<<previous | index | next>>

III. The Battle for Kabul: April 1992-March 1993

[Washington Post, May 3, 1992] Kabul today is anything but a city basking in triumph. . . . [R]ockets and shells continue to crash into residential neighborhoods, fired by the forces of fundamentalist guerrilla leader Gulbuddin Hekmatyar. . . . Hundreds of civilians lie in hospitals lacking electricity, water, and basic sterilization equipment. More arrive each day. . . . Heavily armed, ethnically divided guerrillas and militiamen prowl the city streets, defending patchwork blocks from their rivals, speaking in heated tones about their various enemies and sometimes looting homes and shops. . . .22

The small measure of calm restored after Hekmatyar’s retreat to the south was not to last. Many of the factions still in the city were openly hostile to one another, and Hekmatyar still wanted a major share of power in the new government.

After peace talks between Massoud and Hekmatyar on May 25, the government initially agreed to name Hekmatyar as prime minister, but the agreement collapsed in less than a week, when President Mujaddidi’s plane came under rocket fire as he returned from a trip to Islamabad on May 29. Mujaddidi claimed that both Hekmatyar’s forces and former agents from the Najibullah government had conducted the attack, and that Hekmatyar had earlier threated to shoot down his plane.23 Meanwhile, Hekmatyar continued to demand that Dostum’s Uzbek militias leave Kabul (which might then allow him to seize the city and expel Massoud’s forces).24 By May 30, Jamiat and Junbish forces were again fighting with Hetmatyar’s forces in the south of the city. Hekmatyar began shelling and rocketing Kabul in early June, hitting all areas of the city, and Junbish and Jamiat forces shelled areas to the south of the city. Meanwhile, Sunni Ittihad and Shi’a Wahdat factions in Kabul began fighting with one another in west Kabul.

As shown in sections below, the fighting between Jamiat and Hezb-e Islami, along with the clashes between Ittihad and Wahdat and later conflicts between Wahdat and Jamiat, led to tens of thousands civilian deaths and injuries, and caused hundreds of thousands to flee Kabul for safer areas.

A: April – December 1992

Ethnic fighting in West Kabul and the Hezb-e Islami attacks on Kabul

This section describes inter-factional hostilities in West Kabul and rocket and artillery attacks on Kabul by Hezb-e Islami forces to the south of the city. The section concludes with a section discussing the violations of international humanitarian law and human rights law which took place during these hostilities.

Wahdat, Ittihad and Jamiat in West Kabul

In May 1992, mere days after Hekmatyar was first driven from Kabul, the predominately Sunni-Pashtun Ittihad forces (under Abdul Rabb al-Rasul Sayyaf) and the predominately Shi’a-Hazara Wahdat forces (under Abdul Ali Mazari) began skirmishing in west Kabul, shooting rockets at each other and engaging in street battles. Each sought to dislodge the other from various neighborhoods or government buildings which each force occupied.

The battles, taking place in the midst of a dense civilian setting, predictably caused high numbers of casualties and lead to widespread destruction of civilian homes and infrastructure. The battles also became increasingly meaningless as the buildings each side occupied in the areas in dispute disintegrated into rubble. Much of west Kabul remains in ruins as of mid-2005, mostly because of fighting in 1992-1996.

There is no single explanation of which side started the fighting between Ittihad and Wahdat. Some observers believe the first problems arose over a relatively mundane issue: posters. Ittihad and Wahdat forces were reportedly tearing down posters of each other’s leaders—Mazari and Sayyaf—which in turn led to arguments between the two side’s troops, in turn leading to conflict between the forces.

A high-level Afghan military officer, General Mohammed Nabi Azimi, who served as a Soviet-era general and was cooperating at the time with the new government to create a national army, recounted in his 1998 memoirs the beginning of the fighting between Wahdat and Ittihad forces:

The first battle between Hazaras and Ittihad-e Islami began on 31 May 1992. First, four members of Hezb-e Wahdat’s leadership were assassinated in the area near the Kabul Silo—Karimi, Sayyid Isma’il Hosseini, Chaman Ali Abuzar, and Vaseegh—of whom the first three were members of the central committee of the party. Shura-e Nazar [i.e., government officials] informed Hezb-e Wahdat that Sayyaf’s men had assassinated them. Next, the car of Haji Shir Alam [a top Ittihad commander] was stopped by Hezb-e Wahdat near the Pol-e Sorkh area, and after releasing him, there was firing at the car which killed one of the passengers.25

Regardless of the proximate causes of the first clashes, the fact that conflict arose between Ittihad and Wahdat forces was not suprising. There was high tension between Wahdat, who were predominately Shi’a Muslims, and the Sunni Ittihad faction, whose members follow an ultra-conservative Islamic creed, Wahabbism, which views Shi’ism as heretical. A great deal of tension was also caused by the influence of foreign combatants and foreign military advisors and intelligence agents from Iran and possibly Saudi Arabia, who were working with some of the factions—Iranians with Wahdat and Saudis with Ittihad. Numerous Iranian agents were assisting Wahdat forces, as Iran was attempting to maximize Wahdat’s military power and influence in the new government. Saudi agents of some sort, private or governmental, were trying to strengthen Sayyaf and his Ittihad faction to the same end.

Rare ceasefires, usually negotiated by Jamiat commanders, representatives of Mujaddidi or Rabbani, or officials from the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), commonly collapsed within days. Compounding the problem, some of the other parties in Kabul periodically joined the fighting at various times, serving to intensify the conflict. Harakat forces sometimes joined the fight with Wahdat against Ittihad. After Wahdat attacked Jamiat positions in July 1992, and hit civilian areas around them, Massoud’s troops launched retaliatory artillery attacks on west Kabul (which likewise killed numerous civilians).26

Human Rights Watch interviewed scores of witnesses and victims of the fighting in west Kabul in 1992 who described the violence and its effect on the civilian population.

S.K., a health worker in a hospital in west Kabul, described the horror of everyday life after fighting started in Kohte-e Sangi, a neighborhood in the west:

What can I say? What I saw in those days I can never forget. Hundreds of people were wounded when they fought—every time they fought. The hospital would be full of patients, overwhelmed; we couldn’t treat everyone who was brought there. People were dying in the halls. People would not get treatment. There were dead bodies everywhere, and blood. When the fighting was very bad, and we couldn’t transport anyone anywhere, there would be dead bodies in the hospital for weeks at a time. . . . Whenever the journalists came, they would ask the same questions: “How many rockets hit? How many were killed? How many were injured?” That’s all they were interested in. . . .

I saw dead bodies in the streets, and everywhere, all around west Kabul. In the hospital there were so many dead bodies, and because of the fighting, people could not come to take away the bodies.27

S.K. said that hospitals in west Kabul were repeatedly hit during the fighting between Ittihad/Jamiat and Wahdat. “One time, the children’s ward at the hospital was hit, and twice the operating theatre. Patients were killed, and staff.”28

A Kabul resident told Human Rights Watch about terrible scenes he encountered in west Kabul early in the summer of 1992:

My wife was delivering our first child. Because I was poor, we were in our home, we could not leave to go anywhere [i.e. to a hospital]. So my wife told me to bring her sister, to help. So I went to west Kabul, to Qargha [on the border of Paghman district], to get her. . . . [T]he fighting had started while I was there. So we took the road up through Afshar. So we were going on the road, my sister-in-law on the bicycle behind me.

From Qargha to Afshar, on the road, I saw many corpses—seventeen, eighteen, I don’t know—all civilians. They were commuters, people riding on the road [i.e., on bicycles], not fighters. Their bodies were swollen up. Also, I saw combatants, Hazaras, tied to trees, shot dead. I saw four fighters like this. My sister-in-law, of course, was very upset, and she started vomiting, so I had to stop. She was vomiting, and could not go on. Till this day, she does not eat meat. . . . So we turned back. We went back to Qargha, and then we went on another road. . . . When I got to my home, my wife had delivered my first child, and my first child was dead. To bury him was very difficult, with so much fighting going on, it was very difficult.29

An Afghan journalist who worked regularly in west Kabul through 1992 described how the fighting typically took place:

They were constantly shelling the civilian areas of west Kabul, and Afshar. . . . Shura-e Nazar would sometimes attack them from the zoo, and the silo [a grain warehouse in west Kabul]. Sayyaf’s forces would attack from the west: Dasht-e Barchi [to the southwest] and Kohte-e Sangi [central west Kabul]. West Kabul was destroyed by the fighting between Ittihad and Wahdat, and by the artillery and rockets fired by Shura-e Nazar off of Television Mountain and Mamorine [the two peaks in the center of Kabul city]. . . . I went to a lot of places where the rockets and shells would fall. I saw many bodies, terrible sights. 30

