“They Know Everything We Do”

Telecom and Internet Surveillance in Ethiopia

Glossary of Abbreviations

BPR Business Process Reengineering

CALEA Communications Assistance for Law Enforcement Act

CESCR Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights

CITCC China International Telecom Corporation

CSO Law Charities and Societies Proclamation

CUD Coalition for Unity and Democracy

DPI Deep Packet Inspection

DW Deutsche Welle

EDF Ethiopian Defense Forces

EICTDA Ethiopian Information and Communication Technology Development Agency

EPRDF Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front

EPRP Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Party

ESAT Ethiopian Satellite Television

ETA Ethiopian Telecommunication Agency

ETC Ethiopia Telecommunications Corporation

GPS Global Positioning System

ICCPR International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

ICS Intelligent Charging System

ICT Information and Communications Technology

IM Instant Message

INSA Information Network Security Agency

ITU International Telecommunication Union

MCIT Ministry of Communications and Information Technology

NGO Nongovernmental organization

NISS National Intelligence and Security Services

OLF Oromo Liberation Front

ONC Oromo National Congress

ONI Open Network Initiative

ONLF Ogaden National Liberation Front

OPC Oromo People’s Congress

PID Project Information Document

PSCAP Public Sector Capacity Building Program

SIM Subscriber Identity Module

SMS Short Message Service

TPLF Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front

UAV Unmanned Aerial Vehicles

UDJ Union for Democracy and Justice

VOA Voice of America

VOBME Voice of the Broad Masses of Eritrea

VoIP Voice over Internet Protocol

VSAT Very Small Aperture Terminal

WTO World Trade Organization

ZTEsec ZTE Special Equipment Company

Summary

One day they arrested me and they showed me everything. They showed me a list of all my phone calls and they played a conversation I had with my brother. They arrested me because we talked about politics on the phone. It was the first phone I ever owned, and I thought I could finally talk freely.

— Former member of an Oromo opposition party, now a refugee in Kenya, May 2013

Since 2010, Ethiopia’s information technology capabilities have grown by leaps and bounds. Although Ethiopia still lags well behind many other countries in Africa, mobile phone coverage is increasing and access to email and social media have opened up opportunities for young Ethiopians—especially those living in urban areas—to communicate with each other and share viewpoints and ideas.

The Ethiopian government should consider the spread of Internet and other communications technology an important opportunity. Encouraging the growth of the telecommunications sector is crucial for the country to modernize and achieve its ambitious economic growth targets.

Instead, the ruling Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), a coalition of ethnically-based political parties in power for more than 20 years, continues to severely restrict the rights to freedom of expression, association, and peaceful assembly. It has used repressive laws to decimate civil society organizations and independent media and target individuals with politically-motivated prosecutions. The ethnic Oromo population has been particularly affected, with the ruling party using the fear of the ongoing but limited insurgency by the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) in the Oromia region to justify widespread repression of the ethnic Oromo population. Associations with other banned groups, including Ginbot 7, are also used to justify repression.

As a result, the increasing technological ability of Ethiopians to communicate, express their views, and organize is viewed less as a social benefit and more as a political threat for the ruling party, which depends upon invasive monitoring and surveillance to maintain control of its population.

The Ethiopian government has maintained strict control over Internet and mobile technologies so it can monitor their use and limit the type of information that is being communicated and accessed. Unlike most other African countries, Ethiopia has a complete monopoly over its rapidly growing telecommunications sector through the state-owned operator, Ethio Telecom. This monopoly ensures that Ethiopia can effectively limit access to information and curtail freedoms of expression and association without any oversight since independent legislative or judicial mechanisms that would ensure that surveillance capabilities are not misused do not exist in Ethiopia.

All governments around the world engage in surveillance, but in most countries at least some judicial and legislative mechanisms are in place to protect privacy and other rights. In Ethiopia these mechanisms are largely absent. The government’s actual control is exacerbated by the perception among Ethiopia’s population that government surveillance is omnipresent. This results in considerable self-censorship, with many Ethiopians refraining from openly communicating on a variety of topics across the telecom network.

This report is based on research conducted between September 2012 and February 2014, including interviews with more than 100 people in 11 countries. It documents how the Ethiopian government uses its control over the telecommunications system to restrict the right to privacy and freedoms of expression and association, and access to information, among other rights. These rights are entrenched in international law and frequently touted by the government as part of Ethiopia’s constitution. In practice, they are undercut by problematic national laws and practices by the authorities that wholly disregard any legal protections.

Websites of opposition parties, independent media sites, blogs, and several international media outlets are routinely blocked by government censors. Radio and television stations are routinely jammed. Bloggers and Facebook users face harassment and the threat of arrest should they refuse to tone down their online writings. The message is simple: self-censor to limit criticism of the government or you will be censored and subject to arrest.

Information gleaned from telecom and Internet sources is regularly used against Ethiopians arrested for alleged anti-government activities. During interrogations, police show suspects lists of phone calls and are questioned about the identity of callers, particularly foreign callers. They play recorded phone conversations with friends and family members. The information is routinely obtained without judicial warrants. While this electronic “evidence” appears to be used mostly to compel suspects to confess or to provide information, some recorded emails and phone calls have been submitted as evidence in trials under the repressive Anti-Terrorism Proclamation.

The government has also used its telecom and Internet monopoly to curtail lawful opposition activities. Phone networks have been shut down during peaceful protests. Some high-profile Ethiopians in the diaspora have been targeted with highly advanced surveillance tools designed to covertly monitor online activity and steal passwords and files.

In rural Ethiopia, where phone coverage and Internet access is very limited, the government maintains control through extensive networks of informants and a grassroots system of surveillance. This rural legacy means that ordinary Ethiopians commonly view mobile phones and other new communications technologies as just another tool to monitor them. As a result, self-censorship in phone and email communication is rampant as people extend their long-held fears of government interference in their private lives to their mobile phone use. These perceptions of phone surveillance are far more intrusive than the reality, at least at present.

Ethiopia has acquired some of the world’s most advanced surveillance technologies, but the scale of its actual telecom surveillance is limited by human capacity issues and a lack of trust among key government departments. But while use of these technologies has been limited to date, the historic fear of ordinary Ethiopians of questioning their government and the perception of pervasive surveillance serves the same purpose: it silences independent voices and limits freedom of speech and opinion. Human Rights Watch research suggests that this may just be the beginning: Ethiopians may increasingly experience far more prevalent unlawful use of phone and email surveillance should the government’s human capacity increase.

While monitoring of communications can legitimately be used to combat criminal activity, corruption, and terrorism, in Ethiopia there is little in the way of guidelines or directives on surveillance of communications or use of collected information to ensure such practices are not illegal. In different parts of the world, the rapid growth of information and communications technology has provided new opportunities for individuals to communicate in a manner and at a pace like never before, increasing the space for political discourse and facilitating access to information. However, many Ethiopians have not been able to enjoy these opportunities. Instead, information and communications technology is being used as yet another method through which the government seeks to exercise complete control over the population, stifling the rights to freedom of expression and association, eroding privacy, and limiting access to information—all of which limit opportunities for expressing contrary opinions and engaging in meaningful debate.

Court warrants are required for surveillance or searches but in practice none are issued. Intercepted communications have become tools used to crack down on political dissenters and other critics of the ruling party. Opposition party members, journalists, and young, educated Oromos are among the key targets.

The infrastructure for surveillance was not created by the Ethiopian government alone, but with the support of investors in the Internet and telecom sector, including Chinese and European companies. These foreign companies have provided the products, services, and expertise to modernize the sector.

Ethiopia should not only ensure that an appropriate legal framework is in place to protect and respect privacy rights entrenched in international law, but also that this legal framework is applied in practice. Companies that provide surveillance technology, software, or services should adopt policies to ensure these products are being used for legitimate law enforcement purposes and not to repress opposition parties, journalists, bloggers, and others.

Recommendations

To the Government of Ethiopia

- Enact protections for the right to privacy to prevent abuse and arbitrary use of surveillance, national security, and law enforcement powers as guaranteed under international law applicable to Ethiopia. Surveillance should occur only as provided in law, be necessary and proportionate to achieve a legitimate aim, and be subject to both judicial and parliamentary oversight.

- Legal safeguards should limit the nature, scope, and duration of possible surveillance, the grounds required for ordering them, and the authorities competent to authorize, carry out, and supervise them.

- Ensure that information obtained through email or telephone interception or access to call records is inadmissible in courts unless a court warrant has been obtained. All laws enabling the admissibility of intercepted information in court should be amended to require a court warrant, including the Criminal Code, the Telecom Fraud Proclamation, and the Prevention and Suppression of Money Laundering and the Financing of Terrorism Proclamation.

- Enact protections for call records and other “metadata” so that such information may not be collected or accessed by police, security, or intelligence agencies without a court order and oversight to prevent abuse, unauthorized use or disclosure of that information.

- Enforce the requirements for a court warrant prior to interception/surveillance under the Anti-Terrorism Proclamation and the NISS Proclamation. Ethio Telecom should not provide access to metadata or recorded phone calls without a warrant from a competent, independent and impartial court in line with international standards. Any data collection or surveillance conducted by the Information Network Security Agency (INSA) or National Intelligence and Security Services (NISS) should require prior court approval.

- Immediately unblock all websites of political parties, media, and bloggers and commit to not block such websites in the future.

- Immediately cease all jamming of radio and television stations and commit to not jam radio and television stations in the future.

- Cease harassing individuals for exercising their right to freedom of expression online through social media and blogs.

- Appropriately discipline or prosecute officials, regardless of rank or position, who arbitrarily arrest or detain or ill-treat individuals on the basis of unlawfully intercepted or acquired information. Impose criminal penalties for illegal surveillance by public or private actors.

- Report annually on the government’s use of surveillance powers. This reporting should include: the number of data requests made to Ethio Telecom, cybercafés, or other mobile and Internet service providers; the number of requests for real-time interception or recording of phone calls; and the number of individuals or accounts that were implicated by such requests.

- Provide protections for the rights to freedom of expression and privacy to prevent abuse of emergency powers to shut down networks or intercept communications.

- Repeal or amend all laws that infringe upon

privacy rights, the right to information, and the rights to freedom of

expression, association, movement, and peaceful assembly, including the Anti-Terrorism

Proclamation, the NISS Proclamation, the Telecom Fraud Proclamation, and the

Prevention and Suppression of Money Laundering and the Financing of Terrorism,

to bring them in line with international standards. Amendments should include

the following articles:

- Anti-Terrorism Proclamation, article 23(1) and (2) (permitting non-disclosure of information sources and hearsay) and the NISS Proclamation, article 27 (requiring cooperation with NISS information requests). Ethio Telecom and INSA officials should cooperate with NISS only when a court warrant is granted facilitating access to user information.

- Telecom Fraud Proclamation, articles 6(1) (criminalizes dissemination of messages about activities punishable under the anti-terrorism law) and 10(3) (criminalizes commercial use of VoIP).

To International Technology and Telecom Companies Serving Ethiopia

- Assess human rights risks raised by potential business activity, including risk posed to the rights of freedom of expression, access to information, association, and privacy. Assessments should address risk of misuse of non-customized, “off-the-shelf” equipment sold to governments that may be used to facilitate illegal surveillance or censorship. Assessments should also address the risk of customizing products and services for law enforcement, intelligence, and security agency customers.

- As part of a tender or contract negotiation process, inquire about the end use and end users of the products or services being provided, especially for “dual use” products, including “lawful intercept” surveillance software and equipment.

- Develop strategies to mitigate the risk of abuses linked to business operations and new contracts, including by incorporating human rights safeguards into business agreements. Such strategies should be consistent with the Global Network Initiative (GNI) principles and the United Nations “Protect, Respect, and Remedy” Framework for business and human rights.

- Adopt policies and procedures to stop or address misuse of products and services, including contractual provisions that designate end use and end users, the violation of which would allow the company to withdraw services or cease technical support or upgrades. Promptly investigate any misuse of products or services and take concrete steps to address human rights abuses linked to business operations.

- Adopt human rights policies outlining how the company will resist government requests for censorship, illegal surveillance, or network shutdowns, including procedures for narrowing requests that may be disproportionate or challenge requests not supported by law.

- Extend human rights policies and procedures to address the actions of resellers, distributors, and other business partners.

- Commit to independent and transparent third-party monitoring to ensure compliance with human rights standards, including by joining a multi-stakeholder initiative like the GNI.

- Advocate for reform of surveillance or censorship laws to bring them in line with international human rights standards.

- Review any contracts or engagements initiated before 2008 and craft strategies to address and mitigate any adverse harm that may flow from operations that currently continue under these contracts, consistent with guidance provided by the GNI and UN principles, both launched in 2008. As contracts come up for renewal, incorporate human rights safeguards into newly negotiated contracts.

To the Governments of China, Germany, Italy, the United Kingdom, and Others

- Regulate the export and trade of “dual use” surveillance and censorship technologies such as deep packet inspection equipment and intrusion software. Require such companies subject to national jurisdiction operating abroad to report on any human rights policies and due diligence activity to prevent rights abuses and remedy them if they arise.

- Introduce or implement legal frameworks, such as an independent ombudsperson, that allow government institutions to monitor the human rights performance of companies selling surveillance software, technology, or services subject to national jurisdiction when they operate abroad in areas that carry serious human rights risks. Frameworks should include an effective complaints mechanism accessible to individuals and communities in Ethiopia, and those representing them, who allege harmful conduct or impact by companies subject to national jurisdiction doing business in Ethiopia, with findings and decisions binding on companies.

- Communicate an expectation to the government of Ethiopia that companies operating in Ethiopia should be able to implement the recommendations outlined above.

To the World Bank, African Development Bank, and other Donors

- Undertake human rights due diligence on telecommunication projects in Ethiopia, to prevent directly or indirectly supporting violations of the rights to privacy or freedom of expression, association, or movement; or access to information including through censorship, illegal surveillance, or network shutdowns. This should include assessing the human rights risks of each activity prior to project approval and throughout the life of the project, identifying measures to avoid or mitigate risks, and comprehensively supervising the projects including through third parties. This due diligence should extend to any government or private sector partners to ensure that they are not implicated in violations.

- Publicly and privately raise with government officials concerns about censorship, illegal surveillance, and network shutdowns and that human rights violations may undermine development priorities.

Methodology

This report is based on research conducted between September 2012 and February 2014 in Ethiopia and 10 other countries, including interviews with Ethiopians living outside the country. The report documents through interviews, review of secondary material, and Internet filtering testing, how the Ethiopian government uses its control over the telecommunications system to restrict the right to privacy and freedoms of expression, information, and association, among other rights.

Over 100 individuals were interviewed, including those whose right to privacy, access to information, and freedom of expression have been abused, former and current intelligence and security officials, Ethio Telecom employees, and other government officials. All were interviewed individually. Interviews were carried out in person and via telephone in Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda, South Sudan, Israel, the United States, and five countries in Europe.[1] Interviewees included people from a wide range of backgrounds, age, ethnicity, urban, rural, and geographic origin.

Interviews were all conducted in English or with interpreters from Amharic, Afan Oromo, or other Ethiopian local languages into English. Different interpreters were used. Human Rights Watch took various precautions to verify the credibility of interviewees’ statements. None of the interviewees were offered any form of compensation for agreeing to participate in interviews. All interviewees voluntarily consented to be interviewed and were informed of the purpose of the interview and its voluntary nature, including their right to stop the interview at any point.

In addition to interviews, Human Rights Watch consulted a variety of secondary material, including academic articles and NGO reports, that corroborates details or patterns described in the report. This material includes previous Human Rights Watch research as well as information collected by other credible technology experts and independent human rights investigators.

Internet filtering testing was carried out in Ethiopia in July and August 2013 in collaboration with the University of Toronto’s Citizen Lab, an institute that conducts research on information technology, human rights, and global security. Testing was carried out in Addis Ababa and several other cities. Human Rights Watch tested whether Uniform Resource Locators (URLs) were accessible within the country, with a focus on those websites that had a reasonable likelihood of being blocked based on the Open Network Initiative’s (ONI) previous testing in 2012. ONI’s 2012 investigation also tested whether a range of websites were accessible from within Ethiopia. For this report, a total of 19 tests were run over seven different days to ensure reliability of results.

In part because the Ethiopian government restricts human rights research in the country, this report is not a comprehensive assessment of the surveillance situation in Ethiopia. Human Rights Watch and other independent national and international human rights organizations face extraordinary challenges to carrying out investigations in Ethiopia. This is mainly because of the difficulty of assuring the safety and confidentiality of victims of human rights abuses, given the government’s hostility towards human rights investigation and reporting. Increasingly, the families of individuals outside of Ethiopia who provide information can also be at risk of reprisals.

The Ethiopian government routinely dismisses Human Rights Watch reports, regularly criticizes Human Rights Watch as an organization, and dismisses the findings of our research. This heightens concerns that any form of involvement with Human Rights Watch, including speaking to the organization, could be used against individuals. The authorities have, in the past, harassed and detained individuals for providing information to, or meeting with, international human rights investigators and journalists.

Human Rights Watch conducted research for this report inside Ethiopia, but many of the people were interviewed outside of the country, making it easier for them to speak openly about their experiences. For fear of possible reprisals, all names and identifying information of interviewees have been removed, and locations of interviews withheld, where such information could suggest someone’s identity. In certain cases, pertinent information has been omitted altogether because of concerns that disclosing such information would reveal the identity of interviewees.

