Summary

As a patient, you have to struggle with very low self-esteem and also have to fight with negative attitudes from society … it is like a death sentence.

—Doris Appiah, referring to her five years in a Kumasi prayer camp, Accra, November 2011

Doris, 57, has bipolar disorder, a mental disability characterized by serious shifts in mood, energy, thinking, and behavior.

At 22 her father took her to a prayer camp, a Christian religious institution in Kumasi, south central Ghana. For five years she languished at the camp, which was being run by a self-described prophet who claimed to receive instructions from God about how to treat individuals like Doris, whom he said were “possessed by demons.”[1] At some point she was tethered by a rope to a wall for about two months, forced to fast for days at a time, and left to sleep, bathe, and defecate in the open.

Finally, in 1982 at the age of 27, Doris escaped to the streets of Kumasi, where she wandered barefoot, dirty, and disheveled. “People would see me and run off, calling me a ghost,” she said. “They would not share a bucket [of water] with me to bathe. One person gave me food on a plate, and after I ate, they threw the plate away.”

Before and after her time at the prayer camp, she spent time in Accra Psychiatric Hospital. During one such occasion in 2010, she told Human Rights Watch that she witnessed people being injected with medications against their will, and nurses beating patients who failed to respond to instructions. “I used to feel lonely … ashamed … [being in the hospital],” Doris said. “What I needed was a clinical psychologist to talk to and community-based rehabilitation, but these services are not easy to come by.” After 19 years in prayer camps and psychiatric hospitals, Doris was discharged in 1989, and she started receiving support from BasicNeeds, a local organization that serves people with mental disabilities. BasicNeeds introduced her to their other members for peer support, and to community nurses. Gradually her health improved, and in 2005 she started advocating for rights and better living conditions for persons experiencing what she had gone through.

***

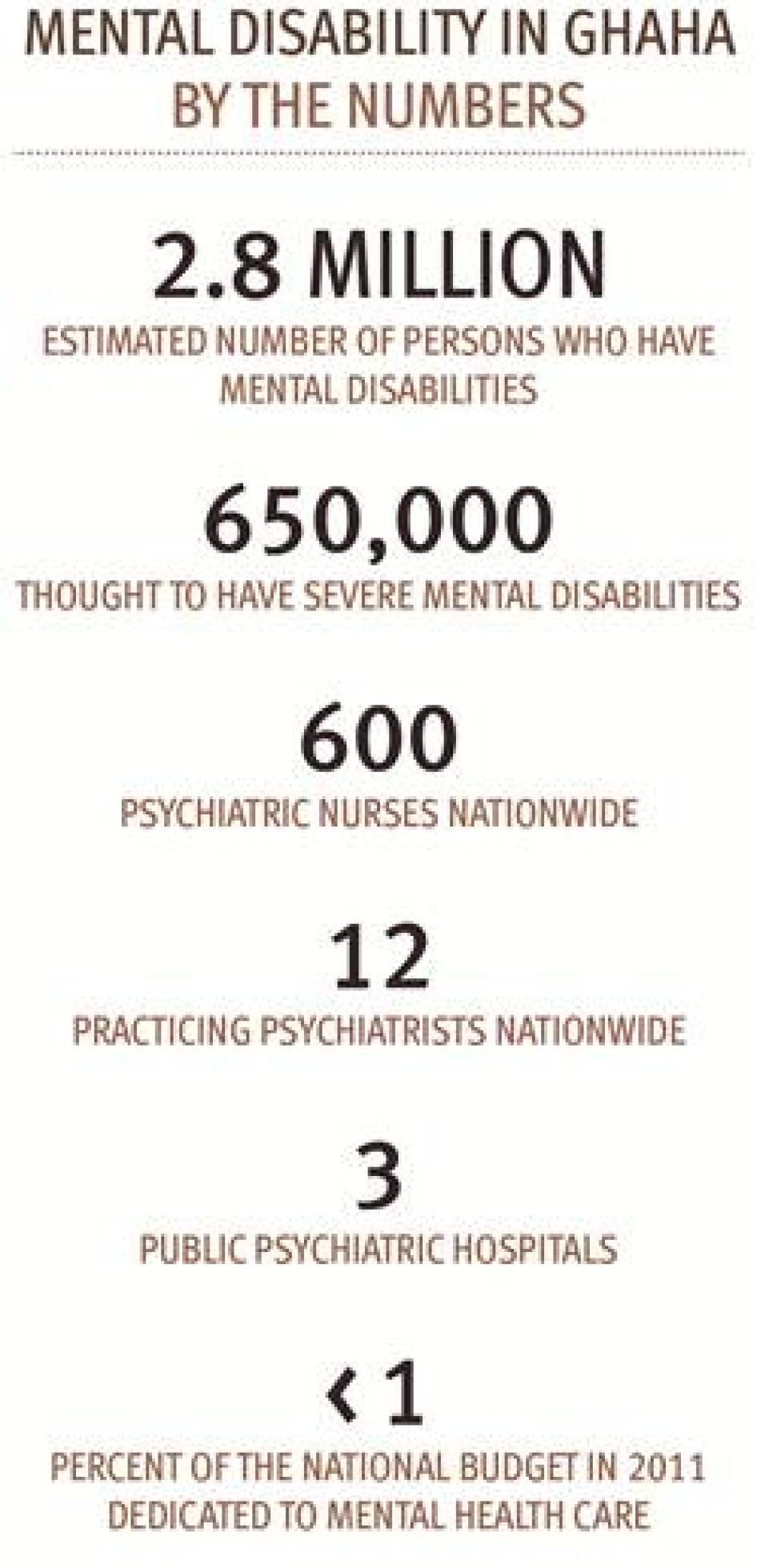

An estimated 2.8 million persons in Ghana have mental disabilities. Of these, 650,000 are thought to have severe mental disabilities. In the country mental disability is widely considered—even by persons with mental disabilities themselves—as being caused by evil spirits or demons.

Focusing on the southern parts of the country, this report examines the experiences of persons with mental disabilities in Ghana in the three main environments in which they receive care: the broader community, the country’s three public psychiatric hospitals, and residential prayer camps. Spread throughout the country, prayer camps are privately owned Christian religious institutions with roots in the evangelical or pentecostal denominations established for purposes of prayer, counseling, and spiritual healing, and are involved in various charitable activities. The camps are run by prophets, many of them self-proclaimed. Some of these camps have units where persons with mental disabilities are admitted, and the prophets seek to heal persons with mental disabilities with prayer and traditional methods such as the application of various herbs. The prophets, or pastors, and staff at these camps have virtually no mental health care training. Human Rights Watch has not been able to ascertain the number of prayer camps in Ghana, but there is a general belief in the country that there are several hundred such camps, operating with virtually no government oversight.

However, the primary role of prayer camps, according to those who spoke to Human Rights Watch, is not to treat persons with mental disabilities. While each of the eight camps Human Rights Watch visited has a unit for treating persons with mental disabilities, such treatment was the smallest component of the work being done at the camps. There was considerably greater emphasis on various forms of spiritual and temporal activities like worship and commercial agriculture.

Private psychiatric hospitals also exist but can treat only about 100 inpatients in total at a time and are too expensive for most Ghanaians.

The research for this report is based on visits to eight prayer camps and three psychiatric hospitals, and interviews conducted between November 2011 and June 2012 with nearly 170 persons including persons with mental disabilities in psychiatric hospitals, prayer camps, and in the community, caregivers, government officials, health service providers, representatives of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), including those working on disability rights and human rights more broadly, and religious leaders. Also interviewed are representatives of United Nations (UN) agencies and those of international groups working in Ghana.

Human Rights Watch found that persons with mental disabilities in Ghana often experience a range of human rights abuses in the prayer camps and hospitals that Human Rights Watch researchers visited. These patients are ostensibly sent to these institutions by their family members, police, or their communities for help. Abuses are taking place despite the fact that Ghana has ratified a number of international human rights treaties, including the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), which was ratified in July 2012. These abuses include denial of food and medicine, inadequate shelter, involuntary medical treatment, and physical abuse amounting to cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment.

