Summary

I was hit so many times, I can’t count ... we were all called to the coach and I was hit in the face in front of everyone. I was bleeding, but he did not stop hitting me. I did say that my nose was bleeding, but he did not stop.

— Daiki A., 23, Fukuoka, February 2020

Participation in sport should provide children with the joy of play, and with an opportunity for physical and mental development and growth. In Japan, however, violence and abuse are too often a part of the child athlete’s experience. As a result, sport has been a cause of pain, fear, and distress for far too many Japanese children.

Physical violence as a coaching technique has a long tradition in Japanese sport, often seen as essential to achieving excellence in competition and in personal character. This dangerous tradition has made the eradication of physical abuse in sport especially difficult. Coaches, parents, and even some players hold onto the mistaken belief that physical abuse in sport has value—and children suffer as a result.

There are some sports, contact sports in particular, that inherently involve physical violence between participants—boxing or martial arts, for example. While there are potential concerns about athlete safety within these sports, this report is not focused on harm that occurs within the field of play, as a part of normal competition. When we refer to violence or abuse in sport in this report, we are referring to behaviors that do not have any connection to the course of regular training or competition. For example, a coach hitting a player in the face as punishment, as described in the quote that began this section.

Abusive coaching techniques documented in this report include, but are not limited to, hitting children with bats and bamboo kendo sticks, slapping children across the face, and holding children’s heads underwater to simulate drowning. While abuse of a child includes harms such as physical and sexual violence, verbal abuse, and neglect, this report is primarily focused on physical violence, as that was the experience current and former child athletes reported to Human Rights Watch most frequently. Experiences of verbal and sexual abuse are also documented.

Clear and comprehensive reform is needed to eliminate these practices and protect children. While abuse of children is prohibited in Japan, there are no laws that explicitly extend this prohibition to the world of sport. Although the Japanese government and sports organizations have attempted, in recent years, to address physical abuse of children, child protection guidelines that apply to sports organizations, to date, have been non-binding suggestions, with no clear mechanisms for ensuring compliance.

Human Rights Watch’s research—including over 50 interviews with current and former child athletes at all levels of competition, an online survey, data requests submitted to sports organizations, and testing of existing reporting mechanisms—found that children in Japan still experience abuse in sport, and identified institutional gaps that blunt the country’s response to and prevention of such incidents.

In a well-known case in 2012, a 17-year-old high school basketball player in Osaka took his own life after suffering repeated physical abuse at the hands of his coach. Months later, the head coach of the Japanese Olympic women’s judo team resigned amid accusations that he had physically abused athletes in the lead-up to the 2012 London Olympics.

In the wake of these cases and facing pressure as Tokyo bid and prepared for the 2020 Olympic and Paralympic Games, the Japanese government and various leading sports organizations undertook a series of reforms. The most notable were the 2013 Declaration on the Elimination of Violence in Sport (a written statement exhorting sports organizations to track athlete abuse and establish reporting systems for victims), and the 2019 governance codes for national sports federations and other sports organizations (meant to establish guidelines across sports bodies). Yet, neither of these reforms adequately or specifically address child athlete abuse, and neither are legally binding, resulting in questions about how effective they have been and will be.

Child abuse is illegal in Japan, and, just this year, Japan enacted a total ban on corporal punishment, representing decades of reform work by civil society groups. This ban applies to sport. To make this even more clear, the Japanese government should specify that legal prohibitions on child abuse and corporal punishment (also referred to in Japan as “taibatsu”) extend to the world of organized sport. While there are several acts that could explicitly outlaw such violence and abuse (the Basic Act on Sport, the Child Abuse Prevention Act, and the Fundamental Education Law), references to child abuse in sport remain notably absent from each.

Child abuse, including child abuse in sport, requires criminal legal accountability and remedy. But sports organizations also have a primary responsibility to address abuse and protect child athletes. Without clear and comprehensive child protection protocols from leading sports organizations like the Japan Sports Agency (JSA), the Japan Sport Association (JSPO), and the Japanese Olympic Committee (JOC), sports federations are left to their own devices in creating systems for the prevention, reporting, investigation, and punishment of child athlete abuse. This fragmented authority structure has resulted in inconsistent and inadequate mechanisms for child athlete protection.

Among the Japanese sports organizations assessed by Human Rights Watch, we found wide variation in the type of abuse reporting structures available, with some having no system at all and some only accepting reports by mail or fax. There is no publicly available data to indicate how many abuse reports are investigated, and Human Rights Watch information requests to sports organizations revealed that many do not track such information. When coaches are found to have abused child athletes, there are no uniform standards for sanctions across sports. Many coaches tied to abuse, and even suicide by athletes, are still coaching today.

These institutional failures leave child athletes vulnerable to abuse. In an online survey conducted by Human Rights Watch from March to June 2020, 425 current and former child athletes reported direct experiences of physical abuse while participating in sport; this included 175 respondents 24-years-old or younger with recent or ongoing experiences of abuse, allowing us to assess current practices and their consequences. The responses include accounts of abuse from current and former child athletes participating in at least 50 different sports, across 45 prefectures.

Through interviews, Human Rights Watch was able to document the nature and negative consequences of these experiences in detail. For example, Shota C. (pseudonym), 23, a former high school baseball player, described being abused by the coach of his high school team in Saitama prefecture: “He punched me on the chin and I was bloody in my mouth. He lifted me up by my shirt collar.” This was a common experience for members of Shota C.’s team: “90 percent of my teammates experienced physical abuse.... We were all kind of joking, ‘You haven’t been beaten yet, when is it your turn?’”

Athletes interviewed by Human Rights Watch described a culture of impunity for abusive coaches. Of recent child athlete interviewees who experienced abuse, all but one reported that there were no known consequences for the coach.

Under international law, governments are obligated to ensure children’s right to play and children’s right to live free from violence or abuse. In order to end abuse of child athletes in Japan, the country will need a unified approach, guided by clear mandates and standards. As a start, the government should explicitly ban any form of abuse as a coaching technique in sport, and establish a Japan Center for Safe Sport, an independent body tasked solely with addressing child abuse in sport. This body should have the responsibility to create and maintain standards for child athlete protection, and should serve as the central administrative authority for investigating abuse claims and issuing proportionate sanctions against abusive coaches. Abuse cases involving criminal behavior should also be referred to police and prosecutors for concurrent criminal investigation.

With the Tokyo Olympic and Paralympic Games delayed until Summer 2021, Japan has one year to take decisive action before the games begin. Japan has a unique opportunity to show the world how it cares for its child athletes, and to lead in making sport safe for all. In doing so, Japan, as a pathfinding country of the UN Global Partnership to End Violence, would honor its commitment to ending violence against children. Taking decisive action to protect child athletes will send a message to Japan’s children that their health and well-being matter, place abusive coaches on notice that their behavior will no longer be tolerated, and serve as a model for how other countries should end child abuse in sport.

Key Recommendations

To the National Diet:

- Amend the Basic Act on Sport or introduce a new law to explicitly:

- Ban all forms of abuse by coaches against child athletes in organized sport;

- Delineate the rights of athletes, including the right to participate in sport free of abuse;

- Mandate training for all coaches of child athletes; and

- Mandate that any adult who becomes aware of child athlete abuse must report it.

- Amend the Child Abuse Prevention Law to explicitly expand the existing definition of child abuse in article 2, so that it includes child abuse in organized sport.

- Establish a Japan Center for Safe Sport, an independent administrative body tasked with addressing child abuse in Japanese sport. Among sports organizations, this independent body would have centralized administrative authority to address any allegation of child athlete abuse within organized sport in Japan. Responsibilities should include:

- Maintain standards to prevent and protect against child athlete abuse, and ensure full compliance with those standards by Japanese sports organizations;

- Receive complaints or reports of child athlete abuse directly, as well as via a centralized reporting system, into which all existing reporting mechanisms would flow;

- Conduct investigations into all cases of child athlete abuse in organized sport, issue proportionate sanctions against coaches—such as revoking their coaching license, suspending or banning them from coaching—and provide an appeal system for sanctioned coaches;

- Refer abuse cases to law enforcement for criminal investigation, where appropriate;

- Track and report data on the number of allegations, and the outcomes of investigations;

- Create a public registry of coaches who are sanctioned;

- Ensure free, ongoing, professional psychological support services for child athletes who have experienced abuse;

- Establish training standards for all coaches of child athletes; and

- Conduct education and awareness campaigns about the existence of this independent body, and the resources it provides.

