“They Hunt Us Down for Fun”

Discrimination and Police Violence Against Transgender Women in Kuwait

Glossary of Terms

Gender Expression: external characteristics and behaviors that societies define as “masculine” or “feminine,” including features such as dress, appearance, mannerisms, speech patterns, and social behavior and interactions.

Gender Identity: a person's internal, deeply felt sense of being male or female, or something other than or in-between male and female.

Gender Identity Disorder (GID): the formal diagnosis that psychologists and physicians use to describe persons who experience significant gender dysphoria (discontent with their biological sex and/or the gender they were assigned at birth). The International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10 CM) and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV TR) classify GID as a medical disorder. The new version of the DSM due in May 2013 will likely replace this category with "Gender Dysphoria." Some authorities do not classify GID or gender dysphoria as a mental illness, describing it instead as a condition for which medical treatment is sometimes appropriate. In Kuwait, GID is a disorder recognized by the Ministry of Health, and the state hospital has issued formal diagnoses to individuals.

Sexual Orientation: often conflated with gender identity, the term refers to a person’s sexual and emotional attraction to members of the same gender (homosexuals, gay men, and lesbians), the opposite gender (heterosexuals), or both genders (bisexuals).

Transgender: someone whose gender identity or gender expression differs from the physical characteristics (or “sex”) with which they may have been born. Understanding their experiences entails recognizing that gender is not the same as biological sex. Biological sex is the classification of bodies as male or female on the basis of biological factors, including hormones, chromosomes, and sex organs. Gender describes the social and cultural meanings attached to ideas of “masculinity” and “femininity.” In this report “transgender” is used as an umbrella term to include transsexual and transgender people.

Transsexual: a transgender person who has undergone, or is undergoing, hormone therapies and/or the complex of cosmetic and reconstructive procedures usually known as sex reassignment surgery (SRS) so their physical sex corresponds to their subjectively experienced gender identity. Not all transgender individuals seek to undergo SRS, but for those who wish to, a formal GID diagnosis is usually necessary.

Transgender women: persons designated male at birth but who identify and may present themselves as women. Transgender women are referred to with female pronouns.

Transgender men: persons designated female at birth but who identify and may present themselves as men. Transgender men are referred to with male pronouns.

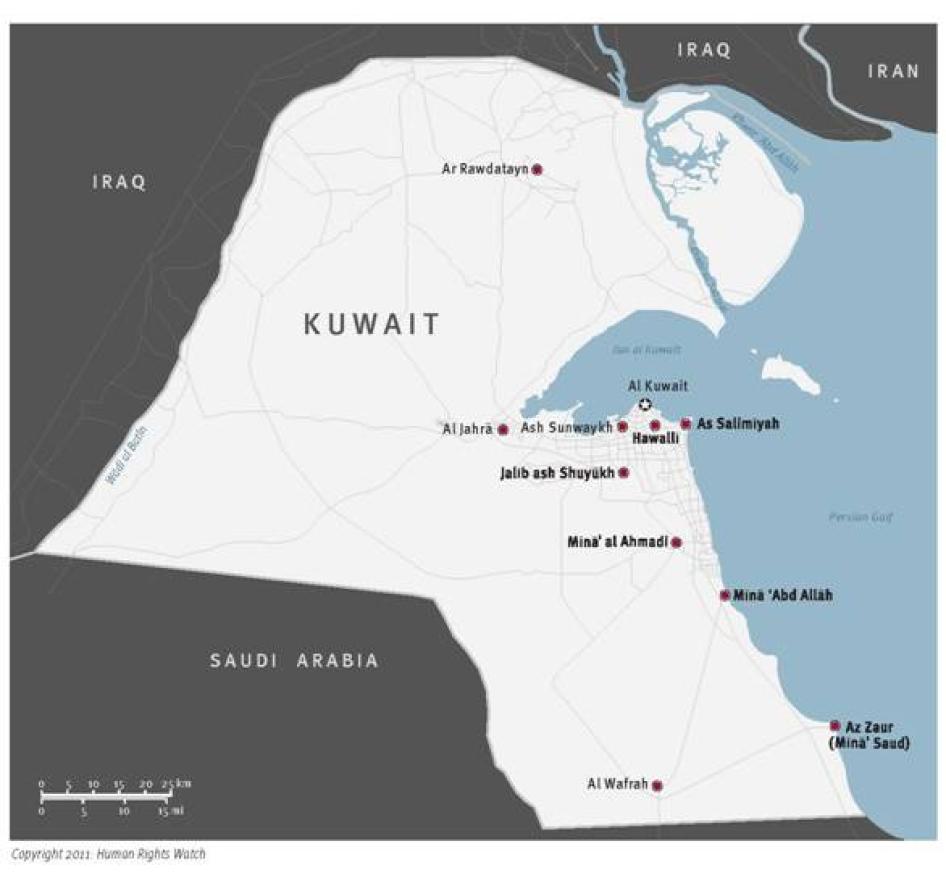

Map of Kuwait

Summary

They hunt us down for fun. They don’t want me to dress like a woman so I don’t. I wear a dishdasha (traditional Kuwaiti male garment) now. I cut my hair short. After all that I was still arrested, beaten, and raped for having a smooth, feminine face. What can I do about my face?

–Amani, 24, Kuwait City, February 8, 2011

The role and behavior of women in public has long been a fraught issue in Kuwait, where conservatives have anxiously sought to maintain traditional gender roles and there is growing social anxiety regarding “proper” gender comportment.

Transgender women—persons designated male at birth but who identify and present themselves as women—have never fitted easily into this framework. Nonetheless, many transgender women, who constitute a visible and tightly networked community in this country of approximately 2.5 million people (including non-nationals), told Human Rights Watch they had for many years generally been able to circulate freely, secure employment, access public health care, and live with minimal interference from police. While harassment from the general public was not uncommon, they could access channels of redress, including from police, although the seriousness with which their complaints were handled depended on the individual officer.

That began to change in May 2007, when Kuwait’s National Assembly voted to amend article 198 of the country’s penal code. A previously generic public decency law now stipulated that anyone “imitating the opposite sex in any way” would face one year in prison, a 1,000 Kuwaiti dinar fine (approximately US$3,600), or both.[1] The amendment did not criminalize any specific behavior or act, but rather physical appearance, the acceptable parameters of which were to be arbitrarily defined by individual police.

These provisions have created a sea-change in the lives of Kuwaiti transgender women. Many have become the most recent victims of abuse by police, who often take advantage of the amendment to article 198 to harass, sexually assault, and arbitrarily arrest them.

This report documents the physical, sexual, and emotional abuse and persecution that transgender women face at the hands of police, and it documents the discrimination that transsexual women face on a daily basis—including in public more generally—due to the law, which in itself constitutes a human rights violation.[2] This fuels a climate of inconsistency towards transgender people, which is accentuated by divided Islamic opinion on the matter of sex reassignment and gender correction. The report also looks at obstacles that transgender women face accessing health and employment, and the lack of protection and redress available to transgender people who experience abuse.

For example, transgender women—who were previously often seen in malls, coffee shops, and other public spaces, particularly the city’s social center Salmiya—have since 2008 been the main focus of police arrests for allegedly violating the amendment to article 198. Although many began dressing in male garb and presenting themselves as men to avoid persecution, police have been undeterred, basing arrests on “a soft voice,” “smooth skin,” or some other physical trait beyond the women’s control. Thirty-nine of the 40 transgender women whom Human Rights Watch interviewed said they were arrested, some as many as nine times. In most cases (54 out of 62) the court either acquitted or failed to reach a verdict, although transgender women claim that police forced them, threatening or engaging in physical violence, to sign a declaration stating they would “never again imitate the opposite sex” before releasing them. Only 2 of the 62 cases resulted in convictions (between six months to a year’s imprisonment).

