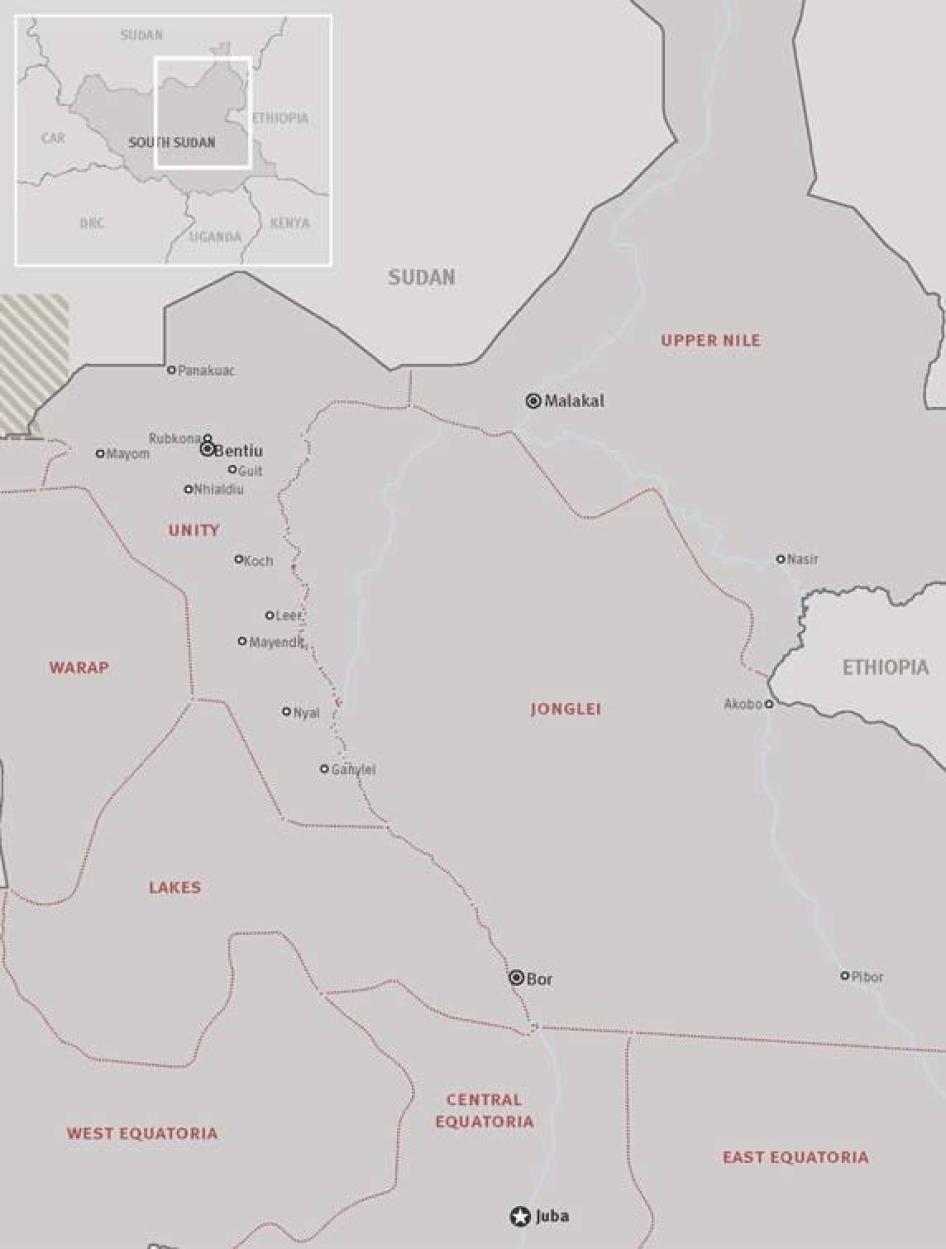

Map of South Sudan

Glossary

Age set: A system of social stratification. Individuals who are around the same age often share an important kinship. Which age set an individual belongs to is often more important than their official age. Boys may go through an initiation ceremony, making them men in the eyes of their communities before they are 18, together with other members of their age set.

Bodyguards: Child soldiers are often used as bodyguards by their senior officers. In this role children often cook, clean and perform other similar duties. Although those who are bodyguards are sometimes kept from frontlines, these children are expected to protect their “big men” and have sometimes been involved in fighting. In other cases, children work as servants/bodyguards during times of relative calm but fight together with other soldiers.

Boma: A small administrative area.

Cobra: The South Sudan Democratic Army-Cobra Faction, David Yau Yau’s former militia.

Hybrid Court for South Sudan: A hybrid court has both national (in this case South Sudanese) and international staff, including judges and lawyers. The August peace deal proposes a hybrid court for South Sudan to be established by the African Union Commission.

IGAD: The Intergovernmental Authority on Development, a regional body that has headed the South Sudan peace talks and monitored breaks in the cessation of hostilities agreement.

Local Defense Forces: Loosely formed armed civilian groups that fight to defend their community area. Both the government and the opposition forces have supported and fought together with such groups during the conflict.

Protection officers/workers: Humanitarian workers who implement programming to help local or displaced populations to avoid attacks or persecution.

SPLA: South Sudan’s army, the Sudan People’s Liberation Army.

SPLA-IO: The opposition, headed by Riek Machar, the Sudan People’s Liberation Army-in Opposition.

UN bases: Tens of thousands of South Sudanese have fled to bases protected by UN peacekeepers for sanctuary. The UN bases have become an important feature of the recent conflict.

UNICEF: The United Nations Children’s Fund.

UNMISS: The UN Mission in South Sudan

Summary

There is nothing to gain from fighting, you waste your time and you die. – BL, 10 years old when he joined an armed group, he says to protect his community, family and himself from abuses by government forces, April 2014.

We can die too, like everyone else; it’s safer as a soldier. It is like a competition where do you run to, to be safe? You either die, or kill your enemy. Everyone is treated the same way, whether young or old. – RH, 16 years old when he joined the opposition forces to protect himself from attack, January 2015.

Thousands of children have fought in South Sudan’s recent conflict and tens of thousands remain at risk of recruitment. Since South Sudan’s recent war, which began in December 2013, neither government nor opposition leaders have ended widespread recruitment and use of child soldiers despite promising to do so. A peace agreement signed in August 2015 between President Salva Kiir’s government and the opposition headed by former Vice President Riek Machar may end fighting and eventually provide for the release of child soldiers, but unless measures are taken to ensure accountability any further conflict will likely be accompanied by child recruitment.

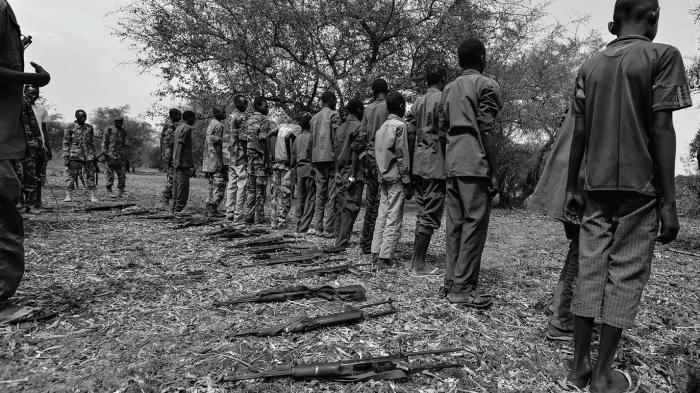

This report is based on interviews in 2014 and 2015 with 101 children associated or formerly associated with armed forces and groups from Dinka, Nuer and Shilluk tribes, mostly from the three states of Unity, Jonglei and Upper Nile. Some of the children were as young as 13 years of age but most of them were between 15 and 17 years of age. It describes their experiences of being recruited, of battles and of living as part of a fighting force. Human Rights Watch heard statements of anger, emotional pain, satisfaction and grim fatalism, but because child soldiering has marked much of South Sudan’s history of violence, few children expressed surprise that they fought.