- Provide the funding necessary to adequately staff and resource the Japan Center for Safe Sport, described above.

To the Japan Sports Agency (JSA):

- Introduce a new notice which explicitly does the following:

- Ban all forms of abuse by coaches against child athletes in organized sport;

- Delineate the rights of athletes, including the right to participate in sport free of abuse;

- Require training for all coaches of child athletes;

- Require that any adult who becomes aware of child athlete abuse to report it.

- Revise the 2019 sports governance codes so that all national sport federations and regular sport organizations are mandated to follow the code. The revised code should set out clear standards on reporting, investigation, and disciplinary measures for child athlete abuse in order to ensure abusive coaches are consistently held accountable nationwide, across sports and prefectures. The revised code should also mandate that any adult who becomes aware of child athlete abuse report it to the appropriate authorities, including law enforcement in cases of criminal behavior.

To the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT):

- In the third Sport Basic Plan (from 2022 to 2026), strengthen and prioritize the protection of child athletes from abuse, and clearly state concrete measures to achieve this goal.

- Update MEXT’s annual survey of abuse in schools so that it provides data on instances of abuse in school sport.

- Require child protection training and licensing for anyone coaching sport in schools.

To the Japan Sport Association (JSPO), the Japanese Olympic Committee (JOC), and the Japanese Para-Sports Association (JPSA):

- Require child protection training and licensing for anyone coaching sport for a member federation.

Methodology

Between January and June 2020, Human Rights Watch used a range of primary and secondary sources to investigate the abuse of child athletes in Japan, including: interviews with affected individuals, subject area experts, and government officials; an online survey of current and former child athletes; data requests to Japanese sports organizations; inquiries placed to the abuse reporting systems of Japanese sports organizations; and academic research documenting the prevalence and dynamics of the problem.

Researchers conducted 56 interviews with current and former athletes, representing at least 16 different sports and at least 16 different prefectures. These athletes included 44 men and 12 women, and ranged between 13 and 53 years old. Of these athletes, at least 26 were 24-years-old or younger and thus still children (defined in international law as any person under the age of 18) when the 2013 Declaration on the Elimination of Violence in Sport was issued; as such, some, or all of them, should have benefitted from changes in practices resulting from the declaration. At least 9 athletes interviewed also went on to become coaches, an experience that was also captured in the interviews.

Researchers met with the leaders and administrators of eight sports organizations: the Japan Sports Agency (JSA), the Japan Sport Association (JSPO), the Japan Sports Arbitration Agency (JSAA), the Japanese Paralympic Committee (JPC), and the federations of four individual sports. Finally, researchers interviewed 18 sports lawyers, team managers, academic experts, journalists, and parents of athletes.

To identify individuals who were willing to speak with Human Rights Watch about their experiences as child athletes, Human Rights Watch conducted outreach through Japanese NGOs and advocates for athlete rights in Japan. The World Players Association and their Japanese affiliates partnered with Human Rights Watch for this report and supplied contacts, expertise, and outreach central to this study, including introductions to sports federations and individual athletes who experienced abuse. Some of our first interviewees connected us to friends or former teammates who were willing to speak with us about their experiences as child athletes.

Some of our interviewees were identified through a solicitation form at the end of an online survey. The survey was used to collect basic data about experiences of child athlete abuse, as well as to invite survey participants to a subsequent, in-depth interview with Human Rights Watch researchers. The survey was distributed on Facebook and Twitter, and also shared by many of Human Rights Watch’s interviewees through their networks. The survey is not representative of all current or former child athletes. It provides data that only represents those who completed it. Still, this data is indicative of certain issues or trends in abuse.

The digital survey received 757 responses from current and former child athletes, representing at least 50 different sports and 45 different prefectures. These athletes ranged between 10 and 73 years old. Of these athletes, 381 (50 percent) were 24 years old or younger. The median age of survey respondents was 24. Of the respondents, 412 identified as male, 337 identified as female, 5 identified as transgender, 1 identified as other, and 2 preferred not to say.

No compensation was paid to either survey respondents or those who participated in interviews. Interviews were primarily conducted in Japanese, with Japanese-English interpretation. When possible, interviews were conducted face-to-face; however, several interviews were conducted online, over video-conference, especially between March and June due to restrictions imposed by the Covid-19 pandemic.

Human Rights Watch researchers obtained oral informed consent from all interview participants, and provided oral explanations about the objectives of the research and how interviewees’ accounts would be used in the report. Interviewees were informed that they could stop the interview at any time or decline to answer any questions they did not feel comfortable answering. Trauma support resources were provided to all interview subjects. For privacy reasons, pseudonyms are used for all current and former child athlete interviewees, except for a small number of adults, who chose to be identified.

Human Rights Watch also gathered information via data requests to and meetings with sports organizations. Information was requested from 13 sports organizations, of whom 5 responded with some data; 4 organizations responded saying they could not provide any data; and 4 organizations did not respond at all. For each sports organization, the data request inquired about the number of child abuse reports received, the number of child abuse investigations conducted, and the outcomes of these investigations. Human Rights Watch also asked for any guidelines each sports organization had for preventing or addressing child athlete abuse.

To assess the effectiveness of abuse reporting systems, Human Rights Watch researchers examined the reporting systems of 14 Japanese sports organizations.

Human Rights Watch also monitored news articles on child athlete abuse in Japan from January 12 to June 12, 2020. From this monitoring, we found reports of at least 39 individual abuse cases which occurred between 2008 and 2020. The forms of abuse reported were: physical abuse, verbal abuse, bullying among teammates, sexual harassment, and other forms of harassment. Human Rights Watch also reviewed academic research documenting the history, prevalence, dynamics, and impact of child athlete abuse in Japan and beyond.

I. Physical Abuse of Child Athletes in Japan Prior to Recent Reforms

I am tired of being beaten. I am tired of crying.… That’s why I don’t want to be in this world anymore.

— 17-year-old female javelin thrower, early 1980s

The above quote is taken from a suicide note, written by a 17-year-old female javelin thrower in the early 1980s. Just before her death, she had qualified for the national championships. But, before being able to compete in the event, she took her own life, saying that she could no longer cope with the physical abuse inflicted by her coach.[1]

The physical abuse of child athletes has long been a common element of sport in Japan and is often perceived as a normal part of one’s athletic experience. Makoto Y. (pseudonym), a former professional rugby player who played high school rugby in the Kyushu area in the 1980s, described to Human Rights Watch his experience: “Back then, it wasn’t recognized as what is now called taibatsu [corporal punishment], but I experienced it. I was not allowed to drink water [during practices].... We needed to practice for no reason. Athletes would be slapped and … I was practicing out of fear .”[2]

Tetsuya O. (pseudonym), a former professional basketball player who played high school basketball in Chiba in the late 1990s, said: “In high school, my teammate was hit so hard (by the coach) he had a broken nose. At practice games I saw a coach punch a player, drag students around, throw hot coffee in players’ faces. This kind of intimidating coaching style happened so often in any high school.”[3]

Despite the severity of the abuse experienced, several interviewees perceived that their coaches were acting with their best interests in mind. The terms “hitting with love” or “whipping with love” came up frequently, as in one interview with Noboru E. (pseudonym), a former player in the Japan Amateur Baseball Association who described the behavior of his coaches: “[They] would hit the players on the hip with the bat, or on the head with the grip of the bat. They were light hits ... it was whipping with love.”[4]

