Summary

“Either you show respect for the CNDD-FDD… or we will beat you to correct you.”

− Muramvya province resident who fled Burundi in October 2017, Isingiro, Uganda, April 12, 2018

President Pierre Nkurunziza’s decision in April 2015 to stand for a disputed third term sparked a political, human rights, and humanitarian crisis which continues to have devastating consequences for many people in Burundi. Violence and intimidation against political opponents across the country escalated ahead of the May 17, 2018 constitutional referendum that would allow the president to extend his hold on power.

Since Nkurunziza made the first move in 2015 to extend his stay in power, Burundian state security forces, intelligence services, and members of the ruling party’s youth league, the Imbonerakure, have carried out brutal, targeted attacks on opponents or suspected opponents, human rights activists, and journalists–killing an estimated 1,700 people and forcibly disappearing, raping, torturing, beating, arbitrarily detaining, and intimidating countless others. According to the United Nations, over 390,000 Burundian refugees fled since the start of the crisis and remain outside of the country, and an estimated 3 million Burundians need humanitarian assistance–over a quarter of the country’s total population. The country’s once vibrant independent media and human rights organizations have been decimated, facing severe restrictions or being banned entirely, and many of their leaders have been arrested or forced into exile. Armed opposition groups have also attacked security forces and members of the ruling party since 2015, with some establishing rear bases in neighboring eastern Democratic Republic of Congo.

On May 11, 2018, unidentified assailants shot and hacked to death at least 26 people, including several children, in Ruhagarika village, Cibitoke province, near the Congolese border, in the single most deadly attack on civilians in Burundi for at least several years. At time of writing, it is unclear whether the attack was related to the referendum, but it highlights the precarious security situation around the referendum as actors from all sides have in the past resorted to violence.

The third (and current) term of Nkurunziza, who has been in power since 2005, was seen by many as a violation of the two five-year term limit set forth in the Arusha Accords–a political framework signed in 2000 that established a power-sharing agreement intended to end the country’s civil war–as well as the country’s 2005 constitution. Nkurunziza and his supporters argued that his first term should not count because he was elected by parliament instead of a direct vote. While Nkurunziza’s third term was disputed, the constitution clearly did not permit him to stand again. To maintain power, the president and his party, the National Council for the Defense of Democracy-Forces for the Defense of Democracy (Conseil national pour la défense de la démocratie-Forces de défense de la démocratie, CNDD-FDD), called for a referendum to change the constitution to increase presidential terms to seven years, renewable only once. However, the clock on terms already served would be reset, enabling Nkurunziza to run for two new seven-year terms, in 2020 and 2027. The change could extend his rule until 2034.

On December 12, 2017, Nkurunziza announced the referendum, warning that those who dared to “sabotage” the project to revise the constitution “by word or action” would be crossing a “red line.” His speech legitimized a government policy of seeking out and punishing anyone perceived to oppose the referendum.

Since early 2017, security forces and the Imbonerakure have continued to kill, rape, beat, detain, threaten, and harass scores of people in Burundi. Some have been targeted after refusing to contribute funds to finance the referendum vote and the 2020 elections. In some cases, simply not belonging to the ruling party was enough to create suspicion and provoke a violent response.

Following international condemnation of the repression at the start of the crisis in 2015, when security forces used deadly force to disperse protests and quash dissent, some of the abuses became more covert in recent years. Across the country, Burundians have regularly reported finding bodies, sometimes decapitated or with their hands tied behind the back. Some bodies were weighed down with stones and found in the Ruzizi River or Lake Tanganyika. Some of the victims were later identified by witnesses as people who were known to have opposed Nkurunziza’s efforts to prolong his hold on power. There has also been an increased reliance on the Imbonerakure in recent years to target perceived opponents, although the police, military, and intelligence services have also continued to commit serious abuses. While supposedly independent, former Imbonerakure members and other witnesses have described how the Imbonerakure’s activities are at times well-coordinated with the state security forces and intelligence services and they often receive orders from military, police, and intelligence commanders.

Based on over 100 interviews conducted between February and May 2018 with victims of abuses, witnesses, family members of victims, and five former members of the Imbonerakure, this report documents repression and serious human rights violations against those perceived to be opponents of Burundi’s ruling party since January 2017. Human Rights Watch interviewed 67 Burundian refugees who fled to Congo and Uganda in 2017 or 2018 and at least 40 Burundians currently living in Burundi. The report also draws on Human Rights Watch’s previous research and reporting on Burundi since the start of the crisis in 2015. The full scale of abuse is difficult to determine and likely significantly higher than what Human Rights Watch has documented, given the climate of fear across the country which makes many victims and witnesses unwilling or unable to report on abuses.

The near-total impunity for crimes committed by the security services and Imbonerakure in recent years has protected the perpetrators and encouraged further abuse. In nearly all the 83 cases of human rights abuses documented by Human Rights Watch for this report, the individuals responsible and their commanders have not been arrested, charged, or tried, even when they have been identified by witnesses. The state has failed to take reasonable steps to ensure security and provide protection for its citizens, and it has not fulfilled its duty to take all reasonable measures to prevent and prosecute these types of crimes.

Human Rights Watch urges the Burundian government to take prompt measures to end the impunity protecting those responsible for killings, rapes, beatings, arbitrary detention, threats, and harassment, and to prevent these abuses, including by its own security forces and the Imbonerakure. Leaders of opposition parties and groups also have the responsibility to take immediate action to dissuade their members from attacking CNDD-FDD and Imbonerakure members and make it clear that they do not sanction such crimes.

The United Nations Human Rights Council established a Commission of Inquiry in September 2016 to document serious crimes in Burundi since April 2015. In September 2017, the commission concluded that it had “reasonable grounds to believe that crimes against humanity ha[d] been committed and continue[d] to be committed in Burundi since April 2015.” The commission’s mandate has been extended through September 2018, but Burundi continues to refuse any form of cooperation with the commission.

On October 25, 2017, judges from the International Criminal Court (ICC) authorized an investigation into crimes committed in Burundi since April 2015. Two days later, Burundi became the first country to withdraw from the ICC. Yet ICC judges found that Burundi’s withdrawal does not affect the court’s jurisdiction over crimes committed while the country was a member. The ongoing investigation brings hope that those responsible for some of the worst crimes committed in Burundi in recent years may eventually be brought to justice.

In September 2015, the European Union imposed sanctions on three senior police and intelligence officials and one opposition member who took part in the failed coup. In November 2015, the United States imposed sanctions on the minister of public security, the deputy director general of the police, and two leaders of the failed coup. Most major donors have suspended direct budgetary support to the Burundian government, but some maintained humanitarian assistance.

Yet much more could and should be done to help curb the abuse and to prevent the situation in Burundi from deteriorating further.

To show that there are consequences for the widespread abuses that have continued since 2015, the EU and US should expand targeted sanctions to those further up the chain of command. The UN Security Council should also impose targeted sanctions, including travel bans and asset freezes, against individuals responsible for ongoing serious human rights violations in Burundi.

Foreign governments, UN bodies, and others concerned about the situation in Burundi should increase pressure on the government and opposition to stop the kinds of abuses documented in this report and call on the government to hold perpetrators to account. They should also advocate strongly for the protection of civil society actors and journalists, and press Burundi to cooperate with UN mechanisms, including the Commission of Inquiry, and allow for the deployment of 228 UN police officers, as authorized by a July 2016 Security Council resolution.

The East African Community (EAC) has attempted to initiate dialogue among key Burundian players since 2014, but these efforts have made no tangible progress and have been hampered by an apparent unwillingness among regional leaders to press Nkurunziza to make real concessions. It is time for regional leaders to step up and take a strong position in pressing Nkurunziza and his government to urgently resolve the country’s crisis and end the violence and repression.

Recommendations

To the Government of Burundi

- Give clear and public instructions to the security forces, the intelligence services, and the Imbonerakure that extrajudicial executions, rape, beatings, arbitrary arrests, threats, harassment, or other types of abuse will not be tolerated, and that any individual suspected of carrying out or ordering these abuses will be brought to justice. Immediately investigate the role of individuals involved in these abuses;

- Issue clear instructions to the security forces, intelligence services, and the Imbonerakure that under no circumstances should persons be targeted for attack, intimidations, or threat on account of their past or present political affiliations, and issue similar directives to the CNDD-FDD hierarchy;

- Remind the police of their duty to ensure, in an impartial manner, the safety and protection of all Burundians, regardless of their political affiliations;

- Stop the intimidation, harassment, and arbitrary arrest of journalists, human rights activists, and members of the opposition who may have raised questions on the constitutional referendum;

- Allow human rights activists to investigate and report on human rights abuses without hindrance;

- Cooperate with United Nations mechanisms, including the Commission of Inquiry, allow them into the country, and allow for the deployment of 228 UN police officers, as authorized by a July 2016 Security Council resolution;

- Resume all cooperation and collaboration with the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), as called for in a UN Security Council April 2018 Presidential Statement.

To Leaders of Political Parties and Opposition Groups

- Remind members that political killings and other human rights abuses by their opponents can never justify unlawful retaliation;

- Fully cooperate with judicial authorities investigating political killings and related abuses, including by providing relevant information about such incidents.

To Foreign Governments and Inter-Governmental Organizations

- Continue to express concern about political killings and other abuses in Burundi, raising specific cases where appropriate, and urge the authorities to take effective action to bring the perpetrators to justice and prevent further abuses (as recommended above);

- Expand targeted United States and European Union sanctions and urge the UN Security Council to impose targeted sanctions, including travel bans and asset freezes, against individuals responsible for ongoing serious human rights violations in Burundi.

To the UN Security Council

- Impose targeted sanctions, including travel bans and asset freezes, against individuals responsible for ongoing serious human rights violations in Burundi;

- Maintain scrutiny on the situation in Burundi, including by holding regular public meetings and discussing UN reports highlighting public incidents of incitement to hatred and violence every three months, as outlined in UN Security Council resolution 2303.

To African Leaders, the African Union, and Other Regional Bodies

- Fully engage in helping to resolve the political and human rights crisis in Burundi and prevent a further escalation of violence which could have consequences for the broader region, including by pressing Nkurunziza and his government to immediately end the current violence and repression;

- Indicate clearly that there will be real consequences if no progress is made in ending the widespread violence and repression. This could include application of article 4 (h) of the Constitutive Act of the African Union, which authorizes the body to intervene in a member state in certain circumstances, particularly in the event of crimes against humanity.

To the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights

- Conduct a mission to Burundi in order to ascertain the general state of human rights following the referendum. Issue a public report on this mission.

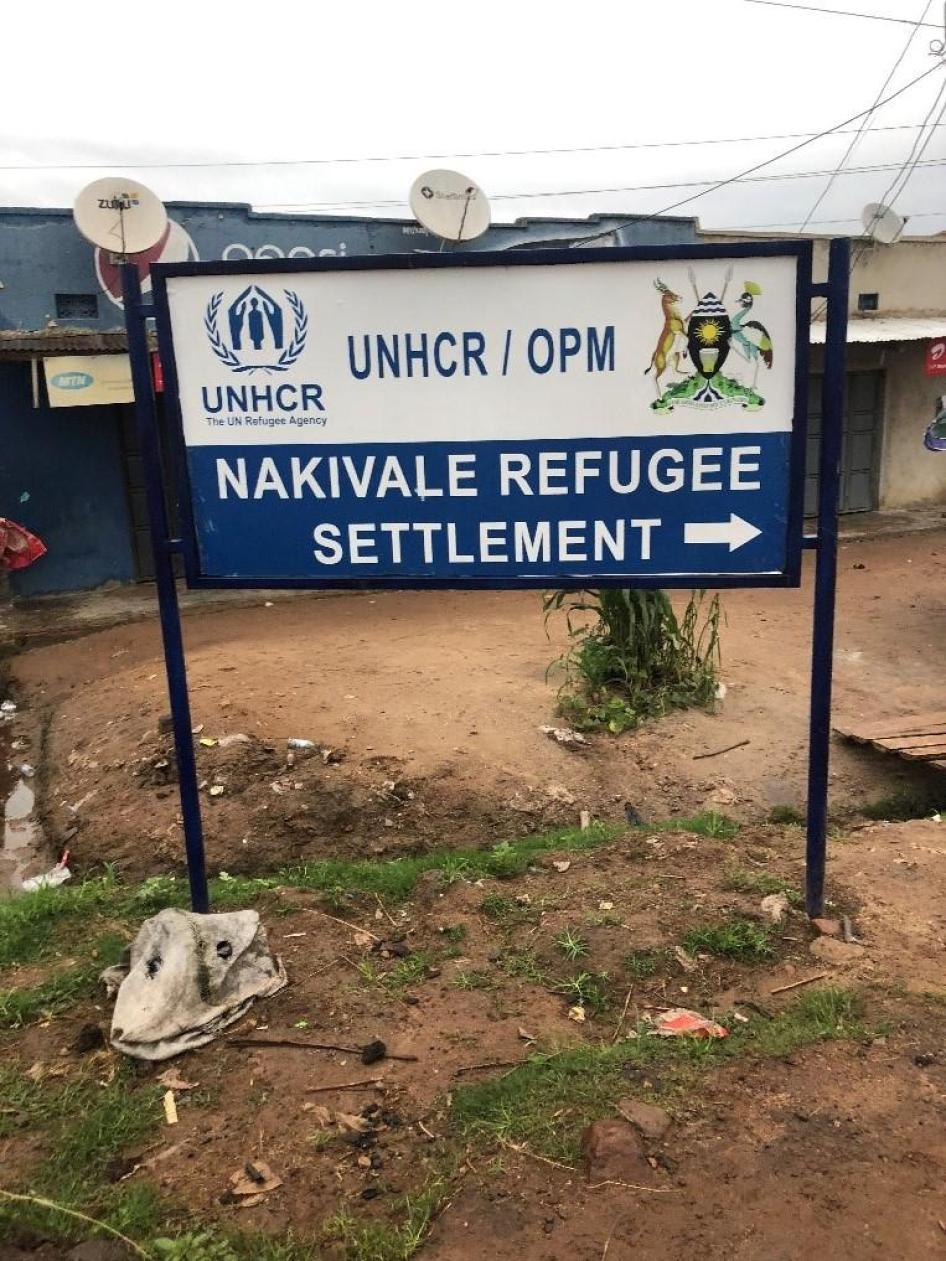

Methodology

This report is based on over 100 interviews conducted by Human Rights Watch between February and May 2018 with victims of abuses, witnesses, family members of victims, and five former members of the Imbonerakure, the ruling party’s youth league. This includes in-person interviews with 67 Burundian refugees living in camps in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo and in Uganda, as well as interviews with at least 40 people currently living in Burundi. Human Rights Watch’s research in the camps focused primarily on individuals who fled Burundi recently due to real or perceived security threats. Human Rights Watch did not conduct in-depth interviews with people who it identified as having left the country due primarily to humanitarian or socio-economic reasons.

Interviews were conducted in French or Kirundi with interpretation to French.

The report also draws on Human Rights Watch’s previous research and reporting on Burundi since the start of the crisis in 2015. The full scale of abuse is difficult to determine and likely significantly higher than what Human Rights Watch has documented, given the climate of fear across the country which makes many victims and witnesses unwilling or unable to report on abuses.

Human Rights Watch shared information on recent abuses, particularly abuses by the Imbonerakure, with Nancy-Ninette Mutoni, the executive secretary in charge of communication and information for the CNDD-FDD, in April 2018, but at time of writing, received no answer.

Because of fear of reprisals against victims and witnesses or their relatives in Burundi, the names of victims and individuals who spoke to Human Rights Watch have been withheld.

All of the interviewees provided their informed consent to Human Rights Watch. None of them received payment or other benefits for having given information.

I. Context

Human rights abuses in Burundi in the run up to the constitutional referendum is best understood in the context of the 2015 elections and the country’s political climate, as well as the broader context of Burundi’s civil war, which ended in 2009.

Sparked by the assassination in 1993 of President Melchior Ndadaye, Burundi’s first democratically elected Hutu president, Burundi’s civil war was fought along ethnic lines between Tutsi and Hutu and claimed tens of thousands of lives.[1] The CNDD-FDD, the main Hutu rebel group, entered into a ceasefire with other groups in 2003 and then won the 2005 elections, resulting in Nkurunziza’s first term as president.[2] Members of the National Liberation Forces (Forces nationales de libération, FNL) armed group remained active in the country until their demobilization in 2009 and the group’s transformation into a political party.

Burundi’s history since the end of the civil war has been marked by political violence. Today, many politicians, some of whom rose to positions after fighting in armed groups, use violence as a tool for resolving differences and continue to speak of it as the only avenue for gaining or holding power.

In the run-up to the 2010 elections, the ruling CNDD-FDD and the FNL vied for the country’s majority Hutu vote. In doing so, both parties resorted to violence.[3] Electoral code violations were reported in the 2010 communal elections in isolated areas, resulting in a boycott by the opposition for the remaining elections, including the presidential vote, giving the CNDD-FDD a near total monopoly of power. From the end of 2010 through 2012, killings of real and perceived political opponents escalated sharply.[4] Former combatants and members of the FNL were particularly targeted.

In late April 2015, public demonstrations broke out in response to Nkurunziza’s decision to seek a third presidential term. The Burundian police used excessive force and shot demonstrators indiscriminately. After a failed coup d’état by a group of military officers in May, the Burundian government intensified its repression against suspected opponents and suspended most of the country’s independent radio stations.

|

Crackdown on Civil Society and the Media Whereas once the government tolerated criticism, albeit unhappily, any space for rights groups and independent journalists to operate freely in Burundi has vanished. Since early 2015, some leading Burundian human rights defenders have been attacked, organizations have faced severe restrictions or were shut down entirely, and most leading civil society activists and independent journalists fled the country for their security.[5] In August 2015, Pierre Claver Mbonimpa, one of the country’s leading and most outspoken human rights activists and president of the Association for the Protection of Human Rights and Detained Persons (Association pour la protection des droits humains et des personnes détenues, APRODH), was shot in the face and neck while driving home from his organization’s office.[6] Mbonimpa survived, but his son-in-law and son were later killed in October and November. Earlier, in May 2014, Mbonimpa had been arrested and charged with endangering state security, in connection with remarks he had made on the radio.[7] He was provisionally released on medical grounds in September 2014, but the charges against him were not dropped.[8] In October 2016, Interior Minister Pascal Barandagiye banned five important Burundian nongovernmental organizations and suspended five others. Barandagiye said the banned groups had “tarnished the image of the country” and “sowed hatred and division in the heart of the population.”[9] The few civil society activists who chose to stay in Burundi did so at great risk. Two human rights activists, Nestor Nibitanga and Germain Rukuki, were arrested in 2017 and held by Burundi’s national intelligence service (Service national de renseignement, SNR). Both were charged with crimes against state security.[10] In April 2018, Rukuki was sentenced to 32 years in prison on charges of “rebellion,” “threatening state security,” “participation in an insurrectional movement,” and “attacks on the head of state.”[11] Nibitanga and Rukuki remain in detention at time of writing. The government is openly hostile towards the independent media. From 2010 to 2015, journalists who reported on the political situation and human rights abuses were targeted with repeated summonses and arrests. In 2015, several independent radio stations were attacked and damaged and, in August, members of the intelligence services severely beat Esdras Ndikumana, correspondent for Radio France Internationale and Agence France-Presse, as he was taking photographs after the murder of the former intelligence chief.[12] As the referendum approached in 2018, the government continued its crackdown on the press. On April 11, the comments section for the online version of Iwacu, a well-respected and widely read independent newspaper in Burundi, was suspended for “violation of professional standards” by the government-controlled National Communication Council (CNC).[13] On May 4, the CNC suspended the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) and the Voice of America (VOA) from broadcasting in the country for six months.[14] |

Nkurunziza was declared the winner of the disputed July 2015 presidential election, which he contested as the sole presidential candidate, as most of the opposition boycotted the polls. The ruling CNDD-FDD quickly consolidated its hold on power, restricting the activities of opposition parties and forcing many leading members to flee into exile.

Violence escalated in the second half of 2015, with targeted killings–including of high-profile government and opposition figures–, deadly police search operations, abuses by members of the ruling party youth league, and attacks by armed opposition groups against members of the security forces and the ruling party. Grenade attacks in the capital, Bujumbura, became increasingly frequent. The authorities arrested and detained hundreds of suspected opponents, in many cases arbitrarily and unlawfully. Torture by the intelligence services and the police became widespread and extremely brutal.[15]

In early 2016, following international condemnation of the situation in Burundi, some of the abuses became more covert, with an increase in abductions, enforced disappearances, and unexplained deaths.[16] Several military officers and soldiers were also killed, as distrust and suspicion caused divisions in the army.

As of April 30, 2018, there were 424,687 Burundian refugees in Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda, and the Democratic Republic of Congo, 390,116 of whom became refugees post-April 2015, according to the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR).[17]

Since 2016, leading human rights organizations and independent media have been closed down by the Burundian government, limiting independent oversight. The National Independent Human Rights Commission (Commission nationale indépendante des droits de l’Homme, CNIDH), established in 2011, has lost its credibility by its refusal to investigate abuses and publish findings. The CNIDH was downgraded by the Sub-Committee on Accreditation of the Global Alliance of National Human Rights Institutions in February 2018 over its lack of independence, losing its right to vote in international forums.

|

The Arusha Accords, the Constitution, and Term Limits

The Arusha Peace and Reconciliation Agreement (known as the “Arusha Accords”) and the 2005 Constitution are central to understanding Burundi’s ongoing political crisis. The Arusha Accords are a political framework widely attributed with having brought Burundi out of its civil war and provided for power sharing, coalition-building, government participation, a system of checks and balances, and the integration of former combatants into the military. Signed in 2000, the Accords paved the way for the Constitution adopted five years later and became a defining feature of Burundian national identity and the cornerstone of a consensus-led system in which Hutus and Tutsis governed together. The dispute around Nkurunziza’s third term and the legality of his candidacy was the crucial element that sparked the 2015 violence. The 2005 Constitution calls for a strict two-term limit for the presidency based on universal suffrage,[18] while also stating that the first election, in 2005, would be carried out indirectly by members of the National Assembly and the Senate.[19] After an unsuccessful attempt to pass legislation in 2014 that would explicitly allow the president to contest a third term, the Constitutional Court paved the way for Nkurunziza’s third term in April 2015 by ruling that Nkurunziza’s first term was exceptional and should not count towards the two-term limit. In September 2015, following Nkurunziza’s successful election for a third term, the government established a commission of inquiry to conduct a national dialogue that would help chart the country’s political future. Known as the Commission of Inter-Burundian Dialogue, it was tasked with holding debates across the country on social, political, and peace consolidation and to assess core documents such as the Arusha Accords and the Constitution. The main recommendation of its August 2016 mid-term report was to change the presidential term limits.[20] On December 12, 2017 Nkurunziza announced the referendum. |

The referendum took place in a context of violence, fear, and intimidation. The government was clear that it would seek out and punish anyone perceived as opposing the proposed changes. On December 12, 2017, Nkurunziza warned that those who dared to “sabotage” the project to revise the constitution “by word or action” would be crossing a “red line.”[21] On February 13, the spokesperson for the Public Security Ministry, Pierre Nkurikiye, publicly declared, in reference to people arrested for allegedly encouraging others not to register: “This is a warning, a warning to anyone who by his actions or words is hindering this process … he will be immediately apprehended by the police and brought to justice.”[22]

Local authorities reinforced these threats. Videos circulated on social media show authorities encouraging people to be vigilant toward anyone who may be against the referendum. In one example, on January 27, Revocat Ruberandinzi, the ruling party representative in Butihinda, in Muyinga province, declared in a meeting that was filmed and posted online: “Whoever will be caught instructing people to vote no on the constitution [referendum], bring them to us. Do you understand me? The OPJ [judicial police] will not get here; we will take him ourselves…”[23] In another example, on February 13, Désiré Bigirimana, the administrator of Gashoho, also in Muyinga province, told a crowd, “Anyone who says anything against the ‘yes’ [vote] or against Peter [President Nkurunziza], beat him over the head, and call me once you have tied him up.”[24]

Government officials also openly told Burundians that they must vote yes. A resident of Makamba province told Human Rights Watch: “The [local] administrator called a meeting in January to explain the referendum and why we had to vote yes. He sent the Imbonerakure out to force people to go to the meeting. We spent the entire day there; nobody could work. The Imbonerakure had clubs, and they would beat you if you did not attend.”[25]

Far from giving the Burundian people the opportunity to have a say in their country’s political future, the referendum and its surrounding context send a dangerous warning about where Burundi is going, as the government entrenches its hold on power even further through fear, violence, and repression.

II. Abuses by the Imbonerakure

Political parties in Burundi have long used youth groups for a variety of functions. In late 2008, the CNDD-FDD mobilized youth throughout the country into quasi-military groups, called the Imbonerakure, to demonstrate the party’s strength.[26] The CNDD-FDD used the Imbonerakure from 2009 into the 2010 electoral period to intimidate and harass the political opposition, and they often engaged in open street fights with other parties’ youth wings. Since then, the reliance on youth to intimidate and attack perceived opponents of the CNDD-FDD at the local level has increased.

Imbonerakure members have consistently been shielded from justice. In numerous incidents documented by Human Rights Watch, members of the Imbonerakure, the intelligence services, and the security forces appeared to cooperate in intimidating and attacking suspected opponents, which indicates a degree of state involvement in the Imbonerakure’s actions.

From 2010 to 2012, members of the Imbonerakure frequently attacked and threatened current and former FNL members, sometimes jointly with members of the intelligence services or the police.[27]

Following a clash between the Burundian army and members of an unknown armed group between December 30, 2014, and January 3, 2015, Imbonerakure members, Burundian soldiers, and police officers committed at least 47 extrajudicial executions of members of the armed group, some of whom had surrendered, according to Human Rights Watch’s research. Imbonerakure members actively participated in the killings, some using machetes. Witnesses said that during the clashes, police and soldiers transported some Imbonerakure in government vehicles and provided them with weapons. Witnesses also said they saw Imbonerakure tie up, beat, or kill captured men from the armed group in various areas in Cibitoke province.[28]

Since April 2015, members of the Imbonerakure have arrested, beaten, or attacked scores of FNL members across the country. In May 2016, Human Rights Watch interviewed over 70 victims of rape and sexual violence, some of whom said they had recognized members of the Imbonerakure who had raped them. Some women were targeted because their husbands or male relatives were members of opposition parties such as the FNL.[29]

In late 2016, reports of killings, torture, and beatings committed by the Imbonerakure increased, demonstrating that the widespread impunity for the group’s members and the government’s unwillingness to prosecute or rein in the group continued. Imbonerakure members set up makeshift roadblocks on main and secondary roads in several provinces, including Kirundo, Makamba, Muyinga, Muramvya, Ruyigi, and Ngozi, detained passersby, extorted money or valuables, and sometimes beat them. Some victims said Imbonerakure members accused them of collaborating with opposition groups. In other cases, it was unclear why they were targeted.[30]

The Imbonerakure used roadblocks in February 2018 to check if passersby had registered for the referendum, beating those who had not or who could not present proof of registration. Imbonerakure members have also beaten several people accused of not registering for the referendum or of campaigning against the constitutional change.[31]

In April 2018, Human Rights Watch interviewed five former Imbonerakure members who explained how the group has been operating since 2015.

One former member from Bujumbura explained that he joined the group as a 19-year-old in 2015, when tensions were high. He was a member of the group for one year before quitting in 2016. When he left the group, he was forced into hiding and eventually fled the country. “Do not disassociate the Imbonerakure from the CNDD-FDD,” he said. “The party has an entire system established to manage the group.” He explained how the group works at a local level:

In each province, commune, zone, and hill there is a leader of the Imbonerakure. These leaders work along a hierarchy that goes up to the top of the party. If there is a person the party needs to kill or kidnap, the order can easily be given for the Imbonerakure to execute it.... The Imbonerakure are used in place of the army and the police, but we often worked together with these groups. Our leaders were treated like leaders of the police.[32]

The former member explained why he joined the Imbonerakure: “In 2015 Nkurunziza was going to contest his third mandate and there were many protests. Some of the youth I knew convinced me to join, but I was tricked. They promised me a government job, but instead I got blood on my hands, and then I became scared. Soon I was seen badly by the others and they started to consider me a traitor.”[33]

A 21-year old former Imbonerakure member from Gitega province told Human Rights Watch, “Poverty can make you join these movements. Because of poverty, the Imbonerakure have recruited so many youths. We are all unemployed and we are promised reliable work.”[34]

The man said that in April 2017, Senate President Révérien Ndikuriyo visited the Imbonerakure in Gitega province and told them to be ready to work hard. “Ndikuriyo told us that tomorrow’s Burundi depends on the Imbonerakure and that Rwanda could take over if we are not prepared. His speech convinced many of us.”[35]

The former Imbonerakure member then described who they targeted when he joined the group: “First and foremost, the Imbonerakure target opponents or people we think are opposed to the CNDD-FDD. But we also targeted Tutsis because most of the members of the opposition were Tutsi, and we were told that the Tutsi are supported by Rwanda and Rwanda was considered an enemy.”[36]

A former FNL combatant explained how he was forced to join the Imbonerakure, but later decided to flee after he refused to participate in killings. “I received an order to kill other FNL who were in a jail in Cibitoke,” he told Human Rights Watch. “But I could not do it.... They had told me that I was still new to the Imbonerakure and that they did not trust me. They said I needed to do something to prove that I could be trusted in the group.... When I was with the Imbonerakure, we used to say, ‘We will cut the throats of our opponents.’”[37]

A 33-year-old man from Gitega explained to Human Rights Watch that he briefly joined the Imbonerakure in 2017. “They would tell us it was our job to defend Burundi if ever we were threatened by enemies of the peace,” he said. “We would get physical training and they would tell us, ‘A young Imbonerakure must be strong, courageous, tough, and a visionary.’ They would insist that we learn the ideology of the CNDD-FDD, and we were told, ‘If we give you a mission to find someone, catch him. Even if you have to go underground. Our party has given you the means you need to catch those who betray our party’s ideals.’”[38]

III. Patterns of Violence in 2017 and 2018

Incidents of violence that forced people to flee Burundi in 2017 and 2018 followed several distinct patterns of fear: fear after a family member was killed, assaulted or raped; fear after a family member was kidnapped or disappeared; and fear of arrest, beating, killing, or forced recruitment into the Imbonerakure or the CNDD-FDD.

A common theme heard repeatedly by Human Rights Watch was a concern of guilt by association. One family member of a person who went missing explained, “If you have a brother who goes missing, that means people will assume he was tied to protests or the opposition. When your brother is missing for a few days, it means he is dead and you could be next.”[39] This sentiment is demonstrative not only of the widespread fear that victims and family members of victims continue to feel, but also of the lack of trust in the security services to protect civilians.

The incidents from 2017 and 2018 documented by Human Rights Watch occurred throughout the country, in 9 of Burundi’s 18 provinces. Tensions and abuse escalated since the referendum was announced in December 2017 as security services and the Imbonerakure targeted people perceived as being against the constitutional change.

Killings

During its recent research, Human Rights Watch documented 15 cases of individuals killed by the security forces or the Imbonerakure in 2017 and 2018. This is likely just a very small sample of the total number of incidents. Burundian human rights organizations have reported on 482 people killed in 2017 and the first part of 2018.[40] The majority of victims were reportedly killed by the state security services or the Imbonerakure.

Of the incidents documented by Human Rights Watch, two victims were accused of refusing to register for the referendum vote. Dismas Sinzinkayo, an FNL member, was beaten to death by the Imbonerakure in Kayanza province on February 24, 2018. Someone close to Sinzinkayo, who witnessed his killing, told Human Rights Watch:

The Imbonerakure arrived [at Sinzinkayo’s house] late in the evening, around 10:30 p.m. They asked for the receipt [showing he had registered]. He refused to show it to them. The Imbonerakure then pulled him out of his house and started to beat him. As they were beating him, they kept asking for the receipt. He said he had registered, but they did not care by then. They beat him over and over with clubs. When they were finished, they left, and I went to see him. He was dead on the spot. We buried his body the next day.[41]

On February 14, 2018 local authorities in Cankuzo province took Simon Bizimana, 35, from his home because he had refused to register to vote. They took him to a meeting of local administrators where he was filmed explaining that he had not registered based on his religious principles.

Burundian media reported that local authorities beat Bizimana with iron rods after the meeting.[42] While Human Rights Watch cannot confirm this, a witness at the local meeting told Human Rights Watch that a senior state official beat Bizimana before he was taken to jail. “She beat him with his Bible,” the witness said. “She yelled at him, ‘If this was a time of war, we would bury you alive!’”[43]

Someone close to Bizimana who was able to visit him once in detention said that he told her his entire body hurt from the beatings he had received. “He asked for money, so he could buy painkillers in prison,” this person told Human Rights Watch. “He said his head was in constant pain.”[44]

On March 14, Bizimana was taken to the local hospital in a near comatose state. Witnesses at the hospital told Human Rights Watch that he could not speak and that the police had to transport him in a wheelchair. “He was in very bad shape,” said one witness from the hospital. “He was very thin and he had clearly been living in the same clothes while with the police. He was filthy. We tried to speak with him, but it was no use, he was already almost dead.”[45] Bizimana died at the hospital on March 18.[46]

On July 9, 2017, Imbonerakure took a 30-year-old teacher from his home because he was suspected of opposing Nkurunziza. His brother explained to Human Rights Watch:

[My brother] refused to join the Imbonerakure. They gave him warnings, but he ignored them. After he was taken, we did not know what had happened. The family told the police about the threats from the Imbonerakure, but they said he may just be hiding. But on July 12, we found his body in a field; it was decomposing. He had been strangled, and there were signs of beating. When we went to tell the police we had found his body, they said, ‘Go bury him with dignity. Many other families can’t bury their loved ones.’… I knew then that the Imbonerakure are untouchable in the country, that they can kill as they wish. Since [the Imbonerakure] knew me, I had to leave [the country].[47]

The mother of a 20-year-old killed in May 2017 in Muramvya province explained that her son had been targeted ever since he participated in the 2015 protests. When she saw his body, with a large stone forced into his mouth, she knew she had to leave the country. “I saw bloodshed in 1993,”[48] she said. “Now my son is dead; I have no future in Burundi.”[49]

The wife of a 50-year-old former FNL combatant from Bujumbura Rural province told Human Rights Watch that her husband had succumbed to the pressure and joined the Imbonerakure around 2010. For many years, things were okay, she said. Then in March 2017, a group of her husband’s Imbonerakure colleagues came to their house and told him, “Come with us, you traitor. We don’t serve two pieces of meat at the same time. Either you are with the CNDD-FDD or you are with the FNL.” The Imbonerakure took him, and he never returned. The man’s wife was told a few days later that her husband’s body had been dumped in Lake Tanganyika. Fearing for her own life, she took their children and fled to Congo.[50]

The mother of a 30-year-old victim killed in February 2017 in Bujumbura Rural province told Human Rights Watch: “The Imbonerakure wanted my son to join them, but he refused. Then they started to say he was a traitor. One night in February 2017, they came to the house and asked my son for money. He gave them what he had, but they still shot him in the stomach. He died there. I decided I had to leave the country.”[51]

Rape

Rape and sexual violence by members of the security services and the Imbonerakure have been widespread in Burundi since the start of the crisis in 2015. These crimes have continued in 2017 and 2018. A Burundian human rights group reported 77 cases of sexual violence in 2017, the majority of which were allegedly committed by state security services and the Imbonerakure, but it is difficult to ascertain which cases have a political aspect.[52] In its recent research, Human Rights Watch documented seven cases of rape by members of the Imbonerakure. In six cases, the rape appears to have been a form of punishment against a family member who was perceived as an opponent to the ruling party.[53] Knowledge that Imbonerakure members are able to commit these acts in complete impunity led victims (and often their family members) to flee the country.

The 28-year-old wife of a well-known FNL member in Ngozi province told Human Rights Watch how she was raped in late February 2017, when she was seven months pregnant. “The Imbonerakure were doing a night patrol and they came to our house,” she said. “My husband was there, and two Imbonerakure took him outside while another stayed behind and raped me. He saw that I was pregnant, but he did not take pity on me. Instead, he said he wanted to force me to miscarriage. As he raped me, he said, ‘Know that all the wives of opponents of the CNDD-FDD will eventually belong to us.’”[54]

The 17-year-old niece of a known opponent of the CNDD-FDD from Rumonge province was raped on February 27, 2017. Before the attack, her uncle had been told by a well-known Imbonerakure leader in the area, “We know you don’t like Peter [referring to Nkurunziza]. But Peter is going to rule over you for decades to come, and there is nothing you can do about it. We will find a way to get you.”[55] The man’s niece was raped by an Imbonerakure days later. The family told local authorities but felt that this only put them in more danger and decided to leave the country.

In May 2017, the Imbonerakure attacked the home of a man who refused to participate in nightly patrols with them in Cibitoke province. During the attack, an Imbonerakure member raped the man’s 35-year old wife. She told Human Rights Watch, “When I wanted to cry, he pushed me down on the bed and forced himself on me. The other Imbonerakure were in the living room telling our children not to panic.... The next day I went to the hospital, and I later learned that the Imbonerakure knew I had sought medical attention. After that, we knew it was not safe for us to stay.”[56]

A 29-year-old woman from Cibitoke province explained to Human Rights Watch how she was gang-raped by Imbonerakure members at her house:

I was against the CNDD-FDD and the Imbonerakure. I got in a fight with my husband about how I did not support Nkurunziza, and he left the house. A few nights later, three Imbonerakure came to the house. I was afraid to open the door to let them in, but they insisted. The leader said, “We are with the Imbonerakure and you are a traitor.” He told me to undress, but I refused. He tore off my clothes with a knife. I was afraid he was going to cut my throat. By force, all three raped me in front of my children. It was horrible. They left me unconscious. The next day I went to the hospital, but I had already decided to leave the country.[57]

Abductions

Eight people who sought refuge recently in Congo or Uganda told Human Rights Watch they fled the country after family members went missing. Several of them said that they had nothing to do with politics, but they felt sufficiently concerned about their association to the person who went missing that they decided to flee. Others said they were openly threatened after a family member vanished.

The wife of a man who went missing in Ngozi province in February 2017 told Human Rights Watch how Imbonerakure came to her house in the night, accused her husband of not showing enough support to the CNDD-FDD, beat him in front of her and her children and took him away. She did not see him again and said she continued to be traumatized by how members of the Imbonerakure acted with impunity. “The Imbonerakure kill to show their loyalty,” she said. “They openly say they have a strategy to make wives of opponents into widows and to get their daughters pregnant. After my husband went missing, I could not take it anymore, so I left.”[58]

The wife of a man who went missing in January 2017 in Rumonge province told Human Rights Watch:

The Imbonerakure came to our house late in the evening and took my husband. To this day, I don’t know why; my husband was never involved in politics. Maybe there was a rumor about him. A few days later, an Imbonerakure came to my house and said, “I am ready to take you as a wife as you have no husband.” He was one of the men who took my husband, so I understood my husband was dead. This Imbonerakure came by again and said I should be loyal. It made me fear for my life.[59]

The wife of a former FNL combatant said Imbonerakure members asked her husband in February 2017 if he supported the CNDD-FDD. He said he did not. A few weeks later, two men suspected of being from the intelligence services came to the house and took her husband. He was never seen again. “I was scared after they took my husband away,” she told Human Rights Watch. “I thought they would also assume that my kids and I are rebels, so we fled.”[60]

Beatings, Fear, and Intimidation

Over the course of 2017 and 2018, government forces and, in particular, the Imbonerakure threatened, beat, and intimidated perceived and real opponents, targeting in particular members of opposition political parties. Human Rights Watch documented numerous cases of people targeted because they were suspected of refusing to participate in the referendum or insulting Nkurunziza or the CNDD-FDD. Many people who fled the country in 2017 and early 2018 told Human Rights Watch they felt they faced a stark choice: flee or die.

A resident of Karusi province described a beating he witnessed at a roadblock manned by the Imbonerakure in late January 2018:

The zone chief [a local authority] and the Imbonerakure had set up a barrier to check the receipts to see if people had registered. This was just at the end of the registration period. I saw them ask a driver from Muyinga [province] for his receipt, but he did not have it. The Imbonerakure had clubs and they pulled him out of the car and beat him.... There were two Imbonerakure. As they were beating him, the Imbonerakure yelled, “If you do not register, it means that you are against the referendum!” This happened near my home and after I saw that, I knew that I could not travel without my receipt.[61]

A member of the FNL said he was suspected of telling people in his area to vote no. Imbonerakure arrested him on February 2 in Kirundo province:

They came to the house at 7 a.m. and said they had been sent by the local chief. There were five Imbonerakure, and they started to beat me straight away. They beat me in front of my wife and kids. As they beat me, they said, “We were told to come for you because you are telling people to vote no!” But it was not true.... I was taken to jail and the police told me I would have to wait there until I was charged. I did not have a lawyer. In the end, I was released without charge. They just told me to leave.... When I got out of jail the authorities and the Imbonerakure were launching their own campaign and telling people to vote yes on the referendum.... I am scared I will be arrested again or killed during the electoral period.[62]

The man was released on February 20, 18 days after his arrest.

A businessman from Karusi province told Human Rights Watch that Imbonerakure beat him on February 10, 2018 at a roadblock. He had his receipt with him, but he did not show it, insisting he was a Burundian and did not have to prove anything. “There were many of them and some had metal cables,” he said. “They started to hit me, and I fell off my bike. They continued to beat me on the ground and yelled, ‘We will fight all opponents!’ This is happening all over; everyone is scared of the Imbonerakure.”[63]

A member of the opposition group Movement for Solidarity and Democracy (Mouvement pour la solidarité et la démocratie, MSD) from Bubanza province explained to Human Rights Watch how he started to receive threats after the 2015 protests:

I was an open member of the MSD, and life became very difficult for me after 2015. When my friend from the MSD was killed by the Imbonerakure in 2016, I knew it was serious for us [MSD] members.... The Imbonerakure do their sport on Saturdays and sing about raping the wives of opponents.[64] They also move around at night with clubs and threaten people. It was traumatizing for me, and when they threatened me, I knew I had to leave. Life is not easy here, but at least I don’t live in constant fear.[65]

The MSD member fled to a refugee camp in Congo in February 2017.

Other members of political parties, particularly former combatants from the FNL, explained how they were under intense pressure to join the Imbonerakure or the CNDD-FDD. Those who refused were threatened with death or arrest. Many of these men have been forced into hiding.

One former FNL combatant from Cibitoke province explained to Human Rights Watch how he was pressured to join the party and participate with the Imbonerakure. When he refused, he was summoned by the police who told him, “You are an FNL rebel, and yet you act as if this is your country. This is Nkurunziza’s country. We know you are still working for your party and that you refused to join the CNDD-FDD. You made your choice.”[66] After this threat, the former combatant said he had no choice but to flee.

A member of the MSD described to Human Rights Watch how he was held by the intelligence services for six days in 2015 and beaten. He was then transferred to prison until his release in February 2017, when he returned to his home in Mwaro province. “Once I got home, the Imbonerakure would follow me and ask, ‘Are you sure you left the MSD?’,” he said. “I told them that I had left the party, but I went to a small MSD event in March [2017], and they saw me there. That’s when the real threats started. The Imbonerakure started to say they could easily send me back to prison or kill me. I had already lost one brother and my father to this violence in 2015, so I decided to flee.”[67]

Other members of opposition groups, especially those arrested during the 2015 protests, were threatened if they did not pay the Imbonerakure money. For example, an MSD leader from Cankuzo province told Human Rights Watch that he had been arrested and sent to prison for one and a half years on the charge that he was tied to rebellion. He was released in May 2017 and returned home. He said:

Once I was home the Imbonerakure would threaten me. They would come and say I needed to pay money to help fund the elections. Sometimes they were with the chef de zone [a local authority]. They said I needed to pay 150,000 FBU [approximately US$85] a month for three months. They would say, “If you don’t have the money, you will go back to prison. You will see!” I was scared that if I did not have the money I would be arrested again. I could not stand to do more time in prison, so I fled.[68]

People not affiliated with opposition parties told Human Rights Watch that they were threatened with death, beatings, or imprisonment for not paying ad hoc taxes required by state authorities and collected by the Imbonerakure. They were told some of these taxes were to pay for the referendum vote and upcoming elections. A 29-year-old man, who had lived in Bujumbura until he decided to return to his home village in Muramvya province in 2016, told Human Rights Watch:

When I got home, people knew I was from Bujumbura. I had friends who had been arrested by the SNR, so to prove my loyalty I was pressured to join the CNDD-FDD. They forced me to join the party, so I did. But last year they said I had to contribute money for the elections. They said the money was for the party and to pay for the vote.... I had not found work and I had trouble paying. Soon I started to get threats from the Imbonerakure saying, “We will give you the choice. Either you show respect for the CNDD-FDD and pay, or we will beat you enough to correct you.”[69]

One resident of Rumonge province, a victim of a beating, told Human Rights Watch that he was stopped by a group of Imbonerakure in December 2017, and the head of the group, whom the victim identified as Manirampa, demanded money for the May 2018 referendum:

I refused to pay. So they beat me to the point where I lost consciousness. I woke up in the Rumonge jail and I was accused of disturbing the public order and peace. They also accused me of spreading opposition radio programs on WhatsApp and Facebook to incite people to protest against the ruling power. My brother works at the police, so he was able to get me out of the jail, but once I was released I had to flee.[70]

Three refugees told Human Rights Watch that they had to flee Burundi recently because they were tied to civil society organizations.

The brother of a member of the Forum for Awareness and Development (Forum pour la conscience et le développement, FOCODE) was forced to flee the country in August 2017 after he was accused of helping his brother flee earlier. He told Human Rights Watch, “Men started to come to the house and ask where I was. I started to move around and never sleep in the same place. If you are associated with someone from FOCODE, then you are a target.... I was a businessman, but I had to leave the country. Now I just sit around and wait for someone to give me beans and corn.”[71]

At least three refugees told Human Rights Watch that they felt they had no choice but to flee after they were perceived of being against the referendum because they had been accused of insulting the president or the ruling party.

One refugee from Bururi province explained, “I had made some jokes about Nkurunziza and I was accused of insulting the president and the ruling party. The men questioning me said the charges were very serious. As the Imbonerakure don’t tolerate this, I knew I could be killed.”[72]

Another refugee, who fled his home in Bujumbura Rural province, explained to Human Rights Watch that he quit the church where Nkurunziza worships because he “did not want to spend his time with criminals.” A few weeks after he stopped attending the church, the Imbonerakure came to his home. “They asked me why I was not at church,” he said. “I said that I had been busy, but they said it meant that I was a traitor and that I had insulted Peter [Nkurunziza] and the party. They said it clearly, and I knew I had to leave.”[73]

Acknowledgments

This report was researched and written by Lewis Mudge, senior researcher in the Africa Division at Human Rights Watch, with significant support from other colleagues in the Africa Division. Ida Sawyer, Central Africa director in the Africa Division, and Babatunde Olugboji, deputy program director, edited the report. Clive Baldwin, senior legal advisor, provided legal review. Jean-Sébastien Sépulchre, coordinator in the Africa Division, provided additional editorial assistance. Fitzroy Hepkins, administrative manager, provided production assistance.