Colombia: Displaced and Discarded

The Plight of Internally Displaced Persons

in Bogot and Cartagena

Glossary

Agencia Presidencial para laPresidential Agency for Social Action

Accin Social y la Cooperacinand International Cooperation, the

Internacionalagency that administers social programs, including the Social Solidarity Network's program for displaced persons

autodefensasParamilitaries

Autodefensas Unidas de ColombiaUnited Self-Defense Groups of

(AUC)Colombia

CODHESConsultora para los Derechos Humanos y el Desplazamiento, Consultancy for Human Rights and the Displaced

ELNEjrcito de Liberacin Nacional, National Liberation Army

FARCFuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia, Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia:Colombia's largest insurgency.

"Gota a gota""Drop by drop" displacement; that is, the displacement of one or two families at a time rather than that of entire communities.

Mass displacement (desplazamiento masivo)In Colombia, the displacement of ten families or more

paracosParamilitaries

personera, personeroMunicipal officials charged with receiving complaints from citizens of abuses of rights.

Red de Solidaridad SocialSocial Solidarity Network, the government agency that coordinates humanitarian relief for displaced persons.The Social Solidarity Network is a branch of the Presidential Agency for Social Action and International Cooperation (Agencia Presidencial para la Accin Social y la Cooperacin Internacional).

SISBENSocial Program Beneficiary Identification System (Sistema de Identificacin de Beneficiarios de los Programas Sociales), a classification system for health care benefits

Sistema nico de RegistroUniform Registration System

vacunaAn illegal levy that guerrilla or paramilitary groups often require individuals to pay for their protection or in support of the war effort.

I.Summary

"The autodefensas arrived at 5 a.m.," M.D. told Human Rights Watch, explaining why she and her family fled their homes in Putumayo in 1999.(Autodefensas are members of paramilitary groups.)"They called all of us into a room.There was an elderly man, eighty years old-they killed him.They cut off his head and began to play football with it. . . .They killed five of us in all, including the one whose head they cut off.Another man, they cut his arm off at the shoulder."The paramilitaries took the oldest of her seven children, a thirteen-year-old boy.The rest of the family fled to Bogot.

Her husband, L.D., interrupted her account to say, "We've been here one month.It's the second time that we've been displaced."He told our researcher that the Social Solidarity Network (Red de Solidaridad Social), the government agency to coordinate humanitarian relief for the enormous number of Colombians who have been driven from their homes during the conflict, helped them relocate to the department of Nario, to the west of Putumayo along the border with Ecuador.At the end of 2003, the autodefensas forced them to flee again, he said.They received help from strangers after they fled, spending one night sleeping in coffins at a funeral home and another night at a hotel after somebody gave them money for a room."We found our way here," L.D. said.They had just begun to register with the Social Solidarity Network, a process that by law can take up to fifteen business days to complete.Asked what the Social Solidarity Network had given them to meet their immediate needs during this time, L.D. replied, "Nothing.Nothing."[1]

Human Rights Watch interviewed the couple in a makeshift shelter in a shantytown on the fringes of Bogot.Established by a group of individuals who had themselves been forced to flee their homes because of the conflict, the three-story house had no running water and no mattresses or blankets for the new arrivals referred there by the Social Solidarity Network.The couple and their children slept on the floor.

After Sudan, Colombia has the world's largest internal displacement crisis.In the last three years alone, nearly 5 percent of Colombia's 43 million people has been forcibly displaced in much the way that this family was-uprooted from their homes and deprived of their livelihoods because of the country's armed conflict.It is likely that more than half of all displaced persons are children under the age of eighteen.

Officials in the government of President lvaro Uribe Vlez frequently describe displaced persons as economic migrants.This attitude ignores the reality that many have fled after receiving specific threats or because family members or neighbors were killed by guerrillas or members of paramilitary groups.

Indeed, government officials have suggested that programs to address the needs of displaced persons discriminate against other poor Colombians by, they say, arbitrarily singling out one group of impoverished people for assistance.In fact, displaced families are worse off by any measure-quality of housing, access to sanitation, level of education, and access to employment-than other poor families that have not been displaced, the government Social Solidarity Network found.They face the enormous challenge of finding new homes and employment at the same time that they are struggling to cope with the events that caused them to flee their communities.

Reflecting the mistaken view that most displaced persons have chosen to relocate for economic reasons rather than because of the armed conflict, President Uribe's government has promoted return to home communities as the principal response to internal displacement.Displaced persons, nongovernmental observers, and officials with many international agencies have been sharply critical of this approach, noting that lack of security in many areas often prevents safe return.

In this report, Human Rights Watch examines the hurdles internally displaced persons face in two cities, Bogot and Cartagena, in access to humanitarian assistance, education, and health care.Internal displacement is a complex phenomenon, one that this report does not attempt to address comprehensively.Instead, this report examines the immediate needs of displaced families once they arrive in their new communities.

Displaced families often confront urgent challenges in providing for their basic necessities once they arrive in their new communities.In a typical account, E.B., an adult man living in the Nelson Mandela barrio on the outskirts of Cartagena, identified immediate humanitarian assistance, shelter, health services, and education as the principal needs he and his displaced neighbors faced.[2]

Colombia is one of a handful of countries that have enacted legislation to protect the internally displaced.Under its Law 387, displaced families are entitled to humanitarian assistance, for example.But the registration process for these benefits can be confusing and cumbersome, despite efforts by the Social Solidarity Network to streamline the process.The office of the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees found in December 2004 that only half of the families registered over a two-year period actually received humanitarian assistance.For those that do, assistance is limited in most cases to three months.

Displaced children are entitled to attend schools in their new communities, but in practice they face significant hurdles in continuing their education.Some children are turned away because they are asked to produce school records or forms of identification they no longer possess.Others are denied enrollment because schools have no room for them.In many cases, the matriculation fees and related costs of schooling prevent them from attending.

Displaced families have particular health needs, and under Colombian law they should receive free basic health care.Even so, many displaced families are not covered by Colombia's subsidized public health system, not because they do not qualify for coverage but simply because the system is at full capacity.They should be able to receive emergency care, but they are often turned away when they seek medical attention because hospitals have no incentive to provide services for which they will never receive payment.Those who are enrolled in the subsidized health care system must still pay for medications, which may be beyond the reach of the incomes of displaced families.

Because internally displaced persons have not crossed an international border, they are not refugees as that term is used in international law, and the international protections offered to refugees do not apply to them.Their situation as internally displaced persons is addressed in a separate, nonbinding set of international standards, contained in the Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement.

The Guiding Principles call on states to safeguard the liberty and personal security of displaced persons, guarantee them treatment equal to that given to those who are not displaced, ensure free primary education for their children, and offer them necessary humanitarian assistance, among other safeguards.The state should promote the return of displaced persons to their home communities only when such returns are voluntary and can be accomplished in safety and with dignity.

On paper, Colombia's Law 387 guarantees many of these safeguards."In Colombia, the laws are very advanced," said Marta Skretteberg, then the head of the Colombian office of the Norwegian Refugee Council."It has one of the most modern laws with regard to internal displacement.In reality, it's not implemented."[3]As one European official commented, one of the law's chief weaknesses is its failure to give clear responsibility to a single government agency, with the result that "nobody was responsible for the problem."[4]In early 2004, the system of attention for the displaced population had reached such a state of crisis that the Colombian Constitutional Court declared that it was in a "state of unconstitutional affairs" and ordered the state to take corrective measures within one year.

As the office of the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees notes, the government has undertaken some important initiatives to safeguard the well-being of persons who are forcibly displaced.The state has established an early warning system, for example, and has improved its capacity to provide emergency humanitarian assistance to those in immediate need.In response to the Constitutional Court's 2004 decision, the government announced in August 2004 that it would increase the number of places available to displaced students in the country's public schools and would also increase the national health system's coverage of displaced persons.In February 2005 the government adopted a new National Plan of Attention to the Displaced Population (Plan Nacional para la Atencin Integral a la Poblacin Desplazada).The government has substantially increased the budget for its programs for displaced persons.

