Summary

“Everyone knows there is enormous suffering for talibé children in certain daaras. It’s time for the government to take concrete action to protect talibé children and end the abuse.”

– Mamadou Wane, president, Platform for the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights (PPDH), Senegal, June 2018

“If abuse occurs in the daara, talibés often prefer to stay in the street rather than return to a daara where they are always beaten, mistreated, with no freedom, no rights… or it’s the marabout who sends them out begging and exploits them… I always say, and I maintain this position: these children don’t belong in the streets.”

– Social worker, Mbour, Senegal, December 2018

For over a decade, Senegalese and international journalists, human rights advocates, and child protection experts have documented and denounced the ongoing exploitation, abuse and neglect of children living in many of Senegal’s traditional Quranic schools, or daaras. Thousands of these children, known as talibés, continue to live in conditions of extreme squalor, deprived of adequate food and medical care.

Human Rights Watch research indicates that an estimated 100,000 talibé children living in residential daaras across Senegal are forced by hundreds of Quranic teachers, or marabouts, to beg daily for money, food, rice or sugar. Some force the children to beg for set quotas of money, enforced by often-severe beatings. This is in contrast to the many other Quranic teachers who respect the rights of the children in their care.

President Macky Sall, re-elected in February 2019 to a second term, has since 2016 promised to end child begging and “remove children from the streets,” reiterating in May 2019 his intention to “definitively resolve the problem of children in the street.” However, by late 2019, this rhetoric had not yet been accompanied by consistent, decisive and far-reaching action to protect talibés from abuse and exploitation across the country and deter further violations.

This report examines Senegal’s policy, programmatic and judicial efforts from 2017 to 2019 to protect talibé children from abuse, neglect and trafficking, bring those responsible to justice, and improve conditions in daaras. It makes recommendations on steps the new government should take to better protect talibé children and bring about lasting change.

The report is based on 10 weeks of field research in Senegal between June 2018 and January 2019, phone interviews between May 2018 and November 2019, and information drawn from credible secondary sources, including court documents and media reports. Human Rights Watch traveled to the cities of Dakar, Saint-Louis, Diourbel, Touba, Mbacke, Louga and Coki and interviewed more than 150 people over the course of this research, which builds on previous research conducted since 2009.

Abuse, Neglect, Trafficking

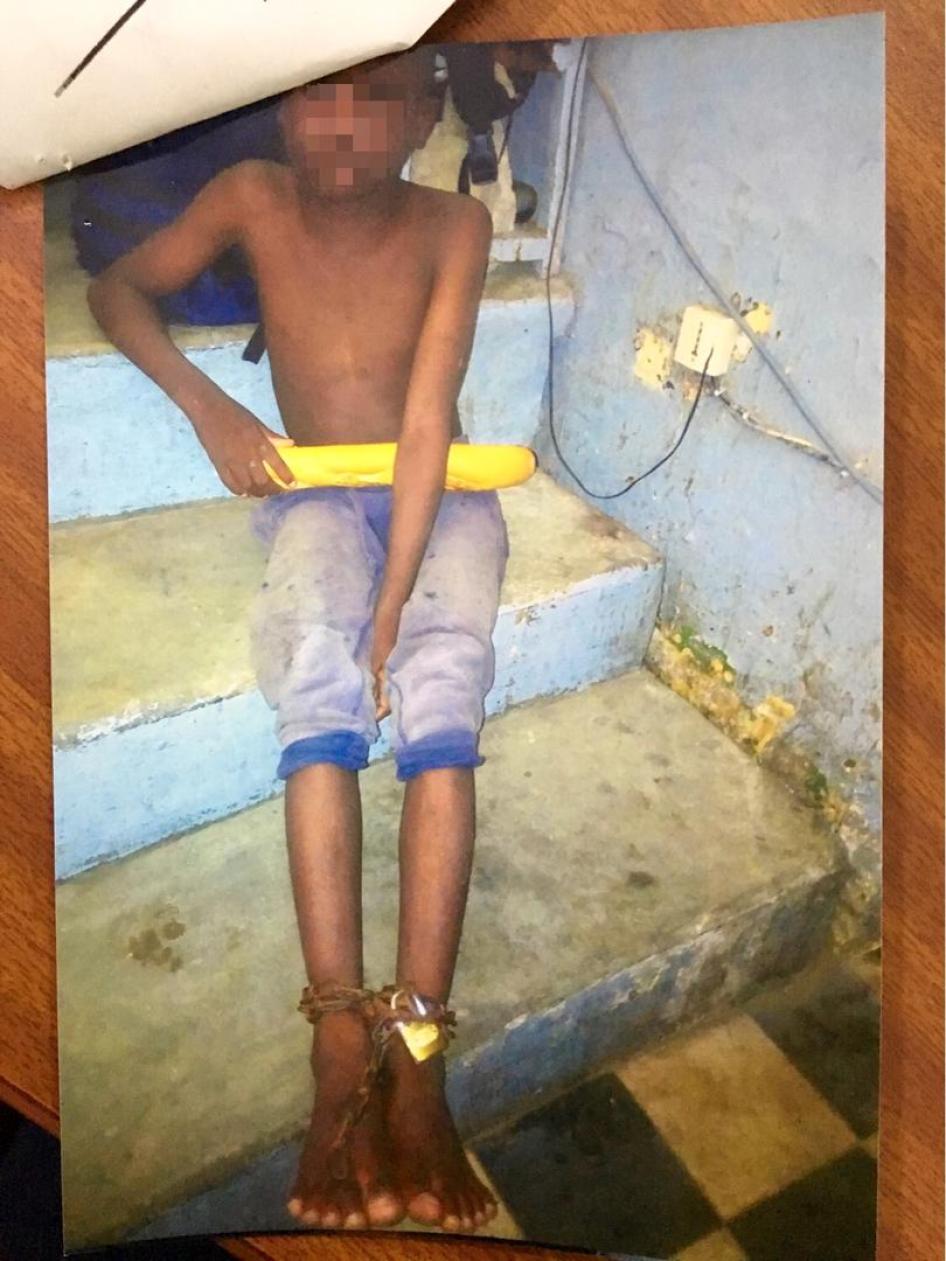

Human Rights Watch has reported on serious abuses committed against talibé children since 2009. A June 2019 report documented dozens of abuses in 2017 and 2018 allegedly committed by Quranic teachers or their assistants in eight of Senegal’s 14 administrative regions. These included 16 talibé deaths due to abuse or neglect, as well as dozens of cases of beatings, sexual abuse, and children chained or imprisoned in daaras.

The report also documented numerous forms of neglect and endangerment threatening talibés’ health and safety. Long hours on the streets begging put talibés at risk for car accidents and assault. Due to the lack of food and medical care at many daaras, talibés often suffer from malnutrition or untreated illnesses, in some cases leading to child deaths. Others have been injured or killed in daara fires when the marabout was absent.

Finally, the report documented forced begging, trafficking, and problems related to talibé migration, including illicit transport of groups of talibés across regions or country borders; cases of talibés abandoned by their marabouts or parents; and the hundreds of children who end up in the streets or in shelters each year after fleeing abusive daaras.

Government Efforts Fall Short

While the Senegalese government made efforts to expand its child protection interventions in recent years, inconsistencies in programming and the limited reach of justice have failed to protect talibés from abuse and deter forced child begging on a wider scale.

Between 2017 and 2019, authorities launched the second phase of the program to “remove children from the streets” in Dakar and announced plans for a third phase; provided social assistance to some daaras and talibés; and constructed several public “modern daaras.” The long-awaited law on the status of daaras, first drafted in 2013 and subject to years of revision, was finally validated in June 2018 by the Council of Ministers; but at time of writing, it had not been brought to a vote before the National Assembly.

However, a number of other challenges have undercut efforts to fight child begging, regulate daaras, protect talibé children from abuse, and ensure justice.

Efforts to Fight Child Begging and Regulate Daaras

The government attempted to address child begging in recent years by sending police and social workers into the streets to “remove” children. However, these initiatives remained superficial and limited to Dakar, with several shortcomings – notably the failure to address root causes or incorporate deterrence by way of prosecutions – preventing widespread or durable impact.

The first phase of one of these initiatives, a program known as the “removal of children from the streets” (in French, le retrait des enfants de la rue, or the retrait), “removed” over 1,500 children – including around 1,000 talibés – from the streets of Dakar from June 2016 to early 2017. A July 2017 Human Rights Watch report identified a number of serious problems with the program, including the failure to investigate or arrest any of the Quranic teachers responsible for forcing the children to beg, and the return of some 1,000 talibés to those same teachers.

Subsequently, a November 2017 anti-trafficking police operation in partnership with Interpol (separate from the retrait program) “rescued” over 50 children – mostly talibés – from the streets in Dakar, incorporating the missing step: investigations, arrests and prosecutions. Unfortunately, sources from shelters where the children were placed told Human Rights Watch that some of these children were returned later in 2018 to their Quranic teachers, several of whom had only served a few months in prison.

