Summary

In Syria, civilian casualties from airstrikes by the US-led military coalition fighting the extremist armed group Islamic State (also known as ISIS) significantly increased in March 2017. During a July mission to Tabqa and Mansourah, two towns near Raqqa that ISIS controlled until recently, Human Rights Watch investigated several such airstrikes. In the two deadliest attacks, the US-led coalition struck a school and a market killing at least 84 civilians. Although ISIS fighters were also at these sites, the high civilian death toll raises concerns that military forces of the US-led coalition failed to take necessary precautions to avoid and minimize civilian casualties, a requirement under international humanitarian law.

The Combined Joint Task Force (CJTF), established by the US Central Command to coordinate military efforts of the coalition of countries fighting ISIS, has been conducting military operations in Syria since 2014. As part of their campaign to capture Raqqa from ISIS, Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and the CJTF launched an offensive on March 22 to capture the Tabqa dam, a strategic location 40 kilometers from Raqqa, ISIS’ de facto capital. In the days prior and weeks following, CJTF airstrikes significantly increased in the surrounding area. Local residents said that many of these strikes hit ISIS bases or fighters with relatively little civilian harm.

However, a number of strikes caused significant civilian harm as documented in this report. A local activist provided Human Rights Watch with the names of 145 civilians, including 38 women and 58 children, whom he says were killed in airstrikes in Tabqa town alone between March 19 and May 10, when SDF captured the town. The civilian harm caused by these airstrikes was not limited to casualties. Some of the airstrikes caused significant destruction of civilian property and infrastructure, as Human Rights Watch observed on the ground, and residents said that strikes that killed civilians instilled fear and pushed many to flee, adding to Syria’s displaced population.

In two of the deadliest attacks in Tabqa and Mansourah, aircraft struck a school housing displaced people in Mansourah on March 20 and a market and a bakery in Tabqa on March 22. In response to questions from Human Rights Watch, the CJTF press desk acknowledged that coalition forces carried out the Mansourah attack, saying that coalition forces targeted what they believed to be an ISIS intelligence headquarters and weapons storage facility.

As of September 18, the CJTF press desk said that the coalition was still assessing the allegations that coalition aircraft killed dozens of civilians in the Tabqa market attack. However, the circumstances of the attack – a major military offensive by Syrian ground forces allied to the CJTF to capture a strategic location just two kilometres away – make it unlikely that another actor such as Russia or Syria was responsible. In addition, a US military spokesperson acknowledged sho"rtl"y after the Tabqa attack that CJTF aircraft had carried out strikes in the vicinity and the CJTF press desk stated that coalition forces had attacked the same area in December 2016.

During a visit to Mansourah and Tabqa on July 1-4, 2017, Human Rights Watch spoke to 16 local residents. While denying that the locations were military bases, the residents said that ISIS members were present in both locations at the time of the strikes. In the case of the Mansourah school attack, they said ISIS members and their families displaced from Iraq had moved into the school prior to the attack. Some local residents also said that a vehicle equipped with an anti-aircraft cannon had been operating in the vicinity. In the case of the Tabqa market attack, local residents said that ISIS members frequently used an internet café in the market, and that there was an ISIS administrative office near the market to handle housing affairs for ISIS members.

But local residents, relatives of those killed, and survivors also said that there were dozens, if not hundreds, of civilians at each location at the time of the strikes. They said the Mansourah school housed a large number of civilians, including many completely unaffiliated with ISIS, and that the Tabqa market, which included a bakery, overwhelmingly served civilians, many of whom were queuing at the bakery at the time of the attack.

Both attacks killed dozens of civilians, they said. Human Rights Watch gathered the names of 84 civilians whom locals and relatives identified as killed in the two attacks, including 30 children. For both attacks, local residents claimed that the actual number of civilians killed is significantly higher than those they were able to identify; they said that there were large numbers of civilians present at the sites of the attacks, that bodies are still buried under the rubble, and that they did not know the names of many who were killed because they had been displaced from other areas.

As far as Human Rights Watch knows, the victims named in this report had no affiliation with ISIS. But even people affiliated with ISIS could be civilians. Family members of ISIS fighters and members who carry out exclusively administrative or other non-combat functions are also considered civilians under international humanitarian law and may not be targeted unless and only for as long as they are directly participating in hostilities.

International humanitarian law obliges US-led coalition forces and all other parties to the conflict to distinguish at all times between combatants and civilians and to ensure that the objects of an attack are military objectives and not civilians or civilian objects. The parties to the conflict are required at all times to take all feasible precautions to avoid, and in any event to minimize, civilian casualties to the greatest extent possible. In case of doubt whether a person is a civilian, that person shall be considered a civilian. Where civilians are present at the site of a military objective, coalition forces must determine that the harm caused to civilians or civilian property is proportional and not excessive in relation to the concrete and direct military advantage anticipated in the attack.

In response to questions from Human Rights Watch, the CJTF press desk said coalition forces determined prior to the Mansourah attack that there was no civilian activity at the site. While the press desk shared limited details, they said that coalition forces observed the location on multiple occasions to assess the pattern of civilian life. German media reported that a German aircraft, part of the CJTF, photographed the school the day before the attack. The CJTF press desk also said the coalition took other precautions, such as striking the school at night and selecting the size and fuzing of the munitions to minimize potential harm to civilians.

The CJTF press desk has not responded to Human Rights Watch’s question whether coalition forces knew of any civilian presence at the Tabqa market at the time of the attack, saying that they were still assessing the incident. The CJTF did not include the Tabqa market attack among cases to be investigated for civilian casualties in its monthly reports until August.

All local residents Human Rights Watch interviewed said that it was well known that there were many civilians at both sites. According to local residents, the Mansourah school had long hosted displaced civilians fleeing other parts of Syria, and civilians had used the Tabqa market throughout the years-long war. Any person with local knowledge would likely have been able to identify the substantial risk that the two sites contained significant numbers of civilians.

If the CJTF failed to detect the presence of dozens, if not hundreds, of civilians at these two sites, this raises serious concerns about how coalition forces ascertain whether civilians are in the vicinity of a target and therefore whether coalition forces took all feasible precautions to minimize civilian harm. It also raises questions about how the CJTF determines whether a person is a civilian or combatant, and therefore whether coalition forces complied with the requirement to treat a person as civilian if there is doubt and its obligation to distinguish between civilians and combatants.

If, however, the CJTF knew about the civilian presence but decided to attack nonetheless, they may have violated the principle of proportionality.

