Summary

We already suffered at the hands of Boko Haram before now and we are still suffering at the hands of the government.

– Aisha, displaced person in Gubio camp, Borno State, Nigeria, April 2022[1]

Since the beginning of Nigeria’s conflict with the Islamist armed group Boko Haram in 2009, more than two million people have been displaced in the country’s northeast. Many internally displaced persons (IDPs) have sought refuge in camps set up and run by state governments across the northeast region. Government authorities in collaboration with humanitarian organizations have provided food, water, sanitation facilities, health care, and education to those displaced, often for years.

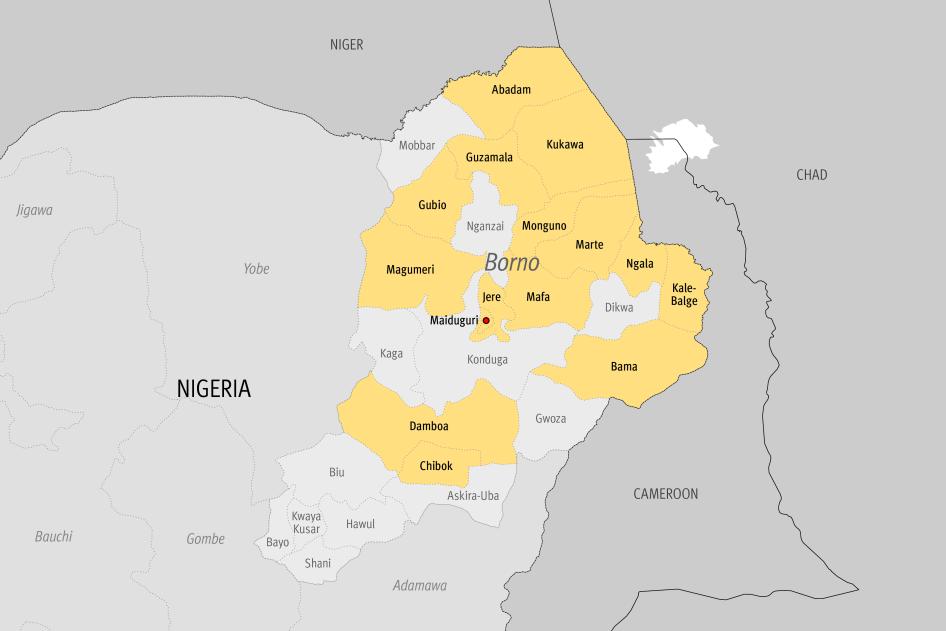

In Borno State, the epicenter of the conflict with a population of about 1.8 million displaced persons, the state government in 2021 began shutting down all camps located in Maiduguri, the capital, generally regarded as the most secure location in the state. The shutdowns have compelled displaced people to leave the camps without consultation, adequate information, or sustainable alternatives to ensure their safety and livelihoods in violation of Nigeria’s obligations under African regional law and international law on the rights of internally displaced persons. The practices have also contravened Nigerian domestic policy standards.

As of August 2022, Borno State authorities had relocated over 140,000 people from eight camps shut down in Maiduguri since May 2021. Those closed include the Bakassi, Stadium, Teacher’s Village, Farm Center, Dalori I, Dalori II, Mogcolis, and National Youth Service Corps (NYSC) camps. Two camps—Muna Badawi and 400 Housing Estate (Gubio) Camp housing nearly 74,000 people—were also set to be closed later in the year.

Altogether, the Borno State government’s move to shut down the camps in Maiduguri has affected or will affect over 200,000 displaced people.

|

Camp |

Date of closure |

Number of people affected (approximately) |

|

Mogcolis |

May 2021 |

4,000 |

|

NYSC |

May 2021 |

2,700 |

|

Farm center |

September 2021 |

30,000 |

|

Bakassi |

November 2021 |

35,000 |

|

Stadium |

January 2022 |

18,000 |

|

Teachers’ village |

January 2022 |

20,000 |

|

Dalori I |

August 2022 |

7,478 |

|

Dalori II |

August 2022 |

13,157 |

|

Gubio |

Impending closure |

22,817 |

|

Muna El Badawi |

Impending closure |

51,134 |

This report documents the impact of the completed and impending shutdowns on the displaced population in Borno State. It is based on various sources including internal reports, records and documents from government and humanitarian agencies working in Borno State, as well as interviews with aid workers and nearly two dozen displaced people, including current or former residents of Dalori II, Gubio, and Bakassi camps. Our research found that shutting down the camps has pushed many displaced people—who were already suffering from the conflict—deeper into destitution, leaving them struggling to eat, meet basic needs, or obtain adequate shelter. The planned shutdown of the remaining camps is already stoking anxiety among residents who fear similar harms absent significant changes in the authorities’ approach to the situation.

Inadequate Food, Shelter, and Security

Human Rights Watch interviewed displaced people who had been forced to relocate from Bakassi camp back to their insecure home community in Bama outside Maiduguri; moved into low-income communities in various parts of Maiduguri; or moved into informal camps in the city. Informal camps exist where private landowners give permission to a group of displaced persons to build temporary structures for shelter. People who live in these informal camps must fend for themselves without any support from the government and only ad hoc support from humanitarian organizations or other institutions.

Many displaced people in Maiduguri said they suffered severe hunger after agencies including the World Food Programme (WFP) and the Borno State Emergency Management Authority (SEMA) stopped providing monthly food rations and cash transfers for food. This followed the state government’s pronouncement in October 2021 that the camps were set to be shut down by the end of that year. The food support stopped abruptly without any official notice or explanation. WFP officials told Human Rights Watch that the organization stopped providing food support to camps within their purview in Maiduguri, including Dalori I, Dalori II, and Gubio in November 2021 following the government’s announced closures. They said that although Dalori I and Dalori II were not shut down until August 2022 and Gubio currently remained open, WFP could not provide support to beneficiaries who were not factored into their plans for 2022 because of the slated shutdowns. WPF officials added that they faced funding gaps that later made it impossible for the organization to scale up their plans in the first quarter of 2022 to include support for beneficiaries in these camps, which remained open beyond December 2021.

Although SEMA has carried out some ad hoc food distribution since the monthly food support to camps including Gubio stopped, deliveries have been sporadic and insufficient to meet needs.

Most of the displaced people who spoke to Human Rights Watch had to engage in income-generating activities for menial sums to support themselves even while they were still receiving aid in the camps. Some sold firewood fetched from nearby bushes or hand-knitted caps, while others carried out day labor or traded in food items or fruits, earning around 300-700 naira (US$0.52 - $1.21) daily, which could not support the basic needs of themselves and their families after aid to the camps was cut off.[2]

State authorities distributed money (between 50,000 and 100,000 naira, or US$86.21 to US$172.41) to some individuals recognized as heads of household and wives in male-headed households prior to the camp closures, reportedly intending these funds as livelihood support. [3] However, these funds were too little to provide any meaningful support for families to build their lives afresh and were used to meet immediate needs. Displaced persons told Human Rights Watch that they used the money to transport themselves and their belongings out of the camps, rent houses or build makeshift structures for shelter, and buy food. Many said that within the next two or three months, they had already exhausted these funds.

Those who returned to Bama also had limited opportunities to earn income there. Because of security concerns, they were unable to go outside the town limits to access farmlands. Nigeria’s military in May and August 2022 launched airstrikes against insurgents in the area, indicating that the area remained insecure.

In December 2021, the Borno State government wrote to all humanitarian organizations, banning them from distributing food and other aid, including hygiene kits, to resettled communities such as Bama, where state authorities claimed returnees would be provided with support. However, displaced persons and humanitarian workers told Human Rights Watch that housing, water, health care, schools, and other infrastructure necessary to meet basic needs were lacking in many of the resettled communities.

Without any food aid, families affected by the actual or impending IDP camp closures said that they have faced severe challenges in meeting basic needs. Some said they have been forced to skip meals or go for days without something substantial or nutritious to eat. Some others, including children, have resorted to begging on the streets to survive despite the dangers this presents, such as road accidents, kidnapping, trafficking, and sexual violence.

