Introduction

“I felt like the world was falling down on me…. I was going crazy, thinking I can’t have a kid. I’m not prepared, I’m not ready economically…. I’d always thought of myself as becoming a successful lawyer or psychologist. I was horrified that my plans would have to be put on hold.”

—Samantha, on learning she was pregnant at age 17, April 2018

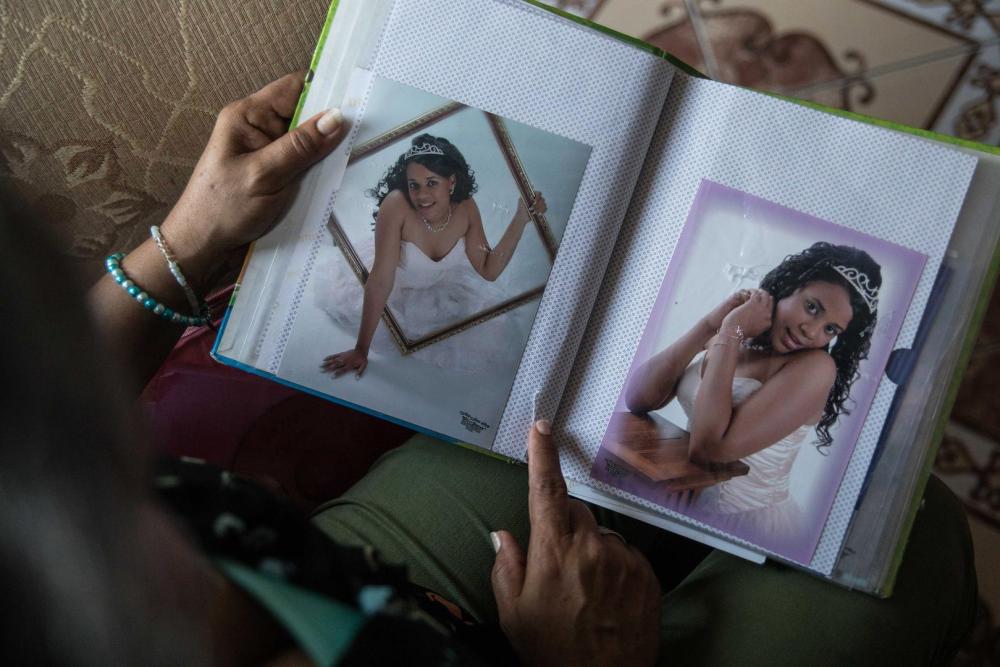

Lucely, 18, lives in a rural area in San Cristóbal province, on the outskirts of Santo Domingo, the capital of the Dominican Republic. At age 16, she had an unplanned and unwanted pregnancy. “Everything ended right there,” she said. Lucely—whose name has been changed to protect her privacy—first had sex when she was 14. At that time, she had very little information about preventing pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections. She said someone visited her school “once in a while” to talk to the girls and boys about sex: “They’d tell us not to have sex at an early age—that we shouldn’t be doing that,” she said. No one informed her about contraceptive methods or how to access or use them.

Lucely said she felt ashamed to go to a clinic and ask about family planning methods. She feared staff at the clinic would judge or criticize her for seeking family planning, or tell her family or other people in her community that she was having sex. “I didn’t want to [go to the clinic for contraception]. They say, ‘Oh, you’re so young. You’re already doing it?’”

When she found out she was pregnant at age 16, she was deeply distressed. Her partner was out of work, and she did not have support from her family: her mother lived far away, and her father was verbally abusive.

They did a sonogram, and I realized [I was pregnant]. I wanted to die. Oh my god. I felt alone in that moment…. I was almost in shock.

Lucely wanted to end the pregnancy, but abortion is illegal and prohibited in all circumstances in the Dominican Republic. Like many women and girls in her position, she tried to induce abortion clandestinely by drinking a tea made from plants and herbs, but it did not work.

Wearing a pink denim vest and jeans and chasing after her lively 2-year-old daughter, she told Human Rights Watch the pregnancy changed her life profoundly. “I never went back [to my life before],” she said. Without a support network to help care for her baby, she was unable to continue school and had to drop out of ninth grade.

I suffered a lot. My mom was far away. I was here alone. My father spoke badly to me. He’d insult me. He didn’t help me. I feel bad to even think about it. It’s like when you feel like no one loves you.[1]

Lucely is one of the 20.5 percent of girls and young women ages 15 to 19 in the Dominican Republic who become pregnant while still in their teens, most of them without having intended or wanted to do so.[2] Their fundamental human rights—to life, health, freedom from discrimination, and education, among others—are threatened by harmful policies and practices that deny them access to essential sexual and reproductive health information and services.

Adolescent girls need access to scientifically accurate, age-appropriate information about their sexual and reproductive health. The government of the Dominican Republic has not implemented a rights-based, comprehensive sexuality education curriculum in schools. This gap leaves girls and boys to navigate early sexual relationships without reliable information about how to protect themselves from unwanted pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections.

In many parts of the country, there is no place girls can go to access confidential, non-stigmatizing, adolescent-friendly sexual and reproductive health services. The Dominican Republic is one of few countries in Latin America and the Caribbean where abortion is criminalized and prohibited in all circumstances, even for women and girls who become pregnant from rape or incest, whose lives are endangered by pregnancy, or who are carrying pregnancies that are not viable, meaning the fetus will not survive outside the womb. Provisions in the civil code and other national laws facilitate the country’s high rate of child marriage, allowing children under 18 to marry with parental or judicial authorization. Girls, particularly those from poor and rural communities, suffer the consequences of these policy failures most profoundly.

The Dominican Republic has the highest adolescent fertility rate of all the countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, according to the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). While some adolescent pregnancies are planned and wanted at the time they occur, many are not.[3] The total ban on abortion in the Dominican Republic means adolescent girls facing unwanted pregnancies must choose between clandestine and often risky abortions or the lifelong consequences of having a child against their wishes.

Early pregnancy carries serious health risks for young mothers and their babies. Despite a law prohibiting the expulsion of pregnant girls from schools, pregnant students and young mothers often find it difficult, or impossible, to continue their education, due to a combination of harmful social stigma, inadequate childcare and support services, and exclusion or marginalization by teachers or school administrators. An unplanned pregnancy can therefore jeopardize a girl’s health and right to education, curtail her economic opportunities, and push her to marry at a young age, derailing the course of her entire life.

The government of the Dominican Republic has pledged to reduce adolescent pregnancy and eliminate preventable maternal death. Achieving these goals requires dedicated action by authorities to advance the sexual and reproductive health and rights of adolescent girls. Policymakers should act swiftly to:

- Provide adolescents with essential sexual and reproductive health information, including by implementing a mandatory comprehensive sexuality education curriculum in schools;

- Expand supportive and welcoming health services nationwide to receive girls without judgment or stigma;

- Decriminalize abortion and give girls the option to safely end an unwanted pregnancy; and

- Ensure pregnant and married girls and young mothers are never excluded or pushed out of school.

Recommendations

To President Danilo Medina, Cabinet Ministers, and the National Congress

- Implement the Strategy for Comprehensive Sexuality Education as a mandatory part of the curriculum in primary and secondary schools nationwide. Ensure that the strategy meets international standards and is scientifically accurate, rights-based, and age-appropriate. Ensure comprehensive sexuality education reaches students from an early age and builds incrementally to equip them with developmentally relevant information about their health and wellbeing. As part of the curriculum, provide children with practical information about how to use contraceptive methods and where they can obtain contraceptive supplies.

- Train educators to teach the curriculum impartially.

- Ensure health centers do not stigmatize adolescents who are sexually active, protect the confidentiality of all patients, do not impose parental notification and consent requirements for receiving services and contraceptive supplies, and that they are staffed with medical personnel qualified to provide comprehensive adolescent health services.

- Strengthen measures to reach out to adolescents to raise their awareness about access to contraception and reassure them of the availability and confidentiality of adolescent-friendly, non-judgmental services.

- Implement public information and awareness-raising campaigns that address the stigma around adolescent sexuality and promote healthy adolescent sexual practices. Ensure such campaigns make clear that adolescent children do not need an adult’s authorization to access sexual and reproductive health information and services.

- Decriminalize abortion as a matter of urgency, by removing all criminal penalties for abortion from the penal code. If necessary, as an interim step, at a minimum ensure women and girls can access safe and legal services when a pregnancy poses a risk to the life or health of the woman or girl, when the fetus has a serious condition incompatible with life outside the womb, and when the pregnancy resulted from any form of sexual violence.

- Enforce laws that prohibit schools from excluding pregnant girls from education or pushing them to alternative class schedules against their wishes. Ensure that pregnant students and young mothers who wish to continue their education can do so in an environment free from stigma and discrimination. Facilitate access to formal flexible school programs, such as evening classes or part-time classes, for pregnant girls or adolescent mothers who are not able to attend full-time classes. Ensure students receive full accreditation and certificates of education upon completion.

- Take immediate measures to ensure that all of secondary education is available and accessible to all free of charge.

Methodology

The accounts in this document are drawn from interviews conducted by Human Rights Watch in February, April, and October 2018. These interviews also informed an investigation of the criminalization of abortion in the Dominican Republic, published separately.[4]

Human Rights Watch spoke with dozens of women and girls of reproductive age, as well as adolescent children, young adults, healthcare and social service providers, and other experts in four provinces of the Dominican Republic: Santo Domingo, Santiago, San Cristóbal, and Monte Plata. Human Rights Watch identified interviewees with the assistance of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), advocates, researchers, and service providers. Among those interviewed were 10 adolescent girls and young women ages 15 to 19 who had been pregnant at least once, and 20 women who said they had a pregnancy before turning 18. Most interviews were conducted in Spanish through an interpreter. A few interviews were conducted in Haitian Kreyòl with the help of an additional interpreter.

Human Rights Watch informed all interviewees of the purpose of the interview, its voluntary nature, and the ways in which the information would be collected and used. Interviewers assured participants that they could end the interview at any time or decline to answer any questions, without any negative consequences. All interviewees provided verbal informed consent to participate. Care was taken with victims of trauma to minimize the risk that recounting their experiences could further traumatize them. Where appropriate, Human Rights Watch provided contact information for organizations offering legal, counseling, health, or social services. Human Rights Watch did not provide anyone with compensation or other incentives for participating.

In addition, Human Rights Watch analyzed relevant laws and policies and conducted a review of secondary sources, including demographic data, public health studies, and reports by other organizations. The names of women and girls, as well as service providers, have been changed to protect their privacy and safety.

Inadequate Sexuality Education in Schools

We know that there is a debt to the population on the subject of sex education.[5]

—Minerva Pérez and Bethania Leger, Ministry of Education, October 2018

The Dominican Republic has come under international scrutiny for failing to provide comprehensive sexuality education in schools nationwide, leaving adolescent girls and boys without essential information about safe sexual practices, healthy relationships, and their human rights.[6]

Authorities have stalled the rollout of a long-awaited revised approach to sexuality education, and hundreds of thousands of adolescent girls and boys are going without consistent, rights-based, scientifically accurate information about their sexual health. The United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) reported in 2017 that more than two-thirds of students in the Dominican Republic are not receiving comprehensive sexuality education.[7]

Government Approach to Sexuality Education

For years, sexual and reproductive rights advocates have urged the government to implement a comprehensive sexuality education curriculum in schools.[8] The Ministry of Education first introduced a national sex education program (Programa de Educación Afectivo Sexual, PEAS) in 2000, but the program was not a formal part of the curriculum, but rather an opt-in initiative left largely to the discretion of teachers or guidance counselors. Ministry officials explained that teachers did not receive extensive training in the program, and therefore schools implemented it inconsistently.[9] An August 2012 evaluation by UNFPA found major gaps in implementation of PEAS, estimating that the program only reached an average of 18.8 percent of matriculated students nationwide, and less than 6 percent of students in Azua, one of 12 regions evaluated.[10]

Several years ago, the Ministry of Education began a process of revising the entire national educational curriculum.[11] In 2015, it announced that it was incorporating comprehensive sexuality education into the national curriculum and developing training programs, guides, and materials for educators and counselors—known as the Strategy for Comprehensive Sexuality Education.[12] Fernando de la Rosa, head of education at Profamilia, explained the significance of this:

For us, it was a big step forward. They [MINERD] developed the training materials and the guides for all the grades in the system, and they are excellent. Materials that seem very appropriate and adequate. They began the training of principal personnel, the personnel in training and psychology at the schools.[13]

To begin implementing the Strategy for Comprehensive Sexuality Education in schools, the Ministry of Education must formally adopt the new curriculum with the approval of the National Board of Education (Consejo Nacional de Educación), a body established by law as “the highest decision-making body in matters of educational policy….”[14]

As of May 2019, the National Board of Education and the Ministry of Education had not formally approved plans for incorporating comprehensive sexuality education into the national curriculum, meaning the new guides and materials are not yet being implemented in schools.

A May 2019 departmental order by the minister of education mandated that an arm of the Ministry of Education—the Gender Equity and Development Directorate—design and establish “a gender policy” for the ministry and the entire pre-university education system, including tools to promote “non-sexist education” and “ensure that a gender focus is promoted from the educational curriculum.”[15] The order, issued on May 22, 2019, was based on a constitutional recognition of gender equality,[16] and set a deadline of 60 days for the directorate to create a methodology to implement the gender policy. Advocates told Human Rights Watch that, in their view, fulfillment of the objectives of this departmental order would require implementing comprehensive sexuality education in schools. The order was welcomed by several universities and nongovernmental organizations, and denounced by several religious authorities.[17]

Comprehensive Sexuality Education (CSE): A Rights-Based ApproachThe United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) defines comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) as “a curriculum-based process of teaching and learning about the cognitive, emotional, physical and social aspects of sexuality. It aims to equip children and young people with knowledge, skills, attitudes and values that will empower them to: realize their health, well-being and dignity; develop respectful social and sexual relationships; consider how their choices affect their own well-being and that of others; and, understand and ensure the protection of their rights throughout their lives.” CSE goes beyond providing information about human anatomy, reproduction, risk, and disease; it aims to empower young people to build healthy and respectful relationships. According to UNESCO, CSE programs should be:

A UNESCO review of studies measuring the impact of sexuality education found that curriculum-based sexuality education programs do not increase sexual activity, sexual risk-taking behavior, or rates of HIV or sexually transmitted infections. On the contrary, such programs contribute to delayed initiation and decreased frequency of sexual intercourse; decreased number of sexual partners; reductions in risky sexual behaviors; and increased use of condoms and contraception.[18] |

Experiences with Sexuality Education in School

Human Rights Watch spoke with children and young adults about the information they received in school or outside of school about sexual and reproductive health and rights. Their experiences varied widely.

Some young people interviewed by Human Rights Watch said they received almost no information about sexual health at school. Ana Paula, a 16-year-old mother, held her one-month-old baby in her arms as she told Human Rights Watch that no one at her school had spoken with her about sexual health before she became pregnant at age 15 while she was in eighth grade. “I heard that they are supposed to [teach sexuality education] in high school, but I never got there because I left,” she said, explaining that she transferred to nighttime classes when she was pregnant because the school did not accept pregnant students attending regular classes during the daytime.[19]

Adelyn, a 20-year-old woman with a 3-year-old son, was 6 months pregnant when she spoke with Human Rights Watch. She dropped out of school at age 14 after the second year of high school, and later enrolled in weekend classes to get her diploma. She said that up to that point, she had not received any sexuality education at school. “Nothing,” she said. “I think they should teach it,” she said, “There are a lot of girls getting pregnant. A lot of [sexually transmitted] disease.”[20]

A few interviewees said they only received lessons about sexuality as part of teaching around religion or morality. Samantha, 18, told Human Rights Watch her school did not give even basic information to students about sexual health.

We have a subject called moral civics, and they think because they have that [subject], they can’t have sexual education at the same time.… They teach human values, tell us to find God, to walk on the path of goodness.… You can’t say, ‘Walk toward goodness.’ We have no teaching that helps us once we are engaging in sexual activity.[21]

Karen, an 18-year-old mother, said the teacher of a human development course she took in ninth grade did not educate students about sexual and reproductive health, but instead taught about religion and showed her class a video about abortion.

