Branded for Life

Florida’s Prosecution of Children as Adults under its “Direct File” Statute

Summary

Oliver B. was prosecuted in adult court in Florida when he was 16 for stealing two laptops from a high school classroom. Matthew N., also 17, was prosecuted in adult court for stealing a printer from the back porch of a house. The experiences of Oliver and Matthew—removed from the juvenile justice system as teenagers and tried in adult court for nonviolent crimes—are far from unique.

Florida transfers more children out of the juvenile system and into adult court than any other state. In the last five years alone, more than 12,000 juvenile crime suspects in Florida were transferred to the adult court system. New statistics developed by Human Rights Watch based on official Florida state data show that more than 60 percent of the juveniles Florida transferred to adult court during this period were charged with nonviolent felonies. Only 2.7 percent were prosecuted for murder.

Whether a particular youth accused of a particular crime in Florida ends up in adult court is in an important sense arbitrary. The new data show that nearly 98 percent of the juveniles in adult court in Florida end up there pursuant to the state’s “direct file” statute, which gives prosecutors unfettered discretion to move a wide range of juvenile cases to adult court (including any 16- and 17-year-old accused of a felony), with no involvement by a judge whatsoever. The data show that this discretion is being exercised differently by prosecutors in different judicial circuits within Florida. Too often, as detailed below, the same crime is treated differently depending on the predilections of the prosecutor where the crime occurs: different judicial circuit, different outcome. And there is evidence that racial bias is affecting that exercise of discretion with respect to certain crimes.

Most states in the United States do not allow for direct file. International law requires that children, including those accused of crimes, be treated as children. And for good reason. Neuroscience, recent US Supreme Court decisions, and a by-now large and growing literature show that children, including 16- and 17-year-old juveniles, are different and in important respects less culpable than adults who commit the same crimes, and more amenable to rehabilitation, a key objective that the juvenile system is designed to achieve. At present, however, while teens 17 and under cannot legally vote, drink, or buy cigarettes in Florida, they can be branded as felons for life.

Florida’s direct file law is a remnant of the “super-predator” panic of the late 1980s, the fear that America was becoming prey to a new generation of particularly depraved and violent teenagers. The panic was born of an overreaction to a nationwide spike in juvenile crime that has long since abated. Even the professor who coined the term now acknowledges that the super-predator prediction “was never fulfilled.”

Florida’s direct file law is not effectively serving public safety. Indeed, recent studies link transfers of juveniles to adult court to increases, not decreases, in recidivism. And, as this report shows, “direct file” is having negative, at times devastating, effects on the lives of thousands of children and their families.

Human Rights Watch spoke to over 100 youth and family members of youth charged directly in adult court by Florida’s prosecutors. Young people described feeling confused and abandoned once in adult court. Many encountered violence upon entering adult jails and prisons. In nearly every case documented in this report, they pled guilty to felonies that will mark them forever without having a full understanding of the repercussions. Some of them were unable, even months and years after entering their guilty pleas, to explain the process that resulted in their criminal convictions.

Florida should reverse course and adopt an approach grounded more firmly in fact and reason. Florida’s legislature should start by eliminating “direct file” and instead require that all decisions to transfer juveniles to adult court be made by a judge after a hearing, with a strong presumption that all children 17 and under should remain in the juvenile system.

* * *

I felt like my life was gone.

—John C., prosecuted as an adult at age 16, May 29, 2013

Many people know that children in Florida can be tried as adults for serious crimes of violence. Lionel Tate made headlines in 2001 when, at age 12, he was convicted and sentenced to life in prison without parole for the killing of a 6-year-old neighbor. Far less widely appreciated is that Tate represents a tiny minority: far more common are cases—like Oliver’s and Matthew’s—in which Florida children are tried in adult court for nonviolent crimes. Of the 1,535 children tried in adult court in Florida in 2012-13, 865 had been accused of committing nonviolent felonies; another 54 were sent to adult court to face misdemeanor or other non-felony charges.

As noted above, roughly 98 percent (98.3 percent in 2012-13) of juvenile cases transferred to adult criminal court in Florida in recent years ended up there pursuant to the state’s direct file statute. The statute gives prosecutors unfettered discretion to charge 16- and 17-year-olds accused of any felony in adult court and to charge 14- and 15-year-olds as adults with respect to certain specific felonies.

None of the children prosecuted under Florida’s direct file statute have the benefit of hearings where they can challenge the decision to transfer them to the adult system before an impartial decision-maker. The statute does not give judges any role to play in the decision to pursue direct file; a juvenile court judge cannot stop a prosecutor from charging a child in adult court, and an adult court judge has no power to refuse to hear a case and send it to juvenile court, regardless of how unsuitable the case is for criminal court. Florida fails to provide even the most basic of safeguards—a fair hearing —when determining the fate of its children.

Rather than being prosecuted in the juvenile system, which is intended to be rehabilitative and to balance the needs of society and the best interests of the child, such children are shunted off to the adult criminal justice system, which values punishment over everything else. They are placed in adult jails, deprived of age-appropriate programs, and subjected to harsh sentences and the life-altering consequences of adult felony convictions.

Many teens find out they are going to be tried as adults only when they are taken from juvenile detention to an adult jail, where many become victims of and witnesses to violence. Some go through the entire adult court process—from arrest and bond hearing to guilty plea—without fully understanding what is happening.

The decision to deny a child access to the rehabilitative services offered by the juvenile justice system and subject him or her to the more punitive adult system is, in most cases, made by the prosecutor, who is an adverse party in the proceedings and has no obligation to consider the defendant’s status as a child. While Florida’s still on-the-books but rarely used judicial waiver statute sets out eight factors, including “the likelihood of reasonable rehabilitation of the child,” that a judge is required to consider before ordering transfer to adult court, the direct file statute empowering prosecutors contains no such factors. Prosecutors are not even required to state why they are choosing to charge a child in adult court. Their decision is final and cannot be challenged.

As noted above, new statistics developed by Human Rights Watch for this report show that the overwhelming power Florida has handed to prosecutors is playing out in arbitrary and unjust ways. Florida’s judicial circuits send arrested children to adult courts at vastly different rates. This variation cannot be explained by the seriousness of offenses, the size of circuit youth populations, or other data Human Rights Watch examined. Even more disturbingly, once children are charged in adult court, some Florida circuits impose severe adult penalties at frequencies that are out of proportion to the levels of youth crime in those circuits.

Statewide, Florida is also treating its black male youth more harshly than their white counterparts. Black boys make up 27.2 percent of children arrested for crime, but account for 51.4 percent of youth sent to adult court; whereas white boys make up 28 percent of children arrested and account for only 24.4 percent of youth tried in adult court. A simple explanation might be that the crimes of black boys are more serious than those of white boys; Human Rights Watch looked into transfer rates for different categories of crime in an effort to find out. While for some crimes the transfer rates are similar, for others there is a marked disparity, particularly in certain judicial circuits. The 13th Circuit, for example, transferred 8.8 percent of white youths arrested for drug felonies to adult court; for black youth arrested for the same crimes, that figure was 30.1 percent, more than three times higher. The available data do not include important details of the cases that may partly account for the disparities, including the drug quantities involved and the criminal histories of the offenders, but the consistency and size of the racial disparities nonetheless are of serious concern.

The racial disparities and the variations between circuits are disturbing evidence of the unchecked discretion of Florida’s prosecutors. They are also problematic because the youth charged in Florida’s adult courts suffer extraordinarily severe consequences. Nearly every child charged and convicted in adult court ends up with an adult felony record that will haunt him or her for life. Many will serve time in Florida’s adult prisons. Even those who are charged in adult court but ultimately have their cases dismissed discover that their adult arrest records haunt them when they apply for jobs or housing. The permanent consequences of a felony conviction or a felony arrest record are difficult for any person to live with, but this is particularly so for a child. Those with convictions are barred by law from many types of employment, and suffer many other deprivations, including permanent loss of the right to vote.

The broad discretion the direct file statute gives prosecutors also has a corrupting effect on the juvenile system—Human Rights Watch learned that prosecutors in some jurisdictions are using the threat of direct file in order to obtain guilty pleas in juvenile court, thereby discouraging defendants from exercising their right to present a defense and avoid incarceration in juvenile facilities.

Once they are charged directly in adult court by Florida’s prosecutors, children are moved to adult jails pending disposition of their cases, and often serve their sentences in adult facilities. While Florida law requires that they be kept separate from adults, the experience of adult jail or prison is still traumatic. Many interviewees reported that violence was prevalent in adult jails and prisons. Furthermore, adult facilities are simply not designed to house children—interviewees suffered from inadequate time outdoors, a lack of appropriate counseling, and were prevented from visiting privately in person with their families (some were instead limited to video phone calls with their loved ones). They also noted that corrections officers lacked the skills or patience required to deal with adolescents. Additionally, the long distances between the prisons that housed them and their hometowns meant that family visits were rare.

The US Supreme Court, in a series of four recent cases, has underscored what every adult knows—that children are different. Their bodies, personalities, and brains are in the process of maturing, which means they are uniquely suited to the rehabilitative programs offered in the juvenile justice system. Although they can be held accountable for crimes, their punishment should take into account their diminished culpability, because they are less able to reason logically, to withstand peer pressure, to predict future outcomes in order to guide their behavior, and to make careful decisions. This extends to 16- and 17-year-olds. One judge who has presided over juvenile court for 14 years told Human Rights Watch, “I’ve been here long enough to understand that when someone is 16 and I ask them why they did it and they say ‘I don’t know,’ I believe them.”

This understanding is also reflected in international law, which has long recognized that children are fundamentally different from adults. International law requires that children receive special protection in all proceedings, including criminal proceedings. To comply with international standards, any criminal process that a child is subjected to must take into account the fact that children are uniquely capable of rehabilitation.

Some children are charged directly in adult court for their first offense. Others are subjected to direct file after a series of offenses adjudicated in juvenile court. In neither case is the unfettered power of prosecutors to charge them as adults warranted. Irrespective of any prior offenses, international human rights law requires that children receive treatment tailored to their development and well-being until they reach the age of 18. Even repeat offenders are entitled to that basic safeguard. There are practical reasons for exempting children from adult procedures and sanctions as well. Research shows that criminal behaviors peak in the teenage years, then decline rapidly and continue to slowly decline in late adulthood.

Florida should stop shunting children off to adult court to face processes they do not understand, to spend time in adult facilities not suited to children, and to serve adult sentences that bring a lifetime of consequences that they cannot fully grasp. Florida should re-examine its decision to give prosecutors sole authority to take children away from the juvenile system, where their parents can continue to play a role in their lives, in favor of placing them in the adult system, where parents have very little power and extremely limited contact with their children. The victims of crimes committed by children deserve justice, but children, including teens, can be held accountable without subjecting them to treatment as harsh as that meted out by the state of Florida.

Recommendations

To the Florida Legislature

- Repeal statutory authorization for direct file and instead require that all decisions to transfer children (youth 17 and under) to the adult system be made by a judge based on testimony and evidence presented in a hearing, with a statutory presumption that they remain in the juvenile system. The hearing should include consideration of the juvenile’s amenability to rehabilitation.

- To the extent youth 17 and under continue to be prosecuted in adult court, stop their pretrial confinement in adult jails and instead allow them to remain in the custody of the Department of Juvenile Justice.

- Make sealing or expungement of criminal records automatic upon completion of sentence for crimes committed by people 17 and under.

To Elected State Attorneys

- Until direct file is eliminated, apply the discretion conferred on prosecutors by Florida law to stop the practice of direct file.

- To ensure that prosecutions are conducted in a way that takes into account the specific characteristics of children and the desirability of promoting their rehabilitation, create specialized units of prosecutors tasked with prosecuting all cases in which the suspect is 17 or younger at the time of the offense.

- Provide training to all attorneys prosecuting juveniles in Florida in how to deal with juveniles, including information about adolescent brain development.

To Juvenile Court Judges

- Until direct file is eliminated, order state attorneys to indicate their intent to directly charge a juvenile in adult court at least 5 days prior to filing the case in adult court in order to give defense attorneys an opportunity to explain the procedure to their juvenile clients in a manner that the clients can comprehend.

- Until direct file is eliminated, provide an on-the-record explanation to children subject to possible direct file of what it is and what to expect if they go to adult court.

- Once direct file is eliminated, provide an on-the-record explanation to children subject to possible judicial waiver hearings of what those hearings entail and what to expect if they go to adult court.

To Circuit Court Judges

- Exercise all possible discretion to allow children charged as adults to remain in the community, or in the custody of the juvenile justice system if custody is required, rather than in adult jail pending trial.

- Tailor criminal procedures to children’s capacity to understand as well as to their needs and rehabilitative potential.

- When sentencing children convicted as adults, take into account the child’s developmental status and capacity for rehabilitation.

To the Office of Court Administration

- Require all judges who preside over criminal cases to attend trainings in adolescent brain development and in how to address the needs of children tried as adults.

To Public Defenders

- Require all lawyers to attend trainings in adolescent brain development and in how to work with juvenile clients.

- Create specialized units to handle cases of children subject to the jurisdiction of adult courts so that felony lawyers can develop expertise in dealing with juvenile clients.

To the Department of Juvenile Justice

- Collect and make publicly available data on the disposition of cases where defendants are prosecuted in adult court for crimes committed while 17 or younger.

- Collect data on how often cases that are considered for direct file result in guilty pleas in juvenile court.

- Use all power and authority available to the agency to limit the number of youth held in adult facilities or tried in adult courts.

To the Department of Corrections

- Require all probation officers to attend trainings in adolescent brain development and in how to interact with children convicted of crimes.

Methodology

This report is based on interviews and correspondence with 107 individuals and relatives of individuals who were sent directly to adult court by Florida’s prosecutors, pursuant to Florida’s direct file statute, for crimes committed when they were 17 or younger. Human Rights Watch interviewed 42 of the 107 in person and three via phone. Of the people we interviewed in person, 23 were incarcerated at the time we spoke with them. We corresponded with the 62 remaining persons.

Human Rights Watch identified individuals prosecuted in adult court by searching the Florida Department of Corrections offender database, available at http://www.dc.state.fl.us/pub/obis_request.html. Human Rights Watch sent a letter and survey, the templates of which are included in Appendix A of this report, to 656 incarcerated individuals and probationers whose dates of offense and dates of birth indicated that they were likely prosecuted in adult court for offenses committed prior to age 18. The letters asked people to respond only if their cases had been filed in adult court by a prosecutor, rather than transferred there by a judge or after indictment by a grand jury. Several child advocates and defense attorneys also distributed the surveys to an unknown number of children they knew to have been sent directly to adult court by a Florida prosecutor.

Of the people who received surveys, 75 responded. Of those 75, Human Rights Watch was able to interview 11 in person. Nine of those were incarcerated at Sumter Correctional Institution when they spoke to Human Rights Watch. Human Rights Watch interviewed two additional people at Sumter who had not filled out surveys. At the time Human Rights Watch was conducting interviews, Sumter and Lancaster Correctional Institution were the two Florida prisons with the highest number of inmates aged 17 or younger. Lancaster authorities refused to give Human Rights Watch access to any incarcerated individuals. While the prison administration at Sumter did allow Human Rights Watch to conduct interviews at the facility, they would not allow interviews with any incarcerated people who were in solitary confinement. Ten incarcerated youth who responded to the Human Rights Watch survey were in solitary confinement on the days interviews were conducted, and were thus unavailable.

Four other survey respondents we interviewed were being held under house arrest, were on probation, or had completed their sentences. Of these, we interviewed three in their homes and one at a coffee shop.

Two individuals we interviewed came to our attention after their stories appeared in the media. We interviewed one at her place of business, the other by telephone. Finally, 13 children who were represented by the Ninth Judicial Circuit Office of the Public Defender and incarcerated at the Orange County Jail agreed to speak to Human Rights Watch but had not completed written surveys.

Human Rights Watch also spoke to 42 prosecutors, judges, defense attorneys, child advocates, and juvenile system probation officers who had been involved in cases prosecuted under Florida’s direct file statute. Human Rights Watch attempted to speak to adult system probation officers, repeatedly contacting several regional probation offices as well as the Florida Department of Corrections, which oversees adult felony probation, in an effort to speak to adult system probation officers who had supervised youth who had been subject to Florida’s direct file statute. We received no response.

This report focuses on Florida because it was among the first states to give prosecutors, rather than judges, the discretion to decide when a child should be charged as an adult. Historically, Florida has charged children as adults at a higher rate than other states. Thirteen US states report the rate at which children are removed from the juvenile system and prosecuted in the adult criminal system. Of these 13 states, Florida charged children as adults at a rate of 164.7 per 100,000 juveniles from 2003-2008, almost twice the rate of Oregon, which came in second.

In this report, in line with international law, the terms “child” and “children” refer to a person or persons below the age of 18. We use the term “young person” to refer to those who were older than 18 at the time of their interviews or correspondence with Human Rights Watch but had been prosecuted in adult criminal courts for crimes they committed as children. “Transfer” refers to the practice of removing a child from juvenile court jurisdiction and prosecuting him or her in adult court, regardless of whether the child gets to the adult system through direct file, judicial waiver, or some other process. Finally, in this report, we use the phrase “charged directly in adult court” as a shorthand for “charged in adult court pursuant to Florida’s direct file statute.”

Florida comprises 67 counties, which are organized into 20 judicial circuits. Each circuit organizes its own criminal and juvenile courts, and has an elected state attorney, or prosecutor, and an elected public defender. Human Rights Watch was not able to interview people in every county or circuit. In selecting which jurisdictions to visit, we focused on those circuits with the highest rates of juveniles prosecuted in adult court, but also aimed to include both densely and sparsely populated circuits.

All individuals we interviewed about their experience provided informed consent to participate in the research. Interviews at Sumter Correctional Institution and the Orange County Jail were conducted in private, outside of the hearing of jail and prison staff. An attorney from the Ninth Circuit Public Defender’s Office was present for the interviews conducted in Orange County Jail, since the majority of the children interviewed there had pending cases and were advised not to speak without their lawyer present. We explained to each interviewee that participation in the interview was completely voluntary, that we could not offer any legal advice or other assistance, and that the interviewee could stop the interview at any time. We gave no incentives to interviewees. One individual declined to be interviewed. We ended a second interview shortly after it began when the child being interviewed gave indications that he did not understand what was happening or what the purpose of the interview was.

All interviewees were given the choice of using their real names or a pseudonym. Due to the serious stigma of arrest and conviction, and the possibility that at least some of the children and young people interviewed might not know if their cases could be eligible for sealing, expungement, or pardon in the future, we decided to use pseudonyms for all of the children and young people interviewed except for two: Kiera Wilmot and Veronica Limia. Kiera’s arrest received national media coverage. She and her mother both agreed that her name could be used in this report. Veronica Limia, who was prosecuted directly in adult court at age 17, is now 31 years old and an attorney. Her law school graduation, as well as her background as a child in the criminal system, have been covered in local newspapers, and she gave consent to use her name in this report.

The statistics in this report are all based on data provided by Florida’s Department of Juvenile Justice (DJJ).

In April 2013, Human Rights Watch sent freedom of information requests to state attorneys in all 20 Florida circuits, requesting individual record data for all juveniles charged directly by prosecutors in their adult courts from 2007 until April 2013. State attorneys for the following judicial circuits provided the requested information: 1st Judicial Circuit, 4th Judicial Circuit, 6th Judicial Circuit, 7th Judicial Circuit, 8th Judicial Circuit, 9th Judicial Circuit, 12th Judicial Circuit, and 18th Judicial Circuit. State attorneys for the following judicial circuits claimed that they had no responsive records or were not obligated to provide them by Florida’s public records law: 3rd Judicial Circuit, 6th Judicial Circuit, 11th Judicial Circuit, and 13th Judicial Circuit. State attorneys for the following judicial circuits had not responded to Human Rights Watch’s request by the time of this writing: 14th Judicial Circuit, 15th Judicial Circuit, 16th Judicial Circuit, 17th Judicial Circuit, 19th Judicial Circuit, and 20th Judicial Circuit. State attorneys for the following circuits had indicated an intention to provide the requested information, but had not provided it by the time of this writing: 2nd Judicial Circuit, 5th Judicial Circuit, and 10th Judicial Circuit.

Because some responsive circuits provided individual record level data as per our original request, whereas others provided aggregated data, Human Rights Watch was not able to use that data to compare between circuits. Accordingly, we have relied on the data provided by the DJJ.

Finally, Human Rights Watch asked Florida’s Office of Court Administration (OCA) for data on youth charged directly in adult court by Florida’s prosecutors. The OCA made several attempts to provide responsive data, but their data did not include information on whether individuals were transferred from juvenile court or their ages at the time of offense, making it impossible to extract the information sought by Human Rights Watch.

I. Background

Juvenile Courts in the United States

Since the founding of the world’s first juvenile court in Illinois in the 1890s, legal systems in the United States have recognized that children are different from adults and should be treated differently.[1] While criminal justice has traditionally been understood to achieve four goals—retribution, incapacitation, deterrence, and rehabilitation—adult criminal courts in the United States have become increasingly focused on retribution and incapacitation. Juvenile courts, on the other hand, have always prioritized rehabilitation.[2]

Almost every juvenile court system in the United States has had, since its inception, some form of judicial waiver procedure, whereby a judge could determine when a juvenile should be transferred to adult court.[3] Prior to the 1980s, and consistent with the preference for treating children in the juvenile court, such waivers were rarely used.[4] Beginning in the 1980s, however, at least in part in response to an increase in juvenile crime, nearly every US state made it easier to transfer children from juvenile courts to more punitive adult courts.[5]

The national trend to transfer more juveniles to adult court came at a time when the United States was experiencing a steep escalation in crime rates, including rates of violent crime by adolescents.[6] Politicians and pundits warned about an oncoming wave of adolescent “super-predators,” a term coined by then-Princeton Professor John DiIulio, and deployed in a highly racialized narrative.[7] In a 1995 article, DiIulio warned that “Americans are sitting atop a demographic crime bomb” and predicted that the following decade would “unleash an army of young male predatory street criminals who will make even the leaders of the Bloods and Crips—known as O.G.s, for ‘original gangsters’—look tame by comparison[.]”[8] Youth of color were overrepresented in media portrayals of crime during this period.[9]

The spike in juvenile crime actually had already peaked when DiIulio wrote those words. The apex came in 1994, by which point the violent crime index[10] arrest rate for juveniles had increased over 68 percent from its 1980 level.[11] By 2010, the violent crime index arrest rate for juveniles had plummeted to well below the 1980 level.[12] In 2012, the juvenile violent crime arrest rate hit a 32-year low.[13] DiIulio himself has acknowledged that his dire predictions were wrong, and now advocates for programs and prevention over incarceration.[14] In 2012, he was a signatory to an amicus brief in Miller v. Alabama, the Supreme Court case challenging juvenile life without parole sentences. The brief stated,

The prediction of a juvenile superpredator epidemic turned out to be wrong; in fact, there was no superpredator generation. Professor DiIulio, the original proponent of the juvenile superpredator notion and a signatory to this brief, has repudiated the idea and “expressed regret, acknowledging that the prediction was never fulfilled.”[15]

While there has been some softening of the transfer laws passed in the wake of the “super-predator” hype,[16] many of the most punitive laws remain on the books,[17] despite that fact that transfer to adult court has been linked to an increase in recidivism.[18]

Research has shown the ineffectiveness of punishing children, including teens, as adults in order to deter future crime. A 2007 study by the Centers for Disease Control found that “evidence indicates that transfer to the adult criminal justice system typically increases rather than decreases rates of violence among transferred youth.”[19] A Department of Justice analysis of all transfer studies conducted as of 2010 determined that none had proven that juvenile transfer laws were an effective deterrent to crime.[20] Florida-specific studies have come to the same conclusions. One 2002 study compared 475 youth charged in adult court with 475 youth who remained in the juvenile system and found that “nearly 50 percent of the transfers re-offended after age 18 but only 35 percent of the juvenile cases did[,]” even though the youth charged as adults were similar in age, gender, race, prior record, and seriousness of offense.[21] Further, the transferred juveniles who re-offended were more likely to commit more serious felonies than the non-transferred juveniles.[22]

Shay Bilchik, who served as an assistant toFlorida Attorney General Janet Reno during the height of the state’s use of direct file in the 1990s later acknowledged that “‘[k]ids prosecuted as adults tend to re-offend more quickly, they re-offend for more serious offenses, and they tend to re-offend more often.” Those results, he said, were “the trifecta of bad crime policy.’”[23]

Prosecutorial Direct File: The National Context

Every state has at least one mechanism that allows for the transfer of children to adult court. Most states use judicial waiver, where a judge presides over a hearing to determine whether it is appropriate to remove a child from the jurisdiction of the juvenile court and prosecute him or her in adult court.[24] Both the prosecution and the defense have the right to be heard at a waiver hearing, and the presiding judge considers several factors, including the child’s amenability to rehabilitation, before deciding whether to send a child to adult court for prosecution.[25]

In Florida, the statute governing waiver hearings requires the juvenile court judge to consider factors including the seriousness of the offense, the child’s prior record, and the child’s amenability to rehabilitation before deciding to transfer that child to adult court.[26] At the hearing, the judge will hear from the defense attorney, the Department of Juvenile Justice, the child’s parents or guardians, and the child herself, as well as the state attorney.[27] If the judge decides to transfer the child, that decision must be in writing and can be appealed.[28]

Fifteen states and the District of Columbia also give prosecutors the option, through a process called direct file, to charge juveniles directly in adult court, removing them from the jurisdiction of the juvenile court and thus from further involvement by juvenile court judges in decisions to charge juvenile suspects in adult court.[29] Some of these states, including Florida, also have mandatory provisions requiring the prosecutor to charge certain cases directly in adult court.[30]

Under direct file laws, the prosecutor’s decision is generally made without any oversight from either the juvenile court or the adult criminal court. In nearly all states with direct file laws, the statutes do not provide guidance as to what factors prosecutors should consider in making the decision to charge a child directly in adult court. Even in the few states that provide guidance to prosecutors, there is no way to ensure that the guidance is being followed, as there is often no record of the decision or opportunity to challenge it. Indeed, in the view of the US Department of Justice, “it is possible that prosecutorial discretion laws in some places operate like statutory exclusions, sweeping whole categories into criminal court with little or no individualized consideration.”[31]

Ten jurisdictions, including Florida, give prosecutors discretion to charge a 14-year-old in adult criminal court for some offenses.[32] In Montana, a prosecutor can charge a 12-year-old in criminal court for certain personal offenses. In Nebraska, there is no age limit for certain felonies. In Florida, Nebraska, and Vermont, a prosecutor may choose to prosecute any juvenile starting at age 16 for any felony. In Wyoming, that age drops to 13.[33] Florida even permits youth accused of misdemeanors to be charged as adults under certain circumstances.[34] This patchwork of direct file laws means that a juvenile’s chances of facing such charges, and of facing them without judicial oversight, depend a great deal on where the child happened to commit her crime.

Florida: At the Forefront of Treating Children as Adults

Currently, Florida ostensibly has three mechanisms for transferring children from juvenile to adult court. Two of them, judicial waiver[35] and indictment, which requires a prosecutor to present a case to a grand jury before moving forward with it in criminal court,[36] account for less than 2 percent of cases of children prosecuted in adult court. The third, prosecutorial direct file, which gives prosecutors discretion to file charges in adult court, accounts for approximately 98 percent of cases and is the subject of this report.[37]

Florida has one of the harshest prosecutorial direct file laws in the United States[38] and has transferred more children out of the juvenile and into the adult system than any other state.[39] From 2003 to 2008, Florida transferred youth to adult court at 1.7 times the rate of Oregon, the state with the second-highest transfer rate, and 2 times the rate of Arizona, the state with the third-highest transfer rate.[40] During that period, Florida’s transfer rate was 8 times the rate of California and 5 times the average transfer rate in 12 other states.[41] Florida’s direct file statute is also one of the oldest in the United States—the Florida legislature passed the state’s first direct file law in 1978.[42]

Florida’s Direct File Statute

Florida’s direct file statute is complex—it has both discretionary and mandatory provisions, and whether a particular case is eligible for direct file depends on the child’s age, charges, and prior history. At its core, however, it allows for a breathtakingly broad array of cases to be brought in adult court at the sole discretion of the prosecutor and without judicial review. The following three cases illustrate this range.

On the morning of April 22, 2013, 16-year-old honor student Kiera Wilmot decided to see what would happen if she mixed a household cleaner and some aluminum foil in a plastic bottle.[43] She conducted her experiment on the grounds of Bartow High School before classes had started.[44] The result? The bottle top popped off, there was some smoke, and Kiera was arrested and charged with “making, possessing, throwing, projecting, placing, or discharging any destructive device,” a felony charge that can be brought in adult court as long as the defendant is 14 or older.[45] Fortunately, Kiera was not immediately charged in adult court (because she was 16, the prosecutor could have done so under Florida’s direct file law) and, after months of public outrage over what many saw as an unjust prosecution,[46] Kiera was permitted to accept a plea to a diversion program in juvenile court.[47] She is relieved to not have an adult felony conviction, but the time between her arrest and the plea was challenging. Her lawyer told her that she was could face up to 10 years in prison if convicted. She had never been in trouble before, and the possibility of incarceration frightened her.[48]

On March 6, 2012, Oliver B. was arrested at his high school, together with two other boys, for breaking into an empty office at the school a week earlier and stealing two laptops, a blackberry, a Palm Pilot, and $8 in cash. Oliver was offered a sentence of 18 months in a residential facility if he pled guilty to juvenile charges. If he turned down the plea, his lawyer warned him, his case would likely be charged directly in adult court, where he could face up to 15 years in prison. Oliver had been in trouble before, for possession of some stolen calculators. In that case, he had pled guilty and been sentenced to juvenile probation. Oliver’s public defender in the high school theft case “pleaded with [him]” to accept the offer and avoid a conviction in adult court, but Oliver maintained his innocence and refused the offer of juvenile sanctions. The prosecutor charged Oliver directly in adult court. Oliver pled guilty and was sentenced to probation.[49]

On December 31, 2009, 16-year-old Kenneth Ray Stephens and two friends stole a gun from a parked car.[50] The following week, Kenneth and a friend were together in a house when two other teenagers in a different room of the house heard a gunshot, then heard Kenneth yell the victim’s name and start to cry.[51] The victim, while badly injured by a gunshot wound to the head, survived.[52] Prosecutors disagreed with Kenneth’s claim that the shooting was accidental, charging him in adult court with attempted murder. It was Kenneth’s first arrest. At the time of his arrest, he was an honor roll student and member of the football team. No judge had the power to review the decision to charge Kenneth in adult court. Facing a 30-year maximum sentence on the attempted murder charge, Kenneth eventually pled to aggravated assault in exchange for a 15-year sentence. The Florida Department of Corrections has listed his release date as January 2, 2025.

Under Florida’s direct file statute, prosecutors had

discretion to charge Kiera, Matthew, and Kenneth directly in adult court

without any judicial review of the appropriateness of adult court.

Initially introduced in 1978, Florida’s legislators expanded the reach of the direct file statute several times during the 1990s.[53] Florida’s current direct file law has both discretionary and mandatory provisions. The discretionary provision allows prosecutors to file charges directly against any child aged 16 or older in adult court “when in the state attorney’s judgment and discretion the public interest requires that adult sanctions be considered or imposed.”[54] Children 16 or older charged with a misdemeanor may also be tried in adult court if they have had 2 prior delinquency adjudications or adjudications withheld,[55] at least one of which was for an act that would be considered a felony in adult criminal court. It also allows prosecutors to directly charge 14- and 15-year-olds in adult court for any of 19 enumerated felonies—California is the only state with a longer list of felonies that make a 14-year-old eligible for adult court.[56] In none of these “discretionary” provisions does the statute provide guidance or set forth limitations on the prosecutor’s power.

The mandatory provision outlines four circumstances in which a prosecutor “shall” direct file a child: (1) any 16- or 17-year-old who is charged with a violent crime against a person[57] and who was previously adjudicated, or found guilty,[58] of “ the commission of, attempt to commit, or conspiracy to commit murder, sexual battery, armed or strong-armed robbery, carjacking, home-invasion robbery, aggravated battery, or aggravated assault[;]”(2) any 16- or 17-year-old charged with a forcible felony[59] who has three prior felony adjudications in juvenile court;[60] (3) any child of any age who is accused of any crime involving theft of a motor vehicle “and while the child was in possession of the stolen motor vehicle the child caused serious bodily injury to or the death of a person who was not involved in the underlying offense[;]” and (4) any 16- or 17-year-old who is charged with committing certain crimes while in possession of a weapon or other destructive device.[61]

Notwithstanding these mandatory provisions, the statute also provides that the prosecutor may at any time keep any case in juvenile court if she “has good cause to believe that exceptional circumstances exist that preclude the just prosecution of the child in adult court.” The statute provides no guidance as to what those exceptional circumstances might be.[62]

Prosecutors must also charge a child in adult court when she was previously charged and sentenced as an adult. Under the “once an adult, always an adult” provision of Florida’s direct file statute, once a child is sentenced as an adult, that child will automatically be tried in adult court for any subsequent offense, no matter how minor.[63] For example, a 15-year-old who steals a car for a joy ride could be charged with grand theft in adult court, since grand theft is one of the 19 enumerated felonies for which 14- and 15-year-olds can be tried as adults. Stealing a car is a third degree felony,[64] punishable by up to five years in prison.[65] If, a year later, that same child steals a bag of chips from a grocery store, any larceny charges brought against her would have to be filed in adult court.[66]

Direct file has almost entirely displaced judicial waiver in Florida, as the data below shows.[67] Human Rights Watch’s interviews for this report bear out the statistics: when asked if he ever requested judicial waiver hearings, one prosecutor responded “why would I?”[68]

Which Children Are Being Prosecuted in Florida’s Adult Courts?

Types of Offenses

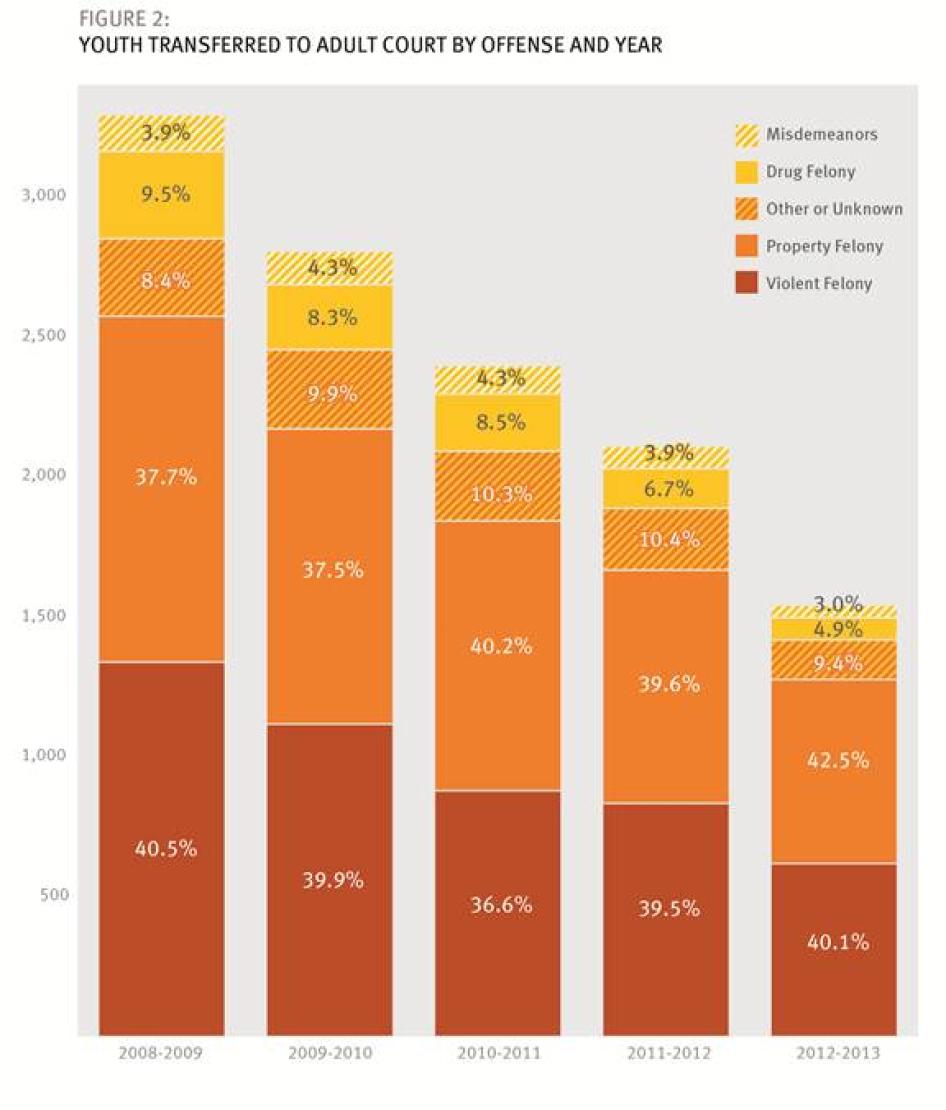

According to new analysis of Florida data conducted by Human Rights Watch for this report, more than 12,000 juveniles were arrested for crime and transferred from Florida’s juvenile justice system to the adult system in the five-year period from fiscal year 2009 to fiscal year 2013, an average of 2,420 juveniles annually. The vast majority of those cases—97.8 percent—reached adult court via direct file. In 2012-13, that figure was 98.3 percent. Thus, while the discussion of data that follows in this section embraces all transfer cases, it is important to recall that the vast majority of those cases are children charged as adults pursuant to Florida’s direct file statute.[69]

Each year, an average of 3.6 percent of juveniles who are arrested in Florida will have their cases transferred to the adult system. While the overall number of transfers has decreased by 53.2 percent over the past five years, this is mainly due to a 40 percent decrease in the overall number of youth entering the juvenile justice system (“juvenile arrests received”) during the same time period. The percentage of juveniles arrested who are prosecuted in the adult system (“juveniles transferred”) has remained steady even as violent crime rates have fallen.

Over the last five years, property felonies and violent felonies each accounted for 39 percent of charges for which youth were sent to adult court. Drug felonies made up 8 percent of transferred offenses, followed by misdemeanors at 4 percent, and “other felonies” at 1.2 percent.[70] Of youth transferred to the adult system between 2008-09 and 2012-13, most were arrested for burglary (27.6 percent) and armed robbery (15.7 percent).

Table 1: Offenses of Transferred Youth (2008-09 - 2012-13)

|

Offense |

% of Total Transfers Accounted by Offense |

|

Burglary |

27.6% |

|

Armed Robbery |

15.7% |

|

Aggravated Assault or Battery |

13.4% |

|

Drug Felony |

8.0% |

|

Weapon Felony |

6.7% |

|

Other Robbery |

5.2% |

|

Misdemeanor Offense |

4.0% |

|

Sexual Battery |

3.1% |

|

Murder |

2.7% |

|

Grand Larceny |

2.3% |

|

Auto Theft |

2.2% |

|

Kidnapping |

1.9% |

|

Other Felonies |

1.2% |

|

Attempted Murder |

1.2% |

|

Non Violent Resisting Arrest |

0.9% |

|

Resist Arrest with Violence |

0.8% |

|

Other Offense (Non-Felony and Non-Misdemeanor) |

0.7% |

|

Felony Sex Offense |

0.7% |

|

Stolen Property |

0.5% |

|

Arson |

0.5% |

|

Fraud |

0.4% |

|

Felony Vandalism |

0.3% |

|

Escape |

0.1% |

The vast majority—93.1 percent—of children charged in adult court are boys. Less than 1 percent of the girls who enter the juvenile justice system are sent to adult court compared with nearly 5 percent of boys. In sheer numbers, there are over 13 times more male youth transferred than females. There are only 2.2 times as many arrests of boys than of girls. We were not able to assess the extent to which the differences in transfer rates for girls were due to the nature of the offenses for which they were arrested or other factors.

Figure 2, below, shows that children are prosecuted in adult court approximately as often for property crimes as they are for violent felonies. In other words, transfer to adult court is not limited to the most heinous crimes. This finding is consistent with a study conducted in Florida in the late 1990s that concluded that the children directly charged in adult court were not consistently the most serious offenders.[71]

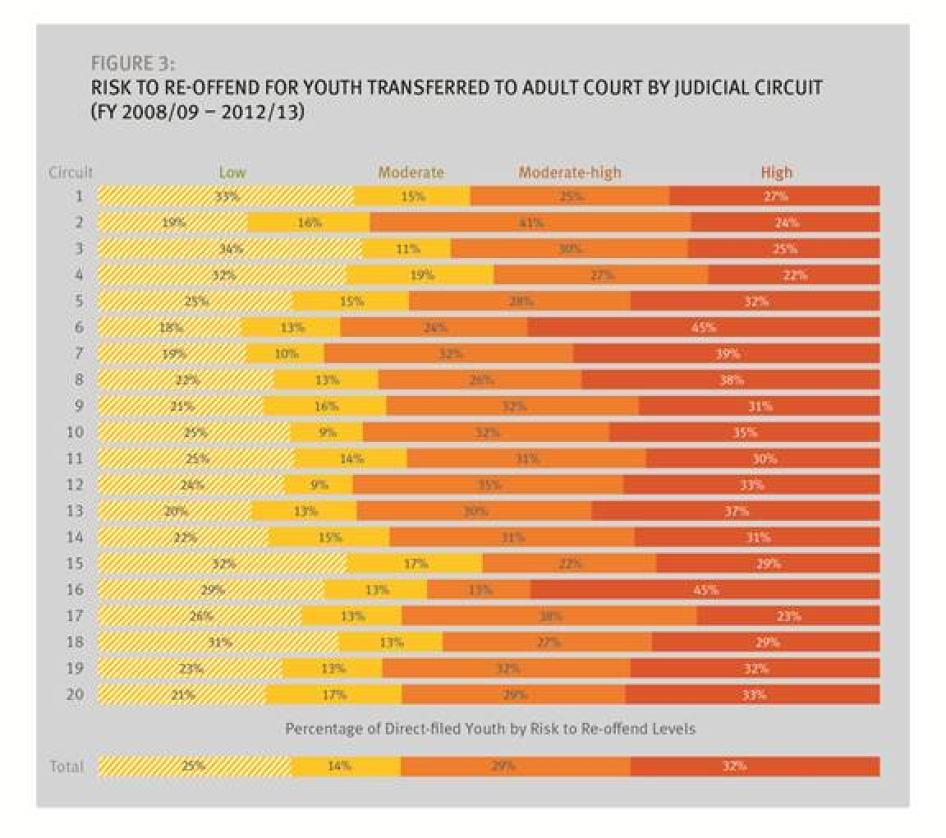

Our analysis further reveals that direct file is also not being reserved for those who are at the highest risk for reoffending according to the Department of Juvenile Justice’s risk assessment tool.[72] Many of those charged directly in adult court by Florida’s prosecutors are not categorized as being at “high” risk to re-offend. In fact, over the five years for which Human Rights Watch was able to obtain data, nearly two of every five youths directly charged in adult court were categorized as being at “low” or “moderate” risk to re-offend. In contrast, less than one-third were categorized as being at “high” risk to re-offend.

According to our analysis, where children directly charged in adult court fall along the risk-to-reoffend continuum varies widely among Florida’s 20 judicial circuits, with prosecutors in some circuits charging far more low-risk children than others. In 5 of the 20 circuits (the 1st, 3rd, 4th, 15th, and 18th), more of the children charged directly as adults were categorized as being at “low” risk to re-offend than as being at “moderate,” “moderate-high,” or “high” risk to reoffend. In 10 of the 20 circuits, by contrast, more were in the “high” risk to re-offend category than in the other categories.

Racial Disparities

Our analysis reveals that black boys make up 27.2 percent of children received by the juvenile justice system (arrested and initially sent for processing to the Department of Juvenile Justice), but account for 51.4 percent of transfers to the adult system. White boys make up 28 percent of children received by the juvenile justice system, but account for only 24.4 percent of transfers.

Table 2: Gender and Race of Arrested and Transferred Youth (FY 2008/09 - 2012/13)

|

Gender/Race |

Percent of Arrested Youth that Are Transferred (within race/gender group) |

Percent of Total Arrested Youth |

Percent of Total Transferred Youth |

|

Black Males |

6.8% |

27.2% |

51.4% |

|

White Males |

3.2% |

28.0% |

24.4% |

|

Hispanic Males |

4.2% |

11.3% |

13.3% |

|

Other Males |

5.8% |

2.6% |

4.1% |

|

Black Females |

0.9% |

12.2% |

3.0% |

|

White Females |

0.7% |

13.5% |

2.8% |

|

Hispanic Females |

0.7% |

4.2% |

0.9% |

|

Other Females |

0.8% |

0.9% |

0.2% |

A simple explanation for this racial disparity might be that the crimes of black boys are more serious than the crimes of white boys. To that end, we analyzed for this report whether black and white youth arrested for similar crimes are transferred to adult court at similar rates. For some crimes, such as murder and property crimes, the transfer rates do seem to be similar (see Appendix B). For others, however, there is a marked disparity. Black boys, for example, are significantly more likely than white boys to be transferred to adult court after being arrested for violent offenses other than murder: from fiscal year 2008 to fiscal year 2013, 13.3 percent of black boys were transferred to adult court whereas only 7.4 percent of white boys were transferred following such arrests.[73]

In the graph below, if black and white arrests were transferred at similar rates, the circuits should be clustered close to (both slightly above and slightly below) the line. Yet, every circuit lies below the line, indicating that each and every circuit in the state transfers black youth arrested for violent felonies at higher rates than white youth arrested for violent felonies.

The graph shows that the 17th Circuit lies closest to the line, indicating that although it transfers black youth arrested for violent felonies to adult courts at higher rates than white youth, the rates are very close to each other. The 16th Circuit lies furthest from the line, indicating the largest racial disparity for violent felony arrest transfer rates.[74]

We found similar racial disparities in drug felony arrests. In the graph below, every circuit lies below the line, indicating that each circuit transfers to adult court black youth that have been arrested for drug felonies at higher rates than white youth arrested for drug felonies. We find the highest disparity in the circuit that transfers the second highest number of drug felony arrests in the state: the 13th Circuit transferred 8.8 percent of white youth arrested for drug felonies and 30.1 percent of black youth arrested for drug felonies.

For both the violent felony and drug felony racial disparity analyses, the available data do not allow us to more closely examine the nature of the offenses (e.g., drug quantities) or criminal histories of the offenders, which may offer some explanation for these disparities.[75] Despite the absence of those details, the consistency and size of these racial disparities are concerning.[76]

II. Do Children Belong in the Adult

Criminal Justice System?

Children are Different

It is axiomatic that children are in the process of growing up, both physically and mentally. Their developing identities make young people, including those convicted of crimes, excellent candidates for rehabilitation: they are far more able than adults to learn new skills, embrace new values, and re-embark on a new, law-abiding life. Justice is best served when these rehabilitative principles, at the core of human rights standards, are also central to the process afforded children accused of breaking the law. The justice system must take into account both the gravity of the charged crime as well as the culpability or blameworthiness of the offender. The question of culpability is part of what separates children from adults. While children can commit acts as violent and deadly as those adults commit, their blameworthiness is different by virtue of their immaturity. Their punishment, and the adjudicative process to which they are subjected, should acknowledge that substantial difference. International law recognizes these differences and expresses a strong preference for using juvenile courts to deal with cases of children accused of breaking the law.[77]

Children may know right from wrong: proponents of transfer provisions for children correctly point out that most children can tell us that it is wrong to steal. But by virtue of their immaturity, children have less developed capacities than adults to control their impulses, to use reason to guide their behavior, and to think about the consequences of their conduct. They are, in short, still “growing up.” Removing children from the juvenile system and placing them into the adult criminal system negates that reality, treating children as though their characters are already irrevocably set.

The Difference According to Psychology and Neuroscience

Psychological research confirms what every adult knows: children, including teenagers, act more irrationally and immaturely than adults. Psychologists have long attributed the differences between adults and children to either cognitive or psychosocial differences. Cognitive theories suggest that children simply think differently than adults, while psychosocial explanations propose that children lack social and emotional capabilities that are better developed in adults.[78]

A large body of research has established that adolescent thinking is present-oriented and tends to either ignore or discount future outcomes and implications.[79] At least one researcher has found that teenagers typically have a very short time-horizon, looking only a few days into the future when making decisions.[80] Another study concluded that only 25 percent of 10th graders (whose average age is 16), compared to 42 percent of 12th graders (whose average age is 18), considered the long-term consequences of important decisions.[81] To the extent that adolescents do consider the implications of their acts, they emphasize short-term consequences, perceiving and weighing longer-term consequences to a lesser degree.[82]

Psychological research also consistently demonstrates that children have a greater tendency than adults to make decisions based on emotions, such as anger or fear, rather than logic and reason.[83] Studies further confirm that stressful situations only heighten the risk that emotion, rather than rational thought, will guide the choices children make.[84] In the most emotionally taxing circumstances, children are less able to use whatever high-level reasoning skills they may possess, meaning that even mature young people will often revert to more child-like and impulsive decision-making processes under extreme pressure.[85] All of these differences mean that children, including teenagers, are not as deterred by the threat of criminal punishment as adults are.[86]

Neuroscientists using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to study the brain are now providing a physiological explanation for the features of childhood that developmental psychologists—as well as parents and teachers—have identified for years. These MRI studies reveal that children have physiologically less-developed means of controlling themselves.[87]

A key difference between adolescent and adult brains concerns the frontal lobe. Researchers have linked the frontal lobe (especially a part of the frontal lobe called the prefrontal cortex) to “regulating aggression, long-range planning, mental flexibility, abstract thinking, the capacity to hold in mind related pieces of information, and perhaps moral judgment.”[88] The frontal lobe has also been linked to the ability to evaluate potential risks and rewards.[89] In children, the frontal lobe has not developed sufficiently to perform these functions. Throughout puberty, the frontal lobe undergoes substantial transformations that increase the individual's ability to undertake decision-making that projects into the future and to weigh rationally the consequences of a particular course of action.[90] MRI studies have also confirmed that adolescents are more likely to engage in risky behavior when in the presence of peers.[91]

These cell and neural developments in the brain provide an anatomical basis for concluding that youth up to age 18 are, on average, less responsible for criminal acts than adults. As Daniel Weinberger, director of the Clinical Brain Disorders Laboratory at the National Institutes of Health, explains, the developed frontal lobe, including its prefrontal cortex, “allows us to act on the basis of reason. It can preclude an overwhelming tendency for action…. It also allows us to consciously control our tendency to have impulsive behavior.”[92]

In addition, because their frontal lobe functions poorly, adolescents tend to use a part of the brain called the amygdala during their decision-making.[93] The amygdala is a locus for impulsive and aggressive behavior, and its dominance over the undeveloped frontal lobe makes adolescents “more prone to react with gut instinct.”[94] In adult brains, the frontal lobe offers a check on the emotions and impulses originating from the amygdala.[95]

The Difference According to Florida Youth

Many of the youth directly charged in adult court interviewed for this report were, in retrospect, acutely aware of the ways in which their young age and lack of maturity affected their decision-making capabilities at the time of their crimes.

Luke R., serving a 3-year prison sentence for robbery, reflected upon the choices he’d made. “I was impulsive. I wouldn’t think about the consequences.”[96] Another young man, now 22 and still on probation for a crime he committed when he was 17, reflected that, “I don’t do the same things I was doing. I think about things before I do them.”[97] Ava L., who was arrested at 17 for drunk driving, said that “It didn’t hit me until I turned 19 that I need to get my life together and I feel like I got [it] together but it’s still on my record.”[98] Janine C., a 17-year-old who served a one-year jail sentence after pleading guilty to a burglary she had committed when she was 16, pointed out that, for juveniles, “the light bulb could still go off.”[99]

The idea that teenagers are in the process of maturing and able to be rehabilitated was also mentioned repeatedly.

- “I’d never done anything like that before. I don’t think they understood that everyone makes mistakes. Everyone does something bad once.”[100]

- “I don’t think kids should be in adult prison, what they need is a deeper route through the juvenile system so that kids can really change.”[101]

- “You know everybody makes mistakes, you learn as you go on.”[102]

Parents and family members agreed. Stephanie G., Thomas G.’s mother, said about direct file, “They are young. They need some guidance. Kids do stuff all the time and a lot of time they don’t know what they’re doing or why.”[103] One judge who has presided over juvenile court for 14 years observed, “I’ve been here long enough to understand that when someone is 16 and I ask them why they did it and they say ‘I don’t know,’ I believe them.”[104]

|

Case Study: Matthew N. When Matthew N. was 17 years old, he and two friends were arrested for burglarizing a house. According to the police report, the couple who lived in the house called 911 when they heard what sounded like someone trying to get in through the back door. When police arrived at the scene, Matthew and the two other perpetrators were walking towards the car they had parked in the driveway. They had cut through the rear porch’s screen door, removed a printer from the porch, and left the printer by the side of the house. Matthew had been arrested before for burglary, trespass, and vandalism and was on juvenile probation at the time of the break-in. He and his co-defendants (both adults) in the printer case all eventually pled guilty. Matthew received an adult felony conviction and was sentenced to two years of house arrest followed by one year of probation. Matthew was surprised to have been charged directly in adult court. “I thought they based it on the seriousness of the charges,” he said. The experience of adult court was stressful for Matthew. “In adult court you could tell there were a lot of people coming through so the judge didn’t really care about your case other than what the charges are, and the prosecutors were just trying to get you as much time as they can,” he said. To him, it seemed like the judge played less of a role in adult court than in juvenile court. “In adult court the prosecutor does more.” He also recalled that “in adult court there was a lot I didn’t really understand.” Indeed, at the time of his interview he was still under the impression that “the juvenile judge makes the decision” to send a case to adult court. Being in Orange County Jail, where he was incarcerated for five months before pleading guilty, was even more stressful for Matthew. The corrections officers, he said, were crazy. They be doing some crazy stuff. I remember one time somebody had stolen some bread off the lunch cart and they had everyone locked down for three days. One time I had gotten kicked out of the classroom for something stupid—I was in the hallway trying to talk to someone in another class. In jail, he said, “I missed my bed, missed my home. I missed just being able to walk outside.” At the time of his interview with Human Rights Watch, Matthew was serving the house arrest part of his sentence. He was attending college and lamented the decisions he had made that had led to his arrest. “I feel like I got my head more on the right track. I’ve got a plan. If I could go back to that night, I’d give myself the plan I have now.” He did not agree with the decision to charge him directly in adult court, or with Florida’s direct file policies in general. “Kids in adult court, that could ruin the rest of their life.” [105] |

III. Rights Put at Risk by Direct File

Charging Decisions: Opaque and Unlimited Discretion

The direct file law does not adequately take into account the best interests of the child, is difficult for children to understand, and produces arbitrary results.

So perfunctory is the process that many young people Human Rights Watch spoke to had no idea what was happening until they were taken from juvenile detention to adult jail. “When they came to get me I thought I was going home,” one youth recalled, “instead they took me to county jail!”[106]

Langston T. realized that he was being tried in adult court only when he appeared at his bond hearing in criminal court. “Before that I didn’t even know you could go to county [jail]. I thought you had to be 18,” he said.[107] When asked to explain what direct file was and how the process worked, Langston said “I think direct filed is charged as an adult. I don’t know who decides.”[108]

Kingston S. was also unaware of what direct file was prior to being transferred. “This whole time I thought, ‘I’m a juvenile, I go to juvenile court.’ I didn’t want to go to the county jail. I first heard the words direct file at my bond hearing over the TV [many bond hearings are conducted over television feeds between the courthouse and the jail].”[109]

Each of Florida’s 20 state attorneys’ offices is free to determine its own criteria and practices for making direct file determinations. As a result, practices vary widely. For example:

- The 4th Circuit (which includes Clay, Duval, and Nassau counties) has written guidelines which track the direct file statute closely.[110] The discretionary direct file section of the guidelines includes all of the enumerated felonies found in the statute except for murder, which the 4th Circuit guidelines consider to be a mandatory direct file charge.

- In the 8th Circuit (which includes Levy, Baker, Union, Bradford, Alachua, and Gilchrist counties), the juvenile division chief state attorney consults with the chief assistant state attorney, who has the final say in direct file decisions. The elected state attorney may also be consulted. In deciding whether to direct file, the 8th Circuit state attorney considers the age of the child, the nature of the crime, and the child’s record. “We’re a small legal community. We listen to the defense attorneys. It’s not policy to hear from them, there’s not a formal process.”[111]

- In the 11th Circuit (which consists entirely of Miami-Dade County), the juvenile division chief state attorney reviews every juvenile case and makes a determination of whether to file a notice of intent to direct file, based on the child’s age and prior record, as well as the nature of the charges.[112] Once the notice of intent has been filed, if the defense indicates an interest in entering a plea in juvenile court, the case is set for a “multistaffing,” or meeting that includes the prosecutor, defendant, defense counsel, and representatives from the Department of Juvenile Justice. If all parties agree on a disposition, the case remains with the juvenile court.[113]

- In the 17th Circuit (which consists entirely of Broward County), two assistant state attorneys, the assistant state attorney in charge of the juvenile division, and a junior colleague review every case considered for direct file and make the final determination, with input from the elected state attorney in high profile cases.[114] Maria Schneider, the attorney-in-charge of the juvenile division, says that her office files a “notice of intent to review for direct file” in cases where the charge is a violent crime against a person or the defendant has an “extremely long record” or is about to turn 18.[115]

- In Tampa, Florida, there is no single person or team tasked with making direct file determinations.[116] The intake state attorney who gets the case makes a determination in consultation with her division chief or with the juvenile bureau chief in the state attorney’s office (there are “eight or nine regular intake divisions”).[117]

Judges and defense attorneys throughout the state describe direct file decisions as haphazard. The use of direct file is “basically arbitrary, as I see it,” said Judge Henry Davis, who presides over juvenile court in Jacksonville, Florida, which is part of the 4th Circuit.[118] Judge Davis stated that he did not “know whether there’s any consistency. I don’t see a pattern.”[119] Buddy Schulz, a Jacksonville private attorney who has done pro bono work on children’s issues for decades, told us that he has started receiving many more calls from judges asking him to take on juvenile cases directly charged in the adult courts in the last five years, and has handled over a dozen such cases in that time period.[120] Mr. Schulz told Human Rights Watch he saw “no rhyme or reason” to determinations of which cases should be directly charged in adult court. One public defender who practices in the 10th Circuit noted prosecutors do not have “real guidelines.” She said that “if they just don’t like a kid they can direct file. If they don’t want to go to trial they can direct file. It shouldn’t be for just any reason.”[121]

In Jacksonville, defense attorneys stated that prosecutors choose to directly charge children in adult court “more on a whim and more for leverage.”[122] They said that prosecutors in Jacksonville were loath to litigate in juvenile court. “If there’s any kind of suppression issue [like a defendant’s claim that evidence against him was wrongfully obtained], they’ll send it up [to adult court],” said one Jacksonville defense attorney.[123] The Jacksonville defense attorney said that, in one instance, prosecutors had indicated that they had reviewed a case for direct file and decided to keep it in juvenile court. The case proceeded in juvenile court, but, after the defendant turned down several pleas and requested a trial, the prosecutor announced that they were once again reviewing whether the case should be directly charged in adult court.[124]

Other lawyers described the system as valuing consistency over individualization by subjecting all crimes within certain categories to direct charge in adult court. “Here, their attitude is if you’re 16 or 17, and you burglarized a house, they’re going to direct file you. If you steal a car, they’re going to direct file you,” said one Tampa (13th Circuit) public defender, “anything with a gun they’ll direct file.”[125] Representatives of the 13th Circuit state attorney’s office denied that they automatically direct filed all gun cases, but said the presence of a gun was a factor they considered.

Teenagers themselves were much less clear about what charges could land a person in adult court. One teenager who was awaiting trial in Orange County Jail had heard about direct file because he had “seen other people from [the juvenile detention center] get direct filed.”[126] In his mind, “[i]f you had a serious charge you could go to the adult place.” He had no idea that he was eligible to be charged directly in adult court until he was picked up from the juvenile detention center and taken to the adult jail. “I felt bad,” he recalled. “I didn’t know where I was going. It was a third degree felony and I thought you only went in [to adult jail] for murder and stuff.”[127]

Young people who spoke to Human Rights Watch overwhelmingly felt that direct file decisions were arbitrary. Many people interviewed for this report did not even know that the prosecutor made the decision to send them to adult court. One child thought he had been charged directly in adult court because “the [juvenile] judge got tired of seeing me.”[128] Another young person, who was 14 years old at the time of arrest, said in a letter to Human Rights Watch that “I was prosecutorial direct file by my juvenile judge which was my adult judge best friend.”[129] Those who did know that the prosecutor was responsible for the decision criticized the process as biased. “I feel like the prosecutor’s one-sided,” said one teenager who was on probation for a robbery attempt. “I feel like if anybody should do that it’s the judge. The judge is supposed to try to mediate. The prosecutor’s all for the state.”[130] Kyle F., who is serving three-and–a-half years after pleading guilty to a robbery charge, said, “you can’t put that much control in one person’s hands.”[131]

The lack of a review mechanism for direct file decisions compounds the problems caused by giving prosecutors such broad discretion.[132] Most prosecutors interviewed for this report felt that their responsibility to the “community” that elected them was an appropriate check on broad prosecutorial discretion to charge children directly in adult court. When asked about the potential for a prosecutor to abuse her discretion, Maria Schneider, head of the juvenile division of the 17th Circuit state attorney’s office, said “that’s always a threat in criminal justice. That’s why the community has to get involved.”[133] William Cervone, the elected state attorney for the 8th Circuit of Florida, stated that prosecutors are in a better position to make direct file determinations because they better reflect “the community perspective. Community members can come into my office and meet with me,” he said, “judges don’t really do that.”[134] Todd Bass, the juvenile division chief for the 11th Circuit, which consists entirely of Miami-Dade County, stated that, “We are the only agency that is both responsible for the wellbeing of the child and the best interest of the community.”[135]

Whether a state attorney’s office is opting for direct file arbitrarily, as a matter of convenience to avoid juvenile court litigation, or automatically transferring all children charged with certain crimes, children’s protected status or capacity for rehabilitation is not taken into account. Many young people interviewed for this report seemed to understand this, and felt a sense of injustice and hopelessness as a result. Luke R. described feeling hopeless once in adult court, saying, “I’ve seen people, juveniles [get in trouble] three, four times and never get prison. I never had a felony on my record [and they sent me to adult court]. I may as well just quit, that’s how I felt.”[136] John C. felt similarly hopeless when he found out he was being charged in the adult system. “I felt like my life was gone,” he said. [137]

Judge Janet Ferris, a retired judge who began her career as a prosecutor, oversaw hundreds of juvenile cases during her 11 years on the bench. She described the current direct file system as one in which “the state attorney holds all the cards and everyone else is scrambling.”[138] “As long as you’re giving one party all the tools,” she said, “that’s not justice.”[139]

Arbitrary Use of Direct File and Resulting Disparities

As the data below shows, there is enormous diversity among Florida judicial circuits in transferring children to adult court. While Florida state transfer data does not distinguish between juvenile court transfers to adult court and cases filed directly by prosecutors in adult court, remember that the latter cases account for 98 percent of all transfers, allowing one to draw fairly robust conclusions about direct file cases even though the direct file cases are not separated out in the data.

For example, 1,436 youth were transferred to adult court in the 13th Circuit during fiscal years 2008 to 2012, whereas only 27 were transferred in the 16th Circuit during the same time period.

Table 3: Percent of Arrests Transferred by Circuit (FY 2008/09 - 2012/13)

|

Circuit |

Avg. Annual Youth Population |

Number of Youth Arrests Received by DJJ |

Percent of Felony Arrests Transferred |

Percent of All Arrests Transferred |

|

11th |

253,980 |

28,696 |

8.3% |

4.2% |

|

17th |

183,190 |

30,430 |

6.8% |

2.7% |

|

9th |

157,760 |

32,612 |

8.3% |

3.1% |

|

13th |

133,854 |

26,245 |

13.5% |

5.5% |

|

15th |

124,307 |

17,800 |

16.3% |

6.6% |

|

4th |

122,164 |

21,134 |

8.3% |

3.4% |

|

6th |

121,776 |

21,743 |

10.6% |

5.0% |

|

20th |

101,118 |

17,906 |

4.5% |

1.5% |

|

18th |

99,025 |

16,920 |

7.8% |

2.9% |

|

5th |

88,675 |

16,019 |

6.5% |

2.8% |

|

7th |

81,727 |

17,926 |

5.9% |

2.5% |

|

10th |

73,659 |

19,545 |

9.8% |

3.6% |

|

1st |

70,019 |

14,260 |

11.7% |

4.3% |

|

12th |

58,506 |

12,350 |

7.8% |

3.0% |

|

19th |

56,816 |

11,261 |

10.7% |

3.9% |

|

2nd |

34,393 |

6,345 |

8.4% |

3.3% |

|

8th |

32,338 |

7,032 |

7.0% |

2.9% |

|

14th |

27,420 |

5,001 |

9.5% |

3.7% |

|

3rd |

17,908 |

3,532 |

9.5% |

4.4% |

|

16th |

5,279 |

1,111 |

6.2% |

2.4% |

The variance among circuits in the percentage of youth transferred to adult court is not clearly correlated with the seriousness of youth crime in the circuit. The average annual rate at which circuits transferred arrested youth to adult court ranged from 1.5 percent of arrested youth transferred in the 20th Circuit to 6.6 percent in the 15th Circuit. We examined the relationship between the percentage of youth arrests that are transferred and the percentage of youth arrests that are violent in each circuit to determine whether circuits with more serious crime transfer children to adult court at higher rates. There appears to be no significant correlation between these two factors and no linear relationship between them.[140]

As the below graph illustrates, if there were a linear relationship between criminality and transfer rates, we would expect circuits to be plotted along an ordered line. In other words, if the decision to transfer a child to adult court has to do with the violence of the crime, we would expect to see the trend in a plot that shows the percentage of transferred youth arrests increasing as the percentage of violent youth arrests increases. Instead, circuits are plotted in a nonlinear, jumbled order.