Human Rights Watch also found that there were few government-supported, community-based mental health services—including housing, healthcare, and medical care—even though health officials in Ghana told Human Rights Watch that they offer the most cost-effective and appropriate care for most Ghanaians with mental disabilities. Most of the people with mental disabilities interviewed by Human Rights Watch in the course of conducting this research said they preferred to receive treatment on an outpatient basis while living with their families.

Those who received daily support and were interviewed by Human Rights Watch said they did so via local NGOs, which lack the means to support the hundreds of thousands of persons who need similar assistance in Ghana.

Lack of such services, combined with pervasive negative community attitudes towards mental disability, makes integration of persons with mental disabilities into community life extremely difficult, and some are abandoned entirely once they enter a mental health care facility. In one extreme case, researchers reviewed the file of a 75-year-old woman who is believed to have lived on the ward at Ankaful Psychiatric Hospital in the Central Region for over three decades because her family never came to collect her.

In recent years the Ghanaian government has taken some steps to improve the care of people with mental disabilities, including reducing overcrowding in state psychiatric hospitals and passing the Mental Health Act in June 2012. The Mental Health Act, for the first time, laid out a clear procedure for persons with mental disabilities to challenge continued detention. Parliament has also tabled the Traditional and Alternative Medicine Bill, which seeks to regulate traditional health practices based on theories, beliefs, and experiences indigenous to different cultures.[2]

These are positive steps. However, even with the passage of the Mental Health Act, there is no system in place in Ghana to effectively and routinely monitor prayer camps, meaning that the hundreds of individuals housed in them may still be subject to the grave human rights abuses documented in this report. In addition, provisions remain in the 2012 Mental Health Act that still allow for forced admission, involuntary treatment, and guardianship. Also, it is not clear if enough resources will be allocated towards the implementation of the act’s provisions: in 2011 less than one percent of the national budget was dedicated to mental health care.

Ghana is obligated to respect the rights of persons with disabilities under international and regional legal instruments, the national constitution, and other domestic legislation. Despite these legal provisions, it has done little to ensure that protections are in place and enforced.

People with mental disabilities in Ghana whom Human Rights Watch interviewed endured a variety of human rights abuses in psychiatric facilities and prayer camps. These include, but are not limited to: involuntary admission and arbitrary detention, prolonged detention, overcrowding and poor hygiene, chaining, forced seclusion, lack of shelter, denial of food, denial of adequate health care, involuntary treatment, stigma and its consequences, physical and verbal abuse, electroconvulsive therapy, and violations against children with disabilities.

Involuntary Admission and Arbitrary Detention

Most people with mental disabilities interviewed by Human Rights Watch who live in prayer camps and hospitals were placed there without their consent by family members or the police because they had exhibited restless, confused, or aggressive behavior. Others said that their families had called (or paid) the police to take them to psychiatric hospitals, or that police had picked them up on the streets where they were living. Some had not known where they were being taken until they got to a camp or hospital.

Prolonged Detention

Interviewees told Human Rights Watch that they wanted to leave the hospital or camp, but that some administrators would not permit this because family members did not come to pick them up or doctors were too busy to approve their discharge. In some prayer camps they were unable to leave because, they were told, the prophet was still awaiting a message from God. Some remained even after discharge because their families had abandoned them, and they could not return to their home communities. Human Rights Watch could not ascertain whether persons with mental disabilities subjected to prolonged detention, both in hospitals and in prayer camps, had been before a judge to review or challenge their detention.

The previous mental health law did not provide a framework through which people who are detained in psychiatric facilities could challenge such detention. While the new Mental Health Act now creates a tribunal mandated to hear complaints of people with mental disabilities detained under the act, it is not clear whether those detained for mental health reasons outside of psychiatric hospitals, including those detained in prayer camps, can seek protection under the new law.

Overcrowding and Poor Hygiene

Overcrowding is a serious problem in public hospitals and prayer camps. Facilities stank of urine and feces, and there was inadequate water for drinking or bathing. Toilets were broken, overflowed, or nonexistent.

Overcrowding in Accra Psychiatric Hospital and in some wards in Pantang Psychiatric Hospital, together with significant staff shortages (there are only 12 practicing psychiatrists and 600 psychiatric nurses nationwide), created terrible living conditions for persons with mental disabilities. In two psychiatric hospitals, urine, flies, and cockroaches competed for space in the toilets, and nurses, lacking cleaning equipment, instructed patients to clean the wards and toilets, including removing other patients’ feces, without gloves. In Mount Horeb Prayer Camp in the Eastern Region and Edumfa Prayer Camp in the Central Region, individuals urinated and defecated in buckets in rooms that residents said were emptied only once a day.

Chaining

In four prayer camps Human Rights Watch found that people were either locked in chains inside fully built and semi-permanent structures, or chained to a tree or concrete floor until the pastor or prophet declared them “healed.” Movement was impossible beyond the length of the constraint—usually about two meters. People had to bathe, defecate, urinate, change sanitary towels, eat, and sleep on the spot where they were chained. Human Rights Watch found that many of the 135 individuals at the Mount Horeb Prayer Camp were chained 24 hours a day; some said they had been restrained for several months. Researchers found an individual chained in exactly the same spot where he had been interviewed three months earlier.

Forced Seclusion

Seclusion is one of many forms of solitary confinement. The special rapporteur on torture regards as torture, any prolonged isolation of an inmate from others (except guards) for at least 22 hours a day. In all three public psychiatric hospitals Human Rights Watch found that people were isolated for up to three days, sometimes for refusing to take medicine. Patients complained that isolation rooms lacked proper sanitation facilities.

Lack of Shelter

Shelter was a major concern in all eight prayer camps and in some wards in the three psychiatric hospitals that Human Rights Watch visited. In Accra Psychiatric Hospital, for example, over one-third of individuals in the ward designated for patients sent to the hospital by the courts or police slept outside. In other wards patients sat in the sun all day or crowded in corners where shade provided temporary relief from the blistering heat. The situation was often no better—and sometimes worse—in prayer camps, including two in eastern Ghana where individuals spoke of living without adequate shelter, such as a roof over their heads or protection from the sun, and with constant exposure to mosquitoes.

Denial of Food

Many interviewees spoke of persistent, gnawing hunger from forced fasting in prayer camps or inadequate food in hospitals, and many looked hungry. Administrators and pastors of seven of the eight prayer camps visited said fasting was a key component of curing mental disability and would help to starve evil spirits, “making it easier for the spirit of God to enter and do the healing.” People interviewed said there was too little food, sometimes only one meal a day. Some individuals in Mount Horeb, Edumfa, and Nyakumasi Prayer Camps had to fast for 36 hours over 3 consecutive days in 12-hour stints from morning until dusk. Others, mainly the elderly, fasted from 6 a.m. until noon. Such fasting regimes ranged from 7 to 40 days, and meant that people could not take prescribed medication in camps that allowed the use of such medication.

Denial of Adequate Health Care

Access to health care, including drugs, for both physical and mental health problems was a major challenge for persons with mental disabilities. In psychiatric hospitals patients were responsible for buying their own drugs, especially to treat illnesses such as malaria, although some had no relatives to send to buy the drugs or money to do so. In some prayer camps, such as Nyakumasi, the prophet and camp staff did not allow persons with mental disabilities to use prescription medicine. “Even when you get malaria,” Elijah, a 25-year-old man who had been chained to a tree at Nyakumasi prayer camp for five months prior to Human Rights Watch’s visit, said, “they give you adwengo (palm oil) because angels here don’t allow taking medication.” Only one out of the eight camps visited allowed any medical care for mental health disabilities and other medical conditions at all.

Involuntary Treatment

Human Rights Watch found that persons living in psychiatric hospitals were subjected to involuntary treatment through the use of force, coercion, and sedation. Some individuals said they were forced to take treatment against their will, even when medicine failed to work or led to serious side effects or complications. “I don’t like the medicine I receive,” Peace, a 55-year-old woman admitted at Pantang Psychiatric Hospital, told Human Rights Watch. “The drugs cause my legs to swell, eye pains, and insomnia.” Some patients reported being beaten if they refused to take medication, and staff at all three public psychiatric hospitals admitted using physical coercion, and in extreme cases, involuntary sedation via injection. In some prayer camps people were forced to take local herbs against their will, sometimes through their noses.

