Summary

Sprawling over nearly half of Brazil’s territory and encompassing nine of its states, the Amazon region is home to over 20 million Brazilians. Since 1985 – when the government began monitoring deforestation in the Amazon – more than half a million square kilometers have been razed. This deforestation typically culminates in fires as the vegetation remaining after valuable trees are removed is set ablaze, often illegally. While fires burn throughout the year in the Amazon to clear land for agriculture, cattle-grazing, or land speculation, they usually peak during the dry season between July and October. These fires produce air pollution that poses a severe health risk. Children, older people, pregnant persons, and people with pre-existing lung or heart diseases are especially vulnerable.

This joint report by the Institute for Health Policy Studies (Instituto de Estudos para Políticas de Saúde, IEPS), Amazon Environmental Research Institute (Instituto de Pesquisa Ambiental da Amazônia, IPAM), and Human Rights Watch assesses the health impact of deforestation-related fires in the Brazilian Amazon in 2019. IPAM conducted an analysis of the year’s deforestation and fire trends based on official data. IEPS conducted a statistical analysis of the health impacts of these trends based on official data on air pollution and hospitalizations for respiratory illness (the statistical study is available here). Human Rights Watch conducted interviews with health officials, health care providers, and other stakeholders in five states in the Brazilian Amazon and reviewed policy documents.

The findings of this report indicate that deforestation-related fires were associated with a significant negative impact on public health in the Amazon region in 2019. This includes 2,195 hospitalizations due to respiratory illness attributable to the fires, according to the statistical analysis conducted by IEPS in partnership with IPAM and Human Rights Watch. Of these, 467 hospitalizations (21 percent) involved infants 0-12 months old, and 1,080 (49 percent) involved people 60 years old and over. The study found that patients spent a total of 6,698 days in the hospital in 2019 as a result of exposure to air pollution from fires.

The full impact of the fires on health extended far beyond these cases. Many people in the Amazon have very limited access to health facilities, so the impact on their health might not be captured by hospitalization data. The available data also excludes private institutions, though a quarter of Brazilians have private insurance and tend to procure services in these establishments. It also does not capture the much larger number of people whose respiratory problems, while serious, did not require hospitalization.

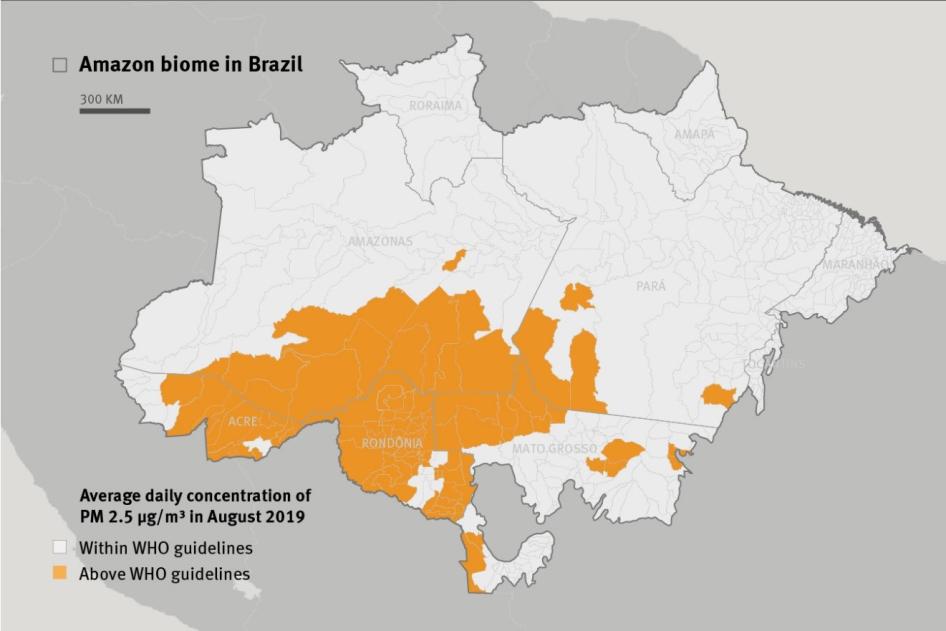

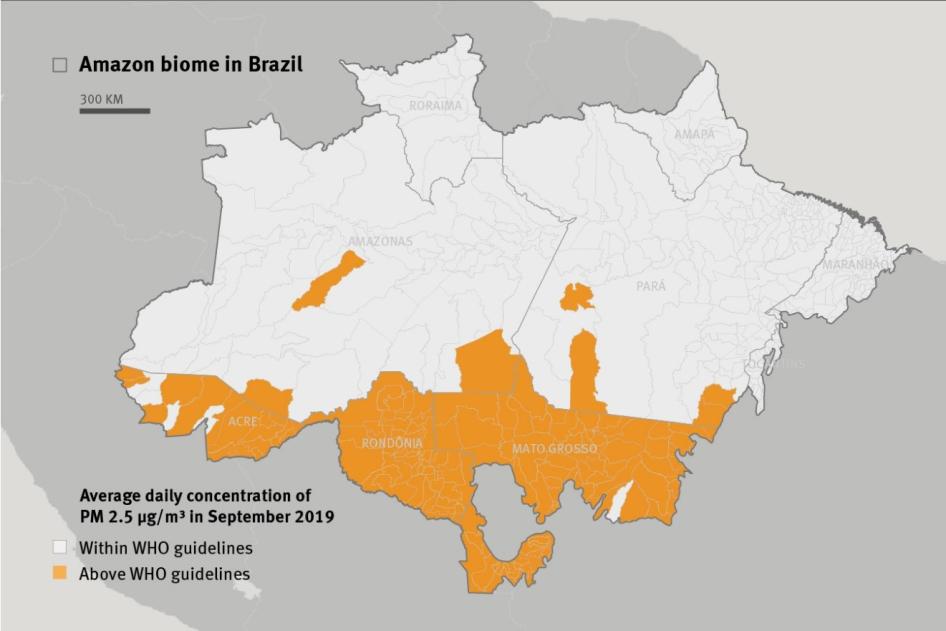

While the lack of reliable health data beyond hospitalizations makes it impossible to precisely estimate the total number of people whose health suffered due to smoke from the fires, official air quality data allows us to at least quantify how many were exposed to the toxic haze. In August 2019, nearly three million people residing in 90 municipalities of the Amazon region were exposed to harmful levels of fine particulate matter – known as PM 2.5 – that exceeded the threshold recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) to protect health. The number increased to 4.5 million people affected in 168 municipalities in September. This pollutant is strongly correlated with the occurrence of fires in the Amazon, and has been linked to respiratory and cardiovascular diseases, as well as premature death.

The public health impact of the fires is felt acutely by Indigenous people in the Amazon. The environmental destruction affects their health as well as their livelihoods. Illegal clear-cutting and subsequent fires often occur in or near indigenous territories, sometimes destroying their crops and depleting stocks of edible and medicinal plants and hunting game.

There are several reasons to anticipate that the 2020 fires in the Amazon could be even more intense than in 2019. Deforestation in the first half of 2020 is up by 25 percent in relation to the same period last year. By April 2020, the newly deforested area, combined with the area cleared but not burned in 2019, already totaled 4,509 square kilometers in the Amazon that could be set ablaze during this dry season – roughly the size of 451,000 soccer fields. (The total area burned in 2019 was 5,500 square kilometers.) June 2020 registered nearly 20 percent more active fire detections than June 2019 and July saw a 28 percent increase in relation to the same period last year. Weather forecasts predict drought in a large proportion of the region, which would exacerbate fires. Environmental officials are struggling with the logistical difficulties of training and deploying firefighting personnel amidst the Covid-19 pandemic.

Moreover, the health impact of fires in 2020 may be worse because of the novel coronavirus. Health officials, medical care providers, and experts fear that medical facilities already strained by the Covid-19 pandemic will struggle to provide care for people affected by fires – potentially causing a collapse of the health system in parts of the Amazon region. People with respiratory illnesses due to the fires may also face the additional risk of contracting the virus when they travel long distances to access complex care, as residents of the Amazon often need to do. In addition, the smoke may aggravate the symptoms of the virus, resulting in more serious cases, and could increase Covid-19-related deaths.

Even if the direst predictions for 2020 do not materialize, the health impacts caused by forest fires will remain a grave problem so long as deforestation continues in its present form.

Brazil should do more to address this chronic and preventable public health crisis, including by taking steps to prevent the fires and mitigate their impact on health, in accordance with Brazil’s international obligations to protect the rights to health and a healthy environment. Authorities should implement an effective air quality monitoring mechanism and enforce air quality standards that protect health through preventive and responsive actions.

Most importantly, the Brazilian government should seek to end the source of the harm by meeting its commitments to reduce deforestation in the Amazon. Under the Paris Agreement on Climate Change, Brazil pledged to end illegal deforestation by 2030. Under its own legally binding National Policy on Climate Change, Brazil committed to reducing deforestation in the Amazon to below 3,925 square kilometers per year by 2020. However, even by the most conservative official estimate, a total of 4,700 square kilometers had already been deforested by the end of July this year. This area not only already far exceeds the limit that Brazil set itself in its climate commitments for the whole of 2020, but it is also larger than the area deforested during the same period in 2019.

The destruction of the Brazilian Amazon has consequences that extend far beyond Brazil. Forests act as natural storage areas for carbon dioxide, a major greenhouse gas driving climate change, by absorbing and storing it over time. The Amazon is an exceptional bulwark against climate change in this regard, storing approximately 100 billion tons of carbon – an amount equivalent to ten years of global greenhouse gas emissions – and removing about 600 million tons per year from the atmosphere. But deforestation and fires have the opposite effect: as a forest is felled and burned it releases vast amounts of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.

Since taking office in January 2019, the administration of President Jair Bolsonaro has undermined Brazil’s capacity to meet its commitments to end illegal deforestation and reduce deforestation overall. His administration has weakened the country’s civilian environmental agencies, resulting in a dramatic decrease in the enforcement of laws that protect the rainforest.

In response to mounting criticism at home and abroad, the administration has repeatedly deployed the armed forces to contain fire activity in the Amazon. While these deployments may have had a deterrent effect in the short run, they have not solved the underlying problem, as evidenced by the continued increase in deforestation and active fire detections during the first half of 2020.

More deforestation means more lands waiting to be burned. Until Brazil effectively curbs deforestation, the fires can be expected to return every year; they will continue to destroy the rainforest and poison the air that millions of Brazilians breathe.

Methodology

This report is a collaboration between the Amazon Environmental Research Institute (IPAM), the Institute for Health Policy Studies (IEPS), and Human Rights Watch.

IEPS conducted a statistical study that estimates the number of excess hospitalizations attributable to deforestation-related fires, IPAM analyzed official government data on deforestation and fires from Brazil’s National Space Research Agency (INPE), and Human Rights Watch conducted interviews and analyzed relevant government health and environmental policies from a human rights perspective.

The statistical study estimates the health impact of air pollution from deforestation-related fires in the Brazilian Amazon Biome in 2019. (The Biome comprises the geographical area over which the rainforest extends, sprawling over nine of Brazil’s states: Acre, Amapá, Amazonas, Pará, Rondônia, Roraima and parts of Maranhão, Mato Grosso, and Tocantins.) The study entailed the construction of a statistical model relying on official government data on hospitalizations due to respiratory illness and on fires, deforestation, and air pollution. It relied on measurements of particulate matter smaller than 2.5 micrometers in diameter (PM 2.5) as an indication of air pollution; PM 2.5 levels in the Amazon region are strongly correlated with the occurrence of fires and the serious health consequences of this contaminant are well established in public health literature. The statistical analysis controlled for three weather variables (mean temperature, rainfall, and humidity) and municipality trends (which account for specific trends that might be related to public policies developed at the municipal level) that could also affect respiratory health, to attempt to isolate the impact of air pollution associated with deforestation-related fires. The statistical study along with its full methodology is available here.

The study on deforestation and fires included an analysis of monthly active fire hotspots and deforested areas by municipality for the years 2016 through 2019. The details of the description and treatment of the data are available at: Alencar, A., Moutinho, P., Arruda, V., e Silvério, D., “The Amazon in Flames: Fire and Deforestation in 2019 – And What’s To Come in 2020,” Technical Note n° 3 IPAM, April 2020. The methodology and data used for the estimation of the area deforested and not burned in 2019 and 2020 is available at: Moutinho, P., Alencar, A., Arruda, V., Castro, I., e Artaxo, P., “The Amazon in Flames: Deforestation and Fire During the Covid-19 Pandemic,” Technical Note n° 4, IPAM, June 2020.

The source for data on deforestation and active fire hotspots is the National Institute for Space Research (INPE); data on air pollution was obtained from the System of Environmental Information Related to Health (SISAM), a database created by INPE, and the Health Ministry and the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), among others; and the source for hospitalizations is Brazil’s Unified Health System (SUS) informatics department, DATASUS. (The full study with a detailed explanation of the methodology can be accessed here.)

This report’s findings are also based on interviews with 67 people, including health officials at the federal, state, and municipal level; federal and state prosecutors; medical care providers; members of medical associations; academics with expertise on health, environment, and climate; representatives from civil society organizations; and Indigenous leaders of communities impacted by smoke from deforestation-related fires.

Human Rights Watch did not conduct in-person interviews for this report given travel restrictions and our duty of care to prevent the propagation of Covid-19. The interviews were conducted by telephone or secure online platforms between January and July 2020. Most interviews were conducted in Portuguese. Given these limitations, we were able to conduct a limited number of interviews with ordinary Brazilians impacted by the health effects of smoke from deforestation-related fires.

In June 2020, Human Rights Watch sent information requests to federal and state authorities. At the federal level, Human Rights Watch contacted the Environment Ministry and the Brazilian Institute of the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA). At the state level, information requests were sent to the state health secretaries from Amazonas, Mato Grosso, Pará, and Rondônia, given that over 8o percent of the fires throughout the Amazon Biome in 2019 were concentrated in these four of the nine states that make up the Amazon region, according to official government data from Brazil’s National Space Research Agency. As of August 3, 2020, the states of Pará and Rondônia as well as the Environment Ministry and IBAMA had responded.

We informed all participants of the purpose of the interview and how the information gathered from the interview would be used. They consented orally. No interviewee received compensation for providing information.

I. Deforestation, Fires, and Climate Change

Deforestation

Since 1985 – when Brazil began monitoring deforestation in the Amazon – more than half a million square kilometers of rainforest have been razed for the purpose of settling land, extracting timber, creating grazing pastures and farmland, and clearing land for mining operations, among others.[1] Between 2004 and 2012, Brazil successfully reduced the rate of deforestation in the Amazon by 83 percent.[2] Among the measures that led to this success were the effective enforcement of national environment laws, the creation of large conservation areas, the introduction of regulations in soy and beef supply chains, restrictions on access to credit for rural producers who lacked legal title to the land or did not comply with environmental regulations, and the use of real-time satellite imagery to locate illegal logging.[3] But after 2012, following a series of policy missteps and budget cuts to enforcement agencies, the deforestation rate began to climb again.[4]

A dramatic increase came in 2019, during President Jair Bolsonaro’s first year in office, when the deforestation rate rose by 85 percent, according to the real-time deforestation alert system DETER issued by Brazil’s Space Research Agency (INPE).[5] Between January and December 2019, a total of 9,174 square kilometers were deforested, in comparison to 4,951 during the same period in 2018.[6] The clearing of the rainforest has continued pace in 2020, with 4,730 square kilometers already deforested in the Amazon between January and July 2020, in comparison to 4,701 deforested between January and July 2019.[7]

Fires

Fires do not occur naturally in the wet ecosystem of the Amazon basin. Rather, they are started by people completing the process of deforestation where the trees of value have already been removed, often illegally. Fire can also spread from areas recently deforested and old pasture fields that are set ablaze into forested areas. Wildfires, prompted by natural ignition like lightning, are extremely rare in the rainforest and are estimated to happen only every 500 years or more.[8]

People set fires throughout the year in the Brazilian Amazon to clear land for crops, cattle-grazing, and land speculation, among others. They usually wait for the dry season between July and October to burn the majority of dead vegetation, with fire activity often peaking in September.[9] There are three key variables that can amplify the extent and intensity of fires in the Amazon region:

- Sources of ignition: fires are overwhelmingly intentionally set by people, with illegal fire activity enabled by ineffective environmental enforcement.

- Fuel material: dead vegetation from deforestation left to dry on the forest floor provides fuel for fires, with increased illegal deforestation also enabled by ineffective environmental enforcement.

- Climatic conditions: unusually hot and dry weather in the rainforest can enable fires to rapidly spread, amplifying their destructive potential during drought years.[10]

Figure 1. The "Amazonian Fire Triangle"[11]

However, 2019 was not an unusually hot or dry year for the Amazon, which rules out climatic conditions as a driver of fire in the region that year.[12]

Fire in 2019 was fueled by the dramatic increase in deforestation brought about, in part, by the failure of authorities to enforce their own environmental laws that would have prevented illegal clearing of the rainforest and curbed the use of fire in these newly deforested areas. Fire activity declined in September 2019, after the federal government issued two fire control decrees in late August and deployed the army for environmental enforcement.[13] Fires continued to decline through the end of the year, facilitated by seasonal rains in following months, but the deforested areas continued to grow. Nonetheless, by the end of the year, 55 percent of the area cleared in 2019 had been burned, the equivalent of over 5,500 square kilometers of the Brazilian Amazon.[14]

During the first half of 2020, deforestation rates continued to climb relative to 2019. By April 2020, the newly deforested area, combined with the 45 percent of the area cleared but not burned in 2019, already totaled 4,509 square kilometers in the Amazon that could be burned during this year’s dry season.[15]

Fire activity has increased in the months leading up to the 2020 dry season. June 2020 alone registered nearly 20 percent more active fire hotspots in relation to June 2019, while July 2020 saw a 28 percent increase over July 2019.[16] A recent analysis by IPAM shows that most states with high rates of deforestation (Pará, Mato Grosso, Amazonas, and Rondônia) had even more fires in the first semester of 2020 compared to the same period in 2019.[17]

Given the unusually large accumulation of cleared-but-unburned land resulting from the dramatic increase in deforestation and the already intense fire activity registered in the region in the run up to the drier months, scientists have expressed concern that the 2020 fires will be significantly worse than 2019’s. “If deforestation is not stopped immediately,” scientists affiliated with Brazilian government institutions wrote in May, “there will undoubtedly be an increase in fires, with or without a drier climate.”[18]

An early July analysis by scientists from the United States’ National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and the University of California suggests, however, that weather will also play an amplifying factor this year, along with the logistical difficulties of fighting fires posed by the pandemic. “You have a perfect storm: drought, the recent increase in deforestation, and new difficulties for firefighting,” said Doug Morton, chief of the Biospheric Sciences Laboratory at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center and co-creator of the agency’s Amazon fire season forecast.[19]

Figure 2. Deforestation and Active Fire Hotspots in the Brazilian Amazon Biome, 2019[20]

Source: Official government data from Brazil’s Space Research Agency (INPE).

Environmental officials in the Amazon echo Morton’s dire forecast. “The hope was we’d reduce the fires [in relation to 2019], but this year will be frightful,” Coronel Paulo André da Silva Barroso, executive secretary of Mato Grosso state’s fire committee told Human Rights Watch in June. The committee presided by Barroso is an inter-agency coordination body that brings together state and federal institutions to fight fires every year. Barroso told Human Rights Watch that the precautionary measures required to contain the Covid-19 pandemic had hindered their usual prevention and preparation activities, including training of firefighters in the field. “The challenge is enormous,” Barroso added.[21]

Climate Change

Under the Paris Agreement on Climate Change, Brazil pledged to end illegal deforestation by 2030.[22] Under its own legally binding National Policy on Climate Change, Brazil committed to reducing deforestation in the Amazon to below 3,925 square kilometers per year by 2020.[23] However, even by the most conservative official estimate, this year a total of 4,700 square kilometers had already been deforested by the end of July. This area not only already far exceeds the limit that Brazil set itself in its climate commitments for the whole year of 2020 but is also larger than the area deforested during the same period in 2019. [24]

The destruction of the Brazilian Amazon has consequences that extend far beyond Brazil. Forests act as natural storage areas for carbon dioxide, a major greenhouse gas driving climate change, by absorbing and storing it over time. When a forest burns, it can release hundreds of years’ worth of stored carbon dioxide into the atmosphere in a matter of hours.[25] The Amazon is an exceptional bulwark against climate change in this regard, storing approximately 100 billion tons of carbon – an amount equivalent to ten years of global greenhouse gas emissions, taking 2018 as the reference year – and removing about 600 million tons per year from the atmosphere.[26]

In Brazil, the main source of greenhouse gas emissions is land use change – for example, when forest is razed and the land is repurposed for pasture – which constituted 44 percent of emissions in 2018, the most recent year for which data is available.[27] A consortium of researchers, including IPAM scientists, recently estimated that due to the “full ongoing expansion” of deforestation in the Amazon, it is likely that the country’s emissions will increase in 2020 between 10 and 20 percent in relation to 2018.[28]

Scientists have warned that the government’s failure to curb the trend of accelerated forest loss could cause the Amazon to reach a ‘tipping point’ where it will dry out and degrade into shrubland, releasing massive amounts of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, with catastrophic consequences for the Brazilian economy and global climate change mitigation efforts.[29]

II. Health Impacts of Deforestation-Related Fires in the Brazilian Amazon

Data on the Health Impacts of Forest Fires

Forest fires produce a mixture of toxic pollutants that can linger in the air for weeks. These include carbon monoxide, nitrogen dioxide, black carbon, brown carbon, and ozone precursors, among others. The principal public health threat, however, is particulate matter smaller than 2.5 micrometers in diameter, known as PM 2.5, one of the main components in smoke. When inhaled, PM 2.5 easily penetrates the lung barrier and enters the bloodstream, remaining in the body for months after exposure.[30]

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), exposure to the smoke and ash produced by forest fires can cause:

- eye, nose, throat, and lung irritation;

- decreased lung function, including coughing and wheezing;

- pulmonary inflammation, bronchitis, exacerbations of asthma, and other lung diseases; and

- exacerbation of cardiovascular diseases, such as heart failure. [31]

Children, older people, pregnant persons, and those with pre-existing respiratory diseases or heart disease are more susceptible to health effects associated with forest fires.[32] Young children are particularly vulnerable because their immune and respiratory systems are still developing, while older people may be more vulnerable because their immune and respiratory systems may be compromised.[33]

In the long term, exposure to air pollution has also been linked to chronic disease and premature death. Worldwide, air pollution due to the burning of forests and other vegetation may cause up to 435,000 premature deaths each year.[34]

To illustrate how fire activity influences air quality in the region, we produced air pollution maps of the Brazilian Amazon Biome for August and September 2019, the peak of fire activity last year. The maps show estimates of monthly average PM 2.5 concentrations at the municipality level produced by the System of Environmental Information Related to Health (Sistema de Informações Ambientais Integrado à Saúde, SISAM), based on satellite imagery analysis. SISAM is a database created by INPE in partnership with the Health Ministry and the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), among others.[35]

Figure 3. PM 2.5 Concentrations in the Amazon Biome in August 2019[36]

Figure 4. PM 2.5 Concentrations in the Amazon Biome in September 2019[37]

Hospitalizations Attributable to Deforestation-Related Fires in 2019

IEPS, in partnership with IPAM and Human Rights Watch, conducted a statistical study to estimate the health impact of air pollution from deforestation-related fires in the Brazilian Amazon Biome in 2019.[38] The study entailed the construction of a statistical model relying on official government data on hospitalizations due to respiratory illness and on fires, deforestation, and air pollution.[39]

The study relied on measurements of PM 2.5 as an indication of air pollution, given that PM 2.5 levels in the Amazon region are strongly correlated with the occurrence of fires and that the serious health consequences of this contaminant are well established in public health literature.[40]

The statistical analysis controlled for three weather variables (mean temperature, rainfall, and humidity) and municipality trends (which account for specific trends that might be related to public policies developed at the municipal level) that could also affect respiratory health, to attempt to isolate specifically the impact of air pollution associated with deforestation-related fires.[41]

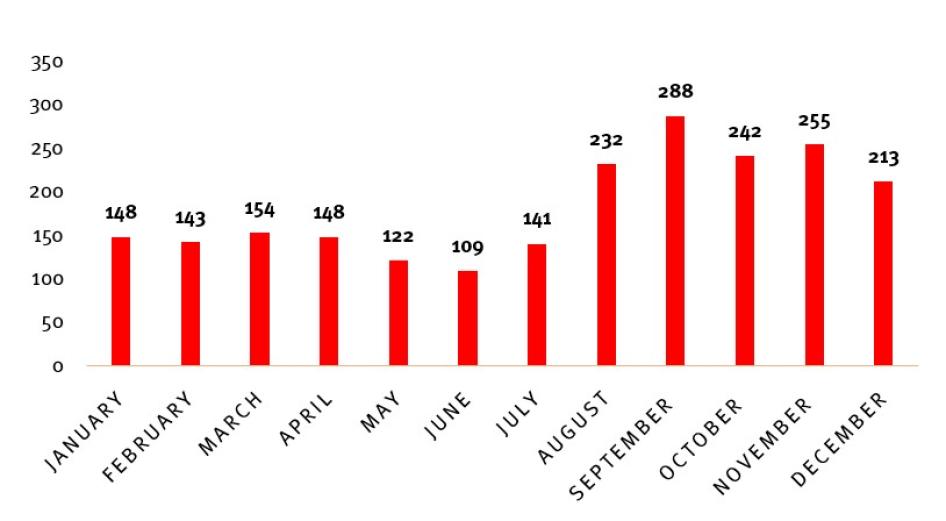

The study estimated that, in 2019, there were 2,195 hospitalizations due to respiratory illness attributable to deforestation-related fires in the Brazilian Amazon. Seventy percent of the hospitalizations involved infants or older people: 467 involved infants 0-12 months old; 1,080 were of people 60 years of age or older. The 2,195 hospitalizations resulted in a total of 6,698 days in hospital for patients.[42]

Hospitalizations attributable to the fires were lower between January and July, months with less fire activity in the Amazon, ranging between 100 and 150 per month. As fire activity intensified in the second half of the year, hospitalizations attributable to the smoke from the fires increased 65 percent between July and August, ranging between 230 and 290 per month through the end of the year. Hospitalizations remained high after October and through the end of the year, possibly due to the continued presence of pollutants in the air, as well as in the lungs and bloodstreams of people who had previously inhaled the smoke.

Figure 5. Hospitalizations Due to Respiratory Illness Attributable to Deforestation-Related Fires in the Brazilian Amazon Biome, 2019

These hospitalizations represent only a portion of the overall health impact of deforestation-related fires in the Amazon in 2019. The total number of hospitalizations resulting from the fires may be higher, given that the data used in the study include only those reported by establishments that receive funding from Brazil’s universal health system (SUS). The data does not include hospitalizations in private institutions not funded by the SUS, where patients might also have sought care due to respiratory illnesses associated with smoke from the fires. Twenty-four percent of Brazilians have private insurance and tend to procure private health services.[43]

It is also likely that a significant number of people whose health condition might have warranted hospitalization never sought, or were unable to reach, care in medical facilities. The health infrastructure in the Amazon region is highly concentrated in a few large cities. Many residents of rural communities and small towns must travel long distances to reach medical facilities that provide complex care, including hospitalizations.[44] On average, accessing such facilities requires people to travel between 370 and 471 kilometers in the Amazon states of Amazonas, Mato Grosso, and Roraima, according to a recent study by Brazil’s Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE). (The national average is 155 kilometers.) [45]

For some, the trip between their homes and the nearest hospital may require travel by river or dirt roads that can take days. These distances deter people affected by deforestation-related fires from seeking needed medical assistance, according to both public health experts and health officials Human Rights Watch interviewed in the Amazon region.[46]

Indigenous peoples’ access to health care is sometimes even more restricted than the already poor averages for the Amazon region. In ten percent of Indigenous villages in the Amazon region, people must travel between 700 and 1,079 kilometers to reach a hospital and get assigned a bed in an intensive care unit, according to a study that cross-referenced data from the Health Ministry and the locations of villages recorded by the government’s indigenous agency.[47]

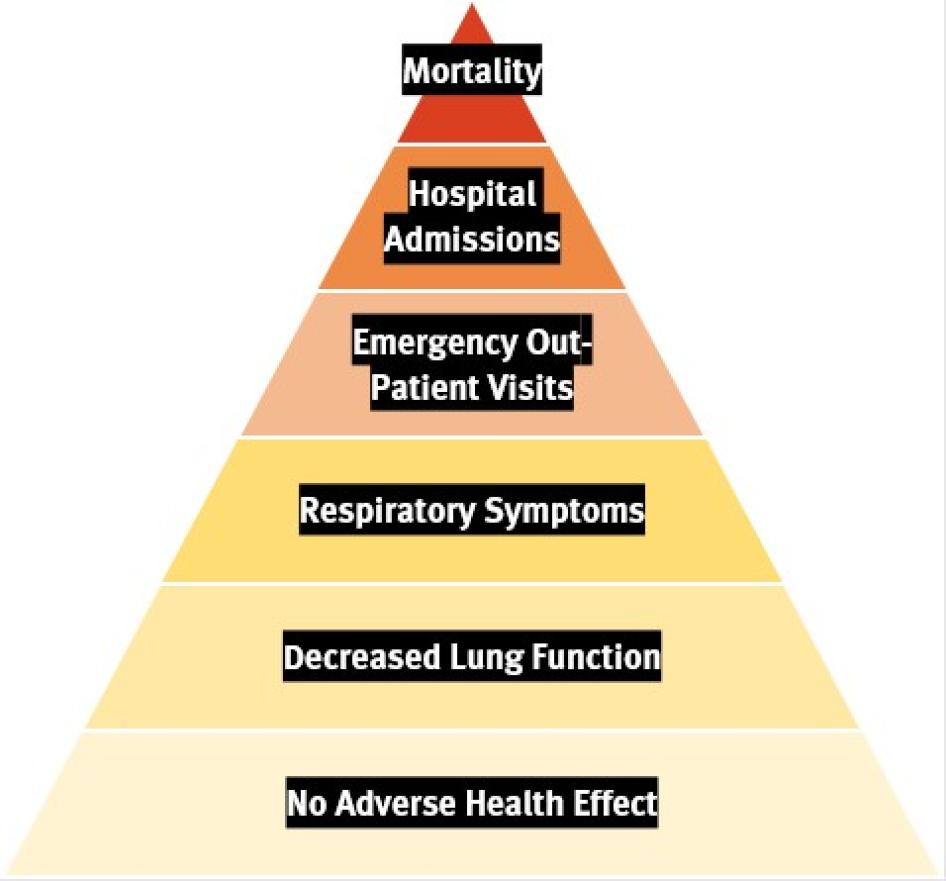

Furthermore, for every case that resulted in hospitalization there are likely to have been significantly more cases involving people whose health was seriously affected but did not require hospitalization. Due to a lack of reliable official data on out-patient medical care in Brazil, the study examined only hospitalizations.[48] According to the WHO, the health effects of forest fires will result in hospitalizations of a relatively small portion of the people whose health is adversely affected.[49] The WHO chart below illustrates the typical distribution of health impacts caused by forest fires:

Figure 6. Health Effects of Smoke from Biomass Burning according to the WHO[50]

Lastly, the study only analyzed short-term health effects of the fires, restricted to the Amazon Biome, where the fires took place. Other long-term studies that assess the health impact of deforestation-related fires in the Brazilian Amazon have concluded that air quality is negatively affected throughout South America, resulting in thousands of premature deaths.[51]

Testimony on the Health Impacts of Deforestation-Related Fires

In partnership with IPAM and IEPS, Human Rights Watch conducted a total of 67 interviews, 53 of which were with health officials at the federal, state, and municipal level; medical care providers; members of medical associations; academics with expertise on health, environment, and climate; representatives from civil society organizations; and Indigenous leaders from communities impacted by smoke from deforestation-related fires.

Most of the interviewees lived and worked in the Amazon region states of Acre, Amazonas, Mato Grosso, Pará, and Rondônia.[52] These states had the worst air quality in the Amazon region during the months of peak fire activity in 2019, with dozens of municipalities registering two-to five times the maximum PM 2.5 value set by WHO guidelines to protect health.[53]

The accounts of those Human Rights Watch interviewed supported the findings of our statistical study that people in the Amazon region suffer from respiratory illnesses during the months of intense fire activity, with children and older people disproportionately impacted. They also affirmed our understanding that hospitalizations represent only a small portion of the health impacts associated with the fires.

Interviewees described how people suffering from respiratory illness are unable to access proper medical care given the limited health infrastructure in the Amazon region. They also expressed concern that the health effects associated with the fires this year could gravely compound the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic and potentially collapse the health system in parts of the Amazon.

Acre

In Rio Branco, the capital of Acre state, a local doctor described the air pollution during the fire season as “unbearable.” He had been practicing medicine in the state for 20 years, and he said that every year the number of hospital visits — especially by children and older people — “increases noticeably” as the fires intensify.[54]

Another doctor, who works at Rio Branco’s Santa Juliana general hospital, said the air pollution had been especially “intense” during the 2019 fire season. “I had to hospitalize lots of patients with chronic diseases, especially chronically obstructive pulmonary disease and heart failure,” which he attributed to the impact of pollution from the fires. After treating patients for a condition that had developed or deteriorated during episodes of critically bad air quality during fire season, he said he advised patients not to leave their homes, but lamented that state authorities did not issue such health warnings to the general population.[55]

In Feijó, a town of 34,000 people 360 kilometers northwest of Rio Branco in central Acre, the municipal health secretary told Human Rights Watch: “Our municipality suffers a lot with the fires in July and August.”[56] Every year during those months there is an increase in the demand of health services due to respiratory problems, he said.

In Sena Madureira, a town of 45,000 people halfway between Feijó and Rio Branco, the municipal health secretary said the health impact of the smoke during fire season put a considerable strain on their medical facilities, which treat patients who travel for as long as three days to seek care.[57] “The health units are at capacity, and as a small municipality we don’t have the infrastructure to treat that many patients with an acute crisis, we don’t have respirators or intensive care units.”

When interviewed in mid-June, the Sena Madureira health official said she feared that this year the situation would be “worse with Covid-19 because the fires aggravate the respiratory symptoms.” She added: “I’m worried about the collapse of the health system.”[58] The official in Feijó expressed the same fear: “We’re very concerned because we’re entering the months when fires increase and, associated with the problem of Covid-19, we could experience a general collapse [of the health system].”[59]

Amazonas

In Lábrea, the southernmost municipality in the state of Amazonas, the municipal health secretary said the smoke from the fires has a dramatic impact on air quality every year. “I suffer greatly myself; I can barely speak, and my throat and eyes dry up,” she said. “The demand in health care increases by 30 percent during the fire season, with a 20 percent increase in the purchase of medicine, equipment, and inhalers.”[60] There is also an “impressive increase” in the number of children and older people requiring ambulatory care due to respiratory problems. While most are treated and sent home, there are many relapses, as they continue to “feel the damaging effects of the fires, the dust, the smoke, the soot [and] they end up returning….[in some cases] once a week.” [61]

In the municipality of Novo Aripuanã, a 20-hour drive from the state capital, Manaus, the municipal health secretary said the increase in patients with respiratory problems during the fire season poses a challenge to the local health system’s limited resources. “We have a very basic hospital, no intensive care unit, and no respirators,” he said. Instead, they must arrange to fly patients to Manaus, or send them by boat, a 12-hour journey.[62]

In 2019, the impact of the forest fires in parts of Amazonas was particularly acute, prompting the state government to declare a state of emergency in the capital, Manaus, and the southern portion of the state.[63] Officials fear that the public health impact could be worse in 2020 due to the Covid-19 pandemic. In Novo Aripuanã, the health secretary said the local health facilities had already reached full capacity long before the fire season due to the pandemic. The president of Amazonas’ state association of municipal health secretaries predicted that the “fires would be a violent aggravator of the pandemic.”[64]

Pará

In Trairão, a municipality in the northwestern portion of Pará state, a community health worker told Human Rights Watch that respiratory problems are a “constant” from July to October due to the many fires in the region. “Doctors prescribe antibiotics, but patients keep returning,” she said, and some need to be transferred to the city of Santarém, a five-hour drive to the north.[65]

In the southern and southeastern portion of the state, where the largest amount of deforestation and fire activity takes place, the smoke during the fire season results in an “overload” of health care facilities, according to the president of Pará’s association of municipal health secretaries, a public official who has served as health secretary in several municipalities in this region. One of the biggest strains on the system, he said, was children requiring “nebulization and rehydration.”[66] The smoke also has a disproportionate impact on older people, he said, and he feared it would be much worse this year due to Covid-19: “With the pandemic, which attacks the lungs, it becomes an explosive combination.”[67]

Rondônia

In August 2019, the Health Secretariat of Rondônia state reported that several municipalities had been “overtaken by the smoke from the fires” and that the resulting “air pollution” was “putting the lives of many at risk.”[68]

One of these municipalities was Cacoal, a town of 80,000 nearly 500 kilometers southeast of the state capital Porto Velho. A family doctor who works in the public health system told Human Rights Watch that the smoke was a problem every year during the fire season. “In the pediatric emergency service and basic health units, there is an increase in the demand for care from Indigenous people, children and older persons,” she said. “For patients who already have a respiratory illness, it becomes exacerbated. A problem that can be controlled with medication is worsened by the environment, and sometimes patients even need to be hospitalized to be treated.”[69]

In Porto Velho, the associate director of a children’s hospital told Human Rights Watch that children with pre-existing diseases like asthma, bronchitis, and rhinitis were most affected by the smoke. “The conditions are graver the younger children are,” he said. “Newborns born prematurely and babies who use respiratory machines are very vulnerable.”[70] The official, a pediatrician with 30 years of experience, said that he and his colleagues were “very concerned” that this year’s fire season was coming as the state was already struggling to handle the Covid-19 pandemic.[71]

These concerns about Covid-19 were echoed by an allergist at Cacoal Regional Hospital. The common symptoms they see among people affected by the smoke during the fire season include coughing, sneezing, and runny noses, he said, which increase the risk that people who have contracted Covid-19 will propagate it. Moreover, the fire season brings high demand for walk-in consults, but these services have been greatly restricted since the start of the pandemic.[72]

Indigenous Peoples

Indigenous people in Brazil feel acutely the impacts of the fire season in the Amazon in more than one way, as it affects both their health and livelihoods. In July 2020, Indigenous territories registered a 76.72 percent increase in active fire detections in relation to the same month last year, according to an analysis of official government data conducted

by Greenpeace.[73]

“For weeks, the smoke covers the sky,” said Dr. Fabio Tozzi, who oversees a project providing health care to 15,000 Indigenous people and traditional communities living on the banks of the Tapajós river in Pará state. “We see people become short of breath, develop allergies, bronchitis and asthma.”[74] Most of the health impacts go unreported,

he said.

Indigenous people in Brazil are especially vulnerable to the health impacts of smoke due to a high prevalence of preventable respiratory diseases.[75] They are, for example, three times more likely to contract tuberculosis in relation to the national average.[76]

“Respiratory diseases are one of the great causes of mortality among Indigenous peoples, particularly among children,” Indigenous health expert, medical doctor, and anthropologist Sofia Mendonça told Human Rights Watch. Mendonça coordinates Project Xingu, a program of the Federal University of Sao Paulo’s medical school that has provided healthcare for 50 years to the Indigenous peoples of Alto Xingu in northern Mato Grosso, and conducts visits to communities to assess the prevalence of chronic diseases, including tuberculosis. “In some communities, you see that children’s lung are deteriorated, they’ve accumulated successive respiratory infections,” she said. [77]

In addition to the health impact of the smoke, in some places the illegal deforestation and burning by people invading their territories threatens their food security – these activities can result in the destruction of the crops, forest products, and hunting game they depend on for their livelihoods, as well as the contamination of water sources by ash.[78] Dr. Tozzi described how the communities he serves in Pará had been “losing their hunting and fishing grounds and their crops” due to the encroachment of fires in their territories and the subsequent introduction of agribusiness on the burned lands.[79]

A medical doctor and anthropologist who has worked extensively with Indigenous peoples in Maranhão told Human Rights Watch: “their quality of life is greatly prejudiced, not only due to respiratory diseases but also [the impact on] food security.”[80] The coordinator of an Indigenous health center in Maranhão recalled the devastation wrought by a fire that burned through the Araribóia Indigenous territory in 2015: “First came the respiratory diseases, because the smoke spread over all the villages…. There were many cases of pneumonia because we breathed smoke day and night, we lost many houses and then, to make matters worse, came the hunger,” due to the loss of crops and game.[81]

Lastly, encroachment on their traditional territories is also often accompanied by violence against Indigenous peoples. A May 2020 report by the Attorney General’s Office that analyzed 390 cases of threats and acts of violence committed during the past decade concluded that conflicts related to the occupation and use of lands and resources, including timber, are the main cause of violence against Indigenous peoples and other at-risk rural communities.[82]

III. Environmental and Health Policies

Environmental Policies

The accelerating destruction of the Brazilian Amazon is driven largely by criminal networks that have the logistical capacity to coordinate the illegal, large-scale exploitation of the rainforest’s natural resources, while deploying armed men to protect their interests. A 2019 report by Human Rights Watch documented how these groups threaten, attack, and even kill people who try to stop them. Their criminal enterprises have benefited from Brazil’s failure to adequately enforce its environment laws and to investigate and prosecute acts of violence against the country’s forest defenders.

Since President Bolsonaro took office in 2019, the state of lawlessness in the Amazon has gotten markedly worse. The 2019 Human Rights Watch report documented how the new administration moved aggressively to weaken the country’s environmental enforcement agency, the Brazilian Institute of the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA), including by removing most of the regional directors who were responsible for anti-logging operations.[83]

The administration also moved to minimize the consequences faced by those caught engaging in illegal logging and other environmental crimes. In 2019, the main federal environmental enforcement agency, IBAMA, issued the fewest fines for environmental crimes in 24 years.[84] In October 2019, the new administration implemented new procedures establishing that environmental fines should be reviewed at “conciliation hearings,” in which a commission can offer discounts or eliminate the fine altogether. The Environment Ministry effectively suspended all deadlines to pay those fines until a “conciliation” hearing could be held.[85] Between October, when the policy came into force, and May 2020, IBAMA issued 5,500 fines for environmental crimes but held only five hearings to enforce them – and perpetrators did not even show up to those.[86]

The administration has sought to weaken restrictions on protected areas of the rainforest where illegal deforestation and fires often occur. The Bolsonaro government proposed laws that would grant property titles to people who occupied these lands illegally and that would open up Indigenous territories for mining and other commercial enterprises.[87] The president has vowed not to designate “one more centimeter” of land as Indigenous territory, despite the federal government’s constitutional obligation to demarcate these protected areas.[88]

These policy moves have been accompanied by expressions of open hostility by the president and his ministers toward those who seek to defend the country’s forests, including environmental enforcement agencies and nongovernmental organizations.[89] At the same time, the administration has repeatedly signaled support for those responsible for the deforestation of the Amazon.[90]

According to federal and local law enforcement, evidence points to the surge in forest fires in August 2019 being the result of an “orchestrated action” prepared in advance by the criminal organizations involved in illegal deforestation.[91] But rather than confront these criminal networks, environment minister Ricardo Salles sought to downplay the problem, claiming initially that dry weather was responsible for the fires.[92] Then the president attacked Brazil’s environmental NGOs, going so far as to accuse them, without evidence, of starting the fires in an effort to embarrass the government.[93] And various officials lashed out at foreign leaders, dismissing international concerns about the damage being wrought to the world’s largest rainforest and one of its most important carbon sinks.[94]

In August 2019, after a growing number of Brazilian business leaders raised concerns that the government’s response to the fires was damaging the country’s international image, the federal government ordered the deployment of army troops throughout the Amazon to stop the burning.[95]

In February 2020, the president issued a decree creating an ‘Amazon Council’ intended to protect the rainforest.[96] The vice-president, a retired army general, presides the Council and has the authority to make all final decisions, sidelining seasoned environmental officials to secondary roles.[97] In May, the federal government ordered the deployment of troops to combat deforestation in the Amazon.[98] Subsequently, in July, the president extended the deployment through November 2020.[99]

In mid-July, the president issued another decree banning fires in Brazil for 120 days, apparently in response to a meeting held between the vice-president and business leaders calling for improved environmental enforcement in the Amazon region.[100]

The current administration has not articulated any plan to address the underlying problem that drives the deforestation and subsequent fires in cleared areas: criminal networks in the Amazon thus operate with near-total impunity, even as they flagrantly violate Brazil’s environmental laws and engage in acts of violence and intimidation against forest defenders who attempt to stop them.

Health Policies

Air Quality Standards and Monitoring

According to the WHO, the cornerstone of government efforts to protect health from air pollution caused by forest fires should be an effective and accurate air quality monitoring program that measures pollutants that are most dangerous to health and that informs the measures authorities take to protect people at risk.[101] The monitoring should be done according to predetermined air quality standards, for which the WHO has provided guidelines.[102]

There are basic steps that authorities can take to mitigate the public health impact of air pollution produced by forest fires, according to the WHO guidelines. When pollution reaches hazardous levels, they could issue public health advisories recommending that people remain indoors, reduce physical activity, and use masks to filter the air they breathe. They might also close or curtail business activities and schools and evacuate at-risk populations to emergency shelters.[103]

While Brazil recently updated its federal air quality standards, it largely lacks an air quality monitoring system. Current federal legislation also does not establish enforceable deadlines for states to implement air quality standards that protect health, which would require them to appropriately regulate and limit the sources of air pollution. State governments are ultimately responsible for controlling and monitoring air pollutants, but without federal deadlines local authorities are under little pressure to implement monitoring systems to prevent harm to health from the toxic haze of forest fires, or to identify episodes of critically poor air quality and protect vulnerable groups accordingly.

Air Quality Monitoring

Three decades ago, the National Environmental Council (CONAMA) — a policymaking body with representation from different government branches, civil society, and the private sector — issued a resolution to create an air quality monitoring system in Brazil.[104] It has yet to be adequately implemented.

Twelve of Brazil’s 27 states have some kind of air quality monitoring mechanism, though none of these are located in the Amazon region, the Environment Ministry told Human Rights Watch in response to an information request.[105] Many of these monitoring stations measure only a small number of pollutants that are harmful to human health, according to a report by a health research organization based on data collected in partnership with the Federal Prosecutor’s Office.[106]

Last year, environment minister Ricardo Salles announced a plan to establish a national air quality monitoring network, with at least one station in each of Brazil’s states.[107] The Environment Ministry told Human Rights Watch it was conducting a bidding process in July 2020 to provide stations to states that do not currently monitor levels of fine particulate matter (PM10 and PM2.5), though this is only one of the several pollutants that pose serious risks to human health and that the WHO has recommended authorities regulate.[108]

Air Quality Standards

In November 2018, CONAMA adopted a resolution that updated Brazil’s air quality standards to align more closely with WHO standards. It did not, however, establish enforceable deadlines by which authorities would have to reduce air pollution to comply with these standards.[109] Because of this omission, civil society representatives and the Health Ministry, which then held a seat in CONAMA, voted against the resolution. [110] The Attorney General’s Office challenged its constitutionality before the Supreme Court on grounds that it offered “insufficient protection for the rights to information, health, and an ecologically sound environment.”[111]

Subsequently, in May 2019, President Bolsonaro and his environment minister Ricardo Salles co-signed a decree that modified the composition of CONAMA, removing the Health Ministry from the body and reducing civil society participation.[112]

In a 2019 report, the Health Ministry acknowledged that assessing the health impact of air pollution was particularly challenging due to poor data on air quality in much of the country.[113] Nearly two decades ago, the ministry developed a Health Surveillance of Populations Exposed to Air Pollution (VIGIAR) program to identify municipalities at risk from poor air quality. Since 2016, however, the program has been largely dormant as it undergoes reform, federal health officials told Human Rights Watch in July.[114] Health Ministry officials described plans to put in place new guidelines to assess health impacts in locations with intense fire activity, as well as training of health officials.[115] These would be positive steps, but would not make up for the absence of an air quality monitoring system, as the ministry itself has previously acknowledged.

Access to Healthcare in the Brazilian Amazon

Access to healthcare in the Brazilian Amazon – particularly complex procedures like hospitalizations or consults with specialists – is highly concentrated in large cities.[116] The uneven distribution of health services restricts access to care for people whose health suffers due to the forest fires and who are unable to travel the distance between their home and the nearest healthcare center. While the national average distance to access complex care is 155 kilometers in Brazil, for some Amazon states it exceeds 400 kilometers.[117]

For rural communities, the uneven distribution of health infrastructure also means that small basic health centers may be the only access to care they have. When patients require specialist care due to exposure to smoke from the fires, doctors might have to request a transfer to state capitals via aircraft or boat, some officials and health care providers told Human Rights Watch. This process may be lengthy, costly, and delay access to necessary care for a patient.[118]

The Toll of Covid-19

As of August 14, Brazil had over 3 million confirmed Covid-19 cases and nearly 106,000 deaths, the second-highest toll for both after the United States.[119] The Amazon region, in the north of the country, has suffered disproportionately: in the northern region, 64.5 percent of hospitalized Covid-19 patients died, against 40.8 percent in the central-southern region, according to a recent study.[120]

Public health officials and medical care providers repeatedly expressed concern that the Amazon region’s limited health infrastructure, already strained by the demands of the Covid-19 pandemic, would struggle to provide care to patients who suffered due to smoke from the fires.[121] People with respiratory illnesses due to the fires may also face the additional risk of contracting the virus as they travel long distances to access complex care, as residents of the Amazon region often need to do.

Covid-19 also makes the effort to reduce forest fires more urgent, given that some of those who are most affected by smoke – older people and people with pre-existing heart and lung diseases – are also groups at high risk if they contract the virus.

Air pollution caused by the fires may lead to more severe symptoms or increased deaths among those with Covid-19, Dr. Aaron Bernstein, interim director of the Center for Climate, Health, and the Global Environment at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, told Human Rights Watch. “There’s evidence that even short term exposure to poor air quality [such as that caused by haze from the fires] could make us vulnerable to respiratory infections,” Dr. Bernstein said.[122] Government authorities in other jurisdictions have banned open burning to protect respiratory health, citing similar concerns.[123]

Given Brazil’s enormous size, experts struggle to predict when the epidemic will “peak,” and estimates vary from state to state.[124] Nonetheless, in late June 2020 the director of the Pan-American Health Organization (PAHO) estimated that the number of deaths due to Covid-19 could peak in August, should the country not improve its response to the pandemic, thus coinciding with the peak of fire activity in the region last year.[125]

The federal government has repeatedly undermined effective responses to the Covid-19 pandemic, including through Bolsonaro’s public statements. “The problem is, Brazil has a president who basically does not believe in science and has downplayed risks from the virus,” Harvard professor and Brazilian public health expert Marcia Castro summed up.[126] The federal government has tried to block states from imposing social distancing rules and to withhold Covid-19 data from the public.[127] The president also fired his health minister in April for defending the WHO recommendations to fight off the virus and pushed his replacement to quit in May.[128] An active-duty general without public health experience was acting health minister at the time of writing.[129]

IV. Brazil’s Human Rights Obligations

Right to Health

Brazil’s constitution obligates the state to guarantee the right to health for all citizens “by means of social and economic policies aimed at reducing the risk of illness and other hazards and at the universal and equal access to actions and services for its promotion, protection and recovery.”[130]

The right to the highest attainable standard of health is also enshrined in multiple international treaties in which Brazil is bound, including the International Covenant on Economic Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR); American Convention on Human Rights and its Additional Protocol in the Area of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights; and the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC).[131] The United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights also highlights that “everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and wellbeing of himself and of his family.”[132]

The right to health goes beyond requiring access to health care and embraces the underlying determinants of health, such as environmental conditions.[133] Access to clean air, for example, is necessary for the enjoyment of the right to health and the right to life.

The UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights – which interprets and monitors compliance with the ICESCR – has stated that governments should adopt measures against environmental health threats, including by implementing policies aimed at eliminating air pollution.[134] States also have an obligation to provide “information concerning the main health problems in the community, including methods of preventing and controlling them,” the Committee has stated.[135]

Brazil is obliged to protect the right to the highest attainable standard of health of Indigenous peoples on a non-discriminatory basis, and has multiple treaty obligations that require it to develop coordinated and systemic action, in consultation with indigenous peoples, to protect their rights, including the right to health.[136]

Right to a Healthy Environment

The Brazilian Constitution recognizes the right to a healthy environment is protected providing that: “All have the right to an ecologically sound environment, which is an asset of common use and essential to a healthy life, and both the Government and the community shall have the duty to defend and preserve it for present and future generations.”[137]

Brazil is also party to international treaties that obligate the state to protect the right to a healthy environment, such as the American Convention on Human Rights and its Additional Protocol in the Area of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.[138] A recent ruling of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights confirmed that the American Convention includes the right to a healthy environment, and highlighted the indivisibility and interdependence between the right to a healthy environment and other rights, including civil and political rights, noting that “[a] clean environment is a fundamental right for the existence of humankind.”[139]

The Court stated that the right to a healthy environment is autonomous and that it protects the elements of the environment, such as forests, rivers, and seas. Therefore, as much as the right to a healthy environment is connected to other rights, its autonomous content means that state failure to enforce its laws, which results in the illegal destruction of forests, can lead to violations of the right to a healthy and sustainable environment.[140]

Most recently, in 2018, the UN special rapporteur on human rights and the environment published a set of Framework Principles on Human Rights and the Environment that laid out states’ basic obligations, including to “establish, maintain and enforce effective legal and institutional frameworks for the enjoyment of a safe, clean, healthy and sustainable environment.”[141]

As a party to ILO Convention No. 169, Brazil has committed, among other measures, to “take measures, in co-operation with [Indigenous Peoples], to protect and preserve the environment of the territories they inhabit”.[142] It has also endorsed the American Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, recognizing that it needs to “establish and implement assistance programs for indigenous peoples for [the] conservation and protection [of the environment and the productive capacity of their lands or territories and resources], without discrimination.”[143]

Human Rights Obligation to Address Climate Change

All governments, as an element of their human rights obligation to respect, protect and fulfil human rights guaranteed under international law, including the rights to life, to health and the right to a healthy environment, have obligations to mitigate anthropogenic climate change.

In 2018, the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights issued a statement on climate change, advising states party to ICESCR, including Brazil, that a failure to prevent foreseeable harm caused by climate change, “or a failure to mobilize the maximum available resources in an effort to do so, could constitute a breach of the obligation [to respect, protect and fulfill all human rights for all].”[144]

The UN Human Rights Committee, which oversees implementation and provides authoritative interpretations of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), to which Brazil is party, has stated that fulfilling the obligation to respect and protect the right to life requires governments to take measures “to preserve the environment and protect it against harm, pollution and climate change caused by public and private actors.”[145]

Brazil joined the Paris Agreement on Climate Change, adopted in 2015 under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, which established concrete commitments and mechanisms for climate mitigation, adaptation and cooperation. The agreement aims to strengthen the global response to climate change “including by holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.” [146]

Pursuant to the Paris Agreement, in 2016 Brazil committed to eradicating illegal deforestation in the Amazon by 2030. Brazil also committed to reaching this goal “with full respect for human rights, in particular rights of vulnerable communities [and] Indigenous populations.”[147]

Recommendations

Brazil should take urgent steps to strengthen environmental enforcement in the Amazon rainforest as part of its human rights obligation to protect the right to health and the right to a healthy environment and to mitigate anthropogenic climate change:

- The federal government should take effective steps to significantly reduce overall deforestation and illegal deforestation in line with Brazil’s commitments under the Paris Agreement on Climate Change and its National Policy on Climate Change as defined in Decrees 7390 (2010) and 9,578 (2018).

- The federal government should ensure that environmental enforcement agents have the autonomy, tools, and resources needed to safely and effectively carry out their mission.

- The federal government should re-establish collaboration between federal agencies and civil society groups working to protect forest defenders, Indigenous rights, and the environment including by maintaining direct channels of communication with communities and individual forest defenders so that they can report illegal deforestation and acts of violence or intimidation.

Brazil should take urgent steps to protect health by developing effective mechanisms that guarantee air quality in line with standards established by the World Health Organization (WHO):

- The federal government should ensure that states implement an adequate air quality monitoring system, pursuant to CONAMA Resolution n.05 (1989), including by providing funding and technical assistance if necessary. The system should monitor all pollutants for which Brazil has adopted guideline values through CONAMA Resolution no. 491 (2018) and communicate results of air quality monitoring to the public in a timely manner.

- The federal government should adopt a comprehensive national action plan to reduce air pollution in line with the intermediary goals and air quality standards defined in CONAMA Resolution no. 491 (2018) and jointly implement and measure progress in collaboration with states. In parallel, CONAMA should adopt a resolution that establishes enforceable deadlines to bring states into compliance with the air quality standards adopted in 2018.

- Environmental and health authorities should cooperate at the state and federal levels to implement plans that foresee preventive and responsive measures to protect health when air pollution breaches air quality standards. Such plans should pay special attention to vulnerable groups and include providing information to the public about the health risks of air pollution and measures they can adopt to protect their health.

- State, federal, and municipal health authorities should collaborate to strengthen the Health Surveillance of Populations Exposed to Air Pollution program (VIGIAR) to effectively monitor the health impacts of exposure to air pollution, including from forest fires, identify municipalities at risk, and inform preventive and responsive measures to protect health. Measures to strengthen VIGIAR could include adequate financial and human resources for the program to carry out its mandate; and operational guidance for the program to identify municipalities at risk.

- The federal government should ensure the continued participation of the Health Ministry and civil society in environmental health policymaking, including by revising Decree 9,806 (2019) and reinstating the Health Ministry’s seat at CONAMA.

Brazil should take urgent steps to ensure accountability for acts of violence related to illegal deforestation and fires in the Amazon, as well as to support and protect its forest defenders:

- The Minister of Justice should convene federal and state law enforcement authorities including prosecutors, police, and environmental agents, to draft and implement a plan of action – with meaningful input from civil society representatives – to address the acts of violence and intimidation against forest defenders and dismantle the criminal networks involved in illegal deforestation and fires in the Amazon region.

- Congress should establish a Congressional Investigative Commission (CPI in Portuguese) to conduct public hearings about the criminal networks responsible for illegal deforestation and acts of violence and intimidation against forest defenders in the Amazon.

Acknowledgments

This report is the outcome of a collaboration between the Amazon Environmental Research Institute (IPAM), the Institute for Health Policy Studies (IEPS), and Human Rights Watch.

André Albuquerque Sant’Anna, visiting professor at the Universidade Federal Fluminense and consultant at IEPS, conducted the statistical study that estimates the number of excess hospitalizations attributable to deforestation-related fires, under the supervision of Rudi Rocha, Research Coordinator. The statistical study and its corresponding methodology are available in full here.

Ane Alencar, director of science at IPAM, analyzed the official government data on deforestation and fires from Brazil’s National Space Research Agency (INPE) and produced the geospatial analysis presented in this report, in partnership with the Human Rights Watch geospatial analysis team.

Luciana Téllez-Chávez, environment and human rights researcher, and Andrea Carvalho, environment and human rights senior research assistant, conducted interviews and performed an analysis of relevant government policies as well as of peer-reviewed scientific research on the health impacts of smoke from biomass burning. Téllez-Chávez and Carvalho wrote the report.

At IPAM, the report was reviewed by André Guimarães, Executive Director; Ane Alencar, Director of Science; and Paulo Moutinho, Senior Researcher. At IEPS, it was reviewed by Miguel Lago, Executive Director.

At Human Rights Watch, the report was reviewed by Daniel Wilkinson, Environment and Human Rights director; Felix Horne, Environment and Human Rights senior researcher; Maria Laura Canineu, Human Rights Watch director in Brazil; César Múñoz, Americas senior researcher; Josh Lyons, Director of Geospatial Analysis; Carolina Jordá Álvarez, Geospatial Analyst; Bryan Root, Senior Quantitative Analyst; Juliana Nnoko-Mewanu, researcher, Women’s Rights Division; Margaret Wurth, senior researcher, Children’s Rights division and Bethany Brown, researcher, Disability Rights Division at Human Rights Watch; and Joseph Amon, health and human rights consultant. Maria McFarland Sánchez-Moreno and Aisling Reidy, senior legal advisors, and Babatunde Olugboji, deputy program director, provided legal and programmatic reviews for Human Rights Watch.

We also wish to thank for their comments Dr. Evangelina Vormittag, president of the Health and Sustainability Institute (ISS), who has worked extensively to protect health by advancing air quality regulations in Brazil, and Dr. Sofia Mendonça, Indigenous health expert, medical doctor, and anthropologist who coordinates Project Xingu, a program of the Federal University of Sao Paulo’s medical school that has provided healthcare for 50 years to the Indigenous peoples of Alto Xingu, in northern Mato Grosso.

The report was prepared for publication by Travis Carr, publications coordinator; Fitzroy Hepkins, administrative manager; and José Martínez, senior administration coordinator at Human Rights Watch. Cara Schulte, associate, Environment and Human Rights division at Human Rights Watch, provided production assistance and support.

We would like to thank colleagues from other non-profit organizations, government and justice officials, researchers, experts, and activists who provided information for this report. We are also deeply grateful to all the courageous health care providers on the frontlines who took time to provide comments for this report amid the Covid-19 pandemic.