In early 2018, the government launched the revamped “second phase” of the retrait program, picking up over 300 talibés between April and June 2018. An important change was implemented: children were returned only to their families, not to daaras. However, the justice element was again left out. “We [had] no instructions to arrest or refer the marabouts for prosecution. This time, we [were] focusing on the removal of the children,” a police commissioner involved with the program told Human Rights Watch in August 2018.

By pulling children off the street without investigating or ensuring serious consequences for those who forced them to beg, authorities are failing to attack the root of the problem and deter further abuse. Additionally, the retrait program’s narrow focus on Dakar has not impacted the tens of thousands of talibés forced to beg in other regions.

“There are some government actions to applaud. But this program to ‘remove children from the street’ is like scooping a cup of water from the ocean,” said Yahya Sidibe, president of the Senegalese association SOS Talibés. “Has it really made a difference? I still see children in the streets. I haven’t noticed any decrease. The phenomenon is prevalent across the whole country.”

Where any decrease in child begging has occurred, it appears limited to a few municipalities – such as Medina and Gueule Tapée-Fasse-Colobane, in Dakar – where committed mayors banned begging and worked with their communities to enforce the rule. These mayors, supported by international partners, also initiated inspections of local daaras, shutting down several that did not comply with the begging ban or posed health and safety risks. Unfortunately, few other local officials have used their authority to regulate daaras in their administrative areas.

Under-resourced Child Protection Services

The lack of adequate child protection services to remove children from abusive situations, provide care and shelter, and report cases of child abuse to the police or public prosecutor also contributes to the high numbers of children on the streets and subject to ongoing abuses in daaras. This report documents how child protection services in Senegal are critically under-resourced and often overwhelmed by talibé runaways or abuse victims.

No special police units for child protection exist outside of Dakar, and Departmental Child Protection Committees struggle with limited resources. Regional offices of “Non-Institutional Educational Action” (Action éducative en milieu ouvert, AEMO) – a social services and legal assistance agency under the Justice Ministry – are often staffed by just three or four people, some with no working vehicle and limited resources to reach children where abuses happen. Existing children’s shelters have limited capacity, and only three of Senegal’s 14 regions have state-run emergency children’s shelters. While non-governmental centers attempt to fill the gap in various regions, there are nowhere near enough facilities to meet the need.

As a result, social workers in some regions were forced to shelter talibé runaways or abuse victims in offices, daaras, or private orphanages while their parents were traced. Furthermore, social workers reported that they often felt constrained to prioritize the “most urgent” cases.

Justice: Advances and Blockages

Strong domestic laws in Senegal ban child abuse and willful neglect, sexual abuse of children, wrongful imprisonment or sequestration, endangerment, and human trafficking (including the “exploitation of begging” and “migrant smuggling”). However, these laws are rarely enforced against Quranic teachers, squandering potential for deterrence. While more cases of abuse and exploitation by Quranic teachers were adjudicated in 2017, 2018 and 2019 than in prior years, the total remained small in proportion to the widespread nature of past and current abuses, and a number of obstacles to justice persisted.

The barriers to justice explored in this report include social workers failing to report cases of talibé child abuse or exploitation, police failing to investigate or inform the judiciary in some cases, inadequate legal aid services for child victims, family members failing to file official complaints against Quranic teachers, and some public prosecutors failing to launch such investigations of their own initiative. The juvenile-court-led judicial process assigning temporary child custody to children's shelters is one example of an often-missed opportunity by the prosecutor’s office to open an investigation. Human Rights Watch found that even when judicial investigations are opened, prosecutors and judges are often subject to pressure from religious leaders, the community, or politicians to drop cases, reduce charges, or provide more lenient sentences.

That said, the past decade has seen a slow but positive national trend toward increased enforcement of the law against abusive Quranic teachers. Human Rights Watch has analyzed information showing that at least at least 32 judicial investigations into alleged abuses by Quranic teachers or their assistants were opened between 2017 and 2019 in nine administrative regions, leading to at least 29 prosecutions and 25 convictions during that period for forced begging, abuse, or children’s deaths. The number of prosecutions and convictions during those years was likely higher than those documented in this report, as social workers and judicial officials in several regions mentioned additional cases which Human Rights Watch was unable to verify in detail.

Police and judicial enforcement of the 2005 anti-trafficking law increased in recent years, with at least nine Quranic teachers arrested on charges related to child smuggling or “exploitation of begging” between 2017 and 2019 in four regions. Eight were prosecuted and convicted; however, penalties were reduced by judges to fines or a few months in prison.

Members of the judiciary dropped or reduced charges or sentences against Quranic teachers or their assistants in at least 17 cases between 2017 and 2019. According to sources in the judiciary and Justice Ministry, this was often the result of public pressure linked to the social influence of Quranic teachers and religious leaders.

***

On November 19, 2019, Human Rights Watch, in a letter to the Senegalese ambassador to the US, shared the main findings of this report and sought information on government’s efforts to protect talibé children. On December 3, 2019, the Ministry of National Education responded, highlighting several projects aimed at improving standards in daaras, including the “Daara Modernization Support Project” (Projet d’appui à la modernisation des daara, PAMOD), the “Project to Support the Protection of Children in Education” (Projet de Renforcement de l’Appui à la Protection des enfants dans l’Éducation, RAP), and others. The letter is included as an appendix to this report.