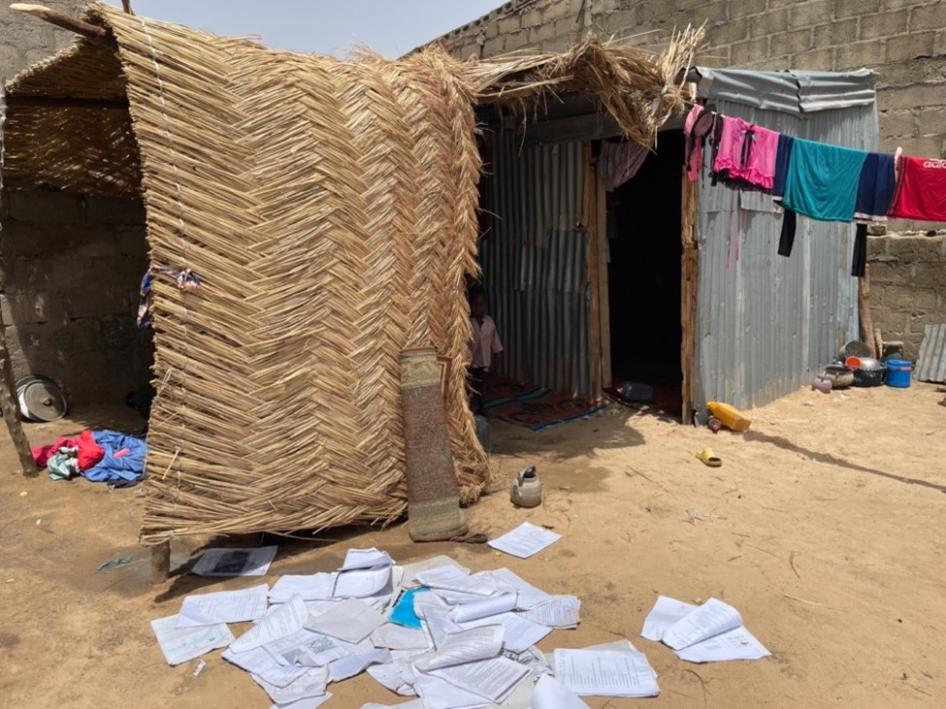

While Human Rights Watch’s research did not seek to quantify the people affected in this way, the interviews indicated that a sizeable number of displaced persons affected by camp closures were living in worse physical structures than in the camps. People residing in the camps lived in tarpaulin tents that humanitarian organizations set up, or they occupied single rooms in houses built on the premises before they were allocated for use as camp sites.

Most of the people whom Human Rights Watch interviewed who had relocated within Maiduguri after the camps were shut down said they resorted to living in self-constructed thatch, tarpaulin, or zinc structures. They secured permission from private landowners either to build these structures individually or to join an existing group’s informal campsite. The structures that Human Rights Watch visited were poorly built and provided little shelter from heavy rains, putting their belongings at risk.

Borno State authorities asserted that they had rebuilt houses in Bama that were previously destroyed in the conflict with Boko Haram. However, interviewees who had moved back to Bama said that they did not find their homes rebuilt. Some resorted to living in their partially destroyed homes, while others built thatch structures or tents in their compounds. Those living in the makeshift thatch structures in Maiduguri and Bama had no access to sanitation facilities, relying on pit latrines around their homes.

Lack of Consultation, Information on Relocation

The devastating impact of the camp closures and aid cutoffs on displaced persons was exacerbated by the way in which the authorities implemented closure decisions, causing significant confusion, uncertainty, and anxiety. The authorities conducted little or no consultation with displaced persons in the various camps, including those that would soon be closed. They did not provide adequate information to displaced persons that could have helped them make informed decisions about their next move. In a few cases, community leaders in the camps gathered people to inform them of impending shutdowns, but without many details, as the leaders themselves had little tangible information.

Though authorities did not publicly explain their camp shutdown process, a pattern emerged during the closures of some camps between November 2021 and August 2022. The closures that Human Rights Watch documented began with an unannounced visit to the camps very early in the morning by the state governor or his representatives, who would line up heads of households and wives to count them and hand out cards with numbers. In a subsequent unannounced visit, also in the early hours of the morning, government officials used the cards to identify people designated to receive money for livelihood support. Residents also received a date by which they were required to vacate the camps, usually within 10 to 15 days.

This process not only gave people insufficient time to prepare but did not consider or provide for people who fell outside of the designated categories, such as unmarried young adults above the age of 18 who do not depend on their families for support. There was also no mechanism to include people who were away or unavailable at the time families were counted, or to monitor the process and ensure that everyone was treated fairly.

In one of the camps set to be shut down, authorities carried out an early morning, unannounced visit to distribute cards in 2021, but as of September 2022 had yet to carry out the second visit to distribute money. So far as Human Rights Watch could ascertain, no dates were communicated for distribution of cards or money at any of the camps set to be closed, and no dates were communicated for the eventual camp closures. This continued to be a source of anxiety for residents, who said they were afraid to leave the camps for fear that the authorities might visit while they were away, and they might miss out on the opportunity to receive the payment.

Problematic Justifications for Camp Closures

Borno State government officials have sent mixed messages regarding the decision to shut down the camps. In October 2021, when Governor Babagana Umara Zulum first announced that the camps would be closed, he said the decision was informed by a recent improvement in the security situation in the state, and that it was safe for displaced people to return to the communities they had fled because of the conflict. However, subsequent reports have highlighted continued insecurity in many communities to which displaced persons are being encouraged to return. Reported incidents include Boko Haram attacks against military targets and civilians, such as the May 2022 attacks on Rann in which insurgents killed over 50 people, and Nigerian troops’ shelling of insurgent forces in Bama.

The governor also stated in a public address that it had become necessary to shut down camps because they were becoming slums where all kinds of vices—including drugs and “thuggery”—including drugs and thuggery, were taking place. If this concern is genuine, shutting down camps without adequate preparation or appropriate relocation will magnify the harm to the entire population: allegations of criminality in the camps should be investigated and dealt with by the appropriate authorities, including the police, who have a presence in the camps.[4]

Government officials have also claimed that the camp closures were necessary to return the camp sites to their original use, some of which include housing estates for teachers and low-income civil servants, though the sites were converted to displacement camps before they were occupied. The Borno State government has obligations toward those who would benefit from the original purposes for the housing. But before turning over the housing to their original intended use, arrangements need to be made to move displaced persons at the camps to other suitable locations.

The Borno State authorities have further claimed that the camp shutdowns are necessary as part of its development agenda to take people off humanitarian assistance, enhance their dignity, and build their resilience to contribute to the development of the state.[5]

This appears to be closely tied to the Borno State government’s 25-year Development Framework and 10-year Strategic Transformation Plan.[6] Launched in 2021, the plan highlights the resettlement of displaced individuals and families in secured, affordable, and self-sustaining communities as a key indicator for success. It also aims to achieve voluntary resettlement of at least 50 percent of displaced persons by the end of 2022 and the shutdown of all displacement camps in the state by 2026.

Ongoing stabilization and recovery projects in communities across the state – on which the government is collaborating with development partners such as the United Nations Development Programme and the World Bank and which seek to encourage returns to these communities—may be helping drive the camp closures. These multiyear projects with budgets of millions of dollars are aimed at strengthening security and the rule of law, providing access to livelihoods, reinstating or improving essential infrastructure and basic services, and strengthening social cohesion in communities affected by the conflict. While these are important goals, humanitarian workers in the state note that these projects have yet to deliver on key objectives including provision of adequate housing, health care facilities, and schools for displaced persons returning home.

Government Steps and Obligations

Nigeria has committed to upholding the rights of internally displaced persons by ratifying the African Union Convention for the Protection and Assistance of Internally Displaced Persons in Africa (“Kampala Convention”). The world’s only legally binding regional instrument on internal displacement, the Kampala Convention builds on the 1998 UN Guiding Principles on Enforced Displacement, an authoritative restatement of existing international law regarding the protection of IDPs.

