Kosovo: Poisoned by Lead

A Health and Human Rights Crisis in Mitrovica's Roma Camps

I. Summary

A decade ago, the Roma living in the Mitrovica region in northern Kosovo comprised one of the most vibrant and distinctive communities in the former Yugoslavia. Their neighborhood, known as the Roma Mahalla, comprised around 750 houses, with an estimated 8,000 inhabitants. In the wake of the 1999 conflict, during which ethnic Albanians had suffered mass expulsions and killings at the hands of Serbian forces, there was a wave of retaliatory violence against minorities at the start of international rule in Kosovo in June 1999. The targets of this violence included the Roma, Ashkali, and Egyptians (RAE), whom the Albanian perpetrators saw as "Serb collaborators."

Fearing repression, the Roma Mahalla dwellers fled their homes, crossing the Ibar River to the north Mitrovica region, which remained under Serb control. Albanian crowds subsequently entered the Mahalla, looting the houses and then burning the whole settlement to the ground. The forces of the international peacekeepers (KFOR) who were stationed in Mitrovica at the time did not intervene to stop the pillage and arson.

The Office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) provided assistance to the Roma internally displaced persons (IDPs), distributing food and organizing makeshift camps in Cesmin Lug and Zitkovac, to which many of the IDPs moved in October 1999. These camps were supposed to be a temporary solution until Roma houses in the Mahalla were reconstructed. Other IDPs spontaneously occupied abandoned army barracks at Kablare (next to the Cesmin Lug camp) and Leposavic, a town 45 kilometers from Mitrovica.

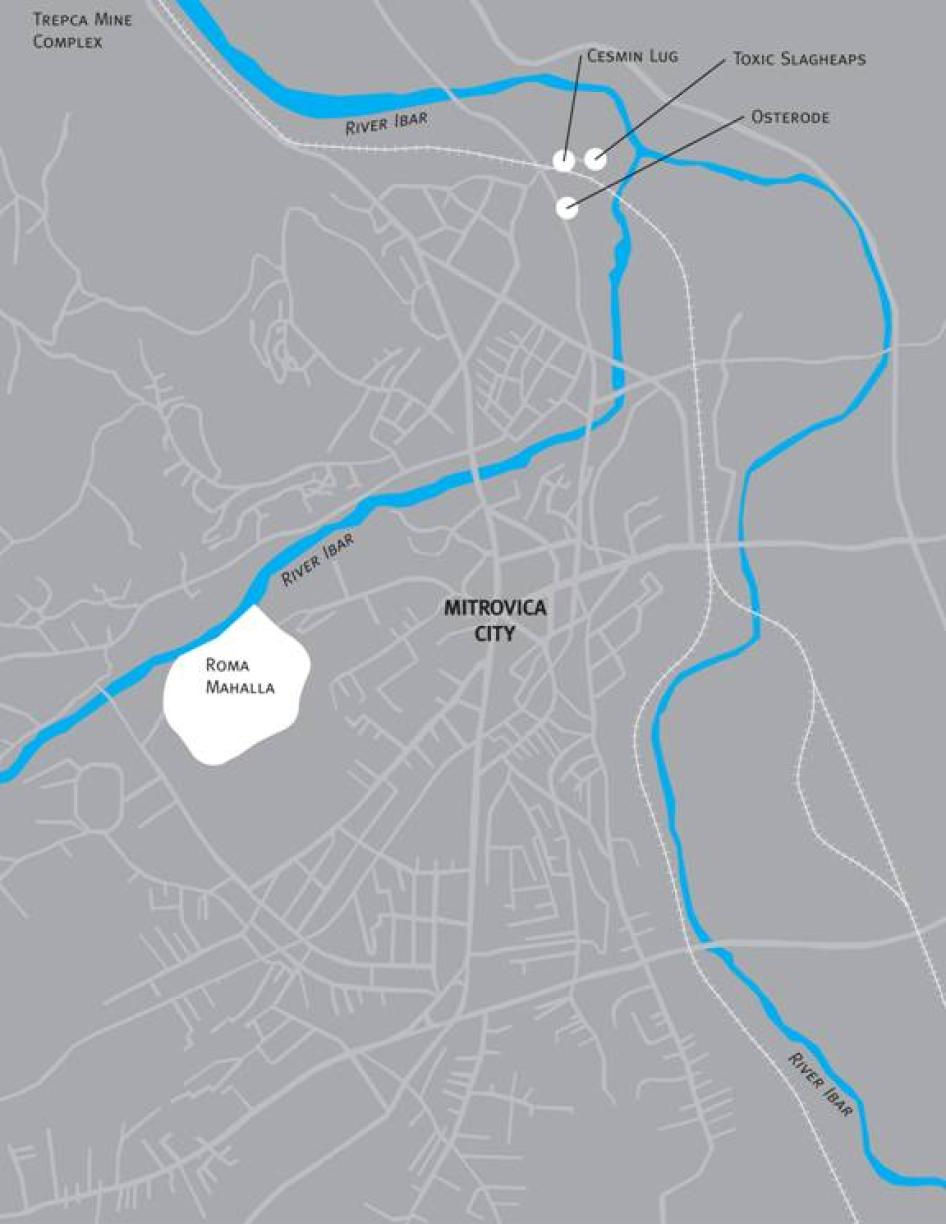

With the exception of Leposavic, all the IDP camps created were in the vicinity of the Trepca complex, a mine for lead and other heavy metals. The entire region has for years been known for environmental pollution caused by the mining industry. Cesmin Lug and Kablare were located right next to toxic slag heaps of lead-contaminated soil.

The living conditions in the camps were very difficult from the beginning. IDPs lived in small shacks made of wood, in wooden barracks, or in metal containers. They had no access to running water, only a few hours of electricity per day, a poor diet, and could not maintain adequate personal hygiene. At the same time, the proximity of the camps to Trepca and especially the slag heaps of leaded soil exposed them to lead contamination by air, water, and soil (especially when the wind blew from the direction of the slag heaps, or when children played in that area and brought contaminated dirt back into their houses).

The proximity of Trepca and the poor living conditions in IDP camps indicated a clear likelihood of lead exposure. UNMIK, the UN body that was the effective civil authority in Kosovo from 1999 to 2008, commissioned a report in November 2000 to provide recommendations on how to assess risk and means of mitigation. The report recommended comprehensive epidemiological studies, periodic environmental sampling, and robust medical monitoring and medical treatment for those in need. However, it concluded that the costs of any such strategy exceeded the financial capacities of UNMIK. During the period 2000-04, no further steps were taken to address the issue of contamination in the region.

In 2004 information about the deteriorating health of the IDPs in the camps began to emerge from local and international Roma rights activists. They started to bring to light cases of children with black gums, and with lead-related symptoms such as anxiety, concentration and learning difficulties, headaches, disorientation, convulsions, and high blood pressure.

Prompted by the alarming NGO reports, the World Health Organization (WHO) conducted an assessment of the situation in the camps in the summer of 2004, producing an internal report to UNMIK on how to manage the risks and recommending finding a more suitable location for the IDPs and to close the existing camps. WHO also initiated blood testing on children from the camps, which demonstrated unacceptably high lead levels.

In April 2005 UNMIK established a task force (comprising UNHCR, WHO, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe Mission in Kosovo, and the NATO-led KFOR peacekeeping force) to develop a framework for the relocation of IDPs from the camps. The task force came up with the idea of moving the IDPs temporarily to the KFOR-donated barracks in its former military camp known as Osterode, before returning them to the reconstructed Roma Mahalla. The Osterode camp was determined to be more "lead safe," despite also being located next to the toxic slag heaps.

While offering better living conditions than the other camps, this solution did not move the IDPs from the center of contamination. In the spring of 2006 the inhabitants of Zitkovac and Kablare camps moved to Osterode, but the people in Cesmin Lug largely refused to relocate there, not seeing the point of moving to a location just 150 meters away.

Simultaneously, international donors funded the reconstruction of individual houses and blocks of flats on the site of the Roma Mahalla, which resulted in a group return of 450 IDPs from all the camps (as well as some other locations in Serbia and Montenegro), facilitated by the task force in June 2007. After an initial period of receiving assistance, the returnees found themselves unable to support their families. Most were not given assistance by the Kosovo welfare system, but they had to de-register in the north and lost access to the Serbian assistance they had been receiving. This, coupled with difficulties with finding jobs in south Mitrovica, made the returnees disillusioned with living in the Mahalla, which in turn discouraged other potential returnees. Many Mahalla returnees subsequently left, moving either back to the north or to various locations in Serbia or Western Europe, and leaving behind the reconstructed houses, some of which were subsequently looted.

