“You Can Die Any Time”

Death Squad Killings in Mindanao

I. Summary

If you are doing an illegal activity in my city, if you are a criminal or part of a syndicate that preys on the innocent people of the city, for as long as I am the mayor, you are a legitimate target of assassination.

—Davao City Mayor Rodrigo Duterte, February 2009.

At around 6 p.m. on July 17, 2008, 20-year-old Jaypee Larosa left his home in Lanang, a quiet residential neighborhood in Davao City, to go to a nearby Internet cafe. An hour later his family heard six successive gunshots. A neighbor rushed into their house to say one of their sons had been shot in front of the café. Jaypee was taken to a hospital, but was declared dead on arrival.

Eyewitnesses said that Larosa had been shot by three men in dark jackets who had arrived on a motorcycle. After they shot him, one of them removed the baseball cap Larosa was wearing and said, “Son of a bitch. This is not the one,” and they immediately left the scene. It appears that the assailants were seeking to kill another man, a suspected robber. No one has been arrested for Larosa’s murder. His family is unaware of the police having taken any meaningful action in the case.

Chicks placed atop the coffin of Jaypee Larosa, who was killed by unidentified gunmen in Davao City on July 17, 2008, to symbolically peck on the conscience of the killers. © 2008 Human Rights Watch

Jaypee Larosa is just one of hundreds of victims of unresolved targeted killings committed over the past decade in Davao City and elsewhere in the Philippines. Dozens of family members have described to Human Rights Watch the murder of their loved ones, all killed in similar fashion. Most victims are alleged drug dealers, petty criminals, and street children, some of whom are members of street gangs. Impunity for such crimes is nearly total—few such cases have been seriously investigated by the police, let alone prosecuted.

Although reports of targeted killings in the Philippines, particularly in Mindanao, are not new, the number of victims has seen a steady rise over many years. In Davao City, the number has risen from two in 1998 to 98 in 2003 to 124 in 2008. In 2009, 33 killings were reported in January alone. In recent years the geographical scope of such killings has expanded far beyond Davao City and other cities on the southern island of Mindanao to Cebu City, the Philippines’ second largest metropolis. An already serious problem is becoming much worse.

This report provides an anatomy of death squad operations. It is based on our investigations of 28 killings, 18 of which took place in 2007 and 2008. The victims include children as young as 14. In researching this report, we found evidence of complicity and at times direct involvement of government officials and members of the police in killings by the so-called Davao Death Squad (DDS). We obtained detailed and consistent information on the DDS from relatives and friends of death squad members with direct knowledge of death squad operations, as well as journalists, community activists, and government officials who provided detailed corroborating evidence.

According to these “insiders,” most members of the DDS are either former communist New People’s Army insurgents who surrendered to the government or young men who themselves were death squad targets and joined the group to avoid being killed. Most can make far more money with the DDS than in other available occupations. Their handlers, called amo (boss), are usually police officers or ex-police officers. They provide them with training, weapons and ammunition, motorcycles, and information on the targets. Death squad members often use .45-caliber handguns, a weapon commonly used by the police but normally prohibitively expensive for gang members and common criminals.

The insiders told Human Rights Watch that the amo obtain information about targets from police or barangay (village or city district) officials, who compile lists of targets. The amo provides members of a death squad team with as little as the name of the target, and sometimes an address and a photograph. Police stations are then notified to ensure that police officers are slow to respond, enabling the death squad members to escape the crime scene, even when they commit killings near a police station.

The consistent failure of the Philippine National Police to seriously investigate apparent targeted killings is striking. Witnesses to killings told Human Rights Watch that the police routinely arrive at the scene long after the assailants leave, even if the nearest police station is minutes away. Police often fail to collect obvious evidence such as spent bullet casings, or question witnesses or suspects, but instead pressure the families of victims to identify the killers.

Our research found that the killings follow a pattern. The assailants usually arrive in twos or threes on a motorcycle without a license plate. They wear baseball caps and buttoned shirts or jackets, apparently to conceal their weapons underneath. They shoot or, increasingly, stab their victim without warning, often in broad daylight and in presence of multiple eyewitnesses, for whom they show little regard. And as quickly as they arrive, they ride off—but almost always before the police appear.

The killings probably have not generated the public outrage that would be expected because most of the victims have been young men known in their neighborhood for involvement in small-scale drug dealing or minor crimes such as petty theft and drug use. Other victims have been gang members and street children.

Frequently, the victims had earlier been warned that their names were on a “list” of people to be killed unless they stopped engaging in criminal activities. The warnings were delivered by barangay officials, police officers, and sometimes even city government officials. In other cases, the victims were killed immediately after their release from police custody or prison, or shortly after they returned from hiding.

Human Rights Watch also investigated a number of cases in which those killed were seemingly unintended targets – victims of mistaken identity, unfortunate bystanders, and relatives and friends of the apparent target. Death squad members also have been victims of death squad killings, possibly because they “knew too much,” failed to perform their tasks, or became too exposed. Some Davao City residents also expressed the belief that some death squad members have become guns-for-hire.

Witnesses and family members who provide information to police on the killings, including the names of suspects, say that police either fail to follow up on the leads, whether they have started a criminal investigation, or if they have made any progress in their investigation. In many cases, witnesses are too afraid to come forward with information, as they believe they could become death squad targets by doing so.

The words and actions of long-time Davao City Mayor Rodrigo Duterte, some of which were quoted at the start of this report, indicate his support for targeted killings of criminal suspects. Over the years, he has made numerous statements attempting to justify the killing of suspected criminals. In 2001-2002, Duterte would announce the names of “criminals” on local television and radio—and some of those he named would later become victims of death squad killings.

Duterte claims that Davao City has achieved peace and order under his rule. But with killers roaming the streets with the comfort of state-protected impunity, the city remains a very unsafe place. Available information points to an increasing number of death squad killings, including of persons such as Jaypee Larosa who appeared to have been in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Duterte and other local officials continue to deny the existence of any death squad. But in recent years, mayors and officials of other cities have made statements attempting to justify similar killings in their own cities. Sadly, Davao City is seen by some as a model for fighting crime.

Just as disappointing, there is an almost complete lack of political will by the government at both local and national levels to address targeted killings and take action against the perpetrators. Based on consistent, detailed, and compelling accounts from families and friends of victims, eyewitnesses of targeted killings, barangay officials, journalists, community activists, and the “insiders,” Human Rights Watch has concluded that a death squad and lists of people targeted for killings exist in Davao City. We also conclude that at least some police officers and barangay officials are either involved or complicit in death squad killings. Human Rights Watch believes that such killings continue and the perpetrators enjoy impunity largely because of the tolerance of, and in some cases, outright support from local authorities.

The failure to dismantle the Davao Death Squad and other similar groups, prosecute those responsible, and bring justice to the families of victims lies not only with local authorities. The administration of Philippine President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo has largely turned a blind eye to the killing spree in Davao City and elsewhere. The Philippine National Police have not sought to confront the problem. And the inaction of the national institutions responsible for accountability, namely the Department of Justice, the Ombudsman’s Office, and the Commission on Human Rights, has fueled widespread impunity.

The continued death squad operation reflects an official mindset in which the ends are seen as justifying the means. The motive appears to be simple expedience: courts are viewed as slow or inept. The murder of criminal suspects is seen as easier and faster than proper law enforcement. Official tolerance and support of targeted killing of suspected criminals promotes rather than curbs the culture of violence that has long plagued Davao City and other places where such killings occur.

Until national authorities take decisive action to disband the Davao Death Squad and all other similar groups that may be operating in other cities, and prosecute perpetrators and complicit officials, the pledges of President Arroyo and other government officials to respect basic human rights and uphold the rule of law will remain hollow.

Key Recommendations

The Philippine government and local authorities in Davao City, General Santos City, Digos City, and Tagum City, as well as other cities believed to be using or tolerating death squads, should urgently take measures to stop the killings and hold perpetrators accountable. More specifically, Human Rights Watch urges that:

- President Arroyo should publicly denounce extrajudicial killings and local anti-crime campaigns that promote or encourage the unlawful use of force. She should order the Philippines National Police, the Ombudsman’s Office, and the National Bureau of Investigation to investigate the targeted killings of alleged drug dealers, petty criminals, and street children, and pledge that state employees who are found to be involved or complicit in such killings will be prosecuted in accordance with the law.

