Summary

In recent years, news of murders and other violent acts against transgender people in the state of Tabasco, Mexico, has shaken the community. In a particularly egregious example in August 2023, the body of Karina Gómez, a trans woman from the capital, Villahermosa, was found in the Carrizal River with a concrete block tied to her feet. Underlying such violence, but largely unseen, is daily discrimination, harassment, and disparate treatment that leaves trans people feeling exposed and vulnerable.

One pernicious amplifier of such discrimination, highlighted for years by trans activists in Tabasco but still underestimated and underappreciated by authorities, is the obstacles trans people face in obtaining legal recognition of their chosen name or gender. Because of the mismatch between their lived and legal identities, they are regularly doubted and discounted in public interactions, singled out in ways that fuel social bias.

Tabasco does not have a legal gender recognition procedure for trans people, that is, a law or policy allowing them to modify their identity documents in accordance with their gender identity. In Mexico, each state has the authority to determine its laws and policies in civil, family, and registration matters in accordance with the constitution. Tabasco’s omission means that, for many trans people in the state, every juncture of daily life when documents are requested or appearance is scrutinized is fraught with the potential for violence, harassment, and humiliation. This impedes trans people from participating fully in society, effectively driving many of them into the shadows.

This joint Human Rights Watch-Community Center for Inclusion report exposes these impediments and their impact. While the discrimination trans people experience when there is a mismatch between their gender and their identity documents is multifaceted, the report focuses on socio-economic rights, the area most often emphasized by the trans people we interviewed. We found that Tabasco’s lack of legal gender recognition, often in combination with anti-trans bias, curtails people’s rights in four key areas: employment, health, education, and financial transactions.

Most trans interviewees recounted instances of employment discrimination from potential employers and in the workplace. In some cases, discriminatory treatment began after potential employers realized the interviewees were trans by looking at their documents. Some employers explicitly told trans people they would not be hired because they are transgender. Interviewees who were able to secure jobs faced harassment on the job related to their identity, and employers’ insistence on using their legal names rather than their preferred names made it difficult to maintain their employment. Some interviewees said that, due to discrimination, they pursued informal work instead of professional or other specialist work for which they had trained.

The majority of trans people we interviewed said that they experienced discrimination when they visited public and private healthcare facilities because their documents do not match their gender identity. Hospital staff regularly exposed interviewees as transgender by calling out their legal names in waiting rooms, subjecting them to onerous questioning about their identities, humiliating and at times openly mocking them. Upon realizing that patients were trans, some doctors made stigmatizing comments, provided questionable medical care, or otherwise mistreated interviewees.

Some interviewees had attended university in recent years or were currently enrolled. All of them described discriminatory treatment from professors and fellow students, including harassment, bullying, and other targeting due to the mismatch between their legal name and gender. Knowing education was a path out of the precarity trans people experience in Tabasco, most interviewees withstood the discrimination, albeit with mental health repercussions. One interviewee left university altogether because of the harassment. Many interviewees also said that harassment and bullying had been part of their primary and secondary school experience.

Interviewees also faced obstacles carrying out financial transactions due to the incongruence between their physical appearance and their identity document, hampering their economic rights and activities. Most of these challenges occurred at banks, with bank employees refusing to process transactions because they did not believe the identity documents trans people presented belonged to them. Already cut off from certain economic opportunities due to discrimination, impediments in financial transactions were especially frustrating for interviewees.

The discrimination and the resulting disadvantages that trans people experience due to a lack of legal gender recognition in Tabasco should not be occurring. In 2017, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights issued an advisory opinion in which it found that, under the American Convention on Human Rights, states have an obligation to establish simple and efficient legal gender recognition procedures based on self-identification, without invasive and pathologizing requirements. Mexico is party to the convention and recognizes the jurisdiction of the Inter-American Court.

In 2019, the Mexican Supreme Court issued a landmark ruling with clear guidelines on legal gender recognition. The court found that requiring trans people to go through a judicial proceeding to have their gender identity legally recognized violates their constitutional rights to privacy, identity, and free development of their personality. The court ruled that, in order to comply with the constitution, authorities should ensure trans people can update their legal documents through an administrative process that “meets the standards of privacy, simplicity, expeditiousness, and adequate protection of gender identity” set by the Inter-American Court. In 2022, the court expanded the right to legal gender recognition to include children and adolescents.

Twenty-one of Mexico’s thirty-two states have already done so, either through reforms passed by the state congresses or through administrative decrees enacted by the ruling government. Tabasco has done neither.

In the states such as Tabasco that do not have a procedure for gender recognition, trans people must initiate a lawsuit, known as a juicio de amparo, to seek a court order compelling the state to recognize their gender identity on the basis of the Supreme Court rulings and international law. Federal judges, bound by the 2019 Supreme Court jurisprudence, generally issue such orders, but it can be a lengthy and expensive process and requires hiring an experienced lawyer.

In a successful amparo case, the judge orders the civil registry to permanently seal a trans person’s original birth certificate–meaning it is no longer readily accessible in its information systems–and to issue an amended certificate. This new state birth certificate is necessary to request new nationally valid identification documents like a voter’s registration card, a tax number, or a passport. Very few trans people in Tabasco have availed themselves of this legal option. Interviewees told us that the process is simply too burdensome and costly, with one person describing it as a “nightmare.”

As shown by the experience of trans people elsewhere in Mexico, legal recognition of one’s identity, while it does not remove societal discrimination, effects a sea change in attitudes, those of the people one interacts with and one’s own feeling of belonging. As one trans woman in Tabasco told us:

We want [the processing of] our documentation to be quick, so that we do not have so many obstacles. It would change the perspective of looking for work. I need to work. I just want to contribute, to feel useful in society.

Another said:

Mexico is country that has the possibility to advance, and we [trans people] can contribute to the nation. We just need equality and opportunities in all areas. We have a right to progress, to experience happiness, to be accepted.

Tabasco authorities should heed the Supreme Court and urgently create an administrative gender recognition procedure. This not only will contribute to alleviating the socio-economic precarity of trans people in the state, but also will allow them to contribute more fully to society and respect their dignity. Provision of accurate identity documents for trans people signals that a government supports trans people’s basic rights, contributing to understanding and acceptance of gender diversity. In Tabasco it will also help address the root causes of the violent acts too often perpetrated against trans individuals.

Methodology

Human Rights Watch and Community Center for Inclusion conducted most of the research for this report between March 2023 and November 2023, including interviews with 30 people and review of documentary evidence, legal analysis, and a range of secondary sources. Twenty-three interviews were with transgender people in Tabasco. We also interviewed staff of four LGBT rights organizations in the state, and three human rights lawyers. In some cases, we have used pseudonyms when interviewees so requested.

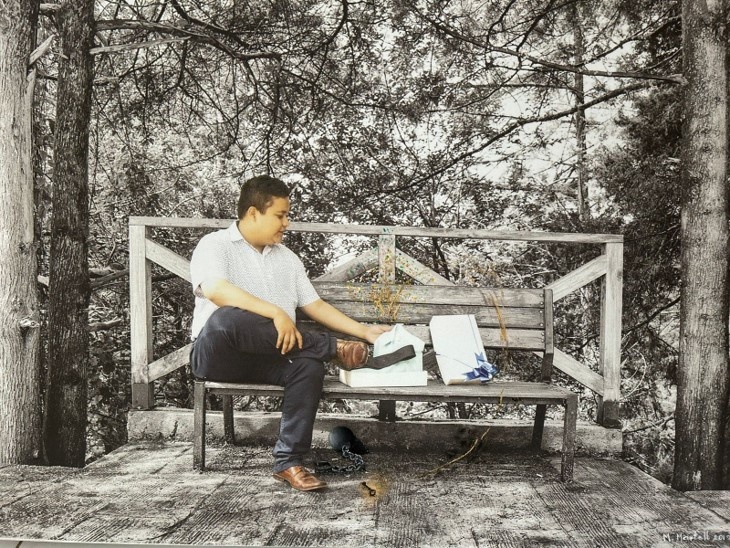

Most interviews were conducted during a research trip in Tabasco in March 2023 during which researchers travelled to Centla, Jalpa de Méndez, Tenosique, and Villahermosa. The Community Center for Inclusion, which provides social services to LGBT people across the state, identified interviewees through its network. The majority of trans interviewees were women; two were men. Interviewees included people of various socioeconomic backgrounds, including people who were unemployed.

Researchers obtained verbal informed consent from all interviewees and explained to them how their stories would be used and that they could decline to answer questions or stop the interview at any time. Human Rights Watch reimbursed public transportation fares for interviewees who traveled to meet the researchers and provided a snack or meal when interviews occurred during a mealtime. No compensation was paid to interviewees.

Human Rights Watch informed the following government offices and ministries of its preliminary findings and requested a response: Tabasco state Governor’s Office; Public Prosecutor’s Office of Tabasco; Labor Conciliation Center of the State of Tabasco; Secretary of Health; Secretary of Education. It also asked the government agencies for specific statistical information on human rights violations and any additional information they wanted to share. None of the offices provided responses.

I. LGBT Rights in Tabasco

Tabasco is one of Mexico’s poorest states. In 2022, 46.5 percent of Tabasco’s population was living in poverty, of which nearly one-quarter was living in extreme poverty.[1] These figures do not only reflect income poverty but also “ability poverty,” defined as the rate of exclusion from six social rights: education, food, health, housing, social security, and other basic household services.[2] Overall, the great majority of Tabasco’s population (80.1 percent) are deprived of at least 1 of 6 social rights included in the multidimensional poverty index and 42.8 percent by more than 3.

Nearly one-third of households in Tabasco had at least 1 victim of crime during 2020, compared to the national average of 28.4 percent, a 2021 survey by Mexico’s national statistics agency found.[3] Criminality has increased in recent years, with the state Public Prosecutor’s Office reporting some increase in reports of extortion, murder, small-scale drug dealing, violent robbery, car theft, motorbike theft, human trafficking, and rape.[4] The 2021 national survey found that 60 percent of the adult population cites insecurity as the main source of concern.[5] The survey also found that of the total number of crimes in Tabasco, only 8.6 percent were reported in 2020, compared to 10.1 percent at the national level.[6] Twenty-nine percent of respondents victims of crimes in Tabasco said that reporting a crime is a waste of time, while 13.1 percent said that they do not trust authorities.[7]

Another survey by the national statistics agency found that more than two-thirds of women and girls over 15 years of age in Tabasco have experienced violence at some point in their lives. This is roughly equivalent to the national average of 70.1 percent and represents an increase in the state since the 2016 survey.[8] In the 2021 survey, 39.6 percent of women in Tabasco reported having suffered violence in the last 12 months, compared to a national average of 42.8 percent.[9] 50 percent of women from Tabasco reported having suffered psychological violence in their lifetimes; 46 percent, sexual violence; 36.2 percent, physical violence; and 26.9 percent, economic violence or discrimination.[10] The most common situation where women face violence in Tabasco is in the context of a current or recent relationship (43.2 percent), followed by community settings (41.1 percent), educational settings (31.8 percent), the workplace (27.1 percent), and the family (11.3 percent).[11]

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Tabasco must contend with all of these human rights challenges and often face additional discrimination or violence based on their sexual orientation or gender identity.[12]

In recent years, there have been some high-profile of alleged killings of trans people in Tabasco. In August 2023, the body of Karina Gómez, a trans woman from the capital Villahermosa, was found in Carrizal River, with a concrete block tied to her feet.[13] In January 2022, the body of Dayana Karrington, a trans woman from Cárdenas, was found in a vacant lot, her face unrecognizable from the blows she received.[14] In June 2020, Gabriela Reyes’ body was found in Villahermosa with multiple bullet wounds and other physical injuries.[15] Reyes was a respected activist focused on the rights of sex workers and sexual health. No convictions have been handed down in these cases. Tabasco’s criminal code does not punish hate crimes motivated by a victim’s sexual orientation or gender identity and authorities do not compile official data on such crimes.

The Law to Prevent and Eliminate Discrimination in the State of Tabasco covers discrimination motivated by sexual orientation and gender.[16] The law establishes protections against discrimination in education, employment, health, and access to justice, and lists several instances of possible violations of civil, political, economic, social, and cultural rights. Activists have criticized the disconnect between the law’s broad protections and the reality of violence and discrimination that LGBT people live in the state. In 2009, the Tabasco Congress declared May 17 as the State Day against Discrimination and Homophobia, aligned with the commemoration of International Day Against Homophobia, Biphobia, and Transphobia.[17]

Tabasco legalized equal marriage in October 2022.[18] It was one of the last federal entities in Mexico to take the step, seven years after a 2015 Supreme Court ruling declaring same-sex marriage bans unconstitutional and putting Mexican states on notice that they needed to adopt marriage equality.[19] Lawmaker José Hernández Díaz of the Morena party introduced the bill in October 2022,[20] and it was passed that same month. Previous bills had been introduced in 2015 and 2016.[21]

In 2022, Casilda Ruiz of the Citizen Movement party introduced a bill to criminalize “conversion therapies.” The proposal seeks to add a provision to article 161 of the Criminal Code of Tabasco, to penalize with 2 to 5 years of prison to those “who promote, offer, impart, apply, force, induce, or submit to treatment, therapy, or any type of service that pretends to modify a person’s sexual orientation and/or gender identity.”[22] When governments undertake to ban conversion practices, they should recognize that criminal bans may not be sufficient in ending such practices and must be part of a more comprehensive strategy to end stigma and discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity in order to be effective. Bans that are overly broad or punitive may themselves raise concerns of necessity, proportionality, and non-discrimination.

Legal Gender Recognition in Tabasco

Authorities in Tabasco have failed to protect the right to legal gender recognition. In 2019, the Mexican Supreme Court issued a landmark ruling with clear guidelines on legal gender recognition. The court said that, in order to comply with the constitution, authorities should ensure trans people can update their legal documents through an administrative process that “meets the standards of privacy, simplicity, expeditiousness, and adequate protection of gender identity.”[23] These requirements track the standards set out by the Inter-American Court in 2017, which are binding on Mexico.[24] In 2022, the SCJN also ruled that the right to gender identity could not be denied to adolescents and other children.[25]

Tabasco authorities have failed to create a gender recognition procedure, unlike 21 other states.[26] Because of this legal omission, trans people in Tabasco who want their gender legally recognized must file a lawsuit (a juicio de amparo) to obtain a court order requiring the state to recognize their gender identity on the basis of the Supreme Court rulings and international law. Bound by Supreme Court jurisprudence, federal judges grant the injunction. However, filing the case is onerous and can be lengthy and costly.

In a successful amparo case, the judge orders the civil registry to permanently seal a trans person’s original birth certificate and to issue an amended certificate. This new state birth certificate is necessary to request new nationally valid identification documents like a voter’s registration card, a tax number, or a passport. Though an exact number not available, very few trans people are known to have filed amparo cases to have their gender legally recognized. An estimate in 2022 suggested that only around 15 individuals in Tabasco have ever gained recognition in their official documents through judicial action, while as many as 20 other cases were pending.[27] Interviewees told Human Rights Watch and Community Center for Inclusion that the process is too burdensome to do it. One trans woman who went through the process in Tabasco recounted her experience to researchers:

The amparo process was frustrating. It took eight months for them to give me a favorable response. It was exasperating. I said to myself, “Is it going to be approved?” I didn't know [civil society organizations] to ask for help. I didn’t know they [the authorities] were actually going to change my name, it was an uncertain issue. You have to defend yourself before various institutions, because of their ignorance they do not understand. There are obstacles and the process becomes longer and more tedious. They make you go around in circles. It is an [economic] expense. You have to go to the capital, give I don't know what information, wait more days. It was a nightmare.[28]

A 59-year-old trans woman from Tenosique echoed what many interviewees said:

If it were easier, I would do it [go through the legal proceeding], but it’s a hassle, too many proceedings. If I could just give them my birth certificate, I would do it, but it’s too much. I would have loved to have my documents since I was young. Now it’s late.[29]

As documented in this report, the lack of legal gender recognition in Tabasco infringes upon trans people’s socio-economic rights. These were the areas where interviewees felt the most impacted. This does not mean, however, that other areas of life are not impacted. For instance, two interviewees said public security officers scrutinized and questioned them at checkpoints because their identity documents not matching their physical appearance. Maria J., a 31-year-old trans woman from Jalapa de Méndez, described an experience on the road in 2021, during which authorities treated her differently from other passengers:

I was coming back from Ciudad del Carmen [a coastal city in neighboring Campeche state] and there was a checkpoint, where they review your documents. I was in a vehicle, in front of other passengers. They asked, “Where you are coming from? Where are you going?” They made me get out of the vehicle and interviewed me for 20 minutes. They only interviewed me, no one else. It was very uncomfortable.[30]

Dante T., a 26-year-old trans man from Villahermosa, had a similar experience at a state police checkpoint in March 2023:

If you ride a motorcycle, they always check your papers because [criminals] steal motorcycles. They asked me for my license. Because I had short hair, they didn't believe it was my photo. They made me take off my helmet. They stared at me. They let me go, but the policeman washed his hands after checking me. He washed himself with a bottle of water, as if I disgusted him. I let it pass without saying anything, but I experienced a transphobic case… I felt bad afterwards.[31]

Tabasco’s authorities should make all necessary reforms for the full legal recognition of transgender people’s gender through a simple, administrative procedure. Such full legal recognition is consistent with the state’s international, regional, and national legal obligations and can provide an important mechanism for combatting all forms of anti-trans discrimination, including in the four areas of ongoing concern detailed below, namely employment, health, education, and economic rights.

II. Right to Work

Transgender people in Tabasco face hurdles to gainful employment not faced by the general population, even when they have completed university education. Of the trans people with whom Human Rights Watch and Community Center for Inclusion spoke to, almost all had faced some form discrimination or violence in an employment context, pushing them into the informal sector, economic precarity, and the margins of society. The discrimination was often linked to incongruence between trans people’s legal name and gender, and their physical appearance. Perpetrators include potential employers, managers or supervisors, and colleagues. One interviewee summed up the feeling that many interviewees expressed about wanting to work:

Mexico is country that has the possibility to advance, and we [trans people] can contribute to the nation. We just need equality and opportunities in all areas. We have a right to progress, to experience happiness, to be accepted.[32]

Discrimination in Hiring

Interviewees reported discrimination starting with the hiring process. Juan Carlos G., a 25-year-old trans man from Centla with a degree in biology, told researchers that in January 2023 a potential employer chose not to hire him when the employer realized his legal name was feminine:

At an internet café, they were looking for people for the maintenance of the computers. I took my papers, but [the employer] changed his attitude when he saw my papers. First, he had said, “Good morning, young man. Okay, give me your documents.” Then he changed and said that he wanted men for the position. He said more seriously, “No, you are a woman.” He [physically] distanced himself from me and said, “I can’t have anyone like you working [here].”[33]

Before this incident, Juan Carlos had already experienced workplace discrimination. In August 2022, he had been hired as a teaching assistant at a private school, but the employer told him that he would never be hired as a full teacher because his gender identity would “confuse” students. Three months later he resigned due to these and other discriminatory comments from the employer.[34]

Discrimination in hiring is especially frustrating for individuals who have spent years in school studying for a specific career. Karla H., a 49-year-old trans woman from Villahermosa, told us she finished her nursing degree in 2000, graduating with honors from the Juárez Autonomous University of Tabasco (UJAT), but has been searching for a nursing job ever since. In 2020, Karla learned about a call for applications for a nursing job at the Social Security Institute of the State of Tabasco (ISSET). She applied, passed all the required tests, and was notified that she had gotten the position. She recounted the discrimination she experienced thereafter:

Human Resources told me that they would notify me of the date to go pick up the badge and sign the employment contract. I waited, but they didn’t call me, so I went [in person]….When I spoke to the head nurse, she first said that she didn’t know where my paperwork was. But then she said, “I didn’t want to tell you, but there are several problems with you. One is you look like a woman and have a man’s name. There is a discrepancy. Then I realized that you were a man dressed as a woman. How are you going to go to a bathroom? What are you going to do with your hair? What are you going to do with your breasts?”[35]

The head nurse then told her they had already hired someone else for the position.

Karla filed a complaint and said that in March 2021 a discrimination investigation was opened by the Tabasco Public Prosecutor’s Office, supported by the State Human Rights Commission. However, she said the investigation was never completed because she found it too onerous. She said that she had to seek mental health services because of the frustration of not finding nursing employment after many years of trying. “I managed to get past that stage of depression, but at 49 years of age you are no longer hirable in a hospital,” she explained.[36] She said she has tried to get jobs at hotels, pharmacies, and other businesses, but on at least five occasions employers have asked why her documents do not match her physical appearance and she ultimately did not get hired.

Samanta L., a 31-year-old trans woman from Jalpa de Méndez, expressed the frustration of being held back by her legal name and gender even after graduating with a degree in psychology in 2018:

I can’t practice my career. I graduated, but I continued working at [a retail company]…. Even when I brought photos and papers [as proof], and even when I explained I am the same person, it was always very complicated for employers.[37]

Alexandra M., a 33-year-old trans woman from Villahermosa, reported multiple incidents of discriminatory treatment when she presented documents that revealed her legal name and gender to prospective employers. In August 2022, Alexandra said that she submitted her job application documents to a clothes retailer and faced extra scrutiny because of the disparity between her appearance and her documents: “[When I met] with the human resources person, she looked at my documents, she looked at me head to toe, and said, ‘We will call you.’”[38] She never received a call.

Alexandra described another experience looking for a job at a real estate company in July 2021, where her physical appearance, her identity documents, or both may have contributed to her not being hired:

I knocked on the door. They said, “What are you looking for?” I said, “A [job] application.” They closed the door on me. I went back with an appointment. I knocked again. The moment I entered [the office], I felt the gaze. There were whispers. I introduced myself to Human Resources, and they said I needed to leave my documents to be able to apply. I gave them all [my documents]. They later called back saying I was not the “right person” [for the job].[39]

Discrimination in the Workplace

Interviewees explained that discrimination did not just occur in hiring, but also when they were already employed. Often, this manifested itself as harassment related to interviewees’ legal gender or name. Alexandra recounted the bullying she experienced when she worked at a telecommunications retailer in Villahermosa between November 2022 and January 2023:

My co-workers made fun of me, asking what genitals I had. They did cruel things to me. They didn’t allow me to be in sales [a public-facing job]. They called me “the transformer” or said, “Here comes that weirdo.”[40]

Sandra R., a 42-year-old trans woman from Villahermosa, told researchers that she has experienced discrimination from colleagues at the Federal Electricity Commission (CFE), the state-owned electric company, where she has been working as a cleaner for three years. The discrimination was particularly acute within the first year of her employment:

Colleagues would say things like, “Why are you here?” There was mocking, comments, harassment. Someone who worked there, wrote on the [office] blackboard, “You’re a faggot” or “You think you’re a woman?” Others started doing it too. I would arrive [at work] and see it.[41]

Sandra explained that, while she tidied the office, she would often find notes addressed to her that said things like, “Don’t touch my desk under any circumstances,” which she interpreted as transphobic rejections of her.[42] She also recounted that during the first few months of her time working at CFE, she was cleaning the bathroom when a worker came in and sexually assaulted her:

He lowered his zipper and said that I had to perform oral sex on him because he wanted it and since I am like I am [transgender] I had to do it. I completely refused.[43]

Sandra said that she did not report the incident to her superiors because the assailant said, “it’s my word against yours,” and since she was relatively new at the company, she thought no one would believe her. “It is very difficult to find jobs for [trans] people like us, so I kept quiet [about the harassment],” she explained.[44]

Sandra told researchers that she thinks that having legal documents that reflect her gender identity would alleviate some of the discrimination in the workplace because, she said, “I could work as I am,” that is, as a woman. She said she has considered finding a job that would allow her to work from home in order to “not expose” herself to discrimination.

For Luna G., a 20-year-old trans woman from Villahermosa, transphobic incidents also meant she had to keep her identity concealed at work. She told researchers that between April 2021 and March 2022, she worked at a grocery store chain but did not feel comfortable revealing her gender identity. Her boss, who suspected that she was trans, asked her not to transition while she was working there. Luna left this job and began looking for another job in December 2022. She explained some of the challenges in securing a job as a trans person due to identity documents, as well as subsequent discrimination in the workplace:

I had several interviews…. [The employer] gave me the explanation that “the position is no longer vacant.” But it was weird because he said it after reading my deadname. [45]

Luna was eventually able to get a job at a restaurant through personal connections, but even informal support did not protect her from a harmful workplace. She said:

Getting my current job was not difficult because I knew the owner. But now that I’m working, the boss misgenders me. She is disrespectful, intolerant, reckless [with me].[46]

Luna told researchers that she thinks her employer purposely gives her more work than other colleagues. She said that she has been diagnosed with anxiety attacks due to the stress caused by the extra workload. However, she does not want to complain, in part because of her vulnerability as a trans woman in the job market:

My brain says it’s not okay for them to push me so hard. But I have to take care of this job because there are no other options. I feel like I can’t complain, because I feel like they're going to fire me.[47]

Some employers have required trans people to change their physical appearance to match their legal name and gender, though even complying has not always helped to prevent discrimination. Ángel P., a 20-year-old trans woman from Villahermosa, told researchers that in order to secure employment at a telecommunications company as a products promotor in 2022, the employer said she had to cut her hair to appear more masculine. “When I applied, the manager told me that I couldn’t go to work like that [with long hair], that I would have to change my clothes,” she said.[48]

Even after she cut her hair and was working at the company, Ángel said she never felt accepted, especially since the manager and other colleagues frequently asked her questions about her sexuality: “If they suspected you were from the LGBT community, they asked questions. ‘Do you have a girlfriend?’ I limited myself to basic responses.”[49] Ángel left the job after three months due to the harassment.

Alicia S., a 60-year-old trans woman from Tenosique, was also asked to change her physical appearance. She explained that she worked as an accounting secretary in the municipality in 2013. For her employment identity card, the employer made her cut her hair and not wear earrings. She said that she felt “strange” doing this but wanted the job, so she complied with the requirement even though she would have preferred to maintain her feminine appearance.[50] Alicia now works independently as a decorator and artisan, in part because of discrimination in the job market. She said that her business generally goes well, although sometimes potential clients express unwillingness to work with her due to her gender identity.[51]

Samanta L., the psychology graduate mentioned above, said that she experienced harassment at a retail company where she worked on account of her legal name. This led to her leaving the job in 2019 after eight years working there:

I had a conflict with a colleague. He started addressing me by my legal first name. He spoke to me on the [company] radio or on the phone and always emphasized my legal name. It got to the point where he was calling me that during the entire work shift. I got tired of the harassment and went to human resources.[52]

Samanta did not wait for the situation to improve and left her job shortly after making the complaint. When researchers spoke with her, she had been running an informal beauty salon from her home for two years.

Other interviewees that described related discrimination in the workplace included Guadalupe J., a 36-year-old trans woman from Villahermosa; Mati López, a 38-year-old trans woman from Cunduacán; and Isabel H., a trans woman from Nacajuca.[53]

Pushed to the Margins

For some interviewees, discrimination pushed them to informal, unwanted, or risky work, or made them fearful of even trying to gain employment. Paola L., a 56-year-old trans woman from Villahermosa who runs her own hair salon, said discrimination in the workforce drives many trans people to work independently to get by.[54]

Patricia E., a 52-year-old trans woman from Villahermosa, said that she never tried to gain formal employment because she did not think it was an option because she is trans.[55] She said that she practiced sex work, despite the dangers that it entails. Patricia said that in 2007 she was drugged by a client but continued working out of necessity.[56]

Alexandra, the 33-year-old trans woman from Villahermosa mentioned above, told researchers that due to transphobic discrimination in the labor market, she also earned money through sex work for some years. “I didn’t like, but I had to do it because I didn’t have a choice,” she said.[57]

A few interviewees decided to stop searching for work. Analisa C., a 48-year-old trans woman from Villahermosa, told researchers that she previously tried to gain employment at local bars but she believes that she was never hired due to prejudices against trans women. She currently works taking care of her aunt at home, though this is not remunerated.[58] Similarly, Melissa A., a 48-year-old trans woman from Villahermosa, said she primarily focuses on being a homemaker. Licha C., a 68-year-old trans woman from Tenosique, works helping her sister with whatever she needs around the house and beyond.[59]

Mia C., a 41-year-old trans woman originally from Villahermosa, said that she has been reticent about looking for a job since moving back to the city during the pandemic. When researchers spoke to her, she said that, due to labor discrimination, she was planning to move back to Mexico City, where she had lived for many years. “I haven’t tried to get a job here [in Tabasco], it’s easier in Mexico City. I want to work as Mia and I don’t want to feel bad about it,” she said.[60]

Positive Experiences

While most interviewees expressed obstacles in the labor market, some recounted experiences of respect or acceptance. Juan Carlos, the biology graduate mentioned earlier, got a job as veterinary assistant in February 2023 and was working there when we interviewed him. He said that this employer asked him, “How would you like to be called?” from the start and has treated him with respect.[61]

María J., a 31-year-old trans woman from Jalapa de Méndez, has been employed in the administrative office of a multinational retail corporation for about 10 years and has not experienced discrimination in the workplace. She did note that she got the job through a family connection. “I believe that at another business, I would have gotten rejected due to my gender identity.”[62]

Ángel, the 20-year-old trans woman from Villahermosa who quit her job at telecommunications company due to harassment, eventually got a job at the same multinational retail corporation as María, although in the state’s capital. For her it has been a positive experience since “it’s a more inclusive company, and people from the LGBT community have good positions there, and the company trains its workers well and they address LGBT issues.”[63] Ángel says, however, that it still bothers her that her legal documents do not reflect her gender identity and wonders what will happen if she ever looks for another job.

Sandra R., the trans woman employed at CFE, said that on one occasion in the first months of her employment, the office boss heard a colleague refer to her as “faggot” and told the worker that he had to “respect him [sic],” that he would not tolerate such language, and that if Sandra made him uncomfortable “avoiding him [sic] is sufficient.” This was the only case of a supervisor addressing discrimination that researchers were able to document.

Many interviewees believe that gender recognition would go a long way to improve their employment situations. As Karla, the nurse from Villahermosa, said at the end of our interview:

Recognition [of legal gender] should be automatic. We want [the processing of] our documentation to be quick, so that we do not have so many obstacles. It would change the perspective of looking for work. I need to work. I just want to contribute, to feel useful in society.[64]

II. Right to Health

Like most people in Tabasco, transgender people must contend with the structural shortcomings of public healthcare. However, trans people also face additional barriers to access due to discrimination based on gender identity. People that Human Rights Watch and Community Center for Inclusion interviewed said that the discrimination manifested itself in two main ways: the exposure of their gender identity in clinics, often accompanied by humiliating and invasive questioning, and discriminatory medical care by hospital staff. This kind of treatment often occurred after staff saw that their identity documents did not match their physical appearance.

Mexico’s Healthcare System

Mexico has a fragmented healthcare system, with various service providers available depending on a person’s employment status. For those who work in the federal public sector, the main provider is the Institute for Social Security and Services for State Workers (ISSSTE).[65] Tabasco has a system for its state workers called the Social Security Institute of the State of Tabasco (ISSET). The Mexican Institute of Social Security (IMSS) provides coverage for private sector employees and their dependents, and it is funded by employee and employer contributions and the federal government. For those who are not covered by these options, the main public assistance option is currently the Health Services of the Mexican Institute of Social Security for Wellbeing (IMSS-Bienestar), which replaced the coverage of Health Institute for Wellbeing (INSABI) in 2023, which in turn replaced Popular Insurance (Seguro Popular) in 2020). These are run by the Secretary of Health of Tabasco in collaboration with the federal government.

According to a 2020 government survey, the most used healthcare options in Tabasco at that time were Popular Insurance (1.08 million users), IMSS (381,000 users), and “other” (356,000 users).[66] More recent figures covering the period after the dissolution of the Popular Insurance point to an increase of lack of access to health services from 27 percent to 44.8 percent between 2020 and 2022.[67] Yet, entitlement to healthcare coverage does not mean that people in Tabasco necessarily receive high quality medical attention when they need it. Mexico, generally, suffers from structural problems in the medical sector, such as medical professional shortage and medication shortage, which often impacts socially and economically marginalized populations most acutely.[68] But transgender people face obstacles others do not.

Exposure of Gender Identity

Many of the trans people we interviewed said their gender identity was publicly exposed when nurses and other clinic staff called their names in the waiting room in front of other staff and patients. This violated their right to privacy, exposed them to further abuse, and discouraged them from seeking health care. For example, María J., a 31-year-old trans woman from Jalapa de Méndez, told researchers that not having her name and gender identity legally recognized has led to the humiliating and discriminatory exposure of her identity at clinics on various occasions, always in front of other patients:

They call out my [legal] name in the clinic. My doctor knows me, but if it’s a new doctor, they use my legal name. When they see me, they ask, “are you a family member?” I say, “No, it’s me.” They say, “show me your identification.” It’s uncomfortable, and it happens in front of everyone, and everyone stares at me.[69]

Lack of legal recognition, in combination with anti-trans bias, may have triggered onerous questions in clinics in some cases. Luna G., a 20-year-old trans woman, told researchers about such an experience at an IMSS Hospital in Villahermosa in March 2023:

In the waiting room, they shouted my deadname. There was a lady from the [clinic] administration. She asked for my hospital card, my [personal] identification and some other document. I gave them to her. She asked: “Why are you giving me the ID of [Luna’s legal name]?” I told him I was [legal name].… She handed the documents to the nurse. The doctor came out and asked me for my document. I gave it to her. “Are you [legal name]?” she asked me. I said yes. She was surprised and her face changed. She didn’t apologize. [She] was aloof during the consultation. Finally, she took my card and put four condoms down.[70]

Luna found the unsolicited provision of condoms discriminatory because she was not at the hospital for a sexual health-related issue. She explained that she felt the doctor was biased and could only see her as an HIV/AIDS patient.

Alexandra M., a 33-year-old trans woman from Villahermosa, said that she has had similar experiences on least five occasions between 2018 and 2022 at healthcare facilities in Tabasco. She explained to researchers how she felt in February 2022 when she went to a IMSS clinic for a painful injury on her heel and was referred to by her legal name:

When she called me, the nurse said, “guy,” in front of the others. It made me embarrassed, it made me feel ashamed. It intimidates me and makes me feel bad [when that occurs] because I have fought to be who I am. That hurts. The sadness is great. We [trans people] feel uncomfortable and insecure and it lowers our self-esteem.[71]

A few other interviewees expressed the anguish they have felt when their gender identity is exposed at health care clinics. Melissa A., a 48-year-old trans woman from Villahermosa said, “It pains me that they call me by [my legal] name, it’s disrespectful, everyone stares at you.”[72] Samanta L., a 31-year-old trans woman from Jalpa de Méndez, who has experienced this at least three times, said, “You have to be strong, but it changes how you define yourself, it brings you down completely.”[73] Analisa C., a 48-year-old trans woman from Villahermosa, said she was hospitalized around 2020 due to a pulmonary condition and hospital staff asked her for her “normal name,” which she found to be degrading.[74]

In small communities, such privacy rights violations can be especially difficult to recover from. Alicia S., a 60-year-old trans woman from Tenosique, said that in January 2023 she was also called by her legal name at the Tenosique General Hospital. She said that it made her uncomfortable, especially since no one in her life knows her by her legal name anymore, and that it exposed her gender identity to other patients. “It exposes you to possible transphobia,” she said.[75]

Other interviewees whose gender identity was exposed at clinics are Ángel P., a 20-year-old trans woman; Patricia E., a 52-year-old trans woman; and Guadalupe J., a 36-year-old trans woman, all three from Villahermosa.[76]

While legally recognizing a trans person’s chosen name and gender will not eliminate all discrimination, some experiences suggest that accurate identification documents may help alleviate some discriminatory treatment.[77] Isabel H., a 29-year-old trans woman from Nacajuca, one of the few trans people in the state of Tabasco to have achieved gender recognition through a court injunction, told researchers that her experiences at her clinic have changed since:

Before changing my [identification] papers, I would get asked, “Are you the patient’s relative?” This doesn’t occur anymore. I arrived at the clinic, and everything was normal, no more questions.[78]

Discriminatory Care

Interviewees also faced offensive and prejudiced treatment and comments from medical staff during their consultations, usually preceded by the disclosure of their gender identity through their legal name on their documents. María J., the trans woman from Jalapa de Méndez, recounted that in 2019 she went to a private medical clinic and the doctor touched her in a way she found discriminatory:

The doctor began to question me about my body. She touched my body, touched my breasts. She asked, “what do you put in [your body]? Take off your fake breasts.” She did not know about trans people. And when you’re sick and vulnerable, you just want to get out of there.[79]

María had not complained about her breasts or anywhere the doctor touched.

Similarly, Guadalupe J., a 36-year-old trans woman from Villahermosa, said that in February 2023, she was treated in a prejudiced manner when she went to see a clinic due to high blood pressure and cholesterol:

I did not feel well. The doctor opened my file. She called me by my real name [legal name]. They [administrative staff] wrote down “Guadalupe” in the file. But the doctor spoke to me with my [legal] name, as if to mess with me. The doctor began acting as if she didn’t want to touch me. “I’m not infected,” I told her. I felt like she didn’t want to treat me. For them [people with prejudices], we are not a person, they see us as weirdos. She treated me, but in a rude way.[80]

Dante T., a 26-year-old trans man from Villahermosa, told researchers that in 2021 a psychologist at the Regional Mental Health Hospital in Villahermosa made discriminatory comments about his gender identity and his health:

I was already living with my [masculine] identity. The psychologist talked to me as a girl. I told him, “You can call me ‘him,’ or by my last name,” but he did it to bother me. He told me, “Your psychiatric problems are due to your way of life,” that is, because I am trans. I put a complaint in writing, but I don’t know if they followed up on it.[81]

Paola L., a 56-year-old trans woman from Villahermosa, said, “One time a doctor said to me, ‘What are you doing dressed as woman? Can’t you see that you are a man?’”[82]

Even when patients have good relationships with their doctors, health care staff changes expose patients to providers who may be discriminatory. Karla H., a 49-year-old trans woman from Villahermosa, told researchers that in 2019 she went to Regional Hospital Dr. Juan Graham Casasús in Villahermosa to schedule a surgery her doctor said she needed. She explained what happened when her regular doctor was not there:

They changed the doctor because my doctor left, he was no longer going to continue working there. The new doctor seemed very rude. He referred to me as a man. I asked him to refer to me as a woman. He said, “For me, legally, [your legal name] is like this.” He also told me, “With me you have to start over with all the [medical] exams.” I said, “Isn’t there supposed to be a medical record?” He said, “I don't care.” I didn’t think about reporting it, because [the authorities] don’t do anything.[83]

Gynecological care for trans men can be especially challenging. Juan Carlos G., a 25-year-old trans man from Centla, told researchers that he experienced discrimination at a community hospital in Centla in February 2023 due to his legal name, as well as lack of awareness from medical staff about trans men:

It was a gynecologist. I had an appointment. I arrived and they started to call on people. They said my legal name in the waiting room. It was awkward. There were like three people [patients] and they all looked up to look at me… I then went into the examination room. The female nurse knew me, but not the male gynecologist. He said, “And what are you doing here? I am not going to see you.” I said, “OK, I will have to speak to the director.” He said, “talk to whomever you want.” I didn’t want to make a bigger scene. I wanted to file a complaint with the director, but my girlfriend didn’t want me to. In the end I went to a private doctor and didn’t have problems.[84]

Juan Carlos noted that now he prefers to spend money going to private clinic, where generally he has faced less discrimination. He said that for the appointment at the private clinic he paid approximately 2,500 Mexican pesos (US$145) and 4,800 pesos (US$280) for an additional exam. Such expenses may be significant for trans people who have difficulty securing employment.

Sandra R., a 42-year-old trans woman from Villahermosa, said the discrepancy between her legal and preferred names resulted in discriminatory treatment at her dentist’s office based on the stereotyped association that trans people are likely to be HIV positive. She described a dental cleaning at Rovirosa Hospital in Villahermosa in 2021:

They detected gingivitis and my gums bled a lot. The nurse cleaning me shouted, “Doctor, she’s bleeding a lot!” The doctor said, “What is your name?” I said, “My name is [my legal name].” But the doctor said confused, “What I am seeing here [in my file] does not reflect your appearance.” Then she said, “Have you taken the [HIV] test yet? I can’t do the [dental] service for you without the test.” She didn't let the girl continue with the cleaning. She wanted a recent test….I didn’t think to report it because the town here is closed-minded. It would’ve been a waste of time.[85]

III. Right to Education

Some of the transgender people that Human Rights Watch and Community Center for Inclusion interviewed had attended university in recent years or were currently enrolled. All of them faced discriminatory treatment either from professors or fellow students related to their legal name or gender. For one interviewee, this type of discrimination led to his leaving university altogether. Some interviewees said that if they had legal documents that reflected their chosen name and gender, some of the harassment and humiliation they experienced could have been avoided.

Many trans people interviewed mentioned that harassment and bullying was part of their primary and secondary school experience. Because none of the interviewees are currently children and most attended school over 10 years ago, their testimonies do not necessarily reflect current practices in Tabasco’s schools when it comes to gender identity. However, given that legal gender recognition is still not possible in Tabasco, it is likely that at least some children are experiencing discrimination due to their legal gender and name like the older interviewees in university.

Discrimination in Tertiary Education

In many cases, the discrimination that interviewees suffered in university had a negative impact on their academic performance. Dante T., a 26-year-old trans man from Villahermosa, told researchers that during his university studies he suffered verbal harassment from professors who refused to recognize his gender identity and social name. This occurred at the Juárez Autonomous University of Tabasco (UJAT) during two semesters starting in 2016, after which he discontinued his studies:

There were always small conflicts with the professors. It was every day, like in eight subjects with five teachers. A teacher was arrogant. She said, “You are going to enter my class as ‘her.’ I don’t want your [gender] confusions.” Another said, “you are going to respect [traditional or religious] values.” She said it speaking directly to me, at the entrance door, near the other students. “You’re going to attend under my rules,” she said.[86]

Dante told researchers that after entering university, he lost his motivation to study and was ultimately kicked out of the university. However, now that some years have passed, he has been considering going back to that university because it is the most affordable, despite his negative experience there.[87]

Like Dante, Samanta L., a 31-year-old trans woman from Jalpa de Méndez, said discrimination due to her legal name and gender impacted her performance in class. She was enrolled in the Los Ángeles University in Comalcalco between 2015 and 2018, where she studied psychology:

Some professors did ask, “What name would you like to be called?” But it was complicated with others. There was a psychologist [professor] who started repeating my legal first name during classes, in front of everyone. I used to participate a lot in the classes, but because of that I no longer participated when she wanted me to give my opinion. I think it wasn’t because she [the professor] didn’t understand [gender identity]; she did it because she was conservative.[88]

Samanta ultimately graduated from the university with a degree in psychology in 2018 but said that her academic credentials still have her masculine legal name, which makes her fearful of looking for a job. According to Samanta, what employers value the most is a candidate’s academic documents and hers do not reflect her feminine appearance, which creates complications for employers and exposes her to discrimination. “The university told me that I have to file a case to get my name legally changed in my diploma, but I don’t want any more legal proceedings,” she said.[89]

Juan Carlos G., a 25-year-old trans man from Centla, recounted a host of discriminatory and violent incidents related to his gender identity and legal name while he studied biology at the Juárez Autonomous University of Tabasco (UJAT). “Of the 50 professors I had [during my studies], about 20 of them did not respect my [chosen] name. They liked to humiliate me,” he said. One interaction with a professor in February 2018 was especially disturbing to Juan Carlos:

It was my genetics professor. One day he stopped saying my [chosen] name. I stood up [in class] and told him, “My name is [legal name], but I identify with and prefer ‘Juan Carlos.’” The professor said, “I am going to call you by the name on the [attendance] list. You are what you are. In this class I am not going to accept psychological deviations.” I said, “You can think what you want, but you are not going to change who I am.” The class was silent. It was our fourth semester, so everyone [of the students] knew and respected me, but some aligned with the professor.[90]

Juan Carlos noted that this type of interaction happened to him about 10 times, usually when it was his turn to speak in class. During his four years of study, he said he had to drop about ten courses due to this type of discrimination, even though he needed them to graduate. He said that he would fulfill those course requirements by either independently studying and passing an exam on the subject or, when that was too difficult, waiting for a new professor to teach the course.[91]

Juan Carlos said that the first three or four times such discrimination occurred, he was affected emotionally. “I didn’t want to go to class. In the hallways I heard whispers [about me], more people speaking poorly of me,” he said. During one of his semesters, Juan Carlos stopped attending class altogether because “four out of the five courses were unbearable” due to discrimination related to his gender identity.[92] Juan Carlos said that he submitted multiple written complaints, but the university authorities always said they would investigate, but there was never any follow up. “It never resulted in anything. I stopped reporting, because what’s the point,” he told researchers.[93]

Juan Carlos also said that his legal name exposed his gender identity to his classmates, which led to discriminatory comments like “how can you be a man without anything between your legs?” It may have also led to Juan Carlos suffering harassment in the bathrooms at the university:

In mid-2018, I was in a stall, and someone was taking a picture with their phone from above. That person took a photo. Around that same time, on another occasion in the men’s bathroom, two guys pushed me against the wall, and told me not to use the men’s bathroom. They said, “You’re just a dyke, you’re sick.” My friend came in and asked if I was OK. It was so scary, I thought something else was going to happen. Another time, I was kicked out of the women’s bathroom. I think that maybe they [these assailants] would not even have known that I am trans but for the professors exposing me with my legal name.[94]

Even for those interviewees who generally had good experiences at university, their legal name and gender posed problems. Luna G., a 20-year-old trans woman from Villahermosa and a nursing student at the Juárez Autonomous University of Tabasco (UJAT), told researchers that her experience at the university has been generally positive, but exposure of her legal name often leads to humiliating situations:

The professors have been inclusive, and I haven’t had many problems. Some ask me, “How do you identify?” But for the roll call, on the first day of school, they always say my deadname. I get angry. It’s happened a lot of times, five times last semester. In June 2022, something humiliating happened to me when I was going to take an exam. I entered the room, there were 30 people. The people in charge call your name in front of everyone. When they did, everyone stared at me. No one said anything, but it was strange.[95]

Luna G. also noted that in October 2022 she had an anatomy professor who refused to refer to her using feminine pronouns even though Luna asked her multiple times to respect her gender identity. “One day I was in the women’s bathroom, and she told me that I couldn’t use that bathroom, that she didn’t feel comfortable, and that she feared ‘an infection,’” Luna noted as illustrative of the professor’s anti-trans bias.[96] Luna did not file a complaint against the professor even though she wanted to. “I didn’t want problems, I was scared they would kick me out [of the university],” she said.”[97]

Isabel H., a 29-year-old trans woman from Nacajuca and a current architecture student at the Juárez Autonomous University of Tabasco (UJAT), told researchers that her current classmates know that she is trans, understand her identity, and generally respect her. However, Isabel completed another degree in business administration in 2016. She never picked up her diploma due to a mismatch between her identity documents and her physical appearance:

In order for the university to give me my diploma, the picture on the diploma has to match my legal name. I am still fighting to get my diploma.[98]

One’s legal name and gender may prove challenging even when doing online coursework. Mia C., a 41-year-old trans woman from Villahermosa, told researchers that in 2021 she enrolled in an online course in Monterrey in psychology, which she never finished. Due to her legal name, she experienced discrimination from the online instructor:

I entered the course as a woman, but my documents were masculine. The instructor told me that he knew I was wrong. He called me by legal name. He told me that I am not what I say I am [a woman].[99]

Discrimination in Pre-Tertiary Education

Virtually all interviewees described gender identity-related discrimination in their younger years in school. Ángel P., a 20-year-old trans woman from Villahermosa, summed up the general discrimination that she suffered throughout her entire primary and secondary school education due to her feminine expression:

In primary school, it was the bullying. They [the students] always mocked me, they hit me. When I went to secondary school, it calmed down a bit from the students, but it started with the teachers. They [the teachers] would not stop mocking me, they wouldn’t leave me alone. I reported it to [other] teachers, but no one did anything.[100]

Ángel said that the bullying could have been avoided if her legal documents “backed up” the feminine manner that she wanted to present physically:

It was a junior high school [secundaria] history class teacher in 2016. It was because I had long hair. I wasn’t a woman, he told me. He said it in a mocking tone. He encouraged my classmates to bully me, to make fun of me….I finally reported it, but the principal did nothing.

In 2020 during the pandemic, I went to high school [preparatoria]. The school principal was a religious person. He had a dress code. They [the teachers] didn’t let me go to classes because of my hair and makeup. They had a filter [a person] at the entrance to check clothing. If they detected something, they wouldn’t let you enter the school. They even expelled a friend [whose documents listed her gender as male] for wearing makeup.[101]

At the time researchers interviewed Ángel she was trying to finish her high school degree through an online course. She said it’s convenient for her to do so this way “in order to continue [her education] at home without discrimination.”[102]

Luna, the 20-year-old trans woman studying nursing at UJAT, also said that she faced discrimination based on her gender identity when she was in junior high school and in high school:

I had a history teacher in 2016 in junior high school [secundaria]. He began to talk about homosexuality [in class]. He said it indirectly, but I felt that he was addressing me. Only he brought up the topic. He would say, “If you are homo, all good,” but in a mocking way. In 2017, a boy in another classroom said, “He [sic] smells like AIDS.” I couldn’t do anything, I couldn’t even report because they would call my mother. My mom would tell my dad. And my dad would hit me.[103]

One interviewee had the acceptance of her parents and thinks she would not have experienced discrimination but for her discordant identity documents. María J., a 31-year-old trans woman from Jalapa de Méndez, began her transition when she was around 12 years old, and has had hormone replacement therapy and mental health support since around that time. Throughout, she has consistently had the support of her family to live as a girl and then woman. She told researchers that she did not experience discrimination due to her physical appearance, but was often outed in school due to her legal name:

Students never noticed that I was trans, until they heard my name, for example when school started and [teachers] called my [legal] name. Everyone would look twice. Maybe it was curiosity, maybe it was [sexual] interest, but it was invasive. People are badly informed [about trans identities].[104]

Many other interviewees said they experienced teasing and bullying in school and wished they had had the support to express their gender identity at a younger age. Some of these interviewees said that they would have welcomed being called a name that reflected their gender identity and think that it would have prevented at least some discrimination. These included Mati L., a 38-year-old trans woman from Cunduacán; Melissa A., a 48-year-old trans woman from Villahermosa; and Alexandra M., a 33-year-old trans woman from Villahermosa.[105]

IV. Discrimination in Financial Transactions

Many of the trans people interviewed by Human Rights Watch and Community Center for Inclusion said they faced obstacles in carrying out financial transactions, including accessing their own money, due to a mismatch between their physical appearance and the gender and name in their legal documents. Such challenges occurred in different financial institutions in the state, often frustrating their financial endeavors and humiliating them in the process. In some cases, interviewees’ gender identity was revealed to workers and other customers. Some interviewees have had to make arrangements like asking others to carry out transactions on their behalf, or paying for services that are safer and more comfortable for them but cost additional money.

Discrimination at Banks

Many trans people we interviewed suffered discrimination at banks. Michelle V., a 50-year-old trans woman from Centla, said that she has experienced problems at her bank due to her identity document:

The manager said, “But I don’t see the person in this identification document. But what is your name?” I said, “It’s Michelle.” He was confused. He may not have done it with [a discriminatory intent], but he was exposing me in front of people, asking me my legal first name. I didn’t start arguing, but people were staring since people here [in Centla] are very closed-minded.[106]

Samanta L., a 31-year-old trans woman from Jalpa de Méndez, explained that such discriminatory treatment during financial transactions due to her identity documents has happened at least nine times and makes her feel powerless:

The moment you present your [bank] card, they look at your name, and then ask for your identification document. You have to explain that you are a trans woman. It’s uncomfortable. It has happened also at malls and [retailers]. When they see your name, you have to immediately show your identity document. Then it becomes a thing, they have to call their supervisor to see if they will authorize [the transaction]. They have a lot of power [over you]. It all depends on whether they “accept” you or not, or if they “believe” you.[107]

This feeling of helplessness has led some interviewees to make alternative arrangements to carry out financial transactions. Juan Carlos G., a 25-year-old trans man from Centla, said that he has had issues with financial transactions approximately four times at two separate banks. In early March 2023, he went to make a deposit in his new account and said he was humiliated during his interaction with the teller:

They called [my legal name]. I said, “It’s my account.” They called the manager. The supervisor arrived and said, “This identity document is fake.” They said I could not make the deposit. I said, “It is not a fake identity document.” There was a whole scene. They were very rude, very defensive. They were yelling. In the end, I made the deposit at [a third-party financial institution] where they charge a commission [for deposits].[108]

Due to these kinds of experiences, Juan Carlos said that, if possible, he asks his girlfriend to conduct transactions on his behalf.

However, making arrangements does not always ensure fair treatment. Analisa C., a 48-year-old trans woman from Villahermosa, recounted that in February 2021 she went to make a money transfer at a third-party financial institution:

They [the workers] looked at my identity card. “Yes, it’s her,” they said. “But why do you have this name?” they asked. I explained that I wanted to get my legal name changed but was in the process. They just stared at me, and one of them shook his head. It made me feel bad, uncomfortable. It’s something personal, and I’m forced to discuss it with strangers.[109]

For Paola L., a 56-year-old trans woman from Villahermosa, it was less about the money and more about how it makes her feel. In December 2022 when a bank worker asked her whether she was a man or woman, she left upset. “One goes [to the bank] with fear, feeling discounted, discriminated against. How badly it makes you feel depends on what’s going on in your life that day.”[110]

It was similar for Alicia S., a 60-year-old trans woman from Tenosique, who said she has had to explain her identity document many times at the bank. “They ask, ‘Is it really you? You don’t look like [the person in the picture]. You’re a woman.’” [111]

Discrimination cannot fully be eliminated, but Isabel H.’s experience suggests it can prevent some disparate treatment. Isabel, a 29-year-old trans woman from Nacajuca, told researchers that, in March 2021, she went to her bank to withdraw a larger amount of money than usual and faced issues due to her identity documents not matching her physical appearance:

The woman [bank teller] treated me suspiciously. She didn’t believe that the name and picture was the same person before them. She said that they had to make sure it was me, so they did a security review. They had to confirm the titleholder and my fingerprints. All this lasted about 30 minutes. And it happened in front of all the other clients. I felt uncomfortable.[112]

Since then, however, Isabel filed a legal case to have her birth certificate modified to reflect her name and gender. Isabel said that now that she has had her documents changed, bank discrimination no longer occurs. “I feel more confident with my document, when I go out, when I initiate a transaction, when they call my name, I don’t feel anxiety,” she explained.

Discrimination in Other Financial Transactions

Alicia S., the trans woman from Tenosique quoted above, said that her identification document has caused difficulties for her in accessing benefits for seniors in Mexico, although she is entitled to them. She said that in March 2023 she tried to use her National Institute for Older People (Instituto Nacional de las Personas Adultas Mayores, known as INAPAM) identification document[113] for a travel discount and was rejected:

They said to me, “Your INAPAM identification? This doesn’t look like you. It is not an original identification. Are you the person in the document? You’re not 60 years old, and you look like a woman.”[114]

Melissa A., a 48-year-old trans woman from Villahermosa, also said that she has also been questioned about her identity and her identity document when she has tried to claim government financial support to which she is entitled.[115]

One interviewee had trouble with a unique kind of financial transaction due to her identification documents. Mia C., a 41-year-old trans woman from Villahermosa, said that in March 2023 she went to a pawnshop to earn some money by selling an item. Because she was unemployed, she needed the money. There, she faced hesitancy from part of the staff due to her identity document, which was required to complete the transaction, but which does not show her female gender:

I took the items and showed my identity document…. They [the pawnshop workers] didn’t want to assist me. At first it bothered me, but I explained it to take away their discomfort so they would assist me. I was frustrated.”[116]

Other interviewees who faced problems carrying out financial transactions due to a mismatch between their physical appearance and their legal document are Ángel P., a 20-year-old trans woman; Dante T., a 26-year-old trans man; Karla H., a 49-year-old trans woman; and Guadalupe J., a 36-year-old trans woman, all four from Villahermosa.

Alexandra M., who is one of the few trans people that was able to get her legal gender recognized through a court case, said that she has since noticed a difference regarding her ability to do business at her bank:

I have had opportunities to have a house, to have a loan in the bank without being discriminated against. I have options at the bank that I previously had less of. I have the right to be the woman I am.[117]

V. International Legal Obligations

Legal Gender Recognition

In November 2017, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights issued an advisory opinion stating that, in order to uphold the rights to privacy, nondiscrimination, and freedom of expression under the American Convention on Human Rights,[118] states must establish simple, efficient procedures that allow people to change their names and gender markers on official documents. The advisory opinion said this must be possible through a process of self-declaration, without invasive or pathologizing requirements such as medical evaluations.[119]

The court emphasized that such procedures should be “executed as quickly as possible” given they are of “such significance” and any delays can cause detrimental effects on an individual. It recommended an “administrative or notarial” procedure (instead of judicial proceedings, which often involve delays) and made clear that the State has a responsibility to ensure gender identities are updated in different records, to avoid an individual having to undertake “several procedures” involving “numerous authorities” and “unreasonable burdens.”[120]

In 2019, the Mexican Supreme Court issued a landmark decision with clear guidelines on legal gender recognition. The court said that this must be an administrative process that “meets the standards of privacy, simplicity, expeditiousness, and adequate protection of gender identity.”[121]

In March 2021, the Inter-American Court ordered the first application of the standard set in the advisory opinion in a contentious case, underscoring that legal gender recognition is an obligation under the American Convention on Human Rights.[122]

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) provides for equal civil and political rights for all (article 3), the right to recognition for everyone before the law (article 16), and the right to privacy and family (article 17). [123] Governments are obligated under the ICCPR to ensure equality before the law and the equal protection of the law of all persons without discrimination on any ground, including sex (article 26).

The Human Rights Committee, the treaty body responsible for overseeing implementation of the ICCPR, has specifically recommended that governments should guarantee the rights of transgender persons, including the right to legal recognition of their gender on the basis of self-identification, and that states should repeal abusive and disproportionate requirements for legal recognition of gender identity.[124]

In his report to the UN General Assembly in 2018, the UN independent expert on sexual orientation and gender identity noted that “lack of legal recognition negates the identity of the concerned persons to such an extent that it provokes what can be described as a fundamental rupture of State obligations … [W]hen States deny legal access to trans identities, what they are actually doing is messaging a sense of what is a proper citizen.”[125] He has said that legal gender recognition must be a simple administrative procedure based on self-determination and without abusive requirements such as medical certification.[126] Notably, the independent expert highlights trans people’s “systematic exclusion from education, employment, and housing, health care and all other sectors of social and community life” as reason for why gender recognition is a “human rights imperative.”[127]

The Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR), the treaty body responsible for overseeing the implementation of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR),[128] has also made an explicit link between the lack of gender recognition for trans people and violations of socio-economic rights. It has accordingly called on at least one state to ensure that trans people have “effective access to economic, social and cultural rights.”[129]

The Yogyakarta Principles, written by a group of international human rights experts who met in 2006 in Yogyakarta, Indonesia, and updated in 2017, also urge states to ensure that administrative procedures exist whereby a person’s self-defined gender identity can be indicated on all state-issued identity documents that include gender markers.[130] The principles also endorse an individual’s right to choose how and when to disclose their gender identity under the right to privacy.[131]

Right to Work

The ICESCR protects the right to work, “which includes the right of everyone to the opportunity to gain his living by work which he freely chooses or accepts” and requires states to “take appropriate steps to safeguard this right.”[132] Mexico and Tabasco’s constitutions likewise protect the right to work.[133]

The CESCR has concluded that equality in the workplace “applies to all workers without distinction based on … sexual orientation, gender identity,” among other grounds.[134] The committee also affirmed that “[a]ll workers should be free from physical and mental harassment, including sexual harassment” and that “[l]egislation, such as anti-discrimination laws, the penal code and labour legislation, should define harassment broadly, with explicit reference to sexual and other forms of harassment, such as on the basis of sex, disability, race, sexual orientation, gender identity and intersex status.”[135] The committee emphasized that States parties should “adopt measures, which should include legislation, to ensure that individuals and entities in the private sphere do not discriminate on prohibited grounds,” including in the workplace.[136]