Help Wanted:

Abuses against Female Migrant Domestic Workers in Indonesia and Malaysia

Appendix A:Example of a Biodata for an Indonesian Migrant Domestic Worke

Appendix B:Standard Contract for Domestic Workers in Malaysia

Appendix C:Requirements for Hiring a Domestic Worker in Malaysia

Appendix D:Standard Contract for Filipina Domestic Workers in Malaysia

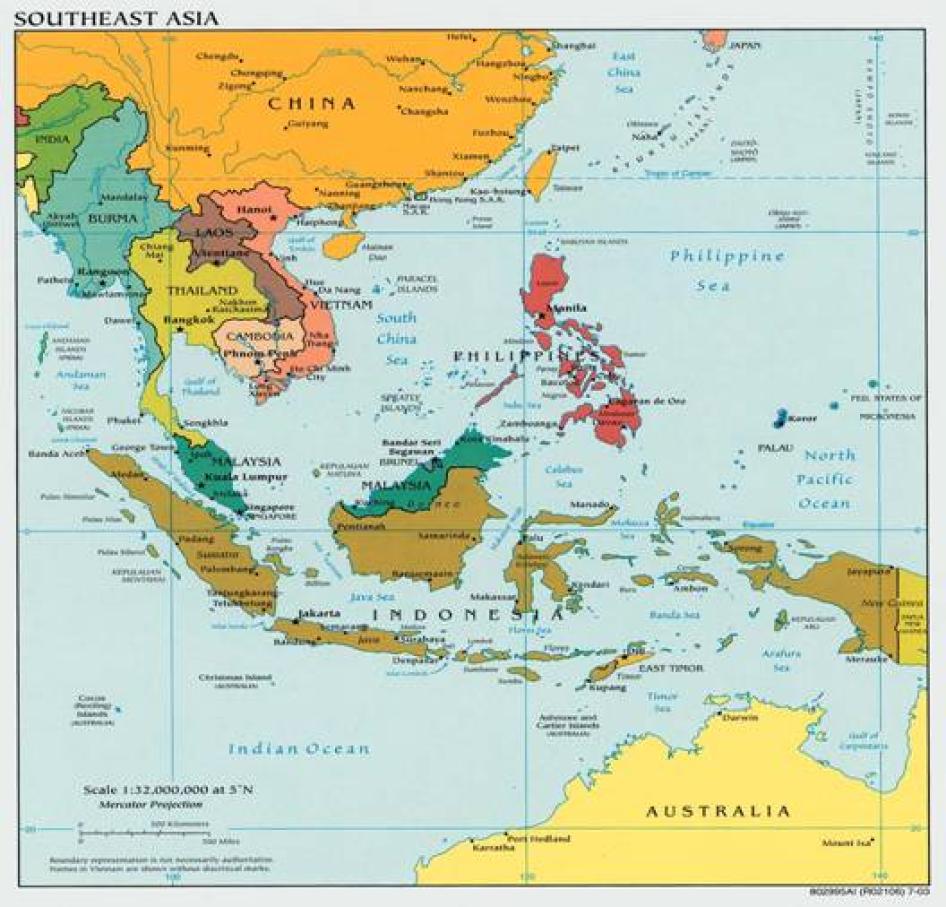

Map 1:Map of Southeast Asia

Map 2:Migration Flows between Indonesia and Malaysia

(Arrows show migration flows from Indonesia to transit points into Malaysia, which is shaded.)

I.Summary

The agent came to my house and promised me a job in a house in Malaysia He promised to send me to Malaysia in one month, but [kept me locked in] the labor recruiter's office for six months.I think one or two hundred people were there.The gate was locked.I wanted to go back home.There were two or four guards, they carried big sticks.They would just yell.They would sexually harass the women.

-Interview with Fatma Haryono, age thirty, returned domestic worker, Lombok, Indonesia, January 24, 2004

I worked for five people, the children were grown up.I cleaned the house, the kitchen, washed the floor, ironed, vacuumed, and cleaned the car.I worked from to every day.I never had a break; I was just stealing time to get a break.I was paid just one time, 200 ringgit [U.S.$52.63].I just ate bread, there was no rice [for me].I was hungry.I slept in the kitchen on a mat.I was not allowed outside of the house.

─Interview with Nyatun Wulandari, age twenty-three, returned domestic worker, Lombok, Indonesia, January 25, 2004

In May 2004, graphic photographs of the bruised and burned body of Nirmala Bonat, a young Indonesian domestic worker in Malaysia, were splashed across newspapers in Southeast Asia.In a case that drew international attention and outrage as well as a prompt response by both the Malaysian and Indonesian governments, Bonat accused her employer of brutally beating and abusing her.

Many Indonesian domestic workers confront the risk of exploitation and abuse at every stage of the migration cycle, including recruitment, training, transit, employment, and return.Unlike Bonat, these women and girls have little opportunity for redress and their abuse is hidden from public scrutiny.Labor agencies in Indonesia and Malaysia control most aspects of the migration process with virtually no oversight from either government.

This report provides a comprehensive account of the conditions faced by migrant domestic workers, detailing their experiences from initial recruitment in their villages in Indonesia to their return home from Malaysia years later.Based on over one hundred firsthand accounts, it illustrates the endemic and often severe abuses that Indonesian domestic workers experience.

In Indonesia, prospective migrant workers secure employment in Malaysia through both licensed and unlicensed labor agents who often extort money, falsify travel documents, and mislead women and girls about their work arrangements.In both Indonesian training centers and in Malaysian workplaces, women migrant domestic workers often suffer severe restrictions on their freedom of movement; psychological and physical abuse, including sexual abuse; and prohibitions on practicing their religion.Pervasive labor rights abuses in the workplace include extremely long hours of work without overtime pay, no rest days, and incomplete and irregular payment of wages.In some cases, deceived about the conditions and type of work, confined at the workplace, and receiving no salary at all, women are caught in situations of trafficking and forced labor.

Indonesia and Malaysia have failed to protect Indonesian domestic workers and have excluded them from standard protections guaranteed to other workers.Indonesia lacks an adequate system for monitoring labor recruitment agencies or training centers.Malaysia's employment laws do not extend equal protection to domestic workers, leaving their work hours, payment of overtime wages, rest days, and compensation for workplace injuries unregulated.The Malaysian government leaves the resolution of most workplace abuse cases to profit-motivated labor suppliers, who are often accused of committing abuses themselves.

In May 2004, the two countries announced they would negotiate a new Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) on Indonesian domestic workers in Malaysia. This is an important commitment and this report provides suggestions on the terms that any such MoU should include. Such a bilateral agreement, however, can address only a portion of the measures that the two governments must undertake if they are to provide meaningful protection to migrant domestic workers.Each government must also review and amend domestic employment and immigration laws, provide resources for support services, create policies and monitoring mechanisms to regulate the practices of labor agents and employers, and train government officials and law enforcement bodies to enforce these protections.

There are approximately 240,000 domestic workers in Malaysia, and over 90 percent of them are Indonesian.Due to the hidden nature of work in private households, the lack of legal protections, the limited number of support services and organizations, and the control exerted over domestic workers' movements in Malaysia, only a small proportion of abused domestic workers are able to register complaints or seek help.Close to eighteen thousand domestic workers escaped or ran away from their Malaysian employers in 2003, which both government authorities and NGOs attribute in large part to abusive employment practices.

Indonesian women seeking employment in Malaysia encounter unscrupulous labor agents, discriminatory hiring processes, and months-long confinement in overcrowded training centers before they ever reach Malaysia.In order to pay recruitment and processing fees, they either take large loans requiring repayment at extremely high interest rates or the first four or five months of their salary is held as payment.Labor recruiters often fail to provide complete information about job responsibilities, work conditions, or where the women can turn for help.Women expecting to spend one month in pre-departure training facilities in Indonesia are often trapped in heavily-guarded centers for three to six months without any income.Some migrant domestic workers are girls whose labor agents altered their ages on their travel documents.

