IV. Discrimination in Land Allocation and Access

Land Ownership and Distribution in Israel

Unlike most industrialized countries, which have widespread private land ownership and a free real estate market, in Israel the state controls 93 percent of the land.53 This land is owned either directly by the state or by quasi-governmental bodies that the state has authorized to develop the land, such as the Development Authority (DA)54 and the Jewish National Fund (JNF).55 A governmental body, the Israel Land Administration (ILA), administers all of this land.56 This gives the government an exceptionally decisive role in land allocation, land-use planning, and development.

According to Israel’s Basic Law, state land cannot be sold. The ILA usually leases land to individuals or institutions for periods of 49 or 98 years.57

The JNF has a specific mandate to develop land for and lease land only to Jews. Thus the 13 percent of land in Israel owned by the JNF is by definition off-limits to Palestinian Arab citizens,58 and when the ILA tenders leases for land owned by the JNF, it does so only to Jews—either Israeli citizens or Jews from the Diaspora.59 This arrangement makes the state directly complicit in overt discrimination against Arab citizens in land allocation and use, and Israeli NGOs are currently challenging this practice in Israel’s Supreme Court.60 The ILA’s Governing Council is comprised of 22 members—12 representing government ministries and 10 representing the JNF, giving the JNF a hugely influential role in Israeli land policies generally and the overall allocation of state lands.61

Notwithstanding the prohibition on sale of state land, the law allows the state to transfer directly owned state land to the JNF.62 The JNF acquired approximately 78 percent of its land holdings from the state between 1949 and 1953,63 much of it the land of Palestinian refugees from the 1948 war that the state confiscated as “absentee property.”64

While by law Arab citizens can lease land owned directly by the state and not transferred to the JNF, in practice numerous obstacles limit Arab citizens’ access to land, as described below. According to Adalah, a human rights organization representing the Arab minority in Israel, Arab citizens are blocked from leasing about 80 percent of the land controlled by the state.65

Bedouins’ lack of access to land occurs in a wider context affecting Israel’s Palestinian Arab population generally. Not only has the state confiscated pre-1948 Palestinian Arab lands, it has not allowed Arab citizens to establish new towns; nor has it approved adequate expansion of existing ones. Since 1948 the state has authorized the creation of about 1,000 Jewish communities, but not a single Arab community except for the seven government-planned townships and the nine new or newly recognized villages, which concentrate the Bedouin in limited areas in the Negev, and some similar towns in the Galilee.66 The state rarely grants expansion requests to Arab local authorities.67 While Arab citizens of Israel comprise roughly 20 percent of the country’s population, just 2.5 percent of the land of the state is under the jurisdiction of Arab local governments.68 In the northern Negev region, Bedouin municipalities have jurisdiction over 1.9 percent of the land, while Bedouin citizens comprise 25.2 percent of the population in that area.69

Discrimination in Land Jurisdiction

Israel has three types of local governments or local authorities: municipalities (governing individual cities), local councils (governing individual villages and towns larger than 2,000 people), and regional councils (governing a number of villages with fewer than 2,000 people and generally with jurisdiction of the land between the villages).

There are currently 53 regional councils in Israel with jurisdiction over 90 percent of Israel’s land but only 10 percent of the country’s population. Fifty of the regional councils contain Jewish localities and cover vast land areas. There are only three Arab regional councils and, unlike their Jewish counterparts, they do not have territorial contiguity:70 they control only land within the village boundaries of the communities under the council’s jurisdiction, while all the tracts of land between these villages belong to a neighboring Jewish regional council.71 For example, the Abu Basma Regional Council in the Negev, which includes the newly recognized or established Bedouin villages/townships, covers just 49,000 dunams.72 The Jewish Regional Council of Bnei Shimon in the Negev covers approximately half a million dunams, and the Ramat HaNegev Regional Council covers 4.3 million dunams.73

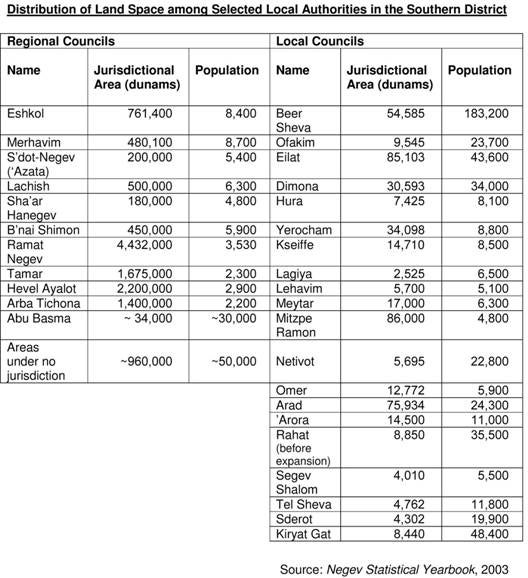

The following chart produced by Bimkom, an Israeli NGO promoting equality in planning, shows the stark difference between the land jurisdiction of Jewish and Bedouin local authorities in the Negev.

In the Negev today many Jewish localities are expanding and new ones are being created. The spokesperson of the Bnei Shimon Regional Council, in the northern Negev, told Human Rights Watch that many of the council's kibbutzim and moshavim (collective farming communities) are developing new neighborhoods and each is planning to add more than a hundred new homes.75 On the other hand, planning officials have not allocated sufficient land for the residential, infrastructural, and livelihood needs of the seven government-planned Bedouin townships in the Negev or the newly recognized villages.

Nili Baruch, an urban planner working with Bimkom, highlights the plight of Segev Shalom, one of the seven Bedouin townships:

Segev Shalom … has no developed industrial areas, even though the master plan for the town designates about 100 dunams for local industry. Most of the town’s area is designated for residential dwellings. Despite this, the town lacks residential land… Lack of space for residential use is characteristic of most of the Arab Bedouin towns.76

The government is actively pressuring Bedouin to relocate to these overcrowded and failing townships rather than allocating them additional land, recognizing the unrecognized villages, or allocating land for new rural communities.

Minister of Interior Roni Bar-On told Knesset members in December 2006, “We will not permit and not supply all the wishes of the [Bedouin] sector on the issue of rural construction… there is a problem of land and it is impossible that everyone will build for himself a house with a plot of land next to it.”77 In fact, the Negev contains the regional council with the largest land mass and smallest population in all of Israel. Ramat HaNegev Regional Council covers an area of 4.3 million dunams (over 250,000 acres) with a population of just 3,700 residents in 10 rural communities, one of them numbering just nine families.78 The Regional Council, actively trying to attract new residents, has hired a publicity company and started an advertising campaign. In the Ramat HaNegev Regional Council, moreover, the ILA has allocated large tracts of land to single families in order to create individual farms (see below).79

Ramat HaNegev Regional Council has ignored the Bedouin already living within its jurisdiction and has not offered to recognize villages or give them any place within the council’s exclusively Jewish communities.80

Individual Farms

There are currently 59 individual farms in the Negev, covering more than 81,000 dunams of land, which is greater than the total land mass that the state granted to the seven Bedouin townships housing around 85,000 people.81 The idea of individual farms was first proposed in 1997 by the Green Patrol and accepted by then National Infrastructure Minister Ariel Sharon and then Agriculture Minister Raphael Eitan, as a means of “preserving state land.”82 The newspaper Haaretz quoted Uzi Keren, the then-prime minister’s advisor on settlements, as saying of the individual farms, “this is about a top notch group of people, each one empowered to care for vast areas [of land] and act as a state appointed ‘policeman’ protecting these areas.”83

State agencies built many of these settlements without the zoning or planning documents necessary to acquire permits; the farms are thus illegal. The ILA did not publicly tender the farms nor allocate the large plots in a transparent way, based on clear criteria. Government agencies allocated public funds to establish the farms and connect them to infrastructure and utilities, even where the farms were built illegally and are not close to other inhabited communities. This stands in direct contradiction to the government’s assertion that they cannot provide services to Bedouin living in illegal housing and in dispersed locations. According to the ILA, “Israel provides its citizens with high quality public services in sanitation, health and education, and municipal services. These services can only be provided to those living in permanent [that is, legal] housing, and the fact that the Bedouin are dispersed over an extensive area prevents the state from offering these public services.”84

In its July 23, 2007 letter to Human Rights Watch, the Ministry of Interior confirmed that many of the approximately 60 existing individual farms in the Negev had not been built according to proper planning processes, but stated that this was based on environmental considerations:

The status of about 25 farms is properly arranged, concerning 20 additional farms, comprehensive action has been taken until now both by planning authorities and through a regulating procedure. However, the procedure of regulating the status of 15 more farms which are located in areas that have great importance to habitation, which has been going on for several years, has not been completed at this time.85

The policy of individual farms has been criticized by Israeli state planners,86 yet in September 2005 planning officials approved the “Wine Route” Plan, the most extensive plan for individual farms to date.87 Submitted by the ILA at the request of the Ministerial Committee for the Development of the Negev and the Galilee, the plan authorizes the construction of 30 individual farms, 20 of which already exist, within the Ramat HaNegev Regional Council’s jurisdiction. While state officials marketed the plan’s tourism features, their main goal appears to be to legalize retroactively existing individual farms that were built illegally, and to construct new ones.88 The plan is remarkably similar to an earlier plan for individual farms in the Negev that the ILA and Ramat HaNegev officials promoted as a means to help “prevent the takeover of Negev lands by the Bedouin” and to strengthen the Jewish population in the region.89 The Israel Union for Environmental Defense (Adam Teva Va’Din) had petitioned the Supreme Court protesting the previous plan, and the Supreme Court had canceled the plan in 2001.

Adalah and the Negev Coexistence Forum for Civil Equality (a joint Jewish-Bedouin organization commonly known as Dukium) petitioned the Supreme Court to overturn the Wine Route Plan, arguing that “the clear purpose of the plan is to secure exclusive use of these areas ... and to prevent their use by Arab citizens.”90 As part of the documentation supporting the allegation of discriminatory treatment, Adalah submitted a draft report prepared by the Prime Minister’s Office for the Negev-Galilee Ministerial Committees, entitled “Individual Settlements – Northern District and Southern District,” which states, “The reasons for initiating [individual settlements] are to preserve state lands… [as] solutions for demographic issues.”91

Prof. Oren Yiftachel, former head of the department of Geography and Environmental Development at Ben-Gurion University and a leading academic in his field, argued in an expert opinion supporting Adalah’s petition that the Wine Route Plan violates both regional and universal planning principles, the right to equality, and the principle of distributive justice (see below), and would result in the further deprivation of Bedouin in the Negev.92 In a separate article, Yiftachel wrote,

From the perspective of the Bedouin population, the proposal is part of a series of plans aimed at establishing dozens of Jewish communities in the Naqab, for the purpose of, among other aims, limiting Bedouin control of their ancestors’ land. For example, in July 2003, a government-approved plan to create 30 new Jewish settlements within the Green Line, 14 of which were to be built in the Naqab. This plan included the rhetoric of “creating a buffer between the Bedouin communities,” “preventing a Bedouin takeover,” and ensuring the security of the (Jewish) residents of the Naqab.93

As late as July 15, 2007, the government confirmed its intention to continue developing individual farms as part of its development policy in the Negev and Galilee. In a government resolution passed that day, aimed primarily at creating the unit in the Ministry of Housing and Construction to coordinate Bedouin affairs mentioned above, the government stated:

The Government has decided, in continuation of its Resolution dated 8.11.2002, which determined that the “individual settlements” is a means to implement the policy of the Government to develop the Negev and the Galilee, and in continuation of the Government’s dealing with the regulation of Bedouin residence in the Negev – to appoint an inter-Ministerial committee, headed by the General Director of the Prime Minister’s Office, which will act to regulate the status of the existing individual farms, and recommend to the Government a procedure for establishing additional individual farms in the Negev and the Galilee.94

The discrimination inherent in the promotion of individual farms is not lost on the Bedouin. “How can you explain that the state gives individual Jewish farmers thousands of dunams of land and the funding to fence in, close, and secure these areas, and stop others from entering?” one Bedouin activist said. He continued:

How do you explain that the authorities supply him with water and electricity yet he only has a few goats or cows? Meanwhile, we, the indigenous people of this area, who depend on herding, grazing, and agriculture as our main source of income, are not allowed to access our own land and practice our livelihoods.95

Human Rights Watch interviewed several Bedouin who claim that individual farms have been established on their ancestral land for which they have filed ownership claims. Sheikh Awde Abu Muamar told Human Rights Watch:

I registered my family’s land in 1972. I have all the documents. I was never told by the state that they had confiscated the land. I never received any kind of notice or order. But now the state has given a part of my land to Jewish families to create tourist sites. In one area the family planted an olive orchard, and another plot is used for overnight desert accommodations. They are not allowing us to live our traditional lifestyles, to farm and herd, but they are allowing others to make money off of our land.96

Mohamed Abu Solb, who served for 12 years in the Israeli army, told Human Rights Watch about the Jewish farm established on his family’s ancestral land:

In 1991, the state confiscated 10,000 dunams [2,500 acres] of our land, and the whole village [of Kornub] was destroyed. They claimed the confiscation was for military purposes, and they moved us [45 families] forcibly to other locations. We had registered our claims to our ancestral land in the 1972 [land claims] process, and we appealed to the Supreme Court against the confiscation, but we lost. Now at least part of our land, supposedly confiscated for military purposes, has been given to a Jewish farmer to establish a cactus farm. We have never seen the military or security forces using this land.97

Later Abu Solb took Human Rights Watch on a tour of his old village, pointing out many landmarks from his childhood, including areas where he had picnicked with his grandparents, and the site of his former home.

Ariel Dloomy, a Jewish activist with Dukium, explained the anger of the Bedouin towards the individual farms:

You can see them signposted along the main road, and it is usually one family living on dozens of dunams. Near one of the unrecognized villages of Abde, near the city of Mitzpe Ramon, there are several single-family ranches. One of the Bedouin families told me that they wanted to set up a little stall to sell pita with labane [traditional Bedouin cheese] to tourists for a little income. The day he started to set up his stall a Green Patrol inspector showed up and told him to demolish the stall. He is very very angry. He says, “All these individual ranches, set up for tourist purposes, tout signs offering an ‘authentic’ Bedouin experience. But when I want to market my own traditions, I am not allowed.”98

Salim Abu Alqian is from the unrecognized village of Um al-Hieran, where all the residents have received evacuation lawsuits and home demolition orders.99 He pointed out to Human Rights Watch four separate farms whose legal status is unknown that have sprung up around the village in the past 10 years. Villagers struggle to get enough fresh water from the one available water pipe, 4.5 kilometers from the village. The villagers look enviously at the individual farms nearby which, unlike them, are connected to the water and electricity grids.100

Ibrahim al-Atrash, a Bedouin shepherd who heads a committee of Bedouin herders and grazers demanding additional grazing land and permits for their animals, has faced increasing problems accessing enough grazing land for his several hundred head of sheep in the past couple of years, after the state reduced the amount of available grazing land. He spoke incredulously about two individual farms where the owners had no livestock:

There is a private farm near the area where we used to graze [in Yatir] that is subsidized by the government, and the owner has 5,000 dunams of land even though he only has three dogs. Last year I went to the land with my herds and tried to graze there on all the wild growth that he wasn’t using, but the owner wouldn’t let me. What need does he have of all that land? Another nearby private farm has thousands of dunams of land and no sheep or goats.101

Selection Committees

Selection committees determine who can gain admittance to all communities of fewer than 500 households.102 The selection is based on vague criteria including “appropriate to social life in a small community” for which applicants must provide “an opinion of a professional institute which will examine whether they fit the social life of the community.”103 Selection committees are made up of government and community representatives as well as a senior official in the Jewish Agency or the Zionist Organization, and have notoriously been used to exclude Arabs from living in rural Jewish communities.104 The state owns the land and the ILA allocates the land to the communities and leases plots to individual residents, on the basis of the committees’ recommendations.105 The ILA justifies this policy by saying that “social cohesion in small communities is important.”106

Ariel Dloomy described his own recent experience with a selection committee:

Last year, I bought a plot of land in a moshav not far from here. My wife and I had to appear before the selection committee, and there was a group of four men and one woman who began to chat with us, asking us where we grew up, what our parents do for a living, where we served in the army and what we could contribute to the community. I don’t believe there is any way a Bedouin could gain access to one of these agricultural communities. Everything is at the discretion of these selection committees. I don’t think they even have to explain why they reject people.107

The only time of which Human Rights Watch is aware that a Bedouin has successfully been granted admission to a rural Jewish community was in 2007, on appeal, after the selection committee initially rejected his application to live in Givaot Bar. In 2005 several Bedouin applied to live in Givaot Bar, a rural community founded on land claimed by Bedouin. One of the Bedouin applicants was rejected by the selection committee and submitted an appeal to the appeals committee, which ultimately overturned the decision of the selection committee and recommended that the Bedouin applicant be admitted to Givaot Bar.108 At the time of writing, the other applicants had still not received a response.

53 According to Israel's Basic Law: Israel Lands (1960), lands controlled by the state, the Development Authority and the Jewish National Fund are known as "Israel Lands." State lands can be divided between those belonging directly to the state—71 percent (15.3 million dunams or 3.825 million acres); those belonging to the Development Authority—16 percent (2.5 million dunams or 0.625 million acres); and those belonging to the Jewish National Fund—17 percent (2.6 million dunams or 0.65 acres). Adalah, “Land Rights and the Indigenous Palestinian Arab Citizens of Israel: Recent Cases in Law, Land and Planning,” Submitted to the Secretariat, UN Working Group on Indigenous Populations, 26 April 2004, p. 2. http://www.adalah.org/eng/intl04/unIndigpop.pdf (accessed November 16, 2007).

54 The Development Authority is a governmental agency established in 1952 (under the Transfer of Property law 5710-1950) to administer the lands of Palestinian refugees and make them available to the state for developing new settlements.

55 The Jewish National Fund was established in 1901 with the aim of acquiring land in Israel for the settlement of Jews. Under Israeli law the JNF enjoys a special status and is granted the privileges of a public authority. The 1961 Memorandum and Articles of Association of the JNF state that the ILA will administer all JNF-owned lands and that the objectives of the JNF remain to acquire property in Israel “for the purpose of settling Jews on such lands and properties." The JNF interprets the Memorandum as prohibiting the allocation of its lands to “non-Jews.” Information taken from Statement submitted by Adalah and Habitat International Coalition to the UN Commission on Human Rights at their Sixty-Second Session, 13 March – 21 April 2006, Item 6 of the Provisional Agenda. http://www.adalah.org/eng/intl06/un-i6-jnf.pdf (accessed November 20, 2007).

56 The Basic Law of 1960 established the ILA, an agency that manages 93 percent of Israel’s 19.5 million dunams (78 million acres). See ILA website, http://www.mmi.gov.il/Envelope/indexeng.asp?page=/static/eng/f_general.html (accessed May 21, 2007). The ILA operates under the authority of a government ministry, although which ministry has changed over time. As of May 7, 2006, the ILA is under the Construction and Housing Ministry (Israeli Cabinet Meeting Minutes, May 7, 2006, on file with Human Rights Watch). It was previously under the Ministry of Industry, Trade and Employment.

57 Israel's Basic Law: Israel Lands (1960). See also ILA website.

58 According to the JNF, it owns 13 percent of the land of Israel, about half of which is settled. The JNF claims that 70 percent of the Israeli population lives on land owned by the JNF. See Stuart Ain and Joshua Mitnick, “Land Sales To Arabs Could Force JNF Changes,” The Jewish Week, February 4, 2005, http://articles.findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_hb5092/is_200502/ai_n18522798 (accessed November 20, 2007).

59 While the Israeli Supreme Court held in its March 2000 decision on the Qa’dan case that the State could not "allocate State land to the Jewish Agency for the establishment of the Katzir community settlement on the basis of discrimination between Jews and non Jews", in practice that decision has not been implemented. The Qa'dan family is still not living in the community of Katzir, the focus of the case, and the State and the ILA have found ways to bypass the Supreme Court decision. In July 2007 the Knesset, in its first reading, approved a bill which calls for all lands under the JNF to be allocated to Jews only. The bill passed by a majority of 64 MKS to 16. The bill must pass two additional readings before it becomes law.

60 The human rights organization Adalah challenged this policy in a petition to the Israeli Supreme Court in October 2004. See H.C. 9205/04, Adalah et al. v. The Israel Land Administration et al. (case pending). According to media reports, Israel’s attorney general responded to the petition by saying that the ILA cannot discriminate against Palestinian citizens in the marketing and allocation of lands including those of the JNF, but the Supreme Court has not handed down a judgment on the case. See Yuval Yoaz and Amiram Barkat, “AG Mazuz Rules JNF Land Can Now be Sold to Arabs,” Ha'aretz , January 27, 2005. The Association for Civil Rights in Israel and the Arab Center for Alternative Planning also filed a petition to the Supreme Court in October 2004 challenging the ILA's discriminatory policy. See H.C. 9010/04, The Arab Center for Alternative Planning et al. v. The Israel Land Administration et al. (case pending). All information in this footnote taken from Adalah and Habitat International Coalition Statement to UN Commission.

61 See ILA website, http://www.mmi.gov.il/Envelope/indexeng.asp?page=/static/eng/f_general.html.

62 Adalah and Habitat International Coalition Statement to UN Commission.

63 Ibid. See also Arnon Golan, "The Acquisition of Arab Land by Jewish Settlements in the War of Independence," Catedra, vol. 63 (1992), pp. 122–54 [Hebrew]; Yifa'at Holtzman-Gazit, "The Use of Law as a Status Symbol: The Jewish National Fund Law – 1953 and the Struggle of the JNF to Establish its Position in the State, “ Iyoni Mishpat, vol. 26, pp. 601–44, July 2002 [Hebrew].

64Israel's 1950 Absentees’ Property Law, 5710- 1950 allowed the state to confiscate the land and homes of Palestinian refugees or internally displaced persons who were not present on their property as of 29 November 1947. Estimates vary as to how much land the state confiscated under this law. One estimate says that in 1954, more than one third of Israel's Jewish population lived on absentee property and nearly a third of the new immigrants (250,000 people) settled in urban areas abandoned by Arabs. Of 370 new Jewish settlements established between 1948 and 1953, 350 were on absentee property (Don Peretz, Israel and the Palestinian Arabs, Washington: Middle East Institute, 1958).

65 Adalah and Habitat International Coalition Statement to UN Commission.

66 Shmuel Groag and Shuli Hartman, “Planning Rights in Arab Communities in Israel: An Overview,” http://www.bimkom.org/dynContent/articles/PLANNING%20RIGHTS.pdf (accessed May 21, 2007).

67 Ibid.

68 Abu Ras, “Land Disputes in Israel,” Adalah Newsletter.

69 I. Peleg, “Jewish-Palestinian Relations in Israel: From Hegemony to Equality?: Palestinian-Israeli Relations,” International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society, vol. 17, no. 3, 2004 , pp. 415-437(23).

70 Two of the Arab regional councils are located in the Northern District—Bustan al-Marj and al-Batouf—and one is located in the Southern District – the recently-created Abu Basma Regional Council covering the municipal territory of the newly recognized Bedouin villages.

71 Groag and Hartman, “Planning Rights in Arab Communities in Israel.”

72 Abu Basma size taken from Selected Data section of the The Negev Development Authority website http://www.negev.co.il/ (accessed September 18, 2007).

73 Taken from websites of Bnei Shimon and Ramat HaNegev Regional Councils http://www.bns.org.il/site/he/eCity.asp?pi=1193 and http://ramat-negev.org.il/ [Hebrew] (accessed June 18, 2007).

74 Taken from websites of Bnei Shimon and Ramat HaNegev Regional Councils http://www.bns.org.il/site/he/eCity.asp?pi=1193 and http://ramat-negev.org.il/ [Hebrew] (accessed June 18, 2007).

75 Email to Human Rights Watch from Oshra Segal, Bnei Shimon Regional Council spokesperson, March 21, 2007.

76 Nili Baruch, “Spatial Inequality in the Allocation of Municipal Resources,” Adalah Newsletter, vol. 8, December 2004.

77 Protocol of December 4, 2006 meeting of the Knesset Internal Affairs and Environment Committee on Master plans of Bedouin settlements in the Negev and home demolitions (on file with Human Rights Watch), http://www.knesset.gov.il/protocols/data/html/pnim/2006-12-04.html [Hebrew] (accessed May 23, 2007).

78 Information taken from Ramat HaNegev Regional Councli website [Hebrew], http://www.ramat-negev.org.il/ (accessed May 21, 2007).

79 In Hebrew these individual farms are referred to as “Havot Bodedim.”

80 All the rural communities have strict acceptance policies and the Jewish Agency is involved in the applications for some of them. See section on Selection Committees, below.

81 The 59 individual farms were built between 1997 and February 2003. See Hana Hamdan, “Individual Settlement in the Naqab: The Exclusion of the Arab Minority,” Adalah Newsletter, vol. 10, February 2005. In a letter to Human Rights Watch dated July 23, 2007, the Ministry of Interior said there were “about 60 individual farms.”

82 Hamdan, “Individual Settlement in the Naqab,” Adalah Newsletter. The “Green Patrol” was created by then-Minister of Agriculture Ariel Sharon in 1977, and operates as an enforcement arm of the Ministry of Agriculture and the ILA. The Green Patrol is much reviled in the Bedouin community and referred to as an “environmental paramilitary unit.” The Green Patrol’s methods include pulling down Bedouin tents, confiscating livestock, and destroying crops planted without the appropriate permit, all in the name of protecting Israel’s green spaces and agricultural land. The State Comptroller severely criticized these plans for their attempts at circumventing standard planning procedures and developing the land in order to populate the farms exclusively with Jews. Ibid, quoting State Comptroller’s Annual Report for 2000, p. 602.

83 Zafrir Rinat, "Sharon is promoting establishment of 30 settlements in the Negev and Galilee," Haaretz, July 20, 2003 http://www.haaretz.co.il/hasite/pages/ShArtPE.jhtml?itemNo=319936&contrassID=2&subContrassID=1&sbSubContrassID=0 [Hebrew] (accessed September 9, 2007).

84 ILA paper on “Bedouin in the Negev” available on ILA website, http://www.mmi.gov.il/static/HanhalaPirsumim/Beduin_information.pdf (accessed May 21, 2007).

85 Letter to Human Rights Watch from the Ministry of Justice, July 23, 2007.

86 Planners involved in creating National Master Plan (TAMA 35) submitted an expert opinion to the National Board for Planning and Building in July 1999, stating that “TAMA 35's team views the policy of individual settlements as a great danger as it is a means of population dispersion and 'land seizure,' which are not regulated or controlled by the planning system.” The plan also contradicts the principles stated in other master plans including Master Plan for Israel 2020, adopted by the government in 1996, and the recently adopted National Master Plan 35, that clearly emphasizes the need for urban density and the preservation of open spaces as paramount planning values. See “Adalah Petitions Supreme Court to Cancel Wine Path Plan for Individual Settlements in the Naqab,” Adalah Newsletter, vol. 24, April 2006.

87 The plan was approved by the Sub-Committee on Planning Principles, under the auspices of the National Council for Planning and Building, according to Oren Yiftachel, “Inappropriate and Unjust: Planning for Private Farms in the Naqab,” Adalah Newsletter, vol. 24, April 2006.

88 “Adalah Petitions Supreme Court to Cancel Wine Path Plan for Individual Settlements in the Naqab,” Adalah Newsletter.

89 Yiftachel, “Inappropriate and Unjust,” Adalah Newsletter.

90 “Adalah Petitions Supreme Court to Cancel Wine Path Plan for Individual Settlements in the Naqab,” Adalah Newsletter. The case is H.C. 2817/06, Adalah et al. v. The National Council for Planning and Building et al. (case pending).

91 “Adalah Petitions Supreme Court to Cancel Wine Path Plan for Individual Settlements in the Naqab,” Adalah Newsletter.

92 Ibid. One of the planning principles Yiftachel refers to is the preservation of open spaces and natural landscape.

93 Yiftachel, “Inappropriate and Unjust: Planning for Private Farms in the Naqab,” Adalah Newsletter.

94 Information taken from letter to Human Rights Watch from the Ministry of Justice, July 23, 2007.

95 Human Rights Watch interview with Nuri al-Ukbi, Beer Sheva, April 3, 2006.

96 Human Rights Watch interview with Sheikh Awde Abu Muamar, Sahel al-Bakkar, April 6, 2006.

97 Human Rights Watch interview with Mohamed Abu Solb, shop across from Bir Mshash, March 30, 2006.

98 Human Rights Watch interview with Ariel Dloomy, Rahat, March 29, 2006.

99 The legal basis for the evacuation lawsuits is Article 17 of the 1969 Land Law.

100 Human Rights Watch interview with Salim Abu Alqian, Um Heiran, March 29, 2006.

101 Human Rights Watch interview with Ibrahim al Atrash, al Atrash, March 27, 2006.

102 Selection committees were established and governed through Resolutions of the ILA. The current Resolution governing the selection committees is Resolution no. 1064 of Israel Land Administration Council from July 27, 2005, which updated Resolution no. 1015 from August 1, 2004.

103 According to article 2 of Resolution no. 1064 as quoted in a letter to Human Rights Watch from the Ministry of Justice, July 23, 2007.

104 See “Israeli Arab couple petitions High Court after residency denied,” Haaretz, February 15, 2007. The make up of the selection committees is determined by Resolution 1064, and according to a letter sent to Human Rights Watch by the Ministry of Justice, “The selection committees in a communal town consists of a senior official in the Jewish Agency or the Zionist Organization, a senior official of the Ministry of Construction and Housing, a representative of the cooperative society, a representative of the regional council and a representative of the relevant settlement movement – in the relevant towns. In an agricultural town the composition of the selection committees will be determined by the society's institutions.”

105 “Living in Sophisticated Rakefet,” Haaretz, February 16, 2007.

106 Ibid.

107 Human Rights Watch interview with Ariel Dloomy, Rahat, March 29, 2006.

108 According to Resolution 1064, rejected applicants have a right to appeal to an appeals committee, headed by a public figure and consisting of representatives of the Register of Cooperative Societies and a representative of the ILA.