Summary

The authorities, the public, and the militants are all hostile to us. We are like fish in poisonous waters, we can be attacked or killed at any time.

Journalist working in Galkayo, February 2015

On October 12, 2014, Abdirisak Jama Elmi, known as “Black,” a veteran journalist working for the private Somali Channel TV, was outside his home in Mogadishu when a man in a car started shooting. “As I was trying to escape the man started shooting automatic rounds and I felt as though he hit me about 10 times in my back,” Abdirisak said. “I could hear several voices telling the shooter to aim better. I could hear them saying, ‘He is still alive!’”

Bullets struck Abdirisak in the hand and several times in the back. He spent four months in the hospital and continues to receive weekly medical treatment. As a result of his injuries, he can no longer carry out his reporting activities.

Following the attack, government officials including the head of the National Intelligence and Security Agency (NISA) promised accountability. Yet, Abdirisak says he was never interviewed or asked to give a witness statement about his attack. He continues to live in fear: “The attackers are still alive, they know me and I don’t know them.”

In 2015, the New York-based Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) ranked Somalia at the top of its list of countries where journalists’ killings go uninvestigated. Since 2014, 10 journalists have been killed in Somalia, four in apparent targeted attacks. In addition, six journalists survived assassination attempts, and three have been injured while reporting. Scores have received threatening phone calls and text messages urging them to change their reporting or face the consequences. While Somali authorities have often committed to holding those responsible for attacks against journalists to account, accountability has been both extremely limited and uneven. For incidents of killings of journalists which occurred since 2014, there has been only one prosecution.

Somali journalists throughout south-central Somalia and Puntland told Human Rights Watch that over the last two years, freedom of the media has come under threat from all sides in ongoing fighting between governmental forces and various non-state armed groups. As Somalia prepares for an electoral process (without a popular vote) in late 2016, threats and attacks against journalists are undermining Somalis’ rights to basic and accurate information as media organizations censor themselves to survive.

This report focuses on abuses by state and non-state actors against journalists and other media workers since 2014. It is based on over 50 interviews with journalists working throughout south-central Somalia and Puntland, the semi-autonomous state in northeastern Somalia. Beyond killings, attempted killings, and a range of threats, the report also documents how journalists in the new interim regional states and in Puntland face unique obstacles that undermine their reporting.

Over the last two years, Somalia has experienced yet another period of heightened political and security instability since the collapse of the state in 1991. Politically, much of the recent attention of the Somali federal and regional authorities, as well as their donor and regional partners, has focused on efforts to establish a federal state system in Somalia with the establishment of interim regional administrations. This had been seen as a prerequisite for a political transition and a selection of a new government and legislature later in 2016.

Tight political deadlines around the establishment of federal states, and the framework for the 2016 electoral process, along with the armed conflict with Al-Shabab in many parts of south-central Somalia have all increased the importance of access to information and political control of news content. Hopes that the new authorities who came to office in Mogadishu in 2012, in Puntland in 2014, and within newly created interim regional administrations would bring respite to journalists have been dashed. The government, the interim regional administrations, and Al-Shabab have all sought to manipulate the media to shape public opinion and enhance their power at a heavy cost to media freedom and the safety and security of journalists.

The federal government and regional authorities have used a wide range of tactics to compel journalists to cover key issues in a way authorities deem acceptable. These include arbitrary arrests and forced closures of media outlets, threats, harassment, and occasionally the filing of criminal charges. Federal and regional authorities have temporarily closed 10 media outlets in 2014 and 2015. Intelligence service and security force officials have imposed bans on reporting specific issues, such as statements by Al-Shabab, and clamped down on media outlets that don’t comply with these orders. At the same time, threats, attacks and even killings go uninvestigated and unprosecuted.

Regional authorities in contested towns – such as Baidoa in 2014, and Dhusamareb and Guri’el in the central region in 2015 – arbitrarily detained, threatened and closed down media outlets to control political coverage, particularly on issues related to debates over federalism and the establishment of interim regional states. After some initial respite, the new authorities in Puntland have carried out a number of arrests, closure of radio stations and in one instance the pursuit of criminal charges against a media outlet.

Al-Shabab has not let-up in threats and attacks against journalists, treating them as extensions of the Somali government or foreign military forces.

Female journalists in Somalia face additional challenges. Along with the threats, intimidation, and violence faced by many journalists in Somalia, female journalists must contend with social and cultural restrictions, discrimination among their peers and targeted threats from Al-Shabab, which seeks to curtail women’s participation in public affairs through violence.

Government officials regularly seek to justify restrictions on freedom of expression on the basis of alleged unprofessional journalistic practices or national security grounds. While the authorities need to take into account valid security and privacy considerations, the restrictions documented in this report largely point to attempts by the authorities to obstruct legitimate reporting on key security and political developments. The tactics used are without legal basis, and place journalists at significant risk of reprisals.

Violence against journalists and other media workers that is uninvestigated and unpunished reflects wider impunity and general disregard for the rule of law in Somalia. Government investigations and prosecutions of targeted attacks on journalists have been sporadic and the only prosecutions that have taken place have been for killings claimed or believed to have been carried out by Al-Shabab. The federal government’s focus on incidents attributed to Al-Shabab and overreliance on NISA, which has no mandate to carry out law enforcement operations, to investigate these attacks contributes to one-sided accountability. Human Rights Watch identified only one killing of a journalist since 2014 that resulted in a prosecution. This case, as other recent cases attributed to Al-Shabab, was tried in the country’s military court, where trials do not meet international due process standards.

Human Rights Watch did not find evidence of any government official or security force member having been disciplined or charged for abuses against journalists in the past several years.

Because many attacks go uninvestigated, there has been speculation about the identity of the perpetrators. It also leaves survivors, such as Abdirisak, and other journalists living in fear of the next attack. As a radio manager in Mogadishu said: “When a close colleague is killed, you also worry for yourself, not knowing who the perpetrators are or what their motives might be. You worry even more as you can’t tell where the danger is coming from.”

Somali journalists and media editors admit to responding to the current hostile environment with self-censorship. Many steer clear of reporting on sensitive issues – including the armed conflict with Al-Shabab, politicized clan fighting and the federalism process – as a means to minimize risks to personal safety. Editors and journalists told Human Rights Watch that self-censorship has become a survival mechanism. As a Radio manager in Galkayo, Puntland said:

If I had only one enemy and if I saw accountability and justice for the murder of my friends, I wouldn’t censor myself... But now we face a very dangerous group that wants to interpret every single word in the media, that is Al-Shabab, and authorities that also want to oppress us instead of protecting us.

Somalia’s provisional constitution and international human rights law protect the right to freedom of expression, including for the media. Yet, several of Somalia’s national laws are inconsistent with the country’s international obligations. In January 2016, Somali President Hassan Sheikh signed off on a new media law that risks further hampering free expression. While the law offers some positive aspects, many restrictions on the media are broad and vague, including restrictions on “propaganda against the dignity of a citizen, individuals or government institutions,” and are likely to prompt further self-censorship as journalists are unable to determine what conduct is criminalized. The country’s penal code, which is under review, contains many provisions that render free speech a criminal offense, including “offending the honor and prestige of the head of state” and “contempt against the nation, state or flag.”

Somali federal and regional authorities should publicly commit to allowing full, open reporting and comment on issues of pressing public interest, including sensitive political issues. They should investigate alleged abuses by government security forces, including arbitrary arrests and closures of media houses, and take threats against journalists seriously. Prior to the electoral process, authorities should also review the new media law and the penal code to ensure all their provisions comply with international human rights law. Al-Shabab should immediately cease attacks and threats against journalists, regardless of their affiliation or gender.

International donors engaged in the media sector should support efforts to improve the security of journalists, press the Somali government to review laws that violate media freedom, and provide technical assistance to carry out thorough, transparent and rights-respecting criminal investigations, including into attacks against journalists, so that perpetrators – regardless of affiliation – can be held accountable.

