Summary

In the United States, access to lifesaving medication is a privilege that many cannot afford. Soaring medicine prices and inadequate health insurance coverage can result in unaffordable out-of-pocket costs that undermine the right to health, drive people into financial distress and debt, and disproportionately impact people who are socially and economically marginalized, reinforcing existing forms of structural discrimination.

“We almost lost my sister,” Sa’Ra Skipper, 25, of Indianapolis, Indiana, told Human Rights Watch in June 2021. “That was a really tough time, to see my sister lying in a hospital bed because she was just trying to help me out ... she kept me alive.”

In 2018, Skipper was working a job with health insurance that did not cover the insulin she needed, leaving her with monthly out-of-pocket costs of about $1,000. “How is somebody supposed to afford that?” she asked. “I wasn’t able to.”

At the time, Skipper’s sister, who also has diabetes, worked a lower-paying job and received free insulin from Medicaid, the US public health insurance program for people with low income. “[She] was giving me insulin,” Skipper explained. “We were sharing insulin out of the same vial ... I felt like I was taking from her.... But the system [didn’t] give me any other choice but to make me live this way.”

One night, Skipper took her nighttime dose of insulin and left the vial on the dresser for her sister to see. But her sister, unsure of whether Skipper had taken hers, took less than her normal dose to make sure that there was enough left. The next day, Skipper’s sister went into diabetic ketoacidosis, a potentially lethal complication of high blood sugar, and had to be hospitalized for four days. “She almost went into a diabetic coma.”

“They know that people are dying, that people can’t afford this,” Skipper told Human Rights Watch, speaking about the companies that manufacture the analog insulins upon which she and her sister depend.

As Skipper’s story shows, people with chronic health conditions who depend on life-saving medication, such as many people with diabetes, are especially vulnerable to the human rights impacts of unaffordable medicine. As part of ongoing research into growing healthcare costs, medical debt, and abusive debt collection practices in the US, this report uses diabetes and access to insulin to describe how US authorities’ regulatory failures have allowed for a crisis of unaffordable drug prices.

As of 2018, nearly 27 million adults in the US have been diagnosed with diabetes, and approximately 8.2 million adults use one or more formulations of insulin to regulate their blood sugar. Without it, people who require insulin may experience high blood sugar, or hyperglycemia, which can lead to serious and even life-threatening complications.

Left unchecked, high blood sugar can kill. In the US, diabetes is the seventh leading cause of death and is the leading cause of renal failure, lower limb amputation, and blindness among adults. Diabetes increases risk of mortality from infections, cardiovascular disease, stroke, chronic kidney disease, chronic liver disease, Covid-19, and cancer, and has the second biggest negative total effect on reducing health-adjusted life expectancy worldwide.

Before the technique for extracting insulin from an animal’s pancreas was discovered in 1921, children with diabetes rarely survived longer than a year after their diagnosis. Over the years, pharmaceutical manufacturers have produced insulin and found ways to improve its effectiveness as a tool for the treatment of diabetes.

But in the US, the most commonly prescribed forms of this lifesaving drug can cost a person more than $300 for a single vial, easily adding up to more than $1,000 a month if they do not have adequate health insurance coverage. As the experiences documented in this report show, the high cost of insulin in the US is not just paid in dollars, but with health, lives, and livelihoods.

The cost of insulin—what an individual must pay to acquire it—is a result of two factors: (i) the price for the drug, and (ii) the degree to which that price is lessened, whether by insurance, charitable assistance, or other forms of cost mitigation.

Based on interviews with 31 people with chronic health conditions about their experiences with the healthcare system, including 18 who have insulin-dependent diabetes, this report focuses on the first factor—the cost of the drug. Drawing from interviews with people who require insulin and experts, extensive data analyses, and secondary literature review, this report describes the human rights impacts of policies that allow drug manufacturers and pharmacies to sell this life-saving medication at unaffordable prices. Forthcoming research will explore the second factor, drawing from interviews with people with chronic health conditions to describe how profound flaws in the health insurance system in the US undermine access to life-saving health care and contribute to the destructive medical debt that affects millions.

The high price of insulin has drawn increased scrutiny of insulin manufacturers’ practices by advocates, lawmakers, and law enforcement officials in recent years. Less discussed, however, has been how the lack of federal regulation has allowed this to occur. As the US Congress considers potential reforms to the system of drug pricing in the US, this report outlines the necessary components of a rights-respecting, drug price-setting system and explores the catastrophic costs of inaction, highlighting the profound impacts of high insulin prices on the lives and human rights of people who require insulin.

The Human Cost of High Analog Insulin Prices

Human Rights Watch conducted price analyses of three of the most widely used insulin analogs: Humalog, Novolog, and Lantus. Each of these drugs is produced by one of the three multinational pharmaceutical manufacturers that collectively dominate the global market for insulin, respectively: the US-based company, Eli Lilly; the Danish company, Novo Nordisk; and the French company, Sanofi.

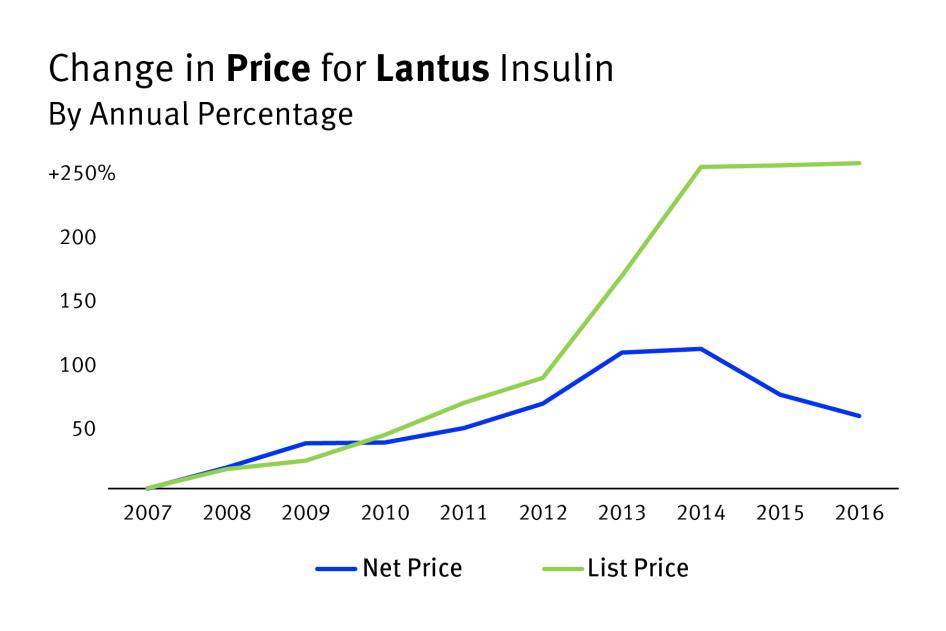

In the US, the prices these manufacturers have set for these drugs—so-called list prices—have soared since their introduction to the market in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

Human Rights Watch analyzed publicly available price information and found that, when adjusted for inflation, Eli Lilly’s list price for Humalog increased by about 680 percent, to $275 per vial in 2018, since it first began selling in the US in 1996. The inflation-adjusted list price for Novo Nordisk’s Novolog rose about 403 percent, to about $289 per vial, between its market entry in 2000 and 2018. Similarly, Sanofi’s list price for Lantus rose about 420 percent when adjusted for inflation since its US market entry in 2000, to about $276 per vial in 2019.

In recent years, these rapid list price increases have slowed or ceased, in a context of increased scrutiny by policymakers, patients, advocates, and the media. But Human Rights Watch found that these still-high list prices have driven up out-of-pocket costs and have adversely impacted the lives of people who require insulin, especially those lacking access to effective cost-mitigation through health insurance or charitable aid.

Almost every insulin-dependent person Human Rights Watch interviewed said they had rationed analog insulin because of out-of-pocket costs, taking it in ways not recommended by their physician in order to stretch their supply. As Skipper’s story and others in this report show, insulin rationing can have damaging and potentially deadly consequences.

High out-of-pocket costs for essential medicines like analog insulin have an inherently regressive impact. All other factors being equal, people with less wealth must pay a much higher share of their income to satisfy equal medicinal needs than wealthier people. In turn, this disproportionate impact can negatively affect the standard of living for people who require insulin, as the money needed to acquire this lifesaving medicine can come at the expense of food, rent, and secure living conditions.

But even people with incomes that do not place them among the lowest paid workers in the country can find themselves unable to afford this lifesaving medicine.

Some of the most economically vulnerable people in the US may qualify for Medicaid, the income-based public health insurance program, or private charitable assistance programs, such as those funded by insulin manufacturers. However, income-based eligibility requirements for these programs can exclude low-income people who may earn too much to qualify, but not enough to afford, private health insurance or the cost of their medicines.

To qualify for Medicaid in 2021, a single person without dependents would need to earn below $17,774 in most states. But in the 12 states that have not adopted the 2010 Affordable Care Act so-called Medicaid expansion, no single-person households without dependents are eligible for this crucial safety net program. More than 2 million uninsured adults fall into this coverage gap nationwide, which disproportionately impacts Black, Indigenous, and other communities of color.

