Summary

This report examines the responsibility of four European development banks for abusive practices on oil palm plantations in the Democratic Republic of Congo. These banks – BIO, from Belgium; CDC Group, from the United Kingdom; DEG, from Germany; and FMO, from the Netherlands – are among the ten largest bilateral development financial institutions in the world, controlling billions of dollars in investments across more than 2,000 projects in developing countries. Human Rights Watch found that the banks have failed to ensure that the palm oil companies they finance in Congo are respecting the basic rights of the people who work and live on or near their plantations.

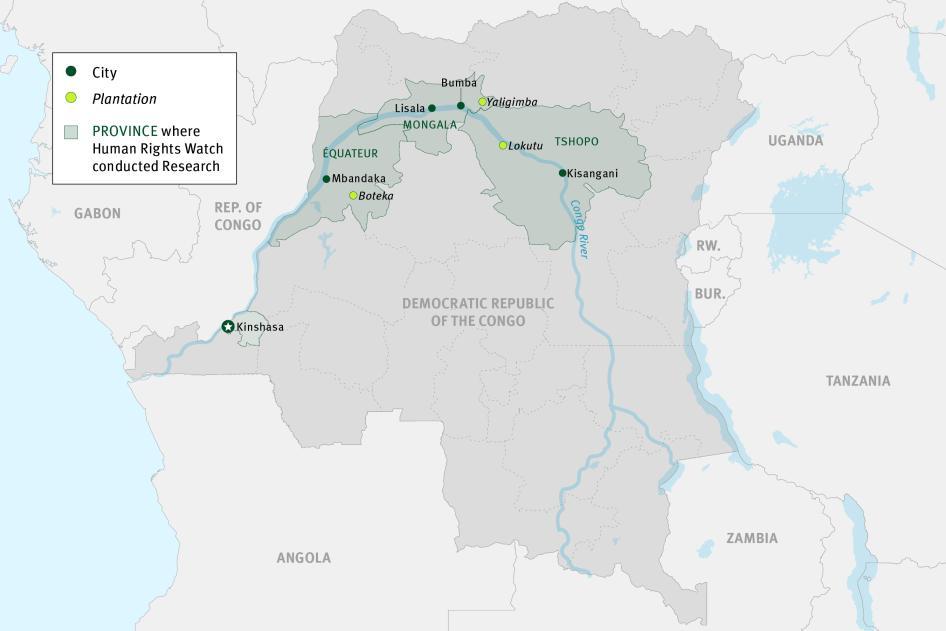

Since 2013, the four banks have invested a total of nearly US$100 million in the palm oil company Feronia and its subsidiary Plantations et Huileries du Congo S.A. (PHC) (together “the company”), which operates three oil palm plantations spanning over 100,000 hectares in northern Congo: “Boteka,” “Lokutu,” and “Yaligimba.” In addition to being an investor, CDC Group is also a shareholder in Feronia: it currently owns 38 percent of the company. The three plantations employ a total of nearly 10,000 workers. Approximately 100,000 people live on or within five kilometers of their property.

During field research in Congo between November 2018 and May 2019, Human Rights Watch visited the company’s three plantations and interviewed more than 200 people, including 102 PHC employees residing on or near the plantations, 20 Feronia and PHC executives and company managers, and 25 government officials, among others. Human Rights Watch also reviewed extensive documentary evidence, including social-environmental impact reports the company submitted to Congolese authorities.

Human Rights Watch found that lack of proper oversight by the banks has enabled Feronia and its subsidiary PHC to commit abuses and environmental harm that infringed upon health and labor rights. These abuses include exposing more than 200 employees to toxic pesticides without adequate protection; not providing employees exposed to hazardous materials with the results of medical examinations; and engaging in abusive employment practices that place many workers under the extreme poverty line. The plantations’ palm oil mills also routinely dump untreated industrial waste and may have already contaminated the only drinking water source of local communities.

Congolese authorities have failed to ensure PHC’s compliance with domestic laws regulating labor and environment conditions and to protect the rights of plantation workers and local residents.

While the Congolese government has primary responsibility for protecting the rights of PHC workers, the development banks are also obligated to ensure that the companies they finance are not engaging in abusive practices, an obligation they have failed to meet. This is partly the result of structural failures in the way the banks operate: most of the banks do not assess the potential human rights impacts of the projects they invest in and all do little to disclose relevant information to communities that might be impacted. The banks also do not ensure that affected communities have access to effective remedies when the companies they finance engage in abusive practices.

Development banks could play an important role in promoting economic opportunities in Congo, a country where two-thirds of the 84 million residents live in poverty, 7.7 million are severely food insecure, and 4.5 million have been internally displaced due to armed conflict. As one the five largest private employers in the country – and the largest in the agricultural sector, which employs most of the working population – PHC’s palm oil plantations are an important source of economic opportunity. However, by failing to ensure that PHC is complying with international standards and domestic law regulating employment and environmental practices, the banks are not fulfilling their obligation to protect rights, thereby compromising their stated mission to advance sustainable development.

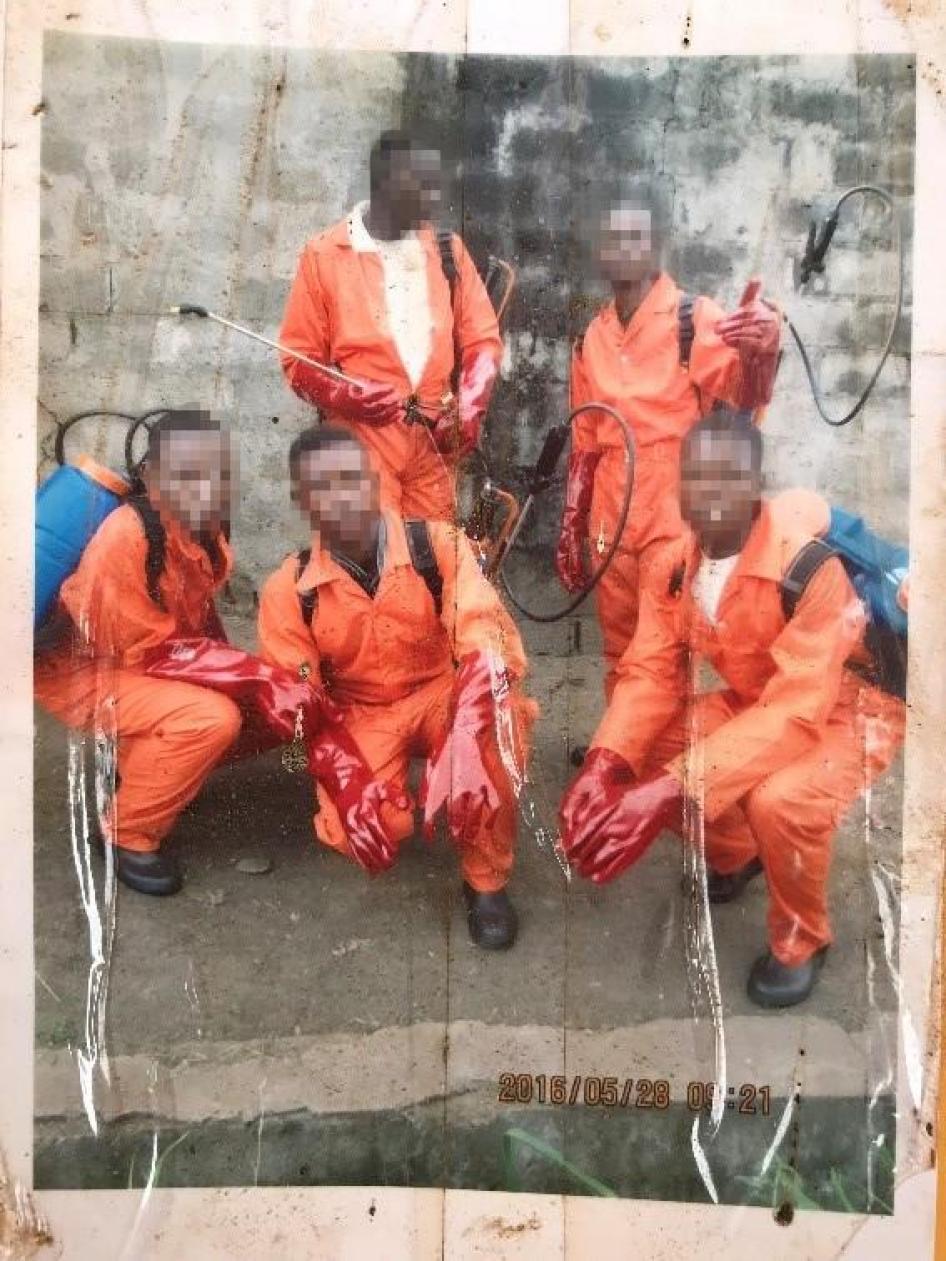

Workers Exposed to Toxic Pesticides

Half of the active ingredients in the nine pesticides that PHC uses in its plantations are considered hazardous by the World Health Organization (WHO), including some that may cause severe damage to the eyes. Three of the pesticides contain active ingredients that are considered cancer-causing by the WHO or other recognized health authorities. In August 2019, regulators recommended to the European Commission that approval for one of these chemicals be revoked; German authorities said in September they would completely phase out another of these substances by 2023.

As of May 2019, at least 245 PHC male contract employees were working with pesticides across the three plantations. Of these, 213 workers apply these toxic chemicals six days a week using a 16-liter backpack sprayer, each treating 300 to 600 palm trees per day. Thirteen team leaders supervise them on site. Fifteen workers are responsible for mixing pesticides in their purest form to create the formula their team members spray. Every day, the mixers create 200 gallons (the equivalent of nearly 800 liters) worth of formula.

Given the risks to human health, the WHO has developed standards regarding appropriate protective equipment for the use of pesticides in agriculture. Similarly, Congolese law requires that employers provide workers with appropriate protective equipment for their occupation and ensure special medical monitoring for workers in hazardous occupations. PHC’s own policies elaborate on the company’s institutional commitment to protect the health of their workers and prescribe specific equipment for workers who apply pesticides.

Human Rights Watch interviewed 43 workers on specialized pesticide teams employed by PHC, as well as the manager of one of these teams. Researchers also inspected the pesticide teams’ protective equipment and reviewed the training manuals PHC distributed to them. After consulting with occupational and public health experts, Human Rights Watch concluded that the equipment workers received was not consistent with WHO standards, Congolese law, or the company’s own policies.

Workers described a wide range of health problems that they had experienced since they began working with pesticides. These included both conditions that developed immediately after spraying pesticides and chronic conditions that emerged over time.