Stigma and Its Consequences

Persons with mental disabilities endure stigma and discrimination in the health sector, at home, and in the community. Some of the religious leaders interviewed by Human Rights Watch described persons with mental disabilities as incapable, hostile, demonic, evil, controlled by spirits, useless, and anti-social. Such stigma in turn causes family members to abandon persons with mental disabilities in psychiatric hospitals and prayer camps, neither visiting them nor picking them up after discharge. Some give a false address so they cannot be traced. Stigma also deters persons with mental disabilities from seeking professional services in psychiatric hospitals.

Psychiatric nurses and doctors also said they experienced stigma due to their work in their home communities and among professional peers.

Physical and Verbal Abuse

Human Rights Watch documented severe cases of physical and verbal abuse against persons with mental disabilities in the family, community, hospitals, and prayer camps.

Interviewees said they faced threats of abuse, and actual physical and verbal abuse, for trying to escape, when they complained about pain, and when they failed to take medication, or for failing to follow hospital rules. Harriet, a pregnant woman at Ankaful Psychiatric Hospital, told Human Rights Watch, “Yesterday they [nurses] were drawing blood from me and I was feeling a lot of pain and I said, ‘You are killing me.’ The nurse said, ‘If you shout again, I will put the needle in your mouth.’” One nurse told Human Rights Watch that nurses beat aggressive patients who attacked them.

Electroconvulsive Therapy

Psychiatrists in Ghana continue to use electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), a method of treatment which involves passing electricity through the brain, to treat persons with severe depression. One doctor explained that no anesthesia was administered due to lack of equipment and personnel. The UN special rapporteur on torture has noted that unmodified ECT (without anesthesia, muscle relaxant, or oxygenation) is an unacceptable medical practice that may constitute torture or ill-treatment.

Violations against Children with Disabilities

Children with mental disabilities experienced similar conditions to adults in psychiatric hospitals and prayer camps. Some individuals in Accra Psychiatric Hospital’s Children’s Ward—where almost half the patients were actually adults—had been there since 1980. Lack of staff was particularly acute, and a nurse said they lacked the resources to provide stimulating activities, such as games and television, or the skills to engage the children and handle those with intellectual disabilities. Researchers saw filthy living conditions: in some cases children and adults were lying down naked next to their feces. The situation was even worse in three of the eight prayer camps Human Rights Watch visited. In these camps children were subjected to restraints and other abuses. Solomon, 9, who lived in Edumfa Prayer Camp and was often chained in the same room with about 20 other males told Human Rights Watch, “I have been fasting for 21 days .… I feel pains in my stomach, my head, and my whole body.”

***

Necessary Steps

Immediate attention is needed to address the human rights abuses outlined in this report, particularly to ensure adequate food, shelter, and health care for persons with mental disabilities and to ensure civil and criminal penalties for abusive practices such as chaining, forced fasting, prolonged seclusion, and other forms of cruel and degrading treatment in the hospitals and prayer camps.

As Ghana has now ratified the CRPD, the government should promptly review its disability and mental health laws and policies to ensure compliance with its international legal obligations. It must also adopt legal measures and mechanisms to regulate non-orthodox service providers including prayer camps. This should involve formal registration with government health authorities, regular monitoring of services, and training prayer camp staff.

The government should also develop community-based mental health and support services so that persons with mental disabilities can more easily live in the community and outside institutions such as psychiatric hospitals and prayer camps. Discharging people from psychiatric facilities back to their communities will likely encourage independent living in a less restricted environment.

Realizing meaningful community living requires better equipped regional, district, and other hospitals, which are closer to persons with mental disabilities, and training and recruiting more mental health professionals, social workers, and volunteers, especially at district and grassroots levels. It will also necessitate a range of non-medical support services, such as housing, food, and community education about mental health.

Ensuring that persons with mental disabilities can enjoy their human rights requires efforts from a range of stakeholders. There is need for international partners working in Ghana, including the World Bank, the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), to undertake programs which are sensitive to the needs of persons with mental disabilities.

Key Recommendations

To the Government of Ghana

Immediate Actions:

- Immediately improve conditions in public psychiatric hospitals by ensuring adequate food, shelter, and health care and by prohibiting practices of beating patients, prolonged seclusion, and forced admission and treatment without judicial oversight.

- Take immediate steps to ensure that individuals are not held against their will at prayer camps and hospitals, and to ensure that those in prayer camps are not subjected to forced fasting or chaining and are not denied access to appropriate health care.

Intermediate and Long-Term Actions:

- Develop voluntary community-based mental health services in consultation with persons with mental disabilities and their representative organizations.

- Ensure that persons with mental disabilities and their representative organizations participate fully in planning, implementing, and monitoring government programs on mental health and disability.

- Enforce existing criminal laws on assault to target inhumane practices in psychiatric hospitals and prayer camps, such as chaining and prolonged restraint, mandatory fasting, and treatment without free and informed consent.

- Formulate and implement a national policy on non-orthodox mental health service provision, which should regulate prayer camps as centers for the treatment of persons with mental disabilities to ensure that patients are not involuntarily admitted or detained there, are not abused, and are not given treatment without their consent.

- Train and recruit more mental health professionals to improve the doctor/nurse-patient ratio, and increase the number of non-medical staff in psychiatric hospitals to help nurses with cleaning and other non-medical tasks.

Methodology

This report is based on five weeks of field research in Ghana between November 2011 and January 2012, including visits to Ghana’s three public psychiatric institutions and to eight prayer camps. The research was conducted in three regions in Ghana—Greater Accra Region, Central Region, and Eastern Region—chosen both for the presence of public psychiatric hospitals and the high concentration of prayer camps, according to the Christian Council of Ghana, a local organization working with persons with mental disabilities, and the Ghana Pentecostal and Charismatic Council (GPCC), a body that regulates them.

Human Rights Watch has not been able to ascertain the number of prayer camps in Ghana, but there is a general belief in the country that there are hundreds of such camps, mostly in the southern parts of the country. Human Rights Watch did not visit the northern part of Ghana in the course of conducting this research. Organizations working on mental health and other experts told Human Rights Watch that in the north there are no prayer camps being run by Christian religious institutions, as is the case in the three regions visited by Human Rights Watch. The north is predominately Muslim and its residents usually take persons with mental disabilities to Muslim clerics, known as “malams,” for treatment.

A total of 169 interviews were conducted; of those, 93 were with persons with mental disabilities (9 in psychiatric hospitals, 51 in prayer camps, and 33 living in the community). Of the 93 interviewees with mental disabilities, 52 were women, 36 were men, and 5 were children. Human Rights Watch also interviewed five family members and caregivers of persons with mental disabilities.

Human Rights Watch only visited prayer camps where we had prior information that such camps had a unit for persons with mental disabilities or admitted persons with mental disabilities. Of the eight prayer camps visited, five had varying numbers of persons with mental disabilities. The other three did not have persons with mental disabilities when visited, but had previously cared for them.

Human Rights Watch chose to visit specific prayer camps based on recommendations from local partner organizations, religious councils, and psychiatric social workers in Ghana, as well as independent background research into the camps. Local partners helped in identifying and introducing Human Rights Watch to some of the camps visited.

Among the 21 health service providers interviewed, 2 were psychiatrists, 17 were nurses, and 2 were psychiatric social workers. Interviews were also held with seventeen religious personnel including those who directed and worked within all eight prayer camps visited, pastors of churches, and members of national religious councils.

Human Rights Watch interviewed staff of 20 local disability and human rights organizations and 15 directors and staff of United Nations (UN) agencies and other international institutions including the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the World Health Organization (WHO), the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), and the World Bank. Researchers also spoke with eight government officials, including representatives of the Commission for Human Rights and Administrative Justice (CHRAJ), the Ministry of Employment and Social Welfare, and the Ministry of Health (Ghana Health Service), as well as two members of parliament, including the chair of the Parliamentary Committee on Health and the minority leader.

Interviews were semi-structured and covered a range of topics related to experiences in the mental health system. Before each interview, Human Rights Watch staff informed interviewees of its purpose, the kinds of issues that would be covered, and asked whether they wanted to participate. Interviewees were informed that they could discontinue the interview at any time or decline to answer any specific questions without consequences.

