in the curriculum due to concerns that teaching sexuality contradicts Senegal’s cultural and moral values, as well as pressure from religious groups.

Most public secondary schools in the regions where Human Rights Watch conducted research do not provide adequate, comprehensive and scientifically-accurate content on sexuality or reproduction. In most schools, abstinence remains the leading message. Some of the teachers who lead extra-curricular spaces provide students with some information about contraception, on the basis that this information will only be applied once students get married. Also, there are limited opportunities for young people to obtain useful information within the community. Although the government has made efforts to increase coverage of adolescent health services –including by setting up centers specializing in adolescents’ needs in most regional capitals—it has not guaranteed adequate coverage in rural areas.

Human Rights Watch calls on the government of Senegal to adopt a stronger national response to end sexual exploitation, harassment, and abuse in schools. Among its top priorities, the government should adopt a nation-wide policy to tackle sexual exploitation, harassment, and abuse in schools. This policy should clarify what constitutes unlawful or inappropriate behavior, and make clear that any and all sexual “relationships” between teaching staff and students, and exploitation and coercion for grades, money or basic items, such as food or mobile phones, are explicitly prohibited and subject to professional sanction. It should clarify that such “relationships” deemed to be constituting sexual offenses will be thoroughly investigated and perpetrators punished.

The government should also focus on increasing accountability for school-related sexual offenses. It should ensure principals and senior school staff understand their obligation to properly investigate any allegation of sexual exploitation, harassment, or abuse. It should introduce adequate trainings on child protection for all teachers, through pre and in-service training.

The government should strive to end the culture of silence around school-related sexual exploitation, harassment, and abuse, including by making reporting processes clearer, confidential and student-friendly, and roll-out a public education campaign directed at students and young people. This campaign should tackle the stereotypes, taboos and stigma that make girls and young women feel that they are guilty for sexual abuses committed against them. The campaign should also seek to equip students with the knowledge to understand what sexual exploitation, harassment and abuse is, and the confidence to speak out whenever it happens.

Key Recommendations

To the Government of Senegal

Adopt Stronger Measures to End School-Related Sexual and Gender-Based Violence and Abuse

- Adopt a national education policy against sexual exploitation, harassment and abuse, that includes: guidance on what constitutes or could lead up to these abuses, procedures to be adopted when cases are reported to school staff, clear school-based enforcement mechanisms and sanctions, and referrals to police.

- Adopt a nationwide binding professional code of conduct for principals, teachers and education officials that is displayed in all schools.

- Ensure that legislation relating to school-related sexual exploitation, harassment and abuse, are rigorously enforced, and that perpetrators of these crimes are brought to justice and punished with sanctions that are commensurate to their crimes.

Investigate All Allegations of School-Related Sexual Exploitation, Harassment, and Abuse

- Adequately respond to cases of sexual exploitation, harassment and abuse against students in educational institutions by ensuring that:

- All schools have functioning confidential and independent reporting mechanisms appropriate to the local school context. These could involve a trained counsellor or designated teacher at a minimum, or a reporting mechanism or telephone hotline system set up to refer complaints directly to a designated member of the relevant child protection committee.

- Students affected are promptly referred to external services for health, psychological support and contraceptive needs.

- Senior school officials conduct investigations following any allegations of misconduct, and where a law is violated, refer alleged perpetrators to the police.

- Perpetrators of sexual exploitation, harassment, and abuse are suspended from any position of authority affecting the complainant or the investigation during investigations, and if there is sufficient evidence, prosecuted, in line with international fair trial standards, or dealt with through the government’s disciplinary process for civil servants.

Urgently Tackle Barriers that Impede Girls’ Education

- Ensure secondary education is fully free by removing tuition fees and indirect costs charged by schools.

Provide Adequate Training for Education Staff and Teacher Placement

- Implement mandatory pre-service teacher training on existing laws on sexual offenses, and the new national school policy against sexual exploitation, harassment, and abuse, child rights, and the national child protection strategy. All new teachers, school leadership and administrative staff should be trained before their first placement.

- Adopt and roll-out a focused in-service training on sexual and gender-based violence in schools, starting with heads of school, senior school staff and teachers, and school inspectors.

Adopt a Strong Curriculum on Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights

- Ensure the curriculum on reproductive health education complies with international standards, and ensure that the national curriculum:

- Expands to include comprehensive information on sexuality and reproductive health, including information on sexual and reproductive health and rights, responsible sexual behavior, prevention of early pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections; and is mandatory, age-appropriate, and scientifically accurate.

Amend and/or Adopt Laws to Strengthen Protection for Children Affected by Abuses

- Amend the Penal Code to include:

- A provision that specifies the minimum age of consent to sexual activity, equal for all children, in accordance with international human rights norms and best practice.

- A specific criminal offense for an adult who has sexual relations with children under the minimum age of consent.

Methodology

This report is based on research conducted in June, August, October and November 2017, and July 2018, in the regions of Kolda, Sédhiou and Ziguinchor, as well as in and around the capital, Dakar. Human Rights Watch chose these regions because they have some of the highest rates of teenage pregnancy in the country, as well as high levels of child marriage and low secondary school retention, according to United Nations and government figures. We also consulted local and national nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), many of whom shared information or evidence from their existing programming assisting children affected by sexual and gender-based violence in these regions.

Human Rights Watch conducted 42 individual interviews with 27 girls and 15 young women. Their ages ranged from 12 to 25 years. Thirty-three attended school at the time of the interview while the other nine were no longer in school. We conducted the bulk of the interviews at 14 public middle schools (collèges d’enseignement moyen) and 8 upper-secondary (lycées) schools across different regions. Three of the girls said they were married, and nine girls and young women were pregnant or already had children. Although Human Rights Watch also interviewed girls who attended Franco-Arab, faith-based, and private secular schools, the findings included in this report focus on the situation in secular government secondary schools.

We also conducted focus group discussions with a total of 122 secondary school students in 4 public schools and in 4 villages, ranging from 7 to 22 participants in each of the groups. We organized group discussions to understand the key barriers affecting girls’ education, and ways in which school-related sexual exploitation, harassment and abuse affect female students in their daily lives. All participants were informed that they could speak individually to researchers following group discussions.

Interviews were conducted in French, or in Wolof, Pular, Jola, or Mandinka, and translated into French by adolescent health volunteers and representatives of nongovernmental organizations who accompanied Human Rights Watch researchers.

Human Rights Watch makes every effort to abide by best practice standards for ethical research and documentation of sexual violence. We preceded and ended all interviews with a detailed explanation of informed consent to ensure that interviewees understood the nature and purpose of the interview and could choose whether to speak with researchers. In each case, we explained how we would use and disseminate the information, and sought the interviewees’ permission to include their experiences and recommendations in this report. Human Rights Watch informed girls and young women that they could stop or pause the interview at any time and could decline to answer questions or discuss particular topics.