During the period 2004-06 at least three rounds of testing of blood samples from children, (usually around 50 children each time) were conducted under WHO's auspices. The test results are not publicly available, but according to WHO lead levels decreased over that period, especially for people in the Mahalla and the Osterode camp. The Roma continued to complain about lack of transparency in the process, an allegation denied by all international actors involved in it. In 2006 WHO organized two rounds of oral chelation therapy (medical treatment aiming to bind and remove heavy metals) on around 40 children from Osterode.

In 2007 UNMIK decided to discontinue further blood testing and therapy. Reportedly, WHO recommended this as it was under the impression that all camps' inhabitants would be moved back to the Mahalla, where the contamination level is lower.

Roma leaders requested the Serbian Public Health Institute in Mitrovica (which had previously been conducting the testing under the auspices of WHO) to continue monitoring children's lead levels, and the institute carried out two more rounds of blood testing, most recently in April 2008. The results showed continuing high levels of lead contamination (lower than before, but still exceeding acceptable or moderate levels) in children coming from all the camps as well as the Mahalla.

Efforts to seek justice and compensation for health damage caused by prolonged exposure to lead contamination have yet to produce results. A criminal complaint filed with the Kosovo prosecutor in September 2005 against unknown perpetrators alleging criminal neglect resulting in prolonged exposure to a highly toxic environment did not result in an investigation. A complaint filed by the international NGO the European Roma Rights Center (ERRC) in February 2006 with the European Court of Human Rights on behalf of Roma IDPs was ruled inadmissible on the ground that the court lacked jurisdiction over UNMIK-administered Kosovo. A claim filed in July 2008 with the Human Rights Advisory Panel in Kosovo (a semi-independent body created by UNMIK to deal with human rights complaints against it) was deemed admissible on June 5, 2009, but at this writing the Panel had yet to rule on the merits.

In May 2008 UNMIK handed over the management of the Cesmin Lug and Osterode camps to the Kosovo Ministry of Communities and Returns, which hired and funded a local NGO to run the camps.

The years of continuous failure of UNMIK and its international partners to find a durable solution for the inhabitants of the camps constitute multiple human rights violations, including of the right to life; the prohibition of cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment; the right to health, including medical treatment; the right to a healthy environment; and the right to adequate housing. This failure is the subject of growing international criticism, including from UN human rights bodies and experts.

To remedy these violations, it is vital that UNMIK and its international partners work with authorities in Kosovo, including in Serb-controlled municipalities, and with the leaders of the camps to urgently close the remaining camps, and move their residents to an acceptable location. It is also crucial that medical monitoring and treatment for all IDPs resume without delay. Roma IDPs should also be compensated for the health and other damages incurred.

In June 2009 displaced Roma will have spent a decade in lead-contaminated camps. The complex political reality in Kosovo and especially in the tense Mitrovica region does not change the fact that during a decade of international presence in Kosovo very little has been done to address appalling conditions in the Roma camps and especially the issue of lead contamination. For children and others living in the camps the consequences have been disastrous-not just ill-health but possible irreversible intellectual impairment. The Mitrovica Roma cannot afford to wait any longer.

Methodology

A Human Rights Watch researcher travelled to Kosovo in late November and the beginning of December 2008 to document the current situation in the Roma IDP camps of Cesmin Lug, Osterode, and Leposavic, as well as the return site in the Roma Mahalla.

Human Rights Watch interviewed the most prominent leaders in each of the camps, six other RAE community activists, and 40 members of the RAE community living there, 10 of whom were women. Most of the persons interviewed were ethnic Roma, while a few interlocutors described themselves as Ashkali (see Chapter IV, "Background," for more information on ethnic self-identification).

Interviews were conducted in Serbian, Romani, and Albanian, through interpreters hired by Human Rights Watch. Interviews were conducted individually except in the Leposavic camp, where persons were interviewed in a group and in the presence of the camp leader. All individuals were offered anonymity, and the majority of individuals preferred not to give their names to us. Individuals were told that the information they provided would be used in a report prepared by Human Rights Watch and were told that they were free to decline to answer any questions or to end the interview at any time. Nobody we approached declined an interview, although parents spoken to preferred to talk about the conditions of their children, rather than letting Human Rights Watch interview children themselves. No money was paid for any of the interviews.

Human Rights Watch conducted in-person interviews with 10 national and 21 international officials, from the Kosovo Ministry of Returns and Communities, Office of the Prime Minister of Kosovo, Ombudsperson Institution, the United Nations Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK), the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the World Health Organization (WHO), the European Union Rule of Law Mission in Kosovo (EULEX), the International Civilian Office (ICO), the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) Mission in Kosovo, and the NATO-led Kosovo peacekeeping force (KFOR). We also interviewed representatives from the following NGOs: the Roma and Ashkali Documentation Center, Mercy Corps, the Danish Refugee Council, Norwegian Church Aid, and Movimiento por la Paz.

Further interviews were carried out by phone and email in January-February 2009, including with WHO, the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Kosovo Ministry of Health, the Kosovo Ministry of Environment, the Serbian Ministry for Kosovo and Metohia, and Serb-controlled municipal authorities in north Mitrovica. We also conducted follow up with civil society groups including Romano Them/Chachipe and the Kosovo Medical Emergency Group (a network of concerned activists including NGOs and academics).

Most international officials working in Kosovo interviewed for this report requested that we withhold their names, even when commenting on uncontroversial matters.

Human Rights Watch encountered significant challenges while conducting research on past efforts to provide medical treatment to displaced persons living in areas of lead contamination. The results of the blood testing done under the auspices of WHO in 2004-06 are not publicly available. Neither are the results of blood testing conducted by the Mitrovica Institute of Public Health in Mitrovica in 2008. Human Rights Watch was provided with a summary of the results of both sets of testing, but was denied access to detailed information about the results.

There is no publicly available detailed information on the past instances of chelation therapy administration, and Human Rights Watch was unable to obtain such information despite repeated requests to relevant agencies. Human Rights Watch relied on verbal statements of camp residents, local medical practitioners involved in the camps, and international officials working on the issue while compiling the medical history section in Chapter IV of this report.

In an effort to fully assess the impact of lead on the health of displaced persons resident in camps in north Mitrovica and the effectiveness of past efforts to provide testing and treatment for lead contamination in the camps, Human Rights Watch sought the opinions of independent medical experts in Europe and the United States. But because of the lack of statistical data available, the experts contacted were reluctant to comment on the approach taken by the international community to the medical problems in the camps. The information provided here on the symptoms, effects, and treatment of lead contamination is based on reviews of medical journals analyzing studies of lead contamination.

II. Key Recommendations

To the Special Representative of the Secretary-General (in charge of the United Nations Mission in Kosovo)

- Immediately nominate the UN Kosovo Team (under the leadership of the UN Development Coordinator) to take over urgent medical evacuation, administration of medical treatment, and devising sustainable long-term solutions, for all camp residents (Cesmin Lug and Osterode as a priority, followed by Leposavic).

- Comply speedily with any finding by the Human Rights Advisory Panel.

To the United Nations Kosovo Team (including UNHCR, UNDP, WHO, UNEP)

- Arrange an acceptable temporary housing solution for residents of the Cesmin Lug and Osterode camps and relocate them immediately.

- Close and seal the Cesmin Lug and Osterode camps.

- Urgently organize treatment for lead contamination.

- Consult all camp residents (including those living in Leposavic) about their preferred long-term housing solution and proceed with planning accordingly.

To the Government of Kosovo

- Support financially the relocation and medical treatment of the camp residents, including by ensuring that adequate funds are available to relevant Kosovo ministries.

- Ensure that returnees to the Roma Mahalla have access to welfare, health, and education services, security, and access to employment as a matter of priority.

To the Serb-controlled Municipal Authorities

- Allocate suitable land to facilitate a sustainable long-term solution for the camp residents in the Mitrovica region who wish to remain in the area north of the Ibar River.

- Ensure access to welfare, health, and education services for displaced Roma in north Mitrovica, including access to health and education for those who return to the Roma Mahalla yet for practical reasons (such as a language barrier) cannot use facilities in south Mitrovica.

