Maps

Bangui

Glossary of Acronyms

A2R Alliance for the Rebirth and Rebuilding (Alliance pour la Renaissance et la Refondation)

APRD The Popular Army for the Restoration of the Republic and Democracy (Armée populaire pour la restauration de la république et la démocratie)

BINUCA United Nations Integrated Peacebuilding Office in the Central African Republic (Bureau intégré des Nations Unies pour la consolidation de la paix en République centrafricaine)

CEEAC/ ECCAS Economic Community of Central African States (Communauté économique des États de l'Afrique centrale )

CEMAC Central African Economic and Monetary Community (Communauté économique et monétaire de l'Afrique centrale )

CPJP Convention of Patriots for Justice and Peace (Convention des Patriotes pour la Justice et la Paix)

CPSK Patriotic Convention for the Salvation of Kodro (Convention Patriotique du salut du Kodro)

FACA Central African Armed Forces (Forces Armées Centrafricaines)

FDPC The Central African People’s Democratic Front (Front démocratique du peuple centrafricain)

FOMAC Multinational Forces for Central Africa ( Force multinationale de l'Afrique centrale )

GP Presidential Guard (Garde présidentielle)

ICC International Criminal Court (Cour pénale internationale)

ICG International Contact Group (Groupe international de contact)

IPD Inclusive Political Dialogue (Dialogue Politique Inclusif )

MICOPAX Mission for the Consolidation of Peace in Central African Republic (Mission de consolidation de la paix en République centrafricaine)

MISCA /AFISM-CAR African – led International Support Mission in the Central African Republic (Mission internationale de soutien à la Centrafrique sous conduite africaine)

MLC Movement for the Liberation of Congo ( Mouvement pour la Libération du Congo )

OHCHR Office for the High Commissioner for Human Rights (Bureau du Haut-Commissaire aux droits de l'homme)

OCRB Central Office for the Repression of Banditry (Office Central de Répression du Banditisme)

SRI Investigation and Intelligence Service (Section de Recherches et d’Investigations)

UFDR Union of Democratic Forces for Unity (Union des Forces Démocratiques pour le Rassemblement)

UFR Union of Republican Forces (Union des Forces Républicaines)

Summary

On December 10, 2012, an alliance of three major rebel groups known as the Seleka coalition began a campaign to overthrow the government of President François Bozizé of the Central African Republic (CAR). On March 24, 2013, Seleka rebels took control of Bangui, CAR’s capital, and also seized control of 15 of the country’s 16 provinces. Michel Djotodia, one of the rebel groups’ leaders, suspended the constitution, and installed himself as interim president—a role to which he was subsequently elected by a transitional government. Elections are to be held after 18 months.

The Seleka (“alliance” in Sango, the main national language) said they aimed to liberate the country and bring peace and security to the people. But for most Central Africans, 2013 has been a dark year, marked by rising violence and vicious Seleka attacks against civilians in Bangui and the provinces. With no checks on their power, the Seleka rule arbitrarily and with complete impunity, with the government failing to follow through on its public commitment to bring to justice those responsible for recent abuses.

Seleka forces have destroyed numerous rural villages, looted country-wide, and raped women and girls. In one attack in Bangui on March 25, Seleka fighters raped two sisters, aged 33 and 23, in their home. The younger sister, who was eight-months pregnant, lost her baby the next day. Rape survivors lack access to adequate health care due to insecurity and lack of health services. Civilians who have been abused have nowhere to turn: the civilian administrative state in CAR has collapsed. In most provinces there are no police or courts. Many health clinics across the country do not function, and in at least one town a hospital has been occupied by the Seleka; most schools are closed.

Interim President Djotodia has denied that Seleka fighters have committed abuses, and continues to shift blame for the violence between Bozizé loyalists, “false Seleka,” and bandits—even though at least one Seleka official in the field admitted responsibility for some attacks to Human Rights Watch. “That was us, the Seleka,” the executive secretary of the highest-ranking Seleka commander in Bouca told Human Rights Watch after two villages were burned.

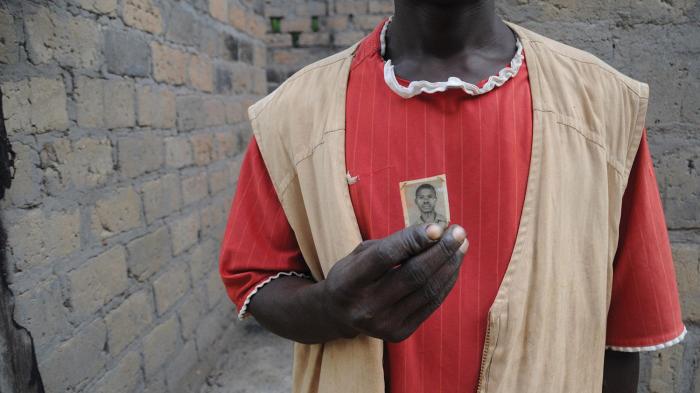

Human Rights Watch conducted extensive field research in the Central African Republic from April to June 2013 to document individual cases and identify patterns of violence committed by the Seleka. The research focused primarily on attacks against civilians and the destruction of civilian property. Human Rights Watch confirmed the deliberate killing of scores of civilians—including women, children, and the elderly—between March and June 2013, and received reports of hundreds more from credible sources. Human Rights Watch also confirmed the deliberate destruction of more than 1,000 homes.

The recent fighting has further exacerbated an already grim humanitarian crisis in CAR, a desperately poor landlocked country with high rates of mortality, disease, and food insecurity. In the areas Human Rights Watch visited, thousands of villagers were living in life-threatening conditions. The Seleka stole or destroyed food and seed stocks, and there are now massive food shortages. Residents—including children—are living in the bush near their fields and homes, in tents made from trees and leaves. Most have no access to clean water. In this dire situation, the people of CAR have been left to fend for themselves.

Humanitarian organizations are themselves vulnerable to Seleka attacks, impeding outreach to affected populations. Civilians looked to the Mission for the Consolidation of Peace in Central African Republic (MICOPAX), a regional peacekeeping mission led by the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS), and in particular its military force, the Multinational Forces for Central Africa (FOMAC), for desperately needed protection. On July 19, 2013, the Peace and Security Council at the African Union (AU) adopted a decision to transition MICOPAX into the International Support Mission in the Central African Republic (AFISM-CAR) and to initially support the political transition for six months.

The Bozizé government, and particularly the Presidential Guard, have also been accused of committing serious human rights abuses, especially in northern CAR. Human Rights Watch interviewed former prisoners jailed under Bozizé’s rule who were recently released from an illegal detention facility at the Bossembélé military training center. Prisoners there were held incommunicado for months and even years at a time; were denied food, water, and other basic services; and were tortured, they told Human Rights Watch. The prisoners said that Bozizé was present during torture sessions at the center, where he had a villa flanked by two concrete standing cells in which individuals were left until they died.

In 2013, however, the overwhelming majority of attacks against civilians were committed in Seleka-held territory—including by very young fighters, possibly child soldiers around 13 years old.

Abuses Committed by the Seleka in the Provinces

As the Seleka moved down to Bangui from the northeast, they captured major towns along the way. In these towns, the Seleka immediately began to loot the homes of the civilian population; those who tried to resist were threatened, injured, or killed.