Indonesian domestic workers employed in Malaysia typically work sixteen to eighteen hour days, seven days a week, without any holidays.Most have no significant time to rest during the day.Those who care for children in addition to their cleaning responsibilities report being "on call" around the clock.An Indonesian domestic worker typically earns 350-400 ringgit (U.S.$92-105) per month, half the amount a Filipina domestic worker earns.Given that most work at least fifteen hours a day, every day of the month, this amounts to less than one ringgit (U.S.$0.25) per hour.Employers often give their domestic workers their wages in one lump sum only upon completion of the standard two-year contract; many fail to make complete payments or to pay at all.

Indonesian domestic workers confront numerous legal and practical obstacles that impede their ability to leave abusive situations or to seek redress.Employers and labor agents routinely hold workers' passports.Malaysian immigration policies tie domestic workers' employment visas to their employer, often trapping them in exploitative situations, as escaping means they lose their legal immigration status.Police and immigration authorities summarily detain and deport workers caught without valid work permits, often without identifying cases of abuse or trafficking.Furthermore, the employers of most domestic workers interviewed for this report forbade them to leave the house, use the phone, or write letters.This isolation meant that many did not have access to information, support services, or individuals who could help them.Domestic workers who break their two-year contract early must pay for their own return travel to Indonesia. Because employers routinely withhold their salaries, many women workers are unable to pay this fare.They either complete their contracts while enduring abusive working conditions or risk working without legal status to earn money for their trip home.

Around the world, female work in the private sphere is typically not valued as an economic activity nor acknowledged as work requiring public regulation and protection.The situation of Indonesian domestic workers in Malaysia reflects this global bias.Indonesian migrant domestic workers currently have little protection under national laws and bilateral labor agreements.Although, as noted, Indonesia and Malaysia are negotiating an MoU on domestic workers, they previously excluded such workers from a major MoU on migrant workers signed on May 10, 2004.Malaysia's national employment laws also exclude domestic workers from protections provided to other workers.In Indonesia, the Indonesian parliament, a consortium of migrants' rights groups called KOPBUMI, and the University of Brawijaya based in Malang, East Java, have drafted three different versions of a new piece of legislation to protect overseas workers.Before a migrant workers' bill can be debated by Parliament, the Indonesian president must assign a ministry to take the lead on the legislation.At this writing, the president had not acted and the timeline and eventual enactment of a migrant workers' law remained uncertain.

Malaysia and Indonesia are failing to uphold their international human rights obligations under a variety of treaties, including the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) and the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC).Both Malaysia and Indonesia have ratified International Labor Organization (ILO) conventions on forced labor (Convention 29), protection of wages (Convention 95), and the worst forms of child labor (Convention 182).They should also ratify and enforce important international treaties on human rights and migrants' rights including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), theInternational Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families (Migrant Workers Convention), and the Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children, Supplementing the United Nations Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime (Trafficking Protocol).

This report is based on 115 in-depth interviews conducted in Indonesia and Malaysia in January and February 2004, as well as several months of background research.Human Rights Watch interviewed fifty-one Indonesian women currently working as domestic workers in Malaysia or who had left their employment in the previous twelve months.We also conducted sixteen interviews with Indonesian and Malaysian government officials.In Indonesia, these included officials from the Ministry of Manpower and Transmigration, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Ministry of Women's Empowerment, and the National Commission on Violence against Women.In Malaysia, these included officials from the Immigration Department, the Ministry of Human Resources, the National Human Rights Commission (SUHAKAM), and the Indonesian embassy in Kuala Lumpur.We conducted twenty-seven interviews with NGOs, lawyers, and United Nations agencies, and an additional thirteen interviews with Malaysian employers and labor agencies in Indonesia and Malaysia.

All names and identifying information of migrant workers we interviewed have been changed to protect their privacy and to prevent retaliation. In conformity with the CRC, this report uses "child" to refer to anyone under the age of eighteen.

Key Recommendations

The employer should not treat Indonesians badly, because we're still human.We have a heart and feelings.They should respect us too.They should not treat us badly.For all the mistakes [for which] we get hit, we are human.

-Interview with Riena Sarinem, age thirty, domestic worker, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, February 25, 2004

This report documents the routine abuse that women migrant domestic workers confront both during recruitment and training in Indonesia and in the workplace in Malaysia.Labor agencies control the migration process in both countries with little oversight from either government.Migrant domestic workers suffering forced confinement, physical violence, and unpaid wages have little hope for redress.Neither Indonesia nor Malaysia has legislation protecting the rights of migrant workers, and Malaysia's employment laws deny domestic workers the basic protections assured to other workers.

The governments of Malaysia and Indonesia should act decisively and quickly to respect fully the rights and dignity of Indonesian migrant domestic workers. Our central recommendations are listed below, and a full set of more detailed recommendations, addressed to both the Malaysian and Indonesian governments as well as to actors in the international community, may be found at the end of this report.

- Indonesia and Malaysia should actively protect and monitor the treatment of women migrant workers instead of abdicating these responsibilities to labor agents.This requires guidelines for labor agencies, more careful oversight of the work of such agencies, and enforcement mechanisms that include imposition of substantial penalties on agents who abuse workers or otherwise violate the guidelines.

- Malaysia should amend its employment and immigration laws to provide migrant domestic workers full protection under the law.Malaysia should amend its laws to facilitate civil lawsuits and the prosecution of criminal cases against abusive employers and to better respond to the needs of victims of abuse or trafficking.

- Indonesia should enact legislation on the protection of migrant workers.The government should better regulate and monitor recruitment practices and pre-departure training centers.The government should provide a range of services for returning migrants who have suffered abuse, including health care, legal aid, counseling, and reintegration programs.

- Indonesia and Malaysia should commit to negotiating a bilateral agreement on domestic workers that contains a standard contract with provisions on their hours of work, rest days, and pay; systems for monitoring training centers and places of employment; and plans on cooperation to provide services to survivors of abuse.This agreement should also protect domestic workers' rights to freedom of movement and freedom of association.

II. Background

Labor Migration in Asia

According to the International Labor Organization (ILO), there are approximately eighty-one million migrant workers worldwide, and of these, twenty-two million work in Asia.[1]Women comprised approximately half of all migrants worldwide for several decades, including in Asia, but were generally a small proportion of migrant workers.This pattern has been shifting since the late 1970s, most dramatically in Asia.[2]An estimated flow of 800,000 Asian women workers migrate each year, and this number is increasing steadily.[3]

The feminization of Asian labor migration is most marked in Indonesia, the Philippines, and Sri Lanka, where the majority of workers who migrate abroad for work are women.For example, in 2002, the Indonesian Ministry of Manpower and Transmigration, responsible for overseeing Indonesia's labor policies, recorded that 76 percent of all legal overseas Indonesian migrant workers were women.[4]Women migrant workers are concentrated in low-paying, poorly protected sectors such as domestic work and sex work.[5]

In 2001, migrant workers from developing countries sent home U.S.$72 billion, the second largest source of external revenue after foreign direct investment.[6]For sending countries like Indonesia, the Philippines, Sri Lanka, India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Vietnam, and Thailand, the "export" of labor has become an increasingly important strategy for addressing unemployment, generating foreign exchange, and fostering economic growth.Indonesia records up to U.S.$5.49 billion in remittances from migrant workers per year.[7]Indonesia, along with many other countries, includes targets for the numbers of workers it hopes to send abroad in its five-year economic development plans.Indonesia's targets have risen rapidly over time:in the economic development plan for 1979-84, the target was 100,000 workers; in the economic development plan for 1994-99, the target was 1.25 million workers; and in the economic development plan for 1999-2003, the target was 2.8 million workers.[8]

The most popular destination for Asian migrants has shifted from the Middle East to other Asian countries whose economies have boomed in recent decades.In 1990, for every migrant worker from Indonesia, the Philippines, or Thailand employed in other parts of Asia, there were three working in the Middle East.By 1997, destinations such as Malaysia, Singapore, Japan, Hong Kong, and South Korea had surpassed the Middle East.[9]These countries rely upon migrant workers to fill labor shortages that arise when the domestic labor force cannot meet the labor demands created by their fast-growing economies, or when their citizens are unwilling to take up low-paying, labor-intensive jobs with poor working conditions.