Even players who described severe abuse spoke of how the violence was intermingled with love. Naoko D. (pseudonym), for example, a former professional basketball player, described her experience as the captain of her high school team in Aichi in the mid-to-late 2000s:

Everyday someone was hit, and even during the game … I was the captain at the time, so I can’t even count how many times I was hit ... The coach would pull my hair and kick me … I was getting hit so much [on my face] that I had bruises ... drawing blood.… But I still, even now, like the coach.... [Then] I felt he trusted me as a player and he also helped me…. No one hated him [but] we were so afraid of the coach ... [When it comes to abusive coaches] … it’s the feeling of a person who has experienced domestic violence, it’s a similar feeling–the love and the abuse.[5]

In some cases, abuse of child athletes has directly resulted in life-long injury or death. For example, in 2004, a 15-year-old boy from Yokohama had skipped judo practice; his coach found him and made him spar one-on-one. According to the boy's mother, the coach choked her son until he lost consciousness; and then hit him to wake him up and choked him again when he briefly regained consciousness. The injury caused internal bleeding in the boy's brain, resulting in life-long cognitive impairment.[6] Between 1983 and 2016, there were at least 121 individuals who died while participating in school judo in Japan.[7] It is unknown how many of these cases involved abuse by coaches, but the rate of judo deaths in Japan has "no parallel" in other developed nations.[8]

Experts agree that physical abuse in Japanese sport has a long history, and some have tied abuse in sport to the militarism that came into school education in the WWII era.[9] While its roots may be decades old, physical violence against child athletes in Japan has persisted into the 21st century. In a 2013 study, researchers conducted focus groups with Japanese university students aged 18-22.[10] For those who reported taibatsu, the experiences included: “receiving a slap on the back of the head in a ‘playful manner,’” “being taken into a separate room and punched repeatedly in the stomach,” and “having a badminton racquet broken over one’s head.”[11] The study asked students how they felt about these experiences, finding that students often perceived physical violence as a normal—even valuable—part of coaching and training. One athlete said, “I think it [taibatsu] is fine as long as it makes the athlete and/or team stronger.” Another said, “Instead of the coach taking 30 minutes or so to lecture the student, giving them a single whack would do the job much better.”[12] These attitudes suggest the extent to which physical violence has been normalized in the context of Japanese youth sports.

A study published in 2012 compared attitudes towards coaches’ use of punishment in Japan and England, finding that Japanese players and coaches were far more likely to perceive physical punishment as acceptable. The researchers presented the participants (soccer players and coaches in Japan and England) with two hypothetical scenarios involving a player repeatedly showing up late for practice: one in which the coach “criticized loudly” the player (verbal punishment), and one in which the coach “smacked” the player (physical punishment). The participants were then asked to rate the “acceptability” of the hypothetical scenarios according to a scale. Japanese and English participants had a similar level of acceptance of the verbal punishment scenario. But, in the physical punishment scenario, English participants perceived the use of physical punishment as far less acceptable, while Japanese participants perceived the use of physical punishment as almost equally acceptable to the use of verbal punishment. This was true for both player and coach participants.[13]

Despite this long history of physical violence against child athletes and its perceived normalcy, prominent voices for change have emerged. For example, former MLB and Yomiuri Giants pitcher Masumi Kuwata told NHK in 2013: “I don’t think corporal punishment as a form of instruction makes one stronger; I think those teaching sports need to change their methods to fit the times.”[14] Kuwata’s comment came as the topic of physical violence in sport was thrust into the national spotlight, following two notorious cases of athlete abuse in the early 2010s.

In December 2012, a 17-year-old high school basketball player in Osaka took his own life after suffering repeated physical abuse at the hands of his coach.[15] The boy, who attended Sakuranomiya High School, was a strong student and the captain of the basketball team. The boy left a suicide note which said that he could no longer stand being physically abused by his coach. The coach later admitted to slapping the boy in the face multiple times, which he justified as a “necessary measure to make the team stronger.”[16] The coach was sentenced to a year in jail for assaulting the boy, but his sentence was suspended and he did not serve any time.[17]

In early 2013, the head coach of the Japanese Olympic women’s judo team resigned amid accusations that he physically abused athletes in the lead-up to the 2012 London Olympics.[18] Fifteen athletes on the Olympic judo team alleged that their coach had slapped them, shoved them, beaten them with bamboo swords, and forced them to compete while injured. In a joint statement, the 15 women wrote:

We were deeply hurt both mentally and physically because of violence and harassment taken upon us by [our] former coach, in the name of guidance. It went far beyond what it should have. Our dignity as humans was disgraced, which caused some of us to cry, and others to wear out. We participated in matches and training as we were constantly intimidated by the presence of the coach while we were forced to see our teammates suffer.[19]

These complaints, which the athletes made anonymously for fear of retaliation, were initially ignored by the national judo federation, so the athletes escalated it to the Japanese Olympic Committee (JOC), which then took action against the coach.[20]

These two cases served as the impetus for reform efforts in Japanese sport (for more about those reforms, see Section IV below), and were often cited by interviewees as a turning point in how physical abuse in sport is perceived in Japan.

II. Child Athlete Abuse Today

While there is a perception that the abuse of child athletes by coaches is on the decline in Japan, Human Rights Watch documented numerous cases indicating it is ongoing and still common. As documented below, our interviewing and surveying of current and former child athletes uncovered an alarming level of ongoing physical abuse in sport. As we heard repeatedly from interviewees, it is “shoganai”—which translates, roughly, to “it can’t be helped” or “it is what it is.” In addition, as noted above, Human Rights Watch monitoring of media reports from January 12 to June 12, 2020 turned up published accounts of at least 39 cases of child athlete abuse in prefectures across the country. Given the underreporting of child abuse in Japan and beyond, we know there are many cases of abuse that have not come to our attention. The continued lack of accountability for abusive coaches, documented later in this report, also suggests the ongoing acceptance of physical abuse as a coaching tactic.

No Comprehensive Tracking of Child Athlete Abuse

The Japanese government does not keep or make available comprehensive data on the current or historical prevalence of child athlete abuse in Japan, and hence there is no way to quantify its prevalence. Human Rights Watch is aware of only two recent surveys on athlete abuse: a 2013 Japanese Olympic Committee survey and a 2013 Japanese Association of University Physical Education and Sport (DAITAIREN) survey. These surveys only include subsets of child athletes, and to Human Rights Watch’s knowledge, have not been updated since 2013. They also employ different methodologies and inquire about different experiences.

JOC surveyed approximately 2,000 child and adult athletes affiliated with national sports federations, and found that 11.5 percent had experienced “power harassment and sexual harassment including physical abuse during playing sport.”[21] DAITAIREN surveyed 4,000 university students and found that 20.5 percent had experienced corporal punishment while participating on school teams, mostly in junior high school and high school.[22] Both surveys are out-of-date, and neither survey sampled all child athletes.

There are more recent numbers on reported instances of child athlete abuse that come from sports organizations themselves. For example, the Japan Sport Association (JSPO) operates its own hotline for the reporting of athlete abuse, and this hotline received 619 reports from November 2014 to March 2020.[23] Of these 619 reports, 397 (64 percent) came from athletes in elementary school, junior high school, and high school.

It is important to note that there is strong consensus among both international and domestic experts that child abuse is an underreported crime across the globe and in Japan. This is due to a number of factors, including the stigma of abuse, fear of retribution from the abuser or the team, and societal norms.[24] As such, the existing counts likely significantly underestimate the actual prevalence of abuse. This is as true of child abuse in sport as in other settings. These shortcomings in the available data mean that there is no clear measure of how many child athletes experience abuse in Japan today.