Some girls and young women preferred not to discuss personal experiences of school-related sexual exploitation, harassment, and abuse, but spoke about friends or classmates affected by these experiences. Six girls and young women said they themselves suffered sexual exploitation, harassment or abuse in the context of school. A further 10 girls and young women provided information on cases of sexual exploitation, harassment and abuse of friends or relatives. Most girls and young women interviewed knew of fellow classmates who had experienced school-related sexual exploitation or harassment.

In addition, the report includes information based on 11 interviews with teachers and activists, as well as mental health, adolescent health and child protection experts who supported girls and young women who had endured sexual exploitation, harassment, or abuse in the context of school. Finally, researchers interviewed four relatives or legal guardians of girls or young women who had experienced sexual exploitation, harassment and abuse.

Human Rights Watch makes no claims about the scale of school-related sexual exploitation, harassment or abuse by teachers in secondary schools across all of Senegal. Based on our research and findings, we note that issues raised in this report are underreported and the scale of school-related sexual exploitation, harassment and abuse of female and male students is unknown. Reporting on sexual abuse against girls and young women is greatly affected by deeply entrenched taboos and stigma associated with both talking about, and coming forward to report, any form of sexual abuse committed against girls. The issue is also compounded by the lack of confidential reporting mechanisms.

However, evidence suggests that many girls and young women are affected by school-related sexual exploitation, harassment and abuse. Our findings on these particular abuses are consistent with evidence gathered by the government, UN agencies and national and international organizations, which shows that these abuses occur in the regions where we conducted research, as well as in other parts of the country.

For protection reasons, names of children and young women used in the report are pseudonyms. Focus group discussions are referenced by location, and not by school, to further protect those interviewed. Some teachers and senior school officials are referred to anonymously to protect their identity where information provided could result in retaliation by perpetrators, other school officials or local government authorities. Also, for protection reasons we do not specify exact locations of children or alleged perpetrators.

Human Rights Watch also interviewed local and national government officials at the Ministry of National Education; the Ministry of Health and Social Action; and the Ministry of Youth, Employment and Citizen Building, as well as 4 village chiefs, 15 school staff, including principals, school supervisors (“surveillants”) and teachers, and over 40 NGO representatives, including those focused on education, child rights, sexual and reproductive health, and youth empowerment. We also interviewed mental health experts and practitioners, and development partners.

Human Rights Watch did not provide interviewees with financial compensation in exchange for an interview.

We reviewed Senegalese national law, government policies and reports, donor progress reports, government submissions to United Nations bodies, UN reports, NGO reports, academic articles, newspaper articles, and social media discussions, among others. The report’s recommendations were informed by global evidence-based guidance from the Global Working Group to End School-Related Gender-Based Violence.

The exchange rate at the time of the research was approximately US$1 = 530 Central African Francs (FCFA); this rate has been used for conversions in the text, which have sometimes been rounded to the nearest dollar.

TerminologyIn this report, the term “child” refers to anyone under the age of 18, consistent with usage in international law. The term “adolescent” is used to describe children and young adults from ages 10 to 19.[1] Lower secondary education refers to the first four years of compulsory secondary education in “middle” schools, referred to in the report as 6eme, 5eme, 4eme and 3eme. Upper secondary education refers to the final two years of secondary education in “high schools” or “lycée,” which are not compulsory in Senegal. According to the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, “gender-based violence is considered to be any harmful act directed against individuals or groups of individuals on the basis of their gender. It may include sexual violence, domestic violence … forced/early marriage and harmful traditional practices.”[2] Human Rights Watch uses the World Health Organization’s (WHO) definition of sexual violence as “[a]ny sexual act, attempt to obtain a sexual act, unwanted sexual comments or advances, or acts to traffic or otherwise directed against a person’s sexuality using coercion, by any person regardless of their relationship to the victim, in any setting.”[3] WHO defines sexual exploitation as “any actual or attempted abuse of a position of vulnerability, differential power, or trust, for sexual purposes, including, but not limited to, threatening or profiting monetarily, socially or politically from the sexual exploitation of another.”[4] |

I. Background

Sexual and gender-based violence against girls and women remains a widespread and pervasive problem in Senegal.[5] From a young age, girls face multiple sociocultural barriers and harmful practices that impact on many of their rights, including their right to education.[6]

The United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child has expressed concern over Senegal’s low enrolment rates of children, especially girls, in all levels of education, owing to early marriage, parents’ preference for educating boys, and teenage pregnancy.[7]

The government, together with international development partners, has acknowledged and taken some important steps to tackle the country’s high level of violence against women and girls and the barriers to education. It has launched multiple national awareness campaigns, women’s empowerment and girls’ education initiatives, and various policy initiatives.[8]

In 1995, Senegal kicked-off its efforts in girls’ education through the Girls’ Schooling (Scolarisation des Filles or SCOFI) project with the aim of mainstreaming gender-specific policies within the Ministry of National Education, focusing on girls’ needs in schools, and reviewing harmful stereotypes embedded in curriculum and teaching, among others.[9] With the support of donors, including the UN, the government also established a national committee of teachers to promote girls’ education (CNEP-SCOFI). Teachers have been instrumental in its roll-out, although this has largely happened through teachers’ own initiatives to organize campaigns locally, and find money from private sources to distribute school materials, uniforms, and items needed for the poorest families.[10]

Many other time-bound initiatives have followed since then, leading the government to set up a coordinating mechanism on girls’ education.[11] Multiple donor countries, including the United States, Italy and the United Kingdom, as well as multilateral donors like the World Bank, have supported the government’s efforts by funding small-scale, gender-specific programs aimed primarily at improving the quality of education, and increasing girls’ enrollment and retention. [12]

As a UN member state, the government has also endorsed major global sustainable development commitments to ensure free quality primary and secondary education to all children, eliminate gender disparities in education, end child marriage, and ensure universal access to sexual and reproductive health care services.[13] In 2016, Senegal also launched the African Union’s campaign to end child marriage.[14] As part of this campaign, the government committed to raise the age of marriage for girls to 18.[15]

But while these government efforts have helped increase girls’ access to education, they have failed to protect girls in and out of school from a wide range of human rights abuses.

Key Issues Holding Girls’ Education Back

Poverty, child marriage, teenage pregnancies, sexual exploitation and harassment by teachers and students, and violence in school are among the main factors that prevent girls from completing their secondary education.

Low Secondary School Enrollment and Lack of Inclusion

In Senegal, primary and lower-secondary education is, in theory, free and compulsory for all girls and boys age 6 to 16.[16] In practice, secondary school students may be required to pay close to 40,000 FCFA (US$75) in tuition fees, furniture costs and extra tuition for afternoon classes.[17]

However, in 2013, the last year for which official statistics were publicly available at time of writing, approximately 1.5 million children aged 7 – 16, representing 47 percent of children of primary and lower-secondary school going age, were not in formal education.[18] Government statistics show that there is near gender parity in secondary school enrollment, albeit stemming from a very low net enrolment rate: only 32 percent of girls and 35 percent of boys were enrolled in secondary school between 2008 and 2012.[19]

In rural areas –which generally have higher out of school rates—the government has focused on reducing the distance from homes to school by building more “community” middle schools. This has led to a significant reduction in the time children spend walking or getting to school, and in some cases, helped parents feel more comfortable with sending girls to school.[20]

While government statistics do not provide an accurate picture of how many children with disabilities live in the country, they do show that the majority of children with disabilities are out of school in Senegal. The government estimates that close to 17,000 girls and 19,000 boys with mild to severe disabilities, age 7 – 16, are out of school.[21]

Child Marriage, Unwanted Pregnancies and Lack of Contraceptives

In Senegal, as girls reach puberty and adolescence, they are often already married. Nearly one in three girls is married before turning 18.[22] In 2010, more than nine percent of girls were married by age 15.[23]

Girls have little access to sexual and reproductive health services, including contraceptives, and teenage pregnancy frequently ends a girl’s schooling. One in ten girls and one in twenty boys age 15-24 had their first sexual encounter before they were 15 years old.[24]

Teenage pregnancy rates remain very high across the country, with higher concentrations in the southern regions of Senegal, as well as Dakar.[25] Eight percent of girls aged 15 to 19 have already given birth.[26] Use of modern contraception remains weak: only 20 percent of adolescents who have sexual relations report using these methods. According to the Guttmacher Institute, a research and policy sexual and reproductive health and rights organization, only 25 percent of sexually active unmarried Senegalese women were using a modern method of contraception.[27] Although abortion is illegal, except in very restrictive conditions to save a pregnant woman’s life, an estimated 24 percent of unintended pregnancies, including among girls, end in induced abortions. In most cases, clandestine abortions are conducted by untrained providers.[28]

According to a study conducted by the UN Population Fund (UNFPA) and the Groupe pour L’Etude et l’Enseignement de la Population (GEEP), a national education research organization, at least 1971 cases of pregnancies were registered in schools from 2011 to 2014.[29] Comprehensive, accurate statistics on teenage pregnancies in schools are not available, due in part to the lack of an information system to record cases.[30]

In 2007, the government adopted a “re-entry” policy for young mothers, overturning its previous position to expel pregnant girls from school. The policy stipulates that girls will be suspended from school until delivery and can go back upon presentation of a medical certificate stating they are physically able to resume their studies.[31] Despite this positive accommodation, many girls do not return to school as they lack financial and family support. According to the joint UNFPA-GEEP study, more than 54 percent of young mothers dropped out of school between 2011 and 2014. Fifteen percent of young mothers resumed their education in that same period.[32]

School-Related Sexual and Gender Based Violence

Although the scale of sexual abuse against students is unknown, evidence collected by nongovernmental organizations, UN agencies and academics suggests that school-related sexual and gender-based violence –which includes rape, sexual exploitation and harassment—is a serious problem in the education system. [33]

In 2012, the government recognized the prevalence of school-related sexual and gender-based violence, and that girls are the main victims of sexual violence in school.[34] A government study on violence against children in schools primarily conducted in four regions—including Kolda and Ziguinchor where Human Rights Watch conducted research—showed that sexual exploitation, harassment and rape were prevalent: 37 percent of 731 girls declared being affected by school-related sexual harassment, 13 percent were affected by pedophilia, which includes any gesture, touching, or caressing for sexual purposes on children under 16.[35] Nearly 14 percent of those surveyed reported rape. The study revealed that in 42 percent of cases reported, teachers were the first perpetrators of these crimes.[36]

According to the joint UNFPA-GEEP study cited previously most school-related teenage pregnancies recorded between 2011 – 2014 were as a result of sexual relationships with fellow students.[37] Notwithstanding this finding, the study also shows that girls are victims of sexual abuse, or are pressured into sexual relationships, by their peers or adults –teachers, shopkeepers, taxi drivers—who exploit their vulnerability, and their inability to negotiate protected sex.[38]

In 2015, a UN expert body on women’s rights expressed “profound concern at the level of sexual violence to which girls are subjected [in Senegal], particularly at school, which is often followed by early pregnancy.”[39]

II. Senegal’s Legal and Policy Framework on Sexual Exploitation, Harassment and Abuse

Senegalese legislation does not specifically stipulate a minimum age for sexual consent.[40] The country’s Penal Code does not include a specific criminal offense for anyone who has sexual relations with children under 18. Most sexual offenses cover acts of sexual abuse of children under 16.

Senegal’s penal code narrowly defines rape as “any act of sexual penetration [of any kind] … committed against a person through violence, coercion, threat or surprise.”[41] Rape is punished with five to ten years imprisonment. Rape or attempted rape of a child under 13 years of age, or a person who is particularly vulnerable because of pregnancy, advanced age or health condition leading to a physical or mental disability, carries the maximum sentence.[42]

Molesting a child under 13 years of age carries a sentence of two to five years imprisonment.[43] The penal code also criminalizes “harassing others by using orders, gestures, threats, words, writings or restraints in order to obtain favors of a sexual nature by a person who abuses the authority conferred on him or her.” If a victim is under 16, a perpetrator can be imprisoned for three years.[44] Moreover, acts constituting pedophilia –a crime under Senegalese law—are defined as “any gesture, touching, caressing, pornographic manipulation, use of images or sounds… for sexual purposes on a child under 16 of either sex.” [45]

If any acts of a sexual nature, or attempts to act, are perpetrated by an adult who has “authority over the minor,” those “responsible for their education,” or state officials, among others, the perpetrator will be imprisoned for 10 years.[46]

The penal code does not include a specific offense for omitting to report a sexual offense committed against a child. However, not reporting a crime listed in the penal code, particularly where reporting it could prevent further offenses, is subject to a sentence of up to three years, or a fine of up to 1 million FCFA (Us$1,887).[47]

Teachers’ Ethical Responsibilities

Senegal lacks a binding national code of conduct that outlines the obligations of teachers, school officials and education actors vis-à-vis students.[48] Schools are expected to define their own regulations around student and teacher discipline, but the Ministry of National Education does not provide parameters to shape the content of these regulations.[49]

The teachers’ professional and ethical code – an oath sworn by all members of the teaching profession - is the only non-binding document that stipulates teachers’ commitments toward their profession, students and society, among other groups. Teachers pledge to protect students from any form of sexual abuse, and to avoid any form of verbal abuse, particularly discriminatory language, frustration or stigma.[50]

Once they are certified to teach, teachers also swear by an oath that includes the following commitments to protect their students:

I forbid myself to voluntarily be a cause of wrong or corruption or any seduction with regard to students, girls or boys ... I pledge to protect girls and boys against all forms of abuse ... I swear never to use my authority over students for sexual purposes ...[51]

In addition, they pledge that “my position in school gives me a special responsibility in the education and training, of girls and boys, [and] their protection against any form of aggression, including sexual remarks or attitudes.”[52]

III. Sexual Exploitation, Harassment and Abuse by Teachers in Schools

There are teachers who tell you “go out with me, I am going to give you resources.”