- The Philippine National Police should conduct thorough investigations into targeted killings of alleged drug dealers, petty criminals, and street children in Davao City, General Santos City, Digos City, Tagum City and investigate the alleged involvement and complicity of police officers in such killings, including their failure to investigate the killings rigorously and prepare cases for prosecution.

- The Commission on Human Rights should investigate and report publicly and promptly on the Davao Death Squad and other similar groups and the involvement of the PNP and city governments in Davao City and other cities where death squad activity has been reported.

- As part of its inquiry into the targeted killings of alleged drug dealers, petty criminals, and street children, the Commission on Human Rights should investigate whether Rodrigo Duterte, Mayor of Davao City, and other mayors and governors in the Philippines have been involved or complicit in death squad killings, or whether statements by government officials may have incited violence.

- The mayor of Davao City and other local officials should cease all support, verbal or otherwise, for anti-crime campaigns that entail violation of the law, including targeted killings of alleged drug dealers, petty criminals, and street children. They should arrest and prosecute perpetrators of the killings and state employees, including law enforcement officers, who are found to be involved or complicit in death squad operations.

- The Philippine Congress should conduct hearings on the Davao Death Squad and other similar groups in the Philippines, with special attention paid to whether local officials and police officers are involved or complicit in such killings.

- The United States, European Union, Japan, the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank should keep their pledges on human rights, the rule of law, and good governance, press the Philippine government to initiate investigations into alleged targeted killings in cities, and to publicize the results of its investigations and plans to dismantle the Davao Death Squad and other similar groups.

More detailed recommendations are set forth at the end of this report.

II. Note on Methodology

In July 2008, Human Rights Watch investigated 28 killings in Davao City, General Santos City, and Digos City, focusing on cases where circumstances suggested a death squad might have been involved. Most of the killings we investigated occurred in 2007 and 2008, although a small handful had taken place as long ago as 2001. Human Rights Watch interviewed about 40 family members and friends of victims, as well as eyewitnesses to apparent targeted killings.

Human Rights Watch also interviewed nine people who had insider knowledge of the structure and functioning of the “Davao Death Squad,” because they had family, friends, or neighbors who were members of the DDS, had talked directly to DDS members, or had dealings with them. We also spoke with local human rights activists, lawyers, and journalists, who have been looking into the killings for years and who, in many cases, were able to provide detailed corroborating evidence.

We conducted interviews in English and Cebuano (the predominant local language) with the aid of interpreters. We have withheld the names of many of the people we interviewed for security reasons, using pseudonyms for those repeatedly quoted (we note such use in the relevant citations). Wherever possible and in the majority of cases, interviews were conducted on a one-on-one basis.

In September 2008, Human Rights Watch sent letters to the Philippine officials listed below to obtain data and solicit views on the killing of alleged drug dealers, petty criminals, and street children in Davao City, General Santos City, Digos City, Tagum City, and Cebu City. We sent follow-up letters a month later to those who did not reply.

Human Rights Watch wrote to the following officials:

Rodrigo R. Duterte, Mayor, Davao City

Pedro B. Acharon, Jr., Mayor, General Santos City

Arsenio Latasa, Mayor, Digos City

Rey Uy, Mayor, Tagum City

Tomas R. Osmeña, Mayor, Cebu City

Rodolfo Del Rosario, Governor, Province of Davao del Norte

Douglas R. Cagas, Governor, Province of Davao del Sur

Andres G. Caro II, Regional Director, PNP Regional Office XI

Ramon C. Apolinario, City Director, PNP Davao City

Alberto P. Sipaco, Jr., Regional Director, Commission on Human Rights, Davao City

Humphrey Monteroso, Deputy Ombudsman for Mindanao

Antonio B. Arellano, Regional State Prosecutor, Region XI

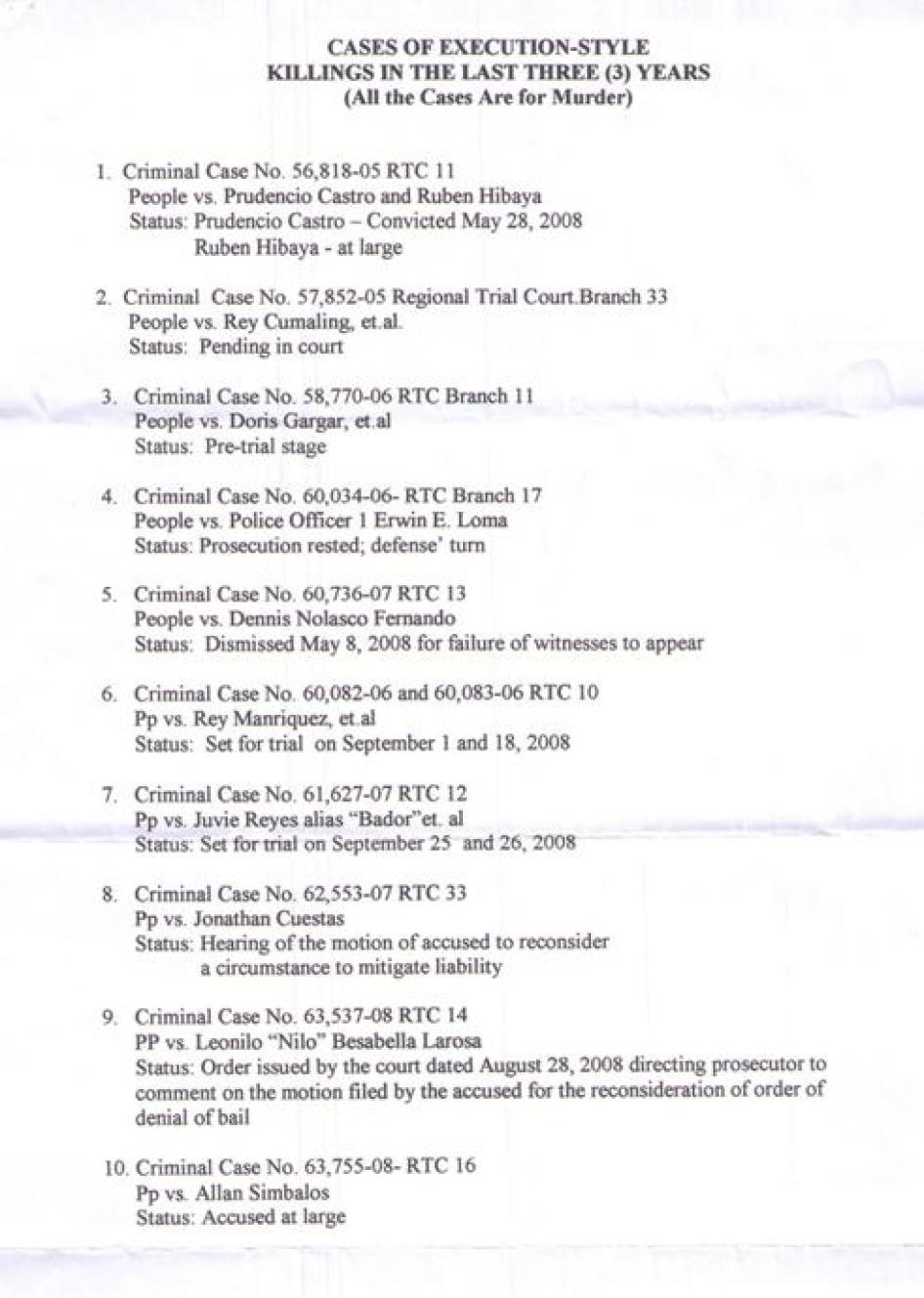

Raul D. Bendigo, City Prosecutor, Davao City

At this writing in February 2009, Raul D. Bendigo, Davao city prosecutor, Tomas R. Osmeña, mayor of Cebu City, and Pedro B. Acharon Jr., mayor of General Santos City, had responded. The other officials listed above did not respond or asked Human Rights Watch to contact other government agencies or officials. Some of Human Rights Watch’s letters and Philippine officials’ responses are attached in this report’s appendix. The rest of the letters are posted on the Philippines page of the Human Rights Watch website: www.hrw.org.

III. Map of Mindanao

Map of cities in Mindanao with reported targeted killings of suspected criminals. © 2009 Human Rights Watch

IV. Background

Legacy of Violence

Mindanao, the largest of the Philippines’ southern islands, has been a focal point for insurgencies and conflict for decades. Militant Muslim groups, communist insurgents, government security forces, and government-backed militias and “vigilante groups” have all been responsible for numerous serious human rights abuses—including abductions, torture and killings—against suspected adversaries and ordinary civilians.

