Summary

In March and April 2015, the Iraqi government achieved a significant military victory against the Islamic State, also known as ISIS, when its forces dislodged the extremist armed group from the city of Tikrit and other areas of Salah al-Din governorate, northeast of Baghdad. The forces involved in these operations included the Iraqi army and Federal Police, government-backed militias, and aerial support provided by an international coalition led by the United States.

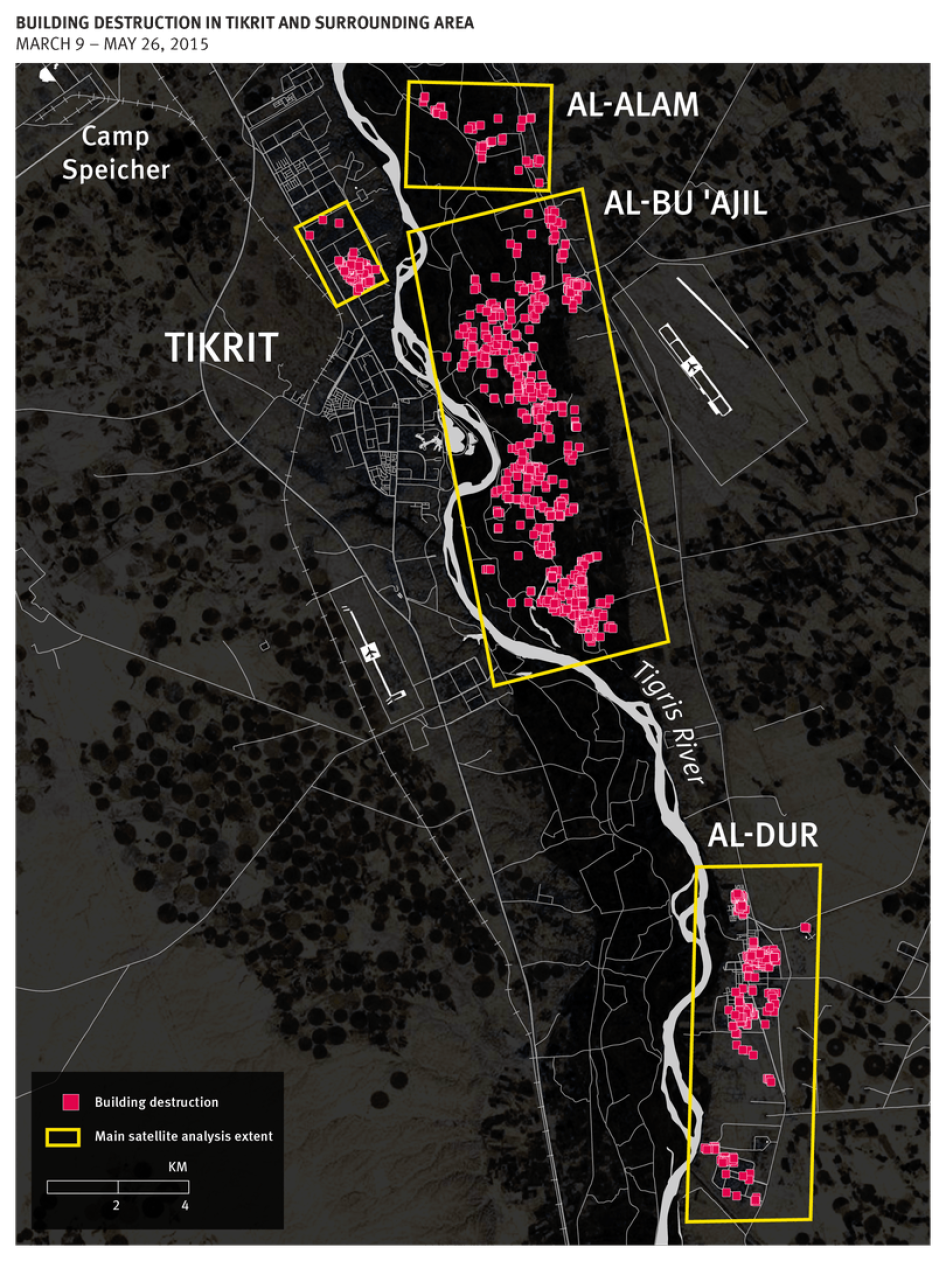

In the aftermath of the fighting, militia forces looted, torched, and blew up hundreds of civilian houses and buildings in Tikrit and the neighboring towns of al-Dur, al-Bu ‘Ajil and al-Alam along the Tigris River, in violation of the laws of war. They also unlawfully detained some 200 men and boys, at least 160 of whom remain unaccounted for and are feared to have been forcibly disappeared.

The largely Shia militias responsible for the brutal aftermath to the fighting included the Badr Brigades, the Ali Akbar Brigades, the League of the Righteous (Asa’ib Ahl al-Haqq), the Hizbollah Battalions (Kata’ib Hizbollah), the Khorasan Companies (Saraya Khorasan), and the Soldier of the Imam (Jund al-Imam). In the town of al-Alam, local Sunni volunteer forces carried out the destruction. Together, these militia forces make up the so-called Popular Mobilization Forces (al-Hashd al-Sha’bi), created in response to ISIS’s takeover of the northern city of Mosul on June 10, 2014.

The pattern of unlawful destruction is similar to that carried out by some of the same militias around the town of Amerli in Salah al-Din governorate during a three-month period from September to December 2014, after breaking the ISIS siege of Amerli.

Human Rights Watch investigations found no lawful military justification for the mass destruction of houses in Tikrit and surrounding areas. Before the operations, in February 2015, Qais al-Khaz’ali, leader of the Shia League of the Righteous, told a large crowd that he “promises victory in the battles [in Salah al-Din,] to take revenge and establish justice.” Some prominent Shia Iraqis alleged that many Sunni residents had made common cause with ISIS forces that had taken over their region and therefore shared responsibility for the June 2015 massacre by ISIS of up to 1,700 Shia military cadets from Camp Speicher, just north of Tikrit.

In December 2014, following international criticism of militia abuses during the operations to retake the town of Amerli, Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi promised to bring the militias—formally part of the Popular Mobilization Forces but in practice independent actors—under state control. The massive unlawful destruction of houses following the recapture of Tikrit shows that reining in the militias and holding accountable those responsible for crimes remains an urgent priority. The Iraqi cabinet on April 7 formally recognized the Popular Mobilization Forces as state security forces directly responsible to the prime minister, who is commander-in-chief, but Iraqi authorities have not made available any details indicating increased command responsibility and very limited accountability for past crimes.

Reasserting the authority of government institutions over areas now under militia control is crucial to persuading tens of thousands of displaced Sunnis from Salah al-Din to return to their homes. While the first few thousand residents have returned to Tikrit, residents from al-Dur and al-Bu ‘Ajil have not yet done so. Those interviewed told Human Rights Watch that they were fearful of further militia retaliation, and without a governmental rebuilding plan many have no home to return to.

***

The extensive destruction of property documented in this report was preceded by grave abuses that ISIS perpetrated during its nine-month rule over these areas, beginning in June 2014.

On June 12, 2014, ISIS forces systematically executed several hundred Shia army recruits stationed at Camp Speicher. Human Rights Watch interviewed a survivor and, using ISIS videos and satellite imagery, located three sites where the killings took place and determined that the number killed was at least between 560 and 770; ISIS claimed they had killed 1,700 men. According to residents from Tikrit and the surrounding areas interviewed for this report and ISIS footage, ISIS forces also executed dozens of local residents accused of being spies for the Iraqi government in Tikrit city, al-Dur, and al-Alam.

Even before its takeover of Tikrit and the surrounding area, ISIS engaged in extortion from business people and assassinated state security officers. After ISIS took control, its operatives demanded “repentance” from serving security officers in exchange for promising to remove them from their list of wanted persons. ISIS established its version of Sharia (Islamic law) courts, whose judges imposed death sentences without a semblance of fair trials. Transgressors who smoked or whose female family members did not veil properly received lashings.

ISIS forces had entered Tikrit and surrounding towns without a fight raising suspicions in Baghdad that local residents were complicit with the group. Some residents told Human Rights Watch that many of them did indeed initially welcome ISIS because of years of alienation from the Shia-dominated government of former Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki. But they said people quickly fell out with ISIS, and by February 2015 the majority had left their towns.

As a matter of international law, the destruction meted out in the aftermath of the recapture of Tikrit and nearby towns was illegal regardless of the attitude of the population towards ISIS or past activities of individuals.

In Tikrit city and al-Bu ‘Ajil as well as in the nearby towns of al-Dur and al-Alam, satellite imagery analysis corroborated residents’ accounts of large-scale destruction after the defeat of ISIS. ISIS had destroyed some buildings before they were pushed out and some buildings were destroyed or damaged during military clashes. After the recapture of the area Iraqi government forces and militias used technical teams to defuse or blow up what they said were hundreds of improvised explosive devices (IEDs) that ISIS placed on roads and in buildings to slow their advance. Some damage may therefore be attributed to setting off these IEDs. However the scale and nature of the destruction, with scores of entire houses collapsed, point to the use of more powerful explosives used in a systematic way.

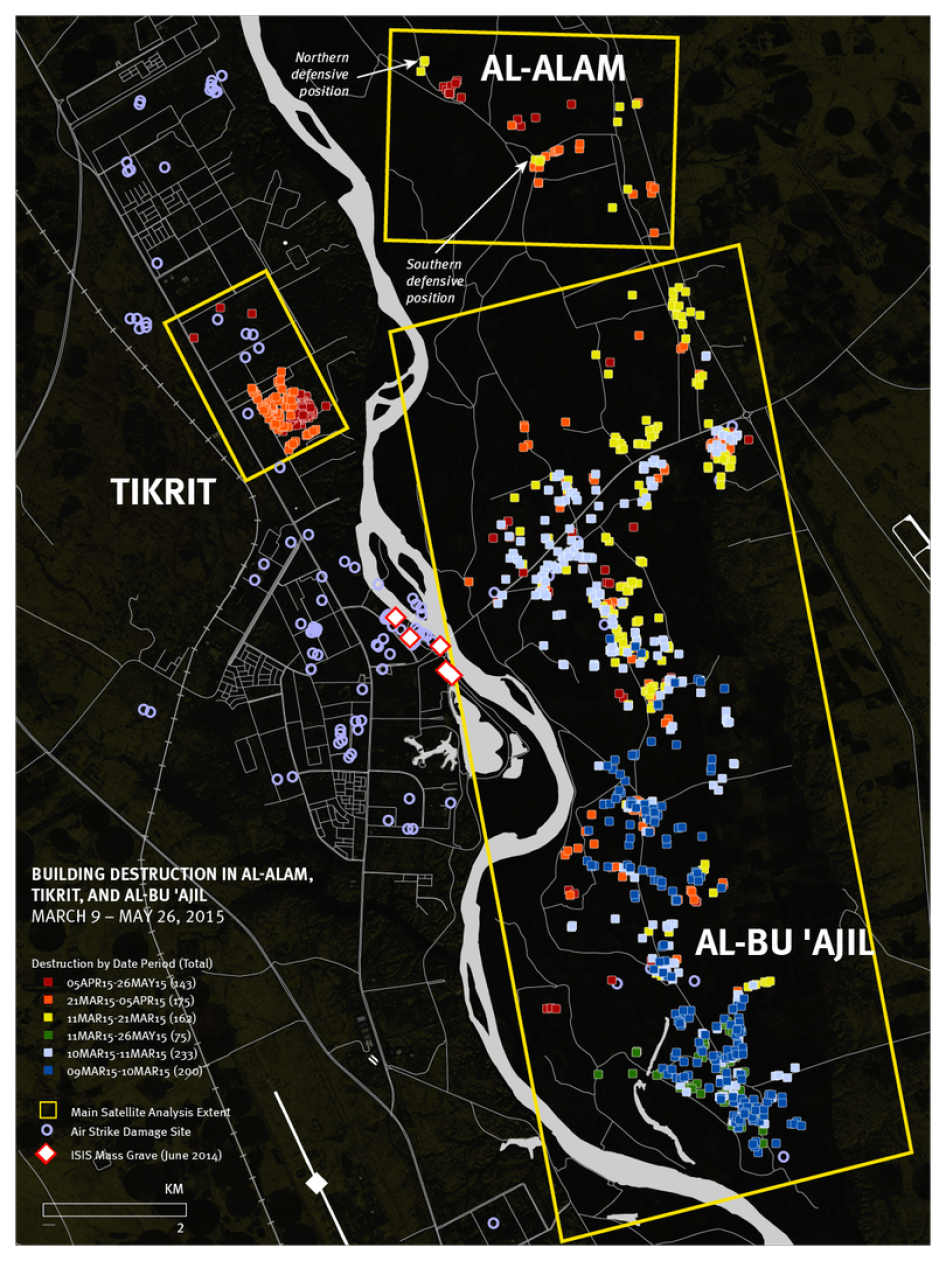

Based on a time-series analysis of eight satellite images recorded from December 28, 2014 to May 26, 2015, Human Rights Watch identified a total of at least 1,425 buildings likely destroyed by forces of pro-government militias in Tikrit and al-Bu ‘Ajil, and in al-Dur and al-Alam in the aftermath of the recapture of the area. Of this total, approximately 950 buildings were likely demolished with high explosives and a further 400 destroyed by fire.

Because fire-related damages often are limited to building interiors that cannot be identified in satellite imagery, it is likely that the total number of buildings damaged or destroyed by fire in the towns Human Rights Watch assessed with satellite imagery have been significantly underestimated. This observation is further supported by the extensive number of photographs obtained by Human Rights Watch that show multiple instances of severe fire damage to the interior of residential and commercial buildings that Human Rights Watch has been able to identify and locate.

The visual signatures of buildings destroyed with high explosives (as identified in satellite imagery) included the complete structural collapse (“pancaking”) of large, multi-story concrete buildings, generally intact rooftops, and large debris fields. These signatures are consistent with the detonation of high explosives in quantities substantially larger than typically deployed in IEDs widely used by ISIS.

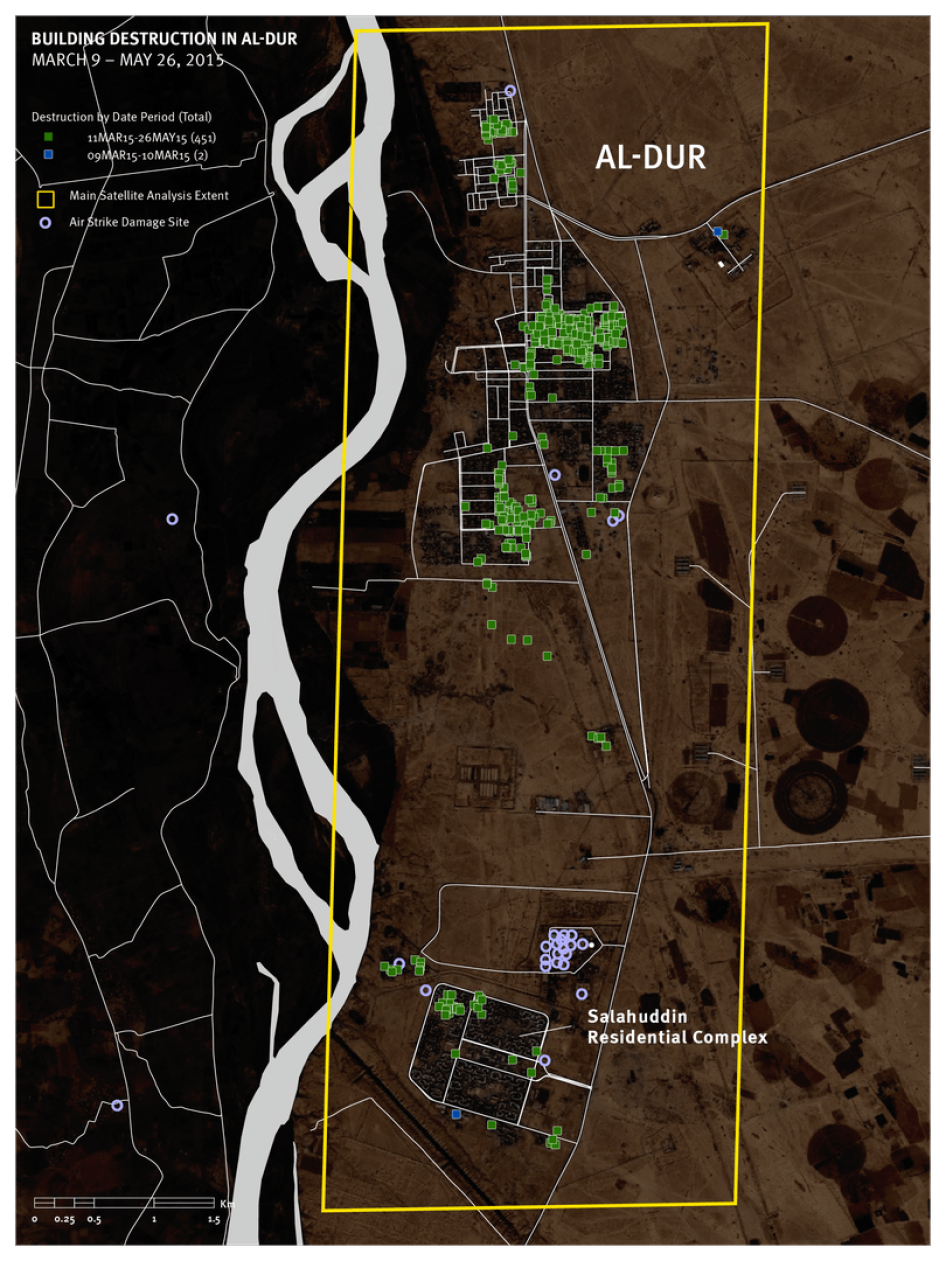

Al-Dur

Starting on March 6, Iraqi armed forces quickly took over al-Dur, south of Tikrit, with little ISIS armed resistance, according to local residents. The army advanced north toward al-Bu ‘Ajil the next day. A video showing the arrival of the Hizbollah Battalions, one of the Shia militias, in al-Dur on March 8 shows largely intact buildings along the main street. Satellite imagery taken at intervals beginning on March 9 shows large areas of the town destroyed. Satellite imagery recorded on May 26 shows evidence of the widespread destruction of over 400 buildings in residential neighborhoods of al-Dur, including the Salah al-Din Residential Complex in southern al-Dur.

Residents and local policemen who returned to al-Dur three weeks after its capture described to Human Rights Watch scenes of destruction, including arson and the blowing up of shops and homes. A group of four al-Dur residents provided Human Rights Watch with a list of 520 houses demolished, 430 torched houses, and 95 damaged shops. Human Rights Watch separately obtained photographs of 40 destroyed homes.

Al-Dur residents identified the Hizbollah Battalions as mainly responsible for the destruction.

Although ISIS had destroyed some properties and artillery shelling and coalition aerial bombing caused further damage, residents’ comments and satellite and video imagery indicate that the damage from these causes was limited. The destruction visible on satellite images and photos from after the militia takeover is consistent with accounts of homes destroyed by high explosives, rather than air-dropped bombs or artillery.

Given the absence of ISIS forces, and no perceived risk of imminent counter-attack, there was no discernible military necessity for the large-scale destruction of property that took place following the takeover of al-Dur.