In school, they showed us video about the way they do the abortion. They showed us that people die as a result of abortion. They showed us how they practice an actual [surgical] abortion. They told us abortion was dangerous, especially when you’re young, if you’re afraid to tell your parents [about a pregnancy] or if you try it yourself with pills or whatever.[22]

Some interviewees said they received information in a workshop or from a teacher at school, but in a manner that was too brief and fleeting for them to retain the information, despite international standards urging that these subjects be reinforced over the course of several years.[23] For example, Rayneli, a 15-year-old girl interviewed by Human Rights Watch who had been pregnant and miscarried twice in her life, said a teacher at her high school passed out condoms to students and showed them how to use them. “It was just one time that I remember. I don’t think they give enough information,” she said.[24]

Lisbeth, a pregnant 16-year-old girl in Santo Domingo, said that her only experience with sexuality education at school was when one of her teachers assigned her class to do computer research about sexually transmitted infections, and said that condoms should be used to protect from pregnancy and disease.[25]

Some teachers and school administrators seemed to take the initiative to teach students about sexual and reproductive health, or to bring health educators from NGOs to facilitate workshops. Samantha, 18, said she received some information about sexual and reproductive health through an outreach program in her community organized by an NGO. “It was useful because they explained about male and female condoms, family planning methods, anatomy,” she explained. “They taught us things with no taboo. It was all things people don’t speak about with family.”[26]

Karen, an 18-year old mother, said that occasionally representatives from an independent organization visited her school to teach students about sexual health. “They would come from outside [of school] to do some workshops. They gave the boys condoms and the girls sanitary napkins.” But she felt she did not receive enough information. “They came only two or three times a year,” she said. At age 16, she became pregnant.

If they’d taught me [how to prevent pregnancy], I wouldn’t be in the same position. If they had trained me, I wouldn’t have had to go through what I went through. There wouldn’t be as many teen pregnancies.[27]

At one school in northern Santo Domingo, seventh and eighth grade students told Human Rights Watch that their teachers educated them regularly about sexual and reproductive health in their science and human development courses, including by giving them information about contraceptive methods. The principal explained that the school took the initiative to start a program to try to prevent teen pregnancy, with some technical assistance from the district. The principal argued that a standardized sexual education curriculum was needed, citing the high rate of adolescent pregnancy in the community in which her roughly 700 pupils live: “It’s a necessity for the population.”[28]

The children at the school expressed interest in the information they had received about sexual health, and said they wanted to learn more. “It’s really important,” one girl said, describing how her friend had left school a year earlier due to an unplanned pregnancy. “They should have a sex education teacher to talk more comprehensively about it,” she said, arguing that a dedicated subject on sexuality education would equip students with better information and skills.[29]

Myrna Flores Chang, manager of the Gender and Rights Program at Profamilia—an NGO that provides sexual and reproductive healthcare services and education, including to adolescents—explained the inconsistency in schools’ approaches to sexuality education:

Since it is not a compulsory subject, it is up to the good will of the teacher. So maybe a trainer comes to the school to give a workshop on sex education, or the biology teacher gives the biological aspects of human sexuality, and that’s it. If you get a teacher who talks to you about everything [related to human sexuality], you’re saved. But that’s not common. That’s the problem. The state is not guaranteeing sex education for the students as it should be.[30]

|

Experiences of LGBT Youth

The sexuality education program currently in place in the Dominican Republic, Programa de Educación Afectivo Sexual, or PEAS, does not include any teaching around LGBT issues. The five LGBT children and young adults interviewed by Human Rights Watch said they felt marginalized and excluded in the limited conversations around sexual and reproductive health and rights that took place at their schools. Emily, an 18-year-old high school student in San Cristóbal province who identifies as part of the LGBT community, said a teacher at her school spoke about adolescent pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections, but she felt that the program was not inclusive of the experience of LGBT students. They don’t talk about how LGBT students can protect themselves. I thought about asking my teacher, ‘What would you say about LGBT students?’ I tried [to get the courage to ask], but I didn’t. She described some incidents of bullying or discrimination against LGBT children at school and in her community. “[The school] should talk about accepting people the way they are,” she said. “[I]t would help people understand and accept that people who like people of the same sex, it’s normal. They wouldn’t discriminate.”[31] Alicia, a 17-year-old lesbian, told Human Rights Watch that a teacher in her human formation course talked with students about sex only once. She told Human Rights Watch that the limited teaching offered by her school was not inclusive of LGBT students’ experiences. “They didn’t speak about it…. We face a lot of discrimination.”[32] Diego, a 17-year-old LGBT student, said that rather than receiving sexuality education relevant to LGBT issues, he faced outright discrimination on the basis of his sexual orientation in a public high school in Santo Domingo. One of his teachers denounced him for his sexual orientation in the presence of other students: He always expressed that it was bad to be gay…. He confronted me in front of the whole class, so that empowered other students to continue discriminating against me. Because teachers are supposed to be leaders, and if they say, ‘It’s wrong to be gay,’ students won’t question it. Diego chose not to file a complaint against the teacher, but he transferred schools.[33] Even at his new school, he had never received sexuality education of any kind, let alone LGBT-inclusive lessons. The only sexuality education given to students at his school was the distribution of a booklet with information about teen pregnancy and contraception. “We are really in need of sex education,” he said. |

Opposition to Implementing Comprehensive Sexuality Education

Ministry of Education officials explained that the roll-out of a new approach to comprehensive sexuality education has been intentionally slow—starting with a pilot program to test the guides in 30 schools—as it’s a “delicate” topic:

It is a subject that deserves a certain level of consensus where most of us can understand what is being proposed. We have chosen to take it little by little so that when it is installed, it will be implemented with clarity.[34]

Advocates believe opposition from the Catholic Church hierarchy and other socially conservative groups is contributing to the ministry’s slow progress in formally adopting and implementing the new curriculum. “On the National Board of Education, there is a strong representation from the churches, that have their own proposal [for sexual education in schools],” de la Rosa explained, alluding to a bill introduced in late 2017 in the Chamber of Deputies, the lower house of Congress.[35]

The bill supported by the Catholic Church, the Bill for Sexual Education based on Values and Responsibility, was introduced by three members of the Chamber of Deputies from Peravia province in October 2017, and would require the Ministry of Education to create a new curriculum for teaching sexuality education.[36] Víctor Masalles, a Catholic bishop from Peravia province, presented the bill to the public.[37] It proposed a new compulsory subject, “Introduction to Human Sexuality,” required for students from seventh grade through the end of high school. The bill proposed an abstinence-only approach, designed to reflect “the purpose of human sexuality as an agent of procreation, intimacy and exclusive commitment between two people of legal age, [and] of the opposite sex,” promote “abstinence from sexual relations,” and emphasize “the emotional consequences of sexual relations at the wrong time.” The bill would guarantee parents the right to choose whether their children participate in the course.[38]

Evaluations of abstinence-only sexual education programs have consistently shown that they are not effective.[39] UNESCO has stated:

While abstinence is an important method of preventing pregnancy, STIs and HIV, CSE [comprehensive sexuality education] recognizes that abstinence is not a permanent condition in the lives of many young people, and that there is diversity in the way young people manage their sexual expression at various ages. Abstinence-only programmes have been found to be ineffective and potentially harmful to young people’s sexual and reproductive health and rights.[40]

In 2013, the Catholic Church filed a lawsuit seeking to halt a public information campaign by Profamilia aimed at women and youth that promoted sexual and reproductive rights, including the right to comprehensive, sexuality education. The campaign stated, “Your sexual and reproductive rights are human rights,” with the slogan, “Know, Act, Demand.” The suit, filed by entities affiliated with the Catholic Church Archdiocese of Santo Domingo, alleged that Profamilia’s campaign encouraged early sexual relationships and abortion.[41] A lower court ruled in favor of Profamilia, stating that the campaign did not violate any fundamental rights,[42] and the church appealed the decision to the Constitutional Court.[43] To date, the Constitutional Court has not ruled on the case.

Right to Information

Adolescent children’s right to information about sexual and reproductive health is guaranteed under international and domestic law. The right to information is set forth in numerous human rights treaties,[44] and includes both a negative obligation for states to refrain from interference with the provision of information by private parties and a positive responsibility to provide complete and accurate information necessary for the protection and promotion of rights, including the right to health.[45]

The Committee on the Rights of the Child, which monitors implementation of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), which the Dominican Republic ratified in 1991, states:

Age-appropriate, comprehensive and inclusive sexual and reproductive health education, based on scientific evidence and human rights standards and developed with adolescents, should be part of the mandatory school curriculum and reach out-of-school adolescents. Attention should be given to gender equality, sexual diversity, sexual and reproductive health rights, responsible parenthood and sexual behaviour and violence prevention, as well as to preventing early pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections.[46]

The Dominican Republic’s national laws also provide for the right to information. Article 29 of the Dominican Republic’s Code for the Protection of the Rights of Children and Adolescents (Law No. 136-03) states:

All boys, girls, and adolescents have the right to be informed and educated about the basic principles of prevention in matters of health, nutrition, early stimulation, physical development, sexual and reproductive health, hygiene, environmental health, and accidents.[47]

Barriers to Health Services

Young people inform us about what they face every day as they try to access sexual and reproductive health services…. They prefer not to go to the health centers to ask for information or contraceptive methods because the medical entities do not protect their privacy. They don’t receive quality services and confidential treatment.[48]

—Cristina Sanchez, executive director of the NGO TÚ, MUJER, February 2018

Access to confidential, non-stigmatizing sexual and reproductive health services is essential to fulfilling the right to health for adolescent girls and young women. Human Rights Watch research suggests some adolescent girls in the Dominican Republic face barriers when seeking family planning or other health services related to their sexual and reproductive health, including being shamed or stigmatized when seeking healthcare, or being denied access to family planning if they were not accompanied by an adult.

A national survey from 2013—the most recent one on this issue—signals how many adolescent girls and young women in the Dominican Republic have an unmet need for contraception. Eleven percent of women and girls ages 15 to 49 who are married or in unions have an unmet need for contraception (meaning they wish to delay or prevent pregnancy but are not using any method of contraception), but adolescent girls and younger women are disproportionately affected. More than one-quarter (27 percent) of adolescent girls and young women ages 15 to 19, and more than one-fifth (21 percent) of women ages 20 to 24 have an unmet need for contraception.[49]

Though Ministry of Health protocols do not require parental consent or third-party authorization for children under 18 to access family planning, some women and girls told Human Rights Watch that they were refused family planning services because they were not accompanied by an adult. Samantha, 18, told Human Rights Watch that first time she went to a clinic for family planning methods, she was told that she needed an adult’s permission. “If you’re a minor…. someone has to sign for you. I had to call my mom who was working.”[50]

Daralis, 24, had a similar experience when she first sought family planning at a hospital in her neighborhood in Santo Domingo: “They didn’t want to sell the [oral contraceptive] pills to me because I was underage,” she said. “I went to buy them [at the hospital], and they told me I had to go with a person over 18 to buy them.” Fortunately, Daralis felt comfortable asking her mother to accompany her. “I came home and went with my mom, but I felt bad. They should have sold them to me.”[51]

“If you are a minor, they don’t give it to you,” explained one health outreach worker, reiterating the common misconception that children under 18 need an adult’s permission to access family planning.[52]

Some adolescent girls and young women told Human Rights Watch they did not seek family planning information or services prior to becoming pregnant because they felt uncomfortable or they did not have adequate information about contraceptive options.[53] Interviewees described how harmful stigma around adolescent sexual activity deters some young people from seeking care in the health system. Members of a group of 14 and 15-year-old students at a school in Santo Domingo explained why some adolescent children may be reluctant to seek sexual health information or services in the public health system: “They’re ashamed. They feel humiliated, afraid to be criticized [for having sex].”[54]

“Young people inform us about what they face every day as they try to access sexual and reproductive health services,” said Cristina Sanchez, executive director of the nongovernmental organization TÚ, MUJER.

They prefer not to go to the health centers to ask for information or contraceptive methods because the medical entities do not protect their privacy. They don’t receive quality services and confidential treatment. For an adolescent, there’s a lot of stigma around revealing private information.

Sanchez said concerns around confidentiality in some communities where she works prevent adolescents from seeking health services.

Adolescents tell us they don’t go [to health centers] even though they have a need [for reproductive health services] because they fear the lack of discretion [on the part of providers]. Their rights are eclipsed by [providers’] indiscretion.[55]

The Committee on the Rights of Child has affirmed that:

All adolescents should have access to free, confidential, adolescent-responsive and non-discriminatory sexual and reproductive health services, information and education, available both online and in person, including on family planning, contraception, including emergency contraception, prevention, care and treatment of sexually transmitted infections, counselling, pre-conception care, maternal health services and menstrual hygiene.

The committee added, “There should be no barriers to commodities, information and counselling on sexual and reproductive health and rights, such as requirements for third-party consent or authorization,” and “particular efforts need to be made to overcome barriers of stigma and fear experienced by, for example, adolescent girls, girls with disabilities and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex adolescents, in gaining access to such services.”[56]

Adolescent Pregnancy

Adolescent pregnancy is a reality that is constantly repeated in neighborhoods, communities, rural areas, and cities of the country, cutting off the future of our adolescents … because they were not physically, emotionally, or intellectually prepared to bring a boy or girl into the world.[57]

—Margarita Cedeño, vice president of the Dominican Republic, February 2019

According to the Pan-American Health Organization (PAHO), the Dominican Republic has the highest adolescent fertility rate of all the countries in Latin America and the Caribbean.[58] A 2013 national demographic and health survey (ENDESA 2013) found that 20.5 percent of girls and young women ages 15 to 19 were pregnant or had given birth.[59] Data from the survey also show that one in four women ages 20 to 49 gave birth before turning 18, and almost half before turning 20.[60]

Adolescent pregnancy and early childbearing carry significant health risks for both the mother and the child. The World Health Organization (WHO) reports that complications from pregnancy and childbirth are the leading cause of death globally among adolescent girls and young women ages 15 to 19. Girls and young women ages 10 to 19 are at elevated risk for a number of serious health conditions associated with pregnancy and childbirth. Babies born to adolescent mothers in low- and middle-income countries are at higher risk of low birthweight, preterm delivery, and severe neonatal conditions.[61]

An obstetrician-gynecologist in Santo Domingo specializing in adolescent health told Human Rights Watch that adolescent pregnancies have a higher risk of hemorrhage because the pelvis may be narrow and underdeveloped. She also explained that adolescent girls often learn they are pregnant later than adult women, because they may not recognize the signs as readily, leading to weeks or months of pregnancy without the recommended nutritional and vitamin intake, such as folic acid, a vitamin that can help prevent certain complications in fetal development.[62]

Human Rights Watch interviewed 10 adolescent girls and young women ages 15 to 19 who had been pregnant at least once, and 20 women who said they had a pregnancy before turning 18. Most of these pregnancies were unplanned, and many were also unwanted.

Some of the young mothers interviewed experienced complications during pregnancy or childbirth. For example, Samantha, 18, had an unplanned and unwanted pregnancy at age 17. She had been using hormonal injections to prevent pregnancy, she said, but they failed for reasons she did not understand. She learned she was five months pregnant after taking a pregnancy test that she was required to submit as part of a job application.

I felt like the world was falling down on me…. I was going crazy, thinking I can’t have a kid. I’m not prepared, I’m not ready economically…. I’d always thought of myself as becoming a successful lawyer or psychologist. I was horrified that my plans would have to be put on hold.

She said she wanted to end the pregnancy but was too frightened to attempt a clandestine abortion. “I was really horrified by the thought of being in trouble or dying [from an unsafe abortion].” She continued the pregnancy against her wishes.

Seven months into the pregnancy, her water broke.

They took me to the emergency room. It was tough. The doctors were telling me not to count on the baby to survive because since my membrane broke, the liquid leaked out, and the uterus closed.

She said some of the health complications she experienced were related to the unplanned—and initially unmonitored—nature of the pregnancy.

I had anemia since I didn’t know I was pregnant. I was prescribed iron because of the anemia, and I had an allergic reaction. My blood pressure went up.[63]

When she delivered her baby prematurely, the doctors informed her that his lungs were underdeveloped, and he had to be transferred to a specialized neonatal facility where he spent several weeks. The baby recovered and was healthy at the time of the interview.

Three of the women and girls we interviewed who gave birth before turning 18 said their babies died.[64] One of them was 16-year-old Lisbeth, who said she first became pregnant at age 14 after the first time she ever had sex. The pregnancy was not planned. Lisbeth said she was distressed when she learned she was pregnant and wanted to try to have a clandestine abortion. “My mom never agreed,” she said. She continued the pregnancy against her wishes, but in the fifth month, doctors informed her that there was a high risk of miscarriage. “They said my uterus was not developed enough.” At six months, she delivered prematurely. The baby only survived for five days.[65]

A few interviewees said health providers subjected them to hostile or judgmental treatment while giving birth during adolescence. Rebeca, a 26-year-old mother of two, first became pregnant at age 16. She said a nurse mistreated her while she gave birth because she was a teenager.

When I was admitted to [the hospital to] get my C-section, the nurse, instead of treating me delicately, she treated me roughly. When I got the C-section, I had to get up, and my mom was there to help me shower. When my mom was helping me, the nurse came in and yelled at her to leave me alone because I was already a woman. She told my mom that I didn’t ask for her help when I was going to have intercourse…. Then I asked for a change of the IV [intravenous therapy], and she ripped it out of my arm. I had an abscess, a wound. She put it in aggressively…. When she was changing the linen on the bed, I was on one side because I felt dizzy. She told me to stand up and stop complaining.[66]

Lisbeth, 16, had a similar experience. She first became pregnant at age 14, and when she was giving birth, she said she called out for her mother because she was in pain. She said a provider at the hospital ridiculed her. “I’d call for my mom because I was crying in the labor. I was yelling, and they said, ‘You didn’t call for your mom when you were doing it [having sex],’” she said. “I felt bad.”[67]

The government of the Dominican Republic has pledged to take steps to reduce the adolescent pregnancy rate. In February 2019, the government launched a national plan to reduce adolescent pregnancy (el Plan Nacional para la Reducción de Embarazos en Adolescentes en la República Dominicana 2019-2023, PREA-RD). The plan involves multiple governmental and nongovernmental actors and aims to address the root causes of adolescent pregnancy and ensure adolescents “receive sex education, stay in school, despite being pregnant or having children, and can access quality health services and contraceptive methods.”[68] Implementing comprehensive sexuality education and addressing barriers that adolescent girls encounter in accessing sexual and reproductive health services will be essential to reducing adolescent pregnancy.

Criminalization of Abortion

Abortion is a phenomenon that’s penalized by law in all its forms, with no exceptions. But we’ve always recognized that unsafe abortion is an important health problem because women have to appeal to clandestine methods to find an answer to their situation [an unwanted pregnancy]. And that creates the phenomenon of unsafe abortion.[69]

—Dr. José Mordán, head of the Department of Family Health, Ministry of Public Health, April 2018

According to 2014 national survey data, less than half of pregnancies among girls and young women under age 20 were planned and wanted at the time they occurred.[70] The Dominican Republic’s total ban on abortion in all circumstances means an adolescent girl facing an unplanned or unwanted pregnancy must continue that pregnancy, even against her wishes, or find a way to get a clandestine abortion, often at great risk to her health and life.

An estimated 25,000 women and girls are treated for complications from miscarriage or abortion in the public health system in the Dominican Republic each year. Complications from abortion or miscarriage account for at least eight percent of maternal deaths, according to the Ministry of Public Health.[71] The criminal code in the Dominican Republic imposes prison sentences of up to two years on women and girls who induce abortions and up to 20 years for medical professionals who provide them.[72] Women’s rights experts told Human Rights Watch that arrests and prosecutions for abortion-related crimes in the Dominican Republic are rare, despite the strict criminal laws. In early 2018, however, a court ordered a 20-year-old woman in San José de Ocoa to serve three months of “preventive detention” while authorities investigated whether she had an illegal abortion.[73] According to advocates, the case was highly unusual in the country.[74]

Laws criminalizing abortion create pervasive fear and drive abortion underground, forcing women and girls to resort to unsafe measures to end unwanted pregnancies. Sexual activity is often highly stigmatized for adolescent girls, so an adolescent girl facing an unwanted pregnancy may be even less likely than an adult woman to speak to anyone about her options, instead confronting her situation in isolation and without adequate support.

Human Rights Watch spoke with several women and girls who tried to end an unwanted pregnancy clandestinely during adolescence.[75] Their accounts reveal the distinct harmful impacts of the criminalization of abortion on adolescent girls.

Maoli, 20, told Human Rights Watch she became pregnant unexpectedly at age 16 and had a clandestine abortion. As an adolescent, she said she felt very afraid, and told only her boyfriend and an older friend about the pregnancy. “I told her [my friend] what was going on, and she told me about a tea used for that [abortion], and I took it…. The next day I started bleeding, and I was in a lot of pain,” she said, rubbing her belly. Her friend eventually took her to a medical provider who attended to her, and the pregnancy ended. Four years later, as she recounted the experience to Human Rights Watch, she said it was still difficult to talk about the experience and the fear she felt:

I don’t like to remember it. I haven’t found another person to confide in about it…. I was afraid…that they [the doctors] would realize [that I had an abortion], that people would know. I was worried that they’d tell my parents.[76]

Some interviewees described unsuccessful attempts to induce abortion. Ana Paula, age 16, became pregnant in 2017, at age 15. She said she tried to terminate the pregnancy:

I prepared a lot of remedies, beverages. But nothing happened. Every day, I took German malt. I would drink one every day.… I prepared it with other things, baking soda. I’d heat it.… I had an expulsion [of tissue from the uterus] after a few days, and I thought it was gone, but then I felt something moving. I went for a second sonogram, and I found out it was girl.

As soon as she left the doctor’s office, she started crying. “All I could think about was the situation I was going through,” she said, explaining that her partner, age 29, did not have a job or a home for them.[77] Carrying an unwanted pregnancy to term is associated with poor mental health outcomes, including depression, anxiety, and low self-esteem.[78]

Some adolescent girls experience complications from unsafe abortion, but may delay seeking care, either due to inadequate information about potentially grave consequences, or a fear of mistreatment by providers or criminal penalties for illegal abortion. Delaying treatment for post-abortion complications can be life-threatening, and lead to long-term consequences for sexual and reproductive health.[79]

Juliana, a 16-year-old mother of two who gave birth for the first time at age 13, told Human Rights Watch about her experience with clandestine abortion. “I have a hard economic situation. Sometimes I don’t even know what we’ll have for dinner.” She became pregnant unexpectedly in early 2018, when her children were ages 3 and 1: “I was terrified. I was going crazy, thinking if I can’t even find food for these two babies [I already have], how will I feed a third?” She took pills and a tea that she believed would induce abortion, and experienced “a lot of pain.” When she went to the doctor, she was told that her cervix had closed, but the abortion was incomplete—meaning the pregnancy had ended, but tissue remained in her uterus, putting her at risk of serious complications. She was referred for additional testing. When she met Human Rights Watch, she had not received further treatment and was still experiencing pain and dizziness, which she believed could be related to the clandestine abortion four weeks prior.[80]

The death of 16-year-old Rosaura Almonte Hernández in 2012 illustrates the devastating impact of the Dominican Republic’s total abortion ban. Rosaura, known as “Esperancita,” was diagnosed with leukemia, but she was initially denied access to chemotherapy because she was pregnant. Her mother, Rosa Hernández, requested access to a therapeutic abortion for Esperancita, and her request was denied. Weeks later, under mounting international pressure, doctors provided Esperancita with chemotherapy, but she died in August 2012. “They let my daughter die,” her mother said.[81] In 2017, Rosa Hernández, with support from the organizations Women’s Link Worldwide and Colectiva Mujer y Salud, filed a petition with the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) seeking justice for her daughter’s death.[82]

Denying adolescent girls and women access to abortion is a form of discrimination and jeopardizes a range of human rights.[83] The UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, which monitors the implementation of the CRC, has noted that “the risk of death and disease during the adolescent years is real, including from preventable causes such as … unsafe abortions” and urged states to “decriminalize abortion to ensure that girls have access to safe abortion and post-abortion services, review legislation with a view to guaranteeing the best interests of pregnant adolescents and ensure that their views are always heard and respected in abortion-related decisions.”[84]

Child Marriage

I got married too young.… I want to continue studying to help my girls keep moving forward.[85]

—Juliana, a 16-year-old mother of two who left school in eighth grade when she married an older man, April 2018

The Dominican Republic has very high rates of child marriage: 36 percent of women ages 20 to 24 were married or in unions before age 18, and 12 percent before age 15.[86] In comparison with the rest of Latin America and the Caribbean, the Dominican Republic has the second-highest percentage of women ages 20 to 24 who were married before 18, after Nicaragua.[87] One in five girls or young women ages 15 to 19 is married or in a union with a man at least 10 years older.[88] Under national laws, the minimum age of marriage is 18, but broad exceptions permit girls 15 and older and boys 16 and older to marry with parental consent, and even younger children to marry with judicial consent granted “for justifiable reasons.”[89]

The stigma against adolescent sexuality, barriers to adolescents accessing contraception, and high rate of adolescent pregnancy in the Dominican Republic, combined with the country’s total ban on abortion, all contribute to some girls feeling compelled to marry young.

A 2017 report by the NGO Plan International analyzed the effects early unions have on the lives and rights of adolescent girls in the Dominican Republic, through in-depth interviews or group discussions with more than 300 people in five provinces. The study identified several factors that contribute to high rates of child marriage in the country, including adolescents’ “little exposure to educational processes that transform the traditional views of gender,” as well as “limited access to friendly services related to sexual and reproductive health; stigma and discrimination in health centres; difficulties to travel to the centres; little privacy and confidentiality in the services,” among others.[90]

Child marriage is deeply harmful. It contributes to girls leaving school, increases the likelihood that they and their children will live in poverty, and heightens risks of domestic violence and marital rape. Girls who give birth before adulthood, and their babies, are at heightened risk of serious complications, including death.[91]

Once girls are married, they are likely to become pregnant and often have multiple children, closely spaced. This was the case for several women and girls interviewed by Human Rights Watch in Dominican Republic, who described how profoundly child marriage had changed their lives.[92]

“I got married at a very young age,” said Larissa, a 22-year-old mother of three in San Cristóbal province. At age 12, she married a 19-year-old man and left school. At 14, she became pregnant for the first time, a pregnancy that was not planned, but which she welcomed. A year later, at age 15, she became pregnant again, when her contraceptive method failed. “It wasn’t in my plans to have another baby,” she said, but explained that she did not think she had any options other than continuing the pregnancy. When she became pregnant for a third time at age 18, she wanted to end the pregnancy. “I didn’t want to have it. I took pills and teas [to try to induce abortion], and I bled various times, but it didn’t work. I had my third baby, and there it is.” When Human Rights Watch met Larissa, she was studying to finish her high school education. “You’re just a child, a 12-year-old girl, and you have to put the pants on,” alluding to the trials of early parenthood.[93]

Madelyn, 28, said she married at age 15. “I got married at 15, really early. I said I wasn’t going to get pregnant. I didn’t want to get pregnant. I wanted to finish high school. A lot of people told me, ‘Once you have kids, studying gets complicated.’” She had an unplanned pregnancy at 18 after her contraceptive method failed. Though she was able to finish high school, she was devastated. “I wanted to continue studying… I cried a lot at the beginning, a lot a lot,” she said, though she later accepted the pregnancy.[94]

Isabella, 22, told Human Rights Watch that she left school after seventh grade to get married: “I got married, and I decided to leave [school].” She became pregnant at 17 and gave birth. When her baby was six months old, she tried to access contraceptive pills at a local public hospital, but they were not available. She became pregnant again, and not yet 20, she gave birth again. Her second baby died. When she met Human Rights Watch, she was studying to finish eighth grade while caring for her son.[95]

The UN Committee on the Rights of the Child has called for a minimum age of 18 for marriage.[96] Commenting specifically on the Dominican Republic, the committee expressed concern that “although the minimum age for marriage is set at 18 for both girls and boys, child marriage, especially of girls, remains highly prevalent” in the Dominican Republic, and said it was “particularly concerned that 15-year-old girls and 16-year-old boys can enter marriage with the written consent of their parents and that even younger children can be allowed to marry with the authorization of a judge.”[97]

Barriers to Education Linked to Adolescent Pregnancy and Motherhood

They don’t accept pregnant girls [at school] during the day. Only at night or during the weekend.[98]

—Ana Paula, a 16-year-old mother who was asked to transfer to night school while she was pregnant, April 2018

The right to education is guaranteed under article 63 of the Constitution of the Dominican Republic.[99] National laws provide for eight years of compulsory basic education and one year of pre-school, but secondary education is not free or compulsory.[100] The Code for the Protection of the Rights of Children and Adolescents (Law No. 136-03) reaffirms that all boys, girls, and adolescents have the right to education, and specifically prohibits any “sanctions, removal or expulsion, or any discriminatory treatment” due to an adolescent girl’s pregnancy.[101]

Despite these legal protections, research by Human Rights Watch and other NGOs suggests pregnant adolescent girls and young mothers in Dominican Republic encounter barriers to education.[102]

Several girls and young women who had been pregnant during adolescence told Human Rights Watch they faced discrimination or discriminatory attitudes from teachers or school administrators. These students often left school during pregnancy, or after giving birth. Some never returned, and some missed several years before continuing their studies.

Ana Paula, 16, said she transferred to night school when she became pregnant in eighth grade. She said pregnant girls were not permitted to continue taking classes on a regular schedule in her school. “They don’t accept pregnant girls during the day. Only at night or during the weekend.” When asked how she felt about changing her schedule, she said, “I didn’t feel good. I didn’t want to attend school at night.”[103] Lisbeth, a 16-year-old girl from the same neighborhood had a similar experience. “I got pregnant, and I had to change to night classes because of the pregnancy.” She was five months pregnant when she spoke with Human Rights Watch, and she said she had dropped out of school, though she dreamed of becoming a lawyer in the future.

Karen, an 18-year-old with an 8-month old baby, said:

After everyone knew about the pregnancy, I stopped going [to school]. I went to for my final exams [of the school year], and I never went back. Because it wasn’t the same. In the classroom, everyone would stare at me. They disrespected me. The social sciences teacher was the worst. He told me, ‘You should go in another classroom because all the students are going to start to get pregnant and think it’s a joke.’ I felt bad at that time. I was an excellent student. But my scores dropped.

She said other students at her school had also left school after becoming pregnant.[104]

Aury, 24, became pregnant at 17 when her contraceptive method failed. “I was three months away from finishing high school.” At the time she was attending a private school, and the director asked her to transfer to Sunday classes at a public institution. “You couldn’t be pregnant in school. The director told me.” Aury convinced the director to allow her to attend school one day a week to take notes, and she managed to complete high school that way. But she was deeply depressed. “I hadn’t planned any of it. I wanted to stay in school.”[105]

Other interviewees left school after a pregnancy because they lacked support to care for their children. Lucely, 18, gave birth at age 16 and said, “I had to leave school because my mom doesn’t live here [nearby], and there’s no one to look after my daughter.”[106]

Authorities in the Dominican Republic should take additional steps to ensure adolescent girls are able to stay in school during pregnancy and motherhood, including by enforcing the ban on pregnancy-based discrimination in schools; monitoring girls’ attendance and re-entry and following up when girls drop out; providing special accommodations for young mothers at school, for instance, time and space for breast-feeding and time off when babies are ill or to attend health clinics; establishing free or affordable childcare facilities close to or within schools; and providing counselling and support referrals for pregnant adolescent girls and young mothers.

Acknowledgments

This report was researched and written by Margaret Wurth, senior researcher in the Children’s Rights Division at Human Rights Watch.

Heather Barr, acting co-director of the Women’s Rights Division, edited the report.

Zama Neff, executive director of the Children’s Rights Division; Amanda Klasing, acting co-director of the Women’s Rights Division; and Juan Pappier, Americas researcher, reviewed and commented on the report. Chris Albin-Lackey, senior legal advisor, provided legal review, and Tom Porteous, deputy program director, and Danielle Haas, senior editor, provided program review.

Design and production assistance were provided by Erika Nguyen, coordinator in the Women’s Rights Division; Fitzroy Hepkins, administrative manager; and Jose Martinez, senior administration coordinator. Gabriela Haymes translated this report into Spanish, and Claudia Núñez, Spanish web editor at Human Rights Watch, vetted the Spanish translation.

We are deeply grateful to Yaneris González Gómez, who showed extraordinary compassion and dedication while working with Human Rights Watch as an interpreter and fixer for this project.

Human Rights Watch benefitted from the time and insights offered by many Dominican and international nongovernmental organizations, activists, and experts. In particular, we would like to thank the following individuals and groups for their support and collaboration: Colectiva Mujer y Salud; CE-MUJER; Centro de Investigación para La Acción Femenina (CIPAF); Centro de Estudios de Género (CEG-INTEC); Círculo de Mujeres con Discapacidad, Inc. (CIMUDIS); Comunidad de Lesbianas Inclusivas Dominicanas (COLESDOM); Comité de América Latina y el Caribe para la Defensa de los Derechos de las Mujeres – República Dominicana (CLADEM-RD); Confederación Nacional de Mujeres Campesinas (CONAMUCA); Coalición por los Derechos y la Vida de las Mujeres; Carmela Cordero; Foro Feminista; Instituto de Género y Familia de la Universidad Autónoma de Santo Domingo (UASD); Junta de Mujeres Mamá Tingó (JMMT); Movimiento de Mujeres Dominico Haitianas (MUDHA); Movimiento de Mujeres Unidas (MODEMU); Núcleo de Apoyo a la Mujer (NAM); Paola Pelletier; Sergia Galván; and TÚ, MUJER.