Despite the lack of concrete evidence, some perceive that child athlete abuse in Japan is on the decline; this is attributed to changing social norms, namely, that the use of physical violence against child athletes is less acceptable than it once was. A veteran high school baseball coach described the change in his own behavior: “When I was a player, physical punishment from coaches was very common, but nowadays it’s not acceptable so I don’t do it. I don’t do it because times have changed.”[25] Interviewees felt that parental attitudes have changed as well. Kenta K. (pseudonym), 25, a former high school soccer player, told Human Rights Watch: “Right now, taibatsu or harassment is reported by parents. So, whenever players have these experiences, there’s an environment where they can easily talk with their parents. Coaches know about this new environment. So, coaches should be careful about how they are treating their players.”[26]

Interviewees identified media coverage, in particular the rise of social media, as another primary reason for why physical violence in sport is less acceptable today. Hajime W. (pseudonym), a professional basketball player in his 30s, told Human Rights Watch: Maybe there are coaches who want to punch or kick their athletes, but now they cannot. Because they’re afraid of it being revealed in the media and they’ll lose their job.... When we were little, [it was] something being done daily, everywhere. It was not made public at that time. It wasn’t on TV or in the media. Then it started to come out in the media, and those coaches started to be punished.[27]

Even as some perceive norms changing, child athlete abuse remains prevalent in Japan, as documented below.

Abuse of Child Athletes

The incidents of child athlete abuse documented below focus on physical violence in sport that has no connection to regular training or competition. While there are some contact sports that inherently involve physical violence between competitors, this report is focused on physical abuse that occurs outside the field of play. We also documented incidents of sexual abuse and verbal abuse. When it comes to verbal abuse, we included any insult or threat reported as abuse by interviewees or survey respondents.

Punching, Slapping, Kicking, or Striking with objects

Of the commonly experienced forms of physical abuse, the most overtly violent is when coaches strike players with their hands, feet, or other objects.

While Human Rights Watch’s online survey did not allow us to definitively assess the prevalence of child athlete abuse in Japan, it provides insight into the common experiences of those respondents who reported abuse, and suggests the widespread nature of abuse in sport. Of 381 respondents 24 and younger, 19 percent indicated that they had been hit, punched, slapped, kicked, knocked to the ground, or beaten with an object while participating in sports. These experiences occurred in at least 22 different sports and at least 26 prefectures.

This experience was also well-documented in Human Rights Watch’s interviews. Shota C., 23, a former high school baseball player, described being abused by the head coach of his high school team in Saitama prefecture: “He punched me on the chin and I was bloody in my mouth. He lifted me up by my shirt collar.” This was a common experience for members of Shota C.’s team: “90 percent of my teammates experienced physical abuse... We were all kind of joking, ‘You haven’t been beaten yet, when is it your turn?’”[28]

Tsukuru U. (pseudonym), 20, another former junior high school and high school baseball player, described being abused by his junior high school coach in Kanagawa: “He would kick the players, and throw the ball at them from a close distance, and when the players were wearing helmets, the coach would hit the players on the helmet with the bat.” These instances of physical violence would occur in practices or in games, as punishment for mistakes on the field.[29]

Yuma T. (pseudonym), a professional basketball player in his 20s, described regular and repeated abuse by his high school coach in western Japan:

The coach would often slap us. It was normal for him to punch us in the stomach and kick us.... He often threw players like in judo.... This would happen in many practices, but not all. When a player would make a mistake in a play, the coach would slap or punch or kick or throw the player.… [This coach physically abused me] countless times ... [I would estimate] maybe 1000 or 2000 or 3000 times… Once he punched, he would hit several times, he didn’t stop after only one time. [30]

These slaps, kicks, and punches resulted in bruising, drawn blood, and dental injury: “I chipped a tooth from being elbowed by the coach. This was in my second year of high school; I was 17 years old. Basically, that happened when I missed a play.”[31]

Daiki A. (pseudonym), 23, a professional athlete, spoke of his experience playing baseball in junior high school in the Kyushu region:

I was hit so many times, I can’t count. Everyone [on my current team] was hit as high school athletes, everyone experienced taibatsu. I was playing baseball as a pitcher.... The coach told me I was not serious enough with the running [during practice], so we were all called to the coach and I was hit in the face in front of everyone. I was bleeding, but he did not stop hitting me. I did say that my nose was bleeding, but he did not stop.[32]

Keisuke W. (pseudonym), 20, a former water polo player described being punched in the stomach, choked, and held underwater. He said:

I was punched in the stomach [by my coach].... We use a cap for water polo. Athletes were dragged out from the pool by the cap strap, choking them. Another punishment is pushing kids underwater so they couldn’t breathe.... It is like the military. The younger kids were not as good. They would be frightened and quit the sport.... At that time, I felt it was a regime of terror, not strategy. Ruling by fear.[33]

There have also been high profile cases of this type of abuse documented in the media. For example, in 2017, a 17-year-old high school volleyball player in Tochigi prefecture was severely beaten by his coach and his teammates for breaking the team’s “no dating” rule. According to this rule, players on the team were not allowed to date other members of the volleyball team. When the coach discovered that one of the players was dating a female student manager, he made the player kneel on the ground, and repeatedly kicked the player in the chest. The player’s teammates also assaulted him.[34]

In 2018, a video surfaced in the media showing a high school baseball coach repeatedly slapping, punching, and kicking the players on his team. The team was from Aichi prefecture. In the video, the coach is seen striking at least five different players, while the rest of the team stands in a line and watches. The punches and kicks delivered by the coach are clearly forceful, frequently causing the players to stagger backwards.[35]

Excessive or Insufficient Food and Water

Current and former child athletes spoke to Human Rights Watch about being forced to eat excessive amounts of food, or having food and water withheld. Of 381 survey respondents 24 and younger, 25 percent reported being forced to eat excessive amounts of food, and 7 percent reported that they were not provided with enough food or water during competition. These experiences occurred in at least 22 different sports and at least 27 different prefectures.

Kaoru Z. (pseudonym), 13, is on his junior high school basketball team in Tokyo. He told Human Rights Watch about his coach, who often denies players water during games and practices when he is angry with the players. “Basketball takes a lot of energy … it is stressful for us when he does not give us water even when we ask.”[36]

Shota C., the former high school baseball player, described being forced to eat in order to gain weight: “After playing baseball, the [head coach] ordered some food directly to the grounds, and we used to eat them after practice. We were forced to eat them, even if we didn’t want to. If you didn’t eat, you were not motivated. If you wanted to participate in the national competition you needed to finish your daily meal.” Shota C. was scolded by the team’s head coach for not finishing this daily meal, and some teammates were kicked out of practices and games for not finishing their food.[37]

Moe J. (pseudonym), 20, is a university soccer player whose high school team played in the national finals. She described to Human Rights Watch her junior high school coach withholding water from players as a punishment for poor play: “During the national tournament, it was August in a very hot time. The first half we were winning, but we were not playing well, so during halftime we were called by the coach to the bench and told we needed to line up and run during halftime and we could not drink water.”[38]

Forced to Train when Injured, Punished with Excessive Training

No athlete should be forced to train when injured, or subject to training that puts their health at risk. Of 381 survey respondents 24 and younger, 22 percent reported being forced to train when injured, or being punished with excessive training. These experiences occurred in at least 15 different sports and at least 23 different prefectures.