Although Asian migrants include highly-skilled professionals in management and technology sectors, the vast majority remain workers employed in jobs characterized by the three D's:dirty, difficult, and dangerous.Unable to find adequate employment in their home countries and lured by promises of higher wages abroad, migrants typically obtain jobs as laborers on plantations and construction sites, workers in factories, and maids in private homes.Many of these jobs are temporary and insecure-approximately two million Asian migrant workers each year have short-term employment contracts.[10]

Indonesian Migrant Workers in Malaysia

Malaysia relies upon migrant workers from Indonesia, Bangladesh, the Philippines, India, and Vietnam to meet labor demands.Indonesians are the largest group of foreign workers (83 percent) and have a long history of working in Malaysia.[11]They fill sectoral labor shortages created by Malaysia's economic policies:seeking to reduce economic disparities between the Malay and ethnic Chinese populations, Malaysia instituted its "New Economic Policy" in 1971 which aggressively pursued export-oriented industrialization and public sector expansion.The policies resulted in urban job growth and a mass migration of rural Malaysians to the cities.Industrial growth also led to an increase in demand for labor in manufacturing and construction that could not be met by the domestic workforce.By the early 1980s, the scarcity of labor in the agricultural sector and the heightened demand for domestic workers among an expanding middle class catalyzed a surge of migrant workers.

According to Indonesian government records, approximately 480,000 Indonesians migrated in 2002 for overseas work.[12]Migrants to Malaysia find jobs in domestic work (23 percent), manufacturing (36 percent), agriculture (26 percent), and construction (8 percent).[13]Two million Indonesians may currently be working in Malaysia, but the exact number is difficult to verify as more than half may be undocumented workers without valid work permits or visas.[14]

Indonesians in Malaysia make up the largest irregular migration flow in Asia and globally are second only to Mexicans entering the United States.[15]During an amnesty that regularized the immigration status of undocumented workers in 1992, fifty thousand undocumented workers came forward.[16]In 1997, 1.4 million Indonesians residing in Malaysia voted in the Indonesian elections, causing Malaysia's Immigration Department to estimate that 1.9 million Indonesians lived in Malaysia at the time.[17]Many migrants choose to enter Malaysia through unofficial routes since migrating through licensed labor agencies can result in long delays and requires cumbersome bureaucratic procedures, while unofficial arrangements can take just days.However, there is greater risk of corruption and abuse with the unlicensed labor agents, and less protection if workers face problems with their employers or government authorities.

Over time, the Malaysian government has alternated between tightening immigration policies, causing mass outflows of foreign workers, and loosening them through development of bilateral agreements and amnesties.A number of measures taken by Malaysia over the past few decades, including the Medan Agreement of 1984, which introduced regulations for recruiting Indonesian domestic workers and plantation workers, a November 1991-June 1992 amnesty for undocumented workers, and a 2002 amendment to the Immigration Act that established harsh punishments for immigration violations, have all failed to stem illegal migration or to protect the rights of migrants seeking work in households, manufacturing, construction, and plantations.[18]

Malaysia has made it a criminal offense for migrant workers to be present in Malaysia without a work permit or visa and has taken increasingly punitive measures, including caning, to deter and penalize such workers.[19]The local Malaysian population often blames both petty and violent crime on foreign workers.According to SUHAKAM, Malaysia's human rights commission, in January 2003, only three hundred out of 1,485 women in Kajang Women's Prison were Malaysian.The rest were foreign women, including migrant workers and trafficking victims.[20]The routine arrest, detention, and deportation of undocumented workers, regardless of the reasons for their undocumented status, means that migrant workers in abusive situations are less likely to attempt to escape, as they fear being caught by immigration authorities.

Domestic Work

Domestic work, or employment as a housekeeper or caretaker for children or the elderly, is poorly remunerated, and workers are particularly at risk of abuse because of their isolation in private homes.Migrant domestic workers encounter abuses not only in the workplace, but also at many stages of the work cycle, from susceptibility to trafficking at the recruitment stage and abuses at training centers in Indonesia, to poor conditions of detention and lack of access to health care if arrested without documents and detained.

Labor laws around the world usually exclude domestic work from regulation or provide less protection for domestic workers than for other workers, reflecting discriminatory social biases that create artificial dichotomies between work associated with men in the formal public sphere, and work associated with women in the private sphere.Malaysia's Employment Act of 1955 excludes domestic workers from regulations providing maternity benefits, rest days, hours of work, and termination benefits.

Policy-makers, employers, labor agents, and members of the public often view women's labor as domestic workers as a natural extension of women's traditional, unpaid role as mothers and care providers in the family, underplaying the contractual relationship between employer and employee.They do not address the range of working conditions that domestic workers may encounter, including the physical size, layout, and building materials of the house they must clean; the number of individuals they serve, including children in the employer's household; and the workload, which often involves juggling cleaning, cooking, caring for children, and caring for the elderly.

Legal labor migration from Indonesia is dominated by women domestic workers-According to the Indonesian government and the World Bank, in 2002, 76 percent of 480,393 overseas workers from Indonesia were women, and 94 percent of these women were employed as domestic workers in Middle Eastern, East Asian, and Southeast Asian countries.[21]These workers include girls who travel with falsified passports and employment visas.[22]According to Malaysian officials, there are currently 240,000 women migrant domestic workers in Malaysia and over 90 percent of them are Indonesian.[23]The "import" of domestic workers was in part a response to Malaysian women moving into more secure, higher-paying factory jobs.[24]

Most domestic workers who migrate to Malaysia come from East Java, Lombok, and Flores.The women whom Human Rights Watch interviewed cited financial necessity and a desire to support their parents and children as their primary reasons for seeking work in Malaysia.Some women stated that they were interested in seeing a different country and having new experiences, and that they saw Malaysia as a stepping stone to gaining the qualifications that could make them better candidates for more lucrative jobs in the Middle East, Singapore, or Hong Kong.Most were between the ages of seventeen and thirty-five, and had completed elementary or middle school.They chose domestic work because they did not have to pay any money up front, and they would receive free board and lodging in Malaysia, thereby, they believed, enabling them to save more money.[25]Labor agencies typically charge large processing and placement fees for other overseas work, for example, jobs in factories, restaurants, or plantations.

According to Malaysian immigration authorities, in the last four years, fifty-seven thousand domestic workers in Malaysia left their places of employment before the completion of their work contracts.Abuse in the workplace is one of the leading causes for workers to leave their employers.[26]NGOs in both Malaysia and Indonesia also reported handling cases of abuse of domestic workers.[27]

Trafficking

Every year, an estimated eight to nine hundred thousand people are trafficked across international borders into forced labor or slavery-like conditions.[28]Although exact figures are difficult to obtain, there is substantial evidence that trafficking of women and children in Asia is a particularly serious and entrenched phenomenon.Governments, NGOs, and international organizations have documented trafficking of individuals into forced labor, including forced prostitution, from Burma to Thailand, Indonesia to Malaysia, Nepal to India, and Thailand to Japan, among others.[29]

Trafficking includes all acts related to the recruitment, transport, transfer, sale, or purchase of human beings by force, fraud, deceit, or other coercive tactics for the purpose of placing them into conditions of forced labor or practices similar to slavery, in which labor is extracted through physical or non-physical means of coercion, including blackmail, fraud, deceit, isolation, threat or use of physical force, or psychological pressure.[30]For a more detailed discussion of the definition of trafficking, see the "International Legal Standards" chapter of this report.

