Summary

The state of Mexico, the most populous of 32 states in the nation of Mexico, plays a central role in shaping the country's political landscape and legislative direction. Despite nationwide strides towards recognizing access to abortion as a constitutional and human right, current legislation in the state of Mexico continues to criminalize abortion, allowing exceptions only in cases of rape, “negligent abortions,” risk to the pregnant woman's life, or when the fetus has “serious congenital or genetic alterations.” With alarming rates of gender-based violence, including femicides and sexual violence, restricted abortion access further compounds the marginalization of women and girls within this large population. In contrast, neighboring Mexico City offers unrestricted abortion access up to twelve weeks of pregnancy, highlighting the stark differences in protections for reproductive rights across state borders within Mexico.

This report examines access to abortion in the state of Mexico between January 2018 and February 2024. Evidence detailed in the report indicates that abortion bans with exceptions do not guarantee access to this service even for cases legally eligible under the exceptions. Decriminalizing abortion in the state of Mexico is a key step toward eliminating these barriers. Simultaneously, health institutions, both at the state and federal level, should continue working together to ensure that women, girls and pregnant people have access to abortion services without discrimination.

Even within the aforementioned exceptions under the law of the state of Mexico, significant hurdles persist for women, girls and other pregnant people seeking legal abortion. Gender-based biases and societal stigma complicate their access to necessary care, as evidenced by reports of healthcare providers denying or delaying services, withholding necessary information, questioning survivors of sexual violence, and subjecting women to mistreatment. Moreover, some hospitals and providers impose arbitrary requirements that contradict or undermine the law or updated regulations and further restrict access. For example, state law does not require parental authorization for adolescents over age 12 to access abortion, but Human Rights Watch found that some providers unlawfully require parental involvement for adolescents under age 18. Similarly, some providers require survivors of sexual violence to report their cases to authorities before accessing abortion care, even though state law does not require such reporting. Fear of legal repercussions further deters both healthcare personnel from providing services and patients from seeking abortion care. Health institutions also grapple with capacity and infrastructure shortcomings, notably in personnel shortages.

Recommendations

To the state of Mexico Congress:

- Urgently pursue legislative changes to decriminalize abortion fully in the state of Mexico. This should include removing abortion from the criminal code to align with international human rights standards and Mexican Supreme Court rulings, ensuring no one is criminalized for seeking abortion services.

Harmonize the Civil Code of the state of Mexico to ensure that all individuals over the age of 18 have full legal capacity, including the right to make supported decisions in all areas of life, including the right to reproductive health.

- Harmonize state laws with international human rights obligations to which Mexico has committed, ensuring abortion laws conform to the best practices and rulings of international human rights courts and bodies.

To the General Congress of the United Mexican States:

Remove the prohibition of abortion from the federal criminal code, as mandated by the Supreme Court ruling Amparo 267/2023 of September 2023, which ordered Congress to eliminate this prohibition before the end of 2023.

To the state Secretariat of Health:

Expand the Safe Abortion Services (SAS) program to health institutions across the state of Mexico, including health centers, general hospitals, and specialty hospitals ensuring comprehensive abortion care is available at all levels of health care.

- Allocate additional resources for safe abortion services, including to ensure an adequate number of trained personnel, including psychologists and social workers, are available throughout the year in Welfare Modules.

- Enhance training on abortion legislation for all personnel in health institutions, including medical professionals, psychologists, social workers, and security personnel, with an emphasis on access to legal abortion.

- Implement a system to register not only hospital discharges for abortion care, but also requests to terminate pregnancies, covering legal grounds beyond rape in the state of Mexico.

- Strengthen coordination among health institutions and administrative entities across the state of Mexico, to ensure seamless access to abortion care for women, girls and pregnant people.

- Create a formal mechanism to enhance referral services to ensure efficient and timely access to appropriate abortion care facilities and resources.

- Develop clear protocols for requesting abortion care in each healthcare facility across all levels of care, tailored to accommodate the diverse realities state institutions.

- Launch awareness campaigns and utilize other outreach strategies to disseminate information about abortion access in the state of Mexico. Highlight existing grounds for legal abortion and the rights of women, girls and pregnant people.

- Ensure healthcare institutions adhere to Regulation 046 and technical guidelines for safe abortion care, eliminating unlawful requirements for parental authorization for adolescents over 12 and unnecessary, burdensome, and potentially traumatizing criminal reporting in cases of rape.

- Improve the collection and dissemination of comprehensive data on abortion services, focusing on capturing voluntarily-provided information about the legal exceptions, used method, procedural outcomes, and self-reported demographic information (gender, age, nationality, disabilities, languages spoken, place of residence, education, etc.) of service users to inform policy and healthcare improvements.

- Ensure sufficient healthcare personnel are available to provide abortion care during all shifts, including nights and weekends, to meet the needs of women, girls and pregnant people seeking these services.

- Require conscientious objectors to provide information about abortion care and referrals to other providers, if necessary, as part of their professional responsibilities, even if they do not provide direct abortion care.

To the federal Secretariat of Health:

- Develop and enforce clear guidelines for conscientious objection in healthcare settings in compliance with the Supreme Court ruling in Action of Unconstitutionality 148/2017, to ensure that it does not impede access to urgent or necessary abortion care.

- Establish a complaint and accountability mechanism to address obstacles related to abortion services, including delays, denials or unlawful demands, ensuring transparency and a timely resolution of issues.

Create an informative resource for individuals seeking abortions such as an accessible information sheet or pamphlet to be distributed across health institutions. Include clear protocols for accessing abortion services, rights of individuals and information on available support resources.

Implement guidelines across all healthcare authorities to eliminate language that stigmatizes, abuses, vilifies or discriminates against women, girls and pregnant people seeking abortions.

Conduct training programs to educate healthcare professionals and other staff in healthcare settings on respectful and non-discriminatory practices.

To federal health institutions, including the Mexican Social Security Institute (IMSS), the Mexican Institute of Social Security for Wellbeing (IMSS-Bienestar), and the Institute of Security and Social Services for State Workers (ISSSTE):

- Provide abortion services to women, girls and pregnant people who seek care in compliance with existing federal and state laws and judicial precedents, including Supreme Court rulings on Amparo 267/2023 and Action of Unconstitutionality 148/2017.

To the state Prosecutor’s Office:

Implement training programs for personnel in the Prosecutor’s Office to ensure they respect and uphold the rights of women, girls, pregnant people and healthcare professionals providing abortion care, preventing any intimidation or undue interference.

Methodology

The findings in this report are based on research conducted between March 2023 and February 2024. Human Rights Watch visited the cities of Toluca, Tlalnepantla de Baz and Cuautitlán in the state of Mexico, and Mexico City. We conducted in person and phone interviews with 66 people, including 23 representatives of civil society organizations and 43 representatives of government entities in the state of Mexico, including the Secretariat of Health, the Women’s Secretariat, the Human Rights Commission, General Hospital Cuautitlán “Gral. José Vicente Villada,” Cuautitlán Maternity, General Hospital Atlacomulco, Sultepec Hospital “José María Coss,” Las Americas Hospital, Texcoco Hospital, Maternal Hospital “Mónica Pretelini,” San Pedro Limón Hospital, Zacualpan Municipal Hospital, Maternal Hospital Los Reyes La Paz, Atizapan Hospital and La Perla Hospital, as well as representatives of the federal Secretariat of Health’s National Center for Gender Equity and Reproductive Health[1] in Mexico City.

Human Rights Watch reviewed official information responding to 32 transparency requests to federal and state government entities, including the federal Secretariat of Health, the state of Mexico Secretariat of Health, state of Mexico Health Institute (ISEM), Mexican Social Security Institute (IMSS), the Institute of Security and Social Services for State Workers (ISSSTE), the Judiciary of the state of Mexico, and the state of Mexico Secretariat of Security and Citizen Protection. In addition, we conducted a review of current legislation, public policies, and existing literature and press reports on issues related to the investigation.

Human Rights Watch abides by best practices to reduce the risk of re-traumatization of survivors or victims of human rights violations, especially in cases of sexual violence. It can be challenging for women, girls and other pregnant people who seek abortions in Mexico to speak openly about their experiences due to stigma and stereotypes they face. For these reasons, Human Rights Watch chose not to interview women, girls and other people with gestational capacity who have accessed or attempted to access abortions in the state of Mexico.

Based on detailed interviews with experts working with and accompanying women, girls and pregnant people that have sought abortion services, including healthcare personnel, prosecutors and lawyers, we documented cases of human rights violations. Wherever possible, we sought further details of new and old cases by requesting information from government institutions and other experts who interacted with the survivor. We also analyzed media and social media reports related to the case. This methodological approach also respects the recommendations of Mexican civil society organizations and experts to minimize the number of times survivors are asked to recount their stories, in order to avoid re-traumatization.

Several experts, civil society organizations and health personnel asked Human Rights Watch not to be named or to have their institutions identified publicly due to concerns about job security, fear of retaliation, or stigma associated with their work on access to abortion. In these instances, Human Rights Watch has refrained from disclosing their identities or the institutions where they work. We use pseudonyms when describing individuals’ experiences or cases with abortion care in the state of Mexico.

This report’s conclusions and recommendations are also based on an analysis of the state of Mexico’s human rights obligations to guarantee access to abortion, as well as to protect other human rights at risk when safe and legal abortion services are restricted or not fully available.[2] These obligations are reflected in federal and state legislation, as well as in the various international and inter-American human rights instruments to which Mexico is a state party.

I. Background

Regulation of Abortion in Mexico

Access to abortion constitutes part of the rights to nondiscrimination and equality; to life, health, and information; to freedom from torture and cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment; to privacy and bodily autonomy and integrity; to decide the number and spacing of children; to liberty; to enjoy the benefits of scientific progress; and to freedom of conscience and religion. These are all human rights that Mexico guarantees under its constitution and is obligated to protect under the international treaties it has signed and ratified.[3]

Mexico has 33 criminal codes, one federal and 32 state codes. Abortion is criminalized in all codes, although each state varies in its exceptions. The sole country-wide accepted exception in all criminal codes is abortion in cases of rape. Additionally, many state criminal codes include further exceptions, such as when the woman’s health or life is at risk. Sixteen states have decriminalized abortion – typically permitting it up to 12 weeks of pregnancy, except in Sinaloa where the limit extends to 13 weeks. Inconsistencies in these legal frameworks lead to disparities in access to abortion care across the country, depending on the state where the person seeking abortion care is located. This means that women and other people seeking abortions have varying levels of access to legal abortion services based solely on their place of residence, leading to unequal protection and unequal rights across state borders within Mexico.[4]

Mexico has recognized that the criminalization of abortion is unconstitutional in several Supreme Court rulings over the past few years. Mexican authorities are obligated under the pro persona principle[5] to act to protect human rights to the widest extent possible, meaning they must grant individuals the broadest protection based on the most favorable normative interpretation of the law. Although one of the principles of criminal law is ultima ratio,[6] the concept that criminal liability should be as the last resource in solving a public problem, abortion has been traditionally regulated through criminal law and remains part of criminal codes at the state level with varied penalties.

However, access to abortion is fundamentally a human rights issue that should be regulated as a rights and public health matter, and not as a criminal matter. In recent years, 15 of Mexico’s 32 states have decriminalized abortion. In most of these states, the local congress voted to decriminalize abortion by changing local legislation. In four states, the change came through a Supreme Court ruling.[7] The following section outlines some of the major laws, rulings and policies regulating abortion in Mexico.

Regulation at the Federal Level

There are at least three regulations that apply at the federal level when it comes to abortion. One is a law, another is an official regulation (Norma Oficial Mexicana or NOM, in Spanish,)[8] and another is a guide. There are also judicial precedents that play an important role in regulating abortion in Mexico.

General Victims’ Law

In 2013, Congress passed the General Victims’ Law.[9] This law establishes, at the national level, the rights of persons who have been victims of crimes (as defined in Mexico’s criminal codes) or human rights violations. This law specifies that all survivors of sexual violence have the right to access an abortion,[10] and that authorities must presume survivors’ good faith.[11]

Regulation 046 (NOM 046)

In 2007, Mexico agreed to settle a case brought against it at the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights by Paulina del Carmen Ramírez Jacinto, a 14-year-old rape survivor who was denied her right to legal abortion by authorities in the state of Baja California.[12] In 2009, pursuant to the settlement, the federal Secretariat of Health published a new official regulation (formally known as a Norma Oficial Mexicana or NOM), NOM 046-SSA2-2005 (henceforth referred to as Regulation 046) regulating providers’ response to family, sexual and gender-based violence against women.[13]

This regulation required public and private health care providers to provide abortion services in cases when the pregnancy was the result of a rape, which has been decriminalized in all criminal codes of Mexico. However, the regulation required the prior authorization of an authority with jurisdiction – usually a judge or a prosecutor -- and, in the case of children and adolescents, the consent of a parent or guardian.[14] In 2016, as a result of many years of civil society advocacy, the federal Secretariat of Health amended Regulation 046 to eliminate those requirements for adolescents over 12. [15] Under the current version of Regulation 046, the person seeking abortion must submit a written statement to a health institution stating, under oath, that the pregnancy is a result of rape, and that the person wants an abortion.[16]

Technical Guidelines for Safe Abortion Care

In 2022, the federal Secretariat of Health updated its 2021 technical guidelines for safe abortion care at the federal level. This document establishes basic criteria for the healthcare sector so that women and persons with gestational capacity, including adolescent girls, who require safe abortion services in Mexico, have access to timely, effective, and comprehensive care with a gender and human rights perspective.[17]

These include ethical and professional obligations of health personnel such as: maintaining privacy and confidentiality; providing pertinent information before, during and after the procedure; respecting the person’s decision to terminate or not terminate their pregnancy; obtaining informed consent; and other medical provisions such as the alternatives for treatment available. The guidelines also reiterate the limits on conscientious objection that the Supreme Court established in Action of Unconstitutionality 54/2018, explained below.[18]

Supreme Court Jurisprudence

Most Supreme Court jurisprudence related to abortion has been established through actions of unconstitutionality, which are legal challenges that begin because an authority considers that a law is contrary to the constitution. The Supreme Court of Mexico has repeatedly ruled that criminalization of abortion is contrary to the human rights protected in the Mexican constitution.

In 2007, Mexico City’s Legislative Assembly amended the city’s criminal code to legalize abortion during the first twelve weeks of gestation.[19] The National Human Rights Commission and the Attorney General presented an action of unconstitutionality, arguing that legalizing abortion violated the constitution. The Supreme Court ruled in favor of Mexico City, upholding its amended criminal code.[20] This set an important precedent and sent a message to all state legislatures that they too could change their criminal codes to reflect Mexico City’s code.[21]

In September 2021, the Supreme Court, when analyzing provisions of the Criminal Code of the state of Coahuila, declared that the absolute criminalization of abortion is unconstitutional, recognized the right to reproductive autonomy, and endorsed access to safe abortion as a matter of human rights. Through Action of Unconstitutionality 148/2017 in 2021, the Court invalidated Articles 196 and 199 of Coahuila’s state criminal code. The first of these articles punished anyone who had an abortion and anyone who performed or assisted in abortions; the second established a time limit of twelve weeks of gestation for abortions in cases of rape.[22]

The Court determined that there is a constitutional right to decide and established that “strict prohibition (backed by criminal sanction) is tantamount to establishing an obligation for the woman who, once pregnant, must necessarily endure it and become a mother.”[23]

The right to decide, as defined by the Court, consists of seven pillars: 1. Comprehensive sex education. 2. Access to information on family planning and contraception. 3. The right to decide whether to continue or terminate a pregnancy. 4. That a woman or pregnant person receives sufficient information to make an informed decision about continuing or terminating their pregnancy. 5. The protection of the decision to continue or terminate a pregnancy. That is, both those who wish to continue a pregnancy and those who choose to terminate it are entitled to all health services. 6. The right to terminate a pregnancy in public health institutions in an accessible, free, confidential, safe, unobstructed, and non-discriminatory manner. 7. The right to terminate a pregnancy of the pregnant woman’s free will. However, this right may only be exercised during a brief period, close to the beginning of the gestation process.[24] |

This ruling not only decriminalized abortion in Coahuila, but also set a precedent preventing any judge from convicting anyone for the crime of abortion when the abortion was performed with the consent of a pregnant woman or person in an early stage of the pregnancy.[25]

In a separate ruling in 2021, the Supreme Court found that healthcare workers' conscientious objection to performing abortions is not an absolute or unlimited right that can be invoked in any case and under any form, after the National Human Rights Commission challenged, through the Action of Unconstitutionality 54/2018, the General Health Law’s provisions on conscientious objection.[26] The ruling established a list of the limits that conscientious objection must observe, which includes the obligation for institutions to have enough personnel to guarantee the right to health and that conscientious objection is not valid in cases where the patient’s life or health is at risk or when there is no alternative care facility to refer the patient to.[27]

Most recently, in September 2023, the Supreme Court ruled that provisions that criminalize the right to decide on the termination of a pregnancy are contrary to the rights to human dignity, reproductive autonomy, free development of the personality, health, and equality and non-discrimination.[28] This ruling was the result of an amparo (a type of legal challenge through which a person can request protection against government actions or omissions that violate human rights) filed by Grupo de Información en Reproducción Elegida (GIRE), a Mexican reproductive rights organization. The ruling ordered Mexico’s Congress to remove the prohibition of abortion from the federal criminal code before the end of 2023.[29] As of August 2024, Congress had not yet modified the criminal code. It also means all federal health institutions, including the Mexican Institute of Social Security (IMSS), the Institute of Security and Social Services for State Workers (ISSSTE), and any other federal health facility, no longer have any legal barriers to provide abortion services to pregnant women and people who request it. Despite this mandate, the Mexican Social Security Institute (IMSS), which runs the majority of public hospitals in Mexico, informed GIRE in May that it is not currently providing abortion services due to the lack of legislative changes following the ruling.[30]

The Supreme Court has also ruled on individual cases of human rights violations related to abortion access, including the cases of Marimar, Fernanda and Jessica.[31] Marimar and Fernanda were survivors of sexual violence who were denied abortions in public hospitals in the states of Morelos and Oaxaca. GIRE, which represented both women, filed two amparos arguing that “the state health authorities had violated their human rights by denying them abortions—specifically their right not to be subjected to cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment— and, therefore, they had to be recognized as victims and guaranteed comprehensive reparation.”[32] Jessica, also a survivor of sexual violence, was denied an abortion because Article 181 of the state of Chiapas criminal code only allowed abortion in cases of rape within the first 90 days of pregnancy, and her pregnancy was more advanced. With GIRE’s support, Jessica and her mother also filed an amparo stating that Article 181 of the Chiapas criminal code was contrary to the Constitution because it limited the practice of rape-related abortion to the first 90 days of pregnancy.[33]

In Marimar and Fernanda’s cases, the Supreme Court ruled that having access to abortion is a right and an emergency care service for survivors of sexual violence and denying it is contrary to human rights, specifically, to the right to not be subjected to cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment.[34] The Court also ruled that, even if survivors can access an abortion by other means, denying an abortion in a public health facility still constitutes a human rights violation. With this precedent, in Jessica’s case, the Supreme Court ruled that the 90-day limit in cases of rape was unconstitutional.[35]

Abortion in the State of Mexico

The state of Mexico, with a population of 16,992,418, is the most populous Mexican state. It is situated adjacent to Mexico City, the capital, and has ample political influence, as it holds the largest electoral registry in the country.[36] On June 4, 2023, the Morena party won the gubernatorial elections, ending 94 years of governance by the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI).[37]

The State of Mexico faces serious challenges with gender-based violence. According to INEGI data, 60.7 percent of women in the state of Mexico will suffer sexual violence throughout their lives, which is higher than the national average of 49.7 percent.[38]

Regulation at the State Level

Even though abortion can no longer be prosecuted as a federal crime after the September 2023 Supreme Court ruling,[39] abortion remains a crime under the state of Mexico’s Criminal Code, both for the pregnant person and for anyone who assists in providing the abortion, except in cases of rape, in cases of “negligent abortions,” when the life of the pregnant woman is in danger, or when the fetus (which Mexican law describes as the "product of conception") has “serious congenital or genetic alterations.”[40]

Criminal code of the state of Mexico: Exceptions for legal abortions. Under Article 251 of the State of Mexico’s Criminal Code, abortion is not considered a crime in the following circumstances: I. When it results from “imprudent or negligent behavior” by the pregnant woman; II. When the pregnancy is the result of rape; III. When the pregnant woman would be at risk of death without an abortion, in the opinion of the attending physician, who shall hear the opinion of another physician, if possible, without causing a dangerous delay; and IV. When, in the opinion of two physicians, there are “genetic or congenital alterations” that may result in “the birth of a being with serious physical or mental disorders,” as long as the pregnant woman gives consent.[41] |

A person who performs an abortion is subject to three to eight years of prison if it is performed without the consent of the pregnant woman, and from one to five years of prison if it is performed with the consent of the woman.[42] Women who consent to an abortion are also subject to one to three years of prison.[43] Medical personnel are also subject to be suspended from three to six years in the exercise of their profession.[44]

In 2023, the state of Mexico's Legislature approved Decree Number 487, enacting the Victims’ Law, which aims to recognize and protect victims' rights, establish authorities' obligations, and provide comprehensive assistance and reparations, with sanctions for non-compliance. Article 23 specifies that all victims of sexual assault shall be guaranteed access to emergency contraception services; however, unlike the General Victims' Law, the state of Mexico’s Victims Law does not mention access to abortion for victims of sexual assault.[45] It is important to note, however, that the General Victims’ Law applies nationwide and applies to both federal and state authorities, including in the state of Mexico.

Public Sector Service Provision

Mexico has a fragmented healthcare system, with various service providers available depending on a person’s employment status. For those who work in the federal public sector, the main provider is the Institute for Social Security and Services for State Workers (ISSSTE).[46] The state of Mexico has a system for its state workers called the Social Security Institute of the state of Mexico and Municipalities (ISSEMYM).[47] The Mexican Institute of Social Security (IMSS) provides coverage for private sector employees and their dependents, and it is funded by employee and employer contributions and the federal government. For those who are not covered by these options, the main public assistance option is currently the Health Services of the Mexican Institute of Social Security for Wellbeing (IMSS-Bienestar), which replaced the coverage of Health Institute for Wellbeing (INSABI) in 2023, which in turn replaced Popular Insurance (Seguro Popular) in 2020). These are run by the Secretariat of Health of the state of Mexico in collaboration with the federal government. Private clinics and hospitals in the state of Mexico also provide abortion services.

Health institutions managed by the state Secretariat of Health provide abortions only in the cases permitted by the state Criminal Code.[48] In other words, these institutions can only provide abortions in cases of rape, when the life of the pregnant woman is in danger, or when the fetus has “serious congenital or genetic alterations.”[49] Human Rights Watch reviewed public information requests to IMSS, IMSS Bienestar and ISSSTE. As of June 2024, IMSS stated that it did not provide abortion services.[50] On November 2023, IMSS Bienestar reported that it had not yet assumed administration of the state-run public hospitals intended for integration into its system and consequently did not possess information on the provision of abortion services.[51] ISSSTE reported they had not provided abortion services in the state of Mexico in the past five years.[52]

It is impossible to know how many abortions have been performed in health institutions managed by the state Secretariat of Health, and under what grounds provided in the criminal code, as the state Secretariat of Health does not disaggregate this information.[53] However, the state Secretariat of Health provided Human Rights Watch with data on their hospitals’ discharges for abortion care, which can include legal and voluntary abortions[54] under permitted grounds, as well as obstetric emergencies, and data on the number of abortions on the grounds of rape. Between 2018 and 2022, the state Secretariat of Health registered 41,261 hospital discharges for abortion care and 179 abortions performed on the grounds of rape.[55]

The low number of abortions on the grounds of rape in the state of Mexico indicates limited utilization of this service within the public sector. This trend may be ascribed to the challenges documented by Human Rights Watch in this report and associated with accessing the abortion care despite its legal status in the state.[56]

The information provided by the Secretariat of Health indicates that women between the ages of 20 and 24 are the most frequent users of abortion services in public hospitals run by the state Secretariat of Health.[57] In 2022, for example, the state Secretariat of Health registered 2,406 hospital discharges for abortion care in people aged 20-24, followed by 1,814 discharges in ages 25-29 and 1,586 in ages 15-19.

Of 41,261 hospital discharges for abortion care between 2018 and 2022, only 99 were self-reported as Indigenous people and 18 were self-reported as Afro descendants. According to the 2020 Population and Housing Census by INEGI, in the state of Mexico, 417,603 people speak an indigenous language, representing 2.6 percent of the total population aged five and older.[58] The Afro-Mexican population in the state totals 296,264 people.[59]

All people who accessed abortion care between the years 2018 and 2022 identified as girls or women.

The Secretariat of Health reported it does not track information on whether people who receive abortions have disabilities or are migrants.

Many people seeking abortion care in the state of Mexico travel to Mexico City, where abortion was decriminalized in 2007. Women from the state of Mexico are the second most frequent group seeking abortion services in Mexico City, following those from within the city itself. Since 2007, 72,336 women and pregnant people living in the state of Mexico have accessed abortion services in Mexico City.[60]

Forcing people who live in the state of Mexico to travel into Mexico City to obtain abortion services can disproportionately burden people living in conditions of poverty, those with disabilities or care responsibilities, adolescents, and others who may not be able to easily travel into the city. While the state of Mexico geographically surrounds Mexico City, just around 8 percent of state of Mexico residents say they travel regularly into Mexico City for work.[61] The state of Mexico is large, both in population and geography. Around 25 percent of the state’s population, nearly 4.5 million people, live outside of the Mexico City metropolitan area, some up to five hours’ drive from the city and longer without private transportation.[62] The state of Mexico has an average household income of around 19,000 pesos per month, below the national average of 21,231 pesos per month, and significantly lower than that of Mexico City, at nearly 30,000 pesos per month.[63]

This disparity can also place a significant burden on Mexico City health services, as Mexico City’s population is just 9,209,944, compared to 16,992,418 people in the state of Mexico.[64]

II. Barriers to Accessing Legal Abortion in the State of Mexico

Everyone has the right to reproductive autonomy. In other words, they have the right to make decisions about their own body and their future with regard to a pregnancy.[65]

States have an obligation to ensure access to abortion, which includes removing any barriers that impede access. Those seeking abortion care should not be met with discriminatory attitudes or biases based on gender that undermine abortion access, authorities should not impose requirements outside the law that make accessing an abortion more difficult, and authorities should make sure the capacity and infrastructure of the health personnel is adequate to meet the demand.[66] Adolescents seeking abortion care face additional barriers, such as unlawful requirements of parental authorization, even in cases where they are survivors of sexual assault.[67]

Gender Stereotypes Resulting in Denial and Delays of Services and Mistreatment

Healthcare personnel across the state of Mexico told Human Rights Watch that a strong stigma surrounding abortion exists amongst many of these professionals, based on the idea that women, once pregnant, have the obligation to become mothers.[68] Human Rights Watch identified several instances of stereotypes about women seeking abortions in interviews with health personnel. This stigma often results in conduct by health personnel that undermines abortion access.

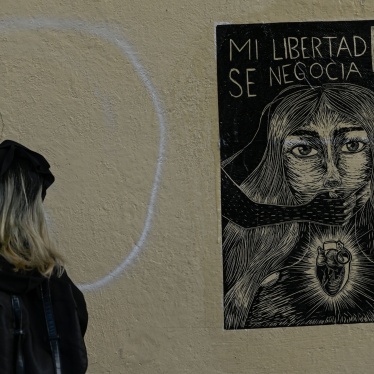

The state of Mexico’s criminal code, which targets women in particular, reinforces the gender stereotype that their role is motherhood. It also serves to discipline women's sexuality and punish those who do not comply with their stereotypically assigned role in society.

The 2021 Supreme Court ruling overturning the abortion prohibition in the state of Coahuila highlighted the right of women and other people who can get pregnant to legal equality. In order for Mexican authorities to fully respect the right to equality, the court held, they should eliminate institutionalized stereotypes about women and people who can get pregnant, such as legal prohibitions on access to abortion.[69]

International human rights law also emphasizes the need to remove barriers to accessing abortion services to ensure equality and non-discrimination.[70] The CEDAW Committee has highlighted that failing to provide necessary services and criminalizing certain services that specifically affect women constitutes a violation of reproductive rights and discrimination.[71] The Committee’s recommendations also emphasize that laws criminalizing medical services needed only by women and punishing those who seek these services create significant discriminatory barriers to appropriate health care.[72] To comply with these international standards, states need to dismantle discriminatory practices and legal restrictions that prevent equitable access to reproductive health services.

However, gender stereotypes remain present in abortion care in the State of Mexico and result in important barriers in accessing legal abortion even in those cases under the grounds specified in the criminal code.[73] These barriers, which international human rights law requires be removed, include health personnel denying or delaying the service, questioning veracity of testimonies from survivors of sexual violence by health personnel, and mistreating women seeking the service.

An official from the state Secretariat of Health told Human Rights Watch that, even though one of the main components of safe abortion care is quality care and there are systems in place to monitor it, they have had situations of mistreatment of women and pregnant people before and after abortion care.[74]

Doctors, nurses and psychologists from several hospitals interviewed by Human Rights Watch also said they had observed mistreatment of patients by their personnel driven by stigma surrounding abortion. A doctor from one hospital explained that this is a significant barrier and that some patients do not access abortion services because they never come back after experiences of mistreatment.[75] Additionally, doctors from several hospitals mentioned that some medical personnel refuse to provide abortions because they believe women may change their minds about it after.[76] This reinforces the patronizing attitudes and stereotypes.

This was also the case for Julia, a 23-year-old woman who was hospitalized during an abortion in progress in the state of Mexico in 2022. When healthcare personnel found out that she had a daughter, they questioned her parenting saying that a “good mother doesn’t do these things,” meaning mothers should not terminate their pregnancies.[77]

A civil society organization that provides accompaniment to pregnant woman and girls who seek abortions told Human Rights Watch that cases where health personnel question testimonies of survivors of sexual violence are not unusual: “we have accompanied cases where the hospital’s social worker questions whether the testimony of a survivor of sexual violence is truthful or not.”[78] This, even though the General Victims’ Law establishes that authorities must presume victims’ good faith, and NOM 046 says that healthcare workers should apply the good faith principle when treating victims of sexual violence.[79]

A civil society organization told Human Rights Watch they have accompanied women in cases where doctors have delayed performing abortions against a person’s will or have pressured them to wait before having an abortion, even in cases where their life was at risk.[80] This was also the case for Dayana, a 15-year-old girl and survivor of sexual violence whose life was at risk. Dayana tried to access an abortion in the state of Mexico and was told by health personnel that “she needed to act like a lady, because that’s what she was,” according to representatives of GIRE who accompanied her. Two doctors she saw, in the public and private sector, did not give her the option to access an abortion. This delayed the procedure by several weeks.[81]

A representative from a civil society organization told Human Rights Watch that it is common for other people in health institutions to act in ways that impede abortion access based on gender stereotypes. They have accompanied cases where security guards outside a hospital have questioned women’s motives for seeking abortions and have refused to let them in.[82] This poses a barrier to effectively requesting an abortion from a health institution.

Hospital personnel interviewed by Human Rights Watch also explained that women may be deterred from requesting abortion services because of lack of sensitivity from health personnel. The first interaction women seeking abortions have with health institutions is crucial and if health personnel give them incorrect information or make them feel questioned, women may not come back.[83]

The stereotypes women and people seeking abortions face in the state of Mexico are an important barrier in accessing abortion care. Civil society organizations often intervene in and accompany these cases through legal recourses like amparos, informally advocating with health personnel in hospitals directly or physically accompanying women and pregnant people to make sure they can access abortion care. According to several representatives of civil society organizations, women and pregnant people have an easier time accessing abortions when they are accompanied by civil society organizations than when they go on their own.[84]

However, these stereotypes deter women and adolescents from seeking abortion care in the first place. A member of a civil society organization told Human Rights Watch that adolescents, in particular, often fear being punished for their sexuality. For example, Jimena, a 16-year-old girl, said she did not want to seek legal abortion in a public hospital for fear of being questioned, denied services, or mistreated.[85]

Unlawful Requirements for Accessing Abortions

Health workers in the state of Mexico have repeatedly attempted to impose requirements on people seeking abortions beyond those established under Mexican law. Neither state nor federal law require parental authorization for adolescents over 12 years old to obtain an abortion. It does not impose a limit on the number of weeks of gestation for access to abortion in the cases stipulated as exceptions in its criminal code. Nor does it require survivors of sexual violence to have filed a criminal complaint to access abortion care. However, Human Rights Watch identified some instances in which healthcare workers at public hospitals in the state of Mexico imposed unlawful requirements on women and girls seeking abortions.

Requirement of Parental Authorization

Forced parental involvement in abortion is a harmful barrier to access for those under age 18 and violates a range of human rights.[86]

Even though most health personnel Human Rights Watch interviewed were aware of Regulation 046 and its provision that adolescents over age 12 do not require parental authorization to access abortion care, this was not the case at every hospital Human Rights Watch visited. In one hospital, some doctors interviewed by Human Rights Watch could not provide an accurate answer when asked about the age at which adolescents are no longer required to have parental authorization, as stipulated by the legislation, and said they are requiring parental authorization for those 14 years old and under.[87]

Staff from two civil society organizations told Human Rights Watch that, when accompanying girls under 18 to access abortions, they had observed it was common for health personnel to ask them to come with a family member.[88] In this sense, the state Prosecutor’s Office recognizes that the implementation of Regulation 046’s provisions regarding parental authorization has been challenging. According to a state prosecutor interviewed by Human Rights Watch, hospital staff routinely inform the Prosecutor’s Office about cases of abortion for girls based on rape, providing detailed circumstances, even though the current law does not require this. Despite repeated notices from the Prosecutor's Office to healthcare personnel that such reporting is unnecessary, they often still choose to do this.[89]

Limitation of Weeks of Gestation

In 2022, GIRE provided comprehensive support, including legal and psychological support, to a 15-year-old survivor of sexual violence who was denied an abortion past 12 weeks of gestation in several public hospitals in the state of Mexico. The girl and her mother told GIRE that medical personnel at the hospitals refused to provide an abortion telling them it was not an option for her, and that it was too dangerous to have an abortion after 12 weeks of gestation. Instead, doctors gave them prenatal care instructions.[90]

Some doctors interviewed by Human Rights Watch said they would be reluctant to provide abortion services past 12 weeks of gestation, even though there is no legal limitation in cases of survivors of sexual violence: “victims of sexual violence said they went out with their friends, got drunk and then didn't know what happened and they come to me wanting to terminate the pregnancy. And the law says I have to do it and I don’t want to do it because she is carrying a baby. […] If [women and girls] had the misfortune of going through a situation of abuse, [they should] report it quickly.”[91] Health personnel told Human Rights Watch that many survivors of sexual violence they have assisted often request abortions past 12 weeks of gestation because they did not realize they were pregnant or because other health institutions, public or private, have denied them the service.[92]

Requirement of Reporting or Court Permission

A member of a civil society organization from the state of Mexico told Human Rights Watch that, when people seek abortion care in hospitals, some health personnel, including social workers, ask for proof they filed a criminal report,[93] even though this is no longer a legal requirement according to Regulation 046. They told us that many women agree to return after reporting sexual violence to the Public Prosecutor's Office. This needlessly exposes people seeking abortion care to re-traumatization, which is why it is common for women and girls to give up because of the lengthy and tiring process.[94] It is important to note that there is no obligation to report sexual violence; on the contrary, it is a right that survivors may or may not choose to exercise.

Some health personnel in hospitals told Human Rights Watch that in their view, the safe abortion protocol operates “more efficiently” when survivors of sexual violence request abortions after having filed a report at the Prosecutor’s office or if they have a judge’s order.[95] However, an official complaint of sexual violence only serves to make health personnel feel more secure as they operate in a climate of fear, instead of benefiting survivors seeking abortion care. Hospital representatives told Human Rights Watch that medical personnel still need more training to know what to do in instances where women want to access an abortion but do not have court permission.[96]

The state Prosecutor’s Office told Human Rights Watch that there have been instances where hospitals report cases of sexual violence even though it is not required by law because they fear legal consequences.[97] Moreover, an official from the National Center for Gender Equity and Reproductive Health (CNEGSR) told Human Rights Watch that prosecutors do not always have a thorough understanding of abortion legislation: “I have had various instances of prosecutors threatening legal action against healthcare personnel providing abortion care”.[98]

Access to Abortion for Women, Girls and Pregnant People with Disabilities

Women, girls and other pregnant people with disabilities in the state of Mexico encounter additional barriers when seeking abortion care due to the existence of legal guardianship (interdicción, in Spanish). This legal system means “(…) that a third party could decide everything for them, even around health treatment.”[99]

In 2021, the First Chamber of the Supreme Court declared guardianship unconstitutional and ruled that it discriminates against people with disabilities. Subsequently, in April 2023, Congress abolished guardianship at the national level through landmark reform of Mexico’s national civil procedure code granting all adults full legal capacity and the right to supported decision making if they so choose.[100] The safe abortion technical guidelines also recognize equality and equity, aiming to implement strategies that provide differentiated attention to persons with disabilities and create the material conditions necessary to provide the services protected by law.[101]

In 2024, the state of Mexico passed the “Law for the Inclusion of People with Disabilities in the state of Mexico,”[102] which aligns with the Supreme Court's 2023 decision.[103] However, the state legislature has yet to amend its Civil Code, maintaining the guardianship system for people with disabilities.[104] This legislative inconsistency jeopardizes the ability of women disabilities to make decisions. Such practices are a violation of international human rights law, which requires countries to treat everyone equally before the law, including those with disabilities.[105] As a result, women with disabilities may be deprived of their reproductive health decision-making autonomy, including access to abortion services.

Fear of Criminalization

Even though there are exceptions to the criminalization of abortion under certain circumstances, the fact that abortion is regulated in the state of Mexico’s criminal code still sends a message that it is an illicit behavior that can be prosecuted. This presents an important barrier to health personnel's provision of abortion services and to the ability of pregnant women, girls and other pregnant people to access it.

In the case of health personnel, an official from the state Secretariat of Health told Human Rights Watch that the stigma associated with the treatment of abortion as a crime, even in those cases when it is not considered a crime by law, is one of the greatest challenges to safe abortion care.[106] A private abortion provider explained that medical personnel fear imprisonment and loss of prestige if they engage in abortion care. He believes that decriminalizing abortion, on all grounds, would help destigmatize abortion and improve access.[107]

Eleven healthcare personnel interviewed by Human Rights Watch in hospitals across the state expressed similar sentiments.[108] They said that fear of criminalization or legal repercussions for performing abortions, even in cases when it is legal, result in healthcare professionals being hesitant to admit women for abortion services: “The position of gynecologists is more of an 'I protect myself and I protect my medical practice' position.”[109] In some cases, doctors told us they believe that patients might change their minds about wanting to have an abortion after the fact and that this could lead to “legal consequences.”[110]

The lack of clarity and knowledge about the law generates an important practical barrier to pregnant women and other pregnant people accessing the abortion care efficiently. The state Secretariat of Health and the state Prosecutor’s Office have joined forces in training health personnel on this topic.[111]

At the same time, the state of Mexico continues to criminalize women and other people who can get pregnant by opening criminal investigations against them for the crime of abortion. According to the Executive Secretariat of the National Public Security System (SESNSP), which collects and publishes data on criminal investigations from all states, between January 2018 and March 2023, the state of Mexico’s prosecutor’s office opened 740 criminal investigations for the crime of abortion.[112] This, even though the judges are prohibited from issuing sentences for this crime when performed with the will of a pregnant woman or other pregnant person in an early stage of the pregnancy, as a result of the 2021 Supreme Court ruling.[113]

This was the case for Julia, a 23-year-old woman from Ecatepec who arrived in a health center with an abortion in progress. According to GIRE, health personnel pressured her to say that she used medication to induce the abortion and, once she said so, she was prevented from leaving the hospital. They also told her, even though it was not true, that she and her entire family would end up in jail. Medical staff reported her to the state Prosecutor’s Office, which sent personnel to question her at the hospital, where she was held with no explanation for a week.[114]

There are other crimes, such as infanticide and homicide by reason of kinship,[115] for which women and pregnant people accessing abortion care have been improperly reported, prosecuted, and sentenced in other parts of Mexico.[116] Regarding the crime of infanticide, both the Secretariat of Public Security and the Judiciary of the state of Mexico reported they have no records of anyone being prosecuted for this crime in that state.[117] No records related to homicide by reason of kinship were found in the state Prosecutor’s Office, the Secretariat of Public Security or the Executive Secretariat of the State Public Security System, all institutions of the state of Mexico.[118] As for the Judiciary, it registered 18 convictions for homicide by reason of kinship, none related to abortion.[119]

According to civil society organizations that provide accompaniment for women, girls and pregnant people seeking abortion care, many of them believe that it is a crime and lack information in terms of the exceptions stipulated by law. A 16-year-old girl and her mom contacted one of the civil society organizations operating in the state and interviewed by Human Rights Watch, and said they did not want to go to public hospitals because they were afraid that they could be punished.[120] The continued treatment of abortion as a crime makes women and girls afraid to even seek information on how to legally terminate their pregnancies, making effective access even more difficult.[121]

Fear of criminalization can also lead to women not seeking medical help when they need it. A representative of a civil society organization that accompanies women and pregnant people who need to access abortion services told Human Rights Watch they were contacted by Natalia, a woman who had lupus and attempted a self-managed medical abortion. She went to the hospital because she had a hemorrhage. There, health personnel insisted that her abortion was not spontaneous and aggressively interrogated her. She was frightened to tell them she had attempted a self-managed abortion, even though her abortion was legal under the risk to health grounds established in the criminal code.[122]

Fear of criminalization also leads women, girls and other people who may become pregnant not to report other crimes, including sexual violence. This was the case of Ana, who got pregnant as a result of rape and tried to get an abortion in a public hospital in the State of México. She told Human Rights Watch that the first time she sought one, a doctor told her that they did not provide this service. She then accessed a medical abortion in Mexico City. Later, when Ana went to the Prosecutor’s Office to report sexual violence, she was told she could not report it “because she had gotten an abortion and that is also a crime, and one crime cancels another crime.”[123] A representative of a civil society organization told Human Rights Watch that they have accompanied other cases of women who have described similar rhetoric at the Prosecutor’s Office.[124]

Most healthcare workers interviewed by Human Rights Watch believe that decriminalizing abortion would improve access to abortion services.[125] Removing legal restrictions would mitigate concerns among pregnant women, girls and other people regarding seeking information or accessing abortion care, especially considering there is a widespread perception that the current legal framework prohibits abortion in all circumstances. It would also mitigate concerns from healthcare workers about being criminally prosecuted when providing legal abortion care.

Conscientious Objection

Individual healthcare personnel may in some cases assert conscientious objection to refuse to perform particular treatments or procedures on moral or religious grounds. However, international law does not require states to provide for conscientious objection in health care, and a state's primary duty of care is to the individual seeking health care. That means that an assertion of conscientious objection should never result in the limitation or denial of access to health care -including abortion care- for others. If a state permits conscientious objection in health care, it must be exercisable only by individual healthcare providers, only if there are effective referral mechanisms so that it is not a barrier to accessing healthcare services. It should not be exercisable in emergency or urgent care situations and should not cause distress to those seeking medical care.

Mexican law allows the assertion of conscientious objection in healthcare settings.[126] However, in 2021, Mexico's Supreme Court set limits on the exercise of conscientious objection.[127]

Summary of the limits to conscientious objection, as established by the Supreme Court:

|

Health institutions have the obligation to have sufficient non-conscientious objector personnel to ensure the right to health. Yet, despite this requirement, there are instances where this right is not adequately protected due to a lack of non-objecting personnel.[129] For example, healthcare personnel in one of the hospitals where Human Rights Watch conducted interviews said one of their main challenges is lack of staff as there is only one non-objecting doctor who only works one shift providing abortion services, which hinders immediate care and results in women being referred to another hospital 40 minutes away.[130]

Other hospitals also face challenges in staffing, especially on shifts that are harder to cover, such as weekends. This means that people seeking abortion care during these shifts must return later.[131] Lack of staff available for abortion care leads to delays in the provision of abortion care, contrary to international human rights standards and the Supreme Court's ruling.

The need for non-objecting staff has an effect not only in the delay of service but also in access to information for women, adolescents, and other people seeking abortion care. A representative of the state Secretariat of Health told Human Rights Watch that there have been instances in which objecting personnel have refused to provide both abortion services and information about such services: “the truth is that it really depends a lot on the shift. In some other shifts they tell you [abortion services] are not done here and that’s it. It depends a lot on the person who makes the first contact with the patient too.”[132]

Medical personnel interviewed by Human Rights Watch at one hospital acknowledged that, even though the law provides that objection may not be asserted in emergencies, some health personnel still refuse to provide abortion care in those situations.[133] The Secretariat of Health plans to conduct training programs for healthcare personnel to change this situation.[134]

Capacity and Infrastructure to Provide Abortion Services

Health services in the state of Mexico include those managed by the state Secretariat of Health and those managed by federal health institutions. State-managed health services have three levels of care: health centers (first level), general hospitals (second level), and specialty hospitals (third level).

An official from the Secretariat of Health told Human Rights Watch in an interview that all three levels of care can provide abortion services, depending on their capacity. For example, not all health centers have OBGYN specialty, but they can offer medical abortions. If a case requires gynecological-obstetric specialty, the health center refers the case to the second level of care.[135]

State Health Institutions

In 2022, the federal Secretariat of Health created a program called Safe Abortion Services (SAS) as part of their effort to provide abortion care in safe conditions, with trained and sensitized multidisciplinary health personnel.[136] A representative of the state of Mexico’s Secretariat of Health told us they have worked with the federal Secretariat of Health to establish safe abortion services in the state. As of August 2024, two hospitals in the state of Mexico are registered as providers of SAS: Hospital General Cuautitlán “Gral. José Vicente Villada” and Maternidad Cuautitlán, at second and first levels of care respectively.[137]

The Secretariat of Health’s process for registering the two hospitals as safe abortion services providers included awareness-raising and staff training, which, in turn, required the availability of staff and authorities in these hospitals. Although the legislation makes it clear that access to abortion is a right in the cases provided for by law, according to the Secretariat of Health, not all hospitals that provide abortion services have been willing to participate in the activities required to register as an SAS provider.[138]

Importantly, state hospitals remain obligated to offer abortion services even if they are not registered as SAS providers. There are other hospitals that, while not federally registered as SAS providers, do offer abortion services.[139] Most health facilities have “Welfare Modules,” formerly known as “Violence Modules,” which also handle abortion access in cases of sexual violence. Out of 71 public hospitals in the state of Mexico, 64 offered abortion services in 2022 according to a directory on the state Secretariat of Health’s website.

Some hospitals have a higher number of discharges for abortion care than others. For example, in 2022, the hospitals with highest number of discharges for abortion care were Las Americas General Hospital (706 discharges), Monica Pretelini Hospital (620 discharges), and Cuautitlán General Hospital (608 discharges). The hospitals with the lowest number of discharges were San Pedro Limón Hospital (1 discharge), Zacualpan Municipality Hospital (3 discharges), and José María Coss Bicentenial (3 discharges).[140] However, the number of discharges for abortion care does not necessarily reflect access to legal and voluntary abortion services. These discharges often represent cases of obstetric emergencies rather than elective abortions.

Human Rights Watch spoke to hospitals that had both high and low numbers of discharges for abortion care. Most healthcare personnel identified the lack of non-medical personnel working at Welfare Modules as a significant barrier to providing quality abortion services. For example, psychologists are key personnel overseeing the welfare modules; however, many of them are hired on a temporary basis and, due to administrative and budgetary issues, are not employed year-round. This means that the welfare modules must operate, sometimes for months at a time, without these essential personnel.[141]

Healthcare personnel in hospitals with low numbers of discharges for abortion care told Human Rights Watch that these hospitals operate with limited staff, which is especially challenging in places where there are high numbers of objecting personnel. Lack of medical supplies or equipment forces hospitals to refer patients to other institutions. Additionally, some healthcare personnel in one of the hospitals Human Rights Watch interviewed mentioned that the context of violence and intimidation by armed groups makes people afraid to go to hospitals, hindering access.[142]

During the last few years, the budget allocated for the maternal, sexual, and reproductive health in the state of Mexico has decreased. However, it is not possible to know how much of the budget is allocated to safe abortion services in the state as the information is not disaggregated.[143]

Access and Referrals to Mexico City Health Institutions

Considering all the barriers outlined above, women, girls and pregnant people seeking abortions in the state of Mexico often go to Mexico City. Mexico City decriminalized abortion in 2007.[144] Since then, 263,267 women and pregnant people have accessed abortions services at the city's 14 abortion clinics, 180,778 from Mexico City (68.68 percent), 72,336 from the state of Mexico (27.48 percent) and the rest from other parts of the country.[145]

Health institutions in the state of Mexico often refer cases to clinics in Mexico City.[146] In Hospital General Cuautitlán pregnant women, girls and other people who seek abortions that do not fall under the legal exceptions in the state of Mexico are provided with informational pamphlets containing details about abortion and instructions on reaching hospitals in Mexico City.[147]

The state Secretariat of Health relies on an informal referral system, but often cases cannot be referred within the state. When there is resistance from health personnel to provide abortion care in hospitals in the State of Mexico in cases where abortion is legal, the local Secretariat of Health typically refers them to Mexico City, making the decision to prioritize secure transfers.[148]

However, this informal referral system does not always work, and people are denied care. This was the case of Carla, a woman who was denied legal abortion care in three different hospitals in the state of Mexico, was not given the option of a referral, and felt that her only option was to go to Mexico City.[149] Like her, many people try to go to Mexico City clinics on their own. But Mexico City is not easily accessible for everyone in the state of Mexico. Challenges include long travel times that could amount to up to eight hours and the financial cost of transportation to Mexico City, especially in areas where public transportation does not have regular service.[150] For many women and people seeking abortions, going to Mexico City means not working for an entire day. This, in a state where more than 40 percent of the population lives in conditions of poverty.[151]

Long waiting times in Mexico City’s public abortion care clinics further complicates access for people coming from the state of Mexico. People often queue outside clinics from early hours due to insufficient services to meet the demand. One civil society organization Human Rights Watch interviewed said that high demand often means women cannot access services on the day of their arrival, and that many of the women they have accompanied had to spend the night in Mexico City or make plans for future visits.[152]

Acknowledgements

This report was researched and written by Cristina Quijano Carrasco, researcher in the Women’s Rights division at Human Rights Watch. Stephanie Lustig, research assistant in the Women’s Rights division, provided research and editorial support and assistance.

It was reviewed and edited by Regina Tamés, Deputy Director of the Women’s Rights division. Expert review was provided by Elin Martínez, senior researcher in the Children’s Rights division; Margaret Wurth, senior researcher in the Children’s Rights division; Carlos Ríos Espinosa, Associate Director of the Disability Rights division; Julia Bleckner, senior researcher in the Health and Human Rights division; and Tyler Mattiace, researcher in the Americas division. Tom Porteous, deputy program director, and María McFarland Sánchez-Moreno, deputy program director, conducted program and legal review, respectively.

Shivani Mishra, senior associate in the Women’s Rights division, provided production assistance for this report’s publication. Report production was done by Travis Carr, publications officer. The report was translated into Spanish by Gabriela Haymes.

Human Rights Watch is especially grateful for the guidance and generous support provided by Grupo de Información en Reproducción Elegida (GIRE) and Dr. José Alberto Angeles Pozo, State Official for the Safe Abortion and Gender Violence Components in the state of Mexico Secretariat of Health. We are also grateful to the thirty-nine healthcare personnel across the state of Mexico, to the members of fourteen civil society organizations, and to the five government institutions who spoke with us, shared their time and insights.