After Liberation Came Destruction

Iraqi Militias and the Aftermath of Amerli

Summary

At the end of August 2014, following a three-month siege by the armed group Islamic State (also known as ISIS), Iraqi and United States air strikes and ground operations by pro-government Shia militias and Iraqi and Kurdish government ground forces pushed ISIS away from Amerli, a Shia Turkoman and Sunni Arab town in Salah al-Din province. Except for sporadic clashes, the area has since remained largely free of ISIS fighters.

Following the operations to end the Amerli siege, pro-government militias and volunteer fighters as well as Iraqi security forces raided Sunni villages and neighborhoods around Amerli in Salah al-Din and Kirkuk provinces. Many were villages that ISIS had passed through and in some cases used as bases for their attack on Amerli. During the raids, militiamen, volunteer fighters and Iraqi security forces looted possessions of civilians who fled fighting during the onslaught on Amerli; burned homes and businesses of the villages’ Sunni residents; and used explosives and heavy equipment to destroy individual buildings or entire villages. Human Rights Watch documented the abduction of 11 men in the course of the government’s operation, but local residents said many other men of fighting age had gone missing.

Through satellite imagery analysis Human Rights Watch confirmed building destruction in 30 out of 35 villages examined in a 500 kilometer square area around Amerli. Human Rights Watch was not able to visit all of these locations and assess all villages in the area, but conducted on-site investigations in four villages, and documented details of the militia destruction of 14 villages on the basis of witness accounts. Displaced residents and witnesses to the destruction, including Peshmerga commanders and fighters who were part of the government’s military operation, told Human Rights Watch they believed that in total, building destruction in at least 47 predominantly Sunni villages was methodical and driven by revenge and intended to alter the demographic composition of Iraq’s traditionally diverse provinces of Salah al-Din and Kirkuk.

Human Rights Watch could not determine the level of organization at which the documented attacks took place. However, witness statements, video and satellite imagery taken together appear to show that militiamen and other security forces undertook these attacks with mixed motives: as a combination of revenge attacks against civilians believed to have collaborated with ISIS, and collective punishment against Sunnis and other minorities on the basis of their sect. Militias also appear to have planned at least some of the attacks in advance, indicating culpability by government political and military bodies that oversee the militias.

Many Sunni residents of the area fled during the siege of Amerli by ISIS. Those who remained and whom Human Rights Watch interviewed after government and pro-government forces pushed ISIS out of the area said that they had not suffered abuse at the hands of ISIS, but some said that ISIS had targeted the homes and property of residents believed to be linked to the Iraqi government. Elsewhere in Iraq and in Syria, Human Rights Watch has documented serious abuses and war crimes by al-Qaeda and later ISIS, since the group came to prominence in 2013, that likely amount to crimes against humanity.

Approximately 6,000 government and pro-government fighters, including members of several militias, police, army forces, special forces, and paramilitary volunteers in the Hashd al-Shaabi (Popular Front), began a ground offensive to clear the areas surrounding Amerli of ISIS forces on September 1, 2014, one day after US and Iraqi air strikes had driven ISIS forces away from the town. These fighters were in many cases also supported by Peshmerga, as Kurdish military forces are known. Some Peshmerga officers who participated in the operations told Human Rights Watch that they joined forces with militias to “defeat ISIS” but “did not support [the militias’] methods,” which they characterized as sectarian, and said the militias targeted civilians.

Peshmerga officers told Human Rights Watch they saw 47 villages in which militias had destroyed and ransacked homes, businesses, mosques, and public buildings. Residents told Human Rights Watch that the militias included the Badr Brigades, Asa’ib Ahl al-Haqq, Kita’ib Hezbollah, and Saraya Tala’a al-Khorasani, and that they destroyed numerous villages between the towns of al-Khales, in southern Diyala province, and Amerli, about 50 kilometers to the north in Salah al-Din province.

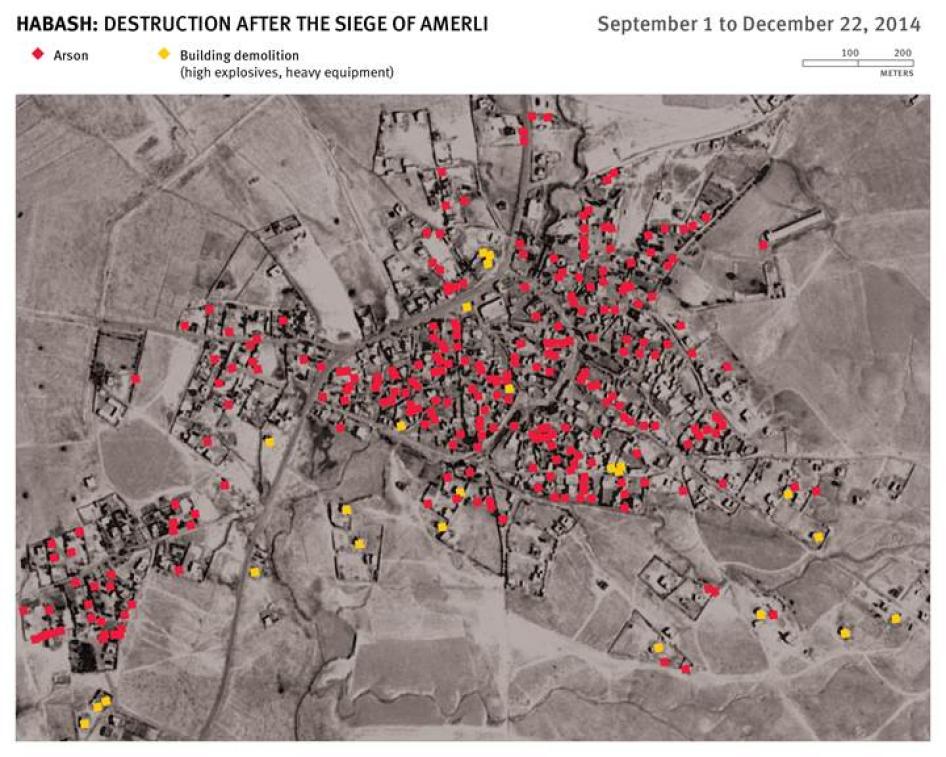

Satellite imagery corroborates witness accounts that in many cases Iraqi government forces and militias targeted the same villages and towns in which, supported by coalition air strikes, they had fought ISIS in the weeks before they lifted ISIS’s siege of Amerli. Satellite imagery showed that most of the damage they inflicted on these towns and villages after they lifted the siege resulted from arson and building demolition.

On the basis of field visits, interviews with more than 30 witnesses, and analysis of photographs and satellite imagery, Human Rights Watch found that an area that included 35 villages and towns showed extensive destruction caused by fire, explosives and heavy earth moving equipment. The evidence showed that most of the damage occurred between early September and mid-November 2014. Using satellite imagery, Human Rights Watch identified over 3,800 destroyed buildings in 30 towns and villages, including 2,600 buildings likely destroyed by fire and a further 1,200 buildings likely demolished with heavy machinery and the uncontrolled detonation of high explosives. This destruction was distinct from damages resulting from air strikes and heavy artillery and mortar fire prior to ISIS’s retreat from Amerli, which Human Rights Watch separately identified using the satellite imagery. Human Rights Watch’s field research together with the satellite imagery analysis indicates that militias engaged in deliberate and wanton destruction of civilian property after the retreat of ISIS and the end of fighting in the area.

In the four towns and villages that Human Rights Watch visited, researchers found evidence of extensive fire damage limited to the interior of buildings that would not be detectable in satellite imagery, indicating actual fire-related building damages are likely to be substantially higher than 2,600 in the affected 30 towns and villages assessed. On the basis of witness statements and analysis of satellite imagery, Human Rights Watch believes this damage was likely the result of arson perpetrated by pro-government forces.

Twenty-four witnesses, including Peshmerga officers and local tribal sheikhs, told Human Rights Watch they saw militias looting towns and villages around Amerli after the offensive against ISIS ended and immediately preceding militia destruction of homes in the town. They said they saw militiamen taking items of value—such as refrigerators, televisions, clothing and even electrical wiring—out of homes before setting the houses on fire.

In two villages (Bir al-Dahab and Habash), Human Rights Watch identified in satellite imagery the heavy smoke plumes of building fires, likely from arson attacks in progress on the morning of September 17. Human Rights Watch similarly detected in satellite imagery active detonation of fire in Laqum and Albu Ghenam on September 6; in Yengija on September 14; in Maftoul Kabir on October 8; and in Pir Ahmadli on November 2.

Arson in Habash

Arson in Bir al-Dahab

© CNES 2015/Distribution Airbus DS

Human Rights Watch documented 11 instances of militias abducting men who had returned to their homes to collect belongings after fleeing the fighting. Witnesses said the few who have been released have not come forward for fear of reprisal attacks.

Human Rights Watch did not document reports of killings of civilians, despite documenting fairly vicious reprisals. Human Rights Watch has documented allegations of militia killings and other abuses in numerous other areas of Iraq in several reports in 2013 and 2014. Media reports of militia abuses during the course of fighting increased dramatically in late 2014 and 2015. On February 17, Shia cleric Muqtada al-Sadr condemned militia abuses and announced a freeze of the activities of two militias he oversees, Youm al-Mawoud and Saraya al-Salam, that had been fighting alongside other militias and Iraqi security forces against ISIS.

Destruction of civilian objects, such as homes, cannot be justified if there were no military targets and no ongoing fighting in or near the area, and therefore would violate international humanitarian law. The abuses Human Rights Watch documented also appear to amount to collective punishment, also prohibited in international humanitarian law.

In view of the seriousness of the crimes documented here and other serious crimes carried out by the pro-government militias elsewhere in Iraq that Human Rights Watch has also documented, Human Rights Watch recommends that Prime Minister Hayder Abadi take immediate steps to disband militias; protect civilians in areas where militias are fighting; assess and provide for the humanitarian needs of people displaced by militias; and hold accountable those responsible for serious crimes such as those documented in this report. In a December 18 op-ed in the Wall Street Journal, Abadi pledged to “bring … all armed groups under state control. No armed groups or militias will work outside or parallel to the Iraqi Security Forces.” The abuses that Human Rights Watch documented in this report show that it is imperative that Abadi makes good on this pledge.

Human Rights Watch also calls on the United Nations, the US and other countries participating in the conflict in Iraq to publicly condemn widespread militia abuses in the fight against ISIS and press Iraq and the UN’s Human Rights Council to investigate crimes by militias and security forces against civilians. Countries participating in the hostilities, including the United States and Iran, should condition military assistance to Iraq on the government’s showing that it is able to end the very serious crimes perpetrated by militias.

Recommendations

To the Iraqi Government

- Prime Minister Abadi should commit to disband militias and protect civilians and work with key Shia leaders to address issues of impunity;

- Ensure that all members of its security and armed forces are fully within the line of command and subject to disciplinary measures;

- Immediately order and take all feasible steps to end militia destruction of houses and other civilian property in violation of laws-of-war prohibitions against deliberate or disproportionate attacks on civilian objects, wanton destruction of property, and collective punishment;

- Ensure access to humanitarian assistance, including housing, on an equal basis without discrimination on the grounds of ethnicity, religion or gender, for all civilians who lost homes or businesses to militia destruction;

- Provide adequate compensation or alternative housing to residents whose homes have been destroyed;

- Maintain accurate statistics on property damaged after the Amerli operations and make that information publicly accessible in a timely fashion;

- Ensure speedy and independent investigations into possible war crimes committed by militia members and security forces, and ensure the prosecution of those alleged to be responsible before courts that meet international fair trial standards;

- Facilitate immediate and unhindered access to militia-controlled areas to independent observers, journalists, and human rights monitors, including the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) and the UN Human Rights Council Investigative Committee on Iraq;

- Sign and ratify the Rome Statute so that crimes perpetrated in Iraq fall under the jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court.

To UN Bodies

- The UN Human Rights Council should extend the current mandate of its investigation mission to Iraq and ensure it includes violations of the laws of war and human rights violations committed by all sides, not only by ISIS and associated groups;

- The UN Human Rights Council should also establish a mandate of Special Rapporteur on the situation in Iraq, in order to monitor the situation of human rights in the country and make recommendations on measures to prevent violations and ensure accountability;

- The Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights should support the UN Assistance Mission in Iraq’s (UNAMI) thorough and immediate investigations into crimes committed by all parties to the conflict, and support their publication in a timely fashion.

To the United States

- Require the Iraqi government to take immediate and concrete steps to end security forces’ and pro-government militias’ commission of widespread war crimes before providing any military sales and assistance;

- Require documentation that political reform benchmarks have been met, including an end to the use of anti-terrorism legislation to detain political opposition figures; protection of freedom of expression, association, peaceful assembly, and religion; and safeguarding the rights of political opposition parties and journalists, before providing any military sales and assistance;

- Ensure all

Iraq security assistance language in relevant Fiscal Year 2016

appropriations and authorization bills includes:

- Reform benchmarks such as taking steps to address all militias operating outside Iraqi Security Forces; ending security force abuse, including torture; and releasing of political prisoners held on trumped-up counterterrorism charges;

- A reinsertion of end-user agreement language (with no waiver) for weapons transfer in order to minimize the transfer of US weapons and equipment into the wrong hands;

- Unambiguous human rights vetting language (also known as the “Leahy Law”);

- Ensure that the US Embassy in Baghdad has sufficient financial, technical, and personnel support to undertake robust human rights vetting for all US military aid and security assistance;

- Ensure that the US Embassy in Baghdad encourages regular joint monitoring visits, by the ambassador, defense attaché, and political counselor, to security force training sites in order to assess training effectiveness, including on human rights.

To Iran

- Require the Iraqi government to take immediate and concrete steps to end security forces’ and pro-government militias’ commission of widespread war crimes before providing military equipment, training, and financial assistance to Iraqi fighters, including regular army and security forces and militias.

To Other States Participating in Hostilities in Iraq

- Require the Iraqi government to end security forces’ and pro-government militias’ commission of widespread war crimes before providing military sales and assistance;

- Support a broader, prolonged mandate for the OHCHR investigation to include armed group abuse; make clear to the Iraqi government that such an investigation is essential and a key component to combating ISIS;

- Urge the Iraqi government, Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani and other Shia leaders to immediately call on militias to refrain from abusive and destruction on the battlefield.

Methodology

This report is based on field research conducted between September 27 and October 28, 2014 in Kirkuk and Salah al-Din provinces, and in the semi-autonomous Kurdish region in Iraq. Human Rights Watch researchers conducted detailed assessments of damage to homes in four villages in Salah al-Din and Kirkuk provinces after the air and ground campaign to drive ISIS forces from the vicinity of Amerli.

Researchers separately interviewed more than 30 people who said they witnessed the destruction. In most cases researchers conducted interviews in Arabic, Kurdish or Turkmen with Arabic or Kurdish to English, or Turkmen to Arabic translation. Human Rights Watch conducted interviews with witnesses and victims displaced to areas that remained insecure. We informed all persons interviewed of the purpose of the interview, its voluntary nature, and the ways in which the data would be collected and used, and obtained consent by all interviewees, who understood they would receive no compensation for their participation in interviews. Due to the risk of reprisals, Human Rights Watch has withheld the names and identifying information of victims and witnesses interviewed.

Human Rights Watch interviewed Kurdish security personnel, commanders and fighters, who were involved in the ground offensive during the Amerli operation in September, and in security operations around Amerli in October 2014. Researchers also reviewed videos and photos taken during military operations in September 2014 by witnesses and journalists, as well as photos residents took to document the destruction of their homes and villages in the weeks after the military operations.

In addition to field research, Human Rights Watch conducted a detailed damage assessment of 35 towns and villages in the Amerli region using six very-high resolution commercial satellite images recorded between September 14 and December 22, 2014.[1] Satellite imagery covering an area approximately 500 square kilometers surrounding the town of Amerli was used to identify areas of destruction, quantify damage, evaluate witness evidence, and assess the scale, distribution, and timing of building destruction. Further, satellite imagery was used to determine the probable methods of building destruction and to control for damages from air strikes, and heavy artillery and mortar fire that occurred before September 1 during the ISIS siege of Amerli.

Human Rights Watch reviewed videos posted to YouTube related to the siege of Amerli, including US and Iraqi air strike footage, and footage recorded by Iraqi forces and journalists on the ground. To help verify the time, location, and circumstances of the videos, Human Rights Watch matched visible landmarks in the videos with satellite imagery, and contacted and interviewed the people who filmed the videos whenever possible.

Human Rights Watch presented its findings to the Iraqi government on February 25, 2015, requesting a response by March 10.

I. Background

On June 14, the armed group Islamic State (also known as ISIS) laid siege to Amerli, a farming town approximately 170 kilometers north of Baghdad. Many of the town’s approximately 18,000 residents are Turkmen who practice Shia Islam. ISIS fighters shelled the town daily with mortar fire, cut the public water supply and power lines, and cut off most land supplies of food, medicine, and other necessities. The siege lasted for nearly three months, during which Iraqi government helicopters dropped food and weapons to the encircled residents twice a week.

Independent pro-government Shia militias, volunteer fighters loosely organized as the Hashd al-Shaabi (Popular Front), and government forces broke the siege on August 31 after the United States and Iraq conducted air strikes on ISIS targets in the area. Iraqi ground troops and militias entered the town on September 1.[2] By that time at least 15 civilians in Amerli, including newborn infants, had died from lack of food, water or medical treatment, and more than 250 children were suffering from severe malnutrition and dehydration.[3]

According to residents, ISIS used towns nearby Amerli in Salah al-Din province as bases while they conducted their siege of Amerli. Based on witness accounts Human Rights Watch found that ISIS had at various times entered 14 villages around Amerli over the course of the siege and occupied some.[4] Residents from more than a dozen villages in Salah al-Din province told Human Rights Watch that during the attack on Amerli ISIS forces made occasional patrols through their villages, warned residents to leave the area because of impending fighting, or were seen on the outskirts of the villages driving to other areas.[5]

Residents told researchers that in many villages residents fled the area preemptively out of fear of being caught in clashes between ISIS and Iraqi government forces, but returned to their villages for short periods of time to collect belongings or secure their homes.

In response to Human Rights Watch queries as to whether ISIS committed abuses against residents of these villages, most responded that ISIS patrolled their villages on occasion, and while they feared ISIS, residents had not been specifically targeted by ISIS fighters. However some witnesses said that houses known to belong to military and police personnel as well as some high ranking officials seen as collaborating with the government were specifically targeted and destroyed by ISIS. Human Rights Watch also received unconfirmed reports that ISIS had ransacked and damaged some Shia mosques in the surrounding area during the siege of Amerli, but was unable to verify these reports.

Human Rights Watch has documented serious abuses and war crimes committed by ISIS since it came to prominence in Syria and Iraq in 2013, including mass executions, beheadings, the abduction, killing and expelling of minorities, and sexual violence.[6]

Witnesses told Human Rights Watch that while the Iraqi army carried out the initial phases of the operation against ISIS around Amerli, militias soon came to make up the majority of fighters on the government side. In an interview with Al-Jazeera English during ground operations in Suleiman Bek, a commander from the Iraqi Ministry of Interior said the government was coordinating with commanders from the militias Asai’b Al-Haqq, Saraya al-Salaam and Badr Brigades. Al-Jazeera footage showed a large militia force undertaking ground operations immediately after ISIS had been repelled.[7]

After US air strikes and Iraqi fighters broke the siege, pro-government militias began to raid Sunni and mixed Sunni villages in the areas surrounding Amerli.[8] They raided and looted residential and commercial properties, later burning down or blowing up thousands of buildings in more than 30 villages throughout Salah al-Din province, according to displaced residents and Peshmerga officers who witnessed the militias’ campaign of destruction.[9] Media reports support these accounts.[10]

Human Rights Watch analyzed satellite imagery that showed over 95 percent of the buildings in the village of Hufriyya, for example, were destroyed and over 75 percent of buildings were destroyed in at least 17 other villages.

On September 24, a member of Salah ad-Din’s provincial council called on the Iraqi government to investigate the “burning and destruction of tens of houses [in villages] between Tuz Khurmatu and Amerli in eastern Tikrit.” Al-Bayati attributed the actions to “governmental forces and popular front [Hashd al-Shaabi],” and stated that many residents had fled the areas as a result.[11]

It is against this backdrop that Human Rights Watch conducted field investigations to determine what happened to civilians in areas around Amerli after the siege was lifted.

II. Burning of Civilian Property

Human Rights Watch found widespread burning of residential homes and businesses in villages in Salah al-Din province that Shia militia groups, including Asa’ib Ahl al-Haqq, the Badr Brigades, Saraya Tala’a al-Khorasani, and Kita’ib Hezbollah, as well as some members of the Iraqi security forces, occupied during and after the campaign to lift the siege of Amerli. On August 30, 2014 air strikes, including at least four carried out by the US, struck ISIS targets surrounding Amerli and paved the way for Iraqi ground forces, including the militias, to retake Amerli, after which they went on to occupy surrounding villages.[12] After occupying villages militia members caused large- scale damage and displacement, witnesses and security forces told Human Rights Watch.

Human Rights Watch identified in satellite imagery evidence of widespread building destruction in 30 of 34 villages in the area surrounding Amerli. Human Rights Watch identified at least 2,600 buildings likely destroyed by fire. The satellite imagery showed that building fires started during the first two weeks of September in 25 villages, and expanded during the second half of September to affect a total of 30 villages.

Although a large majority of fire-related building destruction occurred in September, there is strong evidence in the satellite imagery that building fires continued in at least 11 towns and villages though the months of October, November and possibly December, resulting in the further destruction of at least 600 buildings.[13]

The widespread burning of civilian homes by the militia groups in areas under their control appeared to have had no clear military objective and to represent collective punishment against residents of local Sunni villages.

Residents from 16 different villages in an approximate 20 kilometer radius of Amerli told Human Rights Watch of incidents of arson by members of militias who targeted civilian homes and shops and, in two villages, a mosque and school. A high-ranking Peshmerga commander closely involved in the Amerli operation told Human Rights Watch that in the mainly militia-led operations, militia and Iraqi ground forces targeted 47 villages.[14]

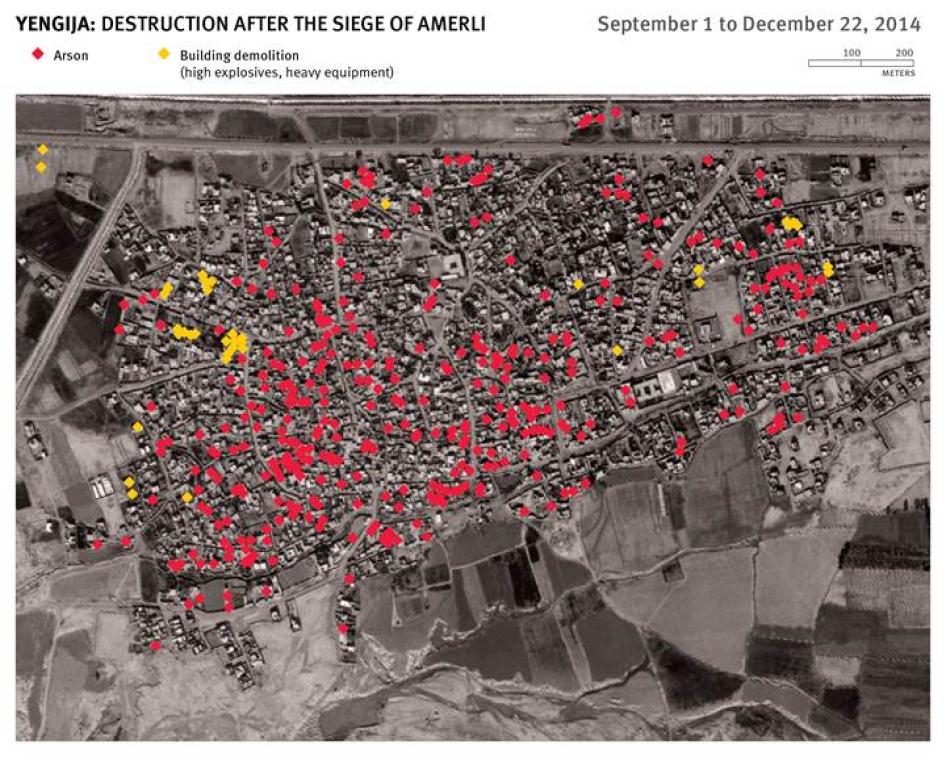

Another Peshmerga commander who was involved in joint operations against ISIS in the Suleiman Bek sub-district said he witnessed militias using kerosene to torch homes in the villages of Khazer Darli, Suleiman Bek and Yengija. He described the operation as being poorly coordinated between the different forces, but said that militia commanders were present during the arson operations. Peshmerga officers at the scene said they heard no official orders to set fire to buildings, but also said that militia commanders at the scene did nothing to stop the burning.[15]

Human Rights Watch researchers visited the towns of Yengija, al-Salaam, Tuz Khurmato and Khazer Darli on October 17 and 18, 2014 and saw ongoing fires and the burned out remains of homes. Satellite imagery of al-Salaam taken on September 14 shows evidence of large-scale fire damages to at least 25 buildings two weeks after ISIS forces left the areas around Amerli. Satellite imagery recorded on September 17, 28 and November 6, shows at least 25 additional buildings were destroyed, indicating that the arson observed on September 14 was followed by fires later in September and possibly October.[16] In addition to fire damage, Human Rights Watch identified evidence in satellite imagery of the systematic demolition of over 125 buildings in al-Salaam after September 14, consistent with the use of heavy explosives and earth-moving equipment.[17] Human Rights Watch researchers visited the village and saw rows of houses and businesses destroyed by fire, houses which had clearly been looted, with personal belongings and furniture strewn outside and doors and gates kicked in. Human Rights Watch researchers also saw rows of houses that had been destroyed, including multi-story houses that had collapsed in to piles of rubble with their concrete roofs resting on top, consistent with the use of heavy explosives. Satellite imagery later confirmed that the destruction took place after militias had taken control of the area in mid-September, 2014.

Researchers also saw that on the exterior walls of many of the houses in Khazer Darli and Yengija, Saraya Tala’a al-Khorasani and Asa’ib Ahl al-Haqq militias spray painted the names of their group, as well as anti-Sunni and pro-Shia slogans.

The militia Saraya Tala’a al-Khorasani appeared to control 95 per cent of the town of Yengija when Human Rights Watch visited on October 17. Human Rights Watch documented the destruction of 18 homes and shops side by side in a 400 meter stretch of road in the town, all of which appeared to have been deliberately set ablaze. Black soot marked the windows where flames had engulfed the interior and charred the outer walls. Homes of poorer residents, commonly made of handmade mud bricks, had crumbled in the heat of the blaze, whereas sturdier multi-level brick homes and shops showed clear signs of smoke and fire damage but remained standing. While the structure of those buildings remained intact, the interior of one or several rooms were charred and its contents destroyed. Researchers visited one home where the traces of petrol were still present after a fire, providing physical evidence of the use of a fire accelerant. Human Rights Watch spoke to witnesses who saw militias actively using accelerants such as petrol in arson attacks.

Yengija resident A.M. described the destruction he saw when he snuck into the town to gather belongings from his home earlier that month:

We can distinguish the militias because they advertise themselves—their cars bear their logo, they fly their flags at checkpoints and wear insignia on their uniforms. I heard from people who stayed in the village that [militiamen] were burning down houses, looting and blowing up houses…. I went back last week, approximately 10 days ago, because our financial situation is poor and I needed to collect our belongings, especially as winter is coming. When I got there I saw that 99 percent of the houses in my neighborhood were burnt down and nothing was left…. While I was there we saw smoke rising from three different places. The smoke was coming from the areas in front of my house, near the main road near the militia offices…. The school was burnt down too, and they burnt three clinics and four mosques.[18]

Human Rights Watch analyzed satellite imagery recorded over Yengija and found evidence of a widespread and sustained campaign of arson and demolition that lasted over two months after the end of the siege of Amerli, corroborating witness accounts.

Human Rights Watch identified a total of 415 destroyed buildings in Yengija, 375 likely destroyed by fire and a further 40 likely demolished with high explosives and earth-moving equipment. An examination of building destruction in satellite imagery over time shows during the first two weeks of September at least 50 buildings were destroyed by fire. Between September 14 and November 6 building fires in Yengija increased sharply, destroying an additional 290 buildings. The satellite imagery shows further evidence of at least 35 buildings destroyed by fire in Yengija between November 6 and December 22, 2014.

K.A., from the town of Laqum, 17 kilometers from Amerli, described to Human Rights Watch how, as militias moved through surrounding villages, he saw smoke rising from the houses that were being set ablaze. He told Human Rights Watch that the militias moved systematically from the village of Hufriyya Kabira to Hufriyya Saghira, Albu Ghenam, and Liysasat, two kilometers from his village. He told Human Rights Watch that he saw “intense” clouds of smoke rising as militias cleared the villages around Amerli, and that the burning continued for over a week through this group of villages.[19]

Arson in Hufriyya

Satellite imagery recorded over the villages of Hufriyya, Habash, and Laqum revealed evidence of widespread fire-related destruction of over 620 buildings. A majority of building fires in these villages occurred throughout September with evidence in the satellite imagery that fires likely continued into October and possibly November.

G.H., a witness from Tal Sharaf village, 30 kilometers south of Amerli, described watching the homes burning in villages under militia control two weeks after the Amerli offensive ended. He told Human Rights Watch:

All villages were attacked [by militias]. I left my village on September 20. At that time, the army and the Hashd al-Shaabi controlled the Suleiman Bek sub-district, and Amerli had been liberated. I left at 7 p.m. with my family and all the other families from the village, we only had the clothes we were wearing and our IDs. We didn’t take anything with us. When we left, the Hashd al-Shaabi had not yet entered our village, but we saw smoke coming from all the other [nearby] villages. I was still in [Tal Sharaf] when I saw the others burning. There was an influx of people coming to our village from Suleiman Bek, Habash, Ghamaz, Maftoul and Saha. They all came to our village from their homes and then went [to seek safety] in Sharaf Kabir and Albu Kabir. … The burning operation is still going on, I am a truck driver and I see the smoke from the villages as I drive on the road to Baghdad.[20]

Human Rights Watch viewed video footage and photographs taken between September 1 and 3, 2014, as militas retook villages previously controlled by ISIS, showing members of the militia groups Saraya Tala’a al-Khorasani and Badr Brigade, identifiable by their flags and the insignia on their uniforms, driving away from homes in Suleiman Bek after setting them on fire. Human Rights Watch also reviewed photos taken during the same period from Habash village, 8 kilometers from Amerli, where Badr Brigade fighters stood waving flags as militiamen behind them set shops ablaze.

Peshmerga soldiers who were in Suleiman Bek told Human Rights Watch that in some cases they saw militiamen pour unidentified liquids onto buildings immediately before setting fire to them, consistent with the use of fire accelerants such as kerosene and petrol in arson attacks.[21]

Human Rights Watch spoke to a displaced resident of Maftoul Saghir, 25 kilometers south of Amerli, who stayed in the village until August 29, the day coalition air strikes commenced. At the time, he said, ISIS had destroyed a few houses, mostly those belonging to government and security force personnel. Most homes remained undamaged up until the time he left, he said. In sharp contrast, he said, Maftoul Saghir has since been seriously burnt and many buildings destroyed. Satellite imagery reviewed by Human Rights Watch showed at least 25 percent of the village with visible fire damage.

Satellite imagery taken on the morning of September 17 shows heavy smoke plumes from buildings still burning in the villages of Habash and Bir al-Dahab, as well as evidence that over 170 buildings had already been destroyed by fire by that date even though militias secured the area on September 1.[22]

III. Looting of Civilian Property

Of the more than 30 people Human Rights Watch interviewed, 24 said they witnessed widespread looting or the results of looting in villages around Amerli. According to their accounts, militias went through neighborhoods and looted most of the houses and public buildings in each village.

Human Rights Watch interviewed several Peshmerga commanders and fighters who were part of the joint operations against ISIS in villages in the Suleiman Bek sub-district. They described how militias routinely went through civilian homes, looking for valuables as they entered each village.[23] One said:

When we controlled the village the militias came and looted and burned the houses. They were fighting for sectarian reasons…. We did our best to protect 70 percent of the houses in the areas where we have a force, but there was little we could do.[24]

A senior Sunni sheikh who travelled through some of the villages with local officials after the September 1 liberation of Amerli described the village of Maftoul Kabira, ten kilometers from Amerli, after militiamen had taken control. He told Human Rights Watch that some of the damage he saw appeared to have been caused by air strikes and fighting with ISIS while ISIS controlled the area, but that militias caused most of the destruction he saw:

ISIS burned and destroyed my house, the police chief’s house and my nephew’s house. [But] most of the destruction occurred after the militias entered. They arrived 10 days after the liberation of Amerli. When I went back recently, nearly all the houses were burned and all were looted. Many collapsed in on themselves because of the fires… I saw more than 18 villages that were destroyed and looted of their contents.[25]

In addition to militia looting of homes, witnesses told Human Rights Watch that militias had also damaged and looted several public buildings such as schools and mosques. A teacher from a school in Laqum described to Human Rights Watch how he saw militiamen looting a local school:

The school had seven trailers [that made up classrooms and an office]. [Militiamen] loaded them on top of trucks and took them towards Amerli. They only left the student desks scattered around. They burned parts of the school.[26]

He also said that the militia destroyed over 10,000,000 Iraqi dinar [US $8,700] worth of animal feed that he used on his farm.[27]

S.J., a business owner, told Human Rights Watch that, in addition to destroying houses and taking furniture, militiamen entered the Albu Ghenam village, approximately 20 kilometers from Amerli, on September 15 and took whatever possessions families left behind, including livestockthat families had left on their farms.[28]

On October 17, 2014, Human Rights Watch visited the village of Khazer Darli and saw homes and shops that, according to local Peshmerga officers, the Saraya Tala’a al-Khorasani militia, which had taken control in mid-September, completely emptied.[29] On the outside of emptied shops and houses, the militia had spray-painted its name, Shia slogans, and phrases such as “on our way to liberate Amerli.”

IV. Demolition of Civilian Property

Former residents of the villages around Amerli said they saw militias destroying homes and infrastructure with explosives and heavy machinery both during and after the fighting to lift the siege of the village. J.M., a resident of Hufriyya Kabira, 15 km from Amerli, told Human Rights Watch that between 30 and 50 cars carrying town residents who had earlier fled fighting between militias and ISIS returned on September 23, 2014, after hearing that the militias had withdrawn, to check on the status of their homes and belongings. J.M. said he returned to a scene of total devastation:

I saw the village was completely destroyed, from the health center to the newer brick houses, which they destroyed with explosives. They also blew up the Asiacell [mobile phone company] tower.[30] The mud houses were burned along with the belongings in the homes and some had been destroyed by bulldozers.… I returned [again the next day] as I had 3 houses, one of them brick, and I wanted to collect some of the windows that were still intact. They were scattered around due to the force of the explosion inside the house. I was only able to find 10 intact porcelain plates from my 3 houses. All the furniture was burned, even the steel in the ceiling had melted…. They also took the electric transformers, burned down one of the schools and destroyed the high school building. The village is no longer livable at all.[31]

Human Rights Watch examined satellite imagery recorded on the morning of September 17 over Hufriyya Kabira and found graphic evidence that over 95 percent of village buildings were destroyed, in most cases reduced to rubble. Damage signatures identified in the satellite imagery indicated a large majority of these buildings had likely been demolished with heavy explosives as well as earth moving equipment, although the possibility that some building destruction was the result of air strikes cannot be ruled out in this case.

It was also apparent that building demolition was concentrated in the center and northern sections of the village, and that buildings in the southern end of Hufriyya Kabira had been primarily destroyed by fire. Satellite imagery recorded later, on September 28 and December 22, shows evidence that limited building demolition activity continued after September 17, and building fires continued for several more weeks, raising the total number of destroyed buildings in Hufriyya Kabira to over 730.

Demolition in Hufriyya

© CNES 2015/Distribution Airbus DS

Witnesses from Laqum and Yengija also said militiamen destroyed farming land, food stores and agricultural land, ruining the livelihoods of local residents and making the prospect of return even harder. K.A. from Laqum, a village of approximately 200 houses, told Human Rights Watch that militias used earthmoving equipment to destroy two lakes that he used to farm fish, in addition to destroying and burning homes.[32]

Demolition in Yengija

© CNES 2015/Distribution Airbus DS

During field investigations in the villages of al-Salaam and Yengija, approximately 10 kilometers from Tuz Khurmato, Human Rights Watch saw several militia groups active in the area, but could clearly identify only Saraya Tala’a al-Khorasani and the Badr Brigades by their flags and the insignia on their uniforms. Researchers examined on the outskirts a restaurant and small supermarket that according to Peshmerga sources militias destroyed using RPGs and heavy machinery. Peshmerga officers told Human Rights Watch that they saw militias target the businesses and believed it was because they belonged to Kurds and Sunni Arabs. Peshmerga soldiers said that they overheard the militiamen making sectarian remarks, and inside the destroyed restaurant Human Rights Watch saw sectarian slogans scrawled on the wall.[33]

Demolition in Albu Hasan

© CNES 2015/Distribution Airbus DS

Human Rights Watch observed 18 collapsed buildings in the Yengija and al-Salaam villages and visited numerous damaged sites in the area around the villages. At least two appeared to have been damaged by aerial bombings. Peshmerga officers who had been defending the area during the fighting with ISIS told Human Rights Watch that three other buildings were destroyed by mortars. In addition to the battle-damaged buildings, Human Rights Watch observed an entire street with flattened buildings in the center of Yengija, which the militia Saraya Tala’a al-Khorasani controlled at the time of the field visit in mid-October. The militia spray-painted its name and Shia slogans across several of the damaged buildings.

Human Rights Watch observed entire residential streets in Yengija where concrete houses showed damage consistent with explosions detonated inside the building. Exterior walls had collapsed, and concrete roofs lay flat and relatively undamaged across the rubble. Three former Yengija residents separately told Human Rights Watch that houses throughout Yengija had been destroyed when a militia occupying the village razed homes using explosives in the weeks that followed the Amerli operation. Human Rights Watch also viewed a video provided by residents of houses in other areas of Yengija that showed destruction that appeared to be consistent with an explosion from inside the house.[34]

Human Rights Watch also analyzed satellite imagery recorded over Yengija and identified a total of 40 buildings likely demolished with high explosives or possibly in a few cases with earth-moving equipment, consistent with evidence of local residents and direct observations by Human Rights Watch on the ground. Building demolition was concentrated in the eastern and western sections of Yengija, with the majority of fire damaged buildings in the center of town. An examination of building destruction in satellite imagery over time shows that almost all building demolition occurred in Yengija after September 14, well after the end of fighting in the area, with the majority of building demolition (30 buildings representing 75 percent of the total) occurring between September 28 and November 6.

V. Abductions and Disappearances by Militias

In the weeks after the siege of Amerli was lifted, and with the subsequent ground offensive by militias and Iraqi and Peshmerga security forces, residents of the area told Human Rights Watch that militias apprehended and forcibly detained at least 11 men who had returned to their villages. In six cases the militias have since released six men; the whereabouts and well-being of the other five, and the reason for their detention, remain unknown.

Three people told Human Rights Watch that militiamen had tortured captured residents. J.M., a resident of Hufriyya Kabira, told Human Rights Watch that members of Kita’ib Hezbollah and the Badr Brigades took his 18-year-old son and a 20-year-old friend when they returned to the village to collect their pigeons on September 25. The militias later detained a relative of J.M. in the same location. The relative informed J.M. that militiamen took him to an unfinished house in Habash village, where he said he heard the boys being abused in an adjacent room. According to J.M.:

They kept the boys in an empty room. After a short while I heard screaming and the sounds of the two boys being tortured in the room next to me. I heard them interrogating them, asking them what they were doing in Hufriyya.

J.M. said that his relative was able to escape through family connections to a powerful Shia businessman, who arranged his release. “When he came out, he called me and told me they were detained in Habash,” J.M. told Human Rights Watch.

The other boy was able to call his parents and said he was being transferred to Baghdad but the line was cut. …. As for my son, one of his friends called me and told me he saw two Hashd al-Shaabi members driving [my son’s] motorcycle. He said he recognized [it] by a sticker of a flower on the front of it that matched the one on my son’s. I believe my son is dead.[35]

J.M. told Human Rights Watch that this was not the first incident of militia and security forces taking men and boys prisoner in the area. He said that he was initially displaced to Tuz Khurmatu in February 2014, when militias along with SWAT and federal police forces arrived in Hufriyya Kabira. On August 20, 2014, 10 days prior to aerial strikes on Amerli, militias took J.M.’s 16-year-old son and 18-year-old nephew from Tuz Khurmato to a location outside of the town, where they held them for 5 days. He said the boys told him they were “burned with cigarettes and tied to a ceiling fan,” and showed Human Rights Watch photos consistent with the alleged abuse. Members of their tribe eventually negotiated their release, he said.[36]

Throughout the belt of villages surrounding Amerli, where militias have taken over and claimed to be the official security forces, several residents similarly reported that militias detained residents. Tuz Khurmato residents told Human Rights Watch that members of Saraya Tala’a al-Khorasani detained villagers who returned to salvage what was left of their personal belongings. A Yengija resident told Human Rights Watch that on approximately October 13, militias took seven people captive, released four of them nine days later, and continued to hold three people at the time of the interview.[37] One of those detained, a 21-year-old Yengija resident, described to Human Rights Watch how Khorasani members held him and a group of six men:

[When we returned to Yengija], militiamen checked our IDs and papers and allowed us in. We went and got our things and loaded them into our car. On the way out, [Khorasani] stopped us at the same checkpoint. They told us that we couldn’t leave and had to wait for the commander to come. When he came, he told me to get out of my car. [Several militiamen] took me to a house 30 meters away on the main road and blindfolded and handcuffed my hands behind my back. The man who escorted me was wearing a camouflage uniform with a badge…. For the first half hour I was alone, then about 30 minutes later they brought in another six men. They kept saying, “You are ISIS,” and I kept denying it. They were beating me randomly on my face, head, shoulders using water pipes and the butts of their weapons….They went to have lunch and then came back and beat us for an hour and half. Later that night they asked me if I was Shia or Sunni. I told them I was Shia Turkoman and they ordered me to prove it by praying the Shia way….They kept me for nine days….On the third day they took away three men: Mohamed Khalil, 45, Ayman Khazal, 20, and Hussein Khalil, 46. …Even though I am Shia, since I lived with Sunnis for so long in Yengija they thought I may be associated with ISIS.[38]

VI. Legal Framework

International humanitarian law, the laws of war, governs fighting in non-international armed conflicts such as that between Iraqi government forces, government-backed militias, and opposition armed groups. This law binds all parties, whether they are states or non-state armed groups. [39]

The Iraqi government has both downplayed the militias’ role in the conflict with ISIS and sought to justify their participation. [40] The circumstances of the conflict, as detailed in this report, indicate that irregular militias are actively participating in armed conflict and targeting civilian objects with impunity.

The laws of war governing the methods and means of warfare in non-international armed conflicts are primarily found in the Hague Regulations of 1907 and the First Additional Protocol of 1977 to the Geneva Conventions (Protocol I). [41] Most of their provisions, moreover, are considered reflective of customary international law. [42]

Central to the laws of war is the principle of distinction, which requires parties to a conflict to distinguish at all times between combatants and civilians. Operations may be directed only against combatants and other military objectives; civilians and civilian objects may not be the target of attack. [43]

Civilian objects are all objects that are not military objectives. Military objectives are those objects that “by their nature, location, purpose or use make an effective contribution to military action and whose total or partial destruction, capture or neutralization, in the circumstances ruling at the time, offers a definite military advantage. ” Civilian objects remain protected from attack unless and only as long as they become military objectives. [44]

While Iraqi government forces may have destroyed property for military reasons in some cases, Human Rights Watch found that the large-scale destruction of property by pro-government militias in the cases detailed in this report appear to violate international law.

The laws of war prohibit deliberate, indiscriminate or disproportionate attacks against civilians and civilian objects. In the conduct of military operations, parties to a conflict must take care to spare the civilian population and civilian objects from the effects of hostilities.[45]

The Geneva Conventions prohibit, as a grave breach, the “extensive destruction and appropriation of property, not justified by military necessity and carried out unlawfully and wantonly.” [46] Human Rights Watch found that in the incidents investigated in this report, the destruction meted out did not meet the requirements for military necessity.

In the instances detailed above, it appeared militias destroyed property after fighting had finished in the area and when combatants from ISIS had fled from the area. Therefore it suggests their justification for the attacks may have been for punitive reasons; or in order to prevent Sunni residents from returning to the areas from which they fled, effectively creating demographic change in areas that had been mixed-sect or majority Sunni. International humanitarian law prohibits collective punishment.

International human rights law, including the right to housing, governs the lawfulness of eviction of a population and the destruction of homes. [47] Those threatened with eviction outside of active hostilities are entitled to adequate notice, genuine consultation, and adequate compensation or alternative housing. [48]

Serious violations of international humanitarian law committed with criminal intent are war crimes. During non-international armed conflicts, war crimes include “[d]estroying or seizing the property of an adversary unless such destruction or seizure be imperatively demanded by the necessities of the conflict,” [49] and collective punishment, all of which have been documented in Human Rights Watch investigations cited in this report. [50]

Forced displacement can both be a war crime, and if carried out as a state or organizational policy in a widespread or systematic manner, a crime against humanity.

Both customary international human rights law and treaty law, including the ICCPR and the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, prohibit torture and cruel or inhuman treatment at all times, even during armed conflict and states of emergency.[51]

The UN Committee Against Torture, which reviews states’ compliance with the convention, has made it clear that “those exercising superior authority—including public officials—cannot avoid accountability or escape criminal responsibility for torture or ill-treatment committed by subordinates where they knew or should have known that such impermissible conduct was occurring, or was likely to occur, and they failed to take reasonable and necessary preventive measures.”[52]

No exceptional circumstances can justify torture. States are responsible for having effective systems in place for addressing victims’ complaints, and prosecuting torturers, those who order torture, and those in positions of authority who fail to prevent or punish torture.

Under international humanitarian law, states have a duty to investigate war crimes allegedly committed by members of their armed forces and other persons within their jurisdiction. Those found to be responsible before courts that meet international fair trial standards or transfer them to another jurisdiction to be fairly prosecuted. [53] The laws of war also provide for a state to make full reparations. [54]

Appendix I: Militia-Damaged Villages, According to Witness Statements

1. List of villages from which Human Rights Watch interviewed residents who witnessed militia destruction:

Al-Salaam

Al-Sarat

Albu Ghenam

Bir al-Dahab

Hufriyya Kabira

Khazer Darli

Laqum

Maftoul Saghir

Ouchtapa

Ramal

Suleiman Bek

Tal Sharaf

Tuz Khurmarto

Yengija

2. List of other villages where interviewees alleged militia destruction, but from which Human Rights Watch did not interview residents:

Abbud

Albu Shakr

Al-Naba

Barshal Ghalan

Bir Ahmed

Dabach

Habash

Haliwaywah

Khamas

Khashamla

Um al-Ghidar

Zarga

Appendix II: Villages Analyzed for Damage through Satellite Imagery

Al-Salaam

Albu Ghenam

Albu Hasan

Albu Hasan Shakr

Albu Kabir

Albu Ridan

Amerli

Asdah

Bir Ahmad

Bir al-Dahab

Barawjali

Bustamli

Habash

Hufriyya

Jardaghlu

Khazer Darli

Khidr

Kukus

Kutah Burun Jadid

Laqum

Maftoul Kabir

Maftoul Saghir

Pasha Kalak

Pir Ahmadli

Qirnas

Sarha

Sayyid

Suleiman Bek

Tal Harbil

Tal Sharaf

Tal Sharaf al-Kabir

Tuz Chay

Ouchtapa

Unidentified

Yengija

Acknowledgements

This report was researched and written by Tirana Hassan, Senior Emergencies researcher at Human Rights Watch, and Erin Evers, Iraq researcher at Human Rights Watch, with extensive research support from associates in Iraq. Satellite imagery analysis was conducted by Josh Lyons, satellite imagery analyst at Human Rights Watch. Joe Stork, deputy director in the Middle East and North Africa division, and Tom Porteous, deputy program director, edited the report. Senior legal advisor Clive Baldwin provided legal review.

Middle East and North Africa division associates Sandy Elkhoury and Sarkis Balkhian, and Emergencies and Program associate Kyle Hunter provided production assistance. Kathy Mills, publications specialist and Fitzroy Hepkins, administrative manager, prepared the report for publication. Freelance photo and video journalist Mani produced all footage for the multimedia accompanying the report. Grace Choi, publications director, designed the report layout and maps.

Human Rights Watch sincerely thanks all the individuals who shared their knowledge and experience, without which this report would have been impossible. In many cases individuals provided us information personal risk and in extremely difficult circumstances.

[1] Satellite imagery taken after the siege of Amerli used in this report was recorded on the mornings of September 14, 17, 28, October 25, November 6 and December 22, 2014. Additional satellite imagery recorded before the siege of Amerli on June 4, 17, August 1, October 5, 2013 and May 28, 2014 was used for comparison. Satellite imagery used in this report was collected by Pléiades-1A/B, SPOT-6 and SPOT-07. Image Copyright: CNES 2015; Distribution Airbus DS.

[2] U.S. Central Command News Release, “U.S. Military Conducts Airstrikes Against ISIL, Airdrops Humanitarian Aid Near Amirli,” August 30, 2014, http://www.centcom.mil/en/news/articles/us-military-conducts-airstrikes-against-isil-airdrops-humanitarian-aid-iraq (accessed January 9, 2014). The Hashd al-Shaabi is the body of fighters composed of people who volunteered after Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani issued a fatwa to all Iraqis to assist in the fight against ISIS, see Matt Schiavenza, “Why Ayatollah Al-Sistani's Iraq Fatwa Is So Important,” International Business Times, June 13, 2014, http://www.ibtimes.com/why-ayatollah-al-sistanis-iraq-fatwa-so-important-1600926 (accessed January 9, 2015). When it quickly became clear that these disorganized and inexperienced fighters were fighting with militias rather than government security forces, the government formed the Hashd al-Shaabi, ostensibly to make it appear that official security forces are training volunteers and overseeing their operations. Kita’ib Hezbollah leader Abu Mehdi al-Mohandis heads the Hashd al-Shaabi, calling into question the extent to which the prime minister’s office and other government offices have control over these fighters.

[3] Human Rights Watch telephone interviews with Amerli mayor Adel al-Bayati, four Amerli residents, and Turkmen support groups, September 2, 2014.

[4] Human Rights Watch interviews with displaced residents of Yengija; Hufriyya Kabira; Albu Ghenam; Maftoul Saghir; Ramal; Laqum; Khazer Darli; Tal Sharaf; Ouchtapa; and Bir al-Dahab, Kirkuk and Suleimaniyya, October 2014.

[5] Ibid.

[6] For more information see: “Iraq: ISIS Abducting, Killing, Expelling Minorities,” Human Rights Watch news release, July 19, 2014, http://www.hrw.org/news/2014/07/19/iraq-isis-abducting-killing-expelling-minorities ; “Syria: ISIS Tortured Kobani Child Hostages,” Human Rights Watch news release, November 4, 2014, http://www.hrw.org/news/2014/11/04/syria-isis-tortured-kobani-child-hostages; “Iraq: ISIS Execution Site Located,” Human Rights Watch news release, June 27, 2014, http://www.hrw.org/news/2014/06/26/iraq-isis-execution-site-located; “Iraq: ISIS Executed Hundreds of Prison Inmates,” Human Rights Watch news release, October 30, 2014, http://www.hrw.org/news/2014/10/30/iraq-isis-executed-hundreds-prison-inmates.

[7] Al Jazeera Faultlines, Iraq divided: The fight against ISIL, http://www.aljazeera.com/programmes/faultlines/2014/10/iraq-divided-fight-against-isil-2014102094753560718.html (minute 17.05), October 22 2014 (last viewed January 28, 2015).

[8] Ibid.

[9] Human Rights Watch interviews with displaced residents of Salah al-Din and Peshmerga officers, Tuz Khurmatu, October 17, 2014.

[10] Babak Dehghanpisheh, “Special Report: The fighters of Iraq who answer to Iran,” Reuters, November 12, 2014, http://www.reuters.com/article/2014/11/12/us-mideast-crisis-militias-specialreport-idUSKCN0IW0ZA20141112 (accessed January 5, 2015). According to Dehghanpisheh: “In early September, a group of Shi'ite fighters and Kurdish peshmerga fought to protect a small village near Amerli called Yangije. … The next morning, Shi'ite and peshmerga fighters went house-to-house to check IS had cleared out. … Around midday, the burned and mangled body of [an] IS fighter was lying in the sun when a group of Shi'ite fighters approached. A Reuters team saw one Shi'ite fighter behead the corpse with a large knife while a handful of fighters filmed with their phones. The dead fighter's head was mounted on a knife, and one Shi'ite fighter shouted, ‘This is revenge for our martyrs!’ The Shi'ite fighters put the head in a sack and took it away with them.”

[11] Institute for the Study of War, “Iraq Situation Report Sept. 23 – 24, 2014,” September 24, 2014, http://3.bp.blogspot.com/-ZMWALpPMYuM/VCMutkmRjgI/AAAAAAAAB44/A5Y1Z8EyWiU/s1600/2014-09-24%2BSituation%2BReport%2BHIGH-01.png (accessed January 7, 2015).

[12] United States Central Command press release, U.S. Military Conducts Airstrikes Against ISIL, Airdrops Humanitarian Aid Near Amirli, August 30 2014, http://www.centcom.mil/en/news/articles/us-military-conducts-airstrikes-against-isil-airdrops-humanitarian-aid-iraq (accessed Jan 5, 2015).

[13] The determination of fire as the probable source of damages identified from satellite imagery is normally made at the level of individual buildings, each evaluated separately based on the relative presence (or absence) of a set of usually distinct signatures including, for example: the presence of intact, load-bearing walls with a collapsed rooftop, the presence of fire burn scars on or immediately adjacent to the property, destroyed adjacent tree/vegetation cover, along with the absence of significant debris fields external to the building foundation. When possible, this is corroborated with thermal anomaly data collected by environmental satellite sensors, which can generally locate the presence of active fires to within one square kilometer. Additionally, environmental satellite imagery was used to detect the presence of large smoke plumes in at least 7 towns and villages between September and early November 2014.

[14] Human Rights Watch interview with senior pesh merga commander, Tuz Khurmatu, October 17, 2014. Names of villages on file with Human Rights Watch.

[15] Human Rights Watch interview with pesh merga commander, Tuz Khurmatu, October 15, 2014.

[16] See infra FN 13.

[17] Satellite imagery of al-Salaam taken on September 14 also shows evidence of large-scale heavy artillery and mortar bombardment of the town occurring during the campaign against ISIS forces in late August 2014,

[18] Human Rights Watch interview with A.M., Kirkuk, October 25, 2014.

[19] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with K.A., October 21, 2014.

[20] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with G.H., October 25, 2014.

[21] Photos and videos obtained from a witness who travelled to Suleiman Bek, Tuz Khurmato, al-Salaam and Habash, on file with Human Rights Watch.

[22] Human Rights Watch did not analyze satellite imagery recorded on 1 September so could not, through satellite imagery alone, perfectly control for disparities between damages before that date and those analyzed in later images. Satellite images recorded on September 14 and 17, however, show obvious evidence of heavy building damage and destruction in many locations fully consistent with air strikes and heavy artillery shelling. They also show in many locations evidence of building destruction by fire (the classic signature being a collapsed roof with load-bearing walls still standing). Since Human Rights Watch has no evidence or knowledge of US or Iraqi air strikes or heavy artillery shelling conducted on or after September 1, the analysis here therefore concludes that damages resulting from air strikes and artillery shelling most likely occurred in the days and weeks before September 1 .Additionally, since conventional bombs and artillery shells normally do not cause building fires, Human Rights Watch concluded that buildings with the strongest fire-damage signatures in the satellite imagery recorded on September 14 and 17 were likely targeted by arson attacks. Nevertheless, Human Rights Watch was conservative in ascribing arson damages to buildings on or before these dates, and concentrated on arson damages after since it is more conclusive. Human Rights Watch did identify, with less detailed environmental satellite data, smoke plumes over the towns of Laqum and Albu Ghenam on September 6.

[23] Human Rights Watch interview with Peshmerga fighter, Tuz Khurmatu, October 15, 2014.

[24] Human Rights Watch interview with Peshmerga commander, Tuz Khurmatu, October 15, 2014.

[25] Human Rights Watch interview with S.S., Suleimaniyya, October 20, 2014. Villages listed include Ghamaz, Um-al-Gida, Habash, Bir al-Dahab, Oushtapa, Albu Shaker, Maftoul Saghir, Basha Galan, Maftoul Kabir, Al-Naba, Tal Sharaf, Tal Sharaf Kabir, Abu Gubir, Thalib Yashil Tapa, Wadi Alosik, and Sarha.

[26] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with K.A., October 21, 2014.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Human Rights Watch interview with S.J., October 19, 2014.

[29] Human Rights Watch interview with Peshmerga officer, Tuz Khurmatu, October 17, 2014.

[30] Human Rights Watch satellite imagery analysis shows the tower collapsed to the ground.

[31] Human Rights Watch phone interview with J.M., October 24, 2014.

[32] Human Rights Watch phone interview with K.A., October 21, 2014.

[33] Human Rights Watch interview and field investigation in Tuz Khurmato, October 17, 2014.

[34] Human Rights Watch interviews with A.A., H.A., and G.H., Kirkuk, October 23, 2014.

[35] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with J.M., October 24, 2014.

[36] Ibid.

[37] Human Rights Watch interview with A.A., Kirkuk, October 23, 2014.

[38] Human Rights Watch interview with H.A., Kirkuk, October 23, 2014.

[39]International human rights law, including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), also continue to be applicable during armed conflicts. These treaties guarantee all individuals their fundamental rights, many of which correspond to the protections afforded under international humanitarian law including the prohibition on torture, inhuman and degrading treatment, non-discrimination, and the right to a fair trial for those charged with criminal offenses. The ICESCR addresses the rights to housing, highest attainable standard of health, and employment, among other rights.

[40] Human Rights Watch interview with Prime Minister Hayder Abadi, Baghdad, September 8, 2014. Abadi told Human Rights Watch that official security forces and not militias organized the thousands-strong Hashd al-Shaabi [“People’s Front”]; Karbala Governor Aqeel Tarahy, Karbala, on September 29, 2014 told Human RIghts Watch that “Asa’ib Ahl al-Haqq, Badr, Kita’ib Hezbollah, they are our heroes…. If I didn’t have to stay here and govern I would join militias in the fight.”).

[41]Hague Convention IV - Laws and Customs of War on Land: 18 October 1907 (Hague Regulations), 36 Stat. 2277, 1 Bevans 631, 205 Consol. T.S. 277, 3 Martens Nouveau Recueil (ser. 3) 461, entered into force Jan. 26, 1910; Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts (Protocol I) of 8 June 1977, 1125 U.N.T.S. 3, entered into force December 7, 1978. The “means” of combat generally refer to the weapons used, while “methods” refer to the manner in which such weapons are used.

[42] See, e.g., Yoram Dinstein, The Conduct of Hostilities under the Law of International Armed Conflict (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), p. 11 (“Much of the Protocol may be regarded as declaratory of customary international law, or at least as non-controversial.”). See generally International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), Customary International Humanitarian Law (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2005).

[43] See ICRC, Customary International Humanitarian Law, rule 1, citing Protocol I, art. 48. According to ICRC, Commentary on the Additional Protocols, “The basic rule of protection and distinction is confirmed in this article. It is the foundation on which the codification of the laws and customs of war rests.” Ibid., p. 598.

[44] Under the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC Statute), it is a war crime to intentionally direct attacks against civilian objects, except during the time they are military objectives. ICC Statute, art. 8(2)(b)(ii).

[45] See ICRC, Customary International Humanitarian Law, rule 15, citing Protocol I, art. 57(1).

[46] First Geneva Convention, art. 50; Second Geneva Convention, art. 51; Fourth Geneva Convention, art. 147.

[47]International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, G.A. res. 2200A (XXI), 21 U.N. GAOR Supp. (No. 16) at 49, U.N. Doc. A/6316 (1966), 993 U.N.T.S. 3, entered into force Jan. 3, 1976, art. 11.

[48] See generally UN Committee on Economic, Social and cultural Rights, “The right to adequate housing (art.11.1): forced evictions,” General comment No. 7, UN Doc. HRI/GEN/1/Rev.7 (1997).

[49] See ICRC, Customary International Humanitarian Law, rule 156, citing ICC Statute, art. 8(2)(e)(xii). This offense during international armed conflicts is referred to as “wanton destruction,” described in the Fourth Geneva Convention, art. 147, as the “extensive destruction and appropriation of property, not justified by military necessity and carried out unlawfully and wantonly.”

[50] See ICRC, Customary International Humanitarian Law, rule 156, citing Protocol II, art. 4.

[51] Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, G.A. res. 39/46, U.N. Doc. A/39/51 (1984), entered into force June 26, 1987, acceded to by Kyrgyzstan on September 5, 1997; ICCPR, Articles 7 4 (non-derogable rights and states of emergency).

[52] UN Committee against Torture, General Comment no 2, CAT/C/GC/2, January 24, 2008.

[53] See ICRC, Customary International Humanitarian Law, pp. 607-11, citing the Geneva Conventions and the ICC Statute.

[54] Ibid.