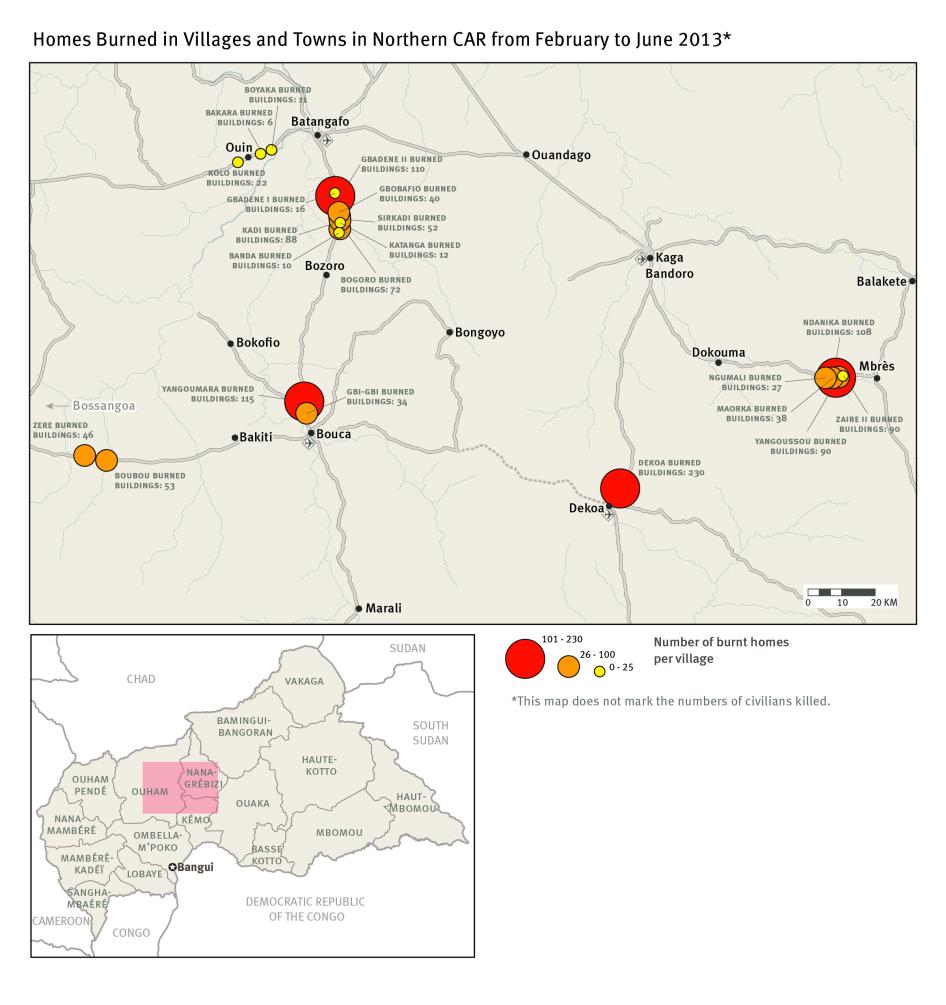

Human Rights Watch documented attacks on villages by Seleka forces and their allies in northern CAR between February and June 2013. This research focused on a broad triangle of territory within the main roads linking Kaga Bandoro, Batangafo, and Bossangoa.

Evidence indicates that Seleka fighters forced villagers out of their homes in order to loot them. Some villagers reported that the attacks were designed to create space for members of the Mbarara community—nomadic pastoralists who move their cattle between Chad and the Central African Republic and have recently been allied with the Seleka.

Human Rights Watch recorded more than 1,000 homes destroyed in at least 34 villages along these roads. Schools and churches were also looted and burned. The Seleka killed scores of civilians while they were trying to flee and have prompted whole communities to flee into the bush—including 113 families from Maorka. “Now I sleep in the fields,” one Maorka resident said. “I made a small hut out of leaves for my wife and our three children. I cannot come back because we do not have beds or our food stock and there is no security. [The Seleka] took all of our farming tools, they took our hoes. We have to use our hands.”

In one attack, Seleka forces, in collaboration with a self-appointed mayor, Adoum Takaji, executed five men and killed five more people as they attempted to escape the village of Ouin. Eyewitnesses described how Takaji went door to door in the village, reassuring fearful residents it was safe to come out to talk to the Seleka. “The first few left their homes, five of them, and were grouped under a tree,” one eyewitness said. “Their arms were attached to each other. They were then shot down one by one. Takaji was only 50 meters away.” Several witnesses told Human Rights Watch that one individual did not die straight away and the Seleka cut his throat. Later, when some residents returned to the village to bury their dead, the Seleka fired on them again, forcing them to flee once more into the bush. “I can still smell the dead,” one said.

In another attack, on May 19, Seleka forces killed 12 villagers trying to flee from three villages on the Bossangoa-Boguila road. According to residents, members of the Mbarara community also attacked villages outside Batangafo around this time.

Villagers who chose not to leave their homes live in perpetual fear of the prospect of renewed Seleka attacks. These traumatized residents told Human Rights Watch that when they hear a vehicle approaching they run.

Abuses Committed by the Seleka in Bangui

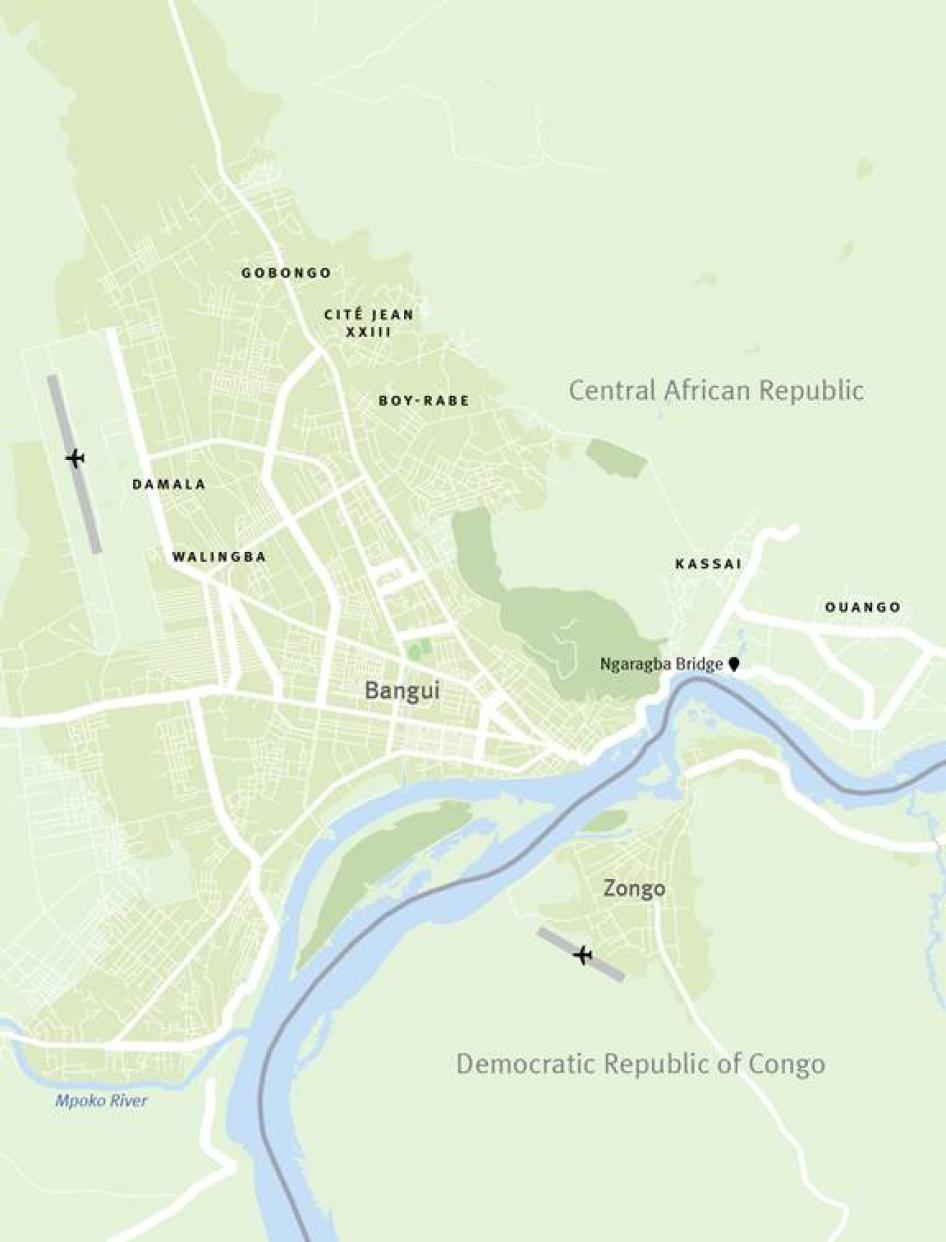

As soon as the Seleka took Bangui on March 24, they started to attack civilians and pillage the city. Human Rights Watch gathered credible testimony that the Seleka killed civilians the day the rebels entered the capital. Virtually every neighborhood was attacked:

- On March 27, Seleka forces killed 17 unarmed people in the Damala neighborhood.

- On April 12, a rocket attack injured 15 people, including 13 children, in the Walingba neighborhood. Two of the children required amputations.

- On April 13, Seleka forces killed 18 unarmed people around the Ngaragba Bridge near the Ouango and Kassai neighborhoods, forcing some residents to flee across the Ubangui River to neighboring Democratic Republic of Congo. Witnesses described seeing Seleka forces kill a priest on the bridge as he appealed for calm holding a Bible aloft. “Three Seleka fighters stepped out of the pick-up, walked toward him and shot him dead,” one witness said.Another witness recounted how a Seleka fighter shot a woman carrying a baby on her back and left her for dead in the street, with her crying infant still strapped to her.

- Between April 13 and 14, Seleka forces attacked the neighborhood of Boy-Rabe and killed approximately 28 unarmed people including three killed in a Seleka rocket attack on a church in Boy-Rabe; 13 people, including children, were seriously injured.

- On April 15, Seleka killed the 26-year-old wife and 18-month-old daughter of a truck driver, whose vehicle they wanted in order to transport stolen goods. A witness described how Seleka shot the baby in the head, before killing her mother as she approached the door to the family house. An eyewitness heard one Seleka say simply to another, “The baby’s head exploded and the wife was shot dead.”

- On June 29, Seleka forces attacked the Gobongo neighborhood and killed at least six unarmed people.

Once they took Bangui, the Seleka began targeting members of the national army, the Central African Armed Forces (Forces Armées Centrafricaines, FACA). Human Rights Watch has recorded numerous cases of extrajudicial killings of members of the FACA by the Seleka. In the worst incident on April 18, residents found the bodies of eight members of the FACA 15 kilometers outside Bangui on the Sceaux Bridge. Family members of some of the victims had to go and retrieve the bodies of their loved ones from the bridge.

The Seleka also summarily executed men it believed were FACA members. On April 15, the Seleka executed five men at the Mpoko River outside Bangui. Human Rights Watch received other credible reports of the killing of suspected FACA at the river.

The Need for Accountability

The lack of accountability for serious human rights abuses committed since independence in the Central African Republic has contributed to renewed cycles of violence and the breakdown of normative behavior, further fueling abuses. As one lawyer and local human rights defender said, “Now a waiter is killed after giving a beer, a taxi driver is killed after transporting a person.… This is the negation of the existence of humanity.”

Part of the problem of poor accountability relates to the loose command structure within the Seleka and the difficulty that high-ranking generals have maintaining control over their troops. Fighters often only answer to their direct commander, and different factions do not necessarily recognize one another. In April 2013, Human Rights Watch recorded multiple incidents of Seleka fighters killing other Seleka fighters to control territory in Bangui. Human Rights Watch also found inadequate efforts by Seleka leaders to ensure their subordinates do not commit serious abuses or are punished for crimes committed.

The transitional government appears unable to reign in Seleka forces or to restore order in the country. However, the larger problem stems from the government’s unwillingness to recognize that Seleka are committing abuses and/or bring to justice those responsible.

On May 20, President Djotodia set up a National Commission of Inquiry, composed of judges, human rights defenders, and police officers, to investigate serious crimes committed in the country since 2002. The commission has the authority to look into crimes committed both in the Bozizé era and since the Seleka took power. However, as of the end of June, the commission had not yet received funds or logistical support from the transitional government that would allow it to start its work.

The minister of justice has publicly committed to investigate and prosecute those responsible for past and current abuses. However, few steps have been taken and any efforts lacked impartiality. Isolated arrests of so-called false Seleka have occurred in connection with recent looting in the capital, but the state prosecutor has failed to carry out investigations or to arrest Seleka. The state prosecutor has also failed to investigate

more serious crimes, including extrajudicial killings, rape, pillage, and torture. The only other cases being investigated appear to target members of the former government, including former President Bozizé and other former ministers.

The Seleka was formed partly due to frustration over the Bozizé government’s refusal to investigate crimes committed in the northeast by both rebel groups and government forces since mid-2005. Yet, the Seleka are now committing similar abuses with near total impunity in Bangui and the provinces. Human Rights Watch welcomes the establishment of a commission of inquiry and the government’s stated commitment to tackle impunity. But we are concerned about the lack of political will to ensure fair and impartial justice for all persons responsible for abuses. National judicial authorities must make legitimate efforts to hold violators of human rights responsible, including Seleka members, in order to ensure equitable justice.

Recommendations

To the Transitional Government of the Central African Republic

- Issue a public declaration that the government will not tolerate attacks on civilians and will hold accountable anyone found responsible for murder, rape, pillage, and other serious violations of international humanitarian and human rights law.

- Investigate and prosecute, in accordance with international fair trial standards, all persons against whom there is evidence of criminal responsibility for grave crimes, including those liable under command responsibility, for their failure to prevent or prosecute these crimes .

- Investigate attacks on schools, medical centers, and humanitarian actors, and prosecute or take disciplinary measures against any member of the Seleka found responsible.

- Restore law and order in the 15 provinces under its control by urgently deploying provincial military commanders under the leadership of the Ministry of Public Security and the Ministry of Defence and deploying the provincial governors (Préfets) under the leadership of the Ministry of Territorial Administration.

- After a vetting process to exclude individuals who have committed human rights abuses, reinstate security institutions in the country, including the police, the gendarmerie, and the regular army. Ensure that members of the police, gendarmerie, and military are trained on human rights and international humanitarian law before deployment.

- Ensure that Seleka fighters found responsible for serious human rights abuses are not reintegrated into (or allowed to join) the national army and are not given other official positions within the government.

- Ensure all police, gendarmes, and soldiers receive a regular and adequate salary, and enforce a zero tolerance policy on looting.

- Ensure all soldiers are lodged in military barracks in order to ensure they do not occupy schools or hospitals.

- Provide the National Commission of Inquiry with the necessary resources to promptly, thoroughly, and independently investigate allegations of human rights abuses by all parties, including by Seleka rebels.

- Provide access to health and other services for victims of human rights violations, paying special attention to the needs of women and girls who have survived sexual violence.

- Expedite the rebuilding, repair, and re-opening of schools.

- Seek financial and technical assistance from international donors, and give guarantees that all steps will be taken to ensure fair and credible domestic investigations and prosecutions of grave crimes.

- Seek financial and technical assistance from international donors to support the National Commission of Inquiry and give guarantees that all steps will be taken to ensure the inquiry will be objective, transparent, and efficient.

- Continue to provide full cooperation and unhindered access to the International Criminal Court and other human rights investigators.

To Seleka Forces

- Cease immediately all attacks on civilians. Put in place measures to deter, prevent, and punish individuals who commit human rights abuses and cooperate with all national investigations and prosecutions of Seleka members, including the National Commission of Inquiry.

- Cease immediately all attacks on humanitarian actors and make public assurances that they will have safe passage to carry out their work.

- Cease all recruitment and use of children as soldiers. Groups that have already concluded action plans with the United Nations (the Convention of Patriots for Justice and Peace [CPJP] and the Union of Democratic Forces for Unity [UFDR]) should fulfil all obligations under these agreements. All other groups that have been listed by the United Nations Secretary-General’s annual report on children and armed conflict (the CPJP, the Patriotic Convention for the Salvation of Kodro [CPSK], and the Union of Republican Forces [UFR]) should develop plans to address grave violations against children.

- Cease immediately all attacks on schools and medical centers. If occupied, vacate these premises immediately. Prohibit the use of such facilities in any manner in violation of international humanitarian law, or which impede the right to education.

- Put in place measures to prevent harassment or intimidation by Seleka members of any potential witnesses in future investigations or a national commission of inquiry.

To the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS)

- Urgently bolster peacekeeping efforts in the Central African Republic by implementing the African Union Peace and Security Council’s July 19, 2013, decision to protect civilians, restore security and public order, and create the necessary security conditions for the provision of humanitarian assistance.

- Deploy additional, trained, and well-equipped troops throughout the country to ensure civilian protection.

To the African Union Peace and Security Council and AFISM-CAR

- Ensure that the African-led International Support Mission in the Central African Republic (AFISM-CAR) has the logistical and financial support to fulfil its mandate on civilian protection.

- Consider troop deployment from other member states and expanding the nucleus of the contingent to countries that were not originally a part of MICOPAX.

- Exclude any troops from AFISM-CAR whose presence might compromise the perceived neutrality of the AU force.

To the United Nations Security Council

- Impose targeted sanctions against individuals, including Seleka leaders, responsible for serious human rights abuses since December 2012, as recommended by UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon.

- As requested by the AU, give full support to the AU and ECCAS to facilitate the implementation of AFISM-CAR’s mandate to protect civilians, including through the provision of the necessary financial, logistical, and technical support.

- Expand the mandate of the United Nations Integrated Peacebuilding Office in the Central African Republic (BINUCA) to allow the mission to monitor, investigate and report publicly and to the Council on any abuses or violations of human rights or international humanitarian law committed throughout the country.

- Ask the UN secretary general to deploy a group of experts in the protection of civilians to the Central African Republic to inquire into, and rapidly report on, civilian protection needs and challenges. The group should recommend concrete measures to advance the protection of civilians, ensure unhindered humanitarian access and assistance, and end impunity for serious crimes and violations of international law.

- Task the BINUCA with monitoring closely the Central African Republic government’s pursuit of justice to ensure that national efforts to investigate and prosecute those responsible for abuses are carried out in accordance with international fair trial standards.

- Request to be briefed by the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on the fact-finding mission to the Central African Republic conducted in June and July and covering human rights violations committed in Bangui and other localities since December 2012.

To the United Nations Integrated Peacebuilding Office in the Central African Republic (BINUCA)

- Ensure the office’s Human Rights and Justice Unit has the necessary resources and staff to effectively monitor, investigate, and report on past and on-going human rights abuses in the Central African Republic.

- Provide assistance to the National Commission of Inquiry and urge the transitional government to investigate and prosecute all persons against whom there is evidence of criminal responsibility for grave crimes.

- Assist the government to re-establish the rule of law with a focus on the independence and impartiality of the justice system, the humane treatment of detainees, and the protection of the accused and witnesses.

To the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR)

- Publish an interim report on the human rights situation including the findings of the OHCHR fact-finding mission to CAR in June-July, as well as continue to report publicly on any deterioration of the situation.

To the Human Rights Council

- Remain seized of the human rights situation in the Central African Republic and consider a special session in case the situation deteriorates.

