Summary

It was a lovely summer day in 2010 when Louiza was walking down Putin Avenue, the main street in Grozny, chatting to a friend. The two young women wore light blouses with sleeves to the elbow and skirts a little below the knee. Their hair was loose. Suddenly a car with no license plates stopped next to them. They saw the side window roll down and a gun barrel stare Louiza in the face.

Louiza was paralyzed with fear and saw nothing but the gun barrel’s black hole. When she heard the shots, she told Human Rights Watch that she thought, “This is death.” Something hit Louiza in the chest and she was thrown against the wall of a building. Her chest burned with pain, but gradually the pain lessened, and she saw a strange green splattering on the wall and a big green stain expanding on her blouse. A similar ugly blotch stained her friend’s skirt. Then Louiza understood the shooter was using not bullets, but pellets filled with paint.

Unknown men dressed like law enforcement officials had shot Louiza and her friend with paintball guns for not observing a compulsory Islamic dress code, in other words, for wearing clothes deemed to be revealing and not keeping their hair covered. Dozens more women in Chechnya were subjected to similar attacks in summer 2010.

The paintball attacks came several years into a quasi-official, though extra-legal “virtue campaign” in Chechnya. As part of this campaign, despite the absence of any legal basis for doing so, local authorities prohibit women from working in the public sector if they do not wear headscarves. Education authorities similarly require female students to wear headscarves in schools and universities. Gradually, throughout 2009 and 2010, the authorities broadened their enforcement of this de facto “headscarf rule” to other public places, including entertainment venues, cinemas, and even outdoor areas. Though such measures do not have any basis in the written laws applicable in the Chechen Republic, they are strictly enforced. They are also publicly supported by the leader of the Chechen Republic, Ramzan Kadyrov, who was appointed directly by the Kremlin.

Indeed, Kadyrov has made the “virtue campaign” for women a policy priority since 2006. He made numerous public statements, including on Chechen television, which appears to be under his control, regarding the need for women to adhere to “modesty laws,” by, among other things, wearing a headscarf and following men’s orders. He has described women as men’s “property” and publicly condoned honor killings. Other Chechen officials have echoed his views in their own public remarks. Several dozen women interviewed by Human Rights Watch in Chechnya indicated that they found the virtue campaign deeply offensive but could not protest it openly, fearing for their own security as well as that of their relatives.

Human Rights Watch has criticized the governments of Germany, France, and Turkey for violating religious freedom by banning religious symbols in schools and denying Muslim women the right to choose to wear headscarves in schools and universities. By the same token, however, we support the right of women and girls to choose not to wear religious or traditional dress.

Chechen officials generally justify the enforcement of an Islamic dress code for women on traditional grounds. However, it is contrary to Russian law, discriminatory, and is leading to abuses. While Human Rights Watch takes no position on Sharia-inspired norms or cultural dress practices, we oppose all laws or policies that impinge on basic rights, including government-mandated public dress codes.

The enforcement of a compulsory Islamic dress code on women in Chechnya violates their rights to private life, personal autonomy, freedom of expression, and freedom of religion, thought, and conscience. It is also a form of gender-based discrimination prohibited under international treaties to which Russia is a party, including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, and the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms. This