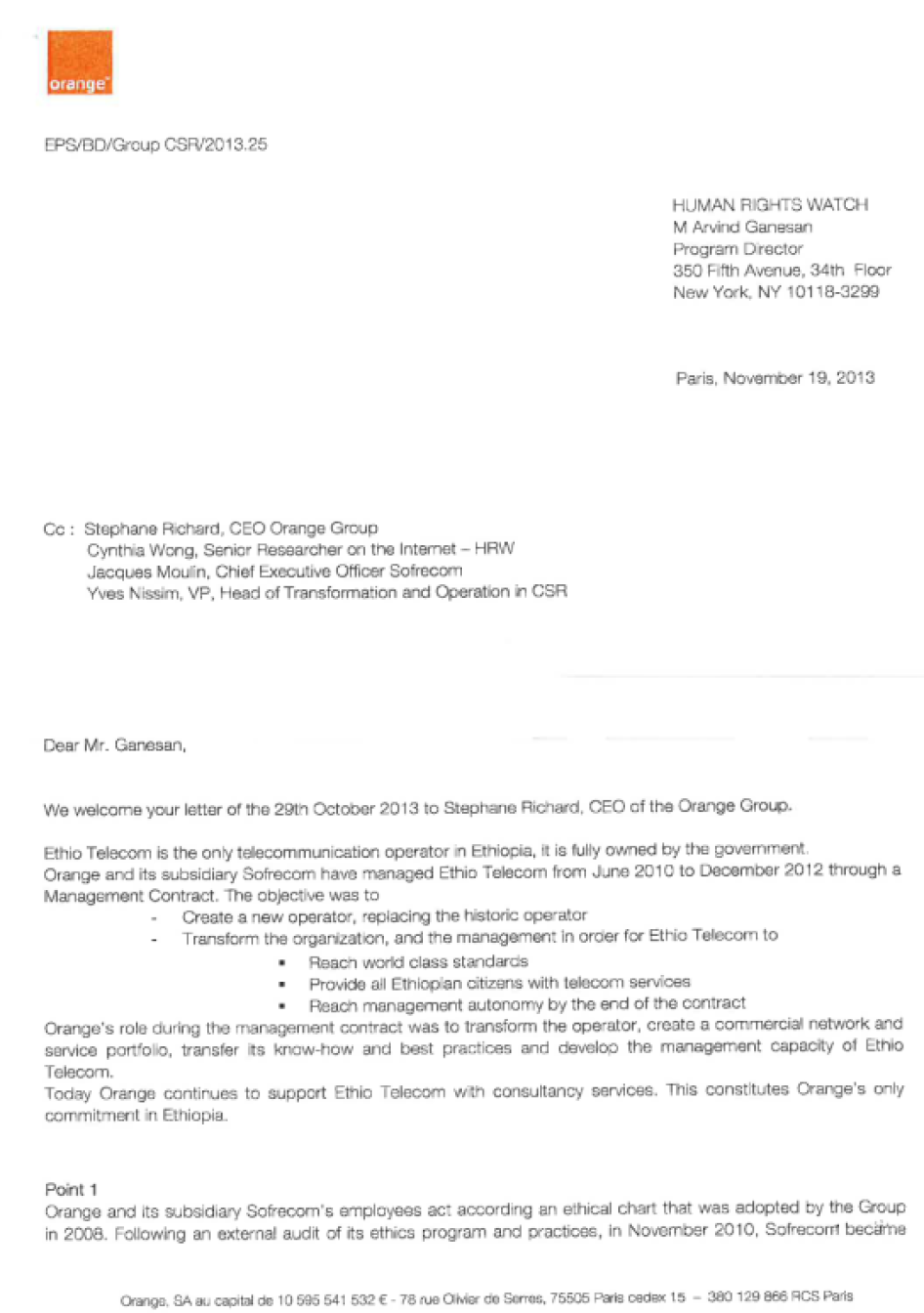

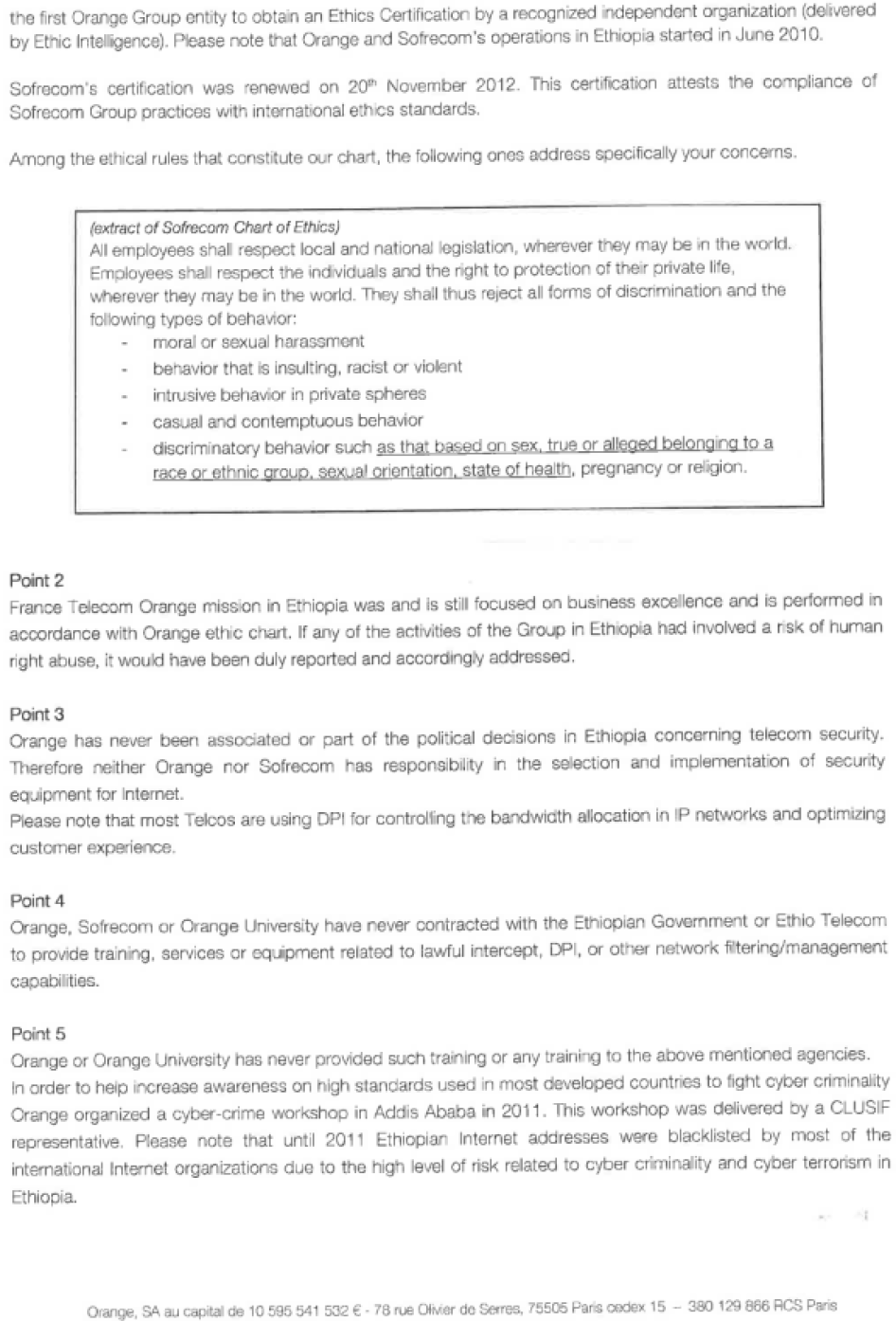

Human Rights Watch wrote to the government of Ethiopia, ZTE, Sinovatio (previously known as ZTE Special Equipment Company), Huawei, France Telecom-Orange, Hacking Team, Gamma/FinFisher, and the World Bank to request input on the findings from this report.[2] Any responses received were included in this report as annexes or posted on the Human Rights Watch website.