Communities and individuals marginalized from social, political, and economic power in the US are disproportionately impacted both by diabetes and its negative health outcomes. For example, according to 2016 data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, about 356 people with diabetes underwent a lower-limb amputation every day in the US. Black adults in the US, however, were more than twice as likely to experience a diabetes-related amputation than white adults.

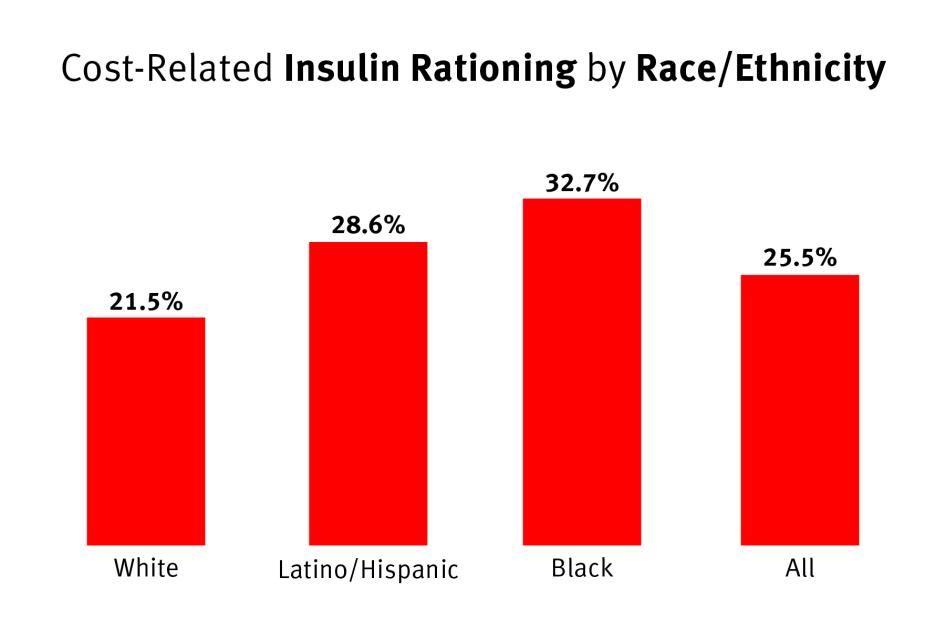

Similarly, a 2017 Yale Diabetes Center survey of 199 people with either type 1 or type 2 diabetes in Connecticut found that one-in-five white respondents rationed insulin in the past year, but were 18 percent less likely to ration insulin than the average. Both Latino/Hispanic and Black respondents, however, were more likely to ration insulin than the average, respectively about 10 and 22 percent more likely.

For many people, charitable initiatives funded by insulin manufacturers are a last line of defense against the high costs of these manufacturers’ products. But eligibility for their programs is limited, typically to US citizens or permanent residents who lack health insurance coverage for medications and have a household income at or below 400 percent of the Federal Poverty Level, or about $51,000 for a single individual.

While these manufacturer-funded initiatives can help lessen the burden of these manufacturers’ high insulin prices for some individuals, they do not present a universal nor sustainable model for addressing cost-related access issues and have clearly fallen short of preventing widespread insulin rationing because of cost.

Additionally, public and private financial assistance programs often restrict aid to US citizens or permanent residents, excluding both documented and undocumented immigrants, many of whom come from communities where diabetes is especially prevalent. Undocumented immigrants are already more than four times more likely to be uninsured than US citizens and are accordingly especially vulnerable to the harmful human rights impact of unaffordable insulin prices.

People who require lifesaving medicines like insulin will pay what they must to survive, regardless of its price. Or, as some of the experiences described in this report show, they will pay for as much as they can afford and hope not to die.

Causes of High Insulin Prices

The drivers of the high prices for analog insulin in the US are clear. Since the 1984 Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act, which established the modern system of federal drug regulations, pharmaceutical innovation and access in the US have relied on the premise that innovative drugs are rewarded with high prices during their window of patent protection, with generic competition quickly reducing prices thereafter.

In contrast to most other countries, the US does not directly regulate drug prices. There are no regulations in place that define a fair price for medicines before they enter the market or restrict how much manufacturers or intermediaries can increase their prices once they do.

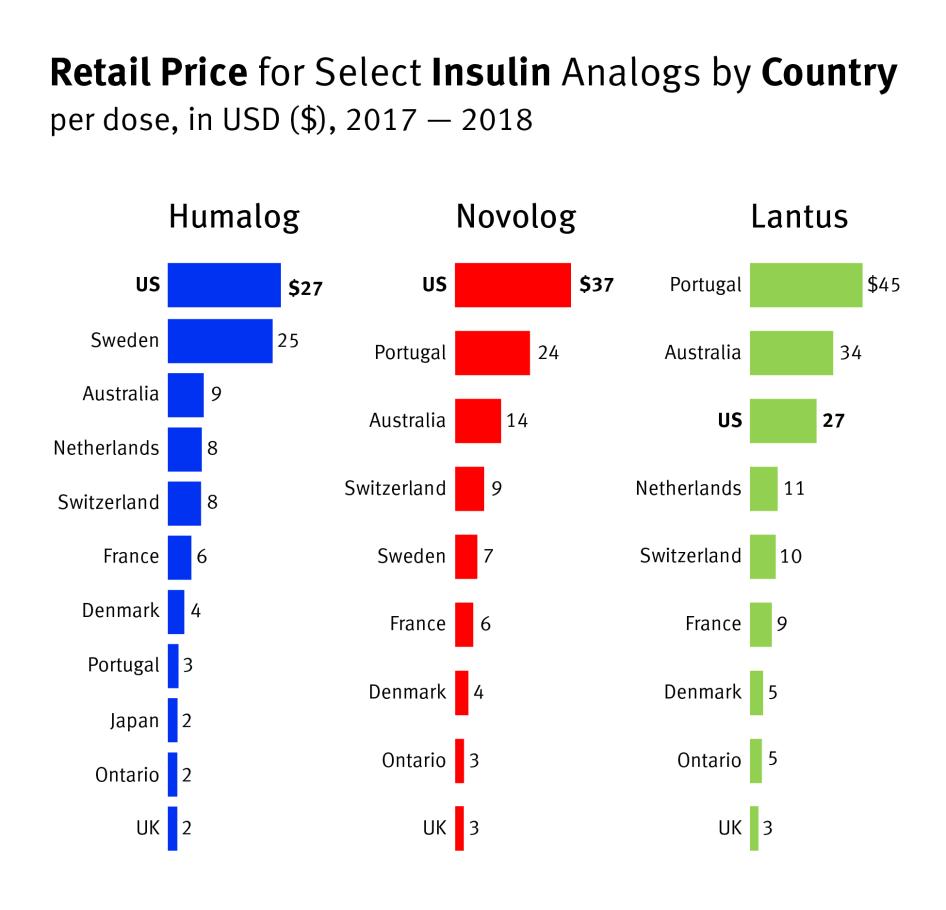

Numerous studies have found that the US is an outlier regarding per capita spending on prescription drugs when compared with other high- and middle-income countries. For example, the US House of Representatives Ways and Means Committee analyzed international drug price data from 2017 and 2018 and found that insulin averaged $34.75 per dose in the US, compared to an average of $10.58 per dose in 11 other high-income countries. According to this study, Humalog’s price was 294 percent higher per dose in the US than the international average, Novolog’s was more than 320 percent higher, and Lantus’ was 75 percent higher.

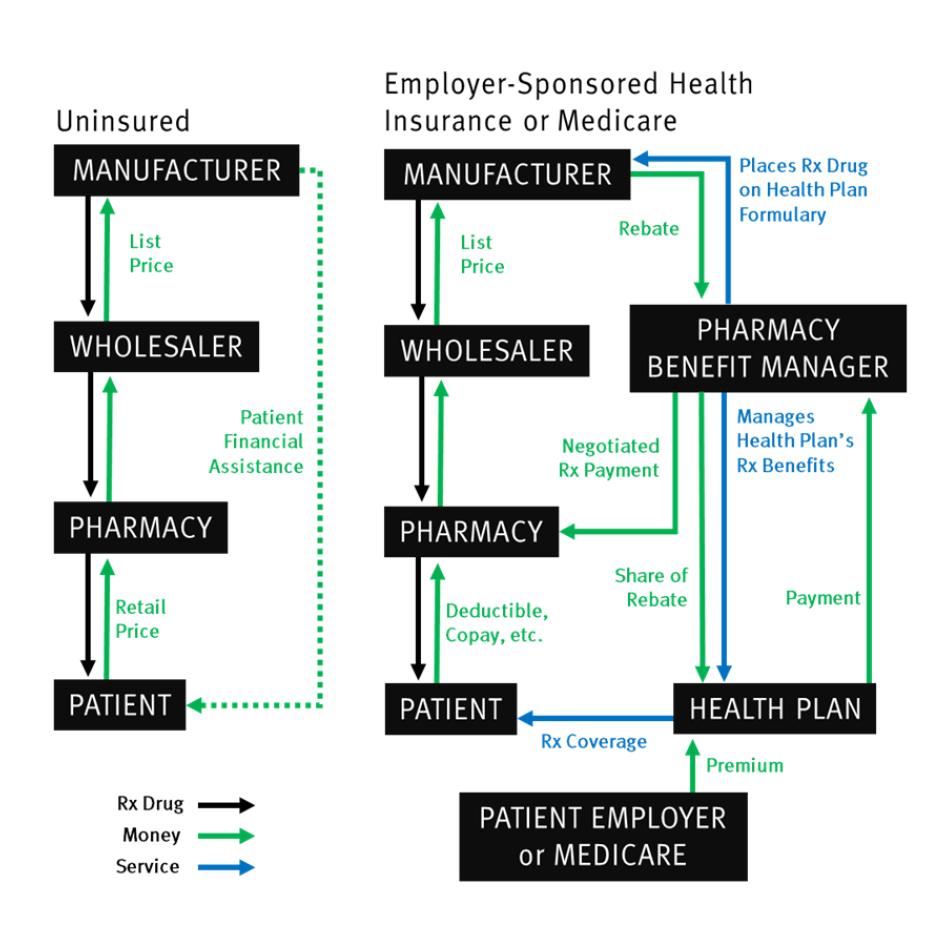

Although unregulated pricing practices allow drug manufacturers to set very high prices, pharmaceutical manufacturers are not the sole drivers of unaffordability. A complicated web of intermediaries in the supply chain between a drug’s manufacturer and purchaser contribute to the cost that individuals with insulin needs must bear to access their essential medicine.