All the women interviewed described some form of police abuse, at times rising to the level of torture, degrading and humiliating treatment, and sexual assault or harassment—although police deny mistreatment.[3]

Kuwaiti media have reported on the arrest of a small number of transgender men, although Human Rights Watch found these arrests happen significantly less frequently than those of transgender women. One possible reason is that women generally enjoy more flexibility in their dress and presentation, and it is more difficult to define what constitutes gender transgressive dress for women than for men. According to several lawyers and transgender women and men interviewed, transgender men and boyat— a term common in the Gulf to describe masculine women—generally escape police scrutiny because police fear accusations of sexually harassing women, charges that are taken very seriously in Kuwait.

Among the abuses transgender women report suffering at the hands of police are beatings and physical abuse with fists and cables, verbal taunts, and humiliation that includes forcing them to clean toilets and being paraded naked inside the police station. Sexual harassment is also a common complaint. In some cases transgender women reported that police had blackmailed them for sex, threatening them with arrest if they did not comply, an act that constitutes sexual assault. Several transgender women have told Human Rights Watch that police use the law and vulnerability of transgender individuals as a way to have easy, consequence-free sex.

Transgender women interviewed said they rarely report the police mistreatment, abuse, and sexual assault they encounter for fear of re-arrest, retaliation, and direct threats by the perpetrators, whether civilian or police. These fears are not unfounded; many transsexuals told Human Rights Watch they were arrested simply for going to the police station to report an unrelated crime. According to Ghadeer, a 22-year old transgender woman:

Before the law we had no problems, we would come and go as we pleased and be out in public safely…. When we were stopped at checkpoints and the police would ask us for our IDs and see that we were male they would just smile or even find us cute and let us pass. In the worst of cases they would try to take our numbers to arrange for a date. So there was harassment, but rarely was it as violent as it is now. After the law came out, I started hearing that X was in prison, Y was in prison. I lived in fear and terror. I felt like I couldn’t move, but it is my right to go out, to go to the souk, to go to the doctor.[4]

In early 2011 the minister of interior resigned in response to several scandals involving police torture. The most notorious case involved the death of Mohammad al-Muteiry, who was detained on suspicion of possessing alcohol and tortured for six days at the Ahmadi Criminal Investigation Department.

In addition, transgender women reported a host of due process and procedural violations connected to their arrest and detention. Many said that police arrested them even though they had done nothing to “imitate” the opposite sex and forced them to dress in women’s clothes at the police station to justify the charge against them; others said that they faced arrest even when reporting other crimes. Police often detained them well beyond the four day pre-charge detention period permitted by Kuwaiti law, they said, and typically failed to inform their families of their whereabouts or did not allow them to meet with their lawyers.

Article 198 has not just led to arrests and police abuse, it has permeated every aspect of transgender lives. It does not criminalize any specific behavior or act, but mere physical appearance, the acceptable parameters of which are arbitrarily defined by individual police.

Transgender women have reported that ordinary citizens in public spaces report them to police, encouraged by an unrelenting vilification campaign in Kuwaiti media that portrays them as a destructive force and a threat to the fabric of Kuwaiti society. They also said that hospital doctors have reported them to police after noting the gender on their government-issued IDs, which they are required to present, does not match their appearance and presentation—effectively limiting their access to health care. Even driving around the city can be perilous, with transgender women reporting that they risk police picking them up at numerous checkpoints on main highways and side streets. Indeed, the situation has become so dire that many transgender women said they live under what amounts to self-imposed house arrest to avoid the dangers that police and the broader public pose.

Adding to the difficult circumstances that Kuwaiti transgender people face is the lack of any law governing sexual reassignment surgery (SRS), a procedure that some transgender people turn to in order to align their physical characteristics with their gender identity. While there has only been one court decision in Kuwait to date granting a transsexual woman permission to change her gender in her legal identity papers from male to female, which was quickly overturned by a court of appeals, there is also no explicit legislation banning the procedure. In the absence of any law governing sex-change cases, judges base their decisions on personal conviction. However, conservative MPs are pushing a bill regulating plastic surgery that includes articles explicitly banning both SRS and gender correction, a dire prospect for many transgender individuals who medically require the procedure as treatment for Gender Identity Disorder.

Unlike most people, whose internal, deeply felt sense of belonging to a particular gender corresponds to the sex they were assigned at birth based on their external sex organs, transgender people have a gender identity that differs from their birth sex—known as Gender Identity Disorder, or GID. While the Kuwaiti medical establishment formally recognizes GID as a medical condition, the law continues to criminalize transgender women who suffer from the disorder, including those who have obtained documentation from the Ministry of Health certifying their disorder.

The police abuse and torture that is at the center of this report is itself a grave violation of human rights, irrespective of the law allegedly broken. The amendment to article 198 and its consequences violate fundamental principles of human rights enshrined in international conventions to which Kuwait is a signatory. By criminalizing an individual’s gender expression and identity, the law violates the right to non-discrimination, equality before the law, free expression, personal autonomy, physical integrity, and privacy. The consequences of the amendment further violate the right to health and accessible health care without discrimination. The law adds to the vulnerability of an already marginalized population, making redress for egregious police abuses against them, including sexual assault and torture, difficult due to fear of reprisal.

Kuwait should take immediate steps to investigate allegations of torture, prosecute those responsible, and implement working mechanisms to curb future abuses. In order to comply with its obligations under international law, Kuwait should impose an immediate moratorium on arrests under amended article 198 and repeal the amendment, which in and of itself is vague and overbroad, failing to define the elements of the crime with any specificity, and as a result has been applied in an arbitrary manner. Furthermore, the law constitutes discrimination against transgender individuals. The state should allow those diagnosed with GID to change their gender in their legal identification papers.

The lives of transgender women have been made miserable as a result of the law and the police abuse that has accompanied it—an untenable situation that can, and must, be remedied by repealing the legislation.

Key Recommendations

To the Police

- Investigate all allegations of torture, sexual assault, and ill-treatment of detainees and prosecute those responsible in accordance with the law.

- Put in place workable mechanisms to ensure the protection of detainees and other individuals who wish to file a complaint against the police for abuse or mistreatment.

- Investigate all arrests under the amendment to article 198 for procedural violations, including arrests in the absence of evidence, arrests without warrants, and forced confessions; and prosecute those responsible in accordance with the law.

To the Ministry of Justice

- Investigate all convictions under article 198 for procedural violations, including convictions in the absence of evidence, arrests without warrants, and forced confessions; and overturn all convictions that do not fulfill procedural requirements.

To the Ministry of Interior

- Issue a directive at all levels of the police force to refrain from active investigation or pursuit of charges against transsexuals for “imitating the opposite sex.”

To the Ministry of Health

- Seek assurances from the Ministry of Interior that would ensure that, until its repeal, amended article 198 is not applied to anyone who has been diagnosed with gender identity disorder.

- Issue official cards for transgender individuals identifying them as such that prevent arrest by the police.

- Adopt internationally recognized standards of health care for transgenders such as the World Professional Association for Transgender Health’s Standards of Care for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender Nonconforming People.

- Ensure that training in accordance with recognized international standards of health care and human rights is available to health service professionals, including psychologists, psychiatrists and general practitioners, as well as social workers, with regard to the specific needs and rights of transgender persons and the requirement to respect their dignity.

- Ensure that transgender people have access to the medical and psychological assistance and support they require, and that such support and assistance is available to transgender individuals within a reasonable time.

To the National Assembly

- Instate an immediate moratorium on arrests of individuals under the amendment to article 198 of the Penal Code, which criminalizes “imitating the opposite sex.”

- End discrimination against transgender individuals by repealing the amendment to article 198.

- Allow individuals diagnosed with Gender Identity Disorder (GID) to undergo sex reassignment surgery.

- Allow individuals diagnosed with GID to change their gender in all legal documents.

Methodology

This report is based on a two-week field visit to Kuwait City in February 2011 and a follow up visit in December 2011. Two Human Rights Watch researchers conducted in-depth interviews with 40 male-to-female transgender persons, all but one of whom had been arrested at least once for “imitating a member of the opposite sex,” as well as lawyers, doctors, health care workers, civil society activists, academics, a representative of the Kuwaiti police force, and elected members of Kuwait’s National Assembly.

