Summary

Afro-descendant communities have a right under Colombian law to collective land. However, in practice, communities have long faced significant challenges in exercising this right, including in obtaining title, and in using and benefiting from collective land, including already titled land. Perhaps the single most important challenge to communities’ access to land has been violence associated with Colombia’s decades-long internal armed conflict, which has displaced millions and continues to impact many.

Despite a 2016 peace agreement between the government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) guerrillas, ongoing violence by armed groups in rural areas continues to impede Afro-descendant communities’ access to land, including by triggering waves of displacement and contributing to serious negative economic outcomes. In turn, Afro-descendant people who lack access to their land experience serious economic consequences, compounded by racial discrimination and—for women and girls—discriminatory gender norms.

The administration of President Gustavo Petro and Vice-President Francia Márquez has promoted a “total peace” policy that seeks an accord with the National Liberation Army (ELN) guerrillas and the negotiated disarmament of other armed groups, including criminal gangs. It has also vowed to implement the 2016 peace accord, including its land policy reforms, and to prioritize racial, ethnic, and gender equality.

This report is based on 71 virtual and in-person interviews in Colombia, including with 30 women from Alto Mira y Frontera, an Afro-descendant community council (the governing boards for Afro-descendant territories) in the municipality of Tumaco, in the southern state of Nariño, as well as activists, academics, representatives of local non-governmental organizations, government officials, and members of the Truth Commission established under the 2016 peace accord. The report uses the case study of Alto Mira y Frontera to describe some barriers to Afro-descendant communities’ access to land, with a focus on Afro-descendant women. In particular, the report focuses on how violence, fear, and displacement, has impacted the ability of communities to benefit from already titled collective land. These difficulties are compounded by slow restitution procedures for communities that have been displaced as a result of the armed conflict, leaving survivors in limbo while they wait to return to their land.

Violence, Insecurity, and Displacement in Alto Mira y Frontera Community Council, Tumaco, Nariño

Armed or criminal groups, including new groups that emerged or took over territory after the demobilization of the FARC, are responsible for violence and restrictions on movement in and around Alto Mira y Frontera and other communities around Tumaco municipality. These groups, including especially groups involved in the drug trade and other illegal economies with an interest in the land around rural communities, have continued to facilitate dispossession and forced displacement.

The persistence of violence and the emergence of new armed and criminal groups, spurred by inadequate governmental action, has heightened anxiety and fear among community members in Alto Mira y Frontera. The movement of local community members is restricted by unpredictable curfews imposed by armed groups, and they must obtain permission from those armed groups to enter their community. Fear of armed confrontations or encountering antipersonnel landmines dissuades them from going to their farms to plant or harvest crops, or to forage in forested areas, which community members say has worsened their food insecurity and poverty.

Unable to live peacefully, many individuals and families flee their original lands for safety, leaving their homes, farms, and resources that had sustained their livelihoods. Some women said they fled to prevent their children from being recruited by armed groups.

Loss of Access to Land and Deepening Poverty as a Result of Displacement and Racial Discrimination

Short-term or prolonged displacement due to the armed conflict and the ongoing violence from armed groups has caused severe instability in displaced people’s lives, often exacerbating food insecurity, entrenching poverty and furthering inequality. Separated from their traditional means of subsistence, displaced Afro-descendants in cities described the hardships of inserting themselves into an already tight labor market marked by stigmatization and racial discrimination, forcing them into menial, labor-intensive, low-paying jobs. This hardship is even greater for households headed by single women who are victims of the armed conflict, including those who lost partners or other family members to violence related to the armed conflict, or who themselves have been targeted and displaced.

Gender Roles within Collectives Reinforce Women’s Unequal Land Access

For women in Alto Mira y Frontera, overall difficulties in accessing land are compounded by gender norms and disparities in authority. The women we interviewed identified gender discrimination through institutional and structural processes, machismo, and a lack of decision-making power as drivers of gender inequality and unequal division of land within their communities. According to a woman who is a former council member from Alto Mira y Frontera, men on the council’s governing board have significantly larger landholding than women due to gender disparities in decision-making power. While men are well represented in leadership positions in the community, including on the community council board, there was only one woman among the leadership when Human Rights Watch visited the area in July 2022. The majority of women, not reflected in leadership and due to discriminatory gender norms, do not play a significant role in land use governance decisions, despite the collective nature of land ownership in the community and role they play in working the land.

With a new administration in Colombia that has vowed to implement the 2016 peace accord and to promote equity, there is an opportunity to ensure that social and economic development policies are responsive to and integrate ethnic, racial, and gender needs.

The government should pursue the necessary, often complex and structural, changes, to address the status quo of violence, displacement, and access to land especially in rural areas that disproportionally impacts Afro-descendant, Indigenous, and peasant communities. These efforts require ensuring adequate resources and political support for the implementation of the 2016 peace accord, as well as seeking the collaboration of civil society, multilateral, and bilateral organizations.

Methodology

This report is based on research conducted by Human Rights Watch between October 2021 and September 2022 in Bogotá, and Tumaco, Nariño state, Colombia.

In July 2022, Human Rights Watch researchers visited the city of Tumaco, in Nariño state, which borders the Pacific coast. Human Rights Watch focused its research on the Alto Mira y Frontera Community Council to examine how armed groups affect the ability of communities, even with collective title, to access and benefit from their land. Community Councils are, under Colombian law, the governance authority of the collective territory of each Afro-descendant community in Colombia.[1]

Human Rights Watch interviewed 30 women and 5 men from Alto Mira y Frontera’s Community Council, in Tumaco. The five men and one woman were members of the community council board. Three women were interviewed as a group at their request; all other interviews were conducted individually. Human Rights Watch also conducted in-person and virtual interviews with 31 representatives of national and international nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), activists, academics, and lawyers in Bogotá between April and September 2022. It also interviewed two members of the Truth Commission (one via videoconferencing and one in-person in Tumaco), officials from the Human Rights Ombudsperson’s Office, and the Agency of Territory Renovation (Agencia de Renovación del Territorio), a body charged with coordinating the implementation of local development in areas affected by the armed conflict.

All interviews with the Afro-descendant community members, and majority of interviews with academics and non-governmental organization representatives, were conducted in English with Spanish interpretation. The researchers informed all interviewees about the purpose and voluntary nature of the interviews, and the ways in which Human Rights Watch would use the information. The researchers obtained consent from all interviewees and gave them the opportunity to decline to answer specific questions or to end the interview at any time.

Human Rights Watch did not compensate interviewees for participating in the research, but the organization reimbursed the cost of transportation for interviewees and provided lunch and refreshments.

Human Rights Watch reviewed primary sources, including laws, ministerial regulations, court decisions, and other legal documents related to land rights for Afro-descendant communities. Human Rights Watch also reviewed secondary sources including reports from non-governmental organizations and research institutes, and media publications.

The report uses pseudonyms and withholds identifying details for some interviewees to protect their privacy or safety from possible reprisals.