Both the government Sudan People’s Liberation Army (the SPLA) and their allies, and the rebel Sudan People’s Liberation Army-in Opposition (the “opposition”) and their allies have fought with children. This report includes information about recruitment and use of child soldiers by, among others, the former rebel leader David Yau Yau, who has not fought in the recent conflict (but may do so if fighting continues), Johnson Olony who has fought on both the government and opposition sides in the recent conflict, and Matthew Puljang, who has helped the government control much of Unity state. In Unity state, the opposition commanders Peter Gadet and James Koang and his deputy Makal Kuol have used child soldiers as bodyguards or led them in battles.

For decades, South Sudanese civilians have suffered war crimes and human rights abuses while living through ethnically factionalized and brutal civil wars, insurgencies, and inter-tribal conflicts. Recruitment and use of children as fighters and soldiers have been hallmarks of these conflicts. Boys, perceived by themselves and others as having a duty to protect their community and cattle in the face of frequent danger–including from government forces–have constantly participated in violence. Before South Sudan’s war began in December 2013 important gains had been made in improving access to education and ending the norm of child soldiers, including through laws banning the practice. But the scale of recruitment and use of children in the recent conflict, including brutal forced recruitment, has greatly eroded prior progress in improving child rights.

The practice of child soldiering in South Sudan is widespread and the country’s conflict is complex, made up of various forces under leaders or military commanders with idiosyncratic approaches to children under their control. Children reported widely different experiences of being recruited and deployed.

Often children were forcibly recruited, were physically forced onto trucks bound for battles or training camps, or abducted at gun point and taken from their home areas by forces or groups, and then sometimes thrown into battle just a day or two later. Even those who joined willingly, albeit often because as males of (perceived) fighting age they were likely to be killed without the protection of other fighters around them, or because of societal pressure, were unable to leave if they wanted to and instead sent into battles.

Some of those who fought with government forces sometimes received salaries but usually very irregularly. Many children who fought with government forces as well as those who fought with the opposition received training and uniforms, underscoring their formal role as soldiers, while others joined fighting for short periods of time less formally. Most of the 15-16,000 children the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) estimate have fought in this conflict did so as part of opposition-aligned community forces. On both sides, boys, especially from around 14 or 15 years old or older, who form the majority of child soldiers in South Sudan, but also some younger ones, were treated more or less the same as adult soldiers.

Others, especially boys younger than 14 years old, did not fight, but worked as cooks or bodyguards for commanders. Many of the boys who spoke to Human Rights Watch said they were made, like adult soldiers, to walk for days and fight without adequate food. All the interviewed children said they were forced to sleep in the open and, if they were injured, received little or no medical care. Many saw their friends or other children die; get injured; become traumatized. Some were beaten and/or detained by the forces that recruited them as a way to prevent them from escaping, or as punishment.

Despite all these hardships, some said they felt grateful to their commanders for taking them in. In the midst of a grossly abusive conflict, they believed that being part of an armed group afforded them some protection, and also the opportunity to fight to protect their community or to fulfil their desire for revenge for attacks or abuses.

None of the boys Human Rights Watch interviewed attended school while they were serving in armed groups or forces, and all said that they would prefer to be in school rather than fight and that they regretted the loss of time away from schooling. During the conflict, most schools in conflict areas in Jonglei, Upper Nile and Unity states were shut for at least several months; at least 45 schools have been used for military purposes by government forces since the conflict began. Other schools were adversely affected by the government decision to stop paying teachers’ salaries in opposition-held areas. Increasing educational opportunities including in UN bases where tens of thousands former or resting or recuperating child soldiers and other children are seeking shelter could help prevent child recruitment. An immediate step is also ending the practice of soldiers and fighters using schools for military purposes.

The children Human Rights Watch spoke to, not only from the Dinka and Nuer but also the Murle and Shilluk tribes, often felt that they needed to protect themselves and their communities from fighters from other ethnic groups. Tribal hatred has dominated much of the conflict and will almost certainly continue to be leveraged by leaders to bring civilian devastation as long as conflict continues. The risk of further ethnic violence, and even genocide, in South Sudan remains high.

A failure to end child soldiering now may send the message to another generation that the only way to feel safe is through ethnic-based, organized violence and that is it normal for children to participate, and die, in it.

Before the current conflict began, in December 2013, important and sometimes successful efforts were underway to end child soldiering in South Sudan. Thousands of children were released from the SPLA and other armed groups after Sudan’s 1983-2005 north-south war ended. The post-2005 Southern government passed legislation criminalizing recruitment and use of anyone under the age of 18 years in armed conflict/as soldiers and signed an agreement with the UN to work to end child soldiering. The SPLA set up a Child Protection Unit to monitor barracks, help release child soldiers and, in theory but never in practice, to bring abusive commanders to book. Formal release of child soldiers has followed peace deals ending insurgencies in more recent years. Efforts to reduce military use of schools by over the years clearing them of soldiers in many different parts of the country were successful.

The outbreak of new conflict in December 2013 has reversed much of the progress made since the end of the civil war in 2005. The SPLA’s Military Justice component and Child Protection Unit stand in disarray, under-supported by the army and presently without technical or logistics support from the UN or donors. The opposition did not appoint an appropriate official to work with the UN to monitor and end child recruitment after signing an action plan with the UN. The SPLA in 2015 cleared some schools of soldiers, but as far as Human Rights Watch has been able to ascertain, neither side has punished commanders for recruitment and use of children.

While government and UN efforts since 2005 have raised awareness about the use of children as soldiers, a violation of international standards, and helped begin to shift South Sudan away from a norm of child soldiering, the recent conflict shows that when fighting begins, using large numbers of children to boost forces remains a low cost and attractive tactic for commanders.

Over the past 15 years, government officials and international partners have, unwittingly, further bolstered the use of child soldiers in South Sudan. Their support for child soldier release and reintegration programs, which are sometimes slow, without sufficient emphasis on accountability, has allowed the practice to continue unchecked and helped strengthen the perception that child soldiering is a normal part of conflict and that donors will step in to finance release when commanders are willing to allow it.

Serious efforts should now be made, by both national and international actors, to ensure that commanders who have used and recruited child soldiers are held accountable.

South Sudanese authorities should investigate and prosecute commanders who have violated South Sudan’s law by recruiting and using children under 18 years of age. In the meantime, the SPLA should discipline commanders in violation as should the rebel Sudan People’s Liberation Army-in Opposition.

The August 2015 peace agreement between the government and the opposition, brokered by the regional body the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) paves the way for a transitional government with Kiir as president and Machar as vice president and for national elections in around three years. The deal provides for a ‘Hybrid Court for South Sudan’, to be established by the African Union Commission, consisting of judges and lawyers from other African countries together with South Sudanese officials, and to have primacy over South Sudan’s national courts. This hybrid court is necessary because a purely domestic effort to provide accountability for international crimes committed in this conflict will not assure fair, credible trials given major challenges within the national courts and a lack of political will on the part of South Sudan’s leaders. The hybrid court should have jurisdiction over the most serious crimes committed, including the recruitment and use of children as soldiers, and complete authority and independence to determine which accused it will prosecute.

If a credible, fair and independent hybrid court is not established, the option of the International Criminal Court (ICC) remains and should be pursued. As South Sudan is not a party to the court, the UN Security Council would need to refer the situation to the ICC in the absence of a request from the government of South Sudan.

South Sudan’s partners and neighbors who have supported the peace talks should ensure that the provisions for accountability and truth-telling promised in the peace agreement are implemented by both sides and are financially supported. The UN should provide technical support for the establishment of the hybrid court and the Security Council should continue to insist on accountability for serious crimes.

The UN Security Council should also impose travel bans and asset freezes on commanders who have used or recruited children in South Sudan or who continue to do so. A UN arms embargo should be imposed on South Sudan to stem the flow of weapons which has contributed to widespread abuses against civilians. Despite the peace agreement, violence has continued as have reports of serious abuses against civilians. In some instances children have been drawn to armed groups to get guns and reducing the availability of small arms could also lead to fewer children becoming soldiers.

Recommendations

To the Sudan People’s Liberation Army, the Sudan People’s Liberation Army in Opposition and Other Armed Parties to the 2013-2015 Conflict

- End all recruitment and use of children under 18 years of age by regular forces or by associated militias. End armament or other assistance to armed groups, including local defense groups that conscript and/or use children under the age of 18 years.

