Summary

The Zambian government regards agriculture as a “panacea” for rural poverty, and the country’s leaders have been promoting agribusiness investments on huge swaths of land. However, flaws in the government’s regulation of commercial agriculture, and its poor efforts at protecting the rights of vulnerable people, instead of helping people climb out of the poverty mire, are actually hurting them. Families that have lived and farmed for generations on land now allocated to commercial farms are being displaced without due process or compensation. Some have been left hungry and homeless.

Any one commercial agriculture project, whether a massive investment by foreign investors on tens of thousands of hectares of agricultural land, or smaller land deals on a few hundred to a few thousand hectares, may impact individuals and households. Without proper safeguards, they may have a tremendously negative cumulative impact on local communities. Rural people suffer when governments fail to properly regulate land deals, large or small, and the operation of commercial farms. That is precisely what is happening in some rural communities in Zambia.

In conducting research for this report, Human Rights Watch interviewed, in 2016 and 2017, more than 130 rural residents whose families had lived for years, and sometimes generations, in Serenje district, in Zambia’s Central Province. We also interviewed officials at the district, provincial, and central levels of government, in addition to representatives of some commercial farms in the district, lawyers, analysts and other experts. Human Rights Watch examined the impact of six commercial farms on local communities in Serenje district. Four of these farms were fully operational, had cleared land of trees and most settlements, were in the process of clearing more land, and were cultivating. The other two commercial farms planned to start clearing fields as soon as they could get residents off the land. The farms that are fully operational grow soybeans and wheat, along with other crops, largely for export.

This report examines the human rights impacts of the activities of commercial farms on residents, including the distinctive impacts on women as a result of their social roles and status, and the fact that they have the least opportunity to negotiate and assert their rights. The report documents the displacement of long-term residents who lived and farmed land that has been leased to commercial farmers, and the negative impact of their displacement on their health, housing, livelihoods, food and water security, and children’s education.

Women described enormous struggles to sustain their families after losing access to fertile land for cultivating food crops, safe water for drinking and household use, and hunting or foraging grounds. Some complained about a lack of nutritious meals because they could no longer grow sufficient food, and what they could grow did not provide nutritive variety. Mothers described stretching out what would be a single meal into several portions throughout the day, offering only one meal a day, or going hungry so their children could eat. Many women said that after being displaced, they had to trek long distances to obtain water.

International human rights law does not bar Zambia’s government from displacing people to make way for commercial farms or other projects. While many residents have long-term ties to the land and can assert legitimate tenure rights, some of the people being evicted may in fact have arrived recently and have few or no legitimate tenure rights to the land they occupy. However, in most of the cases we examined, evictions were carried out with little regard for the protections Zambian and international law both require in terms of due process, resettlement, or compensation. Some were carried out with such flagrant disregard for residents’ rights, and with so little real opportunity to contest their legality, that they amounted to forced evictions. Zambian law prohibits forced evictions, and international law requires the government to prevent them.

Human Rights Watch findings revealed that the situation in Serenje is not an aberration. Rather, the abuses related to commercial farming and the rights of residents are rooted in much larger failures of regulation, oversight, and rights protection on the part of Zambian authorities.

We focused on Serenje district because it represents both old (projects that have started production) and new agricultural ventures, providing an opportunity to examine human rights risks at all stages of investment. This district, in Zambia’s fertile and water-rich Central Province, houses the Nansanga farm block, which is part of Zambia’s “Farm Block Development Program,” in which the government is investing in infrastructure and offering favorable terms to entice investors. The district also has older farm blocks, and ample experience with how commercial farming operations can help or hurt the communities around them. As a district touted as a prime place for commercial farming, it should represent a best-case scenario, a model for how commercial agriculture can succeed while respecting the rights of rural residents. Instead, it illustrates broken promises, governance failures, and human rights abuses connected with commercial farming.

Lack of Meaningful Consultations

Zambian law requires that traditional chiefs—authorities recognized by government—consult with affected communities and obtain their consent before agreeing to convert lands under their control (known as customary areas) to state land that authorities can lease directly to investors. It also requires consultation with affected communities as projects that will impact them move forward.

Residents on most farms said these consultations did not happen, or were so haphazard as to be meaningless. Officials said rural land in Serenje was converted from customary to state land over the past decades, often without the knowledge of local communities and through procedures that many question. Many residents were blindsided when commercial farmers arrived; their first inkling that the land had been leased was when a farmer appeared to survey the land. In many cases, any “negotiations” around compensation or resettlement were under duress, as commercial farmers threatened to bulldoze homes and crops if residents did not vacate their homes. Many women told Human Rights Watch that they did not participate in any negotiations, fearing violence.

Several commercial farmers told Human Rights Watch that they had expected the government to remove people living on the farm plots they acquired. Instead, they said they had to decide how to deal with the families they found on the land. Many commercial farmers regarded these residents as “squatters” who had no legitimate right to reside on the plots in the first place and as such were not entitled to any particular due process or compensation. Several told Human Rights Watch that they had no clue what Zambian law required of them. One commercial farm had a better track record than the others in terms of compliance and addressing impacts on residents, but even that farm would have benefitted from greater oversight and guidance from government officials.

Governance Failures

The government of Zambia has exercised very poor oversight and enforcement of legal requirements over commercial farms. It has generally failed even to verify whether basic requirements such as the conduct of environmental and social impact assessments and the issuance of mandatory permits and licenses have been met. Zambian laws say that environmental impact assessments (EIAs), which should also address some social impacts, should be conducted before a project starts, and that government agencies must monitor impacts. Some commercial farmers cleared land and started operations well before required licenses and permits were issued, and some had never submitted environmental impact assessments. Government officials told Human Rights Watch that due to resource constraints, they did little monitoring of commercial farms.

The government officials we interviewed generally acknowledged that commercial farming in Serenje has been handled poorly. Officials in multiple government agencies blamed other agencies—never their own—for poor monitoring and oversight. Officials are not being held accountable for failing to enforce Zambia’s laws on land, the environment, agriculture, investments, and resettlement.

Displacement and Suffering

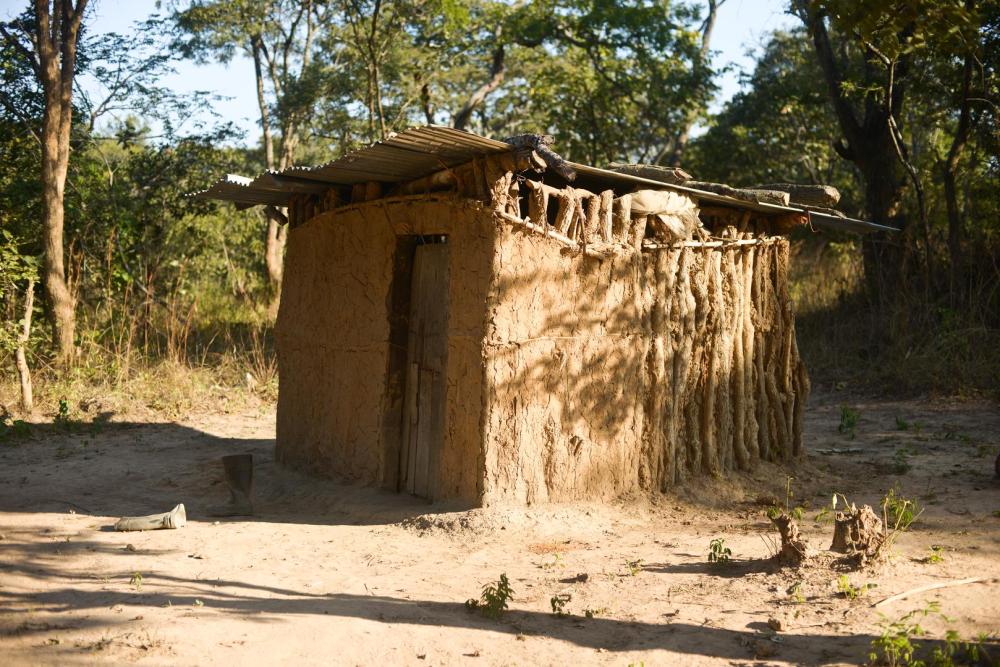

Rural residents in Serenje district have faced severe suffering over the past few years due to commercial farming. Some commercial farmers have burned or bulldozed homes, uprooted trees, and evicted residents with no compensation and no meaningful opportunity to contest their removal. Dozens of residents evicted by one commercial farmer in 2013 have spent the past four years in tents or shoddy housing in a forest area where they have little access to water, and were not given permission by local authorities to cultivate crops. At time of writing, they continued to live in deplorable conditions, hoping that the government would resettle them onto new land.