On December 5, 2011, Human Rights Watch sent a letter to the Ministry of Interior outlining the concerns described in this report, but we received no response. The letter can be found in the annex of the report.

Research also included reviewing local newspapers, TV shows, and nongovernmental organization (NGO) reports.

This report focuses on transgender women, since the vast majority of arrests for “imitating the opposite sex” have targeted that population. However, Human Rights Watch also spoke with several gay men, lesbians, boyat (a term common in the Gulf to describe masculine women, and female-to-male transgender persons, who face similar and equally serious problems.

The interviewees were identified primarily through word-of-mouth networking with members of the transgender community in Kuwait. Interviews were conducted individually and in Arabic.

This report employs pseudonyms in order to keep confidential the identities of transgender interviewees, and in some cases withholds other identifying information to protect their privacy and safety.

While the research presented in this report is not comprehensive or exhaustive, the similarity of the stories and the frequency with which certain experiences, such as sexual assault, were repeated indicate that the violations described in this report extend beyond isolated incidents and constitute a broader pattern of abuse.

I. Background

Kuwait is a constitutional monarchy with a parliamentary system of government—the 50-seat parliament is known as the National Assembly. Although political parties are formally banned, several political groups act as de facto parties to which members of parliament (MPs) are affiliated, such as Bedouins, merchants, and Sunni and Shi'ite groups, as well as Islamists and secular leftists and nationalists.[5]

The National Assembly may set up standing and ad-hoc committees whose members are selected from within the assembly. In 2006 Islamist MP Waleed Al-Tabtabai formed an ad-hoc parliamentary committee for the “Study of Negative Phenomena Alien to Kuwaiti Society.” Although the committee was originally established only to study what its members deem to be “negative social phenomena,” it also proposes bills to the National Assembly. One such bill was the amendment to article 198.

The committee raised much controversy, particularly during the 2008 term when the Islamists comprised a majority of the parliament. While its proponents claim that the committee’s mandate is to uphold traditional Kuwaiti values, others see it as a precursor to a Saudi-style Committee to Promote Virtue and Prevent Vice, an authorized law enforcement agency tasked with upholding public morality. Critics accuse the Kuwaiti committee of attempting to impinge on constitutionally guaranteed freedoms, citing its record of trying to impose strict controls on private parties and gatherings, challenging the legal definition of “privacy” in order to further regulate people’s personal lives and conduct, opposing TV shows and concerts that they consider immoral.

These opposing views highlight the increasing rift between Islamists and liberals in Kuwait’s National Assembly. However, while some laws that the committee proposed faced considerable opposition (such as banning “revealing” swimwear for women), the amendment that Tabtabai tabled criminalizing “imitating the opposite sex” was passed unanimously by the 40 MPs present. The issue was seen as insignificant in the larger political battle.

The National Assembly, and its passing of the amendment to article 198, cannot be seen in isolation from these wider social and political trends. As visible symbols of gender transgression who challenge gender norms by presenting as what appears to be the “opposite sex”, transgender persons serve as easy targets against whom the state can flex its moral muscle.

While it is primarily transgender women who face criminal punishment, the social control of transgender women and boyat takes the form of a whole gamut of religious arguments that cast them as sinners who “reject God’s creation,” in addition to “medical” and “biological” arguments that regard them as victims who need to be healed or treated.[6] The two discourses sometimes overlap, and religious dogma and traditional mores rather than science and modern medicine inform much medical practice on the issue.

In religious arguments against gender transgressive behavior and presentation the notion of al-fitra(natural constitution) figures quite prominently, resting on the assumption that men imitating women (or vice-versa) violates the natural constitution of human beings. Effeminate men, boyat, and transgender people are thought to contribute to the spread of corruption and the disintegration of society by upsetting this balance.[7]

Many health care professionals and Kuwaiti religious leaders suggest that “treatment” and “correction” options for transsexual individuals should aim to restore them to their “natural state.”[8] One psychologist suggested injecting testosterone into male to female transsexuals, forcing them to live as men for a period of time: if that doesn’t work, she said, they might be allowed to transition into women.[9]

However, several prominent doctors have advocated for the rights of transgender people, including Dr. Hasan Al-Mousawi, a professor of psychiatry at Kuwait University and Dr. Haya Al-Mutairi, head of the psychiatry department at the Psychological Medicine Hospital, both of whom oppose criminalization.[10]

* * *

The following sections examine the broader socio-political environment and climate of gender regulation in which the amendment to article 198 was passed. The law is analyzed through a human rights perspective, followed by a discussion on debates within Islamic jurisprudence on the issue of SRS and legal gender change in identity.

Policing Gender

Gender and sexuality often become foci for broader anxieties in times of rapid social and political change.[11] The criminalization of “imitating the opposite sex” in Kuwait is one element of a broader regime of gender regulation that began to take hold after 1992, when tensions between “liberal” and “traditionalist” Kuwaitis after the Gulf War intensified as each tried to establish their status as influential political entities.[12]

The battle over women’s rights and role in society constituted one of this conflict’s most prominent arenas, and presented an opportunity for traditionalists and Islamists to join forces.[13] According to Kuwait scholar Mary Ann Tétreault:

While tribalists were anxious to keep their daughters obedient and marriageable, Islamists hoped to diminish female competition for jobs available to new graduates during a slow economy. Their shared vision of the globalization threats presented by women whose credentials and skills, including foreign language proficiency, generally exceeded those of men, contributed to ad hoc violence in policing the behavior of women unwilling to submit to conservatives’ demands and expectations.[14]

The events outlined below trace some of the major legislative milestones in the social and political regulation of gender in Kuwait:

|

1992-1996: |

Towards the end of the term of the first legislature elected after the Kuwait’s liberation from Iraq, the battle over women’s roles left their rights so undermined that Islamists in the National Assembly were able to pass a law requiring gender segregation in universities. It remains in effect to this day, despite opposition from liberals. |

|

2005: |

Tensions flared after the National Assembly’s landmark decision to grant women the right to vote and run for office in local and parliamentary elections, a time of dwindling of Islamist influence in the National Assembly. Conservatives opposed the decision, and inserted a last-minute rider that "women as voters and MPs" must follow Sharia without specifying precisely where or how. Islamist and tribal MPs had previously successfully fought off women’s suffrage proposals. Responding to the new law, Islamists tried to enact further legislation to restrict women’s roles in the political sphere and tighten control over “subversive” or “immoral” gendered behavior. Women’s political participation grew steadily. Then-Prime Minister Sheikh Sabah al-Ahmad Al Sabah appointed the first female cabinet minister, Massouma Mubarak, as minister of planning and administrative development. |

|

2007: |

Kuwait’s second female cabinet member, Nouria al-Sbeih, caused an uproar when she took the oath of office after refusing to wear the hijab (headscarf or veil) worn by many Kuwaiti women. Although it is not mandatory, conservative MPs attempted to use this refusal to discredit female politicians. |

|

2008: |

Twenty-seven of the 275 candidates in the parliamentary elections were women. None win. |

|

2009: |

Kuwait held parliamentary elections for the third time in three years. Of 16 female candidates who ran, four won, becoming Kuwait's first female lawmakers. Two female MPs, Dr Rola Dashti and Aseel Al-Awadhi, appeared in the assembly without wearing the hijab. Three Islamist MPs immediately protested, citing the Sharia rider that was passed with the electoral law. As a result, Dashti tabled an amendment demanding the rider be dropped. The Constitutional Court ruled that the rider in the election law is not specific and so can be interpreted in different ways. The court dismissed a case brought by a Kuwaiti man to have Dashti and Al-Awadi dismissed from the assembly for violating the election law.[15] |

|

2010: |

Islamist parliamentarians who cater to a mainly conservative, tribal constituency with proposals for “morality” legislation, introduced two laws. The first, commonly known as the “bikini law,” sought to criminalize revealing swimwear for women. The second aimed to regulate plastic surgery, with specific articles banning sex reassignment surgery, and formally introduced a ban on gender correction in legal papers. |

|

2011: |

In January, a parliamentary committee rejected the “bikini law,” arguing it is unconstitutional.[16] The plastic surgery bill has not yet passed at this writing. |

Media have taken an active role in policing gender. Since 2007 several national talk shows and TV programs have discussed the issue of the “third sex” and the “fourth sex” (references to gender non-conforming men and women respectively) as a social vice that needs to be eliminated.[17] Some journalists, lawyers, parliamentarians, and doctors have opposed this demonization.