To the European Commission and Other International Donors

- Provide financial support to facilitate urgent medical evacuation-to cover short-term housing and longer-term sustainable housing costs, medical treatment costs, and income generation projects to ensure economic sustainability.

To the Human Rights Advisory Panel

- Promptly determine the merits of the claim from 2008 against UNMIK by around 180 Roma families alleging violations of the right to life, health, housing, and lack of access to a legal remedy, among others.

To Roma Camp Leaders in the Mitrovica Region

- Collaborate with all relevant authorities to ensure the timely relocation of the residents of the Cesmin Lug, Osterode, and Leposavic camps, the camps' permanent closure, and medical treatment to all persons in need.

III. Chronology of Events

June 10, 1999: UN Security Council passes Security Council Resolution 1244 placing Kosovo under the authority of UNMIK and KFOR.

June 1999: The Roma Mahalla is attacked by ethnic Albanians; all inhabitants flee prior to the attack fearing for their lives. KFOR does not intervene to prevent looting and destruction of all houses and infrastructure in the Mahalla.

Phase 1: UNHCR in charge

June 1999: Displaced Roma occupy the primary school building in Zvecan as well as some other public buildings in the Mitrovica region. UNHCR begins to organize temporary accommodation for the IDPs, so that they can vacate the occupied school building before the school year starts.

October 1999: UNHCR moves some of the displaced Roma residents of the Mahalla still remaining in the Mitrovica region to two camps located there: Cesmin Lug and Zitkovac. The remaining IDPs spontaneously occupy barracks in Kablare and Leposavic, creating two other camps. The move is intended to be temporary.

August 2000: Trepca mine complex is closed on public health grounds, after a damning UN study indicating high levels of lead contamination in the surrounding area.

Phase 2: UNMIK in charge

October 2001: UNMIK takes over responsibility for managing the camps from UNHCR. Displaced Roma have now been resident in the camps for two years.

2004 (month unclear): WHO facilitates the first blood testing on a group of around 50 children in Cesmin Lug, Kablare, Zitkovac, and Leposavic camps, carried out by local Serb doctors.

September 2004: WHO releases a report demonstrating very high levels of lead contamination among the Roma population in all the camps. Displaced Roma have been resident in the camps for almost five years.

April 2005: UNMIK initiates a multi-stakeholder task force called the Mitrovica Action Team-MAT (in cooperation with the Kosovo Ministry of Health and UNHCR, WHO, UNICEF, and OSCE) to develop a framework for the temporary relocation of Roma IDPs from Cesmin Lug, Zitkovac, and Kablare to the vacant KFOR barracks in Osterode.

2005: MAT concludes that return to the reconstructed Mahalla is the most sustainable solution available. It aims to devise a risk management plan for the camps, to minimize lead exposure while durable solutions for relocating camp residents are developed. Negotiations with the south Mitrovica (Kosovo Albanian-controlled) authorities begin about return to the Mahalla. Some interim remedial measures are taken in the camps, including the distribution of food and hygiene packs, delivery of wood stoves, and installation of additional water taps.

2005 (month unclear): WHO facilitates the second blood testing on a group of around 50 children from the camps in Cesmin Lug, Kablare, Zitkovac, and Leposavic, carried out by local Serb doctors.

September 2005: A local Roma activist, Argentina Gidzic, files a criminal complaint against unknown perpetrators in the Pristina court alleging a violation of article 291 of the Kosovo Provisional Criminal Code (which outlaws actions impacting the environment that endanger human life).[1] No action is taken in response to this criminal complaint.

December 2005: Norwegian Church Aid is designated by UNHCR as manager of the camps in Cesmin Lug and Osterode. KFOR hands over the Osterode camp (land and housing facilities) to UNMIK.

February 2006: The European Roma Rights Center files a complaint with the European Court of Human Rights on behalf of Roma IDPs alleging violations of the European Convention on Human Rights: article 2 (right to life), article 3 (prohibition of torture), article 6 (right to a fair trial), article 8 (right to respect for private and family life), article 13 (right to an effective remedy) and article 14 (prohibition of discrimination). The complaint is ruled inadmissible by the Court within weeks, on the ground that it lacks jurisdiction.

March-April 2006: Zitkovac and Kablare camps are closed (following a fire in the Kablare camp in March that year) and their residents moved to the Osterode camp, as a transitional location pending a durable solution in the Roma Mahalla. Residents of Cesmin Lug decline to move to Osterode.

May 2006: Start of the first part of the Roma Mahalla reconstruction project-2 apartment buildings (containing 48 flats) and 54 individual houses constructed on the Mahalla site in south Mitrovica. The flats are intended for the IDPs who cannot prove they were owners of property in the Mahalla in June 1999; those who can prove ownership have their individual houses reconstructed.

2006 (month unclear) WHO facilitates the third blood testing on a group of around 50 children from the camps in Cesmin Lug, Osterode, and Leposavic, carried out by local Serb doctors.

August 2006: WHO arranges the first of two distributions of oral chelation therapy to a group of children from the Osterode camp (the timing of the second distribution is not known to Human Rights Watch). In total, around 40 children are treated in the two rounds.

June 2007: Around 90 families (around 450 individuals) return to the Roma Mahalla from all the Mitrovica camps as well as from Serbia proper[2] and Montenegro. The return is organized by the MAT task force under UNMIK's leadership.

May 2008: UNMIK hands over management of the Cesmin Lug and Osterode camps to the Kosovo Ministry of Communities and Returns. Norwegian Church Aid continues to act as manager of the Cesmin Lug and Osterode camps. Some displaced Roma from the Mahalla have been resident in lead contaminated camps for more than 8 years.

Phase 3: Kosovo Ministry of Communities and Returns in charge

July 2008: A complaint is filed by a Roma rights activist on behalf of Roma families from all the camps (Cesmin Lug, Osterode, Leposavic) with the Human Rights Advisory Panel alleging criminal negligence leading to severe environmental contamination causing a severe health hazard to the camps' inhabitants, as well as violation of the rights to life and family life, and lack of a legal remedy.

October 2008: Roma leaders ask the Mitrovica Institute for Health to conduct blood tests on children in Cesmin Lug, Osterode, and Leposavic. Out of 53 tested, 21 have blood lead levels requiring immediate medical intervention as they face significant threats to their life (over 65 mcg/dl, which is the highest level the machine could register), 18 had levels of 45 mcg/dl, and only two children had results within the norm. The results in Leposavic (the fourth camp located around 50 km away from the other three) were lower, yet still above the acceptable norm of 10 mcg/dl.

January 2009: WHO visits Kosovo to examine the situation in the camps and talk to the key local and international interlocutors, following which it publicly calls for the closure of the Osterode and Cesmin Lug.

January 2009: Norwegian Church Aid hands over management of the Cesmin Lug and Osterode camps to the local NGO Kosovo Agency for Advocacy and Development (KAAD), funded by the Kosovo Ministry of Returns and Communities.

June 2009: Some displaced Roma from the Mahalla have now spent a decade living in lead contaminated camps.

June 5, 2009: The Human Rights Advisory Panel rules the Roma claim to be admissible on multiple counts, including in relation to allegations of violations of the right to life, the prohibition of inhuman and degrading treatment, respect for private and family life, the right to a fair hearing, the right to an effective remedy, the right to adequate housing, health and standard of living, the prohibition against discrimination in general, the prohibition of discrimination against women, and the rights of children.

IV. Background

Kosovo's Romani Communities

In Kosovo the Romani communities are generally characterized as Roma, Ashkali, and Egyptians (RAE).[3] Although identities are fluid among ethnic Roma in Kosovo, those describing themselves as Roma are mainly Serbian- and Romani-language speakers, and tend to live in the Serb-majority areas (north of the Ibar River as well as the Serbian enclaves). Those describing themselves as Ashkali and Egyptians are Albanian-language speakers, who live mainly, but not only, in ethnic Albanian majority areas.