Several interview subjects and survey respondents described “the running punishment”: being forced to run for long periods of time, often to the point of exhaustion. One survey respondent, a 22-year-old volleyball player from Kagoshima prefecture, wrote: “If we lost in a game, we were punished by being made to run back home, or to train for a long time....” Another survey respondent, a 22-year-old rugby player from Kanagawa prefecture, wrote: “I got heat stroke and vomited because of being forced to run as a punishment on a hot day.”[39]

Moe J., the university soccer player, described being forced to play through injury during high school: “We were scolded by the coach if we got injured. We had pain every day, so every day we were taking painkillers at practice … everyone was continuing practice even though the injury was not cured.... [S]o the injuries were [mainly] from too much practice.”[40] Interviewees and survey respondents often perceived these experiences as a normal part of their athletic training. Several survey respondents said things like: “I considered it normal,” or “I thought it was a normal thing at that time.”[41]

Cutting or Shaving Hair as Punishment

Of 381 survey respondents 24 and younger, 6 percent reported having their hair cut or shaved as punishment. Often, this punishment was for a minor infraction, like being late to practice. For example, an 18-year-old high school basketball player from Kanagawa said: “The soccer team at my high school had ... a rule that if a junior member made trouble, he would shave his head. One would be subject to this rule by being late, or forgetting to bring an item [to practice] ... [one] was forced to shave his head as an ‘example’.”[42]

A 20-year-old former middle school tennis player spoke of the prevalence of head shaving at her school in Tokyo: “In middle school, if students on sports teams made any mistakes, they were frequently forced by their seniors or coaches to shave their head with the shaver in the team’s club room.”[43]

Another former high school soccer player from Saitama (now 23 years old) spoke of the psychological impact of having his head shaved as a punishment: “Hair is a part of the body and is a form of self-expression. I suffered mental distress because I was forced to have a shaved head.”[44]

Abuse by Older Teammates

While the incidents documented above focus on physical abuse by coaches, Human Rights Watch researchers also heard about abuse by teammates, especially older teammates. In Human Rights Watch’s online survey, coaches were most frequently identified as the abuser, but the second most common abuser was an older teammate or senpai.[45]

On Japanese sports teams, there is often a hierarchical relationship between older players (“senpais”) and younger players (“kohais”). While this relationship can involve mentorship, the power dynamic at play sometimes involves abuse of younger teammates. A 20-year-old Human Rights Watch survey respondent, a former high school soccer player, noted: “If the senior/senpai targeted you, that is the end of the world.”[46] Another survey respondent, a 16-year-old basketball player, reported that senior teammates made him eat excessive amounts of food at a basketball training camp: “The seniors/senpais were more harsh than the coach. There were teammates who were forced to eat eight or nine bowls of rice in a day.”[47] A 20-year-old former high school soccer player interviewee said: “High school was very difficult, the hardest time for me.... The hierarchy between senior and junior students was more than I imagined. The seniors would call me to come to a place where there were no adults, they [berated me].”[48]

Sexual Abuse

Of the 381 survey respondents 24 and younger, 5 reported experiencing sexual assault or harassment while participating in sport as children.[49] While the experience of child sexual abuse was not often reported to Human Rights Watch, we recognize that there are a number of factors that make it difficult for victims to come forward. Worldwide, and including in Japan, child sexual abuse is an underreported crime, making it difficult to provide an accurate picture of the extent of the problem.[50]

Human Rights Watch interviewed one athlete who spoke to us of her experience of sexual abuse. Chieko T. (pseudonym), an elite athlete in her 20s from eastern Japan, reported being sexually abused by an older male teammate and her male coach. The abuse began when Chieko was 12 years old. For three years, while on team trips, her older teammate would regularly touch her breast while she was sleeping. This teammate also began abusing Chieko’s younger sister, who was 11. When Chieko told her coach about this abuse, he encouraged her to let the abusive teammate stay on the team: “this coach was begging me to not let this teammate quit ... because of [the abuse] .” The teammate eventually quit the team because of “awkwardness,” but the coach continued to invite him to team events and competitions.[51]

When Chieko T. was 18, she dislocated her shoulder during a competition, an injury requiring surgery, according to her doctor. Her coach, however, told her, “If you get surgery, your career ... is over for sure,” and said he could fix Chieko’s shoulder injury without surgery. Almost every day after training, the coach had Chieko meet him in his classroom, where he asked her to take off all of her clothes and would touch her naked body, saying he was doing it for “treatment.” After this treatment, Chieko said to the coach she “was scared [by the treatment].” The coach told her it is “all for [her],” and that “she asked for it.” Chieko described the experience: “[each time] I wanted to vomit, his smell, hands, eyes, face ... voice, I hated everything of him.”[52]

Another interviewee, a manager of a professional women’s soccer team, described to Human Rights Watch the sexual abuse perpetrated by one of the club’s male coaches. According to the manager of the team, an internal investigation revealed that the coach, a former “top player,” invited a teenaged player on the team to come to his home, where he had her sit on his lap, come into bed with him, and “play with him”.[53]

Verbal Abuse

While the focus of this report is on physical violence, athletes also experienced verbal abuse from their coaches, sometimes with devastating consequences. Of the 381 survey respondents 24 and younger, 18 percent reported experiencing verbal abuse.

Kaoru Z., the junior high school basketball player, told Human Rights Watch that his coach repeatedly berates him and his teammates during practice, calling them “stupid,” “fools,” and “idiots.”[54]

As documented in media reports, Tsubasa Araya, a 17-year-old high school volleyball player, took his own life in Iwate prefecture in July 2018. “Volleyball is the hardest,” Tsubasa wrote in a message found at his desk after his death. His parents blame the “verbal violence” of a coach for their son’s suicide. The Iwate prefecture board of education conducted an investigation into the suicide that included interviews with students on the volleyball team and the coach. The investigation report found the coach repeatedly had called Tsubasa “stupid” and a “fool,” and said such things to him as, “You are the tallest but the worst at playing [volleyball].”[55]

In 2019, a 15-year-old junior high school table tennis player in Ibaraki prefecture died by suicide, citing her coach’s abuse as a reason for her death. According to media reports, the girl wrote in her suicide note that her coach had threatened “to kill” or “punch” her. She wrote that the coach also threatened her teammates, referred to the team as “idiots,” pushed team members on the shoulder, and threw team equipment around. The girl stopped attending the table tennis club practices about 15 days before her suicide.[56]

Lasting Impacts of Abuse

The experience of abuse in sport can have a lasting impact on athletes, reducing their enjoyment of their sport, and in some cases causing lifelong mental health impacts.

This lasting emotional impact of abuse was reflected in Human Rights Watch interviews. Junko M. (pseudonym), a 22-year-old from the Kanto area who was training to become a professional ballerina, was slapped daily by her instructor from when she was 7 until she was 18. Though she did not feel the instructor was intending to harm her, she described how the experience of abuse has stayed with her even after moving on from this instructor: “Maybe this is called trauma – when someone’s hand came near my head – even my mom reaching to grab something from the kitchen in front of me – I got really scared and unconsciously reacted, or flinched to [avoid it]. I had this trauma for a couple of years....”[57]

Another interviewee, Tomohiko C. (pseudonym) started swimming at age 8. Now age 45, he says:

Swimmers were beaten with the fins. If we weren’t meeting targets, when we would touch the wall [at the end of a heat] the coach would hang us by the neck on the timer rope to punish.... I remember sinking without a breath and then the coach beat me.... At the high school swimming team, for students goofing off, the coach would line the team up and punch every kid [causing us to] fall into the swimming pool. These memories are so vivid in my mind. What I learned then was not about the joy of sport but about enduring.[58]

Chieko T., who was sexually abused by her former teammate and coach, described the reverberating impact of the experience: “I am not living with hating someone 24/7 anymore, but this thing will never go away from my mind, never.”[59]

Many studies have demonstrated the lasting negative impacts of corporal punishment on children. A 2016 review, conducted by the Global Initiative to End All Forms of Corporal Punishment of Children, of more than 250 studies worldwide found associations between corporal punishment and negative outcomes for children, with no evidence of any benefits.[60] Many of the negative impacts of corporal punishment in childhood can continue into adulthood. “Among the documented impacts of corporal punishment of children are physical harm and injuries, death, anxiety, depression, suicide, sleep and eating disorders, low self-esteem, increased aggression, and neurobiological harm to their brains,” said Dorothy Rozga, the Head of Child Rights at the Centre for Sport and Human Rights, a global organization based in Geneva dedicated to developing a world of sport that fully respects human rights. “In addition to the devastating toll that corporal punishment can take on children in sport, it threatens the ethics, integrity, and respect for human rights that that should be the heart of sport.”[61]

Coaches who were abused as athletes may continue training the next generation using physical violence. Professor Osamu Takamine of Meiji University says taibatsu is deeply rooted in Japan “because for many coaches in Japan, it was part of their own experience in sport.”[62] But other athletes have used their own traumatic experiences of abuse in sport to inform their efforts to safeguard the next generation of child athletes. Naomi Masuko, a former volleyball player on Japan’s national women’s team, said of her experience playing volleyball as a child: “I don’t remember ever being praised by my coach. Every day, I thought how not to be beaten by the coach. I never thought volleyball was enjoyable ... I hated volleyball as a player.”[63] Wanting to spare the next generation of youth what she experienced, Masuko ultimately founded a volleyball tournament in 2015 that prohibits coaches from verbally and physically abusing athletes. She spoke of athlete abuse as a cycle to be broken: “When I was older, I talked to my coach—and he said his generation was much worse. So, from his words, I at last understand this experience was a chain. And it is our job to break the chain.”[64]

III. Impunity for Abusive Coaches

An important reason that abuse of children continues to persist in Japanese sport is that individuals responsible for abuse are rarely held accountable. Several institutions are implicated in this failure, from sports organizations, to schools, to the criminal legal system. Without improved accountability, the behavior of abusive coaches will continue to go unchecked.