Recommendations

To the President of Somalia

- Publicly condemn all attacks on journalists and media organizations. Issue a clear and public statement to all government and security force officials prohibiting any acts of intimidation, threats, harassment, and arbitrary arrests of journalists and media workers, and state that such incidents will be immediately investigated and appropriately disciplined or prosecuted;

- Publicly support the right to freedom of the media, including public reporting of sensitive political and other issues;

- Transfer existing cases of civilians facing trial in military courts to the civilian criminal justice system. Direct the military attorney general to transfer future cases of civilians under military court jurisdiction to the civilian courts for prosecution;

- Proactively support legislative reforms regarding the new media law and role of security agencies, outlined below;

- Immediately commute pending death penalty sentences as a first step towards placing a moratorium on all death sentences; urge the parliament to enact legislation banning all use of capital punishment.

To The Somali Federal Parliament

- Promptly and comprehensively review the penal code, the new media law and other legislation, and revise them as necessary to bring them into line with Somalia’s international obligations regarding the right to freedom of expression and the media; ensure that any restrictions on media freedom in the law are necessary, proportionate and least restrictive;

- Enact a rights-respecting national security law, as set out in the provisional constitution, that defines the mandates of national security agencies and clarifies that the National Intelligence and Security Agency is not empowered to arrest and detain;

- establishes a robust, independent body with a broad mandate and enforcement powers in accordance with the Paris Principles on National Human Rights Institutions.

To the Minister of Internal Security

- Direct the National Intelligence and Security Agency (NISA) and the police leadership to use all available supervisory and disciplinary mechanisms to ensure that NISA and police officers fully respect the rights of journalists and media workers;

- Ensure that NISA cease further arbitrary closures of radio stations and television stations without a court order;

- Ensure that the police, notably the Criminal Investigation Department (CID), promptly and impartially investigate credible allegations of threats or violence against journalists and media outlets;

- Discipline or prosecute as appropriate any police or NISA officer, regardless of rank, who is complicit in abuses against journalists or fails to adequately investigate alleged threats or violence against journalists;

- Ensure that security forces engaged in law enforcement activities are appropriately trained on issues regarding media freedoms.

To the Minister of Justice

- Cease further arrests of journalists and media workers and closures of radio stations and television stations without a court order.

To the Minister of Information

- Promptly review the media law and seek the revision of any provisions that violate the right to freedom of expression, and ensure that any restrictions on media freedom are necessary, proportionate and least restrictive;

- Ensure that the regulatory mechanisms are independent and promote self-regulation of the media;

- Ensure that the nomination of the Somalia Press Commission is independent by amending the current law so that the government no longer participates in the nomination process or otherwise inappropriately interfere in the work of the commission;

- Seek donor support for a public education campaign on freedom of expression, including the role of the media.

To Puntland, interim regional authorities and Ahlu Sunna Wal Jama’a

- Publicly support the right to freedom of the media, including public reporting of sensitive political and other issues;

- Ensure that regional police forces, promptly and impartially investigate credible allegations of threats or violence against journalists and media outlets;

- Ensure that any government or security officials found responsible for obstructing, abusing, or attacking journalists or media organizations are appropriately disciplined or prosecuted;

- Cease arbitrary arrests of journalists and media workers and closures of radio stations and television stations;

- Puntland should promptly review the media law to revise any provisions that violate the right to freedom of expression, ensure that any restrictions on media freedom in the law are necessary, proportionate and least restrictive.

International Donors, including members of the Somali Media Support Group (SMSG)

- Publicly express concerns regarding violations of the right to freedom of expression, and urge the Somali government to publicly call on all government and security force officials not to harass or threaten journalists and other media workers, in particular in the run-up to the 2016 electoral process;

- Publicly press the Somali government to reform laws and regulatory institutions to bring them into compliance with Somalia’s human rights obligations; provide technical support and assistance to these efforts;

- Support appropriate training for police and security officers and for judicial officials on freedom of expression and media freedom;

- Provide technical expertise to Somalia’s Criminal Investigation Department (CID) to carry out thorough, effective and rights-respecting investigations;

- Support efforts to ensure that military courts act in accordance with international fair trial standards;

- Support local civil society groups, including media support organisations, to carry out systematic monitoring and reporting of freedom of expression abuses throughout the country;

- Enhance support to journalists throughout the country requiring legal, medical and psychological assistance, notably via international and local media support organizations.

To UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO)

- Continue to provide training to members of the state security services and justice officials on freedom of the media throughout south-central Somalia and Puntland.

To the UN Department of Political Affairs and Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR)

- Ensure that the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) presence in the UN Assistance Mission in Somalia (UNSOM) has sufficient resources, staffing and capability to significantly increase human rights monitoring;

- Ensure that UNSOM human rights section regularly and publicly reports on the situation of human rights in Somalia.

To Al-Shabab and its affiliates

- Cease all attacks and threats against civilians, including journalists and media workers and media outlets, including those linked to the government.

To Somalia’s Journalist Organizations

- Ensure that the process of drafting the code of ethics for journalists and media organizations is independent and transparent;

- Promote the voluntary publication of corrections for inaccurate or unfair statements;

- Monitor abuses against journalists outside of Mogadishu and the major urban areas in Puntland;

- Encourage federal and regional authorities to carryout effective, thorough and transparent investigations into abuses against journalists and media workers.

Methodology

This report is based on interviews with over 50 Somali journalists and editors between January 2015 and April 2016. The interviews were conducted in Somali or in English, in person in Somalia and Kenya, or by telephone.

Human Rights Watch interviewed Somali government officials, including the federal minister of information, the minister of internal security, the minister of women and human rights, and the federal attorney general. Human Rights Watch also spoke to the district police commissioner in Baidoa, and the Ahlu Sunna Wal Jama’a (ASWJ) spokesperson charged with media affairs to follow-up on specific incidents.

In addition, Human Rights Watch interviewed a dozen media activists, representatives of international organizations and donors engaged in the media sector.

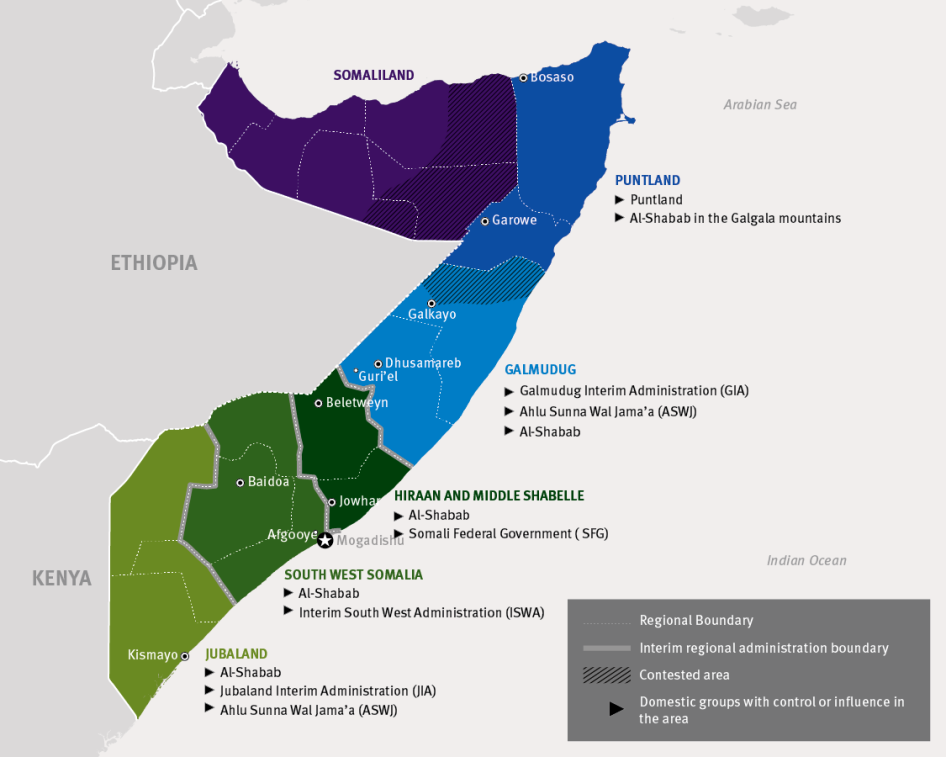

Human Rights Watch interviewed journalists from Afgooye, Baidoa, Bosaso, Beletweyn, Dhusamareb, Garowe, Galkayo, Guri’el, Jowhar, Kismayo and Mogadishu. Due to security concerns, Human Rights Watch did not interview journalists actively working in areas controlled by the Islamist armed group Al-Shabab. A number of the abuses documented in this report have occurred in towns that fall under the administration of interim regional states that have been set up in Somalia since 2013. These administrations are establishing structures similar to the central government, with presidents, cabinets and parliaments. Yet, as with the central government structures, functionality and control of these administrations over their territory is limited.