The first documented Roma arrivals to the Balkans were in the sixteenth century during the Ottoman period.[4] The majority of Kosovo Roma were traditionally Muslim; smaller numbers were Eastern Orthodox and Catholic.[5]

Separate Ashkali and Egyptian identities emerged during the period of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (1946-92). Some scholars have attributed this to the government's openness to the expression of new forms of Romani identity and the assimilation of certain Romani communities into Kosovo Albanian society, which led them to "rediscover" their ancient origins.[6]

The political instability in Yugoslavia that followed the death of Tito in 1980 affected Kosovo, with increasing tension between Serbs and ethnic Albanians, and discrimination against ethnic Albanians after Slobodan Milosevic came to power. Roma felt "stuck in the middle."[7] During the 1990s the division of Kosovo Roma into the Serbian-speaking Roma and the Albanian-speaking Ashkali and Egyptians solidified.[8]

The armed confrontation of the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) with Yugoslav government forces and Serbian paramilitary units, the subsequent NATO bombing, and the wave of retaliatory ethnic violence by Albanians at the start of international rule in Kosovo in 1999 resulted in RAE both fleeing and being forcibly expelled from Kosovo on a massive scale.[9] It is estimated that around 40,000 RAE remain in Kosovo today, as opposed to the estimated 200,000 before the war.[10]

The term RAE has been used by UNMIK since 2000 and is widely used among international agencies in Kosovo. The term remains controversial among some representatives of the Roma community, who see it as a factor contributing to the divisions within what they contend should be a cohesive and single community.[11]

The majority of the members of the Romani communities interviewed by Human Rights Watch for this report identify themselves as Roma. This report uses the term Roma to refer to that population, except where the person interviewed identified him or herself as Ashkali, in which case that self-identification is noted (none of those we interviewed for this report described or identified themselves as Egyptian).

Lead Contamination Symptoms, Effects, Testing, and Treatment

Lead is a poisonous metal that poses serious health and environmental hazards. Excessive lead levels in the human body can cause damage to the nervous and reproductive systems and kidney failure. Very high lead levels lead to coma and death.[12]

Symptoms of lead poisoning vary depending on the age of the individual and the extent of exposure.

Generally, people exposed to lead at a low level do not display symptoms of poisoning. The severity of symptoms increases with prolonged exposure. Symptoms can range from neurological and physical problems such as anxiety, insomnia, anemia, memory loss, sudden behavioral changes, concentration difficulties, headaches, abdominal pains, fatigue, depression, hearing impediments, muscle spasms, disorientation, convulsions, high blood pressure, and sore or bleeding gums.[13] The adverse health effects of lead poisoning can be irreversible.[14] Lead contamination can also exacerbate preexisting medical conditions such as kidney failure[15] and hypertension (increasing the risk for heart diseases and cerebrovascular diseases).[16]

Lead poisoning is particularly harmful to children, as they absorb lead more easily than adults. In children, exposure to lead can easily damage internal organs (especially the brain and kidneys) and the nervous system, stunt growth, damage hearing and speech, and cause behavioral problems.[17] A significant and irreversible effect of prolonged exposure to lead is the impairment of intellectual development (indicated by decreased IQ scores).

Among pregnant women, lead exposure can result in stillbirth, miscarriage, and can negatively affect brain development of a fetus, leading to disabilities and mental retardation.[18]

People can be exposed to lead through inhalation, ingestion, and skin contact. Other significant sources of contamination are motor vehicle exhaust of leaded gasoline, industrial sources such as smelters and lead manufacturing/recycling industries, lead water pipes, and leaded paints.[19] Poor and disadvantaged populations are more vulnerable to lead poisoning because poor diet increases the amount of ingested lead the body absorbs.[20]

There are a few different ways of testing for lead presence in humans. Tests on blood drawn from a vein are considered to be the most accurate.[21] Tests on capillary blood are deemed less reliable because they carry a greater risk of contamination (and thus should be confirmed through puncture of a vein). Another method of testing lead levels in human bodies is through taking hair samples.[22]

The most common treatment for lead poisoning is chelation therapy, which uses chelating agents (substances whose molecules can bond to lead and other metal ions, thereby neutralizing them), most commonly CaEDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid), a synthetic amino acid, to bind lead and reduce the circulation of lead in the blood. It can be administered through intravenous injection or orally (in a form of dimercaptosuccinic acid).[23]

Chelation treatment is generally prescribed in cases of severe lead poisoning with lead levels greater than 45 micrograms of lead per deciliter of blood (mcg/dL). For children with blood lead levels less than 45 mcg/dL, chelation therapy appears not to be beneficial.[24]Several studies have suggested d-penicillamine as both safe and effective in the treatment for low-level lead poisoning.[25] Clinical trials to assess the safety and efficacy of d-penicillamine are ongoing.[26]

Oral chelation therapy has numerous proven side effects, including headaches, skin irritation, nausea or stomach upset, extreme fatigue, fever, cramps, and pain in the joints.[27]Among the most serious possible side effects are kidney damage, bone marrow depression, shock, low blood pressure (hypotension), convulsions, disturbance of regular heart rhythm, allergic heart reaction, and respiratory arrest.[28] The drugs used in chelation therapy also eliminate other (useful) heavy metals from the body, such as iron, zinc, and cooper. A vitamin-, iron- and calcium-rich diet is typically proved to replenish essential minerals and to reduce the absorption of lead into the blood.[29]

According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, lead detoxification strategies should be coupled with comprehensive environmental impact assessments and monitoring, to identify contamination sources, in order to devise strategies to minimize their impact.[30] Without eliminating lead exposure, chelation may not be fully effective[31] and chelating agents may facilitate absorption of lead from the gastrointestinal tract. The effect of treatment will further be attenuated by the resumption or continuation of lead ingestion.[32]

History of lead contamination in the Mitrovica region

Mitrovica, a municipality located in the north of Kosovo, has been for years known for its environmental pollution caused by the mining industry. The Trepca mine complex, established in 1926, focused on the extraction of lead, zinc, and cadmium, and to a lesser extent gold and silver.[33]

Academic studies during the 1980s and 1990s showed a high concentration of lead in the water, soil, and air in Mitrovica, and discussed the damaging impact on health of the region's inhabitants.[34] Despite these findings, the mine stayed operational until the Kosovo war closed it in 1999, and a year after the conflict, in June 2000, the local management of the mine complex unilaterally decided to reopen the facility. Around the same time, KFOR started receiving information about blood tests showing high levels of lead contamination among international troops stationed in Mitrovica. Based on that information, UNMIK decided to close the Trepca facility in August 2000, and to analyze the situation with the assistance of external consultants, KFOR, and local health workers.[35]

UNMIK commissioned two of its civil affairs officials to carry out a public health analysis of lead pollution in the region. Using past documentation, analysis of dust, soil, and vegetation samples collected in various locations in Mitrovica in August 2000, and consultation with international public health experts, their report, published in November 2000, showed that the level of lead contamination exceeded the norm by up to 176 times in the vegetation samples, by 122 times in the soil, and showed high concentrations of lead in dust (up to 4630 mg/kg). The report also analyzed blood tests on various populations in the area. Particularly high lead levels were observed among the Roma IDP camp residents, with the report pointing out that the contamination levels were "higher for Roma than non-Roma persons."[36] Other risk factors identified by the report were previous employment at Trepca and geographic proximity to it, with areas in the vicinity of the mines described as high-risk.

Despite the environmental risks posed by the Trepca mine, it continues to be seen by some as a potential source of prosperity for Kosovo. UNDP is currently said to be looking at the "sustainable reactivation" of the Trepca mine complex to help revitalize the region's economy.[37] On February 20, 2009, International Civilian Representative Pieter Feith emphasized the future role of Trepca as a unifying factor, connecting "the mines in the north and [population] centers in the south."[38]

Applicable Law in Kosovo

Both the UN and Kosovo authorities are obliged under international law to protect and assist minorities and displaced populations in Kosovo. UN Security Council resolution 1244 authorized the establishment of UNMIK mandated with broad executive and legislative powers to run civil administration functions, build democratic institutions and the rule of law, maintain security, and protect human rights.[39]

On December 12, 1999, UNMIK regulation 1999/24 "On the law applicable in Kosovo" entered into force, ruling the three main sources of law to be the regulations promulgated by the special representative of the UN secretary-general (SRSG), subsidiary instruments, and the law in force in Kosovo on March 22, 1989.[40] Article 1.3 of this regulation stipulates that the following international human rights standards shall be observed by both international and local authorities in Kosovo: the Universal Declaration of Human Rights; the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) with Protocols; the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) with Protocols; the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR); the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Racial Discrimination; the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women; the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhumane or Degrading Treatment or Punishment; and the Convention on the Rights of the Child.

To date, regulation 1999/24 has not been amended or repealed. Kosovo's 2008 declaration of independence was followed by the adoption of the Constitution of Kosovo, which entered into force on June 15, 2008.[41] Article 22 ("Direct Applicability of International Agreements and Instruments") preserves all of the international instruments mentioned above, with the notable exception of the ICESCR, while adding the Council of Europe Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities.

The provisional institutions of self-government (PISG) in Kosovo undertook to comply with the obligations under the ECHR and its five protocols through the 2001 Kosovo constitutional framework, which is compatible with UN Security Council resolution 1244. The government of Kosovo reiterated its commitment to do so in the 2008 constitution.

Neither UNMIK nor the government of Kosovo are states parties to these treaties. Kosovo is not formally recognized as a country in the Council of Europe, and as such it cannot ratify the ECHR.[42] Nonetheless, UNMIK and the government of Kosovo have agreed to respect these treaties as if they were parties to them, and it is appropriate to assess their compliance with them on that basis. It is also important to note that the UN human rights bodies (including the Human Rights Committee and the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights) have reviewed the acts of UNMIK as if it were a state party. For example, the Human Rights Committee has stated, in 2006, "It follows that UNMIK, as well as PISG, or any future administration in Kosovo, are bound to respect and to ensure to all individuals within the territory of Kosovo and subject to their jurisdiction the rights recognized in the Covenant."[43]

Map of the Mitrovica Region

© 2009 Human Rights Watch

Map of Mitrovica City

© 2009 Human Rights Watch

V. A Decade of Failure to Assist the Mitrovica Roma

Forced Displacement from Mitrovica

Prior to 1999 the "Roma Mahalla"[44] in Mitrovica, located on the south bank of the Ibar River, hosted the largest Roma community in the former Yugoslavia.[45] Over 8,000 people lived in the neighborhood.[46] According to a leading representative of displaced Roma from Mitrovica, the main source of income for most residents was daily private labor.[47] While the Roma community living there was considered to be poor, there were quite well-to-do families living in the Mahalla, residing in large family houses.[48]

The Roma community in Mitrovica already found itself in a difficult situation prior to the 1999 conflict. In the north of Kosovo, RAE were largely Serbian (and Romani) speakers, with limited knowledge of the Albanian language. Due to the linguistic affinity with the Serbs, as well as the fact that some Roma held official positions in ethnic-Serbian-dominated structures (including the police), they became resented by some members of the Albanian community.[49] As one of the Mahalla returnees stated to Human Rights Watch, "Roma have always been between Serbs and Albanians, and kicked from all sides. While we tried to stay neutral, we were always accused of choosing one side over another."[50]

In the 1999 conflict ethnic Albanians suffered mass expulsion and killings at the hands of Serbian forces. In the conflict's wake there was a wave of violence against minorities perpetrated by Albanians. This violence targeted RAE as well as Serbs, due in part to the perception of RAE as "Serbian collaborators."[51] Fearing repression, many RAE left Kosovo from 1999 onwards, becoming internally displaced persons in Serbia (which currently hosts over 22,000 Kosovo RAE, amounting to over 10 percent of all IDPs there) and Montenegro (currently over 4,400 Kosovo RAE, now formally refugees), or refugees in Macedonia (currently over 1,700 Kosovo RAE), and Bosnia (currently over 160 Kosovo RAE).[52] There are no reliable estimates of the number of Kosovo RAE who have sought refuge outside the region.

The destruction of the Roma Mahalla by Kosovo Albanians in June 1999 was one of the darkest chapters of the post-war violence against Roma. Fearing aggression from Kosovo Albanians, Roma had left the Mahalla and crossed to north Mitrovica. Their houses were looted and burned down by Kosovo Albanians. KFOR did not intervene to protect the property of the displaced, and the violence left over 750 houses destroyed and the entire Roma Mahalla population displaced.[53]

Initially, around half of the Mahalla's 8,000 inhabitants fled to the northern (Serbian-majority) areas in Kosovo where they occupied some public buildings (mainly the Zvecan primary school), and the rest moved across the then-administrative border into Serbia proper, planning to further relocate to various countries in Western Europe.[54] Some displaced Roma from Mitrovica subsequently also left northern Kosovo for Serbia, neighboring countries, and Western Europe. Reliable statistics for these onward movements are not available. However, the current total number of Roma living in the Mitrovica region hovers around 1,500.[55]

To accommodate displaced residents of the Mahalla who remained in northern Kosovo, UNHCR created the two camps at Cesmin Lug and Zitkovac in the vicinity of the Trepca mine complex. When the two camps were full, other displaced persons from the Mahalla spontaneously occupied former Yugoslav army barracks at Kablare (adjacent to Cesmin Lug) and Leposavic (45 kilometers northwest of Mitrovica), creating two more camps.[56] The majority of displaced Roma in Cesmin Lug, Zitkovac, and Kablare were housed in makeshift tents, huts, and metal containers.

The approximately 200 displaced persons who initially occupied the Zvecan primary school relocated to Zitkovac and Cesmin Lug in October 1999.[57] At the Leposavic barracks there were initially around 500 Roma IDPs. The numbers initially at the Kablare camps are not available as, according to UNHCR, "The Kablare barracks were never recognized by UNMIK formally as a temporary collective accommodation."[58] Over time, the camps received additional arrivals of persons hoping to receive international assistance and be included in the future rehousing plans.[59]

History of Efforts to Find Durable Solutions for Camp Residents

The camps were planned by UNHCR as a temporary solution. UNHCR tried to explore possibilities to find better accommodation for the IDPs-according to UNHCR these attempts failed because of unwillingness on the part of both Serbian and Albanian communities to identify any alternative location. "In 1999, we had to respond to an emergency and found the camps as a temporary facility," said Francesco Ardisson, senior protection officer at UNHCR Kosovo, "Unfortunately, we have been unable to find an alternative site because neither the Albanians nor the Serbs want them."[60]

The camps were managed by UNHCR until October 1, 2001.[61] During this period UNHCR was directly responsible for the camps, providing residents with food and hygiene aid, as well as coordinating periodic delivery of other aid such as clothes, and "assisting IDPs as per its mandate (protection and assistance) in Kosovo."[62]

UNMIK took over the task of camps management from UNHCR in October 2001, and was in charge of the camps until May 2008. During this period UNMIK was in charge of "administration of the camps, provision of technical and practical assistance to the residents, facilitating voluntary returns of the camp residents willing to return."[63] According to an UNMIK official, "One of the objectives of UNMIK has from the very beginning been to facilitate return of these camp residents to their homes in Kosovo."[64] Despite this, no returns (including individual ones) took place until June 2007.

The first scrutiny of the lead contamination problem was conducted by an American Roma rights activist, Paul Polansky, on his individual initiative, beginning in 1999.[65] From 2004 on, Roma and other human rights organizations began issuing alarming statements about terrible health and living conditions in the camps. These prompted the World Health Organization to conduct an assessment in Cesmin Lug and Zitkovac in the summer of 2004. The assessment led to a WHO report in September 2004 alerting UNMIK to the adverse effects of lead contamination on Roma IDP health, and stressing the need to close the camps.[66]

It was only then that UNMIK actively started to seek to relocate the Mitrovica Roma as a group.[67] The first inter-agency coordination efforts took place in April 2005, when the key international actors (including UNMIK, UNHCR, WHO, UNICEF, and OSCE) formed the Mitrovica Action Team (MAT), to articulate and coordinate a sustainable solution for the residents of the camps.[68] The consensus that emerged among the stakeholders toward the end of 2005 was that return to the Roma Mahalla should be encouraged and supported as the most sustainable solution, while a new camp at Osterode (buildings and barracks abandoned by KFOR in late 2005) was deemed to be the best temporary solution available.[69] KFOR handed over the Osterode camp to UNMIK on December 10, 2005.

The NGO Norwegian Church Aid assumed responsibility for day-to-day management of the camps in December 2005.[70]Other agencies, such as UNHCR, WHO, and KFOR, continued to provide technical and practical assistance to the camps.[71]

From March to April 2006 the inhabitants of the Zitkovac and Kablare camps voluntarily moved to the Osterode camp (after the Kablare camp burned down in March 2006[72]), on the promise of better living conditions, food aid, and medical treatment.[73] These two camps were subsequently closed and demolished.[74]

UNMIK insists that the Osterode camp represented an improvement on the other camps close to Trepca. According to an UNMIK spokesperson,

To ensure that the new (Osterode) site would be a safer and healthier environment, UNMIK engaged a team of environmental engineers from the US Army who did a thorough testing of the soil, the water, and the buildings in Camp Osterode and presented their recommendations; there were no obvious signs of environmental contamination. After the remediation, WHO again tested the camp and has concluded that the camp is far safer from a lead stand point than the current camps. On 16 February 2006, Dr Marc Danzon, the Regional Director for Europe of the World Health Organization, accompanied by his senior advisers, joined the Principal Deputy SRSG, Larry Rossin, in calling on the Roma to vacate their current camps and to "immediately relocate to the safer environment of Camp Osterode as an emergency health requirement."[75]

According to Dorit Nitzan, head of the WHO country office for Serbia, WHO regarded Osterode as "lead-safer" than the other camps because of concrete surfacing in external areas of the camp, which reduces exposure to contaminated soil found in the other camps; the absence of the lead paint found on some doors in other camps; and the presence of running water inside the housing, which facilitates more regular washing.[76]

In parallel with the closure of Zitkovac and Kablare, the reconstruction of two apartment buildings (comprising 48 flats) and 54 individual houses took place on the site of the previously destroyed Roma Mahalla in south Mitrovica. In the early summer of 2007, around 90 families (450 people) from Zitkovac, Kablare, the other camps as well as other locations outside Kosovo moved back to the Roma Mahalla, making it the largest Roma return site since 1999. Many of those who returned did not remain (see Chapter VI, "Current Conditions in the Camps and the Rebuilt Mahalla").[77]

Only a fraction of the Cesmin Lug camp residents decided to move to Osterode, located only around 150 meters from their location, not believing that this temporary shift to such a close location would be advantageous from the medical point of view or otherwise.[78]

In January and October 2008 UNMIK provided two separate sets of replies to the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, in which it responded to a number of questions about the situation in the camps and steps taken to address the problems. It quoted the assessment of its implementing partner Norwegian Church Aid that the residents of Cesmin Lug "continue to reside [there] by their choice," attributing the unwillingness to move to the alternative site of Osterode to "1) Lack of faith that safe, permanent housing will result from their humanitarian relocation, and that Cesmin Lug residents will not simply be relocated, yet again, from one 'temporary situation to another; 2) The perceived higher standard of living and social cohesion within Cesmin Lug camp when compared to conditions in Osterode; 3) The perception that Osterode camp, although intended to provide safe medical relocation and treatment for Roma IDPs exposed to unsafe levels of lead exposure, is, in itself, just as contaminated as Cesmin Lug."[79]Controversially, UNMIK described the illegal smelting of car batteries allegedly carried out by the camps' residents as the key cause of lead contamination (see below).[80]

The Kosovo Ministry of Communities and Returns took over responsibility for the camps from UNMIK in May 2008.[81] According to the information received by Human Rights Watch from an international official in Kosovo familiar with the situation, the handover of the management to the Ministry of Communities and Returns "was discussed in January 2008 with the Ministry, who agreed to finance the management of the camps Osterode and Cesmin Lug. The Ministry was assisted with the signing of MoU (Memorandum of Understanding) with NCA [Norwegian Church Aid], and the relevant information was handed over to the Ministry by NCA."[82] During his meeting with Human Rights Watch, Deputy Minister Ismet Hashani reiterated his ministry's commitment to finding durable solutions for residents in the camps.[83] But the minister failed to provide any details as to how the ministry was going to meet this commitment or a timeframe in which it planned to do so. Norwegian Church Aid ceased its camp management activities in December 2008, and in January 2009 a local NGO called the Kosovo Agency for Advocacy and Development (KAAD) took over camp management, with funding from the Ministry of Communities and Returns.[84]

On March 9, 2009, Human Rights Watch received an email from the leader of the Roma camps, Skender Gusani, in which he communicated the distress of camp residents over the lack of information about the future plans for Cesmin Lug and Osterode camps, both in terms of long-term housing and treatment for lead contamination. He stated that camp residents were concerned with the takeover of the camps' management by KAAD as another sign of the "international community" pulling out of the situation.[85] The common view conveyed by all of the Roma interlocutors interviewed by Human Rights Watch in November-December 2008 is that they have lost trust in the solutions proposed by the "international community" and that they are tired of empty promises and temporary solutions that become permanent. The current level of distrust makes it that much harder to negotiate an immediate evacuation of the camps because residents are afraid they would be removed to even worse conditions.[86]

On April 1, 2009, the Kosovo Ombudsperson published an open letter to the Kosovo Prime Minister Hashim Thaci, in which he described the results of his ex officio investigation into the situation in the camps, and called for the immediate and sustainable relocation of the camps' population, "in consultation with the community leaders, in a location where their safety and dignity are guaranteed."[87] The Ombudsperson also recommended "the immediate intervention of the (Kosovo) Ministry of Health, in cooperation with the (Kosovo) Ministry of Communities and Return in order to improve the health conditions of the Roma population still living in the camps and/or is still affected by the lead contamination."[88]

According to the information received by Human Rights Watch from the Ombudsperson, as of April 27, 2009, the government had yet to respond to the recommendation or reply to his letter.[89]

The European Commission referred to the problem in its most recent progress report on Kosovo, in November 2008.[90] Moreover, in a January 2009 reply to the European Parliament's written question about the status of current efforts to close the camps, it stated, "The Commission and the Kosovo Government are presently preparing the EU 2009 assistance package under the Instrument of the Pre-Accession [sic] to offer sustainable solutions to re-locate and treat appropriately some of the families living in the ... camps. Addressing this critical issue requires full commitment from all stakeholders, including the Roma community, as well as careful preparation and coordination between local and international partners involved."[91] The European Parliament, in a February 2009 resolution on Kosovo and the role of the EU, again recognized the seriousness of the situation in the camps, expressing "grave concern at the acute ill-health of Roma families in the Osterode and Cesmin Lug refugee camps," and urged the European Commission "to continue to work to secure the relocation, as a matter of urgency, of the families concerned."[92]

The current status of efforts to close the camps is discussed in Chapter VI.

Roma activists' efforts to compel a solution

Alerted by Paul Polansky's work, the international NGO the European Roma Rights Center (ERRC) conducted a series of trips to Kosovo in 2005, interviewing Roma leaders and raising the profile of this issue.[93] In September 2005 ERRC filed a criminal complaint on behalf of a camp resident with the Public Prosecutor in Pristina, alleging a violation of article 291 of the Kosovo Provisional Criminal Code, which states that whoever causes danger to human life or property by means of exposure to toxic and other harmful substances would be punished by imprisonment from three months to three years.[94] The complaint called for "an investigation to be conducted on those persons vested with effective exercise of power, who were responsible for the placement of Roma in the toxic land and aware of risks involved and consequences to health."[95] According to the person on whose behalf the complaint was filed, the activist Argentina Gidzic, no action was ever taken in response to her complaint.[96]

The organization Romano Them (now called Chachipe) and Roma organizations in Kosovo including the Roma and Ashkali Documentation Center and the Roma and Travelers Forum have also sought to focus attention on the issue.[97]

In August 2005, the Council of Europe Coordinator for Roma and Travelers activities conducted a field mission to Mitrovica to assess what measures were needed to avoid further lead poisoning. The mission report recommended immediate evacuation of the Roma community from the contaminated area.[98]

In February 2006 the ERRC filed an application with the European Court of Human Rights alleging human rights violations ranging from violation of the rights to life, health, and adequate housing, to cruel and unusual treatment and the lack of legal remedy. The complaint was rejected by the Court for lack of jurisdiction the same month.[99]

In July 2008 Diane Post, a Roma rights activist granted power of attorney by Mitrovica Roma families (and who had previously helped the ERRC to file the European Court complaint), helped an international law firm to file a complaint on behalf of the Roma families with the Human Rights Advisory Panel (HRAP).[100] Specific claims included: violation of the right to life; inhuman and degrading treatment; lack of recourse to an independent and impartial tribunal; interference with private and family life; violation of the right to a home; denial of access to data; and violation of the right to an effective remedy. The claim was deemed admissible on June 5, 2009, in relation to allegations of violations of the right to life, the prohibition of inhuman and degrading treatment, respect for private and family life, the right to a fair hearing, the right to an effective remedy, the right to adequate housing, health and standard of living, the prohibition against discrimination in general, the prohibition of discrimination against women, and the rights of children. [101] The determination of the merits remains pending at this writing.