Under the Kampala Convention, internally displaced persons have the right “to be protected against forcible return to or resettlement in any place where their life, safety, liberty and/or health would be at risk.” The government is obligated to consult with and ensure the participation of internally displaced persons in the planning and management of their return, resettlement, or integration, enabling displaced people to “make a free and informed choice” regarding these processes.

The Kampala Convention specifically obligates the government to seek lasting or durable solutions to the problem of displacement by promoting and creating satisfactory conditions for voluntary return, local integration, or relocation on a sustainable basis and in circumstances of safety and dignity.

The government is also obligated to “ensure assistance to internally displaced persons by meeting their basic needs as well as allowing and facilitating rapid and unimpeded access by humanitarian organizations and personnel.”

Nigeria’s National IDP Policy, adopted in 2021, sets out comprehensive criterion that government and other actors should meet to achieve durable solutions for displaced persons. The policy also outlines a set of strategies and standards for the return, relocation, and integration of displaced persons in line with the Kampala Convention.

While the government’s IDP policy and efforts to domesticate the Kampala Convention by codifying it into local law are positive steps, the Borno State government’s efforts to shut down the camps have fallen far short of the policy’s standards as well as the convention’s requirements. The federal government is doing far too little to protect displaced persons. By pushing people out of camps and restricting access to aid without putting in place viable alternatives for support, the state government is worsening suffering, entrenching poverty, and deepening vulnerability for thousands of displaced families. If the same process is employed to shut down the numerous displacement camps in other areas of the state beyond Maiduguri, hundreds of thousands more will be at risk of suffering the same fate absent new effective support measures.

The Nigerian federal government should urgently engage with the Borno State government to halt further camp closures, and both governments should work together with the UN, donor governments, and humanitarian agencies to ensure that plans to return or resettle displaced persons do not violate their rights. They should also remove restrictions on aid and ensure that humanitarian organizations can provide lifesaving assistance in displacement camps and all areas where needs are identified.

Methodology

Human Rights Watch conducted the research for this report, including field research in northeastern Nigeria and Abuja, the national capital, between April and May 2022. We documented the effects of the Borno State government’s decision to shut down displacement camps in Maiduguri, Borno State’s capital city, where thousands of people displaced by the armed conflict with Boko Haram have sought refuge.

Human Rights Watch interviewed 22 internally displaced people, including 8 people living in two displacement camps, Dalori I and Gubio, as well as 14 people who had left Bakassi camp in Maiduguri, which the state government shut down November 2021.

Human Rights Watch informed interviewees about the nature and purpose of the research and how the information they provided would be used. Human Rights Watch obtained consent for each of the interviews. No incentives were provided in exchange for the interviews, which were conducted in the interviewee’s local language, in private settings, and in IDP camps using an interpreter. A Human Rights Watch researcher visited and inspected the living conditions of displaced families in Dalori I camp before it was shut down in August 2022 and Gubio camp in Maiduguri, which was set to be shut down. The researcher also visited one informal camp in the Sulumburi area of Maiduguri and Shuari, a low-income community where some displaced families found shelter.

Human Rights Watch also interviewed two camp management officials, five representatives of international humanitarian agencies providing lifesaving assistance to displaced persons, and eight United Nations officials coordinating humanitarian and development assistance in Borno State. In addition, Human Rights Watch reviewed internal reports, records and documents from humanitarian organizations, various committees, and groups within the humanitarian sector that were set up to monitor the humanitarian situation and coordinate humanitarian response in Borno State.

In August, Human Rights Watch shared the main findings of this report with federal government authorities, including the Ministry of Humanitarian Affairs and Social Development, and Borno State officials, including the governor. We sought answers to specific questions, including the rationale and process undertaken to close the camps in Maiduguri. The federal government authorities and Borno State officials have not responded to our letters.

Throughout the report, US dollar amounts are estimated using the parallel market exchange rate at the time interviews were conducted, as this rate more accurately reflects the true value of currency in Nigeria. US dollar amounts converted using the official government exchange rate are provided in footnotes. Between April and October 2022 , the parallel market exchange rate rose from about 580 naira = US$1 to about 750 naira = US$1. The official government rate during this period was however pegged between 415 naira = US$1 and 436 naira = US$1.

I. Background

Boko Haram Insurgency

The Islamist armed group Boko Haram has since 2009 carried out an insurgency in Nigeria’s Northeast that has been marked by brutal abuses, including targeted killings, suicide attacks against civilians, widespread abductions, and burning and looting of towns and villages. The term “boko haram” in Hausa, the dominant language in northern Nigeria, means “Western education is forbidden” and is used broadly to refer to the group known as “Jama’atu Ahlis Sunna Lidda’awati wal-Jihad” (JAS) and its breakout factions, which are waging an armed conflict in Nigeria’s Northeast. The Northeast consists of six states: Adamawa, Bauchi, Borno, Gombe, Taraba, and Yobe. Borno, Adamawa, and Yobe have been most affected by the insurgency.

“Jama’atu Ahlis Sunna Lidda’awati wal-Jihad” is an Arabic phrase which, roughly translated, means “People Committed to the Propagation of the Prophet’s Teachings and Jihad.” The group was founded in 2002 in Maiduguri, Borno State’s capital, by Muslim cleric Mohammed Yusuf, with the purported aim of supporting Islamic education and creating an Islamic state in the country. Following a series of attacks by the group on police stations and other government buildings in Maiduguri, Nigeria’s security forces in 2009 raided their headquarters, killing Yusuf. After his death, Boko Haram was led by Abubakar Mohammed Shekau, who masterminded some of the group's deadliest operations. In a 2014 attack that brought international notoriety to the group, Boko Haram abducted 219 girls from the Chibok secondary school.[7]

In response to the insurgency, Nigerian security forces have carried out abusive measures against civilians, including extrajudicial killings, torture, and arbitrary arrests and detention. Amnesty International found that at the peak of the conflict between 2012 and 2015, Nigerian military forces extrajudicially executed more than 1,200 people; arbitrarily arrested at least 20,000 mostly young men and boys; and committed countless acts of torture while carrying out operations against Boko Haram.[8]

In 2015, the Nigerian military, joined by troops from Cameroon, Chad, and Niger, launched a major military campaign to retake territory occupied by Boko Haram. At the time, territory under Boko Haram control extended across most parts of Borno, northern Adamawa, and into eastern Yobe States.[9]

By 2018, Boko Haram’s areas of control were limited to remote communities and camps including their main base in Sambisa Forest, but the group continued to carry out abductions, suicide bombings, and attacks on both military forces and civilians.[10] At about this time, the Islamic State West African Province (ISWAP), which pledged allegiance to the Islamic State (ISIS), emerged as a prominent breakout faction of JAS.

The International Crisis Group reported that ISWAP split from JAS because of differences in ideology and approach to the conflict. While JAS carried out unlawful attacks against civilians as well as the military, ISWAP apparently sought to win over the population by claiming to treat them better than JAS and by attempting to fill key gaps in governance and service delivery in certain communities.[11]

The reported death of JAS leader Abubakar Shekau after an attack by ISWAP in June 2021 further changed the dynamics of the conflict, significantly reducing the operations of JAS in the region and bringing greater prominence to ISWAP.[12]

In January 2022, Borno State Governor Babagana Umara Zulum stated that Abadam and Guzamala local government areas in the state were still under the control of ISWAP. He raised concerns that the group’s operations were spreading across the state.[13]

Reports of killings and other attacks against civilians, including an ISWAP attack in May 2022 in Rann, in Kale-Balge Local Government Area, that killed over 50 people clearing their farmlands and fetching firewood, highlighted the continued hostilities in the region and the risks to civilians.[14]

In 2021, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) estimated that 35,000 people had been killed since the insurgency began while an estimated 314,000 people had died because of the indirect impact of the conflict, including disease and hunger resulting from the conflict’s physical and economic destruction in the region.[15] The humanitarian crisis in Northeast Nigeria remains one of the most severe in the world today. In February 2022, the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) reported that 8.4 million people in the Northeast needed humanitarian assistance.[16]

Displacement in the Northeast

As of July 2022, the Boko Haram conflict had displaced about 2.2 million people in the Northeast, the vast majority–over 1.8 million—in Borno State.[17] The conflict also displaced over 280,000 refugees from the Northeast into three neighboring countries—Cameroon, Chad, and Niger.[18] Displaced persons have fled their homes and communities to seek safety from hostilities and attacks by both sides of the conflict.