- Most of the workers who were between the ages of 25 to 46 said they had become impotent since they started their job.

- A number of workers described skin irritation, itchiness, and blisters immediately after the pesticides came into contact with their skin.

- Several workers described pain and irritation in their eyes while applying pesticides; others said their vision had diminished or become blurred since they started the job.

- Other workers said they experienced shortness of breath, elevated heart rate, headaches, weight loss, and chronic fatigue.

Some of these health problems are consistent with risks posed by the active ingredients in the specific pesticides sprayed by PHC workers, such as skin and eye problems. Other health problems such as impotence, shortness of breath, headaches, and weight loss are consistent with exposure to pesticides in general, as described in scientific literature.

Human Rights Watch research found that PHC has not provided workers with information necessary for them to understand the short and long-term health risks associated with their jobs or to consent to these risks. Though these workers are subject to special medical oversight from company doctors, most of those interviewed by Human Rights Watch said they did not receive the results of their medical examinations, even after they repeatedly asked for them, leaving them in a state of uncertainty about their health. The remainder did not say if they had received their results.

Dumping Untreated Waste

At least two of PHC’s three palm oil mills dump untreated waste into rivers and streams and near the homes of workers, according to Feronia and PHC staff. The company’s waste disposal procedures do not appear to be compliant with Congolese law or with international human rights standards for the conduct of business. Nor are they apparently compliant with commercial good practice expected from appropriately designed, operated, and maintained facilities operating under normal conditions, according to guidelines designed by the World Bank Group.

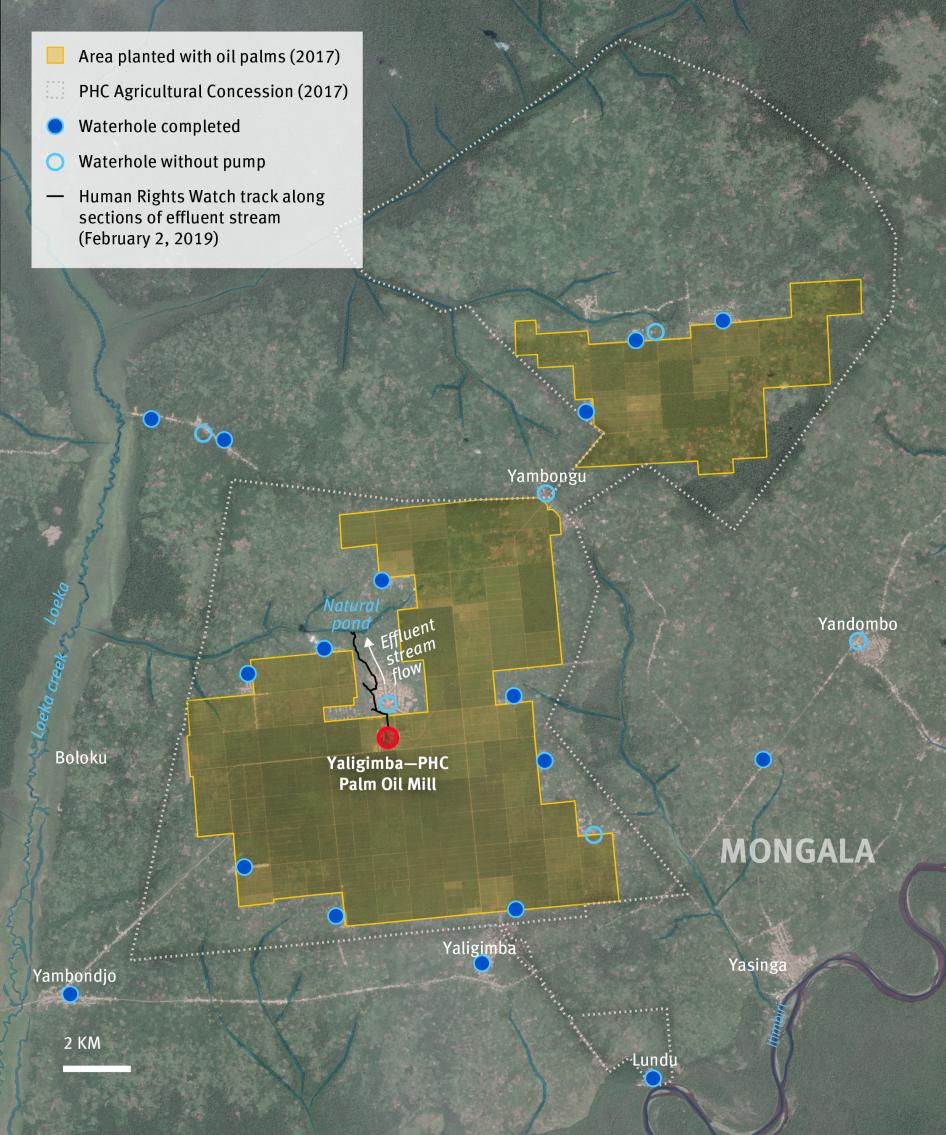

At the Yaligimba plantation, the company dumps its waste in a narrow channel beside the Mindonga workers’ camp, a settlement behind their palm oil mill. The effluents produce a putrid smell and fumes that pervade hundreds of homes on each side of the channel where workers live with their families. The stream of effluents continues its course for five kilometers before flowing into a natural pond. There, women and children bathe and wash their clothes and cooking utensils.

From this pond, the effluents flow through a channel to Loeka stream, west of the palm oil mill, which Human Rights Watch found after pinpointing GPS coordinates in the course of field research and analyzing satellite imagery of the site.

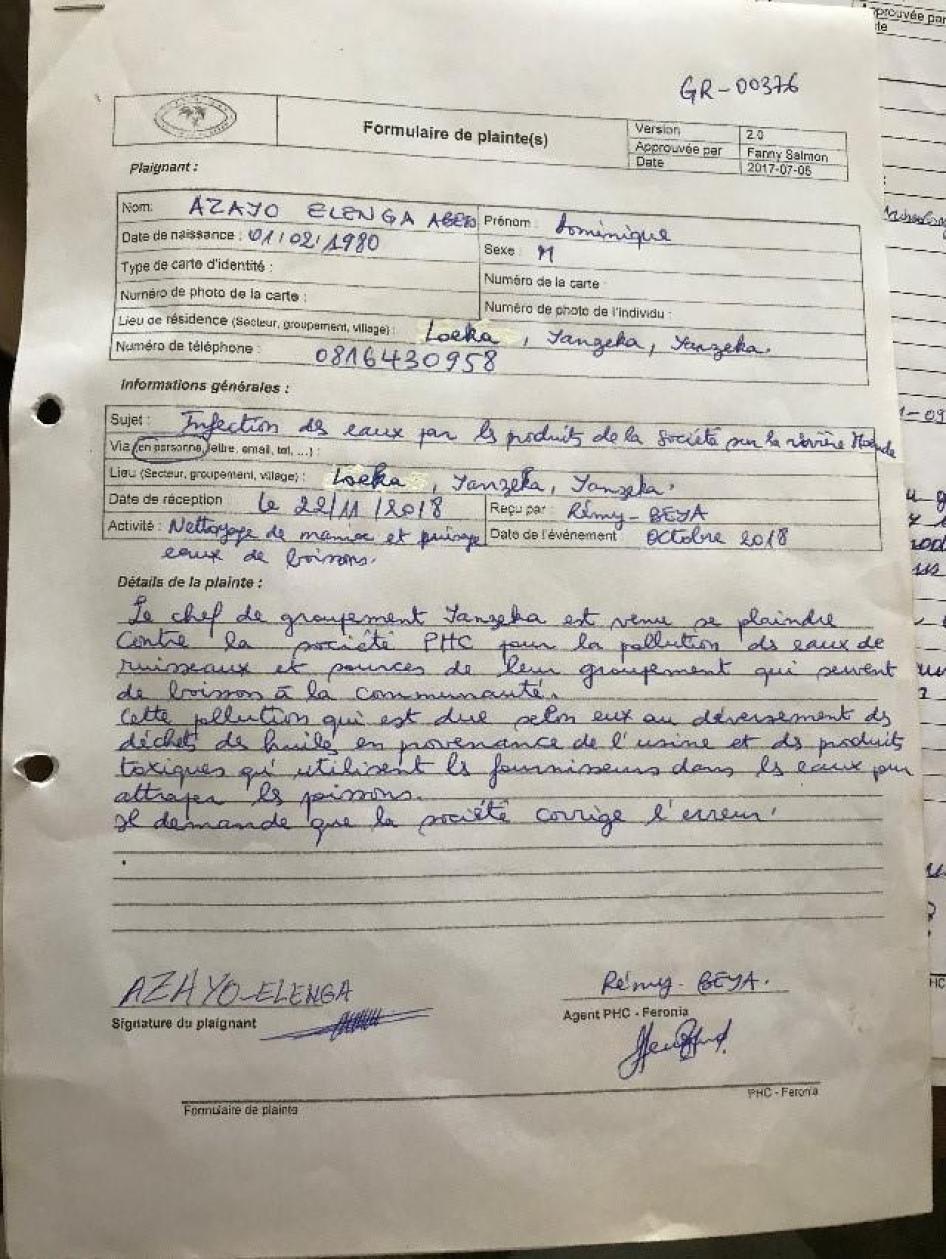

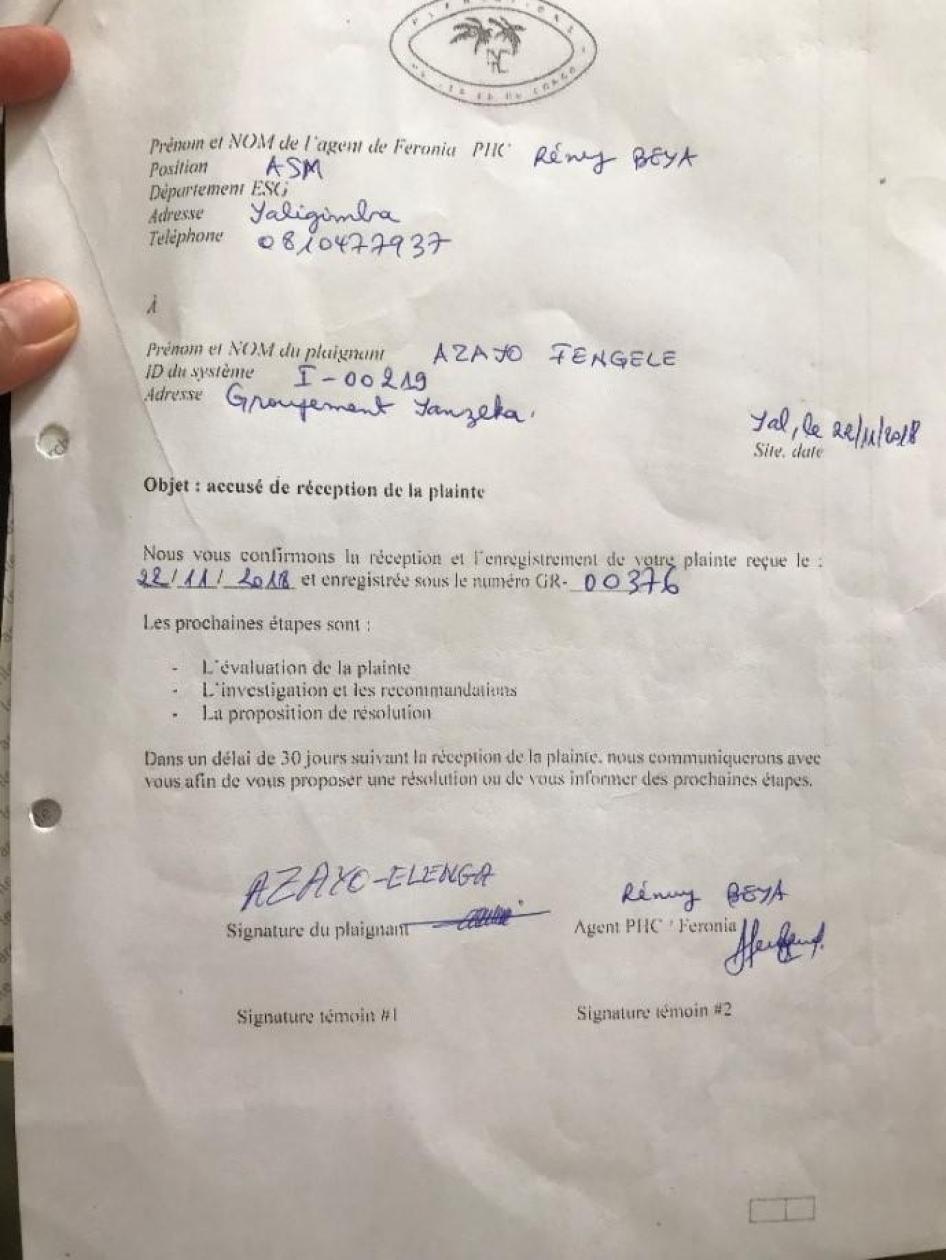

There are no sources of drinking water other than Loeka stream in Boloku, a village of several hundred families downstream from the PHC mill, residents told Human Rights Watch. Boloku’s customary leader filed a formal complaint with PHC in November 2018, alleging the stream was polluted by the company’s waste discharges. At the time Human Rights Watch interviewed him, three months after he filed the complaint, the company had not taken any action, he said.

In 2018, the year Boloku villagers filed the complaint, the production in Yaligimba quadrupled between January and November, according to the company’s tax declarations – with the volume of waste discharged into the water growing proportionally. Boloku’s customary leader told Human Rights Watch that residents observed oily waste in the water and that the color of the water had changed. “We don’t want to drink it anymore,” he said.

The World Bank Group’s Environmental, Health and Safety (EHS) Guidelines on Vegetable Oil Production and Processing indicate palm oil mill effluents should be treated to bring them into compliance with nine parameters before releasing them into the environment. In its two largest plantations, PHC only controls effluents for one of these nine parameters – the content of palm oil – to avoid dumping their product.

The European development banks imposed compliance with the International Finance Corporation (IFC) Performance Standards and the EHS Guidelines on Feronia and PHC as part of their contractual obligations. The guidelines “are achievable under normal operating conditions in appropriately designed, operated, and maintained facilities,” according to the IFC.

The company’s practice of dumping untreated effluents endangers the health of villagers who must rely on polluted water and undermines their ability to enjoy private, family, and cultural life in their homes without being overwhelmed by a putrid smell. If unchecked and untreated, effluent dumping could, over time, also cause fish to suffocate and die, or cause large growths of algae that can adversely affect the health of those who come into contact with polluted water or consume tainted fish.

Labor Rights Violations and Extreme Poverty Wages

In addition to failing to provide adequate equipment to employees who work with pesticides, PHC has not provided basic protective equipment to day laborers, who are employed and paid per day and make up the majority of the company’s workforce. Day laborers often set out on the plantation without gloves or boots, making them vulnerable to snake and spider bites, machete and thorn prick injuries, and trauma.

Female plantation workers appeared to be disproportionately impacted by the lack of protective equipment. Speaking of the group of women with which she works, a female laborer from Boteka plantation told Human Rights Watch, “We work without boots, without gloves – with our bare hands, sometimes the fruits [we have to pick up] fall on cows’ or people’s excrement.” In a visit to the Boteka palm oil mill, Human Rights Watch researchers observed that women were the only employees working without any protective equipment.

The range of practices that put workers’ health and safety at risk contravene Congolese labor law and international human rights standards, as well as the company’s policies. However, PHC workers face considerable barriers when seeking redress for harms incurred, as the remote location of the plantations makes it physically difficult for them to file complaints. In addition, government agencies in charge of enforcing labor law are underfunded, understaffed, and often unable to travel to the plantations to conduct inspections. Further, some of the workers that Human Rights Watch interviewed expressed mistrust toward their trade union representatives, who in some instances are also part of company management.

PHC has made routine use of temporary contracts in apparent violation of Congolese law, which states that companies can hire day laborers for no longer than 22 days in any two-month period, after which a company must offer an indefinite contract. Many workers told Human Rights Watch they were employed as day laborers on temporary contracts for years at a time, including as long as ten years in one case. At one plantation, Congolese authorities imposed a hefty fine for this illegal practice and ordered the company to provide indefinite contracts over the course of two years to 1,500 workers. In December 2018, PHC had nearly 7,000 day laborers.

Day labor schemes preclude cash benefits that are otherwise owed to contract workers under the collective bargaining agreement, such as end-of-year bonuses and statutory annual raises. Day labor schemes then result in significantly lower wages for workers that keep them below the extreme poverty line of US$1.90 per day, as defined by the World Bank. While PHC’s director general said day laborers are paid on the same scale as contract workers, several day laborers told Human Rights Watch the agreement with the company was to be paid 2,000 FC (US$1.20) per day, which is lower than the lowest paid contract workers.

Among plantation workers, female laborers reported the lowest monthly salaries, ranging between 12,000 FC (US$7.30) and 30,000 FC (US$18.75). A former manager who supervised over 200 plantation workers in Boteka told Human Rights Watch that women were mainly employed as fruit-picker day laborers, that the company pays them 30 FC (US$0.01) for every sac of 10 kilos, and that “15 sacs per day is already too hard to accomplish.” The maximum a woman in this role can earn is 15,000 FC (US$9.04) per month, he said.

Most Congolese live in poverty, and the company provides employment for people who otherwise might be jobless. But the investment banks have consistently stated that one of their primary objectives when they invested in Feronia and PHC was to create decent jobs and promote development. CDC group said that “improving the conditions and rights of workers” was “at the heart” of their investment, in accordance with their development mandate. But contrary to the banks’ development mandate, workers in all three plantations, both men and women, told Human Rights Watch that their low wages did not enable them to meet even basic needs, and that they could not afford to provide their families three meals a day.

Lack of Oversight and Enforcement

Congolese authorities have not adequately enforced domestic labor and environmental laws that would help protect workers and communities from the abuses documented in this report. These include the rights to health, to water, and to information, as well as their labor rights. Provincial authorities cited lack of resources and staff as the most common cause for deficient monitoring, highlighting the need for national authorities to provide adequate resources at the local level.

The European development banks, which their respective states wholly own or have majority-ownership, have an extraterritorial obligation to uphold international human rights law. International standards obligate states, and thus the investment banks, to take steps to prevent and provide redress for rights abuses that occur outside their territories due to the activities of business entities over which they can exercise control. KfW, the German-owned development bank that owns and supervises DEG, explicitly recognizes its extraterritorial obligations in its human rights declaration, but has still fallen short in protecting rights.

As a practical matter, the banks that invested in Feronia and PHC can exercise control on decisive operational matters through the conditions they attach to their lending and by monitoring company compliance with these conditions – thereby taking steps to prevent and redress infringements of rights.

The banks conducted due diligence to assess social and environmental risks that could pose a liability to themselves as investors, and they evaluated the gap between the companies’ practices and international industry standards. However, neither of these assessments are designed to prevent infringement of human rights that could result from business activity, as would human rights-specific due diligence.

An Environmental, Social and Action Plan (ESAP) was prepared based on the social and environmental assessments. The ESAP’s objective is “to ensure that over time Feronia reaches compliance with international standards and law,” specifically Congolese law, the 2012 IFC Performance Standards, the EHS Guidelines, and the criteria to obtain certification from the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), a certification initiative for palm oil producers wishing to adhere to labor, social, and environmental industry-specific standards.

The ESAP could be the instrument to ensure that the banks’ investments do not support activities that cause or contribute to human rights abuses. Human Rights Watch considers that an ESAP should be prepared on the basis of environmental, social, and human rights due diligence so that the banks may fulfill their duty to protect rights. To effectively prevent abuses, an ESAP should set minimal social and environmental standards for the company’s operations with a clear timeframe for these standards to be met. In addition to establishing monitoring mechanisms, it should also define consequences in the event there are serious violations of the company’s contractual obligations. In addition, an ESAP should establish enforceable and accessible remediation avenues for people who have suffered rights abuses from bank-funded commercial activities.

On grounds of commercial secrecy, the banks have not disclosed their due diligence assessments, nor the mitigation measures they agreed the company would implement. So long as they shield this information, it is difficult – if not impossible – to effectively monitor whether they are meeting their human rights obligations. This is particularly concerning for investments that are deemed “high risk” under the IFC environmental and social categorization, as PHC has indeed been classified by FMO, because of their “potential significant adverse environmental or social risks and/or impacts that are diverse, irreversible, or unprecedented.” Disclosing such assessments would not be unusual – the IFC and World Bank publish social and environmental impact assessments, or their equivalent, for all their projects.

This opacity means that Congolese and European government oversight agencies have had limited access to information on the human rights risks associated with investments, or the documentation that lays out the agreement between the banks and their clients. Potentially affected communities do not have access to information on how development banks identify, prevent, or mitigate the human rights impacts associated with investments, what these impacts could be, and how these impacts could affect their rights and livelihoods. Civil society groups have been prevented from scrutinizing whether public funds invested in the development banks are enabling activities that cause or contribute to human rights violations abroad.

The four European development banks have complaint mechanisms that provide them with feedback on whether they have acted in compliance with their policies and whether these policies are adequate to prevent negative social and environmental impacts. Yet, these mechanisms have multiple weaknesses:

- They do not have the authority to compel banks, or the businesses in which they invest, to participate in dispute resolution processes or to implement the agreements reached through these processes;

- They cannot reach a determination of fault or decide liability for abuses;

- They are chiefly available online, and the banks do little or nothing to publicize their existence for potentially affected people, rendering the mechanism considerably inaccessible for vulnerable rural communities;

- In the case of CDC, the mechanism does not provide any guidance to complainants on timeframes, types of resolutions they might be able expect, or guarantees against retaliation or reprisal when the complaint is brought by an external party, and the authority responsible for investigating complaints submitted through the mechanism is part of the bank’s management structure, instead of being an independent authority, compromising its impartiality. In addition, CDC does not publish details of the complaints.

The banks said they encourage the creation and implementation of effective grievance mechanisms at the company level so that businesses continue operating responsibly after development banks divest. While it is undoubtedly important for such mechanisms to exist at the company level, this does not relieve the banks – or the government authorities that oversee them – of their obligation to provide remedy and to create avenues for accountability for their role in supporting activities that caused or contributed to abuses. The banks and government oversight authorities should strengthen these mechanisms to create or provide genuine remediation avenues.

Key Recommendations to BIO, CDC Group, DEG and FMO

The four European development banks should undertake structural reforms to ensure that they are meeting their human rights obligations to prevent and mitigate abuses by companies in which they invest, such as those documented in this report.

Specifically, the banks should:

- Adopt human rights policies that acknowledge their extraterritorial human rights obligations, in the case of BIO and CDC Group, or modify their existing human rights policy to acknowledge extraterritorial obligations, in the case of FMO;

- Consistently conduct human rights due diligence prior to investing in a project and disclose, at a minimum, summaries of these risk assessments, as well as the mitigation measures they have adopted to address these risks;

- Ensure this information reaches potentially affected communities, and that it is also made available to government agencies that have oversight over the companies;

- Strengthen their grievance mechanisms so they are effective accountability avenues, and adopt anti-retaliation policies that protect activists from backlash when they bring forth complaints; and

- Adopt policies on decent work that compel investees to pay living wages, so that their investments meet their development mandate.

To the Governments of Belgium, Germany, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom

The governments that wholly-own or majority own these banks should ensure that nothing in their domestic legislation prevents the banks from engaging in structural reform that would enable them to meet their human rights obligations.

To the Government of the Democratic Republic of Congo

The government of Congo has the primary responsibility to protect the rights of workers and communities impacted by PHC operations, specifically to:

- Ensure that provincial representations of the Environment and Labor ministry are appropriately staffed and resourced, so they are able to conduct regulatory inspections and enforce the law;

- Investigate allegations of labor rights violations and environmental contamination; and

- Adopt a living wage for agricultural workers.

To Feronia and PHC

Feronia and PHC should engage in reform to prevent, mitigate, and address abuses on their plantations. The company should:

- Ensure that all workers have appropriate and complete equipment that adequately protects them from the hazards of their occupation;

- Ensure that laborers who work with toxic chemicals have access to adequate information to understand the risks associated to their job, that they promptly receive all test results of medical examinations, and that they are not forced to work without adequate equipment;

- Treat all waste in accordance with good industry standards and Congolese domestic law;

- Effectively address complaints about water contamination with a view to provide reparations to affected communities; and

- Ensure access for Congolese authorities to all company sites whenever they conduct regulatory inspections, in line with domestic law.

Methodology

This report is based on field research conducted by Human Rights Watch researchers for a total of eight weeks between November 2018 and May 2019 in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Researchers visited each of PHC’s three plantations: Boteka in Équateur province, Lokutu in Tshopo province, and Yaligimba in Mongala province. In every case, researchers obtained consent from the highest-ranking company executive on site to remain inside or within proximity of the plantation. Human Rights Watch also conducted interviews with public officials in the capitals of the three provinces where the plantations are located – Mbandaka, Kisangani, and Lisala, respectively. Researchers also interviewed company executives, public officials and diplomatic personnel in Kinshasa, the national capital, in addition to telephone interviews with representatives of nongovernmental organizations (NGO) and academics.

Human Rights Watch researchers interviewed 206 people for this report, including 102 PHC workers, of whom 98 were plantation workers and four were factory workers. Nine of the workers interviewed were women. The workers performed various occupations, including applying pesticides, harvesting fresh fruit bunches, weeding the area around palm trees, and gathering fruits on the ground. Interviews were conducted in French or in Lingala – the most widely spoken language in the three plantations – via an interpreter.

All interviewees provided oral informed consent and were assured that they could end the interview at any time or decline to answer any question. We have withheld workers’ names to protect them from possible reprisals. Interviewees were not compensated, but some who traveled to meet researchers were reimbursed for transport expenses.

Human Rights Watch researchers also interviewed a total of 20 Feronia and PHC executives and managers, including the then-Feronia chief executive officer (CEO), the PHC director general (DG), plantation managers, environmental managers, factory managers, human resources directors, and laboratory chiefs in the three plantations we visited and in Kinshasa. In addition, we interviewed two former PHC managers who worked in Boteka and Lokutu. We also interviewed 16 health workers employed or contracted by PHC, including three doctors, one in each plantation.

Human Rights Watch researchers conducted interviews with a total of 25 Congolese public officials from the Ministry of Labor, Employment and Welfare, the Ministry of Industry, the Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development, the Congolese Agency for the Environment, the National Commission for Human Rights, and national and provincial tax authorities across Bumba, Kinshasa, Kisangani, Lisala, and Mbandaka. We interviewed these officials regarding their attributions and, specifically, their oversight and law enforcement role over PHC. We also asked them about relevant Congolese laws and regulations that are applicable to PHC operations.

Human Rights Watch also met with a total of seven diplomatic personnel from the embassies of Belgium, Germany, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom in Kinshasa to understand their role in regard to their countries’ development banks’ financial participation in Feronia and PHC.

On March 21, 2019, Human Rights Watch requested information from Feronia’s CEO on Feronia and PHC policies, corporate governance, workers’ compensation, and staff composition, as well as environmental protection and mitigation measures for their operations. The company responded on May 6, 2019 with a letter and 71 documentary pieces. On September 30, 2019, Human Rights Watch sent a summary of our findings to Feronia and PHC requesting information on the steps taken to address the human rights issues documented in this report. The company had not replied at the time of publication.

Between February and May 2019, we requested information from the Belgian Investment Company for Developing Countries SA/NV (BIO), CDC Group, the Deutsche Investitions- und Entwicklungsgesellschaft mbH (DEG), and the Nederlandse Financierings-Maatschappij voor Ontwikkelingslanden (FMO) regarding their participation in Feronia and PHC. The four banks responded in writing between February 6 and May 8, 2019. On September 30, 2019, Human Rights Watch sent a summary of our findings to the banks requesting information on the steps taken to address the human rights issues documented in this report, to which they replied on October 22, 2019.

Between May and June 2019, we also requested information from the government agencies in charge of supervising the development banks: the Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau (KfW) in Germany, the Department for International Development (DFID) in the UK, the Ministry for Development Cooperation in Belgium, and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in the Netherlands. The four agencies responded between June 7 and 25, 2019.

Responses from the banks and the company are incorporated throughout the report. All letters sent and received by Human Rights Watch are available online as an Annex to this report at: https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/supporting_resources/drc_report_annex.pdf.

Human Rights Watch reviewed extensive documentation for this report, including internal policies and training manuals produced by Feronia and PHC, official written complaints submitted through the PHC grievance mechanisms by workers and villagers residing on their concessions, social environmental impact reports for PHC three plantations submitted to the Congolese Agency for the Environment (ACE), 2018 tax payments made by PHC, public statements by Feronia assessing their own performance, and publicly available internal policies and statements of the four development banks that have invested in Feronia. We also reviewed documentation provided by workers regarding their wages, benefits, and training.

Human Rights Watch consulted a total of six experts on water quality, occupational health, public health, and indigenous peoples in Congo, in addition to 11 NGO representatives with expertise on forest conservation in Congo. We also reviewed secondary sources, including academic studies and media reports.

I. Workers Exposed to Toxic Pesticides

“Each day, [our] bodies are victims of these products.”

Worker, 29, father of four, Yaligimba, January 2019

More than 200 workers are mixing and spraying toxic chemicals on PHC plantations with inadequate and incomplete protective equipment. Many have noticed a deterioration in their health since they started on the job.

PHC uses nine pesticides across its three plantations. Pesticides are chemical compounds used in agriculture to kill pests, including insects, rodents, fungi, and unwanted plants (weeds), that damage crops.[1] Half of the active ingredients in the nine pesticides that PHC uses in its plantations are considered hazardous by the World Health Organization (WHO), including some that may cause severe damage to the eyes. Three of the pesticides contain active ingredients that are considered cancer-causing by the WHO or other recognized health authorities. In August 2019, regulators recommended to the European Commission that approval for one of these chemicals be revoked; German authorities said in September they would completely phase out another of these substances by 2023 (see the Annex for a detailed discussion of the use of pesticides on PHC plantations.)

As of May 2019, at least 245 PHC employees were working with pesticides across the three plantations, all male contract workers, according to the company.[2] They are exposed to toxic chemicals in different ways. Six days a week, 217 workers spray pesticides using a 16-liter backpack sprayer, each treating 300 to 600 palm trees per day. Thirteen team leaders supervise them on site; [3] and 15 workers are responsible for mixing these pesticides in their purest form to create the formula their colleagues spray. Every day, the latter mix 200 gallons worth of formula, the equivalent of nearly 800 liters.[4]

The World Health Organization (WHO) and other recognized authorities, including the European Union and the US Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA), have established that pesticides can pose a risk to human health. “By their nature, pesticides are potentially toxic to other organisms, including humans, and need to be used safely,” the WHO has determined.[5]

Given these risks, the WHO has developed standards regarding the appropriate protective equipment for the use of pesticides in agriculture.[6] Similarly, Congolese law requires that the employer provide workers with appropriate protective equipment for their occupation, and to ensure special medical monitoring for workers in hazardous occupations.[7] PHC’s own policies prescribe specific equipment for workers who apply pesticides, and, more broadly, state the company’s institutional commitment to protect the health of their workers.[8] Occupational health is also the subject of several provisions in a collective bargaining agreement PHC reached with six trade unions.[9]

Human Rights Watch interviewed 43 workers PHC employs on specialized pesticide teams. Workers said the equipment they received was not consistent with what the company had told them they would need to protect themselves when applying pesticides. Following interviews with workers, inspecting equipment, reviewing training manuals, and consulting occupational and public health experts, Human Rights Watch research confirmed that the equipment they received was not consistent with WHO standards or Congolese law.

Health Problems Reported by Workers Applying Pesticides

Workers described a wide range of adverse health effects they experienced since they began manipulating pesticides. These effects included both ailments that manifested immediately after spraying pesticides and chronic conditions that developed over time. Some of these effects are consistent with risks posed by the active ingredients in the specific pesticides sprayed by PHC workers, such as skin problems (rashes, pustules, and burns) and eye problems (eye irritation and pain, blurred vision). They described other symptoms including impotence, shortness of breath, headaches, and weight loss, that are consistent with exposure to pesticides in general, as described in scientific literature.

Impotence

Many male workers ages 25 to 46 told Human Rights Watch they had become impotent since they started their job.[10]

- “Sexually, I feel weak. I don’t have the strength to satisfy my wife in bed. It shames me,” said a 32-year-old who had been applying pesticides for two years.[11]

- “They didn’t warn me of sexual weakness, if they’d say it, we’d protest. They told us we need to protect ourselves, but they didn’t tell us what the risks are,” said a 30-year-old worker from Lokutu. [12]

- “For what concerns sexual weakness, it’s a problem for all the members of the pesticide team,” said a worker who has applied pesticides for three and a half years. “There are some among us who won’t tell you about it, but it will be because they are ashamed, but we all have this problem regardless of age.”[13]

- “There is a chronic fatigue, difficulty breathing and what scares us the most, there is sexual weakness,” said a 29-year-old worker who has applied pesticides in Yaligimba for two years. “I’m no longer able to satisfy my wife in bed … and this issue is for everyone in our team.”[14]

- “There is a problem that threatens us all and it’s becoming sexually weak,” said a worker who has been applying pesticides in Yaligimba since April 2016. “At first I thought I was the only one with this problem [impotence] and that I should not talk about it with others, but when I heard others, I opened up about what I had become.”[15]

Skin Problems

A number of workers described skin irritation, itchiness, and blisters immediately after the pesticides came into contact with their skin.[16]

- “The backpack sprayers that we use are not in good condition anymore, they let the product out and it falls on the person,” a worker who has applied pesticides in Yaligimba for two years told Human Rights Watch. “We get pustules [a small elevation of the skin containing pus] that invade the skin.” [17]

- “The product spilled on my back, [I felt] heat, [got] sores all over my body, the irritation lasted three days. I applied palm oil [to heal]. For us who are far away [from the only hospital], there are no products in the health centers,” said a 26-year-old father of six.[18]

- “When the product touches the skin there are these pustules that appear and it hurts a lot,” a 32-year-old worker in Lokutu told Human Rights Watch.[19]

- “Once you get the product on your skin, [you have] irritation, small itchy pustules, burns, [these are among] the effects we have observed,” a 25-year-old worker from Yaligimba told Human Rights Watch.[20]

- “I have skin irritation and pustules appear frequently,” said a 44-year-old father of six from Yaligimba.[21]

Eye Problems

Several workers described pain and irritation in their eyes while applying pesticides. Others said their vision had diminished or become blurred since they started the job. One doctor and five company nurses said that common complaints among workers who apply pesticides relate to eye problems.[22]

- “The product entered my left eye while I was working, I felt pain, until now,” said a 41-year-old father of six, “it’s been around three months, my eyesight is blurry.”[23]

- “I once fell and the product touched my eyes, when there’s too much sun out it hurts, I went to the hospital [and] they gave me eye drops, it helped me but not really,” a 30-year-old worker from Lokutu told Human Rights Watch. “We were recently given goggles, before I worked without them.”[24]

- “I have vision problems,” a 33-year-old father of six in Yaligimba said. “We asked for goggles several times, they told us to wait but we haven’t gotten anything yet.”[25]

- “The wind can get chemicals in your eyes,” a 29-year old father of three from Lokutu said. “Sometimes the product got in my eyes, I felt pain.”[26]

- “With pesticide workers, the products enter their eyes, they are complaining a lot,” said the chief nurse from a health center in Lokutu.[27]

Headaches

Some workers also said they often had headaches, a concern that medical staff echoed.

- “The smell of this product gives you migraines,” a 34-year-old father of four said.[28]

- “They often complain of … headaches,” said the chief nurse of Lokumete hospital. “[It’s] the smell of the chemical products they’re breathing.”[29]

Workers are exposed to multiple pesticides simultaneously, as the formula they spray or mix combines several of these chemicals. Eye and skin irritation are potential side effects that are associated specifically with exposure to several of the active ingredients in the pesticides sprayed by PHC workers. The other symptoms workers described, such as impotence, shortness of breath, elevated heart rate, headaches, weight loss, and chronic fatigue have been associated with acute and chronic exposure to pesticides in general, according to medical studies and an agricultural toxicologist consulted by Human Rights Watch who worked for many years in Southeast Asia studying rural health issues associated with chemical use and crop production.[30]

While Human Rights Watch is not in a position to assert that the health effects reported by workers are the direct result of their exposure to pesticides, scientific literature, recognized health authorities, and experts have established these are chemical compounds that pose a danger to human health and whose manipulation requires special protective equipment – equipment the company has consistently failed to provide to workers.

Inadequate Information and Training Regarding Pesticide Exposure

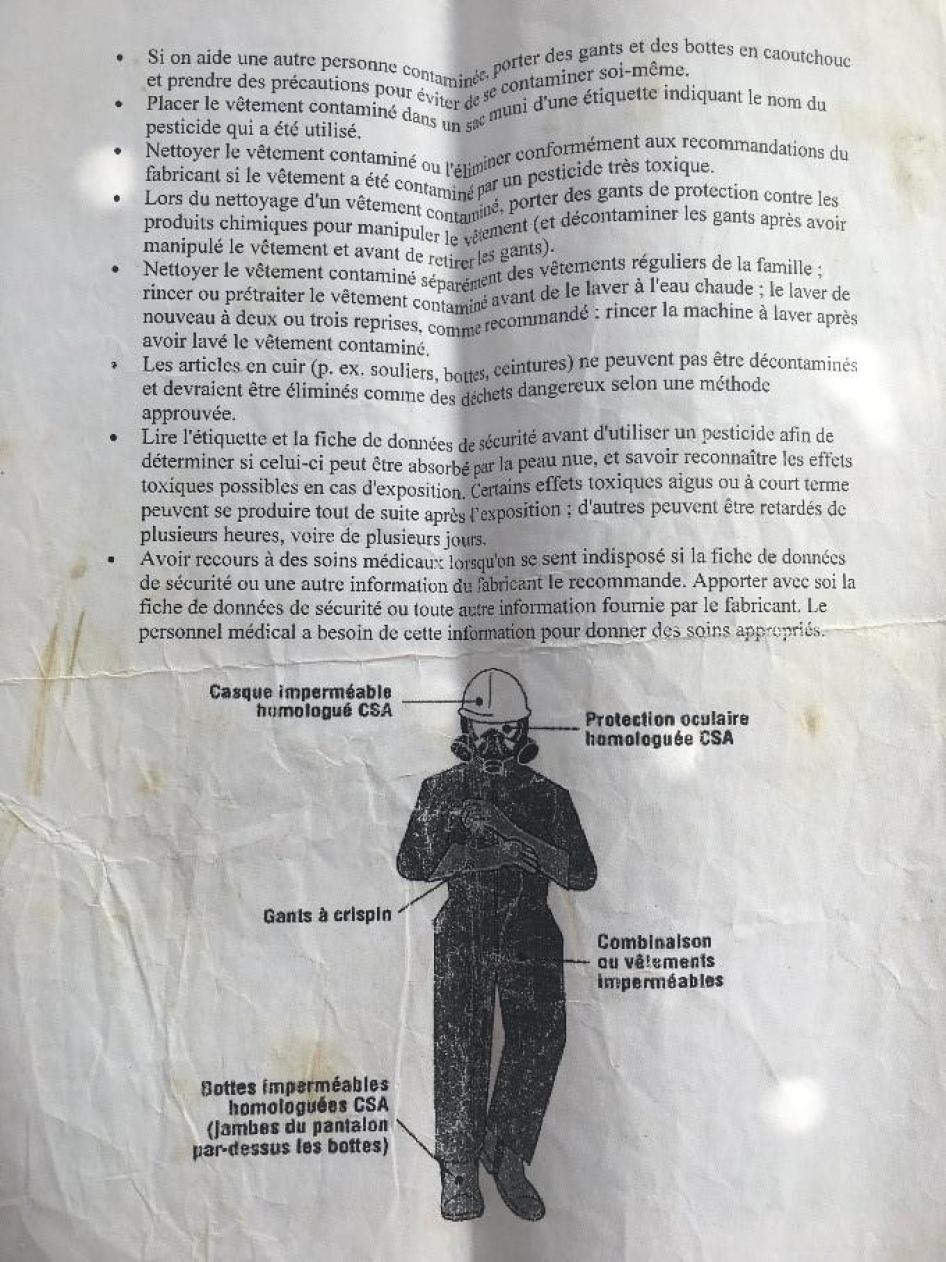

According to the PHC sustainability director, employees who work with pesticides undergo a one-week training in Lingala – the most widely spoken language in the three plantations – prior to beginning their service.[31] The training informs workers about the health and environmental risks associated with the chemicals and the importance of wearing personal protective equipment, he said.[32] Some workers, however, told Human Rights Watch the training was mostly in French with few explanations in Lingala, which could pose accessibility and comprehension barriers.

The trainings were administered by various company executives: plantation managers, environmental managers, and health and safety managers. Health workers – such as doctors and nurses – do not participate. [33] Agricultural managers on each site are responsible for the trainings.[34]

Human Rights Watch obtained copies of training documents PHC distributed to employees who work with pesticides on the Lokutu and Yaligimba plantations.[35] The documents are all in French and describe health risks associated with prolonged pesticide exposure as “increased risk of cancer and tumors,” infertility, obesity, and fetal malformation. Some workers said they were warned of a risk of impotence as a result of prolonged exposure to pesticides, though this was not explicitly mentioned in the manuals Human Rights Watch obtained. The list of risks described in PHC training manuals was not only incomplete, it also failed to explain the distinction between acute and chronic pesticide poisoning.[36]

In response to a Human Rights Watch information request, Feronia shared another training document for workers who apply pesticides that was distributed in Lokutu, the latter mentioned a “risk of contamination” but contained no information about the health risks associated with pesticide exposure.[37] Feronia said that among the objectives of the training is for workers “to understand the risks associated with all hazardous products, including herbicides, fertilizers, and crop-processing products.”[38] While training documents reveal an effort to educate workers about risks to the environment, they teach little or nothing about the risks they are facing themselves.

Inadequate and Incomplete Protective Equipment During Pesticide Application

The WHO lists the following as components of proper personal protective equipment for the use of pesticides in agriculture: protection of the head, eyes, and face; respiratory protection; and protective gloves, clothes, and footwear.[39] These are necessary for workers as pesticides enter the human body when they are inhaled, ingested, or absorbed through the skin.[40] Skin contact is the most common cause of pesticide poisoning for applicators and some pesticides enter the body through the skin quite readily.[41]

The compulsory trainings PHC administers to workers who apply pesticides instruct them that they must wear protective equipment, specifically: helmet, respirator, goggles, gloves, waterproof overalls, and waterproof boots.[42] “We do everything possible to protect them,” the then Yaligimba interim area general manager told Human Rights Watch.[43]

Human Rights Watch asked workers about the type of protective equipment they had received and how it compared to what they had learned in their trainings. Researchers inspected and photographed several protective equipment items in workers’ homes as well as in the company’s warehouses, where they obtained the specifications for some of these items. Lastly, Human Rights Watch followed behind a group of workers spraying pesticides in the Yaligimba plantation and interviewed their manager.

While PHC internal guidelines for protective equipment appear to be in line with WHO standards, Human Rights Watch found that poor implementation of these guidelines results in workers being exposed to toxic pesticides with inadequate and incomplete equipment. This is even the case after workers repeatedly complained to their supervisors about inadequate equipment or equipment the company never distributed despite instructing them it was indispensable. PHC continued to send them to the oil palm fields to apply pesticides, however, without improving or providing the missing gear.

Helmets

None of the workers interviewed received helmets, as mandated by the company’s health and safety guidelines. These helmets are intended to both protect them from pesticide exposure as well as against thorny palm tree branches that can inflict head injuries.[44]

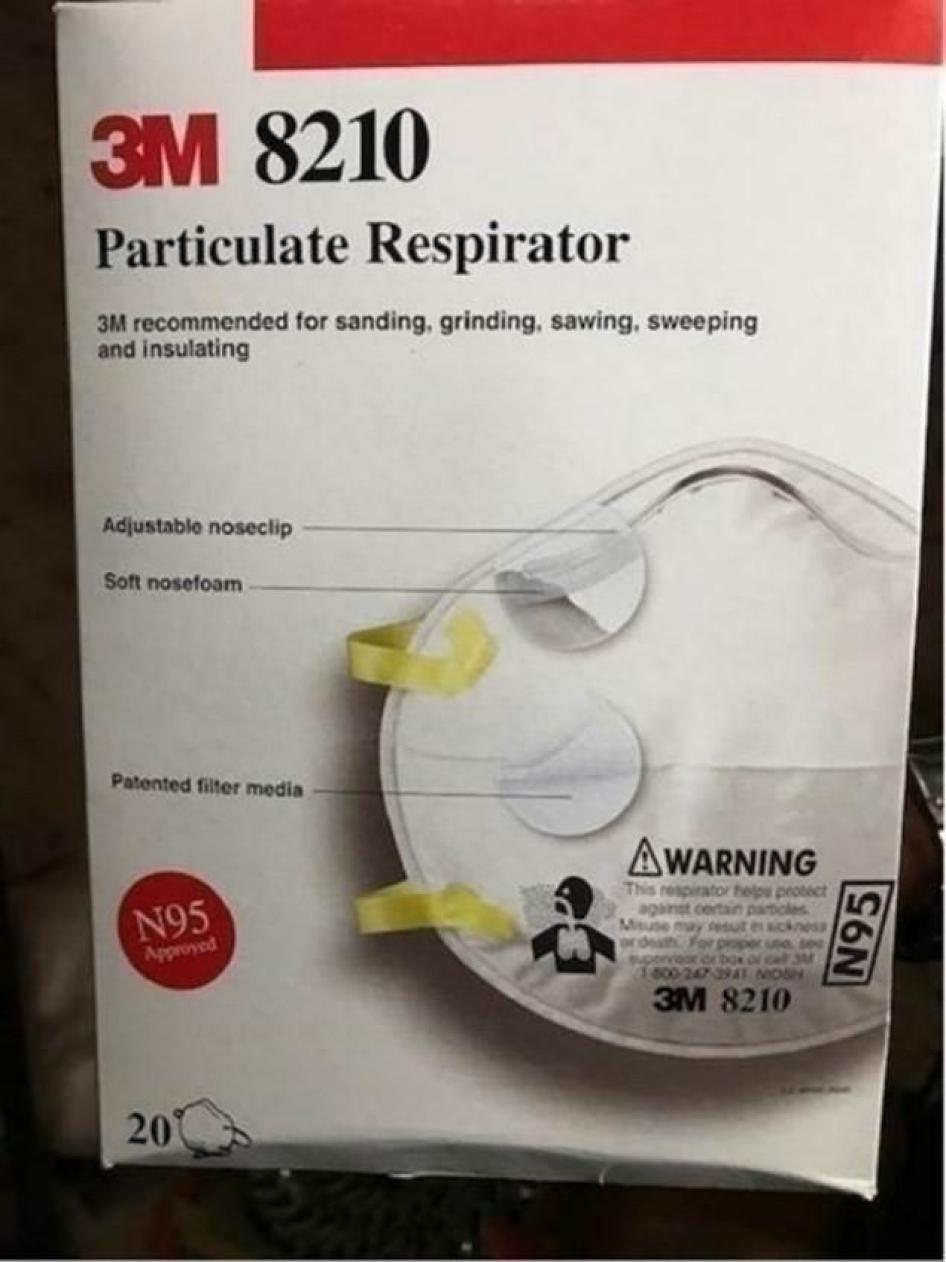

Respirators

Fewer than half the workers said they had received respirators.[45] However, according to the WHO guidelines, agricultural workers using pesticides should have respiratory protection.[46]

In January 2019, a PHC health and safety auditor told Human Rights Watch that workers in Lokutu had been spraying pesticides without respirators for two months.[47] He said he filed a complaint and was told that management had placed an order, but the respirators had not yet arrived.[48] A worker in Lokutu similarly reported he and his team of 14 had already worked without a respirator for three months.[49] Another said it had already been five months for his team.[50]

A former PHC manager who worked in Boteka for three years and oversaw a team of 200 plantation workers said that laborers who applied pesticides only had respirators “sometimes” .[51] The supervisor of the pesticides team in Yaligimba plantation told Human Rights Watch that only workers who mixed pesticides had appropriate respirators. They are five out of a team of 114.[52]

Human Rights Watch obtained the specifications of the respirators that PHC/Feronia distributed to some of the workers who spray pesticides and consulted an agricultural toxicologist who has studied rural health issues associated with chemical use and crop production for many years. The expert’s assessment was that the respirator provided by the company is “designed for the control of dust and other particles, it is not an approved pesticide respirator and not designed to adequately protect workers from exposure.”[53]

Goggles

“Glyphosate generally causes vision problems, we insist on workers wearing their goggles,” said the PHC sustainability director, who oversees the company’s health and safety department.[54] However, only ten of the 43 pesticide applicators and mixers Human Rights Watch interviewed said they had received goggles. Several complained their vision had developed problems since they started the job.[55] “I have never received goggles and I don’t know anyone who has,” a 25-year-old who has been working in Lokutu for two and a half years told Human Rights Watch.[56]

Even workers who had goggles said they had worked for long periods of time, up to 22 months, before ever receiving a pair.[57] A father of six from Lokutu said:

The product, during work, entered my left eye. I felt a pain, until now. It’s been around three months. My vision is blurry. I went to see the [company] doctor [in Lokutu], my medicine doesn’t help me … they didn’t test me, they just gave me medicine. I continued to work every day [after the accident]. If the sun’s up, I don’t see much with my left eye. I wear goggles now. I had asked for them before the incident, but I didn’t get them.[58]

Another worker, who started spraying pesticides in December 2016 in Yaligimba, told Human Rights Watch that he and his team of 25 never received goggles and helmets even though they were instructed these were necessary in a training imparted by the company.[59] A former PHC manager who worked in Boteka for three years and oversaw a team of 200 plantation workers said workers who spray pesticides did not have goggles at this site.[60]

Gloves

Most of the workers told Human Rights Watch they had gloves.[61] However, the gloves distributed by the company were made of a mix of cloth and leather. This material can be more hazardous than no protection at all because they absorb and hold the pesticide close to the skin for long periods of time.[62] A few workers had two types of gloves. Human Rights Watch could not obtain the specifications for the second variety, though in appearance they are made of a thin yellow plastic similar to cleaning gloves for domestic use.

The PHC sustainability director told Human Rights Watch they replaced damaged gloves for workers who spray pesticides, “all they have to do is show them,” he said.[63] However, for the rest of the equipment, they do not replace the items except once every six months.[64]

Overalls

Nearly all the workers Human Rights Workers interviewed said their overalls were made of permeable cotton, even though they had learned they needed waterproof overalls during the training imparted by the company.[65] “These clothes don’t protect the body,” said a 25-year-old worker from Lokutu.[66]

In addition to wearing their overalls while spraying pesticides, workers must sometimes wait to be picked up by company transport on the plantation and then still have to travel a considerable distance to their homes, increasing the exposure time to their contaminated clothing and potentially exposing others in their homes to the pesticides.

“It doesn’t protect us at all,” said a 29-year-old agronomist, who sprays pesticides on the Yaligimba plantation.[67] “We’re accumulating the poison in our body,” another worker said.[68] Many other workers expressed concern that the equipment provided was inferior to the quality prescribed in the training and feared that their health was suffering as a result.

A PHC health and safety auditor told Human Rights Watch that, in the second semester of 2018, management announced they would purchase a sample pair of waterproof overalls for the Yaligimba plantation. The workers “have never had waterproof overalls except for that sample,” he said.[69] Subsequently, Human Rights Watch interviewed the supervisor of the employees who work with pesticides in Yaligimba. He presented the one (and only) waterproof jacket and trousers they had ever received, in May 2018. All workers continue to use cotton overalls, he said.[70]

The PHC sustainability director told Human Rights Watch they provided soap for workers to wash their equipment at their offices while wearing gloves.[71] However, the supervisor of all the employees who work with pesticides on the Yaligimba plantation said that workers did not wash their overalls in their offices because there were no facilities to do so and that the company had not communicated to him any plans to build a laundry room or a dressing room. “The overalls should not go home [with the workers],” he said. “They’re poisoned.”[72]

Workers told Human Rights Watch they handwash their cotton overalls at home several times per week, further exposing themselves to the remains of pesticides in their clothing. Most of them said they washed their overalls barehanded in a bucket of water that they then throw behind their homes. One said the company gave him soap for a month and then stopped, now he just hangs his suit under the sun.[73]

Human Rights Watch also found that there were no facilities for workers to shower or bathe at the end of their shift spraying pesticides, a practice recommended by the WHO to prevent “hazardous contamination.”[74]

Boots

Most workers said they had rubber boots but many complained that the footwear was of poor quality and ripped easily.[75] At the Yaligimba plantation, more than a dozen workers showed Human Rights Watch their torn boots with which they set off for the plantation six days a week. Working with torn boots means their feet are exposed to the chemicals they spray on the ground around the palm trees and in the furrows between palm tree rows.

Inadequate Medical Care and Monitoring

Feronia and PHC executives, managers, and medical professionals said that employees who worked with pesticides had undergone preventive medical examinations twice a year since February 2016 – when they began hiring workers specifically for this task.[76] The protocol is intended to comply with Congolese labor regulations that mandate that workers exposed to “particular risks” are the subject of a “special medical monitoring.” [77]

The PHC sustainability director – who is the direct supervisor of the plantations’ health and safety managers – said workers were “always” informed of the results.[78]

Company doctors told Human Rights Watch these examinations include urine and blood tests in addition to a physical exam.[79] The doctors admitted they face technical limitations to properly assess the health of workers exposed to pesticides. “With the equipment I have I cannot control all the illnesses that could be linked to these chemicals,” said the chief doctor of PHC Pembe Hospital in Yaligimba.[80]

The company doctors in Lokutu and Yaligimba did not know which pesticides the workers applied and complained about limitations in their laboratory equipment.[81] Some medical professionals said they did not have appropriate medicine to treat the conditions displayed by employees who work with pesticides.[82]

None of the workers Human Rights Watch interviewed, including those who started working with pesticides in 2016, had undergone an examination prior to 2017 and very few of them said they had undergone two examinations in one year.

Almost every worker interviewed said they had not received test results after they underwent examination, even after some of them had requested these repeatedly from doctors and supervisors.[83] The chief nurse of a health center in one of the plantations said he was responsible for distributing the results to workers, but the hospital had never sent these to him since he started three years ago.[84]

Not knowing the test results can be devastating for workers, particularly as they are acutely aware of their improper and inadequate protective equipment. “They don’t tell us if we’re poisoned,” a 30-year-old worker who had been spraying pesticides for three years said.[85] “The company sacrifices us for their interests,” said another. “The proof is that the results of our tests are never given to us.” [86] “We think the company found abnormal things in our bodies and to avoid itself any troubles they opted for silence,” said a father of six from Yaligimba.[87]

Some workers said they had complained to their trade union representatives about the company hospital’s failure to disclose the results of their tests, but that their representatives had been ineffective. “We asked the trade union representative to give us results, but no viable reason was given [as to why this hasn’t happened],” said a 33-year-old father of six from Yaligimba.[88] “The trade union does absolutely nothing, they just get our money, they’re afraid of their boss at Feronia,” said a 30-year-old worker who sprays pesticides in Lokutu plantation.[89]

The president of one of the trade unions in Lokutu told Human Rights he “did not think of asking” the doctor why the workers were not getting their results.[90]

After being confronted with extensive personal accounts, the deputy chief doctor of Lokutu PHC Hospital, the largest plantation, vigorously denied having failed to disclose the results, alleging that workers were “certainly” lying.[91]

Workers also reported that doctors dismissed their medical concerns. A 30-year-old worker said that when he attempted to discuss becoming impotent with one of the doctors in Lokutu, the doctor allegedly responded: “The work isn’t good, but it’s better than unemployment.”[92]

II. Dumping Untreated Industrial Waste in Rivers, Communities

“The population [in my grouping] uses water that has dirt from the factory. They’re using it. I discussed it with Feronia but nothing has been done about it yet.”

Dominique Asayo Elenga, Yanzeka grouping customary authority, Boloku, Yaligimba, February 2019

At least two of PHC’s three palm oil mills dump untreated waste in rivers and streams and near the homes of workers, according to Feronia and PHC staff. In one plantation, the foul smell of this putrid waste pervades workers’ homes next to the open channel where it is dumped, and it appears effluents have also contaminated the only drinking water source for hundreds of villagers in a nearby community.

Palm oil mill effluents are the liquid waste that comes from the sterilization and clarification sections of the oil palm milling process.[93] Among the waste generated in palm oil production, palm oil mill effluent (POME) is considered “the most harmful waste for the environment if discharged untreated.”[94] Treatment of POME is considered essential to avoid environmental pollution.[95] This pollution can manifest in the form of contamination of surface waters and a putrid smell, undermining people’s ability to enjoy private, family, and cultural life in their homes, or to consume the water.[96]

The World Bank Group’s Environmental, Health and Safety Guidelines on Vegetable Oil Production and Processing indicate palm oil mill effluents should be treated to bring them into compliance with nine parameters before releasing them into the environment.[97] In its two largest plantations, PHC only controls effluents for one of these nine parameters – the content of palm oil — to avoid dumping their product. This is the case even though PHC’s social environmental impact reports, which were approved by the Congolese Agency for the Environment (ACE) in November 2017, ordered the company to implement effluent treatment systems at both of these sites.[98] When effluents are not treated according to good practice before being dumped in waterways it can have serious consequences for biodiversity and for the health of people who consume water tainted by effluents.

The development banks that invested in Feronia and PHC consider International Finance Corporation (IFC) Performance Standards as their “reference framework,” and the company is bound to work towards compliance; the World Bank Group’s Environmental, Health and Safety Guidelines are considered the technical guidance for implementation of the IFC Performance standards.[99] The guidelines “are achievable under normal operating conditions in appropriately designed, operated, and maintained facilities,” according to the World Bank.[100] However, PHC is not complying with what the World Bank refers to as “good international industry practice,”[101] nor, at a minimum, domestic legislation when disposing of the waste their palm oil mills in Lokutu and Yaligimba produce.[102] The communities of several hundred people who live with this foul waste flowing next to their homes or contaminating their only source of drinking water are bearing the consequences of the company’s actions.

PHC Dumps Untreated Industrial Waste

PHC mills in Lokutu and Yaligimba are dumping tons of essentially untreated effluents on the Congo River and next to communities home to several hundred people, several PHC executives and managers with oversight roles over the factories’ operations and the company’s sustainability policies told Human Rights Watch. Currently, the only measure company representatives consistently reported to be taking at these two PHC mills is to reduce the content of palm oil in the effluents to ensure they are not dumping their product.

According to the World Bank Group’s guidelines, “vegetable oil processing wastewater generated during oil washing and neutralization may have a high content of organic material and, subsequently, a high biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) and chemical oxygen demand (COD),” as well as “high content of suspended solids, organic nitrogen, and oil and fat, and may contain pesticides residues from the treatment of the raw materials.”[103] All of these are factors that contribute to the “contaminant loading,” or the mass of a pollutant that is discharged into a water body during a period of time, such as tons per week. The contaminants in wastewater from vegetable oil processing can have a number of impacts on human health and biodiversity:

- BOD directly affects the amount of dissolved oxygen in rivers and streams.

- High BOD can lead to aquatic organisms, including fish that communities rely on for sustenance, to suffocate and die.[104]

- Excess nitrogen and phosphorus in the water causes algae to grow faster than ecosystems can handle. Large growths of algae, called algal blooms, can severely reduce or eliminate oxygen in the water, leading to illnesses in fish and the death of large numbers of fish. Some algal blooms are harmful to humans because they produce elevated toxins and bacterial growth that can make people sick if they come into contact with polluted water, consume tainted fish or shellfish, or drink contaminated water.[105]

- Too much nitrogen in drinking water, in the form of nitrate, can also be harmful to young infants. Excessive nitrate can result in a person’s bloodstream’s decreased ability to carry vital oxygen around the body. In particular, infants under the age of four months lack the enzyme necessary to correct this condition, which can result in “blue baby syndrome,” an uncommon but serious condition. Infants may show signs of blueness around the mouth, hands, and feet, and may also have trouble breathing, and may suffer from vomiting and diarrhea. In extreme cases, there is marked lethargy, loss of consciousness and seizures, and some cases may be fatal.[106]

PHC does not measure the volume of effluents these two factories release, which in practice means it is also unable to measure the volume of contaminants it releases into water bodies and next to human settlements.[107] The Lokutu chief of technical service, who oversees all the operations in the palm oil mill, provided an estimate nonetheless. “Theoretically,” he said, “for 1,000 tons of palm oil fruits [we’d produce] 40,000 liters of effluents, meaning 40 tons… [and] in average, we process 100 tons of fruits in a day.” According to his own estimate, the Lokutu mill releases 40 tons of untreated effluents in the Congo River every ten days.[108]

The PHC representatives Human Rights Watch interviewed include:

- The PHC director general, Yanick Vernet, who told Human Rights Watch there are mechanisms in place to recover traces of palm oil in the effluents. He added there was a “whole battery of tests done every six hours.” However, other PHC staff Human Rights Watch interviewed and who have firsthand knowledge of the matter contradicted him in regard to the testing, saying they only measured the content of oil in effluents and lacked the laboratory equipment to conduct other testing that is otherwise routine in the palm oil industry.[109]

- The PHC sustainability director, Godefroid Baelenge, who coordinates the company’s sustainability strategy and supervises both environment managers and health and safety managers in every plantation, among other duties. Baelenge has worked at PHC since 1993, including as factory manager, plantation manager and area general manager in Boteka and Lokutu. Baelenge told Human Rights Watch that the Lokutu mill does not treat effluents except for reducing the content of palm oil before dumping them in the Congo River.[110]

- The Lokutu chief of technical service, Paulin Ndedi, who oversees maintenance and production at the Lokutu mill. Ndedi has worked at PHC for 15 years, including as factory manager in Boteka, Lokutu, and Yaligimba. He told Human Rights Watch that they limit the content of palm oil in effluents before releasing them in nature and that this process is the same in every mill. Ndedi also said their methods for assessing the environmental impacts of their effluents was simply seeing whether there were fish in the water and worms in the ground where they dumped them.[111]

- The Yaligimba factory manager, Paul Nzau, who oversees the palm oil mill’s operations said that currently, limiting the content of oil in effluents was the only measure they performed. He said there were other tests they could be conducting but that they lacked the necessary equipment to perform them.[112]

- The Yaligimba environment manager, Édouard Mautu, who oversees the implementation of the company’s sustainability policies and coordinates environmental monitoring, among other duties. Mautu told Human Rights Watch the Yaligimba palm oil mill does not treat effluents before releasing them next to Mindonga settlement. “Personally, I don’t agree with that,” Mautu said.[113]

- The laboratory chiefs in Lokutu and Yaligimba, who perform the tests done regularly on site on the effluents, among other duties. The laboratory chief in Yaligimba, Christian Bafengo, told Human Rights Watch he monitors the content of oil in the effluents every hour, to ensure it remains below one percent. If the content of oil exceeds 1 percent, effluents are sent back to sit in a tank to allow for the palm oil residue to separate from the waste water, so that the oil can be recovered. He said he did not perform any other tests on the effluents and that the situation was similar in Lokutu, where he had previously worked as laboratory chief for 21 months. The laboratory chief in Lokutu, Fiston Bikoli Mongite, said he measures the content of oil in effluents. He said he does not have enough laboratory equipment to perform other tests and that they did not measure the volume of effluents released by the mill.[114]

In Lokutu, the PHC palm oil mill dumps its effluents in the Congo River.[115] In Yaligimba, the mill releases the effluents in a channel next to Mindonga workers’ camp, a settlement directly behind the mill, home to hundreds of people. The stream of waste water continues its course for five kilometers, passing several communities in its way, and finally flowing into a natural pond.[116] An agent of the Congolese Agency for the Environment (ACE) told Human Rights Watch that, while conducting an inspection in Yaligimba in the third trimester of 2016, he had observed that the “effluents are poorly handled, their pipeline dumps them upstream from where the population draws water for their domestic activities.”[117] His agency did not, however, take action to sanction the company or remediate any contaminated water sources.

When Human Rights Watch visited the plantations and factories in early 2019, this remained the case even though PHC’s social environmental impact assessment reports approved by ACE in November 2017 established that the company should implement treatment systems at both of these factories as part of their compliance measures.[118]

Feronia’s CEO, Xavier de Carnière, told Human Rights Watch “the effluents have no environmental impact, on the contrary it has a positive impact.”[119] If correctly treated, effluents can indeed be used as fertilizers on the plantation. However, dumping untreated waste can have serious consequences on the environment and riverine residents’ livelihoods and health.[120]

PHC failure to treat effluents in accordance with good practice are compounded by concerning allegations from officials who claim the company has sometimes fended off regulatory inspections.

The provincial coordinator for the Environment Ministry in Lisala told Human Rights Watch that he and three environmental inspectors sent from Kinshasa attempted to conduct a monitoring mission in Yaligimba on March 2018. A few hours upon arriving to Yaligimba, the inspectors received a call from the environment minister in Kinshasa to withdraw from the plantation “immediately.” “We returned… the same day,” the provincial coordinator said. “Our understanding is that the company appealed to the environment minister to avoid the inspection.… We couldn’t get inside.”[121] During an interview in Kinshasa, the PHC director general told Human Rights Watch he was not aware of this sort of incidents at any of his plantations.[122] Representatives of the Environment Ministry in Kinshasa could not be reached for comment to corroborate the allegations.

Industrial Waste Dumping Next to Residential Areas

In Yaligimba plantation, the PHC palm oil mill dumps its largely untreated effluents in an open channel next to Mindonga settlement. The stream of effluents continues its course for five kilometers, at which point it flows into a natural pond.[123]

Human Rights Watch researchers experienced the effluents’ strong, putrid smell and fumes that pervade the workers’ housing located next to the mill where they live with their families. Though the stench is considerably worse in the section closest to the mill, it carries through the settlements located on each side of the open wastewater channel until it reaches the natural pond. Villagers, mainly women and children, were bathing and washing their clothes and cooking utensils in this pond.

Industrial Waste Contaminates Communities’ Water Sources

Residents from Boloku, a settlement west of the Yaligimba mill with over 100 homes, said they believe Loeka creek, their only source of drinking water, has been contaminated by PHC activities since 2018.[124] After pinpointing GPS coordinates during field research and analyzing satellite imagery, Human Rights Watch found that a channel effectively connects the pond where the Yaligimba mill deposits its effluents to Loeka stream and creek (see Map 4).

“Loeka didn’t use to have problems but recently the water changed, we saw it got dirty, we saw oil mixed with fuel,” said a 42-year-old fisherman who has lived in Boloku since 2003. “I’ve never seen the water change like this.”[125]

One possible explanation why residents said they had not experienced this before is that Yaligimba’s mill quadrupled its production between January and November 2018: Yaligimba produced 507,438 kilograms of palm oil in January and 1,918,975 kilograms in November.[126] Feronia also reported a year-over-year increase in their palm oil production, across its three plantations, of 36 percent between the second quarter of 2018 and the second quarter of 2019.[127] The volume of effluents generated by the mills is proportional to the volume of production.[128]

A 38-year-old resident from Boloku said:

The water had oil, it was mixed with diesel. It was not a small quantity. It was everywhere in the water. We see that the factory water enters our creek. It wasn’t just one time… If they work hard, it’ll return. You can smell the fuel. When it’s there, you need to wait a week until you can use [the water] again. We use the water to cook, for drinking. We also put cassava in the water [to soften it]. We leave the cassava for one day in water. We have 103 houses here. Of them… we all use the water from Loeka. … We don’t have pumps here, there are no sources other than Loeka.[129]

“I discussed it [Loeka creek] with Feronia but nothing has been done about it yet,” Dominique Azayo Elenga, customary authority of the Yanzeka grouping, which includes Boloku, told Human Rights Watch.[130] Human Rights Watch obtained a copy of the official complaint Asayo submitted to the company’s grievance mechanism on November 11, 2018, which corroborates that the PHC administration in Yaligimba has been aware of the residents’ grievances for several months.

“There’s oil from the factory. The color of water changes… Nothing has been done yet,” Asayo said. “People still drink it.… We put [cassava] in this water [to soften it] but it’s getting mixed with this substance.” Azayo said that the Yaligimba PHC environment manager told him that the company had tested the water and found that “the substance isn’t harmful for people so [the company] doesn’t think it’s necessary to compensate.” But Azayo said he was not shown any test results.[131]

Azayo also said that the environmental manager told him the company needed to make modifications to the open channel through which they disposed of the waste, and that he drew up a settlement in response to Azayo’s complaint. The settlement apparently did not offer any compensation for the harm. Azayo said he rejected it.[132]

In February 2019, the PHC director general told Human Rights Watch he was not aware of complaints about contaminated water in the company’s plantations.[133]

III. Abusive Employment Practices and Extreme Poverty Wages

PHC has not adequately provided protective equipment to its workers, while frequently underpaying wages and relying on temporary contracts to withhold benefits in apparent violation of Congolese law.

PHC workers face considerable barriers when seeking redress for abusive company practices. The government agencies responsible for enforcing labor law are drastically under-resourced and understaffed, and because of the remote location of the plantations, PHC workers have little recourse for bringing complaints against the company or reporting harmful practices.[134] Several workers expressed mistrust towards their trade union representatives and Human Rights Watch found that some union leaders were also mid-level managers overseeing hundreds of plantation workers, contrary to freedom of association guarantees enshrined in labor rights conventions in force in Congo.

Many workers also told Human Rights Watch that their wages do not enable them to meet even basic needs. For example, workers in all three plantations reported that their salaries did not make it possible for their families to eat three meals a day. While the majority of Congolese live in poverty, the European development banks have consistently stated that one of their primary objectives when investing in Feronia and PHC was to create decent jobs and promote development. CDC group, for example, said that “improving the conditions and rights of workers” was “at the heart” of their investment, in accordance with their development mandate. The banks’ development mandate, however, is only poorly met if PHC workers are struggling to put food on the table for their families.

Extreme Poverty Wages and Abuse of Short-term Contracts

There’s no life with this salary, the salary just covers the debt.

Plantation contract worker, Lokutu, January 2019

The contract is given according to the will of the chief: there are people who do three months, six months, even three years or more without a contract. It’s become corrupt.

Plantation worker, Boteka, November 2018

Wages

Contract Workers

Contract workers should be paid according to a wage scale agreed between PHC and six trade unions in February 2018, at the conclusion of a collective bargaining agreement that is in force across all the plantations.[135] The agreement protects contract workers only, who were 4,282 of PHC’s nearly 11,000 workers in December 2018, according to figures provided by the company.

Several workers expressed mistrust toward their trade union representatives and said union leaders are ineffective and that they charge a considerable fee. Such mistrust could be explained because some union leaders are also part of management. For example, the president of a trade union in Lokutu is also a manager for PHC and oversees over 200 plantation workers; he told Human Rights Watch that he saw his role as defending workers while at the same time protecting the company. He also said the company paid all expenses for union leaders to travel to Kinshasa to meet with management.[136]

Human Rights Watch was not able to conduct a comprehensive assessment regarding the state of unions operating on PHC plantations. However, workers’ mistrust along with some union leaders being mid-level management raise serious concerns about the independence of these organizations and whether workers’ right to freedom of association and collective bargaining are adequately protected. These risks are compounded by the potential of retaliation for those who do challenge the company. A former manager who oversaw more than 200 plantation workers said that union leaders would not press the company hard for fear of being dismissed, as it would be considered they were “inciting others to revolt.”[137]

This could partly explain the very low wages the trade unions agreed to in the 2018 collective bargaining agreement. The wages for many contract workers would place them under the World Bank’s extreme poverty line, which is defined as living with less than US$1.90 per day.[138]

The three lowest categories in the wage scale for contract workers are the least skilled workers, corresponding to many plantation laborers. Workers who cut fruit bunches or weed the area around palm trees, for example, are generally paid according to the lowest categories, receiving between 2,085.42 FC (US$1.27) and 2,773.60 FC (US$1.69) per day. Feronia told Human Rights Watch this rate is complemented by an additional two months’ pay disbursed to contract workers in December, so that the worker in the lowest category will effectively make 2432.99 FC (US$1.50) per day, though still well below the extreme poverty line of US$1.90 per day.

In addition to their daily rate, contract workers have benefits such as a premium per child, paid leave, statutory three percent annual wage increase, and access to health care on company hospitals.[139] However, these benefits vary widely from worker to worker depending on their time served with the company, their category, and family composition.