The Roadmap: Justice, Policy and Programming

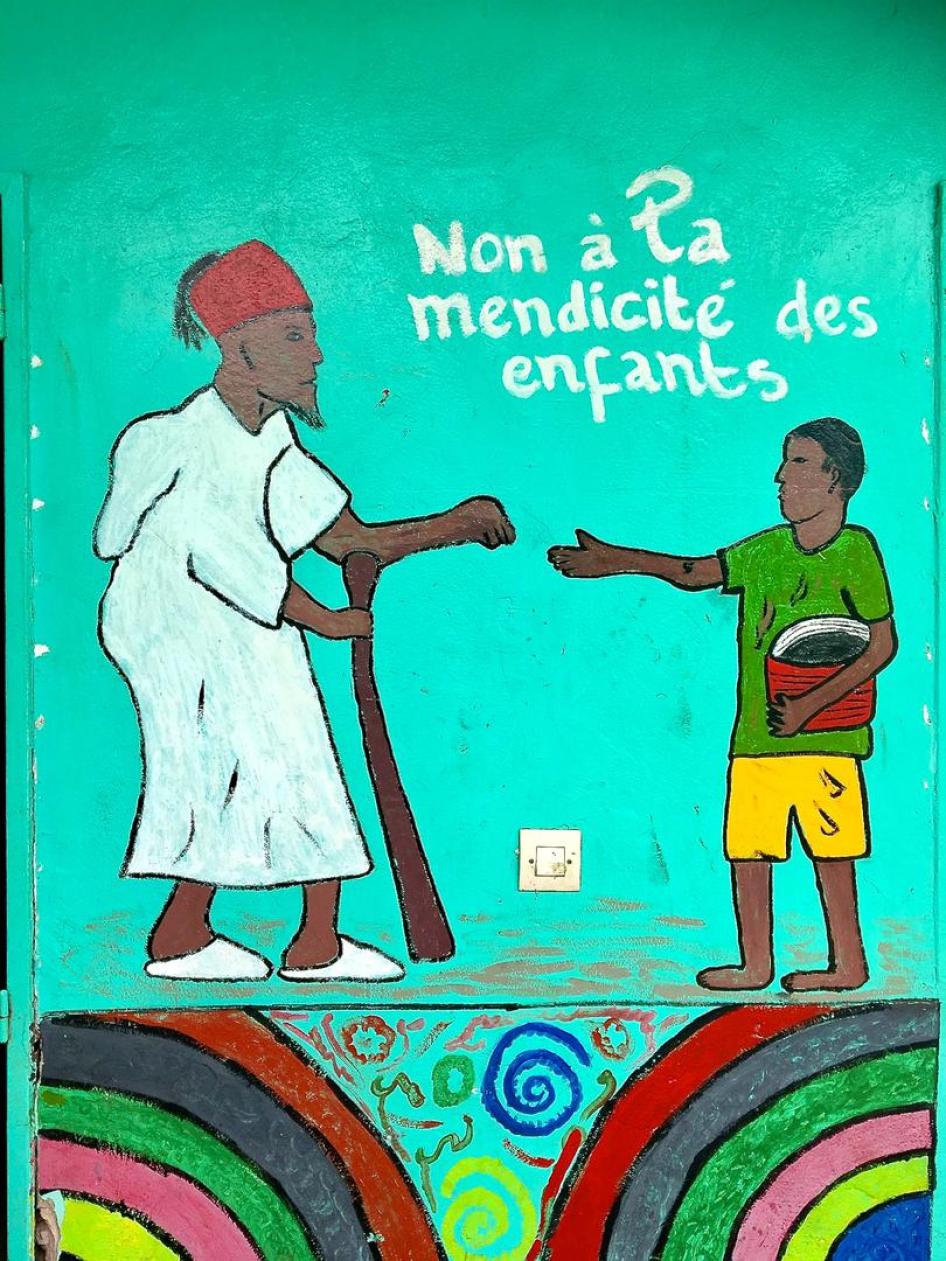

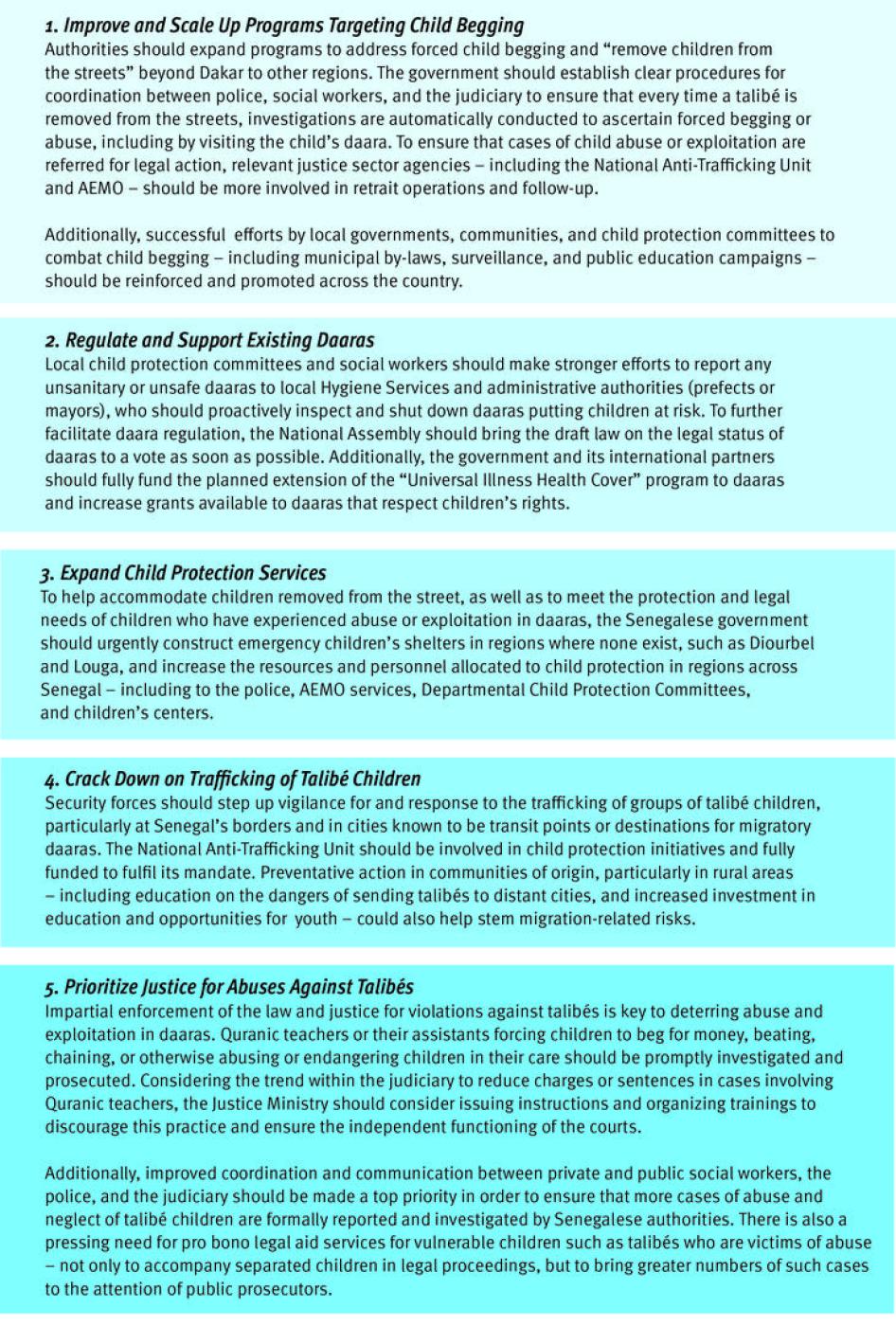

To protect talibé children from abuse, the Senegalese government should scale up and improve the retrait de la rue program, increase the capacity of child protection services, strengthen preventative and punitive responses to trafficking of talibé children, and prioritize justice for violations against talibés. Efforts by local governments and communities to crack down on child begging and regulate daaras should be supported by the Senegalese government and expanded across the country, and the government should consider leading national public communication campaigns to raise awareness of the risks to talibé children, existing laws and penalties, and the powers of administrative authorities (mayors or prefects) to regulate daaras in their jurisdiction.

To ensure lasting change for talibés, Senegal should take the following five steps. More detailed recommendations are included within each section and at the end of this report.

Finally, the international community should denounce ongoing abuses against talibé children; express support for an approach that equally prioritizes deterrence, social assistance, and public communication; and accompany the Senegalese government by providing financial, material or technical support to the priority areas identified in this report.

Methodology

This report, which builds on the findings of six previous Human Rights Watch reports since 2010, is based on a two-week research mission to Senegal’s Dakar, Saint-Louis, and Diourbel regions in June 2018; two months of research in Dakar, Diourbel, Louga and Saint-Louis regions in December 2018 and January 2019; and phone and email interviews conducted between May 2018 and November 2019 with sources in Dakar, Saint-Louis, Diourbel, Louga, Thiès, Tambacounda, Kaolack, Kolda, and Ziguinchor regions. Members of the Plateforme pour la Promotion et la Protection des Droits Humains (PPDH), a Senegalese coalition of rights groups, helped arrange daara visits and facilitated interviews in Diourbel, Louga and Saint-Louis regions.

For this report and a June 2019 report, “There Is Enormous Suffering”: Serious Abuses Against Talibé Children in Senegal 2017-2018, Human Rights Watch interviewed more than 150 people, including talibé children, Quranic teachers, child protection experts, social workers, activists, UN representatives, Senegalese police and judicial personnel, and government workers and officials in the ministries of Justice; Education; the Interior; Women, Family, Gender, and Child Protection; and the former Ministry of Good Governance and Child Protection. Information on several cases of child abuse was obtained through interviews with social workers who had worked with the children, from judicial records and court documents, and from credible media reports.

Human Rights Watch visited 22 Quranic schools and 13 children’s centers in four regions (Dakar, Saint-Louis, Diourbel, and Louga). Of the 22 Quranic schools, four were in Dakar, five in Diourbel, three in Saint-Louis, five in Touba, four in Louga, and one in Koki. Fifteen of these were traditional daaras practicing child begging, and seven were “modern” or “modernized” daaras (in accordance with the phrasing used in Senegal) that no longer practiced begging. Of the 13 children’s centers or shelters visited, seven were in Dakar, four in Saint-Louis, one in Diourbel, and one in Louga. Two were day centers and 11 were short- or long-term shelters, including one privately-run orphanage and four government-run centers. Ten of the 11 shelters hosted talibé children at the time of visit.

Interviews were conducted in French, Wolof and Pulaar. Those in Wolof and Pulaar were conducted with the assistance of interpreters, primarily social workers and child protection experts. Human Rights Watch did not offer interviewees any financial incentive, and they were informed that they could end the interview at any time. Throughout the report, names and identifying information of some interviewees have been withheld to protect their privacy and safety. Some people spoke on the condition of anonymity, out of fear of reprisals.

I. Programs to Reduce Child Begging

Under increasing national and international pressure to deal with the tens of thousands of children begging on the streets – vast numbers of which are current or runaway talibés – the Senegalese government launched an ambitious program in June 2016 to remove children from the streets and reunite them with their families.[1]

The first of its kind in Senegal, the program is known as the “removal of children from the street” (in French, le retrait des enfants de la rue, or the retrait). The program’s first phase lasted for just under a year, until early 2017, and was followed by a two-day anti-trafficking police operation in November 2017. The government conducted three months of street operations during the retrait program’s “second phase,” launched in April 2018.

Thus far, these government efforts to remove children from the streets have taken place only in Dakar and have had limited impact in reducing or deterring forced child begging or other abuses against talibés, which remain widespread — as extensively documented in recent Human Rights Watch reports.[2] However, a few local government and community-led efforts demonstrated some success, providing promising models for scaling up.

In late May 2019, President Sall committed to “definitively resolv[ing] the problem of children in the street.”[3] At time of writing, the retrait program was in a stage of restructuring and preparation for a third phase, according to Niokhobaye Diouf, child protection director in the new Ministry of Women, Family, Gender and Child Protection (“Family Ministry”).[4]

“Retrait” Program, Phase 1 (2016-2017)

In June 2016, President Macky Sall ordered “the urgent removal of children from the street,”[5] resulting in rapid launch of the first phase of the retrait program. From mid-2016 to early 2017, over 1,500 children – including some 1,000 talibés – were removed from the streets and placed in temporary shelters. Several hundred were returned to their families. However, as documented in a 2017 Human Rights Watch report, the program returned more than 1,000 children to the same Quranic teachers who had sent them begging in the first place. The government did not open formal investigations into the teachers involved, and no inspections were conducted to ascertain the living conditions at the daaras in question.[6]

The program was widely criticized by child protection experts and civil society activists for its hasty launch, the lack of coordination between the government ministry in charge of the program at the time (the former Ministry of Women, Family and Children)[7] and other ministries and civil society actors, and the decision to give monetary assistance to certain Quranic teachers as an incentive to stop child begging. Some social workers also criticized the alleged use of force by police when picking up children from the streets. Plagued with problems and limited funding, the program trickled to a stop in early 2017.[8]

Police Anti-Trafficking Operation (late 2017)

Prior to the launch of the new phase of the retrait program, an anti-trafficking operation in November 2017 in Dakar, led by Senegalese police and Interpol, demonstrated what it could look like to incorporate justice as an integral part of child protection efforts.[9] The two-day “Operation Épervier” (Sparrowhawk) picked up 54 children from the streets, of which 47 were reportedly talibés. Police arrested seven individuals, including five Quranic teachers, who were later prosecuted for exploiting children through forced begging.[10] (See Section V for more information on prosecutions.)