Migration and trafficking are interlinked, as traffickers often exploit the processes by which individuals migrate for economic reasons.Through corrupt government officials, unscrupulous labor agents, and poor enforcement of the law, economic migrants may be deceived or coerced into situations of forced labor and slavery-like practices.Indonesian trafficking victims may be found in situations of forced domestic labor and other forms of forced labor, forced sex work, and forced marital arrangements.[31]In its annual report for 2003, Malaysia's National Human Rights Commission (SUHAKAM), addressed the issue of trafficking victims forced into sex work, noting:"Indonesian girls and women are usually brought in as domestic maids and then 'sold' by their agents to work in discos and entertainment outlets to entertain men, including being forced to provide sexual services."[32]

No reliable estimates exist for the numbers of individuals trafficked from Indonesia to Malaysia each year.Although there are hundreds of confirmed cases, most groups working on the issue suspect the actual number runs into the thousands.According to the 2004 U.S. Trafficking in Persons Report, of 5,564 women and girls arrested and detained in Malaysia for suspected prostitution in 2003, a large number were probably trafficking victims.[33]Many anti-trafficking efforts have continued to focus on women and children trafficked only into forced prostitution, and police, immigration authorities, and other relevant actors still fail to identify individuals trafficked into other forms of forced labor.

Trafficking victims in Malaysia have little hope of receiving protection or aid from the Malaysian authorities, including services or remedies through the justice system.Despite a revision of the penal code in Malaysia, trafficking victims are often treated without distinction from undocumented migrants, meaning they may be detained, fined, and deported without any access to services or redress.There are few shelters and services for the victims of trafficking who are identified, and many are repatriated without pursuing criminal or civil cases because of the time, expense, and bureaucracy involved.

Repression of Civil Society in Malaysia: The Irene Fernandez Case

The repression of civil society in Malaysia makes the exposure of human rights abuses against women migrant workers, the provision of services, and advocacy for change extremely difficult.The case of Irene Fernandez, the director of Tenaganita, a prominent migrants' rights group in Malaysia, underscores the atmosphere of intimidation and coercion that has been created by the state.Fernandez is an internationally recognized human rights advocate who has worked to reform laws on rape and domestic violence, provide support services to migrant workers and trafficking victims, and create programs to improve health services for HIV-positive women.[34]

Tenaganita published a report in 1995, "Abuse, Torture and Dehumanised Treatment of Migrant Workers in Detention Camps," that detailed abuses against migrant workers in Malaysia's immigration detention centers, including physical abuse and inadequate food and water.[35]Instead of prosecuting or disciplining the officials responsible for these violations, the Malaysian government pressed charges against Fernandez in March 1996 for publishing "false and malicious" information about the Malaysian state under the restrictive Printing Presses and Publications Act of 1984 (PPPA).[36]The PPPA is but one of several Malaysian laws that do not adhere to international standards, and which the government regularly uses to clamp down on the basic rights of free expression, association and assembly.[37]

On October 16, 2003, after the longest trial in Malaysian history, and one that drained the resources of one of the few organizations helping migrant workers, Fernandez was convicted and sentenced to a year in prison, sending a chilling message to other human rights advocates.[38]Fernandez, free on bail pending appeal of the one-year sentence, has faced other forms of restrictions from the government, including recent denials of her application to travel abroad to speak at international conferences, on the grounds that she would "tarnish the image of the country" if allowed to travel abroad.[39]

The Status of Women and Girls in Indonesia

The high risk of abuse and the accompanying lack of government protection encountered by Indonesian migrant domestic workers are linked to women's status in both Indonesia and Malaysia.

The status of women and girls in Indonesia varies widely across the country, reflecting the diversity of ethnic group traditions and social expectations about the behaviors of men and women across the archipelago.Girls' rate of primary and secondary school enrollment is approximately equal to boys, but gender inequality still manifests itself in political participation and employment.According to the ILO, women in the workforce earned 68 percent of that of male workers.[40]In 2002, the government stated that 38 percent of civil servants were women, but that only 14 percent of these women held positions of authority.[41]

Violence against women and girls is a serious problem in Indonesia and takes many forms, including domestic violence, trafficking, sexual violence, and violence by armed forces in conflict areas like Aceh and Papua.[42]The narrow criminal code definition of rape as penile penetration has prevented many rape prosecutions against sexual violence perpetrators.In 2002 in Aceh, soldiers were not held accountable for raping women with bottles and other foreign objects.[43]Marital rape is not outlawed.

Access to redress through the criminal justice system, difficult for most Indonesians because of notorious corruption and inefficiency, is largely inaccessible to women and girls.The process to file a complaint is often lengthy and bureaucratic, and law enforcement officials may not be adequately trained or competent in handling sexual or domestic violence cases.In 2001 and 2002, less than 10 percent of the cases reported to four women's crisis centers in Jakarta were reported to the police.[44]

The Indonesian government has taken some steps to address violence against and exploitation of women; for example, the president established the National Commission on Violence against Women by decree in 1998, and the police have established women's desks in police stations around the country to provide gender-sensitive services to women and girls.[45]The government has also begun setting up crisis centers for victims of violence and drafting bills to protect migrant workers' rights, address domestic violence, and prevent and respond to trafficking.Many of these initiatives remain in their planning stages and have been slow to get enacted or implemented. For example, although the legislature initiated the bill on domestic violence six years ago, the House has yet to begin deliberations on it.[46]

Gender-based discrimination, though outlawed by the 1945 Constitution, continues both in the law and in social practice.Citizenship can only be passed through the father, meaning that children with Indonesian mothers and non-citizen fathers are not eligible for public services requiring citizenship, such as public school enrollment.Muslims have the right to choose whether civil law or Islamic law is applied to them, but the CEDAW committee has raised concerns about the extent to which Muslim women are able to make this decision freely.[47]The Islam-based family court system poses some disadvantages for women.For example, women bear a heavier burden of proof when seeking a divorce than men.

The Status of Women and Girls in Malaysia

Women's social, economic, and political roles have transformed over the past few decades, both influenced by and actively shaping Malaysia's politics and dramatic economic growth.Indicators on education and health show encouraging progress.For example, in 2000, school enrollment rates of males and females were approximately equal and 96 percent of all births were attended by a skilled health care provider.[48]The illiteracy rate among adult women dropped from 38 percent in 1980 to 17 percent in 2000, with only 2 percent of young women between the ages of fifteen and twenty-four being illiterate.[49]

Low levels of political participation and economic segmentation along class and ethnic lines marginalize women politically and economically.Women held 10 percent of the seats in the House of Representatives in 2003 and 26 percent of those in the Senate.[50]The second-largest political party, Parti Islam se-Malaysia (PAS), does not allow women to be candidates for the House of Representatives, but the party had three female senators in 2003.[51]

Ethnicity and religion intersect with gender in ways that adversely affect women's legal status and rights.The differences are especially marked in regard to the application of family law:Muslim women are governed by Muslim personal laws interpreted by separate systems of religious courts in each state; indigenous women from Sabah, Sarawak, and other parts of the country follow native customary law; and the rest fall under Malaysia's civil and criminal laws, including the 1976 Marriage and Divorce Act.[52]Women's organizations have protested discriminatory provisions in Muslim personal laws that prevent Muslim women from having equal rights in contracting marriage or obtaining a divorce.Two states, Kelantan and Terengganu, have passed bills to impose Islamic criminal law, or Hudood, which have raised concerns about the implications for women; for example, women and girls are confronted with discriminatory and prohibitive evidentiary requirements in cases of rape as they must provide four male witnesses.Adultery is criminalized, and if a rape victim is unable to prove her case, she may be at risk for being punished for making slanderous accusations or for adultery for having sexual relations outside of marriage.As of this writing, the federal government has consistently blocked enactment of these laws.[53]

Violence against women and girls is a serious problem in Malaysia.Women's Aid Organization, an NGO, estimated that there were over three thousand cases of domestic violence in 2003, and in a 1995 report estimated that 39 percent of Malaysian women have suffered from partner abuse.[54]Marital rape is not a crime.Furthermore, the Penal Code requires that visible evidence of physical injury exist to prosecute a domestic violence case, preventing survivors of sexual abuse without visible injury or who have suffered psychological abuse from pursuing legal remedies.The government amended the Penal Code to stiffen punishments for rape from five years of imprisonment to thirty years, caning, and a fine.[55]

III. Pre-Departure Abuses in Indonesia

The agent came to my house and promised me a job in a house in Malaysia, where I would earn two hundred ringgit [U.S.$52.63] per month.I would not have to pay anything, they would prepare my passport and would cut my salary for the first four months.I wanted to get the experience and to earn money.The agent promised to send me to Malaysia in one month, but [kept me locked in] the labor recruiter's office for six months.I couldn't go out.Many people, even if they got hurt or wanted to leave, they weren't allowed out.I think one or two hundred people were there.The food wasn't enough, they gave it twice a day.The gate was locked.I wanted to go back home.There were two or four guards, they carried big sticks.They would just yell.They would sexually harass the women.There were lots of girls there too [who suffered the same treatment].