Since 1969 the New People’s Army (NPA), the armed wing of the Communist Party of the Philippines, has been fighting to topple the Philippine government.[1] The communist insurgency reached its greatest strength in the mid-1980s, prior to the “People Power” revolution of 1986 that removed then President Ferdinand Marcos from power. During that period, Mindanao was one of the hotbeds of the NPA insurgency. NPA forces have been responsible for numerous abuses, including targeted killings of persons whom they identify as “enemies,” and the use of violence to extort businesses and individuals.[2] So-called “sparrow units” have summarily executed those cited for “crimes against people,” such as criminals, military informants and abusive police officers.[3]

Since the early 1970s, the Philippine government also has been engaged in an intermittent armed conflict with Muslim separatist groups in Mindanao.[4] The conflict has resulted in the death of an estimated 120,000 people, mostly civilians, and displacement of some two million more. A shaky peace currently exists. More radical groups such as the Abu Sayyaf Group emerged in the 1990s and have been responsible for numerous bombings and other attacks on civilians, primarily in Mindanao and other southern islands.[5]

The Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) and the Philippine National Police (PNP) have for many years been implicated in insurgency-related human rights violations. In a June 2007 report, “Scared Silent: Impunity for Extrajudicial Killings in the Philippines,” Human Rights Watch documented the involvement of government security forces in the extrajudicial killing of leftist politicians and activists, journalists, outspoken clergy, anti-mining activists, and agricultural reform activists. Only a handful of the perpetrators of such killings have ever been convicted.

To fight the NPA insurgents, the government has long relied on the use of poorly trained paramilitary forces such as the Civilian Home Defense Force and its successor, the Citizen Armed Forces Geographical Units (CAFGU). These armed militias have tortured and murdered people they believed support or sympathize with the NPA. By operating outside the military chain of command, they also have given the armed forces a level of “deniability” for serious abuses they commit.[6]

The government has also actively enlisted so-called vigilante groups to fight the NPA. By popular legend, the birth of modern vigilantism in the Philippines traces back to Davao City. In April 1987, in a slum in Davao City, three former rebels shot to death a notorious NPA assassin. This group, called Alsa Masa (“Masses Arise”), prospered thanks to deep public resentment against the NPA, which had killed numerous people, many in error, in a violent internal purge starting in late 1985 and alienated once supportive populations.[7]

With the endorsement of then President Corazon Aquino and under the patronage of a local military commander, Lt. Col. Franco Calida, Alsa Masa rapidly expanded, using coercive recruiting methods and extortion. They required each household to provide a member for their nightly patrols, and painted homes of those who didn’t comply with an “X.” Jun Pala, a radio broadcaster who was an early supporter of Alsa Masa, routinely threatened Alsa Masa critics with retribution.

In many areas throughout the Philippines, local military commanders created and provided arms to vigilante groups, hoping to emulate Davao City’s counterinsurgency experiment with Alsa Masa.[8] A wide variety of vigilante groups were reported in the provinces of North Cotabato, Misamis Occidental, and Zamboanga Del Sur in Mindanao and on the islands of Negros, Cebu, and Leyte, among other areas. When these groups invariably became involved in serious abuses, enthusiasm steadily waned and they disappeared in the 1990s.

Problem of Illicit Drugs

The Philippine government has been battling drug syndicates for decades. The country has the highest estimated methamphetamine prevalence rate in the world, and continues to be a producer, consumer, and transshipment point for methamphetamine.[9] Illicit drug laboratories, which used to be found in or near Metropolitan Manila, are now found in various parts of the country, including Mindanao. In one such discovery, the authorities found a laboratory in Zamboanga City in Mindanao in February 2008 that reportedly had the capacity to produce 1,000 kilograms of methamphetamine each month.[10]

In 2007, the last year for which statistics are available, the authorities identified 249 local drug groups and eight transnational drug groups operating in the country, up sharply from the 149 local and seven transnational groups identified in 2006. There was no reason given for the surge. They also cited “intelligence reports” as indicating that illegal drugs from foreign countries were entering through coastal areas in central and southern Philippines.At the same time, the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency reported a decreasing number of patients treated at various drug-rehabilitation facilities, again without offering explanation or analysis.[11]

A 2007 US State Department report concluded that “corruption, low morale, inadequate resources and salaries, and lack of cooperation between police and prosecutors” were hampering drug prosecutions in the Philippines. It noted that the slow process of prosecuting cases demoralizes law enforcement personnel and permits drug dealers to continue their drug business while awaiting court dates. It said the leading cause for the dismissal of cases is the non-appearance of prosecution witnesses, including police officers.[12] Davao City, an urban center of Mindanao, is a major market for illicit drugs.

Davao City

In the 1970s and 1980s, Davao City was known as the “murder capital” of the Philippines. Communist insurgents and government security forces killed each other in the daytime on Davao City’s streets. NPA assassins killed corrupt police officers, suspected informants, and drug dealers. The Agdao district of Davao City became a communist bastion known as “Nicaragdao” (after Sandinista-led Nicaragua), where the NPA routinely committed targeted killings.[13]

The NPA was largely driven out of Davao City by the late 1980s. The government claimed that Alsa Masa and other vigilante groups were chiefly responsible, but the NPA’s demise also has been explained as due to a bloody internal purge in the NPA that left its ranks shattered. The NPA’s decline in Davao City was repeated throughout the Philippines in the ensuing decade.[14] In the words of Philippine President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, the NPA today remains a low-level threat.[15]

In recent years, Davao City has developed into a sprawling urban metropolis of 1.44 million residents, and a business, investment, and tourism hub for the southern Philippines. It has attracted a large number of economic migrants from all over Mindanao and elsewhere in the Philippines. Hundreds of thousands are unable to find stable jobs and end up in crowded slum areas. They include an estimated 3,000 street children[16]—40 to 50 percent of whom are girls—who roam the streets of Davao City to make money and avoid physical abuse at home. Many join youth gangs for bonding and survival.[17]

A resurgence of violence by Islamist groups in Mindanao has left its mark in Davao City. On March 4, 2003, a bomb exploded in a waiting shelter just outside Davao International Airport, killing 22 people and injuring 143 others. Within days, an Abu Sayyaf Group commander claimed responsibility for the attack. On April 2, 2003, a bomb hit the Davao Sasa Wharf, the main dock for Davao City, killing 17 and injuring 56. Several alleged members of the Moro Islamic Liberation Front and the Abu Sayyaf Group were soon arrested.[18]

Southern Mindanao, which includes Davao City, has also seen a resurgence in extrajudicial killings by members of the armed forces and the police against leftist activists, journalists, and others deemed to be NPA supporters, part of a larger nationwide increase in such killings. As elsewhere in the Philippines, impunity for such crimes is the norm: rarely do the authorities prosecute members of the military or police for extrajudicial killings, and few cases result in arrests, even fewer in convictions.

Davao’s Mayor Rodrigo Duterte

Rodrigo Duterte was first elected mayor in 1988 on a campaign to reinstate peace and order in Davao City. Before running for office, Duterte had built his reputation as a city prosecutor by targeting military and rebel abuses with equal fervor. The son of a former provincial governor, Duterte said his father taught him that elected officials must serve the greater good no matter what it takes, like a father protecting and disciplining his family.[19]

Duterte’s rise as a prominent political figure coincided with a significant change in the dynamic between local officials and the police in the Philippines. As discussed in chapter X, two laws enacted in 1990-91 provided city mayors and provincial governors greater operational control over their police forces.

Under Duterte’s rule, crime rates in the city dropped to among the lowest in the country. According to the Davao City official website:

From a 3-digit crime rate per 10,000 people in 1985, Davao has reached an almost Utopian [sic] environment with a monthly crime volume of 0.8 cases per 10,000 persons from 1999 up to 2005. Digging through the records, it would reveal that about 90% of these cases reported are petty crimes that do not in any way threaten the over-all peace and order condition of the city.[20]

These descriptions attempt to conceal a rampant crime wave—namely, the murder of hundreds of alleged drug dealers, petty criminals, and street children.

More importantly, by averaging out years of statistics and omitting most recent years, they belie the city’s sharp upward trend in crime rates over the last decade. According to statistics from the police, between 1999 and 2008, the population in Davao City grew from 1.12 million to 1.44 million, or by 29 percent. Meanwhile, the number of annual crime incidents during this period rose from 975 to 3,391, or by 248 percent.[21] These numbers show that, contrary to the city government’s self-proclaimed success, its tough anti-crime campaign has failed to curve crime rates. An increasing number of death squad killings appears to have contributed to worsening crime rates in the city.

