Summary

I liked to study so that I could have a wide mind. There was nothing I didn’t like [to study]. I had a dream to finish school and go to college, graduate, and work as an accountant.

Like millions of adolescents in Tanzania, Imani, 20, from Mwanza, a region in northwestern Tanzania bordering Lake Victoria, wanted to study as much as she could so that she could graduate, find a job, and support herself and her family. From the age of 14, when she entered secondary school, she traveled more than an hour and a half every morning to get to school:

I was very tired by the time I got to school. I started arriving late all the time. When I would arrive late I would be punished.

Imani’s plans changed when she was only 16 years old. She was sexually abused by her private tutor, a secondary school teacher whom her parents hired to teach her during the weekend. When Imani discovered she was pregnant, she informed the tutor. He disappeared.

A nurse would carry out monthly pregnancy tests and check all girls at her school, but Imani skipped school on two occasions when the nurse conducted the tests. On the third month of her pregnancy, school officials found out she was pregnant. “My dream was shattered then,” she told Human Rights Watch. “I was expelled from school. I was expelled from [her sister’s] home, too.”

Like many adolescent girls in Tanzania, Imani tried many ways to get back into education once she had her baby, who, at the time she spoke to Human Rights Watch, was three years old:

I tried [to go back to school]. I went to every [preparatory] program, [and] I went to do the [Form II] national examination. I paid the examination fee to the teachers and teachers left with the money [and did not register her] so I didn’t do my exam. This was in 2015.

When Human Rights Watch interviewed her in January 2016, Imani had just started a computer literacy program set up by a small nongovernmental organization in Mwanza to ensure more young women like her can find a way back into education.

****

Education has been a national priority for successive Tanzanian governments since independence. Tanzania has one of the world’s largest young populations, and its young people are at the heart of its aspiration to become a middle-income country by 2025.

The country’s economic and social progress and human development depends, in part, on empowering and educating this unique resource with the skills needed to take forward this nationwide goal. Quality education can lift families and communities out of poverty and increase a country’s economic growth. Completing secondary education has been shown to strongly benefit individuals’ health, employment, and earnings throughout their lives. Secondary education, including technical and vocational training, can empower young people with soft skills needed for sustainable development, including citizenship and human rights, and ensure access to essential information to protect their health and well-being. For girls, safe and equal enrollment in secondary education can act as a powerful equalizer, ensuring all girls and boys access the same subjects, activities, and career choices.

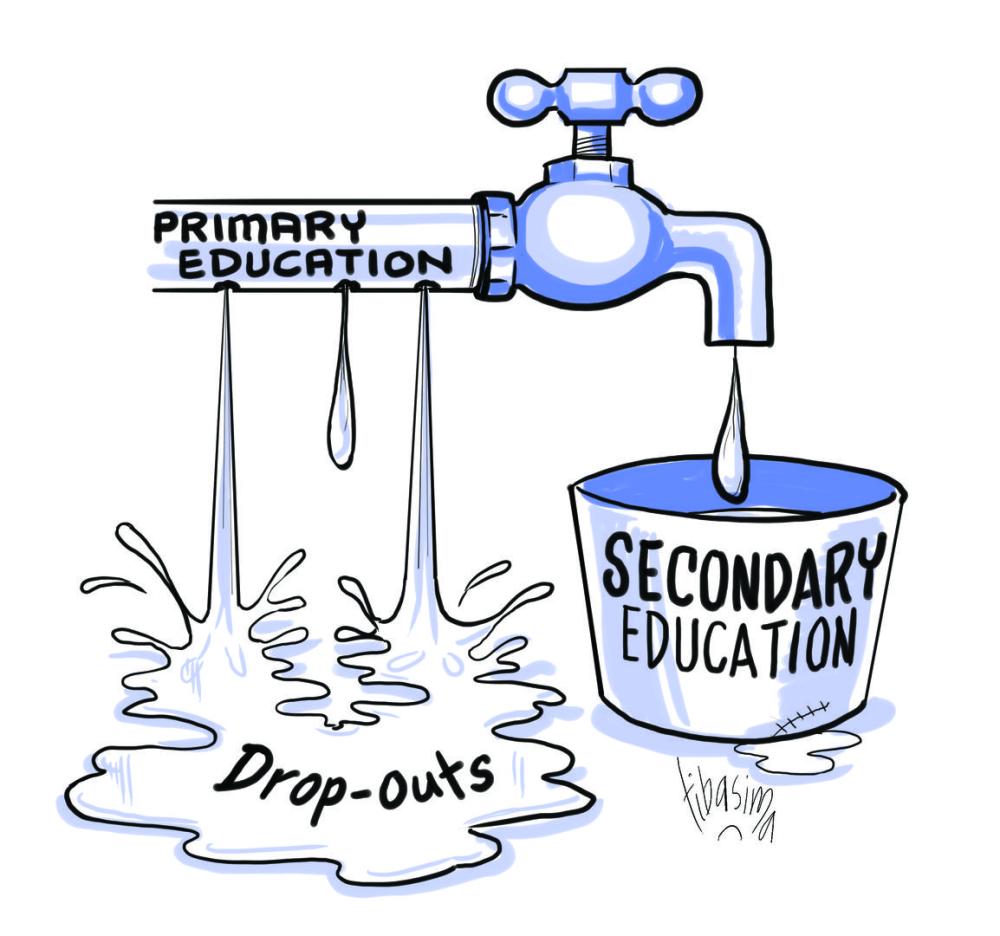

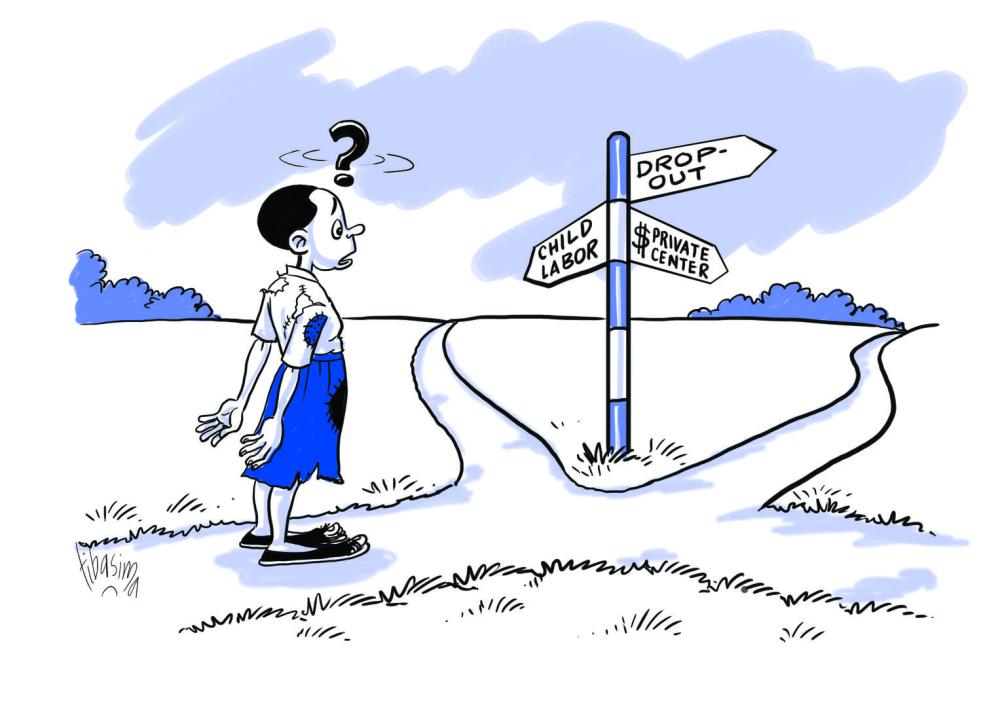

Yet, millions of Tanzanian children and adolescents do not gain a secondary education or vocational training. It is estimated that a total of 5.1 million children aged 7 to 17 are out of school, including nearly 1.5 million of lower secondary school age. Education ends for many children after primary school: only three out of five Tanzanian adolescents, or 52 percent of the eligible school population, are enrolled in lower-secondary education and fewer complete secondary education. Formal vocational training is unavailable to many of the children who want it.

Instead of enrolling in school, many children resort to child labor, often in exploitative, abusive, or hazardous conditions, in violation of Tanzanian law, to supplement their family’s income. Girls also face many challenges on account of their gender. Almost two out of five girls marry before 18 years; and thousands of adolescent girls drop out of school because of pregnancy.

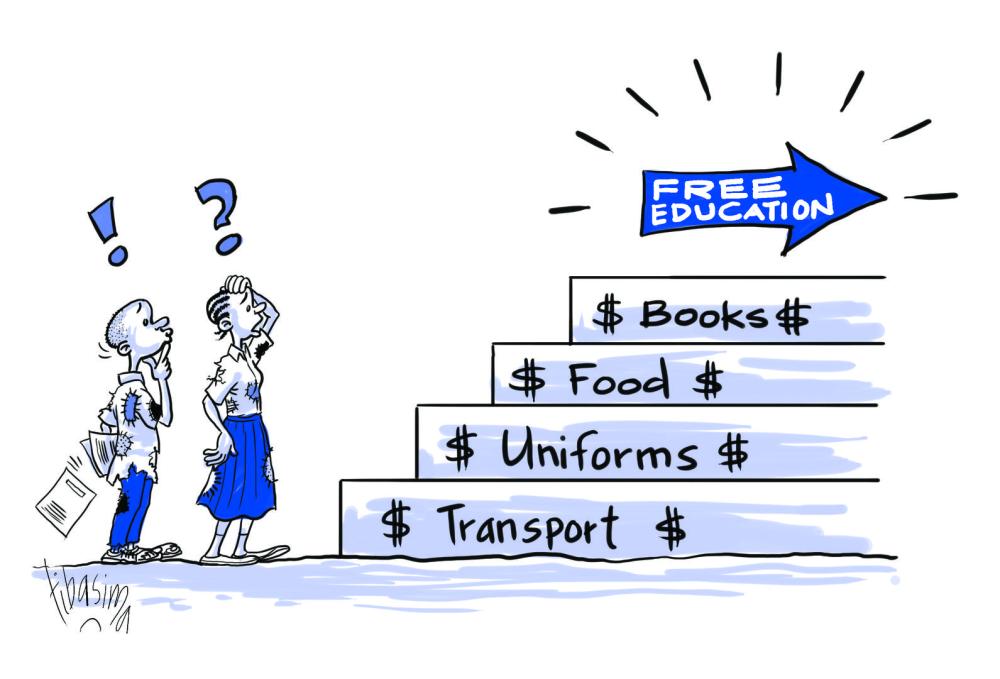

Until recently, many families did not enroll their children in secondary school because they could not afford school fees and related expenses, often costing more than Tanzanian Shillings 100,000 (US$50) per year.