In particular, the opaque system of rebates from drug manufacturers to pharmacy benefit managers (PBM), powerful gatekeepers to health insurance companies’ drug formularies, appears to have created an upward pressure on insulin prices in past years. Manufacturers can lose access to large shares of the US market if their drug is excluded from or given restricted placement on these drug formularies, which service millions of people covered by health insurance plans. As a result, manufacturers of similar types of drugs, such as analog insulin, have competed to ensure that PBMs give their products beneficial placement.

But this competition is done through a largely unseen system of rebates: a negotiated cash payment, calculated as a percentage of the drug’s list price, made by drug manufacturers to the PBMs and the health plans they represent for purchase of their product. This rebate system has allowed insulin manufacturers to compete over the years without sacrificing revenue or lowering the list price of medicines. To offer more generous rebates than their competitors without impacting their bottom line, manufacturers can simply increase the list price for their products.

Some people with health insurance may have never noticed the rapid list price increases documented in this report. But people without insurance or with inadequate insurance, who are much more likely to be from marginalized communities and working low-income jobs, may have had no choice but to bear the burden of their medicine’s ever-increasing cost.

Seen together, this system creates a sequence of regressive subsidies. First, the absence of drug pricing regulations in the US allows insulin manufacturers to price their products far above what is allowed in peer-income countries. Second, within the US, the system of rebates effectively forces many economically vulnerable under- and uninsured people, who do not benefit from any potential discounts stemming from rebates, to subsidize both drug manufacturers’ revenues and other people’s insurance premiums.

Government and Corporate Human Rights Responsibilities

Unregulated pharmaceutical pricing in the US and market practices that incentivize price increases can result in out-of-pocket costs for essential medicines that are so expensive as to undermine their equal and affordable access, a cornerstone of the human right to health. This dynamic disproportionately impacts people based on their economic status and within that group further disadvantages particular racial and ethnic groups in violation of domestic and international law prohibiting discrimination.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), which the US has signed but not ratified, affirm that governments are obligated to ensure that health care, including the provision of essential drugs as determined by the World Health Organization, is accessible to everyone without discrimination and affordable for all. This duty extends to preventing and protecting against human rights harms caused by businesses and other non-state actors, and may include or require effective regulation of their activities.

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which the US has ratified, and the ICESCR prohibit discrimination based on race, property or other status. The International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD), which the US has ratified, also includes specific prohibitions on discrimination based on race, ethnicity, and national origin, among other statuses. Under the ICERD, governments are obligated to act affirmatively to prevent or end policies with unjustified discriminatory racial impacts or effects.

Additionally, the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), which the US has signed but not ratified, both affirms the right to health for people with disabilities and obligates states to provide health services to people with disabilities to minimize and prevent the development of further disabilities. As described in this report, widespread cost-based insulin rationing can contribute to the development of long-term disabilities, such as blindness.

The continued failure of the US government to implement policies to prevent the price increases documented in this report, combined with its failure to take other necessary steps to mitigate healthcare costs, undermines equal and affordable access to insulin analogs, contributes to cost-based medicine rationing, contravenes the right to health, and may be inconsistent with its obligations as a signatory to the ICESCR and CRPD to refrain from acts that would defeat these treaties’ object and purpose.

Companies also have a responsibility under the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights to respect human rights and ensure that their practices do not cause or contribute to human rights abuses. Fundamental to this responsibility is the requirement that companies carry out human rights due diligence to identify the possible, and actual, human rights effects of their operations and establish meaningful processes to prevent, mitigate, and remediate harm when it occurs.

This responsibility extends to all actors in the supply chain between drug manufacturers and consumers, which should address policies and practices that contribute to out-of-pocket costs for insulin that undermine equal and affordable access to the drug.

The Way Forward

The US Congress should enact federal legislation to ensure that essential medications like insulin are, in practice, affordable to all people in the United States who need it, regardless of insurance, wealth, or citizenship status.

Congress should consider legislation to provide insulin to all insulin-dependent individuals in the country free-of-cost. But in the absence of such legislation, and given the inevitability of coverage gaps in existing health insurance systems, Congress should consider legislation to lower and regulate the prices for essential medications like insulin to levels that ensure affordable access and eliminate the de facto discriminatory impacts of drug prices on marginalized groups in the country.

Specifically, in consultation with key stakeholders, the US Congress should draft and enact legislation addressing the many profound flaws with the drug pricing system described in this report, including, among other things: establishing a consultative system to define the fair price for a drug before it enters the market; limiting how much manufacturers and intermediaries can increase the prices of their drugs after drugs enter the market; limiting the price-increasing influence of common industry practices like rebates and discounts; reforming the pharmaceutical patent system to limit abuse and provide for greater access to generics; and increasing transparency throughout the sector.

Federal departments, including the Department of Health and Human Services and Department of Commerce, and relevant agencies, such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, the Food and Drug Administration, and the Patent and Trademark Office, should also implement policies that will help lower prices for lifesaving medications like insulin to levels that ensure their affordable access.

“We are the wealthiest country in the world, but people have to go without medication,” said 29-year-old Emily Grant of Dallas, Texas, discussing the cost of her insulin. “[T]here’s nothing I can do about the trajectory of my illness except follow the treatment plans my doctors tell me. And I don’t think it’s okay to say, ‘Oh well, you either afford it or you die.’”

Glossary

|

Analog Insulin |

A type of insulin that is genetically modified to alter its function within the body and more closely mimic insulin produced by the pancreas. |

|

Authorized Generics |

A non-branded version of a branded drug, produced by the same manufacturer as the branded drug. |

|

Biologic |

A type of drug composed of generally large, complex molecules that is often produced within a living organism or contains components of living organisms. |

|

Biosimilar |

A biologic drug that is highly similar to and has no clinically meaningful differences from an existing branded biologic drug approved by the FDA. Biosimilars are similar to generics but may require additional regulatory approval to be considered interchangeable with a branded biologic. |

|

Copay |

A payment made by a patient with health insurance at the point of sale for a covered service, usually a percentage of the overall cost, as defined by the terms of their health plan. |

|

Deductible |

A specific amount that an insured individual must pay out of pocket towards a specific service before their health insurance provider will begin to provide coverage for that service. |

|

Diabetes |

A chronic health condition that affects how the body produces or responds to the hormone insulin, resulting in abnormal metabolism of carbohydrates and elevated levels of glucose in the blood and urine. |

|

FDA |

The Food and Drug Administration, a federal agency of the US government that, among other things, regulates the safety and quality of food and medicines in the United States. |

|

Follow-on |

A copy of a branded, FDA-approved biologic drug produced by a different manufacturer. If a follow-on version of a biologic drug meets additional requirements, it can become a biosimilar. If a biosimilar meets additional requirements, it can be deemed interchangeable with the original, branded biologic drug. |

|

Formulary |

A list of medicines covered under a health insurance plan, often grouped into tiers that define different levels of cost-sharing. |

|

Generics |

A medication created to be the same as an already-marketed, branded drug in dosage form, safety, strength, route of administration, quality, performance characteristics, and intended use. |

|

Insulin |

A hormone produced within the pancreas of mammals that facilitates the transfer of glucose from the bloodstream into cells. This process is disrupted for people with diabetes, whose bodies may not produce or be resistant to the effects of insulin. |

|

Interchangeable |

A drug that is eligible under FDA regulations to be substituted by a pharmacist for its name brand version without the need for a different prescription, much like how generic drugs are routinely substituted for brand name drugs. This kind of pharmacy-level substitution is subject to state pharmacy laws. |

|

List Price |

The price manufacturers set for their medicine, also sometimes called the wholesale acquisition cost. |

|

Net Price |

The actual amount that a drug manufacturer receives from the downstream sale of a product they have made. |

|

Rebate |

A discount paid to the health insurance company from a manufacturer after the patient has received their medication. |

|

Retail Price |

The price for a drug from a pharmacy if someone pays out of pocket, without any form of cost mitigation, like coupons, discounts, health insurance, or other payment assistance. |

|

Synthetic Insulin |

Human insulin manufactured by inserting the insulin gene into bacteria, which are then farmed and harvested. |

|

Type 1 Diabetes |

An auto-immune, chronic condition in which the pancreas no longer produces any or sufficient insulin. |

|

Type 2 Diabetes |

A chronic condition in which the pancreas does not produce enough insulin and/or cells respond differently to insulin in a way that disrupts the metabolism of sugars. |

Recommendations

To the US Congress

Overarching Recommendation: Reform the US health and drug pricing systems to ensure that essential medicines, including analog insulin, are affordable to all people who need them in the United States, whether through effective regulation of drug pricing or through meaningful cost mitigation and health insurance coverage. In particular, consider legislation to provide insulin to all insulin-dependent individuals in the country free-of-cost. In the absence of such legislation, promptly:

- Develop and implement a system to define the fair price for lifesaving medicines like insulin before they are sold in the US. Such post-approval price controls could take many forms, as seen in the systems discussed in this report that peer-income countries have, such as an international reference pricing system as proposed by H.R.3, the Elijah E. Cummings Lower Drug Costs Now Act.