Local activists say death squad killings of alleged drug dealers, petty criminals, and street children in Davao City started sometime in the mid-1990s, during Duterte’s second term as mayor. The group that claimed to be responsible for the killings was called Suluguon sa Katawhan or “Servants of the People,” among other names, but soon the media in Davao City began referring to it the Davao Death Squad (DDS).[22]

By mid-1997, local media already had attributed more than 60 unsolved murders to the group, observing that the death squad had adopted the urban warfare tactics used in the 1980s by NPA “sparrow squad” hit teams. One source revealed that the death squad then had at least 10 members then, mostly former members of the NPA who had surrendered to the government.[23] The death squad grew dramatically since—one insider estimates the number of current members at about 500 (see chapter VIII).[24]

These killings have not been unpopular. According to a local human rights organization, fear and public frustration at “the arduous and ineffective judicial system” have made summary executions seem a “practical resort” to suppress crime in Davao City.[25]

Duterte, who has now been mayor for two decades, with a short interval as a congressman, has been given endearing nicknames by the media, such as “The Punisher,” “The Enforcer,” and “Dirty Harry” for his anti-crime campaign.[26] His policies have garnered public support in Davao City. It is thus perhaps no surprise that in recent years, reports of targeted killings of alleged drug dealers, petty criminals, and street children have emerged in the nearby cities of General Santos City, Digos City, and Tagum City in Mindanao as well as in Cebu City on the central island of Cebu.[27]

Targeted Killings in Mindanao and Beyond

While the focus of this report is on alleged death squad activities in Davao City, Human Rights Watch also conducted field research in Digos City and General Santos City. The research demonstrated that targeted killings in these cities partly started out of efforts by the Davao Death Squad to track down individuals who had left Davao City for the presumed safety of neighboring locales. But such targeted killings —that now involve locally-based killers— appears to reflect local government support and possible direct participation in politically popular if highly abusive anti-crime measures.

Human Rights Watch is also worried by the news of targeted killings of suspected criminals in cities outside of Mindanao. Among the cities of particular concern is Cebu City. The media in Cebu City treat the existence of a death squad in the city as a matter of fact, just as their counterparts in Davao City do. News archives from as early as 2003-2004 show articles on apparent targeted killings of suspected criminals.

In his response to a letter from Human Rights Watch, Cebu City Mayor Tomas R. Osmeña described a pattern of killings in Cebu similar to those in Davao City. In relation to 202 cases[28] registered in the city from December 2004 to September 2008, he noted:

The majority are categorized as “summary/vigilante Style of Killings” for the perpetrators are usually unknown, riding in motorcycles and wearing masks, bonnets or helmets. Information gathered during the investigation revealed that most of the victims are either having criminal records or ex-convicts, fraternity members or suspected to be involved in drug syndicate.[29]

Osmeña emphasized the efforts of law enforcement bodies to investigate and prosecute the cases, but did not provide details of these efforts beyond noting that “some cases were filed in court and now [are] pending ... resolution for the suspects [who] were identified and arrested.”[30]

V. Pattern of Killings

It is very hard to believe there is no death squad. There is a clear pattern, including the profile of victims, the choice of weapons, the use of motorcycles without license plates, and police failure in investigating the cases.

—Reah De La Cruz, reporter with Radyo Totoo, DXCP-CMN, General Santos City, July 18, 2008.

For over a decade, death squad killings have plagued Davao City on the southeastern coast of Mindanao.[31] In recent years, similar targeted killings have been reported in General Santos City, Digos City, and Tagum City in Mindanao and even Cebu City in the central island of Cebu. While the exact number of victims of such killings is hard to establish, available data suggest an alarming trend.

According to the Coalition Against Summary Execution (CASE) and the Tambayan Center for the Care of Abused Children (Tambayan), the number of death squad killings of alleged drug dealers, petty criminals, and street children in Davao City that started in the mid-1990s, has increased dramatically in recent years.

CASE documented 814 death squad killings in Davao City from August 19, 1998 to February 1, 2009, 116 of which happened in 2007, 124 in 2008, and 33 in January 2009 alone. CASE distinguished death squad killings from other killings based on several factors, including whether the victim received a previous warning, the profile of the victim, and the method of killing.[32]

A prominent local journalist who has researched extrajudicial killings in Davao City since 1999 told Human Rights Watch that in the course of a month from mid-June to mid-July 2008, he documented 60 killings and an additional eight attempted murders.[33] Data by CASE show a steadily upward trend in the number of killings in recent years from 65 in 2006 to 116 in 2007 and 124 in 2008.[34]

The reasons for the apparent rise in death squad killings are unclear, although the sharp increase in the number of illicit drug groups identified by the authorities in 2007 may offer one explanation, as many victims are alleged drug dealers or users (see chapter IV). Local activists offer other possible explanations: first, long-lasting impunity may have emboldened death squad killers, encouraging them to expand their operations, and second, the recent economic downturn may have led more poor people to resort to drug dealing and other criminal activities as it became difficult to find or keep stable jobs, giving death squad members more potential targets.[35]

However, the authorities in Davao and other cities, including Davao City Mayor Duterte, continue to deny the existence of any death squad. For example, Davao City police director, Sr. Supt. Ramon Apolinario, told local media that the DDS does not exist, adding that, “there is no community or city that will allow these groups to do things beyond legal means. As a law enforcement officer, I will stick to my mandate to observe due process, respect human rights of the suspect and the victim.”[36]

The city prosecutor of Davao, Raul D. Bendigo, wrote to Human Rights Watch that his office has “no hard evidence... on the existence of the so-called Davao Death Squad (DDS).”[37] These claims contradict consistent, detailed accounts by many individuals who have witnessed such killings, as well as information provided by “insiders,” as detailed below.

The killings documented by Human Rights Watch and by local human rights groups reveal a pattern in the perpetrators’ modus operandi, including commonalities in the profile of the individuals targeted for killings, advance warnings to victims that they would be targeted, the types of vehicles and weapons used by the assailants, and the locations of the killings.

Warnings and Intimidation

Most victims of targeted killings in Davao City, General Santos City, and Digos City receive warnings prior to the killings. The victims (or their families) first hear that their names are on a presumed list of people slated to be killed—the so-called “Order of Battle” or OB. Such lists have long been used by the Philippine military and police to target suspected NPA members and supporters.

As noted above, Davao City Mayor Rodrigo Duterte personally used to announce the names of suspected criminals on local TV or radio in 2001-02, and visited communities to warn delinquent youth and their parents. Local residents say Duterte stopped this practice several years ago, but the practice generated a widely held belief that there was a connection between those publicly named and supposed lists of potential targets.

For instance, prior to the killing of Conrad Dequina in October 2007, a barangay[38] official told Dequina’s family that his name was on a “list,” and advised that he leave town. According to a friend of Dequina’s:

Everybody knew whose names were on the list. I have not seen the list, but a barangay official had the names on a piece of paper, and carried it with him when he visited each house to inform the families.[39]

Accounts of insiders to DDS operations suggest that the police and barangay officials collect the names of drug users, people with a criminal record, and the like. Family members and others personally familiar with the victims of death squad killings consistently told Human Rights Watch that the victim had received clear threats or warnings to stop their criminal activities or other behavior—or face the consequences. Usually, the police or barangay officials delivered the warning, but neighbors and friends also passed on the message. In some cases, people were advised to leave the neighborhood, and a number of people fled after the warning. Others ignored the warnings or returned to the neighborhood after spending some time away, with dire consequences.[40]

For example, Cyrus Gitacaras, a man in his early 20s with a long criminal record, had been jailed as a suspect in a robbery case but was released in August 2007. Gitacaras told friends that a police officer had warned him that, “if he didn’t watch out, he might be killed on the street.”[41] Five days after his release, unidentified assailants murdered Gitacaras in Davao City.

According to Clarita Alia, whose four sons were murdered one after another between July 2001 and April 2007, a local policeman had warned her shortly before the first of her sons to be killed—18-year-old Richard—was stabbed to death. A couple of weeks before his murder, the police tried to arrest him, but his mother resisted, demanding a warrant. Clarita Alia said:

A policeman, who introduced himself as senior police officer [name withheld], told me, “Ok, you don’t want to give your child to me, then watch out because your sons will be killed, one by one!” I was really shocked he mentioned the other sons as they were just little kids then, but he was very angry because I was pushing him out.[42]

Just as the police officer threatened, Christopher Alia, 17, was murdered in October 2001, Bobby Alia, 14, in November 2003, and Fernando Alia, 15, in April 2007.