—Amy, 17, Medina Yoro Foulah, October 2017

Different forms of sexual violence remain pervasive in secondary schools in Senegal.[53] Human Rights Watch found that school-related sexual exploitation and harassment by teachers is a significant, yet oft underreported problem in secondary schools. [54] Students are particularly vulnerable to these abuses on the way to school, around teachers’ homes, as well as during students’ evening gatherings, which are sometimes organized on school premises.[55]

Teachers abuse their position of authority when they approach their students for sex, in violation of their professional ethics, and in some cases, when girls are younger than 16 years old, under Senegalese law.

In some of the areas where Human Rights Watch conducted research, the low retention rate of girls appears to be closely linked to fear that girls will be exposed to sexual harassment and gender-based violence in school, or that girls will be at high risk of pregnancy because of the school environment.[56]

Overview

Human Rights Watch found that some teachers and school staff have sexual relationships with female students, many of whom are children at the time this happened. Six girls and young women told Human Rights Watch that they had suffered sexual exploitation, harassment, or abuse in the school context. A further 10 girls and young women provided information on cases of sexual exploitation, harassment, and abuse of friends or relatives.

Although Human Rights Watch makes no claims about the scale of school-related sexual exploitation, harassment or abuse by teachers in secondary schools across all of Senegal, the evidence we obtained in the regions where we conducted research suggests that taboos and social stigmas have silenced many girls and young women who are affected by school-related sexual exploitation, harassment and abuse. The findings in the following sections are consistent with evidence gathered by the government, UN agencies and national and international organizations, which show that school-related sexual and gender-based violence is a serious problem in the education system, and that these abuses take place in the regions where we conducted the research, as well as in other parts of the country.[57]

Some of the cases included in this section were, according to evidence gathered in schools and communities, most often characterized by students—and to a certain extent, teachers and school officials—as “relationships” between teachers and students. Human Rights Watch believes that such characterization can undermine the gravity of the abuse, affect reporting of such abuses, and blur school officials’ perception of the severity of these abuses.

In recent years, some teachers have been prosecuted for raping or sexually abusing students. Although these prosecutions have conveyed a strong message that sexual abuse against children will be punished severely, many other abuses—notably sexual exploitation by teachers—go unpunished.

Unsafe Way to SchoolSexual exploitation, harassment and abuse of students also happen regularly as girls and young women are in transit to and from school. Students are exposed to a variety of risks: harassment and sexual exploitation from commercial motorcycle drivers–colloquially known as “Jakarta men”—who transport students to schools, shopkeepers or other adults who come in contact with children, as well as harassment–and in a small number of cases, rape—by military personnel stationed in checkpoints close to schools.[58] In cases documented by Human Rights Watch, drivers offered girls—who often travel long distances to school and cannot pay for transport—rides for sex. Most motorcycle drivers are adult men, although some older boys who have dropped out of school prematurely also join the motor taxi sector. [59] |

Teachers’ Abuse of Power

If you refuse [him], he gives you really bad grades or he fails you.

—Kodda, 17, Medina Yoro Foulah, October 2017

All school principals interviewed by Human Rights Watch condemned sexual abuse or harassment against students, and most did not openly acknowledge any contemporary cases of sexual harassment in their schools. Yet, based on individual interviews and group discussions with students in five schools, Human Rights Watch found that some teachers are engaging in “relationships” with students in those schools – which, in many cases, would constitute sexual offenses—and students are regularly exposed to sexual harassment and unwarranted sexual overtones by teachers.

Several students described to Human Rights Watch how teachers attempted to exploit or coerce female students, offering them money, better grades, food or items such as mobile phones and new clothes.[60] The government’s study on sexual and gender-based violence in schools, quoted in a previous section, shows that the girls surveyed reported that they experience coercion “like a grave and recurring form of violence.”[61]

In at least three instances documented by Human Rights Watch, teachers approached their students by demanding a favor or requesting their phone numbers in private. According to Maïmouna, 16, who lives in Medina Yoro Foulah, “Teachers take students numbers and call them at night.” In her case, her French teacher sent her to get water for him, and then asked her to take it to his room in the school: “But after, he met me there and asked for my phone number.” Maïmouna refused.[62]

A school principal in Sédhiou told Human Rights Watch how one of the teachers in his former school in rural Sédhiou harassed a student. He investigated the case because the student’s mother threatened the teacher with legal action: “[It was about] a child in the 5eme year – she was 13 or 14. I called them [teacher and student] and she told me everything. In that case, the student’s mother filed a report [with the principal] … she said it had to stop or they would meet in the tribunals. So, this was severe. It was a case of harassment and coercion… [the teacher] used to say ‘I’ll see you at home.’ Really, it was fishy. He said: ‘if you don’t love me … I will give you zero [in exams]’ [and] ‘I called you, you gave me your number, and you haven’t called me’.”[63]

Some students also told Human Rights Watch they feel pressured to obtain good grades in the “Brevet de fin d’études moyennes,” an exam that allows students to proceed to high school, and the “Baccalaureate” exam, at the very end of high school. According to some students, it is very difficult to pass these exams, and many will end up re-sitting the year in order to obtain a better grade.[64] As a result, girls are particularly vulnerable to sexual exploitation in the academic year leading up to the exam.

The frequent phenomenon of sexual exploitation for grades is often colloquially referred to as sexually transmitted grades (“notes sexuellement transmissibles” in French), and, according to nongovernmental groups and media reports, it happens in both urban and rural areas.[65]

Hawa, 17, who is a member of the young female leaders group in her school in Sédhiou, finds that “relationships” for grades are commonplace in her school. She told Human Rights Watch: “Teachers tell you ‘If you have a relationship with me, I can ensure you will be the best one in the class.’” Hawa’s close friend was sexually harassed by a teacher when they were 15 years old, in the 5eme year of lower secondary school. He offered her better grades and support to help her mother, but Hawa’s friend refused. The same teacher has allegedly also approached two other girls in Hawa’s class.[66]

In four cases, girls told Human Rights Watch they felt teachers graded them badly, ignored them in class or did not let them participate when they turned down their sexual advances.[67]

Aïssatou, 16, from Sédhiou, said:

One day, he [the teacher] asked me to go to his house. When I went to his house, he offered to give me money and resources. And I told him no… because when they tell you that, they’re going to impregnate you and will leave you on your own. I was a bit stressed. It was in his house. He became nasty, [he said] he was not going to give me good grades.[68]

After a series of bad grades, Aïssatou decided to speak to her principal who, in turn spoke to the teacher about the allegations. According to Aïssatou, even though her teacher denied the allegations, the teacher’s advances stopped, and she did not experience any retaliation, after the principal’s intervention. She was not aware of any further disciplinary action against the teacher beyond this discussion. The same teacher sexually exploited at least one other girl including one of her friends: “He ended up impregnating her. The teacher is still there, but he goes out with other girls,” Aïssatou said.[69] She was not aware of disciplinary or judicial sanction taken against him.