- Insist that local defense forces and militia commanders cease the recruitment and use of child soldiers, and cease cooperation and military operations with those who persist.

- Investigate, in coordination with civilian investigators, commanders who recruit and use children and hand over cases to civilian courts to prosecute.

- Cooperate with UNICEF and other child protection agencies to disarm and release children within forces and aligned militias, including but not limited to proposed cantonment sites, and transfer them to appropriate civilian rehabilitation and reintegration programs that include educational and vocational training as well as necessary counseling, in accordance with the Principles and Guidelines on Children Associated with Armed Forces or Armed Groups (“Paris Principles”) of 2007. Provide information about, and allow monitoring of, cantonment sites, military bases and other such sites for child soldiers by national civilian and international observers, and, in the case of the SPLA, the army’s Child Protection Unit and Military Justice officers.

- Immediately cease all military use of schools and school compounds, prioritizing schools where students and teachers are present, or in areas where schools could be reopened if soldiers vacate the premises.

- Immediately issue public orders directing all commanders and forces to cease pillaging or conducting other attacks on schools, stating that those responsible for such attacks will be held to account.

- Pending investigations, suspend from their positions any commanders who are credibly alleged to have recruited and used child soldiers and/or who have allowed soldiers to remain in schools.

To the Transitional Government of South Sudan

- End all recruitment and use of children under 18 years of age by regular forces or by associated militias. End armament or other assistance to armed groups, including local defense groups that conscript and/or use children under the age of 18 years.

- Insist that local defense forces and militia commanders cease the recruitment and use of child soldiers, and cease cooperation and military operations with those who persist.

- Investigate, in coordination with civilian investigators, commanders who recruit and use children and hand over cases to civilian courts to prosecute.

- Cooperate with UNICEF and other child protection agencies to disarm and release children within forces and aligned militias, including but not limited to proposed cantonment sites, and transfer them to appropriate civilian rehabilitation and reintegration programs that include educational and vocational training as well as necessary counseling, in accordance with the Principles and Guidelines on Children Associated with Armed Forces or Armed Groups (“Paris Principles”) of 2007. Provide information about, and allow monitoring of, cantonment sites, military bases and other such sites for child soldiers by national civilian and international observers, and, in the case of the SPLA, the army’s Child Protection Unit and Military Justice officers.

- Immediately cease all military use of schools and school compounds, prioritizing schools where students and teachers are present, or in areas where schools could be reopened if soldiers vacate the premises.

- Immediately issue public orders directing all commanders and forces to cease pillaging or conducting other attacks on schools, stating that those responsible for such attacks will be held to account.

- Pending investigations, suspend from their positions any commanders who are credibly alleged to have recruited and used child soldiers and/or who have allowed soldiers to remain in schools.

- In cooperation with the former warring parties, hold accountable all individuals who have recruited or used children under the age of 18 in the SPLA, the opposition, or in associated militias during the conflict, in accordance with South Sudanese law. Individuals allegedly most responsible for recruitment or the use of large numbers of children should be prioritized for investigations and prosecutions into these crimes. Prosecutors in the envisaged hybrid court should also investigate and prosecute the crime of recruiting and using children under 18 years of age as soldiers; the transitional government should support this.

- Suspend and remove from relevant army positions any commanders who are known to have recruited or used children, or are credibly alleged to have done so.

- Do not integrate into the SPLA or other security forces any commanders from militias who have recruited and used children, or who are credibly alleged to have done so.

- Investigate David Yau Yau and senior commanders in his former militia group for the recruitment and use of child soldiers in 2012-2013, prior to the outbreak of the current conflict.

- Support the establishment of a hybrid court, as agreed in the August 2015 peace agreement, or request the International Criminal Court to investigate potential war crimes and crimes against humanity committed during the conflict.

- Make public information regarding measures taken to ensure the accountability of perpetrators.

- Provide financial and political support to the Child Protection Unit and the army’s Military Justice section and task them with investigating the recruitment and use of child soldiers during the conflict, identifying and investigating perpetrators and referring cases to civilian courts. The Minister of Defense should report to parliament on progress in this regard.

- Complete ratification of the Optional Protocol on the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the involvement of children in armed conflict by depositing this instrument at the UN.

- Immediately resume paying teacher salaries in areas that have been under the control of opposition forces during the conflict.

- Ensure that all children are registered immediately after birth, and develop a national birth registration process including through the enactment of a civil registration law.

To the Sudan People’s Liberation Army

- Hand over those who are credibly alleged to be responsible for recruitment and use of child soldiers to civilian authorities for further investigations and prosecution.

- Establish rigorous and systematic screening procedures and standards to ensure that no children under the age of 18 are recruited going forward, and that all recruits are screened according to the same high level of standards. Use the UN’s age assessment measure and do not recruit individuals where there is reasonable doubt that they are not of the lawful recruitment age.

- Allow independent, including international, monitors to take part in recruitment processes, to monitor age during salary disbursements, and to visit SPLA facilities to identify child recruits.

- Discipline soldiers who used schools for military purposes in violation of the Punitive Order issued by the SPLA Chief of Staff on August 14, 2013.

To the United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS)

- Monitor abuses against children and include findings in a section on substantive violations against children in public periodic reports of the UN secretary-general.

- Through the Human Rights Division or the Child Protection Unit, publish information gathered during the conflict and subsequently about commanders who have recruited or used child soldiers, or at a minimum, provide this information to the UN Panel of Experts formed under UN Security Council resolution 2206 (2015).

- Increase investigations, through a task force dedicated to this end, into child soldier recruitment and use during the conflict including by interviewing former child soldiers, collecting information on command and control structures of government and opposition forces as well as key militias that have used child soldiers. Archive information collected so that it can be used for vetting of forces and for accountability mechanisms in the future.

- Monitor any release processes and follow up to ensure re-recruitment does not take place. Send child protection officers when monitoring barracks, training camps, militia bases, and cantonment sites to ensure they contain no child soldiers–and if child soldiers are present, assist with their release and family tracing and reunification.

- Provide transport and other assistance to the SPLA Military Justice and Child Protection Units to assist them in registering child soldiers, releasing child soldiers, and providing accountability for recruitment and use.

- Ensure a human rights screening process so UNMISS does not provide any logistical, military, or other support to commanders or army units or other forces responsible for gross human rights violations or to units led by commanders implicated in serious abuses, as per the UN’s Human Rights Due Diligence Policy.

- Increase monitoring of pillage or other attacks on schools and military use of schools, especially in areas controlled by opposition fighters.

To the United Nations Security Council

- Impose a comprehensive arms embargo on South Sudan and expand the existing mandate of the UN Panel of Experts to monitor and report on implementation of the embargo.

- Impose targeted sanctions, including travel bans and asset freezes, on individuals against whom there is sufficient evidence of responsibility for recruitment and use of child soldiers, including Matthew Puljang and Johnson Olony; investigate other commanders mentioned in this report with a view to determining appropriate action against them for their role in recruitment and use of child soldiers.

- Request that a representative of the UN secretary-general work in conjunction with the African Union to help establish a hybrid court, with a majority of non-South Sudanese judges and lawyers, located outside South Sudan at least initially, which can ensure fair, credible investigations and prosecutions for serious crimes committed in South Sudan including recruitment and use of children.

- Intensify pressure on the Transitional Government of South Sudan, the Sudan People’s Liberation Army and the opposition forces to release children from forces and provide socio-economic reintegration assistance to the affected children and their families, family tracing and reunification and educational services to children in accordance with the Principles and Guidelines on Children Associated with Armed Forces or Armed Groups (“Paris Principles”) of 2007.

- Intensify pressure on the Transitional Government of South Sudan to end the recruitment and use of children, including by establishing effective screening procedures to ensure that children are not recruited, accountability measures for commanders who have recruited and used children, and to end military use of schools.

To the UN Panel of Experts on South Sudan

- Investigate recruitment and use of child soldiers, especially in areas where children have been repeatedly recruited in large numbers, and propose that the UN Security Council places sanctions on commanders responsible.

To the United Nations Human Rights Council

- Appoint a Special Rapporteur on South Sudan with a mandate to monitor and publicly report on violations, including recruitment and use of child soldiers, as well as on military use of schools, and make recommendations for achieving effective accountability.

To the African Union Peace and Security Council

- Establish a hybrid court, with the assistance of the UN, with primacy over South Sudanese national courts, to investigate and prosecute those most responsible for international crimes, including the recruitment and use of children, committed in the conflict. Ensure witness protection services are established.

- Fully support the implementation of UN Security Council individual sanctions and arms embargo, if established.

To the Special Representative to the Secretary-General on Children and Armed Conflict

- Provide pertinent information to the Security Council’s sanctions committee on South Sudan regarding individuals who should be subject to targeted measures for recruitment and use of child soldiers.

- Continue to advocate with the SPLA for full implementation of its action plan to end the recruitment and use of child soldiers and the May 2015 recommendations of the Security Council Working Group on Children and Armed Conflict.

- Encourage the SPLA in Opposition to implement a UN action plan to end all recruitment and use of child soldiers.

To the United States, European Union Member States and Other Key Donors

- Offer the necessary support to appropriate child protection activities, including support to nongovernmental organizations working to release children from forces and to prevent further recruitment, and to any large scale release, rehabilitation, and reintegration programs that include vocational training programs, education programs, and medical and psycho-social counseling activities for former child soldiers, including in displaced people or refugee camps.

- Ensure that resources are available for mechanisms to identify children formerly associated with forces or armed groups upon arrival in refugee receiving countries and in internally displaced people camps.

- Provide support for clinical mental health programs for children who require more intensive support than those offered in general community based psycho-social programs.

- Support large scale assistance to the education sector, as well as funding for programs that promote social norms that disincentives child soldiering.

- Provide the Transitional Government of South Sudan, the Sudan People’s Liberation Army and opposition forces with the necessary support and capacity to systematically and effectively vet its recruits by age in order to prevent the recruitment and use of children within its forces. Provide support to the Military Justice and Child Protection Unit of the army to investigate child recruitment and use and provide accountability.

- Refuse to provide any military training or other security sector reform support to commanders or units in the army, or forces from other security forces, where there is credible information that they committed serious human rights abuses in the conflict. Support vetting programs that identify and exclude individuals who have committed, or where there is credible information that they committed, serious human rights abuses, from the army.

- Support, including financially, the establishment of a fair, effective hybrid court to investigate and prosecute serious crimes committed.

Methodology

Every child who has fought or been associated with an armed group in South Sudan has a unique story. Human Rights Watch made efforts to capture a range of experiences but this report does not describe the full spectrum of child soldiering in South Sudan. Children interviewed for this report include those who fought with government troops, opposition forces, and those who joined militias allied to both forces and loosely structured local defense groups.

Based on interviews with 101 child soldiers, former child soldiers or children associated with armed forces or young men who were children when they fought, this report documents experiences of recruitment and deployment and identifies commanders who have recruited and used child soldiers. These children represent only a tiny fraction of the thousands of children who have fought in the recent conflict alone. Of these children, 41 were associated with government forces or their allies and 33 with opposition forces or their allies. Twenty-seven children who had fought in conflicts that predated the recent war were also interviewed. Four of these were 18 or 19 years old at the time of interview, the rest were under 18 years of age.

The interviews for this report took place on multiple research trips to South Sudan between August 2014 and July 2015: three trips to Bentiu town; one to Ganylel and surrounding areas, Unity state; one to Malakal town, Upper Nile state; one to Bor and Panyagor, Jonglei state; and one to Pibor, also in Jonglei state. The Human Rights Watch researcher responsible for this report also made multiple visits to the Protection of Civilians site in the UNMISS base in Juba, Central Equatoria state, to interview former child soldiers living there.

All those interviewed reported seeing many other children fighting or associated with armed forces. Human Rights Watch also collected information about 30 other children from parents or caretakers who said their children had been abducted or recruited into armed forces and were away during the time of the interview.

Human Rights Watch has heard some reports of girls being associated with armed forces, but the vast majority of children associated with armed forces in South Sudan are boys, and all those interviewed by Human Rights Watch were male.

Identifying and interviewing child soldiers and escaped former child soldiers was challenging. Accessing child soldiers in active conflict settings was problematic, because of restricted access to these dangerous areas but also because of possible reprisals against children still part of armed forces.

Language, age and cultural differences between the interviewees and the researcher also almost certainly limited this research.

The names of child soldiers have been withheld to protect the confidentiality of those interviewed. Interviews took place in Murle, Nuer, Dinka and Arabic, with assistance from translators. Most of the interviews lasted 20 to 45 minutes and all took place in person. All interviewees gave consent. No incentives were provided.

All interviews took place in places where the child was safe during the interview, mostly in UN bases protected by UN peacekeepers or interim care centers for former child soldiers. Except in a few cases where children were interviewed together with relatives or trusted friends, interviews were conducted in private. Each interviewee was promised confidentiality. No one interviewed for this report received any payment.

Children who are forced to fight are often from poorer, more rural areas where many if not most children are born without having their births registered. It was often impossible to confirm the precise age of the child and sometimes the age provided in this report represents the best guess of the interviewee.

Human Rights Watch also interviewed 15 government officials and officials from the SPLA as well as opposition authorities with expertise or insights into child soldiering, staff of UN agencies, especially UNICEF and officials from UNMISS in Juba, Malakal and Bentiu. Staff from independent international aid groups, and child protection nongovernmental organizations were consulted in these locations and also in more rural research sites.

I. Background

South Sudan’s Conflict

On the night of December 15, 2013, a gun battle in South Sudan’s capital Juba between presidential guards loyal to President Salva Kiir on one side, and on the other, soldiers loyal to the former vice president, Riek Machar, triggered a national conflict that has since killed thousands of civilians, forced some 2.2 million people from their homes, and plunged much of the country into a humanitarian crisis. Hundreds of children have been killed, thousands have fought in the conflict and hundreds of thousands have been displaced.[1] The conflict has devastated the education sector, leading to the closure of some 70 percent of the schools in the areas where most of the fighting has taken place.[2] Some 400,000 children have been forced out of schooling.[3]

The recruitment and use of child soldiers has taken place within the context of a war in which both government Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) troops and Sudan People’s Liberation Army-in Opposition (the “opposition”) forces and their allies committed acts of extraordinary cruelty against civilians. From the first hours of the conflict, civilians were targeted and killed because of their ethnicity. In Juba, in December 2013, Dinka forces aligned to Kiir shot at, killed, rounded up, and massacred hundreds of male Nuer (the same tribe as Machar) and detained, tortured and beat others.

In the following weeks, forces made up of Nuer soldiers who had defected and allied ‘white army’ forces composed of armed Nuer, captured the town of Bor, Jonglei state.[4] They ransacked the town and surroundings, killing hundreds of mostly Dinka civilians leaving their corpses strewn around the area.

Attacks by government and opposition forces between mid-December 2013 and mid-April 2014 across the conflict areas of Jonglei, Unity, and Upper Nile states left thousands more civilians dead and towns pillaged and destroyed.[5]

This period was the most bloody and destructive since South Sudan gained independence in 2011 from Sudan and may have been the most gruesome four months in recent years of intermittent conflict in the region. Brutal abuses of civilians have continued.[6] But the patterns of abuse documented by Human Rights Watch and others in this conflict–including killings of civilians because of their tribe or presumed allegiances, burning and destruction of civilian property and massive pillage of civilian property–are not new. The absence of accountability for past war crimes and human rights violations has spurred new attacks and killings in the current conflict.

Violence, crime, abuse and revenge, especially for male children, were part of growing up even before the current conflict began. Life for many across Dinka and Nuer areas and other cattle-keeping communities has since 2011 been marred by escalating inter-communal conflict in the form of violent cattle raids and revenge attacks on villages. Numerous armed rebellions by ethnic-based militias have also taken place and boys have fought in these too. Rebel and government forces in their counter-insurgency efforts have committed war crimes and human rights violations.[7]

Decades of Child Soldiering in South Sudan

During the 1983-2005 north-south war in Sudan, thousands of child soldiers were used by southern rebel groups including the SPLA that became South Sudan’s official military after the 2005 peace deal, and also made its top commanders South Sudan’s political elite.[8]

The first large scale effort to end child soldiering in South Sudan was initiated by UNICEF’s then- Executive Director Carol Bellamy who in 2002 persuaded Salva Kiir, then chief-of-staff of the rebel SPLA, to sign a memorandum of understanding to end the use of child soldiers. UNICEF later airlifted 3,551 children from Northern Bahr el Ghazal state to transit centers in Lakes state.[9]

As peace negotiations continued in Kenya in the lead-up to the 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA), further releases of thousands of child soldiers took place, accompanied by family tracing and reunification. In 2005, thousands of children were released, many from militias that had been absorbed into the SPLA.[10] By 2012 some 4,000 children had been released.[11]

But even before the current war ignited in December 2013, child soldiers continued to be used by both government forces and insurgents in the context of several smaller-scale conflicts.

During their 2011-2013 insurgency, a group called the South Sudan Liberation Army/Movement (SSLA/M), initially headed by Bapiny Monytuel, used children in their rebellion against the South Sudanese government.[12] Some 200 children from this force were due to be released after Monytuel agreed to an amnesty deal in 2013.[13] In addition, many hundreds of child soldiers fought in the 2012–2013 rebellion headed by David Yau Yau in Pibor area of Jonglei state. With the assistance of UNICEF and the government, Yau Yau in 2015 released 1,755 children from his forces.

Government commanders also used child soldiers when conducive to their military goals before the current conflict began. For example, Human Rights Watch spoke with three young men in Bentiu, the capital of Unity state, who had all fought as 14 or 15-year-olds in the SPLA’s Division 4 when South Sudan attacked Sudan’s Heglig oil producing area in 2012 under the command of the then-division commander, Gatduel Gatluak.

Efforts to End the Recruitment and Use of Child Soldiers

Efforts by the SPLA to end recruitment and use of children made significant headway until they were undercut by the recent conflict. In 2009, with the support of UNICEF and Save the Children, the SPLA launched its Child Protection Unit, established to help prevent recruitment of children into the army and also to serve as a bridge between the military and international actors. Around 1,000 officers, of relatively low rank, were trained in child protection and were deployed across the army.[14] The unit helped identify, disarm, and release 54 children from the SPLA since its formation, and had plans to disarm and release another 19 children from their ranks before the current conflict began.

The SPLA signed an action plan to work with the UN to end the recruitment and use of child soldiers in November 2009. This was followed by an updated version in March 2012 that promised that the SPLA would, with support from the UN, identify and report all children associated with the SPLA, allow UN officials and their child protection officers access to all training centers and military bases, and ensure disciplinary action was taken against “persons responsible for aiding and abetting the recruitment and/or use of children.”[15]

The action plan was quickly followed by a military order in April 2012 to screen and register all children in the rank and file of SPLA, promising ‘drastic administrative actions against each unit commander’ who failed to provide lists of names of screened children before April 2012. An order at the same time was also issued to allow unimpeded access for the joint UN-SPLA Child Protection Unit technical committee. [16]

In 2012, the UN was granted access to 71 SPLA barracks to verify whether children were present, and of 252 boys identified with the SPLA and affiliated militias, 230 were released and reunited with their families.[17]

With extensive support from UNICEF and the UNMISS, the SPLA Child Protection Unit also campaigned, often with success, to get soldiers out of schools. By the time the conflict began in December 2013, very few schools were being used for military purposes.[18]

The SPLA established a military justice section which, with UN and US donor support, trained some 100 judge advocates, and then deployed them to barracks across the country. However, these judge advocates have never attempted to prosecute any army official for recruitment and use of child soldiers.[19] Capacity building efforts have ground to a halt and both the Child Protection Unit and the military justice section have been in disarray since the conflict began. Some officers have either been killed or joined opposition forces, and UN and donor funding and in kind assistance to the units (for example flights) was suspended.[20]

The SPLA has also issued many military orders banning the recruitment and use of anyone under 18 years of age and the use of schools by SPLA members for any purpose. However evidence from the conflict indicates that the order was routinely violated and failure to comply with these orders has not been met by any sanction.[21]

Overview of Reasons Why Children Have Fought in the Conflict

Many boys have fought because they have been forced to, in the most brutal way. In many cases including dozens documented below, boys were recruited at gun point by soldiers, were arrested and then put in detention facilities until they agreed to fight or were simply abducted, handed a gun and then, sometimes within a day, thrown into battle. Around a third of the boys that Human Rights Watch interviewed who had fought in the recent conflict were forcibly, violently, recruited.

The continual failure of forces on both sides to distinguish between civilians and combatants explains why so many other boys have spent the conflict fighting, walking hungry across large areas of wilderness or, as one boy put it, “wasting” their educational years in military bases. The most cited reason for joining “willingly” (in the context of the conflict) was to provide for the best chance of surviving the war. Without the protection of a gun and an armed group, many boys believed they would have been even more vulnerable to being killed because of their ethnicity or assumptions about their allegiances.

In the wreckage of the conflict, some joined to access food or money. This was a reason given to Human Rights Watch only in a small number of the cases, but was often the case for very young or the poorest boys. In Bentiu, for example, Human Rights Watch documented several cases, described in more detail below, where boys as young as 12 years old and often from the poorest families or living without families, went to work for commanders as bodyguards or as servants. Poor conditions in the Protection of Civilians area in the UN Bentiu base also contributed to boys leaving to join armed forces.

Perhaps half the boys who spoke with Human Rights Watch said they joined armed groups not just to protect themselves but also out of a strong sense of responsibility to defend their communities and cattle from attack. Fighting has often been seen as part of fulfilling a necessary role, especially as army and police have done little over the years to protect communities, and a way to get a gun to be able to continue as a community protector –and sometime cattle raider –in the future. Child soldiers are not stigmatized in South Sudan and, although their loss of access to education is widely regretted, are usually seen as valuable fighters, not victims, at least in rural communities.[22]

Many boys who were recruited in the current conflict grew up in violence especially in rural areas where access to quality education and other opportunities are especially low. Many of the boys Human Rights Watch interviewed may have become involved in raiding cattle and protecting their cattle and communities from raids, even if the current conflict had not begun.

Boys between the ages of 14 and 18 usually viewed themselves as children, especially in the context of education, as members of an age set who would ideally be in school full-time. However, they also often perceived themselves as able warriors, and as such with a duty not only to those they loved, but also to themselves. “We feel fear sometimes [but] can control it, in our culture you cannot run they [our community] will insult you if you hide like a woman,” a boy who had joined a local defense force in Unity state told Human Rights Watch.[23]

Boys often said that a desire for revenge made them want to fight. In almost every case, boys who had willingly joined the opposition forces said they had done so out of a desire to avenge the killings of Nuer in Juba at the beginning of the conflict.

II. National and International Legal Standards

International law proscribes the practice of recruitment and use of children by armed forces or groups. It is a crime under international humanitarian law, the “laws of war”, and international criminal law to recruit or use children under 15 years of age. International human rights law prohibits the recruitment or use of all children, setting the age of lawful conscription or use of a person by armed forces or groups at 18 years of age or older.

South Sudanese Law

As well as efforts described above to end child soldiering, the South Sudan government has passed important legislation criminalizing recruitment and use of children under 18 by armed forces, in line with international human rights law.

The Transitional Constitution of South Sudan (2012) defines a child as anyone under the age of 18 and specifies that every child has the right “not … to be required to serve in the army”.[24]

South Sudan’s Child Act (2008) defines a child as anyone under the age of 18.[25] This law protects children from “service with the police, prison or military forces” and clearly states that the “minimum age for conscription or voluntary recruitment into armed forces or groups shall be eighteen years” and “no child shall be used or recruited to engage in any military or paramilitary activities, whether armed or un-armed, including but not limited to work as sentries, informants, agents or spies, cooks, in transport, as laborers, for sexual purposes or any other forms of work that do not serve the interests of the child.”[26] This law also explicitly lays out penalties for recruitment or use of a child in an armed force of “imprisonment for a term not exceeding ten years or with fine or with both.”[27] The Child Act also provides that “every child has the right to free education at primary level which shall be compulsory”, including for children with disabilities.[28]

Under South Sudan’s SPLA Act (2009) a person has to be 18 years of age or older to be eligible for enlistment. In September 2014, the office of the legal advisor of the Ministry of Defense recommended an addition to the SPLA Act, setting out possible punishments for child recruitment and occupation of schools and hospitals.[29] The amendment is currently with the Ministry of Justice and has not yet been voted on by South Sudan’s Legislative Assembly.[30] Its inclusion into the SPLA Act could technically help strengthen the Child Protection Unit, the Military Justice Unit and others to investigate and prosecute those who recruit children but only if there is adequate political support from the most senior levels of the army and government.

International Legal Standards

South Sudan has also acceded to a number of important international treaties and protocols that ban the use of child soldiers.

South Sudan became a party to the Geneva Conventions of 1949 and the additional protocols on January 25, 2013.[31] This international humanitarian law, and other customary international humanitarian law, prohibits recruitment of children under the age of 15 or their participation in hostilities by national armed forces and non-state armed groups.[32]

Such recruitment or use is also considered a war crime.[33]

Individuals who commit serious violations of international humanitarian law with criminal intent can be prosecuted in domestic or international courts for war crimes. States have an obligation to investigate alleged war crimes committed by their nationals, including members of the armed forces, and prosecute those responsible. [34] Non-state armed groups, like the opposition and their allies, also have a legal obligation to respect the laws of war, and leaders have a responsibility to ensure that commanders and combatants abide by its requirements.[35]

Other international law acceded to by South Sudan prohibits the use of children in conflict who are under the age of 18. South Sudan’s parliament ratified the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) and the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict on November 20, 2013 (‘the optional protocol’). President Kiir signed the instruments of accession five days later. However, the instrument of accession for the CRC was not deposited at the UN until April 2015 and the optional protocol has still not been deposited as of November 2015.[36]

Under the optional protocol governments must ensure that children under the age of 18 are not compulsorily recruited into armed forces, and must take all feasible measures to ensure that members of their armed forces who have not attained the age of 18 years do not take a direct part in hostilities. Under the protocol, armed groups that are distinct from the armed forces of a state may not, under any circumstances, recruit persons under the age of 18 or use them in hostilities.[37] The protocol also places obligations on governments to “take all feasible measures to prevent such recruitment and use, including the adoption of legal measures necessary to prohibit and criminalize such practices”.[38] Forces also have an obligation to provide children with special respect and attention.[39] The CRC requires that states ‘take all feasible measures to ensure protection and care of children who are affected by armed conflict’.[40]

South Sudan’s parliament has also agreed South Sudan would ratify the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child. This convention also sets the age-limit for recruitment and participation in hostilities at 18 years. However South Sudan is still not listed as having officially ratified the charter at the African Union.

The action plan that the SPLA signed with the UN in 2012 states that the signatories are guided by the Principles and Guidelines on Children Associated with Armed Forces or Armed Groups (the “Paris Principles”). This framework addresses the need for long-term prevention strategies in order to end the recruitment and use of child soldiers by armed forces and groups, including through accountability for abuse. The Paris Principles define children associated with armed forces and armed groups as “any person below 18 years of age who is or who has been recruited or used by an armed force or armed group in any capacity, including but not limited to children, boys, and girls used as fighters, cooks, porters, messengers, spies, or for sexual purposes”.[41] It does not only refer to a child who is taking or has taken a direct part in hostilities.

The Paris Principles also call for a child’s right to release from armed forces or armed groups including as conflicts continue.[42]

The right of South Sudanese children to education is enshrined in the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights and in the Convention on the Rights of the Child.[43] International humanitarian law states that children should continue to have access to education during periods of conflict.[44]

Students, teachers, and schools are protected under international humanitarian law.[45] Schools are presumed civilian objects and as such shall not be the object of attack unless they become legitimate military targets, for example, if they are being used as a barracks.[46] Intentionally directing attacks against a school not being used for a military purpose (i.e. so that is not a legitimate military target), including by destroying the school or part of it, or looting a school as has happened in this conflict in South Sudan, would constitute a war crime. Forces have a duty to take precautions to prevent attacks on civilians and civilian objects, including on schools under international humanitarian law.[47] Military use of school buildings, thereby stripping a school of its civilian status and rendering it a military target, undermines in practice the guarantee of protection given to all schools, thereby endangering civilians such as students and teachers who occupy schools.

In 2015, the UN Security Council encouraged all states “to take concrete measures” to deter the military use of schools in contravention of applicable international law by armed forces and armed groups.[48] On June 23, South Sudan endorsed the Safe Schools Declaration, an international political commitment that outlines actions states should take to strengthen the prevention of, and response to, attacks on schools and military use of schools, including by: incorporating protections for schools from military use into domestic policy and operational frameworks; collecting reliable data on attacks and military use of schools; investigating allegations of violations of national and international law against students, teachers, and schools and prosecuting perpetrators where appropriate; and seeking to continue education during armed conflict.[49]

III. Recruitment and Use of Child Soldiers by Government Forces

Human Rights Watch documented the use of child soldiers by government and military officials in Bentiu, the capital of Unity state and in neighboring Rubkona. Children were also recruited in large numbers by the SPLA in other parts of Unity state, especially forces under the control of Matthew Puljang, at time of writing the second in command of the SPLA’s Division 4.

The research found that children were often forced to join government forces or felt compelled to join due to the harsh conditions in UN Protection of Civilians sites and elsewhere. Some were subjected to abusive treatment, for instance being detained as punishment or as a way to force them to fight. Those who fought with the government were sometimes paid although irregularly and in very different amounts. Several received military training in Bentiu town, or in “Kotong,” a government military base and training camp, in northern Unity state.

Human Rights Watch also documented the recruitment of child soldiers by Johnson Olony in Upper Nile state, when he was fighting as part of the government forces there in early 2015.

Recruitment, Detention and Use of Child Soldiers in Bentiu

Numerous children have been used by both opposition and government forces to defend Bentiu town, the capital of Unity state.[50] The strategically important town, now mostly destroyed and pillaged during waves of attacks, has changed hands numerous times but has mostly been under government control since the conflict began, mostly under SPLA head of Division 4 Taib Gatluak Taitai. Child soldiers who have fought with government forces there reported “hundreds” of children in the main “Baa” barracks (located in neighboring Rubkona town). Government officials in mid-2014 estimated that there were as many as 200 child soldiers in the barracks at the time.[51]

The SPLA has used child soldiers on the frontlines to protect the town. For example, in August 2014, when the SPLA-IO attacked Bentiu and Rubkona, child soldiers fought with adult soldiers to defend it, according to numerous eyewitnesses. A 12-year-old boy told Human Rights Watch that during the early hours of August 15, as the opposition began their attack, an SPLA soldier ordered him and other child soldiers in Rubkona to shoot at the opposition forces, and that dozens of mostly older children were sent to fight at the Rubkona base.[52] A 15-year-old described fleeing the battle in Bentiu close to the front lines. “I ran and whenever I heard shelling I lay down,” he said.[53] Both described feeling intense fear.

The open use of child soldiers by government forces in Bentiu has continued, despite public condemnation from various international officials, UN, IGAD monitors and the Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Children and Armed Conflict, Leila Zerrougui.[54] For example, when Human Rights Watch was in Bentiu in February 2015, aid workers reported regularly seeing child soldiers, including positioned in defensive positions at the edges of the town.