-Interview with Fatma Haryono, age thirty, returned domestic worker, Lombok, Indonesia, January 24, 2004

Licensing of Labor Recruiters and Suppliers

Labor agencies control most aspects of migrant workers' recruitment, foreign work permit applications, training, transit, and placement with an employer with little or no oversight from either the Indonesian or Malaysian government.Indonesia requires that a domestic worker migrating legally find employment overseas through a licensed labor agency that helps her apply for a passport; obtain a temporary employment visa; obtain medical clearance; pay insurance and other fees; and learn housekeeping, child care, and language skills.Over four hundred licensed labor agencies operate in Indonesia, with countless more operating illegally.The four hundred licensed recruitment agencies generate an estimated U.S.$2 billion a year in revenue by charging migrants U.S.$1,500 each to migrate abroad, and some collect additional fees.[56]

The requirements for becoming a "housemaid" recruiter or supplier in either country are simply that the company be legally registered with the government and have a certain amount of financial viability, measured by their meeting minimum standards on the size of their bank accounts.[57]Aside from basic specifications on the accommodations for domestic workers who stay at the center for training, there are no guidelines or requirements on the quality of their services or the background or qualifications of their staff.

In Indonesia, the Ministry of Manpower and Transmigration issues licenses to labor agencies.Once an agency has a license, they do not have to undergo a review to renew it periodically.If the Ministry discovers the agency has been cheating workers or breaking the regulations, they can cancel or suspend the license.Since the Ministry does not monitor labor suppliers regularly or rigorously, the identification and penalization of agencies committing abuses is rare.Furthermore, NGOs report that owners and employees of suspended recruitment agencies may ignore the penalty and continue their operations by setting up new agencies under different company names and partner configurations.[58]One government official from the Ministry of Manpower and Transmigration noted that the government has limited power to sanction such agencies:

So far we have canceled eighteen licenses, and some are under suspension.Some of these companies had fake documents, for example, they had no bank deposit, and others took money from workers and didn't send them overseas.In our next bill, we hope to cover illegal recruitment.Our power is only to cancel or suspend the license, or use their deposit to pay the worker.In the new bill, we need to be able to give the penalty of prison time, because right now we don't have enough power.[59]

Pre-Departure Process and Transit

Women migrating to Malaysia for domestic work often first come into contact with a local labor recruiter from their village who promises them a certain salary, presents them with employment options, and offers to guide them through the recruitment process.These agents often receive a commission from larger labor agencies or extract a fee from the prospective migrant worker.These agents may help the worker get a health exam for medical clearance and a passport before they pass them on to a labor supplier in Jakarta or a transit point.

Malaysian law requires all migrant workers be tested for pregnancy, human immuno-deficiency virus (HIV), and other infections like malaria and tuberculosis before they arrive in Malaysia.The workers either pay for this health exam or the cost is included in their initial salary deduction.Employers and labor agents often re-test them upon arrival in Malaysia, as they have little faith that the documents from Indonesia are reliable.Prospective workers who test positive will be denied entry or deported if they test positive for pregnancy, HIV, tuberculosis (TB), malaria, leprosy, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), or drug use.One domestic worker, Nur Hasana Firmansyah, told Human Rights Watch,

I took a full medical exam, with a blood and urine test.They did not give me the results, they just told me I was "fit."I also took another exam in Jakarta.Pregnant women failed.They were sent back home, but if they wanted an abortion they could stay.Two girls had an abortion and three girls went back home.[60]

Most women interviewed by Human Rights Watch said they did not receive any information specifying the health conditions for which they were being tested.There were no procedures for protecting the confidentiality of test results, and generally the health clinic gave the exam results directly to the labor agent.Human Rights Watch found no official policy concerning counseling or care for those who test positive for STIs or other illnesses.Government officials, labor agents, NGOs, and domestic workers said that women who were pregnant were sent home, or in a few cases, given the option of getting an abortion.[61]In a few isolated cases, some workers who tested positive for HIV during their medical exams in Indonesia were referred to an Indonesian NGO that provides services for individuals living with HIV/AIDS.[62]

While other migrants who seek employment in plantations, factories, and construction often pay large fees up front, many women choose domestic work because there is no initial fee.Instead, they agree to have the first four or five months of their salary in Malaysia withheld.Women who find employment through illegal agents have to pay a large sum, usually 1.5-2 million rupiah (U.S.$183-244).They typically raise these funds by borrowing money from the agent, village moneylenders, family, or friends at usurious interest rates.Most of the women interviewed for this report who had borrowed money had to repay their lenders double the original amount of the loan.

A migrant domestic worker may pass through two or three different agents or companies before she travels to Malaysia.The local labor recruiter or "sponsor" will send her to a branch office of an agency or directly to the main office.These offices either have their own training facilities or contract out to another agency to hold and train prospective migrant workers.At this point, the agency may arrange for another health exam, will help her apply for a passport if she does not have one, request a temporary employment visa for the worker, pay for hospitalization insurance, and obtain approval from the Ministry of Manpower and Transmigration.The process is lengthy and contingent upon approvals from several government agencies.Indonesia also requires that women domestic workers undergo training in housekeeping, childcare, and Bahasa Melayu, the language of Malaysia, before they go to Malaysia.They must pass an exam before they are granted a visa.[63]While they are waiting for their paperwork to be completed and for a Malaysian agent to select them for employment, women migrant workers stay in holding or training centers for several months.

Malaysian labor agents and employers may contract domestic workers through licensed Indonesian labor suppliers, or they may illegally recruit directly through unlicensed agents or prospective workers themselves.Those who work with licensed Indonesian labor suppliers can choose domestic workers from written "biodata" forms containing photographs and biographical information about prospective workers (see appendix A for an example), or they may visit the holding and training centers in Indonesia to select women workers themselves.[64]The contempt with which Malaysian and Indonesian labor agents treated women workers is apparent in one Malaysian labor supplier's explanation of why he personally screens the prospective domestic workers in Indonesia's training centers.He told Human Rights Watch, "Malaysia is in the lowest category compared with Hong Kong, Taiwanthe good maids, the highly educated maids won't come to Malaysia.That's why I go to Indonesia, so they won't give me rubbish.But there is still some rubbish, I don't know why.Even in training centers, because of big numbers, the quality is totally zero."[65]

Once a woman has been selected for employment, she travels to Malaysia accompanied by either Indonesian or Malaysian labor agents, often with a small group of other workers.Human Rights Watch interviewed several women who experienced long journeys with unexpected stops in transit points.Some women who were promised plane tickets to Malaysia actually traveled by boat.Kusmirah Parinem told Human Rights Watch about her experience:

The agent had promised we would travel to Malaysia by plane, but instead we went on a thirteen-person boat.From Jakarta to Batam, I went by plane, and we stayed there for three days without food.From Batam to Malaysia we traveled by boat.I can't remember how many hours but I was very frightened.[66]

Corruption, Extortion, and Other Illegal Practices

The long duration, high cost, and complex requirements of recruitment through legal procedures have led to both corruption and increased illegal activity.Competition and unethical practices among profit-seeking labor suppliers and recruiters create an environment that undermines the effectiveness of the few existing regulations, compromising migrant workers' rights.In the past two years, dozens of labor recruitment agencies were found to be falsifying competency test certificates for migrant workers.[67]