Despite these measures, the failure of local officials to act on information gathered by the early warning system has undermined its effectiveness.As this report documents, many displaced youths have not benefited from the education and public health initiatives.Indeed, the Constitutional Court concluded in September 2005 that the measures taken by the government to comply with its 2004 decision were insufficient both in terms of resources and institutional will.

Implementing the provisions of Law 387 to provide all internally displaced families with humanitarian aid and access to education and health services would be costly.The various Colombian government agencies responsible for implementing the law spent over 436,500 million pesos, about U.S.$175 million, between 2000 and 2003, and the government has allocated 474,000 million pesos (some U.S.$191 million) for 2005.Even so, the General Comptroller of the Republic (Contralora General de la Repblica) found that actual expenditures for the years 2001 and 2002 were 32 percent less than the funds allocated for assistance to internally displaced persons.If the same is true for the years going forward, these agencies have additional resources that they can draw upon to comply with the Constitutional Court's 2004 decision and address the urgent needs of Colombia's displaced population.

The United States is the most influential foreign actor in Colombia. In 2004 it provided more than U.S.$700 million to the government, mostly in military aid. Although 25 percent of the security assistance included in this package is formally subject to human rights conditions, the conditions have not been enforced.In August 2005, for example, U.S. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice "determined that there is sufficient progress to certify to Congress that the Colombian Government and Armed Forces are meeting statutory criteria related to human rights and severing ties to paramilitary groups."[5]Such certifications have meant that the full amount of aid continues to flow to Colombia even though the government has failed to break ties between the military and abusive paramilitary groups.

Although most U.S. assistance is in the form of military aid, the Internally Displaced Persons Program of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) will provide some U.S.$33 million in FY 2005 and is expected to continue to provide support at least through 2010.In October 2005, USAID entered into an agreement with the International Organization for Migration (IOM) and the Pan American Development Foundation (PADF) under which USAID will provide U.S.$100 million over the next five years to fund a joint IOM/PADF project to provide assistance to internally displaced persons and other vulnerable groups.

The European Union has pledged over 330 million (U.S.$410 million) in aid to Colombia in a package that ends in 2006. Unlike U.S. funding, which mainly goes to Colombia's armed forces, nearly all of the European aid goes to civil society and to the United Nations office in Colombia.In addition to their support through the European Union's programs, several E.U. member states, including the Netherlands, Spain, and the United Kingdom, provide significant bilateral assistance.Canada and Japan also provide bilateral assistance to Colombia.

***

Human Rights Watch conducted research for this report in and around Bogot and Cartagena in July and August 2004, with a follow-up visit to Bogot in September 2005.During our field investigation, we interviewed over seventy adults and children who had been forcibly displaced from their homes because of the conflict.(The names of all children and many of the adults who were forcibly displaced have been changed or withheld to protect their privacy.)We also conducted over fifty other interviews for this report, speaking to teachers, health care providers, activists, academics, lawyers, and government officials.

We assess the treatment of displaced persons according to the standards set forth in the U.N. Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement and that of children according to international law, as set forth in the Convention on the Rights of the Child and other human rights instruments.[6]In this report, the word "child" refers to anyone under the age of eighteen.[7]

II. Recommendations

Humanitarian Assistance

The Social Solidarity Network should ensure that displaced families receive emergency humanitarian aid without delay to provide for their immediate needs while they are completing the formal process of registering as displaced persons.

Education

The Ministry of Education should ensure that all children enjoy their right to a free primary education, as guaranteed by international law.In particular, it should work with appropriate enforcement officials to sanction schools that illegally levy matriculation fees, "voluntary" monthly assessments, or other fees, as well as those that turn away students who do not have identification, who lack uniforms, or who are older than the target age for their grades.It should also work with the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees, and donor governments to identify ways to prevent indirect costs of schooling, such as the cost of school supplies and transport, from becoming a barrier to the enjoyment of the right to education, particularly for children who are internally displaced.

Health Needs

The Ministry of Health should ensure that hospitals and clinics are aware of their obligation to provide all persons with emergency care.It should establish a referral and complaint mechanism to assist people in locating health facilities and in registering complaints, if necessary.It should work with appropriate enforcement officials to sanction facilities that turn away people from the emergency care to which they are entitled as a matter of law.

Colombian authorities should take the following additional steps to ensure the right to the highest attainable standard of health:

- The government should extend the coverage of the subsidized health system to include medication, specialized consultations, and operations for persons who are internally displaced.

- The government should extend the period of humanitarian food aid beyond the usual three- or six-month period authorized by Law 387.

- Public health initiatives should include improved access to health information, including information on sexual and reproductive health.

- Public health initiatives should also include public awareness campaigns to inform displaced persons of the health care available to them and where they can go to receive the documentation necessary to receive it.

International donors should extend funding for health initiatives for displaced persons.

Returns to Home Communities

The government of Colombia should ensure that any returns of displaced persons to their home communities are voluntary and in conditions of safety and dignity.

Donor governments should stop funding government programs that encourage returns that are not voluntary and in conditions of safety and dignity, as required by international standards.In particular, the U.S. Agency for International Development's Internally Displaced Persons Program and the projects it funds should not support government initiatives that do not comply with international standards relating to returns.

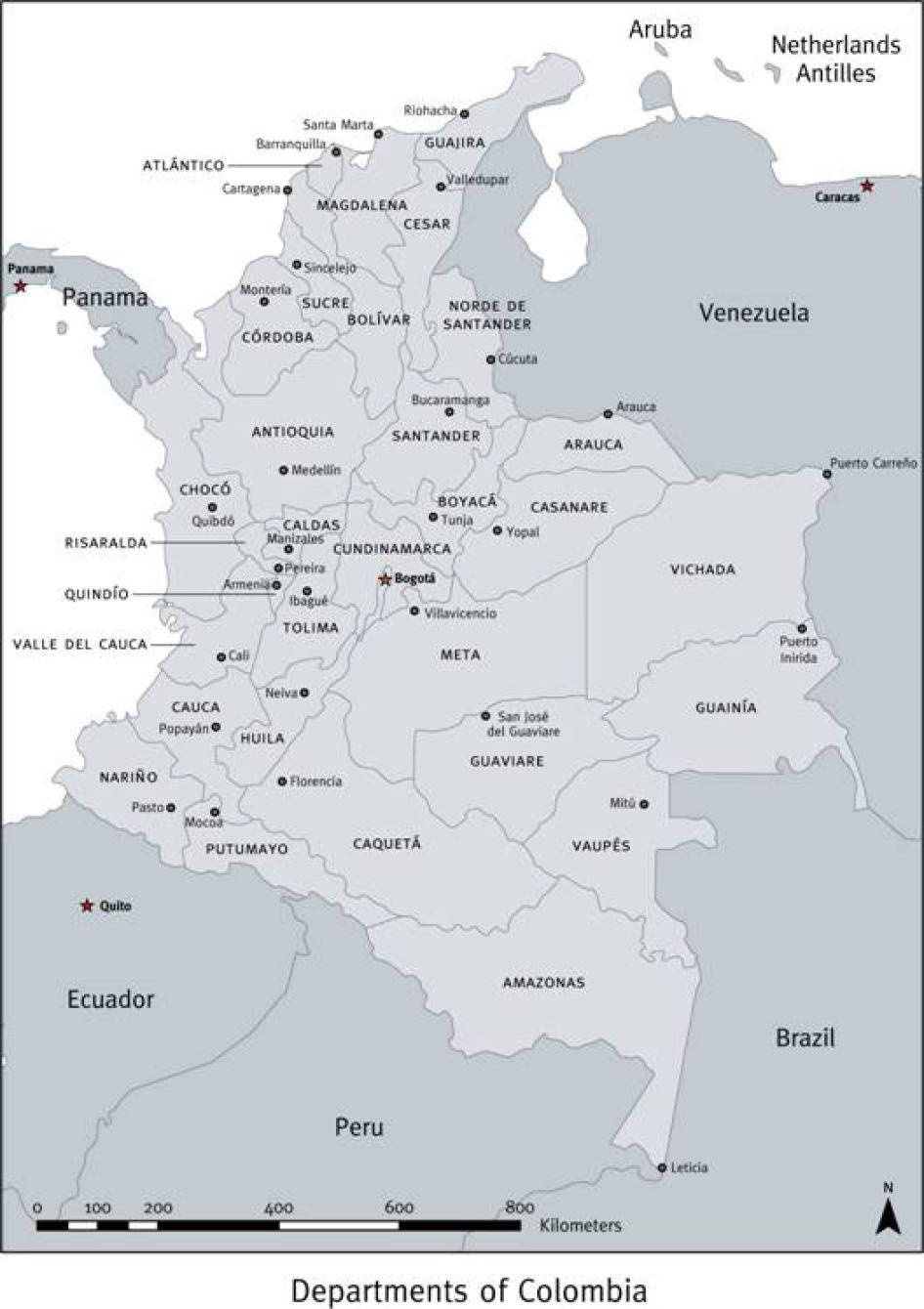

III. Internal Displacement In Colombia

Over 150,000 persons were forcibly displaced from their homes in the first six months of 2005, a 17 percent increase from the same period in 2004, the nongovernmental Consultancy on Human Rights and Displacement (Consultora para los Derechos Humanos y el Desplazamiento, CODHES) reports.[8]Since 2002, when displacement hit a five-year peak, at least 3 million people have been forced out of their homes and communities.That is, over 5 percent of Colombia's total population of 43 million has been forcibly displaced in the last three years alone."Colombia is therefore by far the biggest humanitarian catastrophe in the Western Hemisphere," U.N. humanitarian coordinator Jan Egeland said at a press conference in May 2004.[9]Worldwide, only Sudan has more displaced persons, according to data collected by the Global IDP Project.[10]

Forced displacement is a consequence of Colombia's armed conflict-often a response to fear generated by indiscriminate attacks by all parties to the conflict but in many cases to massacres, selective killings, torture, and specific threats.As Francis Deng, the U.N. secretary-general's representative on internally displaced persons, observed in 2000, "[D]isplacement in Colombia is not merely incidental to the armed conflict but is also a deliberate strategy of war."[11]In a 1999 report on Colombia, written well before the recent peak in 2002, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights observed, "The phenomenon of internal displacement has reached such proportions in Colombia in recent years that [the commission] considers it to be one of the gravest aspects of that country's overall human rights situation."[12]Nevertheless, government officials often discount the scope of displacement and suggest that many families have chosen to relocate for economic reasons rather than because of the armed conflict.

A key component of President lvaro Uribe Vlez's response to internal displacement has been to promote return to home communities.Displaced persons, nongovernmental organizations, and officials with many international agencies have roundly criticized the government's return policy, saying that lack of security prevented safe return."There's not a sign of any one of the three necessary conditions for return.There's no security, no dignity, and very often no voluntariness," Jorge Valls, an official with the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), told us in August 2004.[13]Returns that are not voluntary and in conditions of safety and dignity do not comply with international standards.

The Conflict in Colombia

Colombia has seen conflict of one kind or another for over 150 years, beginning with struggles between the Conservative and Liberal parties in the nineteenth century-"scuffle[s]" that "provok[ed] thirteen coups and uprisings" between 1849 and 1900, as Robin Kirk notes[14]-and escalating into a fourteen-year period from 1948 to 1964 known as "La Violencia."[15]Every bit as violent as its name suggests, "La Violencia" appears in retrospect as little more than the opening act for twenty-five years of military rule under a state of emergency, four decades of organized armed rebellion that official repression helped foster, and the horrific abuses by all sides that continue to this day.

Since its formation in the mid-1960s, Colombia's largest guerrilla insurgency, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia-Ejrcito del Pueblo, FARC-EP), has been responsible for the killing and abduction of civilians, hostage-taking, disappearances, the use of child soldiers, grossly unfair trials, the cruel and inhuman treatment of captured combatants, and the forced displacement of civilians. Further, FARC-EP forces have continued to use prohibited weapons, including land mines and gas cylinder bombs that wreak havoc and cause appalling fatalities and injuries, and to attack medical workers and facilities in flagrant disregard of international legal norms.[16]

The other major guerrilla insurgency, the National Liberation Army (Ejrcito de Liberacin Nacional, ELN), is little better.The International Crisis Group notes that "the ELN is responsible for a large proportion of about 4,000 kidnappings committed every year in Colombia."[17]

Colombia's right-wing paramilitary groups, in turn, trace their origins to small "self-defense groups" formed by local landowners and businessmen to defend themselves and their property against guerrilla violence, and to death squads created by drug cartels in the 1970s and 1980s. Operating with the tolerance of, and often in collusion with Colombian military units, paramilitary groups have a long history of a litany of abuses against civilians, including massacres, assassinations, torture, forced displacement, forced disappearances, and kidnappings.[18]

A casual observer might easily confuse the various illegal armed groups, which long ago abandoned most of their ideological underpinnings.Both guerrilla and paramilitary groups pay for war with profits from illegal activities, among them kidnapping, contraband, and the international trade in weapons and narcotics.[19]Although Colombia's paramilitary groups declared a unilateral cease-fire in 2002, in practice both guerrillas and paramilitary groups continue to commit massacres, assassinations, acts of torture, and other grave breaches of international humanitarian law.[20]One out of every four irregular combatants in Colombia is under the age of eighteen, Human Rights Watch found in 2003; and guerrilla and paramilitary groups, in particular the FARC-EP, continue to recruit and use child soldiers.[21]

Beginning in late 2002, while pursuing a military offensive against guerrilla groups, the government negotiated for the demobilization of paramilitary groups.The negotiations were accompanied by ceremonies in which thousands of purported paramilitaries have turned in weapons to the government.At the same time, however, paramilitaries flouted their Organization of American States (O.A.S.)-monitored demobilization negotiations while consolidating their control over vast areas of the country.In addition, the demobilization process lacked an adequate legal framework to ensure the dismantling of complex and economically powerful paramilitary structures or to provide for the effective investigation and prosecution of paramilitaries implicated in the commission of atrocities.[22]There was no progress in 2004 in peace negotiations between the government and guerrillas.[23]In June 2005, over the objections of local and international nongovernmental organizations and the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, the Colombian Congress enacted controversial legislation that granted a virtual amnesty to members of paramilitary groups.[24]

Forced Displacement as a Consequence of the Conflict

In August 2004, when we asked Angela Borges, then the director of the government office responsible for coordinating humanitarian assistance for displaced persons in the Bogot suburb of Soacha for the most common reasons why displaced persons come to that municipality, she replied, "First, because they have received threats.Second, because of fear of violence."[25]Reports collected by the U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) from local ombudman'soffices, the Consultancy for Human Rights and the Displaced (Consultora para los Derechos Humanos y el Desplazamiento, CODHES) and other groups suggest both that the same is true for displacement throughout the country and that 2005 was no different from 2004 in this respect.[26]

Many of those we interviewed said that they left after they or family members received specific threats.For example, ten-year-old Jos F. fled Tolima with his family in 2002 because his cousin's army service left them open to the charge that they were collaborators."They threatened us," Jos said, without specifying the group."They said that if we didn't leave, they would kill us.They gave us half an hour to leave."[27]Later the same day, we interviewed a relative of his, Marina F.She explained, "My [older] brother is in the army, so the groups didn't like that.They told my dad that we had to leave.If we didn't, they would kill my brother."[28]In all, fourteen members of their extended family fled their Tolima village for Bogot.