I. Background

Patterns of Repression and Government Control

Since the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) came to power in 1991, a coalition of ethnically-based political parties led by the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), has used various means to consolidate political power.[3]

Repressive measures aimed at restricting freedom of expression and association, as well as access to information, have increased since the controversial 2005 elections.[4] These measures include the harassment, arbitrary detention, and prosecution of opposition leaders, journalists, and activists. The passage in 2009 of the Anti-Terrorism Proclamation (anti-terrorism law) and the Charities and Societies Proclamation (CSO law) further stifled critical voices. The anti-terrorism law has been used to charge and convict journalists, religious leaders, and others for exercising their rights to free expression and peaceful assembly. Many nongovernmental organizations that worked on human rights, governance, and other issues affected by the CSO law have been forced to close or curtail their activities. Little dissent is allowed and individuals are frequently detained for openly questioning government policies and perspectives.[5]

Independent media in Ethiopia has also been decimated in recent years. Very few independent publications exist, and the continual threat of being charged under the anti-terrorism law hangs over journalists who are critical of the government.[6] Many journalists opt for self-censorship instead, avoiding topics deemed politically sensitive. Directives have been passed making printing presses liable for the content of their publications and radio and television stations are either state-run or minimize criticisms of government policy in order to be able to operate.[7]

Ethiopia’s ruling party also dominates the political, economic, and social spheres by completely controlling access to state resources, employment, and benefits.[8] This dual strategy of restricting independent voices and encouraging ruling party support paid off for the ruling party in the 2010 parliamentary elections, as the EPRDF won 99.6 percent of the seats, although this raised many questions about the conduct of the elections.[9]

One reason for the EPRDF’s political dominance is that it implements an effective and pervasive community-level surveillance system throughout Ethiopia, a system that relies on active monitoring and reporting of various kinds of activity. But it also benefits from deeply entrenched historical and social attitudes towards the government. The EPRDF uses its well-established network of informants throughout the country to monitor the activities and movements of individuals and households at the kebele (village) level, often intimidating them into supporting the ruling party. A complex system of individual and household surveillance is in place. Commonly known as the 5:1 system, it has many variations depending on location but all involve Ethiopians monitoring the day-to-day activities of other Ethiopians, including friends, family members, colleagues, and neighbors. [10] Information on a stranger visiting a rural village or individuals who are openly soliciting support for opposition political parties, for example, are usually swiftly reported to kebele leaders. Dissenters are dealt with in a variety of ways, from informal pressure to threats. Continued dissent is passed up the chain of command for further action. In most cases, the mere knowledge that someone may be monitoring your activities is enough to restrict free speech and compel you to self-censor.

Strategically-placed individuals—teachers and police officers, for instance—have increased monitoring responsibilities. These surveillance systems are set up throughout the country to monitor election compliance, to gather intelligence, and to serve other functions. Since anybody could be an informant, the net effect is that people are very afraid to speak openly to anyone but their closest confidants. There is very little in the way of public discourse about sensitive political issues and little opportunity to express dissent in a safe manner.

Ethiopia’s population remains predominantly rural, over 85 percent, and these tools and techniques of repression are effective in a country where phone use is still limited and much communication remains by word of mouth.[11] But recent years have seen a rapid increase of mobile phone and Internet use throughout the country. Ethiopia has ambitious growth plans in its telecommunications sector and a reliable and widespread telecom service is crucial for the government to reach its economic targets.[12] Telecommunications growth will give Ethiopians new and unprecedented opportunities to share news, ideas, and access information in a timely manner. However, these developments also present a challenge for government: how to embrace the many economic benefits of a growing telecom sector while ensuring that increased access does not translate into unfettered social and political mobilization and public protest of the kind seen in North Africa and the Middle East in recent years.

Targets of Surveillance

While the Ethiopian government has legitimate national security concerns, government’s use of surveillance puts a significant focus on individuals deemed to be a political, rather than a security, threat.

According to former intelligence officials who spoke to Human Rights Watch, the selection of some surveillance targets is not necessarily based on the security threat they pose, and the actual methods of surveillance are sometimes unlawful. More intensive surveillance is undertaken on individuals who are connected with opposition parties—whether registered political parties or those that the government has listed as criminal or terrorist organizations. Individuals who speak to journalists or opposition figures are also often targeted, and in the past few years those associated with the Muslim protests have come under increased monitoring.[13]

Former intelligence officials told Human Rights Watch that prominent individuals suspected of being connected with opposition political parties and armed movements, especially Ginbot 7 and the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF), are frequently the focus of targeted telecom surveillance. Intelligence officials also said that officials from registered political parties including the Union for Democracy and Justice (UDJ) are also frequent targets of surveillance.[14] The security services may also target individuals due to their ethnicity or family connections, irrespective of whether they belong to a banned organization.

The Ethiopian government considers Ginbot 7, the OLF, and the Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF) to be terrorist organizations under the Anti-Terrorism Proclamation.[15] Ginbot 7 was formed by some former members of the opposition Coalition for Unity and Democracy (CUD) party who fled Ethiopia after being detained and convicted of “outrages against the constitution,” among other charges, following the controversial 2005 elections.[16] Ginbot 7 is based outside of Ethiopia, has not contested any of Ethiopia’s elections, and some of its leaders have been convicted under various laws. It is not a legally registered political party.

The Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) is one of the oldest ethnic Oromo political organizations, founded in the 1960s as part of Oromo nationalist movements fighting against the Haile Selassie government.[17] The OLF’s fragile alliance with the TPLF splintered early in the 1990s and it withdrew from elections and government. Since then it has waged what most observers view as a fairly limited and ineffectual armed resistance against the EPRDF.[18] However, the government uses the specter of an ongoing OLF “armed struggle” to justify widespread repression of Oromo individuals. Regional government and security officials routinely accuse dissidents, critics and students of being OLF "terrorists" or insurgents. Thousands of Oromo from all walks of life have been targeted for arbitrary detention, torture and other abuses even when there has been no evidence linking them to the OLF.[19]

Human Rights Watch interviews suggest that a significant number of Oromo individuals have been targeted for unlawful surveillance. Those arrested are invariably accused of being members or supporters of the OLF. In some cases, security officials may have a reasonable suspicion of these individuals being involved with OLF. But in the majority of cases, Oromos were under surveillance because they were organizing cultural associations or trade unions, were involved in celebrating Oromo culture (through music, art, etc.) or were involved in registered political parties.

Like the OLF, the Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF) was initially a political party, but began a low-level armed insurgency in Ethiopia’s Somali region in response to what it perceived to be the EPRDF’s failure to respect regional autonomy, and to consider demands for self-determination.[20] In 2007, the ONLF scaled up armed attacks against government targets and oil exploration sites, triggering a harsh crackdown by the government.[21] As with the government’s counterinsurgency response to the OLF, the Ethiopian security forces have routinely committed abuses against individuals of Somali ethnicity, including arbitrary detentions, torture, and extrajudicial killings, based on their ethnicity or perceived support for the ONLF.

Since the passage of the Anti-Terrorism Proclamation in 2009, Ethiopia has used its overly broad provisions to target individuals and organizations that express opinions contrary to government policy or positions, often claiming that they are members or supporters of these banned organizations. While the government may have legitimate security interests in monitoring individuals who support armed anti-government movements, there are two serious concerns with the manner in which the authorities conduct surveillance activities. One is that even where an individual may be a legitimate target, the methods used to monitor and investigate their activities can be unlawful, for instance disregarding the need for judicial warrants. A second concern is that the Ethiopian security forces have repeatedly targeted a broad spectrum of individuals based solely on ethnicity, participation in lawful activities, or family connections. One former intelligence official said:

We would often try to gather specific evidence that people were linked to terrorist groups like OLF, ONLF, or Ginbot 7. Ginbot 7 [is] not a problem in the country anymore, and they know that but they are still using the threat of Ginbot 7 to harass people, even if there is no threat. OLF is not a terrorist threat either. ONLF is the only real threat. Oromo people, especially the young, still have sentiment for OLF. They [the authorities] use OLF to marginalize Oromos—there is a threat from the idea of OLF, but not from the actual OLF.[22]

Former intelligence officials also described the gathering of intelligence on international NGOs. Information was often collected about the individuals employed, the finances of the organization, and the NGO’s foreign connections.[23] It is not known how widespread NGO surveillance is in Ethiopia. Most of the intelligence was gathered from individuals employed by the organization who were acting as informants or from intelligence officials who were hired as employees in some other capacity in the organization. Use of telephone or email surveillance was minimal according to former intelligence officials. However, one former intelligence official involved in the monitoring of several foreign NGOs told Human Rights Watch that, “We have the potential and there is nothing to stop us from doing that.”[24] The Prevention and Suppression of Money Laundering and the Financing of Terrorism Proclamation 657/2009 gives security officials broad powers of surveillance over the financial activities of NGOs.[25]

Former officials also described to Human Rights Watch being involved in gathering intelligence on Ethiopians living in the diaspora. This involved “old-school” techniques of infiltrating diaspora communities and gathering information on the key diaspora players and the extent of their involvement in Ethiopian politics or media. There is no evidence that emails or telephone calls are monitored in any substantive way. There are increasing reports of Ethiopian embassies in various capitals putting more and more effort into recruiting informants within diaspora communities. Former government officials report that the government facilitates individuals acquiring scholarships to study abroad in order to recruit those individuals as informants. Ministry of Foreign Affairs officials play a significant role in this and, according to several former employees, maintain records of financial transactions from the diaspora to Ethiopians in-country. Ostensibly this is part of Ethiopia’s efforts to combat the financing of terrorism and money laundering but information is kept that goes far beyond that.[26]

With a young population, many Ethiopians know nothing other than extensive government control over their lives, and it is through this lens that many view the opportunities that enhanced access to mobile and Internet services may bring to their lives. A refugee currently living in Kenya summed up the situation:

They have complete control. I was a teacher and was told I needed to join [EPRDF], I refused and was fired. My family [members] were farmers, because of me they did not receive seeds or any benefits from the kebele. “That is for government” they were told. Everyone I know is angry with our government, but people are fearful for their lives if they get involved in politics. There are thousands of people here in [refugee location] who have fled because they dared question government. Mobile phones came to my kebele [village] several years ago. At first we were excited but it hasn’t made any difference to us, it’s just another way they control us. They listen to our calls and arrest us if we talk to people they don’t like. All this so-called development hasn’t changed anything—they still have complete control, we can’t say anything, we are still poor, and if you don’t support their ways you end up living here [as a refugee].[27]

The opportunities that these technologies provide to increase freedoms of expression, access to information, and freedom of association are greatly diminished for those living in fear as they are afraid to use these technologies to their full extent. As one man said, “We have no choice in the matter. They run the phone service. They know our phone number and where we live. They know everything about us.”[28]

Fears of Surveillance

Many Ethiopians believe that the introduction of technologies such as the mobile phone and Internet-based technologies are a new way for the government to exercise control and monitor Ethiopians. Such perceptions may derive in part from Ethiopia’s long history of highly authoritarian and centralized governance, which stretches back well before the EPRDF.[29]

Many Ethiopians with whom Human Rights Watch spoke thought that all their phone calls and emails are monitored, and that none of these mediums are safe to communicate on. Because of the perception and fearof surveillance, they said they self-censor their telephone and Internet communications. These fears appear to persist to different degrees throughout the country, regardless of ethnicity. Many told Human Rights Watch that the basis for their fear was rumors of arrests due to the contents of phone calls but very few people could provide specific details. Even more described hearing of others being arrested based on receiving phone calls from certain people outside of Ethiopia.

Many refugees who have fled Ethiopia for various reasons told Human Rights Watch they have been told by their relatives in Ethiopia not to call because it is too dangerous. Inside Ethiopia, many individuals avoid communicating about many topics, or only answer in very innocuous ways or speak using a variety of code words. As one man said, “We use so many code words and avoid talking directly about so many topics that often I’m not sure I know what we are really talking about.”[30] Other individuals stated that the phone is only used to make appointments with no substantive conversation ever taking place. The net effect is that the fear of telephone surveillance adds to the harms caused by the reality of phone surveillance—it restricts what people are willing to communicate and with whom they are willing to communicate.

Self-censorship is also prevalent in email and online communications. Very few people who spoke to Human Rights Watch, including senior government officials, ever use their .et email addresses because of the perception of pervasive surveillance. Many individuals within Ethiopia use fake email addresses and avoid using certain sensitive keywords. Others refuse to use email altogether. One notable exception to this is Facebook, where Ethiopians seem to speak much more openly.[31]

Regional and woreda-level government employees also practice high degrees of self-censorship and many will not communicate about sensitive subjects on email or telephone. NGO workers and foreign government officials also readily censor the contents of their messages, unclear about the actual extent of surveillance and not willing to risk reprisals.

As a former farmer from Oromia told Human Rights Watch:

We all know they watch every step we make. We can’t go anywhere without them knowing, we can’t speak bad things about government without having trouble, we can’t get education or services without supporting them. We know they listen to all our phone calls and Internet. We know all of this, but what can we do? We are all too scared to speak our mind.[32]

Telecommunications and Media in Ethiopia

Mobile phone usage has grown dramatically in Ethiopia in the last few years, although coverage is still very limited in comparison to other sub-Saharan African countries. According to the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), Ethiopia has 23.7 users per 100 people and just 0.9 landline subscribers per 100 people.[33] By way of comparison, neighboring Kenya has 72 mobile subscriptions per 100 people and Nigeria has 68 mobile subscriptions per 100 people.[34] Mobile rates are expensive and the network is prone to frequent and lengthy outages, particularly outside of Addis Ababa, much to the frustration of Ethiopians.[35] While mobile phone use is increasing, many Ethiopians in more remote areas continue to rely either on shared landlines or on VSAT telephones available at the local Ethio Telecom office.[36]

The majority of Internet sites with Ethiopian content are hosted on servers outside of Ethiopia and are run by the diaspora, although the number of websites hosted by Ethiopians in-country are increasing. Many Ethiopian sites are in English, although there are a significant and increasing number of Amharic sites available along with a number of sites in Somali and Afan Oromo.

Internet usage in Ethiopia is still in its infancy with less than 1.5 percent of Ethiopians connected to the Internet and fewer than 27,000 broadband subscribers countrywide. By contrast, neighboring Kenya has close to 40 percent access.[37]The majority of Internet users are located in Addis Ababa. According to the ITU, Ethiopia has some of the most expensive broadband in the world.[38] Given these costs, Ethiopians usually access the Internet through the growing number of cybercafés or from their mobile phones.[39] Internet has been available to mobile phone subscribers since 2009.[40] Wi-Fi Internet is increasingly available in many of the more expensive hotels and cafes. Connectivity speeds countrywide are quite low, and are prone to frequent outages.

The Ethiopian government has ambitious growth targets in the telecommunications sector. Ethiopia aims to increase mobile subscribers and mobile coverage six-fold over 2009-2010 levels by 2013-2014 and to increase Internet levels twenty-fold, according to Ethiopia’s Growth and Transformation Plan.[41] The plan contains three key strategies for implementing this growth: telecom provider upgrades to meet international standards, the use of domestic products and services, and the “establishment and effective enforcement of comprehensive policy and regulatory frameworks to prevent and control illegal activities in the industry.”[42]

Facebook use is growing more rapidly in many developing countries in comparison to more developed countries, where Facebook has a longer history of use. In Ethiopia, Facebook use is becoming increasingly popular with many of the young and educated to connect and share ideas and perspectives.[43] Despite legislative restrictions, Skype continues to be used widely.[44] Gmail, Hotmail, and Yahoo! Mail are the most popular webmail services and Paltalk is widely used in Ethiopia for group discussions.[45] Twitter has not been widely adopted.

Radio is still one of the most important mediums through which Ethiopians receive information. While television plays a larger role in urban areas, radio is still key in rural areas. One study found that 80 percent of Ethiopians use radio as a source of information while 53 percent said radio was their most important source of information. This study also reiterated the importance of word-of-mouth communication in Ethiopia, with nearly 50 percent identifying word of mouth as a source of information.[46] The radio and television sectors are dominated by government-affiliated stations. There are several private FM stations mainly focused on Addis Ababa affairs and no privately run television stations based within Ethiopia.

State Monopoly on Telecommunication Services

State-owned Ethio Telecom is the only telecommunications service provider in Ethiopia. It controls access to the phone network and to the Internet and all phone and Internet traffic must use Ethio Telecom infrastructure. There is no other service provider available in Ethiopia. Ethio Telecom therefore controls access to the Internet backbone that connects Ethiopia to the international Internet. In addition, Internet cafés must apply for a license and purchase service from Ethio Telecom to operate.

Ethiopia has been under pressure to liberalize its telecom sector from the World Bank and others to allow increased competition, but has thus far steadfastly refused to liberalize the sector.[47] Ethiopian Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn in mid-2013 resisted calls for privatization, calling the telecom sector “a cash cow for government coffers” and stressed that Ethio Telecom revenues were being used to fund the proposed Djibouti-Addis railroad.[48] Ethiopia’s desire to be a full member of the World Trade Organization (WTO) has renewed the calls for telecom liberalization.[49] However, Chinese telecom equipment giants ZTE and Huawei have been building and upgrading much of the country’s telecom infrastructure since at least 2003.[50]

The desire to control the telecom sector has led to a grossly underdeveloped telecommunications system in comparison to regional neighbors.[51] This has the effect of stunting economic growth, particularly in rural areas, and limiting opportunities for the spread of ideas and information across the country.[52] But retention of this key sector allows government to more easily control and monitor who and how Ethiopians access the telecom and Internet services. The existence of private sector companies in the telecom sector could increase the difficulty for government of accessing communications records without going through additional steps or legal processes.

History of Telecommunications in Ethiopia

The Ethiopia Telecommunications Corporation (ETC) was originally established in 1952, and since that time has been Ethiopia’s sole telecommunications provider. In 2006, ETC took a major step towards modernizing its outdated infrastructure, signing contracts worth US$2.4 billion with three major Chinese companies—ZTE, Huawei, and China International Telecom Corporation (CITCC)—to rapidly develop the country’s telecommunications infrastructure.[53] As a result, these companies have played a large role in laying Ethiopia’s main fiber optic communications network.[54] Prior to this time, Ethiopia’s telecom infrastructure had been developed in an ad hoc manner by a number of foreign companies.

In addition, in 2006, ZTE signed a three-year, $1.6 billion deal to become ETC’s sole equipment vendor for nine equipment packages. [55] The exact category of equipment sold under the deal is unclear, but ZTE was tasked with a major upgrade and expansion of both fixed line and mobile infrastructure and services. ZTE sells a range of telecommunications equipment, software, and services, including network switches, mobile handsets, and software systems. [56] As Zhang Yanmeng, chief executive officer of ZTE’s Ethiopia subsidiary stated in 2009, “This is the world’s only project in which a national telecom network is built by a sole equipment supplier.” [57] Some have expressed concerns about the lack of transparency and heightened risk for corruption because of the nature of these deals. [58]

In December 2010, ETC became rebranded as Ethio Telecom, and outsourced management functions to France Telecom (now operating as Orange) via its subsidiary Sofrecom. [59] According to France Telecom-Orange (Orange), the objective of the management contract was to transform and modernize the operations of Ethio Telecom to “world class standards,” including through capacity building for managers and transfer of know-how and best practice. [60] Ultimately, the goal was to improve delivery of telecom services in Ethiopia and achieve “management autonomy” by the end of the contract.

Orange, through its subsidiary Sofrecom, was to oversee this broad restructuring of Ethio Telecom as part of the nationwide Business Process Reengineering (BPR) initiative, seen by many as the first steps towards privatization of Ethiopia’s telecom operator. [61] The latest round of BPR in Ethiopia began after the 2005 elections and involved an overhaul of the structures and work processes of law enforcement, security, and other key institutions in an effort to improve efficiency.

By mid-2008, many of the BPR processes were completed nationwide, with staff reductions in many institutions. Former Ethio Telecom employees told Human Rights Watch of qualified personnel being removed from key positions because they were not EPRDF party members or because they questioned government policy. [62] They alleged that senior staff were often replaced by EPRDF cadres who did not seem to have the necessary qualifications.

In January 2013, Ethio Telecom’s management agreement with Orange ended and Ethiopian managers, mostly EPRDF cadres, took over the key positions. Under Orange’s management, telecommunications coverage in Ethiopia grew from 8 to 25 percent. [63] In the same period, the number of Ethio Telecom employees dropped from 12,600 to 8,600. [64] At the conclusion of the initial contract in December 2012, Orange and Ethio Telecom signed an additional one-year agreement, under which Orange would continue to provide support for “ network design, architecture, technology selection negotiation and related technical areas.” [65]

In June 2011, Ethio Telecom issued a tender inviting international suppliers to submit proposals to upgrade Ethio Telecom’s infrastructure. Companies that registered interest included Ericsson, Nokia, ZTE, Huawei, and China International Telecom Corporation. [66] In August 2013 it was announced that ZTE and Huawei were the successful bidders in a $1.6 billion deal, though the exact details and breakdown of duties has not been announced. [67] Ethiopia’s telecom infrastructure is outdated, but Ethiopia has ambitious plans to update that infrastructure through their partnership with ZTE and Huawei.

Institutions of Ethiopia’s Telecommunication and Surveillance Apparatus

Until 2010, the Ethiopian Telecommunication Agency (ETA) was the government regulator for phone and Internet networks in Ethiopia that “specifies technical standards and procedures for provision of Telecommunications Services.” It granted the ETC (now Ethio Telecom) a license in 2002 as Ethiopia’s sole provider of telecommunication services and Internet services.[68]

The Ethiopian Information and Communication Technology Development Agency (EICTDA ) played a key role in overseeing programs and polices related to information and communications technology (ICT) activities. EICTDA was formed in 2005 as an autonomous organization under the Ministry of Capacity Building. It formulated the National ICT policy in 2009, and managed the Woredanet program.[69]

The Woredanet program, which was partially funded by the World Bank and other donors, is intended to provide “ICT services such as video conferencing, directory, messaging and Voice Over IP, and Internet connectivity” to regional governments and local administrations throughout Ethiopia. According to government media, the program had reached 950 woredas and government offices by April 2013.[70]Cisco Systems, a US telecommunications equipment company, won a tender in 2003 to build the core network supporting WoredaNet and a related project, SchoolNet, which connects hundreds of secondary educational institutions across the country and provides access to the Internet and ICT equipment.[71] Subsequent projects also networked Ethiopian universities and equipped them with eLearning centers (UniversityNet) and connected agricultural centers (AgriNet) and hospitals (HealthNet).

The Ministry of Communications and Information Technology (MCIT), formerly the Ministry of Information, assumed the responsibilities of both the ETA and EICTDA in 2010.[72] The MCIT is responsible for overseeing the implementation of communications and technology policies and programs in Ethiopia.[73] According to various former intelligence and Ethio Telecom officials, MCIT plays a major role in determining which radio and television programs are jammed and likely play a key role in determining which websites are blocked.[74] They are also responsible for the licensing of private media. The current minister is Debretsion Gebremichael, who replaced Bereket Simon, a longtime EPRDF member and advisor to the late Prime Minister Meles Zenawi. Debretsion is also one of the deputy prime ministers, the current chairperson of Ethio Telecom, and a former deputy director of NISS, underscoring the strong links between Ethio Telecom, the intelligence apparatus, and the Ministry of Communication and Information Technology. He was also the director-general of EICTDA during implementation of the Woredanet program and is a key TPLF member.

The National Intelligence and Security Services (NISS) is Ethiopia’s intelligence and security agency and has a broad mandate. While federal police and other law enforcement agencies have various roles and responsibilities in Ethiopia’s security sector, the NISS takes the lead for any matters of national security and intelligence. It has always had a murky mandate. The July 2013 passage of the NISS Proclamation should have clarified that mandate, but the law contains vague language that gives NISS broad powers to investigate threats “against the national economic growth and development activities” and to gather intelligence on serious crimes and terrorist activities.[75]

The Information Network Security Agency (INSA), a relatively new yet increasingly powerful branch of the security apparatus, was established to “ensure the security of information and information infrastructure to facilitate their use for the implementation of the country’s peace, democratization, good governance, and development programs.”[76] Accountable to the prime minister, INSA plays an important role in Internet monitoring and filtering of websites and is increasingly integrated with Ethio Telecom and other departments with information management mandates. It plays a key role in facilitating access to citizen’s private digital communications for security and police forces, working closely with Ethio Telecom. INSA’s role is constantly evolving and it is taking more and more responsibilities as Ethiopia’s telecommunication sector grows.

In addition to various local informants, three main government departments are formally involved in intelligence gathering in Ethiopia: NISS, the Ethiopian Defense Forces (EDF), and the federal police. While the federal police have wide-ranging law enforcement responsibilities, federal police surveillance capacities are quite limited according to former federal police officials.[77] Together with NISS, the federal police form the joint anti-terrorism task force, although the federal police play a minimal role according to former officials.[78] This task force has been credited for foiling various alleged “terror plots,” many of which led to the detention and subsequent charging of military officers, opposition politicians, and journalists both within Ethiopia and beyond. While federal police, regional police, or EDF soldiers have been present in many of the interrogations where phone records were inappropriately used, the vast majority of cases involved plainclothes security officials from NISS. Typically it is the NISS who most frequently uses copies of phone records and recorded phone calls during interrogations.

Although beyond the scope of this report, various former military officials told Human Rights Watch of the surveillance techniques and technologies used by the EDF. Most EDF intelligence gathering activities appears to be on external military targets whereas NISS focuses more on perceived domestic threats. There appears to be limited cooperation between the EDF and NISS over intelligence operations.

History and Background on Communications Surveillance

Phone wiretapping in its most traditional form involved physically attaching wires to the phone network to listen to private conversations.[79] This tactic has been in common and widespread use by law enforcement around the world for almost as long as phones themselves have been in use. Other devices can be used to capture information about the phone number associated with outgoing or incoming phone calls and time and duration of each call.[80]

Phone calls are connected through exchanges and switches located throughout a telecom network, which was once operated manually until more sophisticated switches were developed. While surveillance and data collection technologies were simple to implement by manually tapping wires or listening at centralized switches, collection and analysis remained time consuming and resource intensive.

Beginning in the 1990s, the widespread transition to digitally switched phone networks and growth of Internet networks made surveillance more complex to implement. However, new laws in the US and Europe boosted the use of wiretapping because it drove standardization of equipment for surveillance and enabled remote tapping of phone lines.[81] In the mid-1990s, the US and European governments began requiring telecommunications operators to make it easier for law enforcement to wiretap digital telephone networks.[82] In part, this took the form of legislation that forced companies to design modern networks and equipment to build in “back doors” that allow “lawful intercept” of communications on a larger scale.[83] This equipment became globally standardized and most telecom equipment sold around the world incorporates a range of surveillance capabilities as a result.[84]

Modern digital technology makes surveillance more powerful and efficient. The move from fixed-line to mobile telephone systems has enabled governments to access and collect a richer store of information about individuals. Mobile operators can enable interception of voice calls and facilitate access to SMS text messages they may retain.[85] Operators also routinely collect and store information that can reveal the location of a mobile phone, though the precision may vary. For billing and other purposes, telecom companies (fixed and mobile) create and maintain “call detail records,” which list phone numbers of incoming and outgoing calls, call time and date, duration of calls, and mobile tower (location) information.[86] Moreover, mobile operators can be compelled to activate Global Positioning System (GPS) chips placed in most “smart phones,” thus revealing the user’s location and enabling prospective location tracking. Because mobile phones and SIM[87] cards each have unique identifiers, such data, when collected in bulk, can be used to create detailed dossiers of communications, associations, and movements over time, tied to specific individuals.[88]

Government surveillance and data collection has also shifted to Internet networks.[89] As the Internet enabled new channels for communicating and accessing information, it has also expanded the range and amount of information that can be monitored. New communications tools like Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP) (voice calls made over Internet networks), chat, email, and social media services can be intercepted, though use of encryption can help shield online activity.[90] In addition, all Internet activity results in large amounts of “transactional” or “metadata,” defined broadly as data about online activity.[91] For example, such data could include email addresses contacted, webpages visited, or Internet protocol addresses, or the geographic location of the parties communicating. Governments can collect this information easily by tapping networks or by compelling or asking companies to hand over data. When collected on a large scale, metadata can be highly revealing of a person’s associations, movements, and activities over time.

As Internet access increases, some governments are adopting or compelling use of technologies like “deep packet inspection” (DPI). Deep packet inspection enables the examination of the content of communications (an email or a website) as it is transmitted over an Internet network. Once examined, the communications can be then copied, analyzed, blocked, or even altered.[92] DPI equipment allows Internet service providers—and by extension, governments—to monitor and analyze Internet communications of potentially millions of users in real time.[93] While DPI does have some commercial applications, DPI is also a powerful tool for Internet filtering and blocking and can enable highly intrusive surveillance.[94]

Finally, some governments have begun using intrusion software to infiltrate an individual’s computer or mobile phone. Also known as spyware or malware, such software can allow a government to capture passwords (and other text typed into the device), copy or delete files, and even turn on the microphone or camera of the device to eavesdrop. Such software is often unwittingly downloaded when an individual opens a malicious link or file disguised as a legitimate item of interest to the target.[95]

In the near future, an increasing amount of data about individuals’ communications, associations, location, and activities will be digitized. At the same time, the cost of computing and digital storage will continue to fall, enhancing governments’ ability to collect and analyze electronic information. As access to mobile and Internet services increases, governments will be able to more efficiently and effectively intrude into the most sensitive aspects of peoples’ private lives.

Phone calls, emails, and associations can be a valuable source of evidence to prosecute serious crimes and prevent legitimate threats to national security. However, surveillance and data collection, especially in bulk, is highly invasive of the right to privacy. International law requires surveillance practices to be regulated by law and subject to strong, independent safeguards to ensure they do not arbitrarily interfere with privacy.[96]

II. Ethiopia’s Control over Information and Communications Technology

The Ethiopian government exerts very tight control over all information and communications technologies through the deliberate jamming of radio and television signals, the monitoring of telephone calls and email communication, and by restricting access to information through blocking various Internet websites. The spread of telephone and Internet use in the country could open up opportunities to share ideas and information across geographical distances and borders in a manner that was inconceivable in Ethiopia a decade ago. But the government’s use and control of this sector violates internationally protected rights to privacy and the freedoms of expression, association, and access to information. Sadly, Ethiopia’s growing Internet and telecom sector, with so much potential to connect Ethiopians and open up access to new information, ideas, and opportunities, is being used as yet another tool against an already oppressed population.

Ethiopia’s Growing Telephone Network: More Opportunities for Government Control?

Given Ethio Telecom’s monopoly over the telecom system and recent technical upgrades enabled by foreign firms, the government of Ethiopia has the technical capacity to access virtually every single phone call and SMS message in Ethiopia. This includes mobile phones, landlines, and VSAT communications, and includes all local phone calls made within the country and long distance calls to and from local phones. Live interception capabilities are increasing and Ethiopia uses its exclusive control of the phone system to limit access to the network during sensitive periods.

Despite having almost unlimited control over the telecom network and the information that is being communicated on it, the ability to use those technologies acquired is limited and distrust between different officials and departments curtails the number of individuals with access to these surveillance capabilities. One former Ethio Telecom employee responsible for querying the Ethio Telecom database for specific phone calls estimated that he received no more than 30 requests per month for these phone calls.[97] As mobile penetration and the government’s surveillance capacity increases, the extent of unlawful surveillance may also increase.

International and national law relevant to Ethiopia’s telecom and Internet surveillance are discussed in detail in the Legal Context section of this report. International human rights conventions to which Ethiopia is party, particularly the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, guarantee fundamental rights that have been repeatedly violated by improperly regulated government surveillance programs.

Under the 1995 Ethiopian constitution, everyone is entitled to the internationally protected rights to freedom of expression, to information, and to privacy. However, various national laws, such as the Mass Media and Freedom of Information Proclamation of 2008, the Telecom Fraud Offence Proclamation of 2012, and the Anti-Terrorism Proclamation, severely infringe on these fundamental rights. Human Rights Watch’s research found, however, that many human rights violations related to the Internet and telecommunications in Ethiopia are not a product of abusive laws, but rather the willingness and ability of the authorities to act without being hindered by any legal framework or possible legal action from the country’s criminal justice system.

“Brute Force” Confiscation

Despite these capabilities, the vast majority of individuals that Human Rights Watch interviewed who had experienced problems with the authorities from their telephone use were not from advanced surveillance technologies, but from security officials confiscating their mobile phone upon their arrest. Security officials, without warrants, would typically go through their phone log, their SMS messages, and sometimes their contact list. In some cases, this was to verify information that security officials already seemed to know but in most cases officials seemed to be acquiring new information. While some of the individuals who were subject to this unsophisticated but effective technique were in remote, rural areas and not high-profile, some very high-profile individuals were subject to this basic technique. In some cases, security officials knew the phone numbers of the people they were interrogating, but in many cases they did not. Given that Ethio Telecom has a comprehensive database of names, phone numbers, and other personal information of all phone owners in Ethiopia, it is clear that many security officials do not have regular access to the information contained in this database.[98]

One high-profile case highlighted the relatively unsophisticated use of the telecom system. In February 2009, US diplomat Brian Adkins was found murdered in Ethiopia.[99] According to former federal police officials, the police retrieved his telephone and went through the last phone numbers he had called. Using the Ethio Telecom database, they cross-referenced the phone numbers to the names and home addresses of these individuals. They interrogated each of them and eventually one of them confessed and was sentenced to 17 years in prison.[100] There was no attempt to access the phone records of these individuals, no attempt to determine the locations of callers, and no attempt to listen to the phone calls between Adkins and these individuals. These capacities all exist within Ethio Telecom’s systems. Despite the technologies existing and being available, only rudimentary techniques were used for this high-profile case.[101]

