Summary

My father was very violent with me, and my mother treated me differently from my siblings. I thought that by getting married I’d escape my family’s violence. But it only got worse. My husband started beating me on our wedding night. I had my period and did not want to have sex, but he wouldn’t accept it. He hit me, held me down, and forced me to do things. He calls me a worthless whore all the time. In bed, he forces me to do things that make me so ashamed I cannot pray and face God for days. I clean every inch of our house but he always finds a reason to beat me.

I didn’t want to complain, but in March 2021, he hit me on the head with a brick. He said he could see the devil in me and that he wanted to destroy me. I had no choice but to complain. I got a medical certificate from the hospital that prescribed seven days of rest. I went to the police to show them the certificate and the death threats that my husband had sent me on WhatsApp. But after my husband spoke with them, the police dissuaded me from filing a complaint. The following day, I went to court to file a complaint there. Meanwhile, my husband apologized, and I dropped the complaint.

He became more violent. In September 2021, I went to a different police station to ask for a protection order. They refused to help me, so I went to court. When they refused to help me too, I opened the window to jump off the tribunal’s second floor. Someone held me back.

I know my husband won’t change. He tells me he isn’t scared of the police. He knows I won’t try to complain anymore because I have no money and nobody to support me. If I did put him in jail, what would happen to me? Who else will look after me? How will I survive with two kids on [his post-divorce financial support] of 250 dinars (US$80) a month? My family doesn’t want to take me and my children in. If I didn’t have kids, I would just live on the street. I’ve called shelters but they rarely answer the phone and when they do, they say they can’t take me in. I feel like I am walking to my own grave.

As of September 2022, “Nahla,” a 40-year-old from Ben Arous interviewed by Human Rights Watch, was still living with her husband.[2]

Key Findings

Nahla’s experience reflects how the compounded failures of different authorities can leave women with no alternative than living with an abusive partner, leaving them at risk of abuse and femicide.

Women have reported harrowing experiences of domestic abuse to Human Rights Watch. Men had locked them up; beaten them with objects; threatened to kill them; raped them; forced them to work for them in austere conditions without compensation; deprived them from food while pregnant; confiscated their money; abandoned their household; or verbally humiliated them, daily, at times in public.

During 2021, the police registered nearly 69,000 complaints of violence against women and girls.[3] The most recent national survey on violence against women, published in 2010, reported that half of Tunisian women had experienced at least one form of violence in their lives.[4] The real magnitude of domestic violence is however difficult to gauge, in part due to poor data collection and the social and economic pressure on women to tolerate

men’s violence.[5]

This report examines Tunisian authorities’ response to domestic violence, five years after the adoption of Law 2017-58 on the Elimination of Violence Against Women (hereafter Law-58), one of the most progressive legal framework aiming to eliminate physical, moral, sexual, economic, and political forms of violence against women in the Middle East and North Africa.

Law-58 has introduced progressive prevention, protection, and prosecution provisions, and assured survivors’ access to appropriate services. It introduced unprecedented protection measures and orders aimed at keeping abusers away from the spousal domicile and survivors. It toughened sentences for some crimes where the abuser is a family member or (ex-)spouse/fiancé and introduced new crimes relating to economic and psychological violence. The law also abrogated provisions that had allowed for the termination of proceedings or the quashing of convictions if a survivor withdrew her complaint; and provisions that had allowed for impunity or lenient punishment of abusers such as provisions that exempted a rapist from punishment if he married the survivor.

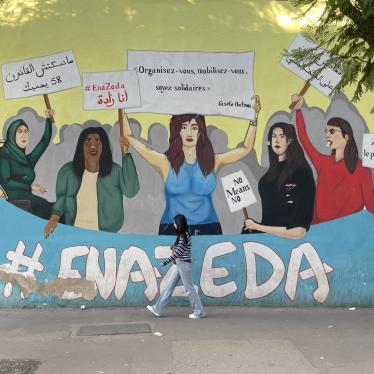

The adoption of Law-58 appears to have marked a distinct shift in public awareness of violence against women in Tunisia. The 2019 #EnaZeda (#MeToo) movement and the public communications around the five-fold increase in reporting of violence against women under Covid-19 lockdowns in Tunisia, likely also contributed to this change.

Overall, the report finds that, despite considerable legislative and institutional progress, and the genuine commitment of individual state officials and service providers to assist survivors, the insufficient allocation of financial means toward Law-58’s implementation problematic attitudes among the police and judiciary have has led to inconsistencies and failures in the state’s response to domestic violence. Ultimately, a woman’s ability to exercise the rights granted to her by Law-58 is contingent on the will of service-providers addressing her complaint; the proximity of savvy nongovernmental organizations to accompany her; and her individual characteristics and persistence.

Tunisia’s 2022 constitution guarantees equality of women and men before the law, and Law-58 obligates the state to adopt measures to prevent violence against women including to take every necessary measure to eliminate all discriminatory practices against women.[6] However, women continue to face discrimination in law and practice that can leave them vulnerable to violence. Moreover, some of Tunisia’s Constitutional provisions could be used to limit women’s rights based on interpretations of religious precept.

The Ministry of Women in its 2020 report remarked that discriminatory codes and laws against women hindered the implementation of Law-58.

Tunisia’s 1956 Personal Status Law, adopted shortly after its independence from France, was historic in how progressive it was in advancing women’s rights compared to countries across the region as well as France and other European countries. However, discriminatory provisions that remain – for instance deeming men as heads of households, language that can suggest an obligation on spouses to conform to stereotypical gender roles, and discriminatory inheritance provisions – leave women more exposed to violence. Moreover, public morality laws and the criminalization of same-sex relations under Article 230 of the penal code may deter lesbian, bisexual, or transgender women (hereafter LBT women), as well as women abused by partners to whom they are not engaged or married, from reporting domestic violence to authorities to avoid risks of facing prosecution instead of receiving protection or justice.

State policies reinforce women’s role as providing unpaid domestic care, and leave women financially dependent on men, contributing to their exposure to male violence against women, which comes with significant social, economic, and developmental costs for

the state.

Law-58 also directed ministries and state institutions to prevent and combat violence against women including through education, training, detection, awareness raising, and providing information, care, and ongoing support to survivors.

However, efforts to inform women of their rights and the services available to them are deficient, especially among rural and illiterate populations. Street signage and banners indicating the location of support services and Law-58’s key provisions in strategic venues are rare. The detrimental impact of weak public communication efforts is compounded by the failure of overwhelmed, under-trained, or negligent frontline respondents to clearly inform women of their rights to protection orders, legal aid, shelter, and other support.

In a positive move, only six months into the law’s implementation, the Ministry of Interior established 128 specialized units across the country for the elimination of violence against women dedicated to the investigation of cases of violence against women, as the law required. However, the specialized units are only operational during administrative hours and not all units guarantee privacy or include female staff to interview complainants. Problematic attitudes and practices in the response by specialized units and regular police officers to domestic violence persist. They include lack of communication of survivors’ rights, dismissive attitudes, and continued recourse to pledges or family mediation that force women to reconcile with their abusers rather than informing them of their rights to protection under the law. Mechanisms to identify risks of femicide requiring immediate protection have not been rolled out throughout the country.

Law-58 provides for temporary protection measures that the police can request from prosecutors at the survivor’s request, as well as longer-term protection orders that courts can issue without the survivor needing to file a criminal complaint or divorce. This permits authorities to forbid alleged abusers from approaching survivors and their children, while allowing survivors to remain safely in their homes while they decide on their next steps. UN Women describes protection orders as “among the most effective legal remedies available to complainants/survivors of violence against women.”[7] However, lack of available data on the number of protection measures or protection orders issued prevents an accurate assessment of their use and impact.