Some children joined the SPLA looking for better conditions. For example, when Human Rights Watch was in Bentiu in mid-August 2014 Human Rights Watch also documented the recruitment of child soldiers by Johnson Olony in Upper Nile state when he was fighting as part of the government forces there in early 2015, at least seven children who had been living in the UN’s Protection of Civilian area had recently joined the SPLA. The boys, 11 to 14 years of age, joined because of the poor conditions in the base – which at the time was flooded, in places to adult knee height. At least three of the boys were also drawn by the promise of money or food. It was often the poorest children and those without family to look after them who were attracted to Baa. Fifteen-year-old O said:

It was my choice, I was not forced. … I went with my friends, we were a big group, around 10 of us, they were my age mates. One month they gave me 600 SSP, and then another time they brought us two months’ salary, 1,200. I was able to buy sorghum for my family. … So many street children have joined, to get food.[55]

“Life here is hard, that’s why they go and join the army,” said one friend of several child soldiers. “(DO) is only 14 years old … his father died and because of that he said he needs to bring money to the family,” one child’s mother said. She spoke to Human Rights Watch after her son had joined the SPLA for the second time together with his friend, also 14 years old.[56]

Commanders have used young children to wash clothes, cook, collect firewood and perform other duties. A 13-year-old boy said he was one of many children working for one of Matthew Puljang’s commanders (see below for more information on Puljang) in Bentiu. He said the commander had set up at the police station and that he was responsible for making tea and getting water.[57] “I went because of the flooding (in the UN base),” he said. He reported mixed feelings about his work; he said that he felt used by the commander, but also believed the man was trying to help him and the other children by providing them with some support. Another boy, 12-year-old M, who joined up looking for cash, cooked and carried water but told Human Rights Watch he had never been paid.[58]

Conditions of Life in the Bentiu Barracks

Human Rights Watch interviews with children who have been associated with armed forces in Bentiu suggest that the majority of the child soldiers have been located in the “Baa” barracks but others have been stationed in other buildings closer to the frontlines around the town. Many of the child soldiers who had worked in Baa reported getting some salaries, but often only once or twice over several months. All reported that they were fed regularly but often just sorghum. “We had only small amounts of food, less food than the adults,” said 12-year-old M.[59] “We were given asida (sorghum) but no soup. That was given to the big bosses,” O, 15 years old, told Human Rights Watch.[60]

Training in Baa seems to have been quite rudimentary, at least for the child soldiers, who mostly reported just being taught to load and unload a gun and to parade. “We were only given some training once, inside Baa, in a small field, about reloading a gun and putting it back down,” said MG, a 13-year-old.[61]

Six children who had been recruited into the government forces in Bentiu said that they had been detained while in Baa, a tactic apparently used as a way to prevent children from trying to escape and avoid fighting and in other cases as punishment.

GG, who was 15 years old when he was captured from SPLA-IO forces by government forces in October 2014, said he spent a month in the jail in Baa, together with other boys.[62] He said he and the other captured soldiers were caned while in detention, apparently to encourage them to agree to fight. Eventually they were released and then put into one of the government units. Another boy, 17-year-old JLP, who was forcibly conscripted by SPLA forces, was also put in the jail in Baa for about a month before being released so that he would join, not run away from, the forces.[63] “They thought I would sneak out,” he said.

A 14-year-old boy reported being put in the jail in Baa for two days “for not doing what I was told”.[64] KS, a 17-year-old, was captured in Bentiu town in April 2014, just ahead of a SPLA-IO attack on the town.[65] He was tied up with a rope to prevent escape and only untied when the attack was imminent.

Recruitment and Use by County Commissioners in Bentiu

Many children worked not with the SPLA directly, but with “commissioners” and other government officials as bodyguards and as servants, cooking, cleaning and performing other tasks for their ‘big man’. In South Sudan, commissioners are often former commanders who in times of war also perform a military function. Other children also confirmed that they had also seen groups of children working for these officials in Unity state.

According to three child soldiers who Human Rights Watch spoke to independently of each other, the former commissioner of Mayendit county, Ruai Gai, who was killed in battle in August 2014, used a group of child soldiers. Child soldiers reported that he took children with him into battle and said that least one child was killed, and others injured, in the attack that killed him.

Other commissioners who performed military functions are also reported to have used children, including the former Guit County commissioner, Kwai Chaany, and the former Leer commissioner, Taker Riek. “It was the commissioner [Chaany] who registered me,” said a 17-year-old, who also reported that other, younger, children were also being used by Chaany.[66] “Kwai took us with him in July (to fight) … many of us were child soldiers,” said another 17-year-old boy about a battle under the overall command of Manyuot “Nyaturoah” Monydhol Tiem, a commander in the SPLA who answers to Puljang.[67] A third boy also worked as a bodyguard for Chaany, who took him to battle in Guit county in September 2014 in an attack in which they also took thousands of head of cattle.[68] “We burned some huts too,” he said.

A 16-year-old, JM, told Human Rights Watch he fought under Taker Riek in 2014 during the government’s offensive into Leer county where he said he witnessed killings of civilians by the Darfur rebel group, the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM), who at the time were fighting with the government. “They were putting people in houses and putting fire on it … it was tora bora [JEM] who were doing this. The Dinka [government forces] were just collecting cows but they did not stop [the JEM soldiers].”[69] The boy later fought under Manyuot, including in the Unity oil fields and Panakuac. Taker Riek recruited another boy, JG, at 15 in Rubkona county. “Many of us were taken, big and small … one boy was killed when he refused to go,” he recalled.

A number of children reported that the commissioner of Rubkona County Apollo Mayen had a group of child soldiers working for him. One of the boys who worked for him, a 15-year-old, told Human Rights Watch that he was one of about eight boys working for the commissioner, sometimes paid.[70] “They sent us for laundry, cooking, but we also had a uniform and gun,” he said. During an attack on Bentiu by the SPLA-IO, Commissioner Apollo and the boys swam across a river to escape gunfire. The boy said one of his friends was shot and injured.

Another boy, 17 years old when Human Rights Watch interviewed him in mid-2015, had fought since January 2014, including in Mayom county and Bentiu and Tharjath towns under Manyuot with the government forces after being forcibly recruited. He said that he was also sent by Manyuot and Apollo Mayen to round up cattle from opposition areas.[71] Another boy who looked around 15 years old told Human Rights Watch that he had also been made to raid cattle under the command of Apollo Mayen and in one case under the overall command of Manyuot.[72]

A humanitarian worker told Human Rights Watch that his 13-year-old neighbor joined the SPLA in July 2014, under the command of Koch commissioner Kong Biel Char.[73]

Recruitment and Use by Matthew Puljang, Unity State

Human Rights Watch interviewed 22 children who fought with Matthew “Pul” Puljang or one of his commanders. Most said that they were recruited forcibly, often in brutal roundups. The boys, government officials and humanitarian workers from northern Unity state all told Human Rights Watch that they believe Puljang and his forces recruited hundreds of boys, especially from his home area of Mayom county in 2014 and 2015. Some of the boys were paid and received training.

Before the recent conflict, Puljang, from the Bul Nuer group, was an insurgent in a militia that used child soldiers.[74] His allegiance to the government in the recent conflict has been crucial for Juba’s control of Puljang’s home area of Mayom and a key road to Bentiu, the state capital.

Many boys were recruited from Mayom county. One 17-year-old said he and five other younger boys were recruited in Kuel village, Mayom county, as part of “massive recruitment” by Puljang’s forces in late January or early February 2014 and then put under Puljang’s deputy Manyuot.[75] “It was Pul who recruited us. …They told us ‘you have to be soldiers’ … we were given guns the same day,” he said, adding that at least two children, of about 14 years, were killed during fighting he later participated in over the state capital Bentiu. One boy, 17 years old when he was recruited in Mayom county while looking after cattle in early 2014, said that his brother, around the same age, was shot and killed during the recruitment.[76] “We were herding cattle … they shot him because he ran,” he said.

Two other boys told Human Rights Watch that they were recruited by a commander under Puljang in Nyibol payam of Mayom county.[77] Both were released after a school teacher intervened on their behalf but said scores of other boys were taken by the forces after they were collected and kept in a corral made of thorny sticks. One of the boys was in the corral for five days. “They brought us food and water but it was too small and everyone fought for it,” TC, 16 years old, described, adding that the heat of the sun in the corral was horrible.

Forced recruitment by Puljang and his forces went beyond the Mayom area.