However, according to staff at two of the three children’s centers in Dakar where the 54 children were placed, police or government officials arbitrarily requested that some of the children be returned to their daaras instead of being reunited with their families.

An official at the state-run Ginddi Center said that several of the 28 talibés Ginddi received were returned to their daaras, following a request which he said came from the police. A few months later, he said, “Some of the children picked up from the street during Épervier were on the list again for the second phase of retrait, so we knew they had ended up back in the streets.”[11]

The director of another children’s center reported that a government official called a few months after Operation Épervier to request the return of 10 Bissau-Guinean talibés to their Quranic teacher, even though interviews with the children had already established forced begging. As the center had received temporary child custody from the juvenile court, the director was able to refuse the request and returned the children to their families in Guinea Bissau.[12]

It is highly concerning that these requests were made in the first place, as such actions directly contradict Senegal’s obligations under international and domestic law to protect children from exploitation.

“Retrait” Program, Phase 2 (2018)

In early 2018, the new Ministry of Good Governance and Child Protection (“Child Protection Ministry”) hastily pushed forward a revamped “second phase” of the retrait due to catalyzing events: “We started the second phase in a state of urgency,” said Alioune Sarr, former Director of Child Protection and head of the retrait program from late 2017 to early 2019. “The President gave firm instructions, and this was during a context of child abductions, kidnappings, and attacks against children, so we had to begin immediately.”[13]

From April to June 2018, 339 children between the ages of 7 and 14 – including 332 talibés – were picked up from the streets of Dakar. Of these children, 205 were reportedly Senegalese, 99 Bissau-Guinean, 25 Gambian, 5 Malian, 3 Guinean, and 2 Nigerien. An official at Ginddi Center, the state-run shelter where the children were placed pending family reunification, reported that most of the talibés mentioned begging for daily quotas of 300 to 1,000 francs CFA (US$0.50 - $1.80).[14]

Improved Practices

In the retrait program’s second phase, the Child Protection Ministry made some noteworthy improvements by ensuring that children were returned to their families; engaging directly with parents, who were urged to keep their children out of daaras that practiced begging; and increasing coordination with other ministries and child protection actors, with a view to improving the program’s efficiency and sustainability.

No Daara Returns; Increased Pressure on Parents

In an important improvement over the first phase, officials ensured that no children removed from the streets during Phase 2 were returned to their daaras.[15] By the time of Human Rights Watch’s visit to Ginddi Center in January 2019, all of these children had been returned to their families, according to Ginddi staff.[16]

“Last time [during the first retrait], we placed the children in Ginddi Center, but they were overloaded… So we gave some talibés back to the same marabouts, lecturing them, perhaps in the naiveté of thinking they would respect their commitments [to stop child begging],” said a Child Protection Ministry official. “A new strategy is the return of children to their families… No child was returned to their marabout this time.”[17]

The government also required parents, many in distant regions, to travel to Dakar to retrieve their children, warning them not to return their children to daaras where they were forced to beg. This time, the official explained:

We required all the parents to come present themselves in person. ...I said, ‘We are not spending a single franc for the parents. It is up to them to spend their money to come get their child.’ And we have the means to compel them. …Those parents who are in Senegal, we gave them 48 hours to come find their children. …We were very firm in the message.[18]

Improved Coordination Between Ministries and With Civil Society

Calling it a “new inclusive approach,” the Child Protection Ministry took steps to improve coordination with other ministries and civil society during the retrait’s second phase, in order to more efficiently return the children to their families and prevent recidivism.[19]

Following an April 2018 consultative workshop attended by representatives from several ministries, the police and judiciary, UN agencies and civil society,[20] the Interior Ministry’s participation in the program increased through involvement of prefects (local officials with authority over an administrative area, or department[21]). Departmental Child Protection Committees (CDPEs) – chaired by the prefects – were also formally involved for the first time.

A Child Protection Ministry official explained the roles of the prefects and CDPEs as follows: in each child’s locality of origin, the prefect was informed that a child had been picked up in Dakar and coordinated with the CDPE to summon the parents to Dakar.[22] In Dakar, he said, the children’s parents and Quranic teachers were sent to the city’s prefect, who explained the law against child begging and reportedly threatened both with penalties if the child ended up back in the street.[23] After the parents and children returned home, their local prefect was again informed and the CDPE tasked with follow up. The official also noted that his ministry was working with CDPEs and NGOs to develop a follow-up plan for each child, monitoring their reintegration and providing social support as needed.[24]

Problematic Aspects of “Retrait” Phase 2

Problems with the second phase of the retrait included the limited scope of the program and the failure of police, child protection actors and the judiciary to make progress on deterrence by ensuring investigations and prosecutions of abusive Quranic teachers.

Small Scale, Limited to Dakar

Based on existing studies, Human Rights Watch has estimated the number of talibé children forced to beg in Senegal to be over 100,000, of which approximately 30,000 have been found to be begging in Dakar.[25] Rolled out only in Dakar during the first two phases, the government’s retrait de la rue program has so far failed to reach the tens of thousands of talibé children subject to forced begging in other regions.[26]

Even in Dakar, numerous child protection activists and social workers – particularly those at children’s shelters – told Human Rights Watch that they had seen no overall decrease in the number of talibés begging since the program’s launch in 2016. From June 2018 to January 2019, Human Rights Watch and PPDH observed and spoke with scores of talibés begging on the streets of the cities of Dakar, Saint-Louis, Diourbel, Touba and Louga, highlighting the widespread and persistent nature of the problem.[27]

Police: Failure to Investigate Forced Begging During the “Retrait”

Police commissioners from the Urban Safety Division in Dakar, whose Special Juveniles Unit accompanied social workers to pick up children begging in the streets, told Human Rights Watch that the police were not instructed to investigate the children’s Quranic teachers or visit their daaras during Phase 2 – despite the fact that most of the children were talibés, and there was readily available evidence to suggest they were victims of trafficking, including the social workers’ findings and the reported statements of parents who did not know their child had been taken to Dakar.[28]

“We work on the basis of instructions. If we do not have instructions to question the marabouts, we cannot question them,” said a police commissioner from the Special Juveniles Unit,[29] noting that the process could potentially change for the next phase of the retrait.[30] A second police commissioner interviewed in 2018 similarly characterized the police’s role in Phase 2 of the retrait:

The children found on the streets, they were not interviewed by the police… They were removed and taken to Ginddi Center. …We limited ourselves to that stage, because this was not an operation organized by the Special Juveniles Unit – it’s a program organized by the administrative authorities… it’s the prefect who was in charge [this time]… the Special Juveniles Unit has not questioned the marabouts… nor opened investigations.[31]

In the context of the retrait, the police commissioner stated that it should be the responsibility of children’s centers to refer any cases of abuse or exploitation uncovered by social workers to the public prosecutor.[32] However, a Justice Ministry official contradicted this position: “The law already says exploitation is a crime – you don’t need instructions to conduct an investigation,” he told Human Rights Watch. “Normally they [the police] should always do an investigation to find out why each child is in the street. I think it's a problem of understanding on the part of the police… their role and obligation is to question the parents, the marabouts.”[33]

Beyond the retrait program in Dakar, Senegalese police in multiple regions of Senegal often failed to initiate or pursue investigations into cases of forced begging or abuse against talibé children in 2017-2019. This dynamic and its detrimental effect on talibé children’s access to justice is explored further in Section V of this report.

Child Protection Sector: Failure to Report Forced Begging

Child protection actors implementing the retrait, including children’s reception centers and former Child Protection Ministry officials, also failed to report or refer suspected cases of forced begging to the police or prosecutor’s office.

