Summary

Every day, people in Brazil put themselves at risk to defend the Amazon rainforest from illegal logging. They are public officials who work for the country’s environmental agencies and police officers who fight environmental crime; they are small farmers who dare to tell authorities the names of those sending in chainsaws and wood-hauling trucks; they are Indigenous people who patrol their territories on foot, in boats, and on motorcycles, armed with bows and arrows and GPS, to protect the forests that they depend on to sustain their families and preserve their way of life.

The defenders take this risk with little expectation that the state will protect them as they confront loggers who brazenly violate Brazil’s environmental laws — and who threaten, attack, and even kill those who stand in their way.

Illegal deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon is driven largely by criminal networks that have the logistical capacity to coordinate large-scale extraction, processing, and sale of timber, while deploying armed men to protect their interests. Some environmental enforcement officials call these groups “ipê mafias,” referring to the ipê tree whose wood is among the most valuable and sought-after by loggers. Yet these loggers’ quarry includes many other tree species — and their ultimate goal is often to clear the forest entirely to make room for cattle or crops.

The stakes of the showdown between the forest defenders and these criminal networks extend far beyond the Amazon, and even the borders of Brazil. As the world’s largest tropical rainforest, the Amazon plays a vital role in mitigating climate change by absorbing and storing carbon dioxide. When cut or burned down, the forest not only ceases to fulfill this function, but also releases back into the atmosphere the carbon dioxide it had previously stored. Sixty percent of the Amazon is located within Brazil, and deforestation accounts for nearly half of the country’s greenhouse gas emissions, according to government data.

For more than a decade, preserving the Amazon rainforest has been a central component of Brazil’s commitment to take measures to curb global warming. Under the 2015 Paris Agreement on Climate Change, it committed to eliminating all illegal deforestation — which accounts for 90 percent of all deforestation — in the Amazon by 2030.

A 2019 report of the Special Rapporteur on human rights and the environment states that the right to a safe, clean, healthy and sustainable environment includes a safe climate, and that “failure to fulfill international climate change commitments is a prima facie violation of the States’ obligations to protect the human rights of its citizens.”

For Brazil to meet its Paris Agreement commitment it will need to rein in the criminal groups that are driving much of the deforestation. And that, in turn, will require protecting the people who are struggling to defend the forest from their onslaught.

During his first year in office, President Jair Bolsonaro has shown little interest in doing either. On the contrary, he has scaled back enforcement of environmental laws, weakened federal environmental agencies, and harshly criticized organizations and individuals working to preserve the rainforest. His words and actions have effectively given a green light to the criminal networks involved in illegal logging, according to environmental officials and local residents. By doing so, he is putting both the Amazon and the people who live there at greater risk — and he is undercutting Brazil’s ability to fulfill its commitment to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions and help mitigate global warming.

Violence Linked to Illegal Deforestation

The problem of violence by loggers in the Amazon did not begin with Bolsonaro. Human Rights Watch conducted more than 60 interviews with federal and state officials involved in environmental or criminal law enforcement in the Amazon region, as well as another 60 with members of Indigenous communities and other local residents, and found a broad consensus that this violence has been a widespread problem in the region for years.

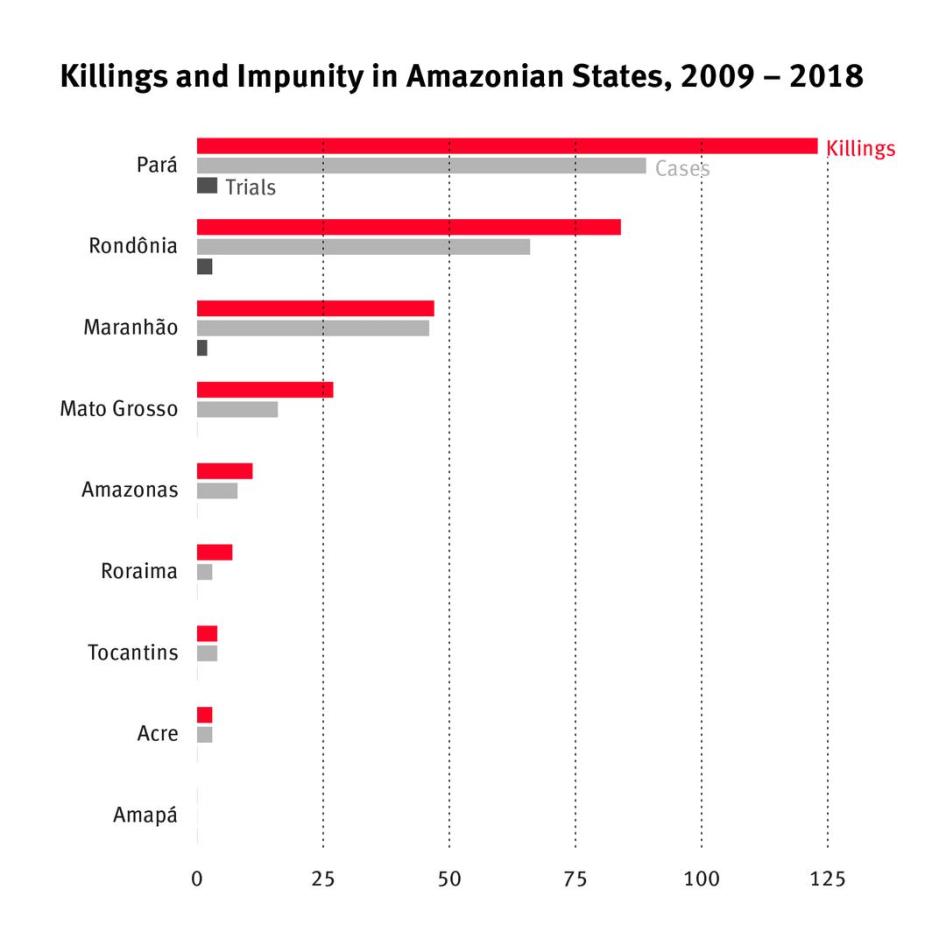

More than 300 people have been killed during the last decade in the context of conflicts over the use of land and resources in the Amazon — many of them by people involved in illegal logging — according to the Pastoral Land Commission, a non-profit organization affiliated with the Catholic Church that keeps a detailed registry of cases based on information gathered largely by its lawyers, who monitor cases of rural violence throughout the country. There are no comparable statistics compiled by government agencies, and federal prosecutors cite the commission’s numbers as evidence of the scope of the violence by loggers.

This report documents 28 such killings, most of them since 2015 — plus four attempted killings and more than 40 cases of death threats — in which Human Rights Watch obtained credible evidence that the perpetrators were engaged in illegal deforestation and the victims were targeted because they stood in the way of their criminal enterprise. Some of these victims were environmental enforcement officials. Most were members of Indigenous communities or other forest residents who denounced illegal logging to authorities or sought in other ways to contribute to Brazil’s efforts to enforce its environmental laws. Examples documented in this report include the following:

- Environmental defender Dilma Ferreira Silva and five other individuals were killed in Pará state in 2019 under orders — according to police — of a landowner involved in illegal logging who feared Silva and the others would report his criminal activities.

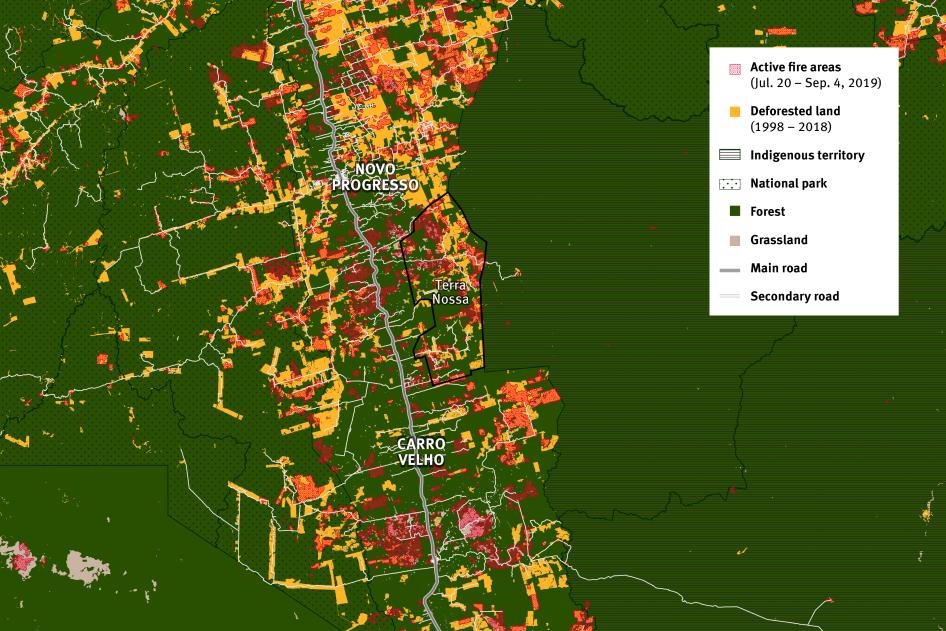

- A resident of the Terra Nossa settlement in Pará state was killed and another disappeared after they announced plans to report illegal logging to authorities in that settlement in 2018. The brother of one of the victims, who was investigating the crime, was also killed, as was the leader of a small farmers’ trade union after he too announced plans to report the illegal logging. Residents of the settlement told Human Rights Watch that all four men were killed by members of an armed militia working for a criminal network of local landowners involved in illegal logging. An internal report by inspectors from INCRA, the federal land reform agency, found that the landowners were indeed responsible for illegal deforestation in the area, as well as illegal mining and the occupation of federal lands.

- Naraymi Suruí, a leader of the Suruí Paiter Indigenous people, was attacked by gunmen two weeks after confronting illegal loggers inside the Sete de Setembro Indigenous Territory in Rondônia state in 2017. Two people whom he recognized as loggers fired gunshots five times at him and his wife, Elizângela Dell-Armelina Suruí, without striking either.

- State police sergeant João Luiz de Maria Pereira was killed by a suspected logger while participating in an anti-logging operation in the Jamanxim National Forest in Pará state in 2016.

- Environmental defender Raimundo Santos was killed in 2015 after reporting illegal logging in the Gurupi Biological Reserve in Maranhão state. A landowner allegedly involved in illegal logging confessed to police that he had hired a retired police officer who, in turn, hired two active officers, to murder Santos.

- Eusebio Ka’apor — a leader of the Ka’apor people involved in organizing forest patrols to prevent loggers from entering Alto Turiaçu Indigenous Territory in Maranhão state — was shot in the back and killed by two attackers on a motorcycle in 2015. Shortly after his death, six of the seven members of the Ka´apor Governing Council, which coordinates the patrols, received death threats from loggers.

- Osvalinda Marcelino Alves Pereira and her husband, Daniel Alves Pereira, both small-scale farmers, have suffered repeated death threats for nearly a decade since they began reporting illegal logging by a criminal network near their home in Pará state. In 2018, they found two simulated graves dug in their yard, with wooden crosses affixed on top.

While most of the cases documented by Human Rights Watch occurred in the states of Pará or Maranhão during the past five years, the report also includes examples from previous years and from other states that support the claim by federal and state law enforcement officials that violence by loggers is a widespread and longstanding problem in the Brazilian Amazon.

Failure to Investigate and Prosecute

Perpetrators of violence in the Brazilian Amazon are rarely brought to justice. Of the more than 300 killings that the Pastoral Land Commission has registered since 2009, only 14 ultimately went to trial. Of the 28 killings documented in this report, only two did. And of the more than 40 cases of attacks or threats, none went to trial — and criminal charges have, to date, been filed in only one case.

This lack of accountability is largely due to the failure by police to conduct proper investigations into the crimes, according to federal and state prosecutors, and environmental officials. Local police, who themselves acknowledge shortcomings in the investigations, told Human Rights Watch that the lack of effective investigations is due largely to the fact that the crimes tend to occur in remote communities or places that are far from the nearest police station.

To assess the dynamics of impunity described by officials, Human Rights Watch examined how the police responded to killings in one region of Maranhão state — encompassing four Indigenous territories — where Indigenous peoples who have taken a stand against illegal logging report being victims of violent reprisals by loggers. There have been 16 killings reported in this region since 2015, including at least eight which local Indigenous leaders believe were reprisals by loggers. None have been successfully brought to trial.

Human Rights Watch interviewed police officers involved in the investigations of six of the 16 killings and identified serious flaws in their handling of the cases: in at least two, police investigators did not visit the crime scene and in five, there was no autopsy. A local police chief claimed that the remote locations of the crimes contributed to these failures. Yet Human Rights Watch found that in at least four of the six cases, the deaths occurred in urban centers with local police stations, not remote locations.

Federal police and prosecutors told Human Rights Watch that such omissions were commonplace in the investigations of killings by loggers conducted by state police, who have jurisdiction over ordinary cases of homicide.

Undoubtedly, there are cases of violence by loggers in which the remoteness of the crime scene could complicate efforts to conduct prompt investigations. But it need not make it impossible. Indeed, Human Rights Watch documented 19 killings and three attempted killings in remote locations in the Amazon in which police did conduct investigations that led to criminal charges being filed. The different police response, however, may be explained by the fact that 17 of these killings attracted national media attention.

Investigations of death threats by loggers fare no better. Officials and victims told Human Rights Watch of cases in which police in both Maranhão and Pará states refused to even register complaints of threats.

By failing to investigate the death threats, authorities are abdicating their duty to try to prevent violence by the criminal groups involved in illegal deforestation, and increasing the likelihood that the threats will be carried out. In at least 19 of the 28 killings documented in this report, the attacks were preceded by threats against the victims or their communities. If authorities had conducted thorough investigations of these prior acts of intimidation, they might have averted the killings. Examples documented in this report include the following:

- Gilson Temponi, president of a farmers’ association in Placas, Pará state, reported illegal logging and death threats from loggers to state and federal prosecutors in 2018. In December of that year, two men knocked on his door and shot him to death.

- Armed men threatened and attacked small farmers at Taquaruçu do Norte, in Mato Grosso state, for more than a decade to try to expel them from their land so that loggers could exploit timber in the area. In 2007, they killed 3 farmers and tortured at least 10 others, the Pastoral Land Commission reported. Residents also reported to the police attacks and threats in 2010, 2012, and 2014, but investigations never progressed, a Mato Grosso public defender told Human Rights Watch. In April 2017, armed men killed nine residents of Taquaruçu do Norte in what came to be known as the “Colniza massacre.”

Inadequate Protections for Forest Defenders

Since 2004, Brazil has had a program to protect defenders of human rights, including environmental defenders, which, in theory, should be able to provide protection to forest defenders who receive death threats. More than 400 people are currently enrolled in the program countrywide, most of them defenders of Indigenous rights, rights to land, or the environment.

The program aims to provide an array of protection measures to those enrolled, such as visits from program staff to defenders, maintaining phone contact, giving visibility to their work, and mobilizing other institutions to provide protection. Its mandate also includes developing “institutional strategies” to address the root causes of risk or vulnerability for those under protection.

However, government officials and forest defenders interviewed by Human Rights Watch unanimously agreed that in practice the program provides little meaningful protection. Generally, it involves nothing more than occasional phone check-ins.

In Pará, the state with the highest reported number of killings in conflicts over land and resources, prosecutors sued the state and federal governments in 2015 after finding that the federal program to protect human rights defenders was “completely ineffective.” In April 2019, a judge agreed with the prosecutors, ordering state and federal officials to provide more robust protection to five forest defenders threatened by loggers.

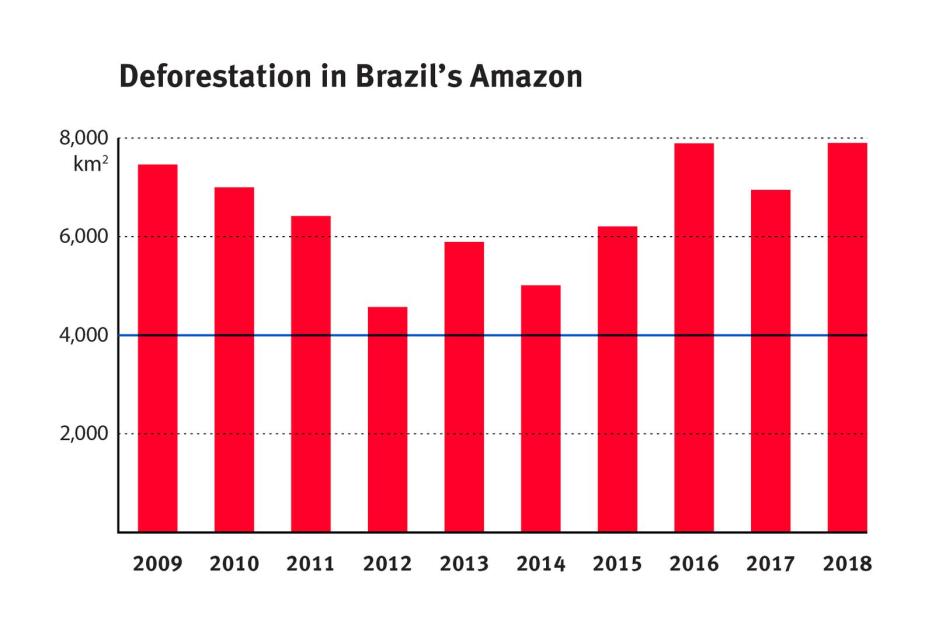

The Human Cost of Inadequate Environmental Enforcement

In 2016, Brazil signed the Paris Agreement on Climate Change and committed to eliminating illegal deforestation by 2030 in the Amazon. Between 2004 and 2012, the country had reduced overall deforestation in the Amazon by more than 80 percent, from almost 28,000 square kilometers of forest destroyed per year to less than 4,600. But deforestation began to climb in 2012, and by 2018 it had reached 7,500 square kilometers. That total is expected to be significantly larger in 2019.

Brazil’s success in curbing deforestation prior to 2012 was in part a result of the use of near real-time satellite imagery to locate and shut down illegal logging sites. It was also due to the creation of protected areas — conservation reserves and Indigenous territories — encompassing hundreds of thousands of square kilometers throughout the Amazon region, where special legal restrictions on land-use protect the forest.

But several developments combined to reverse this progress. Among them, loggers turned increasingly to techniques for removing trees that make it more difficult for satellite surveillance to detect the scope of the damage that is underway. At the same time, the country’s federal environmental enforcement agencies suffered budget and personnel cuts that have reduced the number of field inspectors available to conduct deforestation-monitoring operations.

Indigenous communities and other local residents have long played an important role in Brazil’s efforts to curb deforestation by alerting authorities to illegal logging activities that might otherwise go undetected. Several studies based on satellite data show that deforestation is much lower in land securely held by Indigenous peoples than in other comparable areas of the Brazilian Amazon, indicating that Indigenous territories are particularly effective as barriers against illegal logging. This contribution has become all the more vital in recent years given the diminished ability of Brazil’s environmental agencies to deploy inspectors to monitor what is happening on the ground.

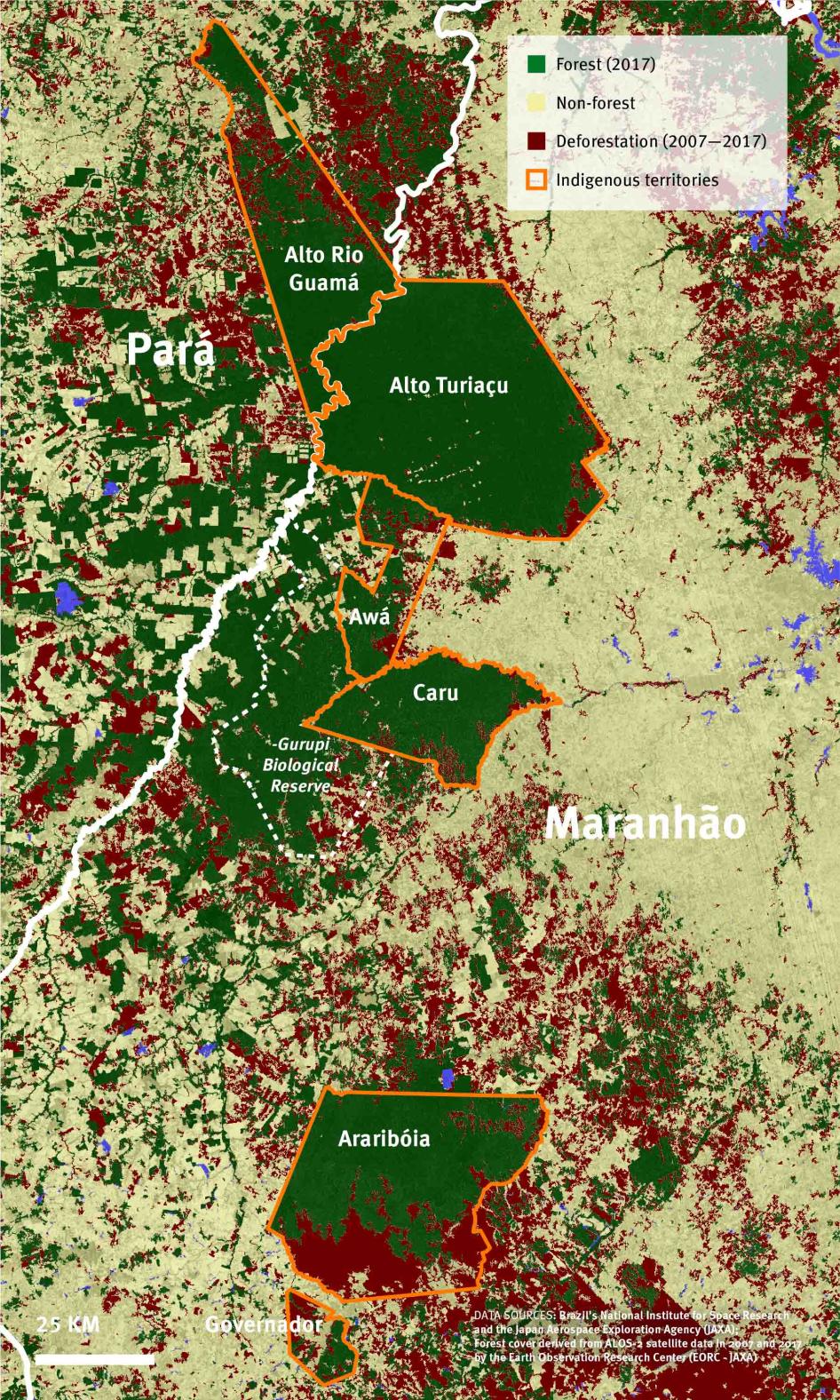

In Maranhão state, for example, as the capacity of federal government agencies to enforce environmental laws has diminished, members of four Indigenous communities – whose territories include some of the state’s last patches of pristine forest – have organized as “forest guardians.” The “guardians” patrol their territories and report the illegal logging they encounter to authorities. The patrols have been instrumental in bringing about enforcement operations on some occasions. Yet they have also resulted in community members being threatened, attacked, and according to community leaders, killed by loggers.

The experience of these four communities illustrates the dynamic at play wherever forest defenders are confronting illegal loggers in the Brazilian Amazon today. The scaling back of the enforcement capacity of the country’s environmental agencies generates greater pressure on Indigenous peoples to take a more active role in defending their forests — and, in so doing, put themselves at risk of reprisals by loggers.

At the same time, the failure to investigate these reprisals allows the violence and intimidation by loggers to continue unchecked, fueling a climate of fear that reduces the likelihood that more people, both Indigenous people and local residents, will take that risk — thereby depriving Brazil’s environmental agencies of local support that is vital for their efforts to fight illegal deforestation.

President Bolsonaro’s Anti-Environmental Policies

To end illegal deforestation and meet its commitments under the Paris agreement to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, Brazil needs a government that is committed to upholding the rule of law in the Amazon. That means taking a clear stand to protect the country’s forest defenders — including both environmental enforcement officials and members of Indigenous and other local communities — as they seek to contain the criminal networks that engage in illegal logging.

Instead, Brazil has a leader who seems determined to do precisely the opposite. President Jair Bolsonaro appointed a foreign minister who opposes international efforts to address climate change — claiming they are “a globalist tactic to instill fear and obtain power” — and an environment minister who dismisses global warming as an issue of “secondary” importance. Both ministers have eliminated the climate change units within their respective ministries, while the environment minister has also cut the budget for the implementation of the Climate Change National Policy by 95 percent.

The Bolsonaro administration has moved aggressively to curtail the country’s capacity to enforce its environmental laws. It slashed the discretionary budget of the Ministry of the Environment by 23 percent — eliminating funds that were destined for enforcement efforts and for fighting fires in the Amazon. And on a single day in February, it fired 21 of IBAMA’s 27 regional directors responsible for approving anti-logging operations. As of August, nearly all of these senior enforcement positions remained unfilled.

The administration then enacted policies that effectively sabotage the work of the enforcement agents who remain. One is dismantling the department that coordinated major anti-deforestation operations involving various federal agencies and the armed forces. Another is a requirement — verbally communicated to agents but not written — that agents leave intact the vehicles and equipment they find at remote illegal logging sites, rather than destroying them as they are authorized to do by Brazilian law. Agents now have to remove that equipment through the rainforest, making them vulnerable to ambushes by loggers trying to retrieve it.

The administration has moved to minimize the consequences faced by those caught engaging in illegal logging. During Bolsonaro’s first eight months in office, the number of fines for infractions related to deforestation issued by IBAMA fell by 38 percent compared to the same period the year before, reaching the lowest number of fines in at least two decades. In April, the government established that all environmental fines must be reviewed at a “conciliation” hearing by a panel presided over by someone who is not affiliated with the country’s environmental agencies. The panel can offer discounts or eliminate the fine altogether. And while the hearings are pending, the deadlines for payment are suspended. According to Suely Araújo, who was president of IBAMA until December 2018, the requirement of a conciliation hearing will cripple IBAMA’s ability to sanction environmental violations by delaying proceedings that already take years to complete.

The administration has also moved to limit the ability of Brazilian NGOs to promote enforcement efforts. In April, President Bolsonaro issued a decree abolishing committees made up of officials and members of NGOs, which played an important role in the formulation and implementation of environmental policies. Among those affected was the steering committee of the Amazon Fund, a fund run by Brazil that has received 3.4 billion reais (more than US$820 million) in donations to preserve the Amazon rainforest. Ninety-three percent of the money has come from Norway and the rest from Germany. Both countries warned the Bolsonaro administration that they opposed changes to the representation of NGOs in the Fund’s steering committee, which approves the conservation projects. But in June, the government dissolved the committee. In response, Norway suspended its contributions to the Fund, the future of which is now uncertain.

These policy moves have been accompanied by expressions of open hostility by the president and his ministers toward those who seek to defend the country’s forests. As a presidential candidate, Bolsonaro attacked IBAMA and ICMBio, calling them “industries of fines” and vowing to put an end to their “festival” of sanctions for environmental crimes. In May, he told journalists that he was “removing obstacles” to economic opportunity imposed by the “Shia environmental policies” of previous administrations, using the word for a branch of Islam as a synonym for radicalism.

Bolsonaro has been especially hostile toward the nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) that defend the environment and the rights of Indigenous peoples, claiming they “exploit and manipulate” Indigenous people and promising to fight their “Shia environmental activism.” Similarly, Bolsonaro’s vice president has said that Brazil’s economic potential is tied down by the “Shia environmentalism” of NGOs. And his environment minister has complained about the existence of “an industry of eco-Shia NGOs.”

This hostility has also extended toward European governments that have supported conservation efforts in the Amazon. While alleging that this support is motivated by a desire to exploit the forest’s riches for themselves, President Bolsonaro said in July 2019: “Brazil is like a virgin that every pervert from the outside lusts for.”

At the same time, the administration has signaled support for those responsible for the deforestation of the Amazon. After the mass firing of senior officials at IBAMA, Bolsonaro boasted to a gathering for landowners that he had personally ordered his environment minister to “clean out” the country’s environmental agencies. In July, shortly after assailants torched a fuel truck delivering gas for IBAMA helicopters conducting anti-logging operations Rondônia state, the environment minister met with loggers in the town where the assault had taken place and told them that the logging industry “needs to be respected.”

The anti-environmental policies and rhetoric of Bolsonaro and his ministers have put enforcement agents and local forest defenders at greater personal risk, according to senior federal prosecutors in the Attorney General’s Office, who say that reports of threats by criminal groups involved in illegal logging have increased since Bolsonaro took office. “It’s disturbing to see the state inciting threats against the state itself,” the head prosecutor in the environmental unit told Human Rights Watch. “Bashing government agencies is like music for illegal economic actors,” the head of the Indigenous rights unit said. “Loggers understand Bolsonaro’s statements as authorization to act.”

Since Bolsonaro’s election, the illegal logging by criminal networks in the Amazon has become more brazen, according to enforcement officials and residents. “They believe that they will be able to do whatever they want, and we won’t be able to impose fines on them or destroy their equipment,” one senior IBAMA official explained. Community leaders in two regions of Pará state told Human Rights Watch that they used to see trucks removing illegally-harvested timber from the forest only at night, but since Bolsonaro’s election, the trucks also pass in unprecedentedly large numbers and in broad daylight. Just in January, loggers invaded at least four Indigenous territories.

The impact on the rainforest has been dramatic. During Bolsonaro’s first eight months in office, deforestation almost doubled compared to the same period in 2018, according to preliminary official data. By August 2019, forest fires linked to deforestation were raging throughout the Amazon on a scale that had not been seen since 2010.

Such fires do not occur naturally in the wet ecosystem of the Amazon basin. Rather, they are started by people completing the process of deforestation where the trees of value have already been removed, and they spread through the small clearings and discrete roads that have been carved by loggers, leaving veins of dryer, flammable vegetation that serve as kindling to ignite the rainforest.

According to federal and local law enforcement, the fires in 2019 were the result of an “orchestrated action” prepared in advance by the criminal organizations involved in illegal deforestation.

But rather than confront these criminal networks, the Bolsonaro administration responded to the fires with the same formula it has used to advance its anti-environmental agenda throughout the year. It sought to downplay the problem, claiming initially that dry weather was responsible for the fires. It then attacked the country’s environmental NGOs, with the president going so far as to accuse them, without evidence, of starting the fires in an effort to embarrass the government. And it lashed out at foreign leaders, dismissing international concerns about the damage being wrought to the world’s largest rainforest and one of its most important carbon sinks.

Only after a growing number of Brazilian business leaders raised concerns that the government’s response to the fires was damaging the country’s international image did Bolsonaro announce the deployment of the armed forces to put them down.

What the Bolsonaro administration has not done is announce any plan to address the underlying problem that drives the deforestation: the ability of criminal networks to operate with near total impunity in the Amazon, threatening and attacking the forest defenders who attempt to stop them. As long as this violence continues unchecked, so too will the destruction of the rainforest, the preservation of which is crucial to Brazil’s efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and to the world’s effort to mitigate climate change.

Key Recommendations

Brazil should take urgent steps to end impunity for acts of violence related to illegal deforestation in the Amazon.

- The Minister of Justice should convene federal and state law enforcement authorities including prosecutors, police, and environmental agents, to draft and implement a plan of action – with meaningful input from civil society representatives – to address the acts of violence and intimidation against forest defenders and dismantle the criminal networks involved in illegal deforestation in the Amazon region.

- The Federal Attorney General should make the issue of violence in the Amazon a top priority, including by conducting extensive reviews of documented cases of violence and threats to identify patterns and perpetrators, seeking federalization of cases of serious human rights violations that are not properly investigated by state authorities, and ensuring that its Amazon working group has sufficient resources and personnel to investigate and prosecute those responsible for illegal deforestation and violence.

- Congress should establish a Congressional Investigative Commission (CPI in Portuguese) and conduct public hearings to examine the criminal networks responsible for illegal deforestation and acts of violence and intimidation against forest defenders in the Amazon.

Brazil should support and protect its forest defenders.

- The Bolsonaro administration should express clear public support for all the forest defenders who seek to uphold the law in the Amazon region and commit itself to dismantling the criminal networks involved in illegal logging and to holding their members accountable for their crimes.

- Federal and state authorities should establish mechanisms whereby police, prosecutors, and environmental agencies meet regularly and maintain direct channels of communication with communities and individual forest defenders so that they can report illegal deforestation and acts of violence or intimidation.

- The Ministry of Human Rights should improve the federal program to protect human rights defenders, including forest defenders, by:

- Tailoring protection plans in consultation with forest defenders at risk to address their specific circumstances, through such measures as providing internet connections, installing security cameras, and covering the cost of deploying law enforcement agents to accompany them or monitor their situation.

- Coordinating with local NGOs and pressing state and federal authorities to address reports of illegal deforestation and violence filed by forest defenders.

- Congress should ratify the Escazú Agreement, which requires states to guarantee a safe and enabling environment for those who defend the forest by protecting them and investigating crimes committed against them.

Brazil should strengthen environmental protection in the Amazon rainforest as part of its human rights obligations.

- The Bolsonaro administration should repair the damage done to the state agencies responsible for environmental protection and ensure that their enforcement agents have the autonomy, tools, and resources needed to safely and effectively carry out their mission.

- The Bolsonaro administration should end its verbal attacks on – and unsubstantiated allegations against – environmental and other nongovernmental organizations and re-establish collaboration between federal agencies and civil society groups working to protect forest defenders, Indigenous rights, and the environment.

- The federal government should take adequate measures to meet Brazil´s commitments to mitigate climate change, in particular its pledged reductions in deforestation and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, by both protecting forest defenders and strengthening environmental protection, as laid out in the recommendations above.

Methodology

In researching this report, Human Rights Watch interviewed more than 170 people, including more than 60 members of Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities who have suffered violence or threats from people involved with illegal logging; as well as civil and federal police officers; state and federal prosecutors; public defenders; representatives of the federal agencies IBAMA, ICMBio, and FUNAI; other state officials; representatives of civil society organizations; and academics.

We conducted most interviews in person in Maranhão October 24-November 4, 2017 and June 3-12, 2018; in Brasília, April 3-4, 2018, October 15-16, 2018, January 14-15, 2019, April 24-27, 2019, July 2-5, 2019, and August 15-17, 2019; in Pará, April 27-May 4, 2019; and in Amazonas, on June 27, 2019. We also conducted interviews by telephone and messaging services between November 2017 and July 2019.

For data on killings in conflicts over land and resources we relied on the work of the Pastoral Land Commission, a Catholic Church affiliated non-profit organization founded more than 40 years ago with attorneys around the country who track and collect information on those cases and provide legal and other assistance to victims and their families. State and federal authorities do not gather data about cases involving conflicts over land and resources. The federal Attorney General’s Office itself uses the Pastoral Land Commission’s data.

Human Rights Watch selected Maranhão, Pará, and Amazonas states to conduct on-the-ground research in consultation with local organizations working on rural violence and Indigenous rights. In Maranhão, Human Rights Watch staff traveled to the Indigenous territories of Alto Turiaçu, Araribóia, Caru, and Governador because the Ka’apor, Tenetehara (also known as Guajajara) and Pyhcop Catiji (also known as Gavião) people living there have established forest patrols to defend their land. That environmental defense work has made them vulnerable to threats and attacks from loggers. Pará is the state with the highest number of killings due to conflicts over land and resources. Amazonas is the state with the largest section of the Amazon rainforest. We also conducted phone interviews about cases in Mato Grosso and Rondônia states.

In Brasília we interviewed authorities and activists during several visits. We also interviewed Indigenous people participating in an annual gathering known as “Free Land Camp” in April 2019.

Human Rights Watch staff conducted most interviews in Portuguese. We conducted two interviews in Indigenous languages, translated into Portuguese by Indigenous people, and a few interviews in English with English-speaking activists. Interviews were one-on-one and, in a few instances, in groups, depending on the preferences and customs of the interviewees.

Human Rights Watch identified interviewees through NGOs, officials, news media, and witnesses, who referred us to other people with whom we could speak.

Human Rights Watch has withheld publication of the identities of four witnesses for security reasons, and of seven public officials who requested that their names be kept confidential because their superiors had not authorized them to speak publicly or because they feared reprisals if they spoke openly about the failings of state institutions.

Human Rights Watch informed all participants of the purpose of the interview and that the interviews might be used publicly. They consented orally. No interviewee received compensation for providing information. We reimbursed the cost of transportation, modest lodging, and meals to three interviewees who traveled to a central location to meet with us.

Human Rights Watch examined copies of statements witnesses made to authorities, data provided by government agencies during meetings and upon request, case files, judicial decisions, and publicly available official information. We also reviewed academic publications and reports from research centers and NGOs.

Glossary of Terms and Acronyms

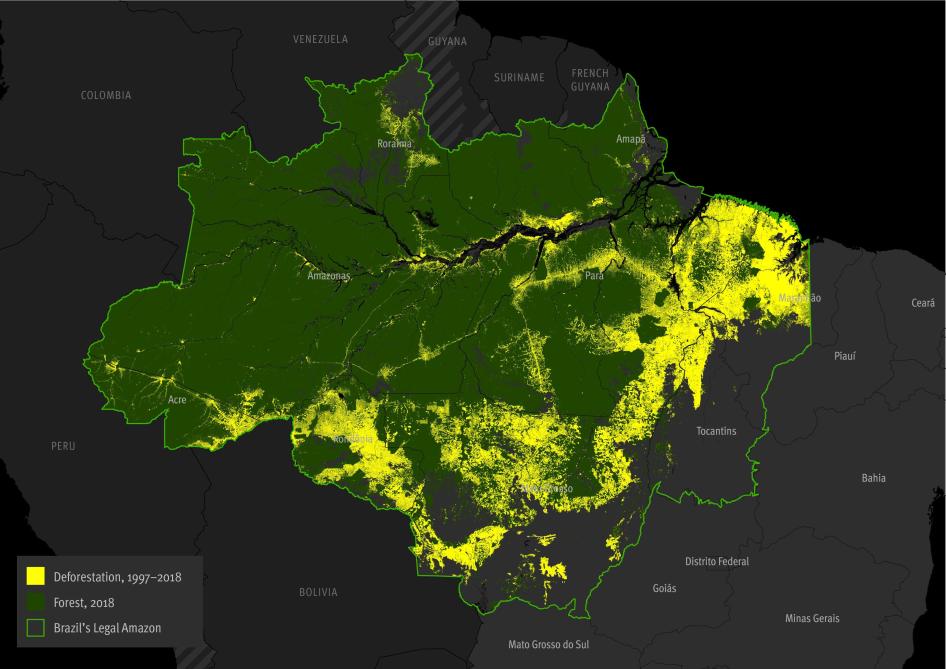

Amazon

For the purposes of this report, Brazil’s “Amazon” refers to the area known as “Legal Amazon” under Law 1,806/1953 that includes the states of Acre, Amapá, Amazonas, Mato Grosso, Pará, Rondônia, Roraima, Tocantins, and the western part of Maranhão.

Amazon Task Force

A working group of federal prosecutors specialized in combatting environmental crimes in the Amazon region, established by the attorney general in 2018. The group has a federal prosecutor working exclusively for the task force, while others combine it with their regular duties. Because of the limited resources, the Task Force currently focuses mostly on fighting deforestation in the southern part of Amazonas state.

Conservation Reserves

Nature areas with special restrictions on the use of land and waters. Federal conservation reserves are managed by ICMBio, while those created by states and municipalities are managed by local government entities. Law 9985 of July 18, 2000, which regulates conservation reserves, divides conservation reserves into two types: (1) Integral Protection Conservation Reserves, which bar human settlement inside the reserve but allow for research and, in some cases, visiting; and (2) Sustainable Use Conservation Reserves, which allow people to live inside the reserve as long as they use resources in a sustainable manner.

Demarcation of Indigenous Territory

The process whereby the federal government recognizes a claim by Indigenous peoples to a certain geographic area and establishes exclusive use of the territory for those peoples. Brazil’s Constitution entrusts the federal government with the obligation to demarcate Indigenous territories. The process includes conducting anthropological and other studies to assess the claim to the territory and define the territory’s limits, and an administrative approval process that ends with a decree by the president and the registration of the Indigenous territory in Brazil’s land registry.

DETER

Real-Time Deforestation Detection System (DETER), a system created by Brazil's National Space Research Agency (INPE) to provide near real-time alerts of deforestation for enforcement purposes based on satellite imagery. The alerts are an indication of deforestation but, because of cloud cover and other factors, they are not as accurate to estimate total deforestation as the data produced by the Deforestation of the Legal Amazon Satellite Monitoring Project (PRODES), also created and run by INPE.

Environmental crime

For the purposes of this report, we consider environmental crimes those crimes related to the damage or destruction of the environment by individuals or companies, as established by Brazilian law. Under Brazil’s 1998 Environmental Crime Law, those crimes include harvesting timber in government-owned forests and transporting, buying, or selling illegally-harvested timber, among others. Federal and state police enforce environmental criminal law.

Environmental defender

For the purposes of this report, we consider environmental defenders those people who fall under the definition of “environmental human rights defenders” laid out by the UN special rapporteur on human rights defenders in 2016: “Individuals and groups who, in their personal or professional capacity and in a peaceful manner, strive to protect and promote human rights relating to the environment, including water, air, land, flora and fauna.”

Environmental infraction

For the purposes of this report, we consider environmental infractions those established by Brazilian law. The 1998 Environmental Crime Law establishes criminal and administrative punishment for individuals and companies for harming the environment. Decree 6514 details what constitutes administrative environmental infractions, such as deforesting inside conservation reserves or transporting and buying or selling illegally-obtained timber, and the corresponding fine. Those provisions are enforced by IBAMA and ICMBio at the federal level, and by states and municipal environmental agencies at the local level.

Fazendeiro

Rancher or large farmer in Portuguese.

Forest defender

For the purposes of this report, we consider forest defenders anyone who takes steps to protect the forest from illegal deforestation, such as local residents who seek to provide information about environmental crimes to police and prosecutors, Indigenous people who patrol the forest, Indigenous leaders who set up and support those patrols, and public officials who plan or conduct environmental law enforcement operations and activities.

FUNAI

The National Indian Foundation (FUNAI), the federal agency that protects and promotes Indigenous rights.

IBAMA

The Brazilian Institute of the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA), the country’s main federal environmental protection agency. It is tasked with civil enforcement of federal environmental law throughout Brazil. It can fine those who violate these laws.

ICMBio

The Chico Mendes Institute for the Conservation of Biodiversity (ICMBio), the federal agency that manages and protects federal conservation reserves. ICMBio agents have authority to conduct civil enforcement of environmental law within federal conservation reserves and the surrounding “buffer zone.”

INCRA

The Colonization and Land Reform National Institute (INCRA), the federal government agency that carries out land reform by creating rural settlements for poor farmers and establishing land titling and property rights in public lands.

INPE

Brazil's National Space Research Agency (INPE), a research agency of the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation that provides annual official estimates of deforestation in the Amazon, near real-time deforestation alerts for enforcement purposes, and near real-time forest fire information, among other activities.

Indigenous Territory

For the purpose of this report, we consider Indigenous territories those defined by Brazil’s law. Brazil’s Constitution defines the territories as those on which Indigenous people “live on a permanent basis, those used for their productive activities, those indispensable to the preservation of the environmental resources necessary for their well-being and for their physical and cultural reproduction, according to their uses, customs and traditions.” The Constitution grants the federal government ownership of Indigenous territories (Article 20) and Indigenous people the exclusive use of those territories (Article 231).

PRODES

The Deforestation of the Legal Amazon Satellite Monitoring Project (PRODES), a system run by the National Space Research Agency (INPE) that produces annual official estimates of clear-cut deforestation in Brazil’s Amazon through analysis of satellite imagery.

Protected Areas

For the purpose of this report, we consider protected areas to be conservation reserves and Indigenous territories, as defined by Brazilian law. Legal restrictions on land-use protect the environment in these areas.

______________________________________________________________________________

Note on the Use of Indigenous Names

Some Indigenous people use their names in their Indigenous language, which are different from their legal names in Portuguese. When interviewees provided their Indigenous names, the report uses those names and provides their Portuguese names in footnotes. Some Indigenous persons have as their last name in Portuguese the name of their people, and others use it by choice as an affirmation of their identity. A 2012 joint resolution by the National Council of Justice and the National Council of Federal Prosecutors grants Indigenous people the legal right to use the name of their ethnic group as their last name. Because of that, many of the Indigenous people interviewed in this report have as their last name the Portuguese name of their ethnic group, such as Gavião, Guajajara, and Ka’apor.

I. The Fight against Illegal Deforestation

Climate Change and the Amazon

For more than a decade, Brazil has identified the fight against illegal deforestation of the Amazon rainforest as a central component of its contribution to global efforts to mitigate climate change.

In 2016, following the adoption of the Paris Agreement on Climate Change, Brazil committed to reduce its greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 2025 to 37 percent of its 2005 levels, and 43 percent by 2030.[1] Deforestation is a primary source of the country’s GHG emissions, accounting for 46 percent in 2017, according to government data compiled by the Climate Observatory, an NGO.[2] Moreover, more than 90 percent of the deforestation in 2017 and 2018 was illegal, according to the government.[3] Brazil pledged in 2009 to reduce deforestation in the Amazon to below 3,925 square kilometers per year by 2020; in 2016, when it signed up to implement the Paris Agreement, it committed to reducing illegal deforestation in the Amazon region to zero by 2030.[4],[5]

Although Brazil succeeded in reducing deforestation in the Amazon by 83 percent from almost 28,000 square kilometers of forest destroyed in 2004 to less than 4,600 square kilometers in 2012, since 2012 deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon has climbed, reaching 7,500 square kilometers in 2018.[6] This is almost double the amount it had committed, in 2009, to reaching by 2020.[7] Between August 2018 to June 2019, deforestation increased by 15 percent when compared with the same period the year before, according to Brazil's National Space Research Agency, INPE.[8]

Success in curbing deforestation prior to 2012 resulted, in part, from the creation of protected areas – conservation reserves and Indigenous territories – encompassing hundreds of thousands of square kilometers throughout the Amazon region, where special legal restrictions on land-use protect the forest.[9] Brazil also stopped providing subsidized loans to rural producers in the Amazon who lacked legal title to the land or did not comply with environmental regulations.[10] But possibly the most important factors were the use of real-time satellite imagery to locate illegal logging sites and forceful law enforcement to shut them down.[11]

In recent years, this progress has been undermined by a variety of factors, including cuts to funding and personnel of the major enforcement agencies, an amnesty for illegal deforestation included in the 2012 Forestry Code, as well as by loggers adopting techniques for removing trees that are not as susceptible to detection by satellite surveillance.[12]

Environmental Law Enforcement and Forest Conservation

Brazil has a comprehensive legal framework for environmental protection. The 1998 Environmental Crime Law establishes criminal and administrative punishment for individuals and companies for harming the environment, such as harvesting timber in government-owned forests and transporting, buying, or selling illegally-harvested timber.[13] Punishment includes prison sentences for individuals and for companies, suspension of activities and a prohibition on signing contracts with the government.

Decree 6514 details what constitutes administrative environmental infractions and the corresponding fines. Under the Brazilian Forestry Code, private landowners in the Amazon region must maintain 80 percent of the forest on their property as a nature reserve.[14] They can only extract timber from the reserve if environmental agencies authorize a forest management plan of selective cutting of trees that will maintain biodiversity and forest cover and facilitate growth of native species.[15] In addition, they must maintain the forest around streams and lakes and other special geographic areas.[16]

Law 9985 regulates “conservation reserves,” nature areas with special restrictions on the use of land and water for environmental protection.[17] Committing an environmental crime in those areas is an aggravating factor. There are two types of conservation reserves: (1) Integral Protection Conservation Reserves, which bar human settlements but allow research and, in some cases, visiting; and (2) Sustainable Use Conservation Reserves, which allow people to live inside the reserve as long as they use resources in a sustainable manner. Federal, state, and municipal authorities can create conservation reserves after conducting technical studies about the area and, in most cases, public consultation.[18]

Indigenous territories are also protected areas, as the law prohibits non-Indigenous people from carrying out logging or any other economic activity inside them, and allows Indigenous peoples to use resources only in a sustainable way.[19] Brazil’s Constitution entrusts the federal government with the obligation to “demarcate” Indigenous territories.[20] Demarcation is an administrative process of legal recognition of lands “traditionally occupied” by Indigenous peoples.[21] The process includes conducting anthropological and other studies to assess the Indigenous people’s claim to the territory and to define the territory’s limits, and an approval process that ends with a decree by the president, the removal of any non-Indigenous resident from the territory, and the registration of the Indigenous territory as property of the federal government.[22]

There are multiple government agencies that play a role in enforcing this legal framework and curbing illegal logging in Brazil. At the federal level, these include:

- The Brazilian Institute of the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA), tasked with civil enforcement of federal environmental law throughout Brazil.[23] It can fine those who violate the law. It does not have criminal law enforcement authority, although under Brazilian law IBAMA agents — just like any other citizen — are legally authorized to detain someone in the act of committing an environmental crime and hand them over to police.[24]

- The Chico Mendes Institute for the Conservation of Biodiversity (ICMBio), manages and protects federal reserves.[25] ICMBio agents have authority to conduct civil enforcement of environmental law within federal conservation reserves and the surrounding buffer zone.[26]

- The Federal Police, in charge of criminal enforcement of environmental laws in federal areas, including Indigenous territories and federal conservation reserves.

- The Federal Attorney General’s Office, responsible for prosecuting illegal logging in Indigenous territories, federal conservation reserves, and other federal lands, since these are federal crimes. In 2018, the attorney general created the Amazon Task Force, a group of federal prosecutors specialized in combatting environmental crimes in the Amazon region.[27] The group only has one federal prosecutor working exclusively for the task force, while other prosecutors must fit it in along with their regular duties. Because of limited resources, the Task Force focuses mostly on fighting deforestation in southern Amazonas state.[28] Federal prosecutors have jurisdiction over criminal investigations in cases involving “collective rights and interests, especially those of Indigenous communities,” regardless of whether the crime occurred on federal land or not.[29] The federal attorney general can also request the Superior Court of Justice to approve the federalization of cases of serious violation of human rights that are not properly investigated and prosecuted by state authorities.[30]

- The National Indian Foundation (FUNAI), the federal agency that protects and promotes Indigenous rights. It plays a crucial role in environmental enforcement by alerting environmental agencies, police, and prosecutors when loggers encroach onto Indigenous territories.

At the state level, the government agencies involved in enforcing environmental laws include:

- Environmental secretariats, which promote environmental protection on state lands, manage state conservation reserves, and carry out environmental licensing at the state level.[31]

- State military police, which has specialized units that fight environmental crime by conducting patrolling operations in rural areas and detaining any loggers they encounter in the act of destroying the forest.

- State civil police, which investigates environmental crimes on state, municipal, and private lands.

- State prosecutors, who prosecute environmental crimes in those same areas.

IBAMA and ICMBio can fine loggers, confiscate equipment used for illegal logging, and, in extreme cases, burn that equipment when its transport is inviable or would put the environment or its agents at risk.[32] IBAMA and ICMBio often conduct joint operations with support from federal and state police. Federal and state police can detain people engaged in illegal logging anywhere.[33]

While these federal and state agencies were able to make important progress in curbing illegal deforestation prior to 2012, personnel and budget cuts have weakened their capacity to enforce environmental laws.

In 2009, IBAMA employed some 1,600 inspectors throughout Brazil.[34] By 2019, it employed 780.[35] Only a fraction of these inspectors is devoted to the Amazon region, leaving large swaths of rainforest with limited presence of IBAMA inspectors. For instance, there are just eight IBAMA inspectors for the western half of Pará, an area almost as big as France.[36] Similarly, the number of FUNAI staff has declined by about 30 percent since 2012, from 3,111 to 2,224 in 2019.[37]

The reduction in personnel has taken place in the context of reduced state funding for these agencies. From 2016 to 2018, IBAMA’s annual expenditures in real terms — corrected for inflation — fell by eight percent, and FUNAI’s by 11 percent.[38]

Organized Crime and Illegal Deforestation

Illegal deforestation in the Amazon is a multi-million dollar business that involves both illegal logging, illegal deforestation, and illegal occupation of public land.[39] A single trunk of ipê, the trees of the Handroanthus genus that are a preferred target of loggers for their hardwood, fetches between 2,000 and 6,000 reais (between US$500-$1,500).[40]

Over the past decade, loggers have relied on several tactics to evade enforcement of the laws restricting deforestation. One involves the use of lumber extraction methods that are less likely to be detected by satellite surveillance. They typically begin by cutting only the most valuable timber, opening only small clearings, and leaving other vegetation “to fool the satellite,” according to Luciano Evaristo, who served as the director of environmental protection at IBAMA for a decade, until January 2019.[41] While small-scale clearings accounted for only a quarter of deforestation in 2002, by 2012 they accounted for more than half, according to an estimate by the Climate Policy Initiative, an international think tank.[42] Loggers also build their camps under trees so that they are not visible from helicopters and keep cut timber in the forest and bring it out slowly instead of accumulating large quantities in sawmills, where it can be discovered.[43],[44]

The impact “is like termites,” discretely eating away the forest at a multitude of sites, Maranhão state federal prosecutor Alexandre Soares told Human Rights Watch.[45] Only once they have managed to remove all the valuable wood do they set fire to what remains, openly large swaths of land for cattle or, less frequently, farming.

Much of the illegal logging taking place in the Amazon today is carried out by criminal networks that have the logistical capacity to coordinate large-scale lumber extraction and deploy violence against those who would seek to stop them. IBAMA officials call these crime groups “ipê mafias,” a reference to the ipê wood that they harvest.[46]

Attorney General Raquel Dodge concurred.[47] “Organized crime is responsible for deforestation in the Amazon,” she said, explaining that the logistics of timber harvesting, in remote locations, transportation, and sale abroad require “an organization.”

Criminal networks provide the capital to buy heavy equipment and hire workers, coordinate with sawmills, and arrange methods to pass illegally-harvested timber as a legal product. They are often led by fazendeiros (ranchers or large farmers in Portuguese), who hire local men to work in the forest for weeks at a time, frequently under degrading and abusive working conditions.[48] They open paths within Indigenous territories and other federal and state forests using chainsaws, tractors, and trucks to extract the most valuable timber.[49]

If they succeed in removing the most valuable lumber without being stopped, the loggers or other members of the criminal network typically cut the remaining vegetation, a process that is labor-intensive and requires substantial investment.[50] Once cut vegetation is dry, they set it on fire. And then, they most often turn those areas into grass land for cattle; more than 60 percent of deforested areas end up as cattle ranches, while six percent are used for crops.[51]

The criminal networks may keep those lands, dividing them into smaller plots and fabricating titles to the name of frontmen.[52] Or they may raise cattle there for a few years, when the land is most productive, and then sell it, again with fabricated titles, a practice known as grilagem in Brazil, officials told us.[53] For this, they count on other actors in the criminal networks: experts in geoprocessing who forge land surveys to register lands occupied by fazendeiros. Some crime networks are also involved in illegal mining in the areas they control.[54] To protect and further their business, they sometimes bribe public officials and police.[55]

A crucial part of these criminal networks is the armed men who protect their illegal activities. “They are very similar to militias,” Diego Rodrigues Costa, a Mato Grosso public defender, told Human Rights Watch, referring to the violent criminal organizations that operate in Rio de Janeiro and other urban centers in Brazil, dominating geographic areas and using violence and intimidation against the local population.[56] Marco Paulo Froes Schettinto, executive secretary of the Indigenous rights unit at the Attorney General’s Office, concurred that some fazendeiros involved in illegal logging are forming “rural militias.”[57]

Like the urban militias, these crime networks wield considerable economic power, which they use to influence or control local politics, officials and residents told Human Rights Watch. [58] “In a town, you can have 20 sawmills supporting 400 workers and their families, which means up to 1,600 people directly dependent on the logging industry,” said an IBAMA enforcement agent.[59] State and federal officials said it is common for members of the crime groups involved in logging to assume positions as council members, mayors, and state representatives.[60]

Loggers launder timber by making it pass as legally-harvested lumber that ends up in domestic and, according to several Greenpeace investigations, international markets.[61] For that, they work through companies that use fraudulent documentation to obtain logging permits, such as overestimating the volume of timber in the area to be legally logged, according to officials and agroecology experts.[62]

A study by Brazilian and American forestry researchers that analyzed logging permits and timber volumes in Pará state — the largest timber producer in the Amazon — estimated that 74 percent of the 33,000 cubic meters of lumber licensed to be logged in 2017 was very likely overestimated.[63] The timber did not actually exist in the areas were logging was permitted, and the “surplus” licenses would be used to legalize illegally-harvested timber, the authors explained. In Maranhão, IBAMA officials told Human Rights Watch in 2017 that most of the logging permits in the Amazon region of the state were based on fraudulent information and had been cancelled.[64]

Fazendeiros raising cattle in illegally deforested and occupied land in the Amazon escape controls by either selling it to clandestine slaughterhouses, passing it for cattle raised in legal ranches, or selling it to cattle ranchers who specialize in cattle fattening and who in turn sell it to legal slaughterhouses.[65]

- A criminal organization deforested 180 square kilometers, an area the size of Washington, D.C., in the municipality of Boca do Acre in Amazonas state in the last few years, according to federal police.[66] Fazendeiros illegally logged in and occupied federal forests, and had five IBAMA employees on their payroll to protect their business, including the director of IBAMA in Acre state, according to the Amazon Task Force, the group of federal prosecutors specialized in combatting environmental crimes.[67] They also employed four state police officers as “a private militia” to protect their activities, said prosecutors. Using police cars, weapons, and uniforms, that militia threatened and attacked local residents — including attempting to kill a man, who suffered gunshot injuries but survived in March 2018, prosecutors allege.[68] Federal prosecutors charged 22 people with several crimes in June 2019, including forming a “criminal organization.”[69]

- A criminal organization deforested 290 square kilometers in the municipality of Altamira, in Pará, from 2012 to 2015, an area almost three times the size of Paris, according to IBAMA.[70] They deployed groups of 10 workers in public forests who lived in camps under degrading conditions and were paid only after felling all the valuable timber in the area, IBAMA reported.[71] The loggers kept some tall trees to preserve canopy cover and operated undetected by satellites. They eventually deforested the areas completely and registered the land with forged documentation under the name of frontmen, IBAMA said. Members of the criminal group allegedly raised cattle there themselves or rented out the land. The racket generated 1.9 billion reais (US$600 million at the time) from 2012 to 2015, said IBAMA. In 2016, federal prosecutors charged 23 people with forming a criminal organization, money laundering, provoking fires, and corruption, among other crimes.[72]

- A network of fazendeiros involved in illegal logging have gradually taken over much of the Areia INCRA settlement, in Pará, established in 1998 to provide plots to small families, according to an internal INCRA report obtained by Human Rights Watch.[73] Those fazendeiros use the settlement to access protected forests, residents told Human Rights Watch.[74] The Instituto Socioambiental, a Brazilian environmental NGO, estimated loggers used the Areia settlement to illegally extract 23,000 cubic meters of timber from the Riozinho do Anfrísio Reserve just in 2017, worth 208 million reais (US$63 million at the time).[75] The fazendeiros employ armed men to protect their activities and intimidate and kill those who obstruct their activities, community leaders reported.[76] “They have organized armed groups. It’s a militia inside [the settlement],” Daniel Alves Pereira, a resident, told Human Rights Watch (see Section II).[77]

- A network of fazendeiros had already illegally occupied federal land and exploited its timber when INCRA created the Terra Nossa settlement in Pará state more than a decade ago, according to community leaders in the settlement.[78] INCRA inspectors who visited the area in 2017 confirmed in an internal report, obtained by Human Rights Watch, that these fazendeiros were involved in illegal deforestation, illegal occupation of federal land, and illegal gold mining.[79] They carried out illegally-harvested Brazil nut trees and other valuable timber over the only road out of the settlement, according to the community leaders.[80] The loggers employ armed men who operate as “a militia” — one of the community leaders told Human Rights Watch — and are apparently responsible for threatening and residents who have threatened their interests (see Section II).[81]

- A fazendeiro who illegally harvested timber in the Gurupi Biological Reserve employed armed men to harass and attack the Rio das Onças community and expel them from their land in Maranhão state, the director of the Reserve told Human Rights Watch.[82] In 2015, the fazendeiro hired a retired police officer, who in turn hired two active military police officers to kill community leader Raimundo Santos, the fazendeiro later confessed to police (see Section II).[83]

- In Colniza, Mato Grosso state, fazendeiros and loggers who harvested timber illegally employed a group of hitmen known as “the hooded ones” to intimidate and attack local residents — even committing some killings — and expel them from their land, prosecutors said (see Section II).[84]

The Role of Indigenous Peoples and Other Local Residents

Indigenous peoples and local communities have always played an important role in enforcement efforts by providing government authorities with tips about illegal logging activities, according to IBAMA and federal police.[85] This role has become more crucial with the loggers’ use of tactics to avoid satellite detection and the decrease in the number of inspectors. Given the vastness of the Amazon forest in Brazil — 3.5 million square kilometers — “it’s simply impossible to deploy [IBAMA] agents to control all this territory,” said Luciano Evaristo in 2018, when he was director of enforcement actions at IBAMA. [86],[87] Instead, they need to rely on members of Indigenous and other local communities to report illegal logging activities to them.

Evaristo gave as an example a 2016 operation against loggers who had destroyed 290 square kilometers of rainforest in Altamira, mentioned above. It was only possible because the Kayapó Indigenous people reported the illegal activity; satellites had not detected the clearing of the forest, he said.[88]

Human Rights Watch saw firsthand the importance of information from local communities for enforcement efforts. In June 2018, following tips from an Indigenous leader, a Human Rights Watch researcher found a sawmill about five kilometers from Governador Indigenous Territory, and a few hundred meters from a busy dirt road on the outskirts of the small town of Amarante do Maranhão, in Maranhão state. It stood in a clearing, uncovered by vegetation. Nobody was there, but the tracks on which the saw was mounted were shiny and free of dust — a sign of recent use. A thick coat of sawdust covered everything else. The electrical wire bringing power disappeared into a wooded area, where the researcher could hear sawing. Human Rights Watch deployed a drone and, from the air, discovered a second sawmill. Local police told us there were no legal sawmills in Amarante. They said any sawmill operating there used illegally-harvested timber from Indigenous territories.[89] Human Rights Watch provided images and GPS location of the two sawmills to two federal police officers and a federal prosecutor in Maranhão in June and October 2018, but received no response.

Members of Indigenous communities tend to be among the most active in supporting enforcement efforts aimed at curbing deforestation, according to federal authorities.[90] This may explain why only three percent of all deforestation recorded from August 2017 to July 2018 in Brazil’s Amazon region occurred in Indigenous territories, even though those territories comprise 23 percent of the area.[91]

A 2016 study by the World Resources Institute, a nongovernmental research organization with headquarters in the United States, found that deforestation on lands securely held by Indigenous peoples was 250 percent lower than in other comparable areas of the Brazilian Amazon.[92] It also estimated that if Brazil secured existing Indigenous lands for the next two decades, it could avoid yearly greenhouse gas emissions derived from deforestation equivalent to taking more than 6.7 million cars off the road for one year.[93] The study concludes that demarcation and other measures to secure Indigenous lands can slow deforestation and reduce emissions.[94]

Yet, the demarcation process, which as a final step requires a presidential decree establishing the Indigenous territory as demarcated land, has slowed down in recent years.[95] Between 2007 and 2010, under President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, the federal government demarcated 77,000 square kilometers of Indigenous territories in the Amazon region. In the next four years, under President Dilma Rousseff, it demarcated 20,000 square kilometers. During Rousseff’s truncated second term, from 2014 to May 2016, it demarcated an additional 12,000 square kilometers. Under President Michel Temer, it demarcated just 192 square kilometers from May 2016 to December 2018. Since President Jair Bolsonaro took office in January 2019, the federal government has demarcated zero square kilometers, as of July 2019.[96]

CASE STUDY: The “Forest Guardians” of Maranhão

Shortcomings in Environmental Enforcement

The state of Maranhão lies on the eastern border of the Amazon region. The Amazon forest once covered about 110,400 square kilometers of the state, scientists estimate.[97] By 1988, when the National Institute for Space Research (INPE) started monitoring the Brazilian Amazon, 61,100 square kilometers of this forest had been cleared – the lands since devoted to agriculture and cattle ranching. Since 1988, an additional 24,600 square kilometers have been destroyed, leaving 24,700 square kilometers of rainforest in the state.[98]

Of the remaining Amazon forest in Maranhão, almost half lies within the boundaries of Indigenous territories. An additional quarter of the forest lies within the ICMBio Gurupi Biological Reserve and other protected areas, and the rest in private land and in land reform settlements established by the National Institute of Colonization and Land Reform (INCRA), a federal agency, to provide plots to poor small farmers.[99]

During the last decade, federal and state enforcement agencies have worked together to curb illegal logging in Maranhão. With the assistance of the federal and state police, IBAMA and ICMBio have carried out a dozen major raids against illegal loggers operating on Indigenous lands and in the Gurupi reserve, seizing thousands of cubic meters of illegal timber and destroying trucks, tractors, and sawmills.[100] The Maranhão state environmental agency (SEMA) has revoked most forest-management licenses in the Amazon region of Maranhão after finding they were used to disguise illegally-logged timber as wood lawfully obtained in authorized areas.[101]

But environmental officials and police officers interviewed by Human Rights Watch in Maranhão acknowledged that enforcement efforts are insufficient.[102] The chief problem is the lack of resources and staffing to carry out their job, they said.

For the entire state of Maranhão, IBAMA had only nine field inspectors in 2018 to monitor environmental crime of all kinds — not only deforestation. Maranhão is the eighth largest state in Brazil, totaling about 332,000 square kilometers, making it larger than Italy.[103] An IBAMA official in São Luís, the state capital, told Human Rights Watch that the agency conducted only four monitoring operations a year in Indigenous territories, which maintain the largest blocks of remaining forest in Maranhão besides the Gurupi Biological Reserve, which is monitored by ICMBio agents. Even for those operations, the official said, IBAMA had to request support from staff in other states and from state police.[104]

In 2018, the Maranhão state environmental agency, SEMA, had at most 30 inspectors to monitor environmental crime, a high-level SEMA official told Human Rights Watch.[105] While SEMA does not have authority to operate inside Indigenous territories, the agency is responsible for monitoring the borderlands outside those territories. These are the areas in which illegal sawmills are most often located.

The federal police chief in Imperatriz told Human Rights Watch that she lacked manpower to respond to all reports of environmental crimes. She said 30 federal police officers were stationed in Imperatriz, including those in charge of administrative tasks. That number is “clearly insufficient,” she said.[106]

In 2016, FUNAI signed an agreement with the Maranhão state government to conduct joint state police and FUNAI operations against environmental crime within Indigenous territories.[107] But the agreement was never implemented because FUNAI could not fund the logistics or the daily allowance for police officers.[108]

In 2018, FUNAI had 26 employees in Maranhão, where 37,000 Indigenous people live. The agency had 12 vehicles, but ten were out of commission due to lack of maintenance. Eliane Araújo, then coordinator of FUNAI in the state, told Human Rights Watch that the FUNAI office in Maranhão had no yearly budget to maintain its vehicles and to develop its work. [109] “I prepare the planning, but we don’t follow it,” Araújo explained, because she depended on the FUNAI headquarters in Brasília to release the funds, and they did not. “Indigenous people want the presence of FUNAI in their territories, but we are not there” for lack of resources, she said.

For travel by any employee, Araújo had to ask for authorization ten days in advance. This made it impossible to respond quickly to any urgent situation, such as a call from Indigenous people who encounter loggers in their territory, she said. The day Human Rights Watch interviewed Araújo, she said she was going to travel all night by bus from Imperatriz to São Luís for a meeting, with a ticket she would pay for herself.[110] “It’s the worst moment at FUNAI in my 30 years here,” said Araújo.

Federal prosecutors in Imperatriz denounced the “chaotic” situation in Governador and Araribóia Indigenous Territories and accused federal and state authorities of failing to both fight illegal logging and protect Indigenous people.[111] The prosecutors pointed out that FUNAI and IBAMA lack sufficient funding to execute their duties.

Indigenous Peoples Defend the Forest

The Tenetehara, Pyhcop Catiji, and Ka’apor people of Maranhão consider land crucial for their survival. They depend on it for crops, including mandioc, rice, açaí palm, pumpkins, and beans. The land also provides them with fruits, fish, and animals; building materials, natural medicine, and materials for handicrafts; pigments for body paints; and raw material for musical instruments that they use in rituals. More than a source of materials, the land is the essence of their very culture; songs, dances, and ceremonies are about nature and their place in it, now and in the afterlife.

“The forest is our home; it heals our soul. Without it, we are nothing,” said Iracadju Ka’apor, a Ka’apor village chief.[112]

Eýy Cy, a Pyhcop Catiji village chief, told Human Rights Watch of the sadness he feels when he discovers areas deforested by illegal loggers within Governador Indigenous territory:

“I feel pain in my heart (when I see it) because we, the Pyhcop Catiji people, believe there is life after death, that our spirits transform themselves into trees, into animals. So, it is not just a tree, not just a forest that is there. What is there is a life, my ancestors’ lives.”[113]

The egregious shortcomings in enforcement by state and federal authorities within Indigenous lands in Maranhão has led the Tenetehara, Ka’apor, and Pyhcop Catiji Indigenous peoples to step up efforts to protect the forest.

The Tenetehara, one of the largest Indigenous peoples in Brazil, live in 11 Indigenous territories in Maranhão, the largest of which are Araribóia and Caru. These territories are home to around 12,500 Tenetehara people and 500 Awá, also known as Guajá, including two groups in voluntary isolation.[114] The Ka’apor live in the largest Indigenous territory in Maranhão, Alto Turiaçu Indigenous Territory, where there are also some Awá and Tembé, numbering about 2,100 people in total.[115] A thousand Pyh Cop Catiji people and almost 600 Tenetehara live in Governador Indigenous Territory.[116]

These four Indigenous territories, together with Awá Indigenous Territory and the Gurupi Biological Reserve, comprise most of the remaining Amazonian rainforest in Maranhão.

In Alto Turiaçu, Araribóia, Caru, and Governador Indigenous territories, Indigenous peoples have created patrols that they refer to as “Forest Guardians.” The guardians are community members who patrol the land in groups of up to 15 people, mostly men, in trucks, on motorcycles, in boats, and on foot, some of them equipped with GPS.[117] They identify sites of illegal deforestation and provide authorities with names of loggers from towns around their territories.[118] Sometimes they lead police to logging sites.

Patrolling the forest is often an arduous undertaking, according to members of the Forest Guardian patrols. On some patrolling trips, they sleep in the forest for weeks at a time. Some patrols lack money for gasoline and equipment, and for sustaining the guardians’ families when they are away.[119]

To make it easier to patrol areas where there may be logging, the Ka’apor have built villages in strategically-located areas near the border of their land formerly occupied by loggers to facilitate forest protection.[120] Similarly, the Tenetehara of Araribóia Indigenous Territory are constructing a base in a remote area of their land that has no villages and where illegal logging activity is at its most intense.[121]

In Caru Indigenous Territory, a group of twenty-five “Women Warriors” are learning to pilot and deploy drones to detect deforestation.[122] Some of them also go on patrol with the men.

Forest guardians have collaborated successfully with police on numerous occasions, according to community leaders and federal and state officials.[123] The collaboration has included leading state police to logging sites in their lands.[124]

- In 2016, Caru forest guardians led members of the environmental police battalion of the Maranhão military police through their territory, finding a logging truck, a tractor, and four men logging illegally.[125] The police officers burned the vehicles but let the loggers go because they were in a very remote location and said they could not bring them to a police station.[126]

However, even when the forest guardians do the work of locating sites of illegal deforestation or identifying those responsible, the authorities often fail to respond in a timely manner, if at all, forest guardians and Indigenous leaders told us.[127]