History of Efforts to Provide Medical Treatment for Lead Poisoning

Absence of a comprehensive strategy for treatment and decontamination

The November 2000 public health report commissioned by UNMIK (see Chapter IV) noted risk factors based on RAE ethnicity and proximity to Trepca. It recommended extended population testing for lead, and treatment (especially for high-risk groups such as children and pregnant women).[102] According to UNMIK, the report, "as part of a LONG TERM strategy, called for subjecting the entire Mitrovica population to epidemiological studies over several years, creating specialized medical teams, education and training of Serbian and Albanian local doctors, education campaigns, treatment provided outside of the contaminated area, periodic environmental sampling, extensive technical support for local health facilities, relocating the Roma camp to a lower risk area and continuous education on how to reduce lead exposure."[103]

When Paul Hunt, the then-UN rapporteur on the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health, called on UNMIK in October 2005 to provide further information on its action to address the health problems in the camps,[104] UNMIK's prompt response referred to "ongoing measures to address the health issues, coordinated by the Ministry of Health through the Health Task Force, including medical teams that are working full time in the camps to provide regular and consistent health care." It also claimed that "consensus has been reached between health professionals on how to treat children and the public health situation had improved after repairs and renovation of the water and sewage infrastructure."[105]

In reality, since the publication of the 2000 report commissioned by UNMIK little progress has been made by international agencies or Kosovo institutions to develop a comprehensive strategy to deal with heavy metal contamination in the Mitrovica region as a whole.[106] Because of the large number of actors and the lack of coordination, the approach has always been scattered. In the words of a doctor previously involved in the camps, "all these efforts at best amounted to scratching the surface."[107]

UNMIK's 2008 statement attributing the high level of contamination principally to illegal smelting of batteries (see above) has been a source of ongoing controversy.[108] Roma leaders and camp residents told Human Rights Watch that smelting was discontinued in 2006 and Roma leaders said they are monitoring the community in order to make sure everybody adheres to the prohibition.[109] Nevertheless, according to an expert from the US Centers of Disease Control and Prevention, who visited the camps in February 2009, some evidence of individual smelting activities were found:

I saw evidence of a fire with the characteristics of an informal smelter including burn marks, metal debris and broken cement blocks which are often used to support a cauldron to melt metal. This site was on a cement pad next to the clinic facility (ambulanta). The solution to this is not to castigate the Roma for doing this work but rather to develop a way for them to do it safely.[110]

Chachipe, a Roma rights organization, argues that UNMIK's emphasis on the smelting by some Roma constitutes "blaming the victim" and serves as a smokescreen for the failure by UNMIK to tackle the real contamination sources, namely the piles of contaminated soil just behind the Osterode and Cesmin Lug camps.[111]

Testing and chelation therapy

During the period 2004-06, under the auspices of WHO at least three rounds of testing of blood samples from children, usually around 50 children each time. The capillary blood tests were analyzed by the Institute of Public Health attached to the hospital in north Mitrovica.[112]

After two rounds of blood tests in 2004 and 2005 (the results of which are not publicly available), the first administration of oral chelation therapy took place in August 2006 and the second later that year, on the initiative of WHO and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and provided through the Institute of Public Health.[113] Overall, around 40 children received oral chelation therapy.[114] Children from Osterode were chosen for treatment, rather than those from Cesmin Lug, because Osterode was considered a less contaminated environment, with fewer side effects for the children.[115] A third round of blood tests under WHO's auspices took place in 2006.

A weekly consignment of food rich in vitamins and calcium was delivered in the Osterode, Cesmin Lug, and Leposavic camps by Norwegian Church Aid beginning in 2005.[116] Other risk-reducing measures taken were daily washing of the concrete surfaces in Osterode camp, a practice that continues.[117]

Bloods tests, chelation therapy, and nutritional intervention all ceased in 2007, however. In a reply to the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights to questions about the steps taken to address the problems in the camps, UNMIK stated that medical treatment, including chelation therapy and nutritional supplements were "carried out for those IDPs relocated to Osterode Camp" but that "these medical components were discontinued in 2007 as determined by WHO to no longer be of necessity."[118] According to the information received by Human Rights Watch from UNMIK, the chelation therapy administered in 2007 "led to [a] dramatic decrease in blood-lead level to the extent that in June 2007, the US Center for Disease Control advised that the food supplement packages were no longer needed."[119] According to correspondence received by Human Rights Watch from a CDC representative involved in the Kosovo projects, "This was done with the understanding (...) that the relocation to Mahalla was in near future. The real tragedy is that relocation was not completed."[120]

Since the decision by UNMIK to discontinue the "medical components" of the strategy dealing with the camps in 2007, there has been no systematic assessment of the health situation in the camps. But because of the small numbers of individuals reached and the inconsistent and time-limited provision of chelation therapy, it can be assumed that little impact has been achieved to mitigate the ongoing crisis of lead poisoning in the region.

Two years on, and with the camps still in existence, WHO once again assesses the lead contamination as critical: On January 31, 2009, following a WHO delegation visit to Kosovo to assess the current situation in the camps, WHO issued a press release calling on the international and Kosovo institutions to increase efforts to reduce toxicity and to take action on relocating the camp populations. According to the press release,

Lead poisoning in this area poses a severe risk to the population of Mitrovice/a. WHO appeals for better coordination and communication between the health institutions and is ready to provide technical assistance.... WHO asks for those who are still living in temporary camps to be relocated to a lead-safe environment as soon as possible, and particularly for Cesmin Lug Camp to be closed as a matter of urgency, in order to avoid another wave of newcomers. The area near the tailing dams should be declared a hazardous place for humans.[121]

Community-led efforts

During our visit to Kosovo in November-December 2008, Human Rights Watch heard contradictory information regarding perceptions of the past efforts to test the population for lead and administer chelation therapy based on the test results. Some Roma leaders complained to Human Rights Watch that the results of lead testing were not transparently communicated and explained to the camp residents.[122] Skender Gusani, the leader of all the Roma camps, criticized the way in which assistance and treatment had been administered as haphazard. While admitting that "some attempts have been made by various NGOs and international organizations" to educate the Roma about the dangers of lead and about the kinds of treatment available, Gusani pointed out that "a few times constantly changing groups of children have their blood tested for lead and then are given some kind of pills. Everything was done in a way which is very far from professionalism and transparency."[123] This allegation is rejected by both WHO and Norwegian Church Aid representatives, who were in charge of (respectively) assisting the local structures in treatment delivery and managing the camps at that time.[124]

Nevertheless, due to the alleged lack of transparency of the results of the testing, camp residents became increasingly wary of the internationally coordinated efforts to test blood and treat contamination, although not with testing and treatment per se. After UNMIK discontinued testing and treatment, camp leaders turned to the Serbian state-run Mitrovica Institute for Public Health in late 2007 to run further blood tests. The institute carried out blood testing in April 2008 on children selected in all three camps in the north (Cesmin Lug, Osterode, and Leposavic), as well as the Roma Mahalla. These were not the same children tested previously.

The results of the April 2008 tests demonstrated unacceptably high lead levels in the children tested. Out of the 53 children tested, 21 had lead levels qualifying these children for immediate medical intervention (over 65 mcg/dl, which is the highest level the equipment can record).[125] The testing does not provide a breakdown by camp. No further chelation therapy has been administered.

Although the monitoring equipment was unable to record the precise lead level of these 21 individuals, WHO nonetheless conducted a statistical assessment of the mean blood levels, finding an overall decrease, with the most significant drop-unsurprisingly-among individuals who had moved to the Mahalla.[126]

Treatment Compromised without Relocation

The November 2000 public health report commissioned by UNMIK pointed to the lack of effectiveness of treatment without relocation, stating that "treating people does not have a promising outlook if there is no possibility to keep them away from polluted area after that."[127] The report concluded that a comprehensive strategy was needed to address the issue, and that it should be "designed and implemented only on a basis of broad international cooperation." But it also noted that the "costs of such an enterprise will exceed financial capacity of UNMIK."[128]

According to Dorit Nitzan, who has been involved with the Roma camps since 2004,

The right approach to lead poisoning is to first remove the source or the people from the source of exposure. For this, WHO has constantly asked to relocate the population from the source of exposure. Treating them while in a lead contaminated area is not recommended practically. We were promised by UNMIK that the move to Osterode is for a short period, until the Mahalla is [re]built. However, the IDPs are still there. We call to concentrate efforts to move the IDPs from the lead contaminated areas, NOW."[129]

Ironically, UNMIK's explanation of the reason for the abandonment of medical treatment as not "medically relevant" from 2007 onwards (based on WHO's recommendation), combined with the argument that Osterode was "lead-safer," informed the policy approach of not treating the relocation from that area as an emergency.[130]

VI. Current Conditions in the Camps and the Rebuilt Mahalla

During our research in December 2008, Human Rights Watch visited Roma camps and settlements across Kosovo, including the camps at Cesmin Lug, Osterode, and Leposavic, and the Roma Mahalla.

