Summary

At midday on October 26, 2015, some two dozen men viciously assaulted two opposition parliamentarians as they left Cambodia’s National Assembly following an anti-opposition demonstration outside the building. Kung Sophea and Nhay Chamraoen of the Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP) were dragged from their cars and beaten, kicked, and stomped on.

The injuries to Sophea and Chamraoen were extensive. Sophea suffered a broken nose and welts and bruises to his head. Repeated kicks to the back resulted in severe lower-back pain. He suffered a sprained finger and a bruised shin. His right eardrum was torn, requiring an operation. Chamraoen suffered three fractures in his right wrist and underwent a five-hour operation on his eye socket, as a broken bone below the eye was pushing up into the socket, endangering the eye. He also had a broken nose, a broken front tooth, a bruised left wrist, and significant chest pain.

Shortly after the October 26, 2015 attack, Kung Sophea told Human Rights Watch what happened when he left the National Assembly compound:

I see a man standing in front of our car with a walkie-talkie in his hand. Our driver stops to avoid hitting him. A group of about 20-30 men surround the car and a man with a red hat from across the street opens my door and pulls me out of the car with the help of two other men.

I remember one of them saying as they’re punching me inside the car and pulling me out, “So you think you’re strong, huh?” I manage to break away and get back into the car, but sho"rtl"y after I’m dragged out again and punched and kicked. I start to feel dizzy and don’t remember the exact details after this but I remember getting pulled out of my car three separate times. The last time they came into my car they tore my pants and ripped my pocket to get my wallet.

Nhay Chamraoen recalled:

Once I exited through the side gate, we made a right and I see Sophea being attacked by men while he was inside his car. They were about 10 meters away. I remember seeing two police officers about 5 meters away just standing there not doing anything to stop the attack.

My fiancé, who was driving, tried to pull our car back but we were blocked by other cars trying to leave from the same exit behind us. Soon, at least 10 people were surrounding my car holding objects in their hand that I couldn’t identify. I remember them yelling, “Open the door! Open the door! ... That one too!” while pointing at me. One man had a walkie-talkie and used it to smash my window and open my door and drag me out. My fiancé was hit in the back of the head and was terrified but they left her alone in the car.

I fell to the ground and I just remembered a flurry of punches and kicks and tried to cover myself up the best I could but I could not stop the attacks. I lost consciousness. I saw in the video posted [later on social media] that someone was stomping on my chest but I did not remember that happening.

In the ensuing days there was a strong reaction among Cambodians to the brutal and widely publicized attack. In addition, the United States,[1] the European Union,[2] and the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights[3] issued statements condemning the attacks or expressing concern and calling for the perpetrators to be held accountable.

A week after the event, three so-called “hands-on perpetrators” videoed at the scene—Sot Vanny, Chay Sarit, and Mao Hoeun—“confessed” to the attack and were detained pending trial, a move that seemed designed to cover-up, rather than uncover, ultimate responsibility for the crime.

From start to finish, the October 26 assault had all the hallmarks of an operation carried out by Cambodian state security forces. The previous day in Paris, Hun Sen, head of the ruling Cambodian People’s Party (CPP), had reacted to protests against his visit there by publicly threatening to retaliate against the CNRP. The security forces had facilitated the demonstration against the CNRP outside the National Assembly in marked contrast to other occasions in which the police acted aggressively and at times violently to deter or break up peaceful demonstrations organized by the CNRP, trade unions, land activists, and other civil society groups. Further, witnesses implicated members of Hun Sen’s personal Bodyguard Headquarters (BHQ) in civilian clothes as core participants in the demonstration. Finally, contrary to initial government and army denials and dissembling, in late 2015, secret official documents identified the three detained men as BHQ personnel, which the three confirmed at their trial, though they maintained they had not acted on orders from superiors, but because of individual personal anger.

On November 2, the Cambodian government reported that three “military” personnel of the Royal Cambodian Armed Forces (RCAF), Sot Vanny, Mao Hoeun, and Chay Sarit, had voluntarily surrendered to authorities following a public appeal by Prime Minister Hun Sen for the attackers to turn themselves in. The three are clearly identifiable in widely disseminated videos as among a larger group of assailants.

The government said that once in custody the three voluntarily “confessed” that they alone committed the assault against the two CNRP parliamentarians. According to official accounts of their statements, the three said they acted solely out of personal anger that they allege arose from the two CNRP politicians having accused them of being “puppets” of Vietnam.

With the government under intense domestic and international scrutiny not to allow impunity for such a brazen attack, the three were put on trial on April 28, 2016 for aggravated intentional violence and aggravated intentional damage to one of the CNRP parliamentarian’s car, offenses which together carry punishment of up to ten years in prison.

On April 28 and at a further hearing on May 10, the three publicly confessed to carrying out the attack. However, they refused to answer questions about the BHQ chain of command. Their presentation seemed aimed at protecting others who may have ordered or participated in planning and carrying out the attacks. Judges in the CPP-controlled courts blocked questions about whether they had received orders to participate in the attack. The court announced it would pronounce judgment on May 27.

Security forces acting in the name of Hun Sen and the CPP have been responsible for decades of harassment, threats, arbitrary arrests, prosecutions, and physical attacks against political opponents, civil society activists, and anyone deemed critical of the ruling party. However, the October 26 attack on the two opposition members of parliament outside the National Assembly was brazen even by the standards of Hun Sen’s Cambodia. For this reason, Human Rights Watch sought to conduct substantial research not only into the attack itself, but into the alleged source of the attack.

Human Rights Watch interviewed the victims of the attack while they recuperated from their injuries in Thailand and obtained information from witnesses to the demonstration and attack and from military personnel and civilians knowledgeable about Hun Sen’s bodyguard unit. Human Rights Watch and other human rights investigators also examined unpublished and official documents; media reports in Khmer, English, and other languages; photographs and videos, including of the demonstration and attack taken by human rights monitors or posted to Facebook and other Internet sources; and voter registration data indicating where BHQ personnel reside.

We uncovered relevant information on Hun Sen’s bodyguard forces, including their origins, development, and their current deployment, organization, and chain of command, which ends with the prime minister. The bodyguard unit has long been notorious for serious human rights violations, including the March 30, 1997 grenade attack on a rally led by opposition leader Sam Rainsy that killed at least 16 people and injured more than 150. Though the US Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) concluded that the bodyguard unit was involved in the attack, the Cambodian government has never pursued a genuine investigation and the perpetrators have never been brought to justice.

The report also describes the connections between the bodyguard forces and social groups that spearheaded anti-CNRP demonstrations on October 26 in Phnom Penh and elsewhere in the country. These include a pro-CPP youth organization known at the time of the attack as Senaneak, and regular army troops ordered to conduct such gatherings armed and in uniform.

Several senior Cambodian military officers speaking confidentially asserted that within government circles it is widely believed that the prosecution and trial of Sot Vanny, Mao Houen, and Chay Sarit alone is intended to put to rest suspicions of involvement of “the higher levels” of government in the attack.[4] The trial of the three has ignored evidence that many others were directly involved in the attack. It has failed to hold accountable those who planned and organized the attack, possibly including high-ranking political and military figures.