A Child Protection Ministry official involved with the retrait’s second phase said that no instructions had been issued to social workers or anyone else involved in Phase 2 to report cases of forced begging for formal investigation. He suggested that the warnings reportedly issued to parents and Quranic teachers by the prefect sufficed as a deterrent, and that sanctions would be implemented in future for recidivists.[34]

A Ginddi Center official admitted it was not standard practice for Ginddi to report cases of forced begging to the police, and they had not done so during the retrait’s first or second phases. He noted that while it was normal practice for Ginddi to report serious cases of suspected physical abuse, no such cases had been discovered during the retrait. He said he felt the onus for reporting and investigating cases should be on others – the police, judiciary, or the Child Protection Ministry – rather than on Ginddi’s overloaded social workers. However, he noted that after each retrait operation, Ginddi sent lists of the children and their personal information to the Child Protection Ministry and police’s Special Juveniles Unit, as well as submitting reports to the juvenile court in order to obtain temporary custody orders, all of which could have been a basis for further investigation into both abuse and child begging.[35] (These factors as barriers to justice for talibés are analyzed further in Section V.)

Justice Sector Not Involved in “Retrait” Program

Despite improved coordination between the Interior and Child Protection ministries, key justice sector actors – both within the judiciary and the Justice Ministry – were notably absent from the planning, operations and follow-up for the retrait’s second phase. Their participation in future phases of the program is vital, both to oversee legal processes of the child’s temporary placement and return to family, and to trigger investigations and prosecutions of those who forced them to beg, so as to deter further abuse.

The fact that no judicial investigations into forced child begging were opened during the program’s first or second phases indicates the judiciary has not played an active role in the retrait, though the Dakar prosecutor’s office was reportedly informed prior to the launch of the second phase.[36] Additionally, two important government agencies which could have assisted with follow-up or legal action were also not involved: the National Anti-Trafficking Unit, an inter-ministerial body headed by the Justice Ministry; and the Justice Ministry’s agency of “Non-Institutional Educational Action” (Action éducative en milieu ouvert, AEMO), mandated to ensure child protection, accompany children in legal procedures and assist with follow-up reporting after children are returned to their families.

Associate director Amadou Ndiaye of the Justice Ministry’s Directorate of Correctional Education and Social Protection, which oversees AEMO, emphasized the importance of coordinated follow-up by AEMO and the police to investigate and refer alleged abuse or exploitation cases, and to trigger relevant legal processes. Those processes should include “temporary custody orders” issued by juvenile courts to place children in shelters, and formal investigations by the prosecutor’s office where necessary.[37] “We continually see that talibés removed from the street return to the street. We need AEMO and the juvenile courts [involved] to ensure this doesn’t happen,” Ndiaye said.[38]

To this end, procedures to ensure regular communication between the police, the prefect, the judiciary, AEMO, and children’s center social workers should be integrated into future phases of the retrait program. A system should be established to automatically refer cases of forced begging uncovered during retrait operations to the public prosecutor’s office, and the Quranic teachers of any talibés who report forced begging should be formally questioned by the police.

Ultimately, the failure to incorporate investigations and prosecutions for forced begging as part of the retrait undermines durable or widespread impact for talibé children by suggesting that abusive Quranic teachers can continue to operate with impunity. As long as those responsible for forced begging continue to run their daaras without consequences, no matter how many children are removed from the street, others will continue to be exploited and abused.

Steps Toward a Revised “Retrait” Program in 2019

In the months following President Sall’s promise in May 2019 to restart the retrait program,[39] several inter-ministerial planning meetings were held to discuss next steps.[40] Niokhobaye Diouf, child protection director, informed Human Rights Watch that several ministries – Family, Justice, Interior, Education, Health and Social Action, Community Development, Culture and Communication – were meeting to discuss “the creation of a national steering committee which should validate the procedures of the retrait… and assess the needs before launching operations that are sustainable and effective.”[41]

The government taking time to plan and coordinate on the next evolution of the retrait, rather than rushing forward as in prior phases, is a positive step and could correct some of the problems detailed above. The appointed steering committee should develop standard operating procedures for the retrait that prioritize protecting children’s rights, sustainability, and justice.

|

Models for Success: Community Efforts to Reduce Begging Considering the limited impact of the retrait program from 2016 to 2018, it is important to look at what else is working. Though limited in scale, where any decrease in child begging has occurred in Senegal, it appears to have occurred in districts or municipalities with strong community-level engagement to fight child begging. According to several local child protection workers, such efforts – balancing proactive public communication, support for children, and deterrence – appeared to lead to a reduction in the number of daaras subjecting talibés to forced begging in these localities. For example, this was reportedly the case in the Medina and Gueule Tapée-Fass-Colobane municipalities of Dakar, where both mayors banned child begging in 2016 and the communities came together to enforce the ban. As part of an anti-begging project initiated by the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) and funded by USAID, the two mayors and their municipal councils conducted extensive community sensitization, as well as surveys and inspections of local daaras, prior to issuing municipal by-laws that banned begging. The projects also included plans to organize “surveillance units” to enforce the by-laws, as well as installation of kiosks or “solidarity houses” for the collection of alms to support local daaras.[42] In Gueule Tapée, the surveillance units were composed of community actors,[43] while Medina expanded the mandate of the existing administrative enforcement unit of the municipal council.[44] Representatives of both municipalities told Human Rights Watch that they had observed substantive impact by late 2018. Moussa Ndoye, the project coordinator in Gueule Tapée, estimated that begging had reduced by 80 percent in the municipality’s public spaces, with the majority of the local daaras having ceased the practice on threat of expulsion.[45] In Medina, project assistant Souleymane Diagne said that all the daaras within the municipality had stopped sending children to beg. “The other children begging [in Medina] come from daaras outside of our municipality,” he said.[46] Both project coordinators told Human Rights Watch that the by-laws were not strictly necessary to ban child begging, since the 2005 national anti-trafficking law had already prohibited the practice; however, they served to illustrate the political will of the mayors and the population’s support for ending child begging and protecting talibés.[47] The scope of the by-laws also goes further than the national law, which forbids “organiz[ing] the begging of others for a profit, engag[ing], lur[ing] or abduct[ing] a person for the purpose of begging, or exerting pressure on [him/her] to beg.”[48] For instance, the Medina by-law states that “Within the municipal perimeter of Medina, public begging, abuse and exploitation of children are prohibited,” and “Clandestine and irregular daaras that fail to meet the standards of security and health shall be required to close their establishment.”[49] Two other Dakar municipalities – Pikine Nord and Diamaguène Sicap Mbao – began anti-begging projects with USAID and UNODC in 2018, though no municipal by-laws had been issued by time of writing in late 2019.[50] |

II. Daara Regulation and Support

Thousands of daaras in Senegal operate without any government oversight or support, many from Quranic teachers’ homes or in abandoned or uncompleted buildings. Living conditions in traditional daaras are often cramped, filthy and unhygienic, posing a number of health and safety risks to children – including from fires, in which dozens of children have perished.[51]

While the government and its international partners have rolled out several important programs providing aid to daaras and constructing new “modern daaras,” these initiatives have not come close to meeting the scale of the need, nor do they address the issue of regulation.

Regulation of existing Quranic schools is not contingent on the passing of the draft law on the legal status of daaras – first drafted in 2013, finally approved by the Council of Ministers in June 2018, and awaiting a vote before the National Assembly at time of writing – though this would certainly encourage and facilitate regulation. Local administrative officials such as mayors and prefects already have the legal authority to inspect and shut down daaras posing a danger to the health, safety or wellbeing of children within their administrative area. This can include daaras with terrible living conditions or where children are forced to beg. Furthermore, local “Hygiene Services” under the Ministry of Health and Social Action may be dispatched to inspect the health and sanitation conditions of daaras, and they can issue fines or other penalties if conditions are not met.

In reality, few local officials have exercised such powers. Child protection experts and government officials said that this is often due to the social influence of Quranic teachers and the lack of political will to tackle a controversial issue; some local officials or their constituencies may also lack understanding of these powers and responsibilities.[52]

In Saint-Louis, where Human Rights Watch has visited dozens of squalid daaras since 2009, “there is a proliferation of daaras,” according to a staff member at a local children’s center. “They come, they rent a house, and they install the children in conditions of extreme hardship. There is no effective system in place to eradicate this phenomenon,” he said.[53]

In fact, Human Rights Watch found that local systems and processes that could tackle this issue do exist, though they are rarely utilized – with the exception of a few municipalities, including in Saint-Louis and parts of Dakar.

Successful Daara Regulation at the Local Level

In Dakar, the mayor’s offices of Medina and Gueule Tapée-Fasse-Colobane, supported in their anti-begging projects by USAID and UNODC, demonstrated what it could look like if local authorities took regulation seriously. Following the 2016 municipal by-laws that banned begging within their municipalities, they both closed several daaras that had failed to stop child begging or meet health and safety standards.

In Medina, “We closed six daaras that failed to meet the standards,” said project assistant Souleymane Diagne. Four of the Quranic teachers agreed to return home after the sensitization campaign, and two daaras were closed by the police.[54] Diagne recounted:

We took the initiative to close [the two daaras] with the police, based on the report by the Hygiene Service. …Personnel from the Hygiene Service went there to see the conditions in which the children lived. They found that, in fact, the conditions were not suitable. …It was unacceptable for the children to spend even one more day in either of these daaras, where the living conditions were extremely difficult. They had no sanitation, no water… the daara was in a dangerous location where people came to exploit them – it was a risk for the children.

…So the Hygiene Service issued an injunction to the municipality, requesting that we take steps to close these daaras. On this basis, we went there with the police to remove the children and shut down the daaras.[55]

In Gueule Tapée-Fass-Colobane, according to project coordinator Moussa Ndoye, the mayor’s office dispatched a security unit from their office to close down three daaras between 2016 and early 2019, evicting the Quranic teachers.[56]

In Saint-Louis, an official in the mayor’s office told Human Rights Watch that the District Child Protection Committees (CQPEs) had permission to monitor the daaras in their districts.[57] Between late 2018 and late 2019, according to the official, representatives from the mayor’s office and local Hygiene Services inspected 18 daaras after district community members – including some CQPE members – reported that children were living there in squalid and unsafe conditions. “Some of the buildings didn’t have doors, or roofs, or windows. There were no toilets. Basic hygiene conditions were not met; there was trash inside,” he said. Based on these findings, the official explained, the mayor’s office issued “summons” to the 18 building owners (6 of which were marabouts; the other 12 had allowed marabouts to rent or use their buildings), warning that they had 30 days to improve the structural safety conditions, on penalty of sanctions. He noted that Hygiene Services also set a deadline for the owners to clean up and improve sanitary conditions. Ultimately, the threat of penalties compelled the majority of these marabouts to depart from the buildings with their talibé children, the official said.[58]

The actions taken by these Dakar and Saint-Louis municipalities to use their administrative powers to regulate daaras are encouraging. Clear direction and funding for such efforts from the Interior Ministry, as well as a government-led public information campaign, could encourage more local governments to follow suit.

In order to prevent further talibé deaths from disease, fires, or other dangers in poorly maintained daaras – as well as to enforce the law against child begging – local governments nation-wide must step up and take stronger action. Mayor’s offices and prefectures are responsible for protecting children within their administrative areas. For their part, Child Protection Committees should report any unsafe, unhygienic or exploitative daaras to administrative officials or local Hygiene Services. In turn, local officials should make it a priority to ensure such daaras are inspected and shut down where necessary.

Daara Support and Social Assistance Programs

Several social assistance programs in 2017-2019 demonstrated some commitment by the Senegalese government and local authorities to address the health and education needs of talibé children and improve living conditions in daaras.

First, the Health and Education ministries announced in July 2018 that the “Universal Illness Health Cover” program for students would be extended to daaras.[59] Though the program had not yet launched nationally, the Health Ministry’s Directorate of Social Action and a few mayors’ offices, as well as private donors, funded the enrollment of several thousand talibé children in 2017 and 2018.[60]

Second, some mayors’ offices – such as in Touba, Louga, Saint-Louis – provided small ad hoc financial assistance to Quranic teachers, built latrines and provided supplies for several daaras.[61]

Third, the Education Ministry continued implementation of two jointly-led and jointly-funded programs that included efforts to “upgrade” or “modernize” daaras: the “Daara Modernization Support Project” (Projet d’appui à la modernisation des daaras, PAMOD) with the lslamic Development Bank, and the “Quality Improvement and Equity in Basic Education Project” (Projet d'Appui à la qualité et à l'équité dans l'éducation de base, PAQEEB), with the World Bank.[62]

PAQEEB supported 100 daaras in 2017 and 2018 to improve living conditions, cover health care, and integrate literacy and numeracy into their curriculums. According to a consultant involved with the project, an additional 400 daaras would be selected for PAQEEB’s next phase, which had encountered delays.[63]

PAMOD, originally launched in 2013, was intended to set norms for daaras, including a more diverse academic curriculum and standards of hygiene, health, child protection and children’s rights. The project has provided support to 32 “private modern daaras” and planned construction of 32 new “public modern daaras.” While at least half of the planned modern daaras had been built, none were yet operational as of early 2019.[64] Human Rights Watch requested updated information from the government, but had not received a response by time of writing.

After receiving support from these projects, some Quranic schools improved living conditions and abandoned the practice of begging.[65] However, the aforementioned initiatives have remained limited in scope. These programs should be expanded to extend their reach country-wide, in accordance with Senegal’s commitments under international law to uphold children’s rights to health, nutrition, medical care, education, and a safe and nurturing living environment.[66]

III. Child Protection Services

As illustrated by the extensive documented abuses in daaras – forced begging, beatings, chaining, sexual abuse – talibés account for a significant number of the children requiring protection and emergency assistance in Senegal.

When Human Rights Watch visited 13 public and private children’s shelters in four of Senegal’s regions between June 2018 and January 2019, social workers clearly stated that a large percentage of the children they assisted each year were talibés, mostly runaways who had fled situations of forced begging, abuse or neglect.[67]

This section describes how the child protection services in place to assist these children – police, state social workers, children’s shelters, and child protection committees – suffer from a severe lack of resources, personnel, and capacity. As a result, hundreds to thousands of talibé children subject to forced begging or violence each year either receive inadequate assistance or simply fly under the radar, remaining in abusive daaras or living in the streets.

Child protection services should be urgently expanded and fully resourced all regions in order to ensure that all talibé children who are victims of abuse or exploitation are removed from their daaras, receive appropriate care and legal assistance, and are returned to their families and not to the daara, regardless of the severity of the abuse.

Police: Limited Child Protection Personnel

According to interviews with police and social workers, the dearth of police officers trained and dedicated specifically to child protection work across Senegal prevents many child abuse victims, particularly talibés, from accessing the support and legal assistance they need.[68] Police commissioners interviewed by Human Rights Watch cited lack of time or personnel as a reason for failing to investigate or refer some cases of forced begging to the prosecutor’s office.[69]

The police’s Special Juveniles Unit in Dakar, mandated to handle child protection cases, is the only one of its kind in Senegal and had fewer than 10 officers as of mid-2017.[70]

In 2015, the Interior Ministry announced its intention to set up special “offices” to deal with cases concerning children in all central police stations. At time of writing no such offices had been established in other regions, though most police stations reportedly had one or more officers trained in child protection.[71] A government social worker in Diourbel said he had observed an improvement in police handling of children’s cases following trainings: “More police are trained on the care of children now – how to receive them, put them at ease, let them express themselves,” he said. “I would not say they are ‘well trained’ yet, but there has been progress.”[72] A government social worker in Tambacounda expressed similar views: “More and more the police are collaborating with us [on child protection cases], especially the inspectors.”[73]

The Interior Ministry should capitalize on this momentum and ensure that police officers in all regions receive adequate training in child protection. It should also fulfill its pledge to install special offices or units dedicated to juvenile affairs in all central police stations.

Lack of Support to AEMO Social Workers

Much of the state’s emergency child protection work is handled by the regional or departmental offices of the social services and legal assistance agency under Justice Ministry, known as the agency of “Non-Institutional Educational Action” (AEMO). However, AEMO offices are severely underfunded, inhibiting their ability to fulfill their mandate to handle urgent child protection cases in their localities, make the appropriate referrals, and support children through judicial processes.

Each of Senegal’s 14 regions has at least one AEMO office; a few regions – such as Dakar, Thiès, and Diourbel – have an AEMO office for each of their administrative areas or “departments.” AEMO offices are typically connected to the regional or departmental courts.

While AEMO offices are typically notified immediately of serious cases of child abuse, injury or death, Human Rights Watch found that they lack the resources and personnel to respond to every incident: most are staffed by just three or four people, and some have no working vehicle. As a result, AEMO social workers are constantly overwhelmed by cases, and some have no means of providing immediate emergency assistance to children, including talibés.[74]

Several AEMO social workers told Human Rights Watch that due to their limited time and resources, combined with the lack of children’s shelters (discussed below), they often felt compelled to focus on only the “most urgent” cases – notably severe abuse or rape. As a result, they said, runaway talibé children with “less severe” allegations – forced begging, neglect, corporal punishment – were at times returned to their daaras following a “warning” or “mediation” by AEMO staff with the responsible Quranic teacher.[75]

In Louga, at the time of Human Rights Watch’s visit in January 2019, the AEMO regional office had only one motorcycle at their disposal. In Mbacke (Diourbel region) and Saint-Louis, the AEMO offices had no working vehicle. The AEMO office in Mbacke, with a staff of four at the time of visit – two social workers, a security agent, and a cleaning lady – is responsible for the whole department of Mbacke, including Touba, a city with a population of over 500,000 and a high concentration of talibés. “We have enormous difficulty covering our mission, because of the lack of resources, human resources, logistics, and the size of the area covered,” said an AEMO social worker in Mbacke. “Our vehicle is currently broken down. Louga, Kaolack, Tambacounda… a lot of [AEMO] structures don’t have a vehicle, or else it’s broken down.”[76]

The AEMO coordinator in Saint-Louis at the time of Human Right Watch’s visit said that with a staff of three people, no vehicle and limited budget, he is constrained in what he can do. “For a while I haven’t even had a vehicle – it’s broken down – and sometimes the police call me late at night, even up to 4 or 5 a.m.” he said. “As soon as a child arrives, they call me. If I’m required to go, I take a taxi, or I walk. I don’t want to leave a child to spend a night with the police.”[77]

Lack of Emergency Children’s Shelters

Senegal also lacks sufficient care systems or shelters to accommodate children in emergency situations – many of whom are talibés – including runaways, abuse victims, children in danger, or those who have committed minor crimes. Such facilities are necessary to care for the child while family members are traced or long-term placements determined, which can take from days to months. Foster care in Senegal is practically nonexistent, with only a few placements reportedly made in specific regions.[78] The lack of emergency children’s shelters in numerous regions is a major obstacle to both child protection and justice, and has contributed to the limited scope of the government’s retrait des enfants de la rue program, constrained to Dakar from 2016-2018.