Human Rights Watch follows the practice of local organizations in using the term “Afro-descendants” as a collective term referring to members of Black, and Afro-Colombian communities, which are the predominant afro communities in Tumaco, Colombia.

We use the terms “collective land” or “community land” in this report to refer to legally or socially recognized entitlements to access, use, and control land and related natural resources, in line with usage of this term in the Colombian constitution of 1991, Law 70 of 1993 and decree 1745 of 1995, and international standards on land governance and secure land tenure.[2] Land tenure systems determine who can use land and related resources, in what way, for how long, and under what conditions. They may be established in legislation or recognized in customary practices. Generally, each tenure system has a unique set of rules and no single system of governance can be universally applied.

In most cases collective land is owned jointly (shared rights to use and manage) and by agreement by members of the community. In the case of Alto Mira y Frontera, community members Human Rights Watch interviewed said that individuals do not legally ‘own’ their property, but rather have rights to occupy, use, and benefit from the land. The community council issues land use permits, which serve as a guarantee from the community and can be used as collateral to obtain a loan. These land use permits can be used to transfer an individual’s rights to occupy, use, and enjoy to others within their community.[3]

I. Background

Colombia has one of the largest economies in Latin America.[4] However, the country faces worrying levels of poverty, with a large gap between urban and rural areas, and high inequality.[5] Colombia’s Gini Index, a measure of inequality where zero (0) means absolute equality and 100 means absolute inequality, was 54.2 in 2020, and 49.7 in 2017, the lowest in more than two decades of data.[6] Currently, the country is ranked as one of the most unequal across South America based on available data.[7]

Armed Conflict

Colombia’s decades-long armed conflict involving government forces and armed groups, including paramilitaries and guerillas, has significantly impacted rural areas where Indigenous, Afro-descendants, and peasants live.[8]

Tensions related to unequal distribution of land, where a small group of landowners owned most of the agricultural land, were a contributing factor, among others, to the conflict.[9] This high concentration of rural property and unequal access continues to be an important contributor to the ongoing violence to date.[10]

The administration of President Juan Manuel Santos signed a peace agreement with the main guerrilla group, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia, FARC), in 2016.

While the FARC did in large part demobilize, other armed groups, dissident factions of the FARC, and criminal groups are still active, particularly in rural areas of the country, causing violence and other types of human rights violations, including restrictions on movement that disproportionately affect Indigenous and Afro-descendant communities, triggering waves of forced displacement that have pushed families out of land they depend on for their livelihood and into extreme poverty.[11] Lack of implementation of key aspects of the peace agreement, including the failure to adopt effective steps to dismantle armed and criminal groups, and the precarious state presence in many rural areas, have contributed to ongoing violence and insecurity in rural areas, triggering new waves of displacement into urban areas[12] and potentially exacerbating poverty for affected populations.

Ongoing Violence and Displacement

Due to the armed conflict and the ongoing violence by armed groups and criminal groups, more than 9.5 million people have been displaced across the country since 1985, abandoning their land or fleeing after their land was forcibly seized.[13]

In 2022, there were more than 4.8 million internally displaced people registered in Colombia, with about 339,000 internally displaced in that year alone.[14] By 2021, 51 percent of the victims of displacement were in monetary poverty, that is, they did not have the minimum income to cover the cost of a basic basket of goods and services (food and non-food); and 18 percent were extremely poor, that is, they did not have the income to buy a food staple basket.[15]

The armed conflict and experiences of displacement have disproportionately impacted communities in rural areas, including Indigenous and Afro-descendant communities and other communities that had collective title to their lands.[16] Their displacement and inability to safely return has deeply affected Afro-descendant communities because their concept of territory defines their identity, culture, and way of life, including their livelihood.[17] According to one Afro-descendant woman, “People don’t know the sentimental part of the territory. There are lots of emotions tied in it.”[18] Thus, when their access to their land is disrupted, their identity and ability to determine their own development is negatively impacted.

Afro-descendant and Indigenous women have been especially impacted by violence that has left them as single heads of households. According to UN Women 2016 data, female-headed households in Colombia had the highest rates of poverty, even more so in rural areas.[19] According to a 2019 report from Colombia’s Human Rights Ombudsperson’s Office, women belonging to indigenous and Afro-Colombian communities have been disproportionately affected by the armed conflict, with 51.6 percent of indigenous women and 40.7 percent of Afro-Colombian women declared to be victims of the conflict. Of these, 59 percent of the indigenous women and 62.7 percent of the Afro-Colombian women were displaced.[20] Dozens of women have also suffered sexual and gender-based violence related to the armed conflict, contributing to forced displacement,[21] which in turn compounds their vulnerability to further sexual and gender-based violence while they are internally displaced.[22] Once these women are displaced, they have little or no alternative economic activities or resources, they face gender and racial discrimination in finding jobs, and they are pushed into taking on additional care work duties outside the home – an invisible burden of displacement.

Contextual Situation of Afro-Descendant People

Afro-descendants in Colombia trace their ancestry to enslaved Africans who were forcibly transported to the country in the 1500s.[23] They have faced domination through violence, marginalization, and discrimination, all of which contribute to economic marginalization and systemic denial of their economic, social, and cultural rights. In 2018, the National Administrative Department of Statistics of Colombia (Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística, DANE) indicates that approximately 3 million individuals self-identified as Afro-descendant, a 30 percent decrease from 2015 population census.[24] DANE has since adjusted the population estimate for Afro-descendants to approximately 4.7 million.[25] DANE data showed that 30 percent of Afro-descendants live in “multi-dimensional” poverty and lack access to adequate housing, formal employment, and basic schooling.[26] According to organizations that advocate for the rights of Afro-descendant people, the number of Afro-descendants in Colombia who face this type of multi-dimensional poverty is much higher than the figures presented in the 2018 census.[27]

San Andrés de Tumaco

Inadequate Public Services

The insecurity and inadequacy of basic public services contribute to high rates of poverty and a precarious quality of life in Tumaco municipality.[28] DANE recorded that Tumaco had a municipal multidimensional poverty incidence rate of about 54 percent in 2020, with a huge gap between the municipal capital (46 percent) and the rural areas (64 percent).[29] The higher rate in rural areas is largely driven by a range of factors (low educational achievement; poor or no access to an improved water source; lack of sanitation) that reflect inadequate access to public services.[30] In 2018, about 27 percent of the total population of the municipality had what the study referred to as their “basic needs” unmet, with 18 percent in the municipal capital and 38.7 percent in rural areas.[31]

Coca Cultivation

The Pacific region ranks highest among all regions in Colombia in cultivation of coca, the raw material used mostly to produce cocaine, with 44 percent of the national total at 89,266 hectares in 2021, representing the highest figures in the last 20 years of monitoring.[32] Of those, 56,516 hectares were in Nariño, with Tumaco being the municipality with the highest number of hectares in the state.[33] Cultivation of coca doubled from 2020 to 2021 in Afro-descendant community councils, from approximately 21,800 ha to 42,500 ha, with Alto Mira y Frontera one of four councils with the largest area under production.[34]

Alto Mira y Frontera

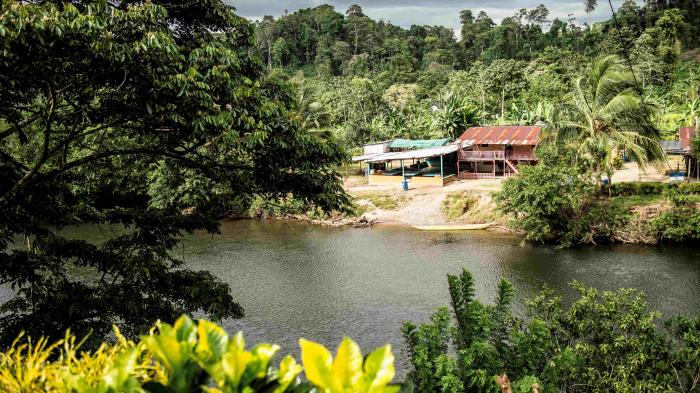

The Community Council of Alto Mira y Frontera (CCAMF) is in the southeast of the municipality of Tumaco, bordering Ecuador. The Colombian Institute for Rural Development (Instituto Colombiano de Desarrollo Rural, INCODER), the government agency responsible for individual and collective land titling, awarded the community council’s collective title in 2006.[35] The community council comprises 43 villages, with an area of 24,000 hectares, of which between 800[36] and 1,500 hectares are contested due to factors such as conflicting claims over land titled to the community council and to the Indigenous Awá, the existence of peasant farms, and palm oil companies within their land,[37] the weak presence of the state, and the abuses by armed groups that have caused displacement and confinement.

There are also 140 private properties that are not part of the collective title, but that are claimed by the Afro-descendant community.

II. The Impact of Ongoing Violence on Afro-descendants’ Land Access in Alto Mira y Frontera

We have heard about peace before, peace here, peace there, but there is no peace.

— Isabella U., Tumaco, July 2022.[38]

The presence of armed and criminal groups, their pressure on communities to cultivate coca, and ongoing violence due to clashes among these groups and with government security forces has continued in the area around Tumaco due in part to the inadequate execution of the peace agreement. In Alto Mira y Frontera, there have also been land or boundary conflicts between Afro-descendant community councils and Indigenous communities, on the one hand, and peasant settlers, on the other. All these elements have affected the ability of Afro-descendant communities to enjoy their land rights, even when they have collective title.[39]

The 2016 peace agreement sought to break the country’s cycle of violence and outline a path for the government to work with communities to, among other things, address their lack of enjoyment of economic, social and cultural rights, insecure land rights, and lack of protection.[40] However, seven years later, violence persists, and is even on the rise in parts of the country.[41] Such ongoing violence is in part the result of the government’s failure to fully implement the 2016 peace agreement, including sections that seek the demobilization of armed groups.[42] According to the Kroc Institute, which the accord gives a formal role in monitoring compliance with the deal’s commitments, Colombia fulfilled 86 percent of the commitments it had undertaken to in 2017, but only 61 percent of those for 2018, 42 percent in 2019, and 50 percent in 2020.[43] Only 4 percent of the accord’s rural reform measures are complete.[44]

Previous Human Rights Watch reporting has illustrated how in the years since the peace process, new armed or criminal groups have filled the power vacuum left by the demobilization of the FARC and the negligible presence of state authorities; other groups that were already operating did not participate in the peace process; and some factions of the FARC failed to demobilize.[45] Recent years have seen a rise in killings of social leaders (both men and women)[46] and continued forced displacement. This situation has, in turn, hampered access to land, including collective titling (per Law 70) or land restitution (per the peace agreement and the Victims Law).[47] These factors have also prevented displaced populations from returning.[48]

In Tumaco, interviewees expressed a palpable fear of violence and displacement,[49] which affected their access to land and heightened perception of tenure insecurity. The ongoing violence in Tumaco and nearby areas is complex, involving FARC dissident groups and criminal groups.[50] The two main armed groups operating in Tumaco are coalitions of FARC dissidents, known as the Western Coordinating Command (Comando Coordinador de Occidente), also called the Western Block “Jacobo Arenas”, and the Second Marquetalia, which often operates locally under the name of Pacific Guerrilla Coordination (Coordinadora Guerrillera del Pacifico).[51] These coalitions, which engage in fighting against each other, have gathered other armed groups operating in the area.[52]

Residents Human Rights Watch interviewed from Alto Mira y Frontera identified several major challenges to accessing, managing, and benefitting from their territory related to armed and criminal groups: restriction of movement because of curfews, antipersonnel landmines, and general insecurity due to armed groups operating in the area; violence or the threat of violence by armed groups; and child recruitment by armed groups.[53] Previous Human Rights Watch reporting in 2018 highlighted ongoing violence in Tumaco.[54] Dozens of women were raped by or suffered other forms of sexual violence at the hands of members of armed groups.[55]

An officer with the Human Rights Ombudsperson’s office in Tumaco said, “There are too many armed groups in the Pacific [region]. Usually about 8 to 10 different armed groups, fighting over the territory, because the location is geographically strategic for growing coca and evacuating it through the Pacific coast, it is the ethnic communities that suffer.”[56]

As Human Rights Watch has noted elsewhere, to address ongoing violence in a sustained manner over the long term, it is critical that the government tackle the root causes of the problem.[57] That will require a focused effort to permanently reduce the power of armed groups and organized crime through a range of measures, including criminal investigations aimed at dismantling these groups, as well as a more effective and substantial civilian state presence in remote regions. However, because of the immense profitability of the illegal drug trade, and the ability of criminal groups to corrupt authorities—even where there is a state presence—it is likely that new groups will continually step in to replace those that have disappeared and keep engaging in violence. It is crucial that the Colombian government adopt meaningful measures to stem this decades-long cycle, including by considering alternative approaches to drug policy that would reduce the profitability of the illegal drug trade, as well as by increasing social and economic opportunities in remote areas of the country.

Community members in Alto Mira y Frontera identified other challenges to accessing land, including that the community council’s boundary overlaps with Indigenous territory, land or boundary conflicts with plantation owners, and the presence of “campesinos settlers” organized as the Association of Mira, Nulpe and Mataje Community Boards (Asominuma) within their territory.[58] For this investigation Human Rights Watch focused on the ongoing violence from armed groups that they say interferes with their ability to benefit from their land, or has even caused displacement.

The community has faced intense violent attacks, including against members of its council board.[59] The consequent difficulties due to restriction of movement, ongoing violence and fear have created challenges for community members in accessing their farms and using their land, including forcing residents to flee to more secure urban areas, with significant implications on their economic well-being and livelihoods.

Restriction of Movement

All residents from Alto Mira y Frontera interviewed by Human Rights Watch reported being constantly monitored by members of various armed groups operating in the area. In addition, they all mentioned curfews imposed by the groups and other restrictions on their movement.

Mariana V. described the restrictions and fear due to armed groups:

The armed groups impose restricted hours to travel into and move around in the area. One of the groups, ‘Los Contadores,’ does not let anyone enter the territory. Other groups tell us we can’t go to certain parts of the territory. The community councils keep quiet out of fear; the groups keep weapons and can act to prevent us from entering or going out of the territory. Many people have left the community because of this situation.[60]

Daniela G., another woman from Alto Mira y Frontera, said, “We must ask for permission from the armed groups to enter [our land]. Often, we can’t go to our farms because armed groups are there. We fear getting into an armed confrontation with them.”[61]

Violence, Threat of Violence, and Fear

In Alto Mira y Frontera, the situation has worsened in the last six to seven years (a timeframe that entirely overlaps with the period since the peace agreement), with armed groups relocating closer to their community, targeting community members who oppose growing coca crops, and various groups competing over control of the area in a bid to secure more land under their control for coca cultivation, and creating a climate of fear. An official with the Human Rights Ombudsperson’s office, interviewed by Human Rights Watch, provided a similar analysis of the complex nature of the situation in Tumaco, which is related to the larger context of the Pacific region. He described disputes over territory and violent confrontations between the rival armed and criminal groups in the area, population control (including forced confinement as a strategy to exert control over communities), control of illegal economies that occur in the area, child recruitment, incidents of encounters with antipersonnel mines, massive displacements, and homicides, as major contributing factors to the situation in Tumaco, and similarly reflected across the Pacific sub-region of Nariño. He told Human Rights Watch that, “It is a situation that is not getting better, it is getting worse every day.”[62] And in reference to villages that are part of the Alto Mira y Frontera community council, other villages in Bajo Mira and the border with Ecuador, he said, “There is a total absence of the military and civilian state there, it does not reach the zone.”[63]

Luciana C., a resident of Alto Mira y Frontera said, “There are so many groups with an interest in the land, and that keeps us terrified.” She also recounted that the armed groups bury antipersonnel landmines in the farms and around the community.[64] Valentina Y., a widow, shared Luciana’s sentiment: “There is a lot of fear in the community. This has caused families to disintegrate. Many family members and friends have lost their lives.”[65] In this manner, the ongoing violence and threat thereof has impacted not only community members’ safety, but also the communities’ social cohesion, which is closely intertwined with their relationship with their territories.[66]

Camila Q. told Human Rights Watch about the uncertainty of living near violent armed groups that are sometimes competing for control:

There are four different armed groups. I have no idea who is a member of an armed group and who isn’t. The armed groups recruit children when parents go off to work in the companies. They use the places where we used to congregate to murder and dismember people. Less than eight months ago, they murdered a woman, left her [naked] corpse on the soccer field, and wouldn’t allow her family to pick up the body. This armed group suspected her of being in a relationship with a member of an opposing armed group. Imagine living close to people who have killed your relatives.[67]

Living near areas where armed groups operate also increases the risk of stepping on an antipersonnel landmine. Diego S., a member of the community council board, explained that people within his community are afraid to go to their farms and are enduring hunger because of concerns about detonating antipersonnel mines, which could mean injuries, the loss of limbs, or even death.[68] For example, Maria W., a mother of five, worries about the mines near her community and recounted an incident from two years ago, when a boy went after a wandering donkey and stepped on an antipersonnel landmine, requiring him to have his leg amputated.[69]

According to the Office of the High Commissioner for Peace’s Group on Action against Antipersonnel Landmines (Grupo Acción Contra Minas Antipersonales), a government agency which has recorded victims of antipersonnel mines and unexploded ordnance from 1990 to March 2023, Tumaco is the municipality with the highest number of victims, and Nariño is the state with the third highest.[70] In 2022, the office recorded four incidents in Tumaco municipality, with three in the Alto Mira y Frontera area.[71] Between the months of November 2022 and January 2023, the Human Rights Ombudsperson’s Office recorded 15 incidents in Tumaco.[72] In June, an official at the Human Rights Ombudsperson’s office told Human Rights Watch that so far in 2023 they had recorded “more than 50 accidents involving improvised explosive devices, antipersonnel mines, and unexploded ordinance. The main victims are the community councils, and one of them is the largest community council in the Pacific, Alto Mira y Frontera, which is in this area.”[73] It is unclear whether these incidents were caused by landmines recently planted by FARC dissident groups or by landmines used years earlier.[74]

Interviewees recounted how their communities became minefields. Diego S. told us that the number of landmines increased in number and proximity: “The guerrillas planted mines, the FARC left a lot, but now there are more mines planted than before. The mines are planted two, three, four meters from houses, there are mines planted near the school.”[75]

Inadequate or delayed demining efforts continue to keep people off their lands. Carlos L., a member of the community council board, said:

Alto Mira is full of mines, but we do not see a demining team in charge of this, except for some mines that the army locates and removes, because they too are sometimes affected: members of the army also fall into the minefields. The government is late in authorizing demining to enter El Alto Mira. And demining and the dialogue the president proposed are the logical steps. After the demining, we can enter our farms.[76]

Maria also described the difficulties of being caught between different armed groups:

Two groups are fighting over our community. If one group stops you, the other group accuses you of working with the first group. The groups have also restricted what we eat. The Pan-American highway cuts across our community. The group at the entrance of our community, where most of our community’s food comes through, won’t allow us to bring much food into the community because they think it’s to feed the other group, which is at the other end of the road. My sister has a store in the community, but the groups restrict her to only buy and stock products worth a total of 500,000 pesos [US$110]. My brother’s car was burned because he came home with a lot of food and groceries.[77]

Another resident recalled, “When I was a child I would fish in the river. Now it’s dangerous. You could catch a gun, a human head, or other body part, and then the armed group will come for you.”[78] These dynamics have deeply impacted not only the ability of community members to farm and feed their families, but also their psychological well-being. Daniela G. cried while she told us:

It affects me a lot because we are not free, both on a personal and family level… When I go to the farm, I never know when something might happen or what I might find there [such as antipersonnel landmines]. We have nothing to do with the conflict. We are part of the peasant community, but we can’t collect food for our families.[79]

Sofia C., a resident of Alto Mira y Frontera Community Council, described the danger from—and impunity of—the armed groups:

We are in the middle of violence. The armed groups bury antipersonnel landmines in the area. Many times, we go to the farm and there are dead bodies there. People we know leave their homes and do not return. These groups want us out; they came to take over our territory. The authorities ignore us, we disappear, and they still do nothing.[80]

People feel forced to move out of their communities, particularly because of the armed conflict and ongoing violence.[81] Ana P., a 55-year-old woman, expressed a willingness to stay until she is threatened:

We are not sure if we should stay or leave the territory. I stay because the armed groups haven’t threatened me to leave. If they tell me that I have five minutes to leave, I will be gone before five minutes.[82]

Maria W., a 40-year-old woman, said, “Eventually, every person tries to get out of the community.”[83]

Child Recruitment

Many women said they left the community with their children for fear that they would be recruited into armed groups. Due to gender roles and norms within families, women are usually the primary caregivers, with direct responsibility for taking care of and protecting the children. Daniela G. took her three sons out of school because the armed groups were recruiting children at that time.[84] Valentina Y., whose son is only 3 years old, is afraid he will be recruited in the future.[85]

Since the government’s signing of the 2016 peace accord about 990 children and adolescents under age 18 have been recorded in the Victims registry as victims of recruitment in armed groups as a result of the armed conflict and ongoing violence to date, and Tumaco is the municipality with the second highest number of recorded cases of child recruitment.[86] A study conducted by the Victims Unit on children and adolescents involved in armed groups found that 50 percent of children recruited in Tumaco municipality indicated that they were persuaded to join with offers of benefits and financial remuneration, while 26 percent joined due to physical or verbal threats.[87]

Armed groups do not always use coercion, threats, or other forceful means to recruit children, according to community leaders. Instead, children typically decide to join due to social pressures or economic hardship.[88] Residents in Alto Mira y Frontera said that lack of opportunities enables armed groups to recruit children in the community. Regina V. said, “There is no employment, but the armed groups will pay, so the youth turn to picking up guns.”[89] Conclusions from the Victims Unit’s study reflect these views stating that statements from respondents they interviewed “show that armed groups use deception and take advantage of the economic needs of their victims, showing themselves as a way to obtain status and improve their quality of life.… intervention is required by the national government to address the lack of basic services and rights necessary for the development of the population.”[90]

Economic and Livelihood Implications, Especially for Women and Girls

Due to insecurity and the volatile situation in their communities, community members who own farms within the community council territory feel discouraged from farming and avoid investing resources in expanding their farms and diversifying their production. Valentina Y., a widow and mother, expressed her fear:

The situation is very complicated now. There is a lot of fighting over territory, and it is difficult to access our land. If I manage to get a bank loan and the situation gets complicated again, I must run away again and leave everything.[91]

With restricted access to their farmland, community members whose livelihoods depend on agriculture have to look for other options to survive. With loss of access to farmland, women farmers and those whose livelihoods depend on land as their main source of income, particularly in rural areas where discriminatory stereotypes related to gender roles are pronounced,[92] face hunger and increased poverty, which contributes to higher inequality.

Economic difficulties may also lead to women and girls moving to Tumaco to engage in sex work, and end up facing a potential risk of sexual exploitation and abuse. According to Catalina R., at the time the only female member of the Alto Mira y Frontera council board:[93]

Women depend solely on agriculture to feed their families. Now, we can’t get into some areas of our territory. Women are fighters but are struggling. Women must do something else they don’t want to do. Some women turn to prostitution. They do it because they are forced to do it to survive, to take care of their children, but then they are further stigmatized by other community members.[94]

However, some women may choose sex work as the most viable option when faced with less economically advantageous courses of action.[95] Community members described alternatives, like shrimp peeling and domestic work such as laundry or cleaning of homes, as less stable and lucrative, and sand mining – where sand is removed from the river delta, and the ocean bed for use in construction – as riskier, especially given the context of violence.

III. Afro-descendant Women’s Unequal Land Access in Alto Mira y Frontera

Land is always in the names of the men, and men own more than women even though women help equally with farming and working on the land.

— Paola R., Tumaco, July 2022.[96]

Afro-descendant women suffer distinctive challenges not only because they bear the brunt of impacts stemming from having less land than male counterparts, but also exist in highly patriarchal traditional societies in the first instance.

The state does not collect statistical data disaggregated by gender on the distribution of land within Afro-descendant communities, particularly with collective title.[97] However, based on non-government sources, it appears that ethnic minority women, including Afro-descendant women, have the least access to land generally.[98] Interviewees from Alto Mira y Frontera and other Afro-descendant communities said patriarchal attitudes and machismo contribute to the disparities in access between Afro-descendant men and women.[99]

Women’s Status and Participation in Representative Bodies in the Community Council

Interviewees, both women and men, identified machismo within their families, collectives, and the community councils as a challenge to women’s equal rights to land.

Under the law regulating the territory of Afro-descendant people, a community may set up a community council as its governance structure.[100] That council, in turn, is composed of a general assembly and an elected board.[101] The general assembly, which is the “maximum authority” of the council, is “made up of persons recognized by” the council in accordance with its laws and systems. Decisions at the general assembly are made “preferably by consensus,” and if not possible by the “majority of the attendees.”[102] The community council board is the “directing, coordinating, executing and internal administration authority of the community” and its members are elected by the general assembly.[103] Board members have a term of three years, except when their mandate is revoked using the laws of the assembly, and can be re-elected once consecutively.[104] The board “must be representative and will be shaped taking into account the particularities of each black community, its structures of authority, and their social organization.”[105]

The Community Council of Alto Mira y Frontera has 16 elected board members. In July 2022, there was only one female board member; as of November 2022, there were three.[106] Based on their own census, the council has a total of 4,594 members.[107] Residents said that few women are involved in governing within the community council board and men generally have more power in decision making while women are relegated to more subservient roles. According to some male board members, there are multiple reasons for the low female representation on the board, including machismo, how it reinforces strict gender roles, and the precarious insecurity of their community due to surrounding violence and armed groups.[108]

Patriarchal notions are prevalent in Alto Mira y Frontera, Tumaco, as explained by Camila Q.:

In the family, men will choose the best lands and leave the rest—the less productive lands—to women. There are clear gender roles … on what men do and what women do. In the community, there is no conception that as a woman, you can take part in making decisions about the land. The men refused to have a young woman be president of the council. They say women must dedicate themselves to the household…. The governing board should act together alongside members of the territory, but it ends up being top-down and not bottom-up. The participation of women is not seen in the governance board. The voice of men will always be the final decision and not the voice of women within the territory, which is never heard.[109]

Catalina R., who is a member of the community board, said women have a chance to participate in the General Assembly, if they want to.[110] But research shows that meaningful participation requires participants to believe their feedback will be taken seriously.[111] Discriminatory social norms and gender roles may also inhibit women from participating in community consultations or accessing information relevant to their livelihoods and roles. For example, family caregiving responsibilities that fall disproportionately on women and girls may impede their participation in community discussions.[112] Mateo C., a member of the community board of Alto Mira y Frontera, said:

Time is another obstacle. Our families are usually large, the minimum household is two, three children, four, even five, six, seven, small children, when will women have time left to participate? They have nowhere to leave the children, especially with the problems that exist here. They can’t leave the children and dedicate themselves to other things. So, it is always the man who comes out.[113]

Violence against social leaders is also a huge deterrent, generally and particularly for women. Board members explained that at one point, the previous board had eight female members, but this was unusual and did not last long because of the insecurity, violence, and armed groups targeting community leaders. Luis M., a board member, attributed the reduction in female board members to women’s fear of being targeted as community leaders. He told us that armed groups killed a member of the previous board and displaced the community for about a year. To better ensure their safety, he said that “six members of the previous board and three members of the current board have some type of protection scheme,”[114] referring to state-provided security measures such as guards.

Board members said they want a more equitable representation of women on the board, which they believed could be possible if the government guaranteed the security of leaders, provided training, and provided services to support women who want to get involved, including a safe place to leave their children.[115] Mateo C. stressed the last point as “the most fundamental,” saying that “women do not participate because they have nowhere to leave their children.”[116] Catalina R., also thought that women needed and would benefit from more support, including internally from leadership, to be comfortable speaking in public fora.[117]

Unequal Land Distribution, Reinforced by Patriarchal Norms and Gender Roles

Colombian law provides that community council boards should establish administration and management mechanisms that ensure equity and justice in the recognition and assignment of land to families.[118] However, interviewees in Alto Mira y Frontera described inequitable distribution of land, particularly impacting women.

Some interviewees reported that the community has maintained disparities in land holdings between women and men from before it was issued collective title because it has not reallocated land across members to address inequities, which would modify the gender gap in terms of access to land within the collective.

For example, Camila Q. said:

Our land is catalogued as community land. But in the beginning, the land was not divided among the families equally. Everyone thought the production on these lands would be for the whole community, but in the end, it wasn’t like that…[119]

Some interviewees viewed the gender composition of the executives of the community council as an important determinant of the distribution of land between women and men.[120] Alejandra H., a 56-year-old woman, told Human Rights Watch that women simply lack the same opportunities as men to obtain land due to the male-dominated community council boards and gender power dynamics.[121]

According to some male members of the council’s board, the distribution of land is based on who occupied and used it before the government issued documents recognizing the collective title in 1993.[122] Other research has found that it is more common in rural areas for men to appear as landowners on land ownership certificates, a result of persistent gender stereotypes.[123] Since 1993, there has not been a reallocation of land,[124] leaving most land in the hands of men.

Mateo C. explained that:

80 percent of the land belongs to men and 20 percent to women. When I say 20 percent is owned by a woman, I mean women heads of the family who are single and have also worked their lands. The 80 percent that belongs to men is tied to their families. But if a formal certificate is given, it is given to the husband. For example, I, [Mateo C.], I have 10 hectares, the certificate comes out in my name. The document does not mention a wife or children. In other words, this documentation does not establish co-ownership, but rather that it belongs to a person, in this case the man and his family nucleus.[125]

He concluded that women cannot access land within the community council because there is no available land to reallocate: “That 20 percent [owned by single women heads of household] was achieved at that time when there was still land to expand. Available land is controlled by armed groups. We cannot go and fight against those people. The government has an obligation and the duty to correct this.”[126]

Today with the scarcity of available land, single women heads-of-household may be ignored in land considerations. Other residents that if a woman is a single head-of-household, she often faces even more challenges in getting an equitable share. Luisa A., a 58-year-old woman, said:

When you are a woman with no man at your side, you are not considered. You are asked questions like: ‘If there’s no man, who will work the land?’ ‘Who will make decisions related to the land?’ We are discriminated against by men because of high machismo, resulting in the unequal distribution of land between men and women.[127]

Ana P. noted the scale of this problem and, like Luisa, the role of machismo: “There are so many single-headed household mothers who have no land. If the man leaves [the woman], he leaves with land and the woman is left without land due to the machismo in our society.”[128]

Community members said that inequality in how much land men own compared to women is further compounded by discriminatory traditional inheritance practices, with sons—not daughters—inheriting more from their parents.[129] Weak implementation of policies, insufficient capacity to enforce laws, especially in rural areas, and poor access to legal services and a lack of understanding of laws within communities and households – and by women themselves – further compound the problem.[130] Unequal inheritance practices perpetuate the subordination of women to men and contribute to violence against women.[131]

Also, some women interviewees reported experiencing intense pressures from their husbands to sell their rights to use land to another community member whenever a financial problem arises. Ana P. said:

This is economic violence! When [a husband] needs fast money, his immediate reaction is to ask the woman to sell her land. When there is a problem with his motorcycle, he wants me to sell some part of my land. I keep saying no!

There are many of us like this, some sell, some ask [Catalina R., Alto Mira y Frontera council’s only female board member] to intervene. But she can’t be there all the time.[132]

Gonzalo V., a Black psychologist from Valle del Cauca, agreed with the women’s descriptions of machismo, telling Human Rights Watch that “We Black men in the Pacific have a lot of machismo.” He added that, while the government assumes that women’s land access within collectives are protected, in reality, communities do not guarantee equal access to land between men and women.[133]

Colombia has laws protecting women’s right to land, including in inheritance, matrimonial property – community in property, with equal rights to purchasing and owning land, and protections from violence.[134] In practice, discriminatory traditional and societal norms, lack of legal awareness, and barriers to accessing justice, persist, and interfere with how people comply with these laws, and their effectiveness, particularly at local levels.[135] The government should take comprehensive steps targeting these issues, as well as the presence of armed groups and situation of violence in the area.

IV. Afro-descendants’ Ongoing Displacement, Tumaco, Nariño

You get used to living in this state of [limbo]. I’m resigned to this life.

— Andrea E., Tumaco, July 2022.[136]

While people in rural and under-resourced areas voluntarily migrate out to better-resourced urban areas to access public services, millions of people in Colombia have been—and remain—forcibly displaced, awaiting restitution in urban and peri-urban areas.[137] Several million people have been forcibly displaced during Colombia’s armed conflict,[138] and when displacement due to ongoing violence is included, the number is more than 8.3 million by official estimates.[139] According to an officer in the Human Rights ombudsperson’s office in Tumaco, the number of events of massive displacements had been increasing between 2018 – 2022.[140] In 2022, more than 7500 people were forcibly displaced from their homes in Tumaco in 12 incidents of “massive displacement” (defined as the displacement of 50 or more people or 10 or more families in a single incident through the use of violence.[141] On January 29, 2023, clashes between armed groups forced 40 people (22 families) to flee their village of El Playón in the Alto Mira y Frontera community council to the municipality of Tumaco.[142] Luis M. explained how this made Alcuán, a town overlooking the Mira River, too dangerous to live in: “It’s like a ghost town…. The armed groups watch the houses. No way to get close because they are always looking. There are mines everywhere. I don’t know how anybody can live there.”[143]

Processes related to the restitution of collective lands are slow, mainly due to poor coordination within the institutional framework, insufficient resourcing of the Land Restitution Unit, including its directorates, and security challenges, among other factors.[144] To illustrate the scale of the issue, since the passage of the Victims and Land Restitution Law 1448 of 2011, which aims to restore millions of hectares of stolen and abandoned land to internally displaced Colombians and provide reparations to victims of human rights violations related to the armed conflict, about 148 Afro-descendant community councils have requested the restitution of territorial rights.[145] However, as of April 30, 2022, there had only been 24 collective restitution decisions, of which only five were for Afro-descendant communities.[146]

Prolonged Displacement in the Cities

Due to their fear of violence or inability to safely return and repossess their land, some displaced individuals and families have lived near or in Tumaco town, far away from their original homes, for decades.

In 2013, Human Rights Watch documented major obstacles to the effective implementation of land restitution regulation. Internally displaced people who sought to recover land through the Victims Law and other restitution mechanisms faced widespread abuses tied to their efforts, including killings, new incidents of forced displacement, and death threats.[147] Almost a decade later interviewees still face challenges in returning to their land.

Internally displaced people have grown older, and some have even died,[148] while waiting for the slow process of restitution to conclude.[149] Lina G., a 65-year-old mother of six, whose husband was killed during the violence and whose son was disappeared, has been displaced since 2006.[150] When she and her children tried to return to her land in 2010, armed groups threatened her, and they fled. She has not tried again since. A government official in the Agencia de Renovacion del Territorio said, “If single female head of household chooses the individual route and petitions for land restitution, it is not an easy process. When they encounter difficulties or challenges during the process, they stop and focus on surviving.”[151]

Meanwhile, those who were children or young adults at the beginning of the family’s displacement have grown up in with these challenges. Gloria U., a 29-year-old with a baby, was displaced more than 10 years ago, and her parents registered as victims of the armed conflict 10 years ago. She contrasted the quality of her pre- and post-displacement life:

Life was better before displacement. We didn’t have to think too much about food, food was always available. But it’s different in town. My parents must look for jobs. My mother washes clothes in the river, and my father does various jobs in different offices to make a living. I must try any way to survive…. A lot of young women are in this same situation with families displaced, parents struggling, and you must do whatever you can to survive.[152]

Residents displaced from Alto Mira y Frontera and scattered across different neighborhoods in Tumaco told Human Rights Watch that authorities have failed to curb the violence by armed groups, provide the services needed to support internally displaced persons during their displacement, and return them to their land or provide suitable alternatives within a reasonable timeframe. Laura A., a 54-year-old woman, recounted the challenges faced by displaced people and the absence of government assistance:

About one kilometer from Chilbi community, people have been displaced because different armed groups are trying to claim the area. Two to three weeks ago, a lot of people moved to Pasto and other places. The government does nothing. Military forces that should go there [instead] stay in Tumaco.[153]

According to Mateo C., another challenge for displaced communities is accessing relevant information on where and how to obtain assistance while displaced: “I imagine that the government does have guidance on type of displacement and where to go for help. But people don’t know.”[154] In reality, there are a number of government offices involved in providing assistance: the mayor’s office provides humanitarian support to displaced individuals, the committee for transitional justice provides assistance for victims of massive displacements, and these people can also register as victims with the Human Rights Ombudsperson’s Office, the Inspector-General’s Office, the local personería (a municipal human rights body), or with the Unit for the Attention and Integral Reparation to the Victims (Victims Unit). An official of the Human Rights Ombudsperson’s Office said that victims need help with accessing the necessary benefits, and though there are benefits, these are “not enough because the demand overwhelms the services that are available.”[155]

Racial Discrimination and Challenges for Displaced Afro-descendants

Despite legal protections in place over the past two decades to safeguard the rights of Afro-descendant people, discrimination is still prevalent.[156] According to the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, the persistent structural and historical discrimination faced by members of Indigenous groups and Afro-descendant communities is reflected in high levels of poverty and social exclusion as compared with the rest of the population, and adversely affects their effective enjoyment of many of their civil, cultural, economic, political, and social rights, including their rights to work, health, education, and political participation.[157] More recently, government studies have confirmed the persistence of inequality and discrimination of Afro-descendants within their society.[158]

In some cases, these people have experienced multiple displacement events over decades, leading to a deterioration of living standards as these internally displaced people have lost access to land, homes, assets, and livelihoods. Separated from their traditional means of subsistence, displaced Afro-descendants in cities must insert themselves into an already tight labor market in a racially discriminatory environment.[159] According to data from DANE, the unemployment rate among Afro-descendant women (21.5 percent) is more than twice as high as the unemployment rate among Afro-descendant men (10.5 percent) and higher than the national average for women (15.4 percent) in April 2022.[160] Structural discrimination – macro-level conditions, including inadequate legal protections, and persistent failure to effectively implement existing policies – fosters obstacles to the labor inclusion of these population groups and limits the types of employment they can secure.[161] Women like Juliana Q., who was displaced more than a decade ago, take whatever is available: “I will take any job I can find: peeling shrimp, cleaning and doing other manual work in people’s homes, or loading bags of rice,” Juliana said. [162]

A 2016 study found that displacement decreased men’s wages by 6 to 22 percent and women’s by 17 to 37 per cent compared to their non-displaced peers.[163] For Afro-descendant women, the challenges are even worse, with their race intersecting with gender and social class to compound the discrimination they confront.[164] Even with some progress,[165] Afro-descendant women and girls still face significant barriers to public participation and upward social mobility, including limited access to education, exclusion from the labor market (resulting in many entering domestic service or labor without adequate protections for their rights), early childbearing and high teen pregnancy rates, and physical violence against them and their children.[166]

V. International Human Rights Standards

International human rights instruments protect land rights, including the rights of individuals and communities with customary land tenure.[167] The Inter-American human rights system recognizes and protects Afro-descendant collective rights to land based on a unique cultural relationship with it that qualifies them as “tribal peoples.”[168] Colombia’s national legal framework, even with some weaknesses, is forthrightly progressive in protecting the rights of Afro-descendant people to own and manage land as collective territories.[169]

International human rights law protects against discrimination, including on the basis of sex, with respect to property, and related to access to, use of and control over land.[170] Colombia has ratified all current international treaties on human rights and women’s rights and has made significant progress towards drafting laws that promote gender equality and protect the human rights of women. However, more needs to be done to ensure women have equal access to land and other natural resources in rural areas, and within racial/ethnic communities.[171] The community councils should monitor and evaluate access to land within their collectives; to avoid missed opportunities to remedy problems, these efforts should not be gender-neutral. The government should assist by adjusting support packages that could substantively help women who have access to relatively less land for their use than men do, or no land at all, in affected Afro-descendant communities.

The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights requires states to eliminate all forms of discrimination and to ensure substantive equality.[172] The Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights’ has clarified the specific obligations of governments to protect land access, use, and control under the covenant, with specific reference to the entitlements of women, local and Indigenous communities.[173] The committee has reinforced the importance secure access to land has on the enjoyment of the rights to adequate food and adequate housing, among other related rights. The covenant:

requires that States adopt legislative, administrative, budgetary and other measures and establish effective remedies aimed at the full enjoyment of the rights under the Covenant relating to land, including the access to, use of and control over land. States parties shall facilitate secure, equitable and sustainable access to, use of and control over land for those who depend on land to realize their economic, social and cultural rights… States parties shall also recognize the social, cultural, spiritual, economic, environmental and political value of land for communities with customary tenure systems and shall respect existing forms of self-governance of land. Traditional institutions for collective tenure systems shall ensure the meaningful participation of all members, including women and young people, in decisions regarding the distribution of user rights.[174]

The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) prohibits all forms of discrimination,[175] and the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women has consistently identified patterns of discrimination faced by Afro-descendant women and girls in the exercise of their human rights.[176] States should also ensure the rights of women and girls, including Afro-descendant women, to effective and equal participation in decision making and to consultation, in and through their own representative institutions.[177]

CEDAW specifically requires that states parties “take all appropriate measures: (a) To modify the social and cultural patterns of conduct of men and women, with a view to achieving the elimination of prejudices and customary and all other practices which are based on the idea of the inferiority or the superiority of either of the sexes or on stereotyped roles for men and women”[178] The convention also requires governments to “take all appropriate measures to eliminate discrimination against women in rural areas. … and ensure to such women the right to equal treatment as men in land and agrarian reform.”[179] This applies to Afro-descendant women within and outside their community councils, and to both state and non-state actors in and outside of their collectively held territories.

Barriers to equal access to economic opportunities, including land rights in Colombia, are a significant obstacle for women’s social and economic advancement as well as their ability to take part in public affairs Specific to women in rural areas, the committee recommends that states address unequal power relations between women and men, including in decision-making and political processes at the community level, and remove barriers to rural women’s participation in community life.[180] It urges states to “pay special attention to customary systems, which often govern land management, administration and transfer, in particular in rural areas, and ensure that they do not discriminate against rural women.”[181] To guide states on eliminating harmful practices and addressing discrimination faced by rural women, including discriminatory practices that create barriers to rural labor markets, it recommends “adopting a range of measures, including outreach and support programs, awareness-raising and media campaigns, in collaboration with traditional leaders and civil society.”[182]

The government of Colombia has put in place many initiatives aimed at securing equality on the basis of gender, race and ethnicity. However, if opportunities on accessing and using land and taking part in other economic activities, including employment, as well as meaningful and sustained assistance during displacement, are not supported as a comprehensive plan, these initiatives are not going to result in substantive equality for Afro-descendant and Indigenous women.[183]

Recommendations

To the Government of Colombia

Addressing Violence

· Prioritize the full implementation of the 2016 Peace Agreement.

· Increase efforts to improve security and protection in rural areas and areas predominantly used by Afro-descendant and Indigenous people, including by taking decisive action to demobilize armed groups and prevent human rights violations by strengthening rights-respecting criminal investigations and local access to justice.

· Explore alternative approaches to drug policy that would reduce the profitability of the illegal drug trade and by increasing social and economic opportunities in remote areas of the country.

· Adopt measures to reform and strengthen prevention and protection mechanisms, including by ensuring that these (1) are adequately resourced; (2) have a gender perspective and incorporate a differentiated approach, with priority on preventative as well as reactive measures; (3) are developed and implemented with the active participation of the affected communities; and (4) are in line with international standards, including ILO Convention 169 and the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People.

· Increase efforts to carry out demining in Alto Mira y Frontera, Nariño and other parts of Colombia heavily affected by anti-personnel landmines.

· Strengthen the capacities of the government’s civilian institutions, including the Ombudsperson’s Office, in rural and marginalized regions to respond more effectively to the humanitarian situation, monitor and report on the human rights situation, and act as a deterrent to violations.

· Accelerate access to land, including through reforming Law 160 on agrarian reform, to ensure that these communities can effectively access, use, and control their land and enjoy their economic, social, and cultural rights.

Preventing and Mitigating Child Recruitment

· Strengthen measures to prevent child recruitment, including by designing a strategy to re-enroll children who dropped out of school during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Assistance During Displacement

· Take steps to accelerate the delivery of humanitarian assistance to communities and individuals that have been recently displaced, including by increasing funding in low-income municipalities that receive high numbers of displaced people.

· Develop and implement a strategy to prioritize emergency assistance to vulnerable communities, including Afro-Colombian and Indigenous communities.

· Develop and implement a strategy to prioritize comprehensive reparations for victims of displacement, including during the armed conflict, starting with victims of the most serious human rights violations.

Accessing Land, Restitution

· Accelerate land restitution, including through administrative proceedings, to ensure that displaced individuals and communities can return and rebuild their lives.

· Establish and implement a strategy to prioritize the restitution of land to the most vulnerable communities, such as Afro-descendant and Indigenous women.

· Ensure that the state bodies responsible for implementing the land restitution process effectively coordinate and co-operate with each other and are adequately resourced to increase information sharing, minimize inaccuracies, and ensure expediency.

· Encourage the equal participation of women, including Afro-descendant women, in governance and decision-making structures within their communities.

On Non-Discrimination

· Prioritize the implementation of the national care system in rural communities where Afro-descendant and Indigenous women live, so they can make the time to meaningfully participate in decision making processes in their communities.

· Support community councils to ensure that women have comparable access to collective land as their male counterparts.

To Afro-descendant Community Councils

· Implement campaigns to raise awareness about the importance of Afro-descendant women’s participation in community decision making.

· Strengthen Afro-descendant community council structures, including by introducing additional funds that are conditional to women’s participation.

To Donor Governments and Multilateral Bodies

· Support the government in taking steps to curb the violence by armed and criminal groups especially in rural areas where Afro-descendant, Indigenous, and peasant communities are disproportionately impacted, including by providing assistance to strengthen rights-respecting criminal investigations and local justice.

· Support the government’s efforts to provide humanitarian assistance and accelerate land restitution and return policies.

· Support the government’s policies on gender mainstreaming, particularly as they apply to Afro-descendant communities and Afro-descendant women’s participation in governance and decision-making structures.

· Provide support to raise awareness through radio and televised programming and other media campaigns that aim to increase awareness of women’s rights, especially rights of Afro-descendant women and girls, and empower women to exercise them.

Acknowledgments

This report was researched and written by Juliana Nnoko-Mewanu, senior researcher on women and land at Human Rights Watch. Johan Cuesta, consultant, provided research support and assistance. Regina Tames, deputy director, and Macarena Sáez, executive director, in the Women’s Rights division, Juanita Goebertus Estrada, director, and Juan Pappier, acting deputy director, in the Americas division, and Nathalye Cotrino Villareal, researcher in the Crisis and Conflict division, edited the report. Michael Bochenek, senior legal advisor, conducted legal review. Maria McFarland Sánchez-Moreno, acting deputy Program director, conducted program review. Sylvain Aubry, deputy director, in the Economic Justice and Rights division, Margaret Wurth, senior researcher in the Children’s Rights divisions, and Mark Hiznay, associate director, in the Arms division provided specialist reviews. Susanné Bergsten, senior coordinator in the Women’s Rights division provided production assistance for the publication of this report. Report production was done by Travis Carr, publications officer. The report was translated into Spanish by Gabriela Haymes and edited by Claudia Núñez and Stephanie Lustig.

We are especially grateful for the guidance and generous support provided by ILEX Acción Jurídica, La Ruta Pacifica de las Mujeres and other Colombian NGOs.

We wish to express our gratitude to all of those who spoke with us during this research, and most of all, to the community members of Alto Mira y Frontera who shared their time, and insights with Human Rights Watch.