One 15-year-old, GD, was captured in Bentiu town by a commander directly under Puljang together with two other boys and was then used as a cook, and to conduct reconnaissance around the edges of the town.[78] “They said we must join the army, if not they would beat us. My two colleagues refused to go and they beat them,” he described.

“Matthew Pul came with soldiers, first time to take arms from civilians, the second time to take property and cows and the third time there was recruitment both big and small people,” MM, 15 years, who was recruited from the Gezira area near Bentiu told Human Rights Watch.[79] “I was taken with my cousin (then 15 years old) from our family compound and put on the front line. … I saw Matthew Puljang when I was being recruited.” After being forcefully recruited, MM fought on the frontline defending Bentiu town, for example against an opposition attack in August.

Another boy who was 16 years old at the time was taken from Rubkona county by some of Puljang’s forces in January 2014 and sent to fight against the rebels in Mayom county under the command of Manyuot. He described the experience of fighting as harrowing. “They told us to kill everyone, whether civilian or not,” he said. “I saw civilians being killed.”[80]

Two boys, interviewed separately, described being forcibly recruited by Puljang’s forces, under the command of Manyuot, in Koch county, Unity state. “There are so many children with Puljang,” said L, a 17-year-old who in February 2014 was recruited together with 11 other boys by Manyuot’s men in Koch and then worked as a bodyguard for the commander with around 14 other boys.[81]

The second boy, 14-year-old BK, described how about 80 young men and boys were taken in February 2014 and then sent to fight in Tomor, between Bentiu and Mayom towns.[82] “Most frightening was the fighting in Tomor,” he said. He also described poor treatment of children in the forces. “They beat us with a black uncle (a plastic pipe) when we refused to do something,” he said.

Recruitment and Use of Child Soldiers by Johnson Olony, Upper Nile State

Forces under the control of Johnson Olony have recruited hundreds of child soldiers from the town of Malakal and surrounding areas during the current conflict. Olony who is from the Shilluk ethnic group was one of a group of at least four commanders in the rebel South Sudan Democratic Movement/Army group who in 2010 rebelled against South Sudan’s then semi-autonomous government.[83] Olony agreed to an amnesty deal with the government in 2013 and had been integrated with his senior commanders into the SPLA when South Sudan’s war began in December of that year. Until he defected from the government in April 2015 and began fighting government forces, he was a key ally for the government, helping secure Malakal town and surrounding areas.

On a research trip to Malakal in late January 2015, Human Rights Watch collected 25 accounts of child recruitment by Olony’s forces.

Some of the boys interviewed were taken forcibly by Olony’s men. A 20-year-old man said he had been picked up by soldiers in the town and thrown into a truck with six “small” children whom he believed to be around ages 13 to 15 years and driven to an area where fighting was taking place.[84] “When we got to Koka [the battle area] we were told to go to fight, given weapons, and attacked together with other soldiers,” he said. “We were given uniforms, almost immediately told to fight … all of us.” He reported seeing many child soldiers on the frontline.

A 14-year-old who was also captured in Malakal town in mid-January 2015 said that he was held for one night in a house with other men and boys who had been conscripted, but managed to escape while pretending he was going to bathe.[85]

One woman said soldiers captured her 13-year-old son at the riverside, where he was carrying goods for traders.[86] Another woman told Human Rights Watch that her son, also 13 years old, was also taken while working in Malakal town. “He used to go everyday with wheelbarrows to transport things… the other boys working with him said they saw him taken,” she said. [87]

Other children were forcibly recruited from right outside the UNMISS base where in early 2015 some 20,000 civilians were seeking shelter and the protection of UN peacekeepers. Human Rights Watch interviewed numerous witnesses who saw groups of armed and unarmed men from Olony’s force, some in uniforms, forcibly recruit both adults and children outside the gate of the base, which is also a busy market area, in late December 2014 and January 2015. Human Rights Watch confirmed 11 cases of children being taken by Olony’s forces from outside the UN base.

One boy, 17 years old, told Human Rights Watch about what happened to him after he was captured by Olony’s forces outside the UN base in September 2014:

They took us by force. (Then) they took us in a boat to Diteng. We got training in Diteng, how to use weapons, how to stand to attention, we were also in parades. I was (then) taken to Bakang, there was fighting there. There was one battle, it was two days long, I was shooting. There were many children fighting there. … Yes we saw Olony, he used to come to us in Diteng. He said we need to be strong. [88]

Another 17-year-old boy told Human Rights Watch that he was also captured from outside the UN base together with around 15 adult males in early January 2015, but managed to escape before being taken to the military barracks.[89] One woman told Human Rights Watch that her 13-year-old boy was taken on December 22, 2015, from outside the UN base.[90] She later went to Wardjok, across the River Nile from Malakal town where Olony had a military base, and saw her child in one of three boats full of dozens of children being taken southwards, presumably to the frontline, by soldiers.

A young woman said that recruiters took her 11-year-old brother just before December 25, 2014, from beside a pond close to the UN base.[91] Their mother later spoke by phone to her son, who was at Olony’s barracks across the river from Malakal.

Another mother told Human Rights Watch that some small boys told her that men had taken her 15-year-old son from outside the UN gate.[92] “The vehicle was full of people, they were all thrown in after capturing them, other small boys were also put in,” she said. “He never wanted to join the army.”

Other Shilluk boys appear to have joined Olony’s force willingly, or out of a sense of duty to help protect their community. For example, one mother told Human Rights Watch that two of her boys-- one 13 years old and the other 14 years of age—had left her home in the UN base in late December 2014.[93] “They left on their own, I was not informed. I don’t know why they went, maybe someone talked to them. I talked to one of the women who saw them in Wardjok … the place of Johnson Olony,” she said.

Olony’s forces recruited children before the December 2014-January 2015 recruitment drive described above. One 17-year-old boy said he was amongst around 50 children recruited from Wau Shilluk town in January 2014.[94] “We were trained (in) Kodok county, Johnson Olony was there … I was given gun and a uniform, there were many kids, they were getting children … We were taken to Binythiang, there was fighting there, near Akoka.”

Olony’s forces continued to recruit child soldiers in early 2015. In February 2015 UNICEF reported that Olony’s soldiers had abducted 89 children preparing for exams.[95] It is unclear what happened to these children although at least some of them were reportedly later released.[96]

IV. Recruitment of Use of Child Soldiers by Opposition Forces in Unity State

Human Rights Watch investigations into recruitment, including forced recruitment, and use of child soldiers by the SPLA-IO and their allies focused on Unity state where much of the fighting has taken place. Accounts suggest similar patterns of recruitment and use of child soldiers by opposition fighters in Jonglei and Upper Nile states. Child soldiers have been reported in the opposition held towns of Akobo, Lankien, Waat and in Uror county, in Jonglei state and in Nassir and Ulang, Upper Nile state.

In addition, youths who comprise the majority of the ‘white army’, armed Nuer men and boys allied with the opposition, come from Nuer areas that have remained largely unchallenged opposition strongholds. According to local and international humanitarians working in these areas, white army fighters have returned to their communities where they remain armed and primed to fight again if needed but are not formally part of the opposition forces.

Recruitment of Boys from Bentiu Town, Unity State

Mass forced recruitment of children in Unity state by opposition forces began in the first days of the conflict. On December 18, 2013, three days after the war began in Juba, defecting soldiers who would soon form part of the opposition forces under the command of Toar Nyuel abducted hundreds of boys from two schools in Rubkona town, adjacent to the state capital, Bentiu.

“There were maybe about 180 of us,” one 16-year-old boy who escaped the opposition forces many months later told Human Rights Watch.[97] The boys were taken in pickups and trucks to the Mayom area to the west of Bentiu where they were thrown into battles that lasted several days. GD, a 17-year-old student, described his experience:

I had no experience of holding a gun before. They told us this is how you use it, on the same day (we were captured) we had this training. Then we began fighting for Mayom, that took a day and then we captured it. Then we had to recapture it … seven boys were killed.

All three boys who spoke with Human Rights Watch about the mass abduction were later sent to Lony Lony, an opposition base and training camp in northern Unity state where they learned how to shoot guns with hundreds of other boys before being sent into other battles, including the April 15, 2014, attack on Bentiu town.[98]