The majority of journalists interviewed by Human Rights Watch were under 25 years of age, this was not deliberate and highlights how young many journalists currently operating in Somalia are. Most had only completed high school, and had only ad-hoc journalism training, if any at all.

Interviews took place with journalists working for both government-owned stations and privately-owned media houses, though a majority worked for privately-owned houses. No compensation or any form of remuneration was offered or provided to any person interviewed for this report.

Human Rights Watch on March 30, 2016 wrote to the head of the National Intelligence and Security Agency (NISA), Col. Abdirahman Mohamed Turyare, to the head of the military court, Col. Liban Ali Yarow, and the head of the first instance level of the military court, Col. Hassan Ali Noor “Shuute,” and to the Puntland Minister of Information, seeking the government’s response to our research findings. (Copies of letters are included in the Annexe.) Representatives of both the military court and NISA emailed Human Rights Watch to say that they would not respond to research queries in writing. At the time of writing there has been no response from the Puntland Minister of Information or other government representatives in Puntland to whom Human Rights Watch has written.

Human Rights Watch also reviewed a range of published material, including academic research, relevant reports and statements by Somali and international media rights organizations, and articles published in Somali and international media as well as postings on Facebook and other Internet sites.

Given the ongoing dominance of broadcast media across south-central Somalia and Puntland, this report focuses on threats, harassment and attacks on broadcast journalists since 2014. It does not purport to offer an exhaustive list of all the attacks on media freedom in Somalia. More work is needed on the situation facing social media journalists and activists in Somalia, as social media is becoming an increasingly vibrant source of news and discussion.

With some exceptions, in the report, government officials are referred to initially with their full name and then with their first two names. Journalists are referred to with their full names and subsequently with their first name. It is common for Somalis to be given a nickname, which they regularly use; nicknames are included when the individual was commonly referred to as such.

We have removed identifying information for many of interviewees referred to in this report to protect their identity and to prevent possible reprisals. Real names have been used in cases where the incidents described have already been published in the media and when the journalists themselves asked to be named.

Glossary

Al-Shabab Islamist armed group controlling much of the countryside and key supply routes in south-central Somalia

ASWJ Ahlu Sunna Wal Jama’a a Sufi Islamist group that controls two towns in Galgadud region

CID Criminal Investigation Department, part of the Federal Police

NISA National Intelligence and Security Agency, Somalia’s intelligence service

Somalia’s internationally recognized administrations include:

SFG Somali Federal Government, which came to power in 2012 after the end of the transition period, and is based in Mogadishu

GIA Galmudug Interim Administration, interim administration comprising regions of Galgadud and part of Mudug

IJA Interim Jubaland Administration, interim administration comprising regions of Lower and Middle Juba and Gedo

ISWA Interim South West Administration, interim administration comprising regions of Bay, Bakool and Lower Shabelle

I. Background

War, federalism and risks for civilians

Since the fall of the Siad Barre regime in 1991, state collapse and civil war have contributed to making Somalia one of the world’s most enduring human rights and humanitarian crises. Successive armed conflicts have resulted in rampant violations of the laws of war, including indiscriminate attacks, unlawful killings, rape, torture, and looting, committed by all sides, causing massive civilian suffering.[1]

An internationally supported government that took office in 2012 has not brought an end to the volatility and insecurity in the country. The government, backed by the African Union Mission to Somalia (AMISOM)[2] and the Ethiopian armed forces, remains at war with the Islamist armed group Al-Shabab, which controls large swathes of territory and many key transport routes. While Al-Shabab lost control of a number of towns over the last two years, it continues to carry out targeted attacks on civilians and civilian infrastructure in the capital, Mogadishu, and other towns under government or allied authority.[3] Since 2015, the group has increased high-profile attacks on AMISOM facilities.[4]

Politically, much of the recent attention of the Somali federal and regional authorities, as well as their donor and regional partners, had focused on efforts to establish a federal state system in Somalia with the establishment of interim regional administrations. This had been seen as a prerequisite for a political transition and the selection of a new government and legislature later in 2016.[5]

This has resulted in tension and on occasion violence in which civilians have been the targets, particularly in Lower Shabelle and in the central regions. In December 2013, for example, government forces attacked a local militia in KM-50 village, and beat residents, looting and burning homes and shops.[6] Several civilians were reportedly killed and many civilians fled the area. While open conflict in this region has subsided, the creation of the Interim South West Administration has not resolved political infighting.[7]

In February 2015, fighting in Guri’el between government forces and the Ahlu Sunna Wal Jama’a (ASWJ), a Sufi militia, resulted in civilian deaths and massive displacement. According to the United Nations, about 90 percent of the estimated population of over 65,000 temporarily fled.[8] ASWJ continues to control the towns of Dhusamareb and Guri’el in the Galgadud region.

Puntland’s political landscape

Puntland, in northeastern Somalia, declared itself a semi-autonomous state in 1998, but recognizes its status as a constituent part of the Somali state. In 2013, scheduled local elections were indefinitely postponed, heralding the way for the selection of a new president, Abdiweli Abdi Gaas, in January 2014 and a parliamentary speaker selected by local clan elders. [9] In recent years, Puntland experienced an increase in Al-Shabab activity in the Galgala mountains near the town of Bosaso in the northeast of Puntland. In March 2016, Al-Shabab attacked several coastal areas in central Puntland.[10]

The Puntland government initially rejected the formation of the Galmudug Interim Administration (GIA), which borders and shares the Mudug region with Puntland, saying it was unconstitutional.[11] In late 2015, simmering tensions between the two administrations resulted in open warfare when Puntland forces repeatedly clashed with forces from the newly formed Galmudug regional administration in the contested town of Galkayo, leaving at least nine civilians dead and dozens injured.[12] According to the United Nations, the fighting displaced at least 90,000 people.[13]

Media in Somalia

During the Siad Barre regime from 1969 to 1991, independent media was largely nonexistent and state control over the media was stringent. Following Barre’s fall, the media was unregulated and private media ownership expanded. In the 1990s, warlords vying for power in Mogadishu established many newspapers and radio stations for propaganda purposes.[14] During the 2000s, newspapers declined, the radio was the most widespread medium for news and a few local and satellite TV stations were established. In this period, the media is reported to have been used as a tool by parties to the conflict and, at least to some extent, was perceived to be a driver of conflict, while journalists were targeted with violence.[15] Throughout the conflict, the media has been a key propaganda platform for all parties – for those in power and for insurgents – to communicate their voices and messages to the public. At the same time, journalists have often been the only actors on the ground seeking to fill a void of information so key to surviving decades of war.

Given the oral culture, high illiteracy rates, and cost of other mediums, radio remains the most prevalent source of news. The lack of a functioning radio licensing system has contributed to creating a media landscape that is constantly changing as radio stations are opened and closed, particularly at the local level. Few radio stations have national coverage.[16] The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) Somali service remains the most widely listened to radio station, including via local FM relays.

Given the relative stability in Puntland, a number of radio stations sprung up from mid-2000s and continue to broadcast to date.[17] At the same time, government control and restrictions on the media have increased, with a number of arrests and closures of outlets during the administration of President Abdirahman Mohamud Farole from 2009 to 2014.[18]

Since 2012, following the formal withdrawal of Al-Shabab from Mogadishu, the selection of a new federal government, and the return of many people from the diaspora, many new radio stations with affiliated websites have been established in towns throughout south-central Somalia. By 2015, there were about 50 radio stations broadcasting across south-central Somalia and Puntland.[19] Radio stations remain concentrated in Mogadishu and in Bosaso and Galkayo in Puntland, with reporters in regional towns, although there are also a multitude of local radio stations throughout government-controlled towns in south-central and Puntland.[20]

Somali language satellite TV channels have also become increasingly popular, with London-based Universal TV spearheading the way since it was established in 2005.[21] The reach of television is still limited, primarily to larger urban areas and for more privileged sections of society. There are currently only a handful of newspapers in south-central Somalia and Puntland.[22]

Websites that report on Somali current affairs, as well as blogs, have proliferated and most of the main radio stations also run websites; Internet access remains limited.[23] Social media usage has grown considerably, particularly among the Somali diaspora and young and urban-based population.[24]

Ownership and ethics

Despite the vibrancy of the media scene, Somalia journalists operate in a very precarious chaotic, politicized, and often outright hostile environment. Media ownership in Somalia remains controversial, with ownership even of the more established and professional media outlets often being along clan or political lines. Many perceive, rightly or wrongly, media owners to be pursuing business, political, or, although reportedly to a lesser extent in recent years, clan interests.[25] Some journalists told Human Rights Watch that negative social perceptions of the media, and mistrust within the wider public also undermine their security.[26] Some government officials, journalists and international media experts, in turn, told Human Rights Watch that many journalists lacked professionalism.[27]

Given the dangers of practicing journalism in Somalia, many trained and educated journalist have fled Somalia over the last decade. According to the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), at least 70 Somali journalists went into exile between 2008 and mid-2013.[28]

Journalists in Somalia rarely carry out in-depth investigative reporting and tend to focus primarily on news items and official version of events. Most Somali journalists earn very little or work for free.[29] Owners often rely on volunteers to work for them, making those working for media houses vulnerable to being used by politicians and armed groups. Journalists told Human Rights Watch that they cannot complain about their pay or risk being replaced.[30] Journalists therefore continue to rely heavily on trainings and bribes (commonly known as “sharuur,”) from government officials, clan representatives and even nongovernmental organizations, as a way of making a living.[31]

Somalia has a number of media organizations that advocate on behalf of journalists and media owners. Infighting within and between media organizations has on several occasions undermined their work and credibility.

Propaganda war between the government and Al-Shabab

Both Al-Shabab and the Somali government and its allies have relied on the vulnerabilities and weaknesses of the Somalia media to meet their own ends. In the public relations war, each side uses the media to communicate both real and false military successes in the war, manipulate the public’s access to causality numbers and obstruct factual investigations, all of which has greatly affected the media environment in south-central Somalia and Puntland.

Al-Shabab frequently publicizes its interpretation of events, to counter narratives by Somali authorities and the African Union forces in Somalia (AMISOM), releasing statements and videos in Somali, English and Kiswahili. [32] Al-Shabab also relies on the media to broadcast Islamic religious teachings from its perspective and to inform the public about governance issues in areas under its control.[33]

In 2009, Al-Shabab established its own radio station, Al-Andalus, which remains the group’s main mouthpiece, and later a TV station, al-Kataib.[34] There are a number of websites affiliated with Al-Shabab that publicize its statements and interviews Al-Shabab spokespeople. The group also maintains social media accounts.[35] Al-Shabab has coerced local journalists into working for them, imposed strict regulations on content including banning music, and raided and looted broadcast equipment, in some instances it forcibly took over media outlets.[36] This led to the closure of several stations, including one of the country’s oldest private media outlets, HornAfrik.[37]

Federalism in SomaliaThe process of establishing a federal framework in Somalia has in principle been underway since the early 2000s under the Transitional Federal Charter, however it has only really been implemented in the last four years, with the endorsement of the provisional constitution and the end of the transitional period in 2012.[38] Three provisional interim regional states, aspiring to become federal member states, have been established. In 2013, the Interim Jubaland Administration (IJA) was set-up comprising Gedo, Middle and Lower Juba;[39] following that the Interim South West Administration (ISWA) administration was set up, compromising of Lower Shabelle, Bay, and Bakool in 2014;[40] and finally in 2015, the Galmudug Interim Administration (GIA) was established, made up of Galgadud and the southern part of Mudug.[41] Discussions have been ongoing at time of writing over a possible state compromising of Middle Shabelle and Hiraan. The status of Mogadishu has still not been resolved. The model of federalism to be established in Somalia has not been defined, prompting significant tensions around the process. The provisional constitution of Somalia has vague provisions on federalism giving room for competing interpretations, including on how federal member states should be formed.[42] At the same time, the current expedited process of drawing up new interim regional states has brought to the fore many underlying causes of conflict.[43]The process has also been criticized for being top-down, pushed by international and regional partners,[44] and often overlooking smaller clans and groups considered as minorities in the country. |

II. Abuses against Journalists in South-Central Somalia and Puntland

Various actors inside and outside the government vying for control of the public sphere in Somalia have targeted journalists through various means. Radio and TV journalists have faced threats, harassment, and physical attacks, including assassinations. The state authorities have carried out arbitrary arrests, censorship and temporarily closed down media outlets. Al-Shabab and allied groups have threatened and attacked journalists as part of their campaign against Somalia’s federal and regional authorities.

Killings and Attempted Killings

For years, Somalia has been one of the most dangerous countries in the world to be a journalist. According to CPJ, which tracks journalists fatalities, including when they are killed for their work, 41 journalists have been killed in Somalia since 1992, and 22 of them just since 2012.[45]

Since 2014, at least 10 journalists have been killed, six in Mogadishu. Four journalists were killed in apparently targeted attacks,[46] six in indiscriminate attacks,[47] including one reporting at the scene of an attack.[48] In addition, at least six journalists survived targeted attacks in Mogadishu, three journalists were injured while on a reporting assignment,[49] and two were injured in a grenade attack on a radio station in Galkayo.

Assassination attempts and other attacks on journalists form part of a wider pattern of attacks directed at specific civilians, including lawmakers, government officials, traditional elders, and sheikhs.[50]

Human Rights Watch was not able to determine whether specific targeted attacks were directly related to the victims’ recent reporting, but journalists interviewed, including survivors, believed that this was the case. Al-Shabab claimed responsibility for one killing of a journalist in 2015.

Targeted Attacks

On December 3, 2015, a car bomb killed 31-year-old reporter Hindiya Haji Mohamed, who worked for the state-run Radio Mogadishu and Somali National Television (SNTV), near KM4 in Mogadishu’s Hodan district. Hindiya, a mother of five, had been preparing for exams at Somalia International University (SIU), and was a widow of another journalist, Liban Ali Nur, who died in an attack on a popular restaurant on December 20, 2012.[51]

Al-Shabab’s military spokesperson, Sheikh Abdiasis Abu Musab, broadcast on Al-Andalus radio to claim responsibility for the attack, accusing Hindiya of being an “intelligence officer” for the government.[52] A relative of Hindiya’s believed the killing was linked to her work for the state-run media:

Al-Shabab said: "We killed a female officer working for the government." The term “officer” is a word they give toall civilians working for government agencies. They use that term in order to justify their targeting. But Hindiya was a reporter and program producer.[53]

One colleague said that Hindiya had been threatened several times since her husband’s death.[54]

Unidentified gunmen killed Daud Ali Omar and his wife at their home in the Bardale neighborhood of Baidoa in the early hours of April, 30, 2015. Daud was a reporter and producer of the Fanka iyo Suugaanta program (“Fun and Music”) at the privately owned Radio Baidoa. Their neighbor, Ali Gaab, was also killed in the attack. A journalist who went to the scene of the killing the following day said the house had been sprayed with bullets.[55]

Colleagues said that Daud had been receiving threatening text messages from individuals claiming to be Al-Shabab members.[56] They believed that Daud was killed because of his decision to ignore the threats and to continue to host his radio show, which aired music that Al-Shabab has sought to ban for years. They also thought he was an easy target because he lived in a house without any security.[57] The district police commissioner in Baidoa told Human Rights Watch that on the night of the killing, police pursued the armed men who carried out the killing, and engaged them in a firefight but the assailants escaped. He said that after this, no investigation was opened.[58]

On November 18, 2014, Abdirisak Ali Abdi “Silver,” a reporter working at the privately owned Radio Daljir in the Puntland-controlled side of the contested town of Galkayo, was shot by unidentified gunmen at a restaurant and reportedly died of his injuries at a hospital located in the same town .[59] The reason he was targeted remains unknown, although a close colleague told Human Rights Watch that Abdirisak had been receiving threats from anonymous callers claiming to work for Al-Shabab.[60]

On June 21, 2014, Yusuf Ahmed Abukar, a prominent reporter known as “Keynan” was killed by an improvised explosive device planted in his car in the Hamerweyne district of Mogadishu.[61] He was an editor at Radio Mustaqbal and a reporter with the humanitarian Ergo Radio. No group claimed responsibility for his killing and the reasons behind his death remain unknown. [62] Following the killing, the government committed to investigating the attack. [63] Human Rights Watch was not able to confirm whether any investigation was opened or prosecutions carried out.

Since 2014, two other individuals linked to media outlets were shot dead in Mogadishu. Mohamed Omar Mohamed, who worked in the marketing section of Dalsan Radio,[64] was killed in April 2014, and Abdullahi Ali Hussein, who was believed to be a reporter with the controversial news website Waagasucub, was killed in September 2015.[65]

Attempted Killings

On July 25, 2014, bystanders warned Mohammed Abdullahi Haji – a journalist with Radio Mogadishu and SNTV – that they had seen individuals attaching something to his car, which was near his home in Mogadishu’s Waberi district. He went to a nearby police station to report the incident. Before the police had time to intervene, the device detonated, but no one was injured.[66]

Mohammed told Human Rights Watch he received a phone call after the incident from a journalist he knows worked for Al-Shabab warning him that next time he would be killed.[67] Mohammed said his lack of trust in the authorities discouraged him from seeking justice and asking the police to open an investigation.

On April 10, 2015, Farhan Saleban Dahir, a journalist and photographer with SNTV and Radio Mogadishu, survived an assassination attempt by two unidentified gunmen near the Casa Populare in the Hodan district of Mogadishu. Farhan told Human Rights Watch that he was shot six times and that one bullet remained lodged in his left hand.[68] The incident occurred near the Hodan police station, while he was on his way to visit a relative after work. He said: “I ran towards the police station, but the police opened fire, only stopping when they realized I was injured. The attackers escaped in the opposite direction.”[69] Shortly after the attack he received a message on Facebook, from a woman’s account, threatening him: “You have survived this time, but next time you won’t.”

Abdalle Ahmed Mumin, a veteran freelancer working in Mogadishu for two international newspapers the Guardian and the Wall Street Journal, said he started receiving threatening phone calls and Facebook messages in October 2014, after he published an article on the killing of Al-Shabab leader Ahmed Godane in an aerial drone strike.[70] On January 26, 2015, two assailants shot at his car. Abdalle told Human Rights Watch that he was driving home from Mogadishu’s Dharkenley district:

I saw a car with no number plate behind me. There were two young men, one was wearing black sunglasses, and one was wearing a green NISA uniform.[71] They shot at my car three times with AK47s (assault rifles), one bullet hit the backside of my car.[72]

Abdalle fled Mogadishu the following day and has been living in exile ever since.[73] Since he left, Abdalle said that unknown gunmen came to his family home in Medina district on two occasions, asking for him.[74]

Abdalle believes that the attack was linked to his reporting for the Wall Street Journal on Al-Shabab, particularly one article in which he discussed whether the group would splinter after Godane’s killing or would find a successor. While this is an issue often discussed by international reporters or experts, it’s rare to see a journalist in Somalia writing such an article for an international media outlet in his own name.

About 8 p.m. on November 9, 2014, Nuure Mohamed Ali, a freelance journalist, was on his way home when part of his car detonated:

I was driving when an explosion happened. All of a sudden, police from a nearby checkpoint started shooting at my car as they thought I was a suicide bomber. Then I realized that the explosion happened in my car. I saw smoke, and I tried to get out. But then realized one of my legs was missing. Luckily enough, I didn’t lose consciousness and got out of my car.[75]

Nuure lost his leg in the attack and spent two months in the hospital. He said that the authorities never followed-up with him following the attack and he wasn’t aware of any investigation.

On October 12, 2014, Abdirisak Jama Elmi (“Black”), a reporter and Mogadishu bureau chief for the privately run Somali Channel TV, was seriously injured following an attack by an unidentified gunman outside his home in Mogadishu’s Howl-Wadag district. Abdirisak said that a gunman, accompanied by several other men driving in a Toyota Carib, started shooting at him as he was outside greeting a neighbor, who was also badly injured in the attack. “During the shooting I could hear that several voices were telling the shooter to point his gun at me well. I could hear them saying, ‘He is still alive,’” he said.[76]

Abdirisak suffered injuries to his back, stomach and left hand and lost a finger. He is no longer able to carry out reporting activities because of the long-term effects of his injuries.

Abdirisak could not identify his attackers but believes the attack could be linked to an interview he did in 2013 with a woman who said she was gang raped by African Union forces at their Maslah base in Mogadishu. That interview had resulted in reprisals against a number of people involved in bringing attention to the rape. Abdirisak himself was questioned by a government committee set up in August 2013 to look into the incident during which security officials questioned him about his sources and the identity of the alleged survivor without legal counsel present.[77] In addition to his reporting, Abdirisak is also known as an outspoken critic of government restrictions on freedom of the media.[78]

Following the attack, the head of NISA, Col. Abdirahman Mohamed Turyare, reportedly visited Abdirisak in the hospital and committed to investigate the incident.[79] Abdirisak told Human Rights Watch that despite having relevant details to share, he has not been contacted by the authorities since he was hospitalized, and knows of no ongoing investigation.[80]

Three journalists told Human Rights Watch in Puntland that their names were on a “hit list” reportedly found by the authorities in Galkayo in February 2014 in the house of an alleged Al-Shabab member who was arrested in connection with the killing of a security officer.[81] The list reportedly included names of 12 journalists, including Abdirisak Ali Abdi (known as “Silver”) who, as described above, was killed in November 2014. One female journalist whose name was on the list described the anxiety she felt: “Finding your name on a kill list is not easy and when you have no police to report to, you must deal with pain.”[82]

Radio programmer Abdullahi Mohamud Adan and editor Shine Abdi Ahmed were injured in a December 31, 2014 attack when two hand grenades were thrown into the offices of Radio Galkayo in Puntland.[83] The station was attacked again on January 16, 2015, although no one was injured. This was not the first time the station and its journalists had been attacked.[84]

Awil Mohamud Abdi, director of Radio Galkayo, told Human Rights Watch that in the months prior to the attacks, he and the station had been receiving many threats from an anonymous telephone caller claiming to be affiliated to Al-Shabab in the Galgadud region. The caller was annoyed with some of the programs and talk shows the radio station had aired on security issues and complained that the station was not covering Al-Shabab press releases.[85] The station had hosted several security officials for discussions on insecurity in the region.[86]

Awil reported the threats to the authorities; the town’s police commander, Abdirashid Hassan Hashi, agreed to post three police officers at the radio station in late October 2014. Shortly after, one of the officers was shot dead by unknown assailants behind the station, and from then on the other officers did not return.[87]

Following the first attack, a group of youth in the vicinity were arrested but released shortly after as there was no evidence against them.[88] Awil told Human Rights Watch that after the attacks he repeatedly visited the police station, but the police never sought to get a thorough statement and would only tell him that they had not found anything.[89]

Journalists caught in the crossfire

At least one journalist has been killed and three others injured while on reporting assignments in the past two years.[90]

On November 1, 2015, freelance journalist Mustaf Abdi Nor, known as Shafana, was killed while reporting at the scene after an al-Shabab attack on the popular Sahafi hotel in central Mogadishu. Mustaf was taking photos from behind a car in front of the hotel when the car detonated.[91] Feisal Omar Hashi, a photojournalist for Reuters, was also injured in the attack.[92]

On October 19, 2015, Osman Adan Areys, a respected reporter with Somali Channel TV based in Beletweyn was shot in his left arm while covering violent clashes between the Gaaljecel and Baadicade clan militia at a checkpoint in Beletweyn.[93]

Arbitrary Arrests and Threats by Federal and Regional Authorities

NISA, regional police forces, and local militias have harassed, threatened and arbitrarily arrested and detained journalists and closed media outlets to prevent or discourage coverage of news events and as punishment. While the security forces are the visible face of these abuses, journalists told Human Rights Watch that senior government officials often issued the orders for actions taken against them.[94]

Arbitrary Arrests and Closures by Federal and Regional Authorities

Since 2014, government and security officials in Puntland and south-central Somalia regularly called in journalists for questioning and then arbitrarily arrested them. Criminal prosecutions of journalists are rarer, but in two cases in Mogadishu journalists have faced court cases, received prison sentences and significant fines.[95] Ten media outlets were temporarily closed in 2014 and 2015 in several towns across south-central Somalia and Puntland.[96]

Galgadud and Ahlu Sunna Wal Jama’a Clampdown

Between May and August 2015, the Ahlu Sunna Wal Jama’a (ASWJ) militia, a Sufi Islamist armed group that controls the towns of Guri’el and Dhusamareb in the Galgadud region, sought to restrict media reporting on the Galmudug interim state formation and security matters involving ASWJ. The group pressured local stations to sign up to their new media regulations, and carried out a string of arbitrary arrests of journalists and closures of local radio stations.

On May 16, 2015, Abdulkader Barre Gure, the deputy director of privately owned Radio Galgadud, based in Guri’el, received a phone call from a high-level ASWJ official ordering him to shut down the station.[97] The following day, ASWJ temporarily detained Abdulkader. On May 18, ASWJ forces raided the offices of Radio Galgadud and shut it down. The station was not reopened until May 31, after lengthy discussions with the authorities about the conditions placed on the station to be allowed to reopen.[98]

On May 18, Osman Mohamed Aden, a reporter for the state-run SNTV in Guri’el, was summoned by a police official and given an ultimatum to stop working for SNTV or leave Guri’el. Osman told Human Rights Watch that the ASWJ officials did not want him working for the state-run channel, as they wanted no relationship with the central government, accused him of being biased and questioned him about several of his stories and interviews.[99] Osman refused to meet their demands and in fear for his safety, left the area.

Over three days in late July 2015, ASWJ officials arrested six journalists in Dhusamareb.[100]

On July 31, Abdi Jamal Moalim from Kalsan TV and Radio Bar-Kulan, Mohamed Abdi Mohamed from Somali National TV, and Bashir Mohamoud from Horncable TV were arrested, after they reported on a demonstration in Dhusamareb in favor of the creation of the Galmudug interim state.[101] The following day, ASWJ security forces arrested two staff from the privately owned Radio Codka Bartamaha, Abdullahi Warsame Roble and Leylo Nor, after they released a news item on the journalists’ arrests.

Nafiso Hersi Ogle, the director of Radio Codka Bartamaha, told Human Rights Watch:

The day the first three journalists were arrested, I received a call from the district security officer [name withheld], who told me I couldn’t publicly report on the arrests in any of the media outlets I work with.

On August 1, at 9 a.m., about 16 gunmen surrounded our radio station. They told me they wanted to arrest Abdullahi Warsame Roble [a journalist at the station] but I told them that Abdullahi was in the studio reading the news.

The commander, [name withheld], ordered me to open the studio, but I told him we needed to wait for Abdullahi to finish. The commander opened the studio by force and tried to grab Abdullahi. I told him not to resist and leave. The mic was open and the whole town was listening.

The commander then closed down the station. On August 2, ASWJ security forces detained Nafiso Hersi.[102]

The six journalists, including Abdullahi, Leyla and Nafiso, were released on August 2 but ordered to appear before a judge on August 3. Four were brought before an ASWJ-run court that administers Sharia (Islamic law), presided over by an ASWJ official. The judge reportedly sentenced the four to two months in prison, without legal counsel, on charges of defying the orders of the local administration and airing information that could create unrest. However, he immediately pardoned and released them, following a request by the journalists’ relatives.[103]

In August, the ASWJ administration tried again to compel local media owners to sign onto new media regulations. On August 21, ASWJ forces again closed down Radio Galgadud branches in Dhusamareb and Guri’el and Star FM in Guri’el after the journalists decided to boycott ASWJ events and reporting on ASWJ activities for several days in protest.[104]

While the other stations reopened, Radio Codka Bartamaha remains closed. Nafiso told Human Rights Watch why they refused to comply with the administration’s restrictions and reopen the station:

We are a community radio, people wanted to hear what was going on at the time around the Galmudug interim state formation as there was a lot of tensions, but the local administration wanted to keep people uninformed. We also want to be able to cover the news on all the country, all regions, and so there is no point reopening the station if we cannot.[105]

Since 2014, the authorities in Beletweyn have arrested three journalists and temporarily closed down two radio stations.[106] On April 2, 2015, NISA members in Beletweyn arbitrarily arrested two journalists from Goobjoog radio, office manager, Abdirisak Mohamed Abdullahi “Al-Adala” and reporter Khalid Mohamed Osman, and ordered them to close down the station. Minutes earlier, the station had aired a story on a case of extrajudicial killing by militia linked to the self-proclaimed administration of the west side of Beletweyn, for which they interviewed a representative from this administration, seemingly giving him credibility in the eyes of the town’s official administration.[107] The journalists were held for three days in a NISA detention facility without charges or access to their relatives.[108]

Mogadishu and the NISA clampdown

Since 2014, the National Intelligence and Security Agency, which has no legal mandate to arrest or detain people, has temporarily closed down five media outlets and arrested dozens of journalists and managers that have been held from periods ranging from a few hours to several weeks in NISA facilities in Mogadishu.[109] Four journalists were sentenced under the criminal code and given prison terms of the time served and significant fines, after months in detention.[110] The chief justice of Somalia’s supreme court told Human Rights Watch that he had never granted any orders for these arrests and closures.[111]

In September 2014, NISA temporarily detained journalists and managers from Radio Simba, Kulmiye Radio and the state-run Radio Mogadishu after they broadcast the voice of an Al-Shabab spokesperson, following a ban by the head of NISA in Benadir on the broadcast of Al-Shabab statements; NISA ordered both Radio Simba and Kulmiye Radio off-air for several hours.[112]

Shabelle Network Station Closures and Prosecutions

NISA has arrested dozens of journalists from the Shabelle Media Network and shut down its stations, including Mogadishu’s once most popular station, Shabelle Radio, on three occasions over the past two years.

On August 15, 2014, NISA officials raided the Shabelle offices and its sister station, Sky FM, both part of the Shabelle Media Network, and arrested all 19 male journalists and media workers present at the time (female staffers present were not arrested).[113] They confiscated equipment and shut the stations down.[114] The raids and arrests came after controversial broadcasts by the two stations, including a live talk show on Shabelle Radio, discussing a security operation against a powerful warlord in Mogadishu, Ahmed Dai, that underlined the clan-dynamics around the operation.[115]

After initial questioning and detention at Godka Jillaow, one of the main detention facilities run by NISA, 16 of the journalists were released.[116]

On August 17, Abdimalik Yusuf Mohamed, Shabelle Media Network owner, and Mohamud Mohamed “Arab,” Sky FM director, and Radio Shabelle presenter Ahmed Abdi Hassan, who were still in detention, were taken to the Benadir Regional Court, and remanded for an additional 21 days.[117] They spent a total of 22 days in NISA detention. On September 6, they were formally charged and transferred to Mogadishu central prison.[118] On the same day, Shabelle Radio Producer, Mohamed Bashir Hashi, was also arrested.[119]

On October 21, 2014, Abdimalik and Ahmed were released on bail, after some of the charges against them were dropped. [120] Mohamud and Mohamed were detained for almost seven months. On March 1, 2015 Abdimalik, Ahmed and Mohamud were sentenced under the country’s penal code including for public instigation to disobey the law,[121] and “circulation of false, exaggerated or tendentious news capable of disturbing public order,”[122] sentenced to time served and given excessive fines.[123] The stations were off air throughout these months.

On April 3, 2015, NISA again raided and closed down Radio Shabelle and Sky FM and arrested a number of journalists present, once again without a court order.[124] Most staff were released, but NISA continued to hold Mohamed Muse, director of Radio Shabelle, and Ahmed Abdi Hassan, who had been sentenced in the previous case.[125] According to Ahmed, after two days in detention they were brought before the Benadir regional court and the court ordered their release stating that the accusations against them had no legal basis. NISA ignored the order and continued to hold them for another two weeks.[126] The arrests and closure came after Radio Shabelle broadcast an interview with Al-Shabab spokesperson Sheikh Ali Dheere, who claimed responsibility for the attack on Garissa University in northeastern Kenya, thereby violating a ban that NISA had imposed on the broadcast of Al-Shabab statements, discussed below.[127]

Universal TV arrests and closure

On October 2, 2015, the head of NISA, Col. Turyare, summoned Mogadishu director of the privately owned broadcaster Universal TV, Abdullahi Hersi Kulmiye, and presenter of the popular political talk show, “Doodwadaag” (“Debate”), Awil Dahir Salad, to the offices of NISA at Godka Jillaow.[128] On the same day, NISA forces raided the Universal TV offices and ordered journalists at the offices to close the station indefinitely, without a court order.[129]

The arrests and closure came after Doodwadaag hosted two Somali parliamentarians, Abdi Hashi Abdullahi and Mohamed Abdi Yusuf, for a live debate on September 30 during which speakers raised a series of issues critical of the government and president, and of the influence of foreign forces inside Somalia, particularly Ethiopia.[130]

Abdullahi told Human Rights Watch that he asked for a lawyer during their initial interrogation, but the NISA official interrogating them said that the questioning was only informal, and the two media workers did not need a lawyer. Yet, by the evening of October 2, NISA officials told them that they were under arrest. Abdullahi said NISA officials questioned him about the station’s programs, and particularly about “Doodwadaag” and a satirical political show, “Faaliyaha Qaranka” (“Nation’s Prediction”).[131]

The following afternoon, they were taken to the Benadir regional court, still without legal counsel. Abdullahi said that no one informed them of any charges against them when they appeared before court and that the judge granted NISA an additional 21 days to carry out the investigations.[132]

The authorities released Abdullahi and Awil on October 8. Attorney General Ahmed Ali Dahir told Human Rights Watch that formal charges were never brought against the two men.[133] The station reopened its Mogadishu office on October 10.

Four journalists arrested by NISA alleged mistreatment in NISA detention facilities in Mogadishu.[134] On February 11, 2014, director of privately owned Radio Danan, Mohamed Haji Bare, was arrested and held for two days in NISA’s Godka Jillaow detention facility, for taking photos of a deputy governor from Lower Shabelle immediately after he was injured by a car bomb. Mohamed told Human Rights Watch he was mistreated during his interrogation by NISA officials:

They started beating me and showing me a photo of the exploded car with a lot of bystanders and myself holding a camera and taking photos in the background. They asked me what I knew about the explosion.

They beat me for about 15 minutes until I lost control and fell down. They beat me with sticks, guns and kicked with boots as well. I was beaten only that time, but they hurt me pretty badly. All my body was in pain and some parts of my body were swollen.[135]

Puntland

Despite a lull in government-orchestrated restrictions on the media during the first year of President Abdiweli Mohamed’s term in office, the Puntland authorities have since temporarily detained a handful of journalists.[136] The Puntland authorities also temporarily shut down two media outlets in 2015 and pressed charges against one. The Puntland authorities appear particularly sensitive to issues that touch on government officials’ record in office,[137] Puntland’s reputation, and the implementation of the federalism model in Somalia.

On May 19, 2015, the Puntland deputy minister of interior ordered the closure of SNTV by publishing a letter in the local media, without giving prior warning to the SNTV management.[138] The order followed the broadcast of a report on the situation of refugees from Yemen in Bosaso, which the deputy Minister said damaged the reputation of the Puntland government. The official revoked the order within days.[139]

On October, 29, the Puntland Minister of information, Mohamud Hassan Soocade, sent a letter to Voice of America (VOA) prohibiting journalists from working with VOA in Puntland, ordering the closure of VOA offices and prohibiting the rebroadcast of VOA programs across Puntland.[140] The minister accused VOA of having made a “habit of reporting baseless and false reports, which pose damage to the dignity and statehood of Puntland.” The ban came one day after the speaker of parliament resigned, creating significant political tensions.[141]A VOA journalist in Puntland told Human Rights Watch their concerns about reporting on the issue before the closure: “When the spokesperson resigned, people were not happy. People were calling VOA but we were declining to interview them as we were scared our offices would be closed. We told them to call our colleagues in Washington, DC.”[142] The minister revoked his decision on October 31.[143]

Individual government officials and members of the judiciary also punish journalists for reporting they perceive as undermining their reputation, by ordering their arrest.

On May 27, 2015, VOA reporter, Fadumo Yasin Jama, said she received a text message from Ahmed Ali Ahmed, chairman of the Bari regional court of appeal, telling her to appear in court the following morning. When she appeared in court, the chairman ordered her arrest and that of a reporter with the Puntland-based privately owned radio station SBC, Yusuf Mohamud Yusuf, accusing them of having offended judges. Fadumo had recently filed an interview with Puntland President Abdiweli Mohamed in which he acknowledged public concerns with the judiciary.[144] Fadumo and Yusuf, who attended the trial and questioned the warrant of arrest against Fadumo, were taken to the Bosaso central police station. Fadumo said they were later released following pressure from her clan representatives and an official from the President’s office.[145]

On November 19 2015, the police in Garowe arrested Somalia Channel TV presenter Jama Yusuf Deperani after he hosted the minister of information on his talk show, and questioned the minister about a range of political and development issues in Puntland.[146] He was held for ten days in pre-trial detention, never brought before a court or given access to legal counsel.[147] According to the Media Association of Puntland (MAP), in August 2015, the government charged the media outlet, Sahan Radio, with criminal defamation and propaganda against the government, but the case was dismissed on the basis of lack of evidence by a regional court.[148]

Censorship

Security forces, notably NISA and local police forces, in south-central Somalia and Puntland have on several occasions since 2014 sought to control the content of media coverage of Al-Shabab and Al-Shabab activities. Such bans undermine the media outlets independence, limits the public’s legitimate rights to information, and put journalists at risk.