Al-Alam

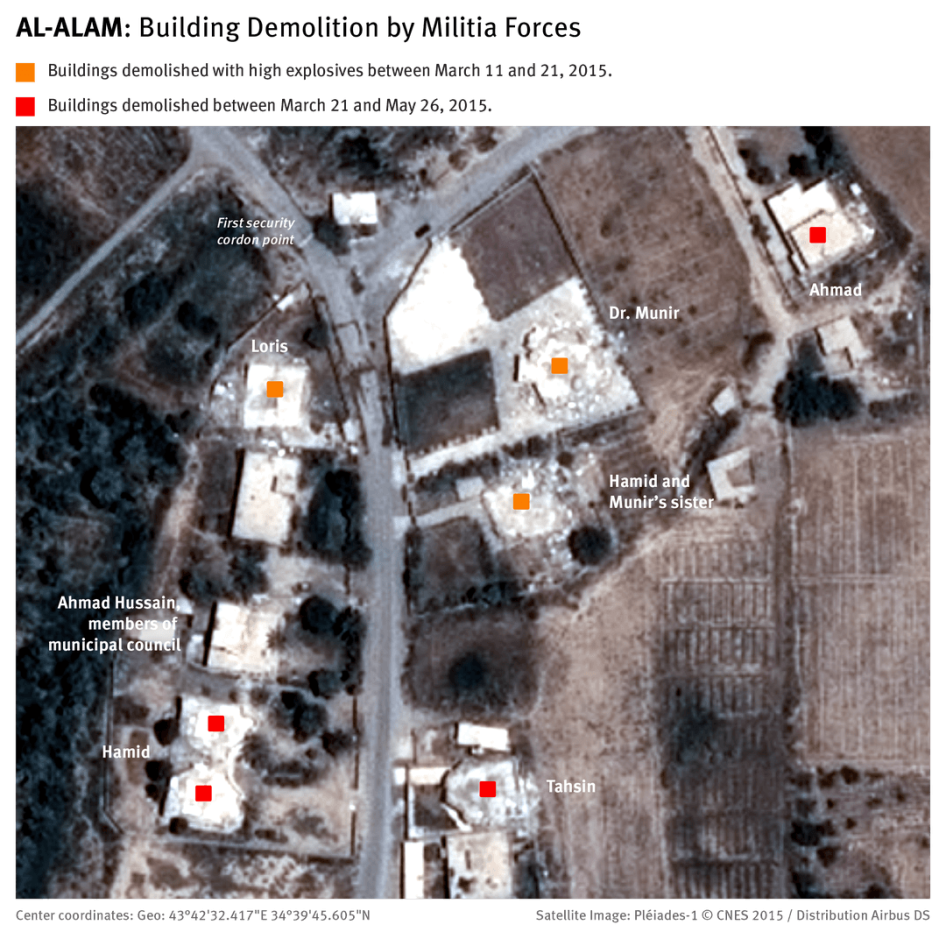

In al-Alam, a few kilometers north of Tikrit on the eastern bank of the Tigris River, Sunni local volunteer fighters operating under the protection of Shia militias blew up and torched about three dozen houses, according to tribal leaders and local residents.

The local tribal council in al-Alam (composed of Sunnis), in a public declaration, stated: “The sons of al-Alam themselves carried out the destruction of houses” of people suspected of collaboration with ISIS. A leader of the volunteer fighters told Human Rights Watch that these home demolitions occurred in a different area from those carried out by ISIS months earlier.

The 28 destroyed homes for which Human Rights Watch obtained information lie in a southern rural subdistrict of al-Alam called al-Ali, an area that local residents said played a significant role in the battle for al-Alam in June 2014. Al-Ali lies between a southern point of the town that al-Alam residents tried to defend against ISIS, and a northern point, to which the local fighters receded after accusing local residents of enabling the ISIS advance.

Local fighters destroyed the houses of several al-Ali residents, even though they had left soon after ISIS took control of al-Alam in June 2014 and had not since returned. Branded as ISIS collaborators with their houses destroyed, al-Ali residents who spoke with Human Rights Watch said they remained fearful of returning and facing personal attacks.

Human Rights Watch examined satellite imagery recorded in March, April and May after militia forces captured al-Alam and found evidence that at least 45 buildings were destroyed during this period, including those properties of local residents interviewed by Human Rights Watch that were demolished or exhibited arson damage visible from space in satellite imagery. Of this total, 30 buildings were likely demolished with high explosives and a further 15 destroyed by fire consistent with arson.

Tikrit

The battle to oust ISIS from the city of Tikrit lasted all of March, and sporadic fighting continued even after Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi declared victory on April 1. The US-led coalition bombed parts of the city during the campaign to drive out ISIS and residents said that ISIS forces also destroyed buildings.

Satellite imagery as well as publicly available US and Iraqi aircraft videos reviewed by Human Rights Watch corroborated residents’ accounts that most building destruction in the weeks before the recapture of the city was limited to specific areas of the city, and was the result of targeting mostly military objectives, specifically buildings in and adjacent to the presidential palaces which ISIS occupied earlier in June 2014. Human Rights Watch identified over 75 distinct impact sites in Tikrit with signatures consistent with the use of large, air-dropped munitions occurring between early February and late March 2015.

Human Rights Watch reviewed satellite imagery recorded on March 21 and on April 5—the period in which Iraqi military and allied forces captured the city—and found evidence of 75 destroyed residential buildings destroyed in this period in the al-Qadisiyya neighborhood in northern Tikrit, home to present and retired Iraqi military officers and an ISIS stronghold in the battle for the city. All of the buildings had damage signatures consistent with the use of large quantities of high explosives, and contextual analysis, including the number of coalition sorties during that period and the proximity of the 75 destroyed buildings to others destroyed later, suggests their demolition by explosives on the ground.

Satellite imagery recorded on May 26, less than two months after the defeat of ISIS in Tikrit, shows an additional 90 residential buildings were likely demolished with high explosives in the same area of al-Qadisiyya, sometime after the morning of April 5.

A local security guard who returned on April 2 said he counted more than 200 houses destroyed, and many more stores burned and looted in the two weeks of his deployment throughout Tikrit. Much of the destruction took place in the northern Qadisiyya neighborhood. Two police officers told Human Rights Watch they personally witnessed militias torching private homes after clashes with ISIS had ended.

Officials and residents in Tikrit also alleged that the militias were involved in widespread looting and extrajudicial killings. A policeman told Human Rights Watch that he witnessed some two dozen ISIS fighters surrender in Qadisiyya. He said forces of the Badr Brigades and the League of the Righteous separated the prisoners into groups, and each militia executed some of them on the spot. His account reflects similar events elsewhere in the city at the same time. On April 3, Reuters correspondents also witnessed an extrajudicial killing by Federal Police officers.

Human Rights Watch identified 75 separate smoke plumes from active building fires in the district of al-Bu ‘Ajil, which lies on the other side of the Tigris from Tikrit, in satellite imagery recorded on the mornings of March 9, 10 and 11, 2015, consistent with allegations of a widespread campaign of arson. In at least seven separate locations in al-Bu ‘Ajil, Human Rights Watch further identified large concentrations of mixed civilian and military vehicles (possibly including main battle tanks and armored personnel carriers) in the immediate vicinity of active building fires and freshly demolished buildings on the mornings of March 9, 10 and 11, evidence of the active presence of militia and government military forces at the time of widespread arson and building demolitions.

Arbitrary Detention and Enforced Disappearance

Human Rights Watch received accounts of militias or government forces arbitrarily detaining persons in Jallam al-Dur, a rural area east of al-Dur, where some remaining residents of al-Dur had fled just before the entry of government and allied forces. Two people described to Human Rights Watch the apprehension and detention of some 200 men and boys around March 8 by the Hizbollah Battalions and the League of the Righteous. At time of writing, more than 160 of the men and boys remained missing and unaccounted for, and appear to have been forcibly disappeared.

The government has not responded to calls by Dhiya al-Duri, a local member of parliament, to investigate the whereabouts of these men and boys.

***

The large-scale destruction of civilian property by pro-government militias detailed in this report was in apparent violation of international humanitarian law—the laws of war. The laws of war prohibit deliberate attacks against civilian objects, that is, objects not being used at the time for military purposes. The laws of war specifically prohibit the destruction of the property of an adversary, unless required by the imperative of military necessity. Human Rights Watch found no evidence that the destruction met the requirements for military necessity, but instead occurred after fighting had concluded in the area and when ISIS had fled, and renewed fighting was not imminent.

Serious violations of the laws of war committed with criminal intent are war crimes. Possible war crimes include unlawful destruction of property, collective punishment, and forced displacement. Those responsible include not only direct participants in the criminal acts but commanders implicated as a matter of command responsibility.

The Iraqi government’s failure to disband or establish effective command and control over the militias and bring those responsible for unlawful property destruction and other abuses to justice has had grave consequences. It signals to the Sunni residents of these areas that their fear of returning to an area under unchecked rule of militias is justified. It also bodes ill for the communities of Anbar and Nineveh province now under abusive ISIS rule, since Prime Minister Abadi has ordered the Popular Mobilization Forces to take part in the campaign to retake these provinces.

The United Nations as well as the United States, Iran, and other countries involved in the conflict in Iraq should publicly condemn militia abuses in the armed conflict with ISIS and press the Iraqi government to fully and impartially investigate alleged war crimes by militia forces. The UN Human Rights Council should extend the mandate of its fact-finding commission and include militia abuses.

In light of abuses by Iraqi pro-government militias documented in this report and elsewhere, the United States, Iran and other countries providing military assistance to Iraq should urge and support Iraq to undertake concrete and verifiable reforms to hold perpetrators of serious abuses accountable, integrate pro-government militias into a centralized command structure subject to civilian oversight and control, and ensure that those forces fully adhere to international humanitarian law. These countries should require Iraq to report publicly within one year on progress towards implementing these reforms, after which they should suspend military assistance and sales commensurate with Iraqi compliance gaps on those reforms.

Recommendations

To the Iraqi Government

- Take immediate steps to establish effective command and control over pro-government militias; disband militias that resist government control;

- Ensure that members of the Iraqi security forces, including all militias, implicated in violations of international humanitarian law and human rights law, are fairly and appropriately disciplined or prosecuted. This includes military commanders and civilian officials responsible for abuses as a matter of command responsibility;

- Immediately take all necessary steps to end unlawful destruction of and damage to houses and other civilian property for whatever reason by militias and state security forces;

- Provide adequate compensation or alternative housing to residents whose homes have been unlawfully destroyed by Iraqi security forces or pro-government militias;

- Ensure humanitarian agencies have prompt and unfettered access to all civilians in need, including those in urgent need of housing;

- Facilitate immediate and unhindered access to all government-controlled areas, including those held by militias, to journalists, independent human rights monitors, and UN agencies, including the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights and the UN Human Rights Council Investigative Committee on Iraq;

- Accede to the Rome Statute so that grave crimes in violation of international law committed in Iraq fall under the jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court. Iraq should also file an article 12(3) declaration under the Rome Statute to give the ICC retroactive jurisdiction.

To the UN Human Rights Council

- Extend the current mandate of the Investigative Committee on Iraq and ensure it includes violations of the laws of war and human rights abuses committed by all sides, not only by ISIS and associated groups;

- Establish a mandate of Special Rapporteur on the situation in Iraq, in order to monitor the grave situation of human rights in the country and make recommendations on measures to prevent violations and ensure accountability.

To the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights

- Support prompt and thorough investigations by the UN Assistance Mission in Iraq into alleged war crimes committed by all parties to the conflict and support the publication of its findings and recommendations in a timely fashion.

To the United States, Iran, and Other Countries Providing Military Assistance or Sales to Iraq

- Urge Iraq to undertake concrete and verifiable reforms to bring an end to serious militia abuses by holding perpetrators of serious human rights violations accountable; progressively integrating the militias into a centralized command structure, subject to civilian oversight and control; and ensuring that those forces fully adhere to international humanitarian law;

- Require Iraq to report publicly in one year on progress towards implementing these reforms, after which suspend military assistance and sales commensurate with Iraqi compliance gaps on those reforms;

- Amend relevant legislation authorizing and appropriating security assistance and military sales or transfers to Iraq to ensure, with no waiver language, that it provides for:

- Reform benchmarks for the Iraqi government, such as integrating under central government command all militias operating outside the effective control of the Iraqi security forces; ending security force abuses, including enforced disappearances and torture; and releasing prisoners held on politically motivated counterterrorism charges;

- Explicit end-user documentation and post-shipment controls to minimize the transfer of weapons and equipment to abusive forces;

- Clear vetting of recipients of security assistance to exclude those with credible indications of involvement in serious abuses;

- Ensure that embassies of arms-providing countries in Iraq have sufficient financial, technical, and personnel resources to undertake robust human rights vetting of all recipients of military aid, foreign military sales, and security assistance and that the ambassador, defense attaches and political counselors undertake regular joint monitoring visits to security force training sites to assess training effectiveness, including on human rights;

- Publicly report on the end-use of military transfers and vetting of forces participating in training, including end-users involvement in violations of human rights or international humanitarian law, and any steps taken to address this;

- Countries and UN agencies providing financial assistance or expertise for security sector reform in Iraq, including accountability for past abuses, should publicly report on their goals related to human rights and international humanitarian law, means of measuring progress, and evaluations of future support should those goals not be met;

- Urge Iraq to join the International Criminal Court or to voluntarily accept temporary jurisdiction of the court over the current situation.

Methodology

This report is based on interviews with 29 people from Tikrit, al-Dur, al-Alam and al-Bu ‘Ajil. We conducted 20 of the interviews in person between April 27 and May 7, 2015 in Erbil and Sulaimaniya in the semi-autonomous Kurdish region in Iraq, and in the city of Kirkuk, which lies 120 kilometers northeast of Tikrit and nine by telephone between May and July 2015. Most of those interviewed had sought refuge in the Kurdish region and Kirkuk during or shortly after the takeover of their towns by ISIS, others had left around the time of ISIS’ defeat. Human Rights Watch researchers did not visit Tikrit or the other towns covered in this report because only security personnel and select media received permission to visit at the time.

Nearly all interviews were conducted in Arabic. We informed all interviewees about the purpose and voluntary nature of the interviews, and the ways in which the information would be collected and used, and obtained consent by all interviewees, who understood they would receive no compensation for their participation. Due to the risk of reprisals, Human Rights Watch has withheld the names and identifying information of several persons interviewed, in particular those of police officers.

Human Rights Watch obtained over 100 photographs of damaged buildings and worked with residents to identify their location. Researchers spoke to the persons who had taken the photos in most instances to verify that the houses depicted were in the areas under scrutiny.

Human Rights Watch conducted a detailed damage assessment of Tikrit and the towns of al-Alam, al-Bu ‘Ajil and al-Dur using a time series of eight very high resolution commercial satellite images recorded between December 28, 2014 and May 26, 2015, before, during and after the destruction, and was able to locate and identify several of the photographed houses, verifying their destruction.[1] We used satellite imagery to identify areas of destruction, quantify damage levels, evaluate witness statements, and assess the scale, distribution, and timing of the destruction of buildings. Further, we used satellite imagery to determine the probable methods of destruction, locate deployments of militia and government military vehicles in areas of active destruction, as well as to control for damage from airstrikes and possible heavy artillery and mortar fire that occurred before March 6, during the battle for the areas between ISIS and pro-government forces.

Human Rights Watch also reviewed videos obtained from social media sites purportedly recorded by militia forces after capturing the towns of al-Dur and al-Bu ‘Ajil, as well as publicly available US and Iraqi airstrike footage over Tikrit to better assess airstrike-related damages and technically identify the likely type of high explosives used by militia forces to demolish buildings identified in this research.[2] To help verify the probable time, location, and context of the videos, Human Rights Watch matched visible landmarks in the videos with satellite imagery and available ground photographs from local residents whenever possible.[3]

Human Rights Watch presented its basic findings to the Iraqi government in a letter requesting information on July 17, 2015, requesting a response by August 10. As of August 24, we had received no response.

I. ISIS Abuses in Salah al-Din Province

ISIS was responsible for numerous serious violations of the laws of war and human rights abuses during the nine months it held Tikrit, al-Alam, al-Dur and other areas in Salah al-Din province.

Among the most notorious ISIS atrocities was the mass execution of at least 770 Shia recruits from the Camp Speicher military facility just north of Tikrit city in June 2014, in the days immediately after the takeover. ISIS itself claimed it executed 1,700 men from Camp Speicher and the government says it has retrieved the remains of close to 600 bodies.[4]

During its control of the province, ISIS frequently carried out summary executions. Victims include alleged spies, non-Muslims, LGBT persons, and others.[5]

In al-Alam, ISIS on December 15, 2014, publicly executed 13 people, mostly men from al-Alam, but also from Tikrit and al-Dur.[6] They were among large groups of people from the area that ISIS fighters arrested beginning in October 2014 and allegedly tortured at their headquarters in Tikrit’s presidential palaces.[7] According to media reports and one resident, whose brother was among the detainees and who spoke with Human Rights Watch, ISIS suspected them of forming a clandestine resistance and providing coordinates on ISIS locations to government forces carrying out aerial bombing against ISIS.[8] ISIS also executed seven people from al-Alam between November 2014 and February 2015.[9]

In Tikrit, ISIS carried out executions in addition to the Camp Speicher massacre. Several witnesses told Human Rights Watch that on June 12, 2014, one day after ISIS took the city, four local security officials and their driver tried to leave Tikrit. Only the driver returned, with the bodies of the four officers who had each been shot in the head. One of the witnesses said he recognized two of the dead men as his neighbors from the Rajab family, and delivered their bodies to their families before helping the driver escape.[10]

Sheikh Dhiya Muhsin, a Sunni tribal leader from al-Dur, provided Human Rights Watch with a list of four persons from al-Dur whom he said ISIS executed between December 2014 and February 2015: ‘Abd al-Jabbar Ali al-Hindi, Sufyan Thabit Nu’man, Yasir Namis Dahham, and Marwan Habib Sa’id, and names of a further nine people whom he said ISIS arrested and who have not been heard from since.[11]

Sunni Muslims from al-Dur, Tikrit and al-Alam told Human Rights Watch that many residents of towns in Salah al-Din province welcomed the arrival of ISIS, or at least gave the impression that they did. “They entered and took the city by the sound of a car horn,” one resident of al-Dur said.[12] Local security forces had abandoned their posts in haste after news spread on June 10 that Mosul had fallen. “The police chief left with his guards in the late afternoon,” a policeman from al-Dur told Human Rights Watch. “Then we all disbanded. There was no fighting against ISIS in al-Dur. ISIS numbered in the hundreds at most.”[13] According to one Tikrit businessman, ISIS fighters presented themselves as “revolutionaries” in support of the Sunni population long marginalized by the Shia-dominated government of former Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki.[14]

Others from al-Dur also told Human Rights Watch that the local population’s alienation from the government in Baghdad facilitated ISIS’s rapid takeover of these areas.[15]

ISIS had carried out targeted killings and engaged in extortion for months before taking over towns in Salah al-Din province. Mahmud Zaki, a teacher from al-Dur, described how a presumed ISIS sniper killed a policeman who was his relative:

On May 23, my maternal cousin was on duty at a local checkpoint, wearing his uniform. A bullet hit him, and he died. His colleagues told me that it was a sniper from a nearby rooftop, who shot him. It was only ISIS at the time killing security forces. In rural areas, ISIS maintained bunkers and weapons, and in the city had sleeper cells.[16]

Muhammad Jasim, the owner of a mall selling appliances in Tikrit, told Human Rights Watch that a few months before ISIS arrived, he received a call from an unknown person who told him: “We know you. Do what is right and pay your share. We are the Islamic State.” Jasim said a friend who runs a used car frames shop received a similar call from the same number that same day. By evening, his friend’s shop had gone up in flames because he had not paid, he said.[17]

ISIS’s initial welcome was neither undivided nor unqualified. Serving security forces and political figures knew that ISIS would likely target them as agents of the state they were fighting. A journalist, an aid worker with an international organization, and a government official with the election commission told Human Rights Watch they left Tikrit soon after the arrival of ISIS, as they knew their work would bring them into confrontation with the new authorities.[18]

Large numbers of Sunni Muslim residents left quickly and of their own volition after the arrival of the ISIS. By February 2015, all but perhaps 10 percent of the original population had deserted their homes for the apparent safety of other areas, in Baghdad, Anbar, Kirkuk, or the Kurdish region, a number of residents told Human Rights Watch.[19]

Schools and shops closed and, while essential supplies remained available, the price of gas and fuel tripled.[20]

Public life became more tightly regulated, former residents told Human Rights Watch. ISIS gradually instituted new rules based on their vision of Sharia: men could no longer meet in cafes to enjoy water pipes and games, people could no longer wear jeans and other Western clothes, and women could only leave the house with a male relative and fully veiled.[21] ISIS imposed a penalty on smoking of 500 lashes, and 50 lashes on men whose female relatives were not properly veiled in public.[22]

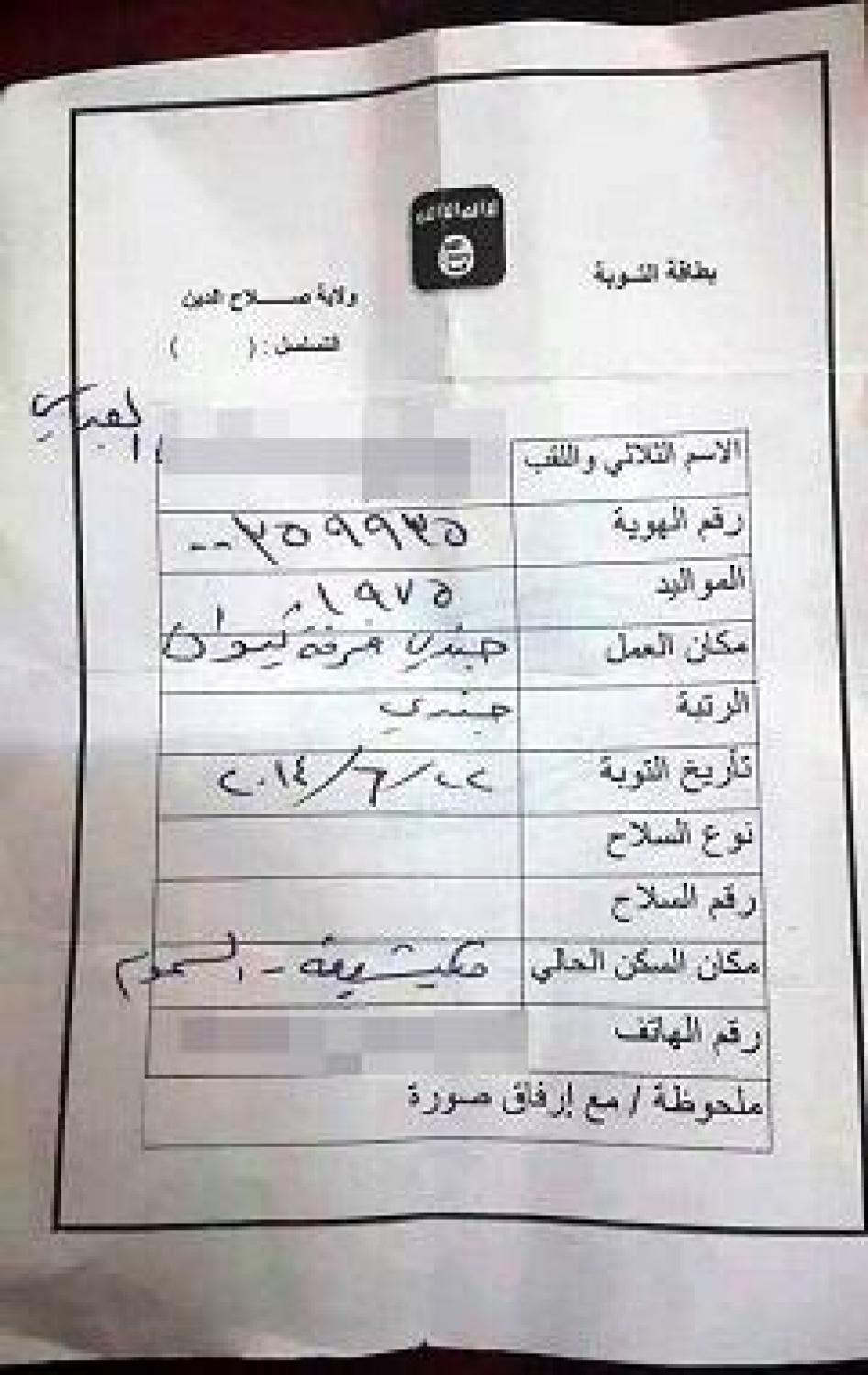

ISIS issued “certificates of repentance” for soldiers and police officers in exchange for handing in a military assault rifle and a pistol, or failing that, paying fees of up to US$2,500. Judges, judicial investigators, and lawyers had to pay lower fees. Whoever did not comply remained on ISIS’s wanted list. Local supporters of ISIS, who wore masks so that residents would not know their identities, publicly posted lists of wanted people. The lists often numbered in the hundreds and within weeks ISIS began arresting security officers.[23]

A Sunni candidate for the Salah al-Din provincial council, who lost the last election, said ISIS forces arrested him in early 2015, beat him, and brought him blindfolded before a new ISIS-appointed “Sharia judge.” The judge sentenced him to death for his political activity, but the intercession of a powerful friend saved him, he said, and he was released.[24]

Some residents stayed despite misgivings about ISIS and in some cases worked against the armed group.[25] Sheikh Malik, brother of al-Dur’s mayor, told Human Rights Watch that he helped rescue five survivors of the Camp Speicher massacre who had ended up on the banks of the Tigris, where he has a fish farm. He gave them his own sons’ identity documents, he said, and drove them to safety through desert roads at night.[26]

Sheikh Malik said he left al-Dur in early August 2014, and his son Marwan in late September, after ISIS had damaged, but not destroyed, his house. He said tribal leaders from al-Dur volunteered their tribesmen to fight to retake the town, but that Faleh Fayyad, the head of national security in the government, Hadi al-Ameri, head of the Badr Brigades, and Qais al-Khaz’ali, head of the League of the Righteous forces, declined the offer in January 2015.[27]

After ousting ISIS in early March 2015, Shia militias destroyed his house and stole large quantities of cash and gold from a safe he kept, Sheikh Malik said, showing pictures a local policeman had sent him on April 11 of his house and the smashed safe.[28]

A combination of forces of the Iraqi army, the Federal Police, Shia militias and other Popular Mobilization Forces that had slowly fought their way up the Tigris captured al-Dur on March 6, and later the rural town of al-Alam around March 8, before circling back to Tikrit from the north and chasing the remaining ISIS fighters out.

On April 1, Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi visited Tikrit and declared victory over the ISIS fighters. Then, as in al-Dur after March 6 and in al-Alam after March 8, residents alleged that the Shia militias began razing the towns apparently in revenge for perceived support for ISIS and in order to settle old scores against Sunni officers who served under Saddam Hussein.

II. Destruction of Civilian Property

Al-Dur

Al-Dur lies 20 kilometers to the south of Tikrit on the east bank of the Tigris. The town had a population of about 120,000.[29] Al-Dur was captured by ISIS on June 11, 2014, and was retaken by the Iraqi army on March 6. However the army withdrew one or two days later, leaving the town to militias in the Popular Mobilization Forces.[30] These militia fighters laid waste to much of the town, apparently because they believed residents had made common cause with the ISIS insurgents.

Sheikh Malik, a prominent businessman and brother of al-Dur’s mayor, told Human Rights Watch that at a tribal gathering he attended in April 2015, a Tikriti member of the Popular Mobilization Forces (a Sunni) boasted that, “We burned and destroyed al-Dur, because they [the residents] are ISIS and Baathists.”[31] In a video posted in March 2015, a person in a car filming a ride through al-Dur says of a local mosque: “This is the mosque of the dogs.”[32] In another video posted in March, a man calling himself Abu Nimr and invoking Ali, the son-in-law of the prophet Mohammed, (the first in the line of revered Shia imams), proceeds to blow up a house with a bomb, saying “this is one of the houses of Dawaesh,” using the plural form of the Arabic acronym for ISIS.[33]

In the complicated web of historical animosities playing out in the current conflict in Iraq, Shia political rhetoric tends to lump together supporters of ISIS with forces loyal to the disbanded Baath party and with retired senior officers who had served under Saddam Hussein.[34] In line with this rhetoric pro-government forces engaged in military operations against ISIS appear to have conflated ISIS with the Baath party. A pro-government reporter with Al-Ittijah channel in al-Dur during the recapture of the town told viewers that “Baathists and ISIS are two sides of the same coin.”[35]

Analysts of ISIS have indeed pointed to the significant role former Baath party members play in it.[36] However many other former Baathists, some of whom Human Rights Watch interviewed, claim to have no connection to the extremist group.[37]

Among the Shia militias’ targets of destruction in al-Dur were opulent houses belonging to former Iraqi army officers.[38] Senior officers serving in the 1980s and 1990s likely were Baath party members and participated in the 1980-1988 war against Iran.[39]

Revenge for the Camp Speicher massacre was a clarion call for Shia militias fighting to take back villages, towns and cities across Salah al-Din province from ISIS. A video of the remote detonation of a palace of Izzat al-Duri, vice-president under Saddam Hussein, shows militiamen invoking Shia slogans, shouting “Ya Zahra, Ya Hussein.”[40] The video is dated March 24, 2015, more than two weeks after the army, militias and local forces ousted ISIS fighters, and shows a militiaman saying to the camera: “This is a gift for the martyrs of Speicher, for all the martyrs left on the soil of the nation.”[41]

Extent of Destruction in al-Dur

Estimates of the extent of the destruction of houses by arson or explosives in al-Dur vary. There appears to be no definitive list of damaged and destroyed buildings. Residents of al-Dur who fled to the Kurdish region have compiled a list of damaged buildings, including 520 houses destroyed, 430 torched houses and 95 damaged shops.[42] Others, including police officers who had returned to al-Dur, tallied the destruction at 660 houses and 450 shops and government offices based on records they compiled on their patrols of the town.[43] Human Rights Watch obtained photographs of 40 destroyed residential homes, as well as photographs of some of these houses before their destruction, and was able to locate the houses in those pictures on a map. Satellite imagery taken after the recapture of al-Dur also shows those houses destroyed, in addition to significant destruction and damage in other parts of the town.

Human Rights Watch has compared photos and videos taken at the time government forces re-took al-Dur with others taken over the following six weeks, after the army withdrew. Imagery at the time of recapture comes from satellite pictures, television coverage, and videos by militiamen. Imagery of later destruction comes from satellites and private photographs and videos taken by al-Dur residents, mostly local policemen. The photos, videos, and satellite imagery shows progressive destruction on a large scale in the weeks following al-Dur’s recapture by Shia militias.

Qasim, a policeman from al-Dur who spent two weeks in the town in early April, told Human Rights Watch that early in his tour that started on April 2, he saw the house of Ra’id Ghayyath intact, only to find it burning two hours later when he passed by again, without any military activity taking place. Another day, he said, he passed by a shop for car batteries that was undamaged but was burning the following day.[44]

Responsibility for Destruction

Shia militias appear to have been responsible for the destruction of property in al-Dur following the defeat of ISIS. The town was largely undamaged before they entered, and only the militias and some local police were present at the time the destruction occurred. The local police appear to be unlikely perpetrators, as they openly provided information about the destruction. In addition the Shia militia had a motive: revenge for the sectarian atrocities carried out by ISIS.

Only limited destruction of buildings took place while al-Dur was under ISIS rule or as a result of fighting. Residents of al-Dur told Human Rights Watch that ISIS blew up the police station and three houses, one belonging to the mayor, Sheikh Maqsud Shahab, and two belonging to police officers Nawfal al-Juri and ‘Adil Saqar.[45] Retired Brig. Gen. Zaki Khattab Fad’am told Human Rights Watch that on June 27, 2014, four missiles from a plane—presumably either an Iraqi government or a US airstrike—hit his house in al-Dur, collapsing it on top of him. His was one of only a few houses damaged by aerial bombing, he said.[46] Another resident said there were about 10 aerial bombings of al-Dur soon after ISIS took over in June 2014.[47]

Other sources confirmed that the town was largely intact when the army and militias recaptured al-Dur. An Al-Ittijah television broadcast accompanying the entry of Hizbollah Battalions into al-Dur on March 8, 2015, shows little damage to the dozens of buildings shown in the broadcast.[48]

Qais, who left one day before the army and militias moved in, said that most of al-Dur’s buildings were intact, although “Islamic State militants were going around with explosive jerry-cans [portable containers often used to carry fuel or other flammable liquid],” setting up booby traps in the area. “There was no major battle inside the town,” he said.[49]

Local security officials who returned immediately after Iraqi forces entered also painted a picture of a town largely unharmed. An intelligence officer who entered al-Dur with the militias as part of the Popular Mobilization Forces phoned a local policeman to say: “I am standing on your doorstep,” adding that the house was intact, the policeman told Human Rights Watch.[50] Several weeks later, when the policeman himself returned, he said he found his house destroyed.[51]

Sheikh Malik, who was in touch with senior local security officials, said that the Hizbollah Battalions entered one or two days after ISIS had already vacated the town.[52]

Human Rights Watch reviewed a video filmed by a militia member in the town of al-Dur in early March 2015. In the video, an unidentified man lights a fuse of a large white plastic container in the home of a local resident, runs outside and seconds later the residential building explodes, completely destroying it.[53]

Human Rights Watch arms experts concluded the explosive device was consistent with a makeshift fertilizer bomb composed of a detonator, propane gas tank and sacks of agricultural fertilizer, all components readily obtained locally and easily configured and deployed.

After recapturing al-Dur, the army retreated and only militias and local police remained in the town, police officers and other residents told Human Rights Watch.[54]

Human Rights Watch is unable to determine which militia or militias were responsible for particular acts of destruction. Several Shia militias participated in the capture of al-Dur, including:

The Badr Brigades, 9th “Kerbala” regiment[55]

The Ali Akbar Brigades

The Hizbollah Battalions

The League of the Righteous[56]

Several residents pointed to the Hizbollah Battalions as being behind the destruction. Sharif (pseudonym), the police officer, said local volunteer fighters who entered al-Dur with permission from Hizbollah told him that Hizbollah militiamen said the destroyed homes belonged to serving and retired officers and that they did not destroy houses ISIS had marked and occupied because “we left them for al-Dur Popular Mobilization Forces. You take care of them.”[57]

Al-Alam

The town of al-Alam lies about 12 kilometers to the north east of Tikrit on the east bank of the Tigris and in normal times has a population of about 60,000. The town borders a rural area with clusters of houses interspersed by fields that belong to the district of al-Alam which was captured by ISIS around June 24, after ISIS kidnapped families fleeing al-Alam to force local leaders to negotiate ISIS’ peaceful entry. Pro-government forces retook around March 8. The destruction of property in al-Ali, one of the rural subdistricts of al-Alam, followed a different pattern from the destruction in al-Dur and later Tikrit. In al-Ali, local Sunni volunteer fighters blew up and torched their neighbors’ houses under the protection of Shia militias.

Human Rights Watch reviewed photographs of 12 destroyed buildings and collected information on a further 16 buildings torched or blown up: 28 in all. Some of this destruction is visible on satellite imagery, which shows 45 buildings destroyed in March, April, and May, after militia forces captured the district of al-Alam, including those properties of local residents Human Rights Watch interviewed that were demolished or exhibited arson damage visible from space in satellite imagery.

Of the total of 45 destroyed buildings visible in satellite imagery, 30 buildings were likely demolished with high explosives and a further 15 destroyed by fire consistent with arson.

These 28 destroyed homes documented by Human Rights Watch lie in a southern rural subdistrict of al-Alam called al-Ali, precisely between two points of a road that local residents said played a significant role the fighting when ISIS took al-Alam in mid-June 2014.[58] Almost all houses along that stretch of road were destroyed.

In June 2014, al-Alam tribal fighters resisted ISIS, but quickly retreated from a southern defensive position to one a couple of kilometers further north (see map).[59] Between these two defensive positions lies the district of al-Ali, and after pro-government forces in March 2015 retook al-Alam, local volunteer forces accused al-Ali residents of not taking up arms to fight ISIS and of making common cause with them, three al-Ali residents told Human Rights Watch. The area also contained houses of families some of whose members later joined ISIS, they said.[60]

Officials admitted that militia had destroyed property in al-Ali belonging to suspected collaborators with ISIS and said this was a form of exemplary punishment. In a March 28 post on his Facebook page, local Sunni tribal leader Sheikh Jasim Jabbara quoted the tribal decision: “The sons of al-Alam themselves carried out the destruction of houses of those who collaborated with Islamic State and cooperated with them.”[61]

Khalil Jabbara, the Sunni head of the local volunteer Popular Mobilization Forces, told Human Rights Watch that while his forces “found many houses destroyed by Islamic State” in al-Alam, the “tribal decision” to destroy houses of “ISIS people” in the area “was implemented.”[62] Reached by phone in Baghdad, Jasim Jabbara confirmed the tribal decision, but claimed it had not been carried out. Jasim Jabbara serves as head of the security committee of the Provincial Council of Salah al-Din, an important security position in the province.[63]

The destruction in al-Ali occurred during the week of March 8, before many al-Alam residents were able to return.[64] Some al-Ali residents whose houses the local volunteer fighters destroyed had left soon after ISIS forces took over their area in June 2014 and were unlikely to have been ISIS collaborators.[65]

Some Tikrit residents had moved to al-Alam in January 2015 temporarily renting apartments because ISIS operatives were carrying out more and more arrests in Tikrit, a resident told Human Rights Watch.[66] Some of these Tikrit residents stayed in al-Alam until the Shia militias and local volunteer forces entered, and later provided accounts of houses remaining intact until then.

ISIS fighters destroyed some houses in northern al-Alam, in particular those of the Jabbara sub-clan (a Sunni family) whom ISIS fighters suspected of involvement in a planned uprising against ISIS in November 2014, several residents told Human Rights Watch.[67] Those houses lie north of al-Ali. Estimates range from 37 houses to over 100 houses destroyed by ISIS in al-Alam.[68]

There are varying accounts of the battle for al-Alam in March 2015. Some say ISIS withdrew without a fight, whereas others recounted intense battles.[69] To Human Rights Watch’s knowledge, there are no accounts of battles or aerial bombing in the southern subdistrict of al-Ali, and no evidence of battles or bombing appears in aerial imagery.[70]

The main militia forces entering al-Alam belonged to the Badr Brigades, one resident told Human Rights Watch, but League of the Righteous forces were also present, another said.[71] Khalil Jabbara, the leader of the local Sunni Jiburi fighters who joined the fight against ISIS, said his men numbered several hundred.[72]

Nur (pseudonym), a resident of al-Ali who returned shortly after the town’s recapture, told Human Rights Watch that local Jiburi forces carried out the destruction. According to Nur, a Badr Brigades leader in a meeting outside the province said explicitly that there was an agreement between Badr Brigades and League of the Righteous forces to guard the streets but leave “internal affairs” to the local Jiburi fighters.[73] One resident of al-Alam told Human Rights Watch that a Badr Brigades commander in al-Alam one day after their entry, at around the time that the house destructions took place, told three relatives who sought to return to their house in al-Ali from a farm where they had taken shelter that they could not pass while Jiburi fighters were going from house to house.[74]

Human Rights Watch received accounts of several houses in al-Ali being intact at the time the militias entered. Ra’id, (pseudonym), who left soon after ISIS took over al-Alam, said he spoke with a volunteer fighter from the ‘Azawi tribe who told Ra’id that his house remained intact. One week later, Ra’id said, friends informed him that his house and that of his sister next door had been blown up.[75] Jalal (pseudonym) said he telephoned a Tikriti friend who was staying in his undamaged house as a tenant until one day before the town’s recapture. Several days later, local friends told Jalal the house was flattened.[76]

Branded as ISIS collaborators and with their houses destroyed, al-Ali residents remained fearful of returning.[77] One victim, who filed a complaint in court against unknown parties for the destruction of his property, told Human Right Watch that the judge asked him to change “unknown parties” to “Islamic State” if he ever hoped to receive compensation.[78]

Tikrit

International media coverage of the fighting in Salah al-Din largely focused on the battle for the city of Tikrit. Tikrit city, which in normal times has a population of about 150,000, is the provincial capital of Salah al-Din province and lies on the West bank of the Tigris 180 kilometers north of Baghdad. It was captured by ISIS on June 11. During the battle for Tikrit the US-led coalition bombed ISIS targets in the city and media accounts reported intense street fighting, especially in the northern Qadisiyya area of the city. The battle lasted all of March, and sporadic fighting continued even after Prime Minister al-Abadi declared victory on a tour of the city on April 1.

Several residents of Tikrit insisted to Human Rights Watch that, apart from shelling and aerial bombing before the army and militias moved in, fighting was mainly concentrated in the Qadisiyya neighborhood.[79]

ISIS also destroyed property in Tikrit during its nine-month rule and the coalition bombing took its toll, Rami (pseudonym), a member of the Tikrit Emergency Police Force who returned in early April, told Human Rights Watch.[80] Jasim, the local businessman, said that ISIS blew up between 10 and 15 houses.[81] Amr, a security officer with the Facilities Protection Service, said he found private houses largely intact when he entered Tikrit on April 2. Over the ensuing two weeks, however, in his tours of the city he counted 279 houses destroyed by the militias, and over 400 stores burned and looted.[82] Amr said he personally witnessed a series of arson attacks and explosions.[83]

Amr said that the militias went after upper-class houses, mostly belonging to army and police officers in Qadisiyya.[84] Mahmud, who left Tikrit on the eve of the militias taking control and who said he has been in touch with 14 returned families, also indicated that almost all of the houses the militias had destroyed belonged to former army officers.[85] Fadi left Tikrit in June 2014 and has been coordinating documentation of damage to houses in Tikrit through a network of people who have gone back. He said that his sister’s house in the Martyrs’ area of Qadisiyya had been blown up after the arrival of the militias, as had the nearby house of Shahin Yassin, an Iraqi air force commander until his retirement in 2001.[86]

Rami said he witnessed one militia, the Khorasan Companies, burn down a house in Tikrit:

They burned down the house of an Iraqi policeman right in front of my eyes. I said to them, “But it belongs to a policeman,” and the militiamen replied, “Mind your own business.”[87]

Satellite imagery as well as publicly available videos taken from US aircraft operating as part of the anti-ISIS coalition reviewed by Human Rights Watch confirmed residents’ accounts that most of the destruction of buildings in the weeks before the recapture of the city was limited to specific areas of the city.[88] Coalition attacks on Tikrit during the battle struck mostly non-residential buildings including the remaining Saddam-era presidential palaces that ISIS occupied immediately following their June 2014 capture of the city. Human Rights Watch identified from satellite imagery and coalition cockpit videos over 70 distinct impact sites in Tikrit with signatures consistent with the use of large, air-dropped munitions between early February and late March 2015.

Human Rights Watch reviewed satellite imagery recorded on March 21 and on April 5—the period in which government forces and militias captured the city—and found evidence of the start of a campaign of building demolition in a residential section of the al-Qadisiya neighborhood in northern Tikrit.

In satellite imagery taken on the morning of April 5, several days after the destruction reportedly began, Human Rights Watch identified 75 destroyed residential buildings, a destroyed local mosque (possibly the Furqan Mosque) as well as the presence of 16 vehicles deployed in two main groups on the western and southern edges of the al-Qadisiyya neighborhood.

All of the buildings had damage signatures consistent with the use of large quantities of high explosives, and, in one case, Human Rights Watch identified a smoke plume coming from the roof of a partially collapsed building, suggesting the building demolition had occurred shortly before the satellite image was taken on the morning of April 5.

Satellite imagery recorded on May 26, just under two months after ISIS withdrew from Tikrit, shows an additional 90 residential buildings were likely demolished with high explosives in the same area of al-Qadisiyya, occurring sometime after the morning of April 5.

Because of the spatial proximity, identical methods used, and the apparent deployment of multiple militia or government vehicles at the site on April 5, it is probable that in total these 165 buildings in al-Qadisiyya were destroyed during a single demolition event or campaign conducted in early April, starting after the capture of the city around April 1. The campaign destroyed about 75 buildings by the morning of April 5, and then continued in the following days to destroy the additional 90 buildings.

There are numerous reports of ISIS laying booby traps in and around Tikrit, along roads but also in houses and public buildings.[89] Clearing these booby traps slowed down the advancing government forces, reports said, and there are accounts of injuries and deaths of members of bomb squads defusing these devices.[90] These reports do not claim to account for the large-scale devastation that is visible after militias entered the city in April.[91] On April 2, for example, Gen. Shakir Jawdat, the head of the Federal Police, asserted that “Iraqi forces had also succeeded in removing over 500 explosive devices placed throughout [Tikrit] as well as seizing 13 factories used for making such devices.”[92]

Al-Bu ‘Ajil

Al-Bu ‘Ajil lies immediately east of Tikrit across the Tigris River. It was captured by ISIS at the same time as Tikrit on June 11, 2014 and retaken by pro-government forces around March 8. The district has a population of about 60,000. Satellite imagery of al-Bu ‘Ajil shows extensive destruction of civilian buildings. The images show that large swathes of residential buildings were destroyed through demolition or fire over the entire al-Bu ‘Ajil area from March 10 to April 5.

In a video dated March 9, the person filming from inside a moving car repeatedly shouts “Burn them! Burn them!” to men in uniform while saying, “This is the area of al-Bu ‘Ajil, which is now under the control of the League of the Righteous.” The video shows almost every building that the vehicle passed burning with large plumes of smoke rising to the sky.[93]

Human Rights Watch interviewed Aqil (pseudonym), a businessman who left al-Bu ‘Ajil when it was under ISIS’ control but remained in contact with the few Sunnis who had volunteered for the pro-government Popular Mobilization Committees. He said he heard from these sources that three days after the League of Righteous militia entered the al-Bu ‘Ajil they started burning down houses on a large scale. He said this was “in revenge for

ISIS crimes against the Shia,” adding, “first, they targeted the opulent houses, but later also destroyed houses of poor farmers.”[94]

Looting, Extrajudicial Killings in Tikrit

In Tikrit, militias also engaged in significant looting. Muhammad Jasim, the businessman who runs a large appliance shop, showed Human Rights Watch photographs of militias looting and torching his store. In one video, shot on March 31, while Ahmad al-Krayim, head of Salah al-Din’s Provincial Council toured Tikrit, a white truck is visible in front of Jasim’s store while men in fatigues load up appliances.[95] Pictures taken later that Jasim provided to Human Rights Watch show the shop’s three floors empty and burned.[96]

Witnesses said Shia militias also carried out apparent extrajudicial killings in Tikrit. Rami, the policeman, said that when he patrolled an area of the Qadisiyya neighborhood in early

April, he saw two dozen ISIS fighters emerge from buildings in small groups and surrender to the militias present, mostly Badr Brigades and League of the Righteous forces, recognizable from their emblems. The ISIS fighters said they were out of ammunition and food. The militias grouped them roughly five apiece and distributed the prisoners among themselves. Then, Rami said, he saw militia members execute some of the ISIS prisoners on the street before his eyes.[97]

On April 3, Reuters correspondents reporting from Tikrit witnessed Federal Police officers stabbing to death of a suspected ISIS fighter. The correspondents also saw Shia militias looting property and dragging a corpse of a suspected Islamic State fighter behind a vehicle.[98]

A local policeman found Khaz’al al-Thuwaini, a former high-ranking army officer who remained in Tikrit under ISIS, shot dead on the doorstep of his house, al-Thuwaini’s son, Ali, told Human Rights Watch.[99] Human Rights Watch independently spoke with al-Thuwaini’s nephew, Ghazwan, who said that al-Thuwaini had responded to a phone call on the morning of March 28.[100] Ali said that when he called later that day, a person who said he was with League of the Righteous answered, claiming his father was sleeping, but fine, and demanding a bribe in the form of credit for a mobile phone. Rami, the police officer, said he heard about al-Thuwaini’s killing while in Tikrit, and that the militia left his body in the street for four days, and prohibited anyone from coming near.[101]

Many militias participated in the battle for Tikrit and subsequently spread out over the city. Local policemen said they saw fighters from the Ali Akbar Brigades, the Khorasan Companies, the Hizbollah Battalions, the Soldiers of the Imam, and the Badr forces, in addition to the League of the Righteous.

III. Detentions and Enforced Disappearances

Four persons abducted, one witness and two persons who were in touch with six further persons abducted have implicated forces of the League of the Righteous and Hizbollah Battalions in the unlawful detention of persons in areas under their control in the rural Jallam al-Dur area, east of al-Dur town. ISIS has also been responsible for abducting civilians, including in mass arrests, and holding them for prolonged periods, according to residents from al-Dur, al-Alam, and Tikrit.

From March 6 to 8, forces of the Hizbollah Battalions and the League of the Righteous allegedly took over 200 people into custody in the Jallam area. Of those people, currently more than 160 men and boys remain missing and appear to have been forcibly disappeared.[102]

Enforced disappearances are defined as the detention of a person by state officials or their agents followed by a refusal to acknowledge the detention or to reveal the person’s fate or whereabouts. People held in secret are especially vulnerable to killings, torture and other abuses, and their families suffer from lack of information.

Three witnesses to abductions identified emblems of the League of the Righteous on the perpetrators’ uniforms, which they said they recognized from television broadcasts. A 14-year-old boy detained with a group of women and children from Jallam al-Dur for two days correctly identified a leader of the League of the Righteous from a photograph and said he was present at his abduction.[103] Others, including police officers, identified forces of the Hizbollah Battalion at the scene of abductions and, in the first few days, the presence of Badr Brigades.[104]

Munir, a resident of the Jallam area, said that on March 6, forces of the League of the Righteous entered the area without a fight a few days after ISIS forces had left.[105] There were 600 people from about 100 families still resident in the Jallam area, he said. Many came from al-Dur seeking refuge in safer rural areas ahead of the expected battle for the town. There were no police or other local security forces, he said.[106]

The detainees were treated differently depending on which militia was holding them and whether their group of detainees contained men and older boys.

Detentions by the League of the Righteous

Munir, the Jallam al-Dur resident, provided Human Rights Watch with a detailed account of abductions for two days starting 6 March by forces of the League of the Righteous in March. Another resident, Ghaith (a pseudonym), broadly corroborated this account.[107] Munir said that he welcomed the militias and cooked for them, but that the militia leader aggressively said, “We want revenge for the Camp Speicher massacre. You are all al-Bu ‘Ajil,” referring to the tribe north of al-Dur believed by some to have played a role together with ISIS in that atrocity.[108] Munir said 11 militiamen occupied his house on the evening of March 6. At night, after intelligence officers from the militia joined them, they interrogated the roughly half dozen men in the house, alleging they had joined ISIS. One militiaman hit Munir in the head with a rifle butt, causing his ear to bleed, and said, “Let me slaughter him,” but the militia commander intervened, Munir said.[109]

Munir said he received some protection because his Iraqi identity card lists Shu’la, a Shia section of Baghdad, as his birthplace. When the forces of the League of the Righteous were about to execute Munir’s cousin because they had found a photo of Saddam Hussein’s daughter Raghad on his phone, Munir said he called a Shia sheikh from Shu’la he has known since his childhood days, and the sheikh intervened and saved his cousin.[110]

That night of March 6, Munir said, militiamen of the League of the Righteous took him, Hajji Khairullah, Abdullah Mutlaq, neighbors, and four people from al-Dur about seven kilometers eastwards on the al-Bu Khaddu Road from Jallam to the house of Samir Mukhlif. There, seven people were interrogating three young men, sons and possibly a nephew of a man called Ali Hashim, who is from al-Dur. Munir said the interrogators wanted the three to confess that they had joined ISIS. Munir said many young men of the al-Bu Khaddu tribe had indeed joined ISIS when the group came to the area.[111]

Munir said the main interrogator was a 43-year-old medical doctor, who asked the questions, while the others strung up the three men and beat them. The three eventually said they were ISIS members and implicated Ali Hashim. Munir said he knew Ali Hashim and that he was actually a member of the Popular Mobilization Forces, which had fought in the battle against ISIS.[112]

Early on the morning of March 7, a cleric affiliated with the League of the Righteous, whom Munir said he had seen on television but could not name, arrived and had the seven men taken from Jallam al-Dur the previous night and around 50 others already at the house who emerged from two rooms of the house bound, blindfolded and loaded on Silverado trucks and driven off.[113]

From underneath his blindfold, Munir spotted buildings that indicated they were traveling to the town of Samarra to a house in Tayyub village, just north of Samarra.[114]

There, Munir said, militiamen beat them and 17 other detainees from Samarra already present, forcing them into squatting stress positions. A little later, another cleric apparently affiliated with the League of the Righteous ordered them to parade in rows of four, barefoot, outside a house where more than 20 media teams with cameras had assembled. The militia leader said, “These are the ones responsible for Camp Speicher,” and then led them away. When militiamen ordered them to face a wall, Munir thought they were about to be executed. However, at that moment the main interrogator from the night before, the doctor, arrived and said that their group of 50 were not ISIS.[115]

Munir said that while standing at the wall, the cell phone of another detainee, Abdullah Mutlaq, rang, which the militia had apparently not found. The doctor ordered Mutlaq to answer, but not say anything. However, Mutlaq quickly told the caller, “We are in Tayyub, in Mutashshar al-Samara’i’s house.” The doctor quickly ended the call and took Mutlaq away. Munir said he and the other detainees could hear Mutlaq’s screams all evening until midnight, when they brought him back to the others. Mutlaq was whimpering from pain, and then the militiamen took him away again.[116]

The following day, March 8, another militia cleric arrived and said they would hand the detainees over to Samarra authorities. That afternoon, when boarding trucks to Samarra, one of the original seven interrogators came up to Munir and said, “Tell Abdullah Mutlaq’s family that we finished him. We found a message on his phone that read ‘We have won against the Safavids in Baiji’.”[117] Some Sunnis, and ISIS in particular, use “Safavid,” a historical reference, pejoratively to describe Shia. Munir told Human Rights Watch that he never heard from Mutlaq again, but that he knows about the text message, which he said Mutlaq’s cousin, who had joined ISIS, had sent in 2014. The three other young men who were beaten were later released, Munir said.[118] Everyone else in the two groups, one of more than 50 men from the Samir Mukhlif’s house, and the other of 17 people already at the Tayyub house, was accounted for upon release to the authorities.[119]

Detentions by the Hizbollah Battalions

Hizbollah Battalions allegedly detained several groups of people from Jallam al-Dur, and later released them in different locations. At the time of writing, one and possibly two groups remain in presumed detention in the custody of the Hizbollah Battalion.

A 14-year old boy who was detained on March 6 said that militias kept him with a group of about 50 women and children after first apprehending and then separating men from the women and children. The militias comprised the Badr Brigades, the Ali Akbar Brigades, the League of the Righteous and the Hizbollah Battalions, the boy said, but he did not recall which militia was in charge of his group. The militias had entered the Jallam area right behind the regular army, which left shortly thereafter.[120]

The 14-year old boy recounted how the militiamen searched the women and children and kept them in the rooms of one house for two days. Then militiamen who said they were from Hizbollah took him away alone to a more remote house where other militiamen were present, he said. There they repeatedly asked him his name, a common Shia name but one also used by Sunnis. When he answered, gave his name a militiaman shouted at him: “No, your name is Umar!” referring to a common Sunni name which is rarely used by Shia the boy said.[121]

The militiamen eventually returned him to the group of women and children. The next day an army truck transported this group to Samarra city, some 40 kilometers to the south. The short journey took several hours, the boy said, because Hizbollah checkpoints made the truck wait. On the advice of an army soldier, the boy hid deep under blankets and other people, so that the militiamen would not take him away, as they had only agreed to let the women and younger children out. In Samarra, a local politician, Kamil Ashraf, received them at his house and then sent them on to relatives’ houses in the city, the boy said.[122]

Fatima (a pseudonym), who is from al-Dur, told Human Rights Watch that she and her three children came to Jallam al-Dur three days before the militia forces moved into the Jallam area. She said Badr forces initially detained all families and separated them by gender, with boys under the age of about 13 remaining with the women and girls. She was in a group with 25 women, girls and young boys segregated from 17 men and older boys. They treated them well, she said, until the next day Hizbollah forces took over, taking their cell phones and identity documents but not the women’s jewelry.[123] She knew the identity of the militia by the flags on their vehicles.

Hizbollah Battalions on March 7 proceeded to blindfold and cuff the men, Fatima said. Then they drove the men in a Toyota pickup and the women in a Kia truck to a clinic in the village of Na’ima, on the Tikrit-Tuz Khurmato Road, where other families were already present. Around noon the next day, the militiamen took the men away, including Fatima’s brother-in-law and her husband’s cousins who remain unaccounted for.[124] That night, the militiamen took about 70 women and children and left them with local Bedouins in the desert, Fatima said. There, units of the Khorasan Companies, another Shia militia, were in charge and looked after the women and children. When they tried to return them to al-Dur, the Hizbollah checkpoints blocked them. They eventually made it to Samarra, she said.[125]

Fatima said that one boy told her Hizbollah had detained him and other males in the al-Hamra school in Tayyub, just north of the city of Samarra, and others in a “yellow building” in Balad, 40 kilometers south of Samarra. Apart from nine released boys, the men and other boys remain missing.

A police officer who had been in al-Dur and Jallam al-Dur days after the militias entered al-Dur told Human Rights Watch that he had been in touch with a handful of boys released in late April. The policeman said that one boy recounted being held in an unfinished “yellow building” perhaps a couple of kilometers from the center of the town of Balad. The policeman said that, according to the released boy, three persons had died in Hizbollah custody.[126] Human Rights Watch could not confirm those deaths.

On March 21, Dhiya al-Duri, Member of Parliament for al-Dur, publicly raised the question of the whereabouts of the reported 160 missing men and boys.[127] By mid-June, he had not received any response about the issue, he told Human Rights Watch. He said there had been no acknowledgement that the missing men and boys had been taken, by whom, or where they were being held. Al-Duri said he had approached the head of the Popular Mobilization Forces in Samarra, the Salah al-Din provincial council and governorate, the parliament’s security and defense committee and Prime Minister Abadi’s office over the past months.[128]

IV. International Military Assistance to Iraq

The UN Security Council imposed an arms embargo on Iraq in August 1990, modifying it, most recently in Resolution 1546 of 2004, to allow for arms deliveries to the Iraqi government, but maintaining the embargo for other end-users in Iraq.[129]

The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute lists over 20 countries, including the United States, Iran, Russia, Ukraine, Poland and Hungary, that have supplied Iraq with weapons and military equipment and training.[130] The US has been the largest provider of military equipment to Iraq.[131]

While US legislation requires significant end-use monitoring, it is unclear to what extent the US has implemented these requirements. Human Rights Watch does not have information regarding whether other supplier countries implement such requirements.[132] It is clear that irregular Iraqi militias implicated in serious human rights abuses, including abuses documented in this report, have used US and Iranian weapons in their operations.

In Resolution 1747 of 2007, the Security Council imposed an embargo on Iranian transfers of “any arms or related materiel,” which at this writing remains in place.[133] Nevertheless, Iran has provided military assistance to Iraq in the form of materiel, as well as training and advice; in February 2015 the Guardian newspaper, citing an Iranian military official, reported that Iran had provided Iraq with $16 billion worth of arms transfers since June 2014.[134] In February 2014, Reuters reported that it had seen contracts for Iranian weapons sales to Iraq worth $195 million.[135] According to reports on Bellingcat.com and Jane’s Defence Weekly, Iran appears to have provided the Iraqi army, Shia militias, and Kurdish Peshmerga forces Russian-made but Iranian-modified T72 tanks, Iranian Safir jeeps and Sayyad sniper rifles, among other equipment.[136]

According to the US Defense Department’s Security Cooperation Agency, US military supplies to Iraq include ammunition, missiles, armored vehicles, F-16 fighter jets, and M1A1 Abrams tank parts.[137] The US has trained 11,000 members of new Iraqi army units and tribal fighter units.[138] According to a March 2015 article in Newsweek, US officials said the government suspended military transfers to certain Iraqi military units, but Washington has not made available any further information, despite legal requirements that the government make information about suspended units public, to “the maximum extent practical.”[139]

The US Arms Export Control Act requires the government to monitor that its military transfers remain with Iraqi government forces as the intended recipients.[140] However, the US government provides only cursory public reporting on the results of its end-use monitoring (the State Department Blue Lantern program), and it is unclear whether the US has investigated the use of US weapons by irregular Iraqi militias implicated in abuses, including abuses described in this report. The State Department’s 2014 annual report on the program states that its investigators looked into 48 cases of possible end-use violations of US military equipment in the Near East region, and recommended ending or modifying a military transfer in 13 cases.[141] The government did not report further details about the countries, recipients or types of military transfers involved, including, for example, whether the investigations comprised two prominent Iran-backed pro-government Shia militias, the Hizbollah Brigades and Badr Brigades, following the publication of videos and pictures that purport to show the militias in possession of US equipment, including M1 Abrams tanks.[142]

Similarly, the Foreign Assistance Act requires the US to suspend assistance to units involved in gross human rights violations.[143] Additionally, the US Senate’s 2016 Defense Appropriations Act, if it were to become law, would require that recipients of military transfers under a $1.6 billion “Iraq Train and Equip Fund” are “appropriately vetted, including, at a minimum, assessing such elements for associations with terrorist groups or groups associated with the Government of Iran; and receiving commitments from such elements to promote respect for human rights and the rule of law.”[144]

In light of the abuses carried out by Iraqi pro-government militias documented in this report and elsewhere, governments providing military assistance to Iraq should urge and support Iraq to undertake concrete and verifiable reforms to hold perpetrators of serious abuses accountable, integrate pro-government militias into a centralized command structure subject to civilian oversight and control, and ensure that those forces fully adhere to international humanitarian law. These governments should require Iraq to report publicly within one year on progress towards implementing these reforms, after which they should suspend military assistance and sales commensurate with Iraqi compliance gaps on those reforms.

V. International Legal Standards