I. Summary

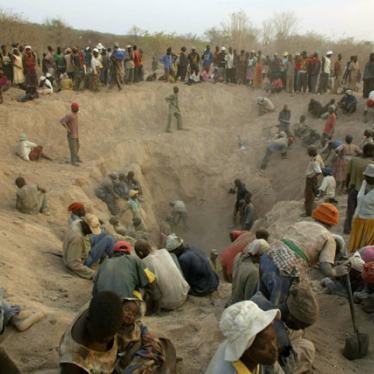

Zimbabwe's armed forces, under the control of President Robert Mugabe's Zimbabwe African National Union–Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF), are engaging in forced labor of children and adults and are torturing and beating local villagers on the diamond fields of Marange district. The military seized control of these diamond fields in eastern Zimbabwe after killing more than 200 people in Chiadzwa, a previously peaceful but impoverished part of Marange, in late October 2008. With the complicity of ZANU-PF, Marange has become a zone of lawlessness and impunity, a microcosm of the chaos and desperation that currently pervade Zimbabwe.

The military's violent takeover of the Marange diamond fields in October 2008 occurred one month after ZANU-PF agreed to share power with the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC), the opposition party that won the March 2008 elections. The contested vote precipitated a political crisis and period of rampant human rights abuses by ZANU-PF against members of the opposition.[1] The seizure of the diamond fields took place amidst a major economic crisis in Zimbabwe, caused largely by the failed policies of ZANU-PF, which resulted in astronomical inflation, rampant unemployment, the unchecked spread of disease, and massive food insecurity.

In this context, army brigades have been rotated into Marange to ensure that key front-line units have an opportunity to benefit from the diamond trade. Soldiers have bullied and threatened miners and other civilians into forming syndicates so that the soldiers can control diamond mining and trade in Marange. The enrichment of soldiers serves to mollify a constituency whose loyalty to ZANU-PF, in the context of ongoing political strife, is essential. The deployment of the military in Marange also ensures access to mining revenue by senior members of ZANU-PF and the army. Human Rights Watch believes that money from illegal diamond trading is likely to be a significant source of revenue for senior figures in ZANU-PF, which has either failed to or decided not to effectively regulate the diamond fields while exploiting the absence of clear legal ownership of the gemstones.

Diamonds were discovered in Marange in June 2006, and ZANU-PF effectively encouraged a diamond rush by declaring the fields open to anyone to mine. By November 2006, however, a nationwide police operation was launched to clamp down on illegal mining across the country, including in Marange. Police assumed control of the diamond fields; but, rather than halt illegal mining and trade, they exacerbated and exploited the lawlessness on the fields. Police officers were responsible for serious abuses-including killings, torture, beatings, and harassment-often by so-called "reaction teams" deployed to drive out illegal miners. Miners described colleagues being buried alive. A police officer working with a reaction team told Human Rights Watch of orders from senior officers to "shoot on sight" miners found in the fields. Villagers described arbitrary arrests, beatings, and harassment that by May 2008 had swamped a local prison with 1,600 prisoners, 1,300 more than its capacity.

With policing disintegrating into anarchy, the army operation called Operation Hakudzokwi (No Return), which started on October 27, 2008, appears to have been designed both to restore a degree of order and to allow key army units access to riches at a time when inflation in Zimbabwe was astronomically high and the country teetered on the verge of bankruptcy. Military operations over a three-week period involved indiscriminate fire against miners at work and people in their villages. Between November 1 and November 12, 107 bodies, many with visible bullet wounds, were brought from Marange to the morgue at Mutare Hospital. Overcrowded, the hospital eventually had to turn away trucks carrying more bodies. One man described to Human Rights Watch the extrajudicial execution of his brother on November 14-shot in the back of the head by soldiers who had accused him of being an illegal miner. Scores of miners and diamond traders were tortured and beaten, and at least 80 villagers from Muchena were beaten by soldiers demanding to know the identities and whereabouts of local illegal miners.

With control established, the army rapidly turned to forming syndicates, often using forced labor, including of children. A miner described to Human Rights Watch how his syndicate was cheated by the soldiers who formed it-when the men decided to abandon work, soldiers shot them, leading to the death of one man and the maiming of another. Children describe being made to carry diamond ore, working up to 11 hours per day with no reward. One local lawyer has estimated that up to 300 children continue to work for soldiers in the diamond fields.

While Zimbabwe's new power-sharing government, formed in February 2009, now lobbies the world for development aid, millions of dollars in potential government revenue are being siphoned off through illegal diamond mining, smuggling of gemstones outside the country, and corruption. The new government could generate significant amounts of revenue from the diamonds, perhaps as much as US$200 million per month, if Marange and other mining centers were managed in a transparent and accountable manner. This revenue could fund a significant portion of the new government's economic recovery program, which would benefit ordinary villagers like the residents of Marange.

Human Rights Watch calls on the power-sharing government of Zimbabwe to remove the military from Marange, restore security responsibilities to the police, and ensure that the police abide by internationally recognized standards of law enforcement and the use of lethal force. The power-sharing government should appoint a local police oversight committee consisting of all relevant stakeholders, launch an impartial and independent investigation into the serious human rights abuses committed there, and hold accountable all those found to be responsible for abuses. Members of the army and police who have committed abuses should also face disciplinary action for their crimes. The new Zimbabwe government should strengthen resource accountability by allowing greater transparency in how mining revenues are derived, permitting public scrutiny of the allocation of that revenue, and protecting the basic civil and political, as well as economic and social, rights of its citizens.

As a formal participant in the Kimberley Process Certification Scheme (KPCS)-an international scheme governing the global diamond industry-Zimbabwe has a responsibility to immediately end the smuggling, corruption, and abuses that are taking place in Marange and ensure effective internal control over its diamond industry. Members of the KPCS should demand that Zimbabwe comply with the scheme's minimum standards, which include stopping the smuggling of diamonds from Zimbabwe, bringing Marange diamond fields under effective legal control, and ensuring that all diamonds from Marange are lawfully mined, documented, and exported with relevant valid Kimberley Process (KP) certificates. The KPCS should take urgent measures to audit the Zimbabwean mining sector, ensure that individuals involved in smuggling return their ill-gotten gains, and act to prevent any further abuse in both the extraction and onward sales of Marange diamonds.

The Kimberley Process emerged out of a concern that rebel groups in West Africa in the 1990s were engaged in the mining and trade of conflict diamonds, which provided the groups with revenue and permitted them to commit abuses against civilians. Human rights concerns are implicit in the KPCS mandate, but that mandate has been too narrowly construed by its members. Human Rights Watch calls on the KPCS to broaden its remit to include serious and systematic abuses, not only by rebel groups in conflict, but also by other agencies, including governmental bodies. The abuses committed by Zimbabwe's police and army did not occur in armed conflict, but they are as serious as those the Kimberley Process was designed to address; for that reason, KPCS members should classify Marange diamonds as "conflict diamonds."

Human Rights Watch recommends that the KPCS suspend Zimbabwe from participation in the Kimberley Process on account of the horrific human rights abuses in Marange and the lack of effective official Zimbabwean oversight of its diamond industry. It should also place an immediate, temporary halt on the extraction and trade of Marange diamonds. The KPCS should bar Zimbabwe from exporting Marange diamonds and ban the importation of Marange diamonds by its members until the government of Zimbabwe has ended human rights abuses in Marange and has regulated the diamond fields in ways that stop smuggling. Regulation of the diamond fields should include settling the question of legal title and ensuring that only those properly licensed are allowed to mine diamonds.

Finally, as a member of the KPCS and as a regional political power, South Africa also has an important role to play. Its own huge diamond industry is at serious risk of being tainted if illegal diamonds from Marange are indeed being sold alongside South Africa's domestically produced diamonds. Human Rights Watch calls on South Africa, both individually and as a member of the KPCS, to prevent the entry of tainted precious stones from Zimbabwe and to encourage the transparency and accountability of Zimbabwe's diamond industry.