Child abuse in sport is criminally punishable as a violation of Japan’s penal code. Police and prosecutors in Japan have full authority to investigate and prosecute any cases involving assault or injury, including any such case that occurs within sport.[65] This has led to prosecutions and convictions in some cases of child athlete abuse. For example, the Sakuranomiya High School basketball coach, whose abuse was cited in a boy’s suicide note, was convicted of assault in 2013.[66] However, criminal punishment in child athlete abuse cases appears to be rare. None of the current or former child athletes Human Rights Watch interviewed or surveyed indicated that there were any criminal consequences for their abusive coaches. As Lawyer Hiroyuki Kusaba, who has been defending victims of abuse and their families in school sports for years, told Human Rights Watch, “Child abuse in sport is rarely treated as a crime.” He explained:

The idea that some violence and verbal abuse is necessary and unavoidable to improve skills in sport is imprinted on the minds of parents and children. In many cases, they feel that corporal punishment is not unfair, or even if they did, they think they should not report to a third party. Even if one reports to the police, the investigating authorities will often not build or prosecute the case because of the lack of evidence. This means that even if there are eyewitness accounts of physical violence, it is not easy to sufficiently establish that the act was not part of the instruction. [67]

Of the 425 online survey respondents who reported being physically abused as child athletes, only 31 ( 7 percent) indicated that there were any consequences for the abuser.[68] Failure to hold perpetrators accountable is an issue even in cases that receive public and media scrutiny. For example, the high school volleyball coach in Tochigi prefecture who, according to news reports, kicked and beat a 17-year-old boy (described in Section II above) was allowed to stay in his job and finish out his contract.[69]

In the 2019 case of the table tennis coach whose abuse was cited in the suicide note of a 15-year-old girl (described in Section II), the final decision on the coach's punishment was still pending at the time of this report's publication. According to the city's board of education, the final punishment decision will be made by the Ibaraki prefecture Board of Education. The coach is still working as a teacher, but is suspended from coaching the team. According to media reports, in addition to the abuse alleged in the 15-year-old player’s suicide note, the city's board of education received another anonymous complaint about the coach. He has admitted to verbally abusing his players and using harsh coaching methods.[70]

Even in cases where abusive coaches have faced consequences, the punishments can seem lenient relative to the severity of the underlying offense. For example, the high school baseball coach whose physically abusive behavior was captured on video in 2018 (described in Section II), received a one year suspension from the Japan High School Baseball Federation.[71] He was also suspended by the school that employed him, but was then transferred to an affiliated school, and is not currently teaching or coaching baseball.[72] And the judo coach who abused members of the 2012 Olympic women’s judo team returned to coaching for a company-based judo team in 2016, after his 18 month suspension had ended.[73]

Human Rights Watch found a similar pattern in interviews with current and former child athletes: coaches who had physically abused interviewees or their teammates were rarely held accountable. Of all the current and former child athletes we interviewed who had been physically abused, all but one said they were unaware of any consequences for the coach.

Kaoru Z., the 13-year-old basketball player who described having water withheld during practice and being verbally abused by his coach, told Human Rights Watch about his efforts to report his coach's behavior. Kaoru told his parents and he and his father then expressed their concerns to his homeroom teacher, the head of afterschool programs, on three separate occasions. Feeling that they were not making progress, they then spoke with the school principal. Kaoru believes the principal “said something to [the coach], and maybe he was better for a few days but then he went back to his old ways of coaching.” The coach is still coaching basketball at Kaoru’s school, and Kaoru wonders why. The experience has left Kaoru feeling hopeless about the value of reporting the coach to his parents, teacher, and principal. He said, “Nothing is going to change. It was worthless to report. All I wanted to say to my principal is ‘I would like a different basketball coach.’”[74]

Chieko T., who spoke of being sexually abused by her former coach, described to Human Rights Watch her attempt to hold the coach accountable for his abuse. She reported the abuse to the police, but no action was taken against the coach. According to Chieko, the coach is still coaching at a different club, and still shows up at Chieko’s competitions against her wishes.[75]

A manager of a professional women’s soccer club described the challenges she experienced in dealing with the male coach in her club who had sexually abused several players, including teenagers on the team. Given the seriousness of the allegations and the popularity of the coach—an ex-professional soccer player who was well-liked in the sports community—the manager felt it was important to fire the coach and announce the firing publicly, at a press conference. Despite having strong evidence of the coach’s abuse, however, the manager faced skepticism and pushback from the team players, other coaches, and the parents about her decision to fire a coach who was such a “top player”. The manager is dismayed that the fired coach is still coaching elementary school children. “He still has his license. We went to Japan Football Association (JFA), but since there wasn’t a police case … JFA said he could not be deprived of his coaching license.”[76]

Improved criminal and administrative accountability would send a clear message to athletes, coaches, and society at large that abusive coaching methods are not tolerated. As journalist Yuko Shimazawa, who wrote a book on the 2013 suicide of a Sakuranomiya High School basketball player, told Human Rights Watch: “We need to see not only the light of the athlete’s victory—but also the darkness of the coaching.”[77]

IV. Gaps in Reform

Despite almost a decade of reforms—changes that many Japanese sports organizations point to as evidence of progress in addressing child abuse in sport—our survey and interviews show that abuses continue, with serious consequences for the victims. This section outlines the reforms of the 2010s and details the significant gaps that remain in the prevention, reporting, and accountability systems that should protect child athletes in Japan.

In the 2010s, six key reforms changed the policies and structures that govern Japanese sports: the Basic Act on Sport (2011), the Declaration on the Elimination of Violence in Sports (2013), the establishment of the Japan Sports Agency (2015), a new Basic Sport Plan (2017), the Comprehensive Guideline for Athletic Club Activities (2018), and the Governance Codes for National Sport Federations and Regular Sports Organizations (2019). Each of these initiatives include provisions relevant to protecting child athletes, but, as written, they do not do enough to guarantee protection from abuse. (While the effect of the Governance Codes has yet to be measured, we identify several gaps in its current form, detailed below.)

The physical abuse of child athletes is not just a violation of children’s human rights and sporting principles, but a crime subject to criminal penalties. As such, the responsibility for protecting child athletes in Japan falls to a variety of institutions, including the criminal legal system, the child welfare system, schools and their governing boards, and sports organizations.

The role of national sports organizations—such as Japan Sports Agency (JSA), Japan Sport Association (JSPO), the Japanese Olympic Committee (JOC), Japanese Para-Sports Association (JPSA), and the national federations—merits special attention. Sports organizations have a unique responsibility to protect child athletes and unique powers by which to do so, but their responsibilities are not legally mandated. As a result, individual sports organizations are left to their own devices in implementing child athlete protection principles, and athletes are left to navigate a fragmented and often ineffectual maze of systems.

Poor Articulation of Legal Rights of Athletes, Legal Responsibilities of Sports Organizations

Given the long history of physical violence in sport in Japan, and its acceptance as a coaching tactic, it is especially important that Japanese law directly and unambiguously ban child abuse in sports. At present, Japanese law does not explicitly do so.