No incentives were offered or provided to persons interviewed. When possible, individuals were interviewed without the presence of staff or administrators. Interviewees were asked if they would like their identity to be kept confidential; individuals who requested anonymity have been given pseudonyms. In certain cases, the names of health care professionals have been withheld to protect their identity.

Interviews were conducted by Human Rights Watch researchers in English, and through translators in Twi, a local language.

Human Rights Watch also consulted with international disability rights experts and mental health experts at various stages of the research and writing and reviewed a number of official documents from the Ghanaian government, as well as relevant reports from multilateral and bilateral donors, UN agencies, and NGOs.

This report does not cover conditions experienced by persons with mental disabilities who are treated by traditional healers, even though these healers take care of a significant number of persons with mental disabilities, especially in the northern part of the country.[3] We chose to concentrate on psychiatric hospitals and prayer camps because they housed higher numbers of people with mental disabilities, and there have been reports in the media and by local and international NGOs about the abuses going on in these institutions. The abuses detailed in this report relate only to the three hospitals and eight prayer camps in the Greater Accra, Central, and Eastern Regions visited by Human Rights Watch. No claims have been made about possible abuses in other prayer camps in these regions or other parts of the country.

Throughout the research, efforts were made to verify claims and information provided by interviewees through direct observations, interviews with staff members at psychiatric hospitals and prayer camps, and review of psychiatric hospital records when available.

In the report, the term resident is used to refer to persons with actual or perceived mental disabilities in prayer camps, including those who did not have or know their diagnosis.

I. Mental Disability in Ghana

Overview

The World Health Organization (WHO) has estimated that there are 2.8 million persons with mental disabilities in Ghana, 650,000 of whom have severe mental disabilities.[4]

There is no specific international consensus on the definition of disability, but the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), the newest international human rights treaty, describes persons with disabilities as including “those who have long-term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairments which in interaction with various barriers may hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others.”[5] Ghana signed the CRPD in March 2007 and ratified it on July 31, 2012. The 1992 Constitution of Ghana in article 75 stipulates that parliament must pass an act or a resolution with the votes of more than one-half of all members for the CRPD to enter into force, and parliament passed such a resolution in March 2012, which confirmed the entry into force of the CRPD before it was officially ratified in July 2012.

In this report, mental disability refers to mental health problems such as depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia. Persons with mental health problems also refer to themselves as having psychosocial disabilities, a term that reflects the interaction between psychological differences and social or cultural limits for behavior, as well as the stigma that the society attaches to persons with mental impairments.[6]

The vast majority of patients in Ghana’s psychiatric hospitals are treated for mental health problems. According to Dr. Akwasi Osei, director of Accra Psychiatric Hospital, 20-30 percent of patients are diagnosed with schizophrenia, 20 percent with bipolar disorder, and 15-20 percent with major depression. Drug-related psychosis affects 8-10 percent of patients and epilepsy was found in 5 percent of patients.[7]

According to a senior health official, mental disability in Ghana is widely considered as having a spiritual origin, caused by evil spirits or demons.[8] This view on the causes of disability was held by all camp leaders that Human Rights Watch interviewed, as well as some persons with mental disabilities (mainly in the community and camps) who believed evil spirits caused their mental conditions.

Although Ghana is a middle-income country with per capita gross domestic product (GDP) of around US$1,300,[9] 40 percent of adults live on less than $2 a day.[10] The quality of, and access to, health care are concerns for most Ghanaians, but poor Ghanaians with mental disabilities confront particular challenges, such as high transport fares from their homes to psychiatric hospitals, which are often several kilometers away, and the high cost of health care. While there are no conclusive statistics about the prevalence of poverty among persons with disabilities in Ghana, some studies found that poor households with persons who have disabilities face significant barriers in realizing their right to adequate health care.[11]

Although there is no clear data about Ghana’s mental health care budget, interviews conducted with officials from Ghana Health Service indicate that it is as low as 0.5-6 percent of the total health care budget allocation.[12] Expenditure of the mental health budget is also disputed, with varying figures showing that between 72 percent[13] and 94 percent of the health budget is spent on remunerations of medical professionals.[14] In 2011 less than one percent of the national budget was dedicated to mental health care.[15]

Treatment and Care Options

Individuals with mental disabilities in Ghana who receive treatment generally have three main care options: public mental health services, prayer camps, and traditional healers—people who use ritual and herbal methods of treatment. [16] Community care providers are another, albeit limited, option. Most people utilize more than one option and sometimes more than one at a time.

Public Mental Health Services

Like many developing countries, Ghana faces staff shortages within the public health system. The problem is particularly acute when it comes to mental health: there are only 12 practicing psychiatrists and 600 psychiatric nurses nationwide, serving over 2 million persons with mental disabilities.[17]

Ghana has three public psychiatric hospitals: Accra Psychiatric Hospital, Pantang Psychiatric Hospital, and Ankaful Psychiatric hospital. [18] The capacity of each is 200, 500, and 250 individuals respectively. Accra Psychiatric Hospital is considerably overcrowded, with numbers ranging from 900 to 1200 at any given period between 2010 and 2012. [19]

Staff shortage was identified as a major challenge by all the hospital staff that Human Rights Watch interviewed in the three hospitals. In Accra Psychiatric Hospital’s Special Ward, formerly called the Criminal Ward because patients arrived under police arrest or court order, three nurses were on duty caring for 205 patients at the time Human Rights Watch visited.[20] One ward at Pantang Psychiatric Hospital had four nurses on duty to care for forty patients with visibly critical needs.[21] According to the director of Accra Psychiatric Hospital, to achieve proper care, Ghana needs to increase the number of nurses in the three psychiatric hospitals almost seven-fold, from the current 600 to about 4,000.[22]

Currently, Ghana has 15 psychiatric social workers serving the whole country, which is especially low given that the 2000 Mental Health Training Policy requires the government to train at least 15 psychiatric social workers every 5 years.[23] Ebu Blankson, head of the Social Welfare Department at Ankaful Psychiatric Hospital, told Human Rights Watch, “We have three social welfare staff… taking care of… 500 patients.”[24]

Ghana started a community psychiatric nursing program in 1975, which evolved into a community mental health system. However in 2003, the latest year for which there are reliable statistics, fewer than half of Ghana’s districts—52 out of 110—had community psychiatric nurses.[25] There are also only three clinical psychologists, out of the eighty who are needed.[26]

In 2003 the government established a National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS), which aimed to make healthcare readily available and more affordable to Ghanaians and eventually replace the user feesystem throughout the country.[27]

Mental health care is not covered by the NHIS, primarily because of the widespread assumption that mental health care in psychiatric hospitals is cost-free.[28] However, patients are often required to buy their own medicines, which are often very expensive.[29]

Persons with mental disabilities in psychiatric hospitals were therefore responsible for buying their own drugs, especially to treat physical illnesses such as malaria, and yet some of them had no relatives and could not buy these medications.[30] Explaining the effects of the shortage, Dr. Akwasi Osei, chief psychiatrist of the Ghana Health Service and director of Accra Psychiatric Hospital, said that the “lack of resources to buy drugs is state-sponsored human rights abuse.”[31]

The Ghana Federation of the Disabled is working with the Parliamentary Subcommittee on Health to improve coverage for persons with disabilities, especially including those with mental disabilities in the NHIS. The NHIS is currently under review,[32] and an amendment bill which would extend coverage to persons with mental disabilities is before parliament and is expected to be enacted before the end of 2012.[33]

Those treated within the public health care system may be inpatients or outpatients within Ghana’s three psychiatric hospitals or in some regional and district hospitals where there are designated psychiatric wards or staff.