II. Recommendations

To the Government of Zimbabwe

- Immediately end all human rights abuses in the Marange diamond fields, including killings, beatings, forced labor, child labor, and torture.

- Remove the army from Marange district, demilitarize the diamond industry, and restore security responsibilities to the police, but ensure that the police abide by international law enforcement standards governing use of lethal force and illegal searches. Further to this, the government of Zimbabwe should, set up a local police oversight committee to monitor police compliance with basic human rights and international law enforcement standards.

- Launch an impartial and independent investigation into alleged human rights abuses, smuggling of diamonds, and corruption. Hold accountable all soldiers and police implicated in these abuses, irrespective of their seniority.

- End diamond smuggling, urgently resolve the outstanding legal questions of control and title to the Marange diamond fields, and ensure that only licensed miners are permitted to mine and that all buyers of diamonds are properly licensed in compliance with the requirements of the Kimberley Process Certification Scheme.

- Fully cooperate with KPCS investigation teams or review missions and ensure full compliance with KPCS rules and requirements.

- Put in place mechanisms to ensure greater revenue transparency from diamond mining and ensure that the Marange community benefits directly from the mining of diamonds in their area. This may be achieved by regularizing diamond mining to stem smuggling, licensing local miners, taxing them, and redistributing a portion of their revenue to the local community.

- Ensure that, in the event that relocation of the local community around the diamond fields is found to be necessary and in the public interest, based on thorough consultation with affected communities, such relocation fully complies with national and international human rights standards.

To the Government of South Africa

- Actively support calls for a broader inclusion of human rights in the mandate of the KPCS to ensure that any systematic human rights violations in the diamond industry of a KPCS participant result in that country's suspension and ultimate expulsion from the KPCS.

- As a member of the KPCS, and as chair of the Southern African Development Community (SADC), press for speedy reforms and policy changes that will stop the export of smuggled diamonds from Marange due to the serious human rights abuses involved. Urge Zimbabwe to comply with KPCS rules, including stopping all smuggling of Marange diamonds and ensuring that all diamonds that leave Zimbabwe are accompanied by authentic KPCS certificates.

- Ensure that South Africa's diamond industry is not tainted by diamonds from Marange and the human rights abuses taking place there. In this regard, exercise greater vigilance through the use of the KPCS "footprint"-a detailed description highlighting distinctive features-of smuggled Marange diamonds that would enable South Africa to more easily identify diamonds originating from Marange and stop them from entering its diamond market. South Africa should ensure that all diamonds imported and exported within its territory are accompanied by valid Kimberley Process certificates.

To the Kimberley Process Certification Scheme

- Immediately investigate allegations of serious human rights abuses and smuggling of Marange diamonds outside Zimbabwe and any other violations of the Kimberley Process.

- Immediately suspend Zimbabwe from participation in the KPCS until it satisfactorily addresses the violations set out in this report and puts in place genuinely effective and transparent measures to regulate its diamond industry, stop human rights abuses, and end smuggling.

- Urgently review and broaden the definition of "conflict diamonds" or "blood diamonds" to include diamonds mined in the context of serious and systematic human rights abuses and develop an actionable response to KPCS members that commit these violations.

To States and Organizations that Are Major Consumers of Rough Diamonds, including the European Union, the United States, South Africa, the United Arab Emirates, and India

- Support initiatives to speedily reform and broaden the mandate of the KPCS to include human rights concerns at the core of its mandate.

- Highlight the human rights abuses occurring with respect to diamond mining in Marange and require that these abuses end immediately and that there be full accountability for previous human rights violations, including prosecutions of those responsible for unlawful killings, torture, and other serious crimes.

- Support the suspension of Zimbabwe from the Kimberley Process until it rectifies rights abuses.

- Demand greater transparency and accountability on the origin of diamonds, including whether ZANU-PF is using diamond mining as a parallel source of revenue, which would undermine good governance, transparency, and accountability in the inclusive power-sharing government.

- Guard against the purchase of rough diamonds from Marange and exercise greater vigilance through the use of the KPCS "footprint" of Marange diamonds, which enables buyers to more easily identify diamonds originating from Marange.

- Take steps to inform consumers of polished diamonds that they should not buy, trade, or sell diamonds originating from sources in Marange, due to the serious human rights abuses taking place there.

To the Southern African Development Community

- Call upon the new government of Zimbabwe to ensure respect for human rights and the rule of law in the Marange diamond fields and across the country.

- Insist upon full accountability for perpetrators of human rights abuses in Marange and press for appropriate remedies for victims.

To International Donors, including the United States, the United Kingdom, and Other European Union Members

- Continue to press the government of Zimbabwe to investigate and prosecute all responsible for human rights abuses and end the prevailing culture of impunity.

- Urge the government of Zimbabwe to ensure wider accountability and restore the rule of law, not only in the Marange diamond fields but generally across Zimbabwe.

- Ensure that development aid to Zimbabwe is tied to clear progress in promoting respect for human rights and ensuring justice for victims of abuses. Donor nations should set specific benchmarks and closely monitor Zimbabwe's progress.

III. Methodology

This report is based on two research missions to Zimbabwe in February 2009. Human Rights Watch researchers visited Harare, Mutare, and the Marange diamond fields to document human rights violations associated with the mining of diamonds in the Chiadzwa area of Marange district. Human Rights Watch interviewed more than 100 people, including eyewitnesses, local miners, local government officials, court officials, local community leaders, victims and relatives, lawyers, medical staff, soldiers, police, traditional leaders, and local human rights activists.

Additional interviews were also conducted with representatives of organizations such as Zimbabwe Lawyers for Human Rights, Zimbabwe Human Rights NGO Forum, Centre for Research and Development, Zimbabwe Environmental Law Association, and Mutare Legal Practitioners Association, as well as with Western diplomats based in Harare. Also interviewed were officials from the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe, Zimbabwe Mining Development Corporation, and African Consolidated Resources. Human Rights Watch conducted all interviews one-on-one.

Human Rights Watch researchers supplemented their field research with telephone interviews with representatives of international organizations working in the area of extractive industries and human rights and reviewed legislation and policy documents, court documents, newspaper articles, and reports on the Marange diamond fields and associated human rights violations.

For security reasons, many people spoke to Human Rights Watch on the condition of confidentiality, requesting that the report not mention their names or other identifying information. Details about individuals and locations of interviews when information could place a person at risk have been withheld.

Map of Zimbabwe and the Marange Diamond Fields

© 2009 John Emerson

Glossary of Acronyms

ACR |

African Consolidated Resources Private Limited Company |

AFZ |

Air Force of Zimbabwe |

CIO |

Central Intelligence Organisation |

EPO |

Exclusive Prospecting Order |

ICESR |

International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights |

KPCS |

Kimberley Process Certification Scheme |

KPWGM |

Kimberley Process Working Group on Monitoring |

MDC |

Movement for Democratic Change |

MID |

Military Intelligence Department |

MLPA |

Mutare Legal Practitioners Association |

MMCZ |

Minerals Marketing Corporation of Zimbabwe |

PSTA |

Precious Stones Trade Act |

RBZ |

Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe |

SADC |

Southern African Development Community |

ZANU-PF |

Zimbabwe African National Union–Patriotic Front |

ZEC |

Zimbabwe Electoral Commission |

ZELA |

Zimbabwe Environmental Law Association |

ZMDC |

Zimbabwe Mining Development Corporation |

IV. Background

ZANU-PF under President Robert Mugabe has ruled Zimbabwe as a de facto one-party state since the country's formal independence from colonial rule in 1980. As recent Human Rights Watch reports have shown, the government has suppressed political dissent, and has detained, tortured, or killed scores of people belonging to or supporting the opposition Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) party. Following its first parliamentary defeat in March 2008, ZANU-PF and its allies unleashed violence on MDC supporters ahead of a presidential run-off election, killing at least 163 MDC activists and injuring or displacing from their homes thousands more.[2] After MDC presidential candidate Morgan Tsvangirai pulled out of the run-off, the Zimbabwe Electoral Commission (ZEC) controversially declared Robert Mugabe the winner, triggering a political and governance crisis that was only resolved by the formation of an inclusive government in February 2009 in which Morgan Tsvangirai agreed to become prime minister and accept Robert Mugabe as president in a power-sharing agreement.

Over the past several years, the government has plunged Zimbabwe into economic crisis, characterized by 80 percent unemployment and severe hyper-inflation. ZANU-PF's land-grab policies have triggered the collapse of the agricultural sector, along with the country's diversified manufacturing and tourism sectors.[3] By the end of 2008, the government was increasingly unable to pay its civil servants and middle- and low-ranking soldiers. The disastrous humanitarian situation included a cholera outbreak that erupted in August 2008 and infected close to 100,000 people and claimed more than 4,200 lives; a public health system that has collapsed; and three-quarters of the population who are now in need of food aid.[4] With the assistance of the World Health Organization and its Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network, the power-sharing government of Zimbabwe appears to have brought cholera under control, with the numbers of reported new cases and fatalities significantly decreasing.[5]

To shore up its power, ZANU-PF since 2000 has relied upon a patronage system to reward and retain the loyalty of the military. Former and sitting military officers have been appointed as ministerial permanent secretaries, directors in ministerial departments, provincial governors, and other key posts.[6] Because of its need for revenue, ZANU-PF in government has tried to increase its influence and control over the mining industry, which accounted for 40 percent of Zimbabwe's exports in 2008.[7] It has also sought to placate its popular base by demonstrating an effort to manage the country's resources. On March 7, 2008, three weeks before national elections, President Mugabe signed into law the Indigenization and Economic Empowerment Act, which requires all public companies to be 51 percent owned by "indigenous" Zimbabweans.

Diamonds in Marange-Unclear Legal Title to the Fields

In June 2006 villagers discovered diamonds in the Chiadzwa area of Marange district, which geologists estimate to be spread over a 26-square-kilometer area.[8] The diamond fields are commonly referred to as the Marange diamond fields. Chiadzwa is a remote, dry, and hilly area comprising some 30 villages that are divided into two administrative wards (Mukwada, ward 29 and Chiadzwa, ward 30). The combined population of the two wards is estimated to be 20,000.[9] The nearest city, 100 kilometers to the northeast, is Mutare, the provincial capital of Manicaland; and to the south, the nearest town is Birchenough Bridge, about 60 kilometers away. Diamond mining is concentrated at the foot of Shonje hills, over a sparsely populated 13 square kilometers.[10]

The Marange diamond fields brought the number of diamond sites in Zimbabwe to three.[11] The other two sites-River Ranch and Murowa diamond mines-are deep mines exploited by private commercial enterprises. The discovery of a third diamond field raised the potential for the mining industry to generate further much-needed revenue for Zimbabwe.[12] Many in the local community initially viewed the discovery as a godsend that would cushion them from Zimbabwe's increasingly harsh economic crisis.[13]

Initially, the government's plan was for the Marange fields to be developed privately. From March 2002 to March 2006, Kimberlitic Searches, a subsidiary of South African diamond conglomerate De Beers Company, operated under two "Exclusive Prospecting Orders" (EPO 1520 and 1523) from the government of Zimbabwe, granting it full exploration rights to search for minerals in the Marange communal area.[14] The exploration certificates expired on March 28, 2006, and De Beers did not renew them.[15] After Kimberlitic Searches ended its operations, a United Kingdom-registered company, African Consolidated Resources (ACR), through its four Zimbabwean subsidiaries, registered exploration claims over Marange diamond fields with relevant authorities.[16] The claims gave ACR exclusive rights to explore and search for diamonds and other precious stones in Marange district.

At the time that Marange diamonds were discovered in June 2006, ownership of exploration rights over Marange diamond fields was vested in ACR. But the government moved quickly to "cancel" ACR's legal title and rights on the grounds that they had been improperly conferred to ACR in the first place. Police forcibly removed and barred ACR staff from accessing the diamond fields despite a magistrate's order directing the police not to interfere with ACR rights and operations.[17]

The minister of mines, Amos Midzi, then granted exclusive mining and exploration rights in Marange to a state-owned company, the Zimbabwe Mining Development Corporation (ZMDC).[18] Zimbabwean authorities explained that the purpose of granting the ZMDC prospecting and mining rights was to restore order to Marange following the diamond rush that ensued shortly after the discovery of the gems.[19] In February 2007 President Robert Mugabe publicly announced the government's intention to take over the mining of diamonds in Zimbabwe when he said, "Only government will mine diamonds."[20]

Illegal Mining and Smuggling in the Marange Diamond Fields

The government effectively fostered the diamond rush at Marange. In an apparent attempt to get political mileage from the discovery, ZANU-PF authorities in June 2006 declared the diamond fields free and open to anyone wishing to look for diamonds. From July 2006, a diamond rush began, with thousands of people from other parts of Marange district, other parts of Zimbabwe, and other countries scrambling for the precious stones. The Minerals Marketing Corporation of Zimbabwe (MMCZ), the sole licensed buyer of diamonds until January 2009 when it was replaced by the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe (RBZ), appears to have encouraged the view that the government tolerated illegal mining by purchasing diamonds from unlicensed local miners, in violation of the Precious Stones Trade Act. On September 25, 2006, Deputy Mines Minister Tinos Rusere addressed local miners in Chiadzwa and told them to continue mining and selling their diamonds to the government.[21]

Most diamond miners were Zimbabweans from outside Marange district-from impoverished high-density suburbs of Mutare, such as Chikanga and Dangamvura, or from Harare, Bulawayo, Kwekwe, and other Zimbabwean municipalities. Those who flocked to Zimbabwe to dig for or to buy diamonds also came from as far as South Africa, Botswana, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Mozambique, Equatorial Guinea, Nigeria, Lebanon, Pakistan, the United Arab Emirates, Belgium, and India.[22] When the scramble peaked in October 2008, more than 35,000 people were either mining or buying diamonds in Marange.[23]

Principal Buyers and Smuggling Routes

Human Rights Watch was not able to fully pursue the global chain of purchase of diamonds from Marange, but Human Rights Watch's research suggests that the majority of Marange diamonds have been smuggled out of the country via Mozambique, South Africa, and Harare international airport, and then shipped to Lebanon, the United Arab Emirates, India, Pakistan, and Europe, among other destinations.

The buyers of Marange diamonds fall into two categories:

- "Agents" or middlemen (mostly Zimbabweans) who travel to the diamond fields to buy diamonds from individual miners, syndicates, or others on behalf of principal buyers;

- Principal buyers themselves (known as "barons"), often based in Mutare, Harare, Mozambique, or South Africa. These buyers, who often enjoy political, military, police, or other official patronage, in turn sell the diamonds to other buyers in the international community.[24]

One middleman told Human Rights Watch that he often travelled to Mozambique to sell diamonds to different foreign buyers based there.[25] Another middleman told Human Rights Watch that he would make weekly trips to sell Marange diamonds to buyers based in Johannesburg, South Africa. He told Human Rights Watch:

Diamonds are easy to smuggle because of the very high concentration of value in very small stones that does not set off metal detectors. Often l would hide my stones in toothpaste, or shaving cream, or under my car seat, or in my belt. When l had a high value gem, from 15 carats, l would swallow it and then retrieve it later.[26]

According to miners who spoke to Human Rights Watch, diamonds were not always exchanged for cash; sometimes the diamonds exchanged hands for clothes, cars, food, sex, mobile phones, or marijuana.[27] At times, foreign smugglers without middlemen travelled to Marange to buy diamonds directly from the miners. Scores of homes in the district have been rented to foreign nationals with connections to diamond mining.[28]

As early as September 2006 Zimbabwe authorities had acknowledged that the smuggling of Marange diamonds had become a serious problem. Soon after, the Ministry of Mines directed the MMCZ to "mop up all diamonds in Marange and reduce the quantity of diamonds that were illegally leaving the country."[29] From October 2006 the MMCZ moved into Marange and began trying to purchase diamonds from illegal, unlicensed local miners.[30] But MMCZ officials only added to the number of middlemen operating. They paid out token cash sums as incentives to get miners to hand in stones that they had extracted and to stop them from trading with foreigners or smuggling the gems.[31] But the MMCZ offered prices that were far below market value and much lower than those offered by foreign smugglers, so their interventions failed to halt smuggling and illicit trading.[32]

Although geologists have not yet scientifically estimated the value of the Marange diamond fields, the governor of the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe, Gideon Gono, on various occasions has estimated that, if properly managed, Marange diamonds have the potential to earn the government US$1.2 billion per year in revenue.[33]

Laws Governing the Diamond Industry in Zimbabwe and Applicable International Standards

Zimbabwe's Mines and Minerals Act, 1961 (Chapter 21:05), colonial-era legislation that has been amended and remains in effect today, vests all the country's mining and mineral rights in the president and prescribes ways by which such rights can be acquired by individuals and corporate entities. The act provides that any person may apply for a prospecting license, "Exclusive Prospecting Order" (EPO), with any mining commissioner. The prospecting license or EPO grants the holder the rights to prospect and search for any minerals on land open to prospecting, but not to remove or dispose of any minerals discovered.[34] A holder of a prospecting license or EPO is not permitted to mine for minerals; once a discovery of minerals is made it must be registered as a mining location for which a mining lease or a special grants license must then be secured to permit lawful mining.[35]

The Precious Stones Trade Act (PSTA), 1978 (Chapter 21:06) regulates the possession of and dealing in precious stones, which include rough or uncut diamonds, rough or uncut emeralds, and, following amendment of the PSTA in November 2007, industrial diamonds. The act prohibits any person from buying, selling, bartering, exchanging, giving, receiving, or possessing precious stones unless such person is licensed or holds a permit. A licensed dealer or permit holder is only permitted to deal in precious stones with persons permitted by law to be in possession of precious stones, that is, only with registered miners.[36] Under the act, it is unlawful for a licensed dealer to buy precious stones from illegal sources, including from unlicensed local miners.[37]

Zimbabwe ratified the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights in 1986, which, among its many provisions, requires states to protect the right to life (article 4) and property (article 14). Article 5 of the charter states:

Every individual shall have the right to the respect of the dignity inherent in a human being and to the recognition of his legal status. All forms of exploitation and degradation of man, particularly slavery, torture, cruel, inhuman or degrading punishment and treatment shall be prohibited.[38]

Zimbabwe ratified the United Nations International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) whose article 11 states that parties to it accept the right of everyone to an adequate standard of living for himself and his family, including the continuous improvement of living conditions and prohibition of forced eviction.[39] On August 27, 1998, Zimbabwe ratified International Labour Organisation (ILO) Convention Number 29, prohibiting forced or compulsory labor. Furthermore, on December 11, 2000, Zimbabwe ratified the ILO's Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention (1999).[40]

V. Human Rights Abuses, Corruption, and Extortion by the Police (November 2006 to October 2008)

On November 21, 2006, five months after the discovery of diamonds in Marange, the government launched a nationwide police operation code-named Chikorokoza Chapera (End to Illegal Panning), which was aimed at stopping illegal mining across the country, including in Marange. During the operation, police deployed some 600 police officers, arrested about 22,500 persons nationwide who it said were illegal miners (some 9,000 of them were arrested in Marange), and seized gems and minerals with an estimate total value of US$7 million.[41]

The operation was marked by human rights abuses by the police, as well as corruption, extortion, and the smuggling of diamonds. Police coerced local miners to join syndicates that would provide the police with revenue from the sales of diamonds that the miners found. In seeking to end illegal mining and maintain control of the fields, police engaged in killings, torture, beatings, and harassment of local miners in Marange, particularly when police "reaction teams" carried out raids to drive local miners from the diamond fields.

Corruption in Marange

Over the 100-kilometer stretch of road from Mutare to Marange, police set up at least 11 permanent checkpoints to restrict access to Marange district and searched all persons travelling to and from Chiadzwa for precious stones.[42] Some local people interviewed by Human Rights Watch stated that they believed these restrictions were an attempt by the police to allow access to the fields only to those willing to pay off police officers.[43] They said that time allowed on the fields also depended on how much one paid the police: the bigger the bribe, the more time one was allowed. Those able to pay bigger bribes went in first.[44]

The security checkpoints and guard posts soon became de facto payment points where miners would bribe police to gain access to the fields and pay an exit fee on their way out.[45] Initially the police demands were modest, and often the bribes paid were small. According to one miner who spoke to Human Rights Watch:

When the police started guarding the diamond fields in Chiadzwa, we could easily bribe them. At the end of 2006, we used to gain access to the fields simply by giving the police a pack of cigarettes, a can of beer or mutsege (roasted nuts). At one time we even devised a plan with three gwejelines (women) in my team where the women had sex with the six police on guard and, while they attended to the police, we were digging for diamonds.[46]

With time, the police began to charge more. At each checkpoint, police began to extort payments of at least US$5, or the equivalent in South African rand, for miners to proceed onwards. A miner who first went to Chiadzwa in September 2007 told Human Rights Watch:

Although police usually demanded US$5 at checkpoints, the bribes would increase as one got closer to the field. We paid the largest bribes to police stationed at the edge of, or inside the diamond fields. For middlemen sometimes the bribes could be as much as US$100 to access the diamond fields.[47]

Another miner told Human Rights Watch that the police would not turn people away if they did not have the required fee; they just gave preference to those with the correct fee and gave them more time on the fields. Those with insufficient amounts would be allowed a very short period of time, sometimes only 20 minutes on the field.[48]

One local miner explained the working relationship with the police:

In the evening we would approach the police and say, "We want to work the fields tonight." The police would then tell us if it was fine... [and] they would tell us to pay them for access to the fields. When it was time for us to leave the field, the police often fired shots in the air, and we would stop working and leave the field with bags of ore on our backs. We would pay a bribe to leave the field with the ore.[49]

The police were in full control, but seemed to deliberately let illegal mining and trading activities thrive, while seeking to profit from them.[50]

In an internal police memorandum dated September 18, 2007, obtained by Human Rights Watch, Police Spokesperson Chief Superintendent Oliver Mandipaka stated that police officers stationed in Chiadzwa were engaged in corruption and that many were actively soliciting and receiving varying sums of cash from local miners in exchange for access to diamond fields. The memorandum noted:

Following corruption where members of the police force received varying amounts of money from illegal diamond diggers (magweja)-17 constables, sergeants, and an assistant inspector were charged, convicted, and sentenced under the Police Act. They were all dismissed from the force. A further 11 officers facing corruption charges under the Police Act (omitting or neglecting to perform any duty or performing any duty in an improper manner)have since been relieved of their duties.[51]

Human Rights Watch found, however, that disciplinary action and prosecutions of police officers were highly selective and inconsistent.

Police Smuggling Syndicates

To guarantee for themselves a cut of the diamond revenue, police officers formed "syndicates" with local miners. A syndicate was a group of miners that operated under the direct control of members of the police. Groups of between two and five police officers would partner with a large group of local miners under a loose arrangement where police provided the local miners security and escort in the fields in return for a share of proceeds from selling any diamonds the local miners found. A syndicate run by two members of the police could have as many as 30 local miners, and the two police officers could control several syndicates at a time. Some local miners, however, worked independently of police syndicates.[52]

A member of the Police Support Unit based in Manicaland told Human Rights Watch:

During the time I was based in Marange at the end of 2007, together with a colleague we controlled six syndicates with a combined total of 102 members. We would grant them access to the fields, and they would dig for diamonds while we guarded them and then hand over the diamonds to us to sell, and then we shared the proceeds equally, giving 50 percent to each side. My government salary for three months was less than US$5, but from the diamond business together with my colleague we made more than US$10,000 in three months.[53]

A police officer told Human Rights Watch how he was involved in illegal diamond smuggling with a foreign buyer in Marange:

It was obvious to me that the man was an illegal diamond buyer. He could not speak the local language [Shona], and he stated that he was a tourist. I then told him that it was clear he had an interest in diamonds and I offered to assist him, or alternatively arrest him on the spot on charges relating to illegal diamonds trade and take him to court to explain himself.