In its 35 articles, the 2011 Basic Act on Sport (Basic Act) outlines a number of goals and principles for Japanese sport, including: “improvement of sports facilities,” “the use of school facilities,” “the prevention of sports accidents,” “the promotion of scientific research on sport,” and “anti-doping.”[78] While the Act’s preamble says participation in sport is a human right, it does not codify the rights of the athlete, including the right to participate in sport free from abuse. Nor does it impose any legal responsibility on sports organizations to ensure protection from abuse.

The Basic Act only addresses athlete safety in a general way. For example, the preamble states that every citizen should be able to participate in sport in a “safe and fair environment.” And article 2 states: “Sport shall be promoted to retain and promote mental and physical health in those who play sport in a safe manner.” The only article dedicated to the government’s responsibility for athlete safety is article 14, which is titled “Prevention of Sports Accidents.” It reads:

The national government and local government shall endeavor to ... ensure safety in sport (including knowledge about the appropriate usage of sport goods) and implement other necessary measures in order to prevent or contribute to the reduction of sport accidents or other external injuries or problems caused by sport.[79]

The Basic Act does not explicitly establish protection from violence or harassment as an element of athlete safety.[80]

Like many other basic acts in Japan, the Basic Act on Sport also fails to establish a clear authority for implementing its provisions. On the one hand, it states that responsibility for implementing the law lies with the national government (article 3). But it also defers to local governments, allowing them to implement the law as “appropriate to the characteristics of the area, voluntarily and independently” (article 4). Further complicating the location of authority, the Basic Act appears to defer to sports organizations in regards to how they implement the law (article 5).[81] This fragmented system of authority is at the heart of the ongoing failure to adequately prevent and address child athlete abuse.

Advocates for child athlete protection involved with drafting the Basic Act on Sport hoped that there would be additional legislative rules and protections built on its foundation. However, Takuya Yamazaki, a lawyer involved with the creation of the act told Human Rights Watch: “As the name of the law says, it is ‘basic.’ Many more specific rules were supposed to be implemented/legislated, but it has been 10 years since it has been enacted and no specific rules have been enacted.”[82]

The Sport Basic Plan, the five-year plan which accompanied the Basic Act and guided its implementation, was first established in March 2012. The 2012 plan did not address the need to protect athletes from physical violence and harassment.[83] The second five-year Sport Basic Plan, established in March 2017 and set to expire in 2022, acknowledges the importance of protecting athletes from physical violence and harassment, but it does not establish specifically how to do this. It does emphasize the importance of coach training, and points to a new curriculum for coaches. While this is a positive step, the prevention of violence and harassment should be further prioritized, with specific measures outlined in more detail.

A Fragmented System for Addressing Child Athlete Abuse

Without a national law codifying the responsibility of sports organizations to protect child athletes from abuse, sports organizations are allowed to decide on their own whether and how to set up systems of response.

The Japan Sports Agency (JSA) was established in 2015 as a division of MEXT to unify and centralize government policy on sports and to prepare for the 2020 Tokyo Olympic and Paralympic Games.[84] Prior to 2015, the creation and implementation of sports policy was spread across various ministries within the government. While JSA addresses that issue—it has central authority for sports policy making within the government—it has no direct oversight of or legal authority over individual sports federations.

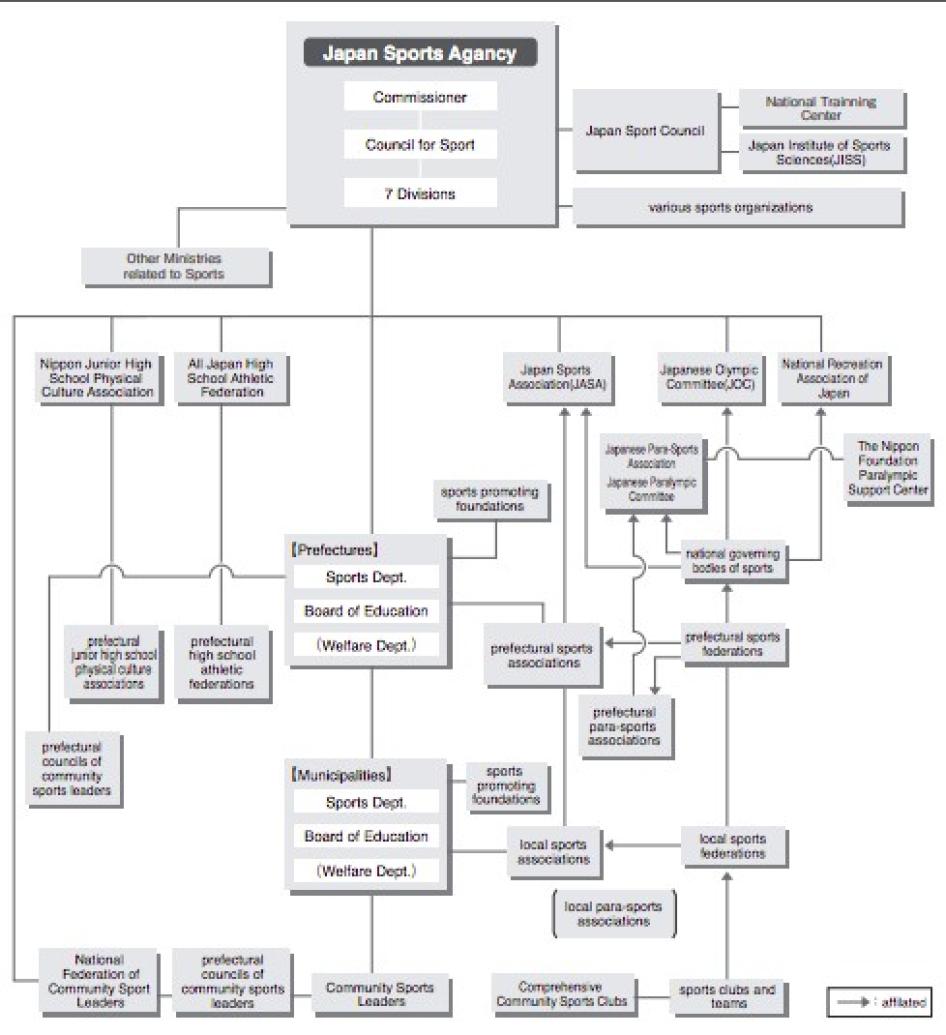

As demonstrated in the graphic below, created by Sasakawa Sports Foundation in 2017, this leaves dozens of organizations with oversight over different aspects of Japanese sport.[85] For example, the Japan Sport Association (JSPO) oversees the national and prefectural federations, but largely defers to the autonomy of these federations in operational matters; the Japanese Olympic Committee (JOC) oversees Olympic-level athletes; and the All Japan High School Athletic Federation oversees extracurricular high school sports.

One consequence of this fragmented structure is that there is no sports authority in Japan that exercises the power to identify, investigate, and punish child athlete abuse across all sports. While JSA is the central authority for sport in Japan, its mandate is limited to voluntary investigations, with no ability to issue punishment or sanctions.

JSA does not have an internal organizational infrastructure for tracking and addressing child athlete abuse.[86] There is no child protection unit within JSA, and the responsibility for addressing child athlete abuse is spread across various departments. As for tracking cases, in response to a Human Rights Watch request for guidelines on child athlete protection, JSA responded: “JSA does not set guidelines on how to create systems for reporting the abuse of child athletes … [or] how to investigate reports of child athlete abuse.” Human Rights Watch also asked JSA for any data it had tracking reports of child athlete abuse, either collected by JSA itself or via the individual sports federations; JSA responded: “JSA does not collect those numbers.”[87]

Reformed National Standards Still Fall Short

The 2013 Declaration on the Elimination of Violence in Sports (2013 Declaration), the second Sport Basic Plan issued by JSA in 2017, and a pair of governance codes issued by JSA in 2019 took steps to combat abuse of athletes. However, none include legally enforceable mandates, and all defer to individual sports organizations in how to implement the principles.