One of the biggest barriers that six women complained about is that police insisted on arbitrary evidentiary requirements – namely, recent medical certificates – to launch investigations or provide protection measures, even though Law-58 does not require this. Women reported differing time limits that police considered to be valid for medical certificates, sometimes as little as 48 hours, in order to take action. Such requirements deprive women from protection as authorities may turn them away if their medical certificates are deemed too old, ultimately exposing them to further risks of violence. Survivors often need time until they decide whether or not they want to complain against their abusers.

“Ahlem,” 26, from Sidi Bouzid, who was beaten, humiliated, and forced to work without compensation for seven years by her husband, said the police had turned her down when she had decided to file a complaint against him in August 2021:

When I got to the police station, the police told me I could not do anything with my [four] medical certificates [issued in 2020 and 2021] because all of them had been issued more than 15 days ago. I felt so discouraged. I am illiterate and no one had told me my certificates would lose their validity after a couple of weeks. Why aren’t women allowed to keep them as weapons under their pillows to use once they are ready to fight back? [8]

Law-58 provided for survivors’ right to medical, psychological, and social support and follow-up. However, in most regions, only medical certificates have been issued free of charge to survivors of domestic violence, and some women have reported having had to pay for medical certificates. [9] Fees for additional medical examinations, along with transportation costs, can have a dissuasive effect on survivors. In 2022, the Ministry of Women and the Ministry of Health issued a ministerial note (n°5-2022) to address this gap in implementation and reaffirm survivors’ right to free initial medical certificates and to flexible payment schemes for other medical expenses.[10] Overstretched medical staff rarely inform survivors of their rights or refer them to psychologists or other support services. The police and judiciary overly rely on medical certificates to launch an investigation or in conviction, and yet access to forensic expertise is limited in most of the country. Due to the lack of forensic doctors, the prevailing practice is for general physicians to examine complainants of domestic violence, yet both general physicians and forensic doctors lack guidelines on how to determine physical incapacitation in domestic violence cases. In 2020, the only public counseling center in Tunisia dedicated to survivors’ psychological wellbeing closed due to lack of funding.

Law-58 significantly broadened the scope of criminal law to combat male violence against women in its physical, moral, sexual, economic, and political forms, and set out free support services for survivors. However, the judiciary’s response to domestic violence has been characterized by lengthy proceedings, alleged reluctance of some family judges to implement the law, failure to investigate withdrawn complaints, and the complainants facing challenges accessing provision of free legal aid or had ineffective legal assistance. During the first weeks of Covid-19 lockdowns in 2020, the Ministry of Justice failed to prioritize cases of domestic violence.

Shelters for survivors are essential to an effective response to domestic violence. Law-58 set out that survivors have a right to emergency shelter, but did not specify the number of shelter spaces to be made available or their funding mechanism. Without enough shelters, organizations and state institutions have nowhere to refer women to. The number of operational shelters for survivors has fluctuated since the law’s adoption, especially outside of the capital, and remains insufficient. In 2021, only five shelters, with a cumulative hosting capacity of approximately 107 women and children, were operational - only one of which was outside of the governorate of Tunis. In a positive move, in the summer of 2022, the Ministry of Women and its international partners supported the opening of five additional shelters.[11] At time of writing, the total hosting capacity of shelters across the country is estimated at 186 women and children, based on Human Rights Watch’s mapping of available shelters.[12] The Ministry of Women plans to open more shelters to ensure at least one shelter is operational in each of Tunisia’s 24 governorates by 2024.[13]

Survivors and service providers who spoke to Human Rights Watch pointed to the lack of financial aid as the biggest impediment to women breaking free from their abusers, especially for those with children. Law-58 guarantees integration and housing services to survivors of violence and their children, as such the state should set out timely financial assistance to meet women’s needs and assistance in finding them long-term accommodation.

While Law-58 paved the way for the establishment of a National Observatory for the Elimination of Violence Against Women in 2020, the observatory has not provided since its creation sufficient data on male violence against women or on authorities’ interventions to protect survivors and prosecute abusers.

Law-58 is one of the strongest laws on violence against women in the region. It contains many important legal measures to prevent violence against women, protect survivors, and prosecute abusers. However, as this report finds, poor implementation of the law, along with discriminatory laws and practices, continues to leave women exposed to violence and fails Tunisia’s own obligations under its constitution and domestic and

international legislation.

Despite Tunisia building a reputation of being one of the most progressive states in the region on women's rights during the 66 years since independence, many now fear that such rights are at risk in the political climate instilled since President Kais Saied’s 2021 coup.

To comply with domestic and international law, Tunisia must dedicate effort to the implement Law-58’s ambitious provisions. The state should ensure that: the police protect women and launch investigations whenever domestic abuse is reported, without requiring initial medical certificates; the judiciary duly processes all cases of domestic violence, in all its forms; and promised support services (medical care, legal aid, shelter, and others) are available to survivors throughout the territory.

Ending male violence against women should be prioritized by the entire government and judiciary as a human right, women’s right, and as a public health and economic issue.

Glossary

CEDAW: the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), adopted in 1979 by the United Nations General Assembly, is an international legal instrument that requires countries to eliminate discrimination against women and girls in all areas and promotes women's and girls' equal rights.

Domestic violence: refers to the exertion of physical, psychological, sexual, or economic violence against women by family members and/or (ex)partners.

Family violence: refers to violence committed by fathers, brothers, uncles, in-laws, and other family members, and other relatives.

Femicide: refers to the intentional murder of women because they are women. It is the most severe form of violence against women.

Male Violence against Women: while legislation tends to refer to “violence against women,” violence against women is a male issue. It is the cause and consequence of the patriarchal order that fosters men’s social, economic, and political domination over women. While women, including female relatives, also commit acts of violence against other women, the overwhelming majority of abuses against women are inflicted by men.[1]

Ministry of Women: refers to the Ministry of Family, Women, Children and Seniors.

Survivor(s): refers to women who have experienced physical, psychological, sexual, or economic forms of male violence against them.

Acronyms

ADDCI Association pour le Développement Durable et la Coopération Internationale de Zarzis (Association for Sustainable Development and International Cooperation of Zarzis)

AFC Association Femme et Citoyenneté (Association Women and Citizenship)

ASF Avocats Sans Frontières (Lawyers Without Borders)

ATFD Association Tunisienne des Femmes Démocrates (Tunisian Association of

Democratic Women)

CREDIF Centre de Recherches d'Etudes de Documentation et d'Information sur la Femme (Research Center for Documentation and Information Studies on Women)

CNAV Coalition Nationale Civile pour l'élimination des violences à l'encontre des femmes et des filles (National Civil Coalition for the elimination of violence against women

and girls)

LBT Lesbian, bisexual, and transgender

LGBT Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender

ONFP Office National de la Famille et de la Population (National Office of Family

and Population)

Key Recommendations

To Tunisian Authorities

- Repeal discriminatory provisions in the Personal Status Code to ensure women have the same economic and social rights as men; and repeal Article 230 of the penal code, which criminalizes same-sex relations, as well as morality-related provisions in the Penal Code, to ensure no woman is prosecuted on the basis of her sexual life, sexual orientation, gender identity, or gender expression;

- Issue a decision to instruct police officials and prosecuting authorities not to require medical certificates from survivors before receiving their complaints, launching investigations or providing them with protection measures;

- Ensure doctors include comprehensive observations on the harms inflicted on survivors in initial medical certificates and refer them to psychologists or forensic doctors as required and based on survivors’ consent;

- Ensure the police take all available measures to protect women and investigate cases when they receive complaints of domestic violence, without requiring the provision of an initial medical certificate;

- Develop and institutionalize the use of tools to identify femicide risks requiring immediate intervention among frontline respondents;

- Ensure courts handle domestic violence complaints expeditiously, including in crisis contexts such as lockdowns;

- Ensure sufficient shelters are operational and accessible throughout the territory;

- Ensure women victims of domestic violence have access to support services, including effective free legal aid, competent psychological support, and economic assistance;

- Invest in efforts to increase survivors’ awareness of their rights and of the services available to them;

- Establish complaint mechanisms for survivors to report inadequate responses by public servants and monitor authorities’ implementation of Law-58;

- Improve data collection on male violence against women – including by disaggregating data, monitoring femicides, and providing detailed figures on protection and prosecution measures taken by authorities.

Methodology

Human Rights Watch conducted research between September 2021 and September 2022 on Tunisia’s response to domestic violence, in particular its implementation of Law 58-2017 on the Elimination of Violence Against Women.

Human Rights Watch conducted interviews with 103 people (90 in person, and 13 remotely) in the towns and cities of Al Kef, Ben Arous, Gabes, Mahdia, Sidi Bouzid, Tunis, and Zarzis.

Human Rights Watch conducted in-depth interviews with 30 survivors of domestic violence. These women were all Tunisians and ranged in age from 18 to 44 years old. They included two black women, a lesbian woman, and three transgender women. They came from different social and economic backgrounds, but most were unemployed or underemployed and lived in rural areas rather than in cities. They had different levels of education, but most had completed only primary school education. Human Rights Watch makes no statistical claims based on these interviews on prevalence of domestic violence.

Due to access and scope limitations, this report does not reflect all situations of women including those experiencing other various intersecting discrimination drivers such as being older (defined as those over 60 years old), having a disability, or being a migrant. It also excludes the situation of children.

Human Rights Watch also interviewed 73 other people, including state officials, police officers, staff of governmental and nongovernmental organizations providing services for survivors of domestic violence, gender experts, lawyers, judges, psychologists, journalists, and health personnel.

Human Rights Watch informed all interviewees of the purpose of the interviews, as well as how information collected would be used and received verbal consent. Survivors were also informed of their right to pause or stop the interview at any time, or to withdraw permission to use their statements any time after the interview was conducted. None of the interviewees received monetary or other incentives for speaking with Human Rights Watch. All interviews were conducted in Tunisian Arabic, English, or French.

The report uses pseudonyms — indicated in quotation marks — for 22 survivors and withholds other identifying information to protect their security and privacy. The remaining eight survivors insisted we use their real names.

Human Rights Watch also examined additional laws, government data, medical certificates, surveys, and United Nations documents, academic research, and

media articles.

Human Rights Watch wrote multiple letters, annexed to this report, to the head of government and various ministries in September 2022, requesting information for incorporation into this report and meetings with officials who could discuss relevant policies. At the time of publication, only the Ministry of Health has submitted a response to our letters.

Background

Legal Reforms on Women’s Rights

Tunisia has been a pioneer in the domain of women’s rights.[14] Just six months after independence from France in 1956, the country adopted its Personal Status Code, which criminalized polygamy and provided women with an equal right with men to divorce, marking firsts in the region.[15] The Code also allowed both spouses to divorce by mutual consent without needing to prove fault, which was well ahead of many countries including France, Germany, and the United Kingdom.[16]

In 1973, Tunisia became the first country in the Middle East and North Africa to legalize and provide free abortion on demand for all women within the first three months of pregnancy, earlier than European countries, including France.[17] In 2000, authorities allowed women to enter a work contract without their husband’s authorization and in 2010, allowed Tunisian women to pass nationality to their children on an equal basis with men.[18]

In 2017, Tunisian women were allowed to register their marriage to non-Muslims after authorities rescinded a decree which had prevented such registration.[19] The same year, former President Caid Essebsi appointed an independent commission on individual liberties which, in 2018, made bold recommendations to equalize rights between men and women, including in inheritance, and to decriminalize homosexuality.[20] In November 2018, the Council of Ministers approved a draft law which would have amended the 1956 Code of Personal Status, to provide gender equality in inheritance as the default, but it

remains pending.[21]

Since his 2019 election, President Saied has done little to advance women’s rights. Feminists are concerned he is “gradually destroying” women’s status in Tunisia.[22] Under his power grab beginning on July 25, 2021, parliament has been suspended and then dissolved, making it impossible for parliamentarians to adopt any further legislation that could help in combatting violence against women, such as ratifying the Council of Europe’s Istanbul Convention for action against violence against women and domestic violence.

Saied opposes equality in inheritance.[23] While Saied’s 2021 appointment of a female prime minister, Najla Bouden, is a first in the Arab world, he has granted her little to no political autonomy according to experts who spoke to Human Rights Watch.[24]

Following a controversial referendum that took place on July 25, 2022, President Saied promulgated a new constitution by presidential decree.[25] Retaining some of the 2014 Constitution’s provisions, the 2022 Constitution stipulates women and men are “equal in rights and duties and are equal before the law without any discrimination,” and commits the state to take measures to eliminate violence against women.[26]

However, the 2022 Constitution introduced a new provision stipulating “Tunisia is part of the Islamic Umma [community/nation]” and making the realization of Islamic values a responsibility of the state (Article 5). Such provisions could be used to justify curbs on rights, notably women’s, based on the interpretations of religious precepts, as observed in other states in the region.[27]

Law n°58-2017 on the Elimination of Violence Against Women

After decades of advocacy efforts to adopt a dedicated criminalizing violence against women, Tunisia adopted Organic Law n°58 of 2017 on the Elimination of Violence Against Women (hereafter Law-58), 11 August, 2017, which took effect on February 1, 2018 and constitutes one of the most progressive legal frameworks to combat violence against women in the Maghreb and Mashreq.[28]

The law seeks to put in place measures to eliminate violence based on gender discrimination against women with a view to achieving equality.[29] It has a comprehensive definition of violence against women including in public and in private sphere, and in its physical, moral (i.e. psychological, sexual, economic), and political forms, in line with the UN Women’s Handbook for Legislation on Violence against Women.[30] It also provides for various prevention, protection, and prosecution mechanisms and support services.

Prevention measures include obligations on the state to eliminate all discriminatory practices against women, directing ministries and state institutions to prevent and combat violence against women including through education, training, detection, awareness raising, and providing information, care, and ongoing support to survivors.

Protections for survivors include providing for the rights of survivors and their children to legal protection, equitable reparation, free support services for survivors including access to emergency shelter, legal aid, medical, psychological, and social support, and follow-up.[31] It introduced emergency protection measures and longer-term protection orders in Tunisia, a best practice, according to the UN Handbook on the Elimination of Violence Against Women.[32]

Prosecution measures include establishing new crimes of violence against women in the Penal Code and providing for harsher sentences for abuses committed by family members, spouses, fiancés, as well as former spouses and fiancés – among other aggravating circumstances. It also repealed Penal Code provisions that allowed for impunity or lenient punishments of abusers, including Article 218, which allowed termination of proceedings or conviction if the survivor forgave the abuser, and colonial-era relics Articles 227 bis and 239, which exempted a rapist or a kidnapper from punishment if they subsequently married their victim.[33] It establishes specialized units within every national guard (gendarmerie) and police station to handle crimes of violence against women, obligates the authorities to investigate cases of violence against women, inform and refer survivors to services and protection mechanisms, and sanctions officers who pressure survivors to forgo their rights, modify or withdraw their complaint.

Law-58 called for the establishment of a National Observatory for the Elimination of Violence Against Women (Article 40) to collect data on violence against women and evaluate the effectiveness of laws and policies aimed at combatting it. However, the observatory was only effectively set up in 2020, and its agenda remains unfulfilled. [34] There is limited data on violence against women and on the protection, prosecution and support services delivered to survivors by authorities. The last national survey conducted on domestic violence dates to 2010.[35] According to Monia Kari, who directed the Observatory from July 2020 to December 2021, the body lacked the budget and autonomy to fulfill its mandate and is hampered by the relevant ministries’ insufficient data collection and sharing. [36] The limited monitoring of authorities’ implementation of the law diminishes state accountability. While the Ministry of Women provides data on women who report violence against them, it is limited to a breakdown of their age, relationship to the abuser, employment status, and educational level. This restriction impedes the identification of categories of women who may be at a greater risk of domestic violence and the development of strategies to address their needs.

For all the significant breakthroughs in the law, its impact has been hampered by the fact that no budget or funding mechanism have been put into place toward implementing the law. Organic Law-15 on gender-sensitive budgeting, adopted on February 13, 2019, to support gender equality, does not explicitly include allocation of money toward implementing Law-58.[37]

This report examines how authorities have adhered to the law’s provisions, the gaps that exist and what is needed to ensure that the law’s aim of “eliminating violence based on gender discrimination against women with a view to achieving equality” is realized. While the law commits to address all forms of violence against women, this report specifically examines how the law has been applied to deal with domestic violence.

International Human Rights Obligations

Tunisia’s failure to adequately prevent women from domestic violence, provide protection and services to survivors, and ensure access to justice and prosecution of such violence is contrary to Tunisia’s international human rights obligations.

Tunisia ratified in 1985 the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), which calls on states to take various measures to eliminate all forms of discrimination on the basis of sex, including by private actors, so as to ensure women’s full enjoyment of their human rights.[38] The CEDAW Committee, the UN expert body that monitors implementation of CEDAW, has made clear that gender-based violence is a form of discrimination and is a violation of CEDAW, whether committed by state or private actors, and that a “women’s right to a life free from gender-based violence is indivisible from and interdependent with other human rights, including the right to life, health, liberty and security of the person, the right to equality and equal protection within the family, freedom from torture, cruel, inhumane or degrading treatment, freedom of expression, movement, participation, assembly and association.”[39]

In 2014, the country withdrew all the reservations it had raised to CEDAW and ratified its Optional Protocol (CEDAW-OP), which establishes inquiry mechanisms for groups or individuals seeking to file complaints for “grave or systemic violations” of their CEDAW rights. [40] However, Tunisia has maintained its general declaration indicating it would not adopt any administrative or legislative decision that might go against the provisions of its Constitution. Such declarations have been consistently found to be unacceptable by treaty monitoring bodies, as the application of international human rights treaties should not be limited by domestic laws, including constitutions. In 2020, the CEDAW Committee urged Tunisia to withdraw its general declaration, highlighting the absence of any contradiction in substance between the Convention and Islamic law.[41]

Violence prevents women from enjoying a host of other rights stipulated in other treaties ratified by Tunisia including the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), and the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment.[42] These rights include the rights to life, health, physical integrity, nondiscrimination, an adequate standard of living (including housing), and freedom from cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment

or punishment.

In 2018, Tunisia became a party to the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa (the Maputo Protocol), which requires states to take comprehensive measures and legislation to end violence against women.[43]

Tunisia is also a member of the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia. The Commission’s Committee on Women, in its seventh session in 2016, adopted the Muscat Declaration “Towards the Achievement of Gender Justice in the Arab Region,” requiring parties to “harmonize national legislation with international and regional commitments ratified by member States, so as to ensure the repeal of all discriminatory laws.”[44]

In August 2020, Tunisia’s Ministry of Women initiated the process to adopt the Council of Europe Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence against Women and Domestic Violence, known as the Istanbul Convention, after it was invited in April of that year by the Council of Europe to do so as a non-member state.[45] Tunisia has until 2025 to finalize the accession process.[46] Adopting the Convention would require Tunisia to, among other things, allocate appropriate financial and human resources to the adequate implementation of measures to prevent and combat all forms of violence, including measures carried out by nongovernmental organizations; set up appropriate, easily accessible shelters in sufficient numbers to provide safe accommodation for and to reach out pro-actively to victims; undertake femicide risk assessments; and the inclusion of stalking, forced marriage, forced abortion or forced sterilization in its definition of forms of violence against women.[47]

Failure to Prevent Violence Against Women

Historically unequal power relations between men and women, or patriarchy, manifest in discriminatory laws, policies, and social norms, is the root cause of male violence against women.[48] Out of the 30 women who spoke to Human Rights Watch, most described putting up with violence and self-sacrifice as part of a “good” wife and mother’s role.

General Comment 35 on the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women’s calls on states to:

Adopt and implement effective legislative and other appropriate preventive measures to address the underlying causes of gender-based violence against women, including patriarchal attitudes and stereotypes, inequality in the family and the neglect or denial of women’s civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights, and to promote the empowerment, agency and voices of women.[49]

Law-58 obligates the state to take all necessary measures to eliminate all discriminatory practices against women including in wages and, and sanctions discrimination against women too.[50] However, women continue to face discrimination in law and practice, in violation of Tunisia’s international human rights obligations. This discrimination can increase their vulnerability to violence. The Ministry of Women in its 2020 report remarked that discriminatory codes and laws against women hindered the implementation of Law-58.[51]

Discriminatory Laws

While Tunisia’s 1956 Personal Status Code, and its subsequent amendments, is progressive in many respects, it retains discriminatory provisions such as deeming men as heads of households, requiring marital duties in line with custom and tradition, language that could encourage marital rape, and discriminatory inheritance provisions.

Gendered Roles and Rights

The Personal Status Code requires spouses to “fulfill their marital duties according to customs and traditions.”[52] This ambiguous clause allows for discrimination to continue in practice, as it can be interpreted as an obligation on spouses to conform to stereotypical gender roles that are disproportionately harmful to women.

The Code also specifies that “the husband, as the head of the family, must support his wife and children to the extent of his means” including providing spousal maintenance (nafaqa) to his wife.[53] The same article that elevates men as heads of household because they are required to provide for their wife and children specifies that “a wife must contribute to family expenses if she has possessions.” Even if she does contribute financially, the law does not accord her the status of sole or joint head of household.

As the legally recognized heads of households, husbands are the primary recipients of state health care and social assistance to which the family is entitled under the Social Security Law 60-30.[54] Unless they are in the process of divorce, or are divorced or widowed, women are not systematically eligible for these benefits.[55] This leaves married women economically dependent on their husbands, which can act as a barrier to leaving

abusive spouses.

This differentiation reinforces gendered roles in which men are expected to work while women remain at home. It also facilitates discrimination against women in the labor market, as employers may be more likely to employ men who are considered by law as heads of household.[56] In addition, by recognizing men as heads of households based on providing financially for the family, it downplays the crucial role of providing care within the family, which in practice is left largely to women.

Marital Rape

In 2010, the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women expressed its concern at the results of 2004 national surveys that found that male spouses had sexually assaulted 20 to 40 percent of Tunisian women.[57]

While the Penal Code considers rape a grave crime, marital rape is not explicitly criminalized in the Penal Code or Law-58’s definition of sexual violence.[58] Law-58, however, broadly defines sexual violence “whatever the relationship between the perpetrator and the victim,” suggesting that crimes of sexual violence should apply even in cases of marriage.[59] According to judge Faten Sebei, some investigative judges have used Law-58 to refer cases of marital rape to trial but, so far, no judgments have yet passed

in such cases.[60]

Language in the Personal Status Code can allow for or encourage sexual violence in marriage, including marital rape. Some women may also not report sexual violence because they may believe that they owe sex to their husbands. Article 13 of the Personal Status Code states that men may not force their wives to consummate the marriage without providing the mahr (dowry) to her first. This suggests that by providing a dowry, a husband can force a woman to consummate the marriage. The code says nothing more about a spouse’s freedom to engage, or not to engage, in sexual relations with their partner. Moreover, the obligation under Article 23 to fulfill their marital duties in accordance with “customs and traditions” leaves open the possible interpretation that a wife is not entitled to refuse sexual relations and therefore has no legal basis to file a criminal complaint against him for sexual assault.

“Sana,” 31, from Zarzis, who says her husband had hit her and stolen from her from 2020 to 2021 before she obtained a protection order against him, commented:

In the summer of 2021, I told my husband I wouldn’t have sex with him unless he got tested for sexually transmissible diseases, because I knew he’d been cheating on me. A few days later, he asked me if I wanted an uncontested divorce and I refused. […] He told me I was depriving him of his legal right to sex and failing in my spousal duties. I got scared and preferred to end the conversation there. I went to bed feeling

defeated, crying.[61]

Unequal Inheritance

Based on interpretations of Islamic law, the Personal Status Law stipulates that sons inherit twice the sum daughters inherit from parents or siblings. The denial of women’s right to equal inheritance fuels gender inequality and violence by placing them in a position of social, economic, and symbolic dependence on men.[62]

Public Morality Laws

Law-58, which increases sentences for some crimes depending on who the perpetrator is, refers to some people in intimate or formerly intimate relationships: husbands, ex-husbands, fiancés, and former fiancés. While this is important, by not referring to “partners” or ex partners more generally, the law creates ambiguity around whether women can seek protection when they are neither married nor engaged to their

abusive partners.

Moreover, unmarried women may be dissuaded from turning to the authorities when they face abuse by men in intimate relationships for fear of facing punishment under other laws. While Tunisia does not criminalize nonmarital heterosexual relationships, some unmarried couples have faced arrests and been convicted under accusations of engaging in a “customary” marriage or in “prostitution.”[63] They could also face punishment under the Penal Code for “offenses against good morals or public mores,” and “public indecency.”[64] Adultery is also a crime, for both partners involved.[65]

Same-sex relations are criminalized by article 230 of the Penal Code, which discriminates against lesbian, bisexual, and transgender women and can also dissuade them from using Law-58 to report violence by an intimate partner or family violence because of their sexual orientation or gender identity.

In 2018, the Commission on Individual Freedoms and Equality, appointed by the president, called for the abolition of the morality laws and recommended decriminalizing homosexuality. The commission recommended eliminating offenses relating to “public indecency” and “public offense to morals” and replacing them with laws to punish a person who “commits a sexual act in public and intends to reveal intimate parts of his body with the intent to harm others.”[66]

Normalizing Domestic Violence

“Some of the women who came to our center said their husband’s violence was proof of their love.”

— Hanine El Kadri, Coordinator at Victory for Rural Women, in Sidi Bouzid[67]

While Law-58 requires private and public media outlets to raise awareness about violence against women and to train their personnel on how to cover the topic (Article 13), Inkyfada, an independent Tunisian investigative outlet, found the media’s coverage of male violence against women is riddled with victim-blaming.[68]

According to a 2022 study conducted by the United Nations Populations Fund Agency (UNFPA) on partner violence, over two thirds of Tunisian men say domestic violence is normal and justified to protect women from their own impulses.[69] A 2019 study by the CREDIF on representations of domestic violence, stated that “many” men they interviewed thought Tunisian women enjoy an excess of rights and that the media exaggerated the scale of domestic violence and downplayed women’s responsibility in causing domestic conflicts. Judge Faten Sebei told Human Rights Watch, “Law-58 is viewed as women’s concern rather than a societal one. Men perceive it as a law that only seeks to advance women’s rights rather than one that makes Tunisian society more equal and advanced.”[70]

Divorced and single mothers are socially devalued and stigmatized in Tunisia, which discourages women from leaving abusers, based on interviews with survivors.[71]

The larger family context generally conditions survivors’ disposition to leave or remain in abusive relationships.[72] When fathers or brothers are violent towards their daughters or sisters as children, the latter tend to normalize it in their adulthood and in forming their own families.[73] A 2019 CREDIF study found that girls over 12 and 18-year-old women were barely aware of Law-58’s existence and did not know family violence was considered domestic violence.[74] Most of the survivors who spoke to Human Rights Watch said their families had discouraged them from filing complaints against their abusers.

“Houda,” 34, from Zarzis, who was physically, economically, and sexually abused by her husband, explained how he became more aggressive in response to her family’s inaction:

One evening, we were all in the house. He was playing on his smartphone while the kids were watching television. I asked him not to open the balcony door because of the wind. I have no idea why, but he hit me in the belly and my shoulder. I called my mom, but she refused to send my dad. My husband mocked me: “You think your family will come to help you? There’s nothing you can do against me.” Then he insulted me and hit

me more.[75]

Yamounta T., 47, from Zarzis, shared:

After he beat me with a stick, I decided to tell his father: “I could have called the police, but I didn’t want to bypass you. Please speak to your son.” […] When my husband came back home, he put a knife under my throat and said: “You spoke to my dad? I’ll slaughter you.” I didn’t move an inch; I was scared he’d kill me.[76]

Disempowering Women

While domestic violence cuts across all classes, men are more likely to abuse women who are poorer or less educated than them, in Tunisia and globally.[77] A national survey on domestic violence published in 2010, found that men committed more violence against women who were unemployed and stay-at-home.[78] Although Tunisian women are enrolled in greater numbers and perform better than men in higher education, they are less present in the labor force and are paid less than them.[79]

Women in Tunisia dedicate a daily average of eight to twelve hours of unpaid work to their households, including those who have jobs outside the home, compared to 45 minutes for men, according to a 2021 Oxfam study.[80] This forces many women to forego or limit their own potential professional or educational pursuits to care for their households, and become financially reliant on men, who are freed to pursue paid opportunities outside the household that give them financial resources, which they can allocate to the household or not, as they wish. Most of the women who spoke to Human Rights Watch said they could not work because of their childcare responsibilities.

Economic subjugation is a common tactic for abusers.[81] Three survivors told Human Rights Watch their abusers had prevented them from working outside the home after they got married. Some of the women who spoke to Human Rights Watch reported that their abusers confiscated money they had earned or received from family members, or destroyed their belongings, such as mobile phones, amplifying their economic dependence on them. When women sought to divorce or file legal complaints against abusers, some men responded by depriving them of food or financial maintenance. Such acts constitute crimes of economic violence under Law-58 (Article 3).

“Fatma,” 44, from Regueb and a mother of four, who filed a complaint against her abusive husband, said:

My husband is not giving us any money since I complained against him. Before, he used to at least give us some money from his crops, especially from the watermelon sales in the summer, but now he stopped completely. He is not giving us a millime and I am the one feeding all of the family with my tiny salary! [82]

Yamounta T., 47, from Zarzis, and mother of two, one of the two women Human Rights Watch interviewed who owned real-estate property, said:

Whenever we had an argument, my husband would hit me. He would keep pressuring me to sell my house or give it to him. To exert pressure, he would not give me any money to feed the children, or he would give me only 10 dinars (approximately $3) to buy groceries. If I protested, he would hit or insult me.[83]

The Maintenance and Divorce Alimony Guarantee Fund, established in 1993 (Law No. 1993-0065) to guarantee women’s financial security where their husbands or ex-husbands “abandoned their families” by neglecting their financial responsibilities toward them has been “empty for years,” according to Bochra Belhaj Hmida, lawyer and women’s rights advocate.[84] Law-58 mentions women’s pre-existing right to spousal maintenance and guarantees re-integration and housing services to survivors of violence and their children, which should mean that authorities should provide for survivors’ financial needs to rebuild their lives independently.[85]

There are regional and racial dimensions to this economic inequality. According to a 2010 national survey on domestic violence, women living in the southwest and southeast of Tunisia are more likely to experience economic, physical, sexual, or psychological violence at least once in their lives, at respective rates of 72.2 percent and 74.7 percent (against a 35.9 per cent rate in the center-east of Tunisia, where it is the lowest).[86]

Regional inequality typifies Tunisia.[87] Southern and interior regions of the country continue to suffer from economic marginalization and state neglect, which some academics, geographers, and economists have argued is rooted in colonial industrialization and post-colonial policies.[88]

Black Tunisian women may be particularly exposed to risks of domestic violence as they mainly live in the south, are more likely to be economically marginalized, and face racial discrimination.[89] Women from other intersecting backgrounds may also face additional risks to domestic violence but there is little to no disaggregated data from these groups on male violence.

Insufficient Implementation of Prevention Measures

Law-58 obliges the state to undertake prevention measures to end violence against women including awareness-raising campaigns and reforms in educational curricula and state official trainings aimed at eliminating all forms of discrimination against women (Articles 6-12).

Awareness-Raising

Interviews with survivors consistently showed, however, women generally have no knowledge of their rights when they decide to seek help or file a complaint against their abusers. The information they have about the services available to them is contingent on word-of-mouth.

The Ministry of Women has tried to raise public awareness of the provisions of Law-58.[90] In 2019, the ministry collaborated with the Ministry of Religious Affairs to have imams include information about Law-58 in their sermons.[91] The Ministry has also organized campaigns during the annual United Nations’ International 16 Days of Activism to End Gender-Based Violence campaign (November 25–December 10).[92] By 2020, the Ministry had conducted short-term awareness-raising campaigns in all but four of the country’s governorates, according to its 2021 annual report.[93]

Yet, all staff of nongovernmental organizations supporting survivors interviewed by Human Rights Watch agreed awareness-raising efforts largely fell short of the needs, especially among rural populations.[94]

The 2021 shadow report to CEDAW, jointly prepared by 22 nongovernmental organizations, said the integration of gender equality education in secondary and university education remained “very insufficient.”[95]

Among the 30 women who spoke to Human Rights Watch, only one, Hayet EK., 44, from Tunis, had used the internet to access information on her rights.[96] None of them had used the national hotline providing information and referrals to survivors of violence against women. The hotline is mainly used by women with secondary or university education seeking legal advice, according to the Ministry of Women’s own statistics.[97]

Early Detection

While Law-58 requires the Ministry of Social Affairs to train social workers on the early detection and referral of cases of violence against women to competent authorities (i.e., the prosecutor or specialized units), staff of state-affiliated and nongovernmental organizations interviewed by Human Rights Watch were adamant the majority of social workers lacked the skills to detect and respond to domestic violence. They said that social workers often fail to appropriately address cases of domestic abuse, even dissuading women from complaining against alleged abusers and instead to engage in family mediation. This pattern was attributed to the tendency to exclude social workers from trainings delivered to personnel from the Ministries of Interior, Justice and Women

on Law-58.[98]

Weak Protection of Survivors and Prosecution of Abusers

Under the Tunisian justice system, the power to investigate crimes, including crimes of violence against women, is shared among the police, prosecutors, and investigating judges. In addition to the set-up of specialized police units to handle complaints of violence against women (Article 24) under the public prosecution’s authority and control, Law-58 prompted the designation of specialized prosecutors and assistants to receive complaints of violence against women (including the recording of initial testimonies) and to follow up on them.[99]Survivors have the option to file complaints for violence against women either in court or with the specialized units of the police.

Prosecutors and their assistants systematically refer cases of violence against women involving a potential sentence of more than five years to investigative judges.[100] The latter are vested with substantial powers in matters of criminal investigations, including: the conduct of on-site visits, the gathering of evidence, the interrogation of suspects, and the collection of testimonies from victims and witnesses.[101]

According to various members of the judiciary, in virtually all cases of violence against women involving potential sentences of less than five years, prosecutors and their assistants refer complainants to specialized units to pursue the investigations. [102] As a result, most investigations pertaining to domestic violence are, in practice, police-led.

Police Response to Domestic Violence

Since Law-58 first started being implemented, women have complained about pressures police officers had exerted on them and the undignified way in which they were received. We have come a long way, but there are still gaps in the police’s response.

— Women’s rights advocate, Bochra Belhaj Hmida[103]

Since the passing of Law-58, authorities have taken steps in line with it, notably establishing specialized units across Tunisia’s 24 governorates and training their officers to respond to violence against women. However, specialized units’ response to domestic violence remains inadequate. There are inconsistencies in the police’s response to domestic violence due to operational constraints, including limited operating hours and insufficient vehicles, and poor implementation of the law involving failures to inform survivors of their rights; requiring (recent) initial medical certificates from them to launch investigations or protection measures; dismissive attitudes; and mediation attempts.

This is in breach of Law-58, and goes against Tunisia's obligations under international law. The UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, in its General Recommendation 19, notes: “States may also be responsible for private acts if they fail to act with due diligence to prevent violations of rights or to investigate and punish acts of violence, and for providing compensation.”[104]

Set-up of Specialized Units

Law-58 obligated the state to establish specialized units within every national guard (gendarmerie) and police station of every governorate to handle crimes of violence against women (Article 24), which is in line with the United Nations’ Office on Drugs and Crime recommendations on strengthening the response of criminal justice systems to violence against women.[105]

Before Law-58 was adopted, the police were barely trained and equipped to investigate domestic violence complaints, according to research by human rights organizations.[106] According to a 2010 national survey, this lack of preparedness led to an under-reporting of domestic violence, with only 1 in 25 women who said they had experienced domestic violence at some point in their lives had reported the abuse to police units.[107]

Six months after the law’s adoption, the Ministry of Interior set up 128 specialized units across all governorates.[108] As of April 2022, two additional specialized units were set up, for a total of 130 units (70 in police stations and 60 in national guard stations), according to Najet Jaouadi, head of Customs Police and former head of eight specialized units.[109]

In 2021, specialized units registered nearly 69,000 complaints of violence against women and girls.[110] Following the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic, in 2020, specialized units registered 38,289 such complaints.[111] In 2019, specialized units registered 64,979 complaints of violence against women and girls, of which 3,370 had led to legal proceedings, including 2,500 domestic violence cases.[112] Jaouadi told Human Rights Watch that prior to specialized units’ creation, the police registered about 15,000 complaints of violence against women annually, 5,000 of which were for spousal abuse.

Lack of Visibility and Limited Operating Hours

“Unless a woman is about to die, the police will tell her to come back whenever specialized units are available.”

— Monia Kari, former head of the National Observatory for the Elimination of Violence Against Women, December 7, 2021.

Signs informing the public about specialized units’ functions and locations are rare. Most of the women who spoke to Human Rights Watch said that before they reported violence by their abusers, they had not heard of the specialized units. They had first gone to regular police units to which no specialized unit was attached before being directed to a specialized unit. By contrast, the two women who had seen signs about the specialized units were able to remember them when they needed to report domestic violence.

Men usually assault women at night.[113] Yet, specialized units operate only during daytime (approximately 8:00-17:00), and on weekdays.[114] Outside administrative hours, complainants must turn to regular police. However, the latter have not in general been sufficiently trained on Law-58 to deal with complaints of violence against women.[115]

In July 2021, after a severe beating by her husband, Fatma, 44, from Regueb, decided to file a complaint against him. Her work schedule as a cleaner prevented her from visiting a specialized unit during administrative hours:

I went twice to the police station in Regueb. The first time they told me the specialized units weren’t here and didn’t ask me any other question. I felt as if I had bothered them, so I walked back home. A few days later, I went back and they told me to put a file together and submit it to the public prosecutor at the municipal court. But I didn’t know how to go about it. I felt confused so I left and gave up.[116]

Lack of Personnel and Dedicated Rooms

Personnel of specialized units told Human Rights Watch they lacked human resources to fulfill their role.[117] Salem Mnafeg, head of the specialized unit in Zarzis, deplored the limitations of his units’ human resources, which covers the large territory of the Mednine governorate. He said, “We try to get other police units to support us with arrests and transporting victims when we are short of staff or vehicle, but if, say, something happens in a school that might expose girls to violence, it falls on us and it’s almost impossible to handle all case of violence against women at the same time.”[118]

Article 24 of Law-58 states specialized units should include female staff, without specifying quotas, ranks, or responsibilities. Among the women Human Rights Watch interviewed, none of the 20 women who reported domestic violence to the police said they had spoken to a female police officer.

According to Najet Jaouadi, former supervisor of eight specialized units, by April 2022, 32 percent of the specialized units nationwide were headed by women, but that not all included female staff.[119] In a 2021 shadow report on Tunisia’s compliance with CEDAW, 22 nongovernmental organizations said specialized units did not have enough female

police officers.[120]

Given the taboo shrouding domestic violence, especially sexual abuse, the lack of female officers responsible for interviewing survivors may deter women from reporting abuse. Nearly one out of six married women is exposed to sexual violence from their intimate partner, according to a 2010 national survey.[121] However, survivors of domestic violence rarely disclose sexual violence when filing their complaints due to taboos surrounding sexuality and the insufficiency of female police officers and private rooms in specialized units, according to staff at counseling centers interviewed by Human Rights Watch.

Survivors typically base their complaints to the authorities on non-sexual forms of violence and disclose instances of sexual violence at later stages during the investigation, if ever.

Houda, 34, from Zarzis, told Human Rights Watch that she had felt too ashamed to describe to the male police officer taking her complaint the sexual violence that her husband inflicted on her when she filed a complaint against him for physical and economic abuse in June 2021:

As soon as I could, I went to the specialized units in Zarzis and told them everything about all the years of violence. Actually, I tried to tell them everything but there were things I couldn’t say out loud. I was too ashamed. Then, the policeman gave me a pen and paper. I don’t know how I found the strength to do it, but I wrote it all; the words suddenly flowed until I had nothing left to say. I wrote about things I had never told anyone about and didn’t even let myself think of. Then, I filed my first formal complaint about physical and sexual violence.[122]

No other survivor reported to Human Rights Watch that police officers had invited them to write down their experiences in case doing it orally was too difficult.

Article 28 of Law-58 also specifies survivors of sexual violence may request to be heard by the police in the presence of a psychologist or social worker, but it does not specify the process for such requests. In practice, this has meant that police do not inform survivors that such an option is available to them. None of the women interviewed by Human Rights Watch who said they had experienced sexual violence were informed of their right to request a psychologist or social worker to assist in their interaction with the police.

Most specialized units were set up within the pre-existing stations of the police or national guard. As such, not all specialized units have their own quarters or sufficient rooms to interview survivors privately.

When specialized units lack dedicated rooms for conducting confidential interviews, officers in the unit may ask other officers to leave so they can interview survivors in privacy. The lack of assured privacy in specialized units could deter survivors from reporting domestic violence, according to a coalition of nongovernmental organizations supporting survivors in Tunisia.[123]

Jaouadi, former supervisor of eight Specialized Units, said new specialized units were being built in Sidi Bouzid and Monastir for instance, with exemplary structures and dedicated space to interview survivors in privacy.[124] She said United Nations agencies were funding projects to build new specialized stations in Zarzis and Kasserine.

Lack of Vehicles

Law-58 requires specialized units to immediately go to the crime scene to investigate when they learn of flagrant délit cases of violence against women (Article 25) and to transport survivors to first aid spaces or shelters as needed (Article 26). However, adequate means of transport have not been allocated to specialized units, according to frontline respondents and police officers interviewed by Human Rights Watch.

The shortage of vehicles hampers the response readiness of specialized units and heightens the vulnerability of survivors who live in remote areas or who cannot afford transportation due to care responsibilities or a lack of means. “I know police officers—men and women—who spent their own money to cover taxi rides for survivors,” said Amal Yacoubi, Oxfam’s gender justice program coordinator.[125]

Ineffective Training

Handbooks and trainings have been developed to support the Ministry of Interior’s training of police officers on Law-58’s provisions.[126]

In December 2021, Jaouadi told Human Rights Watch that all staff working in specialized units had undergone trainings on Law-58 organized by the Ministry of Interior in partnership with national and international organizations.[127]

However, most lawyers and frontline respondents who spoke to Human Rights Watch said police trainings on Law-58’s provisions had not sufficed to change the dismissive attitudes most police officers have towards women who complain of domestic violence.[128]

Staff of nongovernmental organizations supporting survivors and Monia Kari, former head of the National Observatory for the Elimination of Violence against Women, assessed that police trainings focused excessively on legal and procedural dimensions of Law-58, and insufficiently on raising awareness of the cyclical nature of domestic violence and trauma-sensitive communications skills.[129]

Mishandling Survivor Complaints

For survivors, how the police receive and treat them deepy affects their readiness to take legal action against their abusers.[130] Survivors’ interviews with Human Rights Watch revealed frequently discouraging police responses to domestic violence.

Failure to Investigate

Prior to the adoption of Law-58, Amnesty International documented cases where police discouraged, tacitly or explicitly, women from filing complaints of domestic violence.[131] These involved instances of victim-blaming and of prodding complainants to reconcile with their alleged abusers.[132]

In line with the CEDAW Committee’s recommendation, Law-58 requires specialized units to immediately investigate as a criminal matter all flagrant cases of violence against women.[133] Article 25 subjects to a six-month prison sentence specialized unit officers who are found to pressure survivors to forgo exercising their rights under the law, modify their deposition, or withdraw their complaint. Members of the judiciary who spoke to Human Rights Watch said that, to their knowledge, Article 25 had not been led to any police investigation since the law’s adoption.[134] The Ministry of Interior did not reply to Human Rights Watch’s written request for information about the implementation of Article 25.

Najet Jaouadi, head of Customs Police and former head of eight specialized units, said that, to her knowledge, there had only been one case of a complaint issued against a police officer in light of Article 25 since the law’s adoption. [135] She said: “It was a lawyer who’d gone to the specialized units to file a complaint for violence against women, around 2018 or 2019. The police officer handling her case had tried to dissuade her from going ahead with it. He didn’t know how educated she was! As a lawyer, she knew her rights and filed a complaint against him.” Jaouadi was unsure whether this complaint had led to any investigation or condemnation of the police officer.

Despite these legal provisions, nine out of the twenty women we interviewed who had complained to the police said they had faced dismissive attitudes.

Sana, 31, from Zarzis, said that when she complained about her husband’s years of physical and economic violence in November 2021, a police officer asked her: “So, do you want to forgive him or should we arrest him?”[136]

Sana insisted she would not forgive her abuser, but not all survivors are the same. Police officers should refrain from suggesting reconciliation and instead treat domestic violence as the crime that it is, ensuring that they are filing complaints and proceeding with investigating the offense and assisting survivors, regardless of the inclination of any survivor to forgive.

In six cases reviewed by Human Rights Watch, the police actively discouraged survivors from complaining against their abusers and encouraged reconciliation in the name of preserving the family, or refused to take appropriate measures to investigate the alleged crimes. Women’s rights organizations and survivors told Human Rights Watch that the police are especially reluctant to investigate complaints against violent family members, as opposed to partners.

“Meriem,” 19, from Beja, who said her brother and father had abused her for years, recounted her attempt to file a complaint against them, in 2021:

My dad, granddad, brother, and cousin also came in with me to the police station. They were not far away from me, but I spoke to the police alone. I told them everything that had happened in detail, from the beginning. One of the policemen said: “That must be terrifying.” They recorded everything I told them. I was crying and shivering. When I was done, one of the policemen said: “They need to be arrested.” But then they just took me to this shelter and didn’t do anything to them. I don’t know why they didn’t arrest them.[137]

Meriem said that she did not hear from the police about whether they conducted any further investigation or the status of her case. She also said they did not inform her of

her rights.

Lawyers, staff of nongovernmental organizations, as well as social services supporting survivors must often tailor their assistance to minimize risks that the police will

mishandle complaints.

Hanen Hnid, a lawyer in Zarzis, said she coordinated with a non-governmental organization to ensure a case worker from their staff could accompany them to specialized units when filing their complaints.[138]

Arbia Alahmar, a social worker at the National Union for Tunisian Women, said every six to eight weeks she had to write letters in the name of her organization asking specialized units to treat individual cases of survivor complaints in a timely manner.[139] Alahmar said she did so because the specialized units sometimes told women seeking to file a complaint against their abusers “to go home” or “come back later.” Yet, an immediate response by specialized units is necessary to preserve evidence, ensure survivors do not withdraw their complaints, and that they can access protection.

The police also use the lack of shelters as a reason not to issue protection measures or orders.[140] In December 2021 (before the opening of a shelter in the summer of 2022), Ali Joua, head of the police specialized unit in Gabes, said the lack of nearby shelters to host survivors was another reason the police rarely issued protection measures.[141]

Nahla, 40, from Ben Arous, recounted how in 2021 the police refused to take her complaint and provide her with safe accommodation:

When I went to the police station after my husband hit me with a brick, the chief of the police unit refused to take my complaint and told me: “Just leave and find yourself a place to stay. We have no place to take you to. Figure it out. Unless you’re about to die, the state is not interested in helping you.”[142]

Arbitrary Evidentiary Requirements

Law-58 does not specify evidentiary requirements to prove domestic violence.

However, interviews with women who sought to file complaints revealed that in practice the police treat initial medical certificates, which are issued by public doctors, as a prerequisite for launching investigations into allegations of violence against women. When the police receive complainants of physical domestic violence, authorities issue them a requisition that they can present to any public hospital to access a free medical consultation and an initial medical certificate.[143] Women are expected to go to the hospital themselves to acquire a medical certificate, which they must bring back to the police before they will consider launching an investigation.

Police, prosecutors, and judges should not require medical certificates before launching an investigation; a woman’s firsthand account should be sufficient. In addition to launching an investigation, they should explain the investigation process and advise women who have physical injuries on how a forensic medical certificate may help support their case for prosecution. Evidence collection, however, should not be limited to

medical reports.

The second time Nahla attempted to file a complaint against her abuser, she said the specialized units refused to investigate her case because she had no recent

medical certificate:

In September 2021, my husband continued to be violent. When he choked me, I decided to try to file another complaint against him at the police station. The police told me to get a medical certificate. I told them I’d already given them one last time I’d filed a complaint but they refused to do anything. They didn’t take me seriously at all. I didn’t feel like I had just told them about a crime! I just went back home afterwards.[144]

The police did not launch an investigation based on her testimony or on the fact that there was history of violence including complaints filed in the past. They also did not offer to take her to the hospital to help record the injury or inform her of any other rights she was entitled to.

Police officers also attribute time limitations to initial medical certificates, considering them no longer valid if the complainant brings her certificate to the police beyond what they consider the period of validity. According to women and frontline respondents whom Human Rights Watch interviewed, the period of validity varied from one location to another and ranged from 48 hours to 5 days, or a week or two.

Imposing expiration dates to initial medical certificates undermines the right of survivors to seek justice against their abusers at a time when they are ready to do so. The practice could expose survivors to further violence. It is also problematic as it ignores the reality that domestic violence often results in cumulative smaller physical injuries over time, or other non-physical or less-visible harm such as brain trauma.[145]

Jaouadi, the Customs Police Director who drafted the 2019 police protocol for the elimination of violence against women, told Human Rights Watch that no legislation indicates that initial medical certificates should have an expiration date. She said that prosecutors often imposed such requirements in their local practices.[146]

Fatma, 44, from Regueb, said the specialized unit of the National Guard in Sidi Bouzid rejected her complaint when she tried to report her husband’s violence in October 2021: “The police said the initial medical certificate had to be no more than one week old to allow them to investigate.”[147]

Ahlem, 26, from Sidi Bouzid, who said she was beaten, humiliated and forced to work without compensation for seven years by her husband, recounted:

In August 2021, I went to the police station in Sidi Bouzid to file a complaint, but the specialized units told me I couldn’t do anything with my [three] medical certificates [dating from 2018, 2020, and 2021] because all of them had been issued more than 15 days ago. I felt so discouraged. Any woman would lose her strength at that point. I am illiterate; why aren’t my rights protected? Why didn’t anyone tell me my certificates would lose their validity after a couple of weeks?[148]

Once survivors obtain the medical certificate, they must return them to the relevant authority to initiate a criminal investigation. “Initial medical certificates issued by requisition – as opposed to those issued at women’s own request – are important, confidential legal documents. As such, technically, the police should try to obtain it from the doctor or the doctor should give it to the authorities. But in practice, that is very complicated to achieve, so we rely on women to act as intermediaries to deliver the certificate to the police,” explained forensic doctor Wiem Ben Amar, professor of medicine at the University of Sfax and an expert in issues relating to violence against women.

Staff of nongovernmental organizations who spoke to Human Rights Watch voiced concern that the lack of certainty regarding when the initial medical certificates would be ready, and all the back-and-forth involved in obtaining them, could discourage them from pursuing complaints.