In 2014 and again in 2015, the NISA leadership in Mogadishu met with journalists and station managers and orally instructed them to stop reporting on Al-Shabab, and banned the airing of Al-Shabab voices.[149] According to the UN Independent Expert on the human rights situation in Somalia, no court had approved such a ban.[150]

Several journalists told Human Rights Watch that they attended a September 2, 2014 meeting, where the former head of NISA Benadir region, Col. Mohamed Adam Kofi, banned them from reporting on Al-Shabab activities, except from official statements from the Ministry of Security, broadcasting Al-Shabab statements and voices, and reporting on a new joint AMISOM- Somali government offensive against Al-Shabab. [151] When one journalist asked for an official document, he was told it was a verbal order.[152]

A journalist who was in the room, and later arrested when his station rebroadcast a VOA item with the voice of an Al-Shabab spokesperson, told Human Rights Watch: “He didn’t specifically threaten us with reprisals but we could understand from the language he used and the actions he later took when we accidentally aired the voice that this was a threat.” A media owner in Mogadishu said that a local NISA official visited his radio station shortly after the ban imposed by Kofi and gave the station a long list of restrictions with which to comply.[153]

In March 2014, the former governor of Hiraan, Abdi Farah Laqanyo, and the Djibouti contingent commander, Col. Osman Dubad, also banned journalists in Beletweyn from broadcasting Al-Shabab’s voices or information about their activities.[154]

In addition to the direct reprisals against journalists and media outlets that reportedly failed to comply with these orders, the broader impact on journalists’ reporting and security is significant. One journalist spelled out the dilemma such bans impose on journalists:

It undermines our freedom and also creates a mess, because even Al-Shabab then put out a statement saying that the media that obeys NISA orders will be targeted.[155] So, it is a dilemma for us to choose between the government’s jails and Al-Shabab threats and none of them are friendly at all.[156]

The radio stations that rebroadcast VOA and BBC programs find it particularly difficult to comply with these bans. One editor in Beletweyn said that the only way they get around this is by “cutting the stream and turning on commercials when they start a story about Al-Shabab.”[157]

Regional authorities have also sought to impose and control reporting around federalism. As described above, according to journalists in ASWJ-controlled towns, since mid-2015 the ASWJ spokesperson, Mursal Sheikh Mohamed Yusuf Hefow, has tried to impose new regulations on local journalists and stations, which included provisions prohibiting reporting on Galmudug Interim Administration and requiring that journalists seek permission to report on security incidents involving ASWJ forces.[158]

Threats

Many journalists who spoke to Human Rights Watch described receiving threats and warnings directly from government and security officials, as well as anonymous threats. They are threatened by phone and text messages, on occasion via email or Facebook. Government officials have also threatened journalists in person, or via allies. A journalist in Galkayo said:

Al-Shabab always use telephones. They either call you with unknown numbers or SMS you directly. When Al-Shabab is calling, they say who the caller is, and they always insult us, they use the words “apostate, spy, puppet” and other bad words.

When angry clan militia call, they don’t hide themselves. They say who they are and why they are angry. After that, they start threatening.[159] The politicians and business people are also like that. If they don’t call directly, their supporters call us and say “if you don’t stop so and so, you will die.”

Government and security officials threaten directly. They call the journalists, meet us and they dictate to us whatever they think their interest is. If you don’t obey they arrest you and if you obey them you annoy the opposite party and you receive serious threats. That is why Al-Shabab calls us puppets.[160]

Several journalists said these constant threats are much more detrimental than the more formalized bans on reporting on security matters.[161]

Journalists in Bosaso said that they were often unable to cover security incidents involving Al-Shabab that depicted the security forces in a negative light without receiving threats from the authorities. A reporter in Bosaso described the most recent incident he had faced after he asked the police commissioner for a statement on a recent security incident:

Last night [May 5, 2015] Al-Shabab ambushed a forces’ checkpoint in Bosaso. They killed three soldiers and destroyed two technical vehicles and injured many others. The story is there. When I called the police commissioner to ask if he could confirm that story, he said: “Yes, that is the reality, but why do you care, you can’t report it.” I asked him why, and he said, “I told you that no media can report it, if you report it you will pay the price.” I stopped reporting it, because if I report it I already know what the commissioner will do.[162]

The towns of Guri’el and Dhusamareb have changed hands several times since 2014, and journalists in these towns have been threatened by regional authorities allied to the federal government and members of ASWJ regarding their coverage of the parallel administrations in the region.[163] As a journalist in Guri’el told Human Rights Watch:

The major challenge in the region are the different administrations, ASWJ and the government. When one is in control, they don’t like journalists to cover the stories from the other side, they tell us not to cover stories, they tell us to air their stories. They threaten you and imply that if you air the stories from the other side, you support them.”[164]

When residents of Dhusamareb took to the streets in December 2014 to show their support for ASWJ, the head of the town’s administration, who was allied to the federal government at the time, called an editor working in Dhusamareb and warned him against reporting on the protests: “The story is not good for the town, nor the administration. If you air the stories, you will take responsibility for anything that can result from those reports.”[165]

Journalists in Baidoa received threatening calls from people on both sides of the political divide, including clan representatives, during discussions around the formation of a new state in southwest Somalia in 2014.[166] Several journalists in ASWJ-controlled towns and in Puntland received orders on how to report on the developments of the formation of the Galmudug Interim Administration.[167]

More generally, government officials throughout south-central Somalia and Puntland use threats to deter reporting that might reflect negatively on them. The breadth of issues deemed controversial is wide, making it very difficult for journalists not to run afoul of the authorities.[168]A journalist in Garowe said he was threatened in January 2015 by the town’s police commissioner to stop him from releasing footage of a protest by civil servants; the journalist then sent the footage to a friend to release. [169] He told Human Rights Watch that he subsequently received another threatening phone call from the police commissioner accusing him of being against Puntland.

Most threats go unreported and are dealt with informally, with discussions with clan representatives of the journalists, media outlets, or media owners.[170] This contributes to a context in which harassment and threats are normalized and go unpunished.

Restrictions on Access to Information

Journalists told Human Rights Watch that government and security officials in Puntland, Mogadishu, Baidoa and Beletweyn on occasion refused to provide basic information about security incidents or to accept interviews or denied them access to the scene of incidents or important events.[171] A journalist in Baidoa said:

The leaders of the district, financial department and other officials, don’t want to be interviewed by journalists. If you ask them for an interview, they don’t want to talk to you. But then you cannot criticize them, or they will threaten you, and tell you not to get involved in their affairs.[172]

On occasion, even though journalists are invited to cover events by government officials, the security forces hamper journalists’ ability to report. In June, 2015, at the height of the influx of Somali and Yemeni refugees into Puntland, a reporter working in Bosaso told Human Rights Watch that Puntland police forces prevented him from interviewing Yemeni refugees while covering the story at reception centers in Bosaso, despite being officially invited to cover the government response to the crisis.[173]

III. Al-Shabab Abuses against Journalists

The Islamist armed group Al-Shabab has repeatedly threatened and attacked journalists, often treating them as an extension of their fight against the Somali government and foreign forces in the country. Al-Shabab’s statements and own media outlets often refer to journalists as legitimate targets. They refer to journalists working for state-run media as “officers” and “spies” of the government or foreign forces and those working for private outlets as “puppets.”[174]

At the same time, Al-Shabab appears acutely aware of the power of the media, sees the media as an important propaganda platform, and seeks to pressure journalists into covering their statements or to not report on stories that depict them in a negative light, often using threats of violence.

Since 2014, Al-Shabab has claimed responsibility for one targeted killing. The lack of investigations into targeted attacks on journalists leaves open the possibility that the group has been involved in additional attacks against journalists.

Al-Shabab has also carried out a number of attacks in which journalists were among the civilian casualties. At least six journalists and media workers have died in attacks claimed by Al-Shabab on restaurants and hotels between 2014 and 2015.[175] When Al-Shabab claimed responsibility for these attacks, they often highlighted the number of journalists killed. On December 5, a cameraman with Kalsan TV, Mohamed Isaq, and a freelance journalist, Abdulkadir Ahmed, were among 13 people killed when a car bomb exploded outside a popular restaurant in Baidoa.[176] Three other journalists were injured in the attack. Al-Shabab claimed responsibility for the attack and claimed that the targets were “Ethiopians, spies and officials.”[177]

Several journalists told Human Rights Watch that they received death threats from individuals they knew or believed to be from Al-Shabab following attempted killings or Al-Shabab bombings.[178] A reporter in Baidoa who survived the December 5 attack said:

One day after the twin deadly attacks at the restaurant in Baidoa, someone claiming to be the head of AMNIYAT [Al-Shabab’s intelligence branch] in the region called me and started threatening me. He said to me: “You are at the burial of your friend who was killed in yesterday’s explosion. We wanted you to die, and if you survived yesterday you will not survive the next day.”[179]

In January 2015, the Puntland government forces transported four reporters into the Galgala mountains to report on recent fighting against Al-Shabab in which several Al-Shabab fighters had allegedly been killed. According to one of the reporters: “The authorities wanted to show the media how they defeated Al-Shabab.[180]” On the convoys return trip it was ambushed, but the journalists survived.