The suicide of the child basketball player and the abuse of the Japanese Olympic women’s judo team described above provided an impetus for the issuance of the 2013 Declaration, co-signed by five of the largest Japanese sports governing bodies—JOC, JSPO, the Japanese Para-Sports Association (JPSA), the All Japan High School Athletic Federation, and the Nippon Junior High School Physical Culture Association.[88] The declaration states, “Acts of violence are never tolerable whatever the reason and must be eliminated from all aspects of sports,” and directs sports organizations to “maintain a system to study the state and causes of violence in their associations and organizations, to establish guidelines, training programs, and so on concerning organizational operations and the elimination of violence, to establish consultation services, and so on.”[89]

While the declaration directs sports organizations to act, it does not provide clear standards for compliance. As a result, sports organizations have been left to their own devices in terms of establishing violence prevention, reporting, and accountability systems. Due to a lack of compliance tracking, it is unclear how many sports federations have implemented the declaration’s directives. Shoichi Sugiyama, a sports lawyer interviewed by Human Rights Watch, said of the declaration: “There were hardly any implementable guidelines after this declaration, in my understanding.”[90]

In June 2019, JSA issued two guidelines for the governance of sports organizations: the Governance Code for National Sport Federations, and the Governance Code for “Regular Sport Organizations” (those that do not fall under the national federation system).

In both cases, these governance codes are not uniquely focused on the prevention of athlete abuse—they are primarily concerned with other matters of governance, such as financial management, governing boards, and information disclosure. Specific systems for addressing athlete abuse are not laid out; instead, athlete abuse is grouped into broader categories of malfeasance.

The Governance Code for National Sport Federations requests national federations to: 1) establish mechanisms for reporting malfeasance; 2) establish systems to investigate reports of malfeasance; and 3) establish protocols for disciplining violators.[91] While the responsibility for implementing these systems and protocols is left up to the individual national sports federations, a new “governing body” (which includes JSPO, JOC, and JPSA) is tasked with monitoring compliance.[92] National federations found to be non-compliant with the governance code are to be reported during “roundtable meetings” of the governing body, JSA, and JSC. JSA will then publish the result and request that the national sport federation make improvements.

There has been no formal assessment of compliance to date: the first assessment is to be conducted at some point in 2020, with the assessment of all federations expected to take up to four years. These assessments will be made public. The organizations within the governing body (JSPO, JOC, and JPSA) would not be subject to governance codes’ mandates, and hence would not be monitored for compliance outside of their own self assessments.[93]

The Governance Code for Regular Sport Organizations does not have a compliance mechanism under JSA, and therefore responsibility for implementing the code is left entirely up to the individual sports organizations. Principle 3 of the code states regular sport organizations should “thoroughly recognize compliance including for the elimination of violence,” and specifically encourages organizations to have compliance training with a focus on violence by senior officials and coaches. However, it does not specifically instruct organizations to create reporting, investigation, and disciplinary systems.[94]

These governance codes represent important progress, particularly in the creation of a new governing body to hold national sports federations accountable for improved athlete protection. While both include useful provisions and articulate important principles, they are not legally enforceable. The code for national federations stipulates that the governing body should monitor their compliance with the terms of the code, but it remains to be seen how it will work in practice. In the meantime, as detailed below, sports organizations’ systems for addressing child athlete abuse remain woefully inadequate.

Inaccessible Reporting Systems

Dozens of organizations have their own mechanisms for receiving complaints of child athlete abuse, including JSC, JOC, JSPO, JPSA, and individual sports federations. And this fragmentation will continue: the 2019 Governance Code for National Sports Federations provides that each individual federation is responsible for creating its own abuse reporting mechanism. As a result, there is no uniform process or standard for what a reporting system should include. In the absence of a centralized system or uniform standards, some sports organizations have created their own reporting mechanisms, with significant variation in how and when victims can reach them, and what the reporting process requires. Because of this fragmented structure, there is currently no public reporting on the total number of child athlete abuse complaints in Japan.

Human Rights Watch researchers tried to discern the reporting systems of various sports organizations, including JSA, JSC, JSPO, JOC and the national federations of 10 individual sports. To illustrate the variations and gaps across sports organizations, the chart below documents the available abuse reporting systems, at time of writing, of these 14 major sports organizations in Japan.[95]

HRW researchers did not find any type of identifiable reporting system for two organizations: JSA and the Japan Basketball Association. Eight organizations had email reporting systems; six had hotline numbers listed; and four had online forms for abuse reporting. Mail and fax systems, which Human Rights Watch considers outdated and inaccessible to child athletes, were used by six and four sports organizations, respectively.

For the organizations with hotlines in place, finding the phone number was not always straightforward, sometimes requiring additional research beyond a sports organization’s homepage. Furthermore, hotlines’ hours of operation differed widely, and were often limited. The JSPO hotline, for example, was only open on Tuesdays and Thursdays between 1 p.m. and 5 p.m., and was shut down due to Covid-19 at the time HRW researchers reached out.

A number of organizations require the victim to report directly to a law firm, a prospect that may feel intimidating to a child athlete. And some organizations do not allow anonymous reporting, an option that could alleviate athlete concerns about privacy and retaliation. A few organizations (including JSPO and JSC) also require the reporting party to provide personal information beyond their name (such as phone number, fax number, or address).

|

Sports Organization |

Were Human Rights Watch researchers able to identify a reporting mechanism? |

|||||

|

Hotline / telephone |

|

Fax |

|

Online form |

Any reporting mechanism |

|

|

Japan Sports Agency (JSA) |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

|

Japan Sport Association (JSPO) |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Japan Sport Council (JSC) |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Japanese Olympic Committee (JOC) |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

|

All Japan Judo Federation |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

|

Japan Amateur Baseball Association |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

|

Japan Basketball Association |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

|

Japan Football Association |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Japan Gymnastics Association |

No |

No |

No |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Japan Rugby Football Union |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

Yes |

|

Japan Swimming Federation |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

No |

Yes |

|

Japan Sumo Federation |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

|

Japan Table Tennis Association |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

|

Japan Volleyball Association |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Even if these federation-led reporting mechanisms worked perfectly, experts agree that athletes are often reluctant to report abuse to the federation that oversees their sport. Shoichi Sugiyama, a sports lawyer interviewed by Human Rights Watch, described this reluctance: “If I am a table tennis athlete, it is difficult for me to consult with my own federation, because if I complain about my coaches, I am fearing retaliation from the coach, or I fear that I will be dealt with differently [by the federation].”[96] This fear of reporting to an athlete’s own federation was also reflected by the parent of an abused former judo athlete who was disabled after an injury caused by his coach: “Even if someone reports to a federation, [the person fears that] ... eventually their coach would hear the report and be likely to revenge.”[97]

According to Lawyer Sugiyama: “This is why JOC, JSC or JSPO has a hotline. It’s easier for an athlete to consult [with those hotlines] than with their own organizations.”[98] While the JSPO, JSC, and JOC hotlines provide alternate avenues for abuse reporting, they have their own limitations. The JOC and JSC hotlines are available only for Olympic-level or elite athletes.[99] And in cases where a victim turns to the JSPO hotline for help, JSPO might share the allegation with the federation that oversees their sport.[100]

An additional problem with the existing reporting structures is that most athletes do not seem to know of their existence. Of all the current and former child athletes interviewed by Human Rights Watch, only one (a university student who played baseball in high school) said he was aware of a hotline or other mechanisms for reporting abuse. He did not learn about the hotline directly from a sports federation, but from a sports lawyer who gave a lecture on athlete rights at his university.[101] None of the athletes we interviewed said they had reported their experience of physical abuse to a sports organization.

Because existing abuse reporting systems are so varied and fragmented, it comes as no surprise that Japan lacks comprehensive and uniform data on the number of child athlete abuse cases and their outcomes. While some individual sports organizations track some aspects of this data, it is not available across all levels of all sports.

Incomplete and Dispersed Investigation Systems