- Restrict how much manufacturers and intermediaries can increase the prices for essential medicines like analog insulin after they enter the market. Such legislation could take many forms, including direct inflation-caps for drugs that have undergone post-approval price control negotiations or instituting dissuasive financial penalties for manufacturers that increase list prices at rates that exceed inflation.

- Limit the impact that pharmaceutical rebates and discounts can have in driving up list prices. Such legislation should aim to ensure the affordability of medicines and could take many forms, ranging from prohibiting preferential treatment for high-cost drugs with larger rebates, to banning rebates altogether.

- Promote the availability of generics and biosimilars, generally, and limit the ability of secondary patents and authorized generics to impede entry of generic competition. Such legislation could take many forms, including reforms to modernize the 1984 Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act to ensure that patents and market exclusivity periods do not hinder pharmaceutical innovation and access in the US, including allowing earlier generic entry, especially for lifesaving medications, and strengthening the process for challenging so-called weak patents. Ideally, such legislation should also improve mechanisms for patients and the public to provide input in the decision-making around pharmaceutical patents.

- Review and eliminate regulatory barriers to the adoption of interchangeable biosimilars for high-cost medicines, such as insulin analogs.

- Promote the availability and cost-influencing potential of generics, biosimilars and so-called authorized generics, where available. Such legislation could take many forms, such as requiring health insurance formularies to include coverage for authorized generics where the name-brand is also included, and requiring pharmacies to keep lower cost alternatives for any and all name-brand medications available for consumers.

- Require all businesses that influence drug prices to be transparent on costs and prices for medications, including, among other things, pharmaceutical manufacturers’ list prices, net prices, rebate terms, and research and development costs. Additionally, greater transparency is needed around the ways that manufacturer-sourced rebate funds are used and distributed by pharmacy benefit managers and private health insurance companies.

- Improve the affordability and availability of health insurance for low- and middle-income earners. In particular, consider legislation to expand coverage for existing social protection programs like Medicaid and Medicare. In the absence of such legislation, however, Congress should provide a floor of protections for uninsured people who are ineligible for Medicaid in their state but would have qualified had their state adopted the so-called Medicaid expansion. Additionally, Congress should extend existing subsidies for private health insurance plans purchased through the Affordable Care Act marketplace by low- and middle-income earners, which were implemented by the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 but are set to expire in 2022.

To Federal Administrative Agencies

- Federal departments, including the Department of Health and Human Services and Department of Commerce, and relevant agencies, such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, the Food and Drug Administration, and the Patent and Trademark Office, should also implement policies that will help lower prices for lifesaving medications like insulin to levels that ensure their affordable access.

- To better ensure equal and affordable access to essential medicines, federal agencies should expand interagency collaboration, particularly between the Food and Drug Administration and Patent and Trademark Office.

- The Patent and Trademark Office should, to the extent that it is able, facilitate the entry of generic competition, especially for lifesaving medications like analog insulin. This may include strengthening the process for challenging so-called weak patents and reversing policies that grant the agency discretion to deny challenges to possibly invalid patents on procedural grounds. The Patent Trial and Appeal Board should also improve data transparency around decisions relating to so-called Orange and Purple Book Patents.

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention should improve the collection and dissemination of national and state-level data on diabetes-related illnesses and deaths. Additionally, the agency should include disaggregated income data in its annual National Diabetes Statistics Report.

- The Department of Health and Human Services should conduct and publish a study on the administrative feasibility, costs, and benefits of utilizing provisions of the Bayh-Dole Act (35 US Code Chapter 18), including so-called “march-in rights” (§ 203), to foster affordable access to insulin analogs and other unaffordable essential medicines.

To State Governments

- States that have not implemented the Affordable Care Act’s so-called Medicaid Expansion, which, among other things, expands the public health plan’s coverage to single persons without dependents, should adopt legislation to integrate these components of the program into state laws.

- State legislators and agencies should, where possible, similarly pass legislation or policies that help lower prices for essential medications like insulin to levels that ensure their affordable access for all residents. Such legislation could take many forms, including price transparency regulations, state-based affordability review boards, and insulin-specific safety net programs.

To Insulin Manufacturers

- Ensure drug prices are affordable for the most economically vulnerable, such as by lowering list prices to levels that are affordable, including for people without insurance or with inadequate insurance, who are much more likely to be from marginalized communities and working low-income jobs.

- Conduct human rights due diligence to identify and rectify unfair business practices that cause or contribute to the human rights risks of insulin rationing and the two-tiered system of insulin access.

- Periodically publish and update information about list and net prices of all branded drugs and generics.

- If list prices for insulin products are lowered to levels that do not hinder their affordable access, patient assistance programs should operate as comprehensive safety nets for individuals with low socioeconomic status to obtain affordable insulin, including potentially zero-cost insulin. In the absence of such substantive list price reductions, manufacturers should ensure that access to patient assistance programs is both less restrictive and more accessible, including extending benefits to noncitizens and individuals with inadequate insurance, developing rapid access programs for those with an urgent need, reducing time and administrative burdens, and increasing the languages in which applications and evidentiary materials can be submitted.

- Manufacturers should periodically publish and update information about the number of people served, actual amounts and dosage forms provided, and charitable value derived from noncash donations of pharmaceuticals.

- Cease any potential rebate practices that may encourage pharmacy benefit managers to prioritize branded insulin over cheaper, generic alternatives.

- Where resources may be dedicated to physician outreach, inform endocrinologists and other prescribers of insulin about the availability of generics.

To Pharmaceutical Intermediaries

- All intermediaries in the supply chain between pharmaceutical manufacturers and patients, including wholesalers, pharmacy benefit managers, health plans, and pharmacies should conduct human rights due diligence to identify and rectify practices that cause or contribute to the human rights risks of insulin rationing and the two-tiered system of insulin access.

- Health insurance providers should ensure that people with diabetes can access their insulin without undue administrative burden or excessive cost, including ensuring that potential cost-sharing measures for insured people with diabetes should be based on the lowest price available, whether that is the net price or list price. Health plan providers should also ensure that rebate funds directly benefit beneficiaries and regularly publish information relating to rebate agreements.

- Pharmacy benefit managers should develop pricing arrangements with manufacturers that do not result in large annual increases in the manufacturers’ list prices, and should publish information relating to elements of private contracts that influence drug prices, such as terms of rebates and discounts.

- Pharmacies should consider lowering their markup over acquisition cost for high-price drugs, in order to prevent unnecessary cost inflation that can contribute to the undermining of equal and affordable access to medicines. Additionally, they should publicly publish information relating to acquisition costs and retail prices.

Methodology

This report is based on interviews, data analysis, and other secondary research conducted between March and July 2021 as a part of ongoing research into growing healthcare costs, medical debt, and abusive debt collection practices in the United States.

Human Rights Watch interviewed a total of 50 people in the US for this research, including 31 individuals with chronic health conditions. The remaining 19 were experienced professionals or activists including practicing physicians; researchers or organizers from nonprofit healthcare access advocacy organizations; academic researchers covering domestic and international healthcare economics, drug pricing, and insulin access; a reporter covering medical debt; and a hospital administrator.

Of the 31 people with chronic illnesses with whom we spoke:

- Twenty-five routinely depend on medicines for treatment of chronic health conditions; 18 of them have insulin-dependent diabetes—13 with type 1 diabetes and five with another major chronic health concern in addition to diabetes.

- Eighteen identified as women, 11 as men, and two as gender non-binary. Three individuals with whom we spoke were in the process of or had already transitioned genders. Of the 18 insulin-dependent individuals, nine identified as women, seven as men, and two as gender non-binary.

- Three identified as Black, all of whom had insulin-dependent diabetes; one person identified as Latinx, who also had insulin-dependent diabetes.

- Three lived in each of New York, North Carolina, Indiana, Texas, and Minnesota; two lived in each of Connecticut, Ohio, Colorado, Pennsylvania, and Washington; and one lived in each of the District of Columbia, West Virginia, Rhode Island, Iowa, Florida, and the United Kingdom. The people who require insulin with whom we spoke lived in Florida, Washington, Connecticut, North Carolina, Texas, Minnesota, New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, Rhode Island, or the United Kingdom.