Locations

Most targeted killings documented by Human Rights Watch were committed in broad daylight in public places. Victims were targeted in front of their houses or in nearby streets, in bars and cafes, in jeepneys or tricycles[43], and in busy markets and shopping areas. In Davao City, death squad killings often occur in certain areas, such as a crowded market in Bankerohan, slums in the Agdao district, and along Bolton Street, a busy street lined with restaurants and cafes.

According to data collected by CASE, out of 814 killings committed in Davao City from August 19, 1998 to February 1, 2009, 57 percent of the incidents took place in areas under the jurisdiction of three police stations: the Santa Ana police station that covers Agdao and Chinatown (21 percent), the Talomo police station that covers communities south of Davao City (20 percent), and the San Pedro police station that covers Davao City’s downtown area including Bolton and Bankerohan (16 percent).[44]

Perpetrators

The perpetrators of targeted killings in Mindanao typically make greater efforts to conceal their weapons than their identity. They are often seen wearing jackets or buttoned-down shirts—apparently to conceal their weapons. Baseball caps are common. In a very small number of cases, eyewitnesses say that the gunmen wear “bonnets” (ski masks) or sunglasses. “Ramon,” a DDS insider, told Human Rights Watch that masks are rare, and usually worn when a hitman operates alone, driving a motorcycle himself.[45]

The presence of multiple eyewitnesses does not seem to restrain the perpetrators. For example, 15-year-old Adon Mandagit was shot dead at around 3 p.m. one day in July 2007 on Bolton Street in Davao City, near a popular Jollibee fast-food outlet.

His friend, who witnessed the killing, told Human Rights Watch:

There were many people in the street—after shooting Adon, the men waived their guns at the crowd, telling people to disperse. Women were shouting, some people hit the ground, and some were running away. I also got scared and hid behind a fruit stand. I could see everything from there.[46]

Witnesses can often clearly see the perpetrators. While perpetrators often wear baseball caps, as noted above, they do not try to hide their faces. In some cases they threaten bystanders before fleeing from the crime scene, waving their guns and telling them to keep quiet.

The UN special rapporteur on extrajudicial executions, Philip Alston, found the lack of effort by the perpetrators of such killings to disguise themselves noteworthy. He stated in his 2008 report:

One fact points very strongly to the officially-sanctioned character of these killings: No one involved covers his face. The men who warn mothers that their children will be the next to die unless they make themselves scarce turn up on doorsteps undisguised. The men who gun down or, and this is becoming more common, knife children in the streets almost never cover their faces.[47]

The gunmen usually arrive on motorcycles, in groups of two or three. In most reported cases, the motorcycles do not have license plates. The most commonly used motorcycles are XRM Honda or a larger, DT-type off-road motorcycle. In most of the cases documented by Human Rights Watch, the gunmen left on their motorcycles immediately after the attack and usually long before the police arrived.

Until 2006, perpetrators primarily used firearms—specifically, .45-caliber handguns, and, in some cases, .38-caliber or 9-mm handguns. The use of such firearms is a strong indicator that the murders were not perpetrated by common gang members. The .45-caliber handguns, for example, cost about 30,000 pesos (about US$625) each.[48] The vast majority of gang members cannot afford such expensive weapons, and mostly use knives or homemade pistols instead.

Several individuals familiar with DDS operations told Human Rights Watch that since 2006, some DDS members have started using knives instead of handguns, and have received training to this end. They say that the DDS now often favors knives because they are cheaper, attract less attention, and stab wounds make it easier for the police to claim that the victim was killed by gang members.[49]

Data compiled by CASE confirms the increasing use of knives in alleged death squad attacks. In 2006, 38 victims were shot and 26 were stabbed. In 2007, 56 were shot, and 59 were stabbed. In 2008, 73 were shot, while 50 others were stabbed. (In one case each in 2006, 2007 and 2008, the method of the killing was not given.) Although the use of knives decreased slightly in 2008, the data still show an overall upward trend in the use of knives. In 2005, for example, the number of victims killed with handguns reached 117, but only nine were killed with knives.[50]

VI. Map of Davao City

Map of areas in Davao City with reported death squad killings. ©2009 Human Rights Watch

VII. Victims

Targeted Victims

Most victims of death squad killings have been alleged drug dealers, petty criminals, and street children. Mistaken identity victims, bystanders, and family members or friends of intended targets have also been killed in death squad attacks. Data collected by CASE from August 19, 1998, to February 1, 2009 suggest that more than 90 percent of victims in Davao City are male.[51] Of the 28 killings Human Rights Watch documented, all but one were male.

In the majority of cases documented by Human Rights Watch, the victims were young men or youths who had been known in their community for involvement in small-scale drug dealing or petty crimes, such as stealing cell phones, and using drugs. Those targeted included gang members, alleged drug dealers, street children (some of whom are youth gang members), and low-income blue-collar workers such as informal car washers, jeepney and tricycle drivers, construction workers, and fishermen.

Of the 671 cases collected by CASE from the period between August 1998 and May 2008 in Davao City, 295 victims, or 44 percent, are believed to have been gang members or otherwise involved in criminal activities, such as using or dealing drugs, theft, or robbery.[52] CASE notes that 13 are believed to have been “mistaken identity” cases. At least two victims were killed by stray bullets, while one was killed shielding the victim. In 363 cases, or 54 percent, there was no information available on the victims’ involvement in crime.[53]

In a number of the cases documented by Human Rights Watch, police had arrested victims on suspicion of committing a crime and then released them when they did not have sufficient evidence to bring charges. Shortly after their release, these individuals were then shot or stabbed by apparent death squad members.

For example, on November 20, 2005, police arrested 22-year-old Rodolfo More, Jr. for trespassing and theft. They released him two days later, apparently because the evidence against him was not strong enough to prosecute. Soon after a relative picked him up from the police station, an unknown assailant stabbed him to death in a jeepney that was taking them home.[54]

The CASE data also suggest that about a third of the 814 victims in Davao City were young adults, ages 18 to 25, and at least 9 percent were children. In 2008 alone, out of 124 victims, 46 were young adults, and another 14 were children. Another 45 were 26 or older, while there was no information on the age of 20 others.[55] In the cases documented by Human Rights Watch, the majority of victims were teenagers or young men in their 20s.

Unintended Victims

In at least three cases documented by Human Rights Watch, the families believed that the victims were killed because they were mistaken for somebody who had been the intended target.

In one of the cases, 24-year-old Gabriel Sintasas from General Santos City was shot dead on March 19, 2008. His family told Human Rights Watch that the perpetrators seemed to be looking for Gabriel’s cousin, Frederick, an alleged drug dealer whom he resembled. Sintasas’ mother, who witnessed the killing, told Human Rights Watch:

I cried [to the gunman], “You idiot! This is not Eko [Frederick’s nickname]! You got the wrong man!” I knew that these people were looking for Frederick—they just mistook my son for him! The killer didn’t say anything in response, but he looked at Gabriel in shock, apparently realizing he made a mistake.[56]

After Gabriel’s murder, Frederick surrendered to the police, who told him he would have been “the next one” if he had not promptly surrendered.

On January 14, 2008, two gunmen in General Santos City shot dead Allen Conjorado, 23, and his brother Ronaldo, 15, inside a store owned by the brothers’ aunt. The aunt’s six-year-old daughter was also shot, but survived despite a head injury. A relative told Human Rights Watch that Allen was known in the neighborhood for selling drugs, but Ronaldo was not, and never received any warning prior to the killing.[57]

Death Squad Members

Another category of victims includes death squad members themselves—who may be targeted because they have acquired too much information about the squad’s operations, because they fail to perform their tasks, or because they are particularly exposed.

Other Victims

Local activists also say that an increasing number of people are being murdered because some death squad members have become “guns for hire” and are killing people in exchange for payment. A rights activist in Davao explained:

It costs only 5,000 pesos (about US$104) to hire an assassin. If you owe more than 5,000 pesos to someone, would you pay back, or would you hire a killer to take care of the lender? If you have a dispute, it’s so easy and cheap to eliminate the other.

Now the DDS moonlights, and work as “guns for hire” for pretty much anyone willing to pay the price. The targets used to be criminals, but they now include non-criminals. The DDS is expanding their business. The creation of the DDS has made killing a very profitable business. You are not safe, even if you did not commit any crime. You can still become a victim.[58]

VIII. Targeted Killings

The following cases, involving 28 targeted killings, were documented by Human Rights Watch during our research in Davao City, General Santos City, and Digos City in July 2008.

Davao City

Jaypee Larosa, 20, killed on July 17, 2008

Jaypee Larosa, 20, had no criminal record and lived in Lanang, a quiet residential neighborhood in Davao.[59]

At around 6 p.m. on July 17, 2008, Larosa left home, saying he was going to a neighborhood Internet cafe. A relative told Human Rights Watch that at around 7 p.m. the family heard six gunshots. A neighbor then rushed to their house and said that the “twin” had been shot, which the family immediately realized meant Jaypee, as he had a twin brother.

Family members rushed to the Internet cafe, and found Larosa with several bullet wounds in front of the cafe. They took him to a hospital, but he was declared dead on arrival.

According to family members, eyewitnesses told them that Larosa had been shot by three men wearing black and dark blue jackets who arrived on a Honda Wave motorcycle. After they shot him, one of them removed the baseball cap Larosa was wearing, and said, “Son of a bitch. This is not the one,” and they immediately left the scene. The police recovered an empty cartridge from a 9-mm handgun.

The family believes that Larosa was mistaken for someone else.

Shortly before the killing, the family had heard that some twin brothers had committed a robbery in the neighborhood where they used to live. A police officer had mentioned to members of the community the names of the Larosa brothers as potential suspects.

Convinced that the Larosa brothers could not have been involved in the robbery, the family confronted the police officer. On July 15, the police officer filed a libel complaint against the family. On July 16, the Larosa family filed a counter-complaint. The following day, Larosa was killed.[60]

Adon Mandagit, 15, killed in July 2007

Adon Mandagit, 15, used to live in Calinan, south of Davao City, with his family. Several years before he was killed, local police arrested Adon and beat him once for sniffing “rugby” (an industrial solvent commonly used by Filipino youth as an intoxicant) and for an alleged theft. “Ricardo,” a close friend of the Mandagit family, told Human Rights Watch that Adon’s mother then filed a complaint against a Calinan Police Precinct policeman for mistreating her son. As a result, the policeman was removed from the station and the police paid damages to the Mandagit family.[61]

According to Ricardo, after the incident, the Calinan police warned Adon’s mother that unless her son changed his behavior, “Something may happen to him.” The mother then asked Ricardo to take her son to Davao City, and Adon moved there in early 2007.

In Davao City, Adon started working with Ricardo as an informal car washer in the Bolton area of the city.

Ricardo told Human Rights Watch that they were always together, and he tried to keep an eye on Adon, fearing for his safety. Adon’s mother told him that some “men on motorcycles” were looking for Adon in Calinan, coming to the house, and asking the mother for his whereabouts.

In July 2007, Adon was shot dead in front of Ricardo. Ricardo told Human Rights Watch:

It was around 3 p.m. Adon and I were on Bolton street, washing cars near a Jollibee restaurant. I went to buy cigarettes but the moment I left Adon, I heard gunshots and immediately turned around. I saw two men firing at Adon. One of them, short and heavy-built, was two or three meters away from Adon. I believe he fired the first shot. Adon stumbled, and another, taller man finished him off with another two gunshots.

There were many people in the street—after shooting Adon, the men waived their guns at the crowd, telling people to disperse. Women were shouting, some people hit the ground, and some were running away. I also got scared and hid behind a fruit stand. I could see everything from there.[62]

According to Ricardo, the short man was in jeans and black jacket, and the tall one was wearing jeans, an off-white polo shirt, and a baseball cap. After shooting Adon, the men jumped on a waiting motorcycle and took off. Ricardo noticed that the motorcycle was a DT sports model, and the driver had long hair. The gunmen were armed with .45 caliber handguns.[63]

After the gunmen left, Ricardo approached Adon. The boy was already dead—two wounds were visible in his head (one in his forehead and a second in the back of his head), and another bullet wound in the neck. Ricardo then quickly left the scene, fearing for his own life—Adon’s killing was not the first one in the area and he was afraid he might be targeted as well.

Ricardo believes that Adon might also have been killed because a month before his shooting he had witnessed the murder of another car washer in the same area. As a witness to the killing, Adon was then questioned by the police. He also had given an interview about the murder to a local TV channel.

Rolando Jimenes, 50, killed on June 15, 2008

Rolando Jimenes was a retired member of the CAFGU militia and lived in Davao City. In 2003, police arrested him for murder and he served time in prison until July 2007. According to a relative, shortly after his release, Rolando joined the Davao Death Squad and took part in death squad raids along with other members. He did not try to hide his affiliation with the death squad from his family.

On June 15, 2008, Jimenes was drinking with a friend in a bar. An individual present at the bar later told a member of Jimenes’ family that a death squad member, who apparently knew Jimenes, arrived on a motorcycle, came into the bar and told the customers to leave. He then approached Jimenes and shot him several times, first in the side, then in the neck, twice in the head—in the middle of the forehead and in the right cheek—and then in the chest.[64]

After the shooting, the gunman ran out of the bar where an accomplice waited on a motorcycle, and they sped off.

The police arrived at the scene about 30 minutes after the killing and conducted a basic examination of the crime scene, fingerprinting the victim and collecting bullet cartridges. The family did not file a case[65] because, according to the witness interviewed by Human Rights Watch, “They knew about his job and thought it was useless to file.” The witness was not aware of any action taken by the police to further investigate the case.

Nerito Calimbo, 42, killed on May 22, 2008; Jocelyn Calimbo, 44, killed on May 22, 2008; Aaron Sumitso, 26, killed on May 22, 2008

Nerito Calimbo, 42, was a self-employed businessman working in the mining industry, and a former New People’s Army fighter who surrendered to the government and was granted amnesty after serving two months in prison. After his surrender, he held different jobs, including as a bodyguard. Jocelyn Calimbo, 44, Nerito’s wife, was a nurse.[66]

A relative of the Calimbos told Human Rights Watch that on May 21, 2008, dozens of members of the Criminal Investigation and Detection Group (CIDG) from the Davao City police, armed with .45-caliber handguns and wearing bullet-proof vests, entered the Calimbo residence. They searched the house without a warrant.

The officers took Nerito Calimbo to their office for questioning. They accused him of kidnapping and murder, and of being a leader of a well-known gang. The next day, May 22, he was released on bail.

Calimbo’s wife, Jocelyn, and his brother-in-law, Aaron Sumitso, picked him up at the barracks of the Davao City Police Office. They got into a taxi, which soon stopped because of traffic. Two men on a motorcycle approached them, shot the Calimbos and Aaron Sumitso, and fled from the scene. The taxi driver, who was unharmed, drove them to a hospital, but all three were declared dead on arrival.

The Calimbo family decided not to pursue the case with the police, fearing retribution.

In late May 2008, Chief Inspector Antonio Rivera, chief of the Investigation Division and Management Section of the Davao City police, told journalists that they had released a composite sketch of one of the suspects. Senior Superintendent Jaime Morente reportedly said the San Pedro police were investigating the case, and looking at all possible motives behind the killing. Local media reported that Nerito Calimbo was a suspected leader of a well-known gang called the Chigo Robbery Group.[67]

Before Calimbo was released, CIDG-Southern Mindanao chief Jose Jorge Corpuz allegedly had warned the victim that he was being targeted for assassination, but later clarified that his warning was based on the presumption that Calimbo's enemies would take advantage of his release from CIDG detention.[68]

At this writing in February 2009, the police had not reported the arrest of any suspect in the case.

Conrad Dequina, early 20s, killed on October 10, 2007

Conrad Dequina, in his early 20s, lived in Davao City. According to a friend, he was known to sniff rugby and was a suspect in a murder case. Prior to the killing, a barangay official had warned Dequina’s family that his name was “on the list,” and advised that he leave town.[69]

At around 10 p.m. on October 10, 2007, Dequina was hanging out with friends in his neighborhood, when neighbors heard gunshots. Dequina’s friend, who witnessed the killing, told Human Rights Watch that he saw three men wearing baseball caps and denim jackets.

He said that the assailants shot Dequina six times with what appeared to be .45-caliber handguns. They also shot and killed another man who was standing next to Dequina—possibly by accident.

