<<previous | index | next>>

Coalition Conduct in the Ground War

The Coalition took many precautions to spare civilians from the effects of the ground war, including vetting cluster munition strikes and giving guidance to troops involved in direct combat. The use by U.S. and U.K. ground forces of cluster munitions, especially in or near populated areas, however, was one of the major causes of civilian casualties in the war. Moreover, in some instances of direct combat, problems with training on as well as dissemination and clarity of the rules of engagement may have contributed to loss of civilian life.

Ground-Launched Cluster Munitions

The U.S. and U.K. use of ground-launched cluster munitions represented one of the major threats to civilians during the war. Unlike Coalition air forces, American and British ground forces used cluster munitions extensively in populated areas. Human Rights Watch found evidence of ground-launched submunitions (known as grenades) in residential neighborhoods across the country, including in Basra, al-Hilla, Karbala’, al-Najaf, and Baghdad. A military list of duds reported after the war shows that the use of these weapons was widespread along the battle route to Baghdad, including in and around other populated areas.237 While these strikes were directed at Iraqi military targets, the weapons’ inaccuracy, broad footprints, and large numbers of submunitions caused hundreds of civilian casualties.

Use of Cluster Munitions

Coalition use of ground-launched cluster munitions far outstripped the use of air-dropped models. CENTCOM reported in October that it used a total of 10,782 cluster munitions,238 which could contain between 1.7 and 2 million submunitions.239

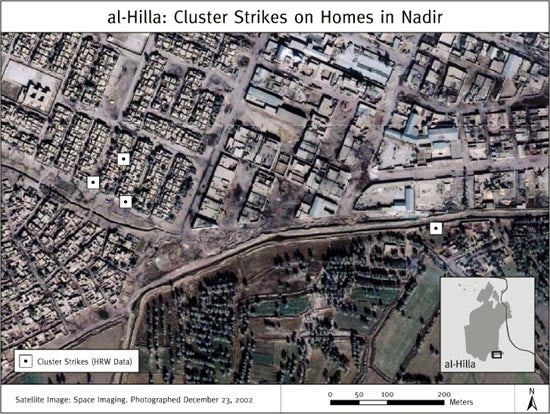

An Iraqi woman holds a U.S. submunition dud she found on her home in Nadir, a neighborhood of al-Hilla. The explosive had come out of the ground-launched DPICM shell so she was in no danger. Thirty-eight civilians were killed and 156 were injured in Nadir during and after the U.S. attack on March 31, 2003. © 2003 Marc Garlasco / Human Rights Watch

Although it did not break them down by type, field research and U.S. Air Force numbers suggest that the vast majority were ground-launched. Human Rights Watch found evidence of at least four types of artillery-, rocket-, and missile-delivered submunitions. The Third Infantry and 101st Airborne divisions and the 214th Field Artillery Brigade reported using 1,014 MLRS rockets, 330 Army Tactical Missile System (ATACMS) missiles, and 121 artillery shells with Sense and Destroy Armor Munitions (SADARMs), which carry at least 928,000 submunitions of varying types.240 They also used 17,423 artillery rounds, an unknown number of which carried submunitions.241 The United Kingdom, more forthcoming about its weapons choice, reported it used 2,100 ground-launched cluster munitions.242 Its L20A1 artillery projectile contains forty-nine grenades, for a total of 102,900 submunitions, more than ten times the number of cluster bomblets the Royal Air Force dropped.

While information from CENTCOM and individual ground units has trickled in, the U.S. Army and Marine Corps have not released final numbers of cluster munitions they launched. Human Rights Watch called for more transparency on cluster use in an April 29 press release.243 Five months after the war, a senior CENTCOM official said the information was still unavailable. “The process is continuing. Units on the battlefield are still on the battlefield, and I can’t swear to the precision of record keeping. The guidance from CENTCOM and the Army and Marine Corps is to recreate to the best degree possible where munitions were used so we can provide back to the U.N. . . . a best guess of where they are [to facilitate clearance of duds],” the official said.244 CENTCOM’s release in October of a figure for total cluster munitions implies it has completed its counting process. Nevertheless, a complete breakdown by service branch and type of munition has yet to be made public.

U.S. and U.K. forces used these weapons to respond to or prevent incoming fire from Iraqi forces. U.S. ground forces deployed cluster munitions primarily as a counter-battery tool, i.e. to destroy enemy mortars and artillery and to kill the troops operating them. While six rounds of high explosive artillery, a unitary weapon that sends fragments fifty yards (forty-six meters) in every direction, was the “normal response” to incoming mortar fire, MLRS cluster munitions were used for longer-range targets.245 Ground-launched clusters were also used for suppression of enemy air defense (SEAD) missions.246 These missions sought to clear a safe path for Apache helicopters by attacking “man portable air defense,” such as an Iraqi soldier with a shoulder-launched missile. They blanketed the path of a helicopter with submunitions, targeting places where such defense might have existed even if there was no observation to confirm it.247 British ground forces used cluster munitions for their anti-armor and area effects. “If there’s a twenty-tank convoy, if you use a precision-guided munition, you get one at a time. If you use a cluster munition, you get twenty in one hit,” said Colonel Baldwin. For non-armored targets, the British fired high explosive artillery rounds.248

The majority of the U.S. submunitions used were Dual-Purpose Improved Conventional Munitions (DPICMs). Smaller than the air-dropped BLU-97, each DPICM grenade is 2.25 inches (5.5 centimeters) tall and 1.5 inch (3.5 centimeter) in diameter. Sometimes likened to a battery, it is a cylinder, usually gray, that has one hollow end and, at the other, a white ribbon that arms and stabilizes it during flight. It consists of a scored, steel fragmentation case with an armor-piercing shaped charge inside. The DPICM can be launched by artillery or rocket. A 155mm artillery projectile contains either eighty-eight or seventy-two M42 and M46 DPICMs, depending on the model.249 The MLRS has twelve rockets, each with 644 M77 DPICMs. In Iraq, the standard volley of six rockets would release 3,864 submunitions over an area with a .6-mile (one-kilometer) radius.250 Both delivery systems leave shockingly large quantities of duds; the artillery projectiles have a dud rate of 14 percent, the MLRS a dud rate of 16 percent, about triple the Air Force estimate for BLU-97 bomblets.251

U.S. ground forces also used missile- and helicopter-launched submunitions. The ATACMS consists of a thirteen-foot-long (four-meter-long) missile fired from a modified MLRS. It contains 950 or 300 M74 softball-sized submunitions, each of which dispenses 195 fragments that target thin-skinned vehicles and personnel.252 The reported dud rate is 2 percent.253 The Hydra M261 rocket is launched from Apache or Cobra helicopters and contains nine submunitions with clover-leafed parachutes.254 These M73 grenades have a reported 4 percent dud rate.255

For the first time in combat, the United States used the SADARM, a guided artillery-launched submunition.256 Each 155mm shell contains two submunitions that use wave and infrared sensors to detect armored vehicles. If they find a target, they fire a penetrating slug that pierces armor. If they do not, they are designed to self-destruct.257 Although further research will need be done to determine the weapon’s humanitarian effects, a Third Infantry Division presentation on lessons learned in Iraq described the SADARM as a “winner,” saying it was accurate and “very effective” against tanks and other armor.258

British ground forces used the L20A1 artillery projectile. It contains forty-nine M85 submunitions, which the United Kingdom used for the first time in combat in Iraq. These Israeli-designed grenades resemble the DPICM in shape, color, and purpose. They also have a self-destruct mechanism, however, that is designed to reduce the dud rate to 2 percent.259

Civilian Harm

Ground-launched cluster strikes caused hundreds of civilian casualties across Iraq. Human Rights Watch documented cases in most of the major cities, including al-Hilla, al-Najaf, Karbala’, Baghdad, and Basra. Doctors at local hospitals provided statistics that supported individual testimony of deaths and injuries. The majority of these casualties resulted from the heavy use of cluster munitions in populated areas where soldiers and civilians commingled. The targeting of residential neighborhoods with these area effect weapons represented one of the leading causes of civilian casualties in the war.

Al-Hilla endured the most suffering from the use of ground-launched cluster munitions. Dr. Sa`ad al-Falluji, director and chief surgeon of al-Hilla General Teaching Hospital, said 90 percent of the injuries his hospital treated during the war were from submunitions.260 In the neighborhood of Nadir, a slum on the south side of the city, every household Human Rights Watch visited suffered personal injury or property damage during a March 31 cluster attack. On the day of the strike, the hospital treated 109 injured civilians from that neighborhood, including thirty children.261 According to local elders, the attack killed thirty-eight civilians and injured 156.262 During a visit on May 19, Human Rights Watch found dozens of mud brick homes with pockmarked walls and holes in the roof from shrapnel. Male residents pointed to wounds on their legs and pulled up their shirts to reveal chest and abdominal wounds. In the house of Falaya Fadl Nasir, for example, the strike injured three people, his two children, Mahdi, 18, and Marwa, 10, as well as Imam Hassan `Abdullah. One grenade pierced the roof of his home, causing a fire inside.263 Hamid Turki Hamid, 36, a dresser in the hospital, said his son and a friend were in the street when the attack began. After bringing in his son, he returned to gather his neighbor’s child. “That’s when the bomb exploded, when I was injured,” Hamid said.264

Map 14

Download PDF ( Kb)

Cluster munitions caused civilian casualties in other neighborhoods in and around al-Hilla. On March 31 at about 2:00 p.m., the U.S. Army launched DPICMs on al-Maimira, a village of about 500 people south of al-Hilla. The strike killed three civilians—Amir Ahmad, 9, Jawad Ruman, 27, and Khalid `Abbas, 32—and injured thirty-eight. A villager said there was no battle in the area and speculated that the strike was aimed at guns on the main road and across the river or civilian lorries mistaken for a military convoy.265 During an attack on al-Mahawil at 1:00 p.m. around April 3, cluster grenades killed four civilians and injured five, most of whom had to have limbs amputated. One woman, who was nine months pregnant, had an amputation and an injury to her womb; the baby had shrapnel in it but survived.266

Dr. Sa`ad al-Falluji inspects the X-ray of a patient with shrapnel still lodged in his leg in al-Maimira, outside al-Hilla. Three civilians were killed and thirty-eight injured during a U.S. ground-launched cluster strike on the village. © 2003 Marc Garlasco / Human Rights Watch

The harm to civilians caused by ground-launched submunitions in al-Hilla exemplified a pattern seen around the country. In al-Najaf, cluster grenades killed about thirty-six civilians on the night of March 28 alone.267 “The day of the bombing was a horrible day. There were not enough places to keep the dead people. Many of the dead people were in the lobbies of the hospital. . . . Later families came and took them. The government buried unknown people in the cemeteries,” said Dr. Safa’ al-`Umaidi, director of al-Najaf Teaching Hospital.268 The nearby al-Najaf General Hospital treated fewer patients during the war, but the director said most of the injuries he saw came from cluster munitions.269 A cluster strike that landed in Hay al-Karama at 1:00 a.m. on March 27 caused many civilian casualties. Hatim Jawad, a 52-year-old merchant, for example, suffered shrapnel wounds as well as severe damage to his home.270 Another man approached Human Rights Watch crying and clutching a piece of bone he said was part of his late sister’s skull.271

The villages around al-Najaf also suffered casualties from ground cluster strikes. At sunset on March 28, cluster grenades landed on the farm of Jassim `Abdul-Ridha, 31, in al-Hifa, southeast of al-Najaf. Two months later, his 10-year-old son, Nussair, who had been tending sheep during the strike, was still in the hospital recovering from skin grafts, fractures, and bone loss in his ankle. His other son, Muhammad Jassim, 7, had been injured at the same time but had returned home. Two neighbor children were hurt in this strike: Jassim Muhammad, 6, suffered paralysis and received additional shrapnel wounds in his abdomen and upper leg; his brother Ja`far Muhammad, 3, suffered head injuries that led to apparent brain damage.272 At a different farm west of al-Najaf, three brothers were sitting in their garden when a strike occurred around March 22.273 Salim Hashim, 26, lost his left hand and suffered injuries to his chest, leg, right thigh, shoulder, and face; he remained in the hospital on May 24. Hamid Hashim, 23, received shrapnel injuries to his head and eye, and Hani Hashim, 20, was injured in his hand.274