Most interviews with people who require insulin were arranged with help from partner organizations, including Patients for Affordable Drugs, T1International, and Mutual Aid Diabetes. These interviews reflect a range of personal experiences shaped by different state policy environments, private and public insurance programs, income levels, and racial, gender, or sexual identities.

This report focuses on the experiences shared by the 18 people with whom we spoke who depend on insulin to regulate their blood sugar. However, many of the concerns covered in this report that contribute to issues of access and affordability for insulin, including US policy regarding drug pricing, are relevant to, and consistent with, the experiences of each of the 25 medicine-dependent people Human Rights Watch interviewed.

All those interviewed provided verbal informed consent to participate and to have their names and the contents of their interviews reproduced. Where relevant, some individuals requested anonymity to discuss certain subjects. Human Rights Watch notes such incidences in the footnotes of this report when citing to these interviews. No person interviewed received any compensation for their participation.

The number of people we interviewed who require insulin does not constitute a representative sample of all people with insulin-dependent diabetes nationwide. However, their experience is consistent with independent studies, extensive secondary research and data analysis that support a pattern of problems discussed in the report, providing insights for much-needed regulatory reforms.

Because of the Covid-19 pandemic, all interviews were conducted remotely by videoconference or telephone. Every interview was individual, except for two group interviews: one with two individuals who work with the organization, Mutual Aid Diabetes, both of whom have type 1 diabetes; and one with two researchers from a US-based medical school, who are among the 19 professionals consulted for this research.

In addition to interviews, this report draws extensively on publicly available secondary sources of information to corroborate and interpret the experiences of those with whom we spoke, including reports from nongovernmental organizations, federal investigations, publicly released and redacted internal company documents, government and academic studies, publicly available data from federal departments and agencies, medical literature, and relevant local and national reporting. Where relevant, the methodology for charts and data are explained in the footnotes.

Human Rights Watch also conducted price analyses of three of the most widely used insulin analogs: Humalog, Novolog, and Lantus. Each of these drugs is produced by one of the “Big Three” multinational pharmaceutical manufacturers that together control 96 percent of the global market for insulin by volume: the US-based company, Eli Lilly; the Danish company, Novo Nordisk; and the French company, Sanofi. The price analysis component of our research covers these three brands because these were most commonly used and raised by interviewees. Where interviewees or literature discussed other available synthetic human insulins, Human Rights Watch explicitly notes that in the relevant section.

Almost every person with diabetes whom we interviewed was currently using, or had previously used, either Humalog or Novolog, two of the three insulins included in this report, with many having switched between them at some point because of changes in health insurance coverage. Five were currently using or had previously used Lantus, a third brand of insulin that is included in our study.

Human Rights Watch wrote letters to six large companies involved in the insulin supply chain: three manufacturers of the insulins covered in this report, Eli Lilly and Company, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi; and the three largest pharmacy benefit managers in the United States at time of writing, CVS Health, OptumRx (owned by UnitedHealth Group), and Express Scripts (owned by Cigna). These letters requested information and clarification regarding their practices. Of the six companies we contacted, five provided written responses, including all three manufacturers. Their responses are reflected throughout the report, including in some places to provide important contextual information about industry policies and practices. The complete correspondence with these six companies can be found in an online Annex to this report.

Throughout this report, we also cite to publicly available information provided by these companies, both regular public disclosures and internal documents released following a 2020 Senate Finance Committee investigation.

I. Background

No matter what, you have to pay your rent first. But if I’m out of insulin, I’m going to die. So, I stopped paying rent and got evicted. I was homeless. But I never slept on the streets—I was staying with people. But I didn’t have a legal residence for a few years.[1]

— Zoe Witt, type 1 diabetic, Washington, May 12, 2021.

Zoe Witt of Seattle, Washington, left a salaried job with health insurance that covered her insulin needs in 2018 because of the work’s impact on her mental health. “I was suicidal, and I knew I needed to quit the job,” she said. “I quit, which I had never done before because I’m a diabetic and I need health insurance.”[2]

Soon after, she found work as a host in a restaurant, earning about US$13 an hour plus tips. But the position did not include health insurance coverage. Despite picking up extra shifts and working overtime, Zoe’s take-home pay was about $2,200 a month, making her ineligible for Washington State’s Medicaid program.[3] But after paying for rent in a high-cost-of-living area, student loans, utilities, credit card debt, and food, Zoe could not afford to purchase private health insurance either.

Witt told Human Rights Watch that each month she required one vial of both Lantus and Novolog, two commonly prescribed brands of analog insulin. But without insurance, the out-of-pocket cost for her prescribed insulin was about $600 a month, more than a quarter of her take-home pay at that time.[4] So, Witt started stretching her medication and using expired insulin:

It was a very bleak time. I definitely remember feeling really ill.... You think, ‘I haven’t died yet.’ But that whole time, you could be moments from death. And when your blood sugar is that poorly controlled, you are way more at risk for other health issues. And if you don’t have insurance, you are way less likely to go to the hospital if something goes wrong…. I would be throwing up in the middle of a shift in the bathroom at work. Looking back, it was like I was dying.[5]

Her out-of-pocket costs for insulin began to add up. Zoe skipped paying rent to afford her medication, got evicted, and moved in with acquaintances. This continued for almost a year before she was offered a promotion to a position that paid $19 an hour, which allowed her to purchase health insurance.[6]

But the impacts of insulin rationing can be long-lasting.[7] Only months after speaking with Human Rights Watch, Zoe had surgery for an advanced form of diabetic retinopathy and a partially detached retina, common complications of prolonged high blood sugar.[8]

Witt’s story shows some of the struggles that people with insulin-dependent diabetes can experience when their insulin is unaffordable. Lack of affordability endangers their lives and health and deeply impacts their choice of career, performance at work, housing, and overall standard of living.

As of 2018, nearly 27 million adults in the United States have been diagnosed with diabetes, and approximately 8.2 million adults—about 2.5 percent of the total population—use one or more formulations of insulin to regulate their blood sugar.[9] Diabetes disrupts how insulin, a naturally occurring hormone produced by the pancreas, transfers glucose from the blood stream into cells.[10] Type 1 diabetes (T1D) is an auto-immune condition in which the pancreas no longer produces any or sufficient insulin.[11] Type 2 diabetes (T2D), which affects more than 90 percent of people diagnosed with diabetes in the US, occurs when the body is either resistant to the effects of insulin or does not produce enough.[12]

Many people with T2D and all people with T1D depend on externally supplied insulin. Without it, people who require insulin may experience high blood sugar, or hyperglycemia, which can lead to serious and even life-threatening complications.[13] Left unchecked, high blood sugar can kill.[14]

Diabetes is one of the top 10 causes of death around the world and insulin access and affordability is an urgent concern for millions of people living in lower- and middle-income countries. [15] But despite the immense wealth and pharmaceutical production capacity of the US, the country severely underperforms relative to high-income peer nations at ensuring that the medicines needed to effectively manage this disease are affordable.[16]

Since their introduction in the mid-1990s, genetically engineered human insulin analogs (analog insulin) have become the dominant type of insulin prescribed and used in the US, accounting for more than 80 to 90 percent of insulin units used in recent years.[17] Whether analog insulins are generally more effective than older insulins remains a subject of debate in medical literature reviewed by Human Rights Watch, particularly when their cost is considered, but they are far more convenient for patients to regularly use.[18]

Three of the most common name-brand analog insulins are each made by a different manufacturer: Humalog (insulin lispro), made by the US-based Eli Lilly; Novolog (insulin aspart), made by the Denmark-based Novo Nordisk; and Lantus (insulin glargine), made by the France-based Sanofi.[19]

Humalog and Novolog are known as rapid-acting insulins, which quickly reduce blood sugar once introduced into the bloodstream.[20] Lantus is prescribed as a long-acting insulin, which can regulate blood sugars for up to 24 hours and is often used alongside other faster-acting insulins.[21]

These analog insulins are the flagship insulin products for each of these three companies, which controlled 99 percent of the global human insulin market by value and 96 percent of the market by volume in 2016.[22]

Purchasing these drugs from a pharmacy without adequate health insurance coverage or charitable aid in the US can cost more than $300 for a single vial out-of-pocket. But patients with T1D typically require two or three vials of insulin per month, and some patients who are more resistant to insulin, including some with T2D, may need up to six or more vials per month.[23] As described below, these out-of-pocket costs are largely driven by insulin manufacturers’ list prices, which the government does not regulate.