He then confessed that he had travelled from South Africa to buy diamonds on behalf of his principal, a well-known South African buyer. He said he was on his fifth trip to Marange to buy diamonds. We then agreed that he would buy diamonds only through me and that whenever he came to Marange, he would first contact me. I worked well with him, and now, although I have since left Marange, whenever he comes to buy diamonds, he first contacts me and I refer him to my trusted contacts in the police and army running syndicates in Marange at the moment.[54]

Several middlemen told Human Rights Watch that they worked for the same South African buyer.[55] For several months in 2008, they would travel once a week to Johannesburg, South Africa, to get "bags" of money from this same buyer and to give him diamonds.[56]

Another member of the police based in Harare told Human Rights Watch:

I started my first syndicate with local diamond miners after we had arrested eight of them at a checkpoint that I was manning with colleagues. For the three months that my team was based in Chiadzwa, we worked with the syndicate. And when it was time to leave Chiadzwa we handed over our syndicate to our colleagues who took over the guarding from us.[57]

One local miner told Human Rights Watch that joining a police syndicate was often involuntary; the only alternative was arrest:

In August 2008 we were caught by the police, 14 of us working in the diamond fields. They took us to their base at Chakohwa where 17 others were already detained. One policeman said to us, "Either you all become our syndicate and work for us, or we detain you and take you to court after several days of languishing and gnashing of teeth. The choice is yours." We all chose to be a syndicate for the police officers.[58]

Several members of the police as well as local miners told Human Rights Watch that police frequently coerced miners to join syndicates under police control. In November 2008 RBZ Governor Gono estimated that there were some 500 syndicates operating in Marange at any given time.[59]

Under Zimbabwean law, it is illegal for members of the police to run syndicates under the Police Act, which prohibits police from improperly using their position for private gain and from entering into any trade, business, or occupation while on duty.[60]Forcing local miners to join syndicates also violates Zimbabwe's obligations under the ILO Convention 29, which prohibits forced or compulsory labor.[61]

Killings by Police

From November 21, 2006, to the end of October 2008, police committed numerous human rights abuses, including killings, torture, beatings, and harassment of local miners in Marange. The bulk of the abuses occurred when police "reaction teams" carried out raids to drive local miners from the diamond fields. During "reaction team" raids, or when local miners entered the diamond fields without paying, some police officers used live ammunition to expel them. One local miner told Human Rights Watch how he and several others were violently forced off the fields by police in August 2008:

We had decided to go into the diamond fields without paying the police because we had run out of cash. We were digging in darkness when the police fired a searchlight into the sky, and the whole field was as bright as day. Then the police, about 30 of them, began to fire at us using Mossberg shotguns. Four of my colleagues were in a tunnel when the raid began and had no time to come out. Close to 200 miners were running in all directions.

The shallow tunnel where my colleagues were working collapsed and trapped them inside. There was nothing I could do to save them; I had to run for my own life. On that night, three people were shot by police and died on the field. The following morning, police ordered us to bury the three bodies in one of the pits on the field. When I asked to dig out my four colleagues, a police officer told me, "consider them already buried."[62]

According to several police officers interviewed by Human Rights Watch who took part in the operations, the senior police officer commanding Mutare Rural District (or DISPOL), Chief Superintendent O.C. Govo, was in charge of these operations.[63] The officers said that he told them on several occasions in 2008 to "shoot on sight" any local miners found in the diamond fields.[64] Another police officer who witnessed the killing of three local miners told Human Rights Watch:

At the end of August 2008, DISPOL Govo addressed us and said we were all too lenient with local miners. He then said he was going to show us how to deal decisively with local miners. Around 10 that night, he led us to a well-known camp of local miners in the hills. First he fired a searchlight into the air and then he began to shoot randomly at the sleeping miners.

I saw him shoot and kill three miners. Many others ran into the night. He told us to leave the bodies, saying the other miners who had run away would return to bury their dead.[65]

A 23-year-old man who was shot by the police in the diamond fields in October 2008 told Human Rights Watch:

Three policemen on horseback raided us while we worked in the diamond fields and immediately fired their shotguns at us. I was shot in the left thigh. A friend later took out four pellets from my left thigh where I was shot. Two of my friends were shot and killed during that raid.[66]

Arbitrary Arrests and Detentions

Police also routinely and arbitrarily arrested members of the local community in the area around the diamonds fields, often without any reasonable suspicion that a person was involved in illegal or unlicensed mining, prospecting, or trading.[67] Several villagers told Human Rights Watch that they were frequently subjected to beatings and harassment during the course of arrest and while in detention, which often was for between four and seven days in makeshift police camps on the diamond fields, before they were taken to Mutare remand prison for further detention and the court process. A former detainee, part of a large group of people detained in April 2008, described to Human Rights Watch how, after having been arrested while selling cigarettes and food at Chakohwa shopping center, he was detained for five days before being taken to court, charged with prospecting without licenses, and forced to pay "admission of guilt" fines before release.[68]

Several other villagers told Human Rights Watch that they were arrested indiscriminately, detained for at least four days, and taken to Mutare, where they were also ordered to pay "admission of guilt" fines for illegal prospecting, and then released.[69] One villager said:

I was arrested [for failure to produce an identification card] by three police constables patrolling in Chiadzwa in May 2008. I was taken to Chakohwa police base, where I joined about 30 other people detained there. We were all beaten on the soles of our feet using iron rods, and we were made to sing and dance. For six days we were in detention. The police gave us very little food. We were divided into three groups, one for cooking, the next for washing clothes and fetching water, and the last for general cleaning. On the seventh day, we were driven to Mutare, where we were all charged with illegal prospecting and fined and released.[70]

The mass arrests and detentions of suspected local miners and members of the local community soon filled Mutare remand prison beyond its 300-person capacity, to more than 1,600 inmates. Many were not fed, and those in detention slept outside in the open, but within the prison perimeter and under guard.[71] A member of the Mutare Legal Practitioners Association (MLPA), who was part of a team of lawyers that represented the villagers and diamond miners, told Human Rights Watch that in May 2008, the MLPA represented close to 1,000 individuals from Marange, including boys and girls as young as 10 years old, whom police had detained for well over the 48-hour limit set by law.

Scores of these villagers had dog-bite wounds.[72] A medical officer at a private hospital in Mutare told Human Rights Watch that in 2008 alone he had treated more than 200 victims with dog-bite wounds from Marange.[73] A victim of dog attacks under police guard told Human Rights Watch:

I was in the company of three other women; we had been fetching water at a village well. Two policemen with dogs stopped us and accused us of fetching water and cooking for miners and one police constable said, "We want to teach you a lesson never to assist illegal miners." He ordered us to kneel down and take off our blouses. We did and they both set their dogs on us. We all suffered dog bites on our breasts. After a few minutes the police told us that the dogs only eat human breast meat and let us go.[74]

Sexual Abuse and Exploitation

Women living on the diamond fields described to Human Rights Watch how they suffered sexual abuse and degrading treatment by the police. Three women who underwent degrading body searches by a police constable told Human Rights Watch how they were forced to strip naked at the 22-miles checkpoint between Mutare and Chiadzwa. After stripping, the male police officer searching them inserted his gloved finger in their private parts, probing, and claiming to be looking for hidden diamonds.[75]

Several other women told Human Rights Watch how some police officers stationed in Chiadzwa in 2008 would amuse themselves by fighting over women and gambling on them, with the victors winning the "prize," a chance to forcibly have sex with the women for the night. Some women also told Human Rights Watch that they volunteered sexual favors in return for access to the diamond fields or in exchange for diamonds.[76]

VI. Human Rights Abuses by the Zimbabwe Defence Forces (October 2008 to June 2009)

The Zimbabwe government's decision in October 2008 to deploy the Zimbabwe Defence Forces (ZDF)-which comprises the Zimbabwe National Army (ZNA) and the Air Force of Zimbabwe (AFZ)-to the Marange diamond fields appears to have been a response to the lawlessness and chaos in the fields and the police's inability to control it. It may also have been intended to end illegal mining or diamond smuggling by the police. Instead of creating law and order, however, Human Rights Watch found that the army has committed numerous and serious human rights violations, including extrajudicial killings, beatings, torture, forced labor, and child labor in Marange. The first three weeks of the operation were particularly brutal-over the period October 27 to November 16, 2008, the army killed at least 214 miners.[77] The army has also been engaged fully and openly in the smuggling of diamonds, thereby perpetuating the very crime it was deployed to prevent.

On Monday, October 27, 2008, elements of the Zimbabwe National Army, the Air Force of Zimbabwe, and Central Intelligence Organisation (CIO) agents from the Office of the President launched Operation Hakudzokwi (No Return) in Marange district. More than 800 soldiers drawn from three army units-Mechanized Brigade and No. 1 Commando Regiment based in Harare and the Kwekwe-based Fifth Brigade-carried out the operation under the overall command of Air Marshal Perence Shiri, commander of the AFZ, and General Constantine Chiwenga, commander of the ZDF.[78]

Under Zimbabwean law, the ZNA cannot undertake civilian operations, such as removing illegal miners from Chiadzwa and providing security at the diamond fields, without a formal request from the police commissioner general and authorization by the commander in chief of the Zimbabwe Defence Forces, President Mugabe.[79] The police made no such request. The legal authority or justification for the army's presence and operations in the diamond fields in Chiadzwa thus likely came with the knowledge and approval of Mugabe as commander in chief of the Zimbabwe Defence Forces.[80]

A military officer familiar with the planning of the operation told Human Rights Watch that an additional motivation for deploying the army was a plan by military intelligence to reward and appease an increasingly discontented army rank and file, who were poorly paid in the country's severe political, social, and economic crisis. He told Human Rights Watch:

Information from the Military Intelligence Department was that discontent in the army was a major threat to ZANU-PF's hold on power. Hundreds of soldiers were resigning... [or] deserting with their weapons. Initially, the military leadership issued orders that soldiers were required to turn in their weapons. Another measure was to require [the] notice period for any person resigning from the army to be [increased to] nine months instead of the standard three months.

Now the final strategy was to give the military direct access and control over [natural] resources. Some soldiers had been assigned to run Grain Marketing Board projects and RBZ's farm mechanization, but it was not enough. Marange diamonds presented another opportunity for the military to benefit.[81]

Four soldiers told Human Rights Watch that the incentive package came in two parts. Soldiers on mission in Marange would first get special allowances directly from the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe and then be offered a "once-in-a-lifetime" opportunity to benefit directly from diamond smuggling. The plan was for all army units to rotate and take turns to "guard" Marange's diamond fields and take the associated benefits.

At the time of writing this report, five army units had, on a rotational basis, been deployed to Marange: the Mechanized Brigade; No.1 Commando Regiment; Fifth Brigade; Masvingo-based 4 Brigade; and Mutare-based 3 Brigade.[82] When Human Rights Watch visited Marange in February 2009, the army unit on deployment was 4 Brigade from Masvingo. It has since been replaced by Mutare's 3 Brigade.[83]

A military officer who took part in Operation Hakudzokwi told Human Rights Watch that his regiment received a "signal" or directive from the Joint Operations Command ordering immediate deployment of his regiment to Marange for a "swift, ruthless, and secret" operation to permanently remove unlicensed local miners.[84]

Massacres in Chiadzwa (October 27 to November 16, 2008)

According to several soldiers and local miners, the operation began suddenly around 7 a.m. on October 27. Five military helicopters with mounted automatic rifles flew over Chiadzwa and began driving out local miners. On the ground, over 800 soldiers were ferried to Chiadzwa in seven large trucks, several smaller trucks, and an army bus. From the helicopters, soldiers indiscriminately fired live ammunition and tear gas into the diamond fields and into surrounding villages. One local miner who was caught up in the operation on the first day told Human Rights Watch:

I first heard the sound and then saw three helicopters above us in the field. I was not worried. I just assumed it was a team of buyers who had come for business in helicopters as they sometimes did. However, soldiers in the helicopters started firing live ammunition and tear gas at us. We all stopped digging and began to run towards the hills to hide. I noticed that there were many uniformed soldiers on foot pursuing us. From my syndicate, 14 miners were shot and killed that morning.[85]

According to several villagers who witnessed the operation, soldiers fired their AK-47 assault rifles indiscriminately, without giving any warning. In the panic, there was a stampede, and some miners were trapped and died in the structurally unsound and shallow tunnels. According to witnesses, soldiers searched the bodies of dead miners on the field and took all diamonds and any other valuables they found.[86]

During police raids, the miners would only be pursued off the fields but not to their bases in the hills. This military raid was different. One local miner told Human Rights Watch:

The soldiers pursued us into the hills. Together with about 10 other illegal miners, I ran to the hills. Unfortunately we ran into a group of soldiers who stopped us. The soldiers marched us at gun point back to the fields and ordered us to collect the bodies of dead miners whom they had shot.

We gathered 37 bodies and piled them in an army truck and took them to the edge of Nyazika village. There we found two more army trucks offloading 35 bodies. The soldiers then ordered us to dig a grave and bury the bodies. We buried 72 bodies in that grave.[87]

Another miner who took part in the digging of the mass grave told Human Rights Watch:

After burying the bodies we were all taken to an open area nearby and ordered to pitch tents for the soldiers. For a week we were detained by the soldiers who beat us and forced us to sing. They warned us never to talk about what had happened in Chiadzwa. After that we were released.[88]

The military operation continued every day for the next three weeks until November 16, 2008. Military helicopters would fire teargas and live ammunition from the air to support soldiers shooting at miners on the ground. The helicopters used in the operation were temporarily based in Mutare at 3 Brigade army base.[89] A Chiadzwa villager told Human Rights Watch:

On November 8, I discovered 22 decomposing bodies near Chiadzwa Dam. I reported the matter to my village headman. None of the dead were from my village. On the following day, we saw a group of soldiers in army uniform directing some miners using bulldozers to dig a mass grave. All the bodies were buried in that grave on November 9. It is possible they were bodies of diamond miners killed by soldiers.[90]

A local headman told Human Rights Watch that in the three weeks of the military operation, Chiadzwa resembled "a war zone in which soldiers killed people like flies."[91] Another headman was forced to bury five bodies of miners; all five bodies had what appeared to be bullet wounds.[92] None of the bodies were identifiable. A policeman operating in Marange explained that identification of bodies was impossible because often local miners would deliberately go to diamond fields without any form of identification in order to evade police and also because most bodies were discovered in advanced stages of decomposition.[93]

According to a medical officer based at Murambinda Hospital in Buhera:

On November 11 an army truck with seven uniformed and armed soldiers came from Marange with 17 bodies of people they said were illegal diamond miners. The bodies had bullet wounds and were decomposing. The soldiers ordered us to take the bodies and arrange for burial. All the bodies were unidentified and we entered their details as "unknown" and "brought in dead" from Marange.[94]

A villager from Muedzengwa in Chiadzwa who travelled to Murambinda hospital to collect the body of his brother killed by soldiers in the diamond fields told Human Rights Watch:

I travelled to Murambinda after a sympathetic member of the police had told me soldiers had taken my brother's body to Murambinda Hospital. At the hospital I had difficulty identifying my brother's body because he was in a pile of bodies heaped on the floor of the mortuary. I saw several bodies that I suspect were of other diamond miners also killed in the operation.[95]

As the military operation continued, soldiers also began to take bodies of dead miners to Mutare General Hospital, where the bodies were soon piling up in the mortuary there. Medical staff at the hospital told Human Rights Watch:

Army trucks made several trips to this hospital in the first three weeks of November 2008 bringing dead bodies to the mortuary. Between November 1 and November 12, soldiers had brought in 107 bodies from Marange, of which 29 bodies were identified and collected by relatives. 78 bodies we marked "Brought in Dead" (B.I.D) from Marange, identity unknown. We entered cause of death as unknown although many of the bodies had visible bullet wounds. The soldiers who brought them in informed us that the bodies were of unknown illegal diamond miners killed in Marange.

Our mortuary has a maximum capacity of 38 bodies only, so it was extremely overcrowded. We were forced to pile the bodies on the floor. From our hospital patients, five people died due to cholera, bringing the total number of bodies in the mortuary to 83. We could not take in any more bodies, so we started turning away military trucks that brought in dead bodies. On one occasion we turned away a military truck with several bodies. The soldiers told us they would take the bodies to mortuaries in Harare and Chitungwiza.[96]

The 83 bodies were later buried in two mass graves at Dangamvura Cemetery in Mutare on December 19, 2008.[97] On February 19, Human Rights Watch researchers visited Mutare's Dangamvura Cemetery with witnesses who had participated in burying the bodies from Marange. They were shown the two mass graves in which the 83 bodies were allegedly buried.

A local miner who witnessed Operation Hakudzokwi told Human Rights Watch:

On November 3, 2008, we aborted a trip to the diamond fields after a villager warned us that soldiers were shooting and killing people there. As we tried to hike back to Mutare together with many other people, an army truck pulled up where we stood. Without warning, the five soldiers suddenly started to shoot at us. My nephew was shot in the neck and collapsed. We fled in different directions but returned after the army truck had gone. I went to check on my nephew who lay in a pool of blood. He was already dead. Six other people lay dead. Two of them were women. I went and reported the killing of my nephew at Nyanyadzi police station, but as yet no arrests have been made.[98]

Another villager told Human Rights Watch that he saw soldiers kill his brother in Muchena village on November 14, 2008. Soldiers accused the villager's brother of illegal diamond mining before force-marching the two of them to the hills where his brother was shot in the back of the head and died instantly.[99]

The killings appear to have been motivated by more than a desire to rid the fields of illegal miners and smugglers. The use of excessive force by the army seems to suggest that the military aimed to claim the diamonds for themselves and possibly others with connections to the military. The fact that diamond mining and smuggling remain under the control of the army supports the view that the army had no intention of ending illegal activities in Marange, but rather it aimed to control the gems and determine who got access to them.

Torture and Beatings

In addition to these killings, Human Rights Watch researchers found that soldiers tortured and beat scores of local miners and diamond dealers, some of whom died as a result of the injuries that they sustained. For instance, on January 8, 2009, a local Mutare businessman, 32-year-old Maxwell Mandebvu-Mabota, died from injuries from beatings by soldiers. A police officer in Mutare familiar with the case told Human Rights Watch:

On December 24, 2008, Brigadier Sigauke lured Mabota to Nyanyadzi. When Mabota arrived, Sigauke and 17 other soldiers accused him of smuggling diamonds and drove him to the diamond fields where they assaulted him using iron rods, booted feet, clenched fists, thick tree branches, and butts of their rifles demanding information on other buyers of diamonds.[100]

According to a human rights lawyer who interviewed Mabota before he died, the soldiers assaulted Mabota for several hours and stole all of his money and valuables-US$11,000, two mobile phones, and his car-before handing him over to the police, who in turn, took him to a hospital in Mutare. Mabota named Brigadier Sigauke as one of the soldiers who tortured him.[101] A medical doctor who examined Mabota in Mutare added:

As a result of severe and repeated blows using blunt objects, [the] patient [Mabota] suffered kidney failure and perforated lungs. After two weeks of no improvement his family transferred him to South Africa where he died upon arrival on January 8, 2009.[102]

Police made no arrests in connection with Mabota's death. As this report went to press, his relatives had not recovered any of the items allegedly stolen by the soldiers who tortured Mabota.[103]

Three middlemen who travelled to Marange on November 20, 2008, told Human Rights Watch how they had thought the military campaign was over and that it was safe to resume illicit diamond trading:

We drove to Chiadzwa and, as usual, paid the police to access the diamond fields where we parked, and waited to buy diamonds the following day. At about 9 p.m., two armed soldiers knocked on our car as we slept and ordered us out of the car. They took US$2,500 that we had and three mobile phones. They beat us on the soles of our feet and on our backs using iron bars for at least three hours. Around one in the morning they released us and we drove away. We dared not file a complaint with the police for fear of further victimization.[104]

On November 13, 2008, five armed soldiers beat a 66-year-old man and his family in Muedzengwa village, demanding to know the whereabouts of local miners. The man told Human Rights Watch:

The soldiers ordered us [seven men] to a borehole in Rombe village where they beat us using thick tree branches and took turns to immerse our heads in a water trough at the borehole saying, "If you want us to let you go, show us the local miners."[105]

The man's 16-year-old son added that when they told the soldiers that they did not know of any local miners, the soldiers became incensed and beat them more viciously for more than two hours before releasing them.[106]

On November 16, 2008, 14 soldiers rounded up at least 80 villagers at Muchena shopping center and demanded to know where illegal diamond miners were hiding before beating all the villagers using tree branches for more than three hours.[107] The same day, other groups of soldiers were beating villagers at Betera, Mukwada, Tonhorai, and Chakohwa, demanding to know the whereabouts of local miners and the identity of villagers who allegedly worked with the local miners. A headman from Mukwada ward told Human Rights Watch that on that day soldiers beat more than 300 villagers at various locations.[108]

Military abuses in Marange also included denial of medical care to victims of abuse in the community, including those who sustained dog-bite wounds and wounds from beatings or gunshots. Nurses based in the local community told Human Rights Watch that soldiers instructed them not to render medical care to any person who sustained injury by whatever means on the diamond fields.[109]

VII. Continuing Abuses by the Military in Marange

The scale of brutality and ruthlessness displayed by the military during Operation Hakudzokwi resulted in thousands of miners leaving Marange. By mid-November 2008, Marange diamond fields had come under tight control of the military. After the Chiadzwa killings, the army did not leave; instead, as of June 2009, the army continues to occupy the area. Different army units are rotated in turn into Marange, with about 600 soldiers based in the area at any given time. There is virtually no access to the Marange diamond fields for those without military or ZANU-PF connections at the very top level.[110]

Illegal diamond trading has not stopped; it continues to flourish, now with the military largely in control. Similarly, human rights violations are also continuing, as children and adults endure forced labor for military-controlled mining syndicates and soldiers continue to torture and beat villagers, accusing them of either being or supporting illegal miners who are not in military syndicates.

Mining Syndicates and Forced Labor

In late November and December 2008, the soldiers quickly revived the system of syndicates, setting up their own, often forcing villagers and miners to join them. A middleman acting for a principal based in South Africa told Human Rights Watch that he continues to buy Marange diamonds, but now he buys from soldiers.[111]

A local miner told Human Rights Watch how he and four others became part of a syndicate run by soldiers who violently defrauded the miners:

On December 10, 2008, we were arrested by two armed soldiers when we attempted to sneak into the diamond fields to dig. The soldiers said, "You need not run away from us; we need to discuss business with you. Tell us how and where to find diamonds and we can share equally with you whatever we find." That is how our syndicate with the two soldiers was formed and before long it had 23 local miners.

By December 24, we had found 709 grams of industrial diamonds and 17 gemstones, but the soldiers refused to give us anything. When we complained, the soldiers beat us all and ordered us to continue working.