U.S. ground forces also made extensive use of cluster munitions in and around Baghdad. At 2:00 a.m. on the night of April 4 to 5, DPICMs rained down on an apartment complex next to a Palestinian refugee camp in northeast Baghdad.275 The submunitions killed at least one civilian, Radwan Muhammad, and injured about eighteen others.276 “When they started bombing the area, I was standing with four persons. All were injured. The explosion hit my eyes and I couldn’t see because of the big light,” said Ahmad Yahir Ahmad Salama al-Hadidi, 45.277 He still has shrapnel in his body and has difficulty breathing because of burn damage to his lungs.278 Residents speculated that the strike targeted Syrian fedayeen outside their homes or an anti-aircraft position at a nearby intersection. This strike was one of many in the capital area.279 A list of submunition duds from the U.S. military, which provides an indication of where strikes occurred, includes 166 sites within a twenty-kilometer (12.4-mile) radius of Baghdad.280

U.K. forces caused dozens of civilian casualties when they used ground-launched cluster munitions in and around Basra. A trio of neighborhoods in the southern part of the city was particularly hard hit. At noon on March 23, a cluster strike hit Hay al-Muhandissin al-Kubra (the engineers’ district) while `Abbas Kadhim, 13, was throwing out the garbage. He had acute injuries to his bowel and liver, and a fragment that could not be removed lodged near his heart. On May 4, he was still in Basra’s al-Jumhuriyya Hospital.281 Three hours later, submunitions blanketed the neighborhood of al-Mishraq al-Jadid about two-and-a-half kilometers (one-and-a-half miles) northeast. Iyad Jassim Ibrahim, a 26-year-old carpenter, was sleeping in the front room of his home when shrapnel injuries caused him to lose consciousness. He later died in surgery. Ten relatives who were sleeping elsewhere in the house suffered shrapnel injuries.282 Across the street, the cluster strike injured three children. Ahmad `Aidan Malih Hoshon, 12, and his sister Fatima, 4, both had serious abdominal injuries; their cousin Muhammad, 13, had injuries to his feet.283 Hay al-Zaitun, just east of al-Mishraq al-Jadid, suffered casualties from cluster munitions that landed there on the evening of March 25. Jamal Kamil Sabir, a 25-year-old laborer, lost his leg to a submunition blast while crossing a bridge near his home with his family. He spent eleven days in the hospital. His nephew, Jabal Kamil, 22, took shrapnel in his knee. Jamal’s pregnant wife, Zainab Nasir `Abbas, still had shrapnel in her left leg in May because doctors were afraid to remove it during her pregnancy.284 A neighbor, Zaitun Zaki Abu Iyad, 40, was killed when cluster grenades landed on her home.285

Jamal Kamil Sabir lost his right leg during a U.K. cluster munition strike on his home in Hay al-Zaitun in Basra on March 25, 2003. © 2003 Reuben E. Brigety, II / Human Rights Watch

Human Rights Watch also found evidence of ground-launched submunitions in other areas of Basra. In al-Tannuma neighborhood, on the eastern bank of Shatt al-`Arab, U.K. artillery targeted Iraqi tanks hidden in a date grove in the middle of civilian homes. The cluster grenades blanketed a much larger area. When the strike occurred on March 30 at 4:45 a.m., nine members of Tha’ir Zaidan’s family were injured. Shrapnel lodged in the head of his young son, Hassan.286 On the opposite side of the city, cluster munitions targeted Iraqi troops in al-Hadi neighborhood. The strike killed Sa`ad Sha`ban, 40, and Bassam Ghali, 35.287

It appears that most if not all of the strikes described above were directed at legitimate military targets. Human Rights Watch saw tanks and artillery positions located in neighborhoods, and witnesses described the presence of Iraqi forces. Nevertheless, the United States and United Kingdom made poor weapons choices when they used cluster munitions in populated areas. Such strikes almost always caused civilian casualties, in the case of al-Hilla numbering more than one hundred, because the weapons blanketed areas occupied by soldier and civilian alike with deadly submunitions that could not distinguish between the two.

Targeting and Technology

Both the U.S. and U.K. militaries took precautions to limit civilian casualties by establishing a process for vetting ground-launched cluster strikes. As shown above, however, such attacks were one of the major causes of civilian casualties during the war. The precautions failed for two reasons. First, the technology available to Coalition ground forces, in terms of range, accuracy, and reliability of cluster munitions, fell far behind that of the U.S. Air Force. Second, despite the vetting process, ground troops consistently used these area effect weapons in residential neighborhoods, virtually guaranteeing loss of civilian life. Coalition militaries should reevaluate and reform their use of ground-delivered cluster munitions before employing them in any future conflict.

U.S. forces screened ground cluster strikes through a computer and human vetting system. The Third Infantry Division’s artillery batteries were programmed with a no-strike list of 12,700 sites that could not be fired upon without manual override. The list included civilian buildings such as schools, mosques, hospitals, and historic sites.288

Map 9

Officers of the Second Brigade said they strove to keep strikes at least 500 meters (547 yards) away from such targets although sometimes they cut the buffer zone to 300 meters (328 yards).289 In general, they also required visual confirmation of a target before firing, but in the case of counter-battery fire, they considered radar acquisition sufficient.290 The latter detects incoming fire and determines its location, but it cannot determine if civilians occupy an area.