Legal Obligations

Human rights law prohibits forced evictions, and requires that governments respect, protect, and fulfill the rights to housing, health, a healthy environment, food, water, and education. It also establishes that people have the right to a remedy for rights violations. International standards establish that business enterprises, including commercial farmers, have a responsibility to identify, prevent, mitigate, and remedy human rights abuses linked to business operations. Zambia has ratified rights treaties and endorsed other relevant standards; it has no shortage of guidance on how to promote agricultural development while protecting human rights.

The Zambian government should take immediate action to safeguard the rights of rural residents in commercial farming areas. It should fully implement and ensure compliance with its policies on resettlement and compensation, including for people at risk of displacement due to commercial farming. It should work to ensure that government agencies have adequate staffing, resources, and training to enforce laws and monitor the activities of commercial farmers, and improve transparency concerning commercial agriculture. It should address policy gaps, including by adopting the long-awaited customary land administration bill and an updated national land policy. The government should also require that environmental and social impact assessments be conducted before approval is given for agricultural investments. It should effectively monitor commercial farming operations on an ongoing basis.

The Zambian government should uphold its human rights commitments by ensuring that rural residents in dire need of improved livelihoods are not left worse off by commercial agriculture.

Key Recommendations

To the Government of Zambia

- Provide immediate relief and take longer-term measures to remedy the harm suffered by rural residents of Serenje who were forcibly evicted from their homes or were displaced without adequate compensation.

- Ensure that rural residents at risk of displacement or eviction have access to affordable or free legal aid, and to remedies in subordinate courts or other judicial venues.

- Ensure that affected communities, including women on an equal basis with men, are able to meaningfully participate in any consultations concerning new or expanded commercial farming, about measures to avoid displacement, and about possible resettlement or compensation.

- Ensure that land laws, including any future law on customary land administration, clarify procedures for community consultations in the event of conversions or alienation of customary lands.

- Implement the National Resettlement Policy and Guidelines for the Compensation and Resettlement of Internally Displaced People (IDPs). Improve coordination among ministries and agencies responsible for activities related to land, agriculture, environment, and resettlement. Disseminate relevant policies and train officials on their implementation.

- Inform commercial farmers about all relevant policies and laws, including on resettlement and environmental protection, in advance of starting commercial farming activities. Enforce all statutory and regulatory requirements for environmental and social impact assessments in connection with commercial farming.

- Enhance regulation and monitoring of commercial farming, including by setting up environmental monitoring offices in all provinces and recruiting more inspectors.

- Conduct public awareness campaigns among communities that may be impacted by commercial farm development to inform them of their legal rights.

To Commercial Farmers

- Conduct environmental and social impact assessments addressing the full scope of risks from commercial farming. Make all such documentation available to the public, including women and marginalized populations, in understandable formats.

- Comply with all legal requirements to consult with, compensate, and/or resettle local residents affected by commercial farming. Ensure that women are equally included in any consultations or negotiations over compensation and resettlement.

- Ensure that individuals affected by commercial farming are able to lodge complaints directly with the commercial farming venture, including where appropriate through a formal grievance mechanism, and seek a fair resolution.

Methodology

This report is based on research conducted between June 2016 and August 2017, including field visits to Zambia in August to October 2016, and March and June 2017. It is focused on Serenje district, Central Province, because it is the site of significant government and commercial investment into large-scale agriculture and farm blocks. The report examines the human rights impacts of the activities of these commercial farms, including the distinctive impacts on women and children in the district.

Human Rights Watch researchers interviewed 132 individual community members (70 men, 58 women, as well as 2 girls, 14 and 17 years old). We conducted these interviews in four communities in Luombwa farm block, in the Milumbe, Kalengo, Chishitu, and Ntenge sections. We also interviewed residents living in Nansanga farm block and the Munte/Bwande area in Serenje district.

We met with district, provincial, and central government officials from several ministries and bodies. These included officials from Serenje District Council, Ministry of Lands and Natural Resources, Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock, Ministry of Chiefs and Traditional Affairs, Ministry of Gender, Zambia Environment Management Agency, the Office of the Vice-President’s Department of Resettlement, the Lands Tribunal, and a member of parliament representing the Serenje district. Human Rights Watch also interviewed a former official from the Zambia Development Agency (ZDA), and wrote two letters to ZDA seeking information and an interview, but received no response.

We requested interviews with representatives of six commercial farms in Serenje district. We interviewed officials from Silverlands farm in March and August 2017, and in June 2017 we met with eight commercial farmers in Serenje, a town in Serenje district. These eight farmers included representatives of three of the six commercial farms investigated in this report. We sent detailed letters to each of the six commercial farms, requesting information and sharing our findings. We received email responses from five commercial farms, and had a telephone interview with one. The responses are reflected in this report.

We interviewed independent human rights analysts, researchers, civil society organizations, activists, and lawyers working on land issues in Zambia. We met with other

informed community members, such as school headmasters, teachers, retired government officials, and agriculture extension workers in Serenje district.

Human Rights Watch conducted all interviews with community members in Bemba, a local language, with translation in English. Interviews with government officials, representatives of commercial farms, and civil society organizations were conducted in English.

We took measures to ensure that our investigation accurately reflected women’s distinctive experiences with commercial farming. Such measures included working with female interpreters, interviewing women in private spaces, meeting with women individually and in groups to explain the aims of the research, and seeking advice from experts on gender and land in Zambia.

Most interviews were conducted privately, one-on-one, in quiet places within the communities, such as under trees or behind houses. We also conducted small group interviews with fewer than 20 people to confirm events and conditions in the communities. Individual interviews lasted one to two hours.

Human Rights Watch also reviewed secondary data sources, including laws, government documents, reports from nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and research institutes, court rulings, and maps. We used satellite imagery to verify land use and community presence over the past decade.

Interviewees did not receive any compensation for participating in interviews. Respondents were informed of the purpose of the interview, its voluntary nature, and the ways in which the data would be used. They verbally consented to be interviewed. They were told they could decline to answer questions or could end the interview at any time. Where appropriate, Human Rights Watch provided contact information for organizations offering legal or other services.

We have used pseudonyms for community members we interviewed to protect their privacy. In some cases, further identifying details have been withheld to prevent possible reprisals.

For locations within farm blocks, we used names for “sections” used by local residents.

We use the terms “legitimate tenure rights” or “legitimate land tenure” in this report to refer to legally or socially recognized entitlements to access, use, and control land and related natural resources, in line with usage of this term in international guidelines on land governance and secure land tenure. Land tenure systems determine who can use land and related resources, in what way, for how long, and under what conditions. They may be established in formal laws, or recognized in customary practices.

I. Background

Commercial Agriculture in Zambia

With fluctuating and declining copper prices since 2011, the government of Zambia has intensified efforts to diversify its economy by promoting agricultural development and commercial farming.[1] Recently re-elected President Edgar Lungu and his Patriotic Front (PF) party have pledged to make agriculture the “main stay of Zambia’s economy.”[2] The government of Zambia has increased the proportion of the national budget dedicated to agricultural development,[3] and its national development plan includes foreign direct investment in agriculture as a primary objective.[4] Zambia is also committed to implementing the Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme (CAADP), Africa’s policy framework for agricultural development.[5]

There is no reliable data on exactly how much land has been leased or is being developed for commercial farming in Zambia. The government has no comprehensive or disaggregated database on large farms in the country. According to the Land Matrix, a global land monitoring initiative, the pace of large-scale land acquisitions in Zambia has increased since 2011.[6] The 2016 Land Matrix summary on Zambia highlights 34 land deals involving investors from 14 countries, with more than 390,074 hectares of land under contract.[7]

For more than a decade, the Zambian government has promoted its Farm Block Development Program (FBDP) as the centerpiece of its effort to promote agricultural growth. It says it has converted large swaths of land, or “farm blocks,” in each of the 10 provinces into leasehold land available for commercial farmers.[8] Each farm block is supposed to have one core large-scale farm (core venture) of 10,000 hectares; one to three commercial farms (1,000-5,000 hectares); medium-scale farms (100-1,000 hectares); emergent farmers (50-100 hectares); and small-scale farmers (25-50 hectares). Crops grown in core venture farms are meant to be predominantly for export. The smaller farms have the option of working in out-grower arrangements with the core venture or using common processing facilities.

For each farm block, the government has promised to provide basic infrastructure for agriculture, such as feeder roads, electricity, dams for irrigation, and communication facilities.[9] While government officials told Human Rights Watch that agencies have completed conversion of customary land to leasehold tenure under state control in the FBDP areas,[10] the government is far from completing the infrastructure or securing the major investors.[11]

The government’s Second National Agricultural Development Plan, issued in 2016, reiterates that the FBDP remains a priority.[12] The ruling party promised in its 2016 manifesto to “continue and expand programing of opening up more agricultural land,” using the farm block model.[13]

Rural Poverty and the “Panacea” of Agricultural Development

The Zambian ruling party’s manifesto says that agriculture is a “panacea” for rural poverty in Zambia. The government’s 2016 Second National Agriculture Policy, which promotes agriculture as a business, also aims for agricultural development to aid food and nutrition security, employment creation, increase incomes, and reduce rural poverty.[14] Its 2017 Seventh National Development Plan has a major focus on achieving a diversified and export-oriented agricultural sector in the period 2017-2021.[15]

This may be a noble idea, but after more than a decade of programs and policies to promote commercial agriculture, many promised benefits for rural Zambians have not yet materialized. The government’s agriculture policy notes that performance of the agriculture sector “has not been sufficient enough to make a significant dent on poverty.”[16] It also notes, “growth and gains made within the agriculture sector have not been inclusive but rather limited to large scale and medium scale or emergent farmers with little impact on the bulk of small scale farmers.”[17]

Zambia’s economy is growing, but poverty rates, especially in rural areas, have remained high.[18] The government’s 2015 Living Conditions Monitoring Survey found that 54.4 percent of the population lives below the national poverty line. Poverty is higher in rural areas (76.6 percent) than in urban areas (23.4 percent).[19]

World Bank documents project a growth rate of 4.1 percent in 2017, but said these economic gains might not be inclusive of rural populations.[20] According to one World Bank document, “coverage of programs targeted to help the poor and vulnerable [in Zambia] remain small relative to the need, as well as compared to regional and international standards.”[21]

Villages Throughout “Available” Land

Many rural areas in Zambia are sparsely populated, but not vacant. Zambia has a rural population of close to 10 million people, or almost 60 percent of its population.[22] Rural communities in Zambia tend to live in dispersed settlements, with distinct kin-villages separated by “bush” for grazing and cultivating crops.[23] Many rural residents live on roughly the same lands as relatives going back generations, and often consider it their ancestral land. Some practice shifting agriculture (rotational farming where land is cleared, cultivated and then left to regenerate for a few years), and use surrounding areas for foraging in forests and grassland, tending livestock, and fishing. Rural settlements are often adjacent to water sources.[24]

Government officials and official documents sometimes exaggerate the extent to which rural land is available, idle, and ready for use by commercial agricultural investors.[25] Traditional chiefs have claimed that some occupied lands are vacant as they negotiate land conversions.[26] The Deputy Director of the Ministry of Chiefs and Traditional Affairs told Human Rights Watch, “You would be amazed how it is done in some areas. I have gone to areas where there are lots of people living but the chief has said there are none! But we cannot visit every site.”[27]

Government and Customary Land Governance

As in some other African countries, all land in Zambia is vested in the president.[28] However, the constitution and laws of Zambia protect property rights and recognize both customary areas and “state” land that can be alienated by lease (and is then considered land under “leasehold” tenure).[29]

Customary areas, commonly referred to as customary land, are administered by traditional authorities. The Lands Act provides that land held under customary tenure cannot be alienated by the president without taking into consideration local customary law, consulting with the chief and local authority in the area, and consulting with “any other person or body whose interest might be affected.”[30] As of 1987, the government said that 94 percent of land in Zambia was customary land.[31] Experts have disputed this estimate, claiming that approximately 51–54 percent of land remains under customary tenure.[32] The Ministry of Lands is currently undertaking a land audit to establish how much land is customary and how much is state land.

The government can grant the right to use and benefit from state land to individuals or corporate entities, with leases of up to 99 years.[33] The Lands Act establishes consultative processes through which land can be converted from customary and placed under state authority. Once land is converted, there is no provision to convert it back. Chiefs should consult with and gain consent of local communities before agreeing to convert customary land, but as explained in the following sections, this does not always happen, and even if it does, women may be excluded from the consultations.[34] Some officials said that chiefs stand to benefit from land conversions and may be motivated by greed to avoid community consultations.

The government may also acquire land from current users when it deems it to be in the national interest.[35] A law on compulsory acquisition of land provides procedures for notice, valuation, and compensation to users before acquisition, and recourse after land is transferred.[36]

Even where agricultural land has been converted from having the status of customary areas to state leasehold land, customary laws and practices of communities on the land are still influential. Traditional chiefs continue to play a role in land matters, including in some cases designating alternative land for individuals evicted from land to make way for commercial farming. The customary practices of some communities give men greater authority over land, and women may have little say about securing alternative land when they face displacement.[37]

The government and other stakeholders have been discussing law and policy reforms that could clarify and improve protections for land governance and administration, including a customary lands administration bill and an updated national land policy.

II. Commercial Farming in Serenje District

Where will we go looking for land? There isn’t any land left. Over here [Luombwa] they [officials] say all the land belongs to the white farmers, and on the other side, they’ve created Nansanga Farm Block.

-Elisabeth K., 24-year-old mother of four, Ntenge Section, September 2016

Zambia’s Central Province is well known for fertile soil and numerous water sources. It is a burgeoning commercial farming hub. Farms in the province produced an estimated 723,760 metric tons (MT) of maize in 2014, along with substantial amounts of wheat (99,758 MT) and soya beans (96,518 MT).[38] Agriculture in the province is mainly rain-fed, though large farms—with government support—are increasingly moving toward irrigation. The province has a number of farm blocks, both within the government’s Farm Block Development Program and independent of that program.

This report focuses on commercial farming in Serenje district, Central Province. The district provides a valuable case study in several respects. It illustrates the tensions and confusion over customary land conversions and the rights of rural residents with long-standing ties to the land. The commercial farms examined also reveal the negative impacts of large-scale commercial agriculture on rural communities when operators do not comply with laws and the ventures lack proper government oversight.

Serenje district has a high concentration of commercial farms, owned both by foreign and domestic investors. Over the past decade, the government has been piloting its Farm Block Development Program (FBDP) with the Nansanga farm block in this district. The government has also facilitated commercial agricultural investments in other farm blocks in the district independent of the FBDP, including the Luombwa farm block. The government has promised, and to some degree has undertaken, infrastructure development to help commercial farming in the district, building access roads and bridges, installing electric lines, and constructing dams for irrigation.

As a long-planned, concerted test case for the government’s plans for commercial agriculture and farm blocks, Serenje district should represent a best-case scenario. It should be a place where the government demonstrates that its policies in support of commercial agriculture are compatible with the rights of rural people, and truly provide them with real benefits. Unfortunately, as the next sections show, the Serenje experiment is to a large extent failing local communities.

Land Conversions in Serenje District

Agricultural land in Serenje district is a mix of customary and state land. The history of the conversion of land from customary to state status in this district is murky and contested. Government officials say that the conversions of customary land to state land starting in the 1980s were legitimate, though it is virtually impossible to verify that official requirements were met since documentation is not available or accessible.[39] According to a Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock official, “chiefs gave land willingly” for the farm blocks in Serenje district, and the government did not acquire it through the compulsory land acquisition law.[40]

There are conflicting accounts on whether there were residents on the land prior to conversion. Several government officials acknowledge that land now used, or soon to be used, for commercial farming in Serenje was not vacant when it was converted, or when commercial farmers started operations. A Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock (MAL) official admitted that there is “no way a huge tract of land would not have villagers on it, and so there was a duty to consult with the residents whose interests might be affected.”[41] Other government officials disagree, claiming that if there were people living or farming on the land when it was converted, the government would have resettled them, but said they had no evidence to back such claims. A provincial land surveyor told Human Rights Watch that all people living on land converted into farm blocks in Serenje would have been resettled, despite the absence of records to confirm this, and anyone now living on the land must be “squatters” and due no recourse.[42]

Many long-term rural residents in Serenje district say they were unaware that the land had been converted until commercial farmers started arriving. Many whose families lived in the area for decades or more told Human Rights Watch that no one discussed the conversion with their families, adding that they had no information about what conversion means.

There are also conflicting accounts on the issue of approval by traditional leaders for conversion of land. The farm blocks in Serenje were, or in the view of some, still are within the Muchinda chiefdom. The area’s chief died in 2010, and there was a contest over who would be appointed the new Senior Chief Muchinda of the Lala people.[43] In 2016, a court appointed Evans Mukosha as successor to the throne. In September 2016, Mukosha and his representatives told Human Rights Watch that they believe the prior Chief Muchinda did not understand that chiefdom land was being permanently converted to state land to be used in farm blocks. Instead, they said he appeared to think it was a temporary lease, and that the land would remain under the control of the chiefdom. They did not have specific information about whether the chief was compensated, what documentation was signed, or whether there were consultations between the chief and the local people. Mukosha said the government promised the prior chief a tractor, a promise that was never honored.[44] Mukosha was murdered in May 2017, and no successor had been appointed at time of writing.

Some civil society groups and public interest lawyers have asserted that the land conversions were not done in accordance with law, and thus are invalid. They point to the lack of evidence that legal procedures were followed, including with respect to consulting with and compensating residents. [45]

Human Rights Watch could not verify whether the land conversions complied with law or not, but the fact is that vast areas of land in Serenje are now being commercially farmed. The commercial farmers feel confident that they have, or will soon have, government authorization to farm there. Many residents told us that they were caught unawares by the land conversion, and at a loss for how to cope with losing land they and their relatives have cultivated for years, or in some cases, for generations.

Major Farm Blocks and Commercial Farms in Serenje District

Serenje district has five major farm blocks: Nansanga, Luombwa, Munte, Kasanka, and Ssasa. Other commercial farms in the district also benefit from the government’s infrastructure investments, but are outside the bounds of the farm blocks.

This section describes six commercial farms in or near the Nansanga and Luombwa farm blocks, providing background on the farms and current activities. Chapters III (Evictions and Resettlement in Serenje District) and IV (The Human Costs of Commercial Farming in Serenje) describe the experience of residents affected by these commercial farms.

Nansanga and Luombwa Farm Blocks

The two most prominent farm blocks in Serenje district are Nansanga, which is part of the government’s Farm Block Development Program, and Luombwa, which has the largest area under cultivation by commercial farmers.

Nansanga farm block is located 60 kilometers south of Serenje (district’s administrative hub). It covers approximately 100,000 hectares of land, equivalent to about 122 soccer pitches. As noted above, the government’s aim is for it to have a “core venture” farm of 10,000 hectares, several large commercial farms, and many medium, emergent, and small farms.

While the government has made progress on infrastructure to serve this farm block, including access roads and bridges, electric lines and a power substation, and dams for irrigation, it has struggled to secure a foreign investor for the Nansanga “core venture.” Instead, in 2015 it designated a quasi-governmental company, the Industrial Development Corporation (IDC), as the core venture. As of July 2017, IDC was soliciting bids from agribusinesses and might parcel up the 10,000 hectares.[46] There are small and medium farms operating in Nansanga, but not on the scale that the government hoped for. In the coming years, it is likely that larger commercial farms will take up operations within Nansanga.[47]

There is conflicting information about how many people currently live on this land, or were present at various points in the past. A 2009 government document said 427 households were living within the Nansanga area after the land was converted from customary to state land.[48] A Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock official said that in 2002 there were 32 families needing relocation in the core venture area, and a 2014 government survey showed there were 100 families living there.[49] Meanwhile, local residents told Human Rights Watch they believed there were far more families living in the core venture parcel and the larger Nansanga land area, though they could not give a concrete estimate.[50]

Luombwa Farm Block is about 70 kilometers west of Serenje, bordered by the Nansanga Farm Block and Musangashi Forest Reserve. Human Rights Watch could not verify the total area of Luombwa farm block because this information was not available from government authorities. It is the most advanced farm block in the district in terms of infrastructure, with an electricity sub-station, some telephone network, gravel roads, and bridges.

Zambian officials say the state acquired the Luombwa farm block from a farm development program in the 1990s.[51] The government demarcated the outer boundary in the mid-1990s, then designated parcels for individual farm plots. The Ministry of Lands issued title documents to commercial farmers for some of these plots. In some cases, farmers never started operations, and the government repossessed and reallocated the land. [52] Over time, new investors and farmers have come to Luombwa to take up commercial farming, sometimes obtaining land from the government and sometimes purchasing leasehold tenure rights from other private parties.

As far as Human Rights Watch could ascertain, there is no final Strategic Environment Assessment (SEA) for either the Nansanga[53] or Luombwa farm block as a whole (although there are environmental impact assessments (EIAs) for some activities on some farms within the blocks).[54] As described below, these assessments are important safeguards for sustainable environmental management and to mitigate adverse impacts.

Commercial Farms Operating in Serenje: Six Case Studies

Human Rights Watch investigated six commercial farms in Serenje district, ranging in size from 150 hectares to more than 5,000 hectares of land. Five of the farms are within Luombwa farm block and one is in the Nansanga farm block. These farms cover a broad spectrum from a corporate investor (Silverlands Zambia Limited) to family-run farms, registered as companies with the government, whose owners live on the farm and directly participate in the work.

The farm and section (location) names below reflect how local residents refer to the farms, often using names or nicknames of farmers rather than business names. In many cases, residents simply referred to farm owners or operators as “Muzungu” (white) farmers. According to residents, all commercial farmers in these case studies were white. Human Rights Watch was not able to confirm the nationality of all the farmers, but the five farms it could verify have owners from South Africa, Zimbabwe, the United Kingdom, and Brazil.[55]

The summaries below refer to numbers of residents (sometimes referred to as “settlers”) on land acquired by commercial farms, primarily based on estimates in public documents or from government officials. In all cases, local residents told Human Rights Watch that there were more people living on the land than reflected in government or company documents.

| Company name and informal designation |

Known owners, and nationality according to government registry |

Farm block |

Farm area (hectares) |

Project stage |

Environmental and social impact assessments |

|

Silverlands Zambia Limited (SZL) Known as “Silverlands” in community |

Majority owner: Silverlands Ireland Holdings (Z) Limited (99% equity) |

Luombwa |

5,506 hectares |

Incorporated in Zambia August 2012. Cleared land and cultivating soya, wheat, and maize. |

Submitted two Environmental and Social Impact Assessments (ESIAs) to Zambia Environmental Management Agency (ZEMA), and received approval March 2015 and August 2015. |

|

Rowe Farming Limited Known as “Matthew’s Farm” in community |

Matthew John Rowe (Zimbabwe) Kyrie Pauline Visser Rowe (Zimbabwe) Felicity Rose Ferriman (United Kingdom) |

Luombwa |

117.8 hectares |

Incorporated in Zambia April 2014. Cleared land and began cultivation of soya. |

According to ZEMA officials, Rowe submitted an Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) for installing a water pump, but not for clearing land or other farm operations. |

|

Nyamanza Farming Limited Known as “Sawyer farm” in community |

John Lewis Sawyer (Zimbabwe) Jason Lewis Sawyer (South Africa) Leonard David Van Brenda (Zimbabwe) |

Luombwa |

996 hectares |

Incorporated in Zambia June 2007. Cleared land and cultivating soya, wheat, and rice. |

According to ZEMA officials, no Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA). |

|

Billis Farm Limited Known as “Billis farm” in community |

Abraheam Lodewikus Viljoen (Zimbabwe) Paulo Stavrou Billi (Brazil) Alexandre Stavrou Billi (Brazil) Idaro Ventures Limited |

Luombwa |

2071.4 hectares |

Incorporated in Zambia December 2011. Cleared land and cultivating soya, wheat, and maize. |

According to ZEMA officials, no Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA). |

|

Kasary Kuti Ranch Known as “Jackman’s farm” in community |

Philip Jan Jackman (United Kingdom/Zambia) |

Luombwa |

263.7 hectares |

Incorporated in Zambia in June 2014. Has not cleared land. |

According to ZEMA officials, no ESIA. |

|

Fairfield Farm Known as “Badcock’s farm” in community |

Jeremy Badcock (Not verified) Greg Badcock (Not verified) |

Nansanga |

2,202.3 hectares |

Incorporation information not available for this farm. Has cleared land to make roads. |

According to ZEMA officials, no ESIA. |

Sources: The information for this chart was assembled from a variety of public and private documents and interviews. We were not able to get confirmation from the companies for all data in this chart. The sources included documents from international financial institutions, Zambian ministries and agencies (including the Ministry of Lands, the Ministry of Commerce, Trade and Industry, court decisions, emails from and interviews with commercial farmers, interviews with district, provincial, and central government officials, and interviews with several traditional leaders. The text of this and the following chapters includes footnotes with exact sources.

“Silverlands Farm”

Silverlands Zambia Limited (SZL) is owned by SilverStreet Private Equity Strategies SICAR—Silverlands Fund through its subsidiary Silverlands Ireland Holdings (Z) Limited.[56] SZL is incorporated in Zambia, and Silverlands Fund is incorporated in the United Kingdom. Silverlands Fund secured roughly US$150 million in financing from the United States government’s Overseas Private Investment Cooperation (OPIC) in 2011.[57] SZL registered as a Zambian company in 2012, and commenced operations in 2014 in Luombwa farm block. In 2017, it received reinsurance of $10.1 million from OPIC, [58] and $15.2 million from the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA), a member of the World Bank Group.[59]

Silverlands acquired four neighboring farms, known as Vundu, Venturas, Sichilima, and Green Forestry Development/GFD (Sheriff) farms, from individual private owners in Luombwa Farm Block. It consolidated these farms into a single large farm (5,506 hectares), where it grows food crops (maize, soya, wheat, and potatoes) and livestock (cattle).[60]

Two environmental and social impact assessments (ESIAs) were prepared for the Silverlands farm, which the government approved in 2015.[61] One covers the project on the land formerly known as the Vundu, Venturas, and Sichilima farms and the other covers the change from forestry to row cropping on the former Green Forestry Development land.[62]

One of the ESIAs stated that 14 households[63] were living on the land, and one other document said that four gravesites on the land would not be disturbed.[64] As of February 2017, one family had been resettled. In June 2017, after several years of seeking alternative land to resettle residents living on the farm, the company’s board decided that the residents would not be resettled, and instead the company would adopt a livelihood restoration plan for residents, who would be able to remain in their homes on the farm block.[65]

“Matthew’s Farm”

A farm operated by Rowe Farming Limited, commonly referred to as “Matthew’s Farm” by local residents, is located in the Chishitu section of Luombwa Farm Block. The company was officially registered in April 2014.[66] The owner, Matthew John Rowe, started the process to acquire a certificate of title for 118 hectares of state land from the Commissioner of Lands in 2016 by paying a plot premium of 17,500 Zambian Kwacha (US$1,897) and land application fee of 250 Kwacha ($27).[67]

According to Zambia Environmental Management Agency (ZEMA) officials, the company submitted an environmental impact assessment (EIA) to the government to install a water pump, but not about clearing the land or undertaking commercial farming.[68] Nonetheless, as of October 2016, Rowe had already started clearing the land, and planned to cultivate.

In terms of residents on the land, the 2016 District Council offer letter states that Rowe Farming Limited had to submit a resettlement plan for five “settlers” on the farm.[69]

“Sawyer Farm”

The farm run by Nyamanza Farming Limited, called “Sawyer Farm” by locals, falls within Kalengo and Chishitu sections of Luombwa Farm Block.[70] John (father) and Jason (son) Sawyer own the company.[71] The owners registered the farm in 2007, and sought to acquire land starting in 2014. In 2015 the company asked the District Council to re-plan 1,000 hectares of a farm into smaller parcels,[72] then asked to reduce the farm to 996 hectares[73] to enable them to process title deeds. The council granted the request in September 2015.[74]

ZEMA officials told Human Rights Watch that they had no EIA on file for “Sawyer Farm.”[75]

There is conflicting information in government documents about whether there are currently residents on the farm. One government document from October 2015[76] reported that there were no settlements, but at least two government documents Human Rights Watch viewed recognized that at least five families resided there.[77] Residents told Human Rights Watch that at least 21 villages, with about 45 families, lived on the land.[78]

“Billis Farm”

Billis Farm Limited is in the Milumbe area of Luombwa Farm Block, near the Mulembo River.[79] It appears to be co-owned by three foreign nationals.[80] They registered the company in 2011, and purchased the farm from another private corporation in 2012.[81] The farm covers 2,071 hectares.[82]

ZEMA officials told Human Rights Watch that they had no EIA on file for “Billis Farm.”[83]

Human Rights Watch did not find any government records of the number of families living on this land before Billis Farm Ltd. acquired farm. However, Human Rights Watch interviewed families displaced by the owners of this commercial farm who said that at least 11 villages and some 65 or more people had been on the land before the company evicted them in 2013.

“Jackman Farm”

Kasary Kuti Ranch, known as “Jackman Farm” after its owner, Philip Jan Jackman, is a 264-hectare farm in the Ntenge section of Luombwa farm block.[84] The Serenje District Council approved Jackman’s farm application in 2014,[85] and the Ministry of Lands issued an offer letter on May 5, 2015.[86] The Ministry of Lands issued a certificate of title to the owner in May 2016.[87] A ZEMA official told Human Rights Watch that there is no environmental impact assessment on file with the agency.[88]

Human Rights Watch could not find any official documents indicating how many people resided on this farm when Jackman started the acquisition process. But on May 6, 2015, Jackman submitted a handwritten note to the District Council asking, “can you advise when the squatters will move from the farm as I have the ‘offer letter’ from Ministry of Lands.”[89] This establishes that Jackman knew that the property was not vacant, and that he considered that the people residing there had no legal right to remain. District officials said that Jackman did not submit a resettlement action plan.[90] As described in the following chapter, Jackman applied to the Serenje district subordinate court to get an eviction order against the residents, which was granted in 2015. Residents appealed the decision.

“Badcock Farm”

Fairfields Farm, as its owner Jeremy Badcock calls it, falls within the Bwande section of Serenje district, in the eastern part of the Nansanga farm block. Local residents refer to it as “Badcock farm.”[91] Badcock purchased the land from a private owner, a member of the traditional council for the area.[92]

A ZEMA official told Human Rights Watch that the agency has no EIA on file for Fairfield farms.[93]

Human Rights Watch is not aware of any government document indicating the number of residents on this land. Badcock admitted to Human Rights Watch via email that there were “a few families living on the farm. Five families at the time of purchase.”[94] According to a traditional authority for the area, 22 families were living on the land as of 2016.[95] At time of writing, Badcock had not submitted a resettlement action plan to Serenje district council or the Department of Resettlement. He told Human Rights Watch that he believes the prior owner is responsible to relocate and reimburse the families.[96]

III. Evictions and Resettlements in Serenje District

There are lots of promises by the government. They used to tell us, “These people [farmers] are coming. It will be great for you.” But the farms are white elephants.… People are not happy about how things have gone on. They feel they have been cheated…. The rich are getting more land. The poor get nothing.

-Allan C., school official, Serenje district, September 2016

In Serenje district, long-term residents have been evicted, sometimes forcibly, or fear displacement from land to make way for commercial farmers. This has often had a devastating impact on the community members, with distinctive impacts on women due to their social roles and status. Local residents and advocates told Human Rights Watch that hundreds of individuals have already been forced out of their homes and lands due to commercial farming in the district. Several thousand more may be at risk of being pushed out of their homes without compensation and into deeply precarious situations as the government pursues further agricultural development.[97]

|

Forced Evictions from “Billis Farm” Billis Farm Limited is co-owned by three foreign nationals and a corporate interest.[98] They purchased the 2,071-hectares farm from another private corporation in 2012.[99] Abraheam Lodewikus Viljoen, one of the owners, lives and works on the farm with his family. Families told Human Rights Watch that they were forcibly evicted by employees of this farm and that that at least 11 villages and more than 65 people had been on the land before the company evicted them in 2013. Residents said Viljoen, an owner of “Billis farm”, told them to leave, but there was no meaningful consultation, formal notification, compensation, provision of alternative housing, or chance to seek a legal remedy. Residents told Human Rights Watch that employees of “Billis farm” told them they had two weeks to move out of the land. They said that on June 4, 2013, Viljoen and his workers arrived with bulldozers and demolished residents’ homes, leaving residents to hurriedly grab their belongings.[100] One of the evicted residents, Mody C., described the scene: “He [Viljoen] came with two bulldozers with long chains tied to each other … which had started pulling down trees, houses, and everything along [the] way.”[101] Viljoen told Human Rights Watch by phone that he had indeed displaced families in June 2013, but disputed that he used force to get residents to move. He stated that he told the families in January 2013 that they had six months to uproot their crops and move, acknowledging that his workers used two bulldozers with a chain to clear the land, and that stumping and razing the land started in June 2013. He mentioned that when “chaining” started in June, “stragglers” took him seriously, moving off the farm quickly. He started tearing down residents’ buildings in June and got to their crop fields in August.[102] Some residents said Viljoen ordered his workers to transport them in a tractor off of the farm. The workers left the residents by the roadside some distance away. These families lived out in the open with no shelter during the coldest months (June-August) of the year. The government’s Disaster Management and Mitigation Unit provided them with tents and some food assistance. They have spent the past four years in these tents or shoddy housing (using rudimentary materials such as plastic or fertilizer bags, sticks and mud) in a forest area where they have little access to water, and are not supposed to cultivate crops. At time of writing, they continued to live in deplorable conditions, hoping the government would resettle them onto new land. ZEMA officials told Human Rights Watch that they had no environmental impact assessment on file for “Billis Farm.”[103] Viljoen admitted that his farm had no such assessment, and believed this was a new requirement. He blamed government bodies for poor guidance. “Government should make farmers aware on what is required…. ZDA should inform every investor that they need an EIA if planning to clear more than 50 hectares,” he said. [104] |

Disregard for Long-Term Land Use and Historic Ties

Where will we go? This is where I was born, my parents were born here and died here. Where can we go? I have ten children and my sister has six, where do I take them if they remove me from this farm?

-Melanie M., Chishitu section, September 20, 2016

Human Rights Watch interviewed many rural residents of Serenje district who said they were baffled at being stripped of their land, which they had occupied and farmed for generations, with no consultation, compensation, or decent alternatives when commercial farmers arrived. Only a handful of the 132 residents Human Rights Watch interviewed in Serenje who had been displaced or were threatened with displacement experienced the kind of meaningful consultations that Zambian law requires with chiefs, company representatives, or government officials.[105]

Many rural residents in Serenje said this was their ancestral land going back many generations, and others say it had been family farmland for decades, allocated to them by past chiefs. For example, John M., 61, said:

We used to be in Munte Farm Block area and they [officials] displaced us, and that’s how we came here [Chishitu area, or “Matthew’s farm”]. When we came here the chief gave us land in 1996. I’ve farmed so much—beans, cassava, and sweet potatoes. It isn’t time to harvest the latest crop yet and we’ve been told to vacate. What about everything I’ve planted? …We have not been shown any alternative site. We were told to go look for another place to live ourselves. We will lose everything we have.[106]

Esther M., a 50-year-old mother of nine children, said she has lived in Kalengo section (now called “Sawyer farm”) before 1984. “My parents came and settled here…. I was about 18 years old then. I remember my age because I used to fall sick often those days and they used to take me to the clinic. And in the clinic they used to ask me my age.”[107]

Gerard M., a father of six children, told Human Rights Watch he had lived on the land now claimed by commercial farmer Philip Jan Jackman his entire lifetime: “My parents were from here [Muchinda chiefdom], my father lived here. I was born here in 1964.”[108]

It is extremely uncommon for rural residents in Zambia, including Serenje district, to hold formal land title. Zambia’s policies recognize that it is unreasonable to expect that rural residents in this context would have the financial means or knowledge to formalize customary land use rights and obtain a title. The National Resettlement Policy recognizes this, and applies to people holding land under customary or other recognized tenure systems (not only individuals holding title to state land).[109]

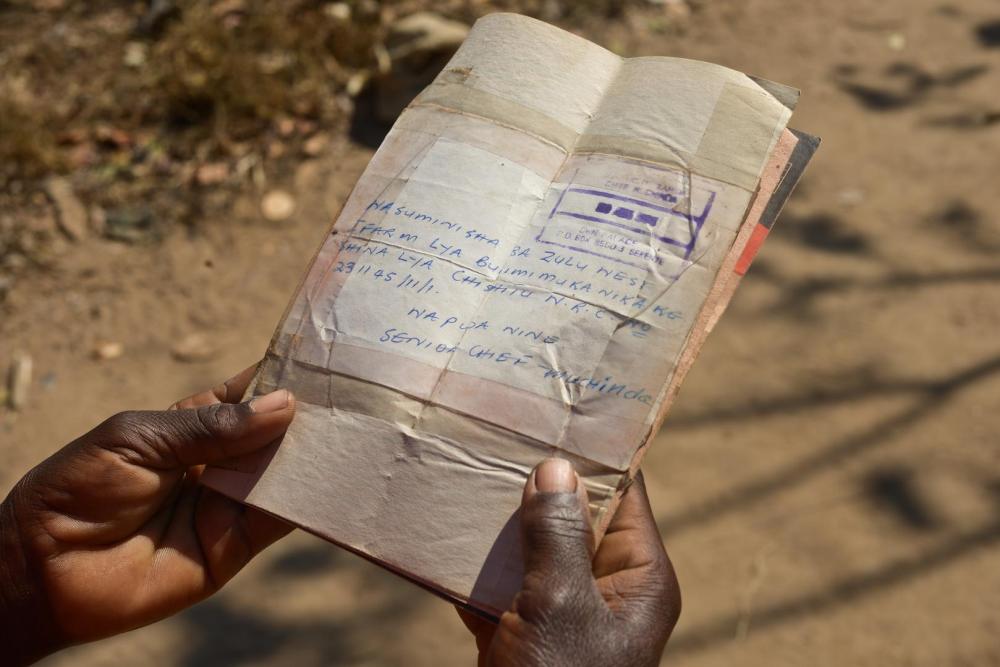

That said, many people do have some degree of evidence of long-term land use, such as farming permits issued by the chief. But the judiciary and other Zambian authorities pay little regard to such documents. The Serenje District Commissioner emphasized that farm permits issued by the chief “are not the same as title.”[110] He noted that the permits are temporary and can be withdrawn.[111]

One group of families tried to defend their land use rights in court when the owner of Jackman farm sued them (see section on evictions below). The families submitted to the court land occupancy documents issued by Senior Chief Muchinda. The judge found in favor of the commercial farmer, and ordered that “the squatters” be evicted and compensated 1,000 Kwacha (US$100) per family.[112]

Two residents told Human Rights Watch that commercial farmer Jason Sawyer told them he would not compensate or resettle them because they did not “pay anything to council [property tax],” and had “no title deed.”[113]

District council and provincial officials claim that people residing on land allocated to commercial farmers must have, at some point, knowingly moved onto the land unlawfully. One said, “even if they have been there for ten years, they knew they were squatters.”[114] An official in Kabwe blithely asserted that every last person on the land is a “squatter” who arrived recently.[115] The use of the term “squatter” has become commonplace in referring to residents on land who have no formal, documented legal title to it. But the use of the term in this situation is deeply misleading, and ignores legitimate tenure rights of long-term rural residents. In fact, government has no systematic process for identifying who has been on what land and for how long.

Many of the people displaced or impacted by commercial farming have real, deep ties to their homes and land and a legitimate expectation of secure land tenure rights; they are not mere squatters. Many have lived on and used the land for generations without any formal title, though many have documentation that reflects their occupancy and use.

The Ministry of Lands’ Chief Lands Officer acknowledged that the situation in Serenje has been handled poorly, saying, “Even after land has been converted and leased… government has to ensure that there are no people before re-assigning these parcels.”[116]

Lack of Compensation and Inadequate Resettlement

We were brought near here, there was nothing here, it was just a bush, they just left us here.

—Evelyn K., a 59-year-old widow, Kasenga, June 2016

Most Serenje residents Human Rights Watch interviewed received little or no compensation for their losses when displaced by commercial farmers.

Protections on Paper for Displaced Persons

On paper, Zambia has some protections against displacement, and safeguards for those who are unavoidably displaced. The 2015 National Resettlement Policy (NRP) affirms that investors are responsible for resettlement and compensation of displaced persons, including those displaced by “investment development.”[117] Zambia’s 2013 Guidelines for the Compensation and Resettlement of Internally Displaced Persons (Compensation Guidelines), which apply to people “displaced due to investment or development projects,” confirm that “the absence of a formal legal title to land by some affected groups shall not be a hindrance to compensation.”[118]

The process of determining whether individuals have legitimate tenure rights to the land they live on and to what extent is inherently complex. The strength of ties and of rights claims to the land varies from one person to another. For many, this is the only home they have ever known, while others may put down stakes just before a commercial farmer starts operations. The NRP provides that a “promoter/investor” planning to displace residents should have a cut-off date by which they should identify and record residents and assets affected by the project for resettlement or compensation,[119] and a “resettlement committee” consisting of government agencies and traditional leaders are supposed to verify displaced persons to be resettled.[120] In Serenje, government officials and most commercial farmers did not systematically document who the residents were and what tenure rights they had, nor conduct an asset inventory prior to commencing operations.

The NRP recognizes development-induced displacement and protects persons or households adversely affected by acquisition of assets or change in use of land due to an investment project.[121] The NRP establishes that compensation in cases of involuntary resettlement must take place before the onset of the project. Compensation for assets or resources that are acquired or affected should be based on the market or replacement cost, whichever is higher, including transaction costs.[122] It also says that resettlement as a result of investment projects “should be conceived as an opportunity for improving the livelihoods of the affected people and undertaken accordingly by the investor.” It requires that the investor, in consultation with the government, engage with affected communities through a process of informed consultation and participation, and that it disclose pertinent information in suitable languages. Resettlement must be to a site that the individuals or communities can legally occupy.[123]

|

Zambia’s National Resettlement Policy (2015)

|

The Reality of Displacement in Serenje

The reality for families displaced by commercial agriculture in Serenje, or facing imminent displacement, looks nothing like what is stated in policies on displacement and resettlement. Human Rights Watch interviewed dozens of residents about their experience of displacement. Virtually none of them knew that the government had policies on displacement and resettlement, and none had experienced protections anything like what the National Resettlement Policy or Compensation Guidelines call for. In most cases, the farmers had offered only pa"ltr"y sums, if anything, to get residents off the land.

|

Company name and informal designation |

Estimated number of families displaced or at risk of displacement |

Resettlement and compensation, if any |

Property destruction, other problems |

|

Silverlands Zambia Limited (SZL) Known as “Silverlands” in community |

One family resettled. |

One family (grandparents, 6 children, 14 grandchildren) resettled in 2015. In June 2017 the company decided to halt resettlement plans for remaining families, and instead to develop a livelihood restoration plan. |

No property destruction. |

|

Rowe Farming Limited Known as “Matthew’s Farm” in community |

Some 24 families at risk. Some displaced in 2016. |

Compensated five families between 5,575 Kwacha (US$618) and 7,575 Kwacha ($840).[124] |

Destroyed homes, trees, and other property of residents. |

|

Nyamanza Farming Limited Known as “Sawyer farm” in community |

Forcibly evicted approximately 45 families in 2015 and 2016. |

No compensation or resettlement assistance. |

Destroyed homes, trees, livestock, crops and other property of residents. |

|

Billis Farm Limited Known as “Billis farm” in community |

Forcibly evicted 46 families in 2013. |

No compensation or resettlement assistance. |

Destroyed homes, trees, crops and other property of residents. |

|

Kasary Kuti Ranch Known as “Jackman’s farm” in community |

Some 12 families affected by court-ordered eviction; most remain on the land and have appealed. |

Court ordered compensation of 1,000 Kwacha. |

Several arrests of residents, resulting in prison terms of three to four months for criminal trespass. Threatened to destroy homes, trees, and other property of residents. |

|

Fairfield Farm Known as “Badcock’s farm” in community |

22 families at risk of displacement. |

No compensation or resettlement as of June 2017. |

Threatened to destroy homes, trees, and other property of residents. |

Some residents said that commercial farmers made no effort to discuss resettlement or compensation. Instead, several farmers started destroying crops and trees, threatening to report residents for criminal trespass. Esther M. told Human Rights Watch:

Sawyer [commercial farmer] started causing fights. [He] started uprooting trees wherever there were settlements. And he would uproot even the ones near our homes. We lost all our fruit trees—mulberry, mango, guavas, bananas. We used to have 25 mango trees, 13 guava trees, and 5 mulberry trees. I used to even sell that fruit. My husband went to the white farmer [Sawyer] and asked for compensation. He refused, saying they bought it from the government. What could we do?[125]

In one case government officials discouraged a commercial farmer from participating in a meeting with officials and residents facing displacement. Court documents show that the Council secretary told Philip Jan Jackman not to attend such a meeting, but rather to “leave everything in the hands of the council and district commissioner.”[126]

Residents said that government officials sometimes made vague promises about compensation they could expect from commercial farmers, but then did next to nothing to help displaced residents. Esther M. said that in November 2015 District Council officials directed her husband to talk with the Sawyers, and he had asked for 19,000 Kwacha ($1,900) as compensation. “The council people said we should wait for Sawyer to give us money before we move,” she said. She said that a year later, the commercial farmers threatened them, saying they had to move. She and others said that the farmers had offered them a pittance—1,000 Kwacha ($100) per family—to leave the land. They refused the offer.[127]

In response to Human Rights Watch inquiries about these findings, Jason Sawyer said that at no time did they ask residents to vacate, offer them money, or harass them to get them to leave. Rather, the representative said that residents moved on their own when hired laborers started clearing the land.[128]

In Chishitu section (“Matthew’s farm”), 61-year-old John M., had a similar story:

Sometime in December last year [2015], Matthew and four others from the [District] Council came to my house and said this area is for the white farmer. They [officials] said, “He [white farmer] bought this land and it’s his to farm. You have to negotiate with him. Don’t cause any confusion when he comes here to start his work. He will compensate you when he displaces you.”

When Matthew and his [farm] supervisor came, they counted buildings and saw my land and what I have. And he wrote 4,000 kwachas ($400). The council said we should determine the money we should get, but over here Matthew just tells us how much he’s going to give.[129]

Matthew Rowe, the owner of Rowe Farming Limited, acknowledged that he, accompanied by a member of the district council, went around the villages on the land six months prior to displacing people to inform residents that the land was in a commercial farming block, and that they would be relocated. He stated that farm representatives had discussions with the residents and gave them the choice to get paid and find land themselves, or have the council find land for them. He said all villagers chose to be compensated. On compensation, Rowe Farming stated that “discussions were had on how much compensation each villager would receive,” without elaborating.[130]

The National Resettlement Policy says that the Government Valuation Department is supposed to carry out the valuation for compensation or validate it if done by a private valuer.[131] A circular issued under the Lands Act also says that district officials should inspect lands before proceeding with an application for title, and should confirm that settlements and other persons’ interests have not been affected.[132]

But most residents Human Rights Watch interviewed were not aware of any valuations or inspections, or said what was done was incomplete. Human Rights Watch interviewed residents in Chishitu section (“Matthew’s Farm”) and Kalengo section (“Sawyer Farm”) who said the District Council had not done an inspection or valuation to assess how these commercial farms would affect their interests.

Other residents on “Matthew’s farm” told Human Rights Watch that Matthew Rowe “was going around with a book, and as he told people [they would have to move], he was writing something in his book.” They did not know whether or how their assets had been valued. When residents complained about their uprooted trees, they said he told them “those are not important.”[133] One resident said Rowe had offered his family 4,000 Kwacha ($400) as compensation, which did not adequately compensate his family, and he refused to accept it. Jeffrey K., 74, also said:

I got seven hectares from the chief in 1996, and we cultivate some of it. Also have mango, banana, and guava trees. [Matthew] said he would give us 1,200 kwachas ($120) to go start farming somewhere else, 1,500 kwachas for a house, 600 kwachas for digging a well. And also said he would provide us transport to wherever it is that we said we wanted to go settle.

We are not satisfied with this offer. We are waiting for them to come again, and we want to sit and negotiate. And now they are spreading rumors that we have agreed to take 4,000 kwachas. We didn’t agree. We don’t want to leave. We are being forced to leave.[134]

Some residents on “Matthew’s Farm” said “the Muzungu” proposed an arbitrary amount to each family after a quick on-the-spot “valuation” of their dwelling. Some, despite having no meaningful choice, signed “Resettlement Agreements” with Rowe for amounts between 1,000–6,000 Kwacha ($100-$600).[135]

Zambia’s policies state that compensation shall be at market value or full replacement cost, whichever is higher, for losses of livelihoods, assets and loss of access to the assets attributable directly to the project.[136]

Matthew Rowe did not elaborate to Human Rights Watch how compensation was determined, but stated that he had discussions with residents concerning how much each would receive. Rowe explained, “I gave them all the money they had asked for to build a house, clear 1 Ha [hectare] of land, spending money as well as fertiliser to start their first season.”[137] He stated that all the residents compensated by Rowe Farming Limited were happy with what they had, which was the reason they signed the agreements and thanked him, continually saying “May God bless you, you are a good man and have done good for us.”[138]

Residents in other areas said commercial farmers or officials recorded some, but not all, assets they would lose. In Ntenge section (“Jackman Farm”), 63-year-old Renee M. said that a district official “asked me how many pigs I have.… The only thing he asked [recorded] is how many children and pigs I have.”[139] Five other Ntenge residents confirmed this.[140]

Silverlands: A Better Example of Corporate ResponsibilityThe Silverlands farm has handled consultations and compensation better than the other five farms investigated by Human Rights Watch. However, even this farm has made mistakes that could have been averted with proper guidance and oversight from government. In June 2017 it decided to halt plans to resettle residents, and instead to adopt a “livelihood improvement plan” for them. Handled correctly and informed by the right kind of consultation, this could be a positive approach.[141]

In 2014, when Silverlands started operations, each family signed an agreement which stated that “If we need to move, to make way for development, Silverlands Zambia Limited will give sufficient time for this.”[142] In June 2016, Silverlands told residents that they would have to move within three to four months, but changed course again in September 2016, saying the move would not happen for some time.[143] Residents complained about the conflicting information, and said it hampered cultivation and upkeep of homes.[144] In March 2017, Silverlands representatives said that the company had gotten almost no guidance from government on resettlement and compensation.[145] In June 2017, Silverlands decided it would not resettle the families remaining on the land, and would instead work in consultation with residents to develop a plan that would allow residents to remain in their homes, working the same land, while seeking to improve the community’s overall wellbeing.[146] In an August 2017 letter Silverlands explained their frustrations about lack of government guidance, claiming that there is a disconnect between different government offices, and between government bodies and traditional authorities.[147] |

Women’s Exclusion from Compensation and Resettlement Discussions

Women Human Rights Watch interviewed said their participation in rare discussions with commercial farmers about compensation was minimal, and they were concerned that even the limited compensation they might get will go to men, not women, and may not reflect assets and losses specific to women.

For example, women who lived in Chishitu section said the discussions with Matthew Rowe were between Rowe and mainly male residents. Residents said that if they are compensated, Rowe would give the payments to men considered the “head of the household.” Women said they would not receive compensation.[148] Agnes M. said: “My parents will receive the payment, not me. Matthew will give [pay] one person in each ‘village.’ [This will be] the head, my father.”[149]

A Serenje district official acknowledged that one woman complained about her family’s compensation going to her husband, saying that he had spent it all on alcohol.[150]

Widows and divorced women may be worse off in compensation negotiations. Laura M., a widow, said, “If you are married, the husband is the one that will ask for money or land. For a woman like me with no husband, the headman will have to talk for me.”[151]

Women said they worried that the amounts paid would not reflect losses they would feel more acutely than men, such as losing access to water sources or to forest products typically gathered by women.

Many women also expressed concern about displacement disrupting caregiving and support networks, which would impact their agricultural work and other activities. In Serenje, multiple households typically live on one piece of land, collectively farming it. Women relatives rely on each other for childcare during agricultural work, and for cooking and fetching water, especially when sick or immediately after childbirth.

Six women from an extended family living in Ntenge section (“Jackman farm”) told Human Rights Watch:

We have six to eight hectares of land all together. And all the women work on their lands. Sometimes we all go together, or sometimes we split up. Some of us will go work while the other women will stay behind and take care of the children.[152]

They were concerned that being separated from other female relatives would mean losing caregiving support, risk increasing their burden of household work, and reduce time available for agricultural work for subsistence. Rose M., a mother of three children who is separated from her husband, said:

If someone has taken their child to the clinic or has something else to do, then one of the other women will do the chores in their house also. We’ll go and cook, help farm, bathe the children, wash dishes, clean the house. How will we do all this if they separate us and make us find our own land?[153]

Fear of violence deters some women from participating in efforts to secure compensation from commercial farmers. Felicia K. from Milumbe section (“Billis farm”) said, “We were scared as women. Sometimes the discussions would turn physical and the men were ready to get physical at any time, while women were not.”[154] Similarly, women in Munte/Bwande section (“Badcock farm”) told Human Rights Watch that discussions between Badcock and residents were heated, and the potential for violence was high.[155]

Destruction of Assets

Some families said they feared for their safety, or that they might lose all their belongings, when commercial farmers started pressuring them to leave. Instead of waiting for compensation and resettlement, some fled. When they returned, many found their homes, crops, and belongings destroyed. They said they now have virtually no hope of securing any compensation or assistance.

For example, several residents displaced from Kalengo section (“Sawyer farm”) said after Sawyer threatened them and expanded land clearing, they decided to move their belongings out of their homes.[156] Nine residents said they were gone overnight because they feared for their safety, and when they returned the next day, their houses were burnt, crops were destroyed, and fruit trees were uprooted. Benson K., 40, said:

We had left our home in the farm and come out looking for land. When we went back to collect the rest of our things, we found our home burned down. They had taken all my belongings—clothes, two jackets, pots, other kitchen things and vessels, hoes.[157]

The displaced residents moved into nearby forested areas, where they had no housing or food reserves, and no permanent right to reside.

Representatives of Sawyer farm disputed that they had burnt or destroyed houses and crops. Instead they stated that as their contractors cleared land, families left of “their own volition as they were well aware they were not supposed to be on the property.”[158] Sawyer asserted that “in all the cases except for one (where there was a death) these houses were in fact used by his contractors and in some case nearly up to two years later!—an impossible task if they were burned down!”[159]

Evictions

Forced Evictions