Ghana also has four private psychiatric hospitals: two in Kumasi, one in Accra, and one in Tema. Like the three public psychiatric hospitals, the four private hospitals are located in the south of Ghana. [34] The private facilities have an estimated total inpatient capacity of 100 patients, as per their bed capacity. [35] The high cost of care, estimated at about $150 per month per person[36] in such institutions is beyond the reach of most Ghanaians, 40 percent of whom live on less than $2 a day, [37] and 28.5 percent of whom live below the poverty line. [38]

Prayer Camps

Ghana has several hundred prayer camps, which are believed to have emerged in the 1920s, although little is known about their history, numbers, or operations since they are not state-regulated.[39] There are no clear figures on how many prayer camps actually exist in Ghana, and Human Rights Watch was informed by Rev. Opoku Onyinah, chairperson of the Ghana Pentecostal and Charismatic Council (GPCC), that Ghana Evangelism Committee (GEC) is conducting a survey.[40] Most are located in the south of the country: in Ada district alone, one of the ten districts making up the Greater Accra Region, there are an estimated 70 prayer camps.[41]

The camps offer prayer and healing services for persons with mental disabilities and are private Christian religious institutions that are usually managed by prophets, many of them self-professed religious leaders who claim to be able to cure persons having various conditions, including cancer, infertility ,and physical or mental disability, through prayer and other non-medical techniques. The prayer camps which Human Rights Watch visited were like any other Christian place of worship, conducting normal church activities including prayer and counseling, in addition to supporting charitable activities, such as homes for orphans and the elderly. The main difference between prayer camps and the Catholic or protestant churches, according to a Christian leader, is that “prayer camps are more of charismatic and pentecostal churches, and they specifically believe in the power of miracles, consultation with angels, and spiritual healing.”[42]

All of the prayer camps that Human Rights Watch visited said they were Christian institutions, although some, in addition to prayers, also administer traditional herbs. More established prayer camps such as Mount Horeb and Edumfa had special sections referred to as “sanatoria” where persons with mental disabilities were taken for healing.

The camps are mainly intended as retreats for prayer and spiritual healing, and some of them have units for persons with mental disabilities.[43] However, the primary role of prayer camps, according to those who spoke to Human Rights Watch, is not to treat persons with mental disabilities. While each of the eight camps Human Rights Watch visited has a unit for treating persons with mental disabilities, such treatment was the smallest component of the work being done at such camps. There was considerably greater emphasis on various forms of spiritual and temporal activities like worship and commercial agriculture.

According to leaders of camps who administer treatment and are referred to as prophets, persons with mental disabilities are often brought by their families, [44] and may reside in the camps for several days to several years. [45]

Some prayer camps that Human Rights Watch visited were located in open fields or forests; some operated out of structures that were half-built and offered only a rooftop for shelter. Others still were more established and better funded by church networks and looked like small villages. The more established camps included Mount Horeb and Edumfa Prayer camps, both of which occupied large areas of land and had large church halls and retreat facilities for anyone who wanted spiritual services, including prayers, counseling, and consultation on various issues. These camps had several pastors assigned to different ministerial responsibilities, including counseling. Edumfa Prayer Camp management engaged in activities like commercial agriculture and baking, the proceeds of which, according to Prophetess Rebekah Bedford, help fund the day-to-day running of the prayer camp.[46]

In the camps Human Rights Watch visited, we observed that most people brought for healing for mental disabilities, drug use, or epilepsy—unlike those who had come for healing related to illnesses such as cancer—were chained to logs, trees, or other fixed spots and underwent a regime of daily prayer and fasting. Most individuals treated in the prayer camps for mental disability stayed from a few days to more than a year.[47]

In one camp residents were formally registered and received a spiritual healing plan, a form describing an internal code of conduct for prayer camp visitors, responsibilities of visitors, prayer schedules, procedures for discharge from the camp, and regular administrative tasks.[48]

Some prayer camps, like Edumfa, are affiliated with Faith Complementary Health Care Association of Ghana, an association of camps that use natural elements and the bible in healing.[49] The association issued members a booklet with instructions on how to record information of those admitted to the camps, including name, age, occupation, marital status, religion, and nearest relative, as well as individual medical histories, including examination, diagnosis, and treatment.[50] Edumfa Prayer Camp also gave Human Rights Watch a copy of an Indemnity Form, to be signed by the person with mental disability, with entries like “derangement of mind proposed treatment.” Modes of treatment listed on the form include “prayers, fasting, confinement, and such appropriate restraints as circumstances demand.”

Inside a Typical Prayer CampThere are wide variations in the way prayer camps in Ghana operate. Some, like Mount Horeb and Edumfa, are well organized with predictable daily schedules for patients, while most do not follow particular schedules. The prayer camps vary widely in size, some are as big as a small village and include a church building, a special section for persons with mental disabilities, residences for the prophets, and rooms rented to guests and other visitors. Some of these visitors stay within the camp premises for days or weeks. Some camps have big church buildings, while in others, church buildings were under construction. A day at a prayer camp, according to Mount Horeb’s Pastor Christian Hukipoti (the pastor overseeing the section housing persons with mental disabilities) starts with morning devotion (5:00 to 6:00 a.m.) after which patients take their baths. Breakfast, for those who are not fasting, is between 8:00 and 9:00 a.m. This is followed by bible study, which takes place in the church building “for those who are calm,” while those who are not considered calm are kept back in their rooms. Bible study continues until 3:00 p.m., when those who are not fasting take lunch, which lasts until 4:00 p.m. Between 4:00 and 8:00 p.m. is free time, after which those who are calm and are not in chains go for evening prayers, which end at 10:00 p.m. Pastor Hukipoti told Human Rights Watch, Between 11 p.m. and 1 a.m. we do intercession for those who are in chains and can’t go to church, and during this time, the prophet visits the respective rooms, prays for them, and casts demons out of some of them. We also have a nurse who visits our patients from Tetteh Quashi hospital; she comes twice a week (Tuesday and Friday), and we call her during emergencies, for example, when someone reacts [adversely] to medication. At Edumfa and Mount Horeb the prophets would counsel people at different hours of the day, some of whom Human Rights Watch found waiting in tents for a chance to have a one-on-one session with the prophet or prophetess. In addition, the prophets manage and oversee the administration of the camps. The m ajority of people with mental disabilities admitted to prayer camps are often chained around the clock, for several weeks until discharged. Those in chains are unable to join prayers or other activities in the camp. A few of those that Human Rights Watch interviewed who at some point were chained, especially at Mount Horeb and Edumfa prayer camps, were relocated to special wards called the “calm rooms.” Compared to other rooms, “calm rooms” were less crowded and housed the fewest number of people. Such rooms had a few makeshift beds, but some occupants slept on small mattresses, and others slept on the bare floor. A few had been declared by the prophets as healed, but stayed at the camp to provide support to those who were still undergoing treatment. They helped with the cleaning and preparing food, and some were paid a token by the camp. At Mount Horeb Human Rights Watch was told by Pastor Christian Hukipoti that the prophet would go around all the wards at night praying for the people. On Sundays, those deemed healed by the prophet would be unchained, transferred to the calm room, and allowed to attend Sunday service. Family members of camp patients told Human Rights Watch that they made the decision to take their family members to prayer camps usually on the recommendation of people who had been to such camps and had been healed. Some took their relatives to the camps after they could not be cured at psychiatric hospitals and traditional shrines. For others, prayer camps were closer to their communities, which made it easier to bring a family member for admission. While Human Rights Watch could not ascertain whether people actually got healed at the camps, prophets strongly reported that it happened. Our endeavors to ask them for addresses of those who were healed and returned to communities were futile because they said they did not keep records of the people they treated. While some prophets claimed that those healed never came back to the camp after relapses, some people with mental disabilities that Human Rights Watch interviewed said they had been to such camps more than twice. At Mount Horeb, however, two officials working in the “sanatorium,” the section set aside for people with mental disabilities, said they came in as patients, and when they got healed, they chose to serve those who came in for treatment. However, a nurse who visits Mount Horeb Prayer Camp, said she has not seen someone completely healed in the two years she has been visiting the camps, but she said some get better for some time. |

Despite serving as an alternative residential facility for those with mental disabilities, prayer camps operate with little or no state regulation. Many nominally fall under the authority of the Ghana Pentecostal and Charismatic Council (GPCC), an umbrella body for 122 churches and evangelical associations in the country, having been either registered directly as council members or founded by individual members of churches affiliated with the council.[51] The council has an ad hoc committee of elders, which monitors compliance of member churches with the guidelines regulating prayer camps.[52] However, the council’s oversight of the camps is limited, and the camps’ operations are often inconsistent with council guidelines. Prayer camps whose affiliation with the Pentecostal Council has been terminated, or which operate outside its purview, are not subject to any regulation.