An early critic of the amendment to article 198 was Hussein al-Abdallah, a columnist for the Kuwait daily Al-Jareeda, who wrote that the elasticity in the wording of the bill would “violate personal freedoms under the pretext of upholding the law.”[18] MP Adnan Abdulsamad, a member of the National Assembly’s Human Rights Committee, told Human Rights Watch that imprisoning transsexuals was unjust, and they should receive appropriate treatment rather than be sent to prison.[19] Dr. Aseel Al-Awadi, one of the four female parliamentarians and a staunch advocate of women’s rights, also spoke out against imprisonment of transgenders under amended article 198, calling it “a superficial handling of the issue,” and advocated treatment instead.[20] She told Al-Rai newspaper:

In terms of [transsexuals’] rights as citizens, we need to separate between our opinions of their behavior and our professional duties. A doctor should not deny treatment to a person because he or she appears to be “imitating.” Likewise, a police officer must listen to citizens’ complaints even if he disagrees with their dress or behavior.[21]

Given this long-running controversy within government and society over the appropriate roles of men and women, it is not surprising that parliament would turn its attention towards those who visibly challenge these gender roles, such as transgender women, by passing a law criminalizing gender non-conforming appearance, the victims of which have almost invariably been transgender women.

Problems with the Law

The amendment to article 198 is problematic for several reasons. First, it is arbitrary in its application, because it fails to define concrete, specific criteria for what constitutes the offense of “imitating” the opposite sex, effectively allowing police absolute discretion in determining the criteria for arrest. Second, it fails to protect even those who have undergone full SRS, because there is no provision for allowing those who have undergone SRS to change their legal identity. Third, it effectively criminalizes transgender people even though the Kuwaiti Ministry of Health recognizes Gender Identity Disorder as a legitimate medical condition. Fourth, it constitutes clear discrimination against transgenders as the law directly targets individuals whose gender identity and presentation does not correspond with the gender assigned to them at birth.

The amendment to article 198 does not state what constitutes “imitating a member of the opposite sex,” giving the police and the courts complete discretion in determining whether someone’s appearance or actions constitutes “imitation of the opposite sex.” Human Rights Watch spoke with transgender women and biological males who identify as men who say police have arrested them for such arbitrary things as “having a smooth face,” wearing “a feminine watch,” and having “a soft voice.” Many transgender women reported they had started dressing as men to avoid arrest, but even with dishdashas, baggy sweatshirts, long hair tucked under caps, or jeans and sneakers, they were still unable to avoid arrest. Police suspicious of “feminine-looking” males would sometimes go so far as to check whether an individual was wearing female underwear and arrest them on that basis. For Kuwaiti police, it seems there is no way for transgender women not to break the law.

The amendment’s author, MP Waleed Tabtabai, claimed that it was designed to target “members of the third sex.”[22] However, Human Rights Watch has documented cases where police have also arrested male-identified biological men under the article. Ahmad, a 19-year-old man, told Human Rights Watch:

I don’t know why I was even arrested; I am a man, I even had a full beard at the time! In June 2010, I was ordering some food from a drive-through and a police patrol stopped me. They beat me in the street in broad daylight and then took me to the station where they cursed me and beat me. I was finally released three days later after I was forced to sign a confession and promise that I wouldn’t imitate women again. How many women do you know have beards?[23]

Sout al Kuwait, a Kuwaiti human rights group that has criticized the law, asked:

Is a man’s long hair an imitation of women? What about dyeing the hair or the beard with henna? Wearing kohl(a black eye cosmetic)? A lot of these practices are part of Arab heritage and some of them were even practiced by the prophet.[24]

On July 14, 2010, Al-Jareeda daily newpaper reported that the public prosecutor, Hamed al-Othman, urged members of the National Assembly’s legislative committee to clearly define the parameters of what constitutes “imitating the opposite sex.” The newspaper reported that committee members promised to take al-Othman’s recommendations into consideration, either by altering the text of the amendment or in an explanatory memorandum.[25] Neither has happened, and as al-Othman predicted, the misapplication of the law has led to many human rights violations.

Furthermore, the law allows the prosecution of individuals who have undergone SRS because there are currently no legal provisions in Kuwait that allow individuals to change their legal identities. Many transsexuals in Kuwait have had partial SRS in other countries such as Thailand, Syria, and Lebanon, while others have undergone complete sex reassignment surgery. Between article 198 and the refusal of Kuwaiti courts to recognize SRS, these individuals are left in a state of legal limbo. There is virtually nothing they can do to avoid arrest, because although they are now physically female, their identity cards continue to identify them as male. Rola, a 32-year old transsexual woman who had undergone complete sex reassignment surgery in 2004, was arrested five times since the law was passed. The first time she was arrested, on July 23, 2008, she spent two months in pre-trial detention before being declared innocent by a Kuwaiti court. Despite this ruling, police arrested her another four times and released her after humiliating her at police stations.[26]

MP Tabtabai, author of the amendment to the law, recognizes the contradictions of this law:

The decision to legally change one’s gender in one’s identity papers in cases of complete transition should be based on a complete examination and report by a doctor.… In those cases, they should be referred to mental health professionals rather than be imprisoned.[27]

In one case that Human Rights Watch documented, police arrested a transgender woman who had undergone complete sex reassignment surgery but had not been able to change her legal documents for “imitating the opposite sex.” Although she was never brought to court, the police shaved her head and forced her to sign a declaration stating that she would never imitate the opposite sex again.[28]

In April 2004 a landmark ruling by a lower court in Kuwait allowed Amal, a Kuwaiti transsexual woman who had undergone complete sex reassignment surgery in Thailand, to change her legal documents from male to female. The verdict was based on a number of medical reports and a forensic examination carried out on the complainant as well as religious edicts of Al-Azhar in Cairo allowing for sex reassignment surgery in specific cases.[29] In October 2004 the government filed an appeal, supported by a group of Islamist lawyers and Amal's father, who told the court the verdict brought “shame to his family,” and the initial decision was overruled and Amal continues to be identified as male in her legal documents.[30]As there is no law in Kuwait governing sex-change cases, judges base their verdicts on personal conviction.

GID is the formal diagnosis that psychologists and physicians use to describe persons who experience significant gender dysphoria (discontent with their biological sex and/or the gender they were assigned at birth). The International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10 CM) and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV TR) classify GID as a medical disorder. Some authorities do not classify GID or gender dysphoria as a mental illness, describing it instead as a condition for which medical treatment is sometimes appropriate.

The Ministry of Health officially has recognized gender identity disorder in individuals who have received such a diagnosis by the state-run Psychological Medicine Hospital as a legitimate medical condition and issues formal letters to that effect, which many transgender women carry with them at all times. Yet the law does not exempt from arrest transgender people who have received such a diagnosis.

Regardless of medical status, prosecuting individuals because of their gender identity and/or presentation constitutes discrimination against a protected social group. In Kuwait, transgenders are arrested for who they are, not for what they do. The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), to which Kuwait is a signatory, obliges each State party “to guarantee that the rights enunciated in the Covenant will be exercised without discrimination of any kind as to race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status”. The Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights has expressly designated gender identity as prohibited grounds for discrimination.

However, even receiving this diagnosis does not guarantee treatment, for which there is no established or recommended path. MP Muhammad Hayef, a member of the assembly’s Committee for the Study of Negative Phenomena, said in a TV interview in 2008 that members of the “third sex”—as transgender people are widely called in popular culture—should not be imprisoned, and called for establishing treatment centers instead. According to Hayef, “Prison increases the spread of this phenomenon but doesn’t treat it.”[31] Despite this perspective, neither Hayef nor any other MP has tried to end the arrests, repeal the amendment, or offer any concrete alternative, such as allowing those diagnosed with GID to undergo sex reassignment surgery and gender correction.

Sara, a transgender woman, decried the hypocrisy of such statements:

One minute they say we shouldn’t be imprisoned, the next minute they’re on TV saying that the police need to clean the streets from such filth…. Who is going to hold them accountable for their words?[32]

Kuwaiti human rights organization Sout Al-Kuwait has argued that the amendment to article 198 contravenes article 10 of the Kuwaiti constitution, which stipulates that the “state cares for the young and protects them from exploitation and from moral, physical and spiritual neglect.”[33]It argued that punishing an individual for a medical condition violates her basic rights and that the state failed to recognize that many of those accused of “imitating a member of the opposite sex” suffer from gender identity disorder, treatment of which “can only happen through sex reassignment surgery.”[34]

Although the state-run psychiatric hospital has issued GID diagnoses, the Kuwaiti police, courts, and other government branches do not recognize it to be a legitimate reason not to arrest and convict people. According to lawyer Abbas Ali, who has defended several cases involving transgender women and has spoken publicly about the issue, innocent verdicts are issued in court cases where there is evidence of a GID diagnosis,[35] although one transgender women told Human Rights Watch that the court ignored her GID diagnosis and sentenced her to six months in prison.[36]

Like many other transgender women, Tharwa has a document from the governmental Psychological Medicine Hospital, with seal from the Ministry of Health, stating that she has GID. Not only does this document not protect her from arrest, but the police refused to include it in her file.[37] Human Rights Watch found this refusal to acknowledge medical reports repeated in all 19 cases we documented where the reports were presented to the police. In one instance that Human Rights Watch recorded, the Kuwaiti criminal court issued a suspended six-month jail sentence to Tharwa in November 2009, even though she submitted her medical papers confirming her GID diagnosis to the judge.[38]

Fatwas

Islamic legal opinion in both Sunni and Shia jurisprudence is divided on the matter of sex reassignment surgery and gender correction, although several high level fatwas (rulings on a point of Islamic law given by a recognized authority) condone it.

The leading Sunni school of theology led by Al-Azhar Mosque in Cairo has issued at least one legal interpretation recognizing the legitimacy of seeking sex change operations. In a 1988 fatwa, the late Egyptian Grand Mufti of the Al-Azhar, Mohammad Sayed Tantawi, issued an edict in response to a request by Sally (Sayid) Abdallah Mursi, a transsexual woman student Al-Azhar’s Medical School for Boys in Cairo.[39] One year shy of graduation, Mursi underwent surgery and attempted to transfer to the girl’s school, but was rebuffed. She won two subsequent legal rulings, but the school ignored them. It also blacklisted her from admission to other medical schools.[40]

Tantawi issued a fatwa that recognized that Mursi’s change was necessary for her health, but required her to dress, behave, and comply with all obligations of Islam for women, except for marital obligations, for one year before the operation. The fatwa was the first positive Sunni ruling about sex changes, allowing them in cases where there is a clear medical condition, which a GID diagnosis would seem to constitute.[41]

The most prominent Shia fatwa on sex changes came in 1987 from Grand Ayatollah Sayyed Ruhollah Musavi Khomeini, an Iranian religious leader and politician and leader of the 1979 Iranian Revolution. For years before, transsexual rights activist Maryam Hatoon Molkara, previously known as Fereydoon, had been lobbying him to grant her religious authorization to legally become a woman. After finally being granted an audience with the ayatollah, he issued a fatwa condoning both SRS and legal gender correction. This fatwa is widely regarded as the edict that authorizes such operations in Iran.

In 2008 in Kuwait, senior Sunni cleric Sheikh Rashid Sa’ad al-Alaymi issued what initially appeared to be a fatwa in a local newspaper in which he stated that SRS should be allowed in cases where gender identity disorder is diagnosed.[42] Al-Alaymi’s statement, which came on the heels of the Kuwait National Assembly’s passing the amendment to article 198, claimed it was a mistake to accuse those with GID of “imitating a member of the opposite sex,” because “they did not choose this of their own will or because it gives them pleasure, but it is something that comes from God in his infinite wisdom.”[43]

However, after heavy attack from the Kuwaiti religious establishment, Sheikh Rashid claimed the newspaper misunderstood and misattributed the document it published in his name. In a letter to Al-Rai newspaper, Sheikh Rashid said that the statement was not a fatwa, but research he had compiled to send to a medical doctor.[44] Religious figures in Kuwait have not issued further legal pronouncements on the matter since the ruling.

II. Police Abuse Against Transgender Women

The evidence and statements gathered by Human Rights Watch from transgender women all contain similar and harrowing tales of abuse by police. The most common complaint made by the women to Human Rights Watch was of police sexual violence and humiliation. The following sections outline the main findings arising from the evidence gathered and detail police abuse of transgender women, as well as procedural violations during arrest and detention.

Sexual Violence, Physical Abuse, and Torture

If anyone touches me, I have no right to complain. My body is there to be violated. This is what the government did: it turned my body into a receptacle for depraved Kuwaiti men. And then they call me deviant? They punish me?

—Samira, 26, Kuwait City, February 11, 2011

They have turned us into prey for society; we have become victims to anyone’s whims just to avoid prison. Everyone is a threat. Every time we go out, we take a risk.

—Rima, 27, Kuwait City, February 10, 2011

The ramifications of article 198 go beyond unfair detention and imprisonment, opening the door to a number of other violations, all with little recourse for redress. Every one of the 40 transgender women interviewed by Human Rights Watch reported that she suffered some form of sexual abuse at the hands of police, most of them unreported due to fear of reprisal. The ubiquitousness of these stories among Kuwait’s transgender population and the manner in which the abuse was carried out suggest that this sexual violence is a result of both the vague wording of the law (criminalizing an unspecified appearance) and the way police apply it arbitrarily.

Transgender detainees have consistently reported beatings, torture, sleep deprivation, solitary confinement, humiliating and degrading treatment, sexual assault, and harassment by police. Transgender women have reported that the sexual assault they endure at the hands of the police can take several forms, including harassment such as touching and groping, rape, and blackmailing them into non-consensual sex by threatening to arrest them if they did not comply.

Articles 53, 159, and 184 of the Kuwaiti Criminal Code forbid torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment, and Kuwait ratified the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment in March 1996. In its concluding observations published in June 2011, the UN Committee Against Torture recommended that “a crime of torture, as defined in article 1 of the Convention, be incorporated into the penal domestic law of the State party ensuring that all the elements contained in article 1 of the Convention are included.”[45] The committee also recorded 632 trials of cases of torture, ill-treatment, and corporal punishment in Kuwait. In 248 of those cases perpetrators were punished, although Kuwait’s government failed to give information about the exact penalties applied to the convicted.[46]

However, Kuwaiti law still does not clearly define torture, and torture by police and other security forces continues, according to Geneva-based human rights organization Al-Karama.[47]

Moreover, on January 22, 2007, the Committee against Torture published a decision, V.L. v Switzerland, concluding that sexual violence committed by police officers acting in an official capacity constitutes torture.[48] The committee’s conclusion stated:

The acts concerned, constituting among others multiple rapes, surely constitute infliction of severe pain and suffering perpetrated for a number of impermissible purposes, including interrogation, intimidation, punishment, retaliation, humiliation and discrimination based on gender. Therefore, the Committee believes that the sexual abuse by the police in this case constitutes torture even though it was perpetrated outside formal detention facilities.[49]

Several torture scandals involving police rocked Kuwaiti society in early 2011. The most notorious, a case involving the death of a detainee due to torture while in police custody, resulted in the resignation of Minister of Interior Sheikh Jaber Al-Khaled Al-Sabah. A parliamentary committee that investigated the death of the citizen, Mohammed al-Mutairi, said that he had been tortured for six days before dying in the Ahmadi Criminal Investigation Department on January 11, 2011.[50] The public prosecution investigated 20 individuals for involvement in the incident, 18 of them policemen.[51] The court case is ongoing. This incident received extensive media attention due to the brutality of events leading to al-Mutairi’s death and the heated debates it caused in the Kuwaiti parliament between opposition and pro-government MPs. Most other cases go unnoticed.

Transgender women have also reported degrading and humiliating treatment by the police, such as being forced to strip and being paraded around the police station, being forced to dance for officers, sexual humiliation, and verbal taunts and intimidation. A common complaint among transgender women is police blackmail for sex on threat of arrest, an act that constitutes sexual assault. Rima, 27, recounted a typical encounter:

In October 2009 I passed a checkpoint right outside my university’s gate. I got scared of course and turned back, but the policeman got suspicious. I stayed on campus for five hours until I was sure that the checkpoint moved. The next day I saw the same checkpoint and the same police officer. He found out which car was mine and as I was walking towards it he stopped me and asked me for my ID. I gave it to him, and immediately the sexual harassment started. He forced me to take off my top so he could see my breasts, right in the middle of the parking lot. When I told him he had no right to treat me like this, he said, “Either you take my number and meet me for sex or I will take you to prison.” I had no choice. For the rest of the time I was in college I had to keep seeing him.[52]

Khouloud said that she was disappeared for two weeks after police stopped her at a checkpoint and subjected her to a range of abuses:

When the police officer took out IDs, he said he couldn’t believe I was a male. He forced his arm through the car window and grabbed my bag. I tried to explain to him that I am a woman, I feel like a woman. He asked me if I had transitioned, and I told him I hadn’t. He raised his eyebrows and said, “Oh, so it still works?” I couldn’t believe it. He asked if I would come with him to his apartment. I asked him why, and he just said, “You know why.”

I was so frightened, but I knew I had to get out of it somehow, so I agreed to meet him later. He took my number, and before letting me leave he felt up my crotch. He kept calling me after that but I never answered. He found out where I worked. One day after leaving work, I found him standing right outside my office building waiting for me. He was furious, he wanted to punish me for not having sex with him. He gave me one last chance: his apartment, or the police station. I refused to go home with him, so I ended up in handcuffs. He called the police station and told them that he’s bringing in a third sex for them to “make a man of.”

There were five officers total with me at the station. They took me to a small room with no cameras. They beat me, made me take my clothes off and touched me everywhere. One of them took his pants off and tried to make me touch him. I was crying the whole time, begging them to stop. They put music on and made me dance naked for them. They would touch me and tell me how pretty I was, then beat me and tell me to be a man. They kept asking me to have sex with them but I kept refusing so they would hit me more. They punched me, beat me with canes on my legs and then forced me to walk around so the blood wouldn’t coagulate and if I faltered they would hit more.

Khouloud spent two weeks detained in the Criminal Investigation Department never being brought before a judge—as required by the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR)—[53] without her parents knowing where she was, she said, and during which police regularly beat and sexually abused her:

For two weeks I did not see the sun, I didn’t know if it was night or day. They tortured me psychologically, telling me that I would be released soon, in two hours, in one hour, and then they would tell me I’m going to prison for a year. Every day they paraded me around in my underwear and touched me. In the end I just started showing them my tits myself to spare myself the humiliation of them forcing me to strip. I saw the worst things possible. They would torture people in front of me and tell me that’s what they were going to do to me.

They finally released me after shaving my head and making me sign a paper that said that they had caught me on the street in full makeup with a throng of men behind me, causing a disturbance.[54]

The frequency with which transgender women told researchers that police gave them the choice of having sex with them or going to prison suggests this population serves as easy sexual prey for police, who have allegedly employed threats, intimidation, and physical violence to ensure that these incidents go unreported. Samira, for example, was arrested four times, the last time in the beginning of 2010, when she said that four police officers raped her while in detention and then threw her from a moving police car onto the street. She was not charged with any crime, and did not file a complaint for fear of reprisal.[55]

Farah, 25, told Human Rights Watch another all-too common story of sexual assault at the hands of police. In October 2009 two policemen stopped her and a friend as they left a mutual friend’s apartment early in the morning. According to Farah, the policemen took a liking to her friend, and told them that they would not arrest either, and would let Farah go on condition that her friend go with them in their car:

She had been arrested twice before, and did not want to go through the pain and humiliation of it again. So she went with them. When I called her that evening to ask what had happened, it was as I suspected: they both raped her in the police car.[56]

Haneen suffered terribly at the hands of the police. She recounted one incident where two police officers attempted to break in to her apartment and rape her in June 2009:

As I was opening my door they grabbed me and I lunged myself inside. Half of me was inside the apartment and half outside, so they tried to pull me out completely. They know they have no right to arrest me inside my apartment without a warrant. What were they going to do, arrest my legs? They tried to reason with me, telling me that they find me pretty and just want to talk to me. That was before they got really angry and yelled at me that they were both going to fuck me. I managed to push them off and enter my apartment. One of them was yelling at me to come out or he would get a warrant to arrest me. When I pulled out my camera to take a picture of them they ran away. As they left one of them said that they would be watching for me downstairs to arrest me when I walk into the street.[57]

The second time Ghadeer was arrested, in 2008, she said she was dressed in a track suit outside a restaurant in broad daylight. She reported that the arresting officer let her go after he forced her to give him her number to arrange for a date. That same year, she said a police officer followed her into a mall and threatened to arrest her:

I begged him not to but he started to pinch me on my ass and breasts and pressed himself up against me…. His hands were all over me. He said he wouldn’t arrest me if I agreed to go up to the roof where there was no one and have sex with him there. The roof turned out to be locked so he got flustered and decided to take my number instead, telling me he would come to my apartment after his shift was over. After that I changed my number.[58]

Abeer, 29, recounted how police arrested and abused her and her friend for appearing dressed in women’s clothes, including detaining them in an informal place of detention:

Before the law was passed in 2007, I was detained twice because of the way I look, and the police never even told me what law I had broken. I was kept in the station for four hours, beaten, and then released.

I was arrested for the third time in March 2008 with a friend of mine. We were stopped at a checkpoint and arrested after they saw that our driver’s licenses state our sex as male and we were dressed as women. By law, we were supposed to be transferred to the police station to be investigated or charged. Instead, they took us to their friends at the garage next to the Salmiya police station where police patrol cars are parked. Inside, they took pictures of us with their personal camera phones, probably to make fun of us to their friends and brag that they had arrested transsexuals. They told us they were going to use the pictures for our criminal files, but they had no right to take them in the first place; it’s only at the station that they can do that.

They kept us there for an hour and half humiliating, ridiculing and cursing us. They beat my friend with a heavy stapler; she was bruised for weeks after that. She stood strong, so they punched and kicked me even more because they could tell I was afraid. After they saw my friend’s shoulder turn blue from the beating, they made sure to hit us in places where there would be no bruises, so I got punched in the stomach a lot. One of them touched my friend’s breasts,[59] and when she told him that he can’t do that, he said it’s not sexual harassment because she is really a “man.”[60]

Ghadeer, 22, is a working class transsexual Bidun—one of a group, now estimated to be 106,000 stateless persons who claim Kuwaiti nationality but have been in legal limbo for the past fifty years.[61] All Bidun have the status of “illegal residents.”[62] Over time, their precarious position has contributed to poverty, and limited access to education and health care. The combination of Ghadeer’s gender identity, statelessness, and poverty has amplified her vulnerability at the hands of the police and society at large. The dual stigma attached to being Bidun and transsexual greatly increased her vulnerability to extortion and violence.

Since 2008 Ghadeer said that police had arrested her nine times for allegedly violating article 198 and detained her each time between four and twelve days. In 2009, a Kuwaiti court fined her 1000 KD ($3000) for “imitating the opposite sex.” She said that she has been unable to find and keep a job due to her gender identity and lack of citizenship, and has had to leave her apartment several times because of continued harassment by both police and civilians in her neighborhood.[63]The first time Ghadeer was arrested was in March 2008, while she was driving with two Kuwaiti citizens and two Bidun men, wearing a unisex training suit covered by a dishdasha(traditional Kuwaiti male garment):

As soon as the police saw us at the checkpoint they pulled us aside and searched us. They searched the trunk, even though they have no right, and found my lipstick and makeup. They dragged me from the car by my hair, kicked and punched me and took us all to the Salmiya police station.

There they asked me if I was a man or a woman. I replied that I am a man, and then they beat me yelling at me to confess I was “third sex”. In the end I had to confess from all the beatings even though outwardly I was dressed like a man. The issue is inside me: I am a woman in a man’s body.

They took my phone and started going through my text messages and personal pictures of myself and my family. When I tried to object one of the policemen threw a stapler at me. Then he asked me, “Why are you Bidun?” What kind of a question is that?[64]

Ghadeer and her friends suffered doubly because of their Bidun status. She said that police singled them out for abuse and humiliation that they spared their two Kuwaiti friends:

They abused me and my two Bidun friends and did nothing to the Kuwaitis. They even took a trash can full of dirt and cigarette butts and dumped it over my Bidun friend’s head, and forced another Bidun to do push-ups with a radiator on his back.

One of the policemen then told me to strip, but I refused. He forcefully lifted my dishdasha and when he saw the training suit underneath he asked to see my underwear. The other police officer beat me and forced me to take everything off in front of everybody, made me turn around to see my ass, my breasts.

At one point, Ghadeer said, her mother called her phone.

The police officer answered her and told her, “Your son is third sex,” and then hung up, just like that. My mother is old, she is sick, she is a Bidun. Why would he torture her like that?

Both Kuwaiti citizens were let go without any criminal charges. The Biduns were taken to the Criminal Investigation Department. Ghadeer’s mother visited “every hospital and every police station in Kuwait” but was simply told there was no one there with her child’s name. Ghadeer’s time in detention was punctuated by abuse and humiliation.

They would call us to the door just to spit on us and walk away. We'd sleep on the floor without any covers and they would purposely turn on the air conditioning on the highest setting. They took the makeup and the clothes they had found in the trunk of the car and forced me and my Bidun friend to put them on. In the police report they wrote that they caught us red-handed in full impersonation of the opposite sex and included photographs they took of us in the women’s clothes they forced us into as evidence.

When I asked to pray I wasn’t allowed to change from the women's clothing they forced me to wear. The clothing is inappropriate for praying as it is figure-hugging and they refused to let me change.

Finally they took us to the investigating officer, and while we waited outside his office policemen passing by would just hit us or spit on us on their way. We pleaded with the officer not to call in our fathers. My friend's father is religious, my family is Bedouin, they are a simple, proud, and honorable people. They called them in anyway and beat us in front of them and showed them the pictures they had taken of us after they forced us to wear women’s clothes. They swore at us and made derogatory comments in front of them, which was humiliating to our fathers.

Before they were released, Ghadeer and her friends were forced to sign a declaration saying they would never imitate the opposite sex or be found in suspect places. “In the report they wrote down that I was stopped in a ‘suspect place.’ Is the 5th circle highway a public place or a suspect place?” she asked.

After that my whole extended family found out. My sister was divorced by her husband because of this and my friend had to repeat the school year because he missed his exams in the time we were in detention. And my mother got even sicker.[65]

In mid-2008, Ghadeer was arrested for the third time in a coffee shop in the busy Salmiya district while she was with an older Lebanese woman and her grandchild:

The police officer who saw me called in a patrol, and eight officers came to pick me up. Eight, just for me. They took the child from my lap, placed him on the table, and then cuffed my hands and my feet and walked me out in front of everyone as if I were a murderer. I was in a track suit and had my long hair tucked under my baseball cap. When they arrested me, they took my cap off so that everyone could see my hair.

Ghadeer was taken to the Criminal Investigation Department, where she was detained for four days.

I had just had breast implants so I was bleeding the entire time from sleeping on the floor and from the way they grabbed and pinched me. I was in so much pain. They saw the blood but didn’t clean it up or call in a doctor.[66]

Procedural Violations

Interviewees frequently cited procedural violations in police arrests and detentions of transgender women.

Some of these violations appear to be rooted in lack of clarity in the amendment to article 198—specifically, its failure to explain what constitutes “imitating the opposite sex”—among its central provisions—allowing police complete freedom to define what violates the law.

According to Kuwaiti lawyer Abbas Ali, who has defended a number of transgender women and who has spoken about the issue in the media, most arrested transgender women are not prosecuted by the state, but are detained and released with a warning, keeping them in jail for any time between a few hours to over a week.[67]

Furthermore, despite Kuwaiti and international laws requiring due process guarantees for detainees, transgender women have reported arbitrary detention with no regard to their due process rights. Article 9 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) to which Kuwait acceded in 1996 guarantees everyone the “right to liberty and security of person” and protection from arbitrary arrest or detention. The right to security obligates the state to take reasonable steps to protect individuals against threats of physical violence whether from agents of the state or third parties. Article 9 requires that anyone arrested or detained on a criminal charge be brought promptly before an independent judge. Article 31 of Kuwait’s Constitution also protects against arbitrary arrest and detention, a right supported by article 60 of Kuwait’s Code of Criminal Procedure, which limits police custody to four days without judicial authorization.

Despite these legal requirements, 12 out of the 39 transgender women who had been arrested and whom Human Rights Watch interviewed said that police detained them illegally for more than four days, sometimes up to 20. Seven were also not allowed to communicate with their families or inform anyone of their arrest, and the police refused to acknowledge the detention of four of those to their families, act that constitutes an enforced disappearance, a serious human rights violation.[68] Additionally, all 39 arrested individuals whom Human Rights Watch interviewed said that police did not allow them access to a lawyer during interrogation or inform them of this right, a direct violation of article 75 of the Code of Criminal Procedure.

According to Ali, police have no right to conduct body inspections without permission from the public prosecutor, yet it is common practice for them to force transgender women detainees to strip in front of them to determine, for example, whether they are wearing female underwear or whether they have had breast implants, particularly if they were arrested while wearing male or gender neutral clothing. Such behavior is often accompanied by humiliating sexual harassment.[69]

Unless police actually catch someone in a clear case of “imitation” (a biological male wearing obviously female clothes), they have no legal right to call in a forensic doctor for a bodily inspection).[70] Yet 15 of the transgender women interviewed reported that police subjected them to such inspection regardless of their state of dress at the time of arrest. Ban, 22, said police caught her wearing a dishdasha while in her car, then forced her to undress on the street to reveal she was wearing female underwear. They arrested her on that basis.[71] Article 17 of the ICCPR guarantees that, “No one shall be subjected to arbitrary or unlawful interference with his privacy” and further guarantees the right to protection from such interference. Forcing an individual to undress in public to assess her undergarments constitutes a clear violation of the right to dignity and privacy.

All of the transgender women we spoke to also reported that police forced them to sign a statement that they would not “imitate the opposite sex again.” They also claimed that police accompanied these forced confessions with humiliation, abuse, torture, sexual harassment, and sometimes sexual assault before releasing them.

For Tabtabai, the author of the law, arresting and forcing transgender individuals to sign these declarations ought to constitute an effective deterrent, although the facts say otherwise.[72] Approximately half of the 39 arrested transgender women interviewed for this report were arrested more than once, some up to six times. Twelve of the transgender women interviewed were arrested wearing gender-neutral or male clothes, including the traditional dishdasha, while three were arrested for “wearing a feminine watch,”[73] “having a smooth face,”[74] and “having a soft voice”.[75] Ghadeer, the 22-year-old transsexual woman who was arrested nine times, told Human Rights Watch:

Every time they catch me they expect me to repent. If I wear women's clothes, I get caught. If I wear men's clothes, I get caught. If I wear something in between, I get caught. And in all these situations I get sexually harassed. You begin to understand that getting arrested becomes part of your everyday life.[76]

In fact, transgender women trying to pass as men are often at even more risk of arrest because their male attire clashes considerably with their overall female appearance, attracting police suspicion. Khouloud, 26, said: “When we wear men’s clothes, we become more conspicuous. It is obvious we are hiding something, with our caps, sunglasses, shoulders hunched down. We attract even more attention; we look like women in drag.”[77]

Amira’s StoryAmira, a 26-year old transgender woman, told Human Rights Watch: In March 2008 I went to visit my friends wearing a tracksuit. I had long hair. A man began following me in his car trying to flirt with me. When I realized he was from the criminal investigation department, I pulled over. He called a five-car police patrol to come get me. Five cars, just for me, as if there are no real problems in the country. When they put me in one of their cars, a police officer told me that if I showed him my chest he would let me go. I had no choice, so I lifted my shirt. He played with my breasts, but still took me to the Criminal Investigation Department anyway. I was put in a room full of policemen and forced to take off all my clothes, but I refused to take off my underwear. They beat me, and took pictures of me naked and crying with their personal cell phone cameras; they eventually forced me to take off my underwear. They stood there laughing, making me pose for them and taking pictures. There were no questions, no investigation, and they refused to let me call my parents. They just threw me in a cell and insulted and humiliated me. I spent two days in detention. Every hour someone would open the door, laugh and humiliate me, and then leave. The next morning I was taken to the vice unit and paraded from office to office just to be put on display. Even the questions they asked were ridiculous: “How long have you grown your hair?” One of the policemen finally took pity on me and called my parents. When my brother came to pick me up they humiliated him for having a brother like me and telling him his sister must be a whore. One of the policemen emptied my wallet on the floor to make me bend over and pick the contents up in front of my brother to humiliate him even more. They made me sign a declaration stating that I would never imitate a member of the opposite sex again.[78] |

Fear of arrest, and the actual experience of arrest and detention, is so strong that many transgender women live in what amounts to self-imposed house arrest. In Amira’s words:

After that experience, I do not leave the house anymore. I go to work and come straight back home. Every time I leave the house I can never guarantee that I will come home. My parents call me to check on me if I am even two minutes late, even they live in fear now.[79]

The impunity and arbitrariness with which police arrest and mistreat individuals has placed Kuwait’s transgender population, and in particular transgender women, under constant threat. Seventeen transgender women we interviewed have reported being stopped at checkpoints, asked for their ID cards, and then arrested because the police determined that their gender presentation did not match their stated sex, regardless of what they were wearing.

Abeer, 29, says that when the police arrested her and her friends in March 2008 for the third time, they transferred them to the Criminal Investigation Department in Salmiya for five days, even though the law only allowed them to be detained for four without instruction from the public prosecutor to extend detention pending investigation.

For the first two days they didn’t allow us to call anyone or inform our families or lawyers. On the third day they interrogated us and charged us with violating amended article 198. Then they shaved our heads like sex offenders and released us on a bail of 100 Kuwaiti Dinars (US$360). Of course we had to sign a declaration that said that we would never imitate a member of the opposite sex or frequent “suspect” places or be seen after midnight in public, even though they had caught us at 10 a.m. on a Friday in our car.

The court fined Abeer and her friend 1000 dinars each ($3,600) and sentenced them to three years probation.[80]

Transgender women are police targets just by being in public. Because of numerous checkpoints and police patrols around the city, some transgender women have said that the risk of arrest is often too great to venture out. After being arrested twice in the space of 18 months, Maha, 26, fears going out at all because of her own experiences and those of the transgender people around her:

I am a human being. I need to go to the supermarket to buy necessities for my house. If I get sick, I need to go to the hospital. I have to go to work to make a living. But now every time I leave the house I think that I may not come back. Things people take for granted, like going to a restaurant, seeing friends, going to the cinema, these are all things I cannot do anymore.[81]

These fears are not unfounded. In October 2010 Abeer said that police arrested her for a fourth time outside a supermarket at 11 a.m., while she was wearing Western-style men’s clothes and a baseball cap:

A police car pulled over right behind me as I was parked outside the supermarket to buy cigarettes. The policeman went in the store and then approached my car. I was afraid of course, but I thought I was safe because I was dressed as a man. He asked me for my ID and then told me I had to come with him to the police station in Adan. He gave me two options: either he rides in my car to the station or he humiliates me in front of everyone and forces me into his patrol car. I was scared, so I told him to drive my car as he requested. I was stupid. Of course he didn’t take me to the directorate; instead he took me to the police patrol car parking garage right next to it.

He told me that he would let me go, but on condition that I show him my breasts. I protested, but he told me that I’m nothing but filth and that anyway it’s OK because I’m a boy like him. I was afraid of what would come next, so in a last effort I showed him my medical document that said I have GID. He looked at it and said, “Oh, so you’re crazy. I clean the streets from filth like you.” I refused to show him my breasts and begged him to let me go, so he hit me and pulled me by the hair into a police car to the criminal investigation department. For three days my parents did not know where I was.[82]

In a clear violation of the rights of detainees, many transgender women said police refused to allow their families and lawyers to visit them in detention and at times even denying to them that their relatives were in custody:

They had taken my mobile phone at the station, but I had another one that I hid. The second day I called my mother and told her what happened. My father and brother came to the station every day for the nine days I was there, but the police told them that they had no one there by my name. They didn’t even let my lawyer in. My father was able to sneak in once. I saw him, but I hid because I didn’t want him to see me like this. I made a mistake, I should have spoken to him. One of the officers saw him and kicked him out again. Then the investigating officer asked me if my father was in the Ministry of Interior or the police or army, because in those cases they let the detainees go. My father is retired.

My father brought my medical papers with him, which were official documents from the government psychiatric hospital stating that I have gender identity disorder. This paper has the stamp of the Ministry of Health. The police refused to take them and add them to my file.[83]

Sara said police placed her in solitary confinement in the Salmiya station for nine days:

On the first floor, there are detention cells for men, women, and minors. On the second floor, there were around 40 solitary confinement cells. This is what they call the “hotel.” Each room was about two by one meters. It was terrifying. I was really cold, and they didn’t give me any blankets, I would sleep bare on the floor. There were only transsexuals in solitary [confinement] when I was there.

In solitary [confinement] they would rarely allow me to go to the bathroom. They gave me an empty water bottle to urinate in. The food was disgusting; they would throw it on the floor. I didn’t eat anything, for nine days I lived on water and juice. They let me out twice just to leer at me and make fun of me. Every time the shift changed I would be asleep, and a new policeman would kick on the door until I woke up; they would make me stand, turn around for them to leer and gawk at me and insult me, and then leave.

They have a room in the Criminal Investigation Department that they call the “VIP room.” It has a bed and a private bathroom. It’s one of the only places that doesn’t have a camera. I would hear heels clicking around in that room. One of my friends who had been arrested told me a police officer took her there and had sex with her. One officer took me there and tried to sweet-talk me into sleeping with him. I refused.[84]

Several transgender women told Human Rights Watch that on several occasions police arrested them while wearing male clothes, but forced them to change into women’s clothes at the station before photographing them for their criminal files. Khouloud said that a policeman arrested her in 2010 after she refused to have sex with him. She spent two weeks in the Criminal Investigation Unit, where security forces beat and humiliated her:

When I was arrested I was wearing an XXL-sized tracksuit, and as you can see I’m small. I am careful with these things. When they took me in to the station, they beat me incessantly and made me wear women’s clothes and put on makeup, stuff that they had confiscated from another transgender woman they had arrested previously. They took pictures of me like that and claimed that that is how they found me. It was purely for revenge because I refused to give into the policeman’s sexual blackmail.[85]