Summary

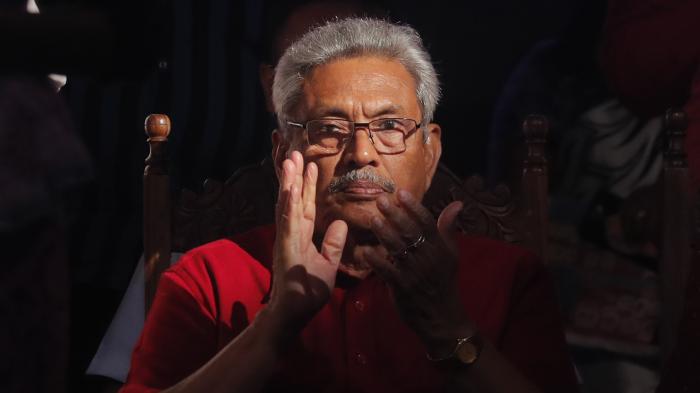

The protection of basic human rights in Sri Lanka is once again at a turning point. Since his election in 2019, President Gotabaya Rajapaksa and his government have waged a campaign of fear and intimidation against human rights activists, journalists, lawyers, and other perceived challengers. The administration has pursued policies hostile to ethnic and religious minorities and repressed those seeking justice for abuses committed during the country’s 26-year civil war that ended in 2009. Fundamental democratic freedoms and fragile post-war reconciliation are in danger.

This report details how the Gotabaya Rajapaksa government is blocking investigations into some emblematic cases of serious violations, documents ongoing repression of minority groups, and highlights the intimidation of activists and family members of victims seeking accountability. The government has withdrawn from a 2015 consensus resolution (known as resolution 30/1) of the United Nations Human Rights Council that sought to ensure justice and end impunity; and has claimed an end to the “era of betraying war heroes” and “allowing foreign forces to interfere in the internal affairs of the country.”

The secessionist insurgency of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) led to serious human rights abuses by both sides and claimed over 100,000 lives. This report finds that, notwithstanding the Sri Lankan government’s claims to be committed to a domestic justice process—despite many that have failed in the past—several police investigations into human rights violations that had made modest progress since 2015 have since been derailed under Rajapaksa’s presidency. On March 26, 2020, President Rajapaksa even pardoned Sgt. Sunil Ratnayake, one of very few members of the Sri Lankan security forces ever convicted of human rights violations. At the same time, several officials facing serious allegations of wartime abuses have been appointed to senior government positions.

Sri Lanka now presents an acute challenge to the United Nations’ commitment to upholding international human rights and humanitarian law in the face of grave crimes. Since the conflict, UN member countries have invested in accountability for serious crimes committed during the conflict and in building rights-respecting institutions. In view of Sri Lanka’s current backsliding and intransigence on impunity, it is crucial that foreign governments, donors, and international institutions now reinforce efforts to promote accountability, starting with a resolution at the Human Rights Council session beginning in February 2021 to maintain scrutiny of Sri Lanka’s human rights situation.

The resolution should seek to establish an independent international mechanism to investigate allegations of war crimes and human rights violations, secure evidence, identify perpetrators, and prosecute those responsible. The UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) should continue to monitor and report on the human rights situation in Sri Lanka and provide recommendations on actions needed to provide justice for victims and accountability for perpetrators.

The UN’s own credibility is at stake. Facing severe criticism for the global body’s failures to intervene and protect civilians in the final phase of the war, then-UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon in June 2010 appointed a three-member panel of experts to advise him, which recommended “a comprehensive review” of actions by the UN system “regarding the implementation of its humanitarian and protection mandates.” That review, which became known as the Petrie Report, laid bare the “systemic failures” of the UN in its engagement on Sri Lanka during the conflict and its aftermath, and is the basis of the policy of Human Rights up Front.

The Human Rights Council in March 2014 called for an independent investigation by the OHCHR. The OHCHR Investigation on Sri Lanka, known as the OISL Report, found horrific wartime abuses committed by both sides to the conflict and concluded that “for accountability to be achieved in Sri Lanka, it will require more than a domestic mechanism.” Following the OISL Report, the Human Rights Council in 2015 passed a landmark consensus resolution that set out a detailed set of steps for Sri Lanka to pursue accountability and reconciliation, as well as security sector reform, to prevent future abuses. Sri Lanka’s compliance with these recommendations will be evaluated by the council in 2021 and will come up short.

To protect Sri Lanka’s beleaguered civil space and marginalized populations, foreign governments and the United Nations should both press the Rajapaksa government to end ongoing abuses and advance efforts to hold accountable those responsible for past atrocities.

***

Soon after taking office, President Rajapaksa began appointing current and former military officers to oversee civilian agencies and by creating “task forces” of military officers with loosely defined remits. The government issued directives putting the Defense Ministry in control of civilian agencies such as the police and amended the constitution to remove important limits on presidential power. Sri Lanka’s already inadequate and flawed investigative and legal institutions have lost any semblance of independence.

The administration has displayed particular hostility to police investigators tasked with identifying and prosecuting those responsible for serious abuses committed under the previous Rajapaksa government from 2005 to 2015. During those years Mahinda Rajapaksa, the current prime minister, was president, and his brother, Gotabaya, the current president, was defense secretary. Thousands of young Tamil men who were suspected LTTE supporters, as well as journalists, activists, and others deemed to be political opponents were abducted, many by armed men operating in white vans, which became a symbol of political terror. Many have never been heard from again.

After Mahinda Rajapaksa was defeated in the 2015 presidential election, a government led by President Maithripala Sirisena and Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe adopted some measures to restore rights, including through the Human Rights Council consensus resolution of 2015. The government worked with OHCHR and invited several UN experts to investigate and make recommendations. It held public consultations on justice and reforms, which were led by civil society activists. It took steps to start addressing enforced disappearances and reparations, with the support of donors and international experts. The generalized fear of the post-war Rajapaksa years largely dissipated.

Gotabaya Rajapaksa has denounced these international and domestic efforts to bring those responsible for the serious human rights violations to justice. Activists and the families of victims that had backed efforts towards the resolution have been threatened by security forces. The government’s claim that it is committed to “achieving accountability …. through the appointment of a domestic Commission of Inquiry” is not plausible. Even as it promised a new inquiry, the government told the Human Rights Council that allegations against senior military officers are “unacceptable” and without “substantive evidence.”

Considering the numerous previous failed commissions under successive Sri Lankan governments, and the government’s own actions since taking office, yet another domestic inquiry is a hollow promise. As Mangala Samaraweera, who as foreign minister in the previous administration had led the negotiations at the Human Rights Council, wrote in the Colombo Telegraph in 2020:

Back-tracking on the [30/1] resolution sends a very clear signal to the people of our country and our partners in the world. The message is that Sri Lanka cares not for reconciliation, accountability, or even democracy. It heralds the dismantling of the institutions that form the bedrock of our nation’s progress, the reversal of trust among communities and countries that was earned through much toil, and the embrace of our basest instincts of hate, insecurity, fear, and envy.

In 2019, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Michelle Bachelet noted that “the risk of new violations increases when impunity for serious crimes continues unchecked.” In 2020, she warned that “the failure to ensure accountability for past violations and to undertake comprehensive security sector reforms to dismantle the structures that facilitated them means that the people of Sri Lanka, from all communities, have no guarantee that violations will not recur.”

Silencing Victim’s Families and Critics

Families of victims campaigning for justice have faced threats from state security forces since Gotabaya Rajapaksa became president. For instance, a member of the advocacy group Mothers of the Disappeared, whose son was forcibly disappeared in 2009, told Human Rights Watch that since the presidential election she has been repeatedly visited by members of the police Criminal Investigation Department (CID):

They have come and asked who is going to meetings. And who is going to Geneva [to attend the UN Human Rights Council]. These are children who were taken by white vans from our houses or who surrendered [to the army]. These are the children we are talking about. I want to know what happened to my son, whether he is dead or alive, and if he is not alive, what happened to him and who did it; whether he was beaten, whether they broke a limb.

Activists, particularly those working in the predominantly Tamil northern and eastern parts of the country on behalf of relatives of the forcibly disappeared, told Human Rights Watch that they had observed a rise in government surveillance and intimidation. As one activist explained, the recent constitutional amendment had vested the president with “total power,” leading to increased fear:

Any activity he does not want to tolerate, he will arrest people. So very little is going on among activists and people are in self-censorship mode. The Mothers of the Disappeared have stopped their protests. They are followed by the intelligence services, even some people’s houses are watched.

Authorities have also visited offices of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). For instance, members of the Terrorism Investigation Department (TID) visited a group in northern Sri Lanka. “It looks like they are keeping tabs really well,” an activist said. “They asked questions from A to Z: school, family.… You can just tell they are trying to wear

you out.”

Intelligence agencies also demand to see financial and administrative records of activist groups, and especially details of funding from donors abroad, leading to fear that authorities will allege accounting errors as a pretext to shut them down or to bring criminal charges. Said one activist: “In the investigation they told us, ‘You have used money you received from abroad for terrorist activities in Sri Lanka. You are involved in terrorist activities, that is why you have been called for investigation.’” Some activists reported that their banks have prevented their organizations from making or receiving transfers.

Despite clear evidence of systematic harassment and intimidation of victims and activists, as described in a report by the UN secretary-general in September 2020, the government of Sri Lanka has denied this behavior in statements to the Human Rights Council.

In January 2021 the government of Sri Lanka drew international condemnation for demolishing a monument at Jaffna University which commemorated Tamil civilian victims of the war. Public Security Minister Sarath Weerasekera called the monument a memorial to “dead terrorists," but protesting students said the action was a “denial of a people's right to memory.”

Conflict-Era Violations and Failure of Accountability

The LTTE over many years committed numerous atrocities, including suicide bombings and other indiscriminate killings of civilians, torture, the use of child soldiers, forced displacement of ethnic populations, targeted killings, and summary executions. Abuses by government forces included arbitrary arrests and detention, extrajudicial killings, rape and other sexual violence, enforced disappearance, torture and other ill-treatment, and indiscriminate attacks on civilians.

In 2009, government forces defeated the LTTE amid widely documented mass atrocities. The 2011 report of a Panel of Experts, appointed by UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, found that “[t]ens of thousands lost their lives from January to May 2009, many of whom died anonymously in the carnage of the final few days,” and that government forces even “systematically shelled hospitals.”

The government also cracked down on civil society, threatening activists, journalists, and lawyers seeking redress for abuses. Security forces detained Tamil men and women on suspicion that they were LTTE supporters and tortured them in custody. There were numerous enforced disappearances and killings.

In the 2015 presidential election, Mahinda Rajapaksa was defeated by a challenger from his own Sri Lanka Freedom Party, Maithripala Sirisena, who had the support of the political opposition, including the United National Party (UNP). The UNP won the parliamentary election, and party leader Ranil Wickramasinghe became prime minister. This government joined the 2015 consensus resolution of the UN Human Rights Council, pledging truth and reconciliation, reparations, and a justice process including Sri Lankan and international investigators, prosecutors, and judges. During its five-year term, the government made slow progress in meeting these commitments, but eventually established an Office on Missing Persons and an Office for Reparations.

Mahinda Rajapaksa formed a new political party called the Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (SLPP), which drew many members of his former party. With his brother Gotabaya as the presidential candidate in 2019, the SLPP campaigned against the prosecution of military officers responsible for war crimes. Gotabaya Rajapaksa became president in

November 2019.

In February 2020, the new government withdrew its support from Human Rights Council resolution 30/1 (and the subsequent resolutions 34/1 and 40/1 extending the mandate), claiming it would instead appoint a domestic commission of inquiry.

Protecting and Reinstating Perpetrators

During his presidential election campaign, and repeatedly since, Gotabaya Rajapaksa has stated his determination to protect “war heroes” from prosecution, saying in November 2019 that a large number “are languishing in prisons over false charges and cases.”

In fact, there have been virtually no successful prosecutions of members of the security forces for human rights violations. Gotabaya Rajapaksa himself faces allegations related to his former role as defense secretary and is named in a civil suit filed in the United States for the killing of journalist Lasantha Wickrematunge in January 2009.

In March 2020, the president pardoned Sgt. Sunil Ratnayake of the Special Operations Unit of the 6th Gajaba Regiment, Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s former unit. The Supreme Court had upheld the conviction of Sergeant Ratnayake in April 2019, ruling that “from the nature of the injuries it can be concluded that the injuries were inflicted with the intention of causing their deaths.” Human rights lawyers have challenged the presidential pardon in the Supreme Court. The petitions are currently scheduled to be heard in February 2021.

Between 2015-19, a number of police investigations into conflict-related human rights violations—which were blocked under the previous Mahinda Rajapaksa government—did begin to make progress, and to reveal evidence of official responsibility for killings and enforced disappearances. Many of those investigations have been derailed since Gotabaya Rajapaksa became president.

In November 2019, immediately after the presidential election, Nishantha Silva, an officer in the police Criminal Investigation Department (CID) investigating several cases described in this report, including the “Navy Case,” the Welikada prison massacre, and the disappearance, killing, and torture of journalists under the previous Rajapaksa administration, fled the country following threats. In July 2020, the former director of the CID, Shani Abeysekara, was arrested for allegedly fabricating evidence against a police officer considered close to Gotabaya Rajapaksa. On August 3, 2020, a police sergeant told a magistrate he was being pressured to give false testimony against Abeysekara. In December 2020, Abeysekara, who contracted Covid-19 in custody, filed a fundamental rights petition in the Supreme Court against his arrest and detention.

In the high profile “Navy Case,” the CID had produced a significant body of evidence and identified 14 suspects in the abduction and disappearance of 10 men and a 17-year-old boy by naval intelligence officers in 2008-9. Among those accused is the former chief of defense staff, Adm. Ravindra Wijegunaratne. The president promoted Commodore D.K.P. Dassanayake, the alleged ringleader, to the rank of rear admiral.

On January 9, 2020, Gotabaya Rajapaksa appointed a three-member presidential commission to look into the supposed “political victimization” of government officials by the previous government. Activists fear that the commission obtained police files related to investigations that have focused on the alleged role of military intelligence and leaked them to the military. In late January 2020, the commission ordered a halt to the trial of naval officers accused in connection with the “Navy Case” abduction and disappearance of the 11 people. The attorney general said the commission had no power to do so. The trial was scheduled to proceed until it was stayed by the Court of Appeal in June 2020.

The Presidential Commission on Political Victimization has also sought to intervene in several other cases, including the abduction and torture of Keith Noyahr, the murder of Lasantha Wikremetunge, and the disappearance of Prageeth Ekneligoda. Several accused testified to the commission that they felt persecuted by investigators, whom they accused of pursuing an agenda against Gotabaya Rajapaksa.

After submitting its report to President Rajapaksa in December 2020, the chairman of the commission, retired Supreme Court judge, Upali Abeyratne, was appointed chair of the Office of Missing Persons (OMP). The OMP was established by the previous government to investigate enforced disappearances. Some victim families said that Abeyratne’s appointment will stall these investigations. As a mother of a disappeared man noted, “Appointing a person who has acted in a way that obstructs the administration of justice to the first seat in an institution related to disappearances, destroys the administration of justice.” Sandhya Ekneligoda, the wife of the disappeared journalist Prageeth Ekneligoda, warned that Abeyratne had “over the last several months, actively colluded with those accused of enforced disappearance, to undermine and threaten the constitutionally guaranteed rights of families of the disappeared to seek legal redress.”

The findings and recommendations of the Presidential Commission on Political Victimization have not yet been revealed.

In November 2020, police in the United Kingdom opened an investigation into the role played by Keenie Meenie Services (KMS). Established by veterans of a British special forces regiment, the SAS, in the 1980s KMS trained an elite paramilitary unit of the Sri Lanka police called the Special Task Force (STF), which is notorious for atrocities. However, the Gotabaya Rajapaksa administration has ignored the new evidence, despite numerous serious allegations against the STF, including the killing of five students in Trincomalee in January 2006, and the Welikada prison attack in November 2012.

On October 22, Sri Lanka’s parliament adopted the 20th amendment to the constitution, which gives the president sweeping powers, including to appoint senior judges, the attorney general, and members of previously independent bodies, such as the human rights commission. A human rights activist in northern Sri Lanka said:

All those [human rights] cases are now being withdrawn or dismissed by the courts…. When you have these 20th amendment powers bringing the attorney general and courts under the president, what else are they going

to do?

On January 13, 2021, the Batticaloa High Court acquitted a pro-government member of parliament, Sivanesathurai Chandrakanthan (alias Pillayan) and four other suspects of the 2005 murder of an opposition parliamentarian Joseph Pararajasingham, after the attorney general decided to drop charges in the case. Chandrakanthan, who was a member of a pro-government armed group at the time of the killing, had been arrested in connection with the case after Mahinda Rajapaksa lost power in 2015. He was elected to parliament in August 2020 and released on bail in November.

Rajapaksa has appointed or promoted several serving and retired military officers who are credibly accused of grave abuses to senior posts in his government. Defense Secretary Kamal Gunaratne was commander of the 53rd division at the end of the war, and Gen. Shavendra Silva, the acting chief of defense staff, was the commander of the 58th division, units facing serious allegations of war crimes. On December 28, 2020, Silva was promoted to four-star general.

Prasanna Alwis, an officer of the police Terrorism Investigation Department (TID) accused of suppressing evidence and shielding suspects in the murder of journalist Lasantha Wickrematunge, was appointed director of the CID on May 21, 2020. C.A. Chandraprema, who wrote an effusive account of Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s role in defeating the LTTE in his book Gota’s War, was appointed Sri Lanka's permanent representative to the UN in Geneva. Chandraprema was years earlier a member of an armed group accused of enforced disappearances and unlawful killings to quell the 1980s Sinhala leftist uprising.

Earlier, on November 22, 2018, police inspector Neomal Rangajeewa, then on bail for the alleged murder of inmates in Welikada prison in 2012, was reinstated to the police during the brief period when President Sirisena installed Mahinda Rajapaksa as prime minister.

In September 2020, Michelle Bachelet, the UN high commissioner, expressed concern over the “appointments to key civilian roles of senior military officials allegedly involved in war crimes and crimes against humanity.” Sri Lanka responded to the Human Rights Council that the “accusations on crimes or crimes against humanity made against these senior military officials are unacceptable.”

Key Recommendations

To the Government of Sri Lanka

- Cease attempts to stifle dissenting voices, including lawyers, journalists, human rights defenders, and the victims of past abuses and their families.

- Implement the recommendations made by UN special rapporteurs and working groups who have visited and reported upon Sri Lanka since 2015, beginning with prosecuting serious crimes of torture, extrajudicial killings and custodial deaths.

- Restore the independence of police investigators and the Attorney General’s Office to pursue criminal investigations against alleged perpetrators of grave abuses. End the harassment of officials who are involved in investigations of alleged human rights abuses.

To Foreign Governments

- Support a resolution at the 46th session of the UN Human Rights Council beginning in February 2021 to advance international accountability for international crimes committed in Sri Lanka. The new resolution should include:

- Continued reporting by the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights;

- A mandate to the OHCHR to collect, preserve, and analyze evidence of serious violations of international law committed in Sri Lanka, to identify perpetrators and prosecute those responsible.

- A mandate for the high commissioner to report to the Human Rights Council on actions needed to advance accountability.

- Impose targeted sanctions on individuals credibly accused of serious human rights abuses and violations of international humanitarian law in Sri Lanka.

Methodology

Human Rights Watch conducted research for this report from January to November 2020.

Field research was conducted in early 2020 in Colombo and in the north and east of Sri Lanka. Following the introduction of travel restrictions due to the Covid-19 pandemic, additional interviews were conducted by telephone throughout the remainder of the research period, alongside extensive desk research and document reviews.

Considering security challenges and the risk of intercepted telecommunications, the inability to conduct in-person interviews has meant that we were unable to include more voices, particularly those of victims of abuses or their families.

Human Rights Watch interviewed 52 members of victims’ families, lawyers, experts and human rights activists. We informed all interviewees of the purpose of the interview, its voluntary nature, and provided no remuneration or other inducement. In most cases we have concealed the identity of interviewees due to security concerns within Sri Lanka.

Interviews were conducted in English, and in Sinhala and Tamil through interpreters.

On January 12, 2021, Human Rights Watch wrote to Attorney General Dappula De Livera asking for the government’s response so that it could be included in this report, but received no reply.

I. Deteriorating Human Rights Situation in Sri Lanka

Since the election of Gotabaya Rajapaksa as president in November 2019, there has been a rapid closing of civic space and freedom of expression in the country. Religious and ethnic minorities are facing discrimination and harassment.

Suppression of Victims and Critics

Perceived opponents of the government, including families of the forcibly disappeared, who had been protesting to know the whereabouts or fate of their missing relatives, human rights activists, journalists, and lawyers are experiencing a marked increase in surveillance, threats, and other forms of intimidation.[1]

Data collated by the Sri Lankan human rights group INFORM show incidents of “repression of dissent” averaging over one a day since the beginning of 2020. Incidents include beatings, arbitrary arrests, surveillance, death threats, and hacking of electronic devices.[2] “It’s a very scary environment to be a dissenter,” an activist from another group said.[3]

Activists, particularly those working in the northern and eastern parts of the country on behalf of relatives of the forcibly disappeared, said that they had observed an increase in intimidation and surveillance. One activist said that prior to a victims’ meeting, “every one of the mothers got at least six telephone calls from different intelligence agencies asking, ‘Where is the meeting?’ ‘Who is organizing the meeting?’ ‘What is being said?’”[4] By November, the pressure was so high, one human rights defender said, “very little is going on among activists, and people are in self-censorship mode.”[5]

A member of the advocacy group Mothers of the Disappeared, whose son was forcibly disappeared in 2009, said that members of the police Criminal Investigation Department (CID) had repeatedly visited her since the presidential election.[6] A person who works with the families of the disappeared said that in the relatively open environment of the previous government many had spoken out about their cases. “Now they [the security forces] know who talked about their crimes, so the victims have fears about their safety,” he said.[7]

Human rights defenders working in different locations around the country also reported such pressure. One activist said: “After the election, military activities including monitoring and inquiries have increased. They are following us. That is a huge threat for human rights groups.”[8] Another said the authorities came to his office demanding information, but then revealed that “they knew already everything. My personal details, they knew it. This is part of the intimidation.”[9]

“They are desperate to find out what [nongovernmental organizations] are doing on the accountability front,” one activist told Human Rights Watch in June.[10] In the period before parliamentary elections, which took place on August 5, several were warned that they were on government “watch lists.” Some went into hiding and others left the country.[11] Among those who fled was Dharisha Bastians, a former editor of the Sunday Observer and contributor to the New York Times. Her telephone records have been publicized and authorities seized her laptop.[12] Others described “rampant self-censorship.”[13]

When one group in northern Sri Lanka opened offices in August 2020 after being closed since March to contain the spread of Covid-19, they were promptly visited by members of the Terrorism Investigation Department (TID). “It looks like they are keeping tabs really well,” said an activist. “They asked questions from A to Z: school, family…. You can just tell they are trying to wear you out.”[14] The intelligence agencies also demanded the financial and administrative records of NGOs, and especially details of funding from donors abroad.

On April 1, the authorities said that anyone “criticizing” the official response to the Covid-19 pandemic would be subject to arrest.[15] Among those detained was Ramzy Razeek, a social media user who espoused religious tolerance.[16] Razeek was held in custody for five months before being released on bail.[17] UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Michelle Bachelet criticized the government for using the pandemic to curtail freedom of expression.[18]

Despite clear evidence of systematic harassment and intimidation of victims and activists, as described in a report by the UN secretary-general in September 2020,[19] the government of Sri Lanka has denied this behavior in statements to the Human Rights Council.[20]

Militarization

The Rajapaksa administration has rapidly expanded the role of the military in the government, including by appointing serving and retired officers to previously civilian leadership roles, and creating special “task forces.”

The “Presidential Task Force to build a Secure Country, Disciplined, Virtuous, and Lawful Society” is composed entirely of military and police officers and has the power to issue instructions to any government official.[21] Rajapaksa appointed a serving military officer, Suresh Salley, as head of the civilian intelligence agency,[22] and a retired general, Kamal Gunaratne, who is implicated as a matter of command responsibility in alleged war crimes and crimes against humanity, as defense secretary.[23] The acting chief of defense staff, Gen. Shavendra Silva, is similarly implicated, and has been banned by the US government from traveling to the United States “due to credible information of his involvement, through command responsibility, in gross violations of human rights, namely extrajudicial killings.”[24] He was promoted to four star general on December 28, 2020.[25]

Over 30 state agencies, including the police and the NGO Secretariat, which regulates civil society groups, have been placed under the Defense Ministry.[26]

The Defense Ministry also led the government’s response to the Covid-19 pandemic. In a little over two months, the authorities arrested over 66,000 people for allegedly violating curfew restrictions. The presence of security forces at checkpoints was particularly severe in the predominantly Tamil Northern Province.[27]

Presidential Commission of Inquiry on “Political Victimization”

On January 9, 2020, President Rajapaksa established a Commission of Inquiry to Investigate Allegations of Political Victimization by the previous government.[28] On February 7, 2020, human rights activists lodged a fundamental rights petition against the commission, arguing that it had been given powers that could impede or prejudice legal proceedings. A first hearing on the petition is scheduled on March 25, 2021.[29]

The commission quickly set about intervening in cases where Rajapaksa allies and associates were facing police investigations or prosecution for alleged corruption or for human rights abuses. In January 2020, it attempted to order the attorney general to halt the forthcoming trial of naval officers accused in the disappearances of 11 men and boys in the “Navy Case.” The attorney general rejected the intervention.[30] The Court of Appeal later suspended the trial.[31]

The commission has intervened in three high-profile cases of attacks against journalists, investigated by the CID and discussed in this report, in which military intelligence officers are accused of abducting and torturing Keith Noyahr in May 2008,[32] murdering Lasantha Wickremetunge in January 2009,[33] and forcibly disappearing Prageeth Ekneligoda in January 2010.[34] It also supported the reinstatement of a senior police officer who had been suspended for allegedly sheltering a fugitive in a rape and murder case in 2015.[35] Although its mandate is to examine cases concerning government officials, the commission entertained a complaint by a private businessman, regarded as close to the president, who is under investigation by the CID.[36]

While seeking to impede investigations and trials of alleged human rights abusers, the commission has threatened to take action against investigators, including former CID investigators Shani Abeysekara and Nishantha Silva, and officials in the attorney general’s office with expertise in combatting money laundering and corruption.[37]

In a letter to Michelle Bachelet, the UN high commissioner for human rights, Sandhya Ekneligoda, the wife of Prageeth Ekneligoda, wrote, “This Commission ... has provided the space for those who are accused of crimes, including enforced disappearances, to raise complaints before the commission, effectively undermining ongoing judicial processes and intimidating victims and witnesses. In his capacity as chairperson … Justice Abeyrathne has been an active participant in enabling this type of violence, labelling and intimidation of victims and witnesses.”[38]

The Presidential Commission of Inquiry on Political Victimization submitted its report to the president on December 9, 2020, but its findings have not yet been revealed.[39] Many of the accused told the commission that they felt persecuted, and made allegations of bias against police investigators who are now seeking refuge abroad or are in detention in

Sri Lanka.[40]

Abolition of Constitutional Safeguards

On October 22, 2020, parliament adopted the 20th amendment to the constitution, which reverses reforms and limitations to presidential power promulgated by the previous government in 2015 under the 19th amendment.

With this new amendment, the president has the power to make senior appointments that were previously made by the Constitutional Council, including of Supreme Court and Court of Appeal judges, the attorney general, the auditor general, and members of the Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka, the Election Commission, the Public Service Commission, the Judicial Service Commission, the National Police Commission, and the Commission to Investigate Allegations of Bribery or Corruption.[41]

It severely undermines the separation of powers, including the independence of the judiciary, and the ability of previously independent institutions to uphold the rule of law in Sri Lanka. According to Paikiasothy Saravanamuttu, director of the Colombo-based think-tank the Centre for Policy Alternatives, the 20th amendment gives the president “effectively unrestrained powers.”[42] The amendment was sharply criticized by two United Nations special rapporteurs for undermining the “independence of the judiciary and the separation of powers, as well as on the independence of institutions which are essential to the establishment of guarantees of nonrecurrence of past gross violations of human rights and serious violations of international humanitarian law.”[43]

On January 13, 2021, the Batticaloa High Court acquitted a pro-government member of parliament, Sivanesathurai Chandrakanthan (alias Pillayan) and four other suspects of the 2005 murder of an opposition parliamentarian Joseph Pararajasingham, after the attorney general decided to drop charges in the case.[44] On November 14 the Court of Appeal had ruled confession evidence inadmissible.[45] Pararajasingham, a member of the Tamil National Alliance, was shot dead while attending midnight mass at Batticaloa Cathedral on Christmas Eve. Chandrakanthan was a member of a pro-government armed group, the Tamil Makkal Viduthalai Pulikal founded by Colonel Karunna Amman (see box below), at the time of the killing. Chandrakanthan was arrested in connection with the case after Mahinda Rajapaksa lost power in 2015. He was elected to parliament in August 2020 and released on bail in November 2020.[46]

Prevention of Terrorism Act

The Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA), which was enacted as an emergency measure in 1979,[47] was made permanent in 1982 and has been in effect ever since. It has facilitated numerous and serious human rights violations.[48] Despite international pledges, the government has not repealed the law.

Ben Emmerson, then-UN special rapporteur on the promotion and protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms while countering terrorism, said after his July 2017 visit to Sri Lanka that the PTA was used “disproportionately against members of the Tamil community,” and that the “use of torture has been, and remains today, endemic and routine, for those arrested and detained on national security grounds.”[49] He added that the most senior judge responsible for PTA cases in Colombo informed him that in over 90 percent of his cases so far in 2017, he had been forced to exclude essential confession evidence because it had been obtained through the use or threat of force.[50]

Juan Méndez, then-UN special rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, said after his 2016 visit to Sri Lanka:

Torture and ill-treatment, including of a sexual nature, still occur, in particular in the early stages of arrest and interrogation, often for the purpose of eliciting confessions. The gravity of the mistreatment inflicted increases for those who are perceived to be involved in terrorism or offences against national security. The police resort to forceful extraction of information or coerced confessions rather than carrying out thorough investigations using scientific methods.[51]

On April 14, 2020, Hejaaz Hizbullah, a human rights lawyer, was arrested under the PTA.[52] He was not produced before a magistrate within 90 days, as the PTA requires, and continued to be held arbitrarily without charge at the time of writing. Three children have alleged that the police attempted to coerce them into making false terrorism allegations against Hizbullah.[53]

On May 16, 2020, Ahnaf Jazeem, 25, was arrested under the PTA in connection with a book of Tamil language poetry he had published three years earlier.[54] The authorities allege that the poems contain “extremist” messages, although a Tamil language scholar protesting his continued detention in January 2021 said their message is “against extremism, violence, and war.”[55] Jazeem remains in detention at the time of writing.

Attacks on Minorities

Members of minority communities, including Tamils, Muslims, and Christians, report targeting of them by both Sinhala Buddhist interest groups and government officials has increased in recent years, and especially since the election of Gotabaya Rajapaksa.[56] In her update to the Human Rights Council on February 27, 2020, High Commissioner for Human Rights Michelle Bachelet said, “The increasing levels of hate speech, and security and policy measures appear to be discriminately and disproportionately directed against minorities, both Tamil and Muslim.”[57]

Beginning around 2012, Sri Lanka experienced a majoritarian Sinhalese nationalist campaign targeting Muslims, with tactics including economic boycotts, threats, and repeated, violent, organized attacks on mosques and Muslim properties.[58] In 2018, there was a spate of lethal anti-Muslim mob violence linked to ultra-nationalist Sinhalese Buddhist groups,[59] which then-Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe called “systemic and organized.”[60] Many of these hardline Buddhist groups, such as the Bodu Bala Sena, and politicians who are associated with anti-Muslim campaigns, were SLPP supporters or members.

In 2019, following the Islamic State (ISIS)-inspired Easter Sunday bombings in Colombo and several other cities in which about 250 people were killed,[61] authorities arbitrarily arrested and detained hundreds of Muslims under counterterrorism and emergency laws, and imposed discriminatory rules targeting Muslims, particularly Muslim women.[62] There was renewed anti-Muslim mob violence in which homes and businesses were destroyed and at least one person died.[63] An investigation by the Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka found that: “There appeared to be no preventive measures taken although retaliatory violence against the Muslim communities was a distinct possibility after the terror attacks,” and that police inappropriately released suspects detained for mob violence, concluding that this “clearly prevented equal protection of the law to affected citizens and also to the public at large.”[64]

Hate speech that circulated in mainstream and social media stigmatized Muslims with baseless conspiracy theories, such as the existence of a plot to lower the birth rate of the majority Sinhalese Buddhist community. Authorities even arrested a doctor over false allegations that he had sterilized thousands of Buddhist women.[65]

Anti-Muslim hate speech and discrimination rose again in 2020, during the Covid-19 pandemic. In March, the government published guidelines requiring that the remains of all Covid-19 victims be cremated, which is counter to Islamic tradition. The World Health Organization has not recommended that governments do this, calling it a “common myth” that those who die of a communicable disease should be cremated.[66] Four United Nations special rapporteurs and many human rights organizations criticized the requirement as a violation of freedom of religion.[67]

There were calls on social media to boycott Muslim businesses and false allegations of Muslims spreading Covid-19 deliberately, which authorities did not contest.[68] After senior government figures made public comments falsely implying that the virus was particularly rife among Muslims,[69] leading activists and civil society organizations wrote to the president raising concerns that this had led to “outpourings of vitriol, and hate speech against Muslims,” to which he did not respond.[70] The government has continued enforcing cremations, even cremating a Muslim baby in December 2020 over the objections of his parents.[71]

Members of the Tamil community, especially in the north and east of Sri Lanka, also face harassment and discrimination. In his report to the Human Rights Council in June 2020, the then-special rapporteur for transitional justice, Pablo de Greiff, wrote:

Psychosocial support is needed throughout Sri Lanka but particularly in the North and East, where trauma and tensions have been exacerbated by official denials of the suffering experienced by Tamil civilians during the civil war, the presence of uniformed personnel and other forms of surveillance, the proliferation of victory monuments and the obstacles to local forms of memorialization.[72]

His findings echoed those of Clément Voule, the special rapporteur on the right to freedom of peaceful assembly a year earlier, who wrote:

I heard stories that mothers of disappeared persons and activists supporting families of the disappeared have been intimidated against organizing and participating in memorial ceremonies and memorial days for those who disappeared.[73]

In November 2020, the government took out court orders at several places in the north and east prohibiting the relatives of disappeared people and activists from participating in memorial events.[74]

In January 2021, the government demolished a monument at Jaffna University which commemorated thousands of Tamil civilians killed at Mullivaikkal in 2009.[75] Public Security Minister Sarath Weerasekera justified the action by saying that "no one will and should be allowed to commemorate dead terrorists".[76] Protesting students in a statement said, "This act is an insult not only to the university students but also to the entire Tamil people. It is also an act of denial of a people's right to memory,"[77]

II. A History of Conflict and Abuse

Although Sri Lanka has not fought a war against an external enemy in its modern history, its extensive security apparatus has spent decades conducting counterinsurgency warfare against internal opponents, notably the Sinhalese left-wing insurgency of the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP),[78] and the Tamil separatist Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE).[79]

The government responded to the JVP-led uprising in the south between 1987 and 1989 by first deploying the police and then the military in joint operations that forcibly disappeared and extrajudicially executed thousands of people.[80] While most of these abuses were perpetrated by unidentified death squads, pro-government armed groups also participated in atrocities. Among those implicated in serious abuses was C.A. Chandraprema, who was linked to the killing of two human rights lawyers in 1989 but never prosecuted – and who was recently appointed as Sri Lanka’s permanent representative to the United Nations in Geneva. [81] The military defeated the JVP as an armed insurrection in 1990, reporting that JVP leader Rohana Wijeweera and other JVP leaders had been captured and killed.[82]

The secessionist war in the north and east stemmed from marginalization and discrimination faced by Tamils. In July 1983, an attack on government troops by a Tamil separatist organization, the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), sparked riots in Colombo and elsewhere, causing several hundred Tamil deaths. The ensuing civil war between the government and the LTTE was marked by widespread violations and abuses of international human rights and humanitarian law by both sides. The war is believed to have cost over 100,000 lives.[83]

Colonel Karuna, Implicated in Abuses on Both SidesOn October 14, 2020, Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa appointed Vinayagamoorthi Muralitharan, better known as Col. Karuna Amman, to his personal staff as district coordinator for Batticaloa and Ampara.[84] As a senior LTTE military commander until 2004, and later as the leader of a pro-government armed group, Karuna is implicated in grave abuses on both sides of the conflict. As a senior LTTE commander, forces under Karuna’s command were responsible for the summary execution of several hundred police officers in June 1990, after they had surrendered to the LTTE. The following month, his forces executed about 75 Muslim travelers. And in August that year, his forces were allegedly responsible for killing more than 200 civilians in Batticaloa district.[85] After Karuna split from the LTTE, causing a serious blow to group’s operations, his forces continued to commit abuses, this time on the government’s behalf. The United Nations, Human Rights Watch, and others reported that Karuna’s group, known as the Tamil Makkal Viduthalai Pulikal (TMVP), was responsible for enforced disappearances, torture, and child recruitment.[86] Karuna has never been held accountable for his alleged crimes. In 2007, he was arrested in the United Kingdom for traveling on a false document. He testified that his fake diplomatic passport had been provided by the then-defense secretary, Gotabaya Rajapaksa, now Sri Lanka’s president.[87] Mahinda Rajapaksa, during his presidency, subsequently appointed Karuna as a government minister in 2009.[88] |

Laws of War Violations

Mahinda Rajapaksa was first elected president in 2005 during a ceasefire with the LTTE from 2002 to 2006, which was overseen by a Nordic-led Sri Lanka Monitoring Mission (SLMM).[89] He appointed his brother, Gotabaya Rajapaksa, as defense secretary.

Full-fledged fighting between government forces and the LTTE resumed in mid-2006.[90] Major military operations that began in 2008 pushed LTTE forces from their main positions in the region of northern Sri Lanka known as the Vanni, including their unofficial capital of Kilinochchi. The government ordered most humanitarian organizations and foreign journalists out, making monitoring of the situation difficult.[91]

The LTTE forces, along with several hundred thousand Tamil civilians, many of whom were effectively used as human shields, withdrew towards the east coast.[92] From January 2009 until the conflict’s end in May, the Sri Lankan armed forces pounded the LTTE and entrapped civilians with artillery and airpower, including intensive targeting of government-declared no-fire zones and well-marked hospitals.[93]

The Sri Lankan security forces in the Vanni were headed by Maj. Gen. Jagath Jayasuriya. He reported to Gen. Sarath Fonseka, the army commander, who reported to the president, Mahinda Rajapaksa, and defense secretary, Gotabaya Rajapaksa.

Six major battalions were involved in the army’s final offensive. The 53rd Division, commanded by Maj. Gen. Kamal Gunaratne, who is currently the defense secretary, and the 55th Division, commanded by Brig. Prasanna Silva, advanced from the Jaffna peninsula in the north. The 56th Division, commanded by Maj. Gen. H.C.P. Gunalithaka, the 57th Division, commanded by Maj. Gen. Jagath Dias, the 58th Division, commanded by Brig. Shavendra Silva, who is now the chief of defense staff, and the 59th Division, commanded by Maj. Gen. Nandana Udawatta, all advanced from the south and southwest.[94]

Even while the fighting raged in 2008-9, the Rajapaksa government dismissed calls for accountability for war crimes by both sides to the armed conflict, insisting that no civilians had been killed. By the time the LTTE was defeated on May 19, 2009, up to 40,000 civilians had died, according to a study by a UN panel of experts.[95] The government later concluded that 7,400 civilians had died in the final four months of the war.[96]

Targeting No Fire Zones: Attacks on Civilians and Hospitals

According to the Report of the Secretary-General’s Panel of Experts on Accountability in Sri Lanka, “Throughout the final stages of the war, virtually every hospital in the Vanni, whether permanent or makeshift, was hit by artillery.”[97]

On January 21, 2009, the government unilaterally declared a 32-square kilometer No Fire Zone (NFZ) to “provide maximum safety for civilians trapped or forcibly kept by the LTTE.”[98] However, soon after, shells hit the Vallipunam hospital, which was located within it, killing at least five civilians.[99] On January 23 and 24, hundreds of shells landed in the NFZ, killing “hundreds” of civilians.[100] In the week between January 29 and February 4, the hospital at Puthukkudiyiruppu (often called PTK), which was packed with hundreds of injured civilians, was hit every day by multi-barreled rocket launchers (MBRLs) and shells, killing over 22 patients and staff, although it was clearly marked and its location had been communicated to the army.[101] On February 12, the government declared a second NFZ, covering a 12-kilometer strip of coast.[102] The second NFZ had three makeshift hospitals.[103] On February 9, shells fell on Putumattalan hospital, killing at least 16 patients.[104]

Throughout the final phase of the war, the government used deliberately low estimates of the number of civilians in the conflict zone to restrict humanitarian supplies.[105] On April 8, 2009, women and children queueing at a milk powder distribution line organized by local health services were shelled at Ambalavanpokkanai.[106] At the same time, the LTTE prevented civilians from fleeing the conflict zone, shooting at families that tried to do so, and restricted delivery of humanitarian aid.[107]

The Sri Lankan government claimed that it pursued a policy of “zero civilian casualties” and characterized its operations as a humanitarian “hostage rescue mission.”[108] The UN, however, concluded that, the government used intense bombardments of heavy weapons and airstrikes until the final moments of the war.

Extrajudicial Killings, Torture, Sexual Violence, and Enforced Disappearances

In the final days of the conflict, around 290,000 civilians as well as a few thousand surrendering LTTE fighters and LTTE members from non-military wings of the organization, crossed over the front lines and entered areas of government control, or came under government control following the capture of the final NFZ on May 18.[109] The army screened the population and removed suspected LTTE cadres, their associates, and relatives. Many of them became victims of enforced disappearance.[110]

Photographs and mobile phone videos, seemingly made as trophies by the victorious soldiers, depict summary executions, including surrendering LTTE cadre. Footage broadcast in the UK by Channel 4 News shows soldiers kicking and executing prisoners, whose hands are tied behind their back.[111] Some of the victims wear military uniform, others are in civilian dress or naked.[112]

From around May 13, two prominent members of the LTTE’s political wing, Seevaratnam Pulidevan and Balasingham Nadesan, began to negotiate their surrender. Senior UN officials and foreign journalists were involved in these negotiations, which also included the president’s brother, Basil Rajapaksa, the defense secretary, and the president.

Pulidevan and Nadesan sought to have international witnesses present at the surrender, but the government refused. Early on May 18, following official instructions, they approached government lines carrying white flags. Witnesses later told the OISL investigators that the leaders surrendered to Sri Lankan army at Mullivaikkal Bridge, along with other cadres, and were later killed. Photographs of their bodies led the OISL investigators to conclude that they had their hands tied when they were shot dead.[113]

Another LTTE leader who surrendered on May 18, Colonel Ramesh, was filmed being interrogated in army custody. His body was later photographed “showing clear indications that he was extrajudicially executed.”[114] The armed forces official website later claimed that Colonel Ramesh, as well as Pulidevan and Nadesan, were killed in fighting with the 58th Division.[115]

Also, on May 18, a group of LTTE cadres, including at least five children, led by a Catholic priest, Father Francis Joseph, surrendered to the army at Vadduvakal. Witnesses described the group being met by a senior officer with “a lot of security around him and a lot of badges on him.”[116] They were driven away in buses and never seen again.

The 2011 report of the government-appointed Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission (LLRC) expressed “grave concern” about the “number of representations concerning alleged disappearances of LTTE cadres who had surrendered to or been arrested by the Sri Lanka Army particularly in the final days.”[117] In January 2020, at a meeting with the UN resident coordinator in Colombo, Gotabaya Rajapaksa stated that the disappeared were dead, but offered little explanation.[118]

Civilians who emerged from the conflict zone were eventually sent to Menik Farm near Vavuniya, which, at its peak, housed around 250,000 people.[119] Screening for suspected LTTE cadres continued with paramilitaries and members of the security forces implicated in torture, rape, and enforced disappearances.[120] Locations at which torture allegedly took place include the camp at Menik Farm, Joseph Camp, which was commanded between 2009-11 by Maj. Gen. Kamal Gunaratne, the current defense secretary,[121] and security forces headquarters in Vavuniya, commanded by Maj. Gen. Jagath Jayasuriya.[122]

After the war the government trumpeted what it referred to as its triumph over terrorism and its false claim of no civilian casualties, and sought to dismiss all allegations of war crimes.[123] Mahinda Rajapaksa won a second term in office in 2010. Journalists and activists who criticized conflict-related violations came under acute pressure. Numerous suspected LTTE supporters and critics of the government were forcibly disappeared, often in operations using white vans that became a notorious symbol of terror. [124]

After Mahinda Rajapaksa lost the presidential election in January 2015, the repression of basic rights to freedom of speech and association was lifted. The new government joined a consensus resolution at the Human Rights Council. It also established a civil society-led task force to hold public consultations and offer recommendations on accountability and truth mechanisms.[125] Key among the task force’s recommendations was the creation of a special court composed of both international and national judges and other officials.[126] There was little progress in implementing most of the recommendations.

The government also began to investigate some emblematic rights violations committed during and after the conflict. However, by the time of the 2019 presidential election, virtually none of those police investigations had led to a verdict at trial.[127]

The Killing of 17 ACF Aid Workers

The killing of 17 humanitarian workers from the Paris-based aid organization Action Contre la Faim (ACF) in the coastal town of Muttur on August 4, 2006, remains one of the most egregious conflict-era violations.[128] In 2013, ACF said it “has closely followed the domestic investigation only to become convinced that the Sri Lankan justice system is incapable of investigating the case.”[129]

Most of the 17 men and women were lined up inside the ACF compound and shot in the head and neck at close range. [130] The victims who were all Sri Lankan, and included 16 Tamils and a Muslim, including four women; they were helping communities affected by the December 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami. Local police said they discovered their bodies two days later.

In the days before the killings, Muttur had been the scene of fighting between security forces and the LTTE, and almost all civilians had left the area. The ACF staff, who had been deployed there only days earlier, were instructed by their head office to remain inside the compound and await evacuation. The office was clearly marked, the staff were wearing T-shirts identifying them as humanitarian workers, and ACF and other humanitarian agencies were in contact with the security forces to arrange the evacuation.[131]

The government was quick to accuse the LTTE of the killings. However, the Sri Lanka Monitoring Mission (SLMM) said that by August 4 the security forces had gained full control over Muttur.[132]

The University Teachers for Human Rights (Jaffna) (UTHR(J)) published a detailed investigation of the ACF massacre.[133] Their report alleged that some members of the security forces had suspected ACF staff of supporting the LTTE, and named three people—Home Guard Jehangir, and police constables Susantha and Nilantha—for the killings. However, the report says that the perpetrators had the approval of senior officers, Sarath Mulleriyawa and Chandana Senayake, who “may have received an instruction from their superiors in Trincomalee, DIG Rohan Abeywardene and SSP Kapila Jayasekere, that the aid workers should be killed.”[134]

Court proceedings began in August 2006. The government agreed to allow Australian experts to observe and assist in the investigation process and the International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) appointed Michael Birnbaum QC as its observer of the inquest into the killings. In March 2007, the Kantale Magistrate’s Court said that there were no leads to those responsible for the murders, accepting “the fact brought to my notice of the prevailing climate of insecurity in the region which inhibits witnesses coming forward to give evidence.”[135] The ICJ observer found “a disturbing lack of impartiality, transparency, and effectiveness of the investigation,” including that the police had blamed the LTTE prior to any investigation and had not “interviewed any member of the Sri Lankan security forces, nor any Tamil, apart from the family members of those killed.”[136]

Partly due to the outcry over the case, the government appointed a Presidential Commission of Inquiry to Investigate and Inquire into Alleged Serious Violations of Human Rights in November 2006, under the chairmanship of N.K. Udalagama. The commission’s full report was not released until September 2015, and, while stating it had insufficient evidence to determine the perpetrators of the ACF killings, it effectively exonerated the security forces and indicated that LTTE forces or Muslim militia carried them out.[137]

The report of the OHCHR Investigation on Sri Lanka (OISL), however, said that the government investigation into the massacre was flawed and lacked independence: “Evidence was either not collected, was tampered with or disappeared from the police investigation.” [138]

In 2008, a US embassy cable by then-Ambassador Robert O. Blake, which was subsequently leaked, observed:

The findings of UTHR(J) cannot come as a surprise to the most powerful people in Sri Lanka. Justice T. Sunthevalingam, appointed Special Rapporteur on Extra-Judicial Killings by President Mahinda Rajapaksa, sent a report to the President about a year ago, which was produced in only 15 copies. It covered much the same ground as the UTHR(J) report, naming many of the same names. However, the President, on receiving the report, ordered that no one else was to see it and that all other copies be destroyed. (Post has nevertheless managed to see a copy of it.).[139]

Ambassador Blake’s cable concluded that “Sri Lanka's legal apparatus has proven itself over decades as being incapable of bringing most such cases to a successful conclusion.”[140]

ACF, in 2013, publicly blamed the security forces for the killings saying that “relevant domestic mechanisms have been exhausted, witnesses have been silenced and the internal Sri Lankan investigation has become a farce.”[141] There has been no known progress in the investigation and no arrests were ever made.[142]

III. Welikada Prison Massacre, November 9, 2012

On the afternoon of November 9, 2012, hundreds of officers from the Special Task Force (STF) of the police arrived at Welikada Prison in Colombo and announced a search operation for illegal mobile phones and recreational drugs.[143] There was a dispute at the gates when prison officials informed the police that, according to regulations, they were prohibited from entering the prison with firearms.[144] However, the STF insisted that they were acting on the orders of “higher ups,” including Defense Secretary Gotabaya Rajapaksa.[145]

According to prisoner witness accounts, once inside the prison, STF members began assaulting prisoners, including by firing teargas into closed cells.[146] They heard prisoners screaming that they were about to be killed. Some prisoners responded by throwing stones, while others managed to enter the prison armory and brandish weapons.[147]

Over the following hours order was restored, with prisoners eventually surrendering the weapons. According to a witness, once control had been regained, police officers began calling out names of inmates to be identified and brought forward.[148] The army arrived around midnight. Later, there were sounds of gunfire. By the time the security forces left the prison the next morning, 27 prisoners had been killed. Initial reports characterized the incident as a search operation that turned into a lethal riot.[149]

Two investigations ordered by the government absolved the security forces and blamed the violence on overcrowding of prisons, easy access to narcotics, and resistance by prisoners to search operations.[150]

The truth emerged after two prisoners, W. Sudesh Nandimal Silva and Sahan Hewadalugoda (also known as Hewa Dalugodage or Sahan Sri Keerthi), spoke out about the incident after they were released.[151] The two men said that members of the security forces, after taking control of the prison, singled out prisoners whose names were on a list, and summarily executed them. Hewadalugoda told the Colombo Telegraph in 2018:

There were many such inmates whose names were read out of a list, were subsequently pointed out by the officials, assaulted, and dragged out. We didn’t see them being shot but we saw our prison officials witnessing the incident and we heard the gunshots.[152]

During her visit to Colombo in 2013, then-UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Navi Pillay said that custodial deaths of prisoners in the Welikada prison were among the investigations that “remain pending.”[153] The lack of progress in the investigation has repeatedly been raised in reports to the Human Rights Council.[154] To date, five official or police inquiries have been ordered into the Welikada massacre.[155]

2015-2019 Investigations

In 2015, the new government brought before parliament the findings of a three-member panel known as the Committee of Inquiry into the Prison Incident (CIPI), which had been appointed under the previous administration. The Sunday Times, after obtaining a copy using a right to information request, said the committee found that 798 armed officers of the STF had been deployed to search two wards of the prison, in violation of procedures, and that these actions led to the riot. It also found that weapons were planted beside the bodies of some of those who were killed to make it appear that their killing was justified.[156]

Gotabaya Rajapaksa testified to the committee that he had no prior knowledge of the operation. But retired STF Commandant DIG Chandrasiri Ranawana, in his evidence, told the committee that the operation was carried out on Gotabaya’s orders, with the coordination of DIG Chandra Nimal Wakishta, who was at the Terrorist Investigation Division (TID) during 2012. The STF was under the control of the defense ministry until 2013. The CIPI recommended a fresh investigation into the massacre.[157]

Amid the ongoing failure to prosecute those responsible, in 2017, Silva, one of the two witnesses, sought an order from the Court of Appeal directing the police to commence an investigation. “I was told by a prison officer that the STF came on an order of former Defense Secretary Gotabaya Rajapaksa,” Silva told journalists.[158] Gotabaya denied the allegations, saying: “Those who point fingers at me are blaming me with their neo-liberal mindsets even for finishing the 30-year war.”[159]

There were repeated allegations of intimidation and threats against witnesses, journalists, and lawyers acting in the case.[160] In July 2017, there were death threats against Silva and against the lawyer and human rights defender Senaka Perera, the night before Silva was due to make a statement to the CID.[161] In September 2017, unidentified gunmen opened fire at Silva’s house.[162]

In March 2018, police arrested Prisons Commissioner Emil Lamahewage and Police Inspector Neomal Rangajeewa of the Narcotics Bureau in connection with the massacre.[163] On July 19 that year, the two men, along with Prisons Officer Indika Sampath, were indicted for 33 crimes, including eight counts of murder, and released on bail.[164] According to evidence gathered by the CID, after the security forces had taken control of the prison on the night of November 9, 2012, eight men whose names appeared on a list were identified by Rangajeewa and summarily executed.[165]

The prison was under the control of the army from about midnight, and the killings continued until the morning.[166] Former Assistant Superintendent of Prisons P.W. Kudabandara testified that two army officers at the prison showed him a list of the names of prisoners who were identified and killed, which they referred to as “Gota’s List.”[167] Several of those selected to be killed had earlier filed complaints at the human rights commission against prison officials, including against Inspector Rangajeewa.[168]

Current Status

Three men, Inspector Rangajeewa, former Prisons Commissioner Lamahewa, and Prison Officer Sampath, were indicted for their role in the killings in July 2019.

Rangajeewa, who had been suspended from service following his arrest in March 2018,[169] was reinstated as an officer of the Police Narcotics Bureau on November 22, 2018, during the period when Mahinda Rajapaksa was briefly installed as prime minister by the former president, Maitripala Sirisena.[170] On July 10, 2020, Rangajeewa assaulted a photojournalist outside the High Court where the trial was in progress, and took him to a police post inside the building where he was forced to delete his camera’s memory card.[171]

On July 15, 2020, Sampath was discharged at the request of the prosecution due to insufficient evidence.[172] The trial continues at the time of writing.

On November 29, 2020, at least eight prisoners were killed and 71 injured when authorities opened fire at Mahara prison on the outskirts of Colombo during a protest against conditions related to the Covid-19 pandemic.[173]

IV. Enforced Disappearance of Prageeth Ekneligoda, January 24, 2010

Prageeth Ekneligoda, a journalist and political cartoonist well known for his opposition to the government of Mahinda Rajapaksa, was abducted on January 24, 2010.[174] This was two days before the 2010 presidential election, in which he was a prominent supporter of Rajapaksa’s opponent, Gen. Sarath Fonseka.[175] He was last seen in public boarding a three-wheeler taxi near his office at around 8 p.m.[176] At the time of his disappearance he was working on a book entitled Pawul Gaha (The Family Tree), in which he intended to detail allegations of corruption against the Rajapaksa family.[177]

A day after Ekneligoda’s disappearance, his wife, Sandhya, attempted to register the case with the police, but they initially refused to take the complaint.[178] There appeared to be no meaningful investigation in the weeks that followed.[179]

On February 19, 2010, Sandhya filed a habeas corpus petition at the Court of Appeal. The authorities repeatedly called for postponements and there was little progress for years.[180] On November 9, 2011, then-Attorney General Mohan Peiris told the United Nations Committee against Torture that “with regard to the journalist Eknaligoda … we have actually investigated that matter very closely. Our current information is … that Mr. Eknaligoda … has taken refuge in a foreign country.”[181] Peiris subsequently retracted the statement.[182]

2015-2019 Investigations

Police investigations found growing evidence that members of the army were responsible for Ekneligoda’s enforced disappearance. On October 19, 2015, the Court of Appeal granted permission to add Army Commander A.W.J.C. de Silva and the director of military intelligence corps as respondents in the habeas corpus case.[183]

In August 2015, police detained Army Sgt. Maj. Jayasundara Mudiyanselage Ranbanda.[184] Ranbanda confessed that he had interrogated Ekneligoda at Girithale army camp for three days following his abduction about the book he was writing, and on his links to Fonseka.[185] He told police that after three days Ekneligoda was taken away by a senior army officer and that he never saw him again.

In August 2015, four military personnel, including two lieutenant colonels, were arrested.[186] In October, 11 more suspects, most of them soldiers or former soldiers, were arrested.[187]

In February 2016, Shani Abeysekera, head of the Criminal Investigation Department, told the Homagama magistrate that officers had received evidence that after being detained at Girithale army camp, Ekneligoda was taken to Akkaraipattu, where he was killed.[188]

Current Status

A decade since Prageeth Ekneligoda’s enforced disappearance there has been no verdict in the case, and his fate remains unknown. Two trials are currently proceeding.[189] In one, at Homagama High Court, concerning an earlier abduction of Ekneligoda in 2009,[190] the next hearing is scheduled for March 4, 2021. In the second case, in which nine army intelligence officers are on trial for Ekneligoda’s disappearance in 2010,[191] a hearing in October 2020 was postponed due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

In testimony to the the Presidential Commission of Inquiry on Political Victimization in August, Jayasundara Mudiyanselage Ranbanda, a key witness reversed his earlier testimony in the case, in which he had incriminated military intelligence officers.[192] In a letter to Michelle Bachelet, the UN high commissioner for human rights, Sandhya Ekneligoda, the wife of Prageeth, wrote, “Major Retd. Ranbanda has already been summoned to provide evidence before the Commission, despite the matter being before Court and a court order prohibiting him from giving evidence before any other forum. With his active involvement, the Commission, took steps to undermine, intimidate and threaten investigators and witnesses in this case, while denying an opportunity for the aggrieved party before the High Court, to be heard or make submissions to protect their interest.”[193]

V. Tripoli Platoon, Targeting Journalists

The investigation into the killing of journalist Lasantha Wickrematunge implicated Gotabaya Rajapaksa and exposed the existence of a military intelligence unit called the Tripoli Platoon, which allegedly targeted journalists including Wickrematunge and Keith Noyahr. The investigation by the police CID also uncovered two other killings associated with the alleged conspiracy, while two people related to the enquiry died in suspicious circumstances.[194] In June 2020, a journalist, now in hiding, said he had been targeted in 2008, then again in November 2019. “Every time the Rajapaksas come to power, journalists are threatened,” he said.[195]

Abduction of Keith Noyahr, May 22, 2008

Keith Noyahr was the deputy editor of the Nation newspaper and a well-known investigative journalist when he was abducted on May 22, 2008. That night he had been dining with colleagues at a Colombo restaurant. His wife found his car empty with the engine running and lights on, and the driver’s door hanging open, outside their home at around 11 p.m. The discovery triggered a frantic search for the missing journalist. He was found early the following morning, badly beaten, and suffering from multiple injuries.[196] Noyahr left the country following the attack and the investigation ended.[197]

2015-2019 Investigations

The case was reopened in 2015, at the request of detectives investigating the 2009 murder of another journalist, Lasantha Wickrematunge.[198]

On the night Noyahr went missing, his editor, Lalith Allahakkoon, and the company chairman Krishantha Cooray, telephoned President Mahinda Rajapaksa and the defense secretary, Gotabaya Rajapaksa, setting off a sequence of telephone calls. These calls were later produced in court by CID investigators as evidence that military intelligence was involved, and that Noyahr was eventually released because of orders through the chain of command.[199]

Phone records showed that after Allahakkoon and Cooray raised the alarm, Gotabaya made two calls, one to the inspector general of police, Jayantha Wickramaratne, and then to the intelligence chief, retired Maj. Gen. Kapila Hendawitharana, at 11:39 p.m. At 11:41 p.m., Hendawitharana called Brig. Amal Karunasekara, the director of military intelligence. Karunasekara then called the commanding officer of the military intelligence unit based at the Tripoli Camp in Colombo, Major Bulathwatta, at 11:48 p.m.[200]

The CID took a statement from Noyahr, who was by then in Australia, which was produced as evidence in court.[201] Noyahr told the police that his captors had assaulted him and demanded that he identify his sources. He was taken to a house where he was blindfolded and stripped. While they continued to assault him, one of his captors received a telephone call and replied, “Okay sir, okay sir.” After the call, his abductors stopped the beatings and later dumped him in the Dehiwala area of Colombo.[202]

Detectives investigating the abduction identified the military intelligence “safe house” at Dompe, outside Colombo, where Noyahr was allegedly taken.[203] In February 2017, they arrested five members of military intelligence including Major Bulathwatta.[204] The following month they located the van they believe was used in the abduction.[205] Retired Maj. Gen. Amal Karunasekara, who had been director of military intelligence at the time of the abduction, and was later chief of staff of the Sri Lankan army, was arrested on April 5, 2018, on charges of aiding and abetting the abduction.[206] In August 2018, detectives took statements in the case from both Mahinda and Gotabaya Rajapaksa.[207]

Current Status

Nine serving or former members of military intelligence,[208] eight of them belonging to the Tripoli Platoon, which is also implicated in other attacks on journalists, have been arrested and released on bail. Major Bulathwatta, who was arrested in 2017, was reinstated to a military intelligence role by President Sirisena in May 2019 following the Easter bombings.[209] In February 2020, he was promoted to lieutenant colonel by President Gotabaya Rajapaksa.[210]

In August 2019, lawyers appearing for the police told a magistrate that the case was ready to be sent for trial.[211] In September 2019, the attorney general complained to the police about delays in submitting files necessary for the case to be submitted for trial.[212]

The CID’s investigation of the case was examined by the the Presidential Commission of Inquiry on Political Victimization, which has submitted its report to the president.

Murder of Lasantha Wickrematunge, January 8, 2009

Lasantha Wickrematunge, one of Sri Lanka’s most prominent journalists, and the founder and editor of the Sunday Leader newspaper, was murdered while driving to work on the morning of January 8, 2009, allegedly by members of military intelligence.[213]

Wickrematunge was aware of the danger he was in. His daughter, Ahimsa Wickrematunge, later told the CID that her father believed he was being targeted by Gotabaya Rajapaksa because he was working on an exposé of alleged defense ministry corruption.[214]