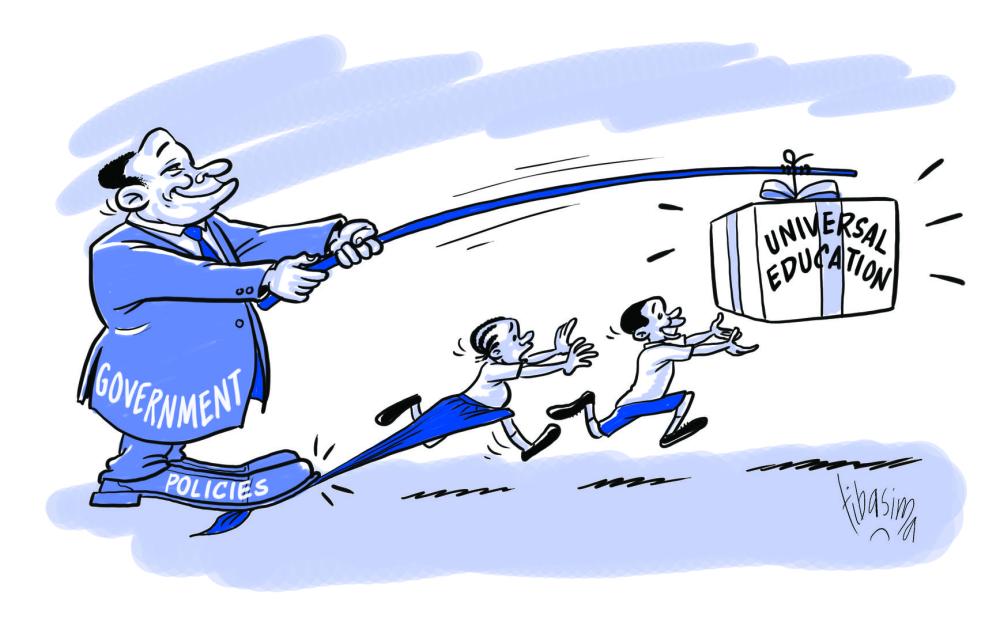

But in December 2015, Tanzania’s new government took a crucial step: it abolished all school fees and “contributions” —additional fees charged by schools to pay for the schools’ running costs—previously required to enter lower-secondary schools in the country. According to the government, secondary school enrollment has significantly increased as a result.

The abolition of school fees is one of the most important actions taken by the government to implement its ambitious education goals. Tanzania’s 2014 Education and Training policy aims to increase access to primary and secondary education, and to improve the quality of education. These goals are in line with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), a United Nations initiative which sets a target for all countries to offer all children free, equitable, and quality primary and secondary education by 2030. The goals are also in line with Tanzania’s international and regional human rights obligations to realize the right to primary and secondary education for all.

But it is only one of several short- to long-term measures needed to fully realize the right to secondary education for all children in Tanzania. This report is based on over 220 interviews with secondary school students, out-of-school adolescents, parents and a wide range of education and government stakeholders in four regions of mainland Tanzania. Research for this report was conducted throughout 2016, coinciding with an important year for Tanzania that marks the rollout of free lower-secondary education and greater attention to the government’s secondary education plans. It builds on two previous Human Rights Watch investigations about abuses against children and the impact these harmful practices have on secondary education and well-being, conducted in 2012 and 2014 – Toxic Toil: Child Labor and Mercury Exposure in Tanzania’s Small-Scale Gold Mines and No Way Out: Child Marriage and Human Rights Abuses in Tanzania.

This report highlights key barriers to secondary education that prevent many adolescents from completing secondary education, and identifies numerous areas that require the government’s action to ensure all children access secondary education equally. In particular, the report points out government policies that specifically discriminate against girls, enabling schools to expel pregnant and married girls from school, robbing them of an education, as well as a policy that allows school officials to subject students to corporal punishment that can take brutal and humiliating forms. These policies deliberately facilitate discrimination and abuse, and stand in sharp contrast to the spirit of the government’s efforts to provide universal education.

Below is a summary of Human Rights Watch’s findings:

Many Students Still Face Significant Financial Barriers: Although official fees are no longer levied in schools, many of Tanzania’s poorest students are still unable to attend school because of other school-related costs. Their parents or guardians cannot afford to pay for transport to school, uniforms, and additional school materials such as books. When secondary schools are far away, students sometimes stay in private hostels or boarding facilities near school; many poor families cannot afford this. These serve as a significant barrier to children from poor families.

The Abolition of School Fees Has Left Significant Gaps in School Budgets: Schools are not able to fund basic needs they previously paid for with parents’ contributions (additional fees charged by schools to pay for running costs), including school construction and renovation, the purchase of learning materials, and hiring of additional teachers.

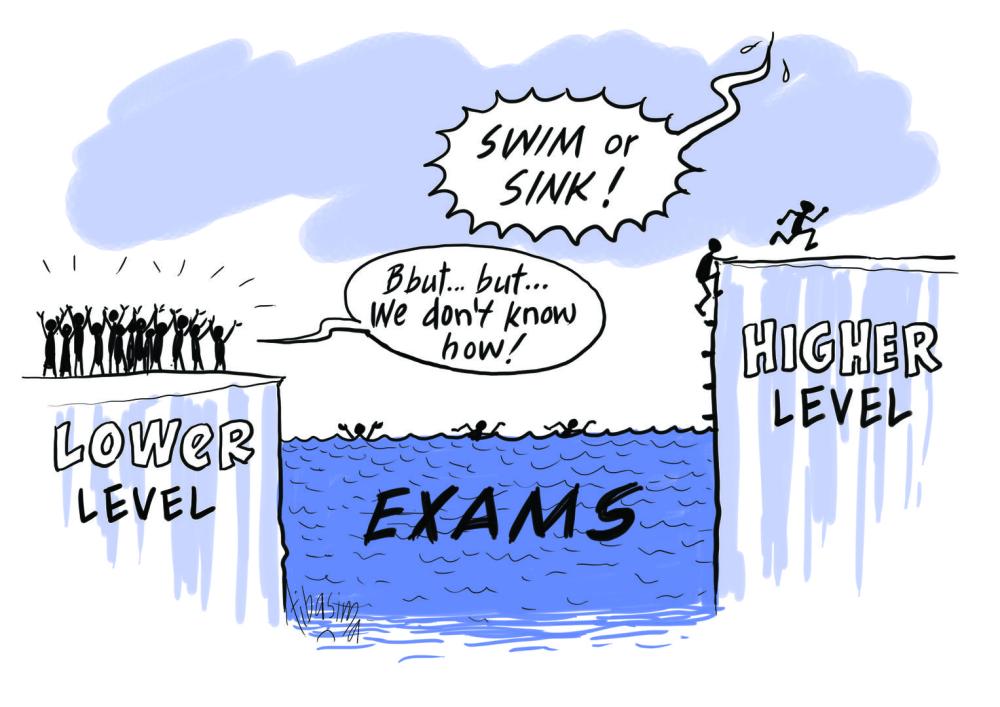

Primary School Exam Policy Blocks Access to Secondary Education: The government controls the number of students who enter secondary education by relying on the Primary School Leaving Exam (PSLE), an exam at the end of primary school. The government only allows students who pass the exam to proceed on to secondary school and it cannot be re-taken, meaning children who fail cannot continue with formal schooling and often drop out without completing the last year of primary education. Since 2012, more than 1.6 million adolescents have been barred from secondary education due to their exam results.

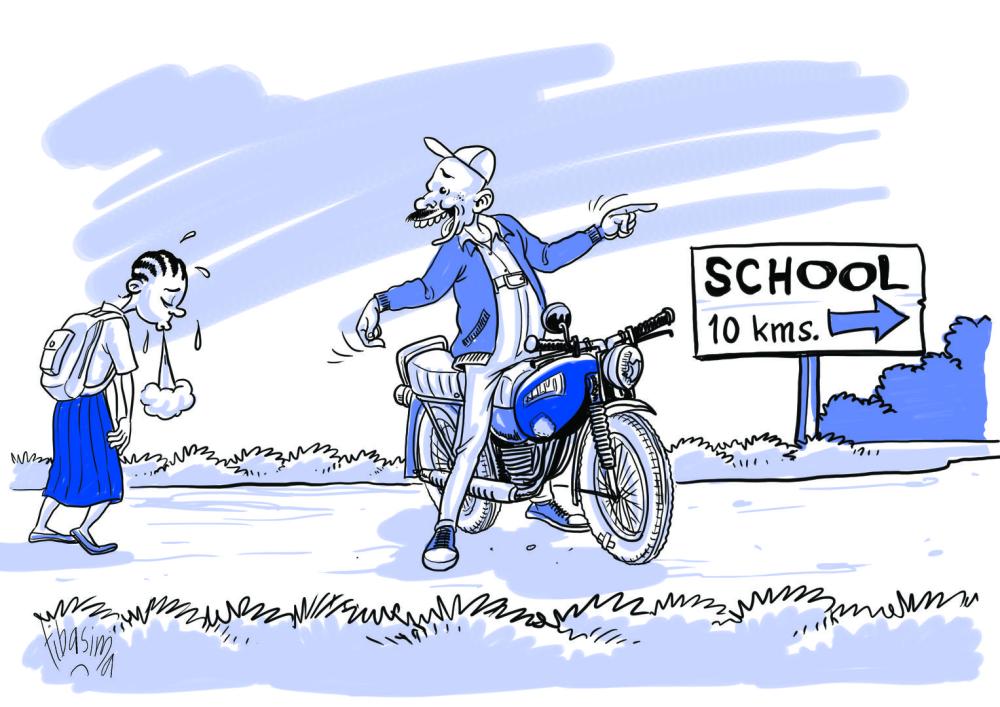

Infrastructure is Poor and Transportation to Schools is Inadequate: Students in remote and rural areas of the country have to travel very far to get to school, and many do not have access to a community secondary school in their ward. Many secondary schools suffer from a basic lack of infrastructure, educational materials, and qualified personnel. The government has not carried out its plan to build enough safe hostels to accommodate girls close to schools.

Corporal Punishment is Endemic in Secondary Schools: School officials and teachers in many schools routinely resort to corporal punishment, a practice that is still lawful in Tanzania in violation of its international obligations. Many students are also subjected to violence and psychological abuse that amounts to humiliating and degrading treatment. Some teachers beat students with bamboo or wooden sticks, or with their hands or other objects.

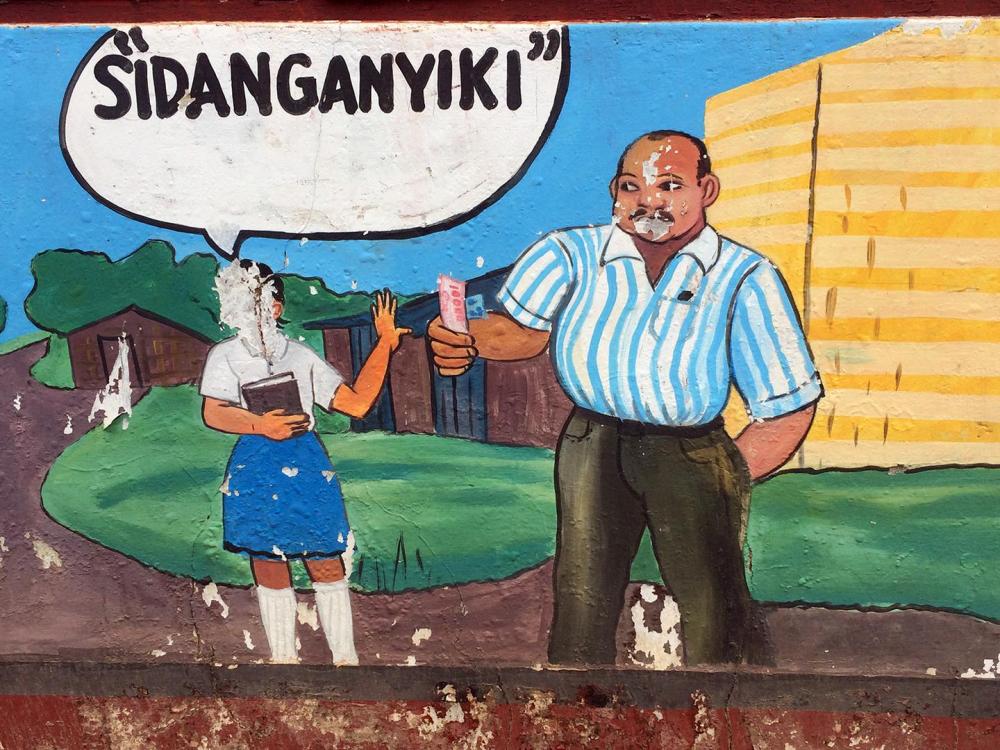

Girls Face Sexual Harassment, Discrimination, and Expulsion Due to Pregnancy or Marriage: Less than a third of girls that enter lower-secondary school graduate. Many girls are exposed to widespread sexual harassment by teachers. Many also face sexual exploitation and abuse by bus drivers and adults who often ask them for sex in exchange for gifts, rides, or money, on their way to school. In some schools, officials do not report cases of sexual abuse to police, and many schools lack a confidential mechanism to report abuse. Many, and perhaps most, schools force girls to undergo pregnancy testing in school and expel girls when they find out they are pregnant. Girls who are married are also expelled according to the government’s expulsion guidelines. Once out, girls struggle to get back into education because of discrimination and stigma against adolescent mothers, financial challenges, and the absence of a re-admission policy for young mothers of compulsory schooling age. Girls also lack access to adequate sanitation facilities, a particular problem for menstrual hygiene, and often miss school during their monthly periods.

Secondary Education Remains Inaccessible to Many Students with Disabilities: Children with disabilities face many barriers and discrimination in primary education, and very few adolescents with disabilities attend secondary schools across the country. Most secondary schools in Tanzania are not accessible to adolescents with physical or other disabilities, and are inadequately resourced to accommodate students with all types of disabilities. Many lack adequate learning materials, inclusive equipment, and qualified teachers.

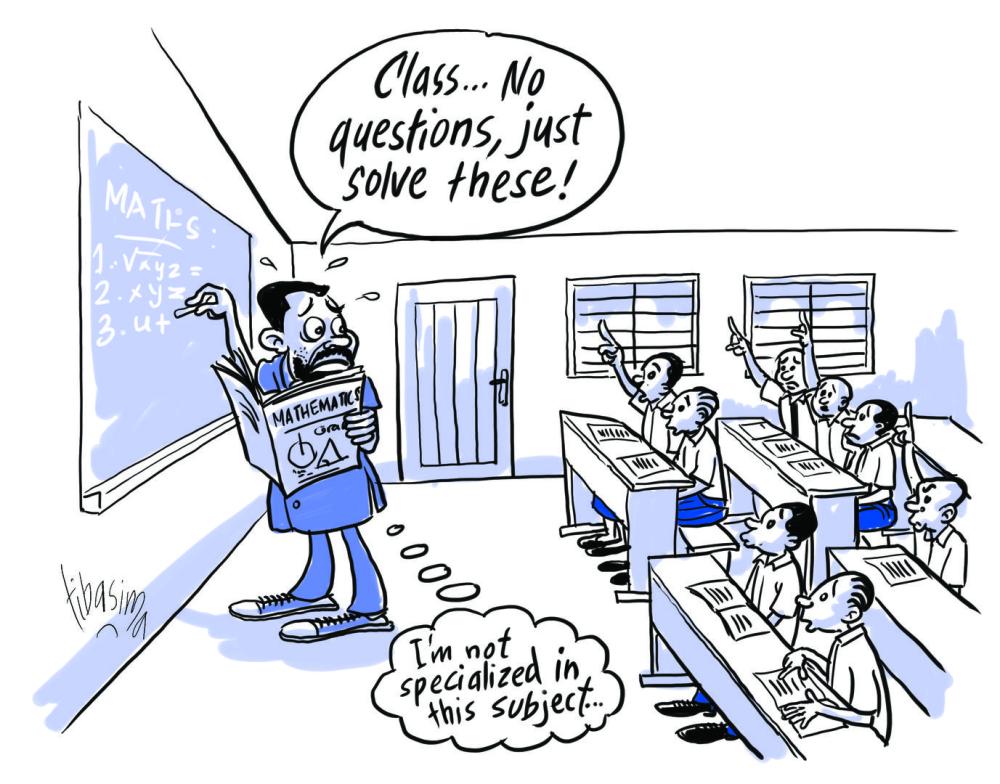

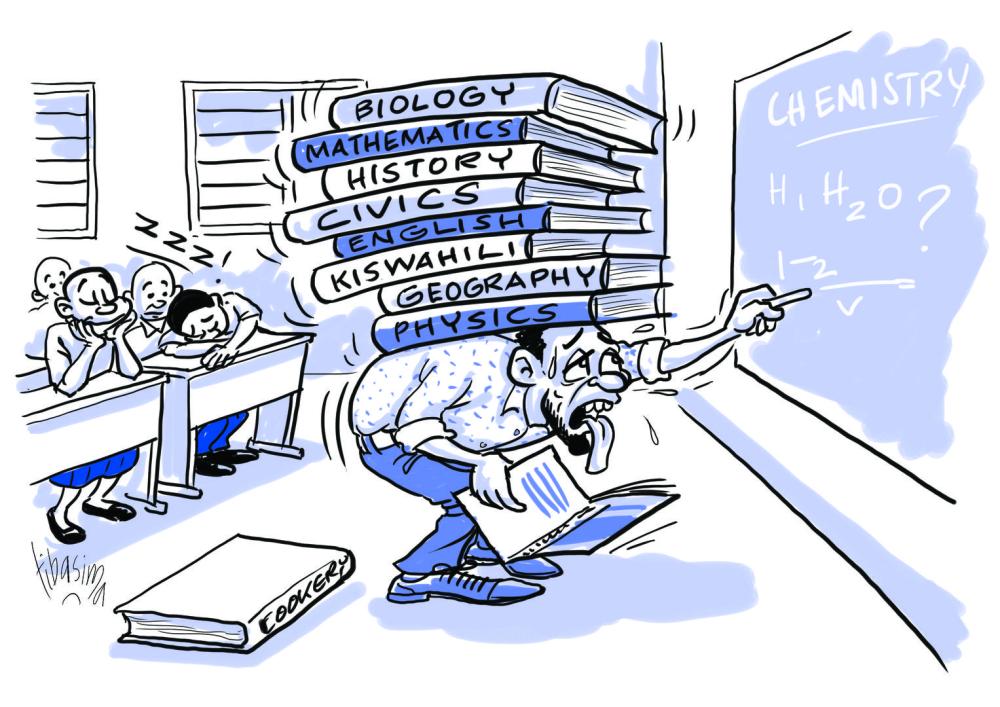

The Quality of Secondary Education is Poor: Many schools lack enough teachers to cover all subjects, with worrying gaps in mathematics and science subjects. Students sometimes go without teachers specialized in these subjects for months, and must often find alternative ways to learn these subjects or pay for private tuition, or fail exams as a result. Classes are too large with 70 students on average. In addition, many secondary schools lack adequate classrooms, learning material, laboratories, and libraries. Millions of students are obliged to take two compulsory tests in secondary education, even if they have not had qualified teachers or materials to study for those tests. Many students fail these exams, and often drop out of secondary education prematurely. Once out of school, many adolescents lack realistic options to complete basic education or to pursue technical and vocational training.

Out-of-School Adolescents Have Limited Options To Complete Lower-Secondary Education: The government provides very few realistic alternatives for several million students who do not pass the PSLE or drop out halfway through lower-secondary education, without completing basic education. A return to secondary education is possible if students enroll in private centers to study, but many students lack the financial means and information to pursue this option. Formal vocational training requires the successful completion of lower-secondary education and is costly. Other vocational training courses are limited in quality, scope, and use.

The government’s recent commitment to guarantee access to free secondary education provides new hope to hundreds of thousands of adolescents who have been barred from secondary school due to financial and other systemic barriers.

The solutions to many of the problems and barriers outlined in this report are resource intensive, and will require a greater focus on national resources for secondary education. To its credit, over the last decade, the government of Tanzania has demonstrated its political will to implement its education goals, in spite of its resource constraints. The government should, however, develop concrete plans to tackle these remaining barriers over time by adopting measures, in line with national resources and international financial support, to ensure more adolescents access a barrier-free secondary education.

In keeping with the Sustainable Development Goals, the government should focus on expanding access to secondary education, while also guaranteeing a good quality education to all students, ensuring students are empowered, gain skills, and build specialized knowledge to drive Tanzania forward. To ensure all adolescents gain skills, it should take steps to ensure out-of-school adolescents can more easily get into secondary education or quality vocational training.

To the greatest extent possible given available resources, and with financial support from its development partners, the government should speed up construction and renovation of secondary schools and ensure a good quality of education by placing sufficient numbers of qualified teachers in schools, and increasing learning materials for all students.

The government should also use this momentum to urgently review existing policies which conflict with its obligation to guarantee the right to secondary education, free from discrimination and all forms of violence.

Tanzania should take specific steps to protect the rights of girls and the rights of students with disabilities, ensuring their inclusion in secondary schools. The government should immediately adopt regulations to stop mandatory pregnancy testing of girls and allow pregnant or married girls to continue their education. It should unequivocally ban corporal punishment, and ensure students are safe from sexual harassment and abuse in schools.

Key Recommendations

To the Government of Tanzania

Ensure Access to Free Secondary Education for All Adolescents

- Ensure that all schools implement Education Circular No. 5 of 2015, the government’s policy on the removal of fees and contributions and monitor compliance.

- Progressively increase budgets to ensure that schools receive adequate government funds for all education matters, including the construction or renovation of buildings, teacher housing facilities, and learning and teaching materials.

- Progressively increase budgets available for secondary schools to ensure schools can adequately cover financial gaps previously covered through parental contributions, and meet minimum standards of funding for all secondary schools.

Phase Out the Use of Exams as Filter to Select Students for Secondary Education

- Explore all possible options to accelerate plans to phase out the use of the Primary School Leaving Exam (PSLE) to bar students who do not pass the exam from secondary education before the 2021 deadline.

- Immediately change existing policy to ensure students who do not pass the PSLE can repeat Standard 7 to gain basic skills and knowledge before they proceed to Form I.

Increase the Availability of Secondary Schools and Hostels

- To the greatest extent possible given available resources:

- Build new secondary schools and ensure all secondary schools have adequate classrooms and sanitation facilities. Take steps to ensure all parts of the new buildings, including toilets, are fully accessible to students and teachers with disabilities.

- Expedite building of safe hostels for female students.

End the Use and Tolerance of Corporal Punishment and Sexual Abuse in Schools

- Abolish corporal punishment in policy and practice, including by revoking the National Education (Corporal) Punishment Regulations of 1979, and adopting a policy and regulations that comply with Tanzania’s international and regional human rights obligations.

- Ensure cases of sexual harassment and abuse, including by bus drivers, teachers, or school officials, are reported to appropriate enforcement authorities, including police, and that cases are duly investigated and prosecuted. Teachers and drivers who are under investigation should be suspended from their job.

End Discriminatory Barriers and Sexual Abuse Against Girls in Schools

- Stop expelling pregnant and married girls from school, and revise Regulation No. 4 of the Education Regulations (Expulsion and Exclusion of Pupils from Schools) of 2002 by removing “offences against morality” and “wedlock” as grounds for expulsion.

- Immediately end pregnancy testing in schools, and issue an official Government Notice to ensure that teachers and school officials are aware that the practice is prohibited.

- Expedite regulations which will allow pregnant girls and young mothers of school-going age back into secondary school, in compliance with the 2014 Education and Training Policy.

Guarantee Inclusive Education for All Students with Disabilities

- Ensure students with disabilities have access to free or subsidized assistive devices, including wheelchairs, canes, or eye glasses, needed to facilitate their movement, participation, and full inclusion in schools.

- Take steps to ensure secondary schools with students with disabilities have an acceptable minimum of books, teaching materials, and inclusive materials for students and teachers with disabilities.

- Take steps to ensure teachers have adequate training in inclusive education. Provide training in counseling for teachers to enable them to support children with diverse disabilities and their families.

Strengthen Quality Education in All Secondary Schools

- To the greatest extent possible given available resources:

- Ensure teachers are adequately compensated, commensurate with their roles. Provide financial incentives to teachers placed in remote or under-served areas of the country, and provide adequate housing facilities for teaching staff.

- Ensure all students have access to textbooks and learning materials.

To International Donors and UN Agencies

- Urge the government to repeal the corporal punishment regulations and end the practice in schools, and provide funding to support large-scale trainings in alternative classroom management for all teaching staff and school officials.

- Urge the government to end the expulsion of female students who become pregnant, and to expedite the adoption of a robust policy that allows re-entry for parents of school-going age.

Methodology

This report is based on research conducted in January, May, and November 2016 in six districts in the Mwanza, Shinyanga, and Tabora regions of mainland Tanzania, as well as two districts of the city of Dar es Salaam.[1] Based on consultations with local and national nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), Human Rights Watch selected these regions due to vast disparities in school enrollment, rates of transition to secondary school, distance to school, the high incidence of child labor, child marriage, and teenage pregnancies, and disparities in access to education between rural and urban populations. This research builds on two separate investigations on child labor and child marriage conducted by Human Rights Watch in these regions in 2012 and 2014, which highlighted the impact of these harmful practices on access to secondary education.

Human Rights Watch conducted individual interviews with 40 children and 45 young adults. Their ages ranged from 11 to 23 years. Sixty-five of them were girls and young women; 20 of them were boys and young men. Seven interviewees had physical, sensory, and developmental/intellectual disabilities. Combined, they attended 14 primary and 30 secondary schools across different regions.

We also conducted eight focus group discussions with 88 secondary school students in four public secondary schools, and 53 out-of-school adolescents and young adults. Adolescents with disabilities participated in focus group discussions. The majority of focus group participants were under 18. In addition, we interviewed 12 parents or guardians.

In this report, the term “child” refers to anyone under the age of 18, consistent with usage in international and Tanzanian law. The term “adolescent” is used to describe children and young adults from ages 10 to 19, in recognition of students who are older than 18 and still enrolled in secondary education.[2]

Interviews were conducted in English, Kiswahili, and sign language. Interviews were translated into English by activists and representatives of nongovernmental organizations who accompanied Human Rights Watch researchers. In each case, Human Rights Watch explained the purposes of the interview, how it would be used and distributed, and sought the participant’s permission to include their experiences and recommendations in this report. Interviewees gave oral informed consent to participate.

We took great care to interview adolescents and young adults in an appropriate and sensitive manner, and offered anonymity. All interviewees were told they could discontinue the interview at any time or decline to answer any question. All names of adolescents and young people in the report are based on pseudonyms. Students’ evidence is referenced by location, and not by school, to further protect their identity.

Human Rights Watch modestly reimbursed the travel expenses of some interviewees who travelled long distances for interviews.

Researchers visited five public secondary schools and one technical and vocational center to interview 20 senior school officials and teachers. We also interviewed eight senior officials and leaders at Tanzania Teachers’ Union. Some teachers and senior school officials are referred to anonymously to protect their identity where information provided could result in retaliation by other school officials or local government authorities.

In addition, Human Rights Watch interviewed local and national government officials at the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology; the Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, the Elderly and Children; and the President’s Office for Regional Administration and Local Government, and communicated by email with government officials.[3]

Human Rights Watch also interviewed 24 representatives of NGOs, including organizations focused on education and child rights, youth-led organizations, organizations of persons with disabilities, two education experts and practitioners, and seven development partners’ representatives.

We reviewed Tanzanian national law, government policies and reports, budget statements and progress reports, government submissions to United Nations bodies, UN reports, NGO reports, academic articles, newspaper articles, and social media discussions, among others. Three NGOs shared data, case studies, and evaluations based on their surveys, programs, and outreach activities in secondary schools.

The exchange rate at the time of the research was approximately US$1 = Tanzanian Shillings (TZS) 2,200; this rate has been used for conversions in the text, which have sometimes been rounded to the nearest dollar.

I. Background: Secondary Education in Tanzania

Education has been a national priority for successive Tanzanian governments since independence.[4] The government’s drive to guarantee free primary education for all children resulted in more than 97 percent of children enrolling in primary schools in the late 2000’s.[5] With one of the world’s largest young populations under the age of 25, and 43 percent of its population under 15, Tanzania, a low-income country, faces enormous challenges in guaranteeing basic education for all.[6]

Over a decade after the rollout of free and compulsory education, approximately 8.5 million children are enrolled in six years of primary education, representing close to 77 percent of children of primary-school-going age, and 1.87 million adolescents, or 52 percent of the eligible student population, are enrolled in lower-secondary education.[7] Out of the 5.1 million children who are not in basic education, almost two million, or one in every five children, are not in primary school.[8] An estimated 1.5 million adolescents, or two in every five Tanzanian adolescents of lower-secondary school age, are out of school.[9] In 2013, Tanzania ranked 159 out of 187 in the United Nations’ global education index, a global measurement tool which measures mean years of schooling and expected years of schooling.[10]

Tanzania has maintained similar levels of education spending since 2010. According to international standards, the government should spend at least 20 percent of total national budgets on education.[11] In 2015–2016, it spent slightly over 16 percent of its national budget on education, and in 2016–2017 allocated 22 percent of its total national budget to education.[12] Most of the government’s education budget covers capital and recurrent expenditures, including teachers’ and civil servants’ salaries.[13] The government has invested more in higher education and student loans than in secondary education, though this may change with the rollout of free lower-secondary education.[14]

Although external funding has decreased in recent years, a significant proportion of funding is still sourced from donor contributions: in 2014 external aid amounted to over 46 percent of the government’s education budget.[15]

In 2016, upon announcing the rollout of free lower-secondary education, the government allocated Tanzanian Shillings (TZS) 4.77 trillion (US$2.1 billion) for its education sector, equivalent to over 22 percent of the national budget.[16] To cover additional expenses incurred with the rollout of free secondary education in the 2016–2017 school year, the government allocated an additional TZS 137 billion ($62 million), sourced from cost-cutting measures and savings within government ministries.[17]

However, according to the United Nations Children’s Fund’s (UNICEF) analysis, the government will need to progressively increase its budget allocation to secondary education to adequately fund it.[18] According to the Policy Forum, a national network of organizations working on budget transparency, the government should allocate an additional TZS 852 billion ($387 million) annually to ensure it covers the full cost of free secondary education in line with a projected increase in students, adequate number of teachers, and infrastructure. This additional funding would cover “the costs of educational delivery without payment of fees or parental contributions, allocation of the budget for inspection, and increase the development of [non-recurrent expenses] budget.”[19]