When we attempted to run away, the soldiers shot at us and killed my friend who was running in front. I continued to run, not realizing immediately that l had been shot as well. I then noticed that my trousers were drenched in blood, and discovered I had been shot in the testicles, the left testicle hung out of the scrotum.

I slowly walked to Masasi clinic where staff there refused to attend to me. The nurse in charge said, "We are under strict instructions from the soldiers not to treat anyone shot or injured in the diamond fields." I eventually got transport to Mutare where l received treatment after three days. I do not know the names of the soldiers but I know for certain they are in No.1 Commando Regiment.[112]

Local people who spoke to Human Rights Watch said that in joint operations between the army and members of the Police Support Unit, people on several occasions were forcibly transported from Mutare, Birchenough Bridge, and surrounding small towns to fill up the pits and gullies created by diamond miners. According to witnesses, on November 24, 2008, soldiers rounded up 76 people in Mutare, put them on a bus, and took them to Chiadzwa, where they were detained, beaten, and forced to dig for diamonds for the soldiers.[113] Muchena and Betera villagers told Human Rights Watch how on November 30, soldiers ordered everyone in their village to dig diamonds for them under armed guard for several days.[114]

Witnesses said that soldiers routinely force members of the local community, including children and women, to work on the diamond fields for them.[115] If anyone resists, they risk torture, beatings, or even death. Villagers told Human Rights Watch how soldiers also beat them for failing to find diamonds, accusing the villagers of pretending not to find the precious stones, saying, "How come you used to find stones when you were digging for personal benefit?"[116]

Forced Child Labor

In violation of international law, children in Marange are being forced to work without pay under the most arduous of conditions. A local lawyer told Human Rights Watch that his organization had received credible information leading him to conclude that as of February 2009 at least 300 children continued to work for soldiers in the diamond fields.[117]

According to 10 children (seven boys and three girls of ages ranging from 12 to 17 years) whom Human Rights Watch interviewed, soldiers forced the children at different times from December 2008 to February 2009 to work in the diamond fields. The children carried diamond ore from the field and assisted women to sieve and select the precious stones. They worked up to 11 hours each day with no pay or reward for their labor.[118]

Two women, who were among a group of villagers forced to dig for diamonds for three weeks in December 2008, told Human Rights Watch:

The soldiers were armed and guarded us every day while we worked in the fields. Each day we worked for 11 hours, from 7 a.m. to 6 p.m., without a break. Men did the digging, while women and children carried the ore from the field to a source of water-either a borehole well or a stream. Women and children were also responsible for sieving the ore and selecting the precious stones. But all the time, the armed soldiers would be standing close by, on guard and ready to take the diamonds we selected.

We worked together with about 30 children of ages between 10 and 17 years. The children worked the same 11 hours each day as adults did. The soldiers had a duty roster for all villagers in Chiadzwa to take turns to work in the fields, irrespective of age.[119]

A 13-year-old girl told Human Rights Watch:

For two weeks in January 2009, I worked in the diamond fields together with several other children to carry sacks of diamond ore from the field and to fetch water to sieve the ore. I was too afraid to run away. Every day, I would carry ore and only rest for short periods when the men were digging. We always started work very early in the morning before eight and finished when it was dark after six. All I want now is to go back to school.[120]

A 15-year-old boy added:

Sometimes, when we get hungry and tired, we walk slowly because the bags of ore are heavy to carry. But the soldiers tell us to be fast. Sometimes, soldiers would beat us for working slowly so we always tried to be fast.[121]

A 15-year-old girl told Human Rights Watch that the work in the diamond fields was hard, and soldiers provided no food or water to everyone working on the fields. On one occasion, she said, five young girls collapsed after working for more than five hours in the sun while the soldiers refused to give them a break.[122] Another 15-year-old boy said he quit school in 2006 and worked in the fields as part of a police syndicate before soldiers forced him to join their syndicate in December 2008.[123]

A teacher at a local school in Marange told Human Rights Watch:

Soldiers force everyone to work for them in the diamond fields, including teachers and pupils. I was forced to work in the diamond fields together with other teachers and pupils from my school for a week in February 2009. The soldiers compiled a duty roster of all teachers and some pupils and they force us to take turns to work in the fields in accordance with their roster.

However, even before soldiers began to force everyone to work for them, schools had long stopped functioning due to the economic crisis, and hundreds of children were panning for diamonds alongside adults. The difference is that this time the children and adults are forced to work without pay and we all surrender any stones we find to the soldiers.[124]

A 17-year-old boy told Human Rights Watch how on December 1, 2008, he and two friends (ages 16 and 17) were part of a group of people randomly picked up from Mutare and taken to the diamond fields by bus:

Five armed and uniformed soldiers told me and my friends and six other boys in the group that we were still young so they would teach us community service and lessons in patriotism. On the bus to the fields the soldiers ordered everyone on the bus to surrender all personal valuables.

At the diamond fields the soldiers forced us into a cage and beat us throughout the night demanding to know the names of diamond dealers. The next day, we were forced to fill the holes and gullies made by local miners using bare hands. We were given no food or water. That evening we were bused back to Mutare.[125]

These working conditions for children are forbidden by international law.The International Labour Organisation's Convention on the Worst Forms of Child Labour, ratified by Zimbabwe on December 11, 2000, forbids forced or compulsory labor for children, defined as any person under the age of 18.[126] Article 3(d) of the convention states that "the worst forms of child labour" comprise"work which, by its nature or the circumstances in which it is carried out, is likely to harm the health, safety or morals of children."[127] By this definition, scores of children in Marange have been engaged in the worst forms of child labor, in violation of Zimbabwe's obligations under the convention.

Theft and Harassment of the Local Community

Villagers interviewed by Human Rights Watch said the soldiers continue to subject them to unlawful and arbitrary searches and loot property such as cash, food, blankets, mobile phones, cars, and furniture. The soldiers also search houses without the necessary search warrants, in violation of Zimbabwean laws protecting privacy and prohibiting arbitrary searches. Soldiers beat villagers and demand to know the source of money they use to buy various items, and then confiscate those items. Villagers claim that the army forces local women and children to cook for them and slaughter livestock, another form of forced labor.[128]

A local leader in Marange told Human Rights Watch:

The soldiers came with nothing. They are taking blankets from the community. I have received several reports of soldiers stealing goats and chickens for their meals, and they are forcing villagers to fetch water, firewood for them, as well as to cook and clean for them. The soldiers have become a burden on Marange community.[129]

A lawyer familiar with the soldiers' activities told Human Rights Watch:

Members of the army and police are violating people's rights to due process of law. They are moving about in Mutare and Birchenough Bridge arbitrarily taking away people's property. If there is reasonable suspicion of any crime, the police must properly investigate and take individuals to court, not the military.[130]

Trust Maanda, provincial coordinator for the organization Zimbabwe Lawyers for Human Rights Manicaland, told Human Rights Watch that as of February 7, 2009, only one of the hundreds of victims of army and police brutality had asked him to file suit against those who tortured him. Maanda explained that this low figure was mainly a result of fear.[131]

Human Rights Watch researchers passed 11 police checkpoints along the road to Marange during a visit in February 2009. In addition, they observed armed uniformed soldiers guarding the diamond fields and military checkpoints at five-kilometer intervals within the diamond mining area. Such a presence indicates that illegal diamond panning and dealing remain rampant, albeit now under the control of the military.

The army also maintains a ban, ostensibly to prevent smuggling of diamonds, on public transport reaching or passing through Chiadzwa. Buses stop at Mutsago and Bambazonke shopping centers, forcing members of the local community to walk more than 20 kilometers to reach their homes. This ban is not based on any law. It is an unnecessary infringement on freedom of movement, constituting harassment.

Torture and Beatings

Several witnesses and victims told Human Rights Watch that soldiers continue to assault, harass, and subject the local community to torture, demanding that they reveal the names of local miners and diamond smugglers.