- Consider the report of the OHCHR fact-finding mission in CAR and consider establishing the mandate of an Independent Expert to provide technical assistance to the transitional government, monitor and report on the situation of human rights, and report to the Council on human rights developments and challenges.

- Encourage the Human Rights Council Special Procedures to respond to the standing invitation issued by the CAR minister of justice in June 2013 to visit CAR.

To the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court (ICC)

- Continue to actively monitor developments in the Central African Republic to determine whether crimes within the ICC’s jurisdiction are being committed.

- Remind all parties of the ICC’s jurisdiction and, as appropriate, issue public statements assessing the situation.

- Press national authorities to investigate and prosecute all persons against whom there is evidence of criminal responsibility for grave crimes, including those liable under command responsibility, in accordance with international fair trial standards.

- Monitor any domestic efforts to prosecute these crimes to ensure that the trials are fair, credible, and meet international standards.

- Discuss with national authorities international assistance that may be available to assist accountability efforts and identify areas where ICC officials may have practical expertise to share, such as conducting investigations of complex crimes and ensuring witness protection.

To the Governments of France, the European Union, the United States, and Other International Donor s

- As requested by the AU, give full support to the AU and ECCAS to facilitate the implementation of AFISM-CAR’s mandate to protect civilians, including through the provision of the necessary financial, logistical, and technical support.

- Incorporate training on human rights protection in any security sector reform programs and create vetting mechanisms to ensure that Seleka fighters who have committed human rights abuses are not reintegrated into the national army or given other official positions within the government.

- Support programs that protect, demobilize, and rehabilitate child soldiers.

- Assist national authorities in their efforts to restore the rule of law and to conduct trials for grave crimes in accordance with international fair trial standards, including by conducting an assessment of the domestic judicial system with the view toward identifying possible areas of assistance.

- Ensure adequate humanitarian funding to restore education.

To the Government of Chad

- Investigate and publish findings into allegations of Chadian involvement with and/or support to the Seleka. If evidence of Chadian involvement is discovered, ensure this activity ceases immediately.

Methodology

This report’s primary focus is on abuses carried out before and after the Seleka took control of the CAR capital Bangui on March 24, 2013. Most of the abuses documented occurred in Seleka-controlled territory.

The cases presented in this report represent just a small number of the human rights abuses that have taken place, including the killing of civilians and destruction of property.

This report focuses on the capital Bangui and the provinces of Kémo Gribingui, Nana Grébizi, and Ouham. It does not document equally serious reports of human rights abuses reported in the provinces of Ombella-Mpoko, Ouham Pendé, Nana-Mambéré, Mambere-Kadei, Sangha Mbaere, Lobaye, Ouaka, Basse Kotto, and Mbomou. Human Rights Watch has gathered evidence on abuses in some of these provinces, but prioritized research on accessible provinces given the current security situation.

To date, no organization, including BINUCA, has advanced total figures of the numbers of civilians killed by the Seleka. On the basis of its own research, Human Rights Watch estimates that at least scores of people have been killed in Seleka-controlled territory. It has been difficult to advance a more precise figure as no comprehensive or reliable record has been made of these incidents, and Human Rights Watch was able to document only a small proportion of reported killings and attacks on villages. Many people who have been victims of or witnesses to Seleka abuse remain in hiding, fearful of talking to outsiders, given the possibility of retribution by the Seleka. Furthermore, the security situation in both Bangui and the provinces has further limited the ability of Human Rights Watch to investigate all credible reports.

The majority of killings and attacks on villages documented by Human Rights Watch were carried out by the Seleka. Some killings and attacks were carried out by members of the Mbarara community; however these attacks were undertaken with Seleka support. Human Rights Watch’s research focused on cases where the Seleka targeted civilians or those who were unarmed. Cases that appeared to be common crimes or where there were no clear indications of Seleka involvement are not included in this report.

Principal research for this report was carried out in April, May, and June 2013. A Human Rights Watch researcher and a consultant conducted interviews in the capital Bangui and the provinces of Ombella-Mpoko, Kémo Gribingui, Nana Grébizi, Ouham, and Mbomou. Human Rights Watch interviewed multiple sources for each case in order to confirm and validate the reliability of testimony.

Human Rights Watch interviewed numerous victims and eyewitnesses of targeted killings of civilians and attacks on villages. Human Rights Watch also spoke with relatives and friends of victims, journalists, members of civil society organizations and international nongovernmental organizations, former members of the Bozizé government, former parliamentarians, national and local Seleka officials, members of the transitional government, judicial personnel, foreign diplomats, and United Nations officials.

Additionally, Human Rights Watch representatives met with senior government officials including Interim President Michel Djotodia, Public Security Minister Noureddine Adam, (Former) Water and Forests Minister Mohamed Moussa Dhaffane, Justice Minister Arsène Sende, and the National Prosecutor Alain Tolmo. Government officials’ responses to cases and concerns raised by Human Rights Watch are referenced in this report.

Because of the fear of reprisals, the names of witnesses, family members and friends of victims who spoke to Human Rights Watch have been withheld from this report. Interviews were conducted in French or Sango with the assistance of interpreters.

Background

The Seleka

The Seleka was created in late 2012. Its main factions are the Convention of Patriots for Justice and Peace (CPJP), the Patriotic Convention for the Salvation of Kodro (CPSK), the Union of Democratic Forces for Unity (UFDR) and to a lesser extent the Union of Republican Forces (UFR) and the Alliance for the Rebirth and Rebuilding (A2R).

Initially, the Seleka called for the implementation of the recommendations of the Inclusive Political Dialogue (IPD)—held in 2008 to create conditions for peaceful elections in 2010. At that time, the Seleka was looking for: financial compensation for the rebels; the release of political prisoners; and the opening of investigations into past crimes including the disappearance of former CPJP leader Charles Massi.

The Libreville Agreement forged between the Seleka and the Bozizé government in January 2013 aimed to provide a road map for a political transition and ceasefire. In February 2013, Michel Djotodia was named deputy prime minister and defense minister. The following month, both sides resumed fighting, and the Seleka took Bangui in late March.

Union of Democratic Forces for Unity (Union des Forces Démocratiques pour le Rassemblement, UFDR)

The UFDR is a rebel group created to address marginalization of the Gula ethnic group in northeastern CAR. In 2006 the UFDR started taking control of strategic diamond-producing towns in northeastern CAR and advancing on Bangui. At the time, Damane Zakaria was the UFDR’s commander on the ground, while Michel Djotodia was active as one of the group’s leaders. So serious was the UFDR offensive that French troops had to step in to assist the Bozizé government in December 2006. The UFDR signed a peace agreement in May 2007 with the CAR government and the Libreville Comprehensive Peace Agreement in June 2008, after which it continued to maintain influence over the diamond trade in the Haute-Kotto province. Its ranks include men who helped overthrow former president Ange-Félix Patassé in 2003 and who felt they were never adequately compensated by President Bozizé.

Convention of Patriots for Justice and Peace (Convention des Patriotes pour la Justice et la Paix, CPJP)

The CPJP is a rebel group created in 2008 based near Ndélé. It was created to protect ethnic Runga from UFDR attacks of non-Gula tribes. The CPJP soon sought control of diamond mines in the northeast. By 2010 it controlled mining territory around Bria in Haute-Kotto province. In late 2010 it attacked Birao with the help of Chadian rebels and briefly held the town. The CPJP signed a ceasefire with the government of CAR on June 12, 2011, and a peace agreement on August 25, 2012. Two CPJP commanders, Noureddine Adam and Mohamed Moussa Dhaffane, opposed the peace deal. Dhaffane left the CPJP in 2012 to start his own rebel group, the CPSK.

Patriotic Convention for the Salvation of Kodro (Convention Patriotique du salut du Kodro, CPSK)

The CPSK was founded in June 2012 by General Mohamed Moussa Dhaffane, formally of the CPJP. Dhaffane was arrested in Chad in 2009, but was released in December 2012. He promptly re-joined the CPSK and the Seleka. He was appointed the minister of water and forests but was accused by the transitional government of recruiting mercenaries and buying weapons and was fired. He was arrested by the Seleka on June 30. At the time of writing he was detained at the Camp de Roux, a military camp occupied by the Seleka in Bangui.

Union of Republican Forces (Union des Forces Républicaines, UFR)

The UFR is a rebel group created by Colonel Florian N’Djadder, a former member of the FACA. The UFR has long maintained a limited presence in CAR. It took advantage of the political benefits offered by the Inclusive Political Dialogue and signed the Libreville Comprehensive Peace Agreement in Bangui on December 15, 2008. It has a limited role in the Seleka.

Alliance for the Rebirth and Rebuilding (Alliance pour la Renaissance et la Refondation, A2R)

The A2R was a loose underground movement

within the former FACA. It opposed the prominent position of ethnic Gbaya in

the army. It was formed in October 2012 by former army officers and sought

connections with the Seleka, from which it has distanced itself since the start

of hostilities.