The abruptness of the violence in most instances has resulted in the displacement of entire communities and has split many families fleeing in different directions in search of safety.[19] The fighting and mass displacement has also disrupted people’s access to farmland, markets, and other sources of livelihood that they have left behind.

In Borno State, most displaced people have left isolated ancestral communities to seek refuge in towns and cities with a stronger military and humanitarian presence. Many people have ended up in Maiduguri, the capital city, which was never under the control of Boko Haram or other Islamist armed groups and is the main operational base for most humanitarian groups providing support.

In response, the Borno State government worked with humanitarian organizations to establish camps in Maiduguri and other areas where the need arose to provide displaced people shelter and food, health care, and education.

OCHA and other UN agencies have played a key role in working with the government and humanitarian organizations to coordinate this emergency response.

Over the years, conditions in the camps have deteriorated, in part due to the volatile security situation that continues to fuel more displacements and movement into the camps, which have been stretched beyond capacity. Displaced people in some camps live in poor conditions and grapple with issues such as insufficient food, overcrowding, lack of privacy, and inadequate health care and education services.[20] There are also protection concerns in many camps where cases of rape and sexual exploitation of women and girls have been documented.[21]

Attempts to Return IDPs in Borno State, 2016-2018

Successive administrations in Borno State have sought to relocate displaced people back to their home communities despite security concerns and a lack of adequate infrastructure including housing in many of these communities which were destroyed during the conflict.

In November 2016, the then-Borno State governor, Kashim Shettima, announced that all camps in the state would be closed by May 2017, citing as justification early child marriage, prostitution, drug abuse, and gangsterism in the camps.[22] He also stated that “social challenges of an entitlement complex” will arise if people in the camps began to feel “entitled to be catered for.” He emphasized the need to “restore the dignity of our people” by rebuilding their homes and schools and engaging them in empowerment initiatives so they could return to their homes.[23] At the time, there were 32 displacement camps in Borno State, where over 500,000 people were receiving aid including food and other basic necessities.[24] More than 120,000 of them were in 16 camps located across in Maiduguri.[25]

After the military recaptured Bama, Borno State’s second biggest town, from Boko Haram in March 2015, state authorities announced plans to return residents to their community in 2016. However, in May 2017, Shettima announced that the IDP returns were no longer possible due to pockets of attacks by the insurgents, as well as because the reconstruction work in the communities had yet to be completed.[26] He said that the government would not allow any displaced person to return to unsafe communities where people could not go about their lives and livelihoods without security concerns.[27]

In 2018, despite concerns raised by humanitarian organizations about the security and state of infrastructure in Bama, the governor resumed plans to return displaced residents to the community. In March, he announced that returns would start in April 2018 following assurances by the military that Bama was safe.[28] Three weeks after residents returned, a double suicide attack during early morning prayers at a mosque in Bama killed four people and injured seven.[29]

Media reports suggested that the efforts to return displaced people to Bama had been politically motivated to maintain an image of victory ahead of the 2019 presidential elections, in which President Muhammadu Buhari sought reelection.[30] When President Buhari was elected in 2015, one of his main promises was to tackle the insecurity in the Northeast. During his term he declared several times that Boko Haram had been defeated despite ongoing attacks.[31]

By August 2018, more than 16,000 displaced persons had returned to Bama,[32] but the security situation remained volatile with continued attacks by Boko Haram in and around the area.[33]

Borno State IDP Returns Strategy, 2018

In September 2018, the Borno State government collaborated with the UN, humanitarian organizations, and other relevant stakeholders to adopt the Borno State Returns Strategy, which articulates a coordinated framework for safe, dignified, informed, and voluntary return of displaced persons to their home communities.[34]

The Return Strategy set minimum conditions for the return of displaced persons and provides a step-by-step process to be followed during organized returns that are in line with the Kampala Convention,[35] the Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) Framework on Durable Solutions for Internally Displaced Persons,[36] and the UN Durable Solutions Preliminary Operational Guide.[37]

These minimum conditions require the involvement and consent of displaced persons in the processes of returns, including through access to accurate and objective information, full and equal participation in decision making, and organized “go and see” visits to allow them to inspect areas intended for return and ensure they can make well-informed decisions on whether to return. The conditions also spell out specific measures to ensure voluntariness of returns and require that displaced persons be protected from direct coercion through physical force, harassment, or intimidation, as well as indirect coercion, such as through the provision of erroneous information, the denial of basic services, or the closure of displacement camps or facilities without the provision of an acceptable alternative.

Other minimum conditions for returns include a favorable protection environment and physical safety; freedom of movement; availability of basic socioeconomic services; and assistance or support for spontaneous returns.

The strategy set a process for returns to take place, which begins with the identification or classification of areas for return by military or civilian authorities based on security conditions. This is followed by a joint assessment mission to determine if the minimum conditions for returns are present or feasible. This joint assessment should be carried out by relevant government agencies, humanitarian and development partners, and key community stakeholders, who need to set short, medium, and long-term response priorities to ensure adequate and sustainable conditions for returns if they determine that the areas identified are suitable for returns.

This is followed by the development of a location-specific return plan and the implementation of the plan, which includes dissemination of information to displaced persons and organization of “go and see” visits.

The Return Strategy recognizes that the Nigerian government has the primary responsibility to create the conditions enabling durable solutions, including the safe, voluntary, and dignified return of displaced persons. However, it also recognizes the importance of the participation of a range of stakeholders including state and local as well as federal authorities, donor governments and institutions, humanitarian and development organizations, displaced persons, and host or local communities.

New Efforts for IDP Returns and Camp Closures, 2020-2022

Following the adoption of the Return Strategy, authorities paused efforts to return displaced people to their home or ancestral communities. However, in 2020, the Borno State government, under Governor Zulum, who took office in 2019, launched and began implementation of a new plan to return 1.8 million IDPs from camps in Maiduguri to their towns and villages of origin, where the government said houses and other amenities had been constructed or renovated to accommodate them.[38]

Human rights and humanitarian organizations in the Northeast raised concerns over the implementation of Zulum's return plan, which did not comply with the principles and processes outlined in the Return Strategy. These concerns have mainly centered around the transparency of the process employed, which included neither consultations with humanitarian organizations and displaced persons, nor a joint assessment of the areas slated for returns to determine if they met the minimum conditions set out in the Return Strategy.

These groups raised similar concerns following the October 2021 announcement that the Borno State government intended to shut down by December 2021 all displacement camps supported by the government in Maiduguri, in which over 140,000 displaced people lived at that time.[39]

Between May 2021 and August 2022, the Borno State government closed eight camps in Maiduguri housing thousands of displaced people: Bakassi, Teacher’s Village, Stadium, Farm Center, Dalori I, Dalori II, Mogcolis, and NYSC camps. In August, when the authorities carried out the latest shutdown of Dalori II camp, Governor Zulum announced that all IDP camps in Maiduguri had been officially closed. However, as of September 2022, two camps remained open there: 400 Housing Estate Camp (commonly referred to as Gubio) and Muna Badawi. These two camps, which are also set to be shut down, hosted 73,9510 displaced people at time of writing.[40]

II. Inadequate Consultation, Support, and Information Before Camp Closures

Many of the internally displaced persons in Borno State who spoke to Human Rights Watch said that under the right conditions with adequate safety, livelihood opportunities, housing, and other basic infrastructure, they wanted to return to their normal lives in their home communities. Human Rights Watch research indicates that authorities did not give displaced people adequate time, information, or options to make informed decisions about whether to leave the camps, and the places available for return or resettlement did not meet adequate living and security standards.