Cases of Sexual Exploitation by Teachers

Human Rights Watch documented 10 cases of sexual exploitation and abuses in the context of “relationships” between teachers and students, most of whom were 15 and 16 years old when the abuse took place. Various girls and young women referred to teachers who have had multiple “relationships” with students during their placement at the school.[70] The “relationships” were largely known by teachers and some principals, but disciplinary actions were not taken in most cases.

Fanta, now 23, from a village in Sédhiou region, had “a relationship” with her 30-year-old teacher for nearly two years, which started when she was 16 years old and resulted in a pregnancy that ended her education:

I was in his class … it was always hidden. The teacher had given me an exercise to complete at his house. After that, we were like this [together]. We would meet at his house. Some teachers knew about it, but they said nothing. I felt ashamed in class … my classmates knew I was going out with him. [71]

In a middle school in Sédhiou, at least two girls referred to cases of teachers who had made students pregnant. Aïcha, 15, who is in the final year of middle school, told Human Rights Watch: “We have a lot of problems as girls … there are teachers who approach young girls.” She told Human Rights Watch a teacher had “a relationship” with one of her classmates:

A teacher is in prison because of that … since last year, 2016. He went out with a girl in secret. She was 16 years old. After that, she became pregnant. He has refused to accept that it was him. When the girl had the baby [they] did a DNA test and [they] imprisoned the teacher. The girl's parents brought a claim [against the teacher] … The girl is not at school, she stays at home.[72]

Penda, 17, who studies in the same school in Sédhiou, also told Human Rights Watch her friend had a “relationship” with her mathematics teacher when she was 15 in the 4eme and 3eme year of middle school. Her friend moved to a private school, and the relationship ended there. But according to Penda, the teacher, who lives in her neighborhood, has had “relationships” with other girls in her school, one of whom was 16.[73]

Maïmouna, quoted previously, told Human Rights Watch that her friend, who was 14 at the time, had a secret “relationship” with a teacher. The teacher used to call her and visit her at night. “He used to see her often, during two years. The teacher gave her money, and she used to hide this [the relationship] from her family.”[74]

Relations between teachers and underage students remain unlawful regardless of a student’s age or her consent to engage in sexual relations with a teacher. When a student is under 16, these so-called “relationships” constitute rape under Senegal’s penal law. However, teachers and school officials – all of whom are in a position of authority—could also be found guilty of sexual offenses against a child carrying the maximum penalty of 10 years.[75]

Teachers also engage in “relationships” between students who are older than 18. According to one school principal, teachers who are as young as 22 or 23 during their first placement may have fewer qualms with dating students who are slightly younger than them.[76] Although relationships with students over 18 are not illegal or qualify as a sexual offense against a child under Senegalese law, they may well be unethical and exploitative, and a violation of a teacher’s ethical obligations.

Sexual exploitation occurs when teachers abuse their position to exert undue power on students they teach, influence or appear to have power or control over. This breaches a teachers’ duty of care, and ethical responsibilities toward their students. School officials should not tolerate any instances where teachers or school officials abuse their power for sexual purposes. They should enforce a policy that prohibits “relationships” between teachers and school officials –who exert power and authority—and students in school and outside school.

Unwarranted Sexual Overtones and Inappropriate Behavior in Schools

Teachers’ inappropriate advances or proposals affect the learning environment, and make some female students feel wary about their teachers. Some teachers use inappropriate language or gestures when talking to female students or referring to other students in their class.[77] Some of these acts can constitute the sexual offense of sexual harassment, and are in clear violation of teacher’s ethical obligations.[78]

In the village of Ounck, in rural Ziguinchor, Aïssatou, 16, told Human Rights Watch she felt uncomfortable when her teacher approached her at the beginning of the school year: “He told me, ‘what’s your name? where are you from? I like you a lot.’ I told him ‘I don’t like you. I don’t go out with teachers.”[79] Similarly, Nafissatou, 17, who lives in the neighboring village of Congoly said: “The teachers tell [us] ‘I love you’ often … there are teachers who have relationships to get married, and others to ruin you.”[80]

Soukeyna, now 20, recalled her unwelcome encounter with her teacher in middle school: “One day, he called for me and talked to me about my studies. All of a sudden, he told me he would be happy if I became his third wife.” Although the teacher did not pursue her further, his proposal had a strong impact on Soukeyna’s trust in teachers: “It’s something that really affected me. I was used to having a good relationship with my teachers. Psychologically, it affected me.”[81]

At least three girls reported being smacked on their buttocks.[82] Amy, 14, from Ounck, said that one of their teachers smacked her buttocks with his hand: “Girls don’t say anything… [but] this is not good. We don’t want them to hit us or touch us.”[83]

To avoid a bad experience at school, some girls told Human Rights Watch they “protected” themselves by becoming distant with teachers. Students appeared to feel maintaining appropriate boundaries with their teachers was their own responsibility. Many students said that they did not give teachers opportunities by not “provoking” or “tempting” them.[84] In particular, they avoided going to the teachers’ room, did not search for teachers outside classroom time, and dressed modestly to avoid attracting a teacher’s attention.[85]

In some interviews and group discussions, girls said students’ choice of outfits are to blame for unnecessary attention from teachers.[86] For example, in one group discussion at a middle school in Sédhiou, girls felt that an important way to avoid having problems, was to avoid using any “sexy outfits, [not] show your breasts… so that you [don’t] tell men you are ready.”[87] This type of damaging message, which places the burden and blame on girls for teachers’ actions, is often propagated by teachers, school officials and parents.[88]

Tackling the stereotypes that make girls feel that they are guilty for provoking sexual exploitation and abuses committed against them should be a top priority, according to Ndèye Fatou Faye, a psychologist at the Centre Guidance Infantile et Familiale in Dakar. Faye believes that schools and communities should stop blaming girls for exploitation, focus more on training teachers on their professional responsibilities, on ways to prevent sexual violence, and on how to recognize telling signs that children are suffering sexual abuse.[89]

With a view to ending the culture of silence around school-related sexual exploitation, harassment, and abuse, as well as abuses by other peers and adults, the government should support a public education campaign directed at students and young people. The campaign should be developed in consultation with young people, and should cover what constitutes unacceptable behavior by teachers and adults with authority over students, ways to raise concerns and report abuses, and mechanisms to report these confidentially.

IV. Limited Progress on Tackling Sexual Exploitation, Harassment and Abuse in Schools

If girls accuse a teacher [of harassment], and tell the principal, the teacher will deny it. Girls are afraid of denouncing – they [the administration and the teachers] can even destroy our career.

—Penda, 17, Sédhiou, October 25, 2017

Although prosecutions for school-related rape have occurred, Human Rights Watch’s evidence suggests that prosecution or redress for sexual exploitation or harassment has been rare. The reporting system is generally weak, as victims of abuses are reluctant to report cases within schools. Human Rights Watch also found that education officials often do not act on or report to their own supervisors cases of sexual exploitation or harassment that have been brought to their attention.

At the school level, senior school officials do not appear to take action to tackle or prevent all prevalent forms of sexual exploitation—such as inappropriate advances or “relationships” between students and teachers—which in some cases, constitute sexual offenses.

In Senegal, talking about sexual harassment is considered a taboo topic for girls and women alike.[90] In many cases, girls affected do not report sexual abuse. As a result, young survivors of rape and other forms of sexual violence, and those affected by exploitation, rarely see their cases to court and perpetrators punished. Girls’ also rarely get access to appropriate health services or the police.[91]

Rape Prosecutions

Since the late 2000’s, the local media has consistently reported the trials of teachers charged with sexual offenses of rape and acts of pedophilia linked to school, prompting widespread concern that students were exposed to school-related sexual violence.[92] Human Rights Watch is concerned about how often these reports reveal the exact identity of young survivors of rape, their location, and the details of the offense.[93] According to Seckou Balde, head of psychiatric health at Kolda’s health centre, the lack of protection of the survivor’s identity and the negative portrayal of survivors in the media deter young survivors from coming forward with cases.[94]

Government officials who spoke with Human Rights Watch believe that cases of school-related rape by teachers have diminished overall, due in part to a steady number of prosecutions of teachers, and an increase in child protection mechanisms at the local level.[95] Yet, this might be based on a perception: legal experts and government officials who spoke with Human Rights Watch were only aware of a handful of prosecutions of teachers or school staff for rape.[96]

In Dakar, the local media has reported at least 14 school-related rape trials since 2013, and over 10 in Kolda, Sédhiou, and other parts of the country.[97] Human Rights Watch learned, through interviews, of at least seven prosecutions in Dakar, and the regions of Kolda and Ziguinchor. For example, in Medina Yoro Foulah, the northernmost region in Kolda, a teacher was sentenced to four years imprisonment for raping a 12-year-old student in his office at the school in 2014.[98] In Ziguinchor, a teacher was prosecuted for raping a 16-year-old student in school.[99]

While these prosecutions have sent a signal that rape by teachers is intolerable, sexual exploitation and harassment continue to be serious problems.

Limited Accountability and Action Against Perpetrators of Sexual Exploitation and Harassment

Human Rights Watch evidence suggests that teachers who have sexually exploited students in the context of “relationships” usually do not face serious legal sanction or professional sanction. Their behavior is sometimes tolerated or at most, they are reprimanded or warned by their peers or the principal, with no further consequences. Repeat offenders, such as teachers who sexually exploit more than one student during their tenure at the school, attests to the impunity they appear to enjoy.[100]

In a middle school in Sédhiou, where several students reported experiencing sexual harassment by teachers, a senior teacher told Human Rights Watch that one of his colleagues had “gone out” with three students. The teacher said: “In this school, there are teachers who run towards their students. Last year, there were three girls in this school [targeted by one of the youngest teachers] – one of the girls, her parents were aware, and they complained.” Although the former principal admonished this teacher, he still teaches at the school.[101]

The teacher who abused Fanta and made her pregnant, mentioned in a previous section, continues to teach at the local middle school in a village in the Sédhiou region.[102] Fanta’s father spoke with the principal, but the school did not conduct an investigation.[103]

Hawa Kandé, gender focal point at the education inspectorate in Kolda region, told Human Rights Watch that even though reporting sexual abuse is anonymous, “relationships [between teachers and students] are so commonplace, they [teachers] have trivialized them.”[104]

Several people reported cases of teachers marrying their students including in cases where girls are impregnated by their teachers.[105] In some cases the families negotiated an informal financial settlement to cover the cost of antenatal and health checks for a girl during pregnancy and a basic stipend.[106]

For example, Koumba Ndiaye, a women’s advocate in Medina Yoro Foulah, a small town close to the border with The Gambia, in 2011 mediated the process of a girl who was sexually abused by her teacher, in the context of a “relationship,”: “She was 16. The teacher financed her, [gave her] a mobile phone … once she fell pregnant, her father kicked her out of her house.” Ndiaye described how she negotiated with the teacher so that he would pay the expenses for the birth and baby’s maintenance. As part of this negotiation, Ndiaye demanded that the teacher request a relocation to a different region. Neither Ndiaye nor the girl’s family filed a complaint against the teacher to police.[107]

Community Pressure to Avoid Proceedings

In most small towns and villages where Human Rights Watch conducted research, families frequently resolved cases of rape, sexual exploitation, and violence without involving either the judiciary or school, that is, within their home or community. Often, when parents find out that a girl or young woman is pregnant outside marriage, they prefer to settle conditions with the baby’s father, or arrange a marriage between them.[108] This is commonly referred to as “maslaha” and “jokere endam” meaning “in the common interest” in Wolof and “preserving kinship” or “good neighborhood” in Pulaar language, respectively.[109]

Mariama Barry, a local advocate leading a local women’s brigade to end violence against women in Kolda, told Human Rights Watch: “They [young girls] are really scared to speak about sexual violence … people don’t have a habit of denouncing and talking about their problems.” Barry told Human Rights Watch that many mothers warn their daughters to not talk about any such incidents: “It’s what troubles the community – if you take someone to court, you will be isolated.”[110]

Some communities afford teachers and school officials, who are very often posted from other parts of Senegal, special status, due to their level of education and the role they play in the community. This makes it harder to denounce any acts of exploitation or abuse perpetrated by teachers, and contributes to a culture of silence around unlawful acts that take place in schools.

When Fanta, now 23, first told her parents she was pregnant from her teacher, they expelled her from their house.[111] Fanta told Human Rights Watch she felt ashamed in her class because her classmates knew she had “a relationship” with the teacher, and the teacher denied being her child’s father.[112] Although her parents took her back, Fanta’s father told Human Rights Watch that in the village, “people look at you in a different way … our tradition really bans a girl from getting pregnant [outside marriage].”[113]

According to experts at the Centre de Guidance Infantile et Familiale, who provide psychological support to parents and children, parents are often reluctant to report abuse and exploitation because they worry about their community’s perception. Most parents hardly ever have access to professional services or support to help them handle abuses committed against their children.[114]

School-based Efforts to Tackle Sexual Exploitation, Harassment and Violence

A consistent, national strategy to end all forms of sexual violence in schools–particularly taboo issues like sexual exploitation and harassment—is missing.[115]

Secondary schools visited by Human Rights Watch have generally taken a strong stance against school-related sexual and gender-based violence as a whole, and focused on tackling financial and social barriers faced by girls in secondary school. Human Rights Watch found that this often stems from leadership and self-initiative by principals and committed teachers, rather than a national concerted effort, based on directives or regulations from the government.