At time of writing, there were only eight government-run centers in Senegal able to provide shelter for children, with one reserved for children with special behavior problems (the “Social Adaptation Center” in Mbour). Of the remaining seven, Ginddi Center in Dakar is managed by the Family Ministry; the others, run by the Justice Ministry, include three “Centers of First Reception” (Centres de Premier Accueil, CPAs) in Dakar, Saint-Louis, and Ziguinchor, and three “Multipurpose Centers” (Centres Polyvalents, CP) – intended for longer-term stays, not emergencies – in Dakar, Diourbel and Kaolack. Though the Ministry of Health and Social Action operates several dozen social reintegration and reinsertion centers, these are neither capable of nor intended to provide emergency shelter to children, according to an official interviewed.[79]

All told, only five of Senegal’s 14 regions (Dakar, Saint-Louis, Diourbel, Ziguinchor, Kaolack) had government-run children’s shelters at time of writing, and only three regions (Dakar, Saint-Louis, and Ziguinchor) had reception centers dedicated to short-term and emergency stays – the three CPAs and Ginddi Center. These existing centers have extremely limited resources, staff and capacity.[80] A number of private or non-profit children’s shelters and centers operate in various regions, but there are not enough facilities to meet the need.

Some regions – such as Diourbel, Tambacounda, and Louga, in which there are thousands of talibé children and hundreds of runaways who end up on the streets each year – have no state-run facilities at all to shelter separated children while their families are traced. AEMO services in these regions rely on the willingness of private organizations, community volunteers, or even local marabouts to help them by hosting children in emergencies – which can clearly lead to conflicts of interest and other child protection concerns.

For example, one AEMO social worker noted that referring certain cases to the prosecutor would damage his relationship with marabouts who helped him meet the need for emergency beds. “Sometimes the care of the children we assist comes out of my own pocket, and I’m obligated to spend the night at the office with the children and pay for their food,” he added.[81]

In Diourbel, the state-run Multipurpose Center (CP) is the only children’s center. However, its capacity is limited to 20 children, and it is intended for longer-term stays focused on social rehabilitation. A staff member at the center told Human Rights Watch that some children can occasionally be hosted in urgent cases, but “emergency shelter is not the primary mission of the CP.”[82]

“For talibé children who run away from their daaras or who commit petty theft in Diourbel, we have nowhere to put them,” said Malick Sy, Diourbel coordinator for the human rights organization RADDHO. “When he receives these cases, the prosecutor often has no choice but to place them in preventative detention at the Diourbel Prison and Correctional Center. The lack of children’s centers is a big problem.”[83]

In Louga region, there are no government-run children’s shelters at all. The existing private centers at time of visit included three orphanages and a baby nursery. A “transit center” run by the NGO SOS Children’s Village, which could potentially accept urgent cases, was not yet operational at time of visit in January 2019.[84] “In Louga we have this problem – we don’t have emergency reception centers,” said an AEMO social worker. “For now, I am obligated to place children with other [private] structures, like the orphanages.”[85]

One private facility in Louga, Ahmed Madjid Orphanage, has periodically agreed to host children in urgent situations – often talibés – at the request of AEMO, even though it receives no government support for providing this service. At the time of Human Rights Watch’s visit in January, the orphanage hosted two runaway talibés, who both said they had experienced forced begging and beatings at daaras in Darou Mousty (a town in Louga region).[86] In November 2017, following the arrest of the five adults including one Quranic teacher in Kébémer (Louga region) on child trafficking charges, the group of talibé children removed from the teacher’s custody were divided up and placed at three different facilities – the Ahmed Madjid Orphanage, a daara in Kébémer, and the Saint-Louis CPA – while their parents were traced.[87]

The situation in Tambacounda region is the same: “We have no emergency children’s reception centers. In urgent cases, I am obliged to host children overnight at the office,” said an AEMO social worker.[88]

Considering the pressing need for more care facilities to adequately shelter separated or abused children, the Senegalese government – as well as its national and international partners – should urgently invest in the construction and operation of new children’s centers in regions around the country. Increased support to existing shelters, such as Ginddi and the three CPAs, could also help expand their capacity and ability to assist more children in need.

For longer-term placements of separated or abandoned children, the government should consider investing in development of a national foster care system, to avoid over-emphasis on placing children in institutions. Where institutions are the only possibility, a model which emphasizes creating a “family” dynamic, housing children in small groups with one or two primary caregivers, would best support children’s development and psychosocial wellbeing.[89]

Child Protection Committees: Progress and Challenges

Departmental Child Protection Committees (CDPEs) – and the local committees under their supervision – should ideally play an important role in preventing, reporting and addressing abuses against talibés in Senegal.[90]

Chaired by the prefect of the relevant administrative department, each CDPE brings together all local actors in the public, private, community and civil society sectors “whose mission has an impact on child protection,” with two individuals designated as “institutional” (state) and civil society focal points.[91] Members include representatives of administrative and judicial authorities, social services, health and education services, police and gendarmerie, civil society associations, NGOs, religious organizations, and local leaders.[92]

A key part of Senegal’s National Child Protection Strategy adopted in 2013, the CDPEs are meant to strengthen coordination to prevent abuses against children, conduct public sensitization, and establish a network for monitoring, referral and care of children in need of protection.[93]

The CDPE system has made several advances in recent years. First, several CDPEs have proactively made use of their network to refer child abuse cases to police and social services, and some have innovated new approaches. For example, in 2019, the Pikine-Guédiawaye CDPE in Dakar piloted a UNICEF-sponsored mobile technology, RapidPro, for reporting and responding to child abuse cases as they happen. In July-August 2019, the CDPE used this technology to respond to a case of a talibé child severely beaten by his Quranic teacher.[94]

Second, as noted in Section I of this report, the CDPEs were formally involved in the planning, family tracing, and follow-up for the government’s retrait program in 2018.[95] Third, local committees under CDPE supervision have increasingly been set up in municipalities, districts, and villages.[96] A former CDPE member also listed several other achievements of the committees: the development of tools for collecting and sharing information, including for identifying and monitoring victims; the mapping of all child protection actors and better harmonization of their approaches; and public education campaigns.[97]

However, three ongoing problems have blocked CDPEs from achieving their full effectiveness. First, some CDPEs lag behind in reporting and sharing information on abuse cases. A few CDPE focal points that spoke with Human Rights Watch between 2017 and 2019 were unaware of talibé child abuse cases or deaths in traffic accidents that had taken place during that period, including some that had been covered by the local press. In at least one case, the prefect was involved but had not shared a report on the relevant case with the focal point.[98]

Second, civil society members of CDPEs in some localities felt that local government officials and state services regularly failed to initiate or attend meetings, fulfill their role in responding to child abuses cases, or contribute resources to the committee’s activities.[99] “The CDPE only works thanks to the dynamism of civil society,” said a former CDPE member.[100] Human Rights Watch research in Saint-Louis, Louga, and Diourbel regions in 2018 and 2019 supported this finding, observing that some state services who were part of the CDPE – notably police and administrative officials – relied on NGOs or overstretched AEMO social workers to do the legwork of investigating daaras in cases of suspected abuse or danger to talibés.

Third, CDPEs lack funding and resources, limiting their ability to respond to cases of child abuse, including those against talibés. Only a few CDPEs have reportedly received some (limited) government funding[101]; most have relied on funding from UNICEF, the EU, and other donors, or on civil society actors to mobilize resources.[102] Several mayor’s offices provided partial funding, resources, or technical support to District Child Protection Committees (CQPEs) under their supervision, though some noted that they were constrained by limited budgets.[103]

To increase the effectiveness of the CDPE system in all regions and departments of the country, the Senegalese government should ensure that its national child protection strategy is adequately funded, that each CDPE receives the resources to implement its action plans, that administrative officials and state services increase their support to the CDPEs, and that CDPE members to follow clear protocols for reporting, tracking, and sharing information on cases of child abuse, exploitation, neglect, or endangerment – including those that involve Quranic schools.

IV. Combatting Trafficking of Talibé Children

Human Rights Watch research suggests that hundreds of talibé children in 2017 and 2018 were victims of human trafficking, which under Senegalese law includes the act of harboring of children in a daara and exploiting them for money through forced begging, as well as the recruitment or transport of children for this purpose.[104] A June 2019 Human Rights Watch report also documented how some parents perpetuate such practices by repeatedly returning runaway children to abusive or exploitative daaras.[105]

To address the many problems associated with the trafficking and movement of talibé children – forced begging and exploitation in daaras located far from home, abandonment of talibés by parents or Quranic teachers, and runaways that end up living on the streets – the government should take stronger action at multiple levels.