Displaced people told Human Rights Watch that they—along with many other IDPs—had received no written or oral communication from the state government or other government agencies regarding the camp closures. Interviewees said that they either heard of the camp closure on the radio when the governor was speaking or through other people discussing it in their camps.

A 45-year-old resident of Dalori I camp told Human Rights Watch that he heard the governor announce the camp shutdowns on BBC Hausa radio in October 2021. He said:

I became aware [of the camp shutdown] from the governor on the radio. His radio announcement said that before January 2022 there will be no IDP camps in Maiduguri, and that the camps will be shut down by December 2021. He gave reasons that if he allows us to continue staying in the camps to collect money and food from INGOs [international nongovernmental organizations], we will be reluctant to go back [to our home communities] because we are used to depending on people and won’t be useful to ourselves. He also said that we need to become more resilient and stand our ground to defend our communities, asking for how long we will keep running from Boko Haram and their guns.[41]

Only two interviewees, both of whom had resided in Bakassi camp for over six years before it was shut down in November 2021, said there were some efforts by community leaders in the camp to disseminate information about the camp closure. However, this was grossly inadequate because they did not receive any necessary information beyond the fact that that the camps would be shut down.[42] A 53-year-old father of 24 children said:

They simply told us that the government said everywhere is now safe for return and people should go back to their villages or find anywhere else to go because the camp must be closed. We didn’t know when it would be closed or how we would go about relocating from the camp.[43]

Following the announcement in October 2021, authorities including the state governor appeared unannounced at various camps between 5 and 6 a.m. to count male and female heads of households and wives in male-headed households who were present at that time. These individuals received small cards to identify that they had been counted. “The Borno State Government,” the state’s logo, a barcode, and a number were printed on cards viewed by Human Rights Watch. While some cards had the category “Married Women” printed on them, others had “Northern Borno” and the letter “M” printed on them. At least two people told Human Rights Watch that they were not aware of the camp closures until Governor Zulum visited their camps to count residents and distribute cards.[44]

The cards were later used to distribute money to displaced persons. Male and female-headed households received 100,000 naira (US$172.41), and wives in male-headed households received 50,000 naira (US$86.21), apparently to support their transition out of the camps.[45] To our knowledge no other categories of people—such as unmarried young adults who are no longer dependents in their homes, or people without families in the camp— received money. Aid workers, a camp management official, and former camp residents said that there was no monitoring and verification system to ensure that those who may have missed being counted or were wrongly categorized could address these issues and benefit from the support. In Bakassi camp, government authorities gave residents about two weeks after the cash was distributed to leave the camps.[46] Human Rights Watch also found that people who had been in Farm Center camp had about seven days to relocate after government officials told them on August 29 that the camp would close on September 4.[47]

Interviewees described the day when they were compelled to leave the camps as one of anxiety, uncertainty, confusion, and chaos. They explained that government officials arrived that morning with Civilian Joint Task Force (CJTF) officials as reinforcement, going from house to house or tent to tent, telling people to leave.[48]

A 35-year-old mother of three, who initially moved to Monguno but came back to Maiduguri with her family after authorities closed Bakassi camp, described the day of the shutdown:

The camp was very busy that day we left. Everyone was gathering their things to leave. People were anxious because they did not know where to go. I wasn’t ready to leave that day, I wanted to stay for at least another day, but the CJTF officials came and told me to leave. I couldn’t get a vehicle to take my things, so I told the CJTF officials that were going house to house to make sure people were leaving that I wasn’t leaving. They said “no”—that I must go. I eventually got a tricycle [commercial motorized tricycle] to take me to the motor park, where I got a vehicle to Monguno. We usually have police, army and CJTF officials in the camp, but that day there were more than usual.

Interviewees in camps yet to be shut down said that they had also received cards in a similar process but had not received further information on when money would be distributed or when the camps would be shut down.[49]

While some said that government officials who came to their camps told them that the cards would be used to distribute money to them prior to the camp’s closure, others said they did not hear this but inferred it, based on rumors they heard and what they knew had happened in other camps that were shut down.[50] The 45-year-old Dalori I camp resident said:

A commissioner called Saina Buba [Borno State commissioner for youth and sports development] led a team of people to distribute cards to us. They arrived so early, around 5 a.m., that people were afraid it might be a Boko Haram attack. They told us not to sell or misplace the cards because it will serve as our food and money. When he mentioned food and money, people got excited. He didn’t say anything about relocation or camp closure. But after we were given the cards, we started thinking that this is a notice of relocation, because this is how it occurred in other camps.[51]

A Borno State Emergency Management Authority (SEMA) official involved in running one of the camps said that he knew several people who missed being counted and did not receive cards because they had stayed overnight in a hospital to care for loved ones.[52] As a result, they missed out on the financial support. He also said that the government, by distributing money only to people who were categorized as male or female heads of household and wives in male-headed households, denied many people from receiving support, especially young adults who are independent of their families or do not have any family.[53]

Interviewees said that they were not aware as to how the government arrived at the sums of money that were distributed. They complained that the money could not support their families to start afresh in a new location given that they had to transport themselves and pay for housing, water, and other necessities.[54]

A 20-year-old generator repair apprentice, who had moved to Bama with his parents after the Bakassi camp closure, said that the “government thinks that the 100,000 and 50,000 [naira] they gave will make an impact on our lives, but this cannot be farther from the truth. The money cannot help anyone settle down in a new place or start a business to sustain themselves and their families.”[55]

III. Impact of Camp Closures

Hunger and Deprivation

Hunger and food insecurity were foremost concerns of all the displaced people whom Human Rights Watch interviewed. Hunger is marked by discomfort or pain; food insecurity stems from lack of regular access to enough safe and nutritious food for normal growth, development, and an active and healthy life.

Current and former IDP camp residents in Borno State told Human Rights Watch that shortly after the governor’s announcement of camp shutdowns, organizations including the UN World Food Programme (WFP) and the Borno State Emergency Management Authority (SEMA) stopped providing monthly food rations or cash transfers to enable them buy food.[56] While there was no official communication preceding the abrupt end to food distribution in October 2021 in Maiduguri camps, displaced people said that they believed this was tied to the governor’s announcement about the camp closures. Two people said that when they started making inquiries to camp officials and people working for humanitarian organizations, including WFP, they were told that the governor had stopped all food distribution and any other kind of assistance in the camps.[57]

WFP officials told Human Rights Watch that the organization did not receive a directive to stop providing food support to camps within their purview in Maiduguri, including Dalori I, Dalori II, and Gubio.[58] They said they officially stopped providing food support in November 2021, following the government’s announcement in October 2021 that the camps would be shut down by December 2021. They only carried out what they described as “mop-up operations” in December 2021 to deal with shortcomings in the November food support distribution.[59] They said although Dalori I and Dalori II were not shut down until August 2022 and Gubio still remained open, WFP could not provide support to beneficiaries there who were not factored into their plans for 2022, which they had made believing the camps would all be shut down as announced.[60] They also explained that WFP faced funding gaps that initially made it impossible for them to scale up their 2022 plans and include support for beneficiaries in these camps that remained open beyond December 2021. However, they were later able to secure funding to resume some level of support in the second quarter of 2022.[61] However, when they approached the Borno State government to allow them to resume support in the remaining camps, they said they were refused on the basis that the camps were set to shut down soon.[62]

Before the organizations stopped providing food in Dalori I, Dalori II, and Gubio camps in November 2021, WFP was providing families with cash transfers (in bank notes) of 9,000 naira (US$15.52) per month per child in each household, for up to 10 children, to buy food and other basics.[63] Prior to this, WFP gave vouchers of 18,500 naira (US$31.90) per month to each family.[64] The vouchers were redeemable from local food vendors. WFP also provided support to NYSC camps and Stadium camps before they were shut down in May 2021 and January 2022 respectively.[65]