National or regional efforts to prevent or reduce sexual abuse and exploitation are often closely linked to campaigns to prevent teenage pregnancies, and those aimed at empowering girls with information and providing essential items, including sanitary pads and school materials, without which many girls would face even more barriers to education.[116] Development partners, including donors and UN agencies, have largely provided financial or technical support through the Ministry of National Education’s “Coordination Framework for Interventions for Girls’ Education.”[117]

At the school level, some principals have focused on adopting a clear zero-tolerance policy toward sexual abuse or exploitation by staff in their school. For example, principal Tacko Koita, in Mpak village in Ziguinchor, regularly reminds her staff about their ethical obligations and warns her deputies and teachers about engaging in inappropriate, if not illegal, behavior with students: “As the principal, I speak to all of my deputies. They need to be warned. The law covers children who are minors. They have to know they have responsibilities. If something happens, they’ve been forewarned.”[118] Nevertheless, in spite of this warning, students who attended this middle school did report some cases of “relationships” and inappropriate behavior by their male teachers.[119]

In a school in Kolda, Lalia Mané, a middle school teacher and a member of the government’s girls’ education initiative, told Human Rights Watch that sexual harassment by teachers stopped after children went through extensive trainings on child rights and violence against children, and an observatory was put in place in the school. Mané said: “I tell my students, if there’s a teacher that asks you for favors … you must go press charges at the police station … I don’t hide it.”[120] Students at this school did not report any inappropriate advances or cases of sexual violence or exploitation during interviews with Human Rights Watch.

Some principals and school officials have also tried to adopt a compulsory school uniform policy to ensure all students are dressed according to standards set by the school administration and the parent teacher association. Unfortunately, this initiative responds to a common perception among school staff that female students’ clothes expose them to exploitation by their teachers.[121]

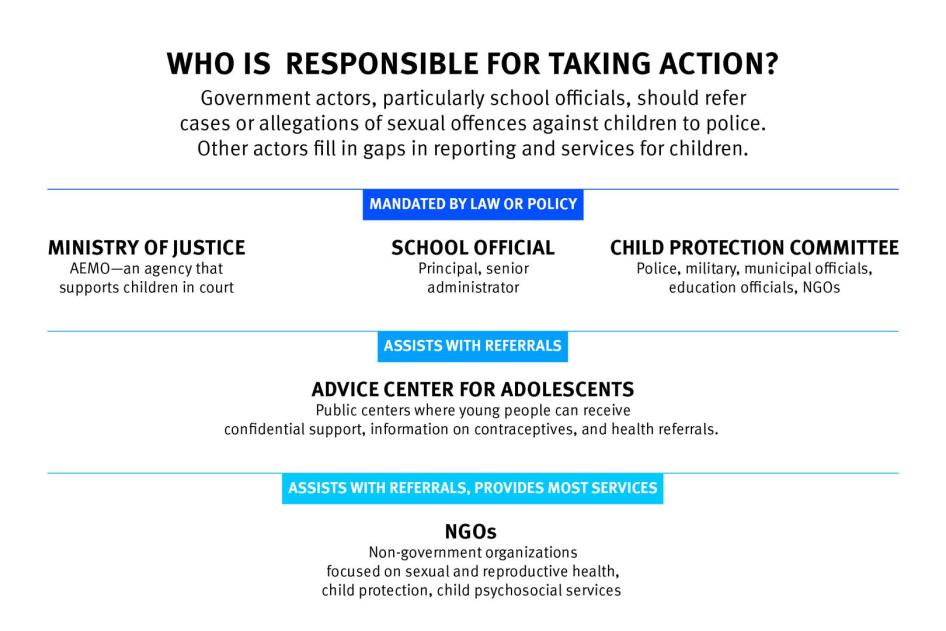

Dysfunctional Reporting System and Discriminatory Attitude of Principals

Child protection efforts in Senegal have historically been piecemeal, uncoordinated and under-funded.[122] In 2013, the government adopted a comprehensive national child protection strategy, aiming to establish an intricate child protection system that connects all relevant actors at the village, district, regional and national levels.[123] This new system introduced child protection committees, which were set up to bring together a range of education, judicial and local government representatives with NGOs and other actors that provide services to children affected by violence. It also aimed to strengthen coordination to prevent any forms of violence or abuse against children, and to improve reporting of child rights violations, wherever they may occur.[124]

Although the strategy is accompanied by a plan of action, the government has so far not allocated adequate resources to roll-out the strategy uniformly.[125] Human Rights Watch found a gap between this coordination mechanism and reporting at the school level, particularly around cases of sexual exploitation, harassment, and abuse.

According to the chief of education inspection in Vélingara, in the Casamance region, guidance for school officials is clear: every three months, school principals must send reports of any cases related to child protection issues–including on sexual and gender-based violence, as well as pregnancies and cases of female genital mutilation—to local education inspectorates.[126] The education inspectorate will in turn, report these within the education system and inform the relevant child protection committee.[127]

In theory, principals are legally obliged to report cases of rape or other criminal incidents, directly to police. They should also report other child rights violations or incidents affecting students to child protection committees. Once a case is reported to a relevant child protection committee, a range of actors, including child protection officers, police, and prosecutors, are involved in the response, which in some cases, requires adopting urgent measures to assist or protect a child.[128]

Human Rights Watch identified three key factors which undermined the consistent reporting of sexual exploitation, harassment, and abuse against students by their teachers and other school staff: cultural perceptions that girls and young women are responsible for their teachers’ advances; a concern over losing teachers given the deficient number in especially rural areas; and the lack of clarity on what comprises sexual exploitation.

Barriers to Reporting at the School Level

A principal wants to protect his staff. Teachers can have lots of problems… You have to talk to him so that he stops. [If not], he risks ten years in prison.

—School principal, Kolda region, October 2017

Human Rights Watch found that principals generally wield great influence over whether or not cases of sexual exploitation, harassment, or abuse in schools were reported to police or education inspectorates. Several principals told Human Rights Watch they prefer to address any incidents of exploitation or abuse within school walls in order to protect their staff, and prevent scrutiny from education inspectorates.

School principals and teachers are not immune to the bias nor the community’s approach to dealing with cases of abuse. Part of the problem with reporting is the principal’s bias, as well as a lack of definition of sexual exploitation in school guidelines, and a prevalent culture of blaming girls.