I. Origins of the March 24 coup

The current attacks on civilians in the Central African Republic should be understood in the broader context of the country’s and region’s fractured political history. [1] Since independence from France in 1960, almost every political transition in the Central African Republic has been marred by political violence. Many politicians, candidates, and combatants have used violence as a means of securing political power. Those committing violence and abuse have rarely been brought to justice.

Rebellion Before 2012

Before 2012, the political landscape in CAR was marked by the presence of multiple rebel groups and three main armed opposition groups: [2] the Popular Army for the Restoration of the Republic and Democracy (Armée populaire pour la restauration de la république et la démocratie, APRD [3] ), the The Central African People’s Democratic Front (Front démocratique du peuple centrafricain, FDPC [4] ), and the UFDR. While the APRD and FDPC were historically active in the northwest of the country, bordering Chad and Cameroon, the UFDR was based in the northeast, on the border with Sudan.

To resolve conflicts between these opposition groups and the government, between 2007 and 2012, several peace agreements, brokered by regional powers, were proffered and signed. The most important agreement, the Global Peace Accord – signed in Libreville, Gabon on June 21, 2008 – was first signed by the APRD and the UFDR. The FDPC later signed an agreement in 2009. The CPJP signed a ceasefire with the government of CAR on June 12, 2011, and a peace agreement on August 25, 2012.

Despite the signing of these agreements, change in northern CAR did not come fast enough for those who felt they were neglected in terms of development and assistance from Bangui. State security and social services were almost totally absent in the north. While gross human rights violations were reported to have diminished, [5] the failure of the state judiciary to hold perpetrators accountable and the high probability that they would remain unpunished fostered resentment. Although some progress was made in the disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration (DDR) process in 2012 with APRD, UFR and FDPC combatants, the lack of a national reintegration strategy and the prevailing security vacuum created additional volatility.

The Seleka emerged in late 2012 into an environment marked by the absence of state institutions, the presence of arms and former members of armed groups, and porous national borders in an unstable region. [6]

Post 2012: The Seleka Coalition− Chadian Influence

The government of Chadian President Idriss Déby has played a role in CAR since the early 1990s. The Bozizé government was installed with Chadian support in 2003. The Déby government is believed to have been a sponsor and perpetrator of human rights abuses against civilians in CAR’s north. In 2008, the Chadian Army, the Armée Nationale Tchadienne, launched numerous cross-border raids on villages in this region, killing civilians, burning villages, and stealing cattle. [7] More recently, in early 2012, the Chadian Army shelled a number of villages along the road between Ouandago and Batangafo, causing the forced displacement of three villages.

In 2012, the CAR government began to lose favor with the Chadian president. Reflecting this falling-out, Chadian members of Bozizé’s presidential guard were called back to N’Djamena in 2012. At the same time, the Chadian government released members of the Seleka who were being held under surveillance in Chad, which freed them to join the rebel coalition forming in CAR. Analysts see Chad’s shifting allegiances in CAR as tied to the need to maintain control of the southern oil belt in Chad, an area where local residents have historically opposed Déby. [8]

Chadian armed rebel groups hostile to Déby, such as the United Front for Change (Front uni pour le changement) or elements of the former Chadian rebel leader Abdel Khader Baba Laddé of the Popular Front for Redress (Front populaire pour le redressement), are said to be using northern CAR as a rear base. [9]

The Seleka coalition, primarily comprising members of the CPJP, the UFDR, and the CPSK, is strongly suspected to include Chadians who have aligned themselves with local rebels. In Bossangoa, Human Rights Watch met with the highest-ranking Seleka official, Colonel Saleh Zabadi. During the meeting, Human Rights Watch asked a young soldier, standing close by, where he was from. The soldier quickly said, “I am from Chad.” Zabadi corrected him and said, “No, he is from Kabo.” Kabo is a town in northern CAR, 60 kilometers south of the Chadian border. The soldier again reiterated, “No, I am from Chad.” [10] Zabadi again insisted the soldier was from Kabo. Human Rights Watch spoke with other Seleka fighters who said they were Chadian.

The national origin of Seleka troops is a source of friction in CAR. Most victims and witnesses with whom Human Rights Watch spoke said they believed the majority of Seleka come from Chad or Sudan, largely because most Seleka fighters do not seem to speak Sango, the most widely used language in CAR. In virtually all accounts of attacks in Bangui and the provinces, victims and witnesses said Seleka members were speaking in Arabic. Human Rights Watch interviewed many Seleka fighters who were not able to communicate with a Sango-speaking translator. (In these cases, interviews had to be done in French with a Seleka commander or in basic Arabic). FOMAC troops operating outside Bangui have confirmed to Human Rights Watch that Seleka fighters in their zones are majority Chadian or Sudanese.

The Peuhl CommunitiesThe security situation in northern CAR is further complicated by long-standing tensions over grazing rights, migration routes, and access to water sources between local farming communities and pastoralist nomadic tribes from CAR, Chad, and Sudan. These include members of the Peuhl cultural group, notably the Mbororo, the Mbarara, and the Fulata, as they are known in CAR. [11] Generally, the Mbororos are considered to come originally from CAR and Cameroon, while the Mbararas are considered to be nomadic tribes from northern Chad. Both tribes consider cattle to determine social status and individual identity. During the Bozizé government, armed bandits from CAR and Chad known as “Zaraguinas” or coupeur de routes (road bandits) kidnapped and assaulted members of the Mbororo and Mbarara communities. The Zaraguinas also often targeted cattle of the nomadic Peuhl communities to sell back for a ransom. As a result of this insecurity, some groups of Mbororo and Mbarara armed themselves against the Zaraguinas. In some areas of northern CAR, the Mbarara have aligned themselves with the Seleka and have participated in attacks on civilians. |

II. Seleka Attacks in the Provinces

When we hear a vehicle, we run into the bush.

—Resident of Zere, June 8, 2013

In June 2013, Human Rights Watch investigated abuses carried out by the Seleka in the provinces of Kémo-Gribingui, Nana Grébizi, and Ouham. Human Rights Watch confirmed that Seleka elements killed scores of civilians who were trying to flee the attacks. Human Rights Watch also documented the widespread and wanton burning of homes. In some villages, every single structure was affected. The destruction was often accompanied by the pillaging of goods, leaving civilian populations utterly destitute.

While the majority of attacks outside of Bangui occurred in villages, the larger towns were not spared. For example, as Seleka forces made their way south in February, they attacked the town of Dekoa. In that attack, four people were killed, eight people were seriously injured, and over 230 homes were burned. [12]

Most villages in rural Central African Republic are situated on roads. As such, Seleka forces and their allies were able to attack numerous villages in quick succession. Villagers told Human Rights Watch that they were sometimes able to flee their homes because they could hear shooting from the next village on the road. However, many villagers had no choice but to stay in the area to continue working their fields. In villages that were not destroyed, Human Rights Watch researchers would enter in their vehicle and see residents fleeing into the bush. [13]

When Human Rights Watch on June 9, 2013, entered the village of Gbade – a village that had been abandoned, but not burned – villagers slowly emerged, carrying machetes and homemade hunting rifles as protection. A resident of Gbade told Human Rights Watch, “Now we only come back for church service….We see nothing here to give us the confidence to come back.” [14]

Another villager from Bougone told Human Rights Watch, “We are here, but... we are afraid. The Seleka still come at night on the same road and we have to run again.” [15]

Attacks on Villages on the Batangafo-Bouca Road: April 10-14, 2013

Human Rights Watch researched abuses by the Seleka and Mbarara that took place in April on the road between Batangafo and Bouca. Between April 10 and April 14, the Seleka attacked a string of villages between Gbadene and Banda along this road. The Seleka began the attack and pillaging on Wednesday, April 10, while riding on motorcycles along the main road; as they travelled, the Seleka shot at residents and forced them to flee into the bush.

According to witnesses, the Seleka first attacked the village of Gbadene, where over 100 homes were pillaged and burned. They then attacked the village of Gbobafio; the entire village—roughly 40 homes—was pillaged and burned. On, Sunday April 14, armed Mbarara returned on horseback and also burned houses in these villages.

While the motivation for these attacks is not completely clear, villagers along this road said that they were triggered by the killing of an Mbarara in the village of Kadi. One villager from Kadi told Human Rights Watch:

The Mbarara … started breaking into houses and pillaging. They were armed....They started shooting all over and a villager killed one of them with his hunting rifle. [16]

The next day, the Seleka returned and attacked villages on both sides of Kadi. Human Rights Watch saw how the entire village of 88 homes in Kadi itself was burned. Some residents of these villages stayed behind to watch the events and identified Adoum Takaji, the self-proclaimed mayor of Batangafo, as coordinating the attacks.