A labor supplier in Jakarta told Human Rights Watch about the regular bribes and unofficial fees he pays to avoid delays in processing workers' documents and other interference with his business.He said that without such payments, the obstacles he would then encounter would place him at a disadvantage relative to other recruitment agencies in a highly competitive environment.He told Human Rights Watch:

There is competition between the PJTKI [recruitment agencies]-employers run to the labor supplier who is the cheapest and fastest.I give money to the media, social workerspolice.I give "entertainment money" to about ten people per month.We give to key people .We give, they don't ask.It adds up to about three or four million [U.S.$365-488] a month.[68]

The structure of labor recruitment in Indonesia increases the freedom and incentive local agents have to extort high fees from prospective migrant workers:in many cases, they work on commission for several different agencies and do not receive a regular salary.An Indonesian labor supplier based in Jakarta said, "We do not give [the branch office agents] a salary from Jakarta.They get money from the migrant workers and brokers.I don't know how much they get.I ask them not to take too much [from the workers]."[69]Local labor agents are often the first to provide information about the long and bureaucratic migration process to workers, making it easy for them to deceive workers about the amount of money they have to pay up front.Women migrating for domestic work through legal channels pay their fees through initial salary deductions in Malaysia and should have few, if any, financial obligations to their agents in Indonesia.Human Rights Watch interviewed women migrant domestic workers who paid large sums to their local labor recruiter, often resorting to borrowing money at high interest rates.[70]

The Indonesian government, through the Ministry of Manpower and Transmigration, requires each Indonesian migrant worker to pay U.S. $15 in insurance fees.Indonesian NGOs have criticized the insurance scheme for being vague.For example, the insurance covers hospitalization, but the maximum amount is not specified, and it remains unclear whether the insurance covers acts of abuse by employers.Workers only have one month after their return to Indonesia to make a claim.[71]Most migrant workers do not receive the coverage they are entitled to under this insurance scheme.The World Bank has commissioned a study in cooperation with the Indonesian government to discover how these funds are being used.As of early 2004, the whereabouts of these funds and their disbursement remained unclear.NGOs blame lack of transparency and accountability in the state treasury, the Ministry of Finance, and the Ministry of Manpower and Transmigration for the "disappearance" of these funds.[72]

The numerous and complicated procedures to send workers abroad, corruption among labor agents, and the absence of reliable information mean that many prospective migrant workers may think they are migrating legally, but actually, often unbeknownst to them, obtain fraudulent or incorrect documents at some point in the process.A labor recruiter in a village may be working for both licensed agencies and illegal agents simultaneously.In order to speed up the pre-departure process, a labor agent may promise to obtain a two-year temporary employment visa for a worker, but instead secure her a short-term visitor visa, making her vulnerable to falling out of status and encountering problems with the Malaysian immigration authorities.

In other cases, migrant workers may opt to seek employment through an illegal agent who can promise to send them abroad in a matter of days rather than months, and who can help them bypass the training and health requirements.Migrating through illegal agents typically places migrant workers at higher risk for abuse at all stages of the migration process and severely limits their access to redress.The governments of Malaysia and Indonesia do not handle complaints of unpaid wages and other labor rights violations from workers who migrated illegally.In Malaysia, such workers are also at risk of being arrested, detained, and deported under the immigration laws.

Lack of Information, Deception

The agent told me I would have to wait in Tanjung Pinang for one week, but in reality I was in Jakarta for three-and-a-half months.

-Interview with Hartini Sukarman, age twenty-four, returned domestic worker, Lombok, Indonesia, January 26, 2004

During the recruitment, training, and placement process, many women did not receive information about their employers' duties as required under the work contracts or immigration and labor laws in Malaysia. They also rarely learned where they could turn in case of problems.Only a few women that Human Rights Watch interviewed were even aware there is an Indonesian embassy in Malaysia and that they could turn there for help.Instead of providing information on options should the workers face abuse or other problems, labor agents barraged them with threats and lectures about their "obligations" not to run away, to obey their employer, and to work hard.

Human Rights Watch documented some cases of labor agents misleading workers about the amount of time they would spend at a training center, the rate of their monthly salary, and their workload.One woman told Human Rights Watch, "I was at the training center for five months and twenty days.I didn't know I'd be there for so long.The agreement was that I would wait for one or two months.The agreement was that if I passed the medical check-up they would return my money-I had paid 500,000 rupiah.But the sponsor didn't return my money."[73]

Human Rights Watch interviewed women workers who reported that their labor agent confiscated any contact information they had, like phone numbers of relatives and friends.The only person workers could contact was their agent, and if they came through illegal channels, their agent often disappeared or changed phone numbers.[74]Several women domestic workers reported that even if they were able to contact their agent, they did not receive the needed assistance.For example, Nur Hasana Firmansyah told us, "My [male] employer always tried to hug me.I decided to call my agent in Batam, but he didn't want to pick me up."[75]Women who found themselves in abusive workplaces felt they had no options and were left powerless and trapped.

Most of the women that Human Rights Watch interviewed knew little about the labor agencies they used to migrate to Malaysia.Many said they could not recall the name of their labor agency.The only information they had was the first name of the labor agent.Often they had few or no details about where they were staying aside from the name of the city.Some were unsure whether the labor agency they used was licensed or not, though educated guesses could be made from other information they provided, as in the case of Latifah Dewi.She described an experience she had while at a training center:"The police often came and all the women had to get in the house.They would let just one girl meet the police.If the police did an operation and asked the girl, 'are there many people in the house?', she had to tell them, 'I am alone.'I don't know if the agency was licensed or not."[76]

Most women reported signing a work contract, but never received their own copy.Many labor agencies only showed contracts to women migrant domestic workers briefly so they could sign them before they left the training or holding centers.Most women workers reported to Human Rights Watch and other Indonesian NGOs that they did not receive a full explanation of the content of the work contract, were not given an opportunity to raise questions, or to show the contract to legal counsel, family, or friends for discussion.[77]

Based on copies of contracts Human Rights Watch obtained from labor agents and immigration officials, and on the memories of women migrant workers, these contracts usually outlined a two-year work contract.They did not contain a job description detailing the workload or types of work for which the domestic worker would be responsible (see appendix B for a sample contract).It was understood that the worker would bear the cost of travel back to Indonesia if she left before the two-year contract was completed.Many contracts did specify that workers should be able to observe religious practices such as praying five times a day and fasting if that was their wish.Work contracts did not regulate number of hours of work or provide for overtime pay.Although contracts commonly stipulated that a worker could take one day off per week, many also provided that, if the employer paid the worker, she could be made to work all seven days.

Alteration of Travel Documents

There were a lot of young girls, the youngest was fifteen.They changed my age to twenty-six, I was sixteen at the time.

-Interview with Suwari Syaripah, age eighteen, domestic worker, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, February 17, 2004

A significant number of the women whom Human Rights Watch interviewed stated that their passport and other travel documents had been altered to change their age, name, or address.The women and girls who told Human Rights Watch of this practice said they had their passport altered so they would appear to be at least twenty-five.Human Rights Watch interviews included girls and some women who were under eighteen at the time of their recruitment.According to a Malaysian immigration official, Malaysia requires that domestic workers be aged twenty-five to forty-five (see appendix C for a list of requirements to hire a domestic worker).[78]Partly as a result of the widespread practice of altering passports and other travel documents, government authorities and NGOs find it difficult to estimate the number of Indonesian domestic workers in Malaysia that are still children.