The friend said that after the shooting, the gunmen drove around for some time, as if looking for someone else, but left just before the police arrived. He told Human Rights Watch:

Nobody said anything, because they were all afraid. The police asked who the victim was, and laughed as if they liked what they saw. They didn’t talk to any of the witnesses. And then they left, leaving behind the body and empty shells. They didn’t do anything. They didn’t seem to care about any evidence.

The friend does not believe the police followed up on the case.

With regard to the other victim, the friend said:

We knew the second guy was a mistake, because his name was not on the list. Everybody knew whose names were on the list. I have not seen the list, but a barangay official had the names on a piece of paper, and carried it when he visited each house to inform the families.

Dequina’s friend said that three other friends of his were killed in the neighborhood between June and July 2008. He said that they were gang members and all had received warnings before the killings. All three were killed in the same manner as Dequina, and he knew of no police follow-up on any of the cases.

Jumael Maunte, 24, killed in August 2007; Cyrus Gitacaras, age unknown, killed in August 2007

On August 12, 2007, Jumael Maunte and Cyrus Gitacaras went missing. On August 16, Maunte’s family saw on the TV news that two bodies had been found in Mawab, Davao del Norte, about 90 kilometers northeast of Davao City. Maunte’s mother went to the funeral parlor and identified one of the bodies as her son’s. The body bore many bruises, a large blackened wound in the head, and three gunshot wounds in the chest. The wrists and ankles were tied with thin metal wire. The family, who are Muslims, immediately buried the body.[70]

The second body belonged to Cyrus Gitacaras, a friend of Maunte’s. The body, which had been found beside a highway by a jeepney driver, had gunshot wounds to the right eye and the chest, as well as bruises on the head. The wrists and ankles were tied.

According to Maunte’s relative, Gitacaras had a long history of trouble with the law, including theft, drug use, and robbery. He was a suspect in a robbery case, and the authorities had released him from a city jail only five days before he went missing. Neighbors and barangay officials had told him his name was on a “list.” Gitacaras told his friends that a police officer had warned him to watch out or he might be “killed on the street.”

Maunte was a drug user. To the relative’s knowledge, he had never received any warnings that his name was on a list or that his life was in danger. Fearing for his safety, his family told him to avoid Gitacaras, but Maunte would not listen, as they were close friends.

After the discovery of the bodies, Maunte’s family located an individual who had been with Maunte and Gitacaras at the time of their abduction, but had managed to escape. He told the family that on August 12, the three of them were in Butuan City, which is about 220 kilometers northeast of Davao City, when a group of armed men approached them and took the two away.

The police never contacted Maunte’s family about the case. According to Maunte’s relative, when Maunte’s mother asked the police if they had any leads in the case, they said they could not pursue the case because they did not know who was responsible for the killing. The survivor refused to make a statement to the police, as he was scared for his life.

Danilo Macasero, early 30s, killed in late May 2007

Danilo Macasero was a known drug dealer. According to a neighbor, a barangay official once told Macasero that his name was on the “list.” Neighbors tried to convince him to stop dealing drugs, but he continued.[71]

Macasero’s neighbor, who witnessed the killing, told Human Rights Watch that in late May 2007, four men wearing baseball caps and jackets arrived in Macasero’s neighborhood on two XRM Honda motorcycles. The men appeared to be staking another known drug dealer’s house, and at around 8 p.m., Macasero walked past them.

One of the men then followed Macasero and stabbed him without warning. Macasero tried to run away, but another assailant caught up with him and stabbed him again. The men stabbed him 12 times in total.

The men then pulled out handguns that, according to Macasero’s neighbor, appeared to be .38-caliber silver pistols, and pointed them to those gathered around. Macasero’s neighbor said that one of them said, “Don’t do anything. You are not part of this.” Another one then kicked Macasero’s face as he lay on the ground, and said, “Don’t follow this guy. He is an addict.”

Macasero’s family took him to a hospital, but he was declared dead on arrival.

Richard Alia, 18, killed on July 21, 2001; Christopher Alia, 17, killed on October 20, 2001; Bobby Alia, 14, killed on November 3, 2003; Fernando Alia, 15, killed on April 13, 2007

From July 2001 to April 2007, the four Alia brothers from the Bankerohan area in Davao City fell victim to apparent death squad killings—they were stabbed to death one after another, by unidentified perpetrators.[72]

Richard Alia, 18, was a member of the “Notoryus” gang in Bankerohan and police had arrested him several times for petty crimes. In 2000, he survived a murder attempt when an unidentified perpetrator shot at him.

In early July 2001, the police tried to arrest him again, but his mother resisted. She told Human Rights Watch:

The police from San Pedro police station came to our house to pick him up for an alleged rape, but they didn’t have a warrant. I asked for one, but they didn’t have it and said they didn’t need it. I protested, and then a policeman, who introduced himself as Senior Police Officer [name withheld], told me, “Ok, you don’t want to give your child to me, then watch out because your sons will be killed, one by one!” I was really shocked he mentioned the other sons as they were just little kids then, but he was very angry because I was pushing him out.

On July 17, 2001, at around 4 p.m., Richard left his house to have a drink with a friend. Several hours later, a neighbor, who witnessed the killing, informed his mother that Richard had been stabbed to death. According to Clarita Alia, when she arrived at the scene, Richard was already dead, having sustained a fatal wound on his right side. She was unsure whether police ever opened an investigation into the killing, and she did not try to pursue the case, fearing for the safety of her other children.

Three months later, on October 20, 2001, Richard’s younger brother, Christopher, 17, was also stabbed to death. Clarita Alia said:

When somebody informed me that Christopher had been stabbed, I was startled, shocked—I realized they had started killing my kids one by one. When I got to the market where the killing happened, I saw Christopher being held by his older brother, Arnold. I think that Arnold was probably the target as he is my oldest son. People at the market said that two men were following Arnold that morning, but then apparently lost him and targeted Christopher instead. Christopher suffered one fatal wound in the chest, and had some smaller wounds on his arms—apparently, he was trying to protect himself.

When the police arrived at the scene, they didn’t try to find any witnesses, they just kept asking me, “What happened? Who killed your son?” I was hysterical, and kept telling them, “Why are you asking me? You are the policemen—ask witnesses around here!”

After Christopher’s killing, his mother filed a case with the Commission on Human Rights, but she was not aware of any action taken by the commission. Human Rights Watch sent a letter to the commission with inquiries on the case of the Alia brothers along with some other murder victims in September 2008, and resent the letter a month later, but received no response.

On November 3, 2003, Bobby Alia, 14, was stabbed to death in the Bankerohan market, the same place where Christopher had been killed. Shortly before his killing, police arrested him for allegedly stealing a cell phone. His mother managed to secure his release—she said Bobby complained about police torture as they tried to obtain a confession from him. Two days after he was released, Bobby was stabbed in the back with a butcher’s knife.

This time, witnesses to the incident said they could identify the perpetrator, a known local hitman, allegedly with close ties to the police. Clarita Alia decided not to share this information with the police. “I didn’t tell them,” she said, “Because this person is very close to the police, and the police know full well who the killers of my children were.” She did not know whether the police had investigated Bobby’s killing.

Fearing for the life of her other son, Fernando Alia, Clarita Alia tried to keep him away from Davao City. Fernando attended a boarding school away from Davao City, but, according to Clarita Alia, unidentified people kept approaching Fernando there, saying “He would be next.” In 2006, Fernando returned to Davao, and soon thereafter was arrested for the first time, for sniffing rugby. He survived one murder attempt in November 2006, but unidentified assailants stabbed him to death on April 13, 2007. His mother told Human Rights Watch:

I always kept him at home, never allowed him to go out alone. But that night I was so tired, I went to sleep early and told my daughter to keep an eye on Fernando. But apparently, he told her that he would just go to a neighbor’s house, and she allowed him to leave. Next thing we knew was that he had been stabbed in the morning, by two perpetrators, on a bridge near the market. He did not die on the spot—an ambulance took him to the hospital, and when my daughter got there, the doctors were trying to revive him. But they did not succeed, and several hours later he was pronounced dead.

Clarita Alia said that two minors who allegedly witnessed the killing from a distance were too scared to testify. As with the three other killings, the mother had no information from the police about the progress in the investigation, and to date none of the perpetrators have been arrested.