A 31-year-old father of three, who returned to Bama after Bakassi camp closed, said that before the announcement of the camp closure, SEMA provided his family monthly food rations consisting of rice, maize, beans, oil, Maggi seasoning cubes, and occasionally soybeans:

They stopped abruptly around October, and it was a huge problem because we didn’t get any information to plan, they just stopped, and we didn’t have any alternative sources to get food or money to supplement… I am wondering if any good will come to us in the next couple of months. Right now, we eat twice or once [per day]… [I]t is not regular at all, what we see is what we get.[66]

A 29-year-old father of four, who also moved to Bama from Bakassi camp, said:

When everything was okay in the camp in Maiduguri, we could eat protein, like fish, but in Bama we can’t afford this kind of food. My children are not healthy as they are supposed to be, they are now thin and frail. ... if the government really wants to help us, they should help us with food right now.[67]

Many people displaced within Borno State due to the conflict were farmers or traders before they lost everything. Several explained that contrary to what they heard the governor imply about dependence on aid making them lazy, they had carried out income-generating activities to support themselves while in the camps and continued to do so. Some sold firewood gathered from bushes or hand knitted caps, while others carried out menial jobs around the city or sold food items or fruit.[68]

A 55-year-old father of 17 living in Dalori 1 camp said that he earned about 700 naira (US$1.21) a day from working on farms, while a 35-year-old widow and mother of 5 in the same camp said she earned 200 or 300 naira a day selling firewood.[69] They explained that the money earned from these activities could not support their families’ food, clothing, and toiletry needs, leaving them in dire need of assistance.

Without food rations and cash transfers, displaced families said they struggled to afford food and had to skip meals or go for days without something substantial to eat. A 65-year-old man with nine children, who had lived in Bakassi camp for seven years until it shut down and moved to an informal camp in the Sulumburi area of Maiduguri, said on the day he was interviewed in April 2022 that he had no food at all to eat. He said all he could afford to buy that day was some baking flour to make food for his children.[70]

In some informal camps in Maiduguri, private landowners have given permission to displaced people to build structures consisting mostly of thatch or tarpaulin for temporary shelter. People live independently in these camps, which are not organized or supported by the government. Humanitarian agencies, however, sometimes provide one-off support to some informal camps by constructing latrines or donating thatch and tarpaulin to enable displaced persons to build shelters.

A SEMA official involved in the coordination of activities including the registration of displaced persons and the provision of support in the formal camps said:

[W]e see a lot here, since the food distribution stopped, people do not have anywhere to get food, they are weak, malnourished to the point where they come to me to beg for even 50 naira (US$0.09) to enable them find food to eat. It is overwhelming.[71]

He further explained that since the monthly food support stopped, Gubio camp had received two ad hoc food donations from SEMA in January and March, but it did not adequately support the camp made up of 22,817 people in 4,919 households.[72]

In January SEMA provided 15 25-kilogram bags of rice, 10 50-kilogram bags of groundnut, 15 gallons of vegetable oil, 10 50-kilogram bags of beans, some sugar and salt.[73] In March SEMA provided 1000 10-kilogram bags of semolina flour, 100 25-kilogram bags of rice, 5 50-kilogram bags of groundnuts, and 5 50-kilogram bags of beans.[74] The SEMA official said “It is a nightmare to figure out how to distribute this to each household, it is simply not enough for everyone to get something significant, so this causes chaos and violence as people struggle and some people end up not getting anything at all.”[75]

Hunger and food insecurity has also forced some people in the camps not yet closed to go out into the streets to beg or send their children to beg. A 40-year-old mother of eight living in Gubio camp said:

Since WFP stopped giving us money for food, we have been suffering. Sometimes we have nothing at all to eat, so I send my children to beg on Baga Road or in Grasshopper market in Shagari Locus while I try to sell firewood. They usually bring back leftover food or other things, like akara [fried bean balls], which people give them to eat. But I am afraid when I send them out because they can get hit by a car.[76]

Two displaced people living in Dalori camp said that an 11-year-old girl living with her family in the camp died in February 2022 after she went out to beg for food to feed her mother, who had just given birth. They said that she was hit by a car on her way home after she managed to get some food to bring home for her mother to eat.[77]

Displaced people compelled to leave Bakassi camp after it shut down said that the money handed out to them by the Borno State government was hardly enough to aid their transition from the camps and to provide livelihood support after they settled in other locations. They said that they used the money for transportation to the various locations, to pay rent, to build makeshift houses, or to buy food. They said they have since exhausted these funds as they continue to struggle to find adequate livelihood sources.[78]

A 31-year-old man with a family of four said that of the 150,000 naira (US$258.62) his family received from the government before Bakassi camp was shut down,[79] they used 70,000 (US$120.69) to buy materials to build a zinc tent for shelter and used the rest to feed themselves, until it ran out.[80]

A 35-year-old mother of seven living in Shuari in Maiduguri said that after Bakassi camp closed, she returned with her family to Monguno, her community of origin, but came back to Maiduguri because of the suffering there.[81] She said:

After one month of suffering in Monguno, with no food support, no livelihood, we decided to come back to Maiduguri to see if we will get some menial jobs to do. We spent 20,000 naira (US$34.48) to and from, and I wish we didn’t spend that money that we so desperately need by leaving Maiduguri… If we had known it [Monguno] was like that, we wouldn’t have gone in the first place.”[82]

Those who returned to Bama, where the main source of income is farming, said that there were limited opportunities to make an income within the safe parameters of the community where they live, which is secured by the military. They said they were unable to go outside this area to access farmlands due to security concerns, including risk of encounters with insurgents active in the area and airstrikes from the Nigerian security forces targeting the insurgents.[83] In May 2022, there were reports of artillery shelling by Nigerian troops fighting Boko Haram fighters in Bama.[84]

The 31-year-old father of four said:

Before the insurgency I was a farmer and a trader, but now I have nothing to do…we can’t go out of the trenches [surrounding the secure area where they live] to go and farm, because it is not safe. I don’t have a source of income or a salary. I should be farming but it is not safe. [85]

A 40-year-old widow with six children said:

My business is not working here in Bama because no one is interested in buying the vegetables I sell, because we are all so poor… When IOM [International Organization for Migration] gathered us for interviews, we complained of not even having food to eat, but still nothing has been done about it.[86]

A 34-year-old man who had relocated to Shuari with his family after Bakassi camp was shut down said that he refused to return to Bama, his hometown, because he heard from others there that the situation was not conducive to return. He said:

Even those who returned are suffering—there is lack of water, lack of food and no business going on there. I heard this from returnees I have been communicating with. Some of them are coming back to Maiduguri to look for something to do that will make them money.[87]

While there are humanitarian organizations providing support in displacement camps and to displaced persons in host communities in Bama, interviewees said that they have been unable to benefit from food assistance or support because the organizations are not registering new beneficiaries since the governor banned the distribution of food aid.[88]

WFP officials told Human Rights Watch that they made plans to increase contingency support for people moving, after the camp shutdowns in Maiduguri, to locations including Bama where the organization provides food support in displacement camps and to others in the community.[89] They said, however, it became clear from the government that those who arrived from Maiduguri would only be allowed to access livelihood support, not food support that WFP was offering,[90]

Human Rights Watch reviewed a letter sent by the Borno State government to humanitarian organizations banning the distribution of food and non-food aid in resettled communities and that government permission was needed to begin distributing aid in “new areas.”[91]

However, it is unclear if “new areas” was also intended to encompass to new beneficiaries, such as newly arrived displaced persons. Two aid workers said that humanitarian organizations had unevenly implemented the government’s instructions.[92] The deputy director of an organization providing food aid in Maiduguri said he had heard some other organizations were not allowed to expand their beneficiaries’ list to help those newly arrived. Others, including his group, were able to navigate existing relationships with SEMA officials in some locations to be able to provide assistance to new arrivals.[93]

A 40-year-old mother of seven, who moved to Bama after Bakassi Camp was closed in 2021, said:

Our condition here is critical...we can’t afford three meals, we can’t even afford two, we just eat once a day. The quality of the food we eat even that once a day is bad. We are just managing with what we see [find]. We get some cheap leaves to cook soup, with no protein like meat or fish. We put beans in the soup sometimes when we can afford it...I am seriously concerned that my children don’t have enough nutritious food to eat and grow.