The first week of June 1992 was particularly bad, as Hekmatyar’s forces were also launching artillery attacks on the city from the south.31 (For more on Hekmatyar’s shelling of the city, see the following section). Jamilurrahman Kamgar, a resident of Kabul who later published his contemporaneous chronicle of events in this period, wrote of heavy clashes between Wahdat and Ittihad forces, including attacks on a government mediator attempting to stop the fighting (June 2); the abduction of dozens of civilians by Hazara and Ittihad forces (June 3); hundreds of injuries and deaths, the Red Cross hospital filled to capacity, and hundreds of families forced to leave destroyed houses (June 5).32

Sharon Herbaugh, a correspondent with Associated Press who died in a helicopter crash north of Kabul in 1993, filed a dispatch on June 5:

[Friday, June 5, 1992] -- [A]ttacks continued, and more shops, schools and homes were destroyed in the ravaged capital. At least 20 more people were killed and 100 others injured. . . . Rival forces pounded each other with rockets and mortars, destroying entire blocks of shops and houses, and knocking down power lines. In downtown Kabul, rockets slammed into three empty schools, killing four passers-by and setting fires. Missiles also fell on a house in northern Kabul, killing a family of six, witnesses said. Unidentified gunmen raked a row of shops near the Kabul zoo, killing or injuring 10 people, witnesses said. . . . Residents in predominantly Shiite neighborhoods also accused Sunni rebels of looting shops and houses, killing prisoners, gouging out the eyes of wounded guerrillas and burning dead bodies.33

A journalist from Agence France-Presse saw hundreds of civilians fleeing from the west the same week, and witnessed some being shot by random gunfire and wounded children being carted to hospitals in wheelbarrows.34

One civilian who lived near the large grain silo in west Kabul described fighting between Wahdat and Ittihad that he believes took place in June 1992, right after a brief ceasefire:

People were really hoping [the ceasefire] would last: they were moving about, doing things that they hadn’t been able to do until then. . . . It was around nine o’ clock in the morning.

Suddenly, there was an explosion and a lot of firing of weapons. Everything was bullets, it was very severe. Everyone was rushing to flee from the violence. Husbands forgot wives, brothers forgot sisters, mothers forgot children, uncles forgot nephews—everyone was running away, and could only think of safety. . . . People were fleeing into our neighborhood because it was controlled by Shura-e Nazar. Wahdat was attacking from the south side of Kohte-e Sangi [a traffic roundabout south of the silo], and Sayyaf’s forces were in Khushal Khan [to the west of the silo]. Both sides wanted to seize the property in that area: they wanted to use the places there to establish military positions. Both sides marched into the civilian areas and took up positions in people’s houses. They were shooting at each other with rockets, guns, all sorts of weapons.

My house was where Shura-e Nazar had a checkpoint. I could see the women and men rushing away from the fighting, running down the street towards us. At the same time, some of the bullets, or shrapnel from the explosions, was hitting people. So men and women were falling down into the street. They would be running, and then the bullets would hit them, and they would fall down. The other people just kept running, and were not bothering to save those who fell. They were all rushing to save themselves. It was a terrible day. . . .

They were shooting everywhere. Everything was being hit: civilians, anything. Sayyaf’s forces were shooting off their guns and rockets, they were flying into the side of Mamorine mountain [behind the silo], where there are houses and where the civilians were fleeing to, behind the silo. Rockets were going everywhere. The fighting lasted until dark. Sayyaf’s troops came up into our neighborhood. We could see the Kandahari people [Pashtuns from Kandahar city] among Sayyaf’s troops.35

A journalist in Kabul documented severe attacks on Hazara households by Ittihad troops on the night of June 4, 1992, interviewing residents who reported that Ittihad troops had attacked and looted homes in Kohte-e Sangi, and killed six civilians. “The guerrillas were going from house to house, saying they wanted to kill all the Shi’as,” one frightened resident told the journalist.36

Fighting continued through the month and into the summer. Jamhuriat hospital, near the Interior Ministry, had all its windows blown out and closed around June 24. Journalists who visited the hospital later in the week saw “a scene of utter despair”—no doctors or nurses, surgery patients lying in their own excrement and urine.37

Rocketing and shelling by Hezb-e Islami

West Kabul was not the only danger zone in the city. As Ittihad and Wahdat fought in the west, with occasional flare-ups involving Jamiat, Hekmatyar’s Hezb-e Islami forces to the south continued to launch attacks on the city with rockets and artillery—attacks which were often aimed at the city as a whole, and not directed at specific military targets. Cumulatively, these were the most deadly attacks of the period.

President Mujaddidi handed over formal power to Rabbani at the end of June—as provided for in the Peshawar Accords—although Rabbani and Massoud’s forces already controlled most security apparatuses and ministries in the capital. Hekmatyar continued to refuse to join the government. Hekmatyar’s Hezb-e Islami forces increased their rocket and shell attacks on the city. Shells and rockets fell everywhere.

Conditions were such that anyone in Kabul could be killed at any time, almost anywhere: rockets and shells would hit homes, offices, bus stations, schools, or markets.38 Kabul residents were often able to tell Human Rights Watch about rocket and artillery attacks they say they knew were launched by Hekmatyar’s forces, since they could often see rockets streaking in from the southwest, from areas under Hezb-e Islami control, or hear artillery being fired from the same area.

President Sibghatullah Mujaddidi’s damaged airplane sitting on the tarmac at Kabul airport, May 29, 1992. The airplane, which had ferried Mujaddidi back from Islamabad, came under rocket attack while approaching Kabul airport. During the attack, the airplane’s nosecone was sheared off and the co-pilot suffered shrapnel wounds, but the pilot managed to land safely. Mujaddidi, who was unharmed, blamed the attack on both Hekmatyar and agents of the former communist government. Jamiat and Junbish forces attacked Hekmatyar’s Hezb-e Islami forces in the south of Kabul the next day. © 1992 Ed Grazda

One resident described to Human Rights Watch a rocket attack in the summer of 1992:

Hekmatyar would rocket civilian areas all the time. One time, in the summer of 1992, I was standing behind the ministry of education, in Da Afghan Nan. I was waiting for a bus. A poor old man had a little cart and was selling chocolate and peanuts and almonds. The bus came, and it moved past me, so I moved down the block to get on the bus. I was getting on the bus, and suddenly, a rocket hit, where I had been. That man disappeared completely. No one found even one piece of his flesh. He completely disappeared. I think that 20 other people died there, and many more were wounded.39

A woman in west Kabul described indiscriminate shelling in the west of Kabul in June 1992. She believes the attacks were by Hekmatyar’s forces south of Kabul, since she heard artillery firing to the south during the attack:

It was about 4 p.m., and I was baking some bread outside, over a fire. Suddenly, there was a big explosion. I took cover, on the ground. Then, there was another explosion. I got up and I could see this woman here [pointing to a neighbor who is crying], and she was just running about. [The women asked her neighbor to tell her story for her, and nodded throughout.] Her son had been sitting near this wall outside, where the artillery landed, and he was completely blown up. This woman here was running about, collecting pieces of [his] flesh in her apron, and crying. Her son’s name was Sakhi. He was completely blown up, disappeared. Her grandson, Mukhtar, was also killed in the same explosion.40

A middle-aged man described a rocket attack that occurred around the same time, when Hekmatyar was firing rockets and artillery regularly into the city:

We were in Micrayon 3 [in the east of the city, controlled by Jamiat and Junbish forces], it was about three o’ clock in the afternoon. I was near this man’s house, Alaz. We were in his yard, by a tree. He had some tomato plants, there were some good tomatoes, and I was asking him how much they cost. Suddenly there was a missile, and it hit the land, about 40 meters away. I dove to the ground. After a minute, I saw Alaz. He was bleeding. He was still alive. I asked him, I said, “Let’s go to the hospital!” But he said: “No, there’s no time. I am about to die.” I held him, and then I carried him—he was bleeding from the side, the left side. My clothes were soaked with blood. The family came and gathered, they were screaming and crying. After about ten minutes, he died. This was in Block 19, in Micrayon.41

A journalist working in Kabul recounted seeing the terrible effects of the attacks in Kabul hospitals at the time, hospitals filled after the city came under fire from the south:

I remember pretty terrible scenes from those days, from the hospital. I saw children, kids, women wounded. Kids with their legs blown off. I once saw some kids arriving at the hospital in a car; their legs had been blown off by a bomb and they were just lying in the boot of the car. They were shelling into the city. It was Hekmatyar’s forces.42

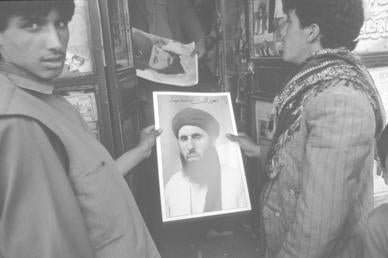

Two young men in Kabul hold up posters of Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, the military and political leader of Hezb-e Islami. © 1992 Ed Grazda

A photojournalist described the typical scene at a hospital in west Kabul after rocket attacks: “There’d be four or five bodies by the door, some coffins, then the bodies inside. . . . It was a grim scene, bleak. These rockets would rip pieces out of you.”43

In August 1992, Hekmatyar’s forces—who had already been rocketing civilian areas regularly since April—launched a new artillery and rocket blitz, bombarding all areas in Kabul held by Jamiat, Junbish, Ittihad, Harakat, and Wahdat—essentially the whole city. The apparent aim of the blitz was to force the government into a political compromise with Hezb-e Islami, as Hekmatyar likely did not have enough troops to launch an actual invasion of the city.

During the attack, hundreds of homes were destroyed, approximately 1,800 to 2,500 persons were killed, and thousands more were injured.44 Governmental functions, already severely hampered, ceased. The Presidential Palace and numerous government buildings were hit, as well as the headquarters of the Red Cross and at least two of its hospitals. The city’s water and electricity grids were severely damaged.45 On some days, shells and rockets fell without interruption, and the city was gripped with terror.

The contemporaneous notes of a Kabul resident, Jamilurrahman Kamgar, who was quoted above, chronicle the daily barrage:

August 1, 1992: Kabul’s airport came under rocket attack. Hezb-e Islami took responsibility and said [via the radio]: these attacks were a response to the government’s attacks on southern Kabul yesterday.

August 2, 1992: Nearly 150 rockets hit different parts of Kabul; the government blamed Hekmatyar. . . . As a result of the attacks, many people were killed.

August 5, 1992: The recent missile attacks have killed 50 people and injured nearly 150.

August 10, 1992: At 5 a.m. there was heavy fighting between government forces and Hezb-e Islami. The government said that Hezb forces attacked from three directions, Chelsatoon, Darulaman and Maranjan mountain. There was not enough medicine in the hospitals and medical personnel could not be seen. A shell struck the Red Cross hospital.

August 11, 1992: Nearly a thousand rockets hit various parts of the city of Kabul. The airport sustained at least 250 hits. It’s possible that a thousand people were killed. These attacks came from Hekmatyar’s direction. . . .

August 14, 1992: The war is progressing severely. The people of Kabul are escaping. The Pol-e Charkhi prison has become a refuge. . . .46

Ittihad and Jamiat forces, in turn, were launching artillery and rocket attacks on Hekmatyar’s positions to the south, which were also hitting civilian areas in the southwest of Kabul.

Hamid Karzai, now the president of Afghanistan and at the time a deputy foreign minister in the government, told a journalist in Kabul on August 9, 1992: “I don’t know what’s going to happen. . . . We’re just killing each other. It’s senseless.”47

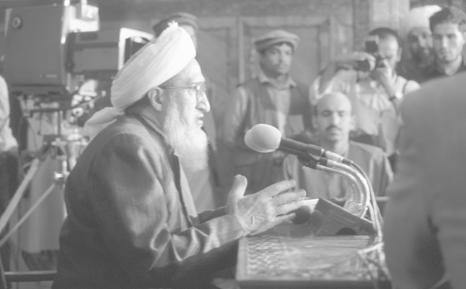

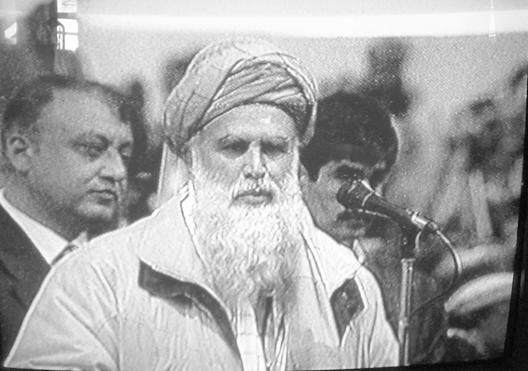

President Sibghatullah Mujaddidi speaking at a news conference in June 1992. Hamid Karzai, deputy foreign minister at the time, is visible just beyond the microphone. © 1992 Ed Grazda

Kabul’s hospitals were hard pressed to keep up with the violence. An ICRC representative in Kabul, quoted in a U.N. memorandum in 1992, described the situation on August 13, 1992 in the following terms:

This afternoon we had 353 patients in our hospital which has only 300 beds. There are patients in the entrance hall, in the courtyard. Thirty-eight wounded died before they could be treated, 77 were waiting to be operated on, 60 were admitted this afternoon, 91 yesterday and 183 Saturday.48

The chief of the United Nations mission in Kabul told journalists on August 20:

It’s a terrible situation. The government no longer controls anything; there is no longer law and order. The streets are entirely deserted, except for armed soldiers. Water and electric power have been cut off for nearly a week and my colleagues from WHO [the World Health Organization] are afraid of an outbreak of epidemics.49

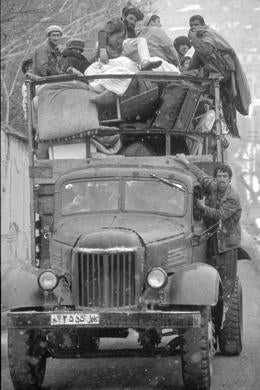

The United Nations estimated that approximately 500,000 persons fled Kabul by the end of the summer for safer areas inside and outside of Afghanistan, primarily because of Hekmatyar’s rocket and artillery attacks.50

Violations of International Humanitarian Law

The armed conflict in Afghanistan in 1992-93 was a non-international (internal) armed conflict in which the Geneva Conventions and customary international humanitarian law applied to government forces and non-state armed groups. (The specific legal status of the conflict and culpability of specific individuals are discussed in more detail in section IV below.)

Many of the events described above amounted to war crimes. Launching indiscriminate attacks that may be expected to cause loss of civilian life, or intentionally targeting the civilian population and civilian objects, are violations of international humanitarian law, amounting to war crimes. More specifically, customary international law prohibits treating an entire city as a single military objective,51 and requires belligerents to take feasible precautions to protect civilians against the effects of attacks, including choosing methods and means of warfare that avoid loss of civilian life, and to cancel or suspend attacks causing unnecessary civilian loss. In addition, deliberate and widespread killing of civilians, through prolonged indiscriminate shelling and artillery attacks, can amount to crimes against humanity.52

Individuals—combatants and civilians—are criminally responsible for war crimes they commit. Commanders are criminally liable for war crimes committed pursuant to their orders or as a matter of command responsibility. Command responsibility makes a commander culpable for war crimes committed by subordinates if the commander knew or had reason to know such crimes were being committed and did not take all necessary and reasonable measures to prevent the crimes, or punish those responsible for crimes already committed.53

With respect to Wahdat, Ittihad, and Jamiat hostilities in west Kabul, there is compelling evidence that factions regularly and intentionally targeted civilians and civilian areas for attack, and recklesslessly and indiscriminately fired weapons into civilian areas. There is little evidence that the factions made meaningful efforts during hostilities to avoid harming civilians or stopped attacks once the harm to civilians was evident.

One Afghan journalist, quoted above, told Human Rights Watch that he witnessed on several occasions Ittihad and Wahdat forces intentionally firing rockets into occupied civilian homes during hostilities in 1992.54 He also said that Jamiat forces, once they joined Ittihad in battling Wahdat late in 1992, regularly fired randomly into civilian areas in west Kabul:

It was a normal, everyday experience that they would fire off of the television mountain, and from the top of Karte Mamorine, at Dasht-e Barchi, Karte Seh [District 3], and Deh Mazang. Also, on Koiatub [or Koiatab] mountain, there was a tank on top of it. This was the place that during the King’s time [before 1973] they would fire off a canon there, everyday at 12 noon. They would fire from there also.55

A former high-level official in Shura-e Nazar confirmed that Jamiat troops on the Mamorine mountain (the western peak next to Television Mountain and above west Kabul) regularly launched rockets and artillery into the civilian areas of west Kabul in 1992 and 1993.56

“There was little effort [by any of the factions] to aim at targets,” an international journalist told Human Rights Watch, describing the fighting between Wahdat, Ittihad, and Jamiat.57 “It was Massoud and Sayyaf versus the Hazaras. Deh Mazang [an area in west Kabul] was a front line. They would shoot at anything in between, whatever it was.”58

S.K., a hospital worker quoted above, also told Human Rights Watch about the attacks on civilians by Jamiat forces stationed on Television Mountain in the center of Kabul:

There was a time when the Jamiat troops on TV Mountain would target anything on Alaudin Street [the main road running north-south through Karte Seh]. They would target anything that moved, even a cat. . . .

I remember [one time] I went out to go to this clinic [to obtain medical equipment], and as soon as they saw me on that mountain they were shooting.

Anything that looked like a human being would be targeted. They shot everything: rockets, shells, bullets. There were times when the streets were littered with bullets. . . .59

A photojournalist who worked in Kabul regularly during 1992, and visited numerous military posts, told Human Rights Watch about Jamiat forces firing into civilian areas from the same mountain:

Yeah, they’d fire off T.V. Mountain all the time. Some of the wackos up there, they’d get bored. They’d strafe the neighborhoods below with anti-aircraft fire. For fun—just for the hell of it. The civilian homes below, near the zoo, by the traffic check-post, near the silo. They wouldn’t aim at any ministries [government buildings], that’d be their own turf. No, they’d fire toward the southwest, and not just at Wahdat but at civilians. And there were Tajiks down there too [same ethnicity as Jamiat], not just Shi’as [Hazaras are predominately Shi’a].60

Wahdat, Ittihad, and Jamiat forces regularly used imprecise weapons systems, including Sakr rockets and UB-16 and UB-32 S-5 airborne rocket launchers clumsily refitted onto tank turrets. The aiming of these rocket systems are considered “dumb” or non-precision.61 Sakr rockets are “like bottle rockets,” according to one military analyst,62 and rocket systems generally as not designed for accuracy in close combat: they cannot be adequately aimed within urban settings or made to distinguish between military targets and civilian objects. The use of the makeshift S-5 system in particular, within Kabul city, demonstrated an utter disregard of the duty to use methods and means of attack that distinguish between civilian objects and military targets.63

Further research is needed into the exact command structure of the Wahdat, Ittihad, and Jamiat forces involved in the fighting detailed above. Discussion of the command structure of the Wahdat, Ittihad, and Jamiat forces, and the responsibility of individual commanders, appears in sections below and in Section IV.

Hezb-e Islami forces used artillery and rockets in a manner indicating that they were intentionally targeting civilian areas, failing to properly aim (with respect to artillery guns), recklessly using weapons which could not be aimed in a dense civilian setting (with respect to rockets), and treating the whole city as one unified military target.

With respect to artillery attacks, there is evidence that Hezb-e Islami had the capacity to aim artillery at military targets, but either recklessly chose not to do so, or intentionally aimed artillery at civilian objects instead, in violation of international humanitarian law. As the primary recipient of international assistance and training from Pakistan, the United States, and the United Kingdom, Hezb-e Islami was arguably the most well-trained mujahedin group in Kabul at the time. Many commanders and troops were trained by Pakistani, American, and British experts on the use of rocket and artillery systems. Journalists who visited sites held by Hezb-e Islami forces to the south of Kabul saw numerous D-30 122mm cannons that were being used for attacking Kabul—a relatively precise artillery system.64 Reporting and footage from 1992 and 1993 suggests that Hezb-e Islami forces could, when they wanted to, precisely aim such artillery: BBC film footage from May 1992 shows accurate targeting of artillery by Hezb-e Islami of Jamiat and Junbish positions in Kabul.65 Terence White, a correspondent with Agence France-Presse, reported precise artillery fire against Jamiat positions in south Kabul in early 1993.66 Yet in many cases, including ones documented in this report, Hezb-e Islami artillery and rockets hit civilian areas, suggesting that they were either purposely targeting such areas, or recklessly aiming at Kabul as a whole. The prolonged timeframe in which the attacks took place, their scope, and their continued inaccuracy, strongly suggest there was neither a fixable problem with artillery aim calibration, nor weapons systems’ failure. Accurate and aimable weapons were being shot into civilian areas in violation of international humanitarian law.

Hekmatyar’s forces also often used BM-40, BM-22, BM-12 rocket launchers and Sakr Soviet-made rockets in their attacks on Kabul.67 As noted earlier, such rocket systems are generally considered “dumb” or non-precision: these weapons are not designed for accuracy in close combat and cannot be adequately aimed within urban settings or made to distinguish between military targets and civilian objects.68 The very use of such rocket systems within Kabul may have been an indiscriminate method or means of warfare in violation of international humanitarian law.

The pattern and characteristics of the attacks also suggest that Hekmatyar and his commanders were attacking the whole city, or treating the city itself as a single target.69

General Mohammed Nabi Azimi’s memoirs, discussing the July and August blitzes, reinforce the view that Hekmatyar’s forces bombarded civilian areas intentionally:

So once again, Hekmatyar’s heavy weapons roared and rained fire on Kabul. The height of the fighting and clashes was in late July and early August 1992. As soon as it became light, Hekmatyar’s rocket launchers and artillery would come to life. Hekmatyar now controlled the Takht-e Shahi heights which command Kabul [to the south]. There, the artillery teams had wireless communication sets. Hekmatyar’s artillery teams were reinforced by trained officers. . . . Hekmatyar could now accurately fire on military targets. But he preferred to fire on the city and defenseless civilians in order to create tension and dissatisfaction among the people against Rabbani and Massoud.70

“They weren’t picking out military targets,” one journalist who witnessed the repeated attacks in Kabul told Human Rights Watch. “Once the shelling started, artillery would fall everywhere, across the city. Across the city, you could hear the shells.”71

The pattern of casualties, and how so many civilians died, suggested that they were firing indiscriminately. . . . I suppose, yes, they hit some military targets, whatever that means, but mostly the bombs were just hitting various parts of the city, and it was mostly civilians who were getting hit, as you would see at the hospital.72

Marc Biot, a medical official at the Jamuhuriat hospital, told Human Rights Watch:

It was like this: At any moment a missile could fall. . . . When you were outside, you never knew if a missile would fall on your head. They were shooting them blindly, anywhere: into roads, markets, houses. . . . The most awful thing was that any bomb could fall on any place at any time. There was a clear political will to shell the city, as a city—to shell the city as a civilian place. The shelling was ubiquitous, everywhere.73

One journalist cited above, who visited Hezb-e Islami positions to the south of Kabul, suggested to Human Rights Watch that artillery spotters must have been intentionally directing artillery at civilian areas:

We talked to the officers pretty regularly—they had spotters, observers. They insisted they were hitting military targets. But they [the officers] knew what was going on. Both Massoud and Hekmatyar had a lot of artillerymen who were trained. They could aim. Elevation and windage [lateral and vertical movement] could be changed. But they [Hezb-e Islami forces] were aiming into the city. They had spotters in the city: Hezb-e Islami were able to infiltrate Kabul, it was easy. The aim was to terrorize the population.74

The testimony above suggests that Hezb-e Islami and Hekmatyar were deliberately targeting the city of Kabul as a whole entity, to terrorize and kill civilians.

Further investigation will be needed to determine the role of specific commanders in the attacks. According to the Afghan Justice Project, an independent non-governmental group that has investigated military operations in Afghanistan from 1979 through 2001,75 besides Hekmatyar the following commanders had operation control over the military posts firing artillery and rockets at Kabul during the period discussed in this report:

- Commander Toran Khalil, chief artillery officer in Hezb-e Islami who supervised shelling and rocketing operations during late 1992 into 1993, commander of a base at an oil depot at the south of Charasiab, south of Kabul.

- Toran Amanullah, commander of the Firqa Sama, stationed at the Rishkor military base, south of Kabul.

- Commander Zardad, commander of a military post at the Lycee Shorwaki.

- Engineer Zulmai, of the Lashkar Issar, commander of a post at the Kotal Hindki pass to the south of Chilsatoon, south of Kabul, near the Rishkor base.

- Nur Rahman Panshiri, commander of a post in the village of Shahak, to the southeast of Kabul, directly controlled by the Sama division.

- General Wali Shah, an officer in the Najibullah government who joined Hezb-e Islami in 1992, commander of a base at Sang-e Nevishta, Logar, south of Kabul.

- Shura Nizami (military council) commanders Faiz Mohammad, Kashmir Khan, and Sabawon.

The legal responsibility of these Hezb-e Islami commanders, as well as Hekmatyar himself, is discussed further in section IV below.

Abductions, “Disappearances,” Torture, and Other Mistreatment of Detainees

[Reuters, June 4, 1992] Gunfire and explosions echoed across western Kabul. . . . Guerrillas of the Hezb-e-Wahdat Shi’a alliance fought gunbattles with Sunni Ittehad-i-Islami fighters close to Kabul university, a Shi’a base, for the third day running. . . . Guerrillas of the two groups rounded up hundreds of civilians at gunpoint on Tuesday and Wednesday and took them to makeshift detention centres after demanding to see identity papers, which state the bearer's ethnic group, at street checkpoints. Shi’a guerrillas took away Sunni Muslim ethnic Pashtuns, while Ittehad guerrillas detained ethnic Hazaras, who are Shi’as. Witnesses said some people were beaten with sticks as they were led away. . . .76

In addition to the war violence, the fighting between Ittihad and Wahdat through 1992 was spawning another problem with especially terrible effects on civilians: ethnic abductions. Ittihad and Wahdat forces were increasingly abducting civilians and holding them for ransom or exchange—Ittihad holding Hazaras, and Wahdat holding Pashtuns, Tajiks, and other non-Hazaras. A journalist told Human Rights Watch:

There was a lot of kidnapping in the west. The commanders under Sayyaf and the commanders under Hizb-e Wahdat would stop buses or cars, and look for Hazaras and Pashtuns. Sayyaf’s men would look for Hazaras. Hizb-e Wahdat forces would look for Pashtuns.77

As shown below, the practice seems to have begun in May of 1992. Gen. Mohammed Nabi Azimi, the high-level military officer quoted earlier in this report, described how the two forces began erecting checkpoints and engaging in routine abductions:

Hazaras abducted Pashtuns and Pashtuns abducted Hazaras wherever they saw each other. They pulled out the fingernails of prisoners, cut off hands, cut off legs, even hammered nails into prisoners’ skulls. Humans were kept in [shipping] containers and containers were set on fire. . . . Cruelty, injustice, and inhumanity began, and became a chronic disease; humanity and honor were crucified.78

Many of the civilians abducted by the two sides during this time were never seen again. Some did manage to be released, however, usually after prisoner exchanges or personal interventions by government officials or religious or tribal leaders with connections to those detained.

Human Rights Watch spoke with several former detainees in Kabul in 2003—Hazaras, Pashtuns, and Tajiks—who described their experiences. Their stories follow:

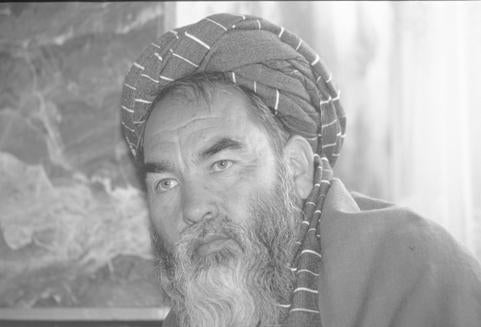

Abdul Ali Mazari, the military and political leader of Hezb-e Wahdat in the early 1990s. Mazari’s faction, as well as Abdul Rabb al-Rasul Sayyaf’s Ittihad faction, committed war crimes and other atrocities in west Kabul in the early 1990s. © 1994 Robert Nickelsberg

Abductions by Wahdat

A young Tajik man from west Kabul, who said he was held by Wahdat forces in December 1992 after some streets fighting that occurred near the government silo, told Human Rights Watch about his abduction and detention by men he identified as members of Wahdat:79

[M]y brother came and said he wanted us to leave the area with him. We were talking about this, sitting in our home, drinking tea, when some gunmen [Wahdat] came and knocked on the door.

“Whose house is this?” a commander said. He was at the door. —“It is mine,” I said. —“What is your name?” I said my name was [deleted]. —“Where are you from?” he asked. —“Kabul,” I said. —“You’re lying,” he said. He pulled out a list, and found my name on the list: my parents and brothers names were on the list also, and next to my name it said we were from Shomali [a predominately Tajik area north of Kabul]. The commander said, “Are you from Shomali?” And I said yes, that I was studying in Kabul and lived there. He said, “Let’s go inside,” and pushed me into my own house. As I came in, I told my brother [with my hands] to hide himself, but he didn’t understand. So then the commander saw him also. . . . Before taking us away, they arrested a guy from Wardak next door. He was complaining a lot, so they blindfolded him. . . . They put us all in a vehicle, and when we got to Kohte-e Sangi they put blindfolds on us too. After that, we couldn’t see and could not understand where they were taking us. . . .

When the vehicle stopped, the men assumed they were at Dasht-e Barchi, where Wahdat had a base, but the man later discovered he was at Onchi Baghbanan [to the north of Dasht-e Barchi, about 4 kilometers west of Karte Seh].

We got out. They threw the three of us into a container . . . . Then, a commander with two bodyguards came, and he came into the container, and questioned us. “You both are some guys from Shomali and you are helping Massoud!” he said. —I said, “I am a medical student; neither I nor my brother are soldiers. We are from Shomali, but we are not soldiers.” —“Keep quiet,” he said. And then the guards cocked their Kalashnikovs [assault rifles]. The commander signaled to his troops to take us away. We were blindfolded, and made to walk somewhere else. They were kicking us. Finally, we were imprisoned in a small room.

The man said he and the other prisoners were later given a plate of rice to share. But that night, other prisoners were brought in and together they were transported to another site:

We drove there. Then they threw us into a basement—no, the basement of a basement. It was dark, and dirty, and very cold. We could hear machine guns were being fired above us. We assumed that we were somewhere near the front line.

That night, they brought three other guys: a guy from Jalalabad, a worker from Shomali, and a lecturer from the university. They were also thrown into the basement with us. There was not enough room for us. There was dirty air, and it was completely, completely dark. We were there for several days. They would let us out two times a day, to urinate.

The basement room was freezing, and the young man said at times he was so numb that he feared he was going to die. After a week, the man and his brother were released, apparently because of the intervention of relatives who were able to make contacts with Wahdat commanders. But the man said his fellow prisoners met a different fate:

Those other people who we were imprisoned with were never released. They disappeared. I know because they told us to find their families. And I contacted their families, several times. Those families pressured us, to help them. We gave them some advice. But a month later those prisoners were not released. And later on, when I spoke with them again, I learned that those prisoners had never been released.

An elderly Pashtun man described being arrested by Wahdat forces in mid-May 1992, and seeing other prisoners killed by them:

It was morning, I was going by Chelsatoon garden. I was with my 10-year-old son. We were stopped by Hezb-e Wahdat troops. Two men. They took us to Habibi high school. They didn’t give me any problems at first, they were just questioning me. . . . But I saw this container nearby, with prisoners. The two men were arguing. One was saying, “Leave him, he’s innocent.” The other was saying, “No, we should arrest them because they’re Pashtuns.” They had arrested some other Pashtuns, and I saw them putting them into a container there.

The first one was saying, “Put him in the container!” And the other was saying, “No, he has a young kid with him.” Then the first one was saying, “No—he is Pashtun. Put him in the container!” Their argument lasted a few minutes. Finally, they let me go and I was set free.80

The man said the troops sometime soon after apparently fired a missile or rocket-propelled grenade into the container:

I was walking away with my son. We heard the explosion. The container had been closed after they put the prisoners in it. I heard the explosion and I looked, and then I took my son and started to move away, because we were in danger. . . . When I looked I saw that all these people were running away from where the container was. . . . I heard screams from the container and there was smoke coming out of the hole. The rocket had penetrated and exploded. . . .81

Human Rights Watch interviewed several other Pashtuns and Tajiks held by Wahdat forces in 1992 and released when family members or acquaintances were able to convince leaders in the various factions to have them released. A senior civilian official in the Jamiat-dominated government told Human Rights Watch that numerous complaints were made to the government about Wahdat arrests, and that they documented that Wahdat had set up a prison at a compound in west Kabul called Qala Khana, run by a senior Wahdat commander called Shafi Diwana (Shafi the Mad), in which prisoners were tortured and killed.82 Petitioners brought allegations to the Jamiat officials that Wahdat forces were burning the bodies of prisoners in brick-making furnaces in the compound.83

A health worker in west Kabul, quoted above, told Human Rights Watch that hospital staff in west Kabul knew that thousands of prisoners were kept by Wahdat forces in Dasht-e Barchi, and that they were sometimes able to negotiate to have them released, although most were never seen again.84

Abductions by Ittihad

As noted above, Ittihad was holding prisoners too. Human Rights Watch interviewed a Pashtun man who, despite his Pashtun ethnicity, was held by Ittihad forces in the summer of 1992 because of a non-ethnic dispute with troops. The man said he was put in detention with approximately thirty to forty Hazara prisoners who said they were abducted based on their ethnicity.85 He described his experience:

[S]ome of Sayyaf’s men, from Paghman, came and took me. They were looking for my brother-in-law [because of a private financial dispute], but they took me instead, as a hostage. They took me to Khoshal Khan Mina, the headquarters for the electric buses, near the silos. They put me in a room there, and they told me that they would hold me there, for a night, and then I would be released. The commander there was named Tourgal. But the next day, Wahdat and Sayyaf started fighting.

That night, as fighting raged outside, the man said that the Ittihad forces brought in Hazara civilians: “Sayyaf’s forces brought thirty or forty Hazara civilians. . . . They were not fighters, but civilians, old and young.” Later in the night, according to the man, the Ittihad forces shot at the prisoners in their holding cell with an automatic weapon:

[T]he fighting got severe. We could hear the artillery. There was a lot of shooting. I could hear these people, Sayyaf’s people, talking about retreating. And at one point, one of them said to Commander Tourgal, “What should we do with these prisoners?” They were speaking in Pashto, and the Hazara people couldn’t understand them. But I could understand. Somebody said, “Go and shoot them.”

I was near the door. When I heard this, I hurried away and hid away from the door, in the corner of the room [on the side of the room with the door]. A person came, and opened the door, and shot all over the room with his kalashnikov, on automatic. He just fired randomly all over the room. About ten people were killed, immediately, and four were wounded. . . . After, no one moved. We [who were still alive] were trembling with fear. The fighting outside was serious—the commander called on this guy to come back to fight at the windows with them, so the man left, to go back to fighting.

The prisoners were too afraid to move the dead bodies. But when the fighting stopped, the man desperately pleaded with the troops to release him: “The next time the troops came by, I rushed to the door and said, “Listen, I am a Pashtun, and I was not arrested with these people.” The man said the troops then put him into another room, presumably because he was not Hazara. “I don’t know what happened to the [other] people in that room,” the man said.

Ultimately, the man was released after a relative, who knew some members of Ittihad, visited Sayyaf in Paghman, to plead for his release. The relative told Human Rights Watch that Sayyaf ordered another minister (the name is deleted here to protect the man and his relative) to order the man’s release.86 The minister then wrote an order to Commander Tourgal, the relative said, which he took to Tourgal, who then released the prisoner—a series of events that suggests that Sayyaf had knowledge of Ittihad’s regular detention of civilians and that he had control over the commanders holding them.

Human Rights Watch interviewed numerous other Hazara men in west Kabul who were held by Ittihad forces in 1992 and early 1993, forced to work in manual labor for Ittihad forces (their stories are in the following section: “The Attack on Afshar”).

Abuse of Prisoners

Human Rights Watch received consistent and credible testimony that many of the persons detained by Wahdat and Ittihad were forced to work, mistreated, or tortured while in the custody of Ittihad and Wahdat forces. S.K., a hospital worker quoted above, described seeing detainees after their release from both factions who were badly injured, who told her they had been subjected to torture and other mistreatment:

I saw hostages who had been tortured: civilians and non-civilians. This was something common: people released by each side, their families would bring them to the hospital [because they had been abused in captivity]. Wahdat would capture Pashtuns and Tajiks, and Ittihad would capture Hazaras.

I saw what they had done to them: People beaten up. People who had been tortured. They had put RPGs [Rocket Propelled Grenades] into the anus. They gang-raped girls. I saw these victims.87

Human Rights Watch interviewed several Afghan journalists who spoke with detainees in 1992 and 1993, who described abuses while in detention.88 Journalists with the British Broadcasting Corporation and Associated Press in 1992 interviewed detainees of various ethnicities who related descriptions of their arrests and abuse.89

It is likely that the abductions and abuse were fueled in part as retaliation for continuing atrocities. Abdul Haq, a mujahedin commander who served as police chief in Kabul in 1992 (Haq was later killed by Taliban forces in eastern Afghanistan in October 2001), told a journalist in 1992 that non-Wahdat and non-Ittihad commanders had worked to arrange large prisoner swaps between Wahdat and Ittihad in the first week of June, but that the exchanges collapsed after both sides saw that some prisoners had been tortured or mistreated.90

(Further descriptions of abuse of detainees captured by Ittihad and Wahdat appears in the “Rape” section below, and in the section “The Attack on Afshar” below.)

“Disappearances”

Human Rights Watch interviewed several families in west Kabul who said that their relatives had been abducted in 1992 by Wahdat or Ittihad, and never seen again. For fear of continuing threats to their security from the same factions, they refused to allow Human Rights Watch to use the names of their disappeared relatives.

In 1996, Afghan aid workers working in west Kabul published a book documenting some of the abductions and “disappearances” of persons from west Kabul, with names and pictures (when available) of victims.91 The project, based on research conducted in 1993-1995, focused predominately on Hazara disappearances at the hands of Ittihad. But the book does detail abductions by Wahdat and Jamiat as well, and partly reveals the scope of the overall problem.

The book documents 671 cases of abductions and disappearances, mostly in west Kabul and mostly in 1992-1993. H.K.,92 one of the books’ researchers, told Human Rights Watch that over 1,000 people were reported missing in west Kabul in the first year after the fall of the Najibullah government:

The number we put in the book was less, because we chose only the cases where we had some information about the how the people were kidnapped. There were more documents, with more information about the commanders, but we were pressed for time and we just published some of what we had.

It was very difficult to work on these issues at the time. One of our employees at the time was arrested by Harakat forces, and held for ransom, because of the research he was targeted. [Name deleted.] He was arrested in Dasht-e Barchi, sometime around the report research. He told us later that they beat him severely while he was held.93

H.K. said that the project staff tried to obtain the release of some of those who were held by the different forces:

Almost everyone we documented was never heard from again. However, in a few cases, rare cases, where we had all the information about who captured a person, and where they were held, we managed to get some people released. There was someone who worked with our information, and negotiated with Ittihad to get people released. That person negotiated with Sayyaf, [and later] with Ahmadzai [an Ittihad official who later served as prime minister].

All the commanders, in all the groups, would completely and totally deny that their forces were holding people. But in those rare cases where we had complete information about the detained person, and we confronted them with it, they would release the people. But this only happened in a few cases.

H.K. said that most of those who were released were tortured by their captors and exhibited physical signs of it. He told the story of one man he worked to have released, from Ittihad’s forces, who said he had been forced to work “as a slave” on a commander’s farm in Paghman. (The section “The Attack on Afshar” below contains addition information about forced labor).

We documented all of this. I interviewed him after he was released. He had been tortured by Ittihad when he was captured, and beaten severely in their prison. There were fifty other people being held with him, he said, somewhere in Paghman. After a few weeks, they sent him to this farm, to work on the land, during the day and night.

Former officials in the Rabbani government also supplied information to Human Rights Watch about Wahdat and Ittihad abductions, noting that commanders in Jamiat, Harakat, Junbish, and Hezb-e Islami sometimes detained civilians as well, usually just for ransom.94 R.D., a former official in the interim government who was familiar with ongoing criminality by various factions, said that Anwar Dangar, a high-level commander in Shura-e Nazar, was “deeply involved in kidnapping schemes,” and that another Jamiat commander, Kasim Jangal Bagh, was regularly implicated in abduction, or hostage-taking, for ransom.95

The research project noted above uncovered some of these abduction cases. As the researcher H.K. explained:

Shura-e Nazar [meaning Jamiat forces under Massoud] arrested people as well. . . . In most cases, we were unable to do anything, but in three cases we managed to document what happened, and they released three people. They negotiated with the head of Amniat-e Melli [Afghan intelligence agency] at the time—Fahim [Mohammad Qasim Fahim]. To have them released they spoke with him.

Human Rights Watch also received testimony about abductions and killings of prisoners by Junbish forces in 1992 and 1993. Former Jamiat and Junbish officials confirmed to Human Rights Watch that Junbish forces regularly engaged in killings of prisoners in 1992 and 1993.96

Pillage and Looting

Human Rights Watch interviewed scores of journalists, health workers, aid workers, taxi drivers, civil servants, and soldiers who witnessed widespread pillage and looting by Jamiat, Junbish, Wahdat, Ittihad, Harakat, and Hezb-e Islami forces after the Najibullah government fell.

Merchants in southeast Kabul told Human Rights Watch about looting by Hezb-e Islami forces in the area around Bala Hissar (southeast Kabul) in April 1992.97 Embassies and diplomatic residencies were also reported to be targeted.98 The U.N. human rights rapporteur for Afghanistan received reports that apartment complexes built for government employees in Micrayon were a focus of looting.99 Journalists in Kabul covering the collapse of the old regime saw shops and houses being pillaged across the city.100 An Afghan journalist described what he saw in April 1992:

I saw with my own eyes Sayyaf’s troops and Massoud’s troops looting as they entered the city, breaking windows, stealing whatever they wanted. They were acting like animals, doing whatever they wanted.101

A BBC journalist described to Human Rights Watch looting he saw in May 1992:

I saw General Dostum’s Uzbek troops looting. . . . It was easy to recognize them. I knew who they were from their clothes and features. They were totally recognizable. I saw some of them carrying refrigerators on their backs, and other things like that, air conditioners. I remember especially some guys, Dostum’s Uzbeks, coming out of a compound somewhere. These were happy and contented guys, smiling. They had some refrigerators and other appliances like that, carrying them on their backs. And I saw these smiling guys put the goods in their trucks and drive away. The Presidential Palace was looted by government troops [Jamiat and Junbish]. The troops went in, and were taking out carpets and things like that.102

Human Rights Watch received accounts that Dostum’s highest military commanders in Kabul, including Majid Rouzi, were profiting from the looting by Junbish troops.103

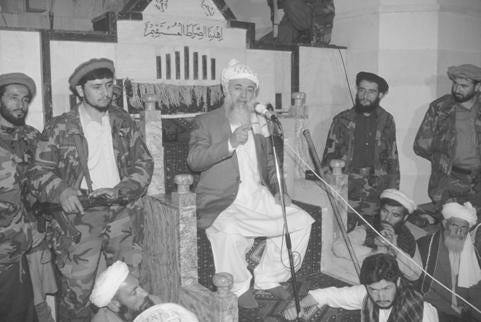

General Abdul Rashid Dostum, leader of the Junbish faction, August 11, 1992. Junbish forces were implicated in war crimes and other abuses in Kabul in the early 1990s. As of mid-2005, Dostum holds a senior post in the ministry of defense. © 2001 Reuters Limited

A former official in Shura-e Nazar told Human Rights Watch about looting by Jamiat troops working for Kasim Jangal Bagh, a mid-level Jamiat commander:

Kasim Jangal Bagh’s troops were responsible for the trouble that went on in [Micrayon and Wazir Akbar Khan—two neighborhoods in eastern Kabul]: looting, kidnapping, and raping of girls. . . . Kasim had a Ghund [military post]—it was independent I think. Bismullah Khan [a Shura-e Nazar commander] was his operational commander, but he may have reported directly to Massoud. . . . Massoud was giving him money [to pay his troops], but he was taking it for himself. I know—I know how these things work even now. He had cars, houses, but his gunmen were poor. So they were taking whatever they wanted from people. The soldiers were not paid, so they were robbing.104

A photojournalist who worked in Kabul through 1992 described seeing blocks of houses in west Kabul that were looted by Jamiat forces: “You’d notice blocks getting hit. Roof beams were torn out of the houses, electricity wires torn out, appliances, all the possessions.”105

When questioned in late May 1992 about the looting, Commander Muslim, a senior official in the Jamiat faction and ostensibly in the Afghan ministry of defense, told a journalist, “Every society has its thieves and robbers. Ours is no different. Yes, there’s chaos, yes there’s disorder. But it’s no worse than Los Angeles.”106 This was a reference to the large-scale riots and looting which had broken out in late April 1992 in Los Angeles, California, after a jury acquitted several police officers who had been videotaped beating an African-American motorist named Rodney King.

But Kabul was not Los Angeles. Many Kabul residents told Human Rights Watch that a culture of total impunity and chaos had come over Kabul in 1992, and that there was a general sense that the militia troops could do whatever they wanted at any time. Besides pillage and looting, there were regular incidents of killings and other violence.

A journalist with the British Broadcasting Corporation told Human Rights Watch about Junbish forces targeting civilians in April of 1992:

Junbish had been looting. . . . We filmed Junbish troops beating up this guy who had a bicycle. I guess they wanted to take the bicycle. I think that this was one of those rare cases where the presence of a camera literally stopped someone from being killed. They were clubbing him with Kalashnikovs, but when one of the troops saw us and pointed at us, they sent the guy on his way.

In another case, near the Intercontinental [Hotel], the camera led to problems. These Uzbek troops [Junbish] saw us, and they were acting up for the camera. They had this guy, this civilian, and they wanted to show off. They were making him stand a few meters away and they were shooting at his feet with their Kalashnikovs, making him dance. They were yelling, “Dance! Dance!” and shooting at his feet.107

Human Rights Watch documented several cases of killings by Junbish, Jamiat, and Harakat forces during 1992-1993. Former officials in Junbish and Jamiat admitted to Human Rights Watch that military forces in their former factions engaged in killings connected to pillage and looting.108

A Junbish official detailed some of the specific commanders involved in abuses:

Shir Arab, Ismail Diwaneh [“Ismail the Mad”], and Abdul Cherik109 from the beginning engaged in widespread looting of the market. Killing took place only over looting. In late 1371, early 1372 [January to May 1993], they looted the Porzeforooshi Bazaar. . . . Ismail Diwaneh was in Bala Hissar [on the southeast edge of Kabul]. He regularly killed and robbed Pashtuns from Paktia who were passing through on the way to Kabul.110

Another former Shura-e Nazar official, discussing general looting by Jamiat forces in 1992 and 1993, described a particularly bad commander, Rahim “Kung Fu,” who the official said was “a robber and killer and a thief, in a word, a criminal.”111 The official (who began crying as he was interviewed about Rahim) also told Human Rights Watch that Rahim was involved in killings of Hazara civilians, and children, during an operation against Wahdat forces posted in Timani neighborhood in 1992: “There were many rapes, the killing of many women and men. He was killing so many Hazaras. He killed children. I’m sorry, I cannot talk about it anymore.”112

In a later interview, he described how he heard Rahim boast about crimes committed during the Taimani operation:

He said he pochaghed Hazara [slaughtered, or cut their throats]. “We killed 300, 350 people,” he said. “I went to a house. I saw an infant. I put the bayonet in its mouth. It sucked on it like a tit, then I pushed it through.”113

One Kabul resident—a civil society organizer who often acted as a mediator between factions—told Human Rights Watch about an incident he witnessed in December 1992 when he said Junbish troops executed a Tajik man who had come to pay a ransom to release his brother, who he said was being held by a Junbish commander, Abdul Cherik:

One day [a woman came to me] asking for a favor. [I] had a few connections with some people in Junbish, she was asking me to help her: her brother’s car had been seized by some Junbish forces in December 1992. The car had been seized by Abdul Cherik—a commander with a checkpoint near the Kabul City Electrical Station (in east Kabul) in Chaman Waziri.

I went to his checkpoint. While I was sitting there, waiting to talk to him [Cherik], a young guy, about 18 or 19, entered with a bag full of money. It was a Panshiri guy—I could tell because of his accent, and he looked Tajik.

He asked Abdul Cherik to release his brother. He said: “This is the ransom you have asked for, for my brother,” and he opened up the bag. It was full of money. I don’t know how much.

Abdul Cherik looked at him, and then looked at his guards, and said, “Take him to his brother.” And his guards motioned him to come, and they took his arm, and went out the back door. So they went out.

I was waiting in that room. About three minutes later, I heard the sound of gunshots, about fifty meters away. It was a burst of automatic gunfire. And then a little later, the gunmen came back in. They had some rings and a watch in their hands, and they gave Abdul Cherik the rings and watch, on his desk. I had gone to that place to try to convince this commander to release this guy’s car, but after this happened, I immediately left the compound and walked away. I got outside and said to myself, “God save me,” and left there.

I asked this guard near the door to the compound, “Did you kill him, or just take his rings and watch?” The Junbish guy said, “What a question! Can a Panshiri remain alive when he is imprisoned by us or is in our control?”

It was unimaginable to me that they would kill someone like that. It was something ordinary for them. You couldn’t believe that they had killed him. It was like nothing had happened. The gunmen who were in the room there while I was waiting, they showed no reaction when those other men returned. It was an ordinary thing for them.114

A resident of Tiamani neighborhood of Kabul described a summary execution of a civilian by a Harakat soldier which he witnessed on a street in a neighborhood in north Kabul in September 1992:

I had [a store] in front of my house. I was selling some things there, one morning, sitting there. I saw this younger guy walk by—he had recently been married. Then I heard some shooting down the street. I looked down the street, and I saw that the guy who had passed was on the ground, and this other guy was over him—he held a pistol up to his head and shot him in the temple. The guy was dead. Some other people on the street walked a little forward [i.e., toward the body, to look], and then stopped.115

The man said he did not know the reason for the killing, and did not know the name of the gunman but recognized him as someone he had seen with the Harakat faction:

This gunman, he was a Harakat gunman, just walked by us, slowly. Like he could do whatever he wanted. We saw him clearly. We knew who he was—he was a Harakat man.116

A Kabul resident, a bus driver, told Human Rights Watch about being arrested, having his bus stolen, and almost being executed by Hezb-e Islami forces, in late 1992:

One time, I was driving, and I had got to the end of my route, all the [passengers] had gotten off and the bus was empty. . . . A man and a teenager asked me to stop, and I slowed down, to give them a ride. Suddenly, armed men surrounded the truck, and got in, and ordered me to turn around, and when I hesitated, they beat me. So I turned around, and they made me go on a small road, toward Gardez. . . . They took me to this checkpost there—they were Hekmatyar’s people. They made me show them how to use the car, the gears, and how to start it.

Then the commander said, “Take him to the mountain, and shoot him.” And they started to lead me away. On the path [up the mountain], an old man saw me, and said, “What’s the matter?” And I asked him to help me if he could. The troops pushed me forward. The old man went down to the commander [behind me] and told him not to kill me. [As an elder, the man presumably had additional influence.] The commander called up to the troops, “Just beat him.” And that’s what they did. They beat me very severely, and I lost consciousness. When I woke up, they had taken my watch, and I was alone. I went down the mountain on the other side, and got a cart to stop and take me into the city. I got a rickshaw driver to take me to my house, but I fainted on the way, and my family had to carry me into my house. . . . 117

Violations of International Humanitarian Law

As noted earlier in this report, the intentional targeting of civilians and civilian objects for attack is a violation of international humanitarian law that can amount to a war crime. In addition, article 3 common to the four Geneva Conventions, which is applicable in non-international armed conflicts, requires the humane treatment of civilians and detained combatants. Arbitrary deprivation of liberty, murder, torture, rape and other ill-treatment violate this requirement. International humanitarian law also prohibits “pillage,” which is defined as the forcible taking of private property from an enemy’s subjects, and other forms of theft.

Murder, adverse treatment and unlawful deprivation of liberty of civilians (as well as captured combatants), on the basis of their ethnicity or other distinction, violates common article 3 to the Geneva Conventions. Furthermore, widespread or systematic abductions, killings and “disappearances” that are part of an attack on a civilian population, such as an ethnic group, may amount to crimes against humanity.118

There is compelling evidence presented above that Ittihad and Wahdat forces abducted thousands of persons in the first year of the post-Najibullah era, as well as more in later years. The fact that so many persons arrested were never again seen by their families suggests that both the Ittihad and Wahdat factions killed thousands of these detainees. There is also compelling evidence that detainees who survived their detention were tortured or otherwise mistreated. The widespread murders, arbitrary deprivations of liberty, torture and other mistreatment committed by Ittihad and Wahdat forces may amount to war crimes and crimes against humanity.

Sayyaf, as the leader of Ittihad, is centrally implicated in the abuses described above, since he exercised ultimate control of Ittihad forces. Officials in the Rabbani government in 1992-1993, allied with Sayyaf, acknowledged to Human Rights Watch that Sayyaf, as the senior military commander of Ittihad forces, was in regular contact with his commanders, and that he had the power to release prisoners held by his subordinates, and in fact ordered such releases on several occasions, demonstrating his command over those commanders.119 Health workers in west Kabul told Human Rights Watch in 2003 of additional cases in which negotiators with the International Committee of the Red Cross spoke with Sayyaf to obtain the release of prisoners, further demonstrating his control over subordinate commanders.120 Human Rights Watch also spoke with an individual who negotiated with Sayyaf to obtain a relative’s release.121 And in June 1992, when interviewed by a journalist in Kabul about the abductions, Sayyaf did not deny that Ittihad forces were abducting Hazara civilians, but merely accused Wahdat of being an agent of the Iranian government.122

Further investigation will also be needed into other Ittihad commanders and their role in the abductions and abuses documented here. Investigations will need to focus in particular on the role of Ittihad commanders Shir Alam, Mullah Ezat, Zalmay Tofan, Abdul Manan, Dr. Abdullah, and Noor Aqa, who were named by several sources in this report as being implicated in abductions and holding of prisoners for forced labor.123 More detailed discussion of the potential legal responsibility of Sayyaf and his other commanders, for the abuses described here and elsewhere in this report, is set forth in section IV below.

As for Wahdat, its leader, Mazari, who was killed in 1995, was implicated in the abuses above. Mazari and his deputy, Karim Khalili (now the vice-president of Afghanistan), acknowledged taking Pashtun civilians as prisoners in interviews with Reuters and Associated Press.124 Mazari defended the practice by stating that Ittihad troops had first seized Hazaras.125 (Mazari later said that detained prisoners were kept in houses, given food and water, and not tortured.126)

Further investigation will be needed into the command-and-control structure of Wahdat and the culpability of the commanders who are still alive. More investigation is needed into Karim Khalili’s involvement in military decision-making and his control over Wahdat forces. Shafi Dawana and Nasir Dawana have been killed, but Wahid Turkmani, Mohsin Sultani, Tahir Tofan, Sedaqat Jahori, and Commander Bahrami are believed to be still alive, and should also be investigated for their role in the Wahdat abuses documented here. The potential legal responsibility of Wahdat commanders for the abuses documented here is further discussed in section IV below.

In addition to the abductions and killings, the widespread looting and pillage that took place in Kabul during the period discussed above should also be investigated. Troops or commanders from all the factions named above who were involved in pillage need to be thoroughly investigated.

Rape and Sexual Violence

Several health workers in Kabul who spoke with Human Rights Watch stated that rape and other forms of sexual violence were commonly committed against women who were abducted by Wahdat and Ittihad forces in 1992-1993, as well as generally during the hostilities around Kabul at the time.127 Human Rights Watch was unable to obtain direct accounts from victims of rape during this period, in large part due to deep reluctance among women and girls to grant interviews on the subject, or refusals by families of the victims to allow such interviews. But there is evidence of its occurrence. H.K., who worked on a documentation project into abductions discussed earlier in this report, told Human Rights Watch that researchers working on this issue in the early 1990’s knew of widespread abductions and rape of women in west Kabul, although he said that families were in most cases unwilling to give information about details:

It was impossible to document the rape or kidnapping of women in these cases. The families always denied cases where the women were kidnapped or raped, because of the dishonor and shame. The families would deny that their women were kidnapped, or refuse to discuss these cases; it is because Afghan families are very conservative. There would be lots of stories, lots of talk about how “other families” had had the women abducted. A set of people would tell us, “Look, that family over there, across the street, their women were kidnapped,” but when we went over to ask the family themselves, they would deny it, and say nothing had happened. This is how it always happened. Maybe they would admit it if a boy was abducted, for rape, but not the women.128

Human Rights Watch did receive accounts from several journalists and civil society organizers about cases of rape which they documented—specifically, cases of troops from Jamiat, Hezb-e Islami, and Wahdat breaking into houses and raping women.129 Human Rights Watch also received credible information from government sources about cases of rape by Jamiat, Wahdat, and Junbish forces.130 S.K., the health worker in west Kabul quoted earlier, said she treated numerous women who said they had been raped by militia forces in west Kabul in 1992-1993, and collected bodies of women in the streets who showed signs of having been raped.131

More investigation is needed to determine the scope of rape as a practice among the various troops in Kabul in the post-Najibullah period. Based on the available information, rape may have been a chronic problem in Kabul during the period and numerous commanders, including at the highest levels of each faction, appear to have failed to take appropriate steps to prevent further cases from occurring. In some cases, sub-commanders themselves may have been involved in rapes.132

B: October 1992-February 1993

Kabul suffered relatively less intense fighting after the August 1992 blitz on the city, but serious firefights and shelling rocked the city throughout the later part of the year.

In October, the leadership council set up under the Peshawar accords voted to extend Rabbani’s term for forty-five days, until December, on the grounds that the summer fighting had made the summoning of the council impossible. Jamiat forces repeatedly battled Wahdat in the west, near Kabul University, causing further casualties and damage. At the same time, there were increasing signs that Dostum’s Junbish faction was starting to negotiate with Hekmatyar’s Hezb-e Islami, despite the fact Hekmatyar had initially opposed Dostum, and used Dostum’s presence in Kabul (as a former communist government official) as a pretext for opposing Massoud.

In December 1992, Rabbani convened the council of representatives called for under the Peshawar Accords to choose the next government—or just reelect him as president.133 The council, however, was not representative of the different warring factions or the general Afghan population. Many of the invited members boycotted the vote, including representatives of Junbish, Wahdat and Hezb-e Islami. Rabbani was “reelected” by his supporters, allies and proxies in the meeting, and stated his intention to serve as president for another 18 months. Hekmatyar, however, refused to accept the outcome of the council, and vowed to dislodge Rabbani’s government, and Massoud’s forces, in the coming months. Wahdat rejected the new government as well, and soon made an official alliance with Hekmatyar. Junbish, for the most part, stayed on the sidelines.134

Burhanuddin Rabbani, seated,

the political leader of Jamiat-e Islami and President of Afghanistan after Mujaddidi.

© 1992

Robert Nickelsberg

January – February 1993: Conflict Continues