Unrestricted Access to Phone Call Recordings and Metadata

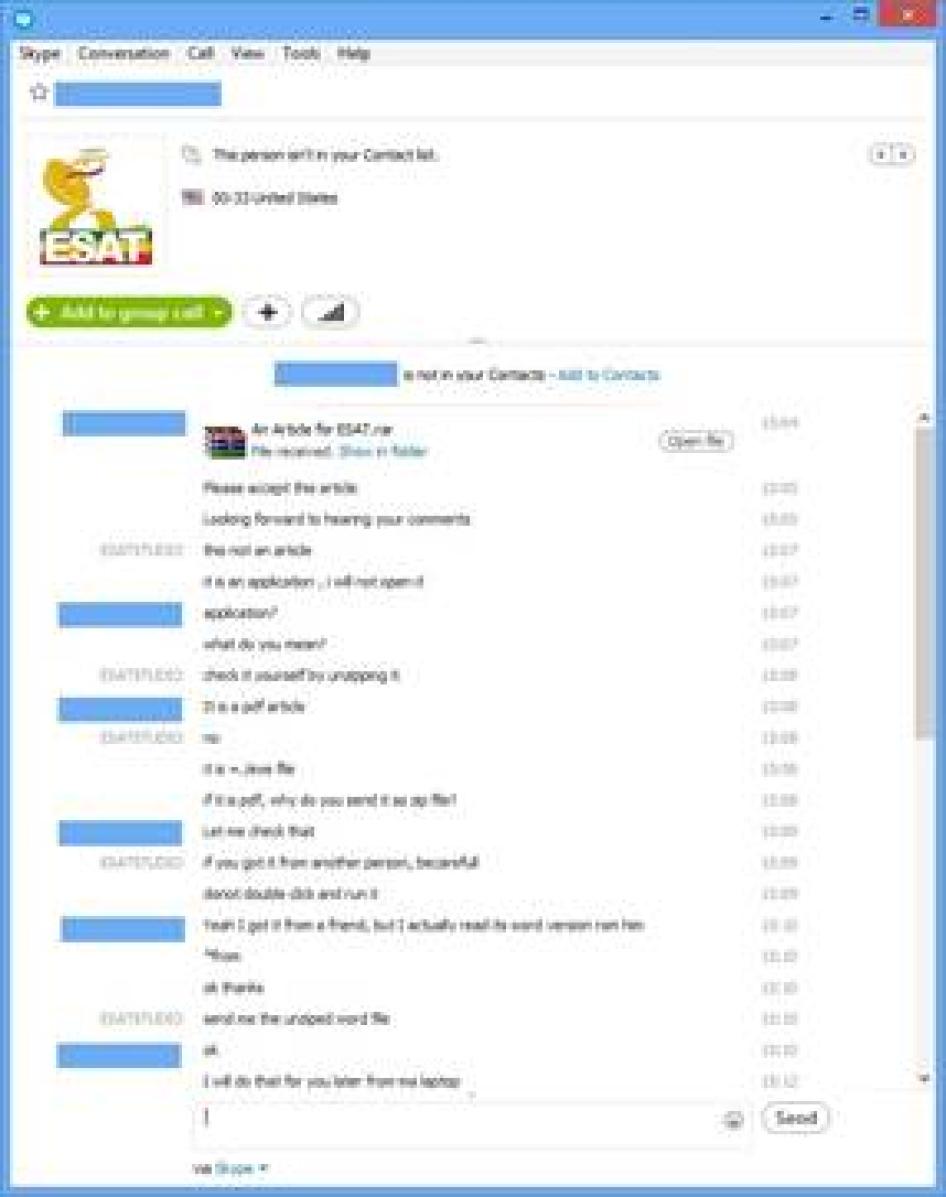

Perhaps the most blatant misuse of the telecom system is the government’s ease of access to historical phone records and recorded calls of Ethio Telecom customers and other metadata.[102] Ethiopian security officials can access the records of all phone calls made inside Ethiopia with few restrictions. Information on all phone calls is stored and easily accessed through Ethio Telecom’s customer management system, ZSmart. ZSmart is a customer management database developed by ZTE and installed for Ethio Telecom to manage all aspects of a customer’s account, from personal information (name, address, even ethnicity) to billing information and detailed listings of phone calls.[103] Phone call information includes the originating and receiving phone numbers, the location of originator/receiver, the time, date and duration of every call.[104] ZSmart also includes the content of SMS text messages and the audio of phone calls received or originating from a selected phone number can be recorded, which can then be easily downloaded and listened to or saved to a USB stick for future use.[105]

While standard, off-the-shelf customer management and billing systems have legitimate purposes, the ease of access by security agencies and lack of procedural or legal constraints, means that the system can be misused in inappropriate ways to access information that should remain private. That the ZSmart system in Ethiopia has been configured to enable access to text messages and full recordings of phone conversations only exacerbates the risk of abuse. ZSmart has been in place since 2009.

Figure 1. Sample screen from Ethio Telecom's ZSmart database. Required fields include name, gender, race, and whether the individual is on a “blacklist.”

All telecom companies globally maintain some level of record keeping of customer phone use for a variety of valid business reasons—otherwise, customer billing would be difficult to track.[106] Crucially, however, capturing a recording of phone calls or the content of text messages is not necessary for these business functions.

Government access to the content of phone calls, text messages, and metadata/call records interferes with the right to privacy. As a result, to ensure such interference is not arbitrary or unlawful, many governments have enacted laws that restrict access to phone records and the circumstances in which calls can be intercepted or recorded. In many countries, it is illegal to record a phone call without a judicial warrant. Security or law enforcement agencies are often required to go through a specified legal process and demonstrate a legitimate aim, under oversight by an independent authority. A legislative framework that regulates access to this information is needed to protect the right to privacy and ensure that access to this information is undertaken in a proportionate and legitimate manner on appropriate targets and only by specified, authorized individuals.

The framework for legal protections of privacy rights in Ethiopia is limited. While laws exist that provide some guidance for surveillance (requiring the issuance of warrants for certain kinds of searches, for example), Human Rights Watch has found no indication of any regulations, directives, or procedures that guide surveillance and intelligence gathering beyond this. Our investigations did not uncover a single case in which there was evidence that warrants were issued by the courts to facilitate access to phone records or recordings.

Former Ethio Telecom and security officials told Human Rights Watch that the lack of defined rules and procedures meant that anybody with appropriate ZSmart database permissions could easily access this information. Former Ethio Telecom employees said that no request for information from NISS had ever been denied as far as they were aware.[107] Federal legislation requires that Ethio Telecom cooperates with NISS when they are requested to provide intercepted information.[108]

In practice, private customer information was accessed by security and intelligence officials in a variety of ways. Federal police officials would typically present letters to Ethio Telecom senior managers for access to certain user information. These letters were not signed by the courts and no rationale or legal justification for the request was ever given. These letters would then be passed on to junior Ethio Telecom officials by senior managers to facilitate the requests. NISS requests for phone records were much more informal: they would either communicate orally to Ethio Telecom employees whom they had established a relationship with to access certain information, or would show up at Ethio Telecom offices to query ZSmart themselves using log-in credentials supplied by Ethio Telecom employees. Ethio Telecom employees, fearful of reprisals from security officials, comply with these requests. NISS does not appear to go through a particular hierarchy or formal process to access customer data or phone call recordings.

Former Ethio Telecom employees also explained that the process for selecting targets of surveillance was often similarly informal. Authorities would provide specific telephone numbers to select for the recording of phone calls through the ZSmart system. Once a number is selected for surveillance, all calls made to and from that number would be recorded and accessible through ZSmart. Authorities rarely requested an end to recording of calls once a number was selected for surveillance.[109]

Numerous individuals said that security officials told them that they were being continuously monitored. Those officials would then show them information from their phone records during interrogations. Often security officials were using this information to find out the location of different individuals they were looking for who communicated by phone with the detainee. Other times they wanted to clarify the meaning of the contents of specific phone communications. Several individuals told Human Rights Watch in detail about specific information gleaned from recorded phone calls that security officials revealed during interrogations.

One member of the Oromo National Congress, a registered Oromia-based political party, who was tortured in detention, describes his 2010 arrest:

After some time I got arrested and detained. They had a list of people I had spoken with. They said to me, “You called person x and you spoke about y.” They showed me the list—there were three pages of contacts—it had the time and date, phone number, my name, and the name of the person I was talking with. “All your activities are monitored with government. We even record your voice so you cannot deny. We even know you sent an email to an OLF [Oromo Liberation Front] member.” I said nothing. “I have a right to be a party member, I have a right to contact ONC. This is not a crime.” I refused to acknowledge I was OLF because I am not. They put me in cold water and applied electric wire onto my feet, they plugged the wire into the wall. They wanted me to admit that different people I had called were OLF and I told them I do not know if they are or not, which was true. They played one call with an Oromo where I said, “How are we going to meet?” “That means you are planning something” is what they told me. That was not a crime, they were a member of my party—I needed to speak with them.[110]

An Oromo artist who wrote about political issues was charged under the Criminal Code after being accused of being a member of the OLF along with several dozen other people.[111] She described her interrogation in Makalawi prison in Addis Ababa:

I was presented a six-page list of phone calls. They had calls highlighted and asked me specific questions about those calls. They also had my email address and showed me it but I denied that I had an account. They put a gag in my mouth and tied my hands behind my back to the chair I was sitting on. They said, “You spoke with somebody called [Oromo name] at time x from place y.” Many of these calls were to people in Moyale.[112] They told me to confess I was OLF. They pushed me on this every night for one month.… When I wouldn’t confess they kept going back to my list of calls, and wanted to know who different people were. They played several phone calls I had with friends demanding to know what I meant when I said different things. I had nothing to tell them, we were just arranging to meet up. They kept telling me, “All your activities are monitored.”[113]