Summary

On May 21, 2017, police in Indonesia’s capital, Jakarta, raided the Atlantis gym and sauna, arresting 141 people, most of whom were gay or bisexual men. Ten were ultimately prosecuted under Indonesia’s pornography law. The Atlantis was not just a “gay club,” but a public health outreach center—a well-known hub for HIV education, testing, and counseling among men who have sex with men (MSM).

In the media, the raid was just the latest “anti-LGBT incident.” Since early 2016, many senior government officials had made that four-letter acronym a toxic symbol, the focus of an unprecedented rhetorical attack on Indonesian sexual and gender minorities. Officials used the letters to signal a group of societal outsiders; some even construed the visibility of “LGBT” as threat to the Indonesian nation itself.

There were at least six similar raids on private spaces in 2017, and more in early 2018. Each followed a pattern: vigilantism against lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender (LGBT) people provided social sanction for abusive police action; vague and discriminatory provisions in the law empowered authorities to violate the privacy rights of people presumed to be LGBT; the venues raided were places where LGBT Indonesians believed they could gather safely and privately, to learn about health issues, make friends, and build community. All told, police in Indonesia apprehended at least 300 LGBT people in 2017 alone because of their sexual orientation and gender identity—a spike from previous years and the highest such number ever recorded in Indonesia. The pattern of these raids suggests a systematic crackdown on LGBT rights, and their impact portends a public health crisis.

This report—based largely on 48 in-depth interviews in Java, Kalimantan, and Sumatra in 2017 with victims and witnesses, health workers, and activists—updates a Human Rights Watch report from August 2016 that documented the sharp rise in anti-LGBT attacks and rhetoric that began in January of that year. It provides an account of major incidents between November 2016 and March 2018 and examines the far-reaching impact of this anti-LGBT “moral panic” on the lives of sexual and gender minorities and the serious consequences for public health in the country.

While Indonesia has made inroads on the spread of HIV in a number of areas, HIV rates among MSM have increased five-fold since 2007, according to government and UNAIDS data. And while the majority of new HIV infections in Indonesia occur through heterosexual transmission, one-third of new infections occur in MSM. In major urban centers such as Denpasar in Bali and Jakarta, the MSM epidemic is even more prevalent with nearly one in three MSM infected with HIV. One particularly troubling aspect of the anti-LGBT panic, detailed below, is that public health outreach to such populations has become far more difficult, making wider spread of the disease more likely.

***

As noted above, conditions in Indonesia today can be traced to a nationwide anti-LGBT “moral panic” that began in early 2016. Over the course of several weeks in January and February 2016, anti-LGBT statements ranging from the absurd to the apocalyptic echoed through Indonesia’s media: at a maternal health seminar, a mayor warned young mothers off instant noodles—their time and attention, he said, should be given instead to nutritious cooking and teaching their children how not to be gay. The National Child Protection Commission issued a decree against “gay propaganda” and called for censorship. The national professional association for psychiatrists proclaimed same-sex sexual orientation and transgender identities as “mental illnesses.” The Nahdlatul Ulama, the country’s largest Muslim organization, called for criminal penalties for LGBT behavior and activism, and forced “rehabilitation” for LGBT people. And perhaps most perniciously, Indonesia’s minister of defense labeled LGBT rights activism a proxy war on the nation led by outsiders:

It's dangerous as we can't see who our foes are, but out of the blue everyone is brainwashed—now the [LGBT] community is demanding more freedom, it really is a threat…. In a nuclear war, if a bomb is dropped over Jakarta, Semarang will not be affected—but in a proxy war, everything we know could disappear in an instant—it's dangerous.

Veteran Indonesia expert Professor Edward Aspinall observed that Indonesia’s anti-LGBT crisis, “[is] one of those issues in this age of very rapid electronic media and social media where it really just spiraled to become this major moral panic to engulf the country.”

That outpouring of intolerance sparked new legislative proposals—by independent groups as well as lawmakers—to censor LGBT content in the media, end “LGBT campaigning” (without defining it), and criminalize adult consensual same-sex conduct. One of the most high-profile efforts in this regard took place at the Constitutional Court. In July 2016, petitioners led by the Family Love Alliance, an anti-LGBT coalition based in the city of Bogor, petitioned the Constitutional Court to effectively amend clauses in Indonesia’s criminal code on adultery, rape, and sex with a minor to criminalize all sex outside of marriage and all sex between persons of the same sex, regardless of age. While the petition failed, the battle has now moved into the house of representatives with similar proposals put forward by various parties. The government representative on the parliamentary task force on revising the criminal code has expressed opposition to outright criminalization of same-sex conduct. However, sex outside of marriage remains a criminal offense in the draft, and the speaker of the house of representatives has stated publicly that, “We must not fear or succumb to outside pressure and threats that banning LGBT practices will decrease foreign tourism. What we must prioritize is the safety of nation's future, particularly the safety of our youth from influences that go against norms, culture and religion.”

The anti-LGBT moral panic simultaneously spilled over from government institutions into wider society. In January 2018, the Twitter feed of the Indonesian air force went on a bizarre and hateful anti-LGBT screed. The air force has failed to publicly provide any details about the incident or to confirm or deny its support for such discriminatory invective. There were also social media protests and threats of boycotts against Starbucks in Indonesia for its CEO’s 2013 statement in support of same-sex marriage, and Unilever for its distribution of a rainbow ice cream product.

In perhaps the most telling indicator of how politically superficial but socially profound the anti-LGBT campaign had been, opinion data trends showed peculiar results. A 2016 opinion poll showed that 26 percent of Indonesians disliked LGBT people—making them the most disliked group in the country, overtaking the historical placeholders: communists and Jewish people. A similar poll in 2017 showed an even greater proportion of Indonesians responding negatively to questions about LGBT people. Additionally, the survey found that more Indonesians feared LGBT people than could define the acronym or the population it referred to.

A handful of senior officials have made statements or taken initial steps in support of some protections for LGBT people’s basic rights. In September 2017, in response to a request from the National Commission on Human Rights, the Attorney General’s Office (AGO) announced that it had rescinded a job notice that barred LGBT applicants. However, the AGO undermined that defense of LGBT rights by suggesting homosexuality was a “mental illness.” In February 2018, national police chief Tito Karnavian ordered an investigation into a series of raids on transgender-owned beauty parlors in Aceh province, resulting in the local police apologizing. The chief who oversaw the raids was later demoted. Most importantly, in October 2016, President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo publicly defended the rights and dignity of LGBT Indonesians.

These statements and actions, however, have not been followed with more systematic efforts to stop discrimination and abuse. President Jokowi, for example, has yet to take any steps to penalize government officials implicated in fomenting anti-LGBT discrimination, and his statements have not deterred senior government officials from making anti-LGBT statements or stopped police from conducting discriminatory raids on LGBT venues. In December 2017, Religious Affairs Minister Lukman Hakim Saifuddin called for LGBT people to be “nurtured, not shunned.” However, Saifuddin’s tolerance came with limits: he called for “religious adherents” to “embrace and nurture” LGBT people by reacquainting them with religious teaching, while in the same statement asserting that, “there is no religion that tolerates LGBT action.”

Meanwhile, throughout 2017 police raided saunas, night clubs, hotel rooms, hair salons, and private homes on suspicion that LGBT people were inside. The raids sometimes were preceded by police surveillance of social media accounts to discover an event’s location, and at times featured officers marching unclothed detainees in front of the media, public humiliation, and moralizing presentations of condoms as evidence of illegal behavior.

The vitriolic anti-LGBT rhetoric from public officials that began in early 2016 effectively granted social sanction and political cover to violence and discrimination—carried out by both citizen vigilantes and state authorities. The unabated stream of hateful anti-LGBT messaging from government officials and institutions has also contributed to a public health crisis.

Most new HIV infections in Indonesia occur through heterosexual transmission. However, one-third of new infections occur in MSM and HIV rates in that population have spiked in recent years. Abusive and discriminatory police actions including raids on private spaces and the use of condoms as evidence of purported crimes has harmed HIV education and outreach services by instilling fear among sexual and gender minority communities who urgently need such services. Meanwhile, public health data show that HIV prevalence rates among MSM are increasing dramatically. Moreover, while the prevalence of HIV in other key affected populations (KAPs) has largely remained stable, the prevalence of HIV among MSM has increased significantly and rapidly—with 25 percent of MSM infected with HIV in 2015 compared to only 8.5 percent in 2011 and 5 percent in 2007. HIV prevalence among transgender women (waria) was reported at 22 percent in 2011 and 2015.