US Analog Insulin Prices

In the US, drug prices are not static, but vary day-to-day, place-to-place and person-to-person. When someone goes to a pharmacy to purchase a drug that is medically prescribed, the out-of-pocket price they must pay for that drug can be influenced by a complicated web of contractual relationships, discounts, and rebates between numerous private intermediaries involved in the supply chain between the drug manufacturer and the patient.[24]

We wrote letters to the three insulin manufacturers included within the scope of this report, requesting information on, among other things, point-of-sale out-of-pocket cost data for their products. Neither Sanofi nor Novo Nordisk provided data responding to this specific request.[25] In its response, Eli Lilly wrote that:

Today, anyone is eligible [under the Lilly Insulin Value Program] to purchase a monthly prescription of Lilly insulin for $35, whether they use commercial insurance, Medicare Part D, Medicaid, or have no insurance at all…. The average monthly out-of-pocket cost for a prescription of Lilly insulin has dropped 27 percent, to $28.05, over the past four years … [the] average monthly prescription of Humalog is 3.3 vials … [and] the average monthly out-of-pocket cost translates to $8.50 per vial.[26]

Eli Lilly’s response to Human Rights Watch did not make clear how many people have been helped through initiatives like the Lilly Insulin Value Program, which was created in 2020 in response to the Covid-19 pandemic, or for how long it will be offered.[27] But these average cost data provided by Eli Lilly include the experiences of people with adequate health insurance and other forms of cost assistance like direct financial aid, and may not reflect the experiences of those who lack such benefits and must pay out-of-pocket for the pharmacy’s full retail price, known as the retail cash price.[28]

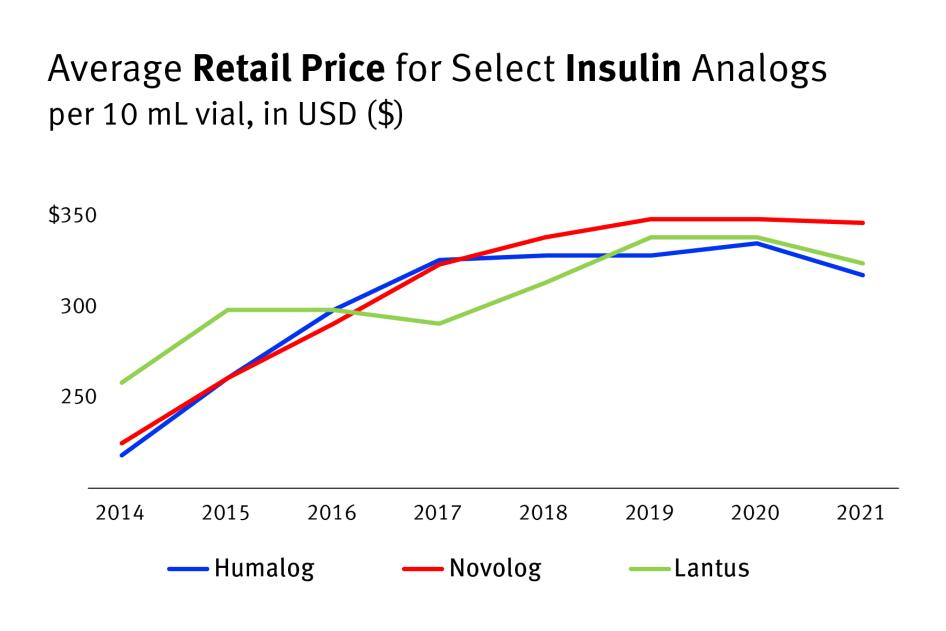

Human Rights Watch analyzed retail cash price data from GoodRx, a website commonly used by patients that tracks prescription medication costs and discounts, to create yearly average retail cash price estimates for a 10 mL vial of these three prevalent analog insulins from 2014 to 2021, all years for which this data is publicly available.[29]

According to these GoodRx data, the retail cash price for a 10 mL vial of Humalog increased by more than 45 percent between 2014 and 2021, to about $319 a vial.[30] Novolog increased by more than 53 percent, to about $348 a vial.[31] Lantus increased at a lower rate, 25 percent, as the average price was already higher in 2014, but sold for about $325 a vial in 2021.[32]

Chart 1: Retail Cash Prices for Select Analog Insulins (10 mL vial) Increased Since 2014

Yearly Average Retail Price for Select Insulin Analogs (10 mL vial) from 2014 to 2021

As the GoodRx pricing information indicates and Zoe’s story shows, these out-of-pocket costs can quickly add up, especially for people with low incomes.

Drug wholesalers and pharmacies can contribute to these retail cash prices by marking up the price of a drug before it is dispensed to a patient.[33] But the impact of these practices on retail cash prices is limited, as the underlying price that manufacturers set for their drugs—the so-called list price—largely determines the out-of-pocket costs for patients without insurance or assistance.[34]

A number of studies by healthcare economists, advocacy organizations, and federal oversight bodies have documented how these list prices for insulin analogs in the US have rapidly increased since their introduction to the market in the late 1990s and early 2000s.[35]

Human Rights Watch wrote letters to the three insulin manufacturers included within the scope of this report, requesting historic list price data for the three drugs we studied. Their responses, reproduced in full in the Annex to this report, did not provide this data.[36]

Accordingly, we compiled list price data from available sources, including public disclosures by these manufacturers and internal company documents provided to a recent US Senate Finance Committee investigation.[37]

In 1996, Eli Lilly first sold Humalog in the US at a list price of just over $21 for a 10 mL vial, equivalent to about $35 in 2020 when adjusted for inflation.[38] By 2020, however, Humalog’s list price was about $275—a 680 percent inflation-adjusted increase.[39] This increase was 10 times faster than inflation in the general economy and nearly 6 times faster than price inflation in the pharmaceutical sector specifically over this same time period.[40]

After Novo Nordisk’s Novolog and Sanofi’s Lantus were both approved for sale in the US in 2000, their list prices similarly soared past the price inflation for goods and services in other sectors of the economy.[41] Between 2001 and 2018, the most recently available list price data Human Rights Watch was able to gather, Novolog’s list price rose about 403 percent when adjusted for inflation, from about $59 a vial to more than $289.[42] Similarly, between 2001 and 2019, the list price for Lantus rose about 420 percent, from an inflation-adjusted price of about $53 per vial to more than $283.[43] These list price increases for both brands vastly outpaced the price inflation experienced by the entire prescription drug sector during this period, which only grew by 77 percent between 2001 and 2020.[44]

Production Costs and List Price IncreasesAvailable information indicates that these high prices and drastic price increases for analog insulins are not primarily driven by the cost to produce these products. For example, the French insulin manufacturer Sanofi provided data to a US Senate Finance Committee investigation of insulin pricing practices in 2019.[45] In these documents, Sanofi stated that the per-unit manufacturing cost for a 10 mL vial of Lantus in 2018 was $3.61.[46] But that same year, their list price for a 10 mL vial of Lantus was over $266—a markup of several thousand percent.[47] These documents from Sanofi also revealed that, between 2014 and 2018, their list price for Lantus increased at a rate about three-times faster than the cost to manufacture Lantus. According to these records, the per-unit cost of manufacturing Lantus increased by only 5 percent in total between 2014 and 2018.[48] Meanwhile, Sanofi’s average list price for a 10 mL vial of Lantus grew by a total of 15 percent over this period, from about $230 to $266.[49] Not all of this markup is profit, as other costs are involved in bringing a vial of insulin to market, including substantial rebates discussed further in Section III. For example, a 2017 study by researchers from the University of Southern California’s Leonard D. Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics estimated the average net profit margins—the percent of total revenue that is profit—for each of the different actors in the US pharmaceutical supply chain: manufacturers, wholesalers, pharmacy benefit managers, pharmacies, and insurers.[50] They found that, on average, nearly a third of drug manufacturers’ revenue from US-based sales of branded and generic drugs compensated for direct production costs, but 26.3 percent of their revenue was profit.[51] US law currently does not require pharmaceutical companies to disclose drug production costs and companies do not typically publish this information. Accordingly, it is unclear to what degree other costs, in addition to manufacturing, may have influenced the list prices of these analog insulins. Human Rights Watch wrote to the three insulin manufacturers included in this report requesting data on, among other things, gross and per unit manufacturing costs for the insulin analogs covered in this report. Their responses, reproduced in full in the Annex to this report, did not provide this information. |

In recent years, the rapid list price increases documented in these data have slowed or ceased, in a context of increased scrutiny by policymakers, patients, advocates, and the media.[52]

In letters to Human Rights Watch, the three insulin manufacturers we studied described different institutional responses to this scrutiny.[53] Since 2016, Novo Nordisk wrote, the company has been “limiting any potential list price increases on medicines to no more than single digit percentages annually.”[54] Similarly, Eli Lilly wrote that the company has not increased the list price for any of their insulin products since 2017.[55]

However, slowing or stopping additional price increases does not ameliorate the negative human rights impacts of already high list prices on the health, lives, and livelihoods of people who cannot afford their medicine.[56] As the experiences of other peer-income nations discussed below show, these high prices are unique to the US among other peer income countries and reflect addressable policy failures.

Comparing US Prices Internationally

Travis Paulson, age 48, of Northern Minnesota, uses several vials of Novolog each month to manage his T1D. He described regularly traveling to Canada to buy Novolog, where a six-month supply costs around US$700, about the price of two vials in the United States.[57]

Buying insulin across the border, where Novolog is more than 92 percent cheaper per dose than in the US, has allowed Paulson to avoid having to ration his insulin—taking it in amounts or manners not recommended by his physician to stretch out his supply—as he did in the past.[58] It has also allowed him to buy surplus insulin supplies that he can share with people in need.[59]

“We’ve seen enough people die,” said Paulson, explaining the motivations of people with diabetes who participate in informal aid networks, which work to ensure access to insulin for those who cannot afford it. “It’s more important to give people what they need,” he said. “If we find out that they are rationing, we send someone out to their house with a few vials.”[60]

But not everyone in the US has access to cheaper medicines purchased abroad.[61] People without the means to access these cheaper international alternatives, in turn, must confront expensive US prices.