Jesus Ormido, 18, killed on October 10, 2004; Jay-ar Omido, 20, killed on June 1, 2006

Jesus Ormido, 18, was a tricycle dispatcher in Davao City. In the past, he had been jailed for several months for sniffing rugby and stealing cell phones. A barangay official once told Jesus’ grandmother that Jesus should be careful, adding that he would not want anything to happen to ”any of the family members.”[73]

At around 4 p.m. on October 5, 2004, two men wearing black ski masks and black jackets approached Jesus Ormido at the tricycle terminal where he worked. Without warning, they stabbed him once and shot him four times. According to a relative (who had talked to witnesses), the men rode a black-and-white DT-type Yamaha motorcycle. Jesus’ relative said the witnesses heard them saying, “You will not be the last. We will get another in your family.” Police officers were in the vicinity, but they did not chase the assailants. Scene of Crime Operations (SOCO) officers arrived and collected spent bullet casings. The police later told the family that they could not file a case because no witness could describe the gunmen.

Jesus Ormido did not die on the spot, and the police took him to a hospital. His condition stabilized, but five days later, as his family was waiting outside his ward, they were suddenly called in. By the time they arrived at the ward, Jesus was bleeding profusely from his earlier wound. The doctors performed CPR, but were not able to save him.

A patient on the adjacent bed told the family that a big man had come in, wearing a black shirt and a white doctor’s gown with its hem stuck on his waistband on the back side, “as if he put it on hastily.” He squeezed Jesus’ wound until it bled. Jesus kicked around, but he could not yell, because a tube was blocking his airway. After some time, he was still, and did not move again. The police who arrived at the hospital concluded it was murder, but according to the relative, did not follow up with an investigation.

Jesus’ younger brother, Jay-ar Ormido, 20, also worked as a tricycle dispatcher. On June 1, 2006, Jay-ar went to a neighbor’s wake where he met an acquaintance who was a police officer. Jay-ar stayed overnight, but as he was leaving the next morning, the police officer and another man driving a green DT-type motorcycle approached him.

According to Jesus’ relative, an eyewitness said the policeman shot Jay-ar once, without saying anything. Jay-ar fell on the ground, tried to get up and run, but could not. The policeman then shot Jay-ar, who was lying on the ground, five more times. The witness said that the policeman and the other man drove away aboard a motorcycle.

SOCO officers recovered spent bullet casings from the crime scene, examined the wounds and talked to witnesses. They also took Jay-ar’s body to a funeral parlor.

After learning from a witness that the police officer had been on the motorcycle with the other assailant, Jay-ar’s family filed a complaint against the police officer, only to discover that he was no longer in service and had left Davao City. The family was unaware of any further action being taken in the case.

Rodolfo More, Jr., 22, killed on November 20, 2005

Rodolfo More, Jr. lived in a neighborhood in the Agdao district in Davao City known as Barrio Patay (“Place of Death”), because of the numerous killings that have occurred there over many years.[74]

According to a relative, More’s family heard that he had been “on the list.” On November 20, 2005, More was arrested for trespassing and theft—it was his third arrest. On the afternoon of November 22, a relative picked him up at the Santa Ana police station in Davao. They got in a jeepney a few meters away from the station. The relative sat with her back against him, and turned around when she suddenly heard his scream. Rodolfo was lying on the bench of the jeepney. More had been stabbed in the chest. She saw a man jump out and walk away, as if nothing had happened. The driver seemed too shocked to stop the vehicle, and since More’s relative was also in shock, and didn’t know what to do, she just asked the driver to take them home.

When they arrived at More’s home, his father took him to a hospital, where he was declared dead on arrival. To the family’s knowledge, the police did not investigate the case. The More family did not go to the police as they were concerned they would have to pay to file a complaint and could not afford it.

Kim “Keno” Garcia, 20, killed on November 11, 2005

Kim “Keno” Garcia had been a gang member in Davao City since he was 13-years-old. He was jailed several times for theft, rugby sniffing, and other petty crimes. According to Garcia’s friend, who learned of the details of the killing from an eyewitness, on November 11, 2005, Garcia was waiting for a friend in front of a convenience store when two men on a motorcycle approached him and stabbed him to death. Garcia sustained 14 stab wounds. Prior to the killing, he had once left the city after receiving an anonymous warning. The friend told Human Rights Watch:

In 2004, he received a letter warning him that unless he left, he would be killed. He came back in June 2005 because he wanted to be with his gang. He was handed over to the police by a village watchman shortly after his return. The police asked, “It’s you again? Weren’t you warned already and haven’t you left the place?!”

That’s why we concluded that there was some cooperation between the DDS and the police. Of course, it wasn’t the police that warned him, but they knew about it very well.[75]

Garcia’s friend did not know whether the police ever opened an investigation into the killing.

Romeo Jaca, 17, killed on May 26, 2003

Romeo Jaca, 17, was a leader of a youth gang with several dozen members. The gang members drank and used drugs together, were involved in theft and prostitution, and fought with rival youth gangs. A few months before Jaca’s killing, his mother heard that the barangay office was collecting the names of gang members. She tried to convince him and his older brother to leave the neighborhood.[76]

According to Romeo’s relative who learned the circumstances of the killing from eyewitnesses, late at night on May 26, 2003, a neighbor told Jaca that an official with the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency wanted to see him. Jaca left home to meet the official, walked past a small alley, and stopped in the middle of the street when he saw someone standing on the other side. He then turned and ran back into the alley but the assailant followed, shooting him while three other men cornered him. He was shot three times, in the head, back, and leg. The gunman and three others fled immediately. Two of them rode in a white van without a license plate. The other two drove a DT-type off-road motorcycle with no license plate.

The police later told the family the cause of death was a gunshot wound in the head inflicted by a .45-caliber handgun. But, according to Jaca’s relative, the family did not file a case and the police did not follow up with any further investigation. The relative said:

A lot of killings happen, but nothing gets resolved. Nobody gets convicted. There is no point in filing a case [complaint]. If we filed a case, we are afraid other men in the family would be targeted next.

General Santos City

Danilo Auges, 38, killed on May 26, 2008; Aldrin Alba, 22, killed on June 10, 2008; Dodon Borga, 17, killed in July 2008; “Kawalyan,” 20, killed in July 2008

Danilo Auges, a construction worker in General Santos City, was a drug user who used to hang out with local drug dealers. His relatives said that he had been arrested once for stealing a cell phone, but released once the phone was returned to the owner. They said that he did not deal drugs himself, although the media tried to portray him this way after the killing.[77]

On May 26, 2008, Auges was grilling fish in the yard of his house with a friend and a nephew. At around 4:30 p.m., a relative of Auges’ came home. She told Human Rights Watch:

I went into the house, and when I came back into the yard some time later, I saw Danilo face-to-face with a gunman. The gunman had dark skin and long hair, and was wearing basketball shorts and a loose T-shirt. I saw his companion on a motorcycle parked a couple of meters away—it was a black XRM motorcycle, and the driver was wearing a military hat.

The gunman, who had a pistol in his hand, was asking Danilo about some other man, Jon-Jon. I came forward and said that there was no one with such name in our block. But the gunman didn’t leave. Danilo apparently sensed that something was wrong and tried to get inside the house, but at that moment the gunman shot him. He first shot him in the back, and then, when Danilo fell on the ground, the gunman kneeled next to him and shot him twice more, in the head, behind both ears.

I was in shock, and just kept shouting, “Dan! Dan! Dan!”

The gunman then jumped on the motorcycle that pulled by and they drove away.

According to the relatives, the police did not arrive until about 30 minutes after the killing even though the police station is located very close to the house and neighbors immediately reported the incident to them. Auges’ relatives provided the police with a description of the gunman. A Scene of the Crime Operatives team took pictures of the crime scene, collected Auges’ fingerprints, and retrieved one of the cartridges, telling the family that the bullet was from a .45 caliber handgun.

At the time they spoke to Human Rights Watch, the relatives were not aware of any progress in the investigation and were scared to inquire with the police, fearing retribution.

Shortly after Auges’ killing, at least three of his close acquaintances also became victims of apparent death squad killings.

According to Auges’ relatives, shortly after her brother’s killing, the family of his friend Aldrin Alba received a text message on a cell phone, which read, “The person who receives this message will be the next one to be killed after Danilo.”

Aldrin Alba was killed on June 10, 2008. Three armed men arrived at Alba’s house on a motorcycle. They first shot him in the legs and then shot at him four more times as he was trying to run out to the street.

Two other friends of Auges’, Dodon Borga and “Kawalyan,” were shot dead in a similar manner in the first week of July 2008. Auges’ relatives told Human Rights Watch that after her brother and Alba were killed, the two men fled the town and went into hiding. However, their families later said that armed men on motorcycles found Borga and Kawalyan and shot them both dead.