One witness told Human Rights Watch:

The Seleka were numerous.… Takaji gave the orders. The Seleka were shooting all over… but they did not burn the houses. It was on Sunday the 14th that the Mbarara came and burned the village. They came on horseback.… Before Takaji was the mayor he was a delegate for the [herders][17].… He used to come here for meetings so we know him.[18]

In Sirkadi, Human Rights Watch again found the entire village—52 homes along with a church—burned. A witness told Human Rights Watch:

We started hearing shots on that day in the other villages … the Seleka came on motorcycles.... Takaji was with them. Nobody was killed here [because we heard the shots] … the Seleka took all the goats. [Then on Sunday the 14th] the Mbarara came on horses [to burn the village], there was maybe 100 of them. They were shooting in the air. [19]

The Seleka, followed later by the Mbarara, destroyed the small village of Katanga—12 homes— before attacking and destroying the entire village of Bogoro—72 homes. One resident of Bogoro told Human Rights Watch:

When the Mbarara came we ran away. They came shooting. Now we are living [in another village], but there are others living in the bush near their fields….The Mbarara tried to burn the roof of the school, [but it was difficult so] instead they just burned all the books. The school was for the villages of Bogoro, Katanga, Sirkadi, Kadi, Gbobafio, and Banda. It is a primary school. [20]

The Seleka continued to Banda and destroyed the entire village of 10 homes.

All of the residents with whom Human Rights Watch spoke from these locations were living in the bush outside of their villages. As one villager told Human Rights Watch:

They took our goats and our seeds. We are living in the bush and we are hungry. Without security we cannot come back to the village … we cannot come back with the Seleka armed. [21]

Attacks on the Kaga-Bandoro-Mbrès Road: April 14-15, 2013

Seleka forces based in Kaga-Bandoro and Mbrès on April 14-15 carried out a string of attacks on the villages of Nguimale, Maorka, Ndanika, Yangoussou, and Zaire, which are located between the two bases. The attacks, Human Rights Watch research shows, were carried out by Seleka forces to retaliate against the killing of one of their own fighters by a group of villagers in Yangoussou, a large village on this road with over 100 homes. The Seleka fighter, residents of Yangoussou said, threatened them. After he shot a villager in the face, the population retaliated and killed him. Seleka forces stationed in nearby Kaga-Bandoro and Mbrès soon learned of the incident.

Seleka forces from Mbrès then moved on motorbikes up the road and stopped in Nguimale. They entered the town firing their weapons and killed two residents. As one resident told Human Rights Watch, “They shot one woman who was in her kitchen.” [22] The remaining villagers ran into the surrounding bush. The Seleka then burned 27 homes in this village.

Leaving Nguimale, the Seleka moved down the road to Maorka. Villagers told Human Rights Watch that they could hear the shots coming from Nguimale and thus were ready to flee. As one villager told Human Rights Watch:

[When] they entered the village … they started shooting, after they started to burn the first house we ran into the bush. They were burning houses they thought had people in them or if they saw people near them. [23]

Before burning the homes, the Seleka would loot anything of value; anything deemed worthless was burned. The villagers, distraught at seeing their possessions stolen or burnt, watched from afar. As one witness told Human Rights Watch:

We men would run into the bush, but then we come back to watch. They burned everything, our mattresses, our beds, our mats. They took our peanuts, our seeds, our manioc, our goats and our chickens. They took everything but the pigs. [24]

Human Rights Watch counted 38 houses burned by the Seleka at Maorka.

The Seleka then attacked the village of Ndanika. According to witnesses, Seleka forces burned houses there before moving on to Yangoussou. On Monday, April 15th, the Seleka returned to Ndanika to burn the rest of that village. As in other villages, the residents were prepared for an attack. As one resident told Human Rights Watch, “They came with two 4x4 vehicles and they started to burn houses again.” [25]

From Ndanika, the Seleka elements moved down to Yangoussou. A resident told Human Rights Watch:

When they came into the village they were shooting in the air to make people flee. If they saw someone they shot at them and then they pillaged and burned the houses. We had to take our women, children, and elderly into the bush. My house was burned. They burned our bed, mattresses, my bike, two radios, and our peanut stock. [26]

From Yangoussou the Seleka attacked Zaire, the last village before Mbrès. Villagers from Zaire said that they had already fled, so the Seleka burned their homes.

Attacks on Villages on the Bouca-Bossangoa Road: April 18, 2013

According to villagers, on April 18, 2013, Seleka elements arrived in the villages of Boubou and Zere from the direction of Bossangoa. Witnesses told Human Rights Watch the Seleka travelled this road in a 4x4 vehicle and indiscriminately shot at civilians as they entered the villages.

Living and Dying in the BushSend troops here so we do not have to live in the bush! Come quickly so we can live in the village because we sleep in the forest like animals! — Resident of Boubou, June 8, 2013 Villagers who had been forced to abandon their homes told Human Rights Watch of extremely difficult living conditions in the bush. As of June 2013, humanitarian agencies such as the International Committee of the Red Cross were able to give only very limited support to some affected areas. For example, in some regions, villagers said they had received plastic tarp sheeting to protect them from the elements. However, in other regions villagers are living with no support. Villagers told Human Rights Watch of whole communities that had fled the Seleka. A village authority from Maorka told Human Rights Watch, “The majority of the villagers are still in the bush. There are 113 families living in the forest, only a handful have come back.” [27] In multiple communities, Human Rights Watch heard accounts of extremely difficult living conditions. One resident from Maorka told Human Rights Watch: Now I sleep in the fields. I made a small hut out of leaves for my wife and our three children. I cannot come back because we do not have beds or our food stock and there is no security. [The Seleka] took all of our farming tools, they took our hoes. We have to use our hands. [28] The abandonment of these communities has meant that health services have stopped, since clinics in affected villages are either destroyed or closed. In a country with some of the lowest health indicators in the world, this has exacerbated a situation already teetering on the verge of a crisis. [29] Access to education is also affected, due to the destruction of schools, the looting of education materials, and the displacement of teachers and students. Human Rights Watch spoke with the headmaster of a school that serves four villages with a total of 449 students. He said, “All of the materials were pillaged. Most of the students are now hiding in the bush. Two of our four teachers are hiding.” [30] Human Rights Watch was given credible information on numbers of people who have died in the bush since the Seleka forced them to abandon their villages. For example, 23 people from six villages (Nguimale, Maorka, Ndanika, Yangoussou, Maraomba and Zaire) have died in the bush. In the villages of Bogoro, Katanga, Sirkadi, Kadi, Gbobafio, and Banda—attacked between April 10 and 14, 2013, villagers have told Human Rights Watch that 15 people, including many children, have died since fleeing the village. They are dying from illness, hunger, and exposure to the elements. One villager from Ndanika told Human Rights Watch that when the Seleka came, “I was with my dad who was sick, we had him hidden behind the house….[We had to flee].…My father died in the bush.” [31] Residents of Yangoussou told Human Rights Watch: Two children from the village are sick. They are with us in the bush. They have constant pain in the head and legs. They were injured fleeing the attack on the village. [32] The rains, while important for a harvest, are only compounding the difficulty of living with no protection. As one villager from Zere told Human Rights Watch, “Some people have started to come back to the village because the rains are coming, but most people are still out in the bush.” [33] |

A villager of Boubou told Human Rights Watch, “They just shot at people, they did not pillage.” [34] The Seleka killed two men in Boubou as they were trying to flee and they then chased people on a forest path out of the village. [35] They burned 53 houses.

The same Seleka elements then moved to Zere where, according to a witness:

They came in a vehicle and starting shooting and broke in the doors and pillaged all the houses in the village. Then they burned some of them…. They were shooting at everyone.”[36]

The Seleka executed a captured resident of Zere and burned 46 homes.

Attack of Ouin: May 1, 2013

In late April and early May 2013, Seleka forces carried out a string of attacks on a road leading west out of Batangafo toward Kambakota. One horrific attack took place in the village of Ouin on May 1. Multiple witnesses in different villages along this route confirmed that Seleka forces carried out the attacks with the participation of the self-proclaimed mayor of Batangafo, Adoum Takaji. Members of the Mbarara community also attacked villages outside Batangafo around this time, according to witnesses.

In Ouin, the Seleka summarily executed five residents; five more were killed while trying to flee. Eyewitness testimony indicates that the attack of Ouin was linked to an incident that took place in late April in the village of Kolo, located a few kilometers from Ouin. On that day, villagers reported that several Mbarara had tried to steal a cow belonging to a resident of Kolo. There was an altercation, and an Mbarara was killed. In revenge, the Mbarara attacked Kolo and the nearby village of Baraka, killing one individual there. The Mbarara burned houses in both villages. Residents from Kolo and Baraka then fled to Ouin, the largest village in the surrounding area.

Seleka forces, self-appointed Mayor Takaji, and men described as members of Batangafo’s Muslim community arrived in Ouin on May 1. The villagers were fearful. Takaji tried to reassure the villagers in order to make them come out of their homes. As one resident told Human Rights Watch:

Mayor Takaji went door to door in the village to ask people to leave their homes and come to a meeting to talk with the Seleka. The first few left their homes, five of them, and were grouped under a tree … their arms were attached to each other. They were then shot down one by one. Takaji was only 50 meters away. [37]

Multiple witnesses told Human Rights Watch that one individual did not die straight away and the Seleka cut his throat.