We also wish to thank American Jewish World Service (AJWS); Center for Reproductive Rights (CRR); Planned Parenthood Federation of America (PPFA); Oxfam – Dominican Republic; Plan International República Dominicana; Women’s Equality Center (WEC); and Women’s Link Worldwide for input and guidance on our project design.

Most importantly, we are deeply grateful to those who shared their stories with us.

[1] Human Rights Watch interview with Lucely, 18, San Cristóbal province, Dominican Republic, April 16, 2018.

[2] Ministerio de Salud Pública (MSP), Centro de Estudios Sociales y Demográficos (CESDEM), and ICF International, “Encuesta Demográfica y de Salud (ENDESA) 2013,” October 2014, https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR292/FR292.pdf (accessed July 10, 2018), p. 101.

[3] Ibid., p. 109.

[4] For a detailed description of Human Rights Watch’s methodology, see Human Rights Watch, “It’s Your Decision, It’s Your Life”: The Total Criminalization of Abortion in the Dominican Republic, November 2018, https://www.hrw.org/report/2018/11/19/its-your-decision-its-your-life/total-criminalization-abortion-dominican-republic.

[5] Human Rights Watch interview with Minerva Pérez, directora general, Dirección de Orientación y Psicología, and Bethania Leger, técnica docente nacional, Ministerio de Educación (MINERD), Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, October 1, 2018.

[6] See, for example, United Nations Human Rights Committee (HRC), “Concluding observations on Dominican Republic,” CCPR/C/DOM/CO/6, November 27, 2017, paras. 15-16, expressing concern with “the continuingly high rates of child and teenage pregnancy, owing to… the lack of reproductive health services and to inappropriate and insufficient information,” and urging the country to “ensure unimpeded access to sexual and reproductive health services and education for men, women and adolescents nationwide”; Committee on Economic Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR), “Concluding observations on the Dominican Republic,” E/C.12/DOM/CO/4, October 21, 2016, paras. 64-65, urging the Dominican Republic to “incorporate comprehensive age-appropriate lessons on human rights, gender equality and sexual and reproductive health into primary and secondary curricula.” See also, UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, “Concluding observations on the combined sixth and seventh periodic reports of the Dominican Republic,” CEDAW/C/DOM/CO/6-7, July 30, 2013, para. 33(d); United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC), “Concluding observations on the combined third to fifth periodic reports of the Dominican Republic,” CRC/C/DOM/CO/3-5, March 5, 2015, para. 52.

[7] United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), Análisis de la Situación Poblacional: República Dominicana 2017, (Santo Domingo: UNFPA, 2017), p. 52.

[8] For example, Human Rights Watch interviews with Cinthya Velasco, executive director, Colectiva Mujer y Salud, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, April 12, 2018; and Myrna Flores Chang, manager of the Gender and Rights Program, Fernando de la Rosa, head of education, and Leopoldina Cairo, manager of programming and evaluation, Profamilia, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, February 20, 2018.

[9] Human Rights Watch interview with Minerva Pérez, directora general, Dirección de Orientación y Psicología, and Bethania Leger, técnica docente nacional, Ministerio de Educación (MINERD), Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, October 1, 2018; MINERD, “MINERD trabaja para incluir la educación sexual a su currículo,” July 17, 2015, http://www.ministeriodeeducacion.gob.do/comunicaciones/noticias/minerd-trabaja-para-incluir-la-educacion-sexual-a-su-curriculo (accessed September 11, 2018).

[10] Elsa Alcántara, UNFPA, “Educación sexual en la escuela como base para la equidad social y de género (Línea base sobre la Educación Sexual y VBG en las escuelas del Sector Público),” August 2012, https://dominicanrepublic.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/EstadodelaeducsexualyVBGenlasescuelas310812.pdf (accessed September 11, 2018), p. 26.

[11] Human Rights Watch interview with Minerva Pérez and Bethania Leger, , October 1, 2018.

[12] MINERD, “MINERD trabaja para incluir la educación sexual a su currículo.”

[13] Human Rights Watch interview with Myrna Flores Chang, Fernando de la Rosa, and Leopoldina Cairo, February 20, 2018.

[14] Ley General de Educación, Secretaría de Educación Pública, signed into law July 13, 1993, ch. II, art. 76.

[15] MINERD, Orden Departamental 33-2019, May 22, 2019, http://www.ministeriodeeducacion.gob.do/media/banners/095b18af7150607375ca8f9942497846f4ace559orden-departamental-no-33-2019-2pdf.pdf (accessed June 4, 2019).

[16] Constitución de la República Dominicana, Government of the Dominican Republic, art. 39(4).

[17] For example, “Organizaciones respaldan orden departamental de Educación sobre política de género,” May 29, 2019, El Día, https://eldia.com.do/organizaciones-respaldan-orden-departamental-de-educacion-sobre-politica-de-genero/ (accessed June 4, 2019); Lisania Batista, “Ordenanza Ministerio Educación divide a la sociedad sobre igualdad de género,” Diario Libre, https://www.diariolibre.com/actualidad/educacion/ordenanza-ministerio-educacion-divide-a-la-sociedad-sobre-igualdad-de-genero-AC12890541 (accessed June 4, 2019).

[18] United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), International technical guidance

on sexuality education: An evidence-informed approach, revised edition, (New York: UNFPA, 2018), http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2018/international-technical-guidance-on-sexuality-education (accessed September 12, 2018), pp. 16-20.

[19] Human Rights Watch interview with Ana Paula, 16, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, April 15, 2018.

[20] Human Rights Watch interview with Adelyn, 20, Santiago de los Caballeros, Dominican Republic, April 17, 2018.

[21] Human Rights Watch interview with Samantha, 18, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, April 14, 2018.

[22] Human Rights Watch interview with Karen, 18, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, April 14, 2018.

[23] UNESCO, International technical guidance on sexuality education: An evidence-informed approach, revised edition, pp. 16-20.

[24] Human Rights Watch interview with Rayneli, 15, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, April 15, 2018.

[25] Human Rights Watch interview with Lisbeth, 16, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, April 15, 2018.

[26] Human Rights Watch interview with Samantha, April 14, 2018.

[27] Human Rights Watch interview with Karen, April 14, 2018.

[28] Human Rights Watch interview with school principal, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, April 19, 2018.

[29] Human Rights Watch focus group discussion with 11 children, ages 14 and 15, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, April 19, 2018.

[30] Human Rights Watch interview with Myrna Flores Chang, Fernando de la Rosa, and Leopoldina Cairo February 20, 2018.

[31] Human Rights Watch interview with Emily, 18, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, February 17, 2018.

[32] Human Rights Watch interview with Alicia, 17, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, April 15, 2018.

[33] Human Rights Watch interview with Diego, 17, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, February 17, 2018.

[34] Human Rights Watch interview with Minerva Pérez and Bethania Leger, October 1, 2018.

[35] Human Rights Watch interview with Myrna Flores Chang, Fernando de la Rosa, and Leopoldina Cairo, February 20, 2018.

[36] Proyecto de Ley de Educación Sexual Basado en Valores y Responsabilidad, November 8, 2017, http://sil.camaradediputados.gob.do:8095/ReportesGenerales/VerDocumento2?documentoId=67487 (accessed September 12, 2018).

[37] See, for example, Carlos Reyes, “Iglesia católica propone crear asignatura sobre sexualidad,” Diario Libre, November 1, 2017, https://www.diariolibre.com/noticias/educacion/iglesia-catolica-propone-crear-asignatura-sobre-sexualidad-GL8490239 (accessed September 12, 2018).

[38] Proyecto de Ley de Educación Sexual Basado en Valores y Responsabilidad.

[39] UNESCO, International technical guidance on sexuality education: An evidence-informed approach, revised edition,), pp. 18, 29.

[40] Ibid., p. 18.

[41] For example, “Profamilia dice continuará campaña sobre derechos sexuales ante sometimiento,” El Caribe, May 9, 2013, https://www.elcaribe.com.do/2013/05/09/sin-categoria/profamilia-dice-continuara-campana-sobre-derechos-sexuales-ante-sometimiento/ (accessed September 12, 2018).

[42] “Fallan en favor de ProFamilia en campaña de educación sexual,” Diario Libre, May 21, 2013, https://www.diariolibre.com/noticias/fallan-en-favor-de-profamilia-en-campaa-de-educacin-sexual-ADDL384532 (accessed September 12, 2018).

[43] Julia Ramírez, “Conflicto entre la Iglesia católica y Profamilia va al Constitucional,” El Caribe, June 4, 2013, https://www.elcaribe.com.do/2013/06/04/sin-categoria/conflicto-entre-iglesia-catolica-profamilia-constitucional/ (accessed September 12, 2018).

[44] International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), adopted December 16, 1966, G.A. Res. 2200A (XXI), 21 U.N. GAOR Supp. (No. 16) at 52, U.N. Doc. A/6316 (1966), 999 U.N.T.S. 171, entered into force March 23, 1976, ratified by the Dominican Republic on January 4, 1978, art. 19(2); American Convention on Human Rights (“Pact of San José, Costa Rica”), adopted November 22, 1969, O.A.S. Treaty Series No. 36, 1144 U.N.T.S. 123, entered into force July 18, 1978, reprinted in Basic Documents Pertaining to Human Rights in the Inter-American System, OEA/Ser.L.V/II.82 doc.6 rev.1 at 25 (1992)., art. 13(1). See also Claude-Reyes et al. v. Chile, Inter-American Court, Inter-Am Ct.H.R., Series C. No. 151, Judgment, September 19, 2006, para. 264.

[45] See International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), adopted December 16, 1966, G.A. Res. 2200A (XXI), 21 U.N. GAOR Supp. (No. 16) at 49, U.N. Doc. A/6316 (1966), 993 U.N.T.S. 3, entered into force January 3, 1976., art. 2(2). See also CESCR General Comment No. 14 on the right to the highest attainable standard of health, UN Doc. E/C.12/2000/4 (2000); and CESCR General Comment No. 22 on the right to sexual and reproductive health, UN Doc. E/C.12/GC/22 (2016).

[46] CRC, General Comment No. 20 on the implementation of the rights of the child during adolescence, UN Doc. CRC/C/GC/20 (2016), para. 61.

[47] Ley 136-03, Código para la protección de los derechos de los Niños, Niñas y Adolescentes, Government of the Dominican Republic, 2003, art. 29.

[48] Human Rights Watch interview with Cristina Sanchez, executive director, TÚ, MUJER, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, February 13, 2018.

[49] Unmet need for contraception is defined by the United Nations as a percentage of married or in-union women of reproductive age who are fertile and wish to delay or prevent pregnancy, yet they are not using any method of contraception. See, for example, United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, “World Contraceptive Use 2018,” POP/DB/CP/Rev2018, http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/dataset/contraception/wcu2018.shtml (accessed July 10, 2018); MSP, CESDEM, IFC International, “ENDESA 2013,”), pp. 122-123.

[50] Human Rights Watch interview with Samantha, April 14, 2018.

[51] Human Rights Watch interview with Daralis, 24, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, April 15, 2018.

[52] Human Rights Watch interview with three health outreach workers, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, February 19, 2018.

[53] Human Rights Watch interview with Maoli, 20, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, April 13, 2018; Karen, April 20, 2018; Adelyn, April 17, 2018.

[54] Human Rights Watch focus group discussion with 11 children, ages 14 and 15, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, April 19, 2018.

[55] Human Rights Watch interview with Cristina Sanchez, February 13, 2018.

[56] CRC, General Comment No. 20 on the implementation of the rights of the child during adolescence, para. 60.

[57] Vicepresidencia de la República Dominicana, “Vicepresidenta presenta Plan Nacional para la Reducción de Embarazos en Adolescentes,” February 12, 2019, https://vicepresidencia.gob.do/vicerdo/2019/02/12/vicepresidenta-presenta-plan-nacional-para-la-reduccion-de-embarazos-en-adolescentes/ (accessed March 29, 2019).

[58] The adolescent fertility rate, defined as the number of pregnancies per 1,000 girls and young women ages 15 to 19, was 96.1 in the Dominican Republic in 2017. Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), Health Information Platform for the Americas (PLISA), “Core Indicators, Indicator Profiles, Adolescent Fertility Rate (Births/1,000 women aged 15-19),” 2017, http://www.paho.org/data/index.php/en/indicators/visualization.html (accessed July 16, 2018).

[59] MSP, CESDEM, IFC International, “ENDESA 2013,” p. 101.

[60] UNFPA, “Presentan mapa sobre situación embarazo en adolescentes,” March 1, 2017, https://dominicanrepublic.unfpa.org/es/news/presentan-mapa-sobre-situaci%C3%B3n-embarazo-en-adolescentes (accessed September 24, 2018).

[61] World Health Organization (WHO), “Adolescent Pregnancy,” February 23, 2018, http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-pregnancy (accessed July 16, 2018).

[62] Human Rights Watch interview with obstetrician-gynecologist, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, April 19, 2018.

[63] Human Rights Watch interview with Samantha, April 14, 2018.

[64] Human Rights Watch interviews with Lisbeth, April 15, 2018; Isabella, 22, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, April 14, 2018; Aury, 24, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, April 14, 2018.

[65] Human Rights Watch interview with Lisbeth, April 15, 2018.

[66] Human Rights Watch interview with Rebeca, 26, Villa Altagracia, Dominican Republic, February 16, 2018.

[67] Human Rights Watch interview with Lisbeth, April 15, 2018.

[68] Vicepresidencia de la República Dominicana, “Vicepresidenta presenta Plan Nacional para la Reducción de Embarazos en Adolescentes.”

[69] Human Rights Watch interview with Dr. José Mordán, head of the Department of Family Health at the Ministry of Public Health, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, April 20, 2018.

[70] MSP, CESDEM, IFC International, “ENDESA 2013,” p. 109.

[71] Email from Dr. José Mordán, head of the Department of Family Health at the Ministry of Public Health, to Human Rights Watch, November 3, 2018.

[72] Penal Code of the Dominican Republic, 1884, art. 317.

[73] For example, Human Rights Watch interviews with Katherine Jaime and Orlidy Inoa, Comité de América Latina y el Caribe para la Defensa de los Derechos de las Mujeres – República Dominicana (CLADEM-RD), Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, February 12, 2018; Zobeyda Cepeda, Oxfam, Santo Domingo, February 14, 2018; Myrna Flores Chang, Fernando de la Rosa, and Leopoldina Cairo, February 20, 2018; Dr. José De Lancer, , April 13, 2018.

[74] Human Rights Watch interviews with Cinthya Velasco, April 12, 2018; Myrna Flores Chang, Fernando de la Rosa, and Leopoldina Cairo, , February 20, 2018.

[75] Human Rights Watch interviews with Juliana, 16, Santiago de los Caballeros, Dominican Republic, April 18, 2018; Maoli, April 13, 2018; Ana Paula, 16, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, April 15, 2018; Lucely, 18, San Cristóbal province, Dominican Republic, April 16, 2018; with Larissa, 22, San Cristóbal province, Dominican Republic, February 16, 2018; Aury, 24, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, April 14, 2018; Carmen, 33, Santiago de los Caballeros, Dominican Republic, April 18, 2018; Dayelin, April 18, 2018; Gabriela, 22, San Cristóbal province, Dominican Republic, February 16, 2018. For a detailed discussion of the impacts of the criminalization of abortion in the Dominican Republic, see Human Rights Watch, “It’s Your Decision, It’s Your Life”: The Total Criminalization of Abortion in the Dominican Republic, November 2018, https://www.hrw.org/report/2018/11/19/its-your-decision-its-your-life/total-criminalization-abortion-dominican-republic.

[76] Human Rights Watch interview with Maoli, April 13, 2018.

[77] Human Rights Watch interview with Ana Paula, April 15, 2018.

[78] See, for example, Pamela Herd, Jenny Higgins, Kamil Sicinski, and Irina Merkurieva, “The Implications of Unintended Pregnancies for Mental Health in Later Life,” American Journal of Public Health, vol. 106, no. 3 (2016), pp. 421–429; M. Antonia Biggs, Ushma D. Upadhyay, Charles E. McCulloch, et al., “Women’s Mental Health and Well-being 5 Years After Receiving or Being Denied an Abortion: A Prospective, Longitudinal Cohort Study,” JAMA Psychiatry, vol. 74, no. 2 (2017), pp. 169-178.