The CJTF press desk told Human Rights Watch that in their attempt to mitigate civilian harm, coalition forces “leverage all the intelligence capabilities of the Coalition and our partner forces, including human intelligence and multi-source intelligence” and that ahead of operations and targeting, they “invest a significant amount of intelligence and analysis characterizing the area to include ISIS activity, where civilians are, their pattern of life, and how structures are used.” In the case of the Mansourah strike, the CJTF press desk stated that coalition forces conducted “a pattern of life [analysis] prior to the strike but that video footage did not reflect any evidence of civilian activity prior or after the strike.” However, there is no indication in the information that the CJTF provided that coalition forces used any human intelligence to verify the target in the Mansourah strike. In response to follow-up questions from Human Rights Watch, the CJTF press desk declined to provide further details about the pattern of life analysis, saying that such information is classified and would reveal sensitive sources.

Witness statements collected by Human Rights Watch suggest that aerial monitoring of the two sites over time would have shown civilian activity. An 11-year-old child who survived the attack on the school said that children played in the school courtyard, and witnesses of the market strike confirmed that civilians were queuing at the bakery.

Finally, even if coalition forces attacked the two sites based on time-sensitive information, they should have been aware that the targets were a functioning market and a school where dozens if not hundreds of civilians were sheltering: because SDF and coalition forces were launching a military offensive that had presumably been long planned, the CJTF should have familiarized themselves with the civilian presence in the area. This raises questions about the degree to which the CJTF prioritized the limitation of civilian harm and suffering over the perceived benefits of these strikes.

The attacks on the Mansourah school and the Tabqa market are not unique. For example, on March 16, US aircraft struck a mosque near al-Jinah, west of Aleppo, killing dozens of people whom local residents identified as civilians. In a similar failure to understand the nature of the target and detect the presence of civilians, the authority that approved the strikes did not know that the target was a mosque, according to a subsequent military investigation. The investigation, however, denied the presence of large numbers of civilians and only admitted that one civilian was likely killed.

The failure of the CJTF in the Mansourah school attack, the Jinah mosque attack, and possibly also in the Tabqa market attack to adequately understand the nature of the targets and the extensive presence of civilians is particularly concerning since none of the attacks were in support of friendly ground troops in contact with enemy forces, situations that might require urgent action.

Statements from US government officials indicate that US authorities have changed the process for approval of strikes in ways that could have contributed to higher civilian casualties. US Secretary of Defense James Mattis said that US President Donald Trump ordered the military to accelerate the campaign and to delegate the authority to approve strikes to a lower level; Mattis said this would allow it “to aggressively and in a timely manner move against enemy vulnerabilities.” The previous US administration implemented similar changes in December 2016.

In correspondence with Human Rights Watch, the CJTF press desk said that there has been no change to the coalition’s rules of engagement or compliance with the law of armed conflict. However, it is hard to imagine that delegating the strike authority to a lower level in order to more aggressively attack the enemy would not impact the extent or effectiveness of precautions coalition forces take to minimize civilian harm. In the absence of more details about these changes, it is difficult to assess their precise effects, but the CJTF’s apparent failure to understand the nature of the targets and detect civilian presence in the cases described above are worrying.

The US-led military coalition should use all available means to check whether civilians are present in or near targets when conducting attacks; take "all feasible precautions" to minimize loss of civilian life; and attack military objectives only when the anticipated harm to civilians is not excessive in relation to the military gain.

In addition to the attacks on the Mansourah school and the Tabqa market, Human Rights Watch investigated three other attacks that resulted in significant civilian casualties. In two of the attacks, coalition forces carried out airstrikes apparently to support allied Syrian ground forces in combat with enemy forces. In one case, for example, SDF engaged in ground fighting with ISIS forces appear to have requested a coalition airstrike on a house where they might have believed ISIS members were hiding. However, local residents said that the 18 bodies they retrieved from the rubble a few days later were all civilians.

These attacks show the danger of using explosive weapons, which would include any air-dropped munition, in a fluid and chaotic combat environment in populated areas. Belligerents should curtail as much as possible the use of explosive weapons in populated areas due to the risks they pose to civilians.

The cases described in this report also illustrate the limitations of the CJTF’s methodology for assessing whether coalition airstrikes injured or killed civilians. In the two cases for which the CJTF had conducted assessments at the time of publication, the CJTF found that the allegations of civilian casualties were not credible. The information provided by the CJTF suggests that it did not visit the sites of the strikes or interview local residents and witnesses. This shortcoming is particularly striking since the coalition’s partner forces have been in control of these areas for months and it would have been possible for coalition investigators to visit the sites. Human Rights Watch’s own investigation suggests that had CJTF investigators visited the sites and interviewed witnesses they would not have concluded that the allegations of civilian casualties lacked credibility.

While the CJTF’s civilian casualty reports focus on whether civilians were injured or killed in specific attacks, these reports do not comment on the lawfulness of individual attacks. The CJTF should launch full investigations into all attacks that cause higher civilian casualties than expected, including those listed in this report, using the full range of investigative tools, including interviews with victims and their families, as well as local residents.

The US-led coalition should also take responsibility when its attacks kill civilians. International law requires compensation for civilian victims in the event of violations of international law. When losses occur, even in the absence of violations of international humanitarian law, civilians will be in need of assistance or redress. This can take the form of payments for loss of civilian life and property (often known as ex gratia payments) made without legal obligation and non-monetary acknowledgement of the harm done, such as apologies. In Syria, there is no clear mechanism for civilian victims or surviving relatives to obtain any form of redress from coalition forces – or any other warring party.

Beyond the human tragedy, high civilian casualties – whether from lawful or unlawful conduct – should always be cause for concern for a military force, as the damage to its reputation can be considerable. This is particularly true in the campaign against ISIS where coalition forces are seeking to deprive ISIS of future support.

Recommendations

To the Combined Joint Task Force – Operation Inherent Resolve

Minimizing civilian harm

- Take all feasible precautions to avoid or minimize civilian harm, in line with international law;

- Whenever possible, use the full range of intelligence sources available, including human intelligence, to ascertain the nature of a target and any civilian presence. Whenever possible, exercise patience to allow for proper verification of the target;

- If there is doubt about the status of a person, assume that the person is a civilian, in line with international law;

- Assume presence of civilians in residential areas, including in areas with heavy fighting given that ISIS fights from populated areas and has at times used civilians as human shields; adjust tactics to take civilian presence into account;

- Limit the use of explosive weapons in populated areas to the extent possible;

- Provide greater transparency about changes to the strike approval process;

- Conduct a review of the extent to which these changes may have contributed to the increasing civilian casualties and publish the findings.

Civilian casualty assessments and reporting

- Increase resources dedicated to assessing allegations of civilian casualties from CJTF airstrikes and publish findings;

- Publish the methodology used in such assessments, including how the assessments distinguish between civilians and combatants;

- Review the methodology used with a view to improve the accuracy of the assessments;

- Improve assessment of civilian casualty incidents by interviewing witnesses and conducting site inspections where feasible.

Investigations

- As a first step, launch investigations into airstrikes that resulted in significantly higher civilian casualties than expected, including the attacks described in this report;

- Whenever possible, conduct on-site investigations and interviews with victims and witnesses. If on-site visits are not possible, find other ways to conduct interviews with victims and witnesses, such as by secure means of communication or by interviewing victims and witnesses who have fled to areas where such interviews can be conducted;

- In the investigations, pay particular attention to whether CJTF forces complied with the requirements in international law to take all feasible precautions to minimize civilian harm and to designate a person as civilian if there is doubt;

- Promptly release the investigation reports including their conclusions with as much details as possible.

Redress for civilian victims

- Set up a mechanism to communicate the results of the investigations to civilian victims and their relatives, and consider non-monetary acknowledgements of the harm done, such as apologies, regardless of lawfulness of the attack that caused the harm;

- Create a unified, comprehensive mechanism for providing ex gratia payments to those who suffer losses due to the operations of the CJTF regardless of lawfulness of the attack that caused the harm.

Methodology

This report is based on in-person interviews conducted by Human Rights Watch staff with residents, victims, their relatives, first responders, and medical personnel during a mission to Tabqa and Mansourah, two towns west of Raqqa in northern Syria, in July 2017. Human Rights Watch visited the sites of the attacks in Tabqa and Mansourah from July 1 to 4, and interviewed locals who were present at the time of the attacks. We conducted interviews in Arabic or in English through an interpreter.

For each attack we also reviewed statements, updates, and relevant media interviews of the Combined Joint Task Force (CJTF), the operation established by US Central Command to coordinate military efforts of the coalition of countries fighting ISIS in Iraq and Syria. Because ISIS prohibited local residents from taking photos or video and tightly controlled communication, there is less audiovisual information published online about these attacks than attacks in other parts of Syria.

Human Rights Watch has chosen to publish only the names of sources who gave permission to do so and if Human Rights Watch determined that doing so would not put them at additional risk. For some sources, Human Rights Watch has used pseudonyms, either because the sources requested confidentiality, or because we determined that publishing their names could pose a risk to them.

The number of people reported killed in each case is the number of victims for whom neighbors or relatives provided basic information, such as name, gender, and age.

The massive displacement of civilians in the area, however, made it difficult to compile an exhaustive list of victims. In some of the cases, residents said that they did not know the names or identities of many of the victims because they were displaced from other areas. Many survivors also fled to other locations after the attack, making it difficult to locate and interview them. For some attacks, local sources said that the number of killed were higher than the number of names we collected. We have noted so in the text when this was the case.

I. The Global Coalition to Defeat ISIS

In September 2014, the US government announced the formation of the Global Coalition to Defeat ISIS, a coalition of 69 governments and four international institutions. In October US Central Command established the Combined Joint Task Force – Operation Inherent Resolve (CJTF) to coordinate military efforts of members of the Global Coalition in the fight against ISIS in Iraq and Syria. The CJTF is carrying out military campaigns in Iraq and Syria to capture ISIS-controlled territory, mainly by conducting aerial attacks in support of local ground forces.[1] At least nine CJTF members have conducted airstrikes against ISIS in Syria: United States, Australia, Bahrain, Canada, France, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and the United Arab Emirates.[2]

In Syria, the CJTF supports the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), an alliance of mainly Kurdish and Arab ground forces fighting against ISIS. In November 2016, SDF officially announced the start of Operation Wrath of Euphrates, a military operation to capture Raqqa, a city in eastern Syria with a pre-war population of more than 200,000 people that has served as ISIS’ de facto capital.[3]

On March 22, SDF and the CJTF launched an offensive to take control of the Tabqa dam, a strategic location about 40 kilometers west of Raqqa.[4] In addition to being the main electricity source for the region, the Tabqa dam is the main entry point from the north to Tabqa town (also known as al-Thawrah), which had a pre-war population of about 70,000 people. The offensive also involved the CJTF airlifting into ISIS-controlled territory south of the Euphrates river 500 SDF members who attacked Tabqa from the west.[5] On May 10, SDF announced that it had completely captured Tabqa town and the Tabqa dam from ISIS.[6] SDF captured Mansourah, located between Tabqa and Raqqa, in the beginning of June.[7]

Targeting

In briefings and interviews with journalists, CJTF military officials have distinguished between two types of airstrikes: deliberate and dynamic.

Deliberate strikes are those launched against targets chosen well in advance. According to Lt. Gen. Jeffrey Harrigian, commander of the US Air Force Central Command, “Deliberate targeting involves an extensive development process to ensure each one is legitimate and meets established strike criteria. This process can take from days to weeks to develop, depending on the target and the time needed to observe daily patterns of life and behavior.”[8] For these attacks, “targeteers” study the target, evaluate the weapons available, and calculate how to destroy it. For each target, the targeteers also conduct a Collateral Damage Estimation (CDE), a process to predict and mitigate collateral damage.[9]

Dynamic targeting involves strikes on “targets of opportunity,” whether unplanned or unanticipated, such as those on enemy positions in response to requests from ground forces during combat or targets identified during the course of an operation.[10] Lt. Gen. Harrigian notes that “dynamic targeting is much more responsive to emerging threats, taking anywhere from minutes to hours, depending on the type of target and environment. These are frequently discovered by ground forces or overhead aircraft.”[11] He also noted, “as with deliberate targets, we still carefully validate them and secure approval from the appropriate authority as we do with deliberate strikes.”[12] He assured journalists that “every target goes through our refined process to ensure it's not only a legitimate target under the law of armed conflict, but that it meets a threshold of proportionality and necessity.”

Statements from US government officials indicate that the CJTF has recently changed the procedure for authorizing airstrikes in ways that may have removed some safeguards and thereby contributed to higher civilian casualties. After a review of the campaign against ISIS, US President Donald Trump ordered the military to accelerate the campaign and to delegate the authority to approve strikes to a lower level; US Secretary of Defense James Mattis said this was “to aggressively and in a timely manner move against enemy vulnerabilities.”[13] These changes together with similar changes in December appear to have given military advisors at the brigade level the authority to directly deliver support such as airstrikes and artillery fire to friendly forces.[14] These changes may have limited the extent to which the military take precautions to minimize and avoid civilian casualties, thereby contributing to increased civilian casualties.[15] Because the CJTF has shared limited information about the two main attacks described in this report, it is not possible to say whether these changes affected the procedure for authorizing these attacks.

Civilian Casualties

Airstrikes in and around Tabqa increased significantly in the days just before and after March 22. Between March 19 and 23, the US-led coalition carried out 85 airstrikes in the Raqqa area, compared to 45 strikes in the five days just prior to that period, according to its daily strike reports.[16]

According to Airwars, a UK-based non-governmental organization that compiles published information of civilian casualties in Iraq and Syria, the increase in airstrikes in March also resulted in a significant increase in civilian casualties.[17] By April 13, Airwars had documented 52 incidents causing civilian casualties in Syria in March, most of them around Raqqa, resulting in an estimated 320 to 860 civilian deaths, compared to an estimated civilian death toll of 65 to 142 in February.[18]

A significant number of the March civilian casualties happened in Tabqa, which accounted for 15 of the incidents and likely a minimum of 100 civilian deaths that Airwars recorded.[19] A local activist provided Human Rights Watch with the names of 145 civilians, including 38 women and 58 children, whom he said were killed in airstrikes in Tabqa town alone between March 19 and May 10, when SDF captured the town.[20]

In contrast to Russian and Syrian authorities, the CJTF regularly publishes reports about strikes it has conducted. It also has a process by which it assesses whether the strikes caused civilian casualties. As of September 1, 2017, the CJTF had determined that “more likely than not, at least 685 civilians have been unintentionally killed [in Syria and Iraq] by coalition strikes since the start of Operation Inherent Resolve” in August 2014.[21]

The CJTF states that it:

Takes all reports of civilian casualties seriously and assesses all reports as thoroughly as possible. Although we are unable to investigate all reports of possible civilian casualties using traditional investigative methods, such as interviewing witnesses and examining the site, the Coalition interviews pilots and other personnel involved in the targeting process, reviews strike and surveillance video if available, and analyzes information provided by government agencies, non-governmental organizations, partner forces, and traditional and social media. In addition, the Coalition considers new information when it becomes available in order to ensure a thorough and continuous review process.[22]

An Airwars review of the CJTF’s civilian casualty investigations published in December 2016 made several critical remarks, but also noted that the July 2016 US Executive Order on Civilian Casualties appears to have led to key improvements in US monitoring and reporting on civilian casualties, such as, for example, greater engagement with external actors.[23] Since December 2016, the CJTF has regularly published monthly civilian casualty reports, which provide basic information about the CJTF’s own assessment of civilian casualties. In June, the US military increased the number of its staff within the CJTF assessing civilian casualties, adding five full-time members to a team of two full-time and two part-time members.[24]

Since April 2017, the monthly civilian casualty reports have included not only civilian casualties from CJTF strikes carried out by US forces but also those resulting from other members of the CJTF. This provides a more complete picture of the civilian toll from the anti-ISIS campaign. The downside, however, is that the reports do not specify which country is responsible for which strike, making it virtually impossible for victims to seek accountability.[25] Apart from the US, none of the CJTF members that fly in combat operations have admitted that airstrikes conducted by their forces caused civilian casualties, although US military officials have told Airwars that coalition partners were responsible for at least 80 civilian deaths.[26] Human Rights Watch and others have also criticized US military authorities for not making use of the full range of investigatory methods, including phone interviews with witnesses, when investigating civilian casualties from airstrikes in Syria.[27]

II. Concerns about Precautions to Protect Civilians

In two of the deadliest attacks in Tabqa and Mansourah, aircraft struck a school housing displaced people in Mansourah on March 20 and a market and a bakery in Tabqa on March 22. Both attacks killed dozens of civilians, according to witnesses, first responders, relatives, and survivors whom Human Rights Watch interviewed.

If those in the Combined Joint Task Force (CJTF) planning the attacks were unaware of the civilian presence at these two sites, this raises concerns that the CJTF failed to take all feasible precautions to avoid and minimize civilian casualties. It also raises concerns about how the CJTF determines who is a civilian and who is a combatant. If, on the other hand, the CJTF knew about the civilian presence, it may have violated the principle of proportionality.

Under international law, warring parties are under the obligation at all times to take all feasible precautions to avoid, and in any event to minimize, civilian casualties to the greatest extent possible. According to Additional Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions, warring parties have an obligation to do everything feasible “to verify that the objectives to be attacked are neither civilians nor civilian objects…but are military objectives.”[28] In case of doubt whether a person is a civilian, that person shall be considered a civilian. The protocol also includes the obligation to refrain from launching any attack that may be expected to cause “incidental loss of civilian life, injury to civilians, damage to civilian objects, or a combination thereof, which would be excessive in relation to the concrete and direct military advantage anticipated.”[29] These obligations are also considered customary law and therefore binding on states that have not become party to Additional Protocol I.[30]

Attack on Badia School in Mansourah, March 20

- Date/time: March 20, 2017, around 11 p.m.

- Location: Raqqa governorate, Mansourah

- GPS location of strike: 35.817220, 38.756306

- Civilian casualties: At least 40, including 16 children; likely higher

At about 11 p.m. on March 20, a CJTF airstrike destroyed almost completely a three-story boarding school in Mansourah. While local residents reported that ISIS maintained a presence at the school, they also said that the school hosted large number of displaced civilians.

Human Rights Watch visited the school on two separate days in early July after SDF captured the area. It interviewed 11 people with firsthand knowledge of the attack, including two survivors, first responders, and men who buried some of the dead.

The Badia school in Mansourah, a three-story structure, was a boarding school that opened in 2009 to receive students from Syria’s semi-nomadic areas.[31] According to multiple local residents, after the Syria crisis erupted in 2011, the school closed and displaced Syrians, notably from Homs and Palmyra, moved in.

Human Rights Watch interviewed in person two displaced people from Maskanah, a town west of Tabqa, who were in the school at the time of the attack: Awash, a 24-year-old woman, and her 11-year-old niece ‘Ahed:

On the day of the strike everything was normal. I was sleeping in the school. There were two strikes. My face and body got hit. I didn’t hear the explosions, only felt them. My mother went out to the corridor to get my nephew. I tried to follow, but couldn’t. I screamed out to my mother, to my brother, but couldn’t find them. In the courtyard, I found ‘Ahed and her mother. She had no clothes on and shrapnel all over the body. After I covered her with the sheets I passed out and then woke up in the Raqqa hospital.[32]

A local man who said he lived about 100 meters from the school described the immediate aftermath of the attack:

I was sleeping when loud explosions woke me. I heard about four bombs. I rushed to the school. There were bodies of men, women, and children everywhere. About 50 people were rushed to the hospital.[33]

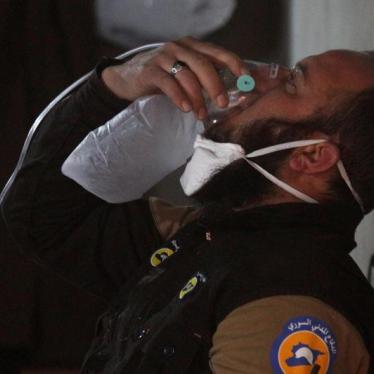

Another first responder said that he and his brother helped move 60 wounded from the area.[34] He said they initially took many of the wounded to a small clinic in Mansourah. According to Dr. Moussa Muhammad al-Ali, who works at the clinic:

It was chaos. They brought between 70 to 100 people, including both wounded and killed. Our local clinic did not have the capacity to do much for them, so we just told them to take them directly to the hospital in Tabqa.[35]

Photos of the school posted in the immediate aftermath of the attack show that the attack caused near total destruction of the building, but that parts of the building frame were still standing.

When Human Rights Watch visited the site in early July, the building was further demolished. Local residents said that this further destruction was due to the search for bodies and ISIS removing usable building materials from the site.

According to local residents, initially after taking over the area, ISIS had no presence in the school but this changed in the period leading up to the strike when families of ISIS fighters fleeing Iraq moved into the school.[36] The survivors confirmed that families of ISIS members lived in the building as well as displaced people with no ties to ISIS, such as their families.[37]

A local notable who used to pass by the front of the school reported that he started seeing ISIS fighters driving in and out of the building or sitting as a group near the entrance in the evening.[38] He believed that these men were ISIS fighters visiting their families. He also said that he heard that ISIS had held one of its Sharia courses in the school. The two survivors also said that ISIS had set up a mosque inside the school compound.

An ISIS fighter whom Human Rights Watch interviewed in the custody of Kurdish security forces (Asayish) in Qamishli also said that there were some ISIS members with their families in the school, but that it was otherwise full of displaced civilians.[39]

Two men from the area also said that ISIS fighters may have used a pickup truck equipped with an anti-aircraft cannon on the main road near the school.[40] One local resident also reported a rumor that ISIS may have driven the vehicle with the cannon into the school compound, but Human Rights Watch was not able to find anybody who had personally seen this.[41]

Despite the ISIS presence, all witnesses and local residents indicated that large numbers of civilians remained in the school.[42] The 11-year-old survivor said that children played in the school’s courtyard.[43]

In reply to questions from Human Rights Watch, the CJTF press desk acknowledged that it struck the school building on March 20, saying that the strike hit an ISIS intelligence headquarters and weapons storage facility where more than 30 ISIS militants typically stayed.[44]

The CJTF said that it observed the target on multiple occasions to assess the pattern of life, and that it struck the target at night and selected the size and fuzing of the munition to minimize potential harm to transient individuals.[45] According to German media outlets, German forces flying Tornado jets took pictures of the building a day before the airstrike and shared them with their coalition partners.[46] German media also reported that Germany flew a follow-up mission to assess the impact of the airstrikes. General Volker Wieker, the German military inspector general, reportedly met with parliament's defense committee in a closed-door session to discuss the incident on March 29.

The CJTF press desk said that video footage did not reflect any evidence of civilian activity prior to or after the strike; that it determined that the building was exclusively used by and under the control of ISIS; and that no civilians were harmed in the strike.[47] In its July “Monthly Civilian Casualty Report,” the CJTF noted with respect to the strike that “after review of available information and strike video it was assessed that there is insufficient evidence to find that civilians were harmed in this strike.”[48]

However, Human Rights Watch’s investigation shows that civilians did die in the strike. Relatives, survivors, and local residents Human Rights Watch interviewed provided the names of 40 people who died in the strike, whom they said were civilians, including 15 women and 16 children.

A number of factors indicate that the actual number of civilians killed is higher. A local municipal worker in charge of operating rubble-removing machinery said he went to the school the following morning:

I made it to the site by 7 a.m. Those at the site told us that they had removed 25 bodies the night before our arrival. After we got there, we removed 54 bodies, mostly men, but some women and children too. They were all civilian. You could tell from their clothes. An ISIS member, Abu Aisha, also was there and helped to remove the bodies. He pulled out nine bodies. ISIS members continued to remove bodies. I heard someone say that ISIS members had removed 65 bodies about 20 days later.[49]

The worker said they took many of the bodies to a nearby cemetery and buried them in mass graves. Human Rights Watch visited the site of the mass grave on July 2. A local resident and a grave-digger pointed out the graves where they said they buried some of the bodies from the attack.

The exact names and number of the victims are hard to establish because witnesses and first responders said that ISIS did not allow locals to take photos or properly document the deaths. The task is made harder by the fact that residents said that the civilians who died came from other areas and accordingly had few connections with the local community. Human Rights Watch also was unable to gather names of ISIS fighters or family members killed in the attack.

Residents said that rescuers sent most of the wounded to the hospital in Tabqa, which was also under ISIS control at the time. Human Rights Watch later visited the Tabqa hospital, after SDF forces had captured the area from ISIS, to see if there were any records that may indicate the number of bodies and wounded brought to the hospital after the attack. Security forces stationed at the hospital said that ISIS had destroyed all records before withdrawing.[50]

Survivors, local residents, and local activists provided Human Rights Watch with the following details about the dead that they knew.

21 dead from families displaced from the village of Maskanah (information collected from relatives):

- Dahiya Ramadan, female, around 60 (wife of Adel al-Farhoud)

Family of Ibrahim al-Ibrahim al-Farhoud

- Ibrahim al-Ibrahim al-Farhoud, male, around 40 (son of Dahiya)

- Halima al-Hamdi, wife of Ibrahim

- Ahmad, boy, around 5

- Isma’il, boy, around 2

Family of Isma’il al-Ibrahim al-Farhoud

- Isma’il al-Ibrahim al-Farhoud, male, 35 (son of Dahiya)

- Ala’, girl, around 7

- Amal, girl, around 5

- Malak, girl, around 3

- Adel, boy, 2 months old

Family of Ahmad al-Farhoud (cousin of Ibrahim and Isma’il)

- Ahmad al-Farhoud, male

- Nuha al-Farhoud, wife of Ahmad al-Farhoud

- Aylan, girl, age under 10

- Lana, girl, age under 8

Family of ‘Idan Ramadan

- ‘Idan Ramadan, male, 50

- Zahra, first wife of ‘Idan

- Naser Ramadan, son of ‘Idan and Zahra, around 13

- Mansour Ramadan, son of ‘Idan and Zahra, around 9

- ‘Alia, second wife of ‘Idan

- Muhammad, son of ‘Idan and ‘Alia, around 15

- Kafa’, daughter of ‘Idan and ‘Alia

Dead from families displaced from the Tadmor (Palmyra) and Sukhna areas (information collected from relatives):

Family of al-Khaled[51]

- Maha Khalid al-Salameh, around 30

- Ali Zuheir al-Khalid, boy, around 7

- Mohammad Zein Zuhair al-Khalid, boy, around 5

Family of al-Kharaz[52]

- Muwaffaq Jum’a al-Kharaz, male, 40

- Khitam Khaled Salama al-Du’as, female, 38

- Malak Muwafaq al-Kharaz, girl, 8

- Hanin Muwafaq al-Kharaz, girl, 5

- Kafa’ Jum’a al-Kharaz, female, 33

- Jawhara Jum’a al-Kharaz, female, 30

Family of Salama (provided by local activist)[53]

- Khaled Salama, male, 70

- Muna Mahmoud al-Kubba, female, 57

- Muhammad Khaled Salama, male, 28

- Ahmad Khaled Salama, male, 25

- Asma’ Khaled Salama, female, 22

- Yasmine Khaled Salama, female, 20

- Maha Khaled Salama, female, 18

- Nur Khaled Salama, female, 15

- Munaf Hussein al-‘azab, male, 35

- Fatima Akram Muhammad al-Eid, female, 33

Attack on Market, Second Neighborhood, Tabqa, March 22

- Date/time: March 22, 2017, just before 5 p.m.

- Location: Raqqa governorate, Tabqa

- GPS location of strike: 35.845879, 38.540913

- Civilian casualties: At least 44, including 14 children. Likely higher.

Just before 5 p.m. on March 22, an airstrike hit a market in the Second Neighborhood of Tabqa. The market consisted of a series of stores, including an internet café, a bakery, a hair salon, and food shops.

Local residents told Human Rights Watch that the market was full of civilians at the time of the attack. People had just exited a nearby mosque after afternoon prayers, and many were lining up at the bakery for bread. “The timing of the attack was very bad,” one survivor said. “There were so many people at the bakery and the market.”[54] Hassan Khalif, 33, whose 12-year-old son was killed in the attack while queuing to buy bread, told Human Rights Watch that the queue was particularly long as it was Wednesday and the bakery was closed on Thursdays.[55]

Muhammad al-Hussein, a local resident, told Human Rights Watch that he had gone to the bakery with his two daughters, Asma’, 12, and Ala’, 8, that afternoon. There were separate queues for men and women, he said. Because the women’s queue was shorter that day, his daughters queued while he stood across the street a few meters away.

While I was standing there, I saw the plane in the sky. We did not feel particularly concerned as Coalition planes usually don’t hit during the day and they avoid civilians. But seconds after I saw the plane, the bombs hit. I was injured as rubble fell on me and a piece of metal struck my leg. My daughter Ala’ was injured, but survived. But my daughter Asma’ died. She is still buried under the rubble to this day.[56]

Reem, a 16-year-old girl who managed the women’s section of the internet café at the market said that the café was busy when the attack happened. “There were many women there. Many of them were my friends from the neighborhood. And suddenly, everything went dark.” Reem said she was wounded in the attack, while her sister Wala’, who was also in the internet café, died. Mohammad, 17, the manager of the internet café, said he had momentarily left his shop to get something from his house; he said that there were about 40 women in the women’s section, and that he knew of 12 who survived.[57]

According to multiple witnesses and survivors, ISIS maintained an office for administrative affairs in the market, which served nearby apartments occupied by its members. Local residents also said that there were a number of ISIS members in the market, particularly in the internet café. Taha, the internet café owner, said a handful of the 12 men in the male section were ISIS members.[58] Mohammad’s friend, “Ahmad,” who looked after the internet café while Mohammad stepped out, gave a similar account. “About 50 percent of those in the internet café for men were ISIS members,” he said. “There were a few ISIS members in the market as well, but not as many as in the internet café.”[59] Only two of the people in the internet café survived, he said. Human Rights Watch observed injuries to Ahmad’s foot and hand, which he said he sustained in the attack.

Some local residents also said that they believed that a pick-up truck parked near the market belonged to ISIS; one said that he saw two ammunition boxes on the truck.[60] Human Rights Watch researchers examined the vehicle, which had been destroyed in the attack, but were unable to confirm whether the vehicle carried ammunition.

Local residents told Human Rights Watch that an airstrike had hit the area a few months earlier as well. On December 20, 2016 an airstrike hit a building adjacent to the market, which ISIS used to collect taxes; the attack destroyed the building, but left the market intact. One local resident said that the December attack had killed his sister's children, aged 6 and 12, two civilian men, and a person to whom he referred as an "ISIS woman" from Turkey.[61]

In response to questions from Human Rights Watch, the CJTF press desk acknowledged in an email that the CJTF had conducted the December attack, targeting an ISIS financial storage facility.[62] The press desk said that the CJTF had observed the target on multiple occasions to assess a civilian pattern of life; that it struck the target at night; and that it selected the size and fuzing of the munition to minimize potential harm to civilians.[63] Following questions from Human Rights Watch, the CJTF press desk said the CJTF conducted an assessment of “intelligence reports, video footage, etc” and concluded that the allegations of civilian casualties were “non-credible.”[64]

While the CJTF has not confirmed that it conducted the March 22 attack on the market, the circumstances of the attack indicate that it was responsible. The attack took place on the day that SDF launched an offensive to retake the Tabqa dam, two kilometers northeast of the market.[65] The offensive included the US military airlifting SDF fighters behind enemy lines and a US military spokesperson said that they provided them with fire support.[66] Immediately after the attack on the market, Colonel Joseph Scrocca, in response to a query from a journalist, said that the US had carried out strikes in the area, but did not confirm that a US strike had hit a bakery or the market, saying that the military would look into the allegations.[67] In addition, as noted, the CJTF has acknowledged that it struck the immediate vicinity of the market before, on December 20, 2016.

Two witnesses also told Human Rights Watch that the plane they saw carrying out the attack on the market was larger than the fighter jets they normally saw in the sky. Based on the size and shape of the plane, they believed that it was a B-52, an American long-range bomber, but Human Rights Watch has not been able to corroborate this claim.[68] According to a CJTF spokesman, the US began using B-52s in its fight against ISIS in Iraq and Syria in April 2016.[69] Neither Russian nor Syrian forces use B-52 bombers.

In its daily strike update, the CJTF said that it conducted eight strikes near Raqqa, which includes Tabqa, on March 22, but the descriptions of the destroyed targets do not allow Human Rights Watch to determine whether the market strike was one of them.[70] The CJTF listed the March 22 attack on the Tabqa market in its monthly civilian casualty reports for August, but said that it was still assessing the allegations that it carried out the strike as of September 18.[71]

Human Rights Watch has collected the names of 45 civilians whom local residents and survivors say were killed in the attack. The actual number might be higher. A survivor who said he was injured in the attack said he saw 77 bodies at the Tabqa hospital when he went there for treatment immediately after the attack.[72] Local residents said that they buried some of those killed in Tabqa, but buried others in Mansourah. A man from Mansourah who often helped bury people told Human Rights Watch that he buried 23 bodies brought from the strike on the market in Tabqa. Of the twenty-three, he said, two were foreign ISIS members.[73] Residents said that a number of the dead, including 12-year-old Asma’, remained under the rubble when Human Rights Watch visited the site.

Local residents and survivors provided Human Rights Watch with the names of 28 people who were killed in the attack. A local activist provided Human Rights Watch with 16 additional names that he said he collected from local residents, bringing the number of documented deaths to 44, including at least 14 children.

|

Name |

Gender |

Estimated Age |

|

|

1. |

Khadija Ahmad al-Ibrahim (also known as Khadija al-Botoshe) |

Female |

40 |

|

2. |

Daad Mansour |

Female |

42 |

|

3. |

Wala' |

Female |

|

|

4. |

Muhammad al-‘Alwi |

Male |

|

|

5. |

Isma’il (Hussein) Hajj Aref |

Male |

|

|

6. |

Issa Muhammad al-Mudkhir |

Male |

13 |

|

7. |

Abdallah Muhammad al-Mudkhir |

Male |

14 |

|

8. |

Haytham Khalluf |

Male |

32 |

|

9. |

Ra’ed Obeid |

Male |

|

|

10. |

Su’ad Taje |

Female |

12 |

|

11. |

Hadeel Rabih |

Female |

16 |

|

12. |

Mohammed (Jamil) Assad |

Male |

26 |

|

13. |

Ahmad al-Abed |

Male |

25 |

|

14. |

Ibrahim Shehade al-Abed |

Male |

15/16 |

|

15. |

Shehade Shehade al-Abed |

Male |

13 |

|

16. |

Ahmad al-Mustafa |

Male |

55/60 |

|

17. |

Muhannad Barko |

Male |

35 |

|

18. |

Khaled (Ahmad) al-Salal (or al-Hilal) |

Male |

45 |

|

19. |

Hussein Rashid al-Ahmad |

Male |

11 |

|

20. |

Sabri Rashid al-Ahmad |

Male |

10 |

|

21. |

Waleed Rashid al-Ahmad |

Male |

6 |

|

22. |

Ammar Kenhat |

Male |

|

|

23. |

Mayyadah Qashash |

Female |

50 |

|

24. |

Hassan Kassab |

Male |

42 |

|

25. |

Manar Hussein |

Female |

|

|

26. |

Mohammad Bibars al-Hussein |

Male |

12 |

|

27. |

Fatima al-Hendi |

Female |

|

|

28. |

Mahmoud Ahmad Mostafa/Ahmad Ali Mostafa |

Male |

60 |

|

29. |

Mahmoud Dahham al-Mohammad al-Abdullah |

Male |

|

|

30. |

Yosra Fattah |

Female |

|

|

31. |

Hamoud Staif |

Male |

|

|

32. |

Mariam al-Masri |

Female |

|

|

33. |

Uday Hassan Khleif |

Male |

12 |

|

34. |

Fayez Mohammed al-Abdullah |

Male |

|

|

35. |

Ahmad Abdul-Hay al-Juneidi |

Male |

|

|

36. |

Lina Hasan Hajja |

Female |

12 |

|

37. |

Mustafa Rajab Abdo |

Male |

13 |

|

38. |

Mansour al-Haji |

Male |

|

|

39. |

Hajy Alehaim |

Male |

|

|

40. |

Asma’ |

Female |

12 |

|

41. |

Mohammd al-Omar |

Male |

|

|

42. |

Shaker al-Omar |

Male |

|

|

43. |

Mohammed Hamdo Alosh |

Male |

|

|

44. |

Majed Mohammed Mahmoud Alosh |

Male |

III. Other Strikes Causing Civilian Casualties

Human Rights Watch investigated other strikes carried out in March and April by the Combined Joint Task Force (CJTF) that caused significant civilian casualties in the same vicinity. Human Rights Watch has not yet collected sufficient information to reach a determination as to the lawfulness of these attacks, but the high death tolls raise concerns about whether the CJTF took the necessary precautions to minimize risks to civilians.

In two of the attacks, the CJTF conducted airstrikes that were likely in response to requests from SDF ground forces as they were in close proximity to and fighting with ISIS forces in the immediate vicinity of the airstrikes. While it is more difficult to determine what precautions the CJTF could have taken in these cases, the significant civilian casualties demonstrate the risk to civilians if using explosive weapons in populated areas. In one case, Human Rights Watch found remnants of a Hellfire missile, an air-to-surface missile that can carry up to 10 kilograms of explosives. In the other cases, Human Rights Watch did not find any remnants of the weapons used, but the pattern of destruction at the locations of the attacks is consistent with the use of air-dropped bombs.

The phrase “explosive weapons in populated areas” is an emerging term in the field of international humanitarian law. The weapons involved and the impact such weapons have on civilians, however, are not new. Explosive weapons are weapons that “affect an area around the point of detonation, usually through the effects of blast and fragmentation.”[74] Such weapons range from hand grenades to air-dropped bombs, including the bombs the CJTF is now using in its war against ISIS in Syria, and the attacks documented in this report. International conventions have completely banned two types of explosive weapons – antipersonnel landmines and cluster munitions – due to their devastating impact on civilian populations.

Human Rights Watch believes that, as a matter of policy, warring parties should, in populated areas, curtail the use of explosive weapons and stop using those with wide-area effects entirely.[75]

Attack on House in al-‘Ajrawi neighborhood, Tabqa, April 25 or 26

- Date/time: April 25 or 26, 2017, between 11 p.m. and 11:30 p.m.

- Location: Raqqa governorate, Tabqa, just north of the al-‘Ajrawi roundabout

- GPS location of strike: 35.820467, 38.537615

- Civilian casualties: 16 killed, including 5 women and 9 children

Local residents told Human Rights Watch that there was heavy fighting between SDF and ISIS on April 25 and 26 in the area around the al-‘Ajrawi roundabout located at the southern entry of Tabqa.[76] They said that ISIS fighters were moving through the streets and using at least one house in the neighborhood to attack the advancing SDF forces. Around 11:30 p.m. on April 25 or 26, they said, an airstrike hit a residential house where the al-Jasem family was hiding. The al-Jasem house was located across the street from the house ISIS was using. The witnesses said they were hiding in their homes at the time of the strike so they were not able to say whether ISIS was present on top of or near the al-Jasem home. Human Rights Watch visited the site. The damage to the house is consistent with damage from an airstrike.

By the following morning, SDF were in control of the area. Local residents said that they collected the bodies of sixteen civilians, including nine children, from the targeted house several days after the attack. They provided Human Rights Watch with the names of the casualties and showed Human Rights Watch the place where they were buried.

In response to questions from Human Rights Watch, the CJTF press desk said that coalition forces conducted precision strikes in the vicinity of the location provided. On September 18 the press desk said that the CJTF was still assessing whether the strike resulted in civilian casualties.[77]

The local residents provided Human Rights Watch with the following names:

|

Name |

Gender |

Estimated Age |

|

|

1. |

Mustapha al-Jasem al-Abid |

Male |

40 |

|

2. |

Buchra al-Melhem |

Female |

39 |

|

3. |

Fahima Ahmad al-Jasem |

Female |

44 |

|

4. |

Fatima Ahmad al-Jasem |

Female |

20 |

|

5. |

Hussein Ali al-Jasem |

Male |

17 |

|

6. |

Hala Ali al-Jasem |

Female |

9 |

|

7. |

Ali Muhammad al-Jasem |

Male |

47 |

|

8. |

Maryam Muhammad al-Jasem |

Female |

44 |

|

9. |

Nur Mustapha al-Jasem |

Female |

7 |

|

10. |

Fadia Mustapha al-Jasem |

Female |

6 months |

|

11. |

Saja Mustapha al-Jasem |

Female |

11 |

|

12. |

Fawza Ali al-Jasem |

Female |

38 |

|

13. |

Lulu Ali al-Jasem |

Female |

14 |

|

14. |

Kais Ali al-Jasem |

Male |

16 |

|

15. |

Khaled Ali al-Jasem |

Male |

5 |

|

16. |

Mariam Ali al-Jasem |

Female |

9 |

Attack on House near Palestine Street, Tabqa, Unknown Date

- Date/time: Unknown (before May 5)

- Location: Raqqa governorate, Tabqa

- GPS location of strike: 35.827932, 38.547741

- Civilian casualties: 18 killed, including 3 women and 11 children

Likely in late April, CJTF airstrikes struck a house in an eastern neighborhood of Tabqa, near Palestine Street, reportedly killing 18 members of the Dalo family. Two residents who said they lived on the street where the house was struck told Human Rights Watch that there was heavy fighting between SDF and ISIS in the area at the time of the strike.[78] Neither could remember the exact date but indicated that SDF forces were trying to advance from the east and ISIS fighters were moving between houses in their neighborhood and firing at the advancing forces. Muhammad, the owner of the house that came under attack, told Human Rights Watch that he was not present at the time of the attack – he had left his house as fighting approached the area – but that he gave his keys to his neighbors, the Dalo family, as his house had thicker walls and still had water.

Local residents told Human Rights Watch that one munition hit a narrow street in front of the house and killed an ISIS fighter. A second munition hit the house where the Dalo family had sought refuge killing all 18 members of the family, including 3 women and 11 children.

Human Rights Watch found in the rubble of the house remnants of an air-launched Hellfire missile with a Commercial and Government Entity Code (or CAGE) – a unique identifier assigned to suppliers to various government or defense agencies – corresponding to Alliant Techsystems Operations LLC in Rocket Center, West Virginia. Alliant is a well-known supplier of warheads and rocket motors to Lockheed Martin, the prime contractor for the Hellfire missile.[79]

The owner of the house provided Human Rights Watch with the names of those killed:

|

Name |

Gender |

Estimated Age |

|

|

1. |

Abdel Jalil Muhammad Dalo |

Male |

48 |

|

2. |

Saleha Ahmad Dalo |

Female |

44 |

|

3. |

Ameena Abdel Jalil Dalo |

Female |

13 |

|

4. |

Muhammad Abdel Jalil Dalo |

Male |

11 |

|

5. |

Shahad Abdel Jalil Dalo |

Female |

9 |

|

6. |

Hamza Abdel Jalil Dalo |

Male |

5 |

|

7. |

‘Ahed Abdel Jalil Dalo |

Male |

7 |

|

8. |

Khaled Muhammad Abdel Jalil Dalo |

Male |

46 |

|

9. |

Amena Ahmad Dalo |

Female |

38 |

|

10. |

Muhammad Khaled Dalo |

Male |

19 |

|

11. |

Ameena Khaled Dalo |

Female |

17 |

|

12. |

Fatema Khaled Dalo |

Female |

13 |

|

13. |

Omar Khaled Dalo |

Male |

5 |

|

14. |

Reem Khaled Dalo |

Female |

7 |

|

15. |

‘Ayoush Abdel Jalil Dalo |

Female |

50 |

|

16. |

Abd al-Razzaq al-Mer’i (al-Sanani) |

Male |

50 |

|

17. |

Bayan Abd al-Razzaq al-Mer’i |

Female |

17 |

|

18. |

Rawan Abd al-Razzaq al-Mer’i |

Female |

13 |

Attack on House in Mansourah, March 30

- Date/time: March 30, around 11:15 p.m.

- Location: Raqqa governorate, Mansourah, house of Abdel Aziz al-Faraj

- GPS location of strike: 35.848105, 38.735632

- Civilian casualties: Six

Relatives living nearby told Human Rights Watch that on March 30 at around 11:15 p.m. an airstrike hit the house of Abdel Aziz al-Faraj, killing him and his family.[80] The relatives said that the family was not affiliated with ISIS and that ISIS was not present in the immediate vicinity of the house. They said that ISIS was, however, digging tunnels nearby.

On September 18 the CJTF press desk said that it was still assessing whether it was responsible for the strike and whether the strike resulted in civilian casualties.[81]

Relatives provided Human Rights Watch with the names of those killed:

|

Name |

Gender |

Estimated Age |

|

|

1. |

Abdel Aziz al-Faraj |

Male |

|

|

2. |

Lina al-Faraj |

Female |

|

|

3. |

Maria |

Female |

8 |

|

4. |

Ammar |

Male |

5 |

|

5. |

Ala’ |

Male |

3 |

|

6. |

Anwar |

Male |

3 months |

Acknowledgements

This report was researched and written by Ole Solvang, deputy director of the Emergencies Division and Nadim Houry, director of the Terrorism and Counterterrorism Division, at Human Rights Watch. The report was edited by Sarah Leah Whitson, director of the Middle East and North Africa Division. Clive Baldwin and Tom Porteous provided legal and program reviews. Mark Hiznay from the Arms Division and Sarah Margon, Washington director, provided specialist reviews.

Production and editorial assistance was provided by Michelle Lonnquist, associate in the Emergencies Division. Production assistance was provided by Olivia Hunter, photography and publications associate, Jose Martinez, senior coordinator, and Fitzroy Hepkins, administrative manager.

Human Rights Watch is grateful to the many witnesses, family members, journalists, first responders, and others whose assistance made this report possible.