We heard from others that they had also been accused of "collaboration," although the details differed.A.B., a man from Caldes, explained that in his case:

I had to pay a vacuna [a levy or bribe] to the paracos [paramilitaries].Then the guerrillas came and saw that I had paid the vacuna, so they came to kill me.I had to pay the paramilitaries, and then I was afraid.It was 3,000 pesos [$1.20] that I paid.The problem wasn't the money.It was that they [the guerrillas] thought we were collaborating with the paramilitaries. . . .They told me they would kill me.[29]

Those we interviewed were frequently unable or unwilling to identify the groups that made the threats.L.Z., a woman we interviewed in Cazuc, told us that she and her family came to Bogot in 2001."I came from a farm in the country.My husband and I lived there.He was threatened.There were other deaths," she said."If I didn't go, they would kill me and my husband."Asked who had made the threats, she replied, "They were hooded.I don't know if they were paramilitaries or guerrillas."[30]

Others left out of fear after neighbors or employers were killed.In a typically spare account, a woman in her mid-fifties told us why she and her family fled their home in Tolima in 2001:"A man was killed on the farm and we had to leave.It fell to us to leave."Later in our interview, she explained that the man had been the owner of the farm.The killers wore hoods, she said."There were nine of them, and they also attacked another farm.We thought they would kill us if we stayed."When we spoke with her in July 2004, she was living in Cazuc with her daughter and seven other family members.[31]Still others, such as M.D. and her family, profiled in the summary, told us that they left because they had reason to believe that a family member would be forcibly recruited.[32]

The Scope of Internal Displacement

It is difficult to ascertain with certainty the number of persons who have been forcibly displaced since the 1960s, when Colombia's modern conflict is generally considered to have begun.[33]Even for recent years, estimates of the displaced population vary considerably.In 2002, for example, the year recognized by all authorities as one in which displacement was at its peak, the Social Solidarity Network initially estimated that nearly 270,000 persons were displaced.The nongovernmental organization CODHES estimated that 412,500 persons were displaced during the year, finding that the increase in displacement between July and September of that year was the most significant in seventeen years:

In those three months the number of persons forcibly displaced reached the figure of 149,387 as compared with 90,179 and 113,554 in the first two semesters [of 2002].That is, an average of 1,623 persons each day, 67 persons each hour, one family every ten minutes.[34]

Arriving at such estimates is necessarily prone to error.Even so, CODHES contends that its estimates have been borne out once the Social Solidarity Network has released its data on the number of persons actually registered during the year.For the four years 2000 to 2003, in fact, the number of actual registrations recorded by the Social Solidarity Network was 5 percent higher, on average, than CODHES's estimate.In 2002, for example, the Social Solidarity Network eventually reported that 423,231 persons were enrolled in its Uniform Registration System (Sistema nico de Registro) as displaced persons, over one-and-a-half times its initial estimate of 270,000 and 10,731 persons more than CODHES estimated.[35]

Forced displacement fell in 2003, but when Human Rights Watch interviewed humanitarian workers and displaced persons in mid-2004, they suggested that displacement was on the rise again."Families are arriving daily.Twenty-five families have arrived in the last fifteen days," said O.L., interviewed in Altos de Cazuc in August 2004."But the government is saying that this displacement has ended."[36]A worker with the nongovernmental Association for the Welfare of the Colombian Family (Asociacin Probienestar de la Familia Colombiana, Profamilia) in Cartagena told Human Rights Watch that same month, "In 2002 and 2003, we saw a reduction in the numbers coming to Cartagena," she told Human Rights Watch."In 2004, the numbers are increasing again."[37]

These impressions have proven to be correct.Some 287,500 persons were forcibly displaced in 2004, a 38 percent increase over 2003.[38]The first six months of 2005 were, if anything, worse:On average, 848 persons were displaced every day during this period, as compared with an average of 724 persons per day during the first half of 2004, CODHES reports.[39]With regard to Bogot and Cartagena, local officials and representatives of nongovernmental organizations generally agreed that both metropolitan areas continued to receive displaced families in large numbers in 2004 and 2005.[40]Between April and June 2005, for example, CODHES reports that some 11,000 displaced persons relocated to Bogot and 2,400 to Cartagena.[41]

Estimates of the racial and ethnic composition of displaced persons vary as well.CODHES estimated that 33 percent of those displaced in 2002 were Afro-Colombian; the Social Solidarity Network put the figure at closer to 18 percent.Even the lower of these figures indicates that Afro-Colombians are far more likely than other groups to suffer displacement.Less than 4 percent of the national population is Afro-Colombian, according to the 1993 census.[42]Similarly, some 12 percent of Colombia's displaced population is indigenous, even though indigenous peoples make up less than 2.5 percent of the national population.[43]

The ombudsman's office and other observers suggest that Afro-Colombian and indigenous communities disproportionately suffer forced displacement because their lands are frequently of strategic interest to Colombia's armed groups.[44]"[T]hey are especially vulnerable to being pushed off their land, which is coveted by armed groups for the cultivation of African palm and other lucrative crops, including coca," Erin Mooney, senior advisor to the representative of the U.N. Secretary-General on the human rights of internally displaced persons, observed in June 2005.[45]As one example of forced displacement in Afro-Colombian communities, 1,200 Afro-Colombians fled their homes along the BojayRiver in Choc in February 2005 in response to increased presence of the FARC-EP and paramilitary groups.[46]Similarly, the special rapporteur on the situation of human rights and fundamental freedoms of indigenous people has observed that the activities of armed groups in indigenous regions have increased recently as those groups have increased the cultivation of illicit crops in these areas and as military pressure has forced members of armed groups into these areas.[47]

More than half of all displaced persons are children under the age of eighteen.Of those recorded as displaced by the Social Solidarity Network between 1995 and August 2005 and whose ages are known, 54 percent were under age eighteen.[48]Their data are similar to the findings of an International Organization for Migration (IOM) survey of internal displacement in the departments of Caquet, Nario, Norte de Santander, Putumayo, Santander, and Valle del Cauca conducted in 2001.In that survey, the IOM found that nearly one-quarter of those surveyed were under the age of seven and 55 percent were under the age of eighteen.Children, particularly those under seven, made up a larger proportion of the displaced population in urban areas.[49]A 2003 study of displaced persons in Bogot found that 56 percent of the displaced population was under the age of eighteen, with 31 percent younger than age seven and 25 percent between the ages of eight and seventeen.[50]More recent studies indicate that children may make up an even higher percentage of the total.Sixty-two percent of those surveyed for a March 2005 study by the World Food Programme and the International Committee of the Red Cross were under the age of eighteen.In the province of Norte de Santander, children made up 77 percent of displaced persons included in the survey.[51]

Sixty-three percent of those who are forcibly displaced relocate to Colombia's largest cities, according to the ombudsman's office.[52]Taking into account only those who had registered with the government's Social Solidarity Network as of December 2002, Bogot and Cartagena were the second- and fourth-largest recipients of displaced persons.The Social Solidarity Network reported that some 46,000 displaced persons had registered in Bogot and over 24,000 had registered in Cartagena as of that date.[53]

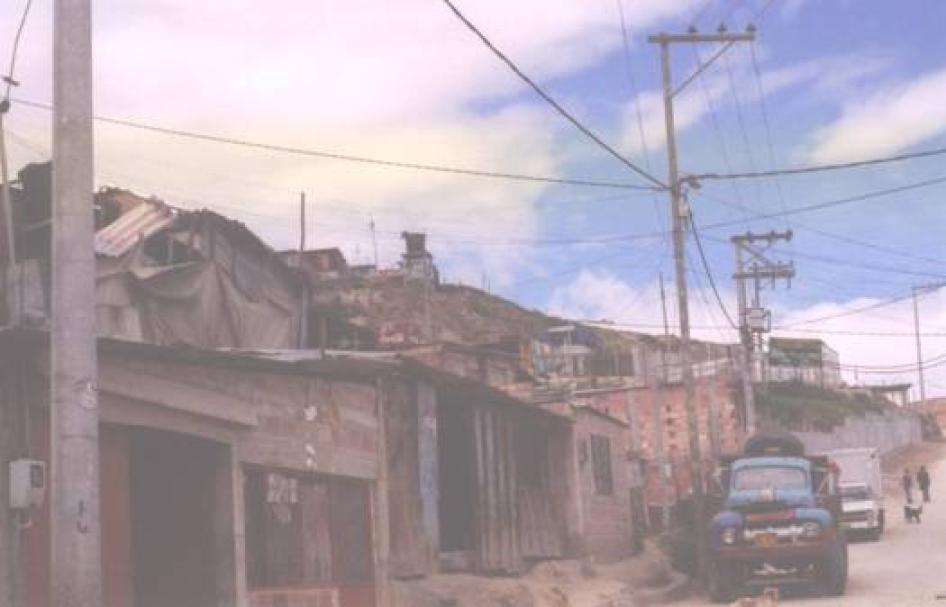

Displaced persons who come to the metropolitan region of Bogot typically end up in the city's poorer neighborhoods, places such as Bosa, Ciudad Bolvar, and Ciudad Kennedy; in and around the neighboring municipality of Soacha, particularly in makeshift housing on the hills known as the Altos de Cazuc; and in rural communities in the capital district, such as Usme.[54]In Cartagena, most displaced families settle in shantytowns in the Nelson Mandela, El Pozn, and Villa Hermosa communities, places that are, in the words of U.N. undersecretary for humanitarian affairs Jan Egeland, "floating in a sea of sewage and garbage."[55](Villa Hermosa is more commonly known as the Barrio Bill Clinton, a name its inhabitants adopted informally after President Clinton's visit to Cartagena in August 2000.)These communities tend to have a high level of violence, the result both of gang activity and the presence of one or more of the paramilitary and guerrilla groups.In Altos de Cazuc and Ciudad Bolvar in particular, local human rights groups report high homicide rates for youths under the age of twenty-five.[56]