Some principals told Human Rights Watch that they did not report cases because they did not fully trust students’ allegations of sexual misconduct by their staff.[129] Some principals and school staff also talked about students’ volatile adolescent behavior, students’ desire to attract attention, and the way some students “tempted” their teachers by wearing tighter or shorter clothes.[130]

According to a former school principal interviewed in Dakar:

Girls have their periods, they are mature girls. [There are] girls who provoke [their teachers] or teachers who are practically from the same generation as girls … the risk is very big. Girls go see their teachers with the excuse of learning at the teachers’ house.[131]

Yet, several education staff said they are reluctant to report teachers out of concern for losing already limited staff and suffering reputational damage.[132] A school principal in a village in the Kolda region explained:

If a girl has been harassed, we call the teacher. We try to listen to him, and we investigate. We don’t call the departmental committee for child protection … if you call them, the teacher will face problems. We try to solve this amicably. [133]

Human Rights Watch did not find evidence of a specific legal obligation for principals and senior school officials to report criminal sexual offense to the police.

Beyond the principal, many schools have staff members and structures tasked with monitoring and reporting on child protection concerns in schools. Some school staff members are part of local child protection committees, part of the national committee of teachers to promote girls’ education (CNEP-SCOFI), or take part in an informal school observatory made up of students, teachers and school administrative officials to monitor vulnerable students and students at risk of dropping out of school.[134]

Some of the bigger secondary schools visited by Human Rights Watch have a hierarchy in reporting child protection concerns. Education or administrative staff must be informed of a problem first, prior to taking up a complaint or allegation to the principal’s level. In a school with more than 1000 students in Sédhiou, a principal told Human Rights Watch that usually the school supervisors (“surveillants”) or the lead teacher for every grade finds out first, and then assesses whether they need to inform him.[135] This hierarchy could constitute an additional barrier to reporting.

Even when teachers want to report harmful or unlawful behavior, some may feel they cannot for fear of accusing fellow teachers knowing the consequences they may face.[136] A middle school teacher in Kolda region told Human Rights Watch: “We are aware of some violence, but we do not dare denounce it.”[137]

Senior school officials should be obliged to conduct investigations following any allegations of misconduct and, where a criminal law appears to have been violated, refer alleged perpetrators to the police. The Ministry of National Education should issue a directive outlining school officials’ legal duty to report any incidents or allegations.

Principals must also be given comprehensive trainings on how to conduct initial investigations adequately and fairly, and where appropriate or needed due to the type of offense, report cases to higher education authorities, or immediately to the police. Those who fail to do so should be subject to disciplinary proceedings themselves, and if their behavior amounts to an obstruction of justice, criminal prosecution.

Deterrents and Barriers to Reporting Faced by Students

Human Rights Watch found that many students were reluctant to report sexual abuse and exploitation by school staff as a result of their limited understanding of what constitutes a sexual offense and unlawful behavior, unclear reporting system, and barriers to reporting, including the lack of confidentiality.

Many students do not fully understand what sexual offenses are, nor the full extent of avenues to report these offenses whenever they occur. This remains a fundamental problem in identifying the full extent of school-related SGBV. For example, a consultation with over 500 students in Dakar, led by the Centre de Guidance Infantile et Familiale, found that while students understand that rape is a crime and are inclined to report it, they would not recognize sexual touching, harassment, or attempted rape, as sexual abuse.[138] Human Rights Watch found that many students have normalized the reality of “relationships” in the school context, and although many identified it as something that was wrong, they did not perceive it as sexual exploitation. Schools should ensure students have a better understanding of what constitutes sexual exploitation, harassment, and abuse so that they can identify and report them.[139]

Girls and young women who have been harassed, exploited or abused by teachers, or other adults, have limited options to confidentially report an incident.

Some students told Human Rights Watch they would not seek help from their principals or teachers because they felt their claims would be dismissed. Some of the girls who spoke to Human Rights Watch about an abuse they suffered or a close friend’s case said they often share their experiences with friends, and take advice from them. Psychologists at the Centre de Guidance Infantile et Familiale in Dakar told Human Rights Watch that children often do not want to report abuse by an authority figure.[140]

However, there are a number of other obstacles too. In order to report rape at a police station, survivors must present a medical certificate.[141] Reporting a rape thus becomes a financial barrier for some young survivors. Although medical certificates can be obtained for free when attending drop-in support centers, a rape survivor has to pay around 10,000 Francs CFA ($19) in order to obtain one if she does not have a referral.[142]

In urban areas, well-known organizations like the Association des Juristes Sénégalaises, a national organization led by female lawyers, or the International Planned Parenthood’s Senegal chapter, the Association pour le Bien-Etre Familial (ASBEF), support survivors with access to judicial services and assistance. Children can also go to the Ministry of Justice’s child-focused legal assistance agency, the AEMO, which supports children through judicial processes.[143]

To ensure students actually report any incidents, the government needs to also tackle the stereotypes that make girls feel that they are responsible for sexual exploitation and abuse committed against them. In addition to providing trainings and workshops for teachers and students, the government should also embed gender issues in its long over-due curriculum on sexual and reproductive health education. The government should make reporting more accessible and confidential for all students –whether in the form of a trained designated teacher who lodges complaints confidentially, or a confidential reporting line into the relevant child protection committee.

Problems with Inspectorates and Child Protection Committees

Members of child protection committees in Ziguinchor and Vélingara consulted by Human Rights Watch lacked exact numbers of convictions of teachers for sexual abuse or of how many school-related cases have been reported to the committees.[144]

Within the education system, data gathering depends on what schools report to local or regional inspectorates, and what inspectorates do with that information. For example, the regional education inspectorate in Kolda had not compiled data on sexual and gender-based violence and exploitation in schools for the whole region.[145] At the sub-regional level, some data existed: In Vélingara, the head of inspection for this eastern region of Kolda, told Human Rights Watch he received 62 complaints or allegations of teenage pregnancies, and some cases of sexual harassment, during the 2016-2017 academic year, by students and adults who targeted girls close to school, or while they were on their way to school.[146] This inspector noted that when schools report abuse to local inspectorates, they do not always provide details of the perpetrator’s profile.[147]

Senior school officials also encounter problems with some inspectorates. In one case, a middle school principal in the outskirts of the town of Kolda told Human Rights Watch he had been let down by inspectors: “If there is a problem, you have to inform the next level. But that’s where things are hidden … they are the ones who don’t report this at the level of the inspectorate.”[148] The principal filed a letter of complaint for sexual abuses committed against a student on the way to school, but the letter never went through the system:

I don’t work with the inspectors. If I have a problem, I’ll work it out. They are scared … its complicity. There is no follow-up [of a case]. If there’s someone who is destroying a child, I can’t let him destroy her.”[149]