The Camps

As noted above, management of the camps passed from Norwegian Church Aid to the Kosovo Agency for Advocacy and Development at the beginning of 2009. KAAD's budget, funded by the Kosovo Ministry for Communities and Returns, helps to cover the utility bills of the camps, as well as the costs of running a small clinic (ambulanta[131]) serving Cesmin Lug and Osterode, and amounts to only €78,000 for the first six months of 2009.[132]

In terms of the availability of basic medical facilities and medicine, the poor situation in the camps around Mitrovica is not entirely distinguished from similar camps in other parts of Kosovo: Human Rights Watch observed similar problems with access to medicine and specialized medical help in other Roma IDP camps and settlements we visited in November-December 2008.[133] What is unique about the situation in the Mitrovica Roma camps is the lack of systematic efforts to monitor the levels of lead contamination and provide adequate remedy.

Cesmin Lug

Among all the camps visited, Human Rights Watch observed the worst living conditions in the Cesmin Lug camp, located in the vicinity of the toxic slag heaps of lead-contaminated soil. The inhabitants there live in small shacks made of wood, some of them insulated with cardboard lining. There is no running water in the huts-the inhabitants collect water by bucket from outside pumps. Camp residents complained bitterly about this to Human Rights Watch.[134] As throughout the north Mitrovica region, the electricity supply is frequently interrupted: According to the people Human Rights Watch interviewed in Cesmin Lug, the normal cycle is two hours on/three hours off during the winter.[135]

In Cesmin Lug Human Rights Watch spoke to the camp leader, Latif Musurica, as well as other camp residents. According to Musurica, Cesmin Lug hosts around 170 persons (47 families)-33 families have been resident in the camp from the very beginning, while the others moved there after the closure of the Kablare and Zitkovac camps.[136] (Musurica's figures differ from data from NCA and Mercy Corps in mid-2008 that there are 38 families in the camp.[137])

According to the residents Human Rights Watch spoke to, the most prevalent diseases among the camp residents are kidney problems, high blood pressure, diabetes, rheumatism, asthma, and heart problems.[138] According to the head of the Mitrovica hospital, "Even though these problems are quite common in Kosovo, and it would require scientific studies to say something authoritative, these problems are more aggravated in the case of Roma IDPs from the camps simply because of the living conditions they are in (low temperatures, high moisture), poor diet, less frequent medical visits and examination, and the physical work they do."[139] Basic medical services for the population in Cesmin Lug are supposed to be met by the ambulanta located beside the camp and serving Cesmin Lug and Osterode. The Roma IDPs complained to Human Rights Watch that the ambulanta suffers from a chronic lack of medicine,[140] although a nurse who staffs the ambulanta (with whom Human Rights Watch subsequently spoke by phone) rejected this.[141]

The majority of Cesmin Lug residents are holders of a "health book" issued by the Serbian government, which entitles them to free-of-charge treatment in the hospitals in north Mitrovica (but not medicine). All interlocutors Human Rights Watch spoke to in Cesmin Lug reported having free access to hospital when needed.[142]

Latif Musurica told Human Rights Watch that the camp children experience all kinds of serious health problems, which he attributed directly or indirectly to lead contamination. According to him, children often are "nervous, even hysterical, they have diarrhea all the time and wounds on their head." During the winter season, they are "the first ones to catch pneumonia."[143] Medical literature explicitly links lead contamination with hyperactivity and impulsive behavior;[144]the rest of the symptoms mentioned are not explicitly linked to lead in medical literature. However, according to a local Serbian doctor Human Rights Watch spoke to, skin diseases are widespread among Roma children due to poor hygiene, and they have overall weakening of their immune systems due to their difficult living conditions.[145]

Osterode

Human Rights Watch visited the Osterode camp in November 2008. Located just next to the Cesmin Lug camp, Osterode currently hosts around 500 people (around 105 families).[146] The Osterode site used to belong to KFOR, which moved its staff from there by the beginning of 2005. According to Habib Hajdini, the Osterode camp leader, this was due to its having tested high for lead levels and being deemed unacceptably hazardous for KFOR personnel.[147]

Human Rights Watch contacted KFOR to enquire about this allegation. On April 6, 2009, we received KFOR's reply, in which it stated that the agreement between the French Ministry of Defense and UNMIK (on the basis of which the transfer of grounds, buildings, and other real estate took place) "did not mention any reasons for removing KFOR troops from Osterode."[148]

Osterode was selected by the multi-agency task force created by UNMIK in 2005 as the transition place for the Roma Mahalla return project, despite concerns among displaced Roma that the level of lead exposure is as high there as it is in Cesmin Lug.[149]Notwithstanding claims by UNMIK and WHO that testing has shown that it is "lead safer" than Cesmin Lug (see Chapter V), common sense would suggest that a site located in a similar vicinity to the Trepca toxic slag heaps as Cesmin Lug would present similar health risks.

Javorka Jovanovic, a nurse working in the ambulanta located beside Osterode camp, told Human Rights Watch that in most cases of health problems she deals with every day, it is impossible to distinguish between purely lead-related medical complaints and those simply linked to poverty and deprivation, as they "go together and make each other worse." She pointed out, however, that she observes some lead contamination symptoms in children on a daily basis, such as stunted growth, nervousness, fatigue, or epilepsy, and the children are more vulnerable to other diseases and epidemics (there was a large-scale chickenpox outbreak in the camps at the time of our conversation with the nurse). She suggested that the children's health conditions are made worse "because their diet is only bread and tea, they are constantly cold, and do not have running water, soap and shampoo to wash themselves or their clothes."[150] A mother from the Osterode camp similarly complained about the poor hygiene and diet, which in her opinion exacerbated the health conditions in the camp, especially among the children.[151] Jovanovic said the concentration of illnesses in the camps makes the medical situation unparalleled to "anything else I have seen."[152]

According to the Osterode camp leader, Habib Hajdini, the biggest problem in the camp is the health situation of its residents. He asserts that the stunted physical and mental growth of children is evidence of dangerous effects of the lead contamination there.[153] Medical research offers plenty of evidence for a connection between lead exposure and intellectual deficits. For example, a 2004 study of Karin Koller et al. found an inverse association between blood lead levels and cognitive function in children exposed to low levels of lead and concluded that there is no safety margin for such exposure.[154] And although no comprehensive research has been done on this issue, Human Rights Watch made a general observation in all the camps visited, as well as the Mahalla, that the children seem thin, pale, and fragile-looking.

According to Habib Hajdini, the children from the camp attend (Serbian) schools "without any problem" and people get admitted in the (north) Mitrovica hospital "when they need something."[155]

The living conditions in Osterode are better than in Cesmin Lug (most people live either in small flats or barracks and have access to running water in their households). But the electricity goes on and off the same way as in Cesmin Lug. One of the camp residents Human Rights Watch spoke to complained that tap water (heated by electricity) is "never warm enough" in the wintertime.[156] Men in Osterode, as in other camps, support their families by daily labor (jobs in the Serbian areas, or collecting garbage and scrap metal to sell),[157] while women stay home to take care of children and household. All Osterode camp inhabitants are welfare recipients from the Serb-controlled (north) Mitrovica municipality administration.

Human Rights Watch spoke to an Ashkali family of five currently residing in one of the flats in the Osterode camp. They had been forcibly returned to Kosovo from Germany in 2006. They complained about the lack of free medicine, giving the example of their daughter's contracting hepatitis in 2007-having to pay for the medication nearly ruined them. They also complained that nobody from any institutions had assisted them upon their return, and that they had to rely on "good hearted people, acting in their individual capacity," to provide them in the beginning with some mattresses and food.[158]

Leposavic