Steps Taken

Senegal and other countries of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) have taken several steps in recent years to address issues related to the vulnerability of “children on the move” in the region – a phenomenon defined by the Inter-Agency Group on Children on the Move as follows: “Children moving for a variety of reasons, voluntarily or involuntarily, within or between countries, with or without their parents or other primary caregivers, and whose movement… might also place them at risk (or at an increased risk) of economic or sexual exploitation, abuse, neglect and violence.”[106]

In recent years, ECOWAS states adopted standards on the protection of children on the move (2016), a strategic framework on child protection (2017), and a “Child Policy and its Strategic Action Plan (2019-2023).”[107] ECOWAS designated the West Africa Network for the Protection of Children (WAN) – composed of governments and civil society organizations – as the regional “referral mechanism for the protection of children on the move,” tasked with coordinating returns of separated children among member states.[108]

Senegal also launched a 2018-2020 national anti-trafficking plan, hosted discussions with ECOWAS states on strategies to address children on the move and in the streets, established frameworks of cooperation for return of children to neighboring states, and increased the number of police border checkpoints from 45 in 2014 to 77 in 2018, with at least two new posts constructed in 2018 along the borders with Gambia and Mali.[109] The National Anti-Trafficking Unit received increased funding and organized numerous trainings from 2017 to 2019 to reinforce vigilance on child trafficking, including with police and gendarmes, members of the judiciary, mayors’ offices and local administrative officials, Child Protection Committees, Quranic teachers, and civil society.[110]

In October 2019, the Senegalese government announced the launch of the country’s first human trafficking case law database, “Systraite.” At time of writing, Systraite was in a pilot phase, collecting information in five regions: Dakar, Saint-Louis, Thiès, Kédougou, and Tambacounda.[111]

Stronger Action Needed

While Senegal has taken some important steps, the government needs to more consistently enforce the 2005 national anti-trafficking law, strengthen border control to monitor the movement of talibé children, and tackle the root causes and factors leading parents in villages and rural areas to entrust their children to “Quranic teachers” who take them to distant cities, without appropriate guarantees.

Security forces should expand efforts in border regions to crack down on child trafficking, as well as in Senegalese cities serving as transit hubs or destinations for migrating talibés and marabouts. This should include stopping and questioning self-professed Quranic teachers or their assistants traveling with groups of children. Any individuals unable to provide identification and parental authorization for each child they are travelling with, as well as credentials or proof of their profession, should be subject to further investigation.

“The state already inspects vehicles crossing the border to see if they’re in order, so they should also investigate why children are migrating or traveling, for example from Guinea Bissau all the way to Dakar,” said Alassane Diagne of the Empire des Enfants children’s center in Dakar, which frequently receives runaway talibés originating from other regions and countries. “They need to crack down on this and involve all the law enforcement agencies – the police, the gendarmes. They should be stricter every time they see children traveling, to ask ‘who are you, where are you going, who is with you?’”[112]

In parallel, to address some of the factors influencing families to send their children away to distant daaras, the Senegalese government should take steps to increase children’s access to education nation-wide (including by removing school fees and indirect costs); expand programs creating opportunities for youth in rural areas (associations, apprenticeships, training); and scale up public sensitization about human trafficking risks and laws. In particular, Senegal should consider running a national public information campaign – with emphasis on rural areas, and ideally in collaboration with neighboring governments – to inform parents of the risks facing children who have migrated to attend daaras in distant cities.

V. Justice for Abuses

Long considered to be above the law due to their strong social influence in Senegal, Quranic teachers committing acts of child abuse, exploitation, or endangerment have increasingly faced investigation and prosecution in recent years – notably since 2017, with several dozen cases adjudicated by Senegal’s courts between 2017 and 2019.[113] That said, the number of investigations and prosecutions overall remained low relative to the widespread nature of the abuses.

Talibé children have three main options for access to justice: anyone can report an offence against a child to the public prosecutor; parents can file an official complaint; or public prosecutors can open an “ex officio” investigation.[114] In cases of human trafficking, an association may also file a criminal complaint on behalf of the child.[115]

However, hundreds of thousands of talibés live in daaras far from home, with family members either unaware of the abuse or unable or unwilling to commence legal proceedings. Additionally, a number of challenges at the judicial, police, social worker, and governmental levels have continued to pose barriers to talibé children’s access to justice or impede the effective administration of justice.

While civil society activists applauded the increasing number of judicial cases against abusive Quranic teachers, many lamented to Human Rights Watch that the number was still far too small to deter future abusers. Some noted how rarely the police initiated

investigations, despite the fact that – with thousands of talibés begging in the streets – “it’s exploitation in plain sight.”[116]

Social workers said that hundreds of child abuse victims, including talibés, pass through the child protection system each year without triggering formal investigations into those who subjected them to abuse.[117] They also noted how the failure to incorporate a justice component into the government program to “remove children from the streets” (the retrait) from 2016 to 2018 squandered an opportunity for deterrence, as noted in Section I of this report.[118]

The national increase in prosecutions for violations against talibé children marks an important step forward. However, in order for the threat of legal consequences to serve as a larger-scale deterrent to abuse, Senegalese authorities need to more proactively and consistently enforce existing laws to protect talibé children nation-wide.

Progress on Investigations and Prosecutions

The positive trend towards increased enforcement of the law against abusive Quranic teachers in recent years has been evident on several levels, according to Human Rights Watch’s analysis and interviews with Senegalese experts in the child protection, judicial, and policy sectors from 2017 to 2019. Human Rights Watch found that cases were more regularly referred to the police or courts for investigation by child protection services and the public; the police – to some extent – demonstrated increased willingness to arrest Quranic teachers suspected of abuse; an increasing number of these cases were adjudicated by the courts; and public prosecutors increasingly opened investigations of their own initiative, when children’s parents were not present or were unwilling to file complaints.

Experts credited the rise in investigations and prosecutions to a combination of increased reporting by the local press on abuses against talibés; the impact of public sensitization by child protection committees and NGOs; training of judicial officials and law enforcement officers; and increased international and national pressure to take action on abuses against children.[119]

“Investigations, prosecutions and verdicts against [abusive] Quranic teachers have increased… according to the statistics collected covering the period 2017-2019,” said Moustapha Ka, who was Director for Human Rights in Senegal’s Justice Ministry during that period. “At least around 10 convictions for the exploitation of begging of others have been identified.”[120]

Human Rights Watch research found that at least 10 Quranic teachers were prosecuted for abuses against talibés during 2015 and 2016 (four in 2015 and six in 2016), resulting in at least five convictions.[121] There may have been additional cases during that period for which Human Rights Watch did not receive information.

In 2017 and 2018, these figures increased: at least 25 judicial investigations into alleged abuses against male and female talibé children by Quranic teachers or their assistants were opened during that period in eight administrative regions, leading to at least 21 prosecutions and 18 convictions. Twelve of these convictions took place in 2017. Human trafficking prosecutions increased from previous years and accounted for 7 of the 18 convictions.

In 2019, at least seven Quranic teachers were convicted of abuse, including one charged with both abuse and trafficking. Human Rights Watch requested further information on 2019 cases from the Justice Ministry but had not received a response by time of writing.

Cases adjudicated in 2017-2019 for which Human Rights Watch received information are listed below. There were several additional cases mentioned by judicial officials and government social workers in several regions which Human Rights Watch was unable to verify in detail, and these have not been included in the charts below. Other prosecutions and convictions involving Quranic teachers during this period may have gone unreported.

2019 ConvictionsAt time of writing, Human Rights Watch was aware of the convictions of at least seven Quranic teachers in 2019: |

|

|

1. Ziguinchor |

A Quranic teacher who had beaten and tied up a talibé child of around 9-10 years old in February 2019 was convicted of assault and sentenced to three months in prison, according to local social workers.[122] |

|

2. Mpal, |

After the severe beating of a talibé in the town of Mpal led to the child’s death in May 2018, the child’s Quranic teacher was convicted in February 2019 of “assault and battery inducing unintentional death,” sentenced to two years in prison.[123] |

|

3. Pikine, |

A Quranic teacher was convicted of assault and battery and sentenced to three months in prison, following the severe beating in July 2019 of a 10-year-old talibé who had “wounds all over his body and scars from previous beatings,” according to a social worker involved in the case.[124] |

|

4. Touba, |

In July 2019, a Quranic teacher who had raped two of his female Quranic students, ages 8 and 10, was convicted of "rape of minors under the age of 13 and pedophilia, with the circumstance that the perpetrator had authority over the victims.” He was sentenced to 10 years in prison.[125] |

|

5. Saint-Louis |

A Quranic teacher who beat a talibé child for stealing in September 2019 was convicted of “assault and battery of a minor by a person having authority over him,” as well as human trafficking (“exploitation of begging”). He was sentenced to two years’ probation and a fine of 50,000 CFA (US$85).[126] |

|

6. Mbour, |