<<previous | index | next>>

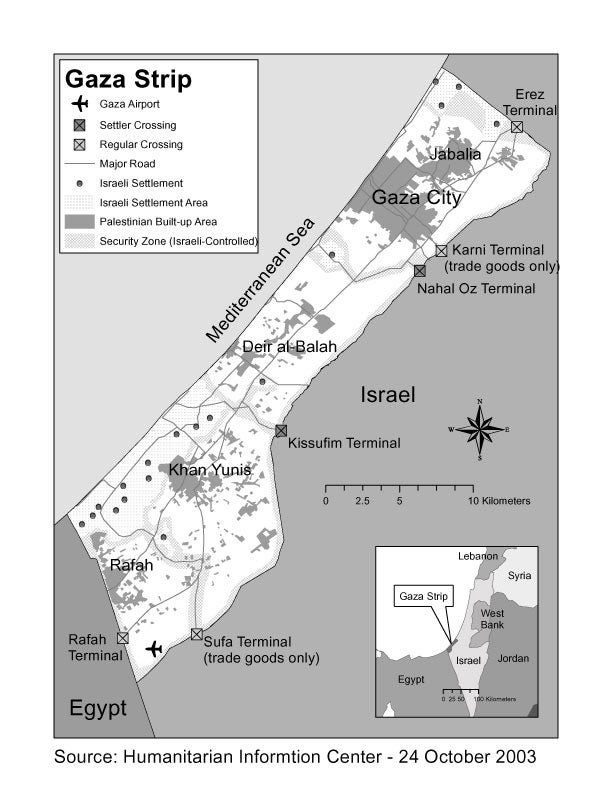

Map 1: Gaza Overview

The rest of Gaza is administered by the Palestinian National Authority (PNA), headed by Yasser Arafat, as dictated by the Oslo Accords of 1994-1995. The PNA is not a sovereign state but a self-rule administration with policing powers and is subordinate to Israel in both law and practice.35 Under the Oslo Accords, Israel retains overall security authority throughout the OPT for external defense and can take “all necessary” steps to ensure the security of both Israel and the settlements, including by taking action in areas directly administered by the PNA.36 Agreements between an Occupying Power and local authorities cannot be used to deprive civilians of their protections under international humanitarian law.37

Although the PNA cannot ratify international human rights instruments, it has signaled its desire to adhere to human rights standards. Human Rights Watch considers the PNA to be bound to international human rights standards to the extent of its powers, including obligations to prevent attacks against civilians from areas under its control and to respect the human rights of individuals in its custody. The PNA has continually failed to fulfill these obligations.38

The PNA has no military but has several security forces, from regular police to intelligence services. There are also a number of Palestinian armed groups in the Gaza Strip which are outside of the PNA’s authority and sometimes in adversarial relationships with it. Armed groups active in Gaza include the al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade, a militant offshoot of Arafat’s Fatah party, and the military wings of Hamas, Islamic Jihad, the Popular Resistance Committees, and the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine. In their fight against the occupation, all of these groups attack both civilian and military targets. Targeting civilians or carrying out indiscriminate attacks against them violates international humanitarian law, and Human Rights Watch has documented and condemned the practice by Palestinian armed groups.39

International organizations and local nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) are also involved in all aspects of Gaza life. Most important is the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) for Palestine Refugees in the Near East, whose mandate includes the provision of social services such as health care and education to Palestinian refugees both inside and outside officially recognized refugee camps. UNRWA also provides emergency relief. The agency’s role in providing services in the Gaza Strip rivals that of the PNA, as eighty percent of Gaza’s population consists of refugees. Palestinian NGOs are also very active in the fields of health care, education, and human rights.

The Uprising in Gaza: From Closure to “Disengagement”

Over the past four years, Israel has faced an armed uprising throughout the OPT, including attacks on both its military and civilians. In the Gaza Strip, the government has responded with a broad strategy of isolating the Palestinian population from Israel, strictly controlling the movement of Palestinians, while attempting to retain overall control over the territory. As explained below, the so-called “Gaza disengagement plan” is a continuation of this process.

The fighting has taken a heavy toll in the Gaza Strip, where patterns of fatalities differ considerably from the uprising as a whole. Since 2000, roughly three times as many Palestinians have been killed as Israelis in total; within Gaza, however, the ratio is closer to ten to one. According to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, 1,642 Palestinians were killed in the Gaza Strip between September 29, 2000, and August 31, 2004, including 360 children under the age of eighteen.40 As of September 24, 113 Israelis (eighty-five soldiers or armed guards and twenty-eight civilians) had been killed by Palestinians in the Gaza Strip, while fifteen civilians within Israel proper had been killed by attacks originating from the Gaza Strip.41 And while members of security forces account for approximately one-third of all Israeli deaths in the uprising,42 the eighty-two soldiers and armed guards killed in the Gaza Strip represent seventy-five percent of Israeli fatalities there.

The primary Israeli method for dealing with the uprising has been the tightening of “closure” policies that date back to the early 1990s.43 “Closure” is a broad term encompassing many different restrictions on freedom of movement, from preventing international travel to placing checkpoints on roads between neighboring villages to imposing twenty-four hour curfews that amount to mass house arrest. Closure policies in and around the Gaza Strip are far more hermetic than those in the much larger West Bank; they have also been more pervasive than overtly violent policies such as bombardment, assassination of militants and political leaders, and property destruction.

External closure is guaranteed by a fence patrolled by the IDF that surrounds the Gaza Strip, making illegal entry into Israel almost impossible. Still, two suicide attacks inside Israel during the uprising have originated from the Gaza Strip; one was carried out by a U.K. citizen, the other by a Palestinian smuggled out in a shipping container. As Palestinian militants continue their attacks, the Israeli government has made Gaza’s borders almost impossible to cross, except for settlers who use the high-speed bypass roads to their segregated areas. The external closure of the strip, begun in the early 1990s but drastically tightened since 2000, has effectively cut off what had become since the beginning of the occupation in 1967 a major source of employment for Gazans.

There are only two crossing points into the Gaza Strip open to ordinary Palestinians. The Erez crossing into Israel is the north has been closed since the outbreak of clashes except to a handful of workers and travelers, as well as foreigners. The Rafah crossing with Egypt, used by larger numbers of people, is frequently closed or subject to long, unexplained delays. Israeli authorities have imposed other restrictions, including a de facto travel ban on Palestinian males aged sixteen to thirty-five in effect since April 2004. Imports to and exports from Gaza, all through Israel, are strictly controlled, and the commercial checkpoint at Karni – where goods are transported directly from one truck to another without Palestinians being able to cross – is sometimes inexplicably closed.

Controls on movement within the Gaza Strip, known as “internal closure,” have also increased, mostly for the security of the settlements. The IDF has closed all but a handful of main internal roads, leaving only one route between the northern and southern halves of the Gaza Strip. The Abu Holi and Matahen checkpoints in the middle of the Gaza Strip, for example, effectively cut the territory in two, severely restricting the movement of people and goods, as well as access to health care.

According to all available indicators, the Palestinian economy has been in steep decline since the uprising began. According to the World Bank, “the proximate cause of the Palestinian economic crisis is closure.”44 In Gaza, the poverty rate between 1999 and 2003 jumped from thirty-two to sixty-four percent. Unemployment went from seventeen to twenty-nine percent.45 Average personal incomes have declined by more than a third since September 2000, and nearly one half of Palestinians live below the poverty line.46

At the same time, food insecurity rates have jumped. According to the World Food Programme (WFP), “poor households are resorting to negative coping strategies, such as selling assets, accruing debt, reducing the quantity and number of meals and cutting out on expensive foods such as meat, milk and dairy products.” Food insecurity rates have almost doubled in the past year, reaching sixty-six percent, the highest in the Gaza Strip.47 In Rafah, 89.6 percent of the population receives some food aid on a regular basis.48 As of July 2004, the WFP gave families in Gaza two thousand metric tons of food every month.49

Local and international organizations report growing problems with physical and mental health linked to violence, overcrowding, and widespread poverty in the Gaza Strip. After years of de-development and forced dependency on Israeli hospitals, Gaza health facilities are severely under-equipped. Hospitals suffer regular interruptions in access to clean water, electricity, and basic medical supplies that negatively affect clinical services, sanitation, and the prevalence of infectious disease. Access to hospitals by patients is also greatly diminished by severe restrictions on freedom of movement.50

A family from the Brazil neighborhood still lives in a tent two months after Operation Rainbow.

(c) 2004 Fred Abrahams/Human Rights Watch

The violence and destruction in Gaza have had a particularly negative impact on children. According to UNICEF, “the decline in the well-being and quality of life of Palestinian children in the Occupied Palestinian Territory (OPT) over the past two years has been rapid and profound.”51 Regarding Gaza, the psycho-social impact on children manifests itself in behavioral problems in schools and homes, as well as growing nutritional needs.52 According to CARE, 17.5 percent of children in Gaza are malnourished. Among children between the ages of six months and five years, over thirteen percent in Gaza have moderate to severe acute malnutrition, compared to roughly two percent in a normally nourished population.53

In 2004, Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon introduced a “disengagement” plan to remove all settlements from the Gaza Strip, as well as four settlements in the West Bank, by 2005. The Israeli cabinet approved the plan on June 6, 2004, with the understanding that Israel would accordingly expand its major settlements blocs in the West Bank.54

Even if the “disengagement” plan is implemented, Israel will continue to be an Occupying Power under international law and bound by the provisions of the Fourth Geneva Convention because it will retain effective control over the territory and over crucial aspects of civilian life. Israel will not be withdrawing and handing power over to a sovereign authority – indeed, the word “withdrawal” does not appear in the document at all. Instead, it will dismantle settlements and maintain military forces on the southern border of the Gaza Strip while repositioning others just outside the territory. According to press reports, the headquarters of the IDF’s Gaza Division will not be disbanded, but simply relocated to a base ten kilometers east of the Gaza Strip.55 The IDF will retain control over Gaza’s borders, coastline, and airspace, and will reserve the right to enter Gaza at will.56

Under international law, the test for determining if an occupation exists is effective control by a hostile army, not formal declarations or organizational implementation. How the occupying power organizes itself in order to exercise its attributes is irrelevant to the fact of the occupation itself.

The Israeli military has made clear that, even after “disengagement,” it will retain overall security authority over Gaza and enter the territory when it wishes. “Even if we are not deployed in the Gaza Strip, we will have to continue making sure there is no terrorism there,” IDF Chief of Staff Moshe Ya’alon told Israeli Television on May 21, 2004. “If terrorism continues here, we will have to continue entering Al-Zaytun [district in Gaza City] and Rafah and Khan Yunis, even in a situation in which we are not [permanently] deployed inside the Gaza Strip.”57

According to the Hague Regulations, “A territory is considered occupied when it is actually placed under the authority of the hostile army. The occupation extends only to the territory where such authority has been established and can be exercised.”58 International jurisprudence has clarified that the mere repositioning of troops is not sufficient to relieve an occupier of its responsibilities if it retains its overall authority and the ability to reassert direct control at will. The U.S. Military Tribunal at Nürnberg, Germany dealt with this question in the “Hostages” case:

While it is true that the partisans [armed opposition groups in Yugoslavia and Greece] were able to control sections of these countries at various times, it is established that the Germans could at any time they desired assume physical control of any part of the country. The control of the resistance forces was temporary only and not such as would deprive the German Armed Forces of its status of an occupant.59

Israel will retain overwhelming power over Gaza’s economy due to ongoing control of the territory’s borders. A World Bank study on the effects of the “disengagement” plan on the Palestinian economy determined that, while “disengagement” would ease mobility restrictions inside Gaza, the plan would have little positive effect unless accompanied by an easing of the closure regime. If accompanied by a sealing of the borders to labor and trade, the report said, the plan “would create worse hardship than is seen today.”60 The Gaza Strip will continue to use Israeli currency, the PNA will still be dependent on customs duties collected at border crossings by Israeli authorities, and the territory will still rely on Israeli telecommunications, electricity, water, and sewage networks.61

The removal of Israeli settlements from the Gaza Strip is a salutary step that would help bring Israel closer into line with its obligations under international law. It could also potentially improve the human rights situation by obviating abusive measures taken to secure the settlements. But it does not change the nature Israel’s obligations as an Occupying Power.

[35] See Human Rights Watch, Israel’s Closure of the West Bank and Gaza Strip, July 1996.

[36] Israeli-Palestinian Interim Agreement (“Oslo II”), 1995, Art. XII(1).

[37] Fourth Geneva Convention, Art. 47.

[38] See Human Rights Watch, Justice Undermined: Balancing Security and Human Rights in the Palestinian Justice System, November 2001 and Erased in a Moment: Suicide Bombing Attacks Against Israeli Civilians, October 2002

[39] See Human Rights Watch, Erased in a Moment: Suicide Bombing Attacks Against Israeli Civilians, October 2002.

[40] Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, http://www.pcbs.org/martyrs/table1_e.aspx.

[41] The figures do not include four foreign workers and three U.S. diplomats but do include Arab IDF soldiers. Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Victims of Palestinian Violence and Terrorism since September 2000,” available at http://www.mfa.gov.il/MFA/Terrorism-+Obstacle+to+Peace/Palestinian+terror+since+2000/Victims+of+Palestinian+Violence+and+Terrorism+sinc.htm,as of September 23, 2004.

[42] According to statistics compiled by the Israeli human rights group B’tselem, thirty-one percent of Israelis killed by Palestinian residents of the OPT during the conflict up to August 31, 2004 were members of security forces (http://www.btselem.org/English/Statistics/Al_Aqsa_Fatalities.asp, accessed September 18, 2004).

[43] For an analysis of the closure regime during the Oslo process, see Human Rights Watch, Israel’s Closure of the West Bank and Gaza Strip, July 1996.

[44] World Bank, Twenty-seven Months – Intifada, Closures, and Palestinian Economic Crisis, May 2003.

[45] World Bank, Disengagement, the Palestinian Economy and the Settlements, June 23, 2004.

[46] Ibid.

[47] World Food Programme News Release, “WFP Extends Emergency Assistance to Palestinians,” August 3, 2004.

[48] UNRWA and UN OCHA, “Rafah Humanitarian Needs Assessment,” June 2004

[49] Human Rights Watch interview with Mads Vejlstrup and Nehaia Abu Nahla, World Food Programme, Gaza City, July 12, 2004.

[50] See A Legacy of Injustice: A Critique of Israeli Approaches to the Right to Health of Palestinians in the Occupied Territories (Physicians for Human Rights-Israel, November 2002).

[51] “At a Glance: Occupied Palestinian Territory,” UNICEF website, available at http://www.unicef.org/infobycountry/opt.html (accessed October 4, 2004).

[52] Human Rights Watch interview with Joachim Paul, UNICEF, Gaza City, July 12, 2004.

[53] Care and Save the Children, “Humanitarian Update on the West Bank and Gaza,” April 2003.

[54] See, inter alia, exchange of letters between Sharon and George W. Bush, April 14, 2004, available at http://www.mfa.gov.il/MFA/Peace+Process/Reference+Documents/Exchange+of+letters+Sharon-Bush+14-Apr-2004.htm, (accessed August 12, 2004).

[55] Amos Harel, “IDF Finalizes Pullout Plans, May Call Up Reservists,” Ha’aretz online, September 20, 2004.

[56] “Revised Disengagement Plan – Main Principles,” adopted June 6, 2004, Art. 3(1).

[57] BBC Monitoring Middle East, “Army Head: Israel Would be ‘Forced to Hit’ Protesters Marching on Settlements,” Israeli TV, May 21, 2004.

[58] Hague Regulations, Art. 42.

[59] USA vs. Wilhelm List et al. in Law Reports of Trials of War Criminals, Volume VIII (United Nations War Crimes Commission, 1949), p. 56.

[60] World Bank, Disengagement, the Palestinian Economy and the Settlements, June 23, 2004.

[61] “Revised Disengagement Plan – Main Principles,” adopted June 6, 2004, Arts. 8,10.

| <<previous | index | next>> | October 2004 |