The Pentecostal Council has set up structures to govern prayer camps registered with it. These structures include ad hoc committees to monitor their operations and written guidelines for prayer camp operations.[53] According to Rev. Dr. Opoku Onyinah, chairperson of the Ghana Pentecostal and Charismatic Council (GPCC), the guidelines prohibit chaining or fasting of any “sick” person, or restricting which kinds of foods people at the camps could eat. They also require the camps to send persons with mental disabilities to hospitals, and to have vehicles to rush medical cases there if necessary.[54]

The council has sometimes taken disciplinary action based upon these guidelines. For example, in May 2011, the Pentecostal Council disassociated itself and cancelled the membership of Edumfa Prayer Camp—one of the oldest and most prominent prayer camps in Ghana—for failing to meet these standards.[55] Rev. Opoku Onyinah explained that while cancellation of membership does not mean closure of the camp, the public is warned from going to such a camp, until issues that led to cancellation of membership are rectified.[56]

Lack of staff is also a concern in prayer camps. None of the eight camps that Human Rights Watch visited employed a qualified medical or psychiatric practitioner. At Mount Horeb, Edumfa, and Nyakumasi Prayer Camps, where researchers found the largest numbers of persons with mental disabilities, the staff consisted mainly of pastors, prophets, and former patients whose conditions had improved.[57] At Edumfa Prayer Camp, it was largely family members, well-wishers, and a few pastors.

Table 1. Number of Persons with Mental Disabilities Housed at Prayer Camps Visited by Human Rights Watch, November 2011-January 2012

|

Name of Prayer Camp |

Number of people with Mental Disabilities at Time of Visit |

|

Mountains Jesus Divine Temple Mission (Nyakumasi Prayer Camp) |

30 |

|

Mount Horeb International Prayer Ministries (Mount Horeb Prayer Camp) |

135 |

|

Heavenly Ministries Spiritual Revival and Healing Center – Church of Pentecost, (Edumfa Prayer Camp) |

25 |

|

United Bethel Pentecostal Ministry International- Kordiabe |

3 |

|

Charity Prayer Ministry, Kwadoegye |

2 |

Traditional Healers

According to a report by the Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative Africa, an estimated 70-80 percent of Ghanaians utilize traditional medicine.[58] Many seek treatment from the estimated 45,000 traditional healers (people who practice based on theories, beliefs, and experiences indigenous to different cultures including ritual and herbal methods of treatment).[59]

The Community

According to responses from persons with mental disabilities living in the community and their family members who Human Rights Watch interviewed, there were no medical or physical support systems after patients were discharged from psychiatric institutions. [60]

The community support available to persons with mental disabilities was mainly rendered by civil society organizations, including BasicNeeds Ghana (currently working in five out of Ghana’s ten regions), Mindfreedom Ghana, and Mental Health Society of Ghana (primarily working in the southern parts of Ghana). These organizations help community members with mental disabilities, as well as epilepsy and drug-related psychosis, to access services, especially medication. These organizations mainly work with government-trained community psychiatric nurses or volunteers. [61]

II. Abuses

As soon as you get a mental disability, you nearly lose all your rights, even to give your opinion.

—Doris Appiah, national treasurer, Mental Health Society of Ghana, Accra, Greater Accra Region, November 2011

Human Rights Watch found that people with mental disabilities in Ghana suffered a number of human rights abuses, some of which are detailed in this section.

Involuntary Admission, Arbitrary Detention

I was arrested from my home by two men who came with police. They never gave me any reason, and they handcuffed me, took me to police where I spent three days.[62]

—Peace, a 55-year-old woman with schizophrenia, Pantang Psychiatric Hospital, November 2011

Individuals with mental disabilities in psychiatric hospitals and prayer camps in Ghana are routinely institutionalized against their will by family members or police, and denied the opportunity to refuse or appeal their confinement.[63]

It was not clear whether persons with mental disabilities under prolonged detention, both in hospitals and in prayer camps, had been before a judge to review or challenge their detention. Some of the leading local organizations working with persons with mental disabilities that Human Rights Watch interviewed were unaware of any such cases.[64] Dr. Akwasi Osei, chief director of the Ghana Health Service and director of Accra Psychiatric Hospital, told Human Rights that the old mental health law did not make any provision for people who are voluntarily admitted (with consent of relatives) to challenge such admission or any resulting treatment.[65] The new Mental Health Act, however, establishes a tribunal mandated to hear complaints of people with mental disabilities detained under the act, through which persons detained against their will in psychiatric hospitals can challenge such detention. While the new Mental Health Act will allow those detained in institutions to challenge admission and treatment, the law does not expressly cover persons with mental disabilities detained in other settings such as prayer camps.

Some of the individuals who are involuntarily admitted were perceived to be a danger to themselves, property, or others, which according to Dr. Akwasi Osei, chief psychiatrist at Accra Psychiatric Hospital, is determined based on “information given to the doctors of the patient’s conduct at home, his or her level of anxiety, rapport with the hospital staff, and the nature of psychopathology (causes and processes of mental disorder).”[66]

Some have problems of drug abuse and addiction. Others are outcasts in their communities or families, and are perceived as being “different” or “difficult.” According to Dr. Akwasi Osei, if an individual is brought to the hospital by police, psychiatrists determine whether or not to admit the person depending on their symptoms, behavior, and diagnosis, without seeking the patient’s consent, and without an independent judicial review.[67]

Peace, a 55-year-old woman with schizophrenia at Pantang Psychiatric Hospital, told Human Rights Watch, “Hospital is not a place where anyone would like to live … but I have no right to leave the ward.”[68]

Police, working with local government assemblies, also round up persons with actual or perceived mental disabilities when Ghana hosts important visitors.[69] One mental health expert said, “When President [Barack] Obama was coming to Ghana in 2008, police rounded up persons with mental disabilities because they did not want him to see mad men.”[70]

Aisha, an articulate woman in her mid-50s, was taken to Mount Horeb Prayer Camp by her adult children because she was not sleeping at night, and she lived there for two months before Human Rights Watch met her. “I don’t want to be here even for one week,” she said, adding that she would prefer treatment in a psychiatric hospital, but camp administrators would not let her go.[71]

John, who had been living in Mount Horeb Prayer camp for two months, told Human Rights Watch, “I want to go home, but they don’t discharge me, and they don’t give me any reason.”[72]

Richard, an 18-year-old man who was brought to Edumfa Prayer Camp by the police, said that his mother “told police to arrest me as I was sleeping. I was handcuffed at 5 a.m. and brought here. They locked my leg in a chain.”[73]

Under the 2012 Mental Health Act, voluntary patients (people who go to a mental health facility on their own with or without referral) in psychiatric hospitals have a right to seek release by filling out a Discharge against Medical Advice Form (DMAF), a process they should not need to undergo because they had voluntarily admitted themselves for treatment. However, patients who are forcibly “committed” (taken to a facility for treatment without consent, such as by a family member or the police, or without a court order following the commission of a crime) to the hospital do not have such a right under both the prior 1972 Mental Health Law and the new 2012 Mental Health Act.[74] While discharge of voluntary patients against medical advice is allowed in Accra Psychiatric Hospital, a nurse at Pantang Psychiatric Hospital told Human Rights Watch that a doctor’s assessment is required for even voluntary patients to be discharged.[75] There are no such formal discharge procedures in the prayer camps that Human Rights Watch visited; people are allowed to leave only when the prophet considered them ready to be discharged. However, relatives of persons with mental disabilities admitted to prayer camps could ask for their discharge at any time.

The Constitution of Ghana prohibits deprivation of liberty except in circumstances permitted by law.[76] Among these circumstances, a person can be deprived of liberty if he is of “unsound mind … or a vagrant, for the purpose of his care or treatment or the protection of the community.”[77] Furthermore, under the 2012 Mental Health Act, a police officer can arrest a person who leaves a psychiatric facility without being discharged.[78] In cases where the person is not an imminent danger to herself or others, or is not detained because of pending criminal charges, or is not brought before a court, this may result in arbitrary and prolonged detention of persons with mental disabilities, in contravention of the African Charter on Human and Peoples Rights (ACHPR) and the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD).