Human Rights Watch reiterates its call for a full and independent investigation of the October 26 attack, that such a legal inquiry be supported by the United Nations and free of government interference, and should ensure the fair prosecution before Cambodian courts of all those responsible for the attack regardless of position or rank.

Recommendations

To the Royal Government of Cambodia:

- Conduct further prompt, impartial, and thorough investigations into the possible responsibility of BHQ officers and personnel, other military and government officials in the RCAF chain of command, and leaders and members of Senaneak and other youth organizations who may bear responsibility for the October 26, 2015 attack on Kung Sophea and Nhay Chamraoen.

- Ensure appropriate prosecutions of those found to be involved in planning, organizing, carrying out, authorizing, or obstructing investigations into the October 26 attack, regardless of rank or position.

- Create through a transparent process an independent commission to conduct a prompt and thorough investigation into and make recommendations to the judicial system for prosecution.

- Appoint to the independent commission respected former members of law enforcement bodies, retired judges, and members of Cambodia’s human rights community, and ensure that the commission is free from the influence of all political parties, security force chains of command, and government bodies.

- Request assistance from the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) and other international support, and fully cooperate with OHCHR and others to help ensure the independence, impartiality, and credibility of this further investigation.

- Ensure the commission has full access to all relevant official documents, the power to subpoena documents and compel witnesses to appear and give testimony, effective means to provide witness protection as necessary, and the authority to make public statements during and after its inquiries, including in response to any official reactions to its work.

- Empower the commission to publicly recommend the suspension, removal, discipline, and/or criminal prosecution of anyone it identifies as reasonably suspected of taking part in or bearing responsibility for the attack.

- Ensure further trials are conducted independently and impartially in accordance with international fair trial standards.

- Dismiss anyone convicted of a crime from the security forces and any official positions.

To Cambodia’s International Donors:

- Publicly call for and actively support the above recommendations.

- Press for genuine reform of Cambodia’s security forces, including bodyguard units, to de-politicize and professionalize them, including by effectively banning security force commanders from holding official or unofficial positions of leadership in political parties and from giving or taking orders that are intended to serve the interests of any particular individual or political party.

- Strengthen efforts to press for the creation of a professional and independent judiciary and prosecution service, including the government’s adoption of the measures necessary to reform or replace the current politicized Supreme Council of the Magistracy. End the Ministry of Justice’s de facto supervisory role of the judiciary.

- Make it clear to the government that, after more than two decades since the signing of the 1991 Paris Peace Agreements and adoption of the 1993 Constitution of the Kingdom of Cambodia, reforms to professionalize and free the military, police, judiciary, and other state institutions from CPP domination are essential, or international assistance to Cambodia will be reassessed.

I. Hun Sen’s Bodyguard Headquarters and Commanders

Article 2 of the Law on the Organization and Functioning of the Council of Ministers of July 20, 1994 specifies that the Royal Government of Cambodia “governs, commands, and utilizes the military, police, and other armed forces and the administration of their conduct of activities.”[5] The BHQ originated from army Regiment 70, founded in the 1980s[6] and re-designated Brigade 70 in 1994.[7] Both then-First Prime Minister Prince Norodom Ranariddh and Second Prime Minister Hun Sen were empowered to use Brigade 70 to prevent and suppress acts they considered to be adverse to Cambodia’s “political stability, security, and order,”[8] including by commanding it to take “pre-emptive measures.”[9]

Within Brigade 70, Battalion 2 was established in 1994 as a close protection unit for Hun Sen under his personal command. Battalion 2 evolved primarily out of former Battalion 246,[10] a unit set up under the Vietnamese military and Hun Sen command in Vietnam on June 24, 1978.[11]

Battalion 2, which was soon expanded to regimental strength,[12] incorporated elements of Battalion 246, a designation that has continued to exist for one of today’s many reorganized BHQ “intervention units,” the tasks of which include countering demonstrations.

The BHQ also includes a headquarters for the Special Counter-Terrorism Forces,[13] commanded by Hun Sen’s eldest son, the US military academy-trained Lt. Gen. Hun Manet.[14] The BHQ has been undergoing periodic expansion, for example adding 350 new recruits starting in late 2014.[15]

As prime minister, Hun Sen is in “direct command” of all RCAF and police.[16] This authority includes command of BHQ forces, previously also known as the Prime Ministers’ Bodyguard Unit (PMBU), which were formally made a standalone part of the RCAF on September 4, 2009.[17]

In addition to providing close protection to Hun Sen, his family, and high-ranking officials as designated by the prime minister, the BHQ is assigned under his instructions to coordinate with other armed forces, police, and the gendarmerie in the prevention and suppression of demonstrations “adversely affecting political stability and the security of and order in society” and of insurrections.[18] One commentator has described the bodyguard unit as a personal army of Hun Sen.[19]

BHQ Bases

Battalion 2’s original headquarters was just south of Hun Sen’s personal residence in the Tuol Krasang area in what is now the southernmost part of Ta Khmao city, the chief town of Kandal province.[20] Tuol Krasang is now the BHQ main base. Unit 246’s original headquarters was east of Tuol Krasang in the Svay Rolum area on what is now the boundary between Ta Khmao city and S’ang district of Kandal province. Still sometimes known as “Barracks 246” and also as Pong Loeung, the Svay Rolum BHQ location is now the unit’s second most important base. The third major BHQ base is in Phnom Penh,[21] on Street 264 just behind the prime minister’s former main residential compound in the capital,[22] now the residence of his daughter Hun Mana,[23] just northeast of the Independence Monument.

The BHQ also has a “light command” base in Preah Vihear province in RCAF Military Region 4.[24] This is a legacy of tension and clashes with Thai armed forces along the border between Preah Vihear and Thailand. Beginning in 2008, Hun Sen ordered a considerable number of bodyguard forces to the frontier, where they engaged in some fighting. Although much of the contingent has since been withdrawn, there is a residual BHQ presence.[25]

BHQ Commander Gen. Hing Bunhieng

The current BHQ commander is Gen. Hing Bunhieng, a Battalion 246 veteran[26] who was originally a deputy commander of Battalion 2[27] and Brigade 70.[28] Today, Hing Bunhieng has also become a deputy supreme commander of the RCAF and deputy chief of Hun Sen’s Personal Cabinet. [29] He is also a vice-chairperson of the CPP Standing Committee for party-strengthening in Kandal province,[30] with particular responsibility for Kandal Steung district.[31] He was elevated to the CPP Central Committee in February 2015.[32]

Hing Bunhieng was openly partisan in favor of the CPP and Hun Sen and against the CNRP during the campaign[33] during the 2013 national elections.[34] When the CNRP challenged the election results, gendarme and police forces sometimes violently suppressed protests, on occasion with unnecessary lethal force.[35] He has continued to be politically partisan since the elections,[36] denouncing the CNRP[37] while praising the CPP and Hun Sen.[38]

Hing Bunhieng was identified by the US FBI as reporting directly to Hun Sen when the bodyguard unit was deployed to participate in the March 30, 1997 grenade attack on Sam Rainsy.[39]

BHQ Deputy Commander Lt. Gen. Dieng Sarun

In recent years, Lt. Gen. Dieng Sarun has emerged as a principal deputy BHQ commander,[40] having held a deputy bodyguard unit commander post since at least April 1997.[41] Starting in August 1997, Dieng Sarun was an assistant to Kun Kim,[42] then the deputy governor of Kandal province.

In that capacity, Kun Kim was instrumental in helping Hun Sen to establish both a personal residence and his expanding bodyguard force facilities in and around the Tuol Krasang area of the province.[43] From this time, he became politically known as “Hun Sen’s hatchet man”[44] and began to exert considerable sway over key RCAF units in and around Phnom Penh, especially Brigade 70 and Hun Sen’s bodyguards.[45] Following the fundamentally flawed national elections of July 26, 1998, Kun Kim orchestrated CPP-led mob violence to help police, gendarme, and army forces break up protests in Phnom Penh by the opposition, its supporters, and other members of the city’s population against what they alleged was CPP-organized election fraud.[46] Efforts to suppress protests by security forces and mob members killed at least 21 people.[47]

Since 2009, Kun Kim, now a full general, has become chief of the RCAF Mixed General Staff[48] and a member of the Permanent Committee of the CPP Central Committee.[49] At the same time as exercising command authority over RCAF nation-wide,[50] Kun Kim has developed particularly strong connections to Military Region 4, in parts of which he is in charge of CPP affairs, notably Oddar Meanchey province, since at least 2013.[51]

Dieng Sarun continues to function as Kun Kim’s personal representative.[52] He is concurrently one of Kun Kim’s deputy chiefs at the RCAF Mixed General Staff[53] and a deputy commander of the army, called RCAF “Land Forces.”[54] He is also officially a “personal advisor” to Hun Sen.[55] Like his BHQ superior Gen. Hing Bunhieng and two fellow principal deputy BHQ commanders, Dieng Sarun was brought into the CPP Central Committee in February 2015.[56]

During the run-up to the July 2013 election, Dieng Sarun openly conducted politically partisan CPP grassroots-strengthening activities in Kandal province as vice chairperson of the CPP Work Group for Ta Khmao city,[57] a political proselytizing function he has continued to perform.[58]

Since the elections, he has spoken publicly about the Bodyguard Unit’s duty to maintain what he called “political stability for” Hun Sen.[59] In a May 2015 speech commemorating the deaths of those who were killed while Pol Pot’s Communist Party of Kampuchea was in power from 1975 to 1979, Dieng Sarun equated CNRP supporters’ calls for “change” via the ballot box with an intent to commit Pol Pot-style “auto-genocide” against the Cambodian people.[60]

Dieng Sarun operates mainly out of the Svay Rolum BHQ base, where he is the senior officer in charge.[61] Among various other functions, it is a venue for specialized training of BHQ forces, including “techniques of all calibres and tactics against demonstrators,” such as hand-to-hand combat, and use of motorcycle-borne contingents, training over which Dieng Sarun has presided in the presence of Gen. Hing Bunhieng.[62]

Youth Federation of Senaneak (“Legion of Cobras”)

The Senaneak (“Legion of Cobras”) Youth Federation was created as one of a variety of youth organizations promoted and coordinated by the youth branch of a recently-established CPP Mass Mobilization Committee.[63] At the end of March 2016, the Senaneak was renamed the Federation of Peace-Loving Youth.[64]

In addition to his military functions and his activities on behalf of the CPP, Lt. Gen. Dieng Sarun was, according to postings on his Facebook page, the “founder”[65] and the original “Honorary Chairperson”[66] of Senaneak, functioning at the time of the October 26 events as its “leader,” “sponsor,”[67] and “organizer,”[68] providing it with funds,[69] and giving it orders.[70]

Senaneak’s founding “operational chairperson” was Pankhem Bunthan, an advisor to Hun Sen.[71] Several of Dieng Sarun’s children, including his son Dieng Saran and daughters Dieng Sophanna and Dieng Sophany, prominently displayed their involvement in its activities with Dieng Saran as one Senaneak operational vice chairperson[72] and having Om Rachany as another.[73] She is the daughter of Om Yentieng,one of Hun Sen’s closest political advisors and allies,[74] a CPP Central Committee member who as head of the government’s highly politicized Anti-Corruption Unit has recently led a campaign of arrests of human rights defenders.[75]

Both Pankheunthan and Dieng Saran are CPP members.[76]

Senaneak began activities in January 2015, proclaiming itself politically as an organization that supports the CPP, Hun Sen as prime minister, and his government.It describes its objectives as primarily humanitarian, focused on the distribution of largesse and other relief marked with the CPP logo to Cambodia’s poor and otherwise disadvantaged.[77] It presents itself as modelled upon, acting as the “younger brothers and sisters” of, and working in cooperation with[78] the Cambodian Red Cross, whose long-time chairperson is Hun Sen’s wife, Bun Rany; the Union of Youth Federations of Cambodia, the de facto CPP youth organization, whose chairperson is Hun Sen’s youngest son, Hun Many, a national assembly member[79]; and the Group 157 Youth Movement,founded by Hun Sen’s eldest son, Lt. Gen. Hun Manet.[80]

At the same time, as explained by Dieng Sarun in a Senaneak video clip, this organization’s members operated as civilian “bodyguards of Samdech Techo Hun Sen” and its original symbol was a seven-headed cobra virtually identical to the BHQ unit insignia.[81] The Dieng Sarun clip depicts a Senaneak visit at the end of July 2015 to Dieng Sarun’s BHQ base at Svay Rolum base at which Dieng Sarun speaks of the “solidarity” between Senaneak and the BHQ in “carrying out the duty of protecting Hun Sen.”[82] According to Senaneak’s Facebook page, the purpose of the visit was to “join together the forces of the Senaneak Youth Federation and the BHQ in solidarity with a single will for the objective” of keeping Hun Sen in power “forever.”[83] A delegation of the organization later visited BHQ forward combat positions in Preah Vihear province on the Cambodia-Thailand border as guests of Gen. Hing Bunhieng.[84]

The earliest Senaneak postings on Facebook seem to date from April 2015, when it held public gatherings among civilian residents of Svay Rolum.[85] It thereafter began setting up chapters in other provinces and within government ministries.[86]

Senaneak’s first big splash on the Phnom Penh political stage was on June 21, 2015, when it challenged a CNRP supporter to appear and challenge it at an oath-swearing event on the Phnom Penh waterfront. Senaneak had mobilized many of its members, headed by Pankhem Bunthan, Dieng Saran, and Om Rachany, to support Hun Sen in declaring that Cambodia’s July 2013 national elections had been free and fair. They swore their allegiance to Hun Sen, his government, and the CPP. The CNRP supporter decided not to attend the event.[87]

Hun Sen’s Authority and Instructions

On February 26, 2015, Hun Sen reinforced his control over the BHQ and its pre-eminence over other RCAF units by creating a new leadership body with directive or deputized police powers for his security called the “Mixed Task Force to Arrange for Security and Safety.” This includes RCAF officers Hing Bunhieng and other senior BHQ officers, Hun Manet, and senior officers from the Gendarmerie, Ministry of Interior, and National Police.[88] This was in line with the long-standing CPP organizational doctrine of creating unified command committees deploying mixed military and police forces ultimately answering to a single party political chief,[89] in this case, Hun Sen himself.

Hun Sen’s personalized command authority over all RCAF forces, including the BHQ, was further asserted at a gathering that he convened at Tuol Krasang on July 23, 2015. The meeting was attended by almost 5,000 senior army, BHQ, gendarme, navy, air force, and police officers from all over Cambodia. According to CPP-friendly media, they comprised the leadership of the country’s 180,000 security forces.[90] On this occasion, Hun Sen defined in six points the “duties of the armed forces,” including in national defense and domestic political security. With regard to the latter, he issued an “absolute order” that the armed forces must “ensure there will be no color revolution” in Cambodia—a reference to the political uprisings that had taken place in former Soviet countries in the early 2000s, most notably the “Orange Revolution” in Ukraine—and that they must do so by “eliminating acts by any group or party” deemed “illegal.”[91]

CPP-friendly media reported that what Hun Sen meant by a “color revolution” was what the prime minister claimed was a plot by the CNRP to incite mass protests to overthrow him.[92] According to several senior RCAF officers speaking on a basis of confidentiality, Hun Sen and his top security force commanders deemed non-violent demonstrations by the CNRP demanding greater freedom of expression, popular outpourings of public support for CNRP actions raising questions about the delimitation and demarcation of the Cambodia-Vietnam border, and public gatherings and other peaceful activities organized by nongovernmental and community-based organizations all to be part of this so-called “color-revolution” conspiracy. According to these sources, Hun Sen set a deadline of late October 2015 for the CNRP to cease such plotting, saying that unless it did, suppressive action against it would have to be taken.[93]

The events of October 26, 2015 have proved to be the first in a series of such actions. The most recent of these was the mobilization of anti-demonstration, crime-suppression, counter-terrorism, traffic, and para-police under the on-the-spot leadership of deputy Phnom Penh governor Khuon Sreng to stop protests on May 9, 2016 against the detention for prosecution of five human rights defenders arrested by Om Yentieng’s Anti-Corruption Unit. During this May 9 mixed force operation, eight human rights defenders, including two international observers, were temporarily held in police custody and questioned about their possible involvement in a “color revolution.”[94]

Meanwhile, Gen. Tea Banh, a CPP Permanent Committee member, deputy Prime Minister, and Minister of National Defense, had publicly proclaimed in a speech on July 28, 2015 that alleged opposition plotting had made him “very angry,”[95] and that it was necessary to “control democracy” in Cambodia to prevent “anarchy.”[96] During August 2015, RCAF Supreme Commander Gen. Pol Saroeun and other RCAF commanders declared that the opposition to Hun Sen was comprised of “dishonest and unprincipled persons” who “are always making things up, distorting them, and using demagoguery with the evil intent of toppling the Royal Government.”[97]

According to several senior RCAF officers, to prevent this feared outcome, Hun Sen gave orders to his forces to deter non-violent CNRP and civil society opposition, questioning of, and protests against CPP policies and practices.[98] However, his opponents and critics, including among Cambodian communities outside the country, continued to be politically and socially vocal from August through October,even as the unannounced deadline for a crackdown approached.

II. The October 26 Attack

In late October, according to internal government sources, Hun Sen secretly decided to take action against the CNRP by removing its deputy leader, Kem Sokha, as first vice-chairperson of the National Assembly.[99] This decision followed a series of public statements by the prime minister since August 2015 expressing his anger at CNRP’s continued opposition to CPP rule,[100] accusing it of “traitorous behaviour,[101] saying it was no different from Pol Pot’s Khmer Rouge,[102] recalling its alleged previous pursuit of a “color revolution” strategy,[103] talking of a “funeral day” for Kem Sokha if he tried to drive the prime minister from office,[104] and predicting war if the CPP lost an election.[105]

On October 25, Cambodians in Paris demonstrated against the prime minister while he was on an official visit to France.[106] In a speech later that day, he blamed the demonstrations on the CNRP[107] and warned that “if someone comes back at you tomorrow in Phnom Penh with the same game, don’t be angry.”[108] He said, “Tomorrow there will be a demonstration in Phnom Penh against the opposition party and to demand the removal” of Kem Sokha from his National Assembly leadership post,[109] an action coinciding with a session of the National Assembly scheduled to take place in the prime minister’s absence. He declared that such a counter-demonstration in Phnom Penh would be an exercise of the same right to freedom of assembly as that CNRP was always claiming.[110] Later, Hun Sen said that this October 26 protest was also in response to a September 2015 demonstration by Cambodians against him in New York City while he was attending the United Nations General Assembly there.[111]

Hun Sen did not mention that government security forces had routinely prevented would-be peaceful protesters from gathering to demonstrate in front of parliament,[112] where the CPP protest against Kem Sokha would take place.

Kun Kim, exercising his authority as chief of the RCAF Mixed General Staff, as a CPP Standing Committee Member in direct political charge of party affairs and civilian administration in parts of Military Region 4, and as vice chairperson of the RCAF Unified Command Committee for the Cambodia-Thailand Border Battlefield, issued a petition from Preah Vihear temple in the name of its officers and men demanding Kem Sokha be removed as assembly vice chairperson.[113]

Anti-Kem Sokha gatherings were organized within Kun Kim’s particular area of political authority, such as in Kok Man commune of Banteay Ampil district in Oddar Meanchey province on the afternoon of October 26. Both heavily armed soldiers in uniform, including from RCAF Intervention Division 2, and people dressed in civilian clothes, demonstrated against Kem Sokha. Some protesters also called for the expulsion of CNRP President Sam Rainsy from the National Assembly.[114]

The anti-Kem Sokha demonstrations in Phnom Penh were supported by the deputy governor of Kandal, Kim Reuthy,[115] the son of Gen. Kun Kim, on his Facebook page. That morning, Kim Reuthy called on people to join the demonstration, posting notes with the anti-Kem Sokha slogans carried by Senaneak and other participants. As the day progressed, Kim Reuthy praised the CPP as the “savior” of Cambodia and declared himself in favor of the RCAF acting to “put an end” to Kem Sokha’s tenure as National Assembly first vice chairperson.[116]

A substantively identical petition was also issued from Preah Vihear on October 26 by Lt. Gen. Srey Doek on behalf of RCAF Military Region 4 and in the name of army and gendarme forces stationed on the border. Srey Doek is a CPP Central Committee member, commander of RCAF Intervention Division 3, and chairperson of the Direction 1 Command of the RCAF Unified Command Committee for the Cambodia-Thailand Border Battlefield.[117] Demonstrations followed that included massed troops of RCAF regional Brigade 41 stationed in Anlung Veng district of Oddar Meanchey province[118] and regional Brigade 42, also stationed in Oddar Meanchey.[119]

Defense Minister Tea Banh later endorsed what he described as the armed forces’ right to carry out such ove"rtl"y partisan, anti-opposition party political actions.[120]

It was in this context that, on the morning of October 26, participants in the demonstration against Kem Sokha gathered at the Tuol Krasang and Svay Rolum BHQ bases and in Phnom Penh itself, where the authorities had in the past routinely used security forces to break-up peaceful opposition protests and arrest protesters.[121] According to reports broadcast by Radio Free Asia, those at Tuol Krasang and Svay Rolum included almost 200 BHQ personnel in civilian clothes organized by the BHQ itself and hundreds of villagers, members of village-level “People’s Defense” para-police, and members of Hun Many’s CPP-affiliated youth organization mobilized by local CPP governing authorities.[122]

In at least some instances, villagers claim they were simply told they would be attending an unspecified rally, for which they would be paid and provided with food, a common practice of the CPP. The organizers transported them in trucks to the National Assembly, which is in south central Phnom Penh.[123] According to one of the drivers, only commanders among the civilian-clothed BHQ passengers carried walkie-talkies.[124]

A photograph (on the following page) taken that morning just inside the Svay Rolum base shows a man identified in social media as the same person clearly visible in videos posted on the Internet as participating in the attack on the CNRP parliamentarians and who was later named as Sot Vanny. He appears in the photograph as present in Svay Rolum with a truckload of people.[125] This photograph reportedly appeared in social media because BHQ insiders had leaked it. [126]

Those who gathered in Phnom Penh did so under the leadership of Senaneak members from the capital and the provinces, who were given instructions about participation via Facebook.[127] This group also went to the National Assembly.

According to Khmer-language media, government security forces were under instructions to “protect and facilitate” their participation in the demonstration, during which they were welcomed and given words of support by CPP parliamentarians, including Hun Many.[128]

Hun Sen family-owned media identified the prime minister’s advisor and Senaneak Operational Chairperson Pankhem Bunthan as the “leader” and “representative” of all the demonstrators.[129]

People at the scene identified BHQ Deputy Commander Lt. Gen. Dieng Sarun at the demonstration, dressed in civilian clothes.[130] Photographs of the demonstration show his son and Senaneak Operational Vice Chairpersons Dieng Saran and Om Rachany alongside Pankhem Bunthan together with other top Senaneak figures. Photographs also show that those at the front of the Senaneak contingent included two people later identified as current or former BHQ members linked to its Svay Rolum base, Mao Hoeun and Chay Sarit.

In the photograph to the right, Mao Hoeun is visible (last to the right) holding an anti-Kem Sokha banner together with Senaneak leaders. In the photograph below, Chay Sarit (mid-left, in red cap) is seen raising his fist in support of anti-Kem Sokha slogans.

In addition, Mao Hoeun appears in a video at the beginning of the anti-Kem Sokha demonstration, standing among demonstrators listening to an anti-Kem Sokha speech by a demonstrator whose remarks were being prompted by Pankhem Bunthan.[131] Facebook photographs of two members of Hun Many’s youth organization in the organization’s uniform with military personnel on another occasion match with Facebook photographs of them in the midst of the October 26 demonstration, but wearing ordinary street clothes.

Having learned about the demonstration against him, Kem Sokha did not attend the National Assembly session and also stayed away from his residence.[132] The scheduled parliamentary session went ahead inside the National Assembly while the demonstration proceeded outside its front entrance, along the west side of the assembly compound. In contrast to other occasions on which security forces prevented, sometimes violently, opposition and civil society groups from demonstrating in front the parliament, they allowed this anti-opposition protest to go forward completely unhindered,[133] while providing porous security perimeters to the north and the south.[134]

The Phnom Penh municipality spokesperson said that although City Hall was not officially notified in advance of the gathering, demonstration leaders informed the Phnom Penh authorities as it began that it would end at 10:30 a.m.[135] Pro-CPP media put the crowd at more than 2,000 to 3,000 people, describing the demonstration as having been organized in advance.[136] Unaffiliated media estimated the crowd at the lower figure.[137]

At 11:32 a.m., Hun Sen family-owned media reported that the demonstrators were dispersing.[138] Most of the few government security forces that had been in the area withdrew, leaving an even smaller number, mostly traffic police, standing around.[139]

Several hundred demonstrators relocated to Kem Sokha’s residence,[140] some seven kilometers from the National Assembly, on the northeast side of Phnom Penh, where they gathered without interference from security forces sho"rtl"y before noon.[141] A considerable number travelled by motorcycle.[142] Many of these were a red Suzuki model with false license plates,[143] copies of a type of plate that was only issued before these motorcycles were manufactured. According to people living around the Svay Rolum base, BHQ uses these motorcycles with such plates when on missions outside the BHQ barracks’ motor pools,[144] where they are ordinarily parked with other BHQ vehicles, including BHQ armored vehicles.

No government security forces appeared to protect the Kem Sokha residence.[145] With his wife inside and phoning for help to no avail, demonstrators hurled rocks and bottles at and into the compound.[146]

Meanwhile, after parliamentary business ended around noon, two CNRP parliamentarians, Kung Sophea and Nhay Chamraoen, tried to leave the assembly compound through a main exit on the northwest side of the building. However, this exit was closed, and a guard pointed them to a south-side exit. They went there to depart in their cars, which came to pick them up. They reportedly left sometime between 12:20 p.m.[147] and 12:30 p.m.,[148] with Kung Sophea in the first vehicle and Nhay Chamraoen following in the second.[149] About a hundred demonstrators remained in the area.

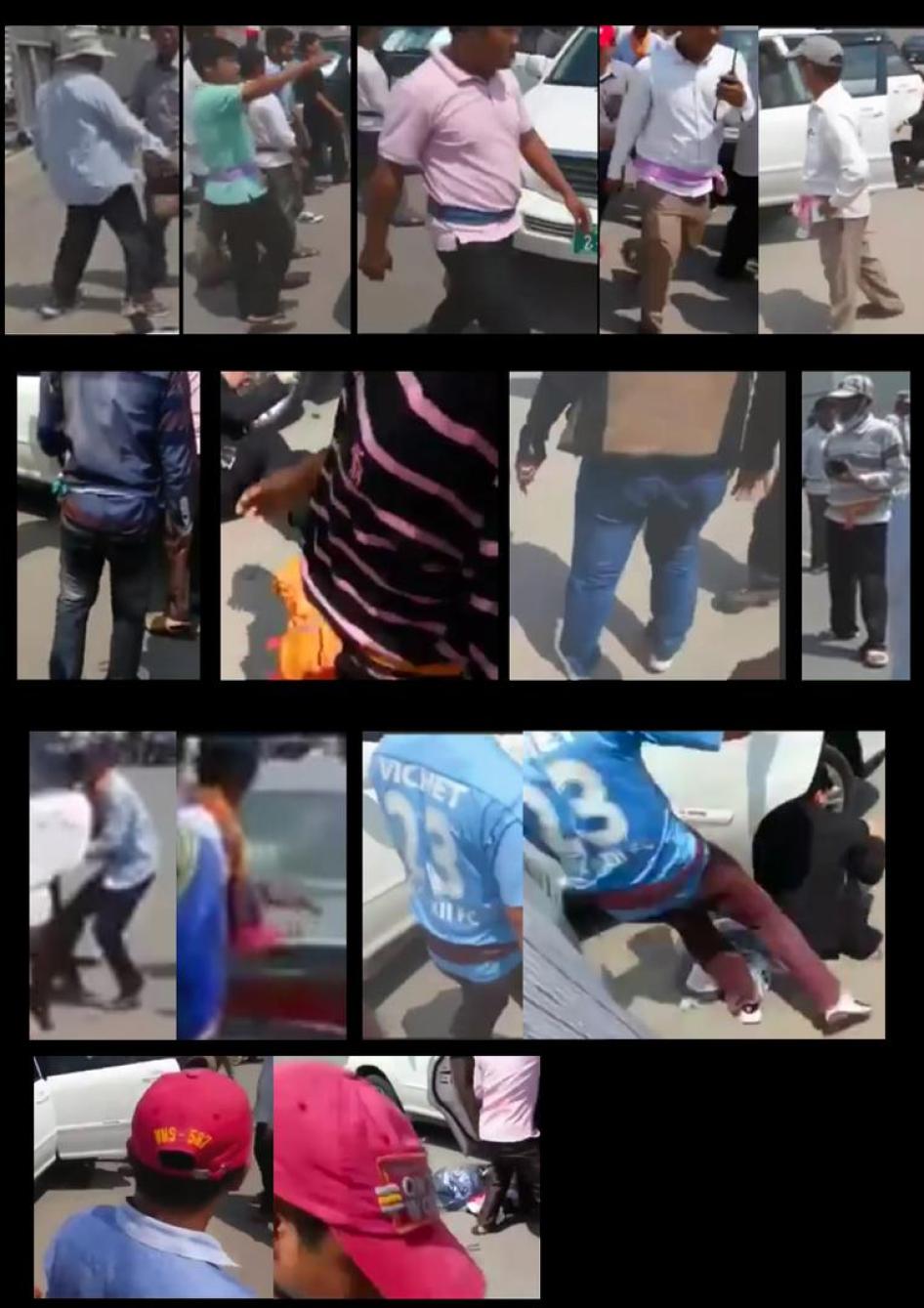

According to a report posted by a usually pro-CPP news website a little more than an hour after the incident, demonstrators from this group first attacked Kung Sophea and then Nhay Chamraoen,. This report specifies that Kung Sophea was in a vehicle with license plate number 114 and Nhay Chamroaen in a vehicle with license plate number 038.[150] Two available videos of the attack show the assailants dragging the two men from their cars, and then punching, kicking, and stomping on them.[151]

A video[152] shot from ground level and with a soundtrack shows Kung Sophea being dragged out of the back seat of a white four-door hatchback with license plate number 114 and assaulted on the ground with kicks and stomps. He can be seen getting back in the car, but is then again dragged out and assaulted in the same manner. Chay Sarit is visible in this scene kicking Sophea and holding a walkie-talkie. After Kung Sophea is put back in the car by his driver, Sarit and the other men are seen walking away to the south towards other vehicles, including a black one that seems to be parked.

A silent video shot from an above angle[153] shows Sot Vanny approaching what appears to be the open window of the front passenger side of a seemingly stationary black four-seater pick-up truck in which Nhay Chamraoen is sitting, then dragging Chamraoen from the vehicle and turning him over to a group of men who assault him. Mao Hoeun is visible standing behind the assailants. After Nhay Chamraoen is thrown to the ground, kicked and stomped, Sot Vanny and the other men walk casually away from the scene, headed west out of the area south of the National Assembly. The first video contains a scene of Nhay Chamroaen being stomped by Mao Hoeun as he lies on the ground.

The handful of traffic police and other policemen in the vicinity took no evident steps to intervene.[154] One video shows direct assailants and others in the immediate area casually walking away after the attack.[155]

Kung Sophea told the media some 20 men were present when he was beaten, while Nhay Chamraoen estimated that 10 men took part in his beating.[156] The video evidence puts at least 20 people in the immediate area,[157] and contains images of 10 people who were directly involved in inflicting physical abuse.[158] Of these, five can be seen in photographs or videos of the earlier demonstration in front of the National Assembly.[159]

The injuries to Sophea and Chamraoen were extensive. Sophea suffered a broken nose and welts and bruises to his head. Repeated kicks to the back resulted in severe lower-back pain. He suffered a sprained finger and a bruised shin. His right eardrum was torn, requiring an operation. Chamraoen suffered three fractures in his right wrist. He underwent a five-hour operation on his eye socket, as a broken bone below the eye was pushing up into the socket, endangering the eye. He also had a broken nose, a broken front tooth, a bruised left wrist, and significant chest pain.[160]

Immediately after the attack, Kung Sophea and Nhay Chamraoen told the media that they had not interacted verbally with those who attacked them and had done nothing to provoke them.[161] The available video described below, while fragmentary, provides no evidence to the contrary.

People who said they were demonstrators at the National Assembly were quoted in the media saying that after the assault, BHQ and civilian demonstrators, including those directly involved in beating Kung Sophea and Nhay Chamraoen, were trucked back to a hotel in Ta Khmao that is near the BHQ base. The assailants entered while the others remained outside and then dispersed.[162] A driver of one of the vehicles later said one of BHQ commanders in his vehicle bragged about having participated hands-on in a beating.[163]

III. No Investigation, Much Disinformation

Soon after the attacks on Kung Sophea and Nhay Chamraoen, clear video and photographic images of three October 26 assailants emerged and spread widely on social media. They were later identified as Sot Vanny, Mao Hoeun, and Chay Sarit. The three were taken into custody on November 2, 2015, when they are officially said to have voluntarily surrendered in response to an appeal by Hun Sen[164] and then to have willingly confessed to assaulting the parliamentarians.[165] They have remained in detention ever since, including during the two public trial hearings in the case, on April 28 and May 10, 2016, and while awaiting pronouncement of judgment by the Phnom Penh Court of First Instance, scheduled for May 27, 2016.

[166]No one else has been taken into custody. There have been no reports of any warrants for additional arrests,[168] including for others against whom there is visual evidence of involvement in the beatings in the two videos of the incident, as show in the grabs taken from them, below.

Media reports published once Sot Vanny, Mao Hoeun, and Chay Sarit were in custody and quoting what appear to be court documents described Sot Vanny as 45-years-old and a resident of Prek Reang village of Kampong Samnanh commune of Ta Khmao city; Mao Hoeun as 34-years-old and a resident of Village 3 of Prek Khsay Kha commune in Peam Ror district of Prey Veng province; and Chay Sarit as 33-years-old and a resident of Ta Khmao commune in Ta Khmao city.[169] The media reported that these same court documents stated the three were “military,” without specifying branch or unit.[170]

After Sot Vanny’s detention, reporters seeking to interview members of his family in Prek Reang, a village very close to the BHQ Svay Rolum base, were told that as he was a member of the military and that they needed to get authorization from his commander, named “Run,” based in the nearby Bodyguard compound, which is separate from the main Bodyguard headquarters.[173] “Run” is a shortened name by which Lt. Gen. Dieng Sarun is locally known.[174] In the 2013 national election voter roster, Sot Vanny’s name appears among a list of 340 mostly men of military age listed as registered at House 3A on Street 264.[175] A former BHQ soldier has identified this as a BHQ residence.[176] This house is behind Hun Sen’s former main residence in central Phnom Penh; Hun Sen’s daughter, Hun Mana, is listed as a voter at the address at the house next door at House 4A.[177]

A media report said the second man in custody for the attack, Mao Hoeun, became a bodyguard in Phnom Penh after his wife died in a traffic accident.[178] Ta Khmao residents speaking to the media have identified him as a Hun Sen bodyguard resident at what they called the “Pong Loeung Barracks,” an alternate name for the Svay Rolum BHQ base, saying he was transported from that base to the demonstration on October 26.[179]

As illustrated below and directly to the right, Chay Sarit, the third man tried can be seen in multiple images on his Facebook page in various BHQ and other uniforms. He can also be seen at various BHQ and other military facilities and operations, including one picture of him out of uniform practicing hand-to-hand combat.[180]

People residing near the Svay Rolum base told the media they recognized him, but provided no further details.[181]

On October 30, in the first of a series of public claims by the authorities that the three were not BHQ personnel, the BHQ Personnel and Training Commissariat issued a statement that the Chay Sarit on a photograph appearing in social media “is not on the Bodyguard Headquarters-maintained roster.”[182] However, this and the subsequent denials were given the lie by various secret official documents dated November and December 2015, which specifically identified all three as “BHQ military.”[183]

Immediately after the assaults and during the subsequent week before Sot Vanny, Mao Hoeun, and Chay Sairt were in custody, CPP, government and security force officials provided differing versions of events. Within hours of the attack, a Phnom Penh Municipality spokesperson suggested that the assailants were not demonstrators and were instead acting on account of some personal anger,[184] with one pro-CPP youth group immediately quoting “witnesses” as saying that Kung Sophea and Nhay Chamroaen had provoked the attack by accusing those who set upon them of being “mercenary demonstrators and CPP puppets.”[185] Meanwhile, a police officer said security forces had been unable to protect the victims because security forces had stood down once the demonstration was over.

At the same time, within hours Hun Many condemned the violence and called on the competent government authorities to arrest the “hands-on” (day-dal) assailants and prosecute them according to the law.[186]

Relying on initial accounts from the scene, Human Rights Watch issued a news release dated October 27 that witnesses had recognized BHQ elements in civilian dress acting as core participants in the demonstrations both outside the National Assembly and at Kem Sokha’s residence.[187]

The same day, a government spokesperson said that the violence of October 26 was unconnected to the demonstration, saying that the beatings had occurred “more than an hour” after the end of what had been a non-violent gathering.[188] The government declared it had ordered the Ministry of Interior to find and arrest the “hands-on” perpetrators.[189] Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Interior Sar Kheng, a CPP vice chairperson, announced the formation of a special commission headed by Ministry of Interior Secretary of State Gen. Em Sam-an, a CPP Central Committee member and a close ally of Hun Sen at the ministry in control of the police and other ministerial security forces,[190] to investigate the assault.[191] Echoing earlier statements, Sar Kheng soon explained that its mandate was to “seek out and arrest the hands-on perpetrators.”[192] The vice chairperson of the commission was a deputy supreme commissioner of the National Police, and its members included the heads of a number of Ministry of Interior directorates and two deputy commissioners of the Phnom Penh police.[193]

Hun Sen returned from France to Cambodia on October 28, as social media amateur sleuthing increasingly focused on the alleged involvement of Sot Vanny, Mao Hoeun, and Chay Sarit in the beatings.[194] At the airport, BHQ Commander Hing Bunhieng responded to allegations that the BHQ was implicated in the demonstrations with a denial combined with a warning to Cambodian reporters asking him about this, that they should “be careful,” affirming that BHQ forces operate under Hun Sen’s direct command.[195] Later in the day, the prime minister affirmed that the violence was committed after the demonstration ended,[196] while reiterating that the “competent authorities” should arrest “hands-on perpetrators.”[197] He advised such perpetrators that “the best thing to do is to come forward and surrender” to the competent authorities and “take responsibility before the law.”[198] Gen. Em Sam-an meanwhile declared that there were only a “small number” of such culprits.[199] On October 30, Deputy Prime Minister and Foreign Minister Hor Namhong briefed diplomats with the official narrative that there was no connection between the demonstration and the assaults.[200]

That same day, the National Assembly sitting with only its CPP majority present stripped Kem Sokha of his vice chairpersonship. The CNRP members of parliament did not attend due to security concerns in light of the October 26 attack.[201]

On November 2, the spokesperson of the National Police indicated that the authorities had completed their preliminary investigation into the incident and the resulting casefile had been presented to the Phnom Penh Municipal Court.[202] Investigation Committee member Maj. Gen. Sok Khemarin, chairperson of the Criminal Police Directorate of the Ministry of Interior,[203] characterized the perpetrators as “opportunists” who acted only after the demonstration was over and whose motivation was “revenge” of some kind.[204] A Ministry of Interior spokesperson then announced that Sot Vanny, Mao Hoeun, and Chay Sarit had presented themselves to the Investigating Commission, saying the commission would be turning them over to court custody,[205] thus ending its own investigation and leaving any further investigative action to be conducted or ordered by the judiciary.[206]

The spokesperson affirmed that the three were those most prominently identified in social media, then said that further arrests were unlikely, because, he asserted, no one else had “directly” participated in the assault, and because the three had not been organized by anyone else to carry it out. Rather, he said, “they were led by themselves,”[207] and thus any official positions they might have were of no significance.[208] Investigation Commission member Sok Khemarin later told journalists that for this reason the commission had therefore not asked the three about their units or ranks.[209] Two months later, after Human Rights Watch published a report identifying the three as members of BHQ[210], Sok Khemarin was pressed by a reporter for clarification, the major general again affirmed that he did not know whether or not they were BHQ personnel, stating, “I am not clear because … I quickly sent them to court and I did not ask them about details.” He went on to say, “I dare not say,” what their unit of military service might be.[211]

Defense Minister Gen. Tea Banh had meanwhile stated that the fact that the three were military men was irrelevant because the assault had nothing to do with the armed forces.[212] Interior Ministry spokesman Gen. Khieu Sopheak had declared that none of the three were members of the BHQ, saying this was accurate because BHQ had said it, without citing any specifics about this claim.[213]

For his part, Pankhem Bunthan said in remarks reported on November 6 that, “It was not my Senaneak youth group leading this protest and turning it into violence. We had only 12 to 15 members there.” He claimed that Senaneak’s “work is non-violent, and we work only for humanitarian causes.”[214] By January 2016, Senaneak had also changed its symbol to one that no longer resembles the BHQ insignia.[215] As mentioned above, in late March 2016, it changed its name to the Federation of Peace-Loving Youth, [216] with yet another logo. [217] Lt. Gen. Dieng Sarun also stepped down as the organization’s “Honorary Chairperson,” being replaced by Chum Kosal,[218] a CPP media personality who is an advisor to Hun Sen.[219]

On November 7, 2015, Hun Many issued a “public clarification” responding to what he said were attempts to “unjustly and baselessly link” him to the violence of October 26 via his connections to those who had demonstrated that day. He warned that he and his youth organization’s “working group” were prepared, “via the competent authorities, to carry out implementation of legal procedures” against persons making such allegations.[220]

“Confessions” of the “Hands-on Perpetrators”

According to the Ministry of Interior spokesperson, speaking the day after the three were taken into custody, they had already “confessed, admitting their wrong-doing.”[221] They were then transferred to court custody on November 4.[222]

After being interviewed in the morning by a deputy prosecutor attached to the court,[223] the three appeared before an investigating judge who charged them, as recommended by the prosecutor, with aggravated intentional violence and aggravated intentional damage under Criminal Code articles 218 and 411. They were then placed in pre-trial detention pending further judicial investigation.[224]

On the evening of November 4, usually CPP-friendly media reported that the three told the court that they had been provoked into an angry spontaneous attack on the two CNRP politicians because the parliamentarians had rolled down their windows and “insulted” them by accusing them and the demonstrators of being “Yuon puppets,”[225] using a historical Khmer-language term for Vietnam currently considered pejorative by many Vietnamese.[226] The CNRP’s leader, Sam Rainsy, has long accused the CPP of being too close, if not subservient, to the communist Vietnamese government.[227]

On November 5, Hun Sen repeated the version of events in the reported “confessions” as proof that the two CNRP members of parliament were not attacked as part of the anti-Kem Sokha demonstration in front of the National Assembly.[228] He said, “That violence was not an assault by the protesters. The protesters had broken up.” He said that because of the “Yuon puppet” insult hurled against the surrendered men, “[t]hey were angry, so they beat them [the two CNRP parliamentarians] up.”[229]

The same day state security forces backed up this account, reportedly reflecting what was said in the three alleged confessions. The Ministry of Interior spokesperson said that if he had been insulted as a “Yuon slave,” he “would have used a gun.”

The police’s official and public report stated:

The three were sitting drinking coffee near Independence Monument and received news there was a demonstration to remove Kem Sokha as National Assembly vice president. Then they went to the front of the National Assembly and joined with the crowd of protesters in order to understand the situation. When the demonstration ended, the protesters dispersed but the perpetrators did not go anywhere yet. After that, the two lawmakers drove in their vehicles out of the National Assembly, opened their windows and cursed: “Puppet of the Yuon!” causing them to get angry and to beat the lawmakers.[230]

This account has since been repeated nearly verbatim, in other media reports, including in media owned by Hun Mana,[231] the prime minister’s daughter.[232] On December 2, her Kampuchea Thmey news website reported that the three had consistently “confessed” to the court that, “They were sitting drinking coffee in the vicinity of the Independence Monument when they suddenly received news that there was a demonstration in front of the National Assembly demanding that Mr Kem Sokha be deposed from his position as its First Vice Chairperson, at which time they travelled to in front of the National Assembly and entered the crowd of demonstrators in order to grasp the situation with regard to this event. Then, once the demonstration was over and the demonstrators had gradually dispersed, they still did not go anywhere, that is, they waited to be the last to depart because they were not in the demonstrator group. Next, two Rescue Party National Assembly Members riding in cars exited and opened their car windows, shouting “puppets of the Yuon,” and it was only then that they became angry and simply beat up these National Assembly Members.”

On December 2, 2015, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs issued a statement saying that CNRP parliamentarians had precipitated the violence against them when they “threw derogatory remarks at some of the remaining protesters,” asserting that, “[o]utraged by this offending behavior, those protesters blocked the deputies’ cars and started beating the parliamentarians.”[233]

Meanwhile, on November 5, Kung Sophea and Nhay Chamraoen reiterated that they had done nothing to provoke the attack, now specifying in particular that they had not described anyone as a “puppet of the Yuon.”[234] Neither the video evidence described above nor any other known evidence corroborates such an allegation.

IV. Trial of Sot Vanny, Chay Sarit, and Mao Hoeun

On April 28, 2016, Sot Vanny, Chay Sarit, and Mao Hoeun faced trial on charges of intentional aggravated violence against Kung Sophea and Nhay Chamraoen and intentional aggravated damage to at least one of their vehicles. An additional hearing was held on May 10.

On April 28 local media reported the existence of official proof that the three were BHQ personnel, while quoting BHQ commander Hing Bunhieng as also finally conceding this fact. Yet local media also quoted Interior Ministry spokesperson Gen. Khieu Sopheak as saying the Phnom Penh court had still not ordered the ministry to conduct any further investigative acts with regard to the case.[235]

At the April 28 hearing, it was revealed that the prosecutor and investigating judge had concluded that there were as yet unidentified other persons involved in the crimes, but had not been charged. Judicial officials familiar with the case explained, on condition of anonymity, that the trial of the three had been severed from possible proceedings against other suspects on the basis of an argument that this would guarantee trial of the three within a reasonable time, in line with international standards.[236] In theory, this leaves open the possibility of prosecution of additional persons eventually identified as having ordered or participated in the attack.[237] However, this also allowed the judges to rule that questions about other persons were outside the scope of the proceedings. [238]

In the courtroom, while the three admitted they were BHQ personnel, they repeatedly claimed they had not gone to the demonstration, much less participated in the attack, on orders from anyone in BHQ.[239] Instead, they described themselves as BHQ intelligence officers who as a matter of routine infi"ltr"ated demonstrations to gather information on them. Each claimed that each had individually heard, while in Ta Khmao or Phnom Penh on the morning of October 26, that something was happening in front of the National Assembly and decided of his own and separate volition to see what was happening.

Although Sot Vanny and Mao Hoeun testified that Vanny had then transported Hoeun to the scene at Hoeun’s request, the three said they had not operated as part of any team and had not encountered each other at the demonstration or during the attack. Sot Vanny and Mao Hoeun said they had mingled with the demonstrators in order to be better able to gather information. They also stated that for the same reason they had remained in the area after demonstrators had mostly dispersed. They described the others who had been with them in the area south of the National Assembly during the attack on Kung Sophea and Nhay Chamraoen as loitering construction workers and motorcycle taxi drivers, not BHQ personnel. Together with Chay Sarit, they insisted they had not known who Kung Sophea and Nhay Chamraoen were, and in particular did not know they were parliamentarians. They also insisted that they and the others present whom they said had started or joined in the attack were reacting to unprovoked taunts by Kung Sophea and Nhay Chamraoen, who they say called those in the crowd “Yuon puppets.” Finally, all three denied having been involved in any damage that was inflicted on the parliamentarians’ cars.

Efforts by lawyers representing Kung Sophea and Nhay Chamroaen as victims in the case to put questions to the three to elicit some details about their BHQ role, their relationship to their superiors, and others in BHQ, and about BHQ structures, organizations, operating procedures, and chains of command were blocked by the trial judges, sometimes at the prompting of the prosecution and the defense lawyers of the three on trial, arguing that these lines of inquiry were outside the scope of the trial. On multiple other occasions, the trial judges simply allowed the accused to declare that they would not answer such questions.

The court announced that verdicts in the trial would be announced on May 27.

Acknowledgements

This report was researched and written by Asia division staff from Human Rights Watch. It was edited by Brad Adams, Asia director. James Ross, legal and policy director, and Joseph Saunders, deputy program director, reviewed the report.

Production assistance was provided by Olivia Hunter, publications associate, and Fitzroy Hopkins, administrative manager.