Humanitarian workers expressed frustration at the ongoing situation. The deputy director working in Maiduguri said that, “The impact of the government’s actions is already scary, and we foresee a very big crisis, in which children will be affected the most. Nutrition is at stake here and it has a lifetime impact on children.” He also expressed concern that the camp closures and the ban on aid appear to have been carried out without consideration for the situation on the ground, in reference to the dire needs of displaced people.[94]

Between October and December 2021, the UN Food and Agriculture Organization and several other groups, along with the Nigerian Federal Ministry of Agriculture, carried out a joint analysis of food security in parts of Nigeria. The resulting report highlighted that communities in Borno State had reached the crisis stage of acute food insecurity during this period.[95]

A key recommendation of the report was for government and humanitarian agencies to sustain the implementation of life-saving interventions of food assistance and unconditional cash transfers to the vulnerable populations in affected areas.[96]

WFP officials told Human Rights Watch that two communities—Magumeri and Gubio LGA— where they had to stop providing food support following the government’s ban on aid in resettled communities were among those listed in the report as reaching the highest level of food insecurity.[97] They said they raised concerns around the need for WFP to be allowed to continue supporting these communities but were told by state government officials that the government would fill gaps to provide support if necessary.[98] One WFP official said, “We can’t access these places without the government’s consent. They provide us with security, with escorts in order for food support items and even personnel to be able to reach these areas. So if they say we can’t go there to provide support, we really can’t.”[99]

Inadequate Shelter

Many displaced families have ended up living in worse physical conditions after they were forced to leave the camps. After leaving they had little or no access to water, sanitation, and health facilities, in contrast to the basic level of access that humanitarian organizations had provided in the camps.

In the camps, displaced families had either been living in tarpaulin tents or in rooms in existing structures that had been built for various purposes—such as housing estates for teachers, civil servants, and other citizens—but which were never occupied before the site’s conversion to a displacement camp.

Human Rights Watch research indicates that many families who remained in Maiduguri after they were forced to leave the camps live in precarious conditions in poorly constructed thatch tents, which could not withstand the elements. Such tents do not provide adequate shelter from the rain, a major problem during the rainy season (approximately June to September but the downpour sometimes begins as early as April) in Borno State.

A 35-year-old woman with seven children had moved with her family to Musari, a low-income neighborhood in Maiduguri, after Bakassi camp was shut down in November 2021. She said that they were unable to afford rent in Maiduguri, so they bought materials and constructed a thatch tent and a pit latrine on land they were permitted to use by her husband’s friend. She said, “I prefer life in the camp, because there I had a structure over my head that was not leaking, but now our thatch house is not good enough to protect us from the rains. When it rained last night, we could not sleep, we were wet and all our things were wet, the roof even fell.”[100]

A Human Rights Watch researcher visited this family and another family in Musari that also obtained permission to build a tent on another privately owned plot of land. The researcher observed that heavy rains had penetrated the thatch and destroyed household items the night before, including a foam mattress, bags of clothes, and children’s schoolbooks.

Displaced families who returned to Bama after they were forced to leave camps in Maiduguri said that they found that their homes, which had been destroyed during the conflict, were not among those the government had renovated or rebuilt.[101]

Two interviewees said because of this, they could only provide shelter for their families by building tents from tarpaulin and zinc on the lands where their homes used to be. Another two said they had no choice but to move into their partly destroyed homes with their families, while two others said they moved into homes which had been rebuilt but belonged to other people who were yet to move back to Bama.[102]

A 40-year-old mother of seven in Bama who was forced out of Bakassi camp said:

We are staying in one of the houses reconstructed by the government. We just went and occupied the house; we don’t even know the owner. We were one of the lucky ones, others don’t have this opportunity, they are living in tents. I have fears that the owner will come and ask for his house back. If he does, we will have to move out and build a tent.[103]

IV. Concerns Around Impending Camp Shutdowns

Internally displaced persons in camps set to be shut down told Human Rights Watch that authorities did not provide information on possible areas of relocation. They said they feared they could end up relocating to places where they would face worse conditions than those in the camps.

A 45-year-old mother of two children, who had lost three other children to abductions and killings in Konduga at the peak of the fighting, said:

I don’t know anything about where I can go with my family if Dalori, the camp where we have lived for eight years, is closed. My village in Konduga community no longer exists as a result of the conflict and I am not comfortable going to a place that is not my original place of living… I will not feel safe... But if the government can assure us that we will be taken to places with schools, water, a house, safety, and livelihood sources to live a normal life, this will make me comfortable. But not a situation where the government will go and abandon us in a place we don’t know, as I suspect they will.[104]

A 40-year-old woman living in Gubio camp, which was set to be shut down, said:

My main concerns are around lack of food, lack of water, and leaving the camp to a place I have no idea about or where I don’t know what to expect. I have twin 13-year-old girls, I also have children between the ages of 9 and 4. Dealing with these concerns for myself and my kids is hard…This is giving me anxiety, it is unfair, and I try not to think of it. I am not finding it easy at all. We already suffered at the hands of Boko Haram before now and we are still suffering at the hands of the government.[105]

Other interviewees expressed concerns around the state of infrastructure in their home communities and fear of re-traumatization linked to the impact of the attacks they had witnessed and fled from in their communities. A 35-year-old widow with five children who was living in Dalori camp before it was shut down in August 2o22 said:

Going to Bama is not an option because of my past experiences there. It will be too traumatic for me to go back to the place where I lost two husbands as a result of the conflict. Also, I have a child who is getting treatment for kidney stones in the hospital here in Maiduguri, and he won’t be able to get that treatment in Bama where there are limited health services.[106]

Interviewees in the remaining camps said that they want to return to a life of dignity in their communities, but they called on the Borno State government to prioritize their safety and well-being by allowing them stay in the camps until they can support themselves or provide food assistance in the communities they return to.

A 65-year-old man living in Gubio camp with his family of seven said:

If the government will take us to a place where there is shelter, where there is food, farmland, that will be good for us, not a place where we will still face all these things [hunger and deprivation]. For now, I don’t think such a place exists or the government has made such arrangements anywhere.[107]

A 35-year-old widow who lived in Dalori I camp with her five children said:

The government should consider single parents like me in the camps… They should consider giving us stability, food security, and housing. There are also older people and children with no families. The government should prioritize their well-being over these plans to relocate [us] and shut down camps.[108]

The move to shut down camps and cancel food aid has left people feeling desperate and hopeless. In April 2022, prior to Dalori I camp’s closure in August, a 45-year-old man living there with his six children told Human Rights Watch that he had no idea where he would go when the camp was shut down because his hometown, Baga, was still inaccessible due to insecurity. He said he didn’t have any money to explore other options.[109] He expressed anger and frustration at the government:

I never imagined that this will be my life one day, that I will be defined by the decisions of the governor to be able to eat, to stay in one place or not stay in one place. I have no say…I have no idea what I will do if the camp is shut down. The circumstances when it happens will determine what I will do. Before the insurgency, I was doing well; now I have been reduced to nothing. As it is now, even prisoners have access to food, but we don’t. We are being punished for nothing at all with the ban on food distribution and plans to close camps. Is it our fault that we are victims of Boko Haram attacks?[110]

V. Government Motivations and Justifications for Closing Camps

Stabilization and Development Versus Risks and Needs

The government’s actions to shut down displacement camps and restrict aid to internally displaced persons appears linked to the Borno State Government’s 25-year Development Framework and 10-year Strategic Transformation Plan. These aim to make the state a “secured, competitive agri-business and commercial hub anchored on prosperous people and sustainable development.”[111] The governor in announcing the Strategic Transformation Plan in November 2020 stated that it would “drive stabilization, boost recovery efforts and stimulate growth across all sectors in the state.”[112]

Although not explicitly mentioned as a reason for shutting down camps in Maiduguri, the plan highlights the resettlement of displaced individuals and families in secure, affordable, and self-sustaining communities as a key indicator for success. It also aims to achieve voluntary resettlement of at least 50 percent of displaced persons by 2022 and the shutdown of all displacement camps by 2026.[113] The decision to shut down camps in Maiduguri within a year of adoption of the plan appears to have been an attempt by the government to show it was making progress on implementing the plan.