In most cases, women and girls did not pay an extra fee for passport alterations, but in a few cases they did pay up to one million rupiah (U.S.$125).Older women also had their passports altered to lower their age.One woman remembered her peers at a labor agency, "There were many, many girls below the age of eighteen, but the company changed their age on their documents.They would have to pay five hundred thousand rupiah."[79]

Discrimination in Hiring Practices

Labor agencies marketed women workers based not only on their skills, but on characteristics unrelated to their job responsibilities in Malaysia.These include their age, weight, height, complexion, marital status, and number of children.Based on these characteristics, Malaysian labor suppliers selected the domestic workers they wanted from the Indonesian labor recruiters.Labor agents often view women domestic workers as tradable goods rather than human beings.One Malaysian labor supplier told Human Rights Watch:

I go to Indonesia every one or two months.I conduct interviews and handpick maids.I have the right to pick whatever product I want.[Some maids end up having to stay in the holding and training centers longer.The reason why is]marketing, some are ugly, fat, short.The final decision belongs to the employer.Maybe they can't sell.Some stay even up to eight months [in the holding and training centers.][80]

Most of the licensed labor agents in Indonesia prepare "biodata" forms for the women workers they have recruited, and both Indonesian and Malaysian labor suppliers noted that agents often select attractive women first, with "less desirable" women more likely to wait in holding and training centers for longer periods of time.Preferences about marital status varied, with some labor agents and employers stating that unmarried workers are better because they have "never been with a man" and are less likely to run away with a boyfriend.Others felt that men would prey upon young, attractive workers and preferred older, married women workers.

Abuses in Training Centers

There were 350 women waiting to work in Singapore, Malaysia, Taiwan.Lots of them were young, mostly Javanese.We received no information about our rights, only about our obligations.They told us we were not allowed outside, we were not allowed to talk to anyone.We were not allowed to go outside, like putting out trash, and we had to clean, iron, and do all the domestic work.We were not allowed to speak to anyone.There was one big room [in the training center] and we all slept there.We would wait for hours and hours in a long line to take a bath, sometimes we had our turns at night.We were not allowed out of the center, there was a big gate with a lock, and two security guards.

I wanted to go home but didn't know how to run away or go home.Many people ran away.Some people paid the company so they could leave.They had to pay five million rupiah (U.S.$610).When [I finally got to go] I felt tired and I didn't want to go to Malaysia anymore.

-Interview with Hartini Sukarman, age twenty-four, returned domestic worker, Lombok, Indonesia, January 26, 2004

As noted above, domestic workers, unlike individuals migrating for other types of work, must complete a training course before the Indonesian government will grant them permission to work overseas.The duration of these "training programs" typically range from one to six months.Labor suppliers, domestic workers, and NGOs told Human Rights Watch that some women and girls may wait in training centers for as long as nine months until the paperwork is completed and agents have selected them for employment.According to the women migrant workers and NGO workers interviewed by Human Rights Watch, the training centers are often overcrowded and the quality of the training is low.[81]The staff and security running the training centers generally restrict the women's freedom of movement and bar them from leaving the facilities.Some interviewees also reported inadequate food and water, verbal and physical abuse, or "training" apprenticeships where they were forced to perform domestic work locally without pay.

Forced Confinement

There were almost seven hundred people [in the training center].Some of them became crazy.They were all women.Some people were waiting there for six months.Most of them wanted to leave the company, but would have to pay one million rupiah [U.S.$122] to do so.A lot of people ran away by climbing the walls.We were not allowed outside.There were many security [guards]-strict-and locked gates.There were two women security and two men.It was very hard to leave the center without a reason.My friend wanted to visit me but wasn't allowed.I felt sorry when I first reached the center, but I pushed through because of my desire to earn money.The security would always check when we were going to sleep to make sure we didn't run away.The security would get punished when people ran away, they would call agents in Lombok to see if the runaways returned home.

-Interview with Jumilah Ratnasari, age thirty-two, returned domestic worker, Lombok, Indonesia, January 26, 2004

Labor agents restricted the movement of prospective women migrant workers while they completed their training in Indonesia or waited for an employment assignment.Only three of the women interviewed by Human Rights Watch reported that they were able to move freely; the rest reported locked gates and constant monitoring by security guards.In a few cases, women were allowed visits by their family, occasional phone calls, or brief, supervised trips to markets, but in many cases, they remained confined to the training facilities for the entire duration of their stay.Most women endured these conditions because of the pressure they felt to migrate to Malaysia and earn money for their families or to repay loans.One woman told Human Rights Watch, "We were not allowed to go outside even if we wanted to buy food.The gate was locked.I wanted to return to Lombok, but I remembered I had borrowed so much money that I had to pay back."[82]

Human Rights Watch interviewed labor agents who cited fears about women getting pregnant, raped, or lost if they were allowed to leave the training center freely.One woman said that the agents warned them they could not go out because, "we could be cheated by others who would then sell us."[83]Another reason is profit.Supplying domestic workers is a competitive industry, with different companies vying to have a ready supply of fresh recruits available to meet labor demand in Malaysia.Because domestic workers typically do not pay any money up front but rather have the first four or five months of their salary withheld, Indonesian labor agencies do not get paid for recruiting a worker until she is selected for employment by a Malaysian labor agency.Because the Indonesian agency has paid for the woman's transportation to the center, her board and lodging, the processing of her documents, and her medical exam, they fear the loss of their investment should she try to run away before she is transferred to a Malaysian labor supplier. This gives them a powerful financial incentive to strictly regulate her movements.

Some domestic workers and NGO activists reported to Human Rights Watch that labor agents kept girls in training or holding centers until they turned eighteen.The staff of KOPBUMI, a network of migrant rights' NGOs said, "The labor agents should [instead] ask migrant workers to wait at home.If they want to leave, they have to pay.They may escape but the shelter people try to catch them."[84]

Inadequate Living Conditions, Food, and Water

I slept on the floor without a mat and used my bag as a pillow.There were 300 people there, all women.We were staying in a big room with no windows.There were three toilets but two were out of order.The water was not enough and the toilets were dirty.I took a bath twice a week, there were so many people that there were long lines.We were not allowed to go outside, there was a gate with a lock.Many people wanted to run away but didn't know how.Some of the women had anxiety and were crazy, because it was very scary.

-Interview with Nur Hasana Firmansyah, age twenty-one, returned domestic worker, Lombok, Indonesia, January 26, 2004

Human Rights Watch found that training centers were typically overcrowded.[85]Women generally slept on the floor and some complained of having no sheets or mattresses.In some cases they had adequate food and water; in other situations, they remained hungry.Sanitation conditions were often poor, with insufficient toilets and showers for the numbers of women.Kusmirah Parinem, a twenty-one-year-old domestic worker in Malaysia, recalled:

I was in the training center for four months.There were 600 people, sleeping in lines on sheets in a big hall.Sometimes you got sheets and sometimes you didn't.We got small amounts of food three times a day.I was hungry.There was one place to bathe and eight or ten women had to go at once.You have to queue up, if you are late, there is not enough water.Drinking water was not enough.If we made some small mistake, the agents punished us and they didn't give us food the whole day, or we had to stay in front of the class all day.The food was not enough and it was not good.[86]

Although the Indonesian Ministry of Manpower and Transmigration has developed minimum standards for space, food, and sanitation, the monitoring of conditions by the ministry is infrequent, and according to NGOs, lax.An official from the Ministry who occasionally checks these conditions, said, "When I go to monitor training centers, I look at the accommodations and the management, for example, do they keep data and records about the workers?"[87]This official was unwilling to divulge the number of training centers that she had visited.

Psychological, Physical, and Sexual Abuse

If we made a mistake, they would get angry with us.Once I had to take [a heavy load of] water on my head and stand on my knees in the sun for two hours because I didn't want to exercise in the morning.I didn't have any other problems, but others did.The staff would beat them with sticks and books.

