Summary

On March 27, 2020, Kenyan authorities introduced measures to contain the spread of the novel coronavirus, including a dusk-to-dawn curfew and a directive to Kenyans to work from home. For “Wanjiku,” a 27-year-old pre-school teacher and single mother living in Mukuru Kwa Reuben, an informal settlement in Nairobi, that would be the start of the most difficult nine months of her life.

Her employer, a private school in Mukuru Kwa Reuben, immediately notified her and other staff that they would not be paid for as long as the school remained closed due to the pandemic. When Human Rights Watch interviewed Wanjiku, who was with “Janet,” her four-year-old daughter, in November 2020 when schools were still under lock and key, they were struggling to make ends meet. It wasn’t until January 2021 that schools reopened.

Two days before the start of the lockdown, on March 25, President Uhuru Kenyatta announced a range of measures to cushion the economic impact of the pandemic, including adding Ksh10 billion ($100 million) to a social protection fund for the older people, orphans and those with underlying health conditions. About two months later, the president announced a cash transfer program for the most socio-economically vulnerable populations, including people with disabilities, pointing out that his administration was already paying out Ksh250 million ($2.5 million) to the most vulnerable households each week.

In April, Wanjiku registered for the cash transfer program based on information from authorities that those who had lost income were eligible, but she has never received any assistance, and she has not received any information on why she was not considered for assistance or if she could appeal or challenge the decision to leave her out.

Kenya has no system of social security to pay income to those who lose jobs and although government stated this as one of the objectives of its Covid-19 cash transfer program, the outlined criteria did not include job loss as one of the factors to be considered during the selection of beneficiaries.

For Wanjiku, going without food for several days a week became routine, as her low paying temporary jobs, such as washing clothes, did not provide enough to feed her family for more than three days a week, as she struggled to provide her family with the most basic needs. Janet constantly cried for something to eat; her mother told Human Rights Watch. As of November 2020, Wanjiku owed several months in rent and did not know how she would be able to meet her rent commitments for the coming months. Although the landlord had not evicted her, his reminders to pay were a source of significant anxiety, as she would have nowhere to shelter with her young daughter should the landlord decide to evict them.

Wanjiku is just one of the many Kenyans in informal settlements whose livelihoods have been devastated by the Covid-19 pandemic, yet did not benefit from the government’s cash transfer program that could have guaranteed them the enjoyment of the right to food and shelter, at least for the duration of the pandemic. Kenya does not guarantee social security for all and does not protect the right of everyone to an adequate standard of living, including adequate food and shelter at all times, even during an emergency.

Human Rights Watch’s analysis of available government data and information provided by government officials indicate that the Covid-19 cash transfer program provided support to less than five percent of the socio-economically vulnerable families in Nairobi, and an even smaller percentage across the nation, which means that the government failed to guarantee the right to an adequate standard of living for more than 95 percent of vulnerable households.

Kenya is a lower-middle income economy whose population has doubled over the past three decades from 23.72 million in 1990 to 47.5 million in 2020, which means that, even in the absence of emergency situations like the coronavirus pandemic, a growing number of Kenyans have been struggling to attain an adequate standard of living. Along with burgeoning population growth has come alarmingly widening economic disparities both between and within the nation’s eight regions and among the same population in a given region.

At least 36.1 percent of the population – 17.1 million Kenyans – live below the international poverty line, a measure of extreme poverty defined as earning less than $1.90 a day, according to the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, while 66.2 percent live on less than $3.20 a day, and 86.5 percent on less than $5.50, according to the World Bank. As of 2015, half of Kenyans were living in multidimensional poverty, a measure that uses a weighted index of ten factors related to health, education, and living standards.

Poverty rates are especially high – above 70 percent – in the remote, arid and sparsely populated northeastern parts of Kenya. Some large cities also have high poverty rates; for example, 44 percent of Mombasa residents are classified as poor, compared to 42 percent of people in the capital of Nairobi. However, the abysmally low poverty line of $1.90 per day masks the huge numbers of people in higher-cost cities like Nairobi who struggle to afford basic necessities. Despite stubbornly high poverty rates, Kenya’s existing social protection system is not as robust and does not guarantee social security to everyone, which made it even more difficult to expand existing programs to identify and reach families in need of support during the pandemic.

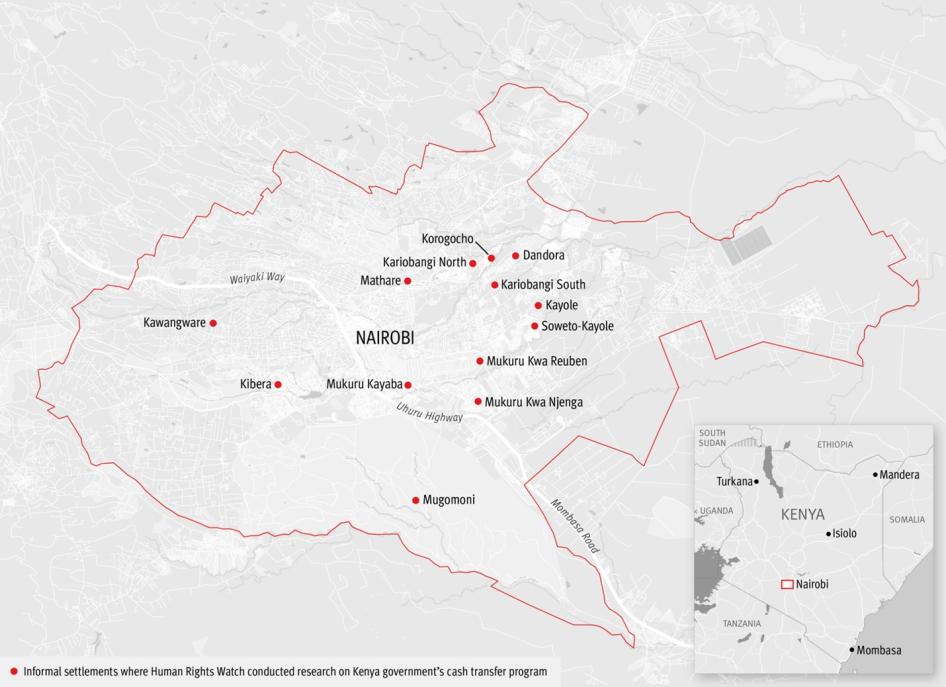

Based on interviews with 136 people, including 102 residents of 11 informal settlements in Nairobi – of which 82 were women – senior national and local administration officials, community and resident’s association officials, and a representative of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), this report examines the effectiveness, at least in terms of ensuring the right to an adequate standard of living for all, of the cash transfer program introduced to cushion the devastating impact of pandemic – related lockdowns. The report focuses primarily on informal settlements (Kibera, Mukuru, Korogocho, Mathare, Kangemi, Kawangware, Kariobangi, Dandora, Mugomoini, Kayole, Kayole Soweto and Dagoretti Waithaka) in Nairobi county, one of the 21 counties where the authorities implemented the program. Kenya has 47 counties in total.

The research focused on Nairobi in part because it has the fastest growing number of informal settlements in the country and was one of the counties targeted by the government’s pandemic-related cash transfer program. Of the 10 million people living in informal settlements across Kenya, 2.4 million live in Nairobi – making up half the city’s population yet crammed into only 1 percent of its land. Residents of informal settlements, who are the most likely to live in extreme poverty and thus struggle to meet their basic needs, were also the most socio-economically affected by the Covid-19 pandemic, according to the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP).

Government-imposed public health measures intended to curb the spread of the virus, such as partial lockdowns and curfews, were more challenging to adhere to in informal settlements and had harsher economic consequences. Government officials told Human Rights Watch that more than 60 percent of businesses in informal settlements were closed during the partial lockdown, exposing thousands of families to serious economic hardships. High population density, lack of basic public services, poor electricity access, and pre-existing high rates of unemployment exacerbated the impact of these measure on residents. Most employed residents work as unskilled laborers, earning around or below $1.90 (Ksh190) per day, an amount that leaves many unable to afford a minimum standard of nutrition and other necessities.

There is a gender dimension to poverty in Kenya According to government data, women are more likely to be unemployed, underemployed, underpaid, and seasonal workers. Females constitute 64.5 percent of the unemployed, 61.9 percent of all part time workers, and majority of the underemployed. Kenya’s 2015/16 Integrated Household Survey results show that more than a third of households are headed by females, and that 30.2 percent of female headed households live below the poverty line compared to 26.0 percent of their male counterparts. A survey conducted in May 2020 showed that the labor force participation rate in the seven days preceding the survey was higher for males (65.3 percent) while slightly more than half (51.2 percent) of the females were found to be outside the labor force in the reference period.

Human Rights Watch spoke with dozens of people living in Nairobi’s informal settlements who said that, since the lockdown-induced loss of jobs and economic crisis, they have faced extreme hunger, going entire days without meals, in some cases up to four days a week, and have accumulated rent arrears of up to nine months. Several said landlords evicted tenants for nonpayment of rent while some men abandoned their families – spouses and children – in the city altogether and returned to their upcountry homes.

Also, most women in Kenya work part-time in the informal sector, including as domestic workers where they cannot render services remotely, thereby losing income, and in the service industry, where they are likely to have no job security and safety nets when crises such as Covid-19 hit the economy.

Despite President Kenyatta’s pledge to cushion the most economically and socially vulnerable from the impact of the government’s pandemic response, few households received the promised relief. The cabinet secretary for Treasury and Planning, Ukur Yatani, told Human Rights Watch in January 2021 that the cash transfer program ran from April 22 to November 27, 2020 and, in its first phase, targeted 85,300 households in four counties: Nairobi, Mombasa, Kilifi and Kwale.

In its second phase, he said the program reached an additional household in 17 other counties. He added that the authorities prioritized support for households in informal settlements with high poverty index; where the head or breadwinner has a physical disability; is widowed; is a minor (orphan or child-headed households); have pre-existing medical conditions such as cancer or HIV; has a mental health condition and are not benefiting from other government support.

The whole country remains, at time of writing, under a dusk-to-dawn curfew that began in March 2020 when the pandemic hit. For 30 days in April 2021, travel to or from Nairobi, Kajiado, Machakos, Kiambu and Nakuru counties was also prohibited. Of the 85,000 households that benefitted from the cash transfers in the first phase, 29,000 were from informal settlements in Nairobi county – which amounts to less than 5 percent of the 600,000 households in Nairobi’s informal settlements.

Moreover, this report found that the cash transfer program lacked clear rules and basic transparency and did not appear to recognize that everyone has a right to social security and an adequate standard of living, including food, leading many eligible people not to be registered and enabling corruption and favoritism in its implementation. There is no mechanism for people like Wanjiku who missed out, to appeal or challenge the decision to leave them out. Authorities did not publish any information about the program’s start date and duration; eligibility criteria; or the amount and frequency of payments.

In addition, the national government’s devolution of implementation to multiple groups with little coordination or oversight compounded corruption risks. Human Rights Watch interviews surfaced numerous allegations that officials in charge of enrolment frequently ignored government-approved eligibility criteria, which failed to ensure the assistance reached everyone at risk of hunger, and directed benefits to their relatives or friends, even in cases when they did not meet the criteria.

Many of the residents of informal settlements in Nairobi with whom Human Rights Watch spoke, who appeared to be eligible for the program, said they did not register for it because they were simply not aware of its existence. Others, including those living in households headed by people with disabilities, have serious pre-existing medical conditions such as cancer or HIV/AIDS, and older people, said they registered but did not receive any benefits. Several said they received some cash transfers between April and July, although the number of payments varied widely and some reported that they received the money for only one or two months. Only a small fraction of beneficiaries said they received the cash for the entire authorized period that extended from April to November.

This report found that, in some areas, the authorities engaged Nyumba Kumi, or village elders who head clusters of 10 households, to oversee the program’s implementation, while in other areas it fell to community health volunteers or resident savings associations. Interviewees charged with enrollment told Human Rights Watch that they had not been trained or given any selection criteria or guidelines and they therefore selected people they knew.

Some beneficiaries said they were enrolled by local politicians, who were either given free reign by authorities to select a certain number of people or who were given control over enrolment delegated to others. The report found that the involvement of politicians made the process more vulnerable to cronyism than when implemented by Nyumba Kumi cluster leaders or Community Health Volunteers. At least six residents of informal settlements alleged that members of parliament and Nairobi county assembly used their allocated benefits for friends and family members, even in cases when they were not eligible. In Mukuru Kwa Reuben, a 29-year-old father of two who benefited from the cash transfers after he was enrolled/registered by a Nairobi politician told Human Rights Watch that he has a stable job with a decent salary and wasn’t really in serious need.

Even for those lucky enough to be enrolled, not all ultimately received the cash. Government officials told Human Rights Watch that about half of those enrolled received the money, and not throughout the authorized duration. It is unclear who and how the decision was made to drop some of the enrolled names. Human Rights Watch calls on Kenyan authorities to make a comprehensive list of all households that received cash transfers available to the auditors and any other government agencies monitoring the program.

The frequency of the transfers also varied. Contrary to the government’s claim that each beneficiary received a total of 35 transfers in eight months, most of those who spoke to Human Rights Watch said they received the transfers just twice or four times in that period. While some beneficiaries received the cash weekly, many received money every two weeks and others once a month.

Like for many countries, the challenges Kenyan officials face in the midst of a health crisis to effectively provide support to families on the brink of hunger exposes the huge gaps in the country’s existing social protection system. There is no recognition of the right of everyone to social security nor any attempts to create a comprehensive system of social security. The efforts to expand coverage, and the lessons learned, present a critical opportunity to develop social protection programs based on the right of everyone to social security and to an adequate standard of living.

According to the World Bank, the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic will push an additional 88 million to 115 million people into extreme poverty worldwide, bringing the total to between 703 and 729 million. The “new poor” is forecasted to be more urban than those who have persisted in poverty for a longer time; more engaged in informal services; live in congested urban settings; and work in the sectors most affected by lockdowns.

Kenya, as a state party to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) is obligated under article 11 to ensure that Kenyans enjoy the right to an adequate standard of living, including adequate housing as well as the fundamental right to adequate food and freedom from hunger and malnutrition. There are similar protections under article 25 (1) of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR).

In General Comment 12, the ICESCR Committee, which monitors implementation of the International Covenant on economic, social and cultural rights by its States parties, said that whenever an individual or group is unable, for reasons beyond their control including natural or other disasters, to enjoy the right to adequate food by the means at their disposal, governments have the obligation to provide that right directly.

ICESCR and other human rights law also require Kenya to respect and implement the right of everyone to social security. The African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, which interprets the African Charter and considers individual complaints, has interpreted the right to social security as implicit from a joint reading of several rights guaranteed under the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights including the rights to life, dignity, liberty, work, health, food, protection of the family and the right to the protection of the aged and the disabled. Kenya is a state party to the African Charter and has included these rights in its national constitution.

Human Rights Watch calls on the Kenyan government to take urgent steps to fulfil its obligation to ensure that residents of informal settlements can meet their basic needs to adequate food and housing. The authorities should investigate the implementation of the cash transfer program and hold those credibly implicated in any misuse or misappropriation of funds should be held to account. The government should guarantee that social assistance programs respect the principles of equality and nondiscrimination.

Glossary of Terms

|

AfDB |

The African Development Bank is a regional finance institution established to contribute to the economic development and social progress of African member countries. |

|

Chief |

A local government administrator who oversees an administrative location, the second smallest administrative unit. An assistant chief oversees a sub-location, the smallest administrative unit. |

|

Community Health Volunteers |

Volunteer health workers in informal settlements who support and educate their communities on health matters. |

|

County |

Geographical government units headed by a governor. |

|

County Commissioner |

A representative of the national government and head of security at the county level. |

|

Covid-19 |

COVID-19 is a disease caused by a new strain of coronavirus. 'CO' stands for corona, 'VI' for virus, and 'D' for disease. Formerly, this disease was referred to as '2019 novel coronavirus' or '2019-nCoV. |

|

Economic inequality |

This is the unequal distribution of income, wealth, and the unequal access to economic opportunities between different groups of people in a given society. |

|

EACC |

The Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission is a constitutional body created by the Kenyan government “to combat and prevent corruption, economic crime and unethical conduct in Kenya through law enforcement, prevention, public education, promotion of standards and practices of integrity and ethics.” |

|

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) |

This is the total value of goods produced and services provided in a country during one year. |

|

ICESCR |

International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights is a multilateral treaty which requires its parties to ensure economic, social and cultural rights for everyone, including the right to social security, labor rights and the right to health, the right to education, and right to an adequate standard of living. |

|

IMF |

International Monetary Fund (IMF) is an organization of 190 countries with a stated mission of “working to foster global monetary cooperation, secure financial stability, facilitate international trade, promote high employment and sustainable economic growth, and reduce poverty around |

|

Informal Settlements |

Housing, shelter, or settlement in an urban area where inhabitants have no or limited security of tenure vis-à-vis the land or dwellings they inhabit; where their neighborhoods usually lack, or are cut off from, formal basic services (e.g. water, sanitation, electricity, roads, drainage) and city infrastructure; and where housing may not comply with current planning and building regulations. Informal settlements are often referred to as slum communities or slums, but despite their high poverty levels and lack of basic infrastructure, people living in slums in some cases have security of tenure and recognition in the formal housing sector. |

|

International Poverty Line |

This is a monetary threshold used by the World Bank under which an individual is considered to be living in poverty. It is currently set at $1.90 per day (in 2011 Purchasing Power Parity dollars), a threshold frequently criticized as too low and measuring extreme poverty. In 2018, the World Bank introduced additional poverty metrics, these include higher poverty lines at US$3.20 and US$5.50 a day. |

|

Kazi Mtaani |

The Kenyan government’s Cash for Work relief program established in July 2020 in response to the Covid-19 pandemic, targeting up to 200,000 young people across the country. Young people employed in the program do menial jobs such as cleaning sewers, sweeping roads, and collecting rubbish in return for pay. |

|

KNBS |

Kenya National Bureau of Statistics is a state agency responsible for the collection and storage of data across all sectors of Kenya’s economy. |

|

Mpesa |

A mobile money service offered by Kenya’s largest telecommunication company, Safaricom. The authorities disbursed cash transfers through Mpesa to vulnerable families during Coronavirus partial lockdown in 2020. |

|

Multidimensional Poverty |

The global Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI), introduced by the United Nations in 2010 to replace the Poverty Index, is an international measure of acute multidimensional poverty covering over 100 developing countries. It captures acute deprivations in ten indicators, including health, education, and living standards that a person faces simultaneously. The MPI assesses poverty at the individual level. If a person is deprived in a third or more of ten (weighted) indicators, the global MPI identifies them as ‘MPI poor’. |

|

Poverty |

This refers to a situation where people lack enough resources to provide the necessities of life such as food, clean water, shelter, clothing, health care, education, and transportation. |

|

Poverty Index |

Introduced in 1997 by the UN, this is a composite index that assesses three elements of deprivation in a country – longevity, knowledge, and a decent standard of living. |

|

Nyumba Kumi |

Literally translates as “Ten Households,” which is a community policing system Kenya introduced in 2013 where a cluster of 10 households is placed under the jurisdiction of one older person chosen by government officials who is supported by a team of young people he chooses. |

|

OHCHR |

Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, the department of the UN secretariat that promotes and protects rights guaranteed under international law and stipulated in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948. |

|

Peri-Urban |

A settlement located in an area immediately adjacent to a city or urban area. |

|

Rapid Credit Facility |

An IMF facility that provides emergency financial assistance with limited or no conditions to low-income countries. However, requesting governments write Letters of Intent that include commitments regarding how they will use the funds. |

|

Safaricom |

The leading communications company in Kenya with the widest coverage, and provider of the mobile money service, MPESA. |

|

SIDNET (or SDI) |

A network of community-based organizations working in informal settlements in 33 countries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. SIDNET and member federations are helping people in 500 cities secure land rights and participate in income generating programs. |

|

Social Justice Centers |

These are community movements of young rights activists in informal settlements and rural communities who promote justice in their communities. |

|

Sub county |

A smaller administrative unit delineated by the national government and headed by the sub county commissioner. |

|

UDHR |

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights outlines the rights and freedoms to which everyone is entitled. It sets out the key principles of human rights. |

|

UNDP |

United Nations Development Programme, a UN agency established in 1965 to help countries eliminate poverty and achieve sustainable human development. |

|

WFP |

World Food Programme, the food-assistance specialized agency of the UN. It is the world's largest humanitarian organization focused on hunger, food security, and the provision of school meals. |

Recommendations

To President Uhuru Kenyatta and the National Government

- Publicly recognize the rights of everyone to social security and to an adequate standard of living and announce that government policies will be based on

these rights. - Direct the relevant government departments implementing the cash transfer program to publish all information on the criteria for allocation and distribution of social protection funds aimed at mitigating the socio-economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, including details of amounts disbursed across Nairobi and other counties where the program was implemented, and to make the list of names of beneficiaries available for the Auditor General, Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission and other relevant government agencies.

- Direct the Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission to promptly and thoroughly investigate allegations of irregularities or misappropriation of money meant for the cash transfer program and submit the files to the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions for prosecution.

- Direct the relevant state departments to, in the short term, re-start the emergency cash transfer program given the control measures are still in place and allocate more funding to greatly expand it for as long as the government of Kenya has Covid-19 pandemic-related measures in place to ensure that all vulnerable households, including those in Nairobi’s informal settlements, have the means to afford food, rent, and other expenses fundamental to human rights.

- Direct all relevant state departments to take steps to mitigate gendered impacts of Covid-19 and ensure that responses do not perpetuate gender inequity.

- Direct relevant government departments to, in the long term, develop robust social protection programs with an ultimate aim of providing assistance to all people who need it and can be easily scaled up in crisis situations.

- Set up a system of social security, based on the right of all Kenyans to social security, that is adequate to ensure an adequate standard of living for all, accessible to everyone and is protected in law.

- Consider introducing broad and well thought out, gender-sensitive economic stimulus measures that would enable small and medium businesses, including those in informal settlements in Nairobi and other urban areas, to easily access credit facilities or startup capital at no or low interest.

- Increase funding to the ministry of Labour and Social Protection, which is responsible for implementing the cash transfers, both as an immediate response to the pandemic and in the longer term.

To the Ministries of Treasury and Planning, Labour and Health

- Extensively review and strengthen internal mechanisms for implementing cash transfers, including the criteria for selecting vulnerable households and accountability mechanisms such as oversighting, supervision and training of selectors, and complaint mechanisms. Publish all relevant information, including eligibility criteria, number of households supported, and total amounts received.

- Continue the cash transfers until the economic impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic have subsided and expand the number of beneficiaries of the transfers, preferably consider covering all in informal settlements in Nairobi.

- Ensure the mechanisms for survey and mapping vulnerable households in Nairobi and other areas where the cash transfer program is implemented are adequately and fairly reviewed to ensure all vulnerable households are identified, reached

and supported. - Ensure thorough and timely audit of the cash transfer funds and, in the event of irregularities and/or misuse of money, ensure all those responsible are held

to account. - Compile names of all beneficiaries of cash transfers across Nairobi and other counties where the program was implemented, make the list available to the Auditor General, Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission and other relevant government agencies.

- Ensure that existing guidelines on Covid-19 control are practical in informal settlements and other urban areas, including by publishing additional guidelines where necessary.

- Ensure that any targeted allowances benefit all families that are eligible, by taking the following steps:

- Establish the right of all Kenyans to social security as the basis for these allowances;

- Establish effective communications strategies to ensure that everyone knows about the social protection program, its eligibility criteria, and the means of accessing it;

- Make the application process accessible to all, including those with low literacy and/or no internet access;

- Ensure that women are able to apply and receive these benefits as heads of households;

- Invest in selection mechanisms that do not overestimate incomes of any applicant;

- Avoid placing quotas on the number of people who can access a program;

- Ensure that people can apply for the program whenever they require it;

- Ensure that decisions on selection are as objective as possible;

- Eliminate discrimination in decision-making;

- Keep comprehensive information on selection decisions;

- Establish effective and independent grievance mechanisms that enable applicants to appeal unfavorable decisions;

- Maintain a comprehensive database of information and statistics to inform planning and identification of beneficiaries for targeted allowances;

- Ensure adequate social protection budgets to provide a minimum social protection package for households with children.

To the Auditor General

- Assess the effectiveness of the internal controls and overall implementation, including transparency and frequency of cash disbursements, of the government’s pandemic – related cash transfer program.

- Undertake a timely and thorough audit of the entire process of the government’s pandemic – related cash transfer and publish the findings.

To the Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission (EACC)

- Initiate timely and thorough investigations into the implementation of the government’s pandemic–related cash transfer program, including possible irregularities in the disbursement of funds, and publish the findings.

- Immediately institute, in line with the asset recovery procedures from the public officials and companies who illegally benefited from the cash transfer program the recovery of any assets they may have acquired through such wealth.

To the Parliament

- Ensure that the relevant parliamentary committees collaborate to initiate independent public enquiries and fact-finding on how the pandemic – related cash transfer was implemented, including looking into allegations/reports of misuse

of funds. - Make public the findings of any such investigations or inquiries by the relevant parliamentary committees on the use of funds meant for the pandemic-related cash transfers.

- Initiative bills and motions to guide the reform process in the management of public resources, especially in the management of disasters and public emergencies such as the Covid-19 pandemic.

- Ensure that any reforms introduced in the ministries of treasury and planning, health and labor, are replicated in other ministries to enhance transparency and accountability mechanisms in budgeting, allocation, disbursement, procurement, utilization and audit processes on public funds.

The Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions

- In conjunction with the Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission, urgently prosecute those implicated in the mismanagement or misuse of resources meant for the pandemic - related cash transfer program.

To African Development Bank, World Bank, and International Monetary Fund

- Provide additional financial resources and technical expertise to enable Kenyan authorities to expand the reach of cash transfers to particularly include people pulled further into poverty because of the Covid-19 pandemic, including in informal settlements in Nairobi and other urban areas, and marginalized women and girls.

- Privately and publicly, urge Kenyan authorities to ensure the Auditor General has access to all documents relating to the pandemic - related cash transfers to enable prompt and thorough audit.

- As partners of the Kenyan government contributing resources for response to the Covid-19 pandemic, urge Kenyan authorities to establish minimum safeguards to ensure public participation in decision making at all levels including at the national level for improved service delivery and accountability.

Methodology

This report is based on Human Rights Watch research in 11 of the 14 informal settlements in Nairobi county. Nairobi is among the 21 counties the Kenyan government selected, out of the country’s 47 counties, to implement cash transfers to cushion the most vulnerable households against the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic. This research focused only on Nairobi county.

For five months - between September 2020 and January 2021 – Human Rights Watch researchers interviewed residents of the following informal settlements in Nairobi: Mathare, Mugomoini, Kayole, Soweto-Kayole, Mukuru Kwa Njenga, Mukuru Kayaba, Mukuru Kwa Reuben, Kibera, Kawangware, Dandora, Korogocho and the wider Kariobangi (South and North).

Human Rights Watch interviewed a total of 136 people, of which 82 were women, including 31 beneficiaries of the cash transfers, 62 people who did not benefit despite meeting government criteria, two senior national government officials, eight national government administrators in the informal settlements who had responsibility for selecting cash transfer beneficiaries in their jurisdictions, a representative of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and 10 community health volunteers.

Researchers further spoke with 11 activists, including two officials of residents’ associations, in Kayole, Dandora, Kawangware and Mathare settlements. These activists had worked with local administrators to identify and recommend potential beneficiaries for enrolment into the cash transfer program. Two of the activists were also among the 31 beneficiaries of the program.

Residents of informal settlements interviewed for this report described the size of their households, sources of income and impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on their income, their ability to feed family members, pay house rent during this period, whether they received any support, including from the government cash transfer program or other programs such as the one by World Food Programme and GiveDirectly, and in the case of those who receive government support, how they got enrolled, and the regularity of payments. They also gave their opinion on whether the amount they received was adequate.

The residents also explained how they learned about the enrolment of beneficiaries for the program, whether the information was readily provided by the authorities and expressed views on the transparency and fairness of the enrolment and disbursement processes. We further talked to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) representative in Kenya as well as senior staff of the World Food Programme and GiveDirectly. Researchers also reviewed government policy documents and independent research publications relevant to

this report.

On December 7, 2020, Human Rights Watch wrote to the ministries of Treasury and Planning, Labour and Health with a set of questions on the cash transfer program and how it was implemented. On January 19, the cabinet secretary for Treasury and Planning, Ukur Yatani, responded with details about enrollment criteria for the cash transfer.

Where relevant, Human Rights Watch has withheld identities of the interviewees to protect them from potential reprisals by the authorities and others. All interviews were held confidentially, in safe locations, in full observation of measures to prevent the transmission of the virus, and with full and informed consent of interviewees. The interviews were conducted mainly in Swahili, and, in a few instances, in other local languages, including two with the help of an interpreter. No compensation was requested by interviewees and none was provided.

I. Background

Poverty and Inequality in Kenya

Kenya, a lower-middle income economy, has grown rapidly over the last three decades from a population of 23.72 million in 1990 to 47.5 million people (or 12.5 million households) in 2019, according to the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics and United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA).[1] Studies by experts over that period shows that economic disparities both between and within regions has continued to widen.[2]

With a Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of US$95.5 billion, Kenya's economy remains the largest and most developed in eastern and central Africa region. However, 36.1 percent of its population – 17.1 million Kenyans – still lives below the international poverty line of $1.90, according to official government data.[3] According to the 2015 Kenya Population and Housing Census, there are about 19.5 million people with low income in Kenya, which means a staggering 41 percent of the population in Kenya will struggle to meet basic needs or, put simply, realize their right to an adequate standard of living, especially in the absence of universal state support to everyone.[4]

An average of 14 million of that population is in rural areas, 1.3 million in peri-urban areas and 4.2 million in informal settlements.[5] Of the 4.2 million in informal settlements across Kenya, around 2.4 million, or more than half, are in Nairobi’s informal settlements, the focus of this report.

Studies by various groups including Oxfam and Society for International Development have demonstrated the increasing levels of social and economic inequality in Kenya. For example, 10 percent of Kenyans control or own approximately 44 percent of the national wealth[6] and account for over 70 percent of income, while the poorest 10 percent earn less than one percent of the national income.[7] In April, the UNDP expressed concern that the

Covid-19 pandemic could reinforce these income inequalities.[8]

There are also disparities in poverty levels across regions in Kenya. The percentage of poor people, for instance, is lower in the capital, Nairobi at 44 percent, and in some areas – such as rural areas where poverty is above at 70 percent.[9] Poverty rates are much higher – above 70 percent – in the remote, arid and sparsely populated northeastern parts of the country or even the poorest areas of Nairobi.[10] At the same time, on average, population of poor people in Nyanza region’s five counties of Siaya, Kisumu, Migori, Homabay and Kisii is at 63 percent.[11]

Kenya’s Administrative StructureThe current structure of government allows power at two levels: the national level, headed by the president and his deputy, and the county level, headed by the governor and is semi-autonomous with devolved functions. The national government is composed of 47 counties. The governor is directly elected and is the highest elected official in the county. Each county has its own county assembly with members of the county Assembly (MCAs) as representatives. The administrative structure of the national government at the county level includes county commissioners, who are under the ministry of interior, and oversees all national government functions, including security, in the county. Under the county commissioner are deputy commissioners, who oversee sub counties, chiefs, who oversee locations, and assistant chiefs, who oversee smaller administrative units called sub locations, which comprise of a few villages headed by village cluster heads, also known as Nyumba Kumi cluster heads |

Apart from the inequality between different cities or regions, studies have found that inequalities and poverty levels also exist within city populations.[12] In Nairobi, the percentage of people living below the poverty line is 44 percent, but poverty levels in the upmarket neighborhoods such as Lavington, Karen, Kileleshwa and Runda location is under five percent, while the levels are higher than 70 percent in the informal settlements that are the focus of this research, including as Soweto, Kibera, Mathare, Korogocho and Mukuru Kayaba.[13]

Poverty in Kenya is also more pronounced along gender lines. Kenya’s 2015/16 Integrated Household Survey results show that 30.2 percent of female headed households live below the poverty line compared to 26.0 percent of their male counterparts.[14] In its April 2020 policy brief, the UNDP noted it expected the Covid-19 pandemic to exacerbate these poverty levels, especially among female headed households.[15]

The impact of corruption on poverty levels in Kenya cannot be overlooked. Research by both government and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) show that corruption remains endemic and even President Kenyatta has recognized that corruption is a problem and implored Kenyans to work together to address it.[16] In 2020 Transparency International, the global anti-corruption watchdog, ranked Kenya at 143 out of 180 in its Corruption Perceptions Index, with a slightly improved score of 31 out of 100 the previous year. Kenya’s score fell below a Sub-Saharan Africa average of 32 and a global average of 43 in 2020.[17]

In November 2020, a report of the Director of Public Prosecutions estimated that the country was losing Ksh140 billion (US$1.4 billion) to corruption.[18] Studies have shown that corruption increases poverty by reducing the level and quality of social services available to the poor and causes a reduction in resources allocated to development.[19] According to IMF research, corruption perpetuates an unequal distribution of asset ownership and unequal access to education and other services.[20]

Poverty and Gender in Kenya

Analysis of government reports by Human Rights Watch for this research shows a lack of effective gender indicators across all sectors that would promote planning for gender equality.[21] Nonetheless, available data shows that poverty in Kenya is more pronounced along gender lines. Women tend to be poorer than men and have less access to the capital and assets necessary for livelihoods.[22] Men participate more in the labor force and have more opportunities for formal employment, which has stronger job security protections, and earn more than women.[23]

Data shows that in Kenya, women are more likely to be unemployed, underemployed, underpaid, and seasonal workers. Kenya’s 2015/16 Integrated Household Survey results show that more than a third of households are headed by females.[24] In its April 2020 policy brief, the UNDP noted it expected Covid-19 to exacerbate these poverty levels, especially among female headed households.[25]

Informal Settlements in Nairobi

The growth of the nation’s capital city Nairobi as a regional business hub has been characterized by rural-urban migration, coupled with a generally high birth rate, has resulted in rapid population growth and the expansion of large-scale informal settlements.[26] Nairobi’s population has grown from 510,000 in 1969 to 4.3 million in 2019.[27] According to the 2019 population census, roughly 10 million people are living in informal settlements across Kenya, out of which 2.4 million are in Nairobi, and this is the population that the government ought to target with strong social security policies or broad and inclusive social assistance programs to ensure an adequate standard of living, with or without an emergency.[28]

Nairobi has approximately eight broad belts of informal settlements: Kibera, Mukuru, Korogocho, Mathare, Kangemi, Kawangware, Kahawa Soweto and Dagoretti Waithaka belt.[29] These settlements have been divided into a total of 14 smaller neighborhoods with a total of 158 village clusters.[30]

Residents of informal settlements make up nearly half of Nairobi’s population, yet they are crammed into only 5 percent of Nairobi’s residential areas and just one percent of all the land in Nairobi according to Oxfam.[31] In addition to having high population density, informal settlements lack public services, good governance, and electricity access.[32] Most employed residents work as unskilled laborers, earning around a dollar per day, which is far from insufficient in guaranteeing them and their families adequate food daily or decent shelter.[33]

Most buildings or residential houses in these informal settlements are temporary and dilapidated, with mud walls, corrugated iron roofs and floors made from dirt. Sanitation is poor, and most families share public latrines. Most residents lack running water, medical care, and other basic amenities, and live in small single rooms measuring between 12 feet by 12 feet per family, a clear violation of the right to an adequate standard of living, which should encompass adequate food, clean water, decent shelter and sanitation. [34] From the outset of the Covid-19 pandemic, human rights organizations, as well as government officials, recognized that conditions in informal settlements made residents especially vulnerable to the virus.[35]

Kenya reported its first positive case of the novel coronavirus on March 13, 2020, and as of July 5, 2021, there were 185, 868 confirmed cases nationwide and 3, 675 deaths from Covid-19, according to government data of tested cases.[36] However, these numbers likely vastly underestimate the actual infection rate. In January 2021, a Kenya government policy brief showed that the estimated overall prevalence of coronavirus infections in Nairobi was at 35 percent of its nearly 5 million people, which translates to around 1.75 million people, even though undertesting and under reporting was common in many countries.[37]

According to the policy brief, 60 percent of all reported cases of Covid-19 infection in Nairobi were in informal settlements.[38] With houses barely a meter apart and up to 8 persons per room, social distancing was next to impossible.[39] Inadequate and unreliable water supply and poor sanitation negatively impacted the ability of residents to regularly wash their hands.[40]

Kenya Social Protection Systems and Gaps

Prior to the Covid-19 pandemic, Kenya’s government was in the process of building social protection programs to try to provide social protection to up to 36.1 percent of its population living in poverty. Kenya’s social protection program started in 2007 with financial transfers to the elderly, but was not designed to provide universal social security to all households living below the international poverty line. Over the years this program has expanded to support a lot more older people and other categories of the vulnerable populations today than when it started more than a decade ago. In 2019, Kenya adopted a new social protection policy that seeks to establish basic elements of social protection, including income security for children, persons in active age, older persons, and access to essential maternity and health care.[41]

Social protection in Kenya is structured around three pillars - social assistance, social security (pensions), and health insurance.[42] The social assistance pillar includes the cash transfer programs that predated Covid-19, grouped under the government’s National Safety Net “Inua Jamii” Program (NSNP), which began in 2013.[43] The NSNP pays cash transfers to four categories of beneficiaries: caregivers for orphans and vulnerable children; older persons; persons with severe disabilities; and a category of vulnerable households served by a program called the “Hunger Safety Net Program (HSNP).[44]” Beneficiaries under all NSN programs receive Ksh.4,000 ($37) every two months.[45] This translates to just under Ksh500 ($5) per week, which can barely afford them basic necessities, the bare minimum of an adequate standard of living.

According to the Ministry of Labour and Social Protection, NSN programs were paying 1.3 million people cash transfers in 2018, including 800,000 older persons, 353,000 caregivers for orphans and vulnerable children, and 47,000 people living with disabilities, but this again is far below the numbers the authorities need to support to ensure everyone has an adequate standard of living.[46] The Hunger Safety Net Program was, in 2018, benefitting almost 150,000 households, all in northern Kenya counties of Marsabit, Mandera, Turkana and Wajir.[47] 64 percent of the NSNP’s total beneficiaries were female and 36 percent male.[48] The majority of beneficiaries of the NSNP were, according to a March 2021 UK-government financed report on social protection on Kenya, in rural areas.[49]

Prior to the pandemic, the Kenyan government was working to convert the various programs under the NSNP into a single social register – known as the “Enhanced Social Registry” – that would act as a central database of low income and vulnerable households.[50] This would, the government has argued, provide a central register through which to identify households in need and roll out social protection programs.[51]

Despite the growth of the NSNP, the Kenyan government has acknowledged that its pre-pandemic cash transfer programs, and social protection more widely, were not ambitious or well-resourced enough to reflect the country’s high poverty levels. In 2017, the Kenyan government spent 0.4 percent of gross domestic product (Ksh26 billion) on social protection, which included cash transfers and other forms of social safety nets.[52] Countries in sub-Saharan Africa on average spend 1.5 percent of GDP on social safety nets, according to a 2018 World Bank report.[53] A July 2020 Ministry of Labor and Social Protection report concluded that:

Although the Kenya’s social protection programs have reached a great proportion of the poor population, statistics reveal that 36.5 percent of Kenyans still live below the poverty line that means a large proportion of eligible households remain uncovered by any form of social protection…. Studies indicate that the impacts of social protection programs are yet to have a significant impact on poverty. There is a need for the authorities to carry out a needs assessment, compile a list of all vulnerable households across Kenya and thus work towards increasing investments in all social protection programs in health, social security, child grants and economic inclusion to ensure all vulnerable households are covered and guaranteed basic social security.”[54]

II. Disproportionate Impact of Covid-19 and Related Restrictions on Nairobi’s Informal Settlements

Kenyan authorities have not made public any data on the socio-economic impact of Covid-19 and the measures to control its spread have had on the over 4.2 million people in informal settlements across Kenya, including the 2.4 million currently in informal settlements in Nairobi alone, and the level of support required to guarantee each households an adequate standard of living, with or without the pandemic. International human rights groups such as Human Rights Watch, and institutions like the UNDP, have conducted research on the impact of Covid-19 on the most vulnerable families in Nairobi’s informal settlements, which is part of the population that the government’s cash transfer program sought to cushion.

Conditions in informal housing leave residents at higher risk of infection, putting added pressure on already scarce resources and thus further undermine the quality of life they are able to afford in either the absence of or limited government support. Housing in informal settlements is unplanned and residential houses are built close to each other. High population densities and a large number of people in each household made it difficult for residents to adhere to virus control measures such as social distancing.[55]

Many residents told Human Rights Watch they could not afford to adhere to stay-at-home measures because they are dependent on casual day jobs.[56] Despite continuing to leave home to earn what living they can, residents described extreme economic hardship. Many said they lost their jobs or earnings, or were forced to shut down their businesses, and many struggled to make ends meet after they missed out on government support. Compounding these financial struggles, many residents also needed to care for family members who contracted Covid-19 or other illnesses and pay funeral costs whenever loved ones passed away.[57]

Currently, with no state guarantees of the right to health, four out of every five Kenyans have no access to medical insurance and that among the poorest quintile, only 3 percent have health insurance with disparities between rural and urban populations, where rates of coverage are an average of 12 percent and 27 percent respectively.[58]

The UNDP found that the pandemic could become another source of impoverishment and reinforce existing inequalities, in turn limiting the ability of vulnerable households to escape from poverty.[59]

Government’s Public Health Response

On March 15, 2020, President Kenyatta announced the closure of all schools and colleges in an effort to curb the spread of the virus, affecting more than 12 million students.[60] On March 22, the health cabinet secretary, Mutahi Kagwe, banned international flights in and out of Kenya, except for cargo flights, and announced a mandatory 14-day quarantine for all incoming travelers and those who may had contact with them. People interviewed described poor conditions of the quarantine facilities, including lack of bedding, water, food, and cleaning supplies, including soaps and detergents.

They said they were not told of test results and that staff did not adhere to the government’s own protocols, such as wearing face masks or other protective equipment, to ensure that those quarantined do not become exposed to the virus. However, the authorities did little to prepare facilities and staff on how to handle those in quarantine.[61] On March 27, the government imposed a nationwide dusk-to-dawn curfew, which remained in place at time of writing, with the authorities only reviewing curfew start and end times each month.[62]

A year later, on March 26, 2021, in the face of a rapid increase in the number of coronavirus cases, President Kenyatta tightened control measures that had been slightly relaxed, bringing forward the curfew starting time to 8p.m. from 10p.m. In the early days of the pandemic in 2020, police enforced the curfew in a chaotic and violent manner. In downtown Nairobi and in the coastal city of Mombasa, police arrested people on the streets, and herded them together while transporting them to the police stations, increasing the risks of spreading the virus.[63]

Witnesses told Human Rights Watch that in the Embakasi area of eastern Nairobi, police officers in March 2020 forced a group of people walking home from work to kneel, then whipped and kicked them. The authorities implemented these measures even more haphazardly, with indefinite and arbitrary extensions of the quarantine durations causing anxiety in those quarantined, ranging from fear of losing their jobs or delay in seeing

loved ones.[64]

Impact on Informal Settlements

In 2019, the KNBS estimated unemployment rate at 7.27 percent among youth aged between 20 – 24 years.[65] The agency estimated that the formal sector only generates enough jobs to absorb around 20 percent of young people newly entering the labor force, leaving the remaining 80 percent to find work in the informal sector.[66] Most of the youth and other residents of informal settlements fall into the category of the unemployed youth.[67]

In informal settlements such as Mukuru Kayaba, Kibera, Kayole and Soweto, government officials told Human Rights Watch that more than 60 percent of businesses in those informal settlements, which could also be a reflection of the situation in other settlements, had closed during the partial lockdown, which was imposed in Nairobi and a few other counties between April and July 2020 and again in April 2021, exposing tens of thousands of families to severe economic hardships.[68]

Soon after the partial lockdown was first imposed, on May 23, 2020, President Kenyatta announced that the government had set aside Ksh3 billion ($30 million) for provide credit facility to small businesses to cushion them against the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic, yet, according to the government officials working in informal settlements, none of the businesses located there benefited from government support.[69] At time of writing, there was no evidence that the authorities tried to assess the needs of small businesses or had provided credit facilities to the small businesses, including those in informal settlements.

With Kenya lacking a social security program that allows for payment of those who lose jobs, residents of informal settlements described to Human Rights Watch the catastrophic impact of losing their livelihoods since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic. Many families recounted how they have been going for full days without meals, in some instances for as many as four days a week. Many also said that they accumulated rent arrears of up to nine months.[70] Others said the heads of some households abandoned their families – spouses and children – in the city altogether and returned to their upcountry homes.[71]

A 75-year-old woman from Kayaba, who was a grandmother, told Human Rights Watch:

“I live with my late daughter’s six children, two of whom have mental health conditions. When the lockdown came, my small-scale detergents sales business became difficult. I was not able to continue buying medication – at Kshs.100 ($1) per tablet – for my grandchildren. I tried borrowing money from friends, but they were also not doing well. Food was difficult to get. I was borrowing food, begging, and buying food items on credit, which I am yet to pay.”[72]

Another resident of Kayaba, a 39-year-old mother of four said:

“It was very tough for me during the lockdown. My laundry work stopped because people stopped giving us clothes to wash. They were afraid we would infect them with the virus. At home, we would have just one meal a day, and at some point, we started going without food.”[73]

In April 2020, the UNDP noted that workers in the informal economy may not be able to stay at home when they are sick because they do not have paid sick leave as part of the government’s response to Covid-19.[74] People living below the poverty line often lack savings or enough income to stockpile food. And, as the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) in Nairobi noted, malnutrition, and other forms of diseases place somebody at higher risk of severe outcomes from Covid-19 pandemic.[75]

In Soweto Muthaiga, a 28-year-old mother of two said that the effect of the lockdown has lingered even after the government relaxed the measures:

“I used to make around Ksh.200 or Ksh.300 ($3) from washing clothes for people. During the pandemic related restrictions, bans on travel or intercounty movement, work became very difficult to come by. Several times I went a whole day without food. My young children would cry a lot when we went without food. My work has not really picked up since then so we still go without food to this day.”[76]

A 28-year-old woman living in Kayaba told Human Rights Watch:

“I am unemployed with three children aged between nine and one year old. The youngest has sickle cell anemia [a blood cell disorder that increases the risk of severe outcomes from Covid-19].[77] We have to buy his medication on weekly basis. My husband’s job has been on and off since Covid-19 started. This has really affected us. My biggest problem is my child’s sickness. I do not even need money. I can go hungry. All I need is treatment for my child.”[78]

Another resident of the community, a 33-year-old street vendor and mother of two said, “I fell ill early this year before the corona virus pandemic, and I am still unwell. I stopped selling in April when I was admitted in hospital and I am still on medication. My condition coupled with challenges brought about by coronavirus restrictions has made life

very difficult.”

Nearly all the interviewed residents, including those who benefited from the government’s cash transfer program, felt that the government had not done enough to lessen the economic impact of Covid-19.[79]

In Mukuru Kayaba, a 29-year-old mother of three, including one born with a brain condition that she said requires regular medical attention, said she never received government support despite authorities’ promise to include families who have members with underlying health conditions in the cash transfer program.[80]

In Soweto, Kayole, a 32-year-old mother of a 4-year-old boy born with a neurological condition, which she said requires surgery also said she did not get any support from the cash transfer program even though she presented her name for registration and government officials knew about her child’s health.[81] In Kibera, a 42-year-old mother of six said the Ksh1,000 ($10) she received four times after every two weeks was not even enough for food for one day and her family went without food for many days each week

in 2020.[82]

Some of the government’s containment measures introduced new financial demands on families that were already strained by either loss of jobs or collapse of businesses. On April 3, the authorities made it mandatory for everyone to wear masks in public places, a policy that remains in place to-date, and introduced mandatory quarantine in government assigned facilities, at their own expense, as penalty for not wearing masks or breaching the curfew. Those who did not wear masks or were unable get home before the curfew became more susceptible to arrests or beatings by police.[83]

III. Responses to the Economic Impact of Covid-19

Like many of the government’s social security initiatives that existed prior to the pandemic, the Covid-19 cash transfer program was not designed to ensure everyone is guaranteed an adequate standard of living. The president launched the Covid-19 cash transfer program in a public address on March 25, 2020, which introduced a range of measures to cushion Kenyans from the economic impact of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Although president noted the “anxiety that this pandemic has caused millions of Kenyan families, and the possibility of job losses or loss of other sources of income weighing heavily on their minds, the criteria for selecting beneficiaries of the cash transfer program did not include lose of jobs as a necessary condition for which one in any way qualifies for the support.”[84]

In addition to tax reductions for individuals and businesses, Kenyatta promised to appropriate an additional Ksh10 billion ($100 million) for cash transfers by the Ministry of Labor and Social Protection “to the older people, orphans, people with underlying health conditions and other vulnerable members of our society through cash transfers…to cushion them from the adverse economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.”[85]

The government subsequently disbursed cash transfer payments under the preexisting “Inua Jamii” National Safety Net Project, and through a new program, called the Covid-19 cash transfers, which is the focus of this report. By May 23, 2020, when President Kenyatta announced what he described as a Covid-19 – related economic stimulus package, he said the government was already sending out Ksh250 million ($2.5 million) to the most vulnerable households per week.[86]

Inua Jamii Cash Transfers

Payments during the pandemic under “Inua Jamii” National Safety Net Project were made to beneficiaries already registered with the program, with a government official stating on April 27 that 1,094,323 beneficiaries would receive Ksh.4,000 ($37) for the months of May and June.[87] A UK-government funded report subsequently found that in late April 2020 beneficiaries received Ksh.8,000 ($75) to cover the period January to April 2020 (covering two payment cycles as the payment in February had been missed), and a second tranche of Ksh.4,000 ($37) the end of June to cover May and June 2020.

Later in the pandemic, a European Union-funded consortium, led by the Kenyan Red Cross Society and Oxfam, provided cash “top-ups” of Ksh.5,558 ($52) for three months to 1,966 beneficiaries of Inua Jamii programs residing in informal settlements in Nairobi and Mombasa. A November 2020 Oxfam report stated that the top-up program reflected the fact that the Ksh.2000 ($19) per month covers an estimated 14 percent of the monthly basic needs of a family of four in Nairobi’s informal settlement.[88]

Kazi Mtaani Jobs Program

In addition to this, President Kenyatta on May 23 said that government would spend K10 billion ($100 million) on the Kazi Mtaani program through which the authorities provide menial jobs, such as cleaning sewers, garbage collection, and road sweeping, to over 200,000 youths across Kenya, to cushion young people from the economic impact of Covid-19 pandemic.[89] The program targeted mainly those who did not benefit from the Covid-19 cash transfers.

On October 12, 2020, the Nairobi County Commissioner Fiona Mworoa told Human Rights Watch that “For Kazi Mtaani, we have 55,000 young people employed in Nairobi alone. The pilot program had 12,000, but the second phase had a total of 55,524 people employed.”[90] Human Rights Watch found that the authorities are paying the youth Ksh5,000 ($50) for 11 days of work per month.[91]

The government’s Covid-19 economic stimulus measures covered other broad areas like infrastructure, education, health, agriculture, hotels, tourism, and manufacturing. President Kenyatta also said that another Ksh10 billion ($100 million) had been set aside for Value Added Tax (VAT) refunds and Ksh3 billion ($30 million) as affordable credit for small and medium enterprises (SMEs).[92] Again, the president did not provide details about how the fund will be administered and how intended beneficiaries could access it.

Human Rights Watch found no evidence that any of the businesses in informal settlements, which were some of the hardest hit by the government’s Covid-19 response measures, had benefited from the SMEs fund.[93] The government administrators in the informal settlements told Human Rights Watch that no business in their areas of jurisdiction received any support. One administrator said: “It [the support] would have come through my office, which means there is no way it can happen without my knowledge. I did not see anything.”[94]

The Pandemic-Related Cash Transfer Program

The Kenyan government, as part of its response to the economic impact of Covid-19, implemented a new cash transfer program to specifically cushion the most vulnerable households against the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic, between April and November 2020, which mostly covered the first phase of Covid-19 containment measures.

The second phase of containment measures, which included travel bans in and out of five most affected counties such as the capital Nairobi, closing of all restaurants and bars, and dusk to dawn curfews, followed a spike in coronavirus infections in March 2021. The government’s pandemic relief measures did not extend to this second phase, some of which remain in place to-date. Instead, President Kenyatta announced new far reaching tax measures, including taxation on food stuffs, any new credit facilities issued by banks and powdered milk for children, among others, that could exacerbate the impact of Covid-19 pandemic, including on households that were already vulnerable and further undermine their right to an adequate standard of living, including access to food.

As for the first phase, the Covid-19 cash transfer involved weekly payments of Ksh.1,000 ($9), which was insufficient and could not ensure an adequate standard of living for the families, targeted at households not already enrolled in the Inua Jamii program, initially aiming to reach a total of 669,000 households through the mobile money platform M-Pesa, but in the end managed just half that number.[95]

In a letter to Human Rights Watch on January 19, 2021, the Cabinet Secretary for Treasury and Planning, Ukur K. Yatani, outlined the structure of the pandemic - related cash transfer program.[96]

Yatani said the authorities focused on households with a high poverty index in informal settlements. He listed six criteria used by authorities to target specific households: poor households where the head or breadwinner had a physical disability; or was widowed; or is a minor (orphans or child-headed households); have pre-existing medical conditions such as cancer or HIV; has a psychosocial disability [mental health condition] or households not benefiting from other government support.[97]

Yatani further explained that elders heading what is known as the Nyumba Kumi villages, which basically comprise of clusters of 10 households each, and are supervised by government chiefs in informal settlements, helped identify the most vulnerable families in their clusters. Although Yatani said the authorities established multi-agency committees at village, subcounty and county levels to validate and verify “data of the targeted population to ensure equity,” Human Rights Watch found little evidence of a clear system of data verification.[98] Furthermore, Human Rights Watch research showed that the reality in the informal settlements did not correlate with the cabinet minister’s claims that there was a clear system of verification and validation of data of beneficiaries.[99]

Yatani noted that the program, which started on April 22 and ended on November 27,2020, was implemented in two phases. Phase one targeted 85,300 households in four counties — Nairobi, Mombasa, Kilifi and Kwale – that the authorities had locked down, banning any travel in and out of those counties between April and July 2021. In October 2020, Nairobi county commissioner, Mworoa, told Human Rights Watch that 29,000 of the households listed during the first phase were from informal settlements in Nairobi county.[100]

This amounts to approximately 4.8 percent of households in Nairobi’s informal settlements. The estimated eight informal settlements in Nairobi, according to Slum Dwellers International (SIDNET),[i] have over 600,000 households, all of whom were in dire need of support.[101]

In the second phase, according to Yatani, the authorities listed an additional 247,900 households from another 17 counties, which means the program was implemented in a total of 21 of Kenya’s 47 counties.[102] The cabinet secretary did not name the 17 counties or how they were selected, but stated that “a total of 332,563 household beneficiaries have been reached with each having received Ksh1,000 ($10) per week through Safaricom’s MPESA service.”[103]

He further said that as of November 27, 2020, the authorities had disbursed Ksh9.3 billion ($93.3 million), which is “99.86 percent of the Ksh9,340,270,000 ($93,402,700) total amount allocated. Efforts are being made to seek more funding for additional 2 months to cushion the vulnerable population.”[104]

Private and International Donor Interventions

Kenyan authorities have insisted that the pandemic-related cash transfer program was fully funded by the government,[105] despite having received significant support from external partners to bolster its emergency response to the coronavirus pandemic. A loan from the African Development Bank (AfDB) explicitly included support for the cash transfer program as a goal.[106]

AfDB, through its emergency lending program, supported many African countries, including Kenya, to cope with the economic hardship of the pandemic.[107] In May 2020, the AfDB approved a Ksh24.716 billion (188 million euros) loan to the government of Kenya to support its “efforts to respond to the Covid-19 pandemic and to mitigate its economic and social impacts.”[108] This includes enhancing existing social protection through a cash transfer program for the older people, orphans, and people with disabilities, as well as extending protections to “new categories of people who have become vulnerable due to Covid-19.”

According to the AfDB project document, Kenya’s existing cash transfer program, which has been in place for over a decade, benefited 1.3 million people, mostly the older people, orphans and people with disabilities, and that an “additional 4 million will require social assistance due to the impact of Covid-19 crisis.” The bank commended the government’s appropriation of an additional Ksh 10 billion (about $94.3 million) to provide a “one-off transfer equivalent of $40 each to 3 million beneficiaries,” as well as “expand coverage of social protection to new vulnerable populations such as urban poor and informal sector workers, including providing weekly stipend to needy households in Nairobi,” among other measures.

Kenya also received the IMF’s emergency lending to help countries cope with the economic hardship of the pandemic. In May, the IMF approved a Ksh7.39 billion ($739 million) loan to Kenya under the Rapid Credit Facility (RCF) to support its response to the Covid-19 pandemic, including “cash transfers to orphans, the older people, and the most vulnerable.”[109] In its Letter of Intent requesting assistance from the IMF, the Kenyan government said it was “strongly committed to ensuring effective and transparent use of public funds,” and pledged to strengthen its capacity to “detect illicit enrichment and to address conflict of interest” and to “conduct independent post-crisis auditing of Covid-19 related expenditures and publish the results.”

In addition to the national government’s pandemic -related cash transfer program, local county governments, nongovernmental organizations and private individuals also introduced initiatives to help alleviate the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic to the vulnerable, but these efforts remained poorly coordinated.[110] In Mombasa, businesspeople, alongside the county government of Mombasa, distributed food supplies to the vulnerable families in the coastal town.[111]

In July, the World Food Program (WFP) launched an independent cash transfer program to supplement the government program.[112] A WFP staff told Human Rights Watch that its program had supported 70,500 households in Nairobi and 24,000 in Mombasa who missed out on the government program with Ksh4,000 (US$40) a month for three months”.[113]

GiveDirectly, an international nongovernmental organization operating in different regions and continents, including East Africa, also implemented an independent cash transfer program under which beneficiaries received Ksh3,000 ($30) per month for three months to supplement the government’s Covid-19 cash transfer program.[114]

However, none of these measures by donors or civil society groups on the one hand and Kenyan government on the other, appear designed to guarantee the right of everyone to social security and an adequate standard of living. Just like the government’s initiative, some of the initiatives by donors and civil society groups appeared designed more as charities that targeted an even smaller fraction of beneficiaries without any clarity on how the many other households that faced hunger in informal settlements were left out.

IV. Cash Transfer Program Irregularities

Human Rights Watch found that, from the onset of government’s measures to contain the spread of coronavirus from March 2020, which has been followed by monthly reviews of the measures, Kenyan authorities were slow to respond to the unique needs of the informal settlements and, when they did respond, it was haphazard, skewed, short – lived, inadequate and did not appear designed to enforce the right to social security and to an adequate standard of living for all, including food.[115] The stay-at-home measures, for instance, predictably led to the loss of jobs, shut down of businesses and other sources of income for a large percentage of residents, yet the government did not provide any initial support to cushion the blow.[116]

When authorities did finally implement an eight-month pandemic-related cash transfer program, it was not only a short–lived transfer of insufficient funds but also lacked even basic transparency, and provided no clarity on who was eligible, how beneficiaries were identified, or why thousands of households who met the approved criteria were excluded.[117] It was also replete with irregularities and allegations of cronyism and corruption.

General Lack of Transparency

From the outset, and through every stage of its implementation, Human Rights Watch found that the Covid-19 cash transfer process lacked even basic transparency.[118] Other than President Kenyatta’s mention of the plan for pandemic - related cash transfers in a public address on May 23, the authorities offered little to no information about the program implementation: when it would start, the intended beneficiaries and how they would be selected or who would be responsible for selecting beneficiaries.[119]