In the three public psychiatric hospitals, the majority of the staff said that involuntary admission, and subsequent continued detention, was not a violation of patients’ rights, and defended a paternalistic approach to psychiatric care that gives deference to health care providers to determine what is in the best interests of the patient.[79] Dr. Osei, head of Accra Psychiatric Hospital, told Human Rights Watch, “Involuntary admission is good because the state is exercising its mandate to protect someone, their family, the public, and property.”[80] This is not a violation of rights, he added. “Sometimes it’s wrong to defend rights without looking at the broader picture.”[81]

Prolonged Detention

I was tricked into coming here by my mother. I would never have accepted, but I have been here for more than one year.

—Raymond, 35-year-old man at Nyakumasi Prayer Camp, Central Region, January 2012

Some individuals, especially those taken to hospitals by police on court order, remained there even after discharge—often because they had been abandoned by families and could not return to their home communities.[82]

Bentil, a 26-year-old woman with schizophrenia, had been in Ankaful Psychiatric Hospital for four months and was cleared for discharge, but she was still there because she had nowhere to go.[83] “No one has come,” she said. “I want to go and stay at home.”[84] In Accra Psychiatric Hospital, Human Rights Watch saw a letter from a clan leader to hospital management requesting that his relative never be discharged, even when his condition improved.

Human Rights Watch learned that doctors in psychiatric hospitals met with patients in general wards every two weeks, in some cases resulting in long delays for discharge and prolonged detention.[85] Sarah, a woman who had voluntarily come to Pantang Psychiatric Hospital and was ready for discharge, said, “The nurses tell me a doctor will come and discharge me, but it is now two weeks and I have not seen any.”[86]

People also remained for long periods in prayer camps, where they told Human Rights Watch they wanted to leave and either go home or go to a psychiatric hospital, but they could not because their families refused or because the prayer camp leaders did not deem them fit to do so. John, for example, a person with a mental disability at Mount Horeb Prayer Camp, said that he was chained for one year without any treatment. He said: “I want to go home, but they don’t discharge me and they don’t give me any reason.”[87]

Most prayer camps that Human Rights Watch visited do not have formal criteria for determining that an individual is ready to leave. Instead, the prophet determines when people can leave, based on his assessment or “a message from God.”[88] According to one prophet, people are allowed to leave when they are “completely okay,” depending on “how someone speaks and what they do.”[89] Another religious leader told Human Rights Watch, “God shows a prophet a patient who has completely healed and he goes to the sanatorium to discharge such a person.”[90]

Conditions of Confinement

Overcrowding and Poor Hygiene

Overcrowding has long been a major problem in Ghana’s psychiatric hospitals and continues to be a problem at its largest hospital, Accra Psychiatric Hospital.[91] Intended to accommodate 600 patients,[92] it has, at times, housed up to 1200 patients, and had 900 patients in November 2011.[93] Lillian, a 41-year-old woman with schizophrenia, told Human Rights Watch, “Most of us don’t have beds. I sleep on a mat and I have no blanket.[94]

The ward for long-term patients at Pantang Psychiatric Hospital had 40 beds for 50 patients.[95] In the Special Ward at Accra Psychiatric Hospital, which houses people brought by police on court order, the situation was even worse. One nurse said, “We currently have 205 patients, and they have to share the 26 functional beds.”[96] As a result of overcrowding, patients sleep on thin mattresses, mats, or on the floor without a bed sheet.[97]

Overcrowding leads to a host of problems, such as supply shortages and health and sanitation hazards such as bed bug infestations and scabies.[98] In some wards in Accra and Pantang Psychiatric Hospitals, Human Rights Watch researchers saw toilets filled with feces and cockroaches.[99] From the gates of these wards, there was a powerful stench of urine and feces. “We experience shortages of basic items like gloves and detergents. Sometimes we don’t have water,” one nurse said.[100]

A nurse at Pantang Psychiatric Hospital told Human Rights Watch, “When we run out of protective gear such as gloves, we ask other patients to clean the ward.”[101] He added that this includes removing feces of other patients and using their bare hands to wash other residents, some of whom have open wounds.

Some prayer camps also had overcrowded living quarters, where most people interviewed did not have mattresses, blankets, or mosquito nets. At Mount Horeb and Edumfa Prayer Camps, small rooms that could reasonably accommodate only about eight people had over twenty.[102] People spent all day and night chained in small, hot rooms of about six by four meters, with little to no ventilation.

Personal hygiene was also a major problem in most of the prayer camps visited by Human Rights Watch. In Mount Horeb and Edumfa Prayer Camps, individuals urinated and defecated in buckets in each room. While prayer camp administrators said they empty the buckets three times a day,[103] residents said that the buckets were emptied once daily, usually early in the morning, leaving a pungent odor in the room for most of the day.[104]

Peter, a 21-year-old man chained to a wall in Mount Horeb Prayer Camp, said, “You can’t have a good bath with a chain. We shit here and they don’t come to clean up.”[105] He added, “It smells a lot inside here. I don’t know when I will leave this place.”[106]

Abigail, a staff member and former resident of Mount Horeb Prayer Camp, said, “People who are aggressive or violent don’t get buckets because they have a tendency to throw the feces at each other.”[107] She added that instead they defecate on the ground near where they are chained.[108]

In Nyakumasi Prayer Camp most persons with mental disabilities were chained to trees in the compound, and they had to urinate in the open and defecate into small plastic bags, which were later thrown into surrounding vegetation. Those who were chained in stalls at Edumfa and Mount Horeb Prayer Camps had to shower in the stalls where they slept and ate. Aisha, a 56-year-old woman at Mount Horeb Prayer Camp, told Human Rights Watch, “I bathe only two times a week, but I want to bathe every day.”[109]

Chaining

I have been chained in one sitting position. I have been here for two years.

—Isaac, a 28-year-old man with schizophrenia, Nyakumasi Prayer Camp, Central Region, January 2012

In the prayer camps visited by Human Rights Watch, many of the patients were chained inside fully built and semi-permanent structures or chained to a tree or concrete floor outside until the pastor or prophet declared them “healed.”[110] There was no movement beyond the length of the chains—usually about two meters. People had to bathe, defecate, urinate, change sanitary towels, eat, and sleep on the spot where they were chained.

Approximately 20 men in Edumfa Prayer Camp were chained and confined in rooms locked with padlocks, even during the day. Kofi, an 18-year-old man, said, “Why do they keep this fasting room locked with padlocks during the day? Even if they treat us like criminals, serving sentences for the worst crimes, we deserve to see some daylight.”[111]

About 120 of the 135 individuals at the Mount Horeb Prayer Camp were chained 24 hours a day (there were only approximately 10 who were not chained during Human Rights Watch’s visit in January 2012). Some told researchers they had been restrained in chains for several months.[112] Human Rights Watch researchers found an individual chained in exactly the same spot where he had been interviewed, three months later.

Elijah was chained to a tree in an open compound at Nyakumasi Prayer Camp for over five months. While describing his experiences, the 25-year-old man said, “This chain is more than a death sentence. At night it gets too cold, when it rains you can’t run to a shade, and we have lots of mosquitoes.”[113]

Aisha, a 56-year-old woman at Mount Horeb Prayer Camp, told Human Rights Watch, “When I defecate in the bucket, it makes everyone in this room uncomfortable. Why chain me when I can walk and go to the toilet?”[114]

Prayer camp personnel consistently told Human Rights Watch they used such restraints because most people in the camp were aggressive or would otherwise try to escape. Prophet Paul Kweku Nii Okia, founder and director of Mount Horeb Prayer Camp, acknowledged that it was illegal to chain an individual, but he attributed the practice to a lack of better means of restraining persons with mental disabilities. He told Human Rights Watch that “if a person comes and he is very wild, there is no way to cool them down, so we have to chain them, with approval of their families.” He added, “The constitution [of Ghana] does not allow us to chain, but we do it with the consent of families.”[115]

Rev. Rebekah Bedford of Edumfa Prayer Camp said the camp’s lawyer advised them to ask family members to sign forms consenting to the chaining of their relatives. “Human rights people don’t agree with people being locked in chains. Because some illnesses are chronic and go on for as many as 15 years without healing, their families give consent.”[116] It should, however, be noted that consent of a relative to chain someone does not render the chaining legal.

The Constitution of Ghana guarantees freedom of movement and only permits restrictions to one’s movement in instances of lawful detention.[117] While it permits a person to enjoy, profess, and practice religion, such enjoyment must be within the limits of the constitution, which prohibits all practices that dehumanize or injure the physical and mental well-being of another person.[118] In the same regard, the 1960 Criminal Code Act makes assault (which includes imprisonment) a crime.[119] A person is considered to have imprisoned another person if,

[I]ntentionally and without a person’s consent, he/she detains another person in a particular place of whatever extent or character, whether enclosed or not, with the use of force or physical obstruction from escape; or compels him or causes him to be moved/carried to another direction.[120]

Forced Seclusion

I am praying to God never to go into seclusion again. There is no toilet, so you have to be there with the shit and urine, yet you eat there as well; they clean [the room] after you have left.

—John (pseudonym), a 37-year-old man with schizophrenia, Pantang Psychiatric Hospital, November 2011

Seclusion is one of the many forms of solitary confinement, which is defined by the United States’ Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services as the involuntary confinement of a patient alone in a room or area from which the patient is physically prevented from leaving.[121] The UN special rapporteur on torture regards any prolonged isolation of an inmate from others (except guards) for at least 22 hours a day as amounting to torture.[122]

In all three public psychiatric hospitals, Human Rights Watch found that people were isolated for varying periods, ranging from 24 hours to three days; some were given sedatives.[123] A nurse at Pantang Psychiatric Hospital said, “We use prolonged seclusion when an individual continuously refuses to take medication, is aggressive, restless, or is a danger to themselves, others, or the environment.”[124] A nurse at Accra Psychiatric Hospital said, “The seclusion rooms are in poor condition, the walls are not padded, and the lighting and ventilation is poor.”[125]

Harriet, a 25-year-old woman who was seven months pregnant, spent six months at Accra Psychiatric Hospital. While there, she was put in a seclusion room for 12 hours. She told us, “The seclusion room … always dirty, very dark and you would not go in without being beaten by nurses.”[126]

Staff in all three public psychiatric hospitals said they had no choice but to put people in seclusion or to administer sedatives to patients who are aggressive and thus a danger to themselves, nurses, and other patients.[127]

The former UN special rapporteur on torture clearly stated that seclusion or solitary confinement in psychiatric hospitals as a form of control or medical treatment “cannot be justified for therapeutic reasons, or as a form of punishment.”[128]

While the 2012 Mental Health Act limits the use of restraints on persons with mental disabilities, it does not abolish restraints completely. An act by one person to restrain another person is generally criminalized, and in such extreme instances where restraint is permitted, specific compliance criteria should be defined, including who has the authority to restrain another person. All acts of restraint that do not meet these criteria, for example assault or unlawful detention, clearly amount to a crime.

Lack of Shelter

In some wards in the three psychiatric hospitals visited by Human Rights Watch, especially Accra Psychiatric Hospital, shelter was inadequate.

At the Accra Psychiatric Hospital, several buildings lacked windows, doors, or shade during the day. Many had old and leaking roofing. Individuals were either crowded in the few spots where there was shade, or baked in the sun. No fewer than 50 individuals in the Special Ward slept outside.[129] A nurse explained, “Patients move in and out of these structures at any time, just as other potential threats like mosquitoes and reptiles move in.”[130]

Some of the rooms in the eight prayer camps that Human Rights Watch visited were only half-built; others had holes in the walls and roofs that would allow in rain, mosquitoes, and cold air at night. A few patients or their families had fashioned bamboo beds and grass-thatched shelters under a tree to get protection from the sun, but many slept on cold, hard concrete floors with no mattress or bedding.[131]

Denial of Food

I’m really, really hungry and they won’t feed me. I don’t understand…. Why can I not eat? They give me porridge at night, but that’s not enough food.[132]

—Afia, 32, Mount Horeb Prayer Camp, January 2012

Administrators and pastors of seven of the eight prayer camps that Human Rights Watch visited said they believed fasting was key to curing mental disability.[133] Doing so, they said, would starve evil spirits and cleanse them.[134] “Fasting helps weaken the demons, making it easier for the spirit of God to enter and do the healing,” one pastor said.[135]

Doris Appiah, national treasurer of the Ghana Mental Health Society and former resident of a prayer camp in Kumasi, told Human Rights Watch that some pastors use fasting as a means to force patients to confess past sinful acts, which are presumed to be responsible for their mental disabilities.[136]She explained that some pastors would beat them to confess that it was their sinful acts that led to their mental disabilities , and those who refused to confess would be forced to fast for up to four days.

When the camp did provide food, people with mental disabilities told Human Rights Watch that it was too meager—at times, just one meal a day.[137] Some pastors reported sharing the little food available on a day among all the patients, especially because some families did not provide food for their relatives, and camps did not have enough money to buy enough food for everyone.[138] Asked why the food was not enough, Prophet Winfred said, “Some people are brought here by police, with no relatives and yet they need to eat; some families are very poor and they can’t feed some people they bring for healing; therefore, we share the little food we have on a given day.[139] The expectation was that families would regularly bring food for relatives at the camps; pastors said this seldom happens. Many interviewees appeared undernourished and complained of hunger.

Prayer camps had different ways of funding their work. Edumfa Prayer Camp, for example, charged a registration fee of 5 Ghana Cedis (US$2.50) to everyone who visited the camp; some had residential facilities which they rented out, and others operated small businesses such as bakeries and shops selling herbal products.

Fasting schedules varied in each camp, depending on why a person was brought into a prayer camp and the prophet’s healing plan.[140] For example, Human Rights Watch found that some individuals in Mount Horeb, Edumfa, and Nyakumasi Prayer Camps were compelled to fast for 36 hours over 3 consecutive days in 12-hour stints from morning until dusk. Others, mainly the elderly, fasted from 6 a.m. until noon.[141] Such fasting regimes lasted from 7 to 40 days.[142]

People in the prayer camps had no choice but to fast as it was considered a mandatory component of the healing process. “I have never fasted in my life because I don’t see any value in it,” said Elijah, who lived in Nyakumasi Prayer Camp, “but here, it is a must.”[143]

Fasting had consequences for people with mental disabilities besides hunger, including being unable to take prescribed medication.[144] One person with bipolar disorder described his experience at the Victory Bible Church Camp: “I had to fast from morning to evening for two years. I wasn’t allowed to take my medication for the entire time.”[145]

In the one prayer camp where fasting was not allowed, the prophetess said, “I don’t let the mad people fast because when I give them medicine, they have to eat well.”[146] As part of her treatment regime, she distributed local herbs and homemade concoctions.

In psychiatric hospitals nurses said that people (especially those on medication) needed some food between 5 p.m. and 9 a.m. (between dinner and breakfast), which hospitals do not provide, and patients are supposed to buy from canteens. One nurse told Human Rights Watch, “Those brought by police usually come with no money and yet they need to eat something between meals; they become so aggressive when they are hungry, and we have nothing to do about it.[147]

Ghana is a state party to a number of international and regional treaties, including the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), which require Ghana to respect and protect the right to food.[148] The Constitution of Ghana does not expressly recognize the right to food, neither does it provide for the right to health. It does, however, make provisions for the rights to life and adequate livelihood, which imply the right to food.[149]

Denial of Adequate Health Care

Access to health care for both physical and mental health problems was a major challenge for persons with mental disabilities in psychiatric hospitals, prayer camps, and the community.

Drug shortages bedevil all three public psychiatric hospitals in Ghana, mainly because of limited government supply, including medications for conditions such as malaria and skin infections.[150] Some patients in psychiatric hospitals needed alternative means of treatment that were either unavailable, or nurses did not have the proper skills to administer them.[151] Lillian said, “I get Largactil [a psychotropic drug], which I don’t like; doctors tell me I can’t get any other type [of medication], yet I get side effects like loss of sleep when I take it.”[152]

Persons with mental disabilities living within the community after having been discharged from mental health facilities also reported shortages of medications, generally provided to them by local NGOs. Suleiman Ayiku, an elderly man with bipolar disorder living in Greater Accra Region, told Human Rights Watch,

I get my drugs from BasicNeeds [a local mental health organization], but these run short, so I end up taking medications every three or four days as opposed to every day because I can’t afford buying the remainder [from a private pharmacy] to run me on a daily basis.[153]