-Interview with Ira Novianti, age twenty, returned domestic worker, Lombok, Indonesia, January 25, 2004

Human Rights Watch interviewed twelve current and former domestic workers who had experienced psychological and physical abuse at the hands of labor agents and security personnel at training centers in Indonesia.In these cases, labor agents and trainers verbally abused or insulted women if they made mistakes during the training.Physical violence, typically involving beatings with sticks, was used as a tool for discipline and punishment.One domestic worker remembered, "The agency would use angry words, bad words, they beat me.They beat me with a tree branch."[88]

A few women Human Rights Watch interviewed were sexually harassed by the staff at the training centers, and others reported that women at times exchanged sexual favors for expedited processing and placement in Malaysia.Nur Hasana Firmansyah, a returned domestic worker in Indonesia, told Human Rights Watch:

The guards would always pull us and touch us.If they saw a beautiful girl, they took her upstairs and slept with her.I know of two girls, Ratna and Ani, also Jianjur, she was about seventeen or eighteen.The security would tease me, "would you become my girlfriend?" I always fought back.They never touched me because I always screamed for the leader of the girls.I would wake up at night and yell.They would tease us when we went to the washroom.[89]

Exploitative Labor Practices

They tutored us how to work for a week [in the training center].Then I worked in a house for a month.There were about one hundred women at the training centerbut many working outside the agent's house.They would sleep at their employers' house and get paid 150,000 rupiah [U.S.$18.29] per month.I was working when in Medan.

─Interview with Ani Rukmonto, age twenty-two, Indonesian domestic worker, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, February 26, 2004

Some Indonesian labor agencies send women to work as maids in local households, either as "training" or as a way for them to earn money while they were waiting for their placement in Malaysia.Some migrant domestic workers told Human Rights Watch they were able to keep their earnings from this work, while others reported that their entire salaries were retained by their labor agent.

Women employed as domestic workers in Indonesia confront many of the same spectrum of abuses as domestic workers in Malaysia:long hours, no rest days, low or unpaid wages, restrictions of movement, and mistreatment by the employer.For example, thirty-year-old Amsia Widodo told Human Rights Watch that, while at the training center, "People would borrow us to work in their home.I earned 125,000 rupiah [U.S.$15.24] a month.I lived in the [employer's] house and worked from to ironing and washing clothes."[90]

IV. Workplace Abuses in Malaysia

I worked for a husband, wife, two girls and a boy.Sometimes I didn't sleep.I washed clothes, prepared food for the children, and prepared them for school, one by one.I would prepare milk for the youngest and prepare food for cooking.I would vacuum, mop, clean the kitchen, and water the flowers.Sometimes the employer was not satisfied and would ask me to redo it over and over again.My time was wasted by doing the work over and over again.I helped to cook all the meals, and I cleaned the toilets.I was working day and night.I am not sure when I finished, because she would ask me to redo the jobs many times.Sometimes the employer said, "If you can't finish, you can't sleep."I never got any rest or any days off.

I never went out of the house on my own.I went to the market once in my time here [in Malaysia].I couldn't talk to the neighbors.My employers told me, "You can't speak to the neighbors because the neighbors are cheaters."I could not use the phone or write letters.

I was under pressure.I always stayed inside the house and I was upset because I couldn't send a letter to my family.My employers didn't allow me to fast or to pray.Last Ramadan, when I wanted to fast, the employer hit me and said, "If you want to fast, I will not give you any food [at night]." If I didn't finish the work, the employer would be angry with me.Because I had to finish all the work in a hurry, I didn't eat.

Sometimes I slept on the kitchen floor, sometimes in front of the television.I did not have my own room.Sometimes I just fell asleep on the kitchen floor, otherwise the carpet in front of the TV.There was a mattress there.

─Interview with Ani Rukmonto, age twenty-two, domestic worker, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, February 26, 2004

Indonesian migrant domestic workers in Malaysia encounter a wide range of human rights abuses in the workplace, including extremely long hours of work without overtime pay; no rest days; incomplete and irregular payment of wages; psychological, physical, and sexual abuse; poor living conditions; restrictions on their freedom of movement and ability to practice their religion; and in some cases, trafficking into situations of forced labor.[91]Conditions of confinement, workers' lack of information about or access to institutions that could provide assistance, and employers' government-sanctioned practices of confiscating workers' passports present formidable challenges that often prevent women domestic workers from reporting abuses, obtaining help, or even escaping. The lack of monitoring by any independent or government agency compounds these abuses by creating an environment where employers and labor agents face little or no accountability for their treatment of women migrant domestic workers.

Many abuses likely go unreported, but NGOs and the Indonesian Ministry of Manpower and Transmigration estimate that roughly eighteen thousand to twenty-five thousand migrants return to Indonesia each year from Malaysia and other destination countries having experienced some form of abuse.[92]These estimates mostly derive from returning migrants who pass through the international airport in Jakarta, leaving the true numbers of abuse cases unknown.A leader from a consortium of migrants' rights NGOs in Jakarta commented, "Four to eight hundred migrants arrive each day [at the airport].Sometimes there are twelve rape victims in one week, like in November 2003.In 2002, 12 percent of returning migrants reported problems, and 2 percent were ill."[93]

Several other groups have documented abuses against Indonesian migrant workers.Perkumpulan Panca Karsa (PPK), an NGO on the island of Lombok, comes into contact with both documented and undocumented returning migrants, who may have returned by boat or by plane.PPK handled 450 cases of abuse and labor rights violations in 2003.[94]Human Rights Watch interviewed a Malaysian labor supplier who said, "I bring about fifty maids to Malaysia each month, and [of those,] there are usually one or two [who have abusive employers]."[95]In 2003, 753 Indonesian migrant workers ran away from their employers and took shelter at the Indonesian embassy in Kuala Lumpur.The numbers who seek refuge at the Indonesian embassy have increased each year and the majority of those seeking assistance are women.[96]

Hours of Work, Rest Days, and Workload

I would wake up at and go to sleep at , sometimes or 2:00 a.m.Every day was full of work, every week was like that, there was no day off.There was no time to rest.

─Interview with Tita Sari, age twenty-four, domestic worker, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, February 26, 2004

Indonesian domestic workers employed in Malaysia typically work sixteen to eighteen hour days, seven days a week, without any holidays.Most have no significant time to rest during the day, although some are able to take one-hour breaks in the afternoon.Indonesian domestic workers who cared for children in addition to their cleaning responsibilities reported being "on call" around the clock, as in the case of Susanti, who told Human Rights Watch:

It was all work.I cleaned the toilet, all the rooms, the walls.I cleaned the whole house.I took care of the children, one was three years old and the baby was eight months.I worked from to .Sometimes my employer asked me to wake up at to feed the baby.I worked every day.I had no rest during the day.[97]

A domestic worker's typical workload included cooking three meals a day; cleaning the house, including mopping, vacuuming, cleaning windows, and dusting; taking care of children, including bathing them, tutoring them, feeding them, preparing them for school, playing with them, and putting them to sleep; washing the car every day; washing the entire household's clothes by hand; and ironing.Amsia Widodo told Human Rights Watch:

There were three families living together in one big house and I was the only maid.There were seventeen people.There were eleven children between the ages of six and fifteen.I had to take care of the children, prepare them for school, give them baths, and make meals.I cut flowers, did a lot of work in the garden, washed the car, washed the floor, ironed, and cooked.I worked from to I had no rest.There was no day off, even when I asked for it.[98]

As noted above, most labor contracts Human Rights Watch obtained or those described to us by labor agents and Malaysian government officials allow domestic workers to have one day off per week, but this could be bypassed if they were paid for all seven days.With only a few exceptions, the domestic workers Human Rights Watch interviewed had fixed monthly salaries and worked every single day without rest.These workers typically did not receive their full salary; none reported receiving any extra payment for working every day of the week.

The contracts Human Rights Watch obtained failed to stipulate the number of hours that domestic workers should work each day.There is no provision for overtime pay or for vacation days in these contracts or for domestic workers under Malaysian employment laws.The employers and labor agents whom we interviewed defended these policies, often claiming that domestic workers did not know how to rest, and they could not be given a day off because they would get pregnant or bring foreign men to the house.One labor agent explained to Human Rights Watch that if he received a complaint about excessive workload, he would simply explain to the employer that pushing the worker beyond eighteen hours per day would lead her to leave, harming the employer's self interest:

We instruct the employers.We tell them if the maid is not getting enough food or sleep or has too heavy a workload.There should be at least a minimum of six hours of rest for the maid.Otherwise the maid will run away and then the employers have to get a replacement.They will also feel the pinch.[99]

Forced Confinement and Restricted Communication