The Indonesian government’s failure to protect the rights of LGBT people represents a betrayal of fundamental human rights obligations. The crisis is also isolating Indonesia from its neighbors and attracting broader international opprobrium.

ASEAN Parliamentarians for Human Rights in January 2018 reacted to the anti-LGBT crisis by warning Indonesia of its “blatant violation of all Indonesians’ right to privacy and their fundamental liberties.” After a February 2018 visit to Indonesia, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights noted that “LGBTI Indonesians already face increasing stigma, threats and intimidation” and said: “The hateful rhetoric against this community that is being cultivated seemingly for cynical political purposes will only deepen their suffering and create unnecessary divisions.”

In July 2017, Indonesia indicated that it would reject all recommendations aimed to protect the rights of LGBT people at its Universal Periodic Review (UPR), the process in which every United Nations member state has its human rights record reviewed every four years. However, in September the government announced it would accept proposals to “take further steps to ensure a safe and enabling environment for all human rights defenders,” including LGBT activists. It also committed to implement the rights to freedom of expression, association, and peaceful assembly, and give priority to equality and nondiscrimination—including for LGBT people. Government health authorities have made similar pledges to eliminate human rights-based barriers to equitable access to HIV services. Given the government’s track record on this issue so far, implementation will be key.

As a first step, the police should halt all raids on private spaces, investigate those that have taken place, and punish the perpetrators and their chain of command. Police should instead be instructed to protect gatherings of sexual and gender minorities from attack by vigilantes and militant Islamist groups.

Indonesia’s laws need to be adjusted as well. The government should amend the anti-pornography law, which currently construes same-sex conduct as “deviant.” The government should make it clear to parliamentarians who propose criminalizing sex outside of marriage and same-sex conduct that such measures violate the constitution and Indonesia’s international human rights obligations.

The courage to confront the anti-LGBT moral panic should come from the highest ranks of Indonesian government. Indeed, it was President Jokowi himself who said that “the police must act” against any moves by bigoted groups or individuals to harm LGBT people or deny them their rights, and that “there should be no discrimination against anyone.” He needs to take further action on this pledge, including by immediately ordering an end to police raids that unlawfully target LGBT people, investigating the raids of 2017 and 2018, and dissolving any regional and local police units dedicated to targeting LGBT people.

Methodology

Human Rights Watch conducted research for this report throughout 2017, including 48 in-depth interviews with sexual and gender minorities, HIV outreach workers, and human rights activists in Java, including in the cities of Jakarta, Surabaya, Bogor, and Yogyakarta; in Kalimantan, including in Banjarmasin, Pontianak, Amuntai, and Barabai; and in Sumatra, including in Medan.

We conducted interviews in safe locations, sometimes far away from the interviewee’s home neighborhood or city, and the names of nearly all LGBT individuals in this report are pseudonyms. In some cases, we have withheld the location of interviews and other potentially identifying characteristics of interviewees for security purposes. Interviews were conducted in English and in Bahasa Indonesia, with simultaneous English interpretation when necessary. Interviewees were informed how the information gathered would be used and told that they could decline the interview or terminate it at any point. Reimbursement ranging from US$1 to $10 was paid for transportation costs, depending on the distance the individual had traveled. No other payments were made to interviewees.

Our accounts of specific raids on gatherings are based on multiple interviews with participants and witnesses to the specific incident or, as indicated, on secondary sources that we cross-checked with activists and witnesses directly involved with the incidents.

Throughout 2016 and 2017, Human Rights Watch engaged Indonesian government officials in a series of meetings and letters, as described in our 2016 report, “These Political Games Ruin Our Lives.” We have included some of the relevant correspondence with government officials, including letters to the minister of health and chief of police, as annexes to this report; other correspondence is featured as an annex to our 2016 report.

I. The 2016 “LGBT Crisis”

[T]he “LGBT crisis” is only indirectly about children or Islam. It is really about national belonging, about who will have a place at the table in Indonesia’s evolving civil society. If we read what are now hundreds of pages of anti-LGBT statements from the first months of 2016, certain key phrases recur: above all, variations of the claim that being LGBT does not fit “our national culture.”

—Tom Boellstorff, “Against State Straightism,” March 2016[1]

Indonesia’s Anti-LGBT Moral Panic

Prior to January 2016, many sexual and gender minorities across Indonesia lived with a mix of tolerance and prejudice. While waria—loosely translated as transgender women[2]—have long been a highly visible part of Indonesian social life and cultural fabric, many others found safety in discretion: many LGBT people chose to live without publicly disclosing their sexual orientation or gender identity as a means to protect themselves from discrimination and violence.

Indonesian LGBT people and civil society groups had endured sporadic hateful rhetoric and violent attacks over the preceding three decades,[3] including during the Suharto dictatorship from 1966 to 1998 and in the first decade of post-authoritarian rule. However, those incidents were isolated and did not hinder LGBT people from gaining increasing recognition as part of Indonesia’s pluralistic society. Nongovernmental organizations focusing on gender, sexuality, health, and human rights were able to register; university professors taught courses that featured discussions of homosexuality; and activists organized public and private events about LGBT rights issues.[4]

No national laws specifically protected LGBT against discrimination, but the central government had never criminalized same-sex behavior. And while some national laws—such as the 2008 Law on Pornography—contained discriminatory anti-LGBT clauses, they had never been used to target LGBT people. That changed in 2016 when the rights of Indonesian sexual and gender minorities came under unprecedented attack.

Beginning in January 2016, politicians and government officials began making anti-LGBT public comments, and, once joined by state commissions, militant Islamists, and mainstream religious organizations, the rhetoric grew into a cascade of threats and vitriol against Indonesian sexual and gender minorities. That outpouring of intolerance was accompanied by court cases and legislative proposals intended to prompt information ministry censorship of LGBT content in the media,[5] police and societal crackdowns on undefined “LGBT campaigning,” and criminalization of adult consensual same-sex conduct.[6]

During January and February 2016, anti-LGBT statements ranging from the absurd to the apocalyptic echoed through Indonesia’s media: at a maternal health seminar, a mayor warned young mothers off instant noodles—their time and attention, he said, should be given instead to nutritious cooking and teaching their children how not to be gay. The National Child Protection Commission issued a decree against “gay propaganda” and called for censorship.[7] The national professional association for psychiatrists proclaimed same-sex sexual orientation and transgender identities as “mental illnesses.”[8] The country’s largest Muslim organization called for criminalization of LGBT behaviors and activism, and forced “rehabilitation” for LGBT people.

Most perniciously, Indonesia’s minister of defense labeled LGBT rights activism a proxy war on the nation led by outsiders:

It's dangerous as we can't see who our foes are, but out of the blue everyone is brainwashed—now the [LGBT] community is demanding more freedom, it really is a threat…. In a nuclear war, if a bomb is dropped over Jakarta, Semarang will not be affected—but in a proxy war, everything we know could disappear in an instant—it's dangerous.[9]

What began as public condemnation quickly grew into calls for criminalization and “cures.” One United Nations official said the crisis had “touched a bedrock of huge homophobia.”[10]

In an August 2016 report, Human Rights Watch documented the rise in anti-LGBT rhetoric earlier in the year as well as threats and violent attacks on LGBT organizations, activists, and individuals, primarily by militant Islamists. LGBT people told Human Rights Watch that the increased anti-LGBT rhetoric also fueled heightened hostility from family members and neighbors. In Pontianak, an LGBT rights activist said that 2015 was the last time he could organize a “Miss Waria” contest, a concern echoed by transgender activists across conservative areas in Sumatra, Java, and Kalimantan in interviews with Human Rights Watch.[11]

Anti-LGBT sentiment had previously existed in some pockets in Indonesia. In past decades, militant Islamists had attacked LGBT public activities, in several instances breaking-up or otherwise forcing the cancellation of scheduled events.[12] Even before 2016, LGBT rights activists had come to understand that they could not trust police to protect them when they face orchestrated intimidation or violence. As a gay HIV outreach worker in Jakarta described to Human Rights Watch in November 2017: “The major shift since 2016 is that the media has completely discredited LGBT people—a total character assassination.”[13]

The international nongovernmental group Frontline Defenders in a 2017 report documented attacks and death threats on LGBT human rights activists, and argued that “the government’s own crackdown on LGBT rights in 2016 emboldened those who want to terrorize human rights defenders into silence.”[14]

In a 2017 report, LBH Masyakarat, the Community Legal Aid Institute in Jakarta, analyzed more than 300 media stories on LGBT issues from 70 different outlets.[15] The report concluded that, “misconceptions about LGBT people seem to have found more room in 2016. The traction of views that LGBT people are a threat to the nation was made possible by the accumulation of misconceptions relating to LGBT people.” Their research found that anti-LGBT stigma perpetuated by the media ranged “from the common view that LGBT people are the contemporary projection of Sodom and Gomorrah to the use of LGBT stigma as a form of proxy war in Indonesia.” LBH Masyarakat observed:

Social media, which at first was a free space for LGBT people to express themselves without worrying about normative restrictions, [has] become a restricted space. LGBT people are marginalized in society and now also isolated from room for free expression online. Considering that social media has been used by HIV and LGBT activists to deliver education and outreach, attempts to block websites and application will affect the right of LGBT citizens to access adequate information about Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity and Expression and healthy reproduction.[16]

“When the media rises up against LGBT, I fear for my life,” a gay HIV outreach worker in Jakarta told Human Rights Watch. [17]

And the fear has not abated. “The suspicion from any neighbor that we are gay can put us in real danger,” said Panuta, a 25-year-old gay man who works as an HIV outreach worker for MSM in Jakarta. “Whenever a group of my friends gets together now, we’re afraid of neighbors snooping and calling the religious groups or the police and saying we are having a sex party—even if we are not,” he said. “Even for me, I always have condom stocks at my apartment because of my job, so I get afraid if I have friends over and we are watching TV and we start laughing. I worry: are we laughing too loud? Will a neighbor report us? Will the police find the condoms and accuse us of being gay or prostitutes?”[18]

Anti-LGBT advocacy by psychiatrists in particular appears to have persisted. On February 16, 2016, Dr. Fidiansjah, a psychiatrist and the director of mental health at the Ministry of Health, stated during a live television program that homosexuality is a “psychiatric disorder.”[19] Three days later, on February 19, the Indonesian Psychiatrists Association (PDSKJI), where Fidiansjah is a board member, issued a notice stating that “people who are homosexual and bisexual are categorized as people with psychiatric problems.”[20]

According to a March 24 Jakarta Post report, Minister of Health Nila Moeloek said she would investigate Dr. Fidiansjah’s comment. During a meeting with Human Rights Watch on April 12, however, the minister denied any knowledge of Dr. Fidiansjah’s comments.[21]

Dr. Fidiansjah, now serving as the Director of Prevention and Control of Mental Health and Nutrition Problems at the Ministry of Health, told reporters in January 2018 that “LGBT is a mental health issue” and that the health ministry’s job is to maintain “norms, religion, and culture.”[22] Human Rights Watch wrote to health minister Moeloek to seek clarity on February 9th, 2018. At the time of this report’s publication, we had received no response.[23]

Indonesia’s Worsening MSM HIV Epidemic

In recent years, Indonesia’s HIV epidemic has been significantly worsening. With nearly 48,000 new infections a year, UNAIDS in 2012 categorized Indonesia as one of the 9 countries among 186 countries reported with an alarming rise in new infections despite increasing investments from donors and the government for its HIV response. [24] With the exception of the provinces of Papua and West Papua, where the epidemic is even worse, Indonesia has a “concentrated” HIV epidemic, meaning it is composed of multiple intertwined epidemics in different “key affected populations” (KAPs).[25]

According to government and UNAIDS data, in 2017, Indonesia recorded 46,357 new HIV infections, with the highest number of new infections occurring in three groups: non-key affected population females[26] (33 percent of new infections); male clients of sex workers (24.5 percent), and MSM (23.5 percent).

While most new HIV infections in Indonesia occur through heterosexual transmission, one-third of new infections occur in MSM. Moreover, while the prevalence of HIV in other KAPs has largely remained stable, the prevalence of HIV among MSM has increased significantly and rapidly with 25 percent of MSM infected with HIV in 2015[27] compared to only 8.5 percent in 2011[28] and 5 percent in 2007.[29] In major urban centers such as Denpasar in Bali and Jakarta, the MSM epidemic is even more prevalent with nearly one in three MSM infected with HIV.[30] HIV prevalence among waria was reported at 22 percent in 2011[31] and 2015.[32]

Against this backdrop of a worsening epidemic among MSM, data appear to show complex trends: an increasing awareness of HIV among MSM with 65 percent demonstrating comprehensive HIV knowledge in 2015 compared to only 25 percent in 2011. Similar positive trends in protection measures are observed with condom use, with 79 percent of MSM reporting condom use in the last sexual encounter in 2015 compared to 60 percent in 2011. [33] These data suggest that outreach by nongovernmental groups to MSM communities has been successful. However, these data also suggest that MSM still face significant barriers to accessing care.

Only about 50 percent of MSM have ever tested for HIV, and out of those infected and needing antiretroviral drugs (ARV) only 9 percent are currently taking the medications.[34] In a 2015 review, the National AIDS Commission wrote that one of the impediments to curbing Indonesia’s HIV epidemic was: “Limited attention and resource allocation for programming to key population sub-groups among whom epidemic growth is currently the most robust – MSM in particular.”[35] The National AIDS Commission report also noted that: “To date, national program efforts directed to MSM and clients of sex workers have been sporadic, unfocused and grossly under-funded.”[36] A 2017 public health study of MSM in Yogyakarta found that,

In addition to concealing their sexual orientation and avoiding discussions about health issues or attendance to health care provision…cultural norms and perspectives against same-sex relationships or marriage [influenced] their decision to move to Yogyakarta where they developed and/or engaged in MSM social networks…. [which] supported their engagement in HIV-risky sexual behaviors.[37]

According to UNAIDS-Indonesia:

Many factors may have contributed to the slow progress of HIV responses in Indonesia, but the biggest one is the widespread stigma and discrimination against people living with HIV (PLHIV). Despite the progress that the government of Indonesia has achieved over the years in terms of HIV-related services provision, stigma and discrimination have discouraged people from accessing those services, and contributed to PLHIV’s fearing of losing their jobs, being discriminated at workplaces or schools, or evicted from their houses due to their HIV status.[38]

UNAIDS officials also told Human Rights Watch that, “Hostile policy and programmatic approaches against key affected populations (KAPs) of people who inject drugs (PWID), female sex workers (FSW), men who have sex with men (MSM), and transgender women have worsened the HIV responses even more.” This includes, “the recent backlashes against LGBT people have forced these key populations to go underground, impeding HIV outreach services for them and, most of all, denying them their basic right to health.”[39]

Mathematical modeling conducted by the Ministry of Health in 2014 indicated that the number of annual new HIV infections will continue to grow unless further efforts are made to expand program coverage and intervention effectiveness, especially with regard to programs directed towards MSM.[40]

Despite these findings by the government, access to services remain difficult for many MSM. As documented in this report, amid rising intolerance, anti-LGBT moral panic, and increasingly unclear legal protections, outreach workers struggle to salvage their networks of MSM. Access to government-provided health insurance, which is supposedly available to all Indonesian citizens and is a key driver of retention in care, remains difficult for many MSM because it is based on family-unit registration, and many do not want to reveal their identity or HIV status to their family. [41] For example, as Dr. Sandeep Nanwani and Clara Siagian wrote in 2017:

Getting a [national insurance card] is in itself a laborious and difficult task for many Indonesians. For people like Noni it is nearly impossible. A [national insurance card] can only be obtained through civil registration – either through birth registration or by being included on an official Family Card that lists a permanent physical address. This is a requirement that many waria, vagrants, and street children cannot meet because they have been estranged from their families.[42]

Prevention efforts—such as donor-funded, organization-led outreach—are not sufficiently linked to care, which is often delivered in government-run clinics. In other words, while education and awareness regarding HIV among a stigmatized population such as MSM may be high, fear of non-confidentiality, rejection, and discrimination when attending government clinics remains a barrier to accessing care services. This can create a gulf between MSM and mainstream HIV care—in particular when government officials, politicians, and powerful religious institutions drive stigma against the population—and portends a risky future as Indonesia’s economic growth indicates that it may graduate out of donor funding eligibility in coming years.[43]

Disturbing HIV Policy Shifts

Historically, as part of its response to the AIDS epidemic, the Indonesian government engaged with LGBT and MSM-focused civil society groups. This practice subsequently changed, in part due to pressure from religious organizations. Veteran HIV and LGBT rights activist Dede Oetomo wrote in 1996:

Initially at the beginning of the AIDS epidemic, the Indonesian Ministry of Health was quite supportive…. But they quickly regretted what they had done because they were blasted by…Muslim religious leaders, by some of the Christian leaders and by the middle classes. Increasingly we lost the support of the Indonesian Ministry of Health. It's got to the point where the Indonesian National AIDS Commission has informally discouraged funding agencies from funding gay-related projects.[44]

Significant shifts in HIV policy introduced in 2016 have left NGO workers and activists anxious about potential future difficulties in implementing HIV programs. The coordination and implementation of even largely international donor-funded HIV programs now rest with local governments—exposing LGBT and MSM communities and networks to possible neglect and hostility.

Dissolution of the National AIDS Commission

In 2016, President Jokowi issued a decree dissolving the National AIDS Commission (NAC). Founded in 2004, independent of the Ministry of Health, the NAC functioned as a key coordinating body connecting civil service organizations to state services. With the dissolution of the NAC, HIV-related activities are coordinated by local governments. In the absence of the NAC, non-government and community-based organizations now need to obtain funding and services from local authorities themselves. This places a heavy burden on underfunded community healthcare workers responsible for coordinating patient care. Local officials, often with no clear oversight, are left with the task of disbursing funds to organizations working with at-risk populations (KAPs) at their sole discretion. [45] While it is not yet clear what the dissolution of the NAC will mean to the running of HIV programs, activists and NGOs fear that with no programmatic and political support from the NAC, they may face difficulties in implementing programs as they are forced to negotiate programs with inefficient and sometimes hostile local governments.

MSM Absent from Minimum Health Standards

Since 2004, Indonesia’s health system has been decentralized. One aspect of this structure is that local health systems are guided and regulated by minimum standards set by the Ministry of Health in Jakarta. In 2016, in an effort to improve local government response to the HIV epidemic, the Ministry of Health issued new “Minimum Standards” for health services. The Minimum Standards are a set of basic care packages that local governments must deliver to its constituents, including basic antenatal care, TB services, and HIV care. For the first time, in 2016 the standards included HIV healthcare service delivery across Indonesia.

The HIV section of the 2016 standards omit any explicit mention of MSM, stating only that HIV outreach should target those “at risk” of HIV. With MSM not included on the list of those at risk, public health workers and advocates believe it will be more difficult to receive funding and manage operations related to MSM outreach education, testing, and treatment access. Effective outreach requires close coordination with local health centers who are managed by district governments. With MSM outreach not explicitly named in the minimal standards, district governments have the discretion to no longer fund MSM outreach programs.[46]

For example, NGOs seeking to run mobile Voluntary Counseling and Testing (VCT) need a letter from district authorities before they can enter malls, nightclubs, or other spaces with testing kits. Previously, such credentials were obtained from the NAC. Under the new format, such NGOs will be at the mercy of local government officials without clear guidelines directing officials to issue the credentials.

Government Commitments to the Global Fund

In 2017, the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria made available to Indonesia US$2.7 million of matching funds under its “Catalytic Investment” program. The funds are earmarked to support the removal of human rights-related barriers to HIV services.[47]

In May 2017, Indonesia’s Country Coordinating Mechanism—a committee that submits the country’s Global Fund application and includes representatives from government, the private sector, technical partners, civil society, and communities living with the diseases[48] —submitted a funding request to the Global Fund that included HIV programming for MSM. The application noted: “Recent epidemiological modeling estimates that about 63% of new HIV infections in Indonesia are among key affected populations (KAPs),” adding that in all KAPs except MSM, HIV prevalence has stabilized and possibly begun to decrease. The application noted “contextual factors” driving the disparity included “persistent stigma and discrimination against key populations” and a “deteriorating enabling environment.” It explained: “The deteriorating environment is primarily evidenced by a widespread crackdown on sex work and sex workers, [and] the emergence of a government-endorsed anti-LGBT movement.” In its pursuit of the Global Funds Catalytic Investment matching funds, the Country Coordinating Mechanism described the human rights-related activities the government and partners[49] pledged to undertake with the funding:

The interventions aim to reduce stigma and discrimination among MSM and transgender people; improve legal literacy (also for MSM and transgender people); and improve laws, regulations and policies relating to HIV and HIV/TB.[50]

II. Anti-LGBT Raids and Legal Changes in 2017

Many MSM tell me that the anti-LGBT political crisis is driving them crazy. We are scared in public and now there is no privacy.[51]

—HIV outreach worker in Jakarta, November 2017

Police in Indonesia apprehended at least 300 LGBT people in 2017—a spike from previous years, where arrests were sporadic, often targeted sexual and gender minorities for reasons other than their sexual orientation or gender identity (i.e. their participation in street begging or sex work) and never resulted in prosecution. The raids continued in early 2018.

In the wake of the onslaught of anti-LGBT rhetoric from public officials in early 2016, vigilantes and militant Islamists carried out threats and violent attacks on LGBT NGOs, activists, and individuals. In some cases, the threats and violence occurred in the presence, and with the tacit consent, of government officials or security forces. Later in 2016, beginning with a raid on a private residence in Jakarta, and carrying into 2017 with multiple raids on homes and other private venues, police became active participants in the anti-LGBT crackdown.

The pattern of the raids suggests an intensifying government crackdown and portends a public health crisis. Some raids were initiated by neighbors or militant Islamist groups who suspected individuals in their vicinity were gay or transgender. Others were undertaken by police units that detected gatherings of sexual and gender minorities via social media announcements or discussions, such as WhatsApp screen shots.

Raids and Arbitrary Arrests

November 2016: Militant Islamists, Police Raid Private Jakarta Home

The Islamic Defenders Front (FPI)[52] claimed its self-proclaimed “investigative unit” tipped off police to conduct a “successful raid” on November 26, 2016 at a private home in South Jakarta. Police apprehended and detained 13 men for at least 24 hours, releasing them only after determining that no laws had been broken during the gathering.[53] The FPI’s social media accounts posted photographs of police taking men in for questioning, and local media reported that mobile phones and HIV/AIDS medication were confiscated from the premises.[54]

January 2017: Police Cancel Transgender Event, Temporarily Detain Hundreds

On January 19, 2017, police in South Sulawesi province obstructed a group of 600 waria and bugis (transgender and gender non-conforming people) from participating in a planned sports and cultural event by blocking off the site of the event. Police then detained them for several hours in a recreation hall in Soppeng. Media reports indicate police acted on the request of the semi-official Indonesia Ulama Council, which said the event was “not in line with religious values.”[55]

April 2017: Police Raid Surabaya Hotel Gathering, Force HIV Tests

Police in Surabaya, acting on tip-offs from neighbors, carried out a midnight raid on the Oval Hotel where 14 men had gathered on the evening of April 30, 2017. Police detained the group while confiscating condoms, mobile phones, and a flash drive that allegedly contained pornographic videos, among other items.[56] On May 1, police informed the media that all 14 men underwent tests for sexually transmitted infection, including a rapid test for HIV, and that five had tested HIV positive.[57] The police indicated that eight of the men were detained on suspicion of violating the Law on Pornography, and that two of them would be charged with organizing the event and providing pornography—offenses carrying prison terms of up to 15 years.

In September 2017, the Surabaya court sentenced seven of them to between 18 months and 30 months in prison, ruling that they were involved in pornographic acts. Chief Justice Unggul Warso Murti determined that two of the seven men were proven to have “organized the gay party with Blackberry messenger advertisements.” The court found that the five others were only dancing and taking part in the “gay party.” [58] The penalties imposed were considerably harsher than the three-month jail term imposed on the eighth man for criminal possession of a weapon.[59]

May 2017: Men Publicly Flogged for Private, Consensual Same-Sex Conduct

On May 23, Sharia (Islamic law) authorities in Aceh province flogged two men 83 times in front of a crowd of thousands.

The two men had been apprehended on March 28in Banda Aceh, the provincial capital, by unidentified vigilantes who forcibly entered one of the men’s apartment and then forcibly surrendered them to police for allegedly having same-sex relations.[60] A Sharia court convicted them of sodomy on May 17. During their trial, the prosecutor recommended 80 lashes, 20 shy of the maximum the law permits because the men were young and admitted their guilt.[61] While Aceh’s Sharia courts have enforced public flogging before, this was the first time that courts had sentenced people to be flogged for same-sex conduct.[62]

May 2017: Police Raid “Gay Spa,” Arrest More Than 100

On May 21, police raided the Atlantis Gym, a sauna frequented by gay men in Jakarta, arrested 141 people, and charged 10 for holding an alleged sex party. Officers allegedly took photos of some of the naked men,[63] and paraded the suspects naked in front of media and interrogated them still unclothed, which the police deny.[64] The official Indonesian Human Rights Commission sent a letter to the police chastising them for violating the suspects’ privacy and dignity rights.[65] Six Indonesian human rights groups wrote to the police criticizing them for “inhuman and degrading” treatment during the arrests.[66] The photographs of the naked men appeared on social media within hours of the raid.[67]

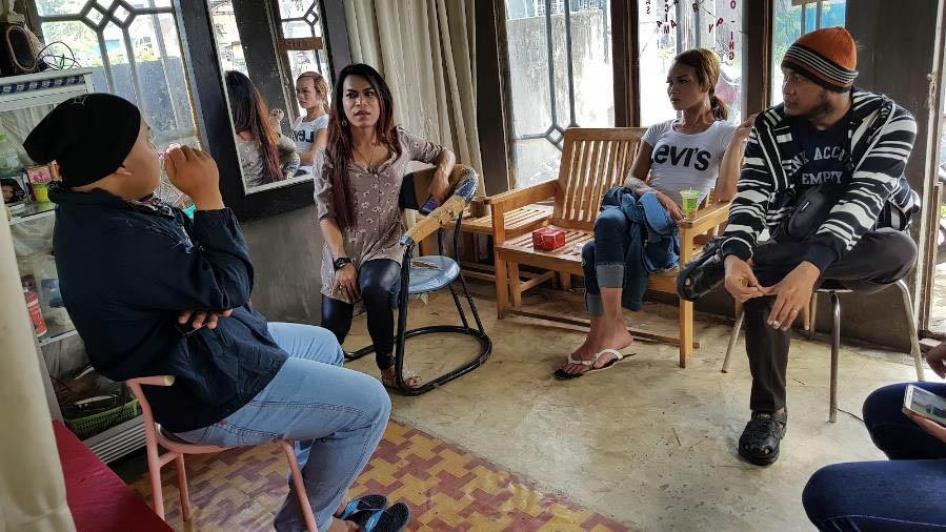

June 2017: Police Apprehend “Suspected Lesbians,” Post Video Online

On June 8, Tribun News posted a video of police in Medan interviewing and harassing five women suspected of being lesbians.[68] The clip features a government official, Rukun Tangga, who had visited the house and reported that he had allegedly seen two young women kissing. He reported that to the village head, as well as to the military officer in the village. That prompted the officials and other neighbors to force the five young women to go to the village office. The officials ordered the women to vacate their homes within three days.

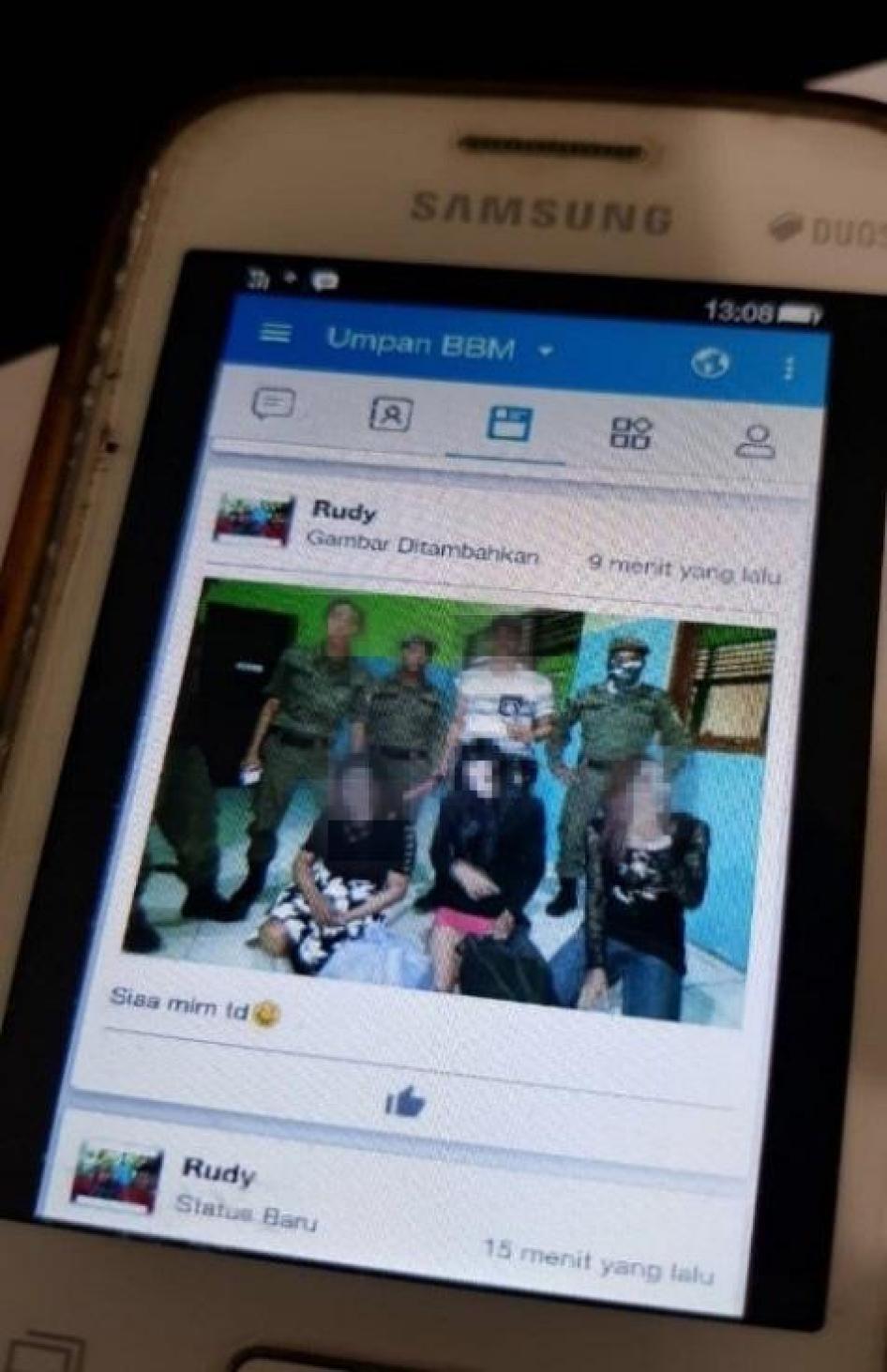

June 2017: Police Raid Public Park, Disperse and Arrest Waria

On the evening of June 26, 2017, in Barabai, a city in South Kalimantan province, approximately 200 waria gathered in a public park called Pagat. About 10:30 p.m., dozens of municipal police officers arrived in two large trucks equipped with megaphones, and instructed the waria to leave.[69] Officers arrested four waria and detained them at a public order station in Barabai where, three detainees told Human Rights Watch, police forced them to run and do pushups in an apparent effort to humiliate them. Police took photos and videos of the detainees and posted the content on social media. One of those images included a shot of three of the four detainees squatting at the feet of four officials.[70]

One of the detainees, Yupi K., a 28-year-old waria, said: “The charge was not clear. It was probably disturbing public order. What did we disturb? We just gathered on the second day of the Idul Fitri holiday, having our annual reunion.”[71] The authorities’ social media postings caused future humiliation for Yupi, whose salon customers asked her about the incident and whether she was involved in prostitution—something other waria have experienced as well.[72] Bambi S., a 44-year-old waria salon owner who police also arrested at Pagat, said her customers notified her that a video of police apprehending her that night had been uploaded to YouTube.[73] One of the waria featured in the video told Human Rights Watch:

Several days after the arrest, one of my regular customers came to my salon and told me about the video and the photo. It was humiliating. I was scared that people here might recognized me. I might further persecution because my face had been shown publicly.[74]

The commander of the municipal police later stated publicly that authorities had conducted the sweep on the request of the Indonesian Ulema Council (MUI),[75] and relatives of staff at the Pagat park confirmed that they had received instructions from the MUI to rid the park of waria.[76]

September 2017: Police Arrest “Suspected Lesbians”

On September 2, police raided a residential compound that was home to 12 women in West Java province’s Tugu Jaya village. That raid was in response to complaints from local Islamic youth groups and religious leaders that the women’s cohabitation was “against the teachings of Islam.” Police demanded that the “suspected lesbians” immediately relocate from the area without providing any legal justification for the order, according to authorities.[77]

The police raid, led by the head of Tugu Jaya village, Sugandi Sigit, and the police commissioner, Saifuddin Ibrahim, resulted in the 12 women immediately vacating their homes and leaving the area. Mohammad Karim, the head of the neighborhood where the women lived in Tugu Jaya, sought to justify the raid by saying that the women were “unsettling the public.”[78] Sumantri, the head of the Cigombong district public order office that took part in the raids, said that police and government officials told the women that “their presence had created public disturbance in the area. We politely asked them to leave.”[79] A village official who asked not to be named told Human Rights Watch: “It’s not acceptable to have female couples living together. Some have short hair, acting as the males. Some have long hair, acting as the females. It’s against Sharia. It’s obscene.”[80]

Media reports indicate that in December 2017, authorities in a nearby village, acting on a tip from neighbors, apprehended a man and his waria partner. The police accused the two of having a sexual relationship, and demanded the waria leave her residence within two days and not return.[81]

October 2017: Police Raid “Gay Sauna,” Arrest More Than 50

On October 7, Jakarta police raided T1 Sauna, a club popular with gay men, arresting 58 people. Police released most of those men the same day but continued to detain five employees of the sauna—four men and a woman—and threatened to charge them with violating the Law on Pornography of 2008. Following the raid, in an apparent reaction to the criticism police faced following the May 2017 raid on the Atlantis night club, police spokesman Argo Yuwono told reporters: “We treated them well. They came out from the scene with proper clothes and their faces were covered.”[82]

January 2018: Police Raid West Java “Sex Party”

On January 13, police in Cianjur, West Java province, raided a private home where five men had gathered. Police told reporters these men were caught at a “sex party,” which violated the Law on Pornography with evidence that included condoms and lubricant.[83] Police indicated in media reports that they would charge the men under article 36 of the Law on Pornography, which imposes up to a 10-year sentence for “any person displaying himself or any other person in a public performance or display depicting nudity, sexual exploitation, coercion or other pornographic actions.” Several months earlier in May 2017, West Java Police Chief Anton Charliyan had announced the creation of a special anti-LGBT police task force in the province.[84] Human Rights Watch was not able to confirm that this task force was responsible for the January 2018 raid but the incident fits squarely within the reported mandate of the squad.[85]

January 2018: Waria Beauty Parlors in Aceh raided

On January 27, police and Sharia police jointly raided five hair salons that employed waria. Police arrested a dozen clients and employees, forced them to remove their shirts, cut their hair in public, and detained them for 72 hours. Immediately following these raids, North Aceh Police Chief Untung Sangaji said, as captured in a phone recording posted to YouTube: “Our ulama [Muslim scholars] disagree with this disease. [This disease] is spreading. It’s inhumane if Untung Sangaji is to tolerate these sissy garbage.”

He initially threatened to take action not only against waria across the province, but also any visitors to their hair salons. On January 30, Gen. Tito Karnavian, Indonesia’s national police chief, told reporters that he had ordered an investigation into Sangaji’s behavior. On January 31, after the chastisement from Jakarta, Sangaji had issued a lukewarm apology to, “parties who felt offended with what I did.”[86] On March 9, Indonesia’s National Police removed Sangaji, transferring him to be deputy director of the water police in Medan, North Sumatra.[87]

An Amnesty International investigation into the police raids and subsequent fall-out found that the waria’s humiliation did not end when the police released them, but rather continued in their homes and communities. Some of the 12 who were apprehended by the police eventually fled Aceh due to fear of additional violence, humiliation by neighbors and family members, and loss of livelihood.[88]

March 2018: Neighbors Raid Same-Sex Couple in Jakarta

According to media reports, neighbors forcibly entered the rented room of two men in Jakarta on March 4, and alerted police to the presence of an “LGBT” couple in the neighborhood.[89] Police arrested the couple and took them to a government-run “rehabilitation” center in Jakarta.

|

Violence as a Fact of Life for Waria

Nigrat L., a 47-year-old waria outreach worker and community leader in Jakarta told Human Rights Watch: Violence will always be there—it always has been with us. It’s just part of our lives. It’s normal. We just know it as our bad luck that day, and maybe tomorrow too, or maybe tomorrow will be better. We line up on the streets at night so that’s where the violence is. It’s a violent place. We can’t go dancing and begging during the day because the police crackdown and arrest us, so we have to work at night. And the night is violent, it always has been.[90] Waria (an Indonesian term that loosely translates to “transgender women”) often migrate to urban areas at a young age. Largely excluded from formal employment, waria rely on sex work, busking, or hairdressing for income generation.[91] They face harassment from the police for busking and sex work as neither of the activities are tolerated by the state. Waria arriving in urban areas typically experience difficulties in obtaining identification documents, because getting documents requires a family card and waria are often disconnected from their families. This lack of documentation and registration puts waria in a condition where they have limited or no access to a variety of state services including health care. Spaces for waria to busk and participate in commercial sex have diminished significantly in recent years as a result of rapid urbanization and gentrification combined with the increasing policing of sex work.[92] Prevalence of sexual violence in settings of sex work where waria operate is also high as men who buy sex often have substance abuse disorders.[93] Waria often have little social support when they age and are often left abandoned in settings of extreme poverty and food insecurity.[94] Despite these challenges and the severe violence many face every day, waria look for strength and resilience by forming strong community bonds. They draw on these bonds to survive, whether it is for economic support or other forms of social protection. Through these strong communities, waria have demanded access to basic social welfare programs, and care for one another. Notably, waria have a tradition of providing similar care for other marginalized and vulnerable populations, such street children and MSM.[95] |

March 2018: Aceh Sharia police raid and arrest four for alleged same-sex conduct

In separate raids on March 12 and March 29, 2018 in Aceh’s capital, Banda Aceh, vigilantes detained two individuals each time and turned them over to the Sharia police. On March 12, vigilantes targeted a hair salon and detained a man and a transgender woman who worked there. The Sharia police claim to have found “evidence” of same-sex conduct, including condoms and “transaction money” from the transgender woman.[96] On March 29, vigilantes forcibly entered a private house and called the Sharia police, who arrested two male college students for allegedly having sex. The Sharia police seized condoms, cell phones, and a mattress as evidence of their alleged “crime.”[97] At the time of writing, all four detainees remained in Sharia police custody, pending trial in a religious court.

March 2018: Military officers publicly harass waria

On March 18, 2018, Indonesian military officers in Tanjung Pinang apprehended a group of waria on a public street and chastised them.[98] Military commander Lt. Col. Dandim Ari Suseno said the waria were given “pembinaan” (supervision, education) and asked to sign statements saying they would not engage in the “activity” again. The activity that Suseno mentioned was “meresahkan” (creating public unrest).[99]

Discriminatory Use of the 2008 Pornography Law

The raids on the clubs and parties this year have been a real education for our community. Most guys didn’t even know the pornography law existed before these incidents, and now they’re learning they can be arrested for being naked in a club or even a private party.[100]

—MSM HIV outreach worker in Jakarta, November 2017

In 2008, after several years of intense public debate about regulating morality, the Indonesian parliament passed the Law on Pornography. The FPI played a prominent role in encouraging policymakers to pass the law. The Prosperous Justice Party and MUI officially spearheaded the drafting and passage of the law. Human rights activists decried the law from the outset as being vague and discriminatory against women, LGBT people, and ethnic minorities.[101]

|

Defining Deviance The 2008 Law on Pornography defines “pornography” as: [P]ictures, sketches, illustrations, photos, writing, voice, sound, moving pictures, animation, cartoons, conversations, movements of the body, or other forms through a variety of communication media and/or performances in public, which contain obscenity or sexual exploitation, which violates the moral norms in society.[102] The law prohibits the “creation, dissemination or broadcasting of pornography containing deviant sexual intercourse,” which it defines to include: sex with corpses, sex with animals, oral sex, anal sex, lesbian sex, and male homosexual sex. Possessing pornography is a crime with maximum sentence of four years in jail; a sexually suggestive performance can receive a 12-year sentence. The law also invites members of the public to play a role in enforcing it, giving an opening for vigilantes to take the law into their own hands. A group of activists, including LGBT organizations, attempted to challenge the law in the Constitutional Court in 2009, but the court declined to review it.[103] |

On December 15, 2017, the North Jakarta District Court sentenced 10 men to between two and three years in prison for violating the Law on Pornography. Police had apprehended the 10, along with 131 others, during a raid on the Atlantis Gym, a sauna frequented by gay men in Jakarta, on May 21. The 10 were convicted based on allegations that they were naked at the time of the raid, citing the Law on Pornography’s prohibition on stripping performances. Most, but not all, were employees of the club—paid dancers.[104] This sentencing was the first prosecution under the Law on Pornography that specifically targeted gay men.

A Narrowly Averted Constitutional Crisis

On July 19, 2016, a group called the Family Love Alliance, led by professors from the Bogor Agricultural Institute, near Jakarta, filed a petition with Indonesia’s Constitutional Court asking the court to rule on the constitutionality of proposed changes to the criminal code. The petitioners sought amendments to the code’s articles on adultery (art. 284), rape (art. 285), and sex with a minor (art. 292). The changes would make all sex outside of marriage a crime; make the rape provisions in the criminal code gender-neutral (a request that is in line with international human rights standards); and amend the sex-with-a-minor provisions of the code, which outlaw sex between an adult and a minor of the same sex, to outlaw sex between two people of the same sex regardless of age.

In December 2017, the court dismissed the petition by a 5-4 vote following nearly 18 months of hearings. The bench rejected the petition on technical grounds, noting that the Constitutional Court is not the correct venue for creating new criminal laws. The commentary in the majority decision (see Appendix 3 for the full judgment) sheds light, however, on the judges’ view of the petition more broadly: “[I]t is out of proportion to place all the responsibility in arranging social phenomena—especially regulating behaviors considered ‘deviant’–to criminal policies only,” the majority decision reads, calling the petition “legally unsound.”

In analyzing the Family Love Alliance’s petition, the court warned against relying on criminal law as a way of addressing subjective social undesirability:

It is also apparent that the petitioners have an assumption that all social phenomena considered as “deviant” [premarital sex and same-sex relationships] by them that occur in society—even the majority of the nation’s big problems—will effectively be solved through criminal policies that punish individuals who act on it criminally. When we look at this paradigm implied by the petitioners, we have to be mindful that legal measures comprise only one element of aspects regulating our social life to create and maintain societal order. We have other social regulatory tools, which include morality, courtesy and religious values. Legal measures are placed last in line among these tools.[105]

In advising the parliament’s consideration of similar issues, the court mentioned Indonesia’s international legal obligations, and global trends:

Lawmakers have to pay careful attention not only to the legal developments that occur in the Indonesian society as a result of not only the Indonesian people’s worldview but also the legal developments that take place globally.

Proposed Revisions to the Criminal Code

Indonesia’s parliament has been revising the national Criminal Code since 1964. Beginning in January 2018, versions of the draft Criminal Code that featured troubling proposed provisions on criminalizing consensual sexual relations began circulating through various parliamentary committees, and a taskforce situated in parliamentary Commission III in charge of law and human rights.

In media interviews, taskforce members indicated that they intended to criminalize all sex outside of marriage (zina) as well as an additional clause specifically outlawing adult consensual same-sex conduct. Lawmakers justified various forms of criminalization as compromises against worse forms, and some even claimed that criminalizing same-sex conduct could protect LGBT people against vigilantism.

On January 22, 2018, Zulkifli Hasan, speaker of Indonesia’s People’s Consultative Assembly, who had been one of the first public figures to make inflammatory anti-LGBT statements in 2016, falsely told reporters that some parliamentarians were discussing same-sex marriage.[106] Erma Ranik, a member of the Criminal Code taskforce, tweeted and questioned Hasan’s inaccurate claim.[107] Hasan’s statement that legislators were discussing same-sex marriage was not true, but because it is a contentious and divisive topic in Indonesia it prompted all political parties to publicly affirm some degree of opposition to the basic rights of LGBT people.

Other taskforce members proposed what they considered to be a compromise. As Ichsan Soelistio, a parliamentarian from Indonesia’s largest political party, Indonesian Democratic Party for Struggle (PDIP), and one of the taskforce members, told the Washington Post: “[We] have agreed to accept a law which allows prosecution of sex outside marriage and homosexual sex, but only if one of the sexual partners or their family members report the crime to police.”[108] Soelistio, who is a member of President Jokowi’s party, called the law “a firewall.” Without it, he claimed, “the public can try to take the law into their own hands” and attack LGBT people.

In February, the draft under consideration included proposed clauses that would increase the penalty for “obscene acts” with a minor to nine years’ imprisonment (up from five), and establish as a criminal offense “obscene acts” with people over the age of 18 if they “constitute elements of pornography [in their action],” carrying a nine-year sentence as well.

In May, Enny Nurbaningsih, who heads the parliamentary taskforce on the revisions to the criminal code, told reporters that “We want to make sure that the bill does not have an impression that it is discriminatory.”[109] The speaker of the House of Representatives, Bambang Soesatyo, responded however that the new criminal code will criminalize adult consensual same-sex conduct, explaining:

“We must not fear or succumb to outside pressure and threats that banning LGBT practices will decrease foreign tourism. What we must prioritize is the safety of nation's future, particularly the safety of our youth from influences that go against norms, culture and religion.”[110]

The draft also contains new prohibitions against advertising contraceptive products.[111] While the proposal contains an exception for NGO staff, it appears the draft would outlaw the commercial sale of condoms. Doing so would directly limit access to condoms, a crucial HIV prevention tool.[112]

The wording in the draft Criminal Code is similar to other Indonesian laws. The 2008 Law on Pornography also makes “obscenity and sexual exploitation” (perbuatan cabul) a criminal offense. John McBeth, a Jakarta-based journalist who has covered Indonesia for more than three decades, wrote that the Criminal Code changes are “a nod towards Islamic conservatism.”[113] Nurbaningsih said in a Jakarta Post interview: “We want to accommodate the needs of our heterogeneous society that holds [its own] values. We cannot equate our society with Western societies that have broader freedoms, like Europe. We have our own cultural values.”[114]

Nurbaningsih made an argument similar to that of many public figures who contributed to the deluge of anti-LGBT rhetoric in 2016—he claims to not be targeting the individuals but their “obscene acts”:

For the new regulation, we cannot [criminalize] a person [for his or her sexual orientation]. Instead, what we regulate is their [sexual practice], whether it is conducted in private or in public.

We are prohibited from raiding dormitories one by one to see whether or not there are two people in the same room. That is a private matter.

For the Republic of Indonesia, it is not possible for the government to intrude on the private matters of its citizens. But when private matters disrupt public matters, we have to enforce the law. For instance, when a person [engages in LGBT practices] to disrupt public order. We are not a liberal country.[115]

In an assessment of the proposal to expand the criminal sanctions for sex outside of marriage (zina), Naila Rizqi Zakiah, a public defender at the Community Legal Aid Institute in Jakarta, explained:

As is stands, the KUHP [Criminal Code] already criminalises adultery (zina). But the provision on adultery applies to sex between a married person and a person who is not their spouse, and is a complaint offence (delik aduan). This means it is only considered a crime if a party who feels they have suffered from the act reports it to the police. Article 484 of the revised criminal code, however, converts zina where one of the parties is married into a “normal offence” (not based on a complaint or report), meaning that anyone can report cases to police.[116]

On February 7, 2018, in his concluding remarks during his visit to Indonesia, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein said:

I am greatly concerned about the discussions around revisions to the penal code…. Because these proposed amendments will in effect criminalise large sections of the poor and marginalised, they are inherently discriminatory. LGBTI Indonesians already face increasing stigma, threats and intimidation. The hateful rhetoric against this community that is being cultivated seemingly for cynical political purposes will only deepen their suffering and create unnecessary divisions. Moreover, should the penal code be revised with some of the more discriminatory provisions, it will seriously impede the Government’s efforts to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals, and would run counter to its international human rights obligations.[117]

III. Impact of Moral Panic on Indonesia’s HIV Epidemic

Once there is a hint of sex associated with an event, it is in danger. I even stay away from any gathering that could be possibly perceived as gay, and then attacked.[118]

—MSM HIV outreach worker in Jakarta, November 2017

The anti-LGBT moral panic that began in 2016, and the sharp increase in arbitrary arrests, regressive policy changes, and legislative proposals that have accompanied it, portend a public health crisis. As outlined above, Indonesia’s population of MSM had already been experiencing increased rates of new HIV infections, and the anti-LGBT panic has made the situation even worse, negatively impacting HIV outreach education, condom distribution, and prevention activities.

Three police raids in 2017 shut down MSM HIV outreach “hot spots,” places where outreach workers would routinely meet and counsel MSM, as well as provide condoms and voluntary HIV tests. In at least two of the well-publicized raids, in Surabaya and West Java, police openly used condoms as evidence in exposing and humiliating MSM detainees in the media, and charging them under the anti-pornography law.

Human Rights Watch interviews with MSM HIV outreach workers and clinic staff in Jakarta and Yogyakarta found that outreach workers experienced increased insecurity and isolation as a result of the anti-LGBT moral panic, police raids, and general sense of fear among sexual and gender minority communities. Many reported substantial and unprecedented negative impacts on their ability to contact and counsel MSM.

MSM “Hot Spots” Disappear

The police raids on night clubs and saunas popular with gay and bisexual men in 2017 was a devastating blow to the morale and perceived safety of LGBT people in Indonesia. And because these private social spaces were also incorporated into HIV awareness and testing outreach programs, the raids also significantly disrupted crucial public health programming. HIV outreach workers in Jakarta told Human Rights Watch that one immediate impact of the raids and the subsequent closure of the venues—all of which were known “hot spots” for HIV prevention and testing outreach—was that public health workers like them no longer had their typical access points for education, condom distribution, and testing programs.

“It is devastating that these clubs have closed—they were the only places where we could find the community,” said an MSM HIV outreach worker in Jakarta. “Clubs were hot spots for us because we knew that even the discreet guys felt safe about their sexuality inside, so we could do HIV testing and give condoms and they wouldn’t be scared to participate.”[119] A colleague added: “It was the only place where we could test someone and deliver positive results in a way that didn’t destroy them.”[120] Said the outreach worker: “Condom distribution was fine before 2016. The anti-LGBT rhetoric plus the closure of the hot spots have made it very difficult…. The hot spots aren’t there any more—it’s getting more and more difficult to find MSM.”[121]

The combination of stigma, fear, and newfound lack of safe spaces has left outreach workers guessing, rather than relying on evidence-based community outreach models. As the outreach worker quoted above explained: “Now we have to guess about our own community—it’s a guessing game to find our own peers.”[122] And while they continue to attempt to network with MSM in other venues, all of the outreach workers Human Rights Watch interviewed in Jakarta said it became increasingly difficult during the second half of 2017 to have basic conversations about safer sex, or hand out condoms. Said one Jakarta-based outreach worker:

Now instead of the clubs and saunas we try to do basic outreach in public places that aren’t MSM-specific and it’s not working. Even if we can start a private conversation with a guy who is MSM, they won’t take condoms from us because other people could see it. I’m basically going out for a day or night of work, and coming back with all my condoms that I started with.[123]

An outreach worker who had worked in each of the three major venues that were shut down in 2017 said: “After the three raids in 2017, the remaining locations are getting harder and harder to work at—fewer and fewer guys agree to get tested or take condoms each time. They tell us they are scared of both—the test and the condoms.”[124]

Difficulty and Danger for Outreach Workers

All of the HIV outreach workers Human Rights Watch interviewed in November and December 2017 said the anti-LGBT crisis of 2016 and the raids and attacks on LGBT people in private spaces in 2017 had affected their perception of their own safety, as well as their ability to effectively do their jobs.

An outreach worker in Jakarta said: “MSM are feeling more and more insecure as a result of this anti-LGBT moral panic. It’s becoming more and more work to convince them of the basics—condoms, testing—because of these fears.”[125] A colleague who works in a different part of the city said: “This broader fear has made people suspicious of us. Even when we carry paperwork from the National AIDS Commission [in the past], even when we explain what we are doing, they refuse to participate.”[126] For some outreach workers, the contrast between their pre-2016 working environment and their current working environment is stark, and they attribute the shift to the virulent anti-LGBT rhetoric and misinformation that has dominated the media since 2016. For example, one Jakarta-based outreach worker told Human Rights Watch:

In the past, people used to listen to our HIV lessons and ask questions. In the past six months to one year, however, the tone has changed: They now say they’ve heard from the media that our organizations are trying to profit off of HIV, and they’re suspicious that HIV is even real. They say they want to get paid to take an HIV test.[127]

Another outreach worker explained: “Before 2016 and 2017, I could have actual conversations with MSM, even the discreet ones. Now people just walk away from me—they physically don’t want to be seen near me once I identify myself as working for an HIV NGO.”[128] Another outreach worker agreed that “over the past two years, MSM have started distancing themselves from outreach workers” and also noticed that “we see more and more [MSM] waiting to get really sick before they seek help or even ask questions about HIV.”[129] An HIV counselor at government (puskesmas) community health clinic in Yogyakarta confirmed the trend in his clients as well:

Most of the MSM we see these days in the clinic have at least mild symptoms when they come in for their first HIV test—they seem to know there is something wrong, then they come in, whether they come on their own or come because an outreach worker referred them. [In the past year] I’ve given positive results to a 17-year-old who didn’t even know what HIV was—let alone how he got it.[130]

Beyond the changes outreach workers observed in how MSM interacted with them, some workers feared for their own safety while doing their jobs. For example, one described the challenges in accessing MSM networks after the clubs and saunas closed. He said:

Now if we try to go to social spaces or cruising areas based on rumors, and we approach a guy to talk about HIV or condoms—if it turns out he’s not MSM or he’s a hostile person, we are at risk of being attacked, or accused of being gay in public. So many people immediately associate HIV with LGBT that it’s dangerous to make a mistake and talk to someone who’s not MSM.[131]

Citing the raids on the Jakarta establishments in 2017, one outreach worker explained: “After the [raids], [our organization] held an edutainment event for general HIV awareness and I was scared to attend—scared to go to my own work event and do my job.”[132] And in addition to the observation that MSM were increasingly approaching outreach workers when they felt sick, some outreach workers observed an uptick in questions about personal safety. For example, one said:

Before this year, MSM never asked us about their physical safety. They’d ask about HIV and sex and stuff, but not safety. Now when we chat with them and tell them where they can go get an HIV test, for example, the first question they all ask is: “Is it safe to go there?”[133]

Even a waria HIV outreach worker who argued that the waria community’s history with violence and discrimination had somewhat inoculated them against the 2016-2017 anti-LGBT political crisis, told Human Rights Watch: “These days I hold mobile testing sessions at my rented room and invite people to come by word of mouth. We used to do testing on the street but it’s no longer safe or realistic—too many people associate HIV with LGBT, and that [acronym] is dangerous now.”[134]

Condoms as Evidence

HIV is a potentially fatal disease, and other sexually transmitted diseases increase the likelihood of HIV infection. Police interference with people’s ability to access condoms or health information from peers impedes their rights to life and health and is incompatible with human rights standards. For marginalized people, some of the most effective HIV protection outreach workers—and indeed sometimes the only such workers—are their peers. When laws and policies equating condoms with criminal activity interfere with the efforts of MSM to distribute condoms to their peers, access to health is significantly undermined.

An MSM HIV outreach worker in Jakarta told Human Rights Watch: “Condoms right now feel like a strictly prohibited item. I feel like I’m asking people to smuggle illicit drugs when I hand them out.”[135]

Other MSM, including those who did outreach work and those who were not involved in HIV work, echoed this fear. An outreach worker in Jakarta said that he increasingly struggled to convince MSM to take condoms from him. “People always refuse condoms these days because they’re afraid of having them used as evidence,” he said. “They tell me even keeping them in your private rented room is dangerous.”[136] Another Jakarta-based outreach worker said:

At general public HIV awareness events these days, we barely get anyone to take condoms. We hear things like: “If there’s a raid, and I have condoms in my pocket, I’ll be accused of being a whore!”[137]

Explained a gay man in Jakarta: “Two years ago we used to say to each other, ‘Oh, I’m out of condoms do you have any I can take?’ but now we don’t say even that—we can maybe whisper about condoms now but even that takes courage.”[138] Others told Human Rights Watch they had experienced direct harassment from police and security guards at shopping malls when authorities discovered they were carrying condoms. One MSM outreach worker recounted that a police officer, upon noticing the condoms he was carrying in his bag, asked him: “Are you promoting free sex or something?”[139]

Another Jakarta-based outreach worker explained that part of his job was to distribute boxes of condoms to massage parlors that catered to gay and bisexual male clients. He said that during the last six months of 2017, parlor owners began refusing the shipments. “Originally, I did monthly drops at nine parlors, now only six are open and only two of those six will take condoms from me,” he said. “They say they can’t risk the police coming and using condoms as evidence of gay prostitution.”[140]

IV. Indonesian and International Law

We aren’t asking for much—just acknowledgment that we are here, and respect for our right to be safe in our everyday lives.

—Gay man in Jakarta, November 2017

In 2012 the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights published a guide summarizing some of the core legal obligations of states with respect to protecting the human rights of LGBT people. They include obligations to:

- Protect individuals from homophobic and transphobic violence.

- Prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity.

- Safeguard freedom of expression, association and peaceful assembly for all LGBT people. [141]

Indonesia is a party to core human rights treaties and protocols setting forth many of these obligations. Relevant treaties include the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), and the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC).[142]

Right to Privacy

The criminalization of same-sex conduct between consenting adults violates the right to privacy and the right to freedom from discrimination, both of which are guaranteed under the ICCPR.[143]