Another witness told Human Rights Watch, “The mayor was not armed, but he took people out to be killed.” [38] Residents told Human Rights Watch that after the execution:

The Seleka shot at all the houses. They killed five more people in the neighborhoods. The entire village ran away when the shooting started. [39]

Some residents returned to the village later to bury their dead. However, the Seleka also returned and started to fire on the villagers again. As one resident told Human Rights Watch:

We were burying our own dead and they started to shoot at us again; we all fled back into the bush…. I can still smell the dead. [40]

In research carried out in June 2013, Human Rights Watch found Ouin completely abandoned. After eventually emerging from the bush, residents of Ouin showed Human Rights Watch the fresh graves of the 10 killed individuals. Residents confirmed to Human Rights Watch that they were now living in the surrounding forest. One resident told Human Rights Watch, “The populations of Bakara, Kolo and Ouin are all living in the bush. There are many of us there, many.” [41]

Human Rights Watch met with Adoum Takaji who admitted that “there are still Seleka troops that are not controlled” and that “the Mbarara have profited with the presence of the Seleka.” He also confirmed that he had “volunteered” to be the mayor, but that his authority was recognized in Bangui by the Seleka chef d’antenne [42] and spokesperson, Issa Amat, and that he was “with the head of the Seleka [in Batangafo] every day.” However, he denies being in Ouin on the day of the attacks. Instead, he claims he went there days later:

When I went the village was totally empty. I hear that 11 people were killed there. Since these events I have tried to reassure the population but they are scared. We want them to come back to the village and re-start their lives. I have tried to explain that the Seleka are here to reassure their security. [43]

Attacks on Villages on the Bossangoa–Boguila Road: May 19, 2013

On May 19, 2013, Seleka elements based in Boguila attacked villages along the road leading to Bossangoa. Numerous credible reports indicate that they first burned over 150 homes in Gbaduma before moving down the road to Bodoro. [44]

In Bodoro, four Seleka vehicles entered the village. According to a witness, as the Seleka arrived, “They started shooting at the people. They gave no warning, they did not say anything. Five people were killed here and three people were injured.” [45]

The Seleka moved down the road to the village of Bougone, where, according to a witness:

They did not announce anything, they just started shooting at the village….They were aiming at the young men. After we fled they pillaged the village house by house. They took everything....They stayed here maybe 40 minutes. In that time they pillaged the entire village. When they shoot, we run, but we could hear them from the bush.[46]

Three men were killed in Bougone. According to witnesses, the men were shot while trying to flee. The Seleka then moved on to Gbade:

The Seleka started shooting in the village as the people were fleeing… people were killed while running away. Then they pillaged all the houses. They went house by house.[47]

Four people were killed in Gbade while trying to flee the Seleka, according to witnesses.

In Bossangoa, Human Rights Watch spoke to Seleka Col. Saleh Zabadi and his executive secretary, Sacrifier-Boris Yamassamba. The villages of Boubou, Zere, Gbaduma, Bodoro, Bougone, and Gbade fall under Zabadi’s responsibility. Zabadi told Human Rights Watch:

There were no villages burned here…. I don’t know about these killings in the villages. Our territory is calm. There are no problems…. I was on the roads two or three weeks ago to Boguila, it was fine.[48]

Zabadi and Yamassamba reiterated to Human Rights Watch that any movement on the road between Boguila and Bossongoa must have their prior knowledge and approval. Yamassamba, told Human Rights Watch: “The villagers are happy to see us. They see us as liberators. They come and wave to us and are happy.” [49]

Attacks on Villages on the Batangafo—Bouca Road: June 2, 2013

Human Rights Watch researched attacks on civilians and destruction of villages that took place in June 2013 on the Batangafo–Bouca road. Human Rights Watch documented the destruction of the entire village of Yangoumara, including the village church, but was not able to find any inhabitants of the village. However, in the next village, Gbi-Gbi, where 34 homes were burned along with the village church, Human Rights Watch was able to speak with some villagers. According to these witnesses, the Seleka had attacked Yangoumara and Gbi-Gbi on Sunday, June 2. The witnesses told Human Rights Watch that members of the Seleka were coming from Bouca on their way to Yangoumara, but: “[T]hey stopped here at Gbi-Gbi and killed a woman….They shot her when she was fleeing. They shot her in her side. There were eight Seleka total.” [50]

Witness testimony points to these attacks being carried out as revenge on communities after a villager killed a Seleka fighter who was trying to steal a cow in Yangoumara. At the time of writing, the population of the villages of Gbi-Gbi and Yangoumara were still living in the bush.

Human Rights Watch met with Jean-Michel Bangui, the executive secretary of Colonel Bashir Muhammad, who is the highest-ranking member of the Seleka in Bouca. Bangui candidly told Human Rights Watch, regarding Yangoumara and Gbi-Gbi: “We burned those villages. That was us, the Seleka.” [51] He claimed that certain Seleka soldiers were “children” and that they were angry after a villager shot their captain, so they acted in revenge. He said:

These children decided to do this. I do not know which one. No order was given. But the children got upset because the captain was shot, they were nervous so they shot.[52]

Human Rights Watch interviewed Bangui in the presence of Seleka troops, who appeared to be very young and possibly child soldiers in the age range of 13-15. Later in the interview, Bangui said that the houses had been burned by bullets touching the straw roofs; the houses, he said, had not been burned intentionally. When asked by Human Rights Watch what actions he was taking as a local administrator to reassure the safety of local residents, Bangui insisted that the priority was to catch the villager who had shot the Seleka in Yangoumara: “People are living in the bush. We are trying to call the people back to the villages. But now we need to know who the real criminal in this affair is; who the shooter is.” [53]

Local Seleka AuthoritiesI am the law. −Jean-Michel Bangui, executive secretary of Col. Bashir Muhammad, Bouca, June 8, 2013 Outside Bangui it is difficult to establish lines of command within the Seleka. Most Seleka officials whom Human Rights Watch interviewed said that if problems pre-dated their arrival, they were because of a former commander. For example, in Bossangoa, Col. Saleh Zabadi—the highest ranking Seleka officialinthe region—told Human Rights Watch: [The villagers] had run into the bush when Colonel Abdulim was here. I do not know his first name … [but] I have no problems here. [54] Other authorities control their regions with complete impunity. Jean-Michel Bangui, the executive secretary of Bouca (see above) was open with Human Rights Watch about how he interprets his authority. He told Human Rights Watch: Let me tell you something. There is no law now. You know that the international community has recognized that the president is ruling by decree…. After 18 months there will be a law. I am an army official now, I have that authority. [55] Bangui told Human Rights Watch that he was the police, prosecutor, and judge when it came to crime prevention in Bouca: I conduct the investigations, arrest people, and put them in detention. And I will make a decision on the duration of their detention…. After the investigation we will know who is who and who did what. [56] When Human Rights Watch questioned Bangui as to investigative methods, he replied, “We torture them so they can tell the truth.” [57] Bangui insisted that he had studied law and was qualified to fill this role in Bouca. Bangui allowed Human Rights Watch to visit three prisoners that he was holding in an office of the sub-district headquarters. Human Rights Watch found three men in a room sitting in their own urine and faeces. The men seemed afraid and appeared to have been beaten; one had a swollen face and a bloody right eye. Bangui said they were local thieves. |

Human Rights Watch met Noureddine Adam, minister of public security, who denied the Seleka had played any role in the attacks documented in the provinces. However, he did concede that the situation was complex:

[In] the provinces, there are a lot of groups operating there. The Fulata, the Mbororos, they come from Sudan, Chad, CAR. We try to resolve the disputes. [58]

In response to witness accounts presented by Human Rights Watch on the attack of the village of Yangoumara, Adam said, “These are related to the disputes between Muslims and Christians in the area. The Muslims are those who are setting fire, burning the villages.” [59] In response to evidence of attacks on villages on the road between Kaga-Bandoro and Mbrès, Adam told Human Rights Watch, “The Mbororos, the Peuhls, are responsible for these attacks in this area.” [60]

In response to allegations of human rights

abuses, Adam denied any Seleka involvement saying that the only problem was the

lack of funds to train the Seleka to respect human rights, “We will

respect human rights when we have the means.”

[61]

III. Abuses Committed by Seleka in Bangui

Throughout April, May, and June 2013, Human Rights Watch investigated abuses that Seleka forces carried out in Bangui after they took power. The following accounts are representative of patterns of abuses that Human Rights Watch was able to corroborate.

Attack on Damala - March 27, 2013

On March 27, three days after the coup, Seleka soldiers killed 17 people in the neighborhood of Damala near the Bangui International Airport. The attack began when four Seleka soldiers entered the neighborhood and assaulted a local official with the aim of stealing a large truck. This official told Human Rights Watch:

I [tried] to explain to them that the vehicle helped us because it allows us to transport people to the hospital. They were Chadians, but one of them spoke some Sango. [But] they pulled me out of my house and they started to beat me with their guns. They told me to give them the key to the vehicle. I said, “I do not have it.” They pushed and beat me to the truck; by this point my arm was broken. They got me to the truck and they started to pillage shops that were nearby. They made me sit on the ground.[62]

Local youth from the neighborhood were watching these events unfold. One youth who was later shot by the Seleka told Human Rights Watch:

I saw members of the Seleka beating the local chief. They were beating him with their guns and with their belts. We followed them from a distance to the truck. The Seleka were speaking and yelling in Arabic. [63]

Young men in Damala, seeing a local authority beaten in this fashion, started to throw stones. According to one victim:

[The youth started] throwing rocks and it made the Seleka very angry; they started shooting their guns in the air and then they shot at the people. People started to run away … at this moment one of the Seleka turned and shot me. He did not say anything. I had nothing in my hands. When he shot me I had my hands up.[64]

The victim was shot in the abdomen and still suffers as a result of his injury. After firing on the population, the four Seleka started to move into the Damala neighborhood, but they soon ran out of ammunition and were attacked by area residents. As a witness told Human Rights Watch, “[One of the] Seleka ran out of bullets and the youth got him with stones. They killed him. The other Seleka had [left] for reinforcements.” [65]

When members of the Seleka returned, they exacted revenge on the residents of Damala. A witness told Human Rights Watch:

The Seleka reinforcements came in one vehicle, a 4x4, with 12 Seleka on it. They had a big gun on it that one man used; he stayed on the vehicle shooting. Others were chasing people in the neighborhood. [66]

Because of the confusion created by the initial shooting, it is difficult to ascertain how many people the four Seleka soldiers killed at the Damala market, but Human Rights Watch received reports of 17 people killed in the neighborhood that day by the Seleka.

- Rodrigue Gbenerio was one victim. He had a business charging cell phones near the market in Damala. Witnesses say he was the first person whom the Seleka killed when they started firing. A witness told Human Rights Watch: “[When the] youth … started to throw rocks, the Seleka started shooting. They killed Rodrigue right away.” [67] Another witness said: “Rodrigue was killed where he had his kiosk.” [68]

- Raphael Bingilego was killed outside his home by the Seleka on March 27, 2013. A family member told Human Rights Watch: “I was in my house and there were many people outside trying to understand what was happening. Then [the] Seleka arrived shooting. Everyone ran from the front of the house and I got down. [Raphael] ran around [the outside] of the house. When the Seleka left we went outside and I found him. He had been shot in the back; the bullet went out his chest. He was lying face down. He was already dead.” [69]

- Ludociv Hehine was in his home that same day when the Seleka broke open the door and killed him. A family member of Hehine told Human Rights Watch that when the Seleka approached his home, his “mother and father hid in the kitchen and Ludociv and I stayed in the salon with his daughter. We had the door closed, but the Seleka had seen people running [near] our house. The Seleka came and shot open the door. They were two: one Seleka came in and the other one waited outside. He came and shot everywhere in the salon. Ludociv got down near the table and I fell behind a chair. Ludociv put up his hands. The Seleka fighter cried out and shot him twice in the chest and then left.” [70]

Attack on Walingba–April 12, 2013

On April 12, a Seleka rocket propelled grenade (RPG) injured 15 people in the Walingba neighborhood. 13 children were among the injured, two of whom required amputations. An eyewitness said:

It was about 4:30 p.m., I was standing by my house in front of the soccer field where the children were playing. We heard a loud explosion. There was a lot of dust everywhere. When the dust settled, I rushed to the scene and saw the bodies of the children injured. The Red Cross ambulance arrived fifteen minutes later and took the wounded to the hospital. We found the point of impact which was around 50 cm in diameter….These children live here in the neighborhood. [71]

The Seleka had been in control of Bangui since March 24 when this attack occurred and despite Human Rights Watch inquiries we received no reports of anyone but Seleka moving with RPGs.

Killings at the Ngaragba Bridge – April 13, 2013

On April 13, Seleka forces killed at least 18 unarmed civilians in the area surrounding the Ngaragba Bridge near the Ouango and Kassai neighborhoods in Bangui. According to eyewitnesses, Seleka elements drove their vehicle onto the bridge and hit a funeral procession walking toward the local cemetery. Enraged, civilians from the procession began to throw stones at the Seleka fighters. Within minutes, additional Seleka forces arrived. They shot what witnesses said was a rocket-propelled grenade into the crowd and began shooting indiscriminately at civilians who were trying to flee the area and run to their homes in the direction of the Ouango neighbourhood. Witnesses told Human Rights Watch that they saw Seleka forces kill a priest on the bridge who was appealing for calm. One witness told Human Rights Watch:

The priest walked toward the Seleka elements … raising a Bible in his hand and calling [them] to stop shooting. Three Seleka fighters stepped out of the pick-up, walked toward him and shot him dead.[72]

Another witness told Human Rights Watch:

After the Seleka convoy started shooting at the crowd, a woman with a baby on her back was on the street past the bridge, when she was shot by a Seleka fighter and left dead in the street with the baby crying on her back.[73]

Another eyewitness described the attack on the bridge to Human Rights Watch:

After the coffin was hit and the priest was killed at the bridge, people were terrified. They ran in all directions to escape. The Seleka called for reinforcements from Camp de Roux. The Seleka fighters loaded a rocket in their RPG [and] they pulled into the crowd and shot a rocket at the bridge. There were many people injured. The Seleka started chasing at people who fled. There were lots of dead bodies on the road and many wounded.[74]

The Attack on Boy-Rabe – April 13 and 14

On the weekend of April 13 and 14, Seleka forces carried out an organized attack on the neighborhood of Boy-Rabe in Bangui. A local authority described to Human Rights Watch how the Seleka started the attack:

15 vehicles entered Boy-Rabe. The first vehicle had an officer on board. They went to the market. He asked who I was and I said I was [a local official]. He said, “We have heard that Bozizé distributed arms in Boy-Rabe to fight the Seleka.” I said, “Please, come out and see if there is one weapon in the hands of the youth here.” [But they] just wanted to pillage. They had their vehicles ready to take people’s property. Then they started shooting. They went into the neighborhood and shot at people.[75]

Another witness told Human Rights Watch:

I saw them shooting their guns at us, at the people. This is the technique of the Seleka, to come in and to pillage. If there are people there they will not hesitate to shoot to make people leave. Sometimes they kill people, sometimes not. Leaving the neighborhood, the people resisted and members of the Seleka shot at the crowd. They take over Bangui and only a few days later they come to do this. It is not correct.[76]

Minister of Public Security and Seleka General Noureddine Adam told Human Rights Watch that the Seleka operations in Boy-Rabe in mid-April were “organized disarmament operations.” [77] The former minister of water and forests and former Seleka general, Mohamed Moussa Dhaffane, told Human Rights Watch that, “[It was a priority] to disarm Boy-Rabe. Boy-Rabe is a neighborhood of 60 percent of families of elements of the Presidential Guard. They are all there.” [78] However, residents of Boy-Rabe said:

This [was] not disarmament….They did not come to disarm. They came to pillage. There are no soldiers left in the quarter. If this had been a real disarmament they should have called the FACA and had them bring their arms.[79]

Human Rights Watch has uncovered dozens of killings in Boy-Rabe of unarmed civilians through the weekend of April 13 and 14, 2013, and into the following week. The stories of a few victims follow.

The Killing of Simon AssanaSimon Assana was a resident of Boy-Rabe. The Seleka executed him at his home on April 14, 2013. Assana was trying to protect people fleeing the fighting. A witness in a nearby house described his killing: Members of the Seleka [were] coming down the road ahead of the house [and] three women ran across the street. They are not from [Boy-Rabe], I think they were fleeing the fighting from [another neighborhood]. The Seleka saw the women running across the street. Simon was on his terrace and he yelled to them “Come here! Come here!” They ran into his compound, he opened the door and they ran into his house. The Seleka members on the road saw this. They pulled up to his house and got out. There were two Seleka on foot. One stayed in the truck….They followed the women, they were running after them. Simon was outside his house on the veranda. There is a small route between our compounds, so I could see everything. The Seleka members said to him, “Where are the people who passed here?” Simon said, “Nobody is here.” The Seleka wanted to go into the house. They started to climb the stairs so he closed the door behind him. Simon said, “It is only my children there in the house.” He blocked the door. One of the Seleka said, “Give me your money.” Simon said, “I don’t have any money.…The Seleka soldier said, “Give me your phone”. Simon touched his body to show he had nothing. He said, “I have no telephone. I have no money”. The Seleka soldier walked down the steps of the veranda. He looked at Simon and he shot him twice in the stomach. He was about four or five feet away from Simon. He held his rifle by his side when he shot. The Seleka soldier went back to the truck. Simon fell down on the ground. I heard the truck leave and I ran out of my house. The three women in the house came out. Two young men from the neighborhood also saw it. They also came over. We lifted Simon and brought him into the house. He was trying to speak, but he could not. We put him on the floor. I had my hand on his chest and he stopped breathing about five minutes later.[80] |