Displaced families in El Pozn, on the outskirts of Cartagena, crowd into single-room shacks haphazardly constructed from scraps of lumber, cardboard, plastic sheeting, and corrugated tin.

2004 Michael Bochenek/Human Rights Watch

Living Conditions

Officials in President Uribe's administration frequently describe displaced persons in terms that equate their circumstances with those of impoverished Colombians in general.As a consequence of this view, the government has suggested that programs that address the needs of displaced persons are discriminatory against the rest of the poor, arguing that it is improper to offer more assistance to one group of impoverished people than to others.[57]This attitude ignores the reality that displaced people have lost their homes and their livelihoods.Fleeing violence or threats of violence, they have abandoned their communities and have sought refuge in unfamiliar and often miserable surroundings.Purely in objective terms-quality of housing, access to sanitation, level of education, and access to employment-displaced families are almost always worse off than other poor families who have not been displaced, as a 2002 investigation by the Social Solidarity Network found.[58]Among the study's findings:

- The households of displaced persons tend to be larger, younger, and more crowded than the households of those who have not been displaced.The average displaced household has 4.6 family members, while the typical non-displaced household has 3.6.On average, 40 percent of the occupants of displaced households are under age twelve, as compared with 28 percent in non-displaced households.Sixty-one percent of displaced households live in dwellings without at least one room that is used exclusively as a bedroom, while 60 percent of non-displaced households have at least one bedroom in their homes.[59]

- Fifty percent of displaced households live in dwellings constructed of cloth, cardboard, or scraps of wood.In contrast, only 16 percent of non-displaced households live in such dwellings.[60]

- Twenty-seven percent of displaced households lack bathrooms in their homes, as compared with 12 percent of non-displaced households.In Cartagena, 81 percent of displaced households do not have bathrooms.Only 1 percent of displaced households in Cartagena have a toilet that is connected to a sewer.[61]

In addition, as an official with the Spanish section of Mdecins sans Frontires noted, displaced persons have psychological needs that set them apart from other poor members of the communities in which they now live."There's a difference in the kind of trauma they've gone through," he said.[62]

Displaced families face the enormous challenge of finding new homes and employment at the same time that they are struggling to cope with the events that caused them to flee their communities."It's emotionally difficult for these children.They had to leave their homes on short notice.Most had to be gone by a certain time," a teacher in Cartagena told Human Rights Watch.[63]L.Z., a middle-aged woman living in Cazuc, said, "We spent a lot of days hungry when we first came here.I would go out and start to cry.Seeing the children hungry, that's what wounds the soul. That was very hard.We left the farm, the bull, the cows, the other animals, everything."[64]

Displaced families must frequently live in close quarters in their new surroundings.Thirteen-year-old Yolanda R., who fled Crdoba with her extended family because of violence, told Human Rights Watch that "there are fourteen of us" living in a two-bedroom home on the outskirts of Cartagena.[65]Esmeralda Rodrguez, a teacher and lawyer working in Cazuc, reported that many displaced families had a hard time adjusting to the conditions in the neighborhood where she worked."There's no running water here," she said."Many of the people who are displaced are campesinos who had their own land.Here, they live in a marginalized situation where there is a lack of public services-health, education, shelter."[66]

Unemployment is high among displaced persons, and many of those we interviewed complained that they were unable to find a job."I worked in construction," A.B. said of his life in Caldes before he fled to Bogot."They don't give me work wherever I go."[67]The lack of job opportunities is particularly acute among those over the age of fifty."Nobody has given me work because of my age," said A.G., a sixty-five-year-old woman who stirred a large tub of cocado, a popular Colombian sweet made by browning coconut, as she talked with us.She told us that she made and sold the sweet every day to support her large extended family.[68]

One result of the widespread unemployment and underemployment of adults in displaced families is that their children are likely not to finish their schooling."The issue of earnings is related to education," said Camila Moreno, then the head of the Displacement Unit in the ombudsman's office, noting that parents' inability to support their families means that "all members of the family have to contribute" to the household income."Older children have to go to the streets to work, or they must stay at home to care for small children," she said.[69]

Domestic violence is higher among displaced families than in the population as a whole and is another consequence of the stresses that displaced families face.A 2001 Profamilia survey of displaced women found that 52 percent of respondents had suffered some form of physical violence at the hand of a partner.Of those, 44 percent had been pushed at least once, 41 percent had been slapped or punched, 18 percent dragged or kicked, 15 percent hit with a hard object, 14 percent forced to have sex, and 14 percent threatened with a firearm.[70]

Crime is rampant and both guerrilla and paramilitary groups operate openly in the Altos de Cazuc, where many displaced families who come to the Bogot metropolitan area find shelter.

2004 Michael Bochenek/Human Rights Watch

Return to Home Communities

The government of President Uribe, who took office in August 2002, has promoted return to home communities as its principal response to displacement.A document setting forth President Uribe's controversial "democratic security" policy (poltica de seguridad democrtica) notes, for example:

The hundreds of thousands of Colombians who year after year are displaced from their lands and reduced to misery by the terror of illegal armed organizations require the most urgent attention from the State and the solidarity of society.In coordination with local authorities and organizations, the Social Solidarity Network will carry out, with the agreement of displaced families, return plans to facilitate their collective return to their places of origin.The Government, through the actions of the Public [Armed] Forces, will restore conditions of security to the zones and then channel resources by means of microcredit, food security programs, and community escort programs.[71]

The vice-president's 2003 report on human rights and international humanitarian law observes:"On the understanding that returning home is the best alternative, the Government has been working towards helping at least 30,000 families, that is some 150,000 Colombians, to return to their own land."[72]The government announced that some 70,000 internally displaced persons were returned in 2003 and 2004 as the result of this policy.[73]

In particular, beginning in June 2004, the government has offered housing subsidies to displaced families who return to their home communities.These subsidies are not available to families who choose not to return.The office of the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees has criticized this approach, saying, "The measure discriminates against those people who are unwilling to return and runs counter to the principle of voluntariness that should be present in returns . . . ."[74]

Many of the displaced families we spoke with expressed serious doubts that they could return to their home communities safely."It's a lie that things have improved," said L.D., uprooted for a second time after the government helped him and his family to relocate to Nario."Things are worse.They're sending people to their deaths.Return means death. . . .What the government says?It's deceit, a lie, totally false."[75]

Several representatives of nongovernmental organizations knew of similar cases of families displaced for a second time after returning to their home communities."I spoke with a woman from Santa Marta who received a letter in 2000 certifying her status as displaced.She told me, 'I returned to my land, and I was there six months before I left again.'There aren't sufficient guarantees for the people to return. . . .They have to leave again out of fear," reported Patricia Ospina, the coordinator of Profamilia's program for displaced families.[76]

Such accounts are not unusual, other experts told us."In Valle del Cauca, for instance, we have heard of twenty-five cases of return to areas that did not offer conditions of security," said Juan Carlos Monge, an official with the office of the U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights, in an interview in August 2004.The result of such returns, he said, would be renewed displacement.[77]

An early warning system established by the ombudsman's office could help notify returnees and others of risks, but the government has undermined the system's effectiveness.The U.N. Inter-Agency Internal Displacement Division observed after its January 2005 mission:

In 2003, the Government decided that early warnings could no longer be issued directly from the Ombudsman's Office to the pertinent civilian and military authorities but had to go through a bureaucratic process managed by an inter-institutional government committee (CIAT).According to the Ombudsman's Office, this extra layer has drastically diminished the efficiency of the system.Of the 90 proposed early warnings sent to the CIAT in 2004, only 18 were accepted and issued.Some of the Regional Ombudsmen informed the mission that in many cases the system is not used at all because of its perceived lack of effectiveness.[78]

The 2005 national plan calls for the Inter-Institutional Early Warning Committee to strengthen the early warning system.[79]

Despite these serious concerns, the government's policy favoring return has support from the United States, by far Colombia's largest donor government.In interviews with Human Rights Watch, some U.S. officials echoed the official views of the Colombian government, particularly in their tendency to minimize the extent to which displacement is the result of the conflict.Kenneth Weigand of the U.S. Agency for International Development (AID) told our researcher in August 2004, for example, "There's constant migration out of some places into others.It's impossible to know to what degree they are really displaced because of violence."Switching into Spanish, he added, "We strongly support the policy of return."He discounted the possibility that the lack of physical security and lawlessness prevents many from returning to their home communities, saying, "Once they taste the city, they see more opportunities."[80]

In late 2005, however, other AID officials were less categorical."We support returns if there is security, if they are voluntary, and if there is assistance in place for returnees," said Ileana Baca, internal displaced persons project manager in Colombia.[81]

Elsewhere, there is little support for the government's return policy."The return policy is a disaster," Harvey Surez, then the executive director of CODHES, stated bluntly."Returns aren't complying with any of the conditions."[82]Officials with the office of the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR or, in Spanish, ACNUR) and UNICEF used more measured language but were no less critical.A UNHCR report concluded, for example:

UNHCR considers that, in general terms, to date:(1) conditions do not exist to guarantee the effective application of the basic principles of voluntariness, security, and dignity; (2) the rights set forth in internal norms; and (3) the response of the State does not offer real alternatives other than the return of the populace.The return process does not constitute a durable solution because the situations of instability remain.[83]

Referring to the requirement that returns comply with conditions of security, dignity, and voluntariness, Jorge Valls of UNICEF stated, "We support return if it meets these conditions. . . .But conditions in Colombia don't allow for returns" at the time of our interview in August 2004."The conditions just aren't there," he repeated.[84]

Under the Guiding Principles, states have the responsibility "to establish conditions, as well as provide the means, which allow internally displaced persons to return voluntarily, in safety and with dignity, to their homes or places of habitual residence, or to resettle voluntarily in another part of the country."[85]The state should not encourage returns to home communities when they are not voluntary and in conditions of safety and dignity.

Internal Displacement in International and Colombian Law

The Guiding Principles use the term "displaced persons" to refer to those who "have been forced or obligated to flee or to leave their homes or places of habitual residence, in particular as the result of or in order to avoid the effects of an armed conflict, situations of generalized violence, violations of human rights or natural or man-made disasters, and who have not crossed an internationally recognized State border."[86]Colombia's Law 387, adopted in 1997, generally conforms to this definition except that it does not recognize natural or man-made disasters as reasons for displacement:

A displaced person is any person who has been forced to migrate within the national territory, abandoning his place of residence or habitual economic activities, because his life, physical integrity, security, or personal liberties have been abridged or are directly threatened by one of the following factors:internal armed conflict, internal disturbances or tension, generalized violence, massive violations of human rights, infractions of international humanitarian law, or other circumstances resulting from the foregoing factors that can alter or have altered drastically the public order.[87]

Forcible displacement infringes on the right to liberty of movement and freedom to choose one's residence, guaranteed in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and, in the Americas, by the American Convention on Human Rights.[88]This right is subject to restrictions that are provided by law and necessary to protect national security, public order, public health or morals, or the rights and freedoms of others, and it is derogable in times of public emergency.[89]As Francis Deng has observed:

[P]opulation movements may be undertaken during genuine public emergencies, such as armed conflicts, severe communal or ethnic violence, and natural or human-made disasters.These, however, must be "strictly required by the exigencies of the situation" and must not be inconsistent with other State obligations under international law or involve invidious discrimination.Even in such cases, therefore, the forced movement must not violate non-derogable human rights.[90]

The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights applied these principles in a case involving the forcible relocation of Miskito communities in Nicaragua.[91]Summing up the commission's analysis, Deng writes:

Relevant principles of protection relating to forced relocation . . . may be deduced as follows:(a) official proclamation of a state of emergency has to be communicated effectively to avoid terror and confusion when it involves relocation; (b) relocation should only be proportionate to the danger, degree and duration of a state of emergency; (c) relocation must last only for the duration of an emergency.[92]

When forcible displacement occurs in an armed conflict, it may violate the obligation to protect civilians, recognized in the Fourth Geneva Convention and in Protocols I and II to the Geneva Conventions.[93]In particular, article 17 of Protocol II, which deals with non-international armed conflicts, provides:

1.The displacement of the civilian population shall not be ordered for reasons related to the conflict unless the security of the civilians involved or imperative military reasons so demand.Should such displacements have to be carried out, all possible measures should be taken in order that the civilian population may be received under satisfactory conditions of shelter, hygiene, health, safety and nutrition.

2.Civilians shall not be compelled to leave their own territory for reasons connected with the conflict.[94]

As Deng notes, "This wording makes clear that article 17 prohibits, as a general rule, the forced movement or displacement of civilians during internal hostilities. . . .The forced displacement of civilians is prohibited unless the party to the conflict were to show that (a) the security of the population or (b) a meticulous assessment of the military circumstances so demands."[95]All sides to an armed conflict, including armed opposition groups, must observe this prohibition.

Forced displacement also violates the right to protection from interference with one's home, guaranteed by the ICCPR and the American Convention, and may violate the right to an adequate standard of living (including adequate housing), set forth in the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.[96]Displacement is frequently preceded or accompanied by violations of the right to life, the right to freedom from torture and cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment or punishment, the right to security of the person, and other rights.[97]

The Colombian constitution provides that international treaties ratified by the state prevail over domestic legislation.[98]In addition, the Colombian Constitutional Court has directed public officials to follow the Guiding Principles, in addition to constitutional norms, in taking action to address displacement.[99]

Applying the Guiding Principles in a landmark January 2004 decision, the Constitutional Court reviewed the government's response to the displacement crisis."The level of coverage of every component of the policy is insufficient" and "there exist at all levels serious problems relating to the institutional capacity of the state to protect the rights of the displaced population," the court found.[100]Indeed, the problems were such that they amounted to an "unconstitutional state of affairs," a finding of a "repeated and constant violation of fundamental rights affecting a multitude of persons and requiring the intervention of distinct entities to attend to problems of a structural nature."[101]The court ordered the state to identify the number and needs of the displaced population, define a comprehensive national plan of action, determine the resources necessary to implement the plan of action, and, within six months of the court's decision, ensure thatall displaced persons enjoy a "minimum level of protection" of their rights.[102]

In response to the decision, the government enacted a new national plan of action and substantially increased the budget for programs that assist displaced persons.[103]Nevertheless, in a series of three orders issued in August and September 2005, the court found that the government's response fell far short of what was required to remedy the unconstitutional state of affairs.[104]

The Constitutional Court has now given the government until December 1, 2005, to submit a plan for allocating the necessary funding to the various government agencies responsible for assisting displaced persons.[105]It also directed the government to submit periodic reports indicating the amounts spent by each government agency on assistance for displaced persons.[106]

IV. Registration and Humanitarian Assistance

S.B. and his wife arrived in Bogot in July 2004 and made their way to the Social Solidarity Network, the government umbrella agency that coordinates humanitarian assistance for displaced persons."We got to the network [office] at 7 a.m.," S.B. reported."At 5 p.m. they sent us here," he said, referring to a shelter run by a community group."We'd spent practically the whole day there, without breakfast, lunch, or dinner, and without going to the bathroom.At night, we had to sleep on the floor.They didn't give us anything.They didn't resolve anything," he told our researcher.They returned to the office the following day to make their declaration and complete the registration process.Fifteen days after they reported to the network, he said, "We haven't received anything yet. . . .They haven't even given us rice or a mattress."[107]

As frustrating as their situation was, S.B. and his wife did not experience the delays in registration that were common two or three years ago and still occur in some cases.When A.B., an adult male from Caldes, arrived in Bogot in 2003, he told us, "I had to wait in line two or three days, sleeping in the street, just to get in to see them [the Social Solidarity Network].At 5 a.m., there were already 500 people in line. . . .Three days sleeping in the streets, with children, with the whole family, . . . one gets fed up with that."[108]His account was not unusual; Human Rights Watch spoke to at least half a dozen other families who reported similar experiences in registering between 2001 and 2003.[109]

Some families who arrived in Bogot in 2005 described similar experiences.A.R. moved to Ciudad Bolvar from Cundinamarca in May 2005 with fifteen members of her family after paramilitaries threatened them.She went to the Social Solidarity Network's officein Bogot at 4 a.m. to wait in line to make a declaration."They were only letting in ten people at a time," she said.She waited in line two days just to be seen, she told Human Rights Watch.[110]

In the last several years, the Social Solidarity Network has made efforts to streamline the registration process.'Three years ago, they gave appointments for the declaration," said Adriana Len, an official with the Network."But there have been many improvements in this area.Now the declaration is taken immediately, or people are given an appointment at the latest for the next day."[111]Teresa Daz, a member of a displaced community organization and herself a displaced person, generally agreed with this assessment."Now things have gotten better," she said."It seems they have improved the [Social Solidarity Network's] responsiveness."[112]

In particular, the government has made an effort to establish unified offices that combine Colombia's bewildering array of social service agencies under one roof.Known as Attention and Orientation Units (Unidades de Atencin y Orientacin, UAOs), these offices are intended to allow for greater coordination among the agencies that have a role in addressing the needs of displaced persons.We visited one such office in Soacha, a municipality just outside the city limits of Bogot that receives a significant number of displaced persons.As a result of the effort to establish such offices, an official with the International Organization for Migration told us, "There aren't the enormous lines that there were before."[113]Even so, government agencies may by law take up to fifteen business days to complete the registration process.[114]

Registration is critical because it is the key to obtaining humanitarian assistance, health care, and other services offered to displaced persons.But it does nothing to address the immediate needs of displaced persons unless it is accompanied by emergency assistance.Under Colombian law, displaced families are eligible for three months of humanitarian assistance, but only after the registration process is completed.[115]This aid may be extended for another three months in cases of extreme need.[116]

It is not clear that displaced families are able to receive any assistance to help with their immediate needs before the registration process is completed.In an August 2004 interview, Adriana Len, an official with the Social Solidarity Network, told Human Rights Watch that in addition to ordinary humanitarian assistance, displaced families with immediate needs could receive emergency assistance as soon as they presented themselves at the Social Solidarity Network's offices to make their declaration.[117]In theory, this possibility would mitigate one of the consequences of the fifteen-day waiting period-that families in dire need will wait two weeks or more before receiving any help with food, shelter, or clothing.

But in September 2005, Ms. Len told our researcher that the Social Solidarity Network does not provide emergency assistance before the declaration is processed and registration completed."We would get a lot of non-displaced people coming in for assistance" if the Network provided such aid, she explained.Instead of emergency assistance, she told us that the Network would immediately process the declaration.When our researcher pointed out that the failure to provide emergency aid would mean that many families would not get assistance for fifteen business days or longer, she replied that the national average for processing declarations was less than ten business days.She left the room to double-check that figure with a colleague and said on her return, "The average was 9.24 business days in August [2005], or twenty-three calendar days."[118]

The failure to provide emergency aid means that people get no government assistance in the hours and days immediately after their displacement and that most will see nothing until two weeks or more after they have made it to a government office to file a declaration."During those fifteen days, people remain without any assistance," said Camila Moreno, then the head of the Displacement Section in the ombudsman's office.[119]Juan Carlos Monge, an official in the office of the U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights, suggested that some families still experienced lengthy delays in registration, which in turn meant delays in receiving humanitarian aid."They can't get humanitarian assistance until they receive certification of their situation as displaced persons," he said."There are people waiting three, four, even six months before they receive anything."[120]

In addition, we heard that displaced families experienced problems in receiving humanitarian aid even after they have completed the registration process.In August 2004, for example, some of the Social Solidarity Network's offices were giving families a date to return to get humanitarian assistance, Teresa Daz told us."The date is for two months ahead.Sometimes the date comes, and they give you another date.There was a gentlemen who went to make the declaration six months ago [in February 2004] who was given a date for September 6," she said.[121]

In September 2005, we heard of several cases of families who had not yet received assistance even though they had made declarations with the Social Solidarity Network two or three months before.For instance, A.R. told us that she and fifteen others in her family arrived in Ciudad Bolvar in May 2005 and made a declaration in early June."They told us we would hear back within fifteen days of making the declaration," she said."We haven't received any response.We haven't gotten any help from the Network."[122]

In fact, a December 2004 UNHCR study found that only around half of the families registered over a two-year period received humanitarian assistance."Access to emergency assistance is still limited," UNHCR found."Between August 2002 and August 2004 only 50 percent of the population registered during that time were attended to."Persons involved in large-scale displacement-that is, groups of ten families or more-were far more frequently the recipient of such aid than those who had been displaced individually, the agency noted.[123]

As a result, displaced persons routinely seek court orders directing government agencies to provide them with assistance.These cases, known as tutelas, are so commonplace that they have become virtually a part of the process of applying for government assistance, Colombia's constitutional court noted in an influential January 2004 decision.[124]But many displaced persons are not in a position to bring a court case in order to get humanitarian assistance, nor should they have to do so. "I can't wait for a tutela," L.D. told Human Rights Watch."While I wait for a tutela, my daughter will have gone three or four months without food.There are days that we've eaten nothing but flour."[125]

If displaced families are successful in receiving humanitarian assistance, the three-month limit in all but exceptional cases means that they are unlikely to have put their lives on stable footing before assistance runs out.As the Constitutional Court observed:

The design of the emergency humanitarian assistance, which places emphasis on temporal factors, turns out to be too rigid to meet the needs of the displaced population effectively.The time limit of three months does not correspond to the reality of the continued violation of their rights, in that the continuation of this assistance does not depend on objective conditions of the population's necessity but rather on the simple passage of time.[126]

In some cases, families have not registered because they have been attending to their immediate needs or did not know how to complete the process."We've been looking for work.We haven't had time to go.We don't know how to make the declaration," said K.L., who arrived from Tolima with her husband and two-year-old daughter in June 2005."We would like to do it in the future."[127]

A final complication, one that is more difficult to address, are the reports we heard that some displaced persons did not register out of fear that harm would come to them if they provided their addresses and other identifying information to officials."No," E.P. said, "I didn't go.I didn't go out of fear.I was afraid of what might happen, that I might be killed, even."[128]"There's a lack of trust in institutions; therefore, people don't always register," one humanitarian official told Human Rights Watch."They are completely unprotected by state institutions."[129]A June 2005 field report from Mdecins sans Frontires (MSF) explained in more detail:

MSF has also found that some of the people who know about the [health] benefits available to them fear providing information on their own whereabouts.In order for an internally displaced person to qualify for benefits the government requires the confirmation of a person's identity both with the municipality of current residence and with the area from which they have fled.

For those who have escaped persecution in former homes . . . authorizing the government to conduct a process of verification raises serious concerns.If the details of a person's whereabouts were to fall into the wrong hands, it might endanger them.Thus, free preventive health care eludes thousands of displaced people who are wary of compromising their whereabouts to access medical treatment.[130]

OCHA's Inter-Agency Internal Displacement Division received similar reports during its January 2005 mission to Colombia.[131]

The Cost of Humanitarian Assistance

Providing all internally displaced families with humanitarian aid and other needed services, such as access to education and health services, would be costly.The Office of the General Comptroller of the Republic (Contralora General de la Repblica) estimates that the cost per person per year is in excess of 13 million pesos (about U.S.$5,600) and notes that the various Colombian government agencies responsible for implementing Law 387 spent over 436,500 pesos, about U.S.$175 million, between 2000 and 2003.Full coverage would require spending eight times as much, the office estimated.Even so, it found that actual expeditures for the years 2001 and 2002 were 32 percent less than the funds allocated for assistance to internally displaced persons.[132]If the same is true for the years going forward, these agencies have additional resources that they can draw upon to comply with the Constitutional Court's 2004 decision (see below) and address the urgent needs of Colombia's displaced population.

The United States provided more than U.S.$700 million to the government in 2004, mostly in military aid.The U.S. Agency for International Development's Reintegration Program for Displaced Families and Other Vulnerable Groups will provide some U.S.$33 million in FY 2005 and is expected to continue at least through FY 2008.[133]In October 2005, USAID entered into an agreement with the International Organization for Migration (IOM) and the Pan American Development Foundation (PADF) under which USAID will provide U.S.$100 million to fund a joint IOM/PADF project to provide assistance to internally displaced persons and other vulnerable groups over a five-year period, suggesting that the agency has decided to extend its displacement program at least until 2010.[134]

Europe is now the largest donor to Colombia's humanitarian, human rights, and peace programs.Between 2000 and 2003, the Humanitarian Aid Department of the European Commission (ECHO) provided 33.9 million (U.S. $41.8 million) in support for emergency food and shelter assistance, a sum that was equivalent to 56 percent of the government Social Solidarity Network's budget during the same period.With other aid programs included, the European Union contributed a total of U.S.$52.5 million in humanitarian aid for displaced persons.The European Union has pledged over 330 million (U.S.$410 million) in aid to Colombia in a package that ends in 2006.[135]

International Standards and Colombian Law

The U.N. Guiding Principles establish that "[n]ational authorities have the primary duty and responsibility to provide protection and humanitarian assistance to internally displaced persons within their jurisdiction."[136]At a minimum, the principles provide that the state or other competent authorities should provide displaced persons with essential food and potable water, basic shelter and housing, appropriate clothing, and essential medical services and sanitation.[137]These Principles flow from the obligation to protect the survival of civilians, recognized in the Fourth Geneva Convention and in Protocols I and II of the Geneva Conventions, and the right to an adequate standard of living, articulated in the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights and the Convention on the Rights of the Child.[138]The Guiding Principles do not limit this assistance to a particular time frame; instead, they "identify rights and guarantees relevant to . . . protection and assistance during displacement," as well as protection from displacement and protection during return, resettlement, and reintegration.[139]

Colombia's Law 387 sets forth the process that displaced persons must follow to register and receive humanitarian assistance.As the first step, displaced persons must make a declaration before one of a number of government officials-the attorney general's office (Procuradura General de la Nacin), the office of the ombudsman (Defensora del Pueblo), or municipal or district personeras and then present a copy to the Social Solidarity Network for registration.[140]Those who make a declaration within one year of the events leading to their displacement are eligible for emergency humanitarian assistance.[141]After the Network receives the declaration, it has fifteen business days to verify the facts alleged.[142]The Network will not register an individual if the allegations he or she has made are found to be untrue, if they do not amount to displacement as defined in Law 387, or if the declaration is made more than one year after the events giving rise to displacement have taken place.[143](Declarations made after one year only allow access to state programs providing support for return, reestablishment, or relocation, subject to the availability of funds.[144])If the declaration is verified and the individual is registered, he or she is notified of the fact of registration.[145]Once registered, displaced persons are eligible for humanitarian assistance for three months.[146]The law allows for the possibility of extension of humanitarian assistance for another three months, but only if (1) a member of the household has a physical or mental disability certified by a doctor, and then only if the condition was set forth in the original declaration; (2) the head of the household is a woman or is over sixty-five, and then only if that fact is set forth in the declaration; (3) the case involves a terminal illness that has been medically certified; or (4) in the Social Solidarity Network's judgment, there exists a situation similar to those set forth above.[147]The Social Solidarity Network may exclude an individual from the registry if it finds a "lack of cooperation" or "repeated refusal by the displaced person to participate in programs and events" offered by the Social Solidarity Network.[148]

In January 2004, as noted above, the Colombian Constitutional Court declared that the "repeated failure to provide [displaced persons] with opportune and effective protection on the part of the various [government] authorities charged with their care" amounted to a "state of unconstitutional affairs" (estado de cosas inconstitucional).[149]The court ordered the state to take remedial measures, among other things, by reforming its policies for addressing internal displacement and by assigning adequate resources to the maximum of their availability.[150]

V. Access to Education

F.L., a displaced woman working in a community kitchen in El Pozn, on the outskirts of Cartagena, described the problems she and her neighbors experience when they try to enroll their children in the public schools."The first problem is space:There usually isn't any room.Second is the matriculation fee-you have to pay to enroll your child.Third, the schools require identification," she told Human Rights Watch.[151]

In another interview, sixteen-year-old Carmela E. identified the cost of schooling as her chief concern."The most difficult thing about studying here [in Bogot] is that you have to pay," she said."Here for the ninth grade, the matriculation fee is 160,000 pesos [U.S.$64] plus school supplies."She estimated that her school supplies bring her costs for the year up to 250,000 pesos (U.S.$100).On top of that amount, she must purchase the required school uniform and black shoes."I try to watch the costs to make things easier for my father.My brother is also in school.It is difficult to buy things."[152]

As these interviews indicate, displaced children face significant hurdles in continuing their education.In some cases, these barriers are direct consequences of their status as displaced persons, as when they are required to produce forms of identification they no longer possess.In other instances, they are harmed by the school's failure to adhere to legal obligations intended to protect displaced persons.For example, there may simply be no space available, despite legal provisions that require state schools to enroll displaced children who arrive in their communities.Finally, displaced children face the same barriers in access to education that all children in their communities face, and their particularly vulnerable situation means that these hurdles will be especially difficult to surmount.The expenses associated with attending school-the fees for matriculation, extra charges for examinations, "voluntary" monthly contributions, and the cost of uniforms, books, and school supplies-are one such barrier, often preventing displaced children from attending classes.In addition, economic pressures on displaced families often mean that older children must leave school in order to care for younger siblings or to contribute to the family income.

Displaced children face these hurdles after their education has already been interrupted by the need to flee their communities.As a result of the combination of these factors, "[t]hey lose an important part of their schooling, one that is sometimes never recovered," a report prepared by the ombudsman's office notes.[153]

Considering the challenges displaced children face, it is not surprising that they are far more likely than children in the general population not to attend school.When the ombudsman's office analyzed Ministry of Education data for 2002, for example, it found that only 10,700 of the 122,200 displaced children of school age in twenty-one receiving communities were actually matriculated.That is, only 8.8 percent of the displaced children in those communities were enrolled in school.The enrollment rate for all children of school age in those communities was 92.7 percent.[154]Similarly, in its survey of displaced populations in six departments, the IOM found that 52 percent of displaced children between the ages of twelve and eighteen were not in school.In comparison, only 25 percent of youths of the same age range in Colombia's population as a whole were out of school, according to National Administrative Statistics Department (Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadstica) data.[155]

When Human Rights Watch asked officials with the Social Solidarity Network about their strategies to eliminate school fees and other expenses associated with attending school, they referred us to a program known as Families in Action (Familias en Accin).Modeled after a Mexican initiative and financed by World Bank and Inter-American Development Bank loans, the program provides cash incentives for families to keep their children in school.While this effort is a laudable one that should be continued, it does not specifically target displaced children, and none of the families we met were benefiting from the program.

The Lack of Space for Displaced Children

The Ministry of Education and the Social Solidarity Network have issued a circular that instructs schools to enroll displaced children.In practice, however, children are often unable to attend school for one of several related reasons.The ombudsman's office notes: