Executive Summary

This report documents torture, killings, rapes, forced expulsions, and other war crimes committed by Serbian and Yugoslav government forces against Kosovar Albanians between March 24 and June 12, 1999, the period of NATO's air campaign against Yugoslavia. The report reveals a coordinated and systematic campaign to terrorize, kill, and expel the ethnic Albanians of Kosovo that was organized by the highest levels of the Serbian and Yugoslav governments in power at that time.

Naturally, these crimes did not occur in isolation. This report outlines the historical and political context of the war, with a critique of the international community's response to the developing crisis over the past decade. Three chapters also document abuses committed by the ethnic Albanian insurgency known as the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA), which abducted and murdered civilians during and after the war, as well as abuses by NATO, which failed adequately to minimize civilian casualties during its bombing of Yugoslavia. Nevertheless, the primary focus of this report is the state-sponsored violence inflicted by the Serbian and Yugoslav governments in 1999 against ethnic Albanian citizens of Yugoslavia.

The 1999 Offensive

The Serbian and Yugoslav government offensive in Kosovo that began on March 20, 1999, four days before NATO bombing commenced, was a methodically planned and well-implemented campaign. Key changes in Yugoslavia's security apparatus in late 1998, including a new head of Serbian state security and a new chief of the Yugoslav Army General Staff, suggest that preparations for the offensive were being made at that time. In early 1999, a distinct military build-up in Kosovo and the arming of ethnic Serb civilians was observed. Police and army actions in late February and early March around Vucitrn (Vushtrri) and Podujevo (Podujeve), called "winter exercises" by the government, secured rail and road links north into Serbia.

Serious violations of international humanitarian law had accompanied all previous government offensives, but the period of the NATO bombing saw unprecedented attacks on civilians and the forced expulsion of more than 850,000 ethnic Albanians from Kosovo. For the first time in the conflict, fighting moved from the rural areas to the cities.

While the government campaign seems to have been an attempt to crush the KLA, it clearly developed into something more once the NATO bombing began. With a major offensive underway, then-Yugoslav President Slobodan Milosevic took advantage of the NATO bombing to implement a plan to crush the rebels and their base of support among the population, as well as forcibly to expel a large portion of Kosovo's Albanian population.

No one predicted the speed and scale of the expulsions. Within three weeks of the start of NATO bombing, 525,787 refugees from Kosovo had flooded the neighboring countries, according to the United Nation High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). All told, government forces expelled 862,979 ethnic Albanians from Kosovo, and several hundred thousand more were internally displaced, in addition to those displaced prior to March 1999. More than 80 percent of the entire population of Kosovo-90 percent of Kosovar Albanians-were displaced from their homes.

Areas with historic ties to the KLA were hardest hit. The municipalities of Glogovac (Gllogofc) and Srbica (Skenderaj) in the Drenica region, the cradle of the KLA, were the scene of multiple massacres of civilians, as well as arbitrary detentions, torture, and the systematic destruction of homes and other civilian property. Mass killings, forced expulsions, and the destruction of civilian property were also common in the southwestern municipalities of Djakovica (Gjakove), Orahovac (Rrahovec), and Suva Reka (Suhareke), where many villages had long supported the insurgency. Sixty-five percent of the violations documented by Human Rights Watch took place in the above-mentioned five municipalities (see Figure 2 in the chapter Statistical Analysis of Violations).

Explanations for the abuses in other municipalities are more complex and less conclusive. The municipalities of Pec (Peja) and Lipljan (Lipjan), both of which had significant Serbian populations, were targeted for mass expulsion of ethnic Albanians, but killings were more localized, such as in the villages of Slovinje (Sllovi), Ribare (Ribar), Ljubenic (Lubeniq), Cuska (Qyshk), and the town of Pec. Although the KLA was active in the Pec municipality and present in the western-most part of Lipljan municipality during 1998 and early 1999, there is little or no evidence to tie the KLA to some of the villages in which massacres occurred. The killings were consistent with a broader pattern of operations to terrorize the population into fleeing Kosovo employing military, police, and paramilitary forces.

There was little KLA presence or violence during 1998 and early 1999 in the ethnically-mixed northwestern municipality of Istok, for example. Nevertheless the municipality suffered mass expulsions of its Albanian residents into Montenegro spurred by the burning and looting of their homes. Istok was also the scene of one of the bloodiest incidents of the war, when Serbian forces killed more than ninety ethnic Albanian inmates in the Dubrava prison in May 1999, after two days of NATO air strikes had killed an estimated nineteen inmates.

The forced expulsion was well organized, which suggests that it had been planned in advance. Villages in strategic areas were cleared to secure lines of communication and control of border zones. Areas of KLA support, as well as areas without a KLA presence, were attacked in joint actions by the police, army, and paramilitaries. Large cities were cleared using buses or trains and long convoys of tractors were carefully herded toward the borders. Refugees were driven into flight or transported in state organized transportation to the borders in a concerted program of forced expulsion and deportation characterized by a very high degree of coordination and control.

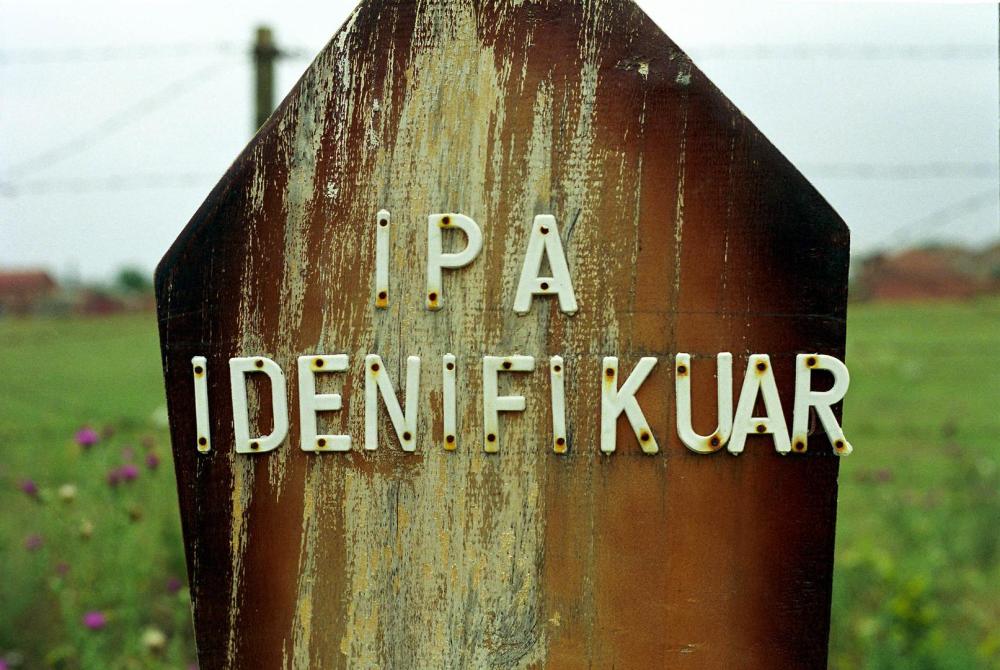

Human Rights Watch also documented the common practice of "identity cleansing": refugees expelled toward Albania were frequently stripped of their identity documents and forced to remove the license plates from their cars and tractors before being permitted to cross the border. Before reaching the border, many Albanians had their personal documents destroyed, suggesting the government was trying to block their return.

The mass expulsion of Kosovar Albanians may have served a number of purposes. First, it might have been intended to alter Kosovo's demographic composition-a policy often mentioned by Serbia's extreme nationalist politicians throughout history. Demographic shifts might also have led to an eventual partition of the province into two parts, one for Serbs and one for Albanians. Second, the expulsions might have been intended to destabilize the neighboring countries of Albania and Macedonia. Lastly, the goal might have been to tie down NATO forces in the neighboring countries, thereby hindering a ground invasion, or at least to weaken the resolve of the NATO alliance. If undercutting the international community's determination was the aim, it clearly failed, as the images of beleaguered refugees only provoked public outrage and increased calls for action.

Deliberate and unlawful killings of civilians-extrajudicial executions-were a key part of the "cleansing" campaign. Throughout the province, civilians who were clearly noncombatants, including women and some children, were murdered by Serbian police, Yugoslav army soldiers, and associated paramilitary forces in execution-style killings.

In general, the killings had three apparent motives. The first was to expedite the "cleansing" process through intimidation and fear. The second was the targeting of individuals suspected of fighting with or assisting the KLA-a distinction that was often difficult to make. Targeted individuals included some prominent political leaders, human rights activists, and wealthy businessmen. The third was killing for revenge: some massacres were committed after Serbian or Yugoslav forces suffered casualties at the hands of the KLA.

Although reliable figures are beginning to emerge, the final death toll from the Kosovo war remains unknown, and has become the focus of considerable debate. Through its own research, Human Rights Watch documented 3,453 killings by Serbian or Yugoslav government forces, but that number is definitely lower than the total, because it is based on only 577 interviews (and these interviews were not randomly sampled to allow for extrapolation of the data to all of Kosovo). At the same time, the number is certainly not as large as some Western government and NATO officials suggested during the war, when figures went as high as 100,000.

As of July 2001, the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) had exhumed approximately 4,300 bodies believed to have been victims of unlawful killings by Serbian and Yugoslav forces in Kosovo. This is certainly less than the total number of those killed by government troops. Most importantly, there is incontrovertible evidence of grave tampering and the removal of bodies by Serbian and Yugoslav troops, as the post-Milosevic Serbian government was beginning to confirm in summer 2001. Human Rights Watch documented attempts to hide or dispose of bodies in

Trnje (Terrnje), Djakovica, Izbica (Izbice), Rezala (Rezalle), Velika Krusa and Mala Krusa (Krushe e Madhe and Krushe e Vogel), Suva Reka, Slovinje, Poklek, Kotlina (Kotline), and Pusto Selo (Pastasel). In addition, 3,525 persons, including ethnic Serbs, remain missing from the conflict, according to the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC).

The statistical analysis conducted by Human Rights Watch and the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) revealed killing patterns that further expose the systematic nature of the government's campaign. When recorded extrajudicial executions are plotted over time, for example, three distinct waves emerge, as seen in Graph 5 in the chapter on Statistical Analysis of Violations. The graph is not a perfect reflection of killings since Human Rights Watch did not randomly sample the interviewees. However, the extreme nature of the waves, with three distinct surges over short periods of time, strongly suggests that the killings were not the result of random violence by government forces. Rather, they were carefully planned and implemented operations that fit into the government's strategic aims.

Likewise, the extrajudicial executions by municipality over time (Graphs 6 through 10, 14, and 15) show similar spikes in violence over short periods. Killing "sprees" tended to occur in municipalities over distinct periods, suggesting a strategic order to commit these killings in certain areas.

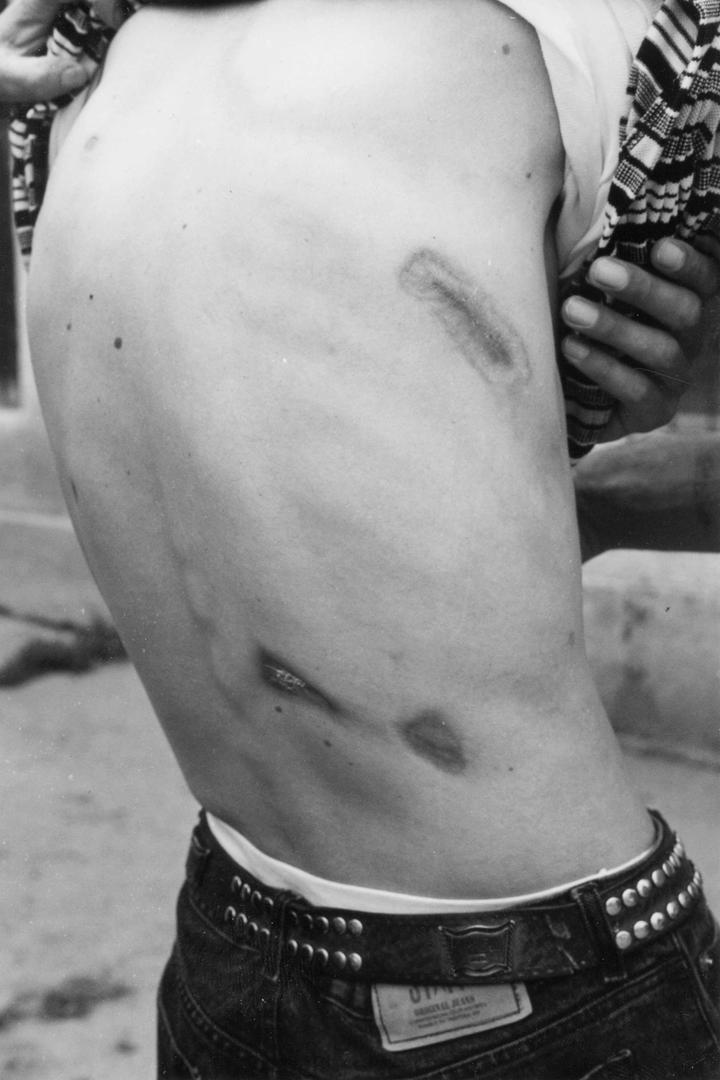

Rape and sexual violence were also components of the campaign. Rapes of ethnic Albanians were not rare and isolated acts committed by individual Serbian or Yugoslav forces, but rather were instruments to terrorize the civilian population, extort money from families, and push people to flee their homes. In total, Human Rights Watch found credible accounts of ninety-six cases of sexual assault by Yugoslav soldiers, Serbian police, or paramilitaries during the period of NATO bombing, and the actual number is certainly much higher.

In general, rapes in Kosovo can be grouped into three categories: rapes in women's homes, rapes during flight, and rapes in detention. In the first category, security forces entered private homes and raped women in front of family members, in the yard, or in an adjoining room. In the second category, internally displaced people wandering on foot or riding on tractors were stopped, robbed, and threatened by the Yugoslav Army, Serbian police, or paramilitaries. If families could not produce cash, security forces told them their daughters would be taken away and raped; in some cases, even when families did provide money, their daughters were taken away. The third category of rapes took place in temporary detention centers, such as abandoned homes or barns.

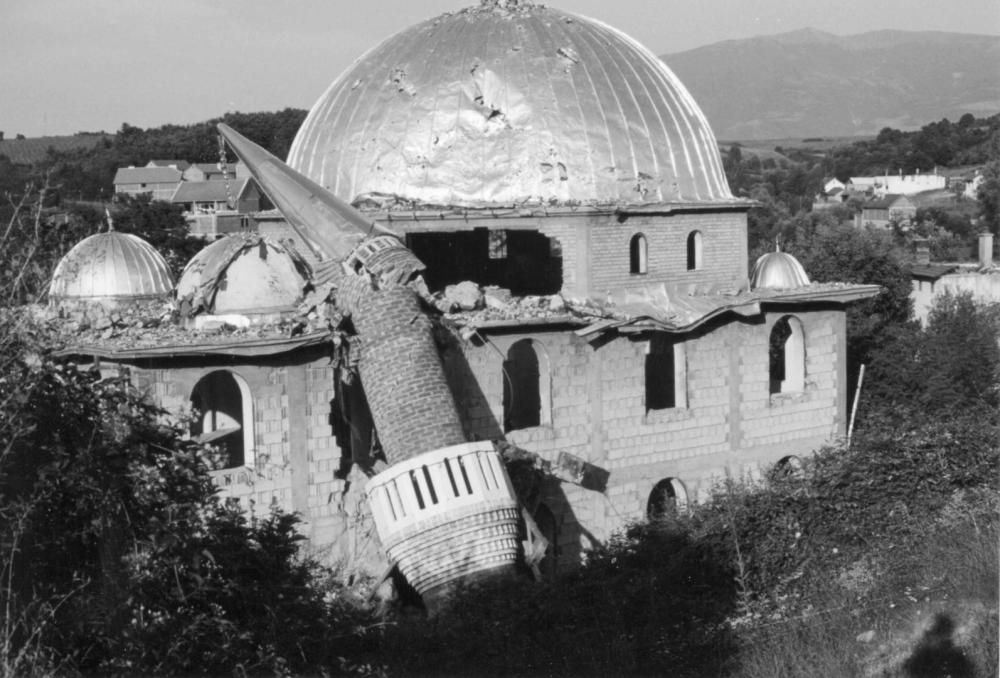

The destruction of civilian property by government troops in 1999 was widespread. According to a November 1999 UNHCR survey, almost 40 percent of all residential houses in Kosovo were heavily damaged or completely destroyed. Municipalities with strong ties to the KLA were disproportionately affected, in part because attacks against them began in 1998. But other areas without a history of KLA activity were also affected, such as the city of Pec, where more than 80 percent of the city's houses were heavily damaged or destroyed.

Schools and mosques were similarly affected. According to a United Nations damage assessment of 649 schools in Kosovo, more than one-fifth of the schools surveyed were heavily damaged and more than 60 percent were completely destroyed. Throughout Kosovo, Serbian and Yugoslav forces also deliberately rendered water wells unusable by dumping chemicals, dead animals, or human remains into the water. Human Rights Watch documented cases in four villages in which murder victims had been dumped into the water supply.

Endless witnesses and victims told Human Rights Watch how government forces robbed them of valuables, including wedding rings and automobiles, either at their homes or along the road during their expulsion. Police, soldiers, and especially members of paramilitary units threatened individuals with death if they did not hand over sums of money, usually demanding German marks. Such theft was mentioned repeatedly, even by members of the security forces who spoke with the international media after the war. For some of the men, it was the reason they went to Kosovo. Some volunteers said they were released from prison in Serbia if they agreed to serve with the army or police.

This report also documents the practice of forcing detainees to dig trenches or clear bunkers, as well as the use of civilians as human shields to protect troops from NATO or KLA attacks. The Yugoslav government also placed both antipersonnel and antitank landmines, especially along the borders with Albania and Macedonia, most probably in preparation for a ground invasion.

The Chain of Command

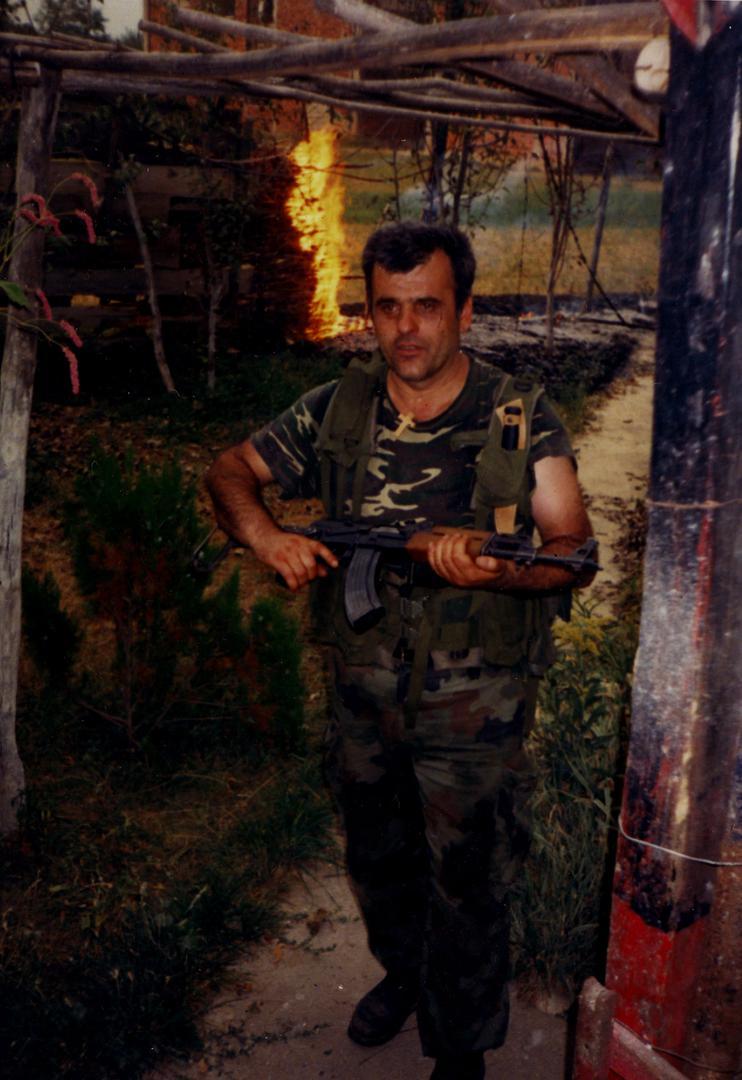

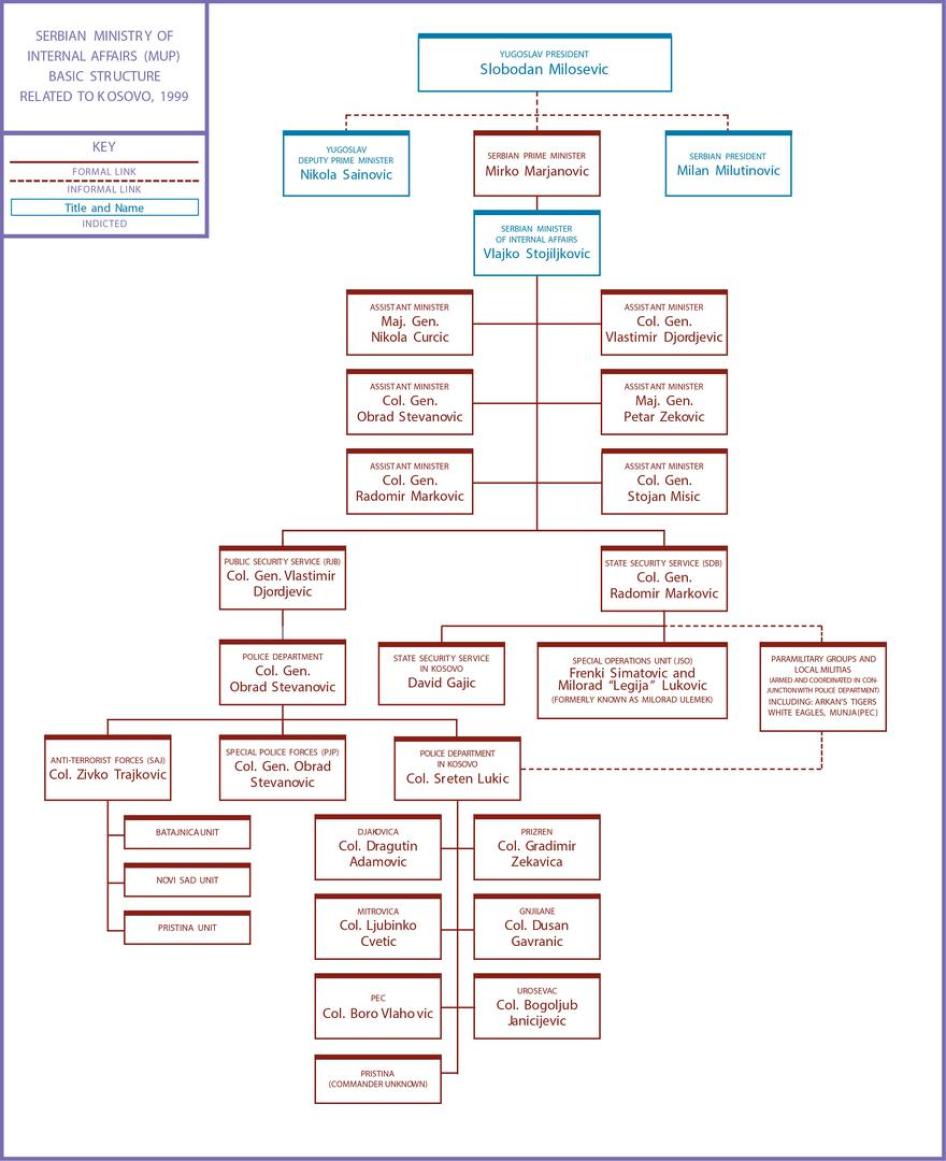

The government forces involved in the conflict were a complex combination of the Serbian Ministry of Internal Affairs police and special police, Yugoslav Army soldiers and special units, paramilitary forces, local militias, and an assortment of gunmen from abroad, all operating under orders from the government in Belgrade.

The Yugoslav Army had overall command during the period of NATO bombing, with the police and paramilitary forces subservient to its orders according to law, although top officials in the Serbian Ministry of Internal Affairs clearly exercised significant influence over the campaign. The army controlled the main roads and the borders, coordinating and facilitating the "ethnic cleansing." The police and paramilitary forces were more involved directly in the expulsion of civilians and destruction of villages, with artillery support from the army. It is during these operations that men sometimes were separated from women and children, interrogated about the KLA, and summarily executed.

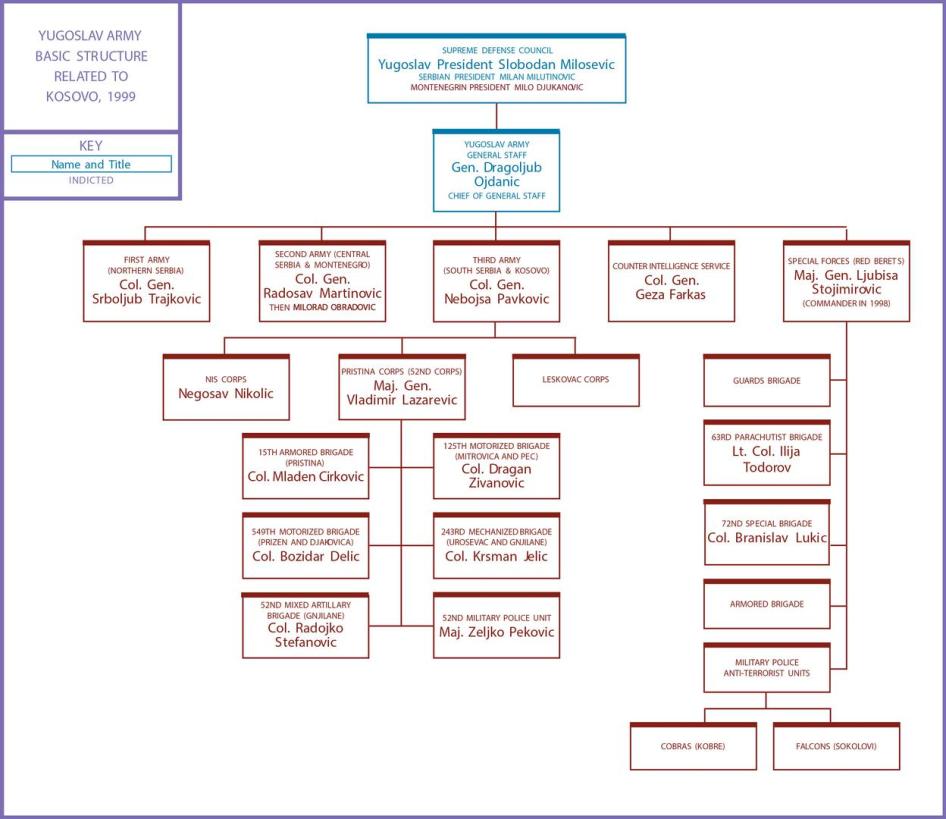

According to Yugoslav law, the Yugoslav Army (Vojska Jugoslavije, or VJ) is under the command of the Yugoslav president in both wartime and peace. Until October 2000, this was Slobodan Milosevic. The controlling body of the VJ is the Supreme Defense Council, comprised of the presidents of Serbia, Montenegro, and Yugoslavia and chaired by the Yugoslav president. The chief of the army's General Staff during the war was Gen. Dragoljub Ojdanic, who was appointed after the war to serve as Yugoslav minister of defense-the position he held until October 2000.

The VJ is divided into three armies. The Third Army, commanded during the war by Col. Gen. Nebojsa Pavkovic, was responsible for Kosovo and southern Serbia. As of August 2001, Pavkovic was Chief of the Yugoslav Army's General Staff. Under Pavkovic, during the war, was Maj. Gen. Vladimir Lazarevic, who commanded the Pristina Corps of the Third Army that was based in Kosovo. Under Lazarevic were five brigades, one military police unit, and one aviation regiment. All of their commanders are named in the chapter Forces of the Conflict.

The structure of the Serbian Ministry of Internal Affairs (Ministarstvo Unutrasnjih Poslova, or MUP), run during the war by Minister Vlajko Stojiljkovic, is more complicated than that of the VJ, which has a transparent chain of command. Within the MUP were the regular police in Kosovo commanded by Sreten Lukic, the special police (Posebne Jedinice Policije, or PJP) commanded by Lt. Gen. Obrad Stevanovic, and the Anti-Terrorist Forces (Specijalna Antiteroristicka Jedinica, or SAJ) commanded by Col. Zivko Trajkovic. Col. Gen. Vlastimir Djordjevic was head of the public security sector of MUP, as well as assistant to the minister of internal affairs. The new Serbian government replaced Djordjevic and Stevanovic in January 2001, but promoted Lukic to chief of public security as well as deputy minister of internal affairs.

The Serbian Ministry of Internal Affairs also contains the state security service, or secret police, which played a major role in Kosovo. In addition to covert activities monitoring and harassing ethnic Albanian political activists and the KLA, state security also deployed its special operations unit, the JSO (Jedinica za Specijalne Operacije), and assisted various paramilitary organizations. Also known as the "Red Berets" or "Frenki's Boys" (after Frenki Simatovic, a key personality in the Ministry of Internal Affairs who allegedly founded the group), the JSO was commanded during the war by Milorad Lukovic, a man better known as "Legija." Until January 2001, the head of the Serbian state security was Col. Gen. Radomir Markovic. He was dismissed in late January and arrested one month later by Serbian police for his alleged involvement in a 1999 attack against a Serbian politician, Vuk Draskovic. David Gajic was the head of state security in Kosovo during the war.

Lastly, various paramilitary forces as well as foreign gunmen were active in Kosovo, largely under the control of the central government. Aside from being among the most violent forces in Kosovo, one of the paramilitaries' primary activities was looting and theft.

Although the precise lines of command and control of these paramilitary forces remain unclear, they clearly cooperated closely with the Yugoslav Army and Serbian police. Paramilitary members who spoke with the international press after the war said that local officials had sometimes given them lists of ethnic Albanians to target for murder. Some men were released from Serbian prisons if they agreed to fight in Kosovo.

At times, individual members of the police or army tried to warn or protect ethnic Albanian civilians from paramilitary forces, although this was rare; more commonly, regular militias and police personnel worked closely with paramilitary units, often maintaining a cordon around targeted communities while paramilitary troops moved in.

The various units and groups within the MUP make the chain of command less discernible than with the VJ, although it is clear that ultimate authority for the MUP rested with Yugoslav President Slobodan Milosevic. According to Yugoslav law, in a declared state of war, the Yugoslav Army has jurisdiction over the Serbian police, thereby making Slobodan Milosevic the de facto and de jure commander of the police during the period of NATO bombing. Then-Yugoslav Deputy Prime Minister Nikola Sainovic also played an important role.

International law is clear on individual criminal responsibility for the leaders who organize or tolerate the commission of war crimes. Both the direct perpetrator of a crime as well as the military or political leaders who ordered that crime, or who fail to take steps to prevent a crime or to punish the perpetrator, can be held accountable.

As this report proves, the extent and systematic nature of the abuses in Kosovo make it impossible that the Serbian and Yugoslav leaderships were unaware of those violations, despite their public denials. In only a few cases were members of the security forces punished for having committed serious crimes, such as murder. On the contrary, the postwar period saw hundreds of promotions and awards for police and army personnel, including some of the top leadership, such as Dragoljub Ojdanic, Nebojsa Pavkovic, Vladimir Lazarevic, Obrad Stevanovic, Sreten Lukic, Vlastimir Djordjevic, and Zivko Trajkovic, as well as many of the brigade commanders in Pristina Corps. A complete list of those promoted and awarded is included as an appendix to the chapter Forces of the Conflict.

The War Crimes Tribunal

After a slow start in 1998, the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) began a full investigation into the war crimes committed in Kosovo. On May 27, 1999, the tribunal announced its most significant indictment to date: that of Yugoslav President Slobodan Milosevic and four other top officials for "murder, persecution, and deportation in Kosovo" between January 1 and late May 1999. The other

indictees are: Milan Milutinovic, president of Serbia and member of the Supreme Defense Council, Dragoljub Ojdanic, Chief of General Staff of the Yugoslav Army, Nikola Sainovic, deputy prime minister of the FRY, and Vlajko Stojiljkovic, Serbian minister of internal affairs. ICTY investigations of war crimes are ongoing, including a review of KLA crimes. On April 1, 2001, the Serbian police arrested Milosevic on charges of corruption. On June 28, he was transferred to the war crimes tribunal in The Hague. As of August 2001, the other indictees remained at large.

The tribunal also conducted an internal assessment of NATO actions during the war, concluding that there were no grounds for a further investigation. The Human Rights Watch assessment of NATO's air campaign differs slightly. Although Human Rights Watch found no evidence that NATO committed war crimes, it did violate international humanitarian law by taking insufficient precautions to identify the presence of civilians when attacking convoys and mobile targets. As previously reported in a February 2000 Human Rights Watch report, Civilian Deaths in the NATO Air Campaign, the NATO bombing caused the deaths of approximately 500 civilians throughout Yugoslavia. Between 56 and 60 percent of these deaths were in Kosovo. NATO's use of cluster bombs, although halted in the course of the conflict, is also criticized in this report. As inherently indiscriminate weapons when used in urban areas and because of their high failure rate, cluster bombs pose a serious and disproportionate danger to the civilian population. Between March 24 and May 7, 1999, more than 1,500 cluster bombs were dropped over Kosovo and the rest of Yugoslavia.

Abuses by the KLA

As presented in the Background chapter, the KLA was responsible for serious abuses in 1998, including abductions and murders of Serbs and ethnic Albanians considered collaborators with the state. In some villages under KLA control in 1998, the rebels drove ethnic Serbs from their homes. Some of those who remained are unaccounted for and are presumed to have been abducted by the KLA and killed. According to the International Committee of the Red Cross, ninety-seven Kosovo Serbs who went missing in 1998 were still missing as of May 15, 2000.

The KLA detained an estimated eighty-five Serbs during its July 19, 1998, attack on Orahovac. Thirty-five of these people were subsequently released but the others remain missing as of August 2001. On July 22, 1998, the KLA briefly took control of the Belacevac mine near Obilic. Nine Serbs were captured that day, and they remain on the ICRC's list of the missing.

In September 1998, the Serbian police collected thirty-four bodies of people believed to have been seized and murdered by the KLA, among them some ethnic Albanians, at Lake Radonjic near Glodjane (Gllogjan). Prior to that, the most serious KLA abuse was the reported killing in August of twenty-two Serbian civilians in the village of Klecka, where the police claimed to have discovered human remains and a kiln used to cremate the bodies. The manner in which the allegations were made, however, raised questions about their validity.

The KLA, which evolved between 1996 and 1999 from a scattered guerrilla group to an armed movement and ultimately to a more formidable armed force, engaged in military tactics in 1998 and 1999 that put civilians at risk. KLA units sometimes staged an ambush or attacked police or army outposts from a village and then retreated, exposing villagers to revenge attacks. Large massacres sometimes ensued, helping publicize the KLA's cause and internationalize the conflict.

Elements of the KLA are also responsible for post-conflict attacks on Serbs, Roma, and other non-Albanians, as well as ethnic Albanian political rivals. Immediately following NATO's arrival in Kosovo, there was widespread and systematic burning and looting of homes belonging to Serbs, Roma, and other minorities and the destruction of Orthodox churches and monasteries. This destruction was combined with harassment and intimidation designed to force people from their homes and communities. By late-2000 more than 210,000 Serbs had fled the province; most of them left in the first six weeks of the NATO deployment. Those who remained were increasingly concentrated in mono-ethnic enclaves, such as northern Mitrovica, Kosovo Polje, or Gracanica.

Most seriously, as many as one thousand Serbs and Roma have been murdered or have gone missing since June 12, 1999. Criminal gangs or vengeful individuals may have been involved in some incidents since the war. But elements of the KLA are clearly responsible for many of these crimes. The desire for revenge provides a partial explanation, but there is also a clear political goal in many of these attacks: the removal from Kosovo of non-ethnic Albanians in order to better justify an independent state.

Ethnic Albanians are not exempt from the violence. Albanians accused of "collaboration" with Serbian authorities have been beaten, abducted, or killed, notably in the municipalities of Prizren, Djakovica, and Klina. Attacks against political party activists, especially against the Democratic League of Kosovo (LDK), continued after municipal elections on October 28, 2000.

Role of the International Community

The slow response by the international community is partially to blame for the post-war violence; the U.N. and NATO failed to take decisive action from the outset to curb the forced displacement and killings of Kosovo's non-ethnic Albanian population, which set a precedent for the post-war period. In mid-1999, there were no more than a handful of U.N. police, leaving NATO's KFOR troops to perform civilian policing functions for which they were ill-prepared. NATO was largely preoccupied with protecting its own troops, rather than defending civilians. Two years after the war, a functioning judiciary system had not been established, which contributed to an atmosphere of impunity.

The familiar refrain from the United Nations is that poor security results from a lack of resources. It is true that there are insufficient funds to pay police, judges and prosecutors. But the more fundamental shortcoming is the lack of political will. Senior NATO and U. N. officials know that persons linked to the former KLA, including some of Kosovo's key political figures, are implicated in violence against minorities and in criminal activities, but they have chosen not to confront them.

The international community's errors in this regard are hardly their first in Kosovo. In the Background chapter, this report tracks the international community's response to the conflict since 1990. The West failed to support the Kosovar Albanians' peaceful movement from 1990 to 1998, concerned during the wars in Bosnia and Croatia with keeping Kosovo out of the headlines. The West essentially watched as the KLA emerged, the Yugoslav state responded forcefully, and the province slid toward armed conflict.

Throughout the conflict, the international community failed to develop a unified position to resolve the crisis. Slobodan Milosevic used this disharmony to his advantage, appearing to deal with one state, and then another, all the while buying time to advance his campaign. Members of the international community took advantage of the disunity as well, pointing to each other as the excuse for inaction. In the instances in which the international community strongly condemned the violence, words and symbolic action proved meaningless, with deadlines postponed, conditions abandoned, and sanctions poorly enforced or even withdrawn.

The report concludes that the international community's interest in preserving its political settlement in Bosnia and an allergy to altering international borders blinded it to the imperative of halting abuses before they escalated into open warfare. If the international community wanted to promote territorial integrity in the Balkans, it should have pressed for the national unity that comes from respect for the rights of all citizensÑa respect that had been sorely lacking in Kosovo as well as in other parts of the Balkans. Permitting serious abuses to go unchallenged led to the regional instability that the international community had sought to avoid.

In the end, primary blame for the Kosovo tragedy must be placed on former Yugoslav President Slobodan Milosevic and the then-Serbian and Yugoslav leadership, who not only failed to seek any peaceful compromises with the Albanians in Kosovo, but also devised and implemented a violent campaign against armed insurgents and civilians alike. As this report shows, all evidence points to their direct involvement in war crimes of the most serious nature.

The autumn 2000 electoral victory of the Democratic Opposition of Serbia (DOS) opened the door for change in Serbian and Yugoslav society and a peaceful resolution to long-standing conflicts in the region. But lasting stability in Kosovo, Serbia, and the region will not be achieved without accountability for past crimes committed by all sides.

Background

Introduction

In 1989, when the Serbian government revoked Kosovo's status as an autonomous province within the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, political analysts and activists in that country and abroad anticipated deterioration. "A lit fuse," "a powder keg," and other clichés were used to describe the prospect of armed conflict in the province and the country.

The danger became more apparent with each passing year, even though the wars that engulfed the other parts of the former Yugoslavia did not spill over into Kosovo. Serbian government oppression against Kosovar Albanians intensified and, seeing no potential for improvement, the ethnic Albanians gradually lost faith in the nonviolent politics that they had pursued since 1990. By late 1996, a previously unknown guerrilla group called the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) began coordinating attacks against the Serbian police. The government responded with indiscriminate force and the downward cycle of violence had begun.

Despite the repeated warning signs during the decade, the international community failed to stop a predictable conflict. Short-term and piecemeal political tactics took precedence over long-term strategic policy. Divisions and competition between governments and international bodies made unified action weak and directionless-characteristics that the Milosevic government craftily exploited.

Serious and unified international engagement came only after the conflict had deteriorated into full-scale war. Faced with limited options at that point, the West chose military action by NATO-the so-called "humanitarian intervention" in 1999.

Taking advantage of the NATO bombing, Serbian and Yugoslav forces "ethnically cleansed" more than 850,000 Kosovar Albanians, and killed thousands more. The NATO bombing eventually forced government troops out of the province, but not before serious war crimes had been committed-atrocities which continue to poison Kosovo's post-war environment.

The pages of graphic human rights testimony in this report are one result of the West's failures in dealing with this foreseeable crisis. The large-scale expulsions and killings of Serbs and Albanians, even after the entry of NATO into Kosovo, provide a crucial lesson: left unattended, government oppression and human rights abuses, especially against minority populations, can easily produce violent confrontations that result in more serious abuse. Put another way, genuine and lasting stability in the Balkans is impossible without democratic governments respectful of human rights.

There have been many debates over what the international community could have done to stop Kosovo's violence. One fact is clear: the international community could have implemented creative economic and political measures designed to halt the Yugoslav government's abusive behavior against civilians. The cost of such measures would surely have been less than that of NATO's intervention and the subsequent U.N. mission in Kosovo.

What follows is a chronology of Kosovo's downward spiral and the international community's missed opportunities.

Brief History of the Kosovo Conflict

One must go back centuries to address fully the relationship between Albanians and Serbs and their struggles in Kosovo. Both consider the province central to their cultures and political well-being, and have proven willing to fight for control of the region. Keeping Kosovo and its historic sites a part of Serbia has become a centerpiece of Serbian nationalist policy. Violent confrontations have marked the area's history, although Albanians and Serbs have also fought as allies on occasion. Mutual accusations of atrocities in the Balkan Wars, World War I, and World War II, as well as battles long before, cloud the region's history.

While this background is central to understanding the conflict, and the region's history plays an important role in contemporary affairs, historical debates are secondary to the more recent developments that influenced the Kosovo war. Selective versions of history and past grievances provided fertile ground for opportunistic politicians in the 1980s and 1990s to exploit the fears and frustrations of Albanians and Serbs. History was abused by aggressive nationalist politicians who benefited by promoting hatred, xenophobia, militarization and, ultimately, war.

Kosovo in the Socialist Federal _Republic of Yugoslavia

After World War II, the federal constitution defined ethnic Albanians in Yugoslavia as a "nationality" rather than a constituent

"nation," despite being the third largest ethnic group in the country. This was a status distinct from that of the other major ethnic groups in the country-Serbs, Croats, Bosnians, Slovenes, and Macedonians. Still, Yugoslavia provided a semblance of minority rights to all ethnic groups in the name of socialist "brotherhood and unity."

Kosovo was the poorest region in Yugoslavia. With the exception of the bountiful Trepca mines, most of the province is agricultural. Poverty and underdevelopment among all ethnic groups in Kosovo exacerbated tensions. Some improvements came after student demonstrations in the late sixties, such as increased public investment, the opening of a university in Pristina, and the recruitment of Kosovar Albanians into the local administration.

Endeavoring to strike a better balance among the country's competing ethnic groups-and to check the power of Serbia within the federation-Yugoslav leader Josip Broz Tito orchestrated a new constitution in 1974 to provide two regions in Serbia with more autonomy: Kosovo and Vojvodina (with a large ethnic Hungarian population). Although they did not achieve the status of federal republics like Bosnia, Croatia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, and Slovenia, the two provinces were declared "autonomous regions," which gave them representation in the federal presidency alongside Yugoslavia's republics, as well as their own central banks, separate police, regional parliaments and governments. Ethnic Albanians were brought into some of the ruling elite's inner circles.

Ethnic Albanians, who made up approximately 74 percent of the Kosovo population in 1971, took most key positions of power in Kosovo and controlled the education system, judiciary, and police, albeit under control of Tito and the Communist Party, which was the dominant political force in the country. The Albanian-language university in Pristina, opened in 1970, was promoted by the authorities.

Kosovo's autonomy was never embraced by a wide sector of the Serbian ruling elite, which viewed it as a threat to Serbia's interests and sovereignty. Autonomy for Kosovo and Vojvodina, some argued, had diluted Serbia's power in Yugoslavia. Criticism was muted during the seventies, but began to mount after Tito's death in 1980. The following year, ethnic Albanians, led by university students initially discontented with bad food and poor dormitory conditions, took to the streets to demand higher wages, greater freedom of expression, the release of political prisoners, and republic status for Kosovo within Yugoslavia. Their demonstrations were dispersed forcibly by the Yugoslav Army and federal police, resulting in a number of ethnic Albanian deaths and numerous arrests over the ensuing months. Some political prisoners from that time, together with young men who fled Kosovo to avoid arrest, later formed the radical emigre groups in Western Europe that evolved fifteen years later into the KLA.1 A new ethnic Albanian communist leadership was installed by Belgrade. From 1981 on, pressure grew in Serbian political circles to rein in what was viewed as a growing "Albanian secessionism."

Treatment of Non-ethnic Albanians

Throughout the late 1970s and 1980s, Kosovo's Serbs complained of harassment and discrimination by the ethnic Albanian population and leadership, with the intention, Serbs claimed, of driving them from the province. According to a report submitted to the influential Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts in 1988, more than 20,000 ethnic Serbs moved out of Kosovo in the years 1981-1987.2 Albanians claim that Serbs left for economic reasons because Kosovo remained Yugoslavia's poorest province.

Ethnic Serbs and other minorities, such as Turks and Roma, were subjected to harassment, intimidation, and sometimes violence by extremist members of the ethnic Albanian majority. The government in Kosovo, run by ethnic Albanians, did not take adequate steps to investigate these abuses or to protect Kosovo's minorities against them.3

At the same time, the ethnic Albanian population was consistently growing with Kosovar Albanians having the highest birthrate in Europe, resulting in what the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts called, "heavy pressure not only on available resources, but also on other ethnic groups."4

The Rise of Serbian Nationalism

The mid- and late-eighties were marked by a distinct rise in Serbian nationalism, especially among Serbs living outside of Serbia proper, who felt increasingly isolated and threatened by the nationalism that was rising around them in Croatia, Bosnia, and Kosovo. The most vocal were Serbs in Kosovo who complained about their mistreatment at the hands of ethnic Albanians.

In September 1986, a document from the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts was published that addressed "the Serbian question" in Yugoslavia. Known as the Memorandum, the document attacked Serbian politicians for doing nothing in the face of threats, attacks, and even "genocide" against the Serbs of Kosovo. Among other inflammatory claims, the Memorandum stated:

The physical, political, legal, and cultural genocide of the Serbian population of Kosovo and Metohija is a worse historical defeat than any experienced in the liberation wars waged by Serbia from the First Serbian Uprising in 1804 to the uprising of 1941.5

Criticized by then-Serbian President Ivan Stambolic, the Memorandum reflected a common, albeit unspoken, sentiment among the Serb populace. With communism failing as an ideology, Serb politicians began to harness this discontent for their own political means.

No politician understood this better than Slobodan Milosevic, by that time communist party chief of Serbia. A communist apparachik and Stambolic protegé, Milosevic grasped the potency of fear and nationalism to fuel his own rise to power.

On April 24, 1987, Milosevic was sent to address a crowd of Kosovo Serbs in Kosovo Polje who were protesting maltreatment by Albanians. He rallied the demonstrators with the exhortation that: "No one should dare to beat you!" The phrase was repeated frequently on the Serbian state television that was under Milosevic's control and became a rallying cry for Serbian nationalists. Making the conversion from communist to nationalist, Milosevic continued:

You should stay here. This is your land. These are your houses. Your meadows and gardens. Your memories. You shouldn't abandon your land just because it's difficult to live, because you are pressured by injustice and degradation. It was never part of the Serbian and Montenegrin character to give up in the face of obstacles, to demobilize when it's time to fight . . . You should stay here for the sake of your ancestors and descendants. Otherwise your ancestors would be defiled and descendants disappointed. But I don't suggest that you stay, endure, and tolerate a situation you're not satisfied with. On the contrary, you should change it with the rest of the progressive people here, in Serbia and in Yugoslavia.6

With determined precision, Milosevic used his new found nationalist populism to eliminate political opponents, including Stambolic.7 The state media, especially the Serbian Radio and Television (RTS), purposefully spread misinformation on abuses against Serbs in Kosovo, including the rape of Serbian women, and campaigned to promote negative images of Albanians. Over the next two years, massive gatherings were held in Yugoslavia called the "Rallies of Truth" in which Milosevic invoked Serb glory and demanded constitutional changes to revoke Kosovo's autonomy. In one such rally, Milosevic said:

We shall win the battle for Kosovo regardless of the obstacles facing us inside and outside the country. We shall win despite the fact that Serbia's enemies outside the country are plotting against it, along with those in the country. We tell them that we enter every battle_._._._with the aim of winning it.8

Ethnic Albanians organized their own strikes and public protests against the growing restrictions and repression in the province. Unlike the rallies in Serbia proper, the Albanian demonstrations were often broken up by force, and many ethnic Albanians were arrested. On November 17, 1988, the Kosovo communist party leadership was dismissed. A few days later, Kosovar Albanian miners went on strike at the Trepca mines near the town of Kosovska Mitrovica. On November 25, the Federal Parliament passed constitutional amendments that paved the way for changes to the Serbian _constitution. Azem Vllasi, the communist party chief of Kosovo and then the leading ethnic Albanian politician at the Yugoslav federal level, was dismissed.

On February 20, 1989, the Trepca miners struck again, demanding the reinstatement of the Kosovo party leaders. The government deployed the army and imposed "special measures" on the region, which amounted to a form of martial law. An atmosphere of fear prevailed in the province, especially among ethnic Albanian political leaders and intellectuals. The other Yugoslav republics, especially Slovenia, began to protest Serbia's aggressive nationalism.

After a massive pro-Milosevic rally in Belgrade, Vllasi was arrested on March 2.9 Three weeks later, a new Serbian constitution was announced. The Kosovo assembly-mostly ethnic Albanians but under direct pressure from Belgrade-accepted the proposed changes to the Serbian constitution which returned authority to Belgrade.

While Belgrade celebrated, Kosovar Albanians vehemently protested the changes. On March 28, 1989, riot police opened fire on a protesting crowd, killing at least twenty-four persons. Although government forces may have come under attack, the state's response was indiscriminate and excessive. A joint report by Helsinki Watch and the International Helsinki Federation for Human Rights at the time found that there was "no justification for firing with automatic weapons on the assembled crowds."10

Riding an ever stronger wave of nationalism, Slobodan Milosevic was elected president of Serbia on May 8, 1989, a post he held for the next eight years, until he was elected president of Yugoslavia on July 23, 1997-the position he held until October 2000.

In July 1989, the Serbian parliament passed the Law on the Restriction of Property Transactions, the first in a series of laws that severely discriminated against ethnic Albanians in Kosovo. The law forbade Albanians to sell real estate without the approval of a special state commission run by the Serbian Ministry of Finance. On March 30, 1990, the Serbian government adopted a new program that laid the ideological foundation for the government's policy in Kosovo. Ironically called, "The Program for the Realization of Peace, Freedom, Equality, Democracy, and Prosperity of the Socialist Autonomous Province of Kosovo," the program stated:

The autonomy of Kosovo may not serve as an excuse or reason for the malfunctioning of the legal state and possible repetition of nationalistic and separatist unrest and persistent inter-ethnic tension. It may not be misused in pursuit of unacceptable and unfeasible goals: prevention of the return of Serbs and Montenegrins, displaced under pressure, and all the others who wish to come and live in Kosovo, and especially for any further emigration of Serbs and Montenegrins and secession of a part of the territory of the Republic-the state of Serbia so as to constitute a new state within or without Yugoslavia.11

Kosovo in the 1990s

The Revocation of Kosovo's Autonomy

On July 2, 1990, ethnic Albanian members of Kosovo's politically gutted assembly declared Kosovo's independence. Two months later, on September 7, members of the parliament, which had been dissolved on July 5, met secretly and adopted a new constitution of the Republic of Kosova. A clandestine government and legislature were elected. Three weeks later, on September 28, the Serb Assembly promulgated the new Serbian constitution that formally revoked the autonomous status of both Kosovo and Voj-_vodina.

The new Serbian constitution was important because, by formally revoking the autonomy of Kosovo and Vojvodina, Serbia assumed two additional seats in the eight-member Yugoslav presidency. In coalition with its partner Montenegro, the "Serbian Block" controlled half of the federal body.

In September 1991, Kosovar Albanians held an unofficial referendum on independence. Ethnic Albanians voted overwhelmingly for independence from Yugoslavia. The Yugoslav government refused to recognize the results. Only the government in Albania, at that time still ruled by the communist party, recognized Kosovo's independence.12

Human Rights Abuses in the 1990s

Kosovo became a police state run by Belgrade. A strong Serb military presence, justified by the need to fight "Albanian secessionists," committed ongoing human rights abuses. Police violence, arbitrary detentions, and torture were common. Ethnic Albanians were arrested, detained, prosecuted, and imprisoned solely on the basis of their ethnicity, political beliefs, or membership in organizations or institutions that were banned or looked upon with disfavor by the Serbian government.13

Hundreds of thousands of ethnic Albanians were fired from government institutions and state-run enterprises under a series of discriminatory laws. Already in August 1990, the Serbian parliament had abolished the independence of the Kosovo educational system and instituted a new curriculum to be administered centrally from Belgrade. Albanian teachers were forced to sign a loyalty oath; those who refused were dismissed. Throughout 1990, the government closed most of the Albanian-language schools and, in January 1991, it stopped paying most Albanian high school teachers. By October 1991, all Albanian teachers had been fired; only fifteen Albanian professors remained at the university in Pristina, and they all taught in Serbian.

The deliberate economic and social marginalization of ethnic Albanians forced the emigration of an estimated 350,000 Albanians from the province over the next seven years. While Albanians were being forced to leave, Milosevic's government provided incentives and encouraged the settlement of Serbs in the region. In 1996, 16,000 Serb refugees from Bosnia and Croatia were settled in Kosovo, sometimes against their will.14

The Yugoslav government maintained that the military presence and legal measures were necessary for two reasons: to protect Kosovo's minority populations-principally Serbs and Montenegrins-and to contain the Albanian successionist movement. Such a movement, the government argued, would seek Kosovo's independence from Yugoslavia, and possible unification with neighboring Albania. The government's actions with regard to both concerns were extreme and produced violations of human rights.

Albanian Non-Violence and the Parallel State

Kosovar Albanians responded to the revocation of autonomy by creating their own parallel state which was, based on the September 1991 referendum, declared independent from Yugoslavia. Albanian deputies of the dissolved parliament established "underground" institutions of government, and Kosovar Albanians refused to recognize the Serbian state.

A parallel system of private schools was set up with donated funds and taxes. For eight years, Albanian school children and university students attended classes in private homes, empty businesses, and abandoned school buildings. Teachers, students, and administrators in the private schools were routinely harassed, detained, and beaten by the police and security forces. Funds collected for educational purposes were sometimes confiscated by the police.

Underground parliamentary elections on May 24, 1992, established the three-year-old Democratic League of Kosova (Lidhja Demokratike te Kosoves, or LDK) as the strongest ethnic Albanian party and a previously little-known literary figure, Ibrahim Rugova, was named president. The LDK expanded the parallel system and established structures to collect taxes from Albanians in Kosovo and from the ever-growing diaspora community.15 Rugova and a prime minister, Bujar Bukoshi, represented the "Kosova Republic" abroad.

The revocation of Kosovo's autonomy and the subsequent abuses garnered little response from the international community, which was increasingly preoccupied with the growing conflict in Slovenia, Croatia, and then Bosnia. In the summer of 1992, the Conference for Security and Cooperation in Europe (now the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE)) sent missions to Kosovo, Vojvodina, and Sandzak, but the missions were forced to leave in July 1993 when the Yugoslav government refused to renew the mandate.

In December 1992, after Serbian special police forces had enforced rule in Kosovo, U.S. President George Bush issued what became known as the "Christmas Warning." Bush reportedly wrote, in a letter to President Milosevic, that the U.S. would be "prepared to employ military force" in the event of conflict in Kosovo caused by Serbian action-a warning that was repeated by President Clinton when he came to office a few months later.16 Kosovar Albanians interpreted the warnings as a message that the U.S. would come to their defense.

Largely out of a realistic assessment of ethnic Albanians' military capabilities, the LDK declined offers from the Croatian and Bosnian leadership to open another military front against Serbia.17 While calling for Kosovo's independence, the LDK preached nonconfrontation and urged Albanians to support the parallel structures.

The exception was an attempt in 1992 and 1993 to set up a Kosovar Ministry of Defense, with its own forces made up mostly of former policemen. The Serbian police crushed the nascent group through large-scale arrests in 1993, and no armed movement was discernible again until the emergence of the KLA in 1996.

The United States and West European governments strongly encouraged ethnic Albanians to pursue a moderate approach, fearing that a conflict in Kosovo would spin out of control and engulf the region. The primary goal was to avoid a conflagration in Kosovo, and non-confrontation, the West believed, was the best way to achieve this.

Rugova was identified as the prime advocate of this moderate line and received the unconditional support of Western governments, especially the United States. He was frequently invited for high level meetings in Washington and West European capitals which greatly boosted his popularity among the strongly pro-Western Kosovar Albanian public. At the same time, however, Western governments never expressed support for Kosovo's independence, although most Kosovar Albanians believed the West did so.18

In some respects, Rugova and Milosevic derived benefits from each other. Milosevic tolerated Rugova because Rugova allowed the Kosovar Albanians an outlet for their frustrations and a public expression of their political will, while his nonconfrontational policies excluded a challenge to Serbian rule over the province. Albanians also continued paying taxes to the Serbian government. At the same time, Milosevic's repressive policies helped justify the Albanians' drive for independence.19 The West was comfortable with this arrangement because it helped guarantee the status-quo. Human rights abuses continued, but Kosovo stayed off the front pages while the West was dealing with the fighting in Croatia and Bosnia.

At the same time, West European governments and the U.S. were providing strong financial and political support to the government of Sali Berisha in Albania, partly because Berisha supported Rugova and promised not to meddle in the affairs of Kosovo or Macedonia. Unqualified support for Berisha, despite his clear pattern of human rights violations against Albanian citizens, greatly contributed to the eventual destabilization of Albania which, in turn, negatively affected Kosovo.20

Meanwhile, thousands of Kosovar Albanian men were leaving Kosovo for the United States and Western Europe due to ongoing persecution or fear of being drafted into the Yugoslav Army. Many of these disenfranchised young men abroad and in Kosovo, without education or steady employment, later joined the insurgency.

The Downward Cycle of Violence

A crucial shift came after the Dayton conference in December 1995 that stopped the fighting in Bosnia. Kosovar Albanians were not invited to the conference, and Kosovo was kept off of the agenda. This left many Kosovar Albanians with the impression that the West had forgotten the Kosovo issue and that their peaceful approach was not working. Furthermore, with international recognition for the new borders of the Republika Srpska, Albanians understood that the international community responded to the facts on the ground rather than high-minded principles of nonviolence-not the force of argument but the argument of force.21

In early 1996, the first organized violence took place against Serbian civilians and police. Although individual attacks had occurred before then, the first coordinated attack occurred on February 11, when grenades were thrown at the gates of Serbian refugee camps in Pristina, Mitrovica, Pec, Suva Reka, and Vucitrn. No one was injured.

On April 21, 1996, an ethnic Albanian student, Armend Daci, was shot and killed in Pristina by a local Serb who reportedly thought Daci was breaking into his car. The next day, four assassinations of Serbs took place within one hour.22 That same night, in the village of Stimlje (Shtimje), policeman Miljenko Bucic was killed, and a police car was attacked by machine gun on the road between Mitrovica and Pec, killing a Serbian woman who was in custody. Revenge for the Daci killing was generally considered the motive for these attacks, but post-war interviews with KLA leaders revealed that the April 22 actions had been planned in advance.23

In this climate of increasing violence, Milosevic allowed the U.S. government to open a U.S. Information Agency office in Pristina, which was welcomed warmly by Kosovar Albanians as a sign of increased American involvement. The office, considered wrongly by some Albanians as an embassy, was announced in early February and opened in July 1996.

Violent attacks on Serbian police continued throughout the summer and fall of 1996, resulting in four deaths and two injuries.24 Kosovar Albanian leaders and Serbian officials both denied any involvement in the violence and accused the other side of provoking conflict. Rugova, unconvincingly, claimed that the attacks were committed by the Serbian secret police in order to provoke retaliation against Albanians.

Meanwhile, a previously unknown organization called the Kosovo Liberation Army claimed responsibility for the attacks. In letters faxed to the media, the group criticized the "passive" approach of the ethnic Albanian leadership and promised to continue their attacks until Kosovo was free from Serbian rule.

By mid-1996, there was a clear pattern of arbitrary and indiscriminate retaliation by the Serbian police and special security forces against ethnic Albanians who lived in the areas where KLA attacks were taking place. Police broke into private homes without warrants and detained ethnic Albanians, often abusing them physically. Many individuals traveling through the areas of suspected KLA activity were stopped, interrogated and beaten. In October, the police arrested forty-five ethnic Albanians who, they claimed, were involved in the attacks.25

In the West, Milosevic continued to be viewed as a necessary partner for regional stability because of the Dayton Accords. The concern in Washington and West European capitals was that Milosevic should not be challenged on Kosovo because he was needed to implement the accords. Fear of attacks on Western soldiers deployed in Bosnia to monitor and enforce the agreement reinforced the West's reluctance to alter the status-quo in Kosovo. Human rights abuses were deemed acceptable in the name of regional stability.

At the same time, the Western military presence in Bosnia was unwilling to arrest the leading individuals indicted for war crimes by the U.N.'s war crimes tribunal, notably Bosnian Serb leader Radovan Karadzic and General Ratko Mladic. Their arrest might have sent a message that the West would not tolerate further violent and abusive behavior in the Balkans, deterring Serbian forces from atrocities in Kosovo.

The next important political development came on September 1, 1996, when Rugova and Milosevic signed a much-heralded education agreement that envisaged unconditional return to Albanian-language schools for ethnic Albanian pupils, students, and teachers.26 The details were to be worked out by a joint commission of three Serbs and three Albanians. Despite the international fanfare, the agreement was never implemented, and ethnic Albanian pupils remained locked out of most school buildings. The harassment, beatings, and arrests of ethnic Albanian teachers and school administrators continued.

The failure of the education agreement to bring any concrete improvements in the daily lives of Kosovar Albanians was a serious blow to Rugova's peaceful politics. Ethnic Albanians were losing faith in his increasingly empty promises that the West would help. The inability or unwillingness of the West to reward Albanians' patience and nonviolence with concrete improvements, such as in education, helped push the community closer to the military option.

On September 31, 1996, the U.N. lifted sanctions on Yugoslavia that had been in place since May 1992, and many European states upgraded diplomatic relations with Yugoslavia. European Union countries began to reestablish diplomatic relations with Belgrade-broken during the war in Bosnia. France, Italy, and Greece restored a high level of economic relations.

The main exception was the U.S. insistence on maintaining the so-called "outer wall" of sanctions, which, most importantly, kept Yugoslavia out of international financial institutions such as the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. The sanctions were to stay in place, the U.S. government said, until, among other things, the Kosovo issue was resolved.27

Human rights abuses in the province intensified toward the end of 1996 as the government attempted to weed out the growing insurgency. Police acted with near total impunity as they maltreated, and occasionally killed, ethnic Albanians. Police abuse generally took three basic forms: random beatings on the streets and other public places, targeted attacks against politically active ethnic Albanians, or arbitrary retaliation for KLA attacks on Serbian policemen.28

Publicly, the Serbian government continued to deny that human rights violations existed and officials defended the need to protect the sovereignty of the state. In July 1996, Serbian Deputy Minister of Information Rade Drobac told Human Rights Watch: "The situation of human rights is excellent in Kosovo. Albanians have more rights than anywhere in the world."29 At the same time, ethnic Albanians did not drop their demand for full independence, and the KLA continued its attacks.

The international community was trapped on the one hand by its general desire to stop the Serbian government's violations and a distaste for Kosovo's potential independence on the other. An independent Kosovo, it was argued, would join Albania and, eventually, the Western part of Macedonia, which is predominantly inhabited by ethnic Albanians. In the very least, an independent Kosovo would disrupt the delicate balance between ethnic Macedonians and ethnic Albanians in Macedonia, considered a young and fragile state.30 Most Western governments also feared the precedent that Kosovo's independence would set for ethnic separatist movements in other countries, such as those of the Basques and Corsicans.

To tread the middle line, the international community called for increased minority rights in Kosovo and encouraged dialogue between Serbs and Albanians through a variety of channels. A political settlement on autonomy within Yugoslavia, the West hoped, was still attainable, despite the escalating violence and abuse.

At the end of 1996, the political scene inside Serbia changed. In municipal elections on November 17, opposition parties won in fourteen of Serbia's nineteen largest cities. The government declared "unspecified irregularities" in those areas where the ruling party had lost, sparking eighty-eight days of peaceful demonstrations by opposition party supporters and students, some of which were broken up forcibly by the police.31 The government recognized the election results on February 22, 1997, but it did so without losing power on the national scene. Internal bickering and power struggles quickly weakened the opposition's power and support.

Although most western governments criticized the 1996 electoral violations and the ensuing police abuse, many states continued welcoming Yugoslavia back into the international community. In April 1997, the European Union offered Yugoslavia preferential trade status-which grants a country beneficial conditions when trading with E.U. states-despite the ongoing abuses in Kosovo. On May 15, the European Commission approved an aid package to Yugoslavia worth U.S. $112 million. Such concessions squandered a prime source of leverage that the international community had to press for improvements in Milosevic's human rights record, repression in Kosovo, and the government's compliance with the Dayton Accords.

Growth of the Kosovo Liberation Army

The KLA continued its attacks against Serbian policemen and civilians in early 1997, especially in the more rural areas, although the group's size, structure, and leadership remained a mystery. The insurgency's impact was limited by restricted access to arms.

This changed with the dramatic 1997 events in Albania. By March, the so-called "pyramid schemes" (linked with money laundering and other illegal activities) that the Albanian government had allowed to flourish collapsed, creating mayhem throughout the country. In the ensuing lawlessness, weapons depots were looted and, in some cases, opened by the government. More than 100,000 small arms, mostly Kalashnikov automatic rifles, as well as some heavier weapons, were readily available for prices as low as fifty German Marks. Many of these arms found their way across the northern border into Kosovo.

By late 1997, the central region of Drenica was known among ethnic Albanians as "liberated territory" because of the strong KLA presence. Serbian police only ventured into the area during the day.

The still-loosely organized guerrillas made their first public appearance on November 28, 1997, at the funeral of a Kosovar Albanian teacher, Halit Gecaj, who was killed by a stray bullet during fighting with Serb police in the village of Lausa (Llaushe). In front of an estimated 20,000 mourners, three masked and uniformed KLA fighters, two of whom reportedly took off their masks, addressed the crowd.32

Around this time, Kosovar Albanian students began organizing peaceful demonstrations in Kosovo's cities to demand the implementation of the 1996 education agreement and the reopening of the Albanian-language university. Some of the nonviolent protests were broken up forcibly by the police. For many people, Albanians and Serbs, the peaceful student movement was the last chance to avoid an outright armed conflict in the province.

The international community condemned the rising state violence in Kosovo while stressing its respect for the territorial integrity of Yugoslavia. At the same time, most West European governments, as well as the U.S., condemned as "terrorist actions" the KLA attacks. A February 1998 statement of the Contact Group on former Yugoslavia-comprised of the U.S., Germany, France, Russia, Italy, and the U.K.-stated:

The Contact Group reaffirmed its commitment to uphold human rights values, and their condemnation of both violent repression of non-violent expressions of political views, including peaceful demonstrations, as well as terrorist actions, including those of the so-called Kosovo Liberation Army.33

In late February, President Clinton's special representative, Robert Gelbard, visited Yugoslavia to address, among other issues, the brewing Kosovo crisis. During a press conference in Pristina on February 22, he declared that "the UCK [KLA] is a terrorist group by its actions. I used to be responsible for counter-terrorist policy in the American government. I know them when I see them."34

Gelbard reiterated his condemnation of the KLA in a Belgrade press conference the next day, and also announced some concessions to the Yugoslav government due to cooperation in Bosnia. Consistent with the view that Milosevic was a necessary ally for the implementation of the Dayton Accords, Gelbard said that the U.S. had been "particularly encouraged by the support that we received from President Milosevic," although, Gelbard added, "we still have a large number of areas where there are differences in views." In order to encourage "further positive movement," Gelbard announced that the U.S. was upgrading diplomatic relations with Yugoslavia, that Yugoslavia could open a consulate in the U.S., that Yugoslavia had been invited to join the Southeast European Cooperative Initiative, and that Yugoslav airlines (JAT) had regained landing rights in the U.S. Regarding Kosovo, Gelbard said:

The great majority of this violence we attribute to the police, but we are tremendously disturbed and also condemn very strongly the unacceptable violence done by terrorist groups in Kosovo and particularly the UCK-the Kosovo Liberation Army. This is without any question a terrorist group. I refuse to accept any kind of excuses. Having worked for years on counterterrorist activity, I know very well that to look at a terrorist group, to define it, you strip away the rhetoric and just look at actions. And the actions of this group speak for themselves.35

Gelbard later retracted the allegation about the KLA, and the group was never placed on the U.S. government's list of terrorist organizations.36 At the time, however, some analysts interpreted the U.S. statement as a green light for Milosevic to begin a counter-insurgency campaign.

The 1998 Armed Conflict

The Drenica Massacres

Five days after Gelbard's comments, the Serbian government launched a major assault on the central Drenica valley, a stronghold of the KLA. On February 28 and March 1, responding to KLA ambushes of the police, special forces attacked two adjacent villages, Cirez (Qirez) and Likosane (Likoshane). On March 5, special police attacked the nearby village of Prekaz-home of Adem Jashari, a known KLA member. Jashari was killed along with his entire family, save an eleven year-old-girl.37 In total, eighty-three people lost their lives in the three attacks, including at least twenty-four women and children.38

Although the KLA engaged in combat during these attacks, Serbian special forces fired indiscriminately at women, children, and other noncombatants. Helicopters and military vehicles sprayed village rooftops with gunfire before police forces entered the village on foot, firing into private homes. A pregnant woman, Rukia Nebihi, was shot in the face, and four brothers from one family were killed, apparently while in police custody. Ten members of the Ahmeti family were summarily executed by the police.

The Serbian police denied any wrongdoing in the attacks and claimed they were pursuing "terrorists" who had attacked the police. A police spokesman denied the "lies and inventions" about indiscriminate attacks and excessive force carried by some local and foreign media and said "the police has never resorted to such methods and never will."39

These events in Drenica were a watershed in the Kosovo crisis. If the government's aim was to crush the nascent insurgency, it had the opposite effect: the brutal and indiscriminate attacks radicalized the ethnic Albanian population and swelled the ranks of the KLA. Many ethnic Albanians who had been committed to the nonviolent politics of Rugova or the peaceful student movement decided to join the KLA, in part because they viewed the armed insurgency as the only means of protection. The various armed families and regional KLA groups active in Kosovo up to that point began to merge as a more organized popular resistance took shape.

The Drenica massacres also marked the beginning of the Kosovo conflict in the terms of the laws of war. It was only after February 28, 1999, that the fighting clearly went beyond mere internal disturbances to become an internal armed conflict, a threshold which once passed obliges both government forces and armed insurgencies to respect basic protections of international humanitarian law-the rules of war. In particular, Article 3 common to the four Geneva Conventions of 1949, Protocol II to those conventions, and the customary rules of war would henceforth apply to the conduct of hostilities in Kosovo.

The significance of the Kosovo conflict being classified an "armed conflict" went beyond a mere invocation of standards. Once open conflict broke out, the jurisdiction of the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia over Kosovo began. Mandated to prosecute crimes against humanity and violations of the laws or customs of war in the territory of the former Yugoslavia, the tribunal, on March 10, stated that its jurisdiction "covers the recent violence in Kosovo," although tribunal investigators did not visit the province until four months later.40

As the conflict grew, so too did the insurgency. Money from the diaspora community that was previously given to the LDK was increasingly diverted to the fund of the KLA, known as Homeland Calling. Increasingly, Albanian men from Western Europe and later the U.S. joined the insurgency.

Role of the International Community

The killings in Drenica drew the attention of the international community, despite Yugoslav government pleadings that the conflict was an internal affair. The international community criticized the state's excessive violence in Drenica but took minimal steps beyond verbal condemnations. On March 2, State Department spokesman James Rubin said that the U.S. was "appalled by the recent violent incidents" and threatened that "the outer wall" of sanctions would stay in place until there was improvement in Kosovo. He also called on Kosovar Albanian leaders to "condemn terrorist action by the so-called Kosovo Liberation Army."41

Over the next seven months, notwithstanding continued state violence, threats of sanctions and other punitive measures were weakly, if ever, enforced. Concessions were granted after the slightest progress, after which Serbian commanders, under the command of Milosevic, would often order renewed violence.

On March 9, the Contact Group met in London and gave the FRY government ten days to meet a series of requirements, including: to withdraw the special police from Kosovo and cease actions against the civilian population by the security forces; to allow access for the ICRC and other humanitarian organizations as well as by representatives of the Contact Group and other diplomatic representatives; and to begin a process of dialogue with the Kosovar Albanian leadership.42 The Contact Group proclaimed that, if President Milosevic took those steps, it would reconsider the four punitive measures that it had adopted.43 If he failed to comply, the group would move to further international measures, including an asset freeze on FRY and Serbian government funds abroad.

In a parallel move, the U.S. State Department announced on March 13 that it was providing $1.075 million to support the investigations of the war crimes tribunal in Kosovo.44

Allowing ten days to slip to sixteen, the Contact Group met again on March 25. In the days prior to the March 25 meeting, the Milosevic government briefly reduced the police attacks in Kosovo and agreed to implement the education agreement, a long-standing demand of the international community and one of many needed confidence-building measures cited in the March 9 Contact Group statement. Though not enough to bring the Contact Group to lift its previously adopted measures, the FRY gestures kept the group from imposing new measures and bought Milosevic some time. The Contact Group agreed to meet again in four weeks to reassess the situation.45

On March 31, the Security Council passed resolution 1160 which condemned violence on all sides, called for a negotiated settlement, and imposed an arms embargo on Yugoslavia. In April 1998, Milosevic organized a popular referendum on whether there should be international mediation in the Kosovo conflict. The vote for no international involvement was overwhelming.

The Contact Group meeting of April 29 set in motion a new round of maneuvering between the international community and the FRY government. Finding that the conditions set on March 9 remained unfulfilled, the Contact Group decided to take steps to impose the asset freeze. The freeze, first threatened if Belgrade did not meet Contact Group conditions by March 19, was finally endorsed by the Contact Group a month and a half later. It was not implemented by the European Union until late June-plenty of time for the Yugoslav authorities to shelter any funds that might otherwise have been affected. The Contact Group also promised to pursue an investment ban if Milosevic did not meet new conditions by May 9.46 These new conditions were watered down from the March 9 ultimata, substituting a general call for "cessation of repression" for the earlier "withdraw the special police units," and dropping the demand for access for the ICRC and humanitarian organizations altogether. As Milosevic raised the level of violence, the international community lowered the bar he needed to clear to regain international acceptance.

During the second quarter of 1998, the KLA, called a "liberation movement" by most ethnic Albanians and a "terrorist organization" by the Yugoslav government, took loose control of an estimated 40 percent of Kosovo's territory, including the Drenica region and the area around Malisevo. KLA spokesmen, increasingly in the public eye, spoke of "liberating Pristina" and eventually Kosovo. Serb civilians in areas under KLA control were harassed or terrorized into leaving, by assaults, kidnaping, and sporadic killing.

In late April and early May, the KLA took control of the villages northeast of the main road running between Decani (Decane) and Djakovica, with a headquarters in Glodjane. Serbs were forced out of these villages and fled to Decani town, where inter-ethnic tensions increased sharply. The KLA appeared to be attempting to establish a corridor between Albania and Drenica.

In retrospect, some analysts believe that the Serbian police and Yugoslav army purposefully allowed the KLA to expand. Aware that the lightly armed and poorly organized insurgency could not hold territory, the security forces allowed the rebels to spread themselves too thin across a large swath of territory. Government forces did not attack, but positioned themselves, such as on the Suka Crmljanska hill near Lake Radonjic. Other analysts, however, believe that the rapid growth of the KLA caught the Serbian government by surprise.

After five days of intense shuttle diplomacy by U.S. Special Envoy Richard Holbrooke, Milosevic and Rugova agreed to meet on May 15 in Belgrade, together with four other Kosovar Albanian representatives.47 In a major concession to Milosevic, the meeting took place without the presence of foreign mediators, a long-time condition set by both the international community and the Kosovar Albanians. Milosevic agreed to continue negotiations and named a team to be headed by Ratko Markovic, Deputy Prime Minister of Serbia. After the meeting, Milosevic's office issued the following statement: