Summary

In May 2010, Chinese media went into a frenzy over the case of Zhao Zuohai, a 57-year-old man who in 1999 had been convicted of murdering a neighbor. On April 30, 2010, the neighbor reappeared in their village, apparently having merely fled after a violent dispute with Zhao. Zhao, who said police torture in 1999 had led him to confess to a murder he did not commit, was released after 11 years in prison. The Zhao case is one of a number of cases of police brutality that have emerged from across China around 2009 and 2010, prompting a national outcry against such abuse.

The Chinese government adopted legal prohibitions on the mistreatment of persons in custody as early as 1979, ratified the United Nations Convention against Torture in 1988, and launched official campaigns to curb torture in the 1990s. Yet at the time of the 2009 and 2010 outcry, the use of torture and forced confessions had long been endemic to China’s criminal justice system. Even Chinese officials had characterized torture in detention as “common,” “serious,” and “nationwide.” It has received attention at the United Nations, by Chinese legal scholars, and in reports of Chinese and international nongovernmental organizations.

Following the 2009 cases, the government announced various measures to curb torture as well as convictions based on evidence wrongfully obtained. The measures included legislative and regulatory reforms, such as prohibitions on using detainee “cell bosses” to manage other detainees, and practical steps such as erecting physical barriers to separate police from criminal suspects and videotaping some interrogations.

In 2012, the National People’s Congress revised the country’s Criminal Procedure Law to require law enforcement officials to improve access to legal counsel for suspects and to exclude suspects’ confessions and written statements obtained through torture. The Ministry of Public Security, the agency in charge of the police, claims that the use of coerced confessions decreased 87 percent in 2012, that cell bosses who abuse fellow suspects are “things of the past,” and that deaths in custody reached a “historic low” in 2013. Some Chinese legal scholars contend that, due to these efforts, torture is “gradually being curbed” at least for ordinary, non-political criminal defendants.

This report— based on Human Rights Watch analysis of hundreds of newly published court verdicts from across the country and interviews with 48 recent detainees, family members, lawyers, and former officials—shows that the measures adopted between 2009 and 2013 have not gone far enough.

The detainees and defense lawyers we spoke with said that some police officers deliberately thwart the new protections by taking detainees from official detention facilities or use torture methods that leave no visible injuries. In other cases, procurators and judges ignore clear evidence of mistreatment, rendering China’s new “exclusionary rule”—which prohibits the use of evidence directly obtained through torture—of no help. Out of 432 court verdicts from early 2014 examined by Human Rights Watch in which suspects alleged torture, only 23 resulted in evidence being thrown out by the court; none led to acquittal of the defendant.

While measures such as the exclusionary rule and videotaped interrogations are positive, they are being grafted onto a criminal justice system that still affords the police enormous power over the judiciary and offers police numerous opportunities to abuse suspects. For example, the Ministry of Public Security operates the detention centers, not the Ministry of Justice, permitting police unlimited and unsupervised access to detainees. Lawyers cannot be present during interrogations and suspects have no right to remain silent, violating their right against self-incrimination. Procurators and judges rarely question or challenge police conduct, and internal oversight mechanisms remain weak. According to academic sources, only a minority of criminal suspects have defense lawyers.

Absent more fundamental reforms in the Chinese criminal justice system that empower defense lawyers, the judiciary, and independent monitors, the elimination of routine torture and ill-treatment is unlikely.

In 2014, the reversal of two verdicts by appeals courts brought positive outcomes, but more than anything the reversals demonstrated the entrenched failings of the existing system. In a landmark case, a court acquitted Nian Bin who spent eight years on death row for the murder of two children based on his confession obtained through torture. In another case, a court in Inner Mongolia issued a posthumous exoneration of Huugjilt, an ethnic Mongolian teenager executed in 1996 for rape and murder also based on a confession obtained through torture. In both cases, the internal mechanisms responsible for police oversight—police internal supervision units, the procuratorate, and the courts—missed or ignored the use of torture to obtain convictions.

If China’s leadership is genuinely committed to legal reform and to addressing growing public frustration over miscarriages of justice, it should move swiftly to ensure that lawyers are present during police interrogations, adopt legislation guaranteeing suspects’ right to remain silent, and establish an independent commission to receive and investigate complaints of police abuse. It should also go beyond measures adopted since 2009, which were modifications to a fundamentally abusive system, and instead make systemic changes that strengthen the procuratorate and the judiciary relative to the police. Such reforms should include transferring responsibility for detention facilities to the Ministry of Justice, which currently oversees prisons, and freeing the judiciary from Party control. Allowing a visit by the UN special rapporteur on torture would be a serious indication of commitment to reform.

China’s November 2015 review before the UN Committee against Torture affords the Chinese government an important opportunity to demonstrate its commitment to vigorously implementing existing laws, and to making key improvements to eradicate torture and ill-treatment of detainees. Failure to do so will raise larger questions about the government’s willingness to bring reforms to improve public confidence in the country’s judicial system.

***

A central component of the research for this report was our search of a large database of Chinese court verdicts—made possible by a Supreme People’s Court (SPC) decision requiring all courts to post decisions online starting January 1, 2014—and our analysis of the resulting subset of verdicts in which suspects alleged police torture. We searched all of the roughly 158,000 verdicts published on the SPC website between January 1, 2014, and April 30, 2014. As noted above, a total of 432 verdicts referenced torture allegations and judges excluded confessions in only 23 cases.

Further analysis of the 432 verdicts shows that very few judges investigated torture allegations in any detail. Thirty-two verdicts mention suspects’ alleged torture and then say nothing further about it. In the remaining 400 verdicts, judges addressed the torture claims, but most often relied solely on documentary evidence (247 of the 400) or on the existing case record with no additional evidentiary sources (118 of the 400). In only 35 verdicts is there any mention of live witness testimony and in every instance those witnesses were police officers; there is no sign that defense witnesses or medical or forensic experts were allowed to testify in relation to a torture claim.

Our analysis of court cases and interviews with former detainees show that police torture and ill-treatment of suspects in pre-trial detention remains a serious concern. Former detainees described physical and psychological torture during police interrogations, including being hung by the wrists, being beaten with police batons or other objects, and prolonged sleep deprivation.

Some said they were restrained for days in so-called “tiger chairs” (used to immobilize suspects during interrogations), handcuffs, or leg irons; one convicted prisoner awaiting review of his death sentence had been handcuffed and shackled for eight years. Some detainees spoke about abuses at the hands of “cell bosses,” fellow detainees used by detention center police as de facto managers of each multi-person cell. In some cases, the abuse resulted in death or permanent physical or mental disabilities. Most suspects who complained of torture to the authorities had been accused of common crimes such as theft. Interviewees said torture is particularly severe in major cases with multiple suspects, such as in organized or triad-related crimes.

In most of the cases we examined, police used torture and other ill-treatment to elicit confessions on which convictions could be secured. Abuses were facilitated by suspects’ lack of access to lawyers, family members, and doctors not beholden to the police.

Former detainees and relatives described the difficulty of retaining lawyers willing to challenge the police in court over allegations of mistreatment. In addition, many told Human Rights Watch that medical personnel who have the opportunity to report apparent torture or ill-treatment do not do so, denying detainees a critical source to validate their allegations. Videotaped interrogations are routinely manipulated, such as by first torturing the suspects and then taping the confession, further weakening suspects’ claims of ill-treatment. Police use of torture outside detention centers means that detainees often live in terror of being taken from the centers, whether for purported transfers to another facility or for any other reason.

As noted above, the exclusionary rule, one of the most important protections established to protect detainees from torture, has also proved to be of limited utility thus far. Lawyers told Human Rights Watch they welcome the rule insofar as it provides an opportunity to challenge police behavior in legal proceedings. However, in practice procurators and judges too often ignore their requests, often providing no reason for doing so, or give them only perfunctory consideration without seeking evidence to corroborate detainees’ torture claims.

Judges often evaluate torture claims solely on the basis of documentary evidence that is either produced or controlled by the police and, unlike with live witnesses, is not subject to cross-examination. In the court verdicts Human Rights Watch analyzed, not a single defense witness or expert witness testified regarding the torture claims. Although the exclusionary rule places the burden of proof on the procuratorate to demonstrate that the police obtained evidence legally, judges often continue to expect detainees to prove that torture had taken place.

The extraordinary power of the police is reflected in the pervasive lack of accountability for police abuse, recent reforms notwithstanding. Those whom Human Rights Watch interviewed—including a former judge and a former police officer—agreed that mechanisms to supervise the police are inadequate, and that police officers are rarely held legally accountable for abuse. Among the SPC verdict database cases we found only one prosecution of three police officers responsible for torture, but none served jail time. The lack of prosecutions in turn means that compensation or rehabilitation for victims is especially difficult to obtain. Former detainees who had tried to press claims for compensation said that police at most offered them some money in exchange for their silence, and that it is very difficult to access formal state compensation. Detainees’ efforts to seek accountability have produced few positive results and in some cases have even led to further punishment.

Finally, while this report focuses on the mistreatment of ordinary criminal suspects in custody, the torture and ill-treatment of those detained for political reasons remains a severe problem. Political prisoners such as Gao Zhisheng, Guo Feixiong, Hada, Cao Shunli, and countless others have suffered repeated torture and other abuses at the hands of police and cell bosses under police control to punish them for their activism and to deter others from challenging the state. They have experienced much of what is described in this report and often worse.

Key Recommendations

- Transfer the power to manage detention centers from the Ministry of Public Security to the Ministry of Justice;

- Ensure that anyone taken into police custody be promptly brought before a judge, normally within 48 hours of being apprehended;

- Revise the Criminal Procedure Law to ensure that suspects may have lawyers present during any police questioning and interrogations, and stipulate suspects’ right to remain silent during questioning;

- Establish an independent Civilian Police Commission with power to conduct investigations with respect to alleged police misconduct, including deaths in custody and police abuse;

- Amend the Detention Center Regulations to allow suspects to receive visits, phone calls, and letters from families without prior detention center approval;

- Ensure that suspects have access to doctors not beholden to the police, and train doctors and psychiatrists who work with detention centers to recognize evidence of torture and other mistreatment, both physical and psychological.

Methodology

Research for this report was conducted by Human Rights Watch researchers in interviews and document reviews conducted between February and September 2014, and in follow-up research through March 2015. As detailed below, the research included our analysis of 432 Chinese court verdicts addressing detainee torture claims comes from a pool of 158,000 verdicts from the first four months of 2014, as well as Chinese media accounts of detainee abuse cases from the same period.

The scope of this research was necessarily limited by constraints imposed by the Chinese government. The government is hostile to research by international human rights organizations, and strictly limits the activities of domestic civil society organizations on a variety of subjects, particularly those related to human rights violations. This study was conducted during one of the most serious crackdowns on human rights in recent years.

Over the past two decades, a small number of diplomats, United Nations officials, members of the National People’s Congress and its local counterparts, and selected members of the Chinese public have been allowed access to China’s detention centers. These visits have provided invaluable information, but the government strictly controls the visits and only sporadically grants them. Human Rights Watch did not have access to detention centers and relied on the corroborated accounts of others.

Research for this report included interviews with 48 former detainees, family members of detainees, lawyers, a former judge, a former police officer, academics, and members of international and domestic nongovernmental organizations. Among these, 18 were conducted with former detainees, nearly all of them criminal suspects who have no known history of political dissent. We cross-checked individual accounts through interviews with co-defendants, other detainees, and family members, as well as through examination of medical and detention records and official media reports about the cases where available.

The names and identifying details of many of those with whom we spoke have been withheld to protect them from government reprisal. All names of detainees, their family members, and lawyers used in the report are pseudonyms. All those we interviewed were informed of the purpose of the interview, its voluntary nature, and the ways in which the information would be used. All interviewees provided oral consent to be interviewed. All were informed that they could decline to answer questions or could end the interview at any time. No financial or other incentives were provided to individuals in exchange for their interviews. All interviews were conducted in Mandarin except those with international experts.

Human Rights Watch sent letters to four government departments with questions related to the report (see Appendix I). Human Rights Watch has not received any response to them at the time of publication.

As noted above, a central part of the research was our search of a large database of Chinese court verdicts—made possible by a Supreme People’s Court (SPC) decision requiring all courts to post decisions online starting January 1, 2014—and our analysis of the resulting subset of verdicts mentioning detainee torture claims (see Appendix II). [1] We looked at all verdicts in the SPC database from the period January 1, 2014, to April 30, 2014.

Of about 158,000 criminal court verdicts available in the database for that period, Human Rights Watch found a total of 432 in which criminal suspects alleged torture. We also found one verdict in which three police officers were put on trial for torture and 45 decisions in which 50 detained criminal suspects were held legally accountable for abusing detainees. The searched terms we used included “torture to extract confession” (xingxun bigong 刑讯逼供), “using violence to obtain evidence” (baoli quzheng 暴力取证), “abuse of supervisees” (nuedai beijianguanren虐待被监管人), “intentional injury” (guyi shanghai故意伤害) and “same cell” (tongjianshi同监室), and “damaging orderly detention” ( pohuai jianguan zhixu 破坏监管秩序). [2]

While these verdicts provide a glimpse into how Chinese courts make decisions regarding allegations of torture, the sample analyzed by Human Rights Watch (“the dataset”) almost certainly does not include all torture cases from that time period. The SPC decision regarding posting verdicts online provides exemptions for cases that involve state secrets or personal privacy, and cases that are otherwise “not suitable for making public,” which gives the courts wide latitude to withhold information. [3] Certain cases, such as major corruption cases involving higher level officials, seem to be missing from the SPC database. [4] In addition, many torture allegations made in court may not be recorded in verdicts, and, of course, some detainees who have been abused likely do not even raise the issue in court.

Secondary sources Human Rights Watch consulted include Chinese government documents, laws, and policies; reports from domestic and international nongovernmental organizations; UN documents on torture in China; interviews with officials from foreign governments and international organizations working on issues pertaining to torture, forced labor, and police abuse; news articles from Chinese and international media; and writings by Chinese and foreign academic experts on police abuse.

This report does not address abuses taking place outside of official criminal proceedings or those committed by forces other than that of the police under the Ministry of Public Security (MPS). It does not address abuses in administrative detention, arbitrary detention or imprisonment, or abuses by the procuratorate.[5] It does not focus on the treatment of political suspects held on state security charges. It also does not focus on police abuse in Xinjiang or Tibet, where torture has been particularly severe, as it is especially difficult to access criminal suspects there without putting them at risk. The report does address the conditions of death row inmates and those sentenced to short sentences, as they are held with criminal suspects and face similar conditions in pre-trial detention centers controlled by police.

I. Torture in China

The Chinese government has taken some steps, including strengthened legal and procedural protections, which if rigorously implemented would to some extent mitigate torture and other ill-treatment of detainees. Yet as several UN reviews have shown, few fundamental changes have actually been made.

Findings of the UN Committee against Torture

The United Nations Committee against Torture, the international expert body responsible for monitoring state compliance with the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (the “Convention against Torture”), has reviewed China’s record four times since 1988.[6] Together with the recommendations by the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, Manfred Nowak, who visited China in 2005, independent UN mechanisms and officials have made many recommendations to the Chinese government to address the problem (see Appendix III). While the Chinese government has made some progress implementing a number of these recommendations, it has yet to implement most of them, which would involve more sweeping and fundamental changes to the justice system, such as empowering the defense vis-à-vis the prosecution, and changing the power relationships among the police, the procuratorate, and the courts.

In its most recent review of China in 2008, the Committee against Torture concluded that “notwithstanding the State party’s efforts to address the practice of torture and related problems in the criminal justice system,” it remained “deeply concerned about the continued allegations…of routine and widespread use of torture and ill-treatment of suspects in police custody.” In a written response to the Committee’s concluding comments, the government defended its efforts, stating it has worked “conscientiously” and “unceasingly” to combat torture and these measures have “obtained notable results.”[7]

China will appear again before the Committee against Torture in November 2015.

Efforts to End Torture and Coerced Confessions

The People’s Republic of China’s first Criminal Law, promulgated in 1979, imposed criminal penalties for coercing confessions. Through the 1980s, economic reforms and greater openness led to an explosion of crimes. The government’s slogan of “strictly prohibit[ing] coerced confessions” became largely meaningless as authorities staged crime crackdowns that focused on results rather than following procedures.[8]

In the 1990s, the government undertook periodic campaigns that included raising police standards in criminal investigations and strengthening internal supervision and penalties for torture, but without sufficient political will or procedural guarantees, these efforts had almost no impact.[9] Since the 2000s, concerns over wrongful convictions have been regularly featured in the speeches of top leaders, and authorities have enacted legislative and regulatory measures to combat the use of torture to coerce confessions.

During the two most recent revisions of the Criminal Procedure Law, in 1996 and 2012, the government made changes aimed at curtailing the use of torture to extract confessions. [10] During the 1996 revision, it reduced the importance of confessions as criminal evidence. [11] In 2010, the case of Zhao Zuohai, which caused widespread public outrage, prompted embarrassed Chinese law enforcement authorities and the judiciary to promulgate a joint notice in 2010 with two sets of rules, one on the exclusion of illegally obtained evidence, another on evidence used in death penalty cases. [12] The former—known as the exclusionary rule—was codified in the 2012 revision of the Criminal Procedure Law.

The exclusionary rule provides that suspects’ confessions and witness statements obtained through “violence, threats and other illegal means” should be excluded from evidence and cannot be used as a basis for “recommendations on prosecution, procurator decisions, or adjudication.”[13] It allows for a pretrial process in which the defense may challenge confessions, outlines procedures and requirements for excluding the confessions, and states that police officers may be compelled to appear in court to give in-court testimony.[14] In addition to the exclusionary rule, the MPS has since 2010, also supported the videotaping of police interrogations and currently requires videotapes for cases involving capital offenses, life imprisonment, and “other major crimes.”[15]The MPS announced six months after the 2012 revisions came into effect that there had been an 87 percent drop in coerced confessions nationwide.[16]

The Chinese exclusionary rule notably does not incorporate the “fruit of the poisonous tree” doctrine. This doctrine, which the UN special rapporteur on torture considers to be part of international law, extends the rule beyond confessions obtained from torture and ill-treatment to “all other pieces of evidence subsequently obtained through legal means, but which originated in an act of torture.”[17]

Efforts to Combat Deaths in Custody and Cell Bosses

In February 2009, the Chinese media reported that Li Qiaoming, a 24-year-old criminal suspect in Yunnan province, had died from fatal brain trauma. Authorities initially claimed that he had died during a jailhouse game of “hide-and-seek” (duomaomao 躲猫猫). But after details of the case spread over the Internet, they acknowledged that three fellow inmates had beaten Li to death. Following this and other cases of severe abuses against detainees being reported in the media, the Supreme People’s Procuratorate and the MPS adopted new measures to improve practices in detention centers.[18]

The MPS says these measures have been in use since 2009, and they include surveillance cameras in detainee living quarters that can be viewed in real time by procurators on duty in detention centers, alarms in cells so that bullied detainees can report abuses to guards, physical barriers in interrogation rooms separating police officers and suspects, cooperation with local hospitals to provide better health care to suspects, and physical check-ups before suspects can be admitted in detention centers, among others.[19] The MPS has also “prohibited the use of detainees in management”—a euphemism for cell bosses—and instead has stated that “all the activities of detainees” should be “implemented by the police directly.”[20] The MPS claims that since the end of 2011 it has hired “special supervisors”—individuals outside of the police system—to carry out periodic, unannounced visits to 70 percent of its detention centers to check on conditions.[21]

Authorities also staged a campaign against cell bosses, including by seeking criminal charges against 36 cell bosses and disciplinary actions against 166 police officers.[22] In March 2010, a year after the campaign’s launch, the MPS announced that there had been no deaths in custody over the preceding year for which cell bosses were responsible.[23]

In May 2012 the MPS announced that it was revising the 1990 Detention Center Regulations and drafting a law to replace it to address some of the legal loopholes enabling the abuse of criminal suspects. The draft has not yet been made public, but the Chinese domestic press has reported on some aspects of it. One key issue is which ministry should have the power to manage detention centers. Scholars have advocated that they be transferred to a neutral party to avoid police abuse. [24] But the MPS is reportedly reluctant to give up control over detention centers because of the information it is said to obtain by covertly monitoring suspects or through informants. [25] About 12.5 percent of all crimes solved by the police are said to have been discovered this way. [26] In 2009, the MPS responded to criticisms of its management of detention centers by vesting leadership of crime investigations and management of detention centers in two different local police vice chiefs. [27]

Criminal Procedures and Time LimitsOnce the police identify criminal suspects, they can place the suspects under five types of coercive measures. Police can summon suspects (juchuan 拘传), [28] put them under criminal detention (xingshi juliu 刑事拘留), formally arrest them (daibu 逮捕), subject them to residential surveillance (jianshi juzhu 监视居住), or allow them to be released on bail pending trial (qubao houshen 取保候审). [29] The specific process and time it takes for a suspect to go through the criminal detention system varies considerably. At each step of the criminal process, the Criminal Procedure Law allows the police to extend the deadline under certain circumstances, such as if the suspect has provided no identification information, or if police discover new crimes. There are no safeguards in the law to prevent the police from repeatedly manipulating these procedural rules and detain a suspect indefinitely. Typically, after the police first summon a suspect, they can hold them for up to 24 hours before formal criminal detention. Suspects must then be transferred to a detention center within 24 hours after formal detention (but as discussed in Chapter IV below, the period before suspects arrive at a detention center can be further extended). From the day suspects are formally detained, police have up to 37 days, during which they can subject suspects to repeated instances of incommunicado interrogation, before the procuratorate approves their arrests. [30] It can then take months and sometimes years before the police finish their investigation and the procurator decides to prosecute the suspect. [31] If there is an indictment by the procurator, the suspect is put on trial, and, if convicted, can appeal and be given a second trial. Once the convicted defendant exhausts avenues for or abandons their appeal, they are transferred from the detention center to a prison. Only if the defendant’s sentence is less than three months, or if they are on death row, will they remain at the detention center. Few criminal suspects are given bail while awaiting trial, contrary to international standards. [32] Most suspects are held in detention centers (kanshousuo 看守所), for months while they await trial. These facilities are often overcrowded, have poor food and rudimentary health care. [33] Suspects have few rights under Chinese law to challenge the decision to hold them in pre-trial detention. [34] The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which China has signed but not yet ratified, states that “[i]t shall not be the general rule that persons awaiting trial shall be detained in custody, but release may be subject to guarantees to appear for trial.” It also states that those denied bail need to be tried as expeditiously as possible. [35] |

State’s Obligations to Prevent Torture and Other Ill-treatment

Under international law, governments have the obligation to protect all those in their custody from harm to their person and uphold the right of detainees to be held in humane conditions and treated with dignity.[36]

The Convention against Torture prohibits the use of torture, which is basically defined as the intentional infliction of pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, for the purpose of obtaining information or a confession, or as a punishment, by a public official or agent.[37] Also prohibited is cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, referred to as “ill-treatment.”[38]

Governments are obligated to ensure that any statement “made as a result of torture shall not be invoked as evidence in any proceedings, except against a person accused of torture as evidence that the statement was made.”[39] They are required to conduct “a prompt and impartial investigation” by “competent authorities” when they receive complaints of torture and punish “all acts of torture” in criminal law.[40] Victims of torture should be given “fair and adequate compensation” as well as physical and psychological rehabilitation.[41] Similar obligations apply in cases of ill-treatment not amounting to torture.[42]

Although the word “torture” (kuxing 酷刑) exists in Chinese, the term is not used in domestic law or media reports. A search on China’s most popular search engine, Baidu, for “kuxing” brings up articles that describe the use of torture in ancient times, rather than in the contemporary era. Instead, the government uses the term “coerced confession” (xingxun bigong刑讯逼供), defined as “corporal or quasi-corporal” punishment by judicial officers that “inflicts severe physical or mental pain or suffering” to force suspects to confess, and makes it a criminal offense.[43] It also criminalizes the same behavior when used against witnesses to compel testimonies, as well as corporal punishment of detainees in institutions of confinement.[44]

The UN Committee against Torture has repeatedly raised concerns that the Chinese government “has not incorporated in its domestic law a definition of torture that fully complies” with the convention’s definition.[45] One of the problems was that at the time the committee last reviewed China, the law only prohibited physical, but not mental or psychological, pain.[46]

The Chinese government made some progress toward addressing this problem when the Supreme People’s Court issued a judicial interpretation in 2012 that for the first time recognized the infliction of severe mental pain as an act of torture.[47] But the law does not specify the types of behaviors that would constitute such mental pain. In November 2013, the Supreme People’s Court issued an opinion document that elaborated upon the types of coercion prohibited in criminal investigations, noting that the following were not permissible: “freezing, starving, shining [a spotlight on], hanging up, and fatiguing the accused.”[48] However, because this document is not a judicial interpretation (guidelines to trials which are nationally enforceable), its legal status and thus its power in guiding judges’ decisions are questionable. Consequently, interrogation tactics such as prolonged sleep deprivation remain lawful.[49]

The government has also yet to address the problem that the laws do not clearly prohibit the use of torture except for the purpose of extracting confessions.[50] The laws only prohibit torture by judicial officers and officers of detention facilities and do not cover torture by all “others acting in an official capacity, including those acts that result from instigation, consent or acquiescence of a public official,” such as torture by cell bosses.[51] The Committee against Torture has indicated that the state has an obligation to prevent mistreatment of detainees not only by police and penitentiary officials, but also by other inmates.[52]

Chinese law also contains other significant gaps that lead to weak protections against torture and other ill-treatment. [53] Under the law, police interrogate suspects in detention centers and police stations in the absence of lawyers and other third parties.[54] While Chinese law stipulates that suspects have the right to appoint and meet with lawyers, few have the means or opportunity to seek legal counsel. There is no right to legal aid for the vast majority of suspects. As a result, most suspects have no access to lawyers.[55] Although the Chinese government introduced a provision in the revisions of the 2012 CPL that allows suspects to refuse to answer questions that incriminate themselves, the law continues to require them to “answer truthfully” in police interrogations, rendering the new provision largely meaningless and ineffective.Protections against self-incrimination do not include the right of suspects to remain silent.[56]

The UN Committee against Torture considers prompt access to a lawyer as among the “fundamental legal safeguards to prevent torture and ill treatment during detention as well as to ensure a fair legal proceeding.”[57] The committee stated:

Access to legal representation entails the prompt confidential access to and consultations in private with an independent lawyer or a counsel of the detainee's own choice, in a language he or she understands, from the moment of deprivation of liberty and throughout the detention but especially during the interrogation, investigation and questioning process. [58]

Applicable Law on Restraints and Solitary Confinement

While police may at times use restraints on individuals in custody, international human rights standards have strict procedures and conditions for their use. The UN Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners provide that instruments of restraint should only be used as strictly necessary to prevent risk of harm to individuals or others, and they are not to be used for punishment.[59] China’s Detention Center Regulations make similar stipulations.[60] Both international standards and Chinese law provide that when restraints are used, there should be efforts to limit discomfort, pain, or injuries.[61]

However, China’s relevant regulations allow individuals be restrained for up to fifteen days, and this period can be extended further upon authorization from the head of the PSB.[62] This contravenes international standards, which advise that the use of restraints be as short as possible, that is, minutes rather than hours or days.[63] The Committee against Torture has advised that detainees should be guaranteed their due process rights when subjected to disciplinary actions, “including to be informed in writing of the charges against them,” and “to be provided a copy of any disciplinary decision,” among others.[64] But Chinese detention regulations do not set out such due process protections.

The regulations also require detainees on death row—who are held in detention centers instead of prisons—to wear restraints at all times while they await execution.[65] This contravenes the comments of the UN Committee against Torture, which states that the status or legal condition of a detainee “cannot be reason to automatically impose restraints.”[66]

China’s Detention Center Regulations allow for the use of solitary confinement, called “small cell” (xiaohao 小号), for up to 15 days upon authorization by the head of the detention center. That form of confinement could follow “serious” cases of breaches of Detention Center Regulations, such as “spreading corrupt thoughts,” “damaging public property,” or getting into fights.[67] The Committee against Torture has stated that the use of solitary confinement should be prohibited for pre-trial detainees.[68]

Applicable Law on Deaths in Custody

International standards set out that all death-in-custody cases should be subjected to “thorough, prompt and impartial investigation,” including those in which relatives or other reliable sources suggest unnatural death.[69] As the UN Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary, or arbitrary executions has noted, since there is a presumption of state responsibility due to the custodial setting and the government’s obligation to ensure and respect the right to life, the government has to affirmatively provide evidence to rebut the presumption of state responsibility. Absent proof that it is not responsible, the government has an obligation to provide reparations to the family of the deceased.[70]

Beyond obligations to prosecute wrongful deaths, the authorities also need to take measures to prevent deaths in custody and respond effectively to the causes of death, including by ensuring proper oversight and adequate medical care to detainees.[71] Families should have access to “all information relevant to the investigation” and the government should release the results of the investigation in the form of a written report.[72] In cases in which the “established investigative procedures are inadequate because of lack of expertise or impartiality” or where there are complaints from the family about these problems, the government should “pursue investigations through an independent commission of inquiry.”[73]

The Chinese government issued regulations addressing deaths in custody after the string of custodial deaths in 2009.[74] According to the procedures, the police should “immediately notify” the family, and then “immediately conduct” an investigation into the cause of death. The investigation includes viewing and preserving the surveillance video of the detention cell, questioning fellow detainees, doctors, and guards, checking and preserving all related health and detention records, taking photos and videos of the body, and identifying the cause of death. Once the cause has been determined, police should notify the family and submit a report to the procuratorate. The police and the procuratorate can also order a forensic agency to carry out an autopsy, which family members and their legal representatives can attend. The procuratorate should review the police report, and conduct its own investigation in cases of “unnatural” deaths, which include deaths due to abuse but not those due to illness. The procuratorate is also empowered to conduct its own investigation if the deceased’s family disagrees with or questions the results of the police investigation.[75]

Among the shortcomings in the regulations is that they do not set out parameters for how long investigations should take. They also do not require that the agency carrying out the investigation be independent or impartial. While the regulations require that police notify the family of the investigation’s findings, they do not oblige the police to give the family a full report or disclose full details.[76]

Structure and Supervision of the Public Security PolicePrior to 1979, China’s police force primarily functioned as a political instrument of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to eliminate political rivals and cement the Party’s power; responding to ordinary crime was a lesser priority. Since the reforms beginning in 1979 which provided for a more open economy, common crime has soared, and the police have increasingly taken on a law enforcement role. [77] There are five types of police in China: this report focuses on the public security police under the Ministry of Public Security (MPS), which makes up the vast majority (86 percent) of the country’s two million police officers. [78] Public security police have several main duties, including the investigation of most criminal offenses, and managing the detention centers where criminal suspects are held. [79] The MPS guides the operations of the four lower levels of public security services through drafting rules and regulations. [80] But it is local leaders—CCP committee and government officials at the same level—that fund the police force, appoint personnel including the local police chiefs, determine police salaries, and set policing priorities. [81] The CCP controls the police through its committees in each level of the public security service, and through its Political and Legal Committee (zhengfawei 政法委), which lead and coordinate the police, the procuratorate, and the courts on law and order matters. The strong local party-state control makes the police susceptible to local political influences. [82] The power of the police has increased substantially in recent years, particularly under the leadership of Zhou Yongkang, who was minister of public security from 2002 to 2007. [83] Zhou made police chiefs the center of local power by having them appointed as secretaries of the CCP political and legal committees. [84] He expanded the nationwide political repression or “stability maintenance” (weiwen 维稳) infrastructure, further empowering the police. [85] This situation began to change around 2010, when the CCP ordered separation of the roles of police chiefs and secretaries of political and legal committees at the provincial level. [86] While the MPS has been put under greater CCP control under the leadership of President Xi Jinping, it continues to be powerful. [87] |

II. Police Abuse in Pretrial Detention

Torture to extract confession has become an unspoken rule, it is very common.

—Zheng Qianyang (pseudonym), former police officer, Heilongjiang province, February 2014

Chinese officials have characterized the use of torture as “nationwide,” “common,” and “serious,” [88] while Chinese scholars analyzing prominent cases of wrongful convictions involving capital offenses concluded that over 80 percent of these cases involved torture. [89]

Some lawyers interviewed by Human Rights Watch said the problem of torture in police interrogations has “become less serious” in non-political criminal cases because of recent legal reforms aimed at reducing torture. But other lawyers and former detainees told us that torture remains a serious problem. These variations may be due to differences of locale, prevalence of crime, varying resources available to law enforcement agencies, and other factors. The 432 allegations of torture documented in court verdicts analyzed by Human Rights Watch, however, occurred in 30 of China’s 31 provinces, municipalities, and autonomous regions. [90]

Our research also shows that criminal suspects are at risk of ill-treatment in detention at times other than during interrogations. So-called cell bosses, detainees who act as de facto managers of a cell, at times mistreat or beat detainees. Police subject some detainees to the use of restraints in so-called stress positions or prolonged solitary confinement to punish them, or to force them to work long hours without pay. While authorities say that the numbers are down, detainees continue to die in custody, in many cases allegedly due to torture and ill-treatment by police officers, guards, and fellow detainees, or prolonged lack of adequate medical attention.[91]

Physical and Psychological Abuses during Interrogations

Chinese criminal law currently prohibits infliction of severe physical or mental pain or suffering to coerce suspects to confess during police interrogations.[92] But criminal suspects who spoke to Human Rights Watch reported these methods continue to be used. They described similar methods in different provinces. Many of these methods can also be found in Chinese press reports.[93] They include:

- Being hit with hands, police batons, electric batons, hammers, iron bars;

- Kicking;

- Spraying with pain-inducing substances including chili oil (poured into one’s nose or onto one’s genitals);

- Exposure to sustained cold (cold water sprayed on a naked suspect in a sub-zero temperature room);

- Blinding with a hot, white light;

- Forcing individuals to maintain a stress position for prolonged periods;

- Deprivation of sleep, water, and food.

Criminal defense lawyers described some common methods of abuse. Beijing-based lawyer Shen Mingde, who focuses on procedural violations in the criminal system, told Human Rights Watch that many types of torture are used in China:

There are countless [methods of torture]! For example, it’s cold in northeast China, so the police take off all the person’s clothes, string him up and beat him, hitting his anus and genitalia with electric batons, slap him on his face, beat, and kick him. For another example, in Loudi, Hunan, there was another typical case, in which they tied the person’s hands behind his back to what we call a “tiger chair” or “iron chair” …. [T]hey also strung someone up on the window frame, made him squat for a long time without moving.[94]

A former police officer from Heilongjiang Province, who left the police force in 2011, told Human Rights Watch that the use of physical and psychological abuses by police is common:

Almost all suspects in criminal cases have been subject to abuses like … beatings and scolding, sleep deprivation, dehydration, and threats … Basically every public security bureau has a “tiger chair,” electric batons and others like that. They keep such tools [in the office].[95]

Victims and lawyers reported beatings and kickings. Wu Ying, a lawyer who has practiced for over two decades, told Human Rights Watch:

Yes, there is torture … like using electric batons, tying their hands at the back and beatings. The cases I usually come across involve hitting anuses, genitalia, and toes with electric batons.[96]

Beijing-based lawyer Luo Chenghu described a case he handled in 2012, in which his client, a farmer charged with homicide, was tortured:

[They] hit him with rods … for over one hour every consecutive day … he was not the only one beaten, his father and a relative were detained for over 30 days and they got beaten too.[97]

Gu Daoying, who runs a gambling parlor in Zhejiang province, told Human Rights Watch that police tortured him after they took him into custody:

[They] handcuffed both my hands and beat me, hitting and kicking was the least of it all. [One police officer] used an electric baton to hit me for six to seven hours, more than a hundred times. I fainted many times, and lost control over urination. Later he put his police baton on the floor and forced me to kneel on it for three hours.[98]

Illustration of police beating a detainee on the ground, with both of his hands in handcuffs behind his back. Human Rights Watch commissioned this and two other drawings below based on descriptions of torture and ill-treatment by former detainees and lawyers.[99] (c) 2015 Russell Christian for Human Rights Watch

Illustration of a suspect hung up on the iron grill of the window. Some former detainees say they were hung by their handcuffs, which is especially painful as the handcuffs cut into the flesh. (c) 2015 Russell Christian for Human Rights Watch

One common method is to string up the suspect by the wrists using handcuffs or ropes, sometimes with arms tied backwards. Chen Zhongshen, from Hunan Province, described how police officers tortured him: “They handcuffed me and then hung the handcuffs on the windows, just like this, heels off the ground… the handcuffs cut into my flesh. I was hung like a dog.”[100]

Other suspects also reported being beaten while hung up by their wrists:

They wrapped a cloth around my wrists then they handcuffed me, they tied a rope to the chain between the handcuffs and hung me on the pulley on the ceiling, my toes barely touching the ground. They shocked my hands with an electric baton, and they even stuck the baton into my right-hand pocket to hit my genitals. …I could not take it after about seven or eight minutes so I begged them to let me down so I could think things through.[101]

Interviewees noted that substances like chili oil are used to inflict pain or severe discomfort on suspects. Zhang Chun told Human Rights Watch: “They covered my mouth, and poured chili oil into my nostril, it ran inside and everywhere on my nose, mouth and face.”[102]

Some lawyers told Human Rights Watch that police have become sophisticated in their infliction of pain of suspects, and they employ techniques that leave little or no physical trace. They describe police using towels, books, helmets, or other items to cushion the site of injury, so as to create intense pain but leave no visible marks. Lawyer Luo Chenghu told Human Rights Watch:

Nowadays police officers beat people up with techniques. When this kid was beaten, they padded him with a thick [stack of documents], [so that the blows would] leave no [lasting], visible marks. It would be gone in under 10 days.[103]

Shanghai-based lawyer Song Sanzuo, who has been a criminal defense lawyer since 1999, said:

The use of direct physical pain has reduced greatly, but physical pain in a disguised form has increased, like continued interrogations with the police officers taking turns to exhaust suspects, or threatening and putting mental pressure on suspects and so on, threatening to arrest family members of suspects, all of these are illegal.[104]

The use of sleep deprivation appears to be endemic. Yu Zhenglu, who is in his 30s, told Human Rights Watch that he was strapped in an interrogation chair and prevented from sleeping for over 96 hours:

[They] accused me of money laundering and illegally detained me for four days and four nights without food, water, or medication. I have high blood pressure…. They also didn’t let me sleep for four days and four nights. The police changed shifts every four hours, and as soon as you close your eyes, they push you.[105]

Lei Xinmu, a farmer in his late 20s, described similar ill-treatment to Human Rights Watch. Lei was accused of robbery, which he said he did not commit: “I was sitting on a ‘tiger chair,’ and there were two spotlights on top on my head, they took turns to talk to me … they would not let me rest, I couldn’t take it any longer.”[106] After over 200 hours of sleep deprivation, Lei did not confess to the crime. After a few weeks of detention, police released him due to lack of evidence.

According to the Committee against Torture, sleep deprivation used to extract a confession is “impermissible,”[107] and prolonged periods of sleep deprivation constitute torture.[108]

Police Pressure to Solve CrimesPolice rely on torture and ill-treatment to obtain confessions for several reasons. The criminal system considers confessions to be the “king,” or ultimate form, of evidence, and the system is arranged in ways that maximize opportunities for investigators to obtain such evidence. [109] Police are expected to extract a confession in every case, which they then use to conduct an investigation to corroborate the confession. [110] Although the government has spent hundreds of billions of yuan in recent years for “stability maintenance” projects across the country, [111] police, particularly at the local level, often have inadequate financial or human resources to properly investigate crimes. [112] In addition, outside of major cities, police officers are often insufficiently trained and lack basic knowledge of how to conduct criminal investigations. [113] This under-resourcing for crime control makes it expedient for the police to rely on torture, which they consider the most efficient means of obtaining the necessary evidence for criminal prosecutions and convictions. Individual officers’ promotion through the ranks and other financial or material rewards are often based on assessment criteria that include clearance rates, the number of crimes solved compared to the number of crimes reported to police. [114] The requirements that officers need to reach a certain clearance rate—over 90 percent in some areas—puts tremendous pressure on officers to solve crimes. [115] The MPS prohibited the use of clearance rates in evaluations in 2011, and a number of provincial police bureaus followed this important step, but it is yet unclear how effective these formal announcements have been on police behavior. [116] Lawyers told Human Rights Watch that police officers in charge of investigations sometimes beat suspects to get them to admit to crimes they did not commit or to testify against others as complicit in crimes. One lawyer described a father and son held separately; both were beaten and told that the other had confessed against him. [117] In some cases the suspects already had admitted to the crimes voluntarily but the police coerced them to confess to other similar crimes that the suspects insisted they did not commit. In one case, a suspect confessed quickly to a robbery and provided details and information about his fellow robbers. The suspect was then strung up and beaten while police demanded he confess to other robberies. [118] |

Cases in Which Torture is Particularly LikelyMost of the cases of torture described in this report involve suspects charged with theft, drug sales, or robberies, all common crimes in China. [119] But a number of lawyers we interviewed said that torture is particularly common and severe in murder cases, triad-related crimes, and corruption cases. [120] In recent years, the most prominent cases of torture to extract confessions reported by mainland Chinese media have involved the latter categories of crimes, such as the case of Zhao Zuohai, accused of homicide, and that of Vincent Wu, accused of triad activity. These crimes have been specifically targeted for crackdowns by the central government in recent years because they tend to attract widespread public condemnation and attention. [121] The government has clearly made a priority of murder cases; the MPS announced in 2013 that the national rate for solving murders was 95.5 percent. [122] Some cities, such as Urumqi in Xinjiang, claimed a 100 percent rate for solving murders in 2013. [123] Lawyers we interviewed said that in these “major cases,” there is political pressure coming from the top to solve them, thus further weakening any procedural protections—however limited—that otherwise might exist in Chinese criminal law for the defendants. [124] The investigation and prosecution of such cases can create an environment especially conducive to torture and other ill-treatment, largely because officials from the procuratorate and the court are made to work together as a group (lianhe ban’an 联合办案). [125] Local governments set up “Special Investigation Units” (zhuan’anzu 专案组) involving the supposedly separate branches of police, procuratorate, the court, and the Party’s Disciplinary Commission in cases involving official misconduct. Together, and under the leadership of the local Communist Party Political and Legal Committee, the units “study the case to see how to convict” [126] the suspects. These three categories of crimes numerically make up a small proportion—about 6 percent—of the 432 allegations of torture documented in court verdicts Human Rights Watch analyzed. But the severity of the torture, and the fact that these get considerable public and media attention, means they make a disproportionately large impact on public confidence in the justice system. |

Violence and Mistreatment by “Cell Bosses”

The 2009 string of deaths in detention centers, including the infamous “hide-and-seek” death of Li Qiaoming described in Chapter I of the report, generated public outrage that pushed the government to acknowledge the problem of cell bosses—detainees who organize and abuse others on behalf of detention authorities. In 2009, the Deputy Procurator-General of the SPP Jiang Jianchu acknowledged the severity of the problem in a published interview:

We must admit that [abuse by] cell bosses have indeed been an ongoing problem for a long time. However, it is quite difficult to resolve this problem, and so I can only say that we will continue working hard to tackle the issue.[127]

In 2009, the SPP and the MPS announced a series of promising measures, including increased monitoring of detainees’ living quarters to prevent violence by cell bosses.[128] In 2014, the Ministry of Public Security said the problem of cell bosses had been “effectively curbed.”[129]

Yet former detainees and defense lawyers told Human Rights Watch that cell bosses continue to be commonly used as de facto managers of cells and act as the intermediaries between detainees and the police officers. Many facets of life—including where to sleep and organizing the purchase of extra food and necessities—are under the management of the cell bosses.

Former detainee Yuan Yifan, who is in his 30s and had been in a Guangzhou detention center, told Human Rights Watch that although cell bosses have new titles, they continue to function as de facto guards in detention centers:

They are no longer called "cell bosses” but instead "persons on duty." The police only patrol twice a day, once in the morning and in the afternoon. For the rest of the day, these "persons on duty" are in charge of keeping the order and assigning duties.… These are theoretically duties of the guards, but in practice they are carried out by these "persons on duty."[130]

The level of mistreatment and abuse employed by the cell bosses varies. Wang said those in his detention center had not mistreated fellow detainees: “There are still jail bosses, but the situation is better than before. Corporal punishment and verbal abuse are still being used, but they are less harsh.”[131]

Others said physical abuse was common. Lawyer Wu Ying who spent months in a detention center in a southern province said he witnessed “simple beatings”:

Some cell bosses … often beat others, I was abused too … the way they abuse people is to make them stand on dirty toilets, also simple beatings. Now there are surveillance cameras, hitting is less common. Sometimes you still have seven or eight people ganging up on someone.[132]

Detainee Zuo Yi said beatings were very serious in the Fujian province detention center where he was detained; a cell boss there threatened to “torture him to death slowly.” He recalled one beating:

He [the cell boss] used a clothes hanger, [he] put [my] hands on the bed and hit them with the hanger until the fingers were broken … it continued for a long time.[133]

Cell bosses mistreat and beat fellow detainees for a variety of reasons, in some cases, they dislike particular detainees or want to extort money from them. A detainee from Henan Province, Feng Kun, told Human Rights Watch:

In detention centers, if you have no connections you get beat up [by the cell boss], if you have connections you are safe and you get to share the benefits. You are fine as long as your family sends money.[134]

Another main function of cell bosses is to act as the cell’s production manager in the many detention centers that require detainees to work without pay. Cell bosses divide the work among the cell’s detainees and failure to work quickly enough or accomplish the individual quotas assigned appears to be one of the main reasons cell bosses abuse fellow detainees. Zuo Yi, who was detained in Fujian, told Human Rights Watch: “They bring your work in for you to do every day, you have to do whatever they told you to or they will beat you.”[135]

Former detainee Tong Shenmu said cell bosses use violent mistreatment as punishment for violating cell “rules”:

Beatings [by jail bosses] are mostly related to work. But there were also instances when the jail bosses beat detainees for disobedience of their rules … they have rules about when you can use the bathroom … and if you break the rule, you would get beaten up. But most of the time you get beaten up for not doing the work.[136]

Similarly American teacher Stuart Foster, who spent months in Guangzhou’s Baiyun Detention Center, told Human Rights Watch that cell bosses punished detainees who were slow in their work:

All through the assembly process, the gang [cell bosses]—the leader with assistants appointed—would go around and hit people or whip them to spur production. Again, anyone who they deem slow would not get a smoking break that day. If they continue to be a problem … then they would be brought to the front of the cell, usually at night over work and they’d be forced to face the wall like this, down on their knees and they would receive hits on their heads and kicks to their ribs … they might also cut your food ration in half … those were relatively common [punishments].[137]

Detainees told Human Rights Watch that cell bosses have a close relationship with the guards, who gave them favorable treatment including extra cigarettes and warm tea. Although much of the violence and mistreatment from cell bosses appears to be part of their “management style” to instill fear and obedience among inmates, some is done on the behest of the guards.[138] Interviewees have also reported that cell bosses beat detainees to extract further confessions and information from them, either at their own initiative, or because they were instructed by the police to make the detainee “cooperate” with the investigation. Zuo Yi told Human Rights Watch:

He [the cell boss] wanted to get credits to get his sentence reduced. He made me confess [to further crimes] and I wouldn’t, that was why he abused me. Maybe also he didn’t like me, those were the two reasons.[139]

Yu Zheng, a lawyer from Shanghai who has been practicing since 1992, told Human Rights Watch: “If you don’t obey, they tell the cell bosses to beat you, like when you don’t confess.”[140]

Another Shanghai-based lawyer, Song Sanzuo, said:

Some cell bosses are in their nature abusive; but a minority [abuses others] when instructed by the police guarding the cell. The former is common everywhere in the world—abusing newcomers, forcing them to sleep next to the toilets; the latter is when the guards want to get the suspect to cooperate, they ask the cell boss to “teach them a lesson,” for their bad attitude.[141]

Use of Restraints and Solitary Confinement

Police officers regularly use restraints—known as the “tiger chair”—to immobilize suspects during interrogations. Former detainees told Human Rights Watch that they were strapped in this metal chair for hours and even days, deprived of sleep, and immobilized until their legs and buttocks were swollen.

Former detainee Ma Yingying told Human Rights Watch that she was strapped to this device for weeks, during which time she lost considerable weight and fainted multiple times:

I sat on an iron chair all day, morning and night, my hands and legs were buckled. During the day I could nap on the chair, but when the cadres came, they scolded the police for letting me doze off.… I sat until my buttocks bled.[142]

Former detainee Lei Xinmu said:

The “tiger chair” is an iron chair, its iron buckles fastened around your hands and feet. I sat on the tiger chair, and had two spotlights shining on top of my head, they took turns talking to me … and they did not let me sleep, I could not stand it … [I was buckled in the chair] for nine days and nights.[143]

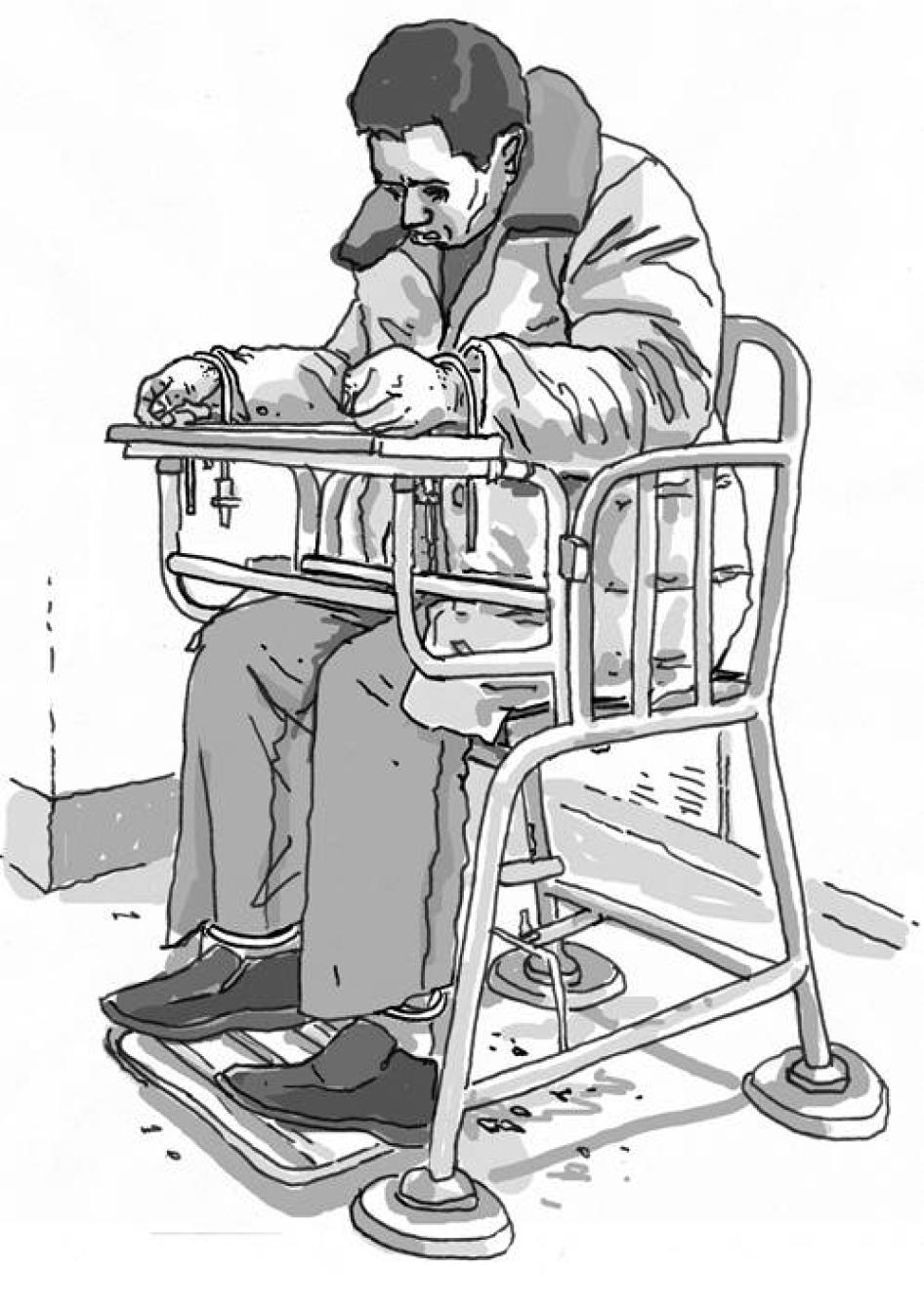

Illustration of a suspect restrained in what the police call an “interrogation chair,” but commonly known as a “tiger chair.” Former detainees and lawyers interviewed say that police often strap suspects into these metal chairs for hours and even days, often depriving them of sleep and food, and immobilizing them until their legs and buttocks are swollen.(c) 2015 Russell Christian for Human Rights Watch

Some police have acknowledged the use of this device, but they contend that it is used to prevent suspects from harming themselves and others. According to a written statement by the Guiyang City Public Security Bureau:

The "tiger chair" is in fact an “interrogation chair” used by the public security authorities according to the relevant provisions of the Ministry of Public Security ... the chair is to restrain suspects for preventing them from suicides or self-injuries or against violence or attacks against interrogators.[144]

According to an MPS notice, interrogation rooms should be equipped with “special seats” for suspects that should be “secure” and “fixed to the ground” with “safety features.”[145] But the notice did not give details as to the kinds of features this seat should have, the circumstances under which the chair should be used, or how long suspects can be strapped to the chair. While police have contended the chair is for protecting suspects from hurting themselves or others, the relevant regulations governing police equipment and restraints do not include interrogation chairs.[146]

Detention center staff also regularly use handcuffs and leg irons on detainees.[147] Relevant regulations require that detainees on death row awaiting court review of their cases and convicted inmates awaiting execution be restrained at all times using leg irons and handcuffs, often with leg irons and handcuffs linked together, presumably to prevent escape.[148] This could mean months and sometimes even years in restraints as detainees appeal their cases.

One detainee convicted of homicide whose appeal of his death sentence was pending had been handcuffed and shackled in leg irons in an uncomfortable position for 24 hours a day, seven days a week for the past eight years, according to a family member:

He lives with handcuffs and leg irons, for eight years he has lived like that. In the letters he sent, he said what he wanted the most was to “be able to put on clothes and eat on his own,” but he can’t. He is less than an animal, which is extremely cruel. In the detention center, he is so tightly fastened, when it is winter and so cold, he can only wrap clothes around himself. It is also difficult for him to use the toilet. He cannot straighten his body, the chains [in between handcuffs and leg irons] are very short.[149]

Long-time Beijing-based human rights lawyer Ze Zhong told Human Rights Watch:

Prisoners with death sentences are guarded more strictly. Once the sentence is handed down, they have to wear handcuffs and leg irons … their hands and feet are shackled together, they cannot stand up straight, for usually between eight months and a year between their sentence and execution.[150]

Detention centers also use painful restraints for prolonged periods to punish detainees for bad behavior, such as fighting other detainees, and failure to obey the staff’s orders or detention center rules. Former detainee Li Fang, who is in her 50s, recalled one episode in which a fellow detainee was chained for days:

We had to sit still and were not allowed to talk. You were physically punished if you talked. There was one woman who was quite deaf, and she couldn’t hear the guard, who said we were not allowed to talk. She moved and she was handcuffed to an iron bar with her hands twisted behind her, and they left her there for two to three days, even during meal times or sleep. I felt sorry for her so I held a bucket for her for when she needed to urinate or defecate.[151]

Former detainees we interviewed all noted that this punishment is particularly uncomfortable and painful, because the leg irons are heavy and make it difficult for the detainees to move or stand to their full height, or cut into their skin. Lawyer Wu Ying, who was held in a detention center, explained:

Handcuffs and leg irons were common when people didn’t obey the detention center rules. One way was to make you wear both, it means that the handcuffs and leg irons are chained together, and they are heavy. You can’t take them off even in sleep; it is uncomfortable because you can’t straighten yourself.[152]

Detainees sometimes have also been chained to a stationery object in the cell, so they effectively cannot move for the period of the punishment. Former detainee Stuart Foster told Human Rights Watch that:

In the eight months, there were four occasions [on which restraints were used], that was generally because detainees were not working and were causing disruptions like arguments and fights.… Two different inmates were chained to the floor for two weeks, which meant they were unable to go to the toilet, another inmate would bring them a bucket. When you were chained to the floor they’d cut your ration, I remember one boy that … in the two weeks he was chained to the floor by the end he looked like he was dying of starvation.[153]

In some detention centers, detainees are required to sit in one position for hours without moving, which can be very painful. Former detainee Yuan Yifan said:

We had to sit all day from the time we woke up to until bedtime. We couldn't even stretch our legs but we had to sit cross-legged. Except for when we did [group] exercise or during breaks, we had to sit without even changing the direction [we face]. My legs were still swollen weeks after I got out of the detention center.[154]

Former detainee Yang Zhenling described a similar situation:

They forbid us from lying down in bed or walking around [the cell], and we had to sit cross-legged in a certain area for at least eight hours a day. That was effectively torture, and it was painful.[155]

Detainees told Human Rights Watch that the restraint periods can be days or even weeks depending on the “mood of the guards.” Zuo Yi, who now works as a driver after release from a Fujian detention center, told Human Rights Watch:

So many of them wear handcuffs and leg irons … the amount of time is totally up to guards’ mood to decide, sometimes two weeks, sometimes 8 to 10 days.[156]

Wu Ying said:

As to how long you have to wear them, it depends on the guard’s moods. In our cell one man was wearing them for two to three weeks.[157]

Several detainees said that they witnessed others subject to solitary confinement during pre-trial detention. Ma Yingying said:

There were two women who fought. Whoever fought had to be locked up [in solitary confinement], for one or two days, it depends on how serious were the fights. The guards could decide how many days you would be detained.[158]

Tong Shenmu, a professional in his mid-30s detained for economic crimes, said it was common for detainees to be subjected to solitary confinement:

Many people have been locked in these small cells. Those who were loud, noisy, or crazy were locked up on their own between one and two weeks [at a time].[159]

The cells are often small, dark rooms that can barely accommodate one person. Guangzhou lawyer Chen Le told Human Rights Watch:

My client talked about solitary confinement … it is small and dark in there, and you can’t even stand up straight.[160]

Former detainee Tong Shenmu said:

The small cell is similar to the [general] big cell. They just partition the general cell into smaller 5-meter-square cells, each with soft pads on all four sides.[161]

Shandong-based lawyer Hua Shengyu said a number of his clients were detained in these “small cells” and described the conditions there:

[They are] detained in a very small room without sunlight or windows…they can barely lie down…in ordinary criminal cases [they are held in solitary confinement] because of their “bad attitude” or because they beat fellow detainees in the cell. It is to make them compliant again.[162]

Former detainee Li Fang described her experience in the cell:

I was shackled to an iron chair, the so-called tiger chair. The room was about 4 square meters. I was there for one day and one night … there was no window in the room, I was totally alone.[163]

Detainees told Human Rights Watch that these punishments are imposed in an arbitrary manner. Lawyers noted that there is no formal way to effectively challenge these disciplinary actions. Detainee Li Fang told Human Rights Watch that few dare to challenge the guards on their arbitrary punishment:

There is no legal basis for any of these punishments, there is no standard procedure. They can ask you to do anything, and you wouldn’t dare to disobey.[164]

Deaths in Custody

[T]here are three most common causes of unnatural deaths [in detention]: First, forced confessions through torture…. The second is violence against the suspect inside detention centers as [police] try to solve the case.… The third is giving management power to cell bosses. —Former Director of the Ministry of Public Security’s Bureau of Detention Administration, in a media interview, Beijing, June 10, 2010[165]

While Chinese regulations outline a set of procedures for handling deaths in custody—including viewing the detention center’s surveillance video, questioning fellow detainees, doctors, and guards, and an optional autopsy—how authorities actually handle deaths in custody appears to vary considerably.

Human Rights Watch interviewed family members of four detainees who had died in custody and all said they were told by the police that their family members had died of “natural causes”; in most cases, it was unclear to them whether investigations had been conducted.

Bai Qingzuo, father of a 17-year-old who died days after a month in custody in a detention center in northwestern China, said the authorities did not conduct an investigation into his son’s death:

There was no investigation.... They said he died from tuberculosis, a natural cause. They didn't give me any explanation, they just told me to settle the matter privately with compensation.[166]

In Bai’s son’s case, police appear to have relied on a common tactic: releasing a fatally ill prisoner on medical bail, which relieves the police of responsibilities as outlined in the relevant regulations to conduct an investigation or notify their superiors about a death in custody. While Bai’s son died in a hospital outside the detention center, there is strong evidence, described below, that authorities had neglected his condition until it was too late.

Jiang Yiguo, the daughter of a detainee in her 60s, said it was unclear if the police conducted an investigation into her mother’s death:

I don't know if they have done any investigation. [I only read in] the forensics report [which they gave us] that the forensic examiner asked the detention center doctor a few questions out of formality.[167]

Ao Ming, the son of a detainee in his late 60s told Human Rights Watch that he was kept in the dark by the police about his father’s death:

What investigation? They didn’t investigate!... They didn’t give us any information, just told us to sign to approve for his cremation.[168]

When families asked to see the standard surveillance video meant to be taken of all detainees in their living quarters, police did not allow them to watch all the surveillance footage. Jiang Yiguo told Human Rights Watch:

They only let us watch the beginning and the end of the surveillance video in the detention center, and didn't show us the middle. They said that they have regulations and we are not allowed to see the whole video.[169]

Ao Ming said:

They let us watch the surveillance video of the 30 minutes before he died. I saw that he couldn’t walk properly. I told the police that I want to see more video footage, but they said I could only view them upon application. But they said family members cannot make that application, only our lawyers can. But the police threatened our lawyer [and he then quit], so how were we supposed to make an application [to see the video]?[170]

Xiao Li, daughter of a detainee in his 40s, told Human Rights Watch that the detention center showed her a video of her father, which showed signs of abuse by a fellow detainee suspected to be a cell boss, but it refused to give her footage of the area where he was beaten:

At the beginning they said there was no camera in that area. But eventually we went into the detention center, we saw … that there was a camera there but it had been ripped out, and a smaller one that would have monitored my father. I found the camera but they wouldn't show us the videos. After we pointed that out, they changed their words and said, “That's right, we didn't save the videos [you want].”[171]

All of the families told Human Rights Watch that authorities conducted autopsies on the bodies either on the authorities’ own initiative or following the families’ requests, but two families said they had been reluctant to authorize autopsies because they distrusted the police to conduct them impartially.