Numerous studies have found that the US is an outlier regarding the high cost of per capita spending on prescription drugs when compared with high- and middle-income countries.[62] A 2021 Rand Corporation study found that US drug list prices were 256 percent of the combined average for 32 other countries in the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).[63] Similarly, a 2020 Rand Corporation study commissioned by the US Department of Health and Human Services found that analog insulin list prices in the US were more than 8 times the average across 32 other OECD countries.[64]

In 2018, the US House of Representatives Ways and Means Committee compared the per-dose list prices of 79 different drugs sold in the US to their list prices in 11 other high-income countries.[65] Their study found that drug prices in the US were nearly four times higher than the average price of the same drug abroad, with some drugs 67 times more expensive.[66]

The prices for the three analog insulins we examined—Humalog, Novolog, and Lantus—largely follow the general trend in US drug prices documented in this study, which are far above those in other high-income countries.

According to the House Committee’s data from 2017 and 2018, Humalog’s price was 294 percent higher per dose in the US than the international average.[67] Novolog was more than 320 percent higher.[68] Lantus is a rare example of a drug that was more expensive in several other countries studied by the House Committee, but it still cost 75 percent more in the US than the average price for the same drug abroad.[69]

Chart 2: Same Drug, Exorbitant Prices in the US

Select insulin brands’ per-dose list prices were much higher in the US in 2017-2018 than in other countries or regions.

II. The Human Cost of Unaffordable Insulin

We all deserve to live a fulfilled life [but] I don’t see how anyone is able to do that if you have to worry about [either] paying the bills or getting your medicine.

— Sa’Ra Skipper, person with type 1 diabetes, Indiana, June 1, 2021

Insulin Rationing and Diabetes Deaths

Of the 18 people Human Rights Watch interviewed who require insulin, 14 said they have rationed their insulin because of its high cost, taking it in amounts or manners not recommended by their physician to stretch out their supply.[70]

It is difficult to fully quantify how many people have to ration insulin because of costs. Nonetheless, four studies conducted between 2018 and 2021 suggest high rates of insulin rationing in the US and its potentially severe consequences.[71]

A September 2021 study of survey data collected by the advocacy organization T1International found that more than 25 percent of 542 US-based respondents rationed insulin in the past year due to cost.[72] In 2020, the American Diabetes Association estimated that about 650,000 insulin patients were skipping injections or taking less insulin than prescribed.[73] A 2019 survey by researchers at the Yale School of Medicine found that 25 percent of 199 respondents reported underusing prescribed insulin because of the cost within the past year.[74] Similarly, a 2018 American Diabetes Association survey of 535 individuals with diabetes found that 26 percent of respondents regularly took less insulin than prescribed in the past year because of the cost.[75]

“I did it in the past,” said Travis Paulson, age 48, of Minnesota, recalling a prolonged period of insulin rationing after losing his job during the economic recession in 2007.[76] Travis told Human Rights Watch that he has had dozens of eye operations over the past decade to repair damage that he attributes to his insulin rationing.[77] Still, he counted himself lucky to have survived:

I didn’t know you could die from it. I thought that if you went without insulin, you would go blind, lose fingers, toes, or your legs. I was wrong. It may take months for those things to happen, but if you go without insulin for even one night, you can die.[78]

Timely and regular access to insulin is a matter of life or death for people who require it.[79] But it is especially so for the roughly 1.4 million people in the US with T1D, whose bodies do not produce any insulin at all.[80] Without insulin, people with T1D can experience dangerous health complications, including potentially lethal spikes in blood sugar.[81]

The total number of people in the US who die because of an acute hyperglycemic crisis, such as diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), is unclear.[82] In 2020, the medical journal Diabetes Care published a study of national hospitalization records from 2017, which found that 835 people died after being admitted into a US hospital with a primary diagnosis of DKA that year—nearly 70 people each month.[83]

But these numbers may underestimate the total number of DKA deaths in the US, since this inpatient hospitalization data does not capture deaths that occurred at home or in an emergency room, for example.[84]

“A lot of people get too sick to even get out of bed and they just die,” said Paulson, who participates in an informal aid network that works to ensure access to insulin for those who cannot afford it. “They ration or go without, and they just go to sleep and never wake up.”[85]

Memorials written by family members and published by the organization T1International describe tragic stories of people finding their loved one with T1D dead after rationing their insulin because of its cost.[86]

As many of these memorials illustrate, the dangers of unaffordable insulin are compounded by the high cost of seeking medical care in the US. Danielle Hutchinson, age 27, of Charlotte, North Carolina, explained how medical debt from previous hospital visits has caused her to delay medical care:

Usually, by the time I am in the hospital [it’s] because I’m [already] at DKA…. I don’t want to deal with the hospital costs, so I try to prevent it and reverse the process myself and drink fluids and keep stuff down [but in] the moment, you don’t have the luxury to think about complications because you are more worried about not running out [of insulin].[87]

Allie Marotta, a 27-year-old with T1D who works with Mutual Aid Diabetes, an online-based mutual aid network that raises money for people struggling to afford their diabetes costs, despaired at how often people ration insulin and even die. “[W]e see people who have an urgent need, [but] it was late, and they passed away,” she said. “The toll is death for our community.”[88]

Disparate Burdens for Economically and Socially Marginalized Groups

Imagine you don’t have someone to loan you $250, and you die alone in your living room. But nobody is doing anything about it.... it ticks me off to no end.

— Marcus LaCour, person with type 1 diabetes, Ohio, May 26, 2021.

Marcus LaCour, a 35-year-old with T1D from Ohio, described a period when he frequently moved between jobs, changing employer-sponsored health insurance programs, many of which did not adequately cover the cost of his insulin. After exhausting a stockpile of Novolog pens he had slowly saved up, each of which cost about $250 at the time, Marcus started relying on free samples from his doctor.[89]

LaCour said his family’s financial circumstances were dire: “My wife said that she would skip meals to help with the insulin costs.... That’s hard to hear, but I [knew] that I [had] to survive.” For about a year, Marcus managed largely by rationing free insulin product samples from his physician. But one day, his doctor ran out.[90]

Rationing his last insulin pen, LaCour recalled receiving a bill from his pharmacy for US$736. “I call my doctor and he has no more samples,” he said. “I call the insurance company and say that I’m down to my last pen and you all are going to screw me ... There’s no way I can get $730 right now. How am I supposed to get my meds?”[91]

LaCour said that his health insurance provider at the time offered him an appeals process that would have taken 10 days. But before he ran out of insulin, his employer came to his aid:

Had it not been for the fact that my boss loaned me $250 to get an insulin pen, something bad would have happened. At the time, I was making like $23,000 a year [and] I didn’t have any credit cards. So, there was no way for me to put anything on credit. You suffer.[92]

High out-of-pocket costs for essential medicines like analog insulin are inherently regressive, as people living in or near poverty will always pay more, as a share of their income, to satisfy equal medicinal needs than higher-earning people will, unless those costs are mitigated by public or private assistance, like Medicaid.[93]

In turn, this disproportionate impact on economically vulnerable individuals threatens the right to an adequate standard of living for people who require insulin, as the money needed to acquire this lifesaving medicine can come at the expense of food, rent, and secure living conditions.[94]

Communities deprived of social, political, and economic power in the US because of systemic racism or other forms of discrimination are especially impacted by diabetes.[95] Age-adjusted prevalence data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) shows that diabetes is highly prevalent among the most socioeconomically vulnerable communities in the country, affecting nearly one-in-seven American Indian or Alaskan Native adults and around one-in-eight non-White Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black adults in the US.[96] In contrast, only about one-in-thirteen non-Hispanic, white adults have diabetes.[97]

This disparity in diabetes prevalence is largely driven by T2D, which is much more common among Black, Indigenous, and other communities of color in the US than among the non-Hispanic white population.[98] In turn, this high prevalence reflects the interrelated political, economic, and cultural drivers of socioeconomic marginalization, which shape the social determinants of health—the circumstances in which people are born, live, work, and age.[99]

But disparities based on race and ethnicity are not just reflected in the prevalence of diabetes, they are also reflected in its severity.[100] Black adults, for example, are more than twice as likely as white adults to be hospitalized for DKA.[101] Additionally, while about 356 people with diabetes underwent a lower-limb amputation every day in the US in 2016, Black adults were more than twice as likely to experience a diabetes-related amputation than white adults that year.[102]

Data from a 2017 Yale Diabetes Center survey of 199 people with either T1D or T2D in Connecticut also suggests that the burden of high insulin costs is also borne differently by different racial and ethnic groups.[103]

Although more than one-in-five white respondents rationed insulin in the past year, they were 18 percent less likely to ration insulin than the average.[104] Both Latino/Hispanic and Black respondents, however, were more likely to ration insulin than the average, respectively about 10 and 22 percent more likely.[105]

Chart 3: Cost-Related Insulin Rationing by Race or Ethnicity

One-in-three Black survey respondents rationed insulin, as did more than one-in-four Latino or Hispanic respondents. White respondents were less likely to ration.