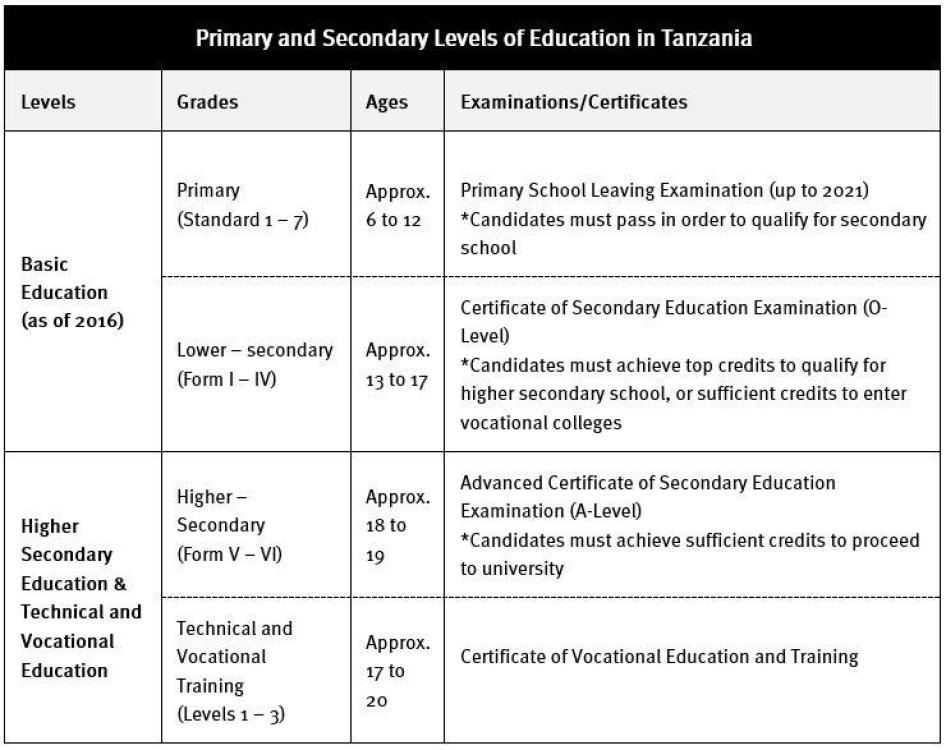

Tanzania’s Education System

Under Tanzania’s Constitution, the government has an obligation to ensure the availability of “equal and adequate opportunities” to enable all persons “to acquire education and vocational training at all levels of schools and other institutions of learning.”[20]

According to Tanzania’s Education Act, all children above the age of seven must attend and complete compulsory primary education.[21] Under current regulations, any parent or guardian who fails to ensure a child is enrolled in primary school commits an offence, and may be liable to a fine or imprisonment of up to six months.[22] Under the Law of the Child Act, children have a right to education, including a right to acquire vocational skills and training, and parents have a duty to ensure children can realize this right.[23]

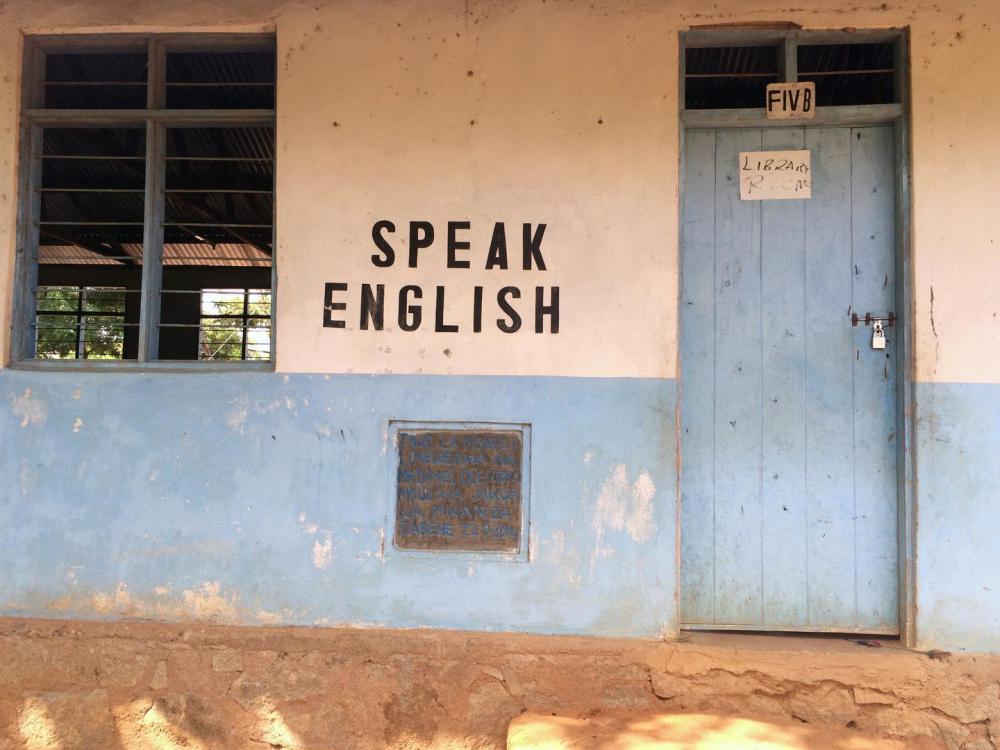

Tanzania’s 2014 Education and Training policy, officially launched in February 2015, has declared 10 years of free and compulsory basic education: six years of primary education, and four years of lower-secondary education.[24] The policy also allows the dual use of Kiswahili and English as languages of instruction in secondary schools, removing a prior policy to only teach secondary education in English.[25] Secondary school exams, however, are still conducted in English.

Under this policy, children enrolled in the first year of primary education in 2016 will go through 10 years of fully free and compulsory basic education. However, at time of writing, all other children enrolled in primary school must take a compulsory, high-stakes exam at the end of primary school in Standard 7, the final year of primary education for the current cohort of students, in order to proceed to lower-secondary education.

Once in secondary school, students are required to sit through two further national examinations at the end of Form II and Form IV. In addition to secondary schools, folk development colleges (FDCs) and vocational training centers (VTCs) offer vocational training to adolescents and young adults.

As of March 2016, there were 3,601 government secondary schools in mainland Tanzania, compared with 16,087 government primary schools.[26] The Vocational and Training Education Authority of Tanzania owns and manages 28 training centers and 10 vocational training centers, which are only available in major towns across the country.[27]

Government Efforts to Accelerate Progress in Secondary Education

The government has undertaken important efforts to improve access to secondary education in recent years and, in 2015, committed towards global goals to guarantee 12 years of free secondary education by 2030.[31] Most notably, the government took an important first step by abolishing school fees and contributions–additional fees charged by schools to pay for the schools’ running costs—for lower-secondary education in early 2016, in an effort to ensure all young people in Tanzania complete basic education.

Secondary Education Development Programme and Big Results Now

The government has undertaken to expand secondary education, including technical and vocational education, since 2000. Under its secondary education program, launched in 2005, the government said it would build at least one secondary school in every administrative ward to expand availability of secondary education and ensure students could study closer to their homes.[32]

The World Bank, one of Tanzania’s strongest development partners, provided over $300 million to support the government’s rollout of its secondary education policy.[33] In 10 years, the government increased tenfold the number of secondary schools, with a notable increase in secondary school enrollments: from 524,325 students in 2005 to 1.8 million students in 2015.[34]

In 2013, Tanzania adopted its flagship development and economic growth strategy, Big Results Now Initiative, which aims to transition the country into a middle-income economy by 2025.[35] One of the Initiative’s eight priorities focuses on education and has been rolled out through a $416 million program, $252 million of which will be provided by the World Bank and other development partners through results-based financing, where funding is disbursed once the government has achieved a number of agreed outcomes.[36] According to the Tanzanian government, the aim is to “fast track quality improvements in primary and secondary education to ensure that students are not just going to school but actually learning.”[37]

The government’s delivery of the Secondary Education Development Programme has suffered significant delays beyond infrastructural delivery, due in part to insufficient financial resources allocated for schools and the lack of rigorous implementation across the country.[38]

In 2016, Tanzania’s Minister of Education, Science and Technology announced the government’s plans to expedite the building of new schools and refurbishing old secondary schools across the country.[39] The government also began to pay capitation grants–monthly funds designed to provide schools with additional money to cover running costs per student enrolled–directly to public secondary school bank accounts in a move to reduce corruption in local governments, which previously managed and distributed funding for schools by district councils in their jurisdictions.[40] Analysis conducted by the Policy Forum shows that secondary schools only received TZS 12,000–15, 000 ($5.5–7) out of the TZS 25,000 ($11) required in capitation grants. The government also reportedly did not disburse funding to cover infrastructural costs.[41]

Free Education in Tanzania

Up until December 2015, the government relied on school fees and parental contributions to cover basic running costs, voluntary or part-time teacher salaries, building repairs, tutoring, and books for teachers and students. Secondary schools charged TZS 20,000 ($10) in school fees per year.[42]

In December 2015, upon taking office, President John Magufuli announced the government’s decision to abolish all fees and additional financial requirements up to Form IV, the last year of lower-secondary school, and underscored: “When I say free education, I indeed mean free.”[43] The measure was preceded by the new 2014 Education and Training policy, which provides for 10 years of free and compulsory primary and lower-secondary education.[44]

Prior to the start of the 2016 school year, the government issued an education circular instructing all primary and secondary schools officials not to charge school fees or contributions in the new school year.[45] The abolition of school fees, however, does not extend to folk vocational education or other non-formal education programs for adolescents of school-going age who dropped out prematurely.[46]

International Development Commitments

In 2015, Tanzania endorsed the Sustainable Development Goals, including 15-year commitments to:

Ensure that all girls and boys complete free, equitable and quality primary and secondary education leading to relevant and effective learning outcomes ...

Build and upgrade education facilities that are child, disability and gender sensitive and provide safe, non-violent, inclusive and effective learning environments for all. [47]

By 2030, the government also aspires to ensure equal access to affordable and quality technical, vocational, and tertiary education.[48] On the same timeline, all youth and a substantial proportion of men and women should have also achieved functional literacy and numeracy.[49]

Social and Economic Barriers Keeping Children Out of Secondary School

Many children of school-going age are confronted with social and economic barriers that impede their access to education, relating to gender, disability, or income. Many children and adolescents are also exposed to human rights abuses and harmful practices, including child labor and child marriage, that make schooling difficult or impossible for them.[50]

In 2015 and 2016, Tanzania became a “pathfinder country” of the United Nations’ Global Partnership to End Violence Against Children, which is rooted in a commitment to ending violence against children by 2030.[51] The government adopted a comprehensive national plan to tackle all forms of violence and harmful practices affecting children and women, including those which disproportionately affect vulnerable children, listed below.[52]

Vulnerable Children

The government estimates that 74 percent of all Tanzanian children live in “multidimensional poverty,” and that 29 percent live in households below the monetary poverty line.[53] Between 2008 and 2012, primary school net attendance among the poorest 20 percent of the population was 67.5 percent, compared with 98 percent across the entire primary school-aged population.[54]

Many children from the poorest households are exposed to the harsh consequences of economic disparities, which invariably impact on their education.[55] Economic hardship and high deprivation rates force many children into child labor, often in exploitative, abusive, or hazardous conditions including in gold mines, fisheries, tobacco farms, or in domestic work.[56] Many of these conditions are in violation of Tanzanian law.[57] Overall, 4.2 million or 29 percent of children aged 5-17 engage in child labor.[58] Among the most vulnerable children are an estimated 3 million orphans, of whom roughly 1.2 million have lost a parent due to HIV/AIDS.[59]

Child Marriage

Tanzania has high child marriage prevalence rates, with almost two in five girls marrying before 18 years.[60] Over 37 percent of girls are married by age 18, and 7 percent are married by age 15.[61] In Shinyanga and Tabora, two of the regions with the highest prevalence of child marriage and teenage pregnancies, nearly 60 percent of 20- to 24-year-old women are married by the age of 18.[62] In these regions, 23 percent of adolescents aged 15-19 are pregnant or already have children.[63]

Child marriage has a direct impact on girls’ education. One study estimates that 97 percent of married girls of secondary-school-age are out of school, compared to 50 percent of unmarried girls.[64] Not only are girls often forced to leave school by their own families; Tanzania’s school expulsion regulations also prescribe the automatic expulsion of school-going girls who enter wedlock.[65]

Tanzania’s laws tolerate early marriage. The 1971 Law of Marriage Act allows girls to marry at age 15 with parental consent, or at age 14 with a court’s consent. As early as 1994, Tanzania’s Legal Reform Commission recommended amending the Act to raise the minimum age of marriage to 21 years for both boys and girls.[66]

In January 2016, Msichana Initiative, a girls’ rights nongovernmental organization, challenged the Act in court.[67] In a landmark decision, the Tanzanian High Court ruled unconstitutional sections 13 and 17 of the Tanzania Law of Marriage Act, and directed the Attorney General to amend the law and raise the eligible age for marriage for boys and girls to 18 years.[68] In August 2016, Tanzania’s Attorney General George Masaju unexpectedly appealed against the High Court ruling.[69]

II. Tanzania’s International Legal Obligations

Right to Secondary Education

Education is a basic right enshrined in various international and regional treaties ratified by Tanzania, including the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child, and the African Youth Charter.[70]

In implementing their obligations on education, governments should be guided by four essential criteria: availability, accessibility, acceptability, and adaptability. Education should be available throughout the country, including by guaranteeing adequate and quality school infrastructure, and accessible to everyone on an equal basis. Moreover, the form and substance of education should be of acceptable quality and meet minimum educational standards, and the education provided should adapt to the needs of students with diverse social and cultural settings.[71]

Under international and regional human rights law, all persons have a right to free, compulsory, primary education, free from discrimination.[72] All persons also have the right to secondary education, which includes “the completion of basic education and consolidation of the foundations for life-long learning and human development.”[73] The right to secondary education includes the right to vocational and technical training.[74]

State Parties have to ensure that different forms of secondary education are generally available and accessible, take concrete steps towards achieving free secondary education, and take additional steps to increase availability such as the provision of financial assistance for those in need.[75] Governments should also encourage and intensify “fundamental education” for those persons who have not received or completed the whole period of primary [or basic] education.[76] According to the UN Committee on Social, Economic and Cultural Rights, the expert body that interprets the ICESCR and provides guidance to states in their efforts to implement it, the right to fundamental education extends to all those who have not yet satisfied their “basic learning needs.”[77]

The right to education entails state obligations of both an immediate and progressive kind. According to the Economic, Social and Cultural Rights Committee, steps towards the ICESCR’s goals should be “deliberate, concrete and targeted as clearly as possible towards meeting the obligations.” The Committee has also stressed that the ICESCR imposes an obligation to “move as expeditiously and effectively as possible towards that goal.”[78]

The Economic, Social and Cultural Rights Committee has also maintained that access to secondary education should not be dependent on a student's apparent capacity or ability, and should be distributed throughout the state in such a way that it is available on the same basis to all.[79] There is wide support for the notion that assessments should be used by States to demonstrate that they have fulfilled their obligation to ensure all children complete primary education of good quality, and that they are given access to good quality secondary education.[80]

Governments should guarantee equality in access to education as well as education free from discrimination. According to the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, discrimination constitutes “any distinction, exclusion, restriction or preference or other differential treatment that is directly or indirectly based on the prohibited grounds of discrimination and which has the intention or effect of nullifying or impairing the recognition, enjoyment or exercise [of rights] on an equal footing.”[81]

In addition to removing any forms of direct discrimination against students, governments should also ensure indirect discrimination does not occur as a result of laws, policies, or practices which may have the effect of disproportionately impacting on the right to education of children who require further accommodation, or whose circumstances may not be the same as those of the majority school population.[82]

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization’s Convention against Discrimination in Education—ratified by Tanzania in 1979—also articulates strong obligations on governments to eliminate any form of discrimination, whether in law, policy, or practice, which could affect the realization of the right to education. Under the Convention, states are obligated to develop policies that “tend to promote equality of opportunity and of treatment in education in the matter of education and in particular [t]o ensure that the standards of education are equivalent in all public educational institutions of the same level, and that the conditions relating to the quality of the education provided are also equivalent.”[83]

African regional human rights standards also set out specific measures to protect women and girls’ education. The Maputo Protocol on the Rights of Women in Africa specifically places obligations on governments to eliminate all forms of discrimination against women, guarantee them equal opportunity and access to education and training, and protect women and girls from all forms of abuse, including sexual harassment in schools.[84] The African Youth Charter–ratified by Tanzania in 2012–includes an obligation to ensure girls and young women who become pregnant or married before completing their education have an opportunity to continue their education.[85]

Quality of Education

It is widely understood that any meaningful effort to realize the right to education should make the quality of such education a core priority. The Economic, Social and Cultural Rights Committee has maintained that beyond their access obligations, governments need to ensure that the form and substance of education, including curricula and teaching methods, are “acceptable” to students. The Committee explained that acceptability hinges on a range of different factors, including the notion that education should be of “good quality.”[86] The aim is to ensure that “no child leaves school without being equipped to face the challenges that he or she can expect to be confronted with in life.”[87] According to the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, an education of good quality “requires a focus on the quality of the learning environment, of teaching and learning processes and materials, and of learning outputs.”[88]

Under the Convention Against Discrimination in Education, state parties are obligated to “ensure that the standards of education are equivalent in all public educational institutions of the same level, and that the conditions relating to the quality of the education provided are also equivalent.”[89]

Right to Inclusive and Accessible Education

The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) promotes “the goal of full inclusion” in all levels of education, and obliges State parties to ensure children with disabilities have access to inclusive education, and that they are able to access education on an equal basis with others in their communities.[90] Children with disabilities should be provided with the level of support and effective individualized measures required to “facilitate their effective education.”[91]

The CRPD obliges governments to ensure that “reasonable accommodation of the individual’s requirements is provided” and that “persons with disabilities receive the support required, within the general education system, to facilitate their effective education.”[92] The CRPD defines reasonable accommodation as any “means necessary and appropriate modification and adjustments not imposing a disproportionate or undue burden, where needed in a particular case, to ensure to persons with disabilities the enjoyment or exercise on an equal basis with other of all human rights and fundamental freedoms.”[93]

Under the CRPD, Tanzania is also obliged to ensure that schools are accessible to students with disabilities.[94] This entails both an obligation to ensure that facilities are physically accessible to students, and an obligation to ensure that the education schools offer is itself accessible as well. This includes, for example, the need to ensure that schools have teaching materials and methods accessible to students who are blind or have hearing disabilities.[95] Tanzania is obliged both to develop accessibility standards to guide the design of new facilities, products, and services and to take gradual measures to make existing facilities accessible.[96]

Protection from Violence, including Sexual Violence, Corporal Punishment and Cruel and Degrading Forms of Punishment

States should take all appropriate legislative, administrative, social, and educational measures to protect children from all forms of physical and mental violence, injury or abuse, neglect or negligent treatment, maltreatment, or exploitation, including sexual abuse.[97]

The CRC requires all States to “take all appropriate measures to ensure that school discipline is administered in a manner consistent with the child’s human dignity.”[98] The Committee on the Rights of the Child has defined corporal or physical punishment as “any punishment in which physical force is used and intended to cause some degree of pain or discomfort, however light.”[99]

The African Charter on the Welfare and Rights of the Child obliges States to take “all appropriate measures to ensure that a child who is subjected to school or parental discipline shall be treated with humanity and with respect for the inherent dignity of the child.”[100]

The UN special rapporteur on torture, and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment has warned states that corporal punishment is inconsistent with governments’ obligations to protect individuals from cruel, inhuman, or degrading punishment or even torture.[101] The international prohibition of torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, relates not only to acts that cause physical pain but also to acts that cause mental suffering to the victim.[102] Children and pupils in teaching institutions should be protected from corporal punishment, “including excessive chastisement ordered as … an educative or disciplinary measure.”[103]

In 2011, the African Committee of Experts on the Rights and Welfare of the Child urged all African states to adopt measures to eliminate violence in schools.[104] In 2015, the Committee on the Rights of the Child and the East African Community Legislative Assembly called upon the government to end corporal punishment in schools, and repeal or amend legislation to prohibit corporal and physical punishment in all settings.[105]

Protection from Child Marriage and Child Labor

The African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child states that, “Child marriage and the betrothal of girls and boys shall be prohibited.”[106] This Charter explicitly requires governments to take effective action, including legislation, to specify the minimum age of marriage as 18 years.[107]

The Committee on the Rights of the Child has taken a clear position on 18 as the minimum age for marriage, regardless of parental consent, and repeatedly addressed the need for countries to establish a definition of a child in all domestic legislation that is consistent with the provisions of the CRC.[108]

Tanzania’s laws tolerate early marriage. Girls may marry at age 15 with parental consent, or at age 14 with a court’s consent. In 1994, Tanzania’s Legal Reform Commission recommended amending the Act to raise the minimum age of marriage to 21 years for both boys and girls.[109]

The CRC also obliges States to protect children from economic exploitation, and from performing work that is hazardous, interferes with a child’s education, or is harmful to the child’s health or physical, mental, spiritual, moral ,or social development.[110] The Minimum Age Convention and the Worst Forms of Child Labor Convention describe what types of work amount to child labor, depending on the child’s age, the type and hours of work performed, the impact on education, and other factors.[111] Tanzania’s laws prohibit all forms of exploitative and harmful labor and work that interferes with children’s education. Children under 14 years of age cannot be employed.[112]

III. Barriers to Accessing Secondary Education

The Tanzanian government’s abolition of school fees has removed one of the most significant barriers to children’s access to secondary education. Yet a range of other barriers still prevent many students from accessing secondary education or limit their ability to do so. This includes financial barriers that affect students from very poor families, the long distance many must travel to reach school, as well as an exam which forces children to drop out of school. The Tanzanian government should develop more ambitious strategies to expedite its plans to tackle many of these barriers.

Costs of Education in Secondary Schools

Impact of the Abolition of School Fees

Prior to January 2016, school fees constituted the most onerous barrier to secondary education for many of the adolescents interviewed by Human Rights Watch. A nationwide survey of nearly 1,900 respondents conducted by Twaweza, a nongovernmental organization (NGO), found that 89 percent of parents contributed financially to public education.[113] In many cases, an inability to pay resulted in school officials forcing students to go home until schools could collect enough money to pay the school bill.

Forty-nine adolescents interviewed by Human Rights Watch dropped out permanently due to the cost of secondary education. Adolescents from poor households, those with sick or deceased relatives, and girls have been particularly affected. Abasi, a 17-year-old boy from Nzega, told Human Rights Watch:

From Form I my parents tried to pay for school fees and other contributions but it was a huge economic hardship to the family. It increased in Form II. Eventually they failed to pay the school fees, the exam fees. The teachers were chasing me home. For a whole week, every morning the teachers would chase me away and [so] I decided to drop out and find another life.[114]

Prior to 2016, public secondary schools charged Tanzanian Shillings (TZS) 20,000 (US$9) and boarding schools TZS 40,000 ($18) as official school fees.[115] In addition, students’ families were sometimes charged TZS 5,000–10,000 ($2–5) as payment for security, TZS 50,000 ($23) for desks, as well as smaller charges for uniforms, pens, exercise books, meals, exams, and transport.[116]

Some students told Human Rights Watch that teachers would sometimes cane them when they could not pay contributions requested by them, or would not allow them to enter classrooms unless they paid fees.[117] Seventeen-year-old Theodora, in Nzega, dropped out of school when she was no longer able to pay for contributions:

They [teachers] would tell us to go home … It always was in the morning. I missed many days that way. It affected my studies because if you were chased away for not making the contributions, the class continues. I missed a lot of topics … the teachers would insult us for not making contributions, they would say it’s the parent’s responsibility to pay.[118]

Similarly, when students who could not afford exam fees were not allowed to sit for exams, officials automatically stopped them from progressing to the next level of secondary school.[119]

In addition, parents have unofficially supplemented teachers’ low salaries by meeting the often compulsory costs of remedial training or private tuition offered by teachers. Interviewees reported paying between TZS 10,000 and 20,000 ($5 and 9) per subject for after-school private tuition. This type of private tutoring by teachers has been common and sometimes compulsory, according to many students interviewed by Human Rights Watch.[120]

The government’s decision to abolish all official school fees and additional financial contributions, including private tuition, as of January 2016 opened the doors to many adolescents whose parents or guardians could not afford to pay school fees for secondary school. Thus, it tackled one of the main barriers keeping children out of secondary school.

School officials interviewed by Human Rights Watch reported a significant increase in Form I enrollments because of fee-free secondary education.[121] At a school in Mwanza, the acting headmaster noted attendance had improved: “because of [the] policy, more children [are] coming to school, previously a lot of students had a problem with fees and uniforms.”[122]

Senior government officials at the Ministry of Education, Science and

Technology (MoEST) reported enrollment initially doubled in some schools, though in many cases the highest increase was seen in primary schools.[123] Exact numbers were not available at time of writing. In August 2016, the government issued a warning to school officials not to exaggerate enrollment figures in order to get more funding for schools.[124]

Agnes, 16, a former child domestic worker in Mwanza, felt positive about the new policy:

I thank the president for making secondary education free, but apart from [also] providing materials, [the] government should provide education [raise awareness] to encourage parents to send children to school, especially girls.[125]

Financial Barriers Affecting Poor Students

Education is free, but not that free … now there’s no problem with school fees but how to help those who can’t afford everything else?

—Sandra, 19, who currently attends a tailoring center in Kahama district and dropped out in Form II, Kahama, January 2016

Even after the abolition of school fees, the cost of smaller items such as uniforms, learning material, or food keeps many of the poorest students from accessing secondary education. Adult relatives or guardians with low incomes are sometimes unable to pay such costs.[126] Many families do not have access to additional social protection funding to cover these costs.[127] To the extent possible given the resources at its disposal, the government should adopt a short- to medium-term plan to ensure vulnerable adolescents can stay in school, including through targeted financial support for poor families with adolescents.

Emmanuel Samara, a teachers’ union representative from Mara region, one of the country’s poorest provinces with low secondary school enrollment, said:

Free means [refers to] school fees but there are a lot of contributions that parents are supposed to make. With the poverty level especially in my region, I don’t know if many parents will manage. We are talking about parents living on under US$1 a day, who have no ability to buy lunch. They are living on one meal a day, they have a lot of kids they cannot feed.[128]

In Dar es Salaam, Khadija, 16, has been unable to take up her placement in Form I because of other costs. She explained to Human Rights Watch researchers:

School started from 11 January but for me not yet, because my parents are not [able to] purchase school uniforms, bag, and materials. [They] told me to wait until they get the money … we need TZS 75,000 (US$34).[129]

Saida, 14, who was getting ready to enter Form II in Kahama, said: “I need support to pay for materials to go back to secondary school.”[130]

Bernard Makachia, who leads an organization providing skills and livelihoods to young mothers, explained how girls sometimes end up trading sex to meet education-related costs:

Over 20 percent of girls say poverty led them to [have sex]. But poverty [in their case] means [having no] money for transport, lunch, small pocket money, uniforms, shoes, [and to pay for] other financial demands [in education].[131]

Many Students Left Out of Education

The government’s abolition of school fees in January 2016 meant that many of those who could not get a secondary education before are now going to secondary school. However, hundreds of thousands of Tanzanian students who left school before 2016 because they could not afford fees have no realistic way to re-enter the system. The government should adopt a strategy to provide basic education to these students by making them eligible to return to secondary school to resume and complete basic education.

Make-or-Break Exam as Barrier to Access Secondary Education

Every year, hundreds of thousands of Standard 7 students sit the Primary School Leaving Examination (PSLE), a compulsory exam they need to pass in order to reach lower-secondary education.[132] Education experts argue that students are often ill-prepared to take this national exam not because of their own limitations but due to the poor quality of education in many primary schools across the country, poor student-to-teacher ratios, as well as the limited support provided to students with disabilities or those experiencing learning barriers.[133]

Hundreds of thousands of students do not pass the PSLE every year. Since 2012, more than 1.6 million adolescents have been barred from secondary education due to their exam results.[134] Formal education ends for children who do not pass the exam because children are not given another opportunity to repeat the PSLE, or to re-sit Standard 7.[135] The government uses the PSLE solely as a tool to select children that are allowed to enter secondary school, instead of using it as an assessment tool to assess students’ performance and tackle learning barriers and poor quality instruction affecting students.[136]

Research conducted by Human Rights Watch in 2013 and 2014 found that many children who did not pass the PSLE were at high risk of working in exploitative conditions in gold mines, and many were married off at a very young age.[137]

In 2016, Human Rights Watch met seven adolescents who worked as child domestic workers, gold miners, farmers, or got pregnant after failing the PSLE. They were denied an opportunity to re-enroll in school to re-take the PSLE.

Adelina, 17, found the PSLE exam difficult and did not pass the exam in 2013, which resulted in her dropping out of school and working in gold mining, age 15:

After I failed the Standard 7 exam, I was farming, I was also working in hotels and then I went to [the] mine to crush stones.[138]

The PSLE itself has been fraught with challenges and noncompliance at the school level. A 2009 evaluation found that the exam was regularly jeopardized through cheating, numerous instances of fraud committed by invigilators, teachers, and parents, and challenges in grading the exam.[139] Students reported cheating in the exam due to the shortage of placements in secondary education, the fear of being punished for poor performance, and their poor preparation.[140]

According to Richard Temu, a project officer at Uwezo, an education nongovernmental organization focused on learning assessments in East Africa, poor quality of education is a major problem: “Forty percent [of students] are not ready to join secondary school–they won’t learn anything–they’re not taught to read or write [in primary school].”[141]

The government plans to phase out the PSLE by 2021, when the generation of children presently in Standard 1 reach Standard 7.[142] This generation will be the first to automatically enroll in secondary education regardless of grades or assessments. For the next five years, however, pupils will still have to undergo the PSLE and those who fail will be barred from entering secondary school.

Clarence Mwinuka, an official in the MoEST, explained that the exam is being phased out in five years rather than immediately in order to prevent an influx of new students: “The idea is to have slow implementation–do we have enough classes? Enough teachers? The intention is there, but we can’t go ‘wholescale.’”[143]

The UN special rapporteur on education recommends that States use national assessments to demonstrate that they have fulfilled their obligation to ensure all children complete primary education of good quality, and that they are given access to good quality secondary education.[144]

As discussed above, the Tanzanian government has committed to phasing out PSLE passage as an entry requirement to secondary school by 2021. In the interim, the government should take immediate steps to ensure that students who fail the exam are not simply forced out of school. Children who fail the PSLE should be allowed to study Standard 7 in public primary schools, and supported to re-take the exam. The government should also use the PSLE as an assessment tool to ensure children have gained basic skills and knowledge, and that they are adequately prepared to enter secondary education.

Poor School Infrastructure

Schools visited by Human Rights Watch were in poor shape and lacked adequate classrooms, libraries, and adequate sanitation facilities, especially for girls and children with disabilities. They also usually do not have functioning laboratories for science instruction, and are not equipped to accommodate students with disabilities. This is the case despite the government’s commitment to equip 2,500 schools with functioning laboratories, to retrofit or modify half of secondary schools to accommodate students with disabilities, and to provide adequate sanitation facilities in 500 schools.[145]

Prior to 2016, the government’s own school-level financing program depended on at least 20 percent of community contributions to drive the expansion of secondary schools.[146] Following the abolition of all fees for schools, schools have been instructed to stop asking parents for contributions to pay for any improvement of the infrastructure, new learning materials, and the hiring of additional teachers, as was previously the practice.

In four schools, Human Rights Watch researchers observed uncompleted buildings, meant to be used as science laboratories, next to old school buildings. School officials told Human Rights Watch that construction work started with funds raised from parental contributions. Construction was halted in December 2015, when the government announced the official removal of fees and contributions, but schools have not received funding to complete construction projects.[147]

Senior school officials in three schools told Human Rights Watch that new capitation grants do not include additional budget lines to cover these expenses. This has left them without the resources needed to purchase goods or build infrastructure needed in the school. In Mwanza, an acting headmaster told Human Rights Watch:

There are shortages … we are failing to ensure a conducive learning environment. For example, [there] are not enough tables and chairs, blackboards … [we have a] shortage of [rooms for] classes.[148]

In May 2016, the MoEST announced further plans to renovate and rehabilitate several secondary schools and issue laboratory equipment.[149] In order to put its commitment to free secondary education into practice, the government needs to explore all possible avenues to dedicate more resources to building new schools and improving school infrastructure. The government should factor these additional costs into medium- and long-term planning and budgeting to ensure the secondary education policy is fully effective and free.

Inadequate Transportation

Many students have to travel long distances to get to school, impacting on their attendance and performance in school.[150] Thirteen students interviewed by Human Rights Watch walked more than one hour to get to school; others walked up to 20 kilometers or cycled between 20-25 kilometers, leaving their homes early in the morning.[151] Most of the students interviewed by Human Rights Watch said they spent their days at school tired because they had walked long distances.[152]

In Ukerewe and surrounding islands, for example, there are only 22 public secondary schools serving 26 wards. Four wards do not have a public secondary school.[153] According to local education activists interviewed by Human Rights Watch near Nansio, Ukerewe’s main city, the long distance to school, and the need to depend on ferries with unpredictable times, is one of the reasons why adolescents frequently drop out of school.[154]

In predominantly rural and remote regions like Shinyanga, where some students reported travelling up to 25 kilometers by bicycle, distance is also a significant barrier and disincentive for some students.[155] Martin Mweza, acting head teacher at a secondary school in Shinyanga, noted that many of the students at his school walked up to 10 kilometers, which constituted a significant obstacle for many.[156]

Children who arrive late told us they are often punished by their teachers for not complying with the school’s regulations.[157] Elsa, 18, walked 12 kilometers to get to school: “but walking two hours very fast. Most of the time, I’m late … sometimes [I am] punished. With strikes or [I am asked to] slash [cut] grass.”[158]

Under a government measure to improve transportation for students, private drivers are required to charge students a discounted rate. However, bus owners do not receive subsidies or compensation for students’ reduced fares.[159] Some students told Human Rights Watch that, as a result, bus drivers sometimes refuse to stop to pick up school children.[160]

Many students in Dar es Salaam, for example, complain that bus drivers and passengers physically abuse them by pushing and beating them, and in some cases, insult them.[161] The level of abuse against students who travel by bus in the city prompted Modesta Joseph, a secondary school student at the time, to create “Our Cries,” a website where students can report all types of abuse and send student-led petitions to the Surface and Marine Transport Regulatory Authority.[162]

IV. Corporal Punishment and Humiliating Treatment

We’re beaten very hard. If they beat you today, then you’re only going to feel better in two days. Every teacher beats students according to her wish. One teacher can beat you up to 15 times if they so wish.

—Rashidi, 18, Mwanza, January 21, 2016

The use of corporal punishment is a routine, and sometimes brutal, part of many students’ everyday reality in Tanzanian schools. A report produced by the African Child Policy Forum shows that over half of Tanzanian girls and boys who experienced physical abuse were punished by a teacher.[163] The Tanzanian government should take immediate steps to eliminate or combat all forms of violence in school.

Corporal Punishment as State-Sanctioned Practice

School officials and teachers routinely resort to corporal punishment—that is, any punishment in which physical force is used and intended to cause some degree of pain or discomfort, however light.[164] Senior political leaders, including President John Magufuli and the former deputy Minister of Education and Vocational Training, have repeatedly encouraged the use of corporal punishment in schools.[165] In March 2016, addressing a large crowd, President Magufuli stated: “I am wondering why they stopped caning in schools. I was also caned and that’s why I am standing here today.”[166]

Contrary to its international human rights obligations, Tanzania has national regulations on corporal punishment, including guidance on the use of caning in schools.[167] The regulations permit corporal punishment for “serious breaches of school discipline,” and “grave offences committed…inside or outside the school…deemed by the school authority to have brought or [sic] capable of bringing the school into disrepute.”[168]

School officials are allowed to apply punishment “by striking a pupil on his hand or on his normally clothed buttocks with a light, flexible stick but excludes striking a child with any other instrument or on any other part of the body.”[169]

Heads of schools are authorized to administer corporal punishment. Punishment cannot exceed four strokes. Where heads of schools’ delegate authority to another teacher, this must be in writing.[170] The regulations also include a mandatory requirement that a female pupil only receives punishment from a female teacher, or failing this, the head of school.[171] In all cases, schools administering corporal punishment must keep a record of each instance.[172]

According to the same regulations, disciplinary action can equally be taken against a student who refuses to accept corporal punishment–who may be excluded from school—or a head of school or school authority who violates these regulations.[173]

The instances of corporal punishment reported to Human Rights Watch indicate a widespread use of corporal punishment which exceeds the legal limit of the government’s current regulations.

Human Rights Watch asked senior school officials or teachers whether they reported the number of times they resorted to caning in their classrooms. One teacher who spoke anonymously said: “We’re advised that [when] students [are] caned above two [it should be] reported to the headmaster. It’s documented that you should do so, but … I may … cane more than four times and I don’t report them.”[174] A senior school official explained that his school does not follow the regulation: “To be honest, we don’t have a book record on corporal punishment.”[175]

In its 2005 report to the Committee on the Rights of the Child, the government deemed “justifiable the application of caning of unruly students in schools as falling outside the scope of corporal punishment.”[176] In response, the Committee called upon the government to repeal or amend legislation to prohibit corporal and physical punishment in all settings and “reiterated with concern that corporal punishment, including caning, remains widely practiced.” It particularly highlighted its serious concern for the application of corporal punishment as “justifiable correction.”[177]

In 2015, the East African Community Legislative Assembly also called on Tanzania to ban corporal punishment in schools.[178]

Widespread Use of Corporal Punishment

Children drop out because of the stick.

—Sandra, 19, Kahama district, January 2016

Almost all adolescents and students interviewed by Human Rights Watch were subjected to corporal punishment at some point of their school experience, and most secondary school students reported experiences with corporal punishment. The common use of corporal punishment is documented in a 2011 study on violence against children conducted by the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). It showed that both girls and boys in Tanzania commonly experienced being whipped, kicked, punched, or threatened with a weapon by teachers.[179]

According to the African Child Policy Forum, “The frequency of abuse by teachers in Tanzania is alarmingly high: 78 per cent of girls and 67 per cent of boys who reported abuse by teachers said they had been punched, kicked, or whipped more than five times.”[180] Secondary school students and teachers who spoke with Human Rights Watch said that in their schools, children are routinely beaten with sticks—bamboo or wooden sticks, which are often visible in class. In some cases, students reported being beaten by teachers using their hands or other objects. Female and male teachers reportedly hit students irrespective of their gender or disability.

Some students reported being hit in the buttocks, while female students reported being hit in the buttocks and breasts.[181] Lewis, a 20-year-old student with albinism who is in Form III at a secondary school in Shinyanga, told Human Rights Watch, “They [teachers] hit you with sticks on [the] buttocks. You lie down and they hit you in front of the class. For example, if you have not completed your notes.”[182]

Fatma, 16, said: “Teachers hit students … if you fail to explain [the class subject], they beat you … with sticks and even slap [you].”[183] Three weeks into her new school year, Aisha, 15, reported being hit with sticks “just once in the last few weeks.”[184] Sandra, 19, who dropped out of Form II in 2014, told Human Rights Watch: “When I was slapped, I felt I had the teacher’s hand marked on my face.”[185]

Many children were beaten or caned for being late, after walking for up two hours to get to school, the secondary school closest to their home.[186] Ana, 17, dropped out of Form I when she became discouraged with the long distance to school and the consequences of being late: “[You got] more than 16 canings if you were late. [I was] scared to [be] beaten, but if you were going to be absent then they would beat you [as well].”[187]

Jacklen, 17, told Human Rights Watch:

Punishment is given when you’re late, and you find that the teacher punishes you. You can be given [corporal] punishment or cutting grass while others are in class. Or mopping toilets [floor] without mops … we use grass as brooms [to mop the toilet floor].[188]

Leocadia Vedasius, a secondary school teacher at a school visited by Human Rights Watch on Ukerewe Island, said she often resorts to corporal punishment to exercise authority in classrooms of up to 60 students: “You create fear—if they see you, they feel very uncomfortable in class. Some students create problem[s] in class—you have to do something to get them to do good. [But] if they fail, we have to explain. Sometimes we have too many students … the quickest and easiest means is to use corporal punishment.”[189]

A number of teachers who spoke anonymously shared their reasons for resorting to corporal punishment. One teacher explained: “Sometimes you have to use caning materials to get them into shape.” Another teacher told Human Rights Watch he hits “[children] in the buttocks—I use it to put pain into the human body—I prefer to use caning materials when you call someone and someone runs away from you.” For another teacher, “You may speak [and] speak but nothing [happens] —so then you apply [use] caning materials.”[190]

One teacher linked his use of corporal punishment to current poor learning environments:

Here, learning is rote learning— [I use the] chalkboard, and impart [the lesson]. I have to force students to learn. [What I mean is] we have no sports or recreation. The headmaster says there’s no money for this … this [school] doesn’t have a library, there are no books. The student-to-teacher learning process [is not good].[191]

While most school officials and government officials interviewed by Human Rights Watch condoned the use of punishment, one teacher was against corporal punishment, saying: “I don’t think it [punishment] works. Misconduct has increased despite beatings and punishment. The consequences with beating a child … with anger, you exceed the advisable limit and the child suffers dramatically. When we beat them, we cause anxiety.”[192] Scientific evidence shows that a child’s brain is significantly affected by exposure to violence during childhood, and most vulnerable to trauma in the early years of a child’s life, as well as during adolescence, when adolescents mature emotionally and acquire advanced skills.[193]

According to Eric Guga, Tanzania Child Rights Forum’s executive director, corporal punishment and violence are embedded in the school culture and “everyone’s trying to justify [the abuse],” and not enough efforts have been taken to provide teachers with an alternative way of managing classrooms or to participate, engage, and teach in different ways. The problem, according to Guga, is that most school regulations stipulate rules for children’s behavior, but there are no clauses or rules for teachers.[194]