While it is important for the government to undertake and implement plans to develop and transform the state, which has suffered serious socioeconomic disruptions because of the prolonged conflict, the authorities should ensure that in doing so they are fully respecting the rights and well-being of the entire population, particularly marginalized groups including displaced persons.[114]

Two humanitarian workers in Maiduguri told Human Rights Watch that they believed the shutdown of the camps was in part in furtherance of stabilization and recovery projects that the government was working to implement with development partners such as UNDP and the World Bank.[115]

In 2019, UNDP initiated the Regional Stabilization Facility (RSF) in Nigeria, which aims to achieve immediate stabilization in Borno, Adamawa, and Yobe, the three states in the Northeast region directly affected by the Boko Haram conflict. The project seeks to stabilize seven target communities in the region by strengthening security and the rule of law, providing access to livelihoods, and reinstating essential infrastructure and basic services.[116] Among the seven communities, four are in Borno State—Banki, Damboa, Monguno, and Nagarranam. The communities were identified as target areas based on government priorities, their geopolitical importance for stability, capacities in maintaining minimum security, military and police presence for protection, level of damage incurred, and vulnerability to the insurgency.[117]

Government agencies at both the federal and state level played a focal role in planning and implementing the Regional Stabilization Facility, including decision-making on key strategic issues.[118]

In 2017, a $200-million World Bank Multi-Sectoral Crisis Recovery Project (MCRP) was initiated to rehabilitate and improve critical service delivery infrastructure, enhance livelihood opportunities, and strengthen social cohesion in Northeast communities affected by the Boko Haram conflict.[119] In May 2020, the project received additional financing of $176 million to scale up its efforts in supporting these communities.[120]

The implementing partners for the project include the Borno, Adamawa, and Yobe State governments and the Northeast Development Commission. The Northeast Development Commission was established in 2017 to manage funds allocated by the federal government and international donors for the resettlement, rehabilitation, and integration of victims of the conflict; for the reconstruction of roads, houses, and business infrastructure destroyed by the conflict; and for addressing other socioeconomic and developmental challenges in the Northeast.[121]

One humanitarian worker said: “The stabilization effort and the money coming in to fund it is one of the biggest factors pushing the agenda for people to return to these communities. The government is eager to show that their plan is working and they are achieving what they set out to do, when that is not exactly the case.”[122]

A representative of UNDP familiar with the RSF project told Human Rights Watch that although the project has recorded success in some key areas in the focus communities including improvements in security and rebuilding of some public infrastructure such as markets and police stations, the absorption capacity in these communities, which have been experiencing a huge influx of people because of the camp shutdowns, remains a concern.[123] He said:

Despite the work that has been done and is still ongoing, the infrastructure needed to respond to needs of returning IDPs is not at the capacity it should be and even getting government staff to run public infrastructure that have been rebuilt to provide services to people remains a challenge. In Banki [one of the project’s focus communities], tens of thousands of people have returned in the last one year to conditions that are concerning because of the camp shutdowns in Maiduguri. Many of them have moved out of the frying pan into the fire. UNDP’s talking points on the camp closures like other UN Agencies has been the same. That they should be done in line with the Kampala Convention.

In a December 2021 meeting of humanitarian representatives and Borno State government officials, including Governor Zulum, the state government shared an initial list of areas that it said had been rebuilt for civilian reoccupation with the involvement of some foreign humanitarian and development partners, including the UN.[124] The authorities further stated that humanitarian aid will not be allowed in these communities to foster self-reliance among the people there.[125]

Humanitarian workers, however, told Human Rights Watch that security and lack of adequate infrastructure including houses and livelihood opportunities are still issues for concern in some of these communities.[126]

In Marte, one of the communities the authorities indicated had been rebuilt and was safe for return, nine civilians were killed by insurgents on January 1, 2022 while they were out searching for scrap metal to sell, according to an internal report by a humanitarian organization.[127] Three days later, an attack by the insurgent group ISWAP on military forces killed at least 10 people including civilians.[128] In February, airstrikes by the Nigerian military in the same community killed an estimated 40 insurgents.[129] Attacks against civilians and the ongoing hostilities between the insurgents and the military continue to put lives at risk.

Ajiri, one of the first locations to which displaced people were returned in 2020, has also since experienced multiple attacks by Boko Haram.[130] In May 2021, at least 10 civilians were killed and several others injured during clashes between suspected ISWAP fighters and security forces.[131]

In November 2021, the Borno State attorney general stated that the government had over the prior three months facilitated the return of 1,500 displaced persons to Baga, another community highlighted in the list. However, he admitted that livelihoods activities such as fishing and farming in the area were limited due to insecurity, which he said the government was working to address.[132] Information provided by a humanitarian organization to Human Rights Watch on the situation in Baga indicated that those who recently relocated there following the camp closures do not have access to any assistance and have limited to no possibility of fishing or farming due to the security restrictions.[133]

Apart from safety and security, humanitarian workers have also raised concerns that the government has not built or rebuilt enough homes and infrastructure such as schools and hospitals to adequately address the needs of people who want to return to these places.[134] In the case of Baga, the Borno State attorney general said the government had built only 200 homes for the 1,500 displaced people who returned there and indicated that the government had yet to construct hospitals to meet health needs of the returnees. [135]

Humanitarian workers expressed other concerns, including worsening food security and vulnerability because of the state government’s approach. They described the futility of their efforts during various engagements, including their bimonthly humanitarian coordination meetings, to urge state authorities to reconsider their approach and give greater priority to the needs, rights, and legitimate interests of displaced persons. They also expressed frustration with the UN humanitarian leadership in the country, which according to them failed to support the humanitarian community in pushing back against the camp closures and ban on aid.[136]

Matthias Schmale, the UN Resident and Humanitarian Coordinator in Nigeria, told Human Rights Watch in May 2022 that the Borno State governor had a compelling vision for the state in trying to end displaced people’s years of dependence on humanitarian aid, and that the UN had a duty to support this vision, along with UN duties to address priorities such as humanitarian action and human rights. He said:

It is too little to say the process [employed by the state government] is wrong so the outcomes will be wrong… some people are worse off but not all. I need compelling evidence to be able to go to the governor and make a case about the impact of the camp closure and restrictions on aid and I don’t have that yet.[137]

This report has sought to demonstrate the detrimental impact of the camp shutdowns and the impact and expected impact on camp residents and their families.

The UN, including its representatives in Nigeria, could play a critical role in responding effectively to mitigate and prevent harms to internally displaced persons in Borno State. Rather than waiting to see if the government’s plans and actions will lead to future disastrous consequences, the UN should engage proactively and productively to ensure they do not.

Mixed Messages

Borno State authorities have sent mixed messages regarding their decision to shut down the camps. When Governor Zulum first announced the shutdowns in October 2021, he said the decision was informed by the recent improvement in the security situation in the state, highlighting that it was safe for displaced people to return to the communities that they had fled as a result of the conflict.[138] That same month, however, the governor stated that two local government areas, Abadam and Guzamala, were under the control of the armed group ISWAP.[139] He also expressed concern over the growing presence of ISWAP in the state. Recent reports of attacks against military forces and civilians—including an attack in Rann in May 2022 where insurgents killed over 50 people clearing their farmlands and fetching firewood—also indicate that parts of the state remain insecure.[140]