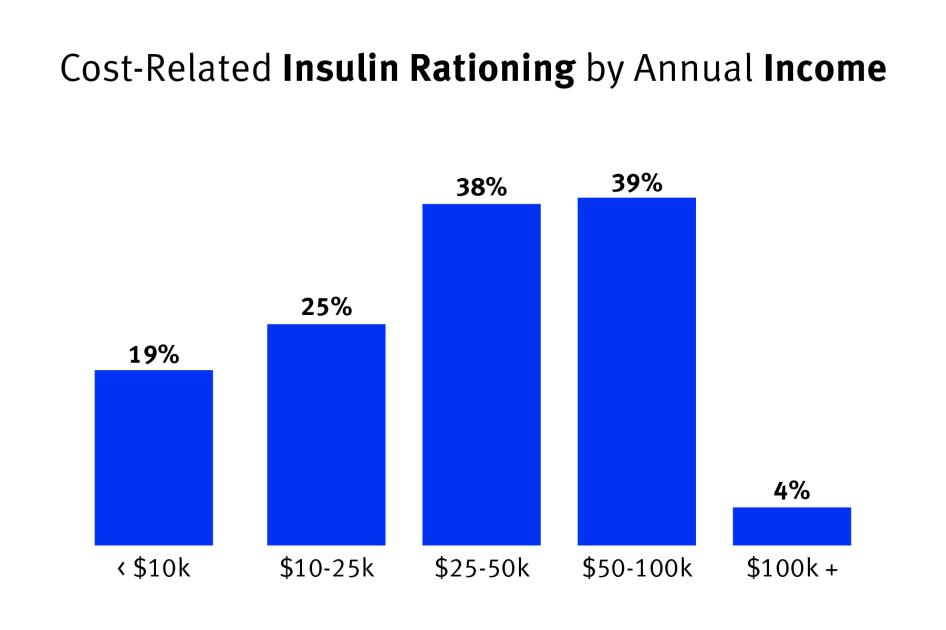

This study also found that patients with lower incomes were more likely to report cost-related underuse.[106] However, the rate of cost-related insulin rationing did not appear to scale linearly with income.[107] Of people earning under $10,000 a year, about 19 percent rationed insulin; this share rose to 25 percent for those earning between $10,000 to $25,000, and then to about 38 percent among individuals earning between $25,000 and $100,000.[108]

The increased incidence of insulin rationing for low and middle-income earners documented by this survey may reflect gaps in coverage for means-tested social health care programs, as those who did not fall in the lowest income brackets, and thus did not qualify for a potentially more robust publicly funded health plan, were more likely to ration insulin.[109]

Chart 4: Cost-Related Insulin Rationing by Annual Income

Middle-Income Respondents Most Likely to Ration Insulin Because of Cost

Some of the most economically vulnerable people in the US may qualify for Medicaid, the income-based public health insurance program. But income-based eligibility requirements for these public assistance programs can exclude many low-income people who may earn too much to qualify, but not enough to afford private health insurance or the cost of their medicines.[110]

To qualify for Medicaid in 2021, a single person without dependents would need to earn below $17,774 in most states.[111] But in the 12 states that have not adopted the 2010 Affordable Care Act’s so-called Medicaid expansion, no single-person households without dependents are eligible for this crucial safety net program.[112] More than 2 million uninsured adults fall into this coverage gap nationwide, which disproportionately impacts people of color, and especially Black Americans.[113]

In 2017, when the Yale survey was conducted, the national Federal Poverty Level (FPL) for a single-person household was $12,060.[114] That year, Connecticut had a Medicaid income limit for a single-person household without dependents of 138 percent of the FPL, or $16,642.[115] Survey respondents who earned below this cut-off may have been eligible for free insulin through Medicaid. But those who earned more than this income limit were more likely to depend on private health insurance, whether employer-sponsored or self-purchased.

People stuck in this limbo, with an income too high to qualify for income-based public health insurance but too little to afford private insurance, may face unaffordable insulin costs.[116]

Both Sa’Ra Skipper, 25, of Indianapolis, Indiana, and her sister have T1D. Skipper told Human Rights Watch about how her sister purposefully worked lower-paying jobs to qualify for Medicaid and other cost assistance programs, because slightly higher-paying jobs did not pay her enough to afford health insurance that covered her medical expenses. “She gets her insulin covered, but she still doesn’t make a living wage,” Skipper said.[117]

In 2018, Skipper was working a job with health insurance that did not cover her insulin, leaving her with monthly out-of-pocket costs of about $1,000, which she was not able to afford. But Skipper’s sister, who was receiving free insulin from Medicaid, rationed her medicine to share with Skipper. “It felt like I was taking from her,” Skipper said. “We were sharing insulin out of the same vial ... But the system [didn’t] give me any other choice but to make me live this way.”[118]

The consequences were devastating. Skipper described what happened in written testimony to the US House of Representatives Committee on Oversight and Reform in 2019:

One night, I take my night time dose of insulin and leave the vial on the dresser for my sister to see. I assumed that she would think that I had already taken my dose since I left the vial on the dresser, but she didn't.... She thought that I still needed to take my insulin for the evening, so she took less than her normal dose to ensure that there was enough left for me to take. She put herself at risk.... The next day she went into diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) and had to be hospitalized for 4 days. The veins blew in her body so she had to have a [venous catheter inserted] in her neck and almost went into a diabetic coma.[119]

Skipper watched her sister battle for life: “We almost lost my sister. That was a really tough time, to see my sister laying in a hospital bed because she was just trying to help me out ... she kept me alive.”[120]

The Power of “Good” Insurance

Insurance is always something I think about. With changing jobs, with possible career paths, with who and when I marry.

— Sydnee Griffin, type 1 diabetic, Minnesota, July 7, 2021

Each of the 31 individuals with chronic health conditions Human Rights Watch interviewed described how critical health insurance that offered adequate and affordable coverage for their condition, or the lack of it, was to their lives. For people who require insulin, the need to ensure health insurance that effectively covers usual medical expenses has profound and under-reported impacts on life choices.

“I had to stay in an abusive situation in order to keep my insurance under my father,” said an individual who did not wish to be named as they shared their experiences publicly for the first time.[121] They described how the need to maintain health insurance coverage to afford treatment for their T1D kept them in an abusive household:

I know other people who have been in similar situations, where your health insurance is used as a sticking point, or a dangling point, to stay in harmful situations…. It really creates a power dynamic…. My greatest fear was that if I lost my health insurance, I wouldn’t be able to afford my insulin.[122]

Many of the people who spoke with Human Rights Watch about experiences with insulin rationing were able to eventually secure adequate insurance coverage that has prevented them from rationing. But interviews with Human Rights Watch made clear that high insulin costs can still force individuals with health insurance to face financial hardships that undermine their standard of living.

A 40-year-old father in Texas who spoke with Human Rights Watch estimated that he spent about $30,000 out-of-pocket to pay for insulin for him and his daughter between 2015 and 2020, despite having health insurance through his employer.[123] He explained that the health insurance coverage he received through his former employer had a yearly deductible of around $6,000; accordingly, at the beginning of each year, the deductible reset, and he paid that amount out-of-pocket before the insurer began to cover costs.[124] Year after year, he explained, he would meet his deductible with just a few visits to the pharmacy:

I would get a month’s supply and know [my] bill was $1,200 or $1,300…. [T]here were times I had to make a call: do I push off the mortgage payments this month and pay it late? Or get the insulin?[125]

Approximately 30 percent of US adults with employer-sponsored health insurance are enrolled in one of these so-called high deductible health plans, which the Internal Revenue Service defines as requiring an annual deductible of at least $1,400 for an individual or $2,800 for a family.[126]

Almost every person with diabetes who Human Rights Watch interviewed stressed the importance of finding employment with health insurance coverage. This need, driven by the necessity to mitigate the high price of insulin, profoundly affects decision-making around jobs and careers. The 40-year-old father in Texas described how the cost of insulin has affected his daughter, who just graduated from high school and is preparing to enter college:

It’s heartbreaking… She sees the overwhelming cost [and she’s] not [thinking]: ‘What do I want to do?’ It’s: ‘What field will give me the best insurance to cover these costs that we have?’ … it’s eye-opening to hear [her] say that.[127]

Prescribing Practices and Higher-Priced Insulin Analogs

A contributor to the unaffordability of insulin in the US has been the shift away from synthetic human insulins, which are less expensive but more complicated to use, to more expensive human insulin analogs.[128] While the prices for both synthetic human insulins and human insulin analogs have increased over time, synthetic human insulins, which first came onto the market in the 1970s, are often sold at a much cheaper list price.[129]

While much cheaper, these older synthetic insulins can make effective blood sugar regulation much more difficult.[130] Two types of traditional, synthetic human insulin are sold over the counter for as little as $25 a vial: regular human insulin and Neutral Protamine Hagedorn (NPH) insulin.[131]

Regular human insulin is taken several times a day to manage blood sugar around meals.[132] Compared with rapid-acting insulin analogs, such as Novolog or Humalog, regular insulin stays in the human body for a much longer time and peaks much later after injection.[133] Similarly, NPH insulin, also known as intermediate-acting insulin, provides background blood sugar regulation but has a peak approximately 4 to 6 hours after injection, unlike modern long-acting insulin analogs such as Lantus.[134]