The Third Infantry Division established another layer of review by sending lawyers to the field to review proposed strikes, a relatively recent addition to the vetting process.291 “Ten years ago, JAGs [judge advocate general attorneys] weren’t running around [the battlefield],” said Captain Chet Gregg, Second Brigade’s legal advisor.292 The division assigned sixteen lawyers to divisional headquarters and each brigade.293 Lead lawyer Colonel Cayce, who served at the tactical headquarters, reviewed 512 missions, and brigade JAGs approved additional attacks, which were often counter-battery strikes. Although less controversial strikes, such as those on forces in the desert, were not reviewed, Cayce said, “I would feel pretty confident a lawyer was involved in strikes in populated areas.”294 Commanders had the final say, but lawyers provided advice about whether a strike was legal under IHL. Cayce said his commander never overruled his advice not to attack and sometimes rejected targets he said were legal.295

While the review process involved a careful weighing of military necessity and potential harm to civilians, limited information and the subjectivity of such an analysis meant it was “not a scientific formula.”296 The first challenge was to determine the risk to their forces. “The hard part is how many casualties we will take. It’s a gut level, fly by the seat of your pants. There’s no standard that says one U.S. life equals X civilian lives,” Cayce said.297 Then lawyers had to evaluate the threat to civilians. In the case of counter-battery fire, they had to make the judgment without knowing if civilians were present in the target area at the time of the strike; they relied instead on pre-war population figures. Cayce acknowledged the danger of cluster strikes on populated areas and said that he tried to limit them to nighttime. “I was hoping kids were hunkered down, hoping with artillery fire they were not out watching,” he said.298

British artillery units had a similar vetting process although it gave observers more responsibility than lawyers. Its no-strike list included schools, mosques, and hospitals. “We couldn’t fire on [such a site] irrespective of who was in it. Even if you called for fire, it couldn’t happen. They were no-fire zones,” said Colonel Baldwin.299 Unlike the U.S. forces, the British required forward observation even in the case of counter-battery fire. Either a human or the video of an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV), or drone, had to confirm visually that no civilians were present. “At no time did we fire where we couldn’t see,” Baldwin said.300 Asked about the civilian injuries in al-Tannuma, he said, “I cannot completely rule out the fact somebody went against the ROE, but I’d be surprised if they did. For every single artillery strike, we asked an observer if he saw civilians.”301

While the British required observers, they did not have lawyers in the field. Military lawyers signed off on the rules of engagement before the conflict, but the interpretation was done at a divisional level, if there was time, or below that, if the conflict was happening too fast. “If [the battle was] so fast and furious, interpretation went down to the forward observer. We argue they are the best judge of if we should fire or not,” Colonel Baldwin said.302

The value of these vetting processes for cluster strikes was limited by the weapons and technology available to ground troops. Officers of the Third Infantry Division complained that if they needed long-range rocket artillery, the MLRS with submunitions was the only option they had. Therefore, they said, they often had to use cluster munitions for counter-battery fire when a unitary warhead would have sufficed.303 “We need to have the capability to hit a target [with something] more like a regular high explosive shell. . . . We are already testing longer-range cannon with a regular shell. It would solve a lot of problems,” Colonel Cayce said.304 A high explosive shell impacts an area with a fifty-yard (forty-six-meter) radius rather than the .6-mile (one-kilometer) radius of an MLRS volley.305 The U.S. Marines, however, did not have the MLRS, relying instead on artillery, air support, and possibly help from Army ATACMSs.306 These alternatives raise questions about the military necessity of the Army’s MLRS cluster strikes.

Ground-launched cluster munitions were also less accurate than the newer, air-dropped models. “In defense of the ground guys, I have to say we have not come the distance in ability to be precise with [ground-launched] cluster munitions to the degree we have with the air. . . . The Army is working on coming the extra mile on precision-guided munitions,” a senior CENTCOM official said.307 Colonel Cayce also called for more accurate long-range artillery. He said the Army was developing a guided skeet, like that in the CBU-105, for the MLRS.308 The SADARM is guided, but it is artillery-launched and does not have a range equal to the MLRS. In the Third Infantry Division’s after action report, it recommended the development of “an MLRS suite of munitions that allow for greater employment on the battlefield,” including in populated areas.309

Unlike the Americans, the British ground forces used exclusively new cluster technology in Iraq—the L20A1 artillery munition. While this weapon’s submunitions have a lower dud rate than the U.S. versions, it remains an area effect weapon that kills civilians when used in a populated area. The new technology only lulled the British into taking less care when using it.310

The precautions to reduce civilian casualties did not prevent widespread use of cluster munitions in populated areas. The no-strike lists included certain civilian structures but not residential neighborhoods. Forward observers either ignored or failed to see civilians in populated areas. U.S. military lawyers did not challenge the proposed strikes although they raise serious concerns under IHL’s proportionality test.

Training may also have been inadequate. “The training paradigm for artillery is still evolving,” a senior CENTCOM official said. “The Army looks for mass of fire as opposed to precision because they don’t know what’s out there beyond the horizon. As they press forward, they want to make sure they are reducing the threat to their forces, suppressing what’s beyond the next horizon.”311 An Army field manual acknowledges the dangerous side effects of cluster munitions and discusses ways to limit the collateral damage of strikes in urban areas, but it does not prohibit them or consider them indiscriminate.312

The Coalition may have fired on legitimate military targets, especially when responding to incoming Iraqi fire, but the use of cluster munitions in populated areas almost always leads to civilian casualties. For that weapon, neighborhoods still occupied by their residents should be put on a no-strike list, to be overridden only with excellent information and careful consideration.

Conclusion and Recommendations

As described in more depth in the previous chapter, cluster munition strikes raise concerns under international humanitarian law. They must be evaluated on a case-by-case basis under the proportionality test, which balances military advantage and civilian impact. Strikes in or near populated areas are usually problematic because when combatants and civilians commingle, civilian casualties are difficult to avoid. Cluster munition strikes also have the potential to be indiscriminate because the weapons cannot be precisely targeted. Cluster munitions are area weapons, useful in part for attacking dispersed or moving targets. They cannot, however, be directed at specific soldiers or tanks, a limitation that is particularly troublesome in populated areas.

In choosing weapons, parties to an armed conflict must minimize civilian harm. They must “take all feasible precautions in the choice of means and methods of attack with a view to avoiding, and in any event to minimizing, incidental loss of civilian life, injury to civilians and damage to civilian objects.”313 The weapons should be used sparingly, if at all, when it is foreseeable that they will cause at least incidental harm to civilians. The availability of alternative weapons must be also considered.

The use of cluster munitions in the ground war raises serious questions under these provisions of IHL. The weapons themselves have inherent flaws that make strikes in populated areas prone to being indiscriminate. Furthermore, while the Coalition took precautions by establishing vetting processes for individual strikes, the results show them to be inadequate. Despite the care taken, ground-launched cluster strikes caused hundreds of civilian casualties. As will be discussed below, the duds they left behind increased the number of deaths and injuries after the conflict.

Human Rights Watch has previously called for a suspension of cluster munition use until the weapon’s humanitarian effects have been fully addressed.314 If cluster munitions are used, Human Rights Watch recommends:

- Armed forces cease using ground-launched cluster munitions in or near populated areas.

- Coalition forces develop a new vetting process that successfully reduces the harm to civilians caused by cluster munitions.

- The U.S. military identify, and if necessary develop, a long-range alternative to the MLRS with submunitions.

- U.S. ground forces keep better records of the number, location, and type of cluster munitions used. Such records are essential for clearance of duds and also facilitate analysis of and accountability for targeting decisions.

Antipersonnel Landmines

The United States refused to rule out use of antipersonnel mines in Iraq, saying on one occasion that American forces might use air-dropped mines to prevent access to suspected chemical weapons sites.315 By February 2003, the United States reportedly had stockpiled ninety thousand antipersonnel mines in Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia.316 There have been no confirmed reports, however, of antipersonnel mine use by the United States or other Coalition forces during the conflict. The head of the Coalition Provisional Authority stated, “We have constructed no minefields, set no ‘booby traps’ anywhere in Iraq.”317 U.S. forces used command-detonated Claymore directional fragmentation mines, which are permitted under the 1997 Mine Ban Treaty.318 Like Iraq, the United States is not a party to the Mine Ban Treaty, but most of its Coalition partners, including the United Kingdom and Australia, are. Human Rights Watch believes any use of antipersonnel mines violates customary international law.

Rules of Engagement

Although the United States took precautions to protect civilians by issuing rules of engagement, problems with training on, dissemination of, and clarity of these rules may have, in some instances, contributed to loss of civilian life.

The U.S. military provided guidelines for its troops by distributing laminated rules of engagement cards to all its soldiers and Marines. These ROE, issued by the CENTCOM’s Combined Forces Land Component Commander (CFLCC), tell troops to obey the laws of war and explain their legal obligations during combat. The first provision states, “Positive identification (PID) is required prior to engagement. PID is a reasonable certainty that the proposed target is a legitimate military target. If no PID, contact your next higher commander for decision.” Other paragraphs set out additional protections for civilians. For example:

Do not target or strike any of the following except in self-defense to protect yourself, your unit, friendly forces, and designated persons or property under your control:

Civilians Hospitals, mosques, national monuments, and any other historical and cultural sites.

Do not fire into civilian populated areas or buildings unless the enemy is using them for military purposes or if necessary for your self-defense. Minimize collateral damage.319

The ROE card, reprinted in full as an appendix to this report, is consistent with international humanitarian law. The armed forces develop general ROE for each armed conflict. Individual operations within each conflict may also have their own specific set of rules of engagement, tailored to the particular circumstances of the battle.

Soldiers and Marines interviewed by Human Rights Watch said they tried to abide by these rules. Colonel Perkins of the Third Infantry Division said when faced with fedayeen in civilian vehicles, his troops would use a spotter to let them know which cars were safe to target. “We tried to delineate between civilian and military targets. . . . On the fifth and on the seventh [of April] when we attacked [Baghdad] the majority of what you can hear is, ‘OK, can you see the white vehicle? He just shot at our guys. He’s an enemy. The blue guy behind him is friendly, don’t engage him,’” Perkins said.320

Training on the application of rules of engagement, however, may have been insufficient. Elements of the Third Infantry Division practiced urban combat tactics “all the time” in Kuwait, but the training focused on teaching soldiers how to clear a room in close combat quarters, not how to engage an unconventional enemy whose forces may wear civilian clothes.321 A military conference about lessons learned from the war emphasized the need better to prepare troops for dealing with ROE. Its list of lessons includes “Rules of Engagement (ROE) vignette training is critical in ensuring soldiers in contemporary operational environment (COE) adhere to laws of land warfare.”322

Post-conflict analysis by the Third Infantry Division indicates problems with dissemination of the rules of engagement. According to the division’s after action report, the final ROE, which included “new guidance on high collateral-damage targets,” arrived after its troops had moved to Kuwait. “Late receipt of ROE caused confusion on a number of issues that were not clearly written. These matters were not resolved until hostilities began, meaning we could not train soldiers on the provision,” the report said.323

During the war, especially in the battles of Baghdad and al-Nasiriyya, contradictions in, lack of consistency in, and/or misapplication of rules of engagement may have led to civilian casualties. In particular, verbal ROE apparently differed from the official written ROE, most notably with respect to the requirement for positive identification prior to engagement.

From April 5 to 7, the Third Infantry Division pushed its way into Baghdad in an advance known as Thunder Run. Contradictions in verbal and written rules of engagement may have led to civilian casualties. Junior U.S. soldiers who participated in Thunder Run said that on April 7 the verbal ROE from their immediate superiors were to “assume that all targets were hostile” rather than to obtain positive identification. They said that the verbal ROE were changed on April 9 to allow them to engage targets only when they were fired upon.

Colonel Perkins, who led Thunder Run, said that ROE guidance for his troops was: “Don’t take anything for granted; assume that people have the capability to kill you, but don’t assume that everyone is hostile.” He said hostile intent would be demonstrated if (1) a target fired at a soldier, (2) a target carried a weapon, or (3) a target was driving toward U.S. forces at a high rate of speed.324 Division lawyer Colonel Cayce explained that after Iraqi combatants began to appear in civilian clothes, soldiers were warned that any civilian could be a potential combatant, but they still needed positive identification.325 Asked about the discrepancy between his version and that of the enlisted men, Perkins suggested that some soldiers may have incorrectly interpreted the guidance they were given, but that such interpretations did not accurately reflect the commander’s intent or explicit text of the ROE promulgated by CFLCC. He said civilian protections in urban combat ultimately come down to the individual soldier making the right decision. “We just have to train on it,” he said.326

In al-Nasiriyya, a change in or confusion about the rules of engagement may again have contributed to the civilian toll. A Marine officer, who came in a second wave, said al-Nasiriyya was the only place along the road to Baghdad declared “hostile.” “In the combat zone, it meant anyone there was a bad guy,” he said. Another Marine, who was among the first in al-Nasiriyya, said the ROE there were positive identification. During a daylong ambush further north near al-Shatra, however, the ROE were lifted and troops were told to “shoot anything that moves.”

Conclusion and Recommendations

Contradictions between written and verbal rules of engagement have the potential to lead to civilian casualties and violations of international humanitarian law. While U.S. rules of engagement on paper met international humanitarian law standards, in practice, soldiers and Marines reported conflicting interpretations of what they meant and how to apply them in practice, particularly in the fighting in Baghdad and al-Nasiriyya, where most civilian casualties occurred. Further investigation would be required to determine if there were violations of IHL, but there is clearly a need for better guidance and training to reduce civilian casualties in future ground wars.

Human Rights Watch recommends:

The U.S. military ensure that there is no confusion between written and verbal rules of engagement and that ROE are distributed in a timely fashion. Armed forces devote better training to application of rules of engagement, especially in urban warfare and in circumstances where the enemy may be wearing civilian clothes.

237 Humanitarian Operations Center, “Mine Data through 18 May 2003,”obtained by Human Rights Watch, Kuwait City, Kuwait, June 1, 2003 [hereinafter HOC list, May 18, 2003]. Human Rights Watch obtained this list of mines, unexploded ordnance, and submunition duds, as well as two earlier versions, from representatives of the Army Corps of Engineers at the HOC. This list includes GPS coordinates where these kinds of explosive remnants of war were found.

238 U.S. CENTCOM, executive summary of report on cluster munitions.

239 The U.S. Air Force used 1,206 reported cluster bombs and an unknown number of TLAMs and JSOWs with submunitions. Human Rights Watch found little evidence of the latter two types, which suggests the vast majority of the 10,782 cluster munitions were ground-launched. If one subtracts the 1,206 reported cluster bombs and the 1,555 reported ground-launched munitions (discussed later in this paragraph) from CENTCOM’s total, there are 8,021 unidentified cluster munitions. Given that ground forces used 17,423 artillery rounds, a large portion of those unidentified cluster munitions were probably artillery models, which contain seventy-two or eighty-eight submunitions. Taking the number of submunitions from identified cluster models and estimating the rest as if they were artillery models brings the estimated total of submunitions to between 1.7 and 2 million.

240 “Infantry Conference Summary,” Infantry Online: Timely News for the Infantry Community, October 1, 2003, http://www.benning.army.mil/OLP/InfantryOnline/issue_39/art_255.htm (retrieved October 23, 2003); Rhett A. Taylor et al., “MLRS AFATDS and Communications,” Field Artillery, July 1, 2003, p. 36. ATACMSs can carry 950 or 300 submunitions as will be discussed below. If the unidentified ATACMSs all contained 950 submunitions, the total would be 1,142,858.

241 “Infantry Conference Summary.” The M483 artillery projectile carries eighty-eight submunitions and the M864 artillery projectile carries seventy-two submunitions.

242 Ann Treneman, “Mapped: The Lethal Legacy of Cluster Bombs,” Times (London), September 11, 2003.

243 Human Rights Watch, “Iraq: Clusters Info Needed from U.S., U.K.,” Press Release, April 29, 2003.

244 Human Rights Watch telephone interview with senior CENTCOM official #2.

245 Human Rights Watch interview with Major Jim Barren, Second Brigade, Third Infantry Division, U.S. Army, Baghdad, May 23, 2003.

246 Rhett A. Taylor et al., “MLRS AFATDS and Communications.”

247 See 101st Airborne (Air Assault), “Gold Book: Targets, Techniques, and Procedures for Air Assault Operations,” March 17, 1999, annex F, http://www.fas.org/man/dod-101/army/docs/101st-goldbook/index.html (retrieved October 20, 2003).

248 Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Colonel Gil Baldwin.

249 The M483A1 contains sixty-four M42 and twenty-four M46 DPICM submunitions. The M864 contains forty-eight M42 and twenty-four M46 submunitions. For more information, see Human Rights Watch, “Cluster Munitions a Foreseeable Hazard in Iraq.”

250 The Third Infantry Division often used volleys of six rockets in Iraq. The footprints overlapped to make a larger footprint with .6-mile radius (one kilometer). Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Colonel Lyle Cayce.

251 For the dud rate of MLRS submunitions, see Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics, “Unexploded Ordnance Report,” n.d., table 2-3, p. 5, transmitted to Congress on February 29, 2000. For the dud rate of submunitions in 155mm artillery munitions, see U.S. Army Defense Ammunition Center, Technical Center for Explosives Safety, “Study of Ammunition Dud and Low Order Detonation Rates,” July 2000, p. 9. See also Human Rights Watch, “Cluster Munitions a Foreseeable Hazard in Iraq.” The U.S. Air Force estimates the dud rate of the BLU-97 to be 5 percent although deminers in Afghanistan estimated the dud rate in some areas as 22 percent. Human Rights Watch, “Fatally Flawed,” p. 25.

252 FAS Military Analysis Network, “M39 Army Tactical Missile System (Army TACMS),” May 13, 2003, http://www.fas.org/man/dod-101/sys/land/atacms.htm (retrieved October 23, 2003); ORDATA Online, “U.S. Grenade, Frag, M74,” February 4, 2002, http://maic.jmu.edu/ordata/srdetaildesc.asp?ordid=1088 (retrieved October 23, 2003).

253 Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics, “Unexploded Ordnance Report,” table 2-3, p. 5.

254 FAS Military Analysis Network, “Hydra-70 Rocket System,” May 5, 2000, http://www.fas.org/man/dod-101/sys/missile/hydra-70.htm (retrieved October 23, 2003); ORDATA Online, “U.S. Grenade, HEDP, M73,” February 4, 2002, http://maic.jmu.edu/ordata/srdetaildesc.asp?ordid=1099 (retrieved October 20, 2003).

255 Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics, “Unexploded Ordnance Report,” table 2-3, p. 5.

256 “3rd Infantry Division Commander Live Briefing from Iraq,” U.S. Department of Defense News Transcript, May 15, 2003.

257 FAS Military Analysis Network, “XM898 SADARM (Sense and Destroy Armor),” September 12, 1998, http://www.fas.org/man/dod-101/sys/land/sadarm.htm (retrieved November 7, 2003).

258 Third Infantry Division, “Fires in the Close Fight: OIF [Operation Iraqi Freedom] Lessons Learned,” n.d., http://sill-www.army.mil/Fa/Lessons_Learned/3d%20ID%20Lessons%20Learned.pdf (retrieved November 10, 2003). The Third Infantry Division also reported that “SADARM killed 48 pieces of equipment out of 121 SADARM rounds fired.” “Third Infantry Division (Mechanized) After Action Report, Operation Iraqi Freedom,” July 2003, p. 122, http://www.carson.army.mil/Moblas/NBC/3rdIDAARIraqJuly03.pdf (retrieved October 23, 2003).

259 Thomas Frank, “Officials: Hundreds of Iraqis Killed by Faulty Grenades,” Newsday, June 22, 2003 (citing the British Ministry of Defence). The hazardous dud rate, i.e. percentage of submunitions that do not explode on impact but could detonate later, is designed to be less than one percent. FAS Military Analysis Network, “M26 Multiple Launch Rocket System (MLRS),” December 23, 1999, http://www.fas.org/man/dod-101/sys/land/m26.htm (retrieved October 22, 2003).

260 Human Rights Watch interview with Dr. Sa`ad al-Falluji, director and chief surgeon, al-Hilla General Teaching Hospital, al-Hilla, May 19, 2003.

261 Of the 109 civilians, twenty-eight were women (including eleven girls) and eighty-one were male (including nineteen boys). Al-Hilla General Teaching Hospital, War-Related Casualty Records, obtained by Human Rights Watch, al-Hilla, May 20, 2003.

262 The neighborhood elders did not separate casualties that occurred during the strike from those caused by duds after the fact. Their casualty records list 144 men, 37 women, and 17 whose sex could not be determined. Shakir `Abadi `Ubaid al-Khafaji, Kadhim Karim `Ali al-Jaburi, and Hassan Jum`a Sayyid, Nadir Casualty Records, obtained by Human Rights Watch, al-Hilla, September 2003. The New York Times said thirty-three civilians died during the strike on Nadir. Tyler Hicks and John F. Burns, “Iraq Shows Casualties in Hospital,” New York Times, April 3, 2003.

263 Human Rights Watch interview with Falaya Fadl Nasir, al-Hilla, May 19, 2003.

264 Human Rights Watch interview with Hamid Turki Hamid, al-Hilla, May 19, 2003.

265 Human Rights Watch interview with Tahsin `Ali, al-Maimira, May 20, 2003.

266 Human Rights Watch interview with Khalil Nahi Athab, al-Hilla, May 20, 2003.

267 Human Rights Watch interview with Dr. Safa’ al-`Umaidi, director, al-Najaf Teaching Hospital, al-Najaf, May 24, 2003.

268 Ibid.

269 Human Rights Watch interview with Dr. `Ali al-Tufaili. Dr. al-Tufaili added, however, “The military of Saddam was in between our homes. Therefore the best way to deal with them was with clusters. . . . If not for clusters, the injured would have been more.”

270 Human Rights Watch interview with Hatim Jawad, al-Najaf, May 24, 2003.

271 Human Rights Watch interview with resident of Hay al-Karama, al-Najaf, May 24, 2003.

272 Human Rights Watch interview with Jassim `Abdul-Ridha, al-Najaf, May 24, 2003. `Abdul-Ridha, a 31-year-old farmer, is the father of Nussair and Muhammad. Medical information was provided by Dr. Muhammad Hassan al-`Ubaidi. Human Rights Watch interview with Dr. Muhammad Hassan al-`Ubaidi, doctor, al-Najaf Teaching Hospital, and assistant professor, College of Medicine, University of Kufa, al-Najaf, May 24, 2003.

273 Since this strike occurred before the main battle in al-Najaf, it could have been a SEAD mission.

274 Human Rights Watch interview with Salim Hashim, al-Najaf, May 24, 2003; Human Rights Watch interview with Dr. Muhammad Hassan al-`Ubaidi.

275 Human Rights Watch interview with Ahmad Yahir Ahmad Salama al-Hadidi, Baghdad, May 16, 2003.

276 Human Rights Watch interview with Anwar Salim al-`Awawda, director, Palestine Clinic, Baghdad, May 16, 2003.

277 Human Rights Watch interview with Ahmad Yahir Ahmad Salama al-Hadidi, Baghdad, May 16, 2003.

278 Ibid.

279 The press reported several cluster strikes in Baghdad. See, e.g., Carol Rosenberg and Matt Schofield, “In Bombed Neighborhoods, Everyone ‘Wants to Kill Americans,’” Miami Herald.com, April 15, 2003, http://www.miami.com/mld/miamiherald/5640621.htm (retrieved October 24, 2003) (cluster duds killed four civilians in al-Kharnouq neighborhood); “Iraq Says U.S. Drops Cluster Bombs on Baghdad, 14 Die,” Reuters, April 3, 2003 (cluster bombs kill fourteen civilians and wound sixty-six in al-Dura neighborhood); Thomas Frank, “Grisly Results of U.S. Cluster Bombs,” Newsday, April 15, 2003 (the Kadhimiya Hospital treated cluster victims from several Baghdad neighborhoods); Jonathan Steele, “Iraq—after the War—Bombs Silent, but the Children Still Suffer,” Guardian, April 18, 2003 (cluster bombs caused civilian casualties in the Harir city neighborhood and areas around the Kadhimiya Hospital); Rosalind Russell, “Cluster Bombs: A Hidden Enemy for Iraqi Children,” Reuters, April 18, 2003 (cluster duds injure children in al-Dura district); “Iraqi Children Facing Threat of Bomblets Left Over by U.S. Forces,” Xinhua News Agency, April 19, 2003 (cluster duds injure civilians in Rahnania in western Baghdad and in al-Dura in southeastern Baghdad).

280 See HOC list, May 18, 2003.

281 Human Rights Watch interview with `Abbas Kadhim, Basra, May 4, 2003.

282 The injured were Iyad Jassim Ibrahim, born 1970, fireman; `Imad Jassim Ibrahim, born 1971, laborer; Fu’ad Jassim Ibrahim, born 1974; Ibtisam Jassim Ibrahim, born 1975; Jihan Hassan Ahmad, born 1975, wife of Fu’ad; Lika Fadl Nasr, born 1982, wife of `Imad; Lou’ay `Imad Jassim, 4 years old, son of `Imad; Zakia Hussain Aziz, born 1946, mother of `Imad; Manal Jassim Ibrahim, born 1980, sister of `Imad; and `Athra Taha Jassim, born 1973, brother of `Imad. Human Rights Watch interview with Iyad Jassim Ibrahim, Basra, May 5, 2003.

283 Human Rights Watch interview with Ahmad `Aidan Malih Hoshon, Basra, May 5, 2003.

284 Human Rights Watch interview with Jamal Kamil Sabir, Basra, May 1, 2003.

285Human Rights Watch interview with Hassan `Ali `Abud, Basra, May 2, 2003. `Abud, a 27-year-old laborer, was the victim’s nephew. Other victims included Sabah Hamid, a 30-year-old laborer, and Hashim Hussain Muhammad, a 28-year-old laborer, who were both injured. Human Rights Watch interview with Hashim Hussain Muhammad, Basra, May 1, 2003.

286 Human Rights Watch interview with Tha’ir Zaidan, Basra, May 30, 2003.

287 Human Rights Watch interview with Hussain Sa`dan, Basra, May 30, 2003.

288 Human Rights Watch interview with Lieutenant Colonel Eric Wesley, executive officer, Second Brigade, Third Infantry Division, U.S. Army, Baghdad, May 23, 2003.

289 Ibid.

290 Ibid. Although not specifically discussing ground-launched cluster strikes, a military conference about the lessons learned in the war said the Third Infantry Division needed to expand human intelligence capability and have unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), or drones, at a divisional and brigade combat team level. “Infantry Conference Summary.”

291 Human Rights Watch interview with Colonel David Perkins.

292 Human Rights Watch interview with Captain Chet Gregg, legal advisor, Second Brigade, Third Infantry Division, U.S. Army, Baghdad, May 23, 2003.

293 Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Colonel Lyle Cayce.

294 Ibid.

295 Ibid.

296 Ibid.

297 Ibid.

298 Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Colonel Lyle Cayce.

299 Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Colonel Gil Baldwin.

300 Ibid.

301 Ibid.

302 Ibid.

303 Human Rights Watch interview with Colonel David Perkins; Human Rights Watch interview with Lieutenant Colonel Eric Wesley; Human Rights Watch interview with Major Jim Barren.

304 Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Colonel Lyle Cayce.

305 Ibid.

306 Ibid.

307 Human Rights Watch telephone interview with senior CENTCOM official #2.

308 Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Colonel Lyle Cayce.

309 “The only munitions currently available for standard MLRS rockets are the DPICM sub-munition. The ROE limited our ability to use MLRS in many cases. Fires in highly congested areas and civilian populace centers precluded the use of MLRS fires, especially within the city confines of Baghdad. Development of different types of MLRS munitions such as SADARM, brilliant antiarmor submunitions (BAT), smoke type precision munitions, and an HE [high explosive] conventional rocket similar to the Unitary missile would have greatly added to the flexibility in employing MLRS,” the report said. “Third Infantry Division (Mechanized) After Action Report, Operation Iraqi Freedom,” p. 122. See also Rhett A. Taylor et al., “MLRS AFATDS and Communications” (calling for a GPS-guided high explosive rocket).

310 Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Colonel Gil Baldwin. For further discussion, see the New Technology section of the Explosive Remnants of War chapter.

311 Human Rights Watch telephone interview with senior CENTCOM official #2.

312 The field manual says, “Commanders must still consider the precision error and large submunitions dispersion pattern when applying this method of attack due to the high probability of extensive collateral damage” and explains that MLRS rockets require “detailed planning in close operations.” It also warns of using these weapons near friendly troops because of their duds. Department of the Army, Headquarters, “Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures for Multiple Launch Rocket System (MLRS) Operations,” Field Manual 6-60, Washington, D.C., April 23, 1996. The U.S. Army does not go as far as the U.S. Air Force, however, which has said there are “[c]learly some areas where CBUs normally couldn’t be used (e.g. populated city centers).” U.S. Air Force, Bullet Background Paper on International Legal Aspects Concerning the Use of Cluster Munitions.

313 Protocol I, art. 57(2)(a)(ii).

314 Human Rights Watch, Cluster Bombs: Memorandum for Convention on Conventional Weapons (CCW) Delegates, December 16, 1999.

315 U.S. Department of Defense, “Background Briefing on Targeting,” March 5, 2003.

316 Alexander G. Higgins, “Campaigners Fear Use of Land Mines in Iraq,” Associated Press,February 6, 2003.

317 Remarks by L. Paul Bremer, III, administrator, Coalition Provisional Authority, at the Mine Action Management Course Graduation, July 31, 2003, http://cpa-iraq.org/pressconferences/mine_removal_ceremony31jul03.html (retrieved November 5, 2003).

318 U.S. CENTCOM, “CENTCOM Operation Iraqi Freedom Briefing,” March 31, 2003.

319 CFLCC, “CFLCC ROE Card,” January 31, 2003.

320 Human Rights Watch interview with Colonel David Perkins.

321 Human Rights Watch interview with Lieutenant Colonel Stephen Baer, operations officer, Third Infantry Division, U.S. Army, Baghdad, May 20, 2003; Human Rights Watch interview with Sergeant First Class Morales.

322 “Infantry Conference Summary.” The Infantry Conference took place at Fort Benning, Georgia, from September 8 to 11, 2003, and included representatives from many of the U.S. infantry units that fought in Iraq.

323 “Third Infantry Division (Mechanized) After Action Report, Operation Iraqi Freedom,” p. 286.

324 Human Rights Watch interview with Colonel David Perkins.

325 Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Colonel Lyle Cayce.

326 Human Rights Watch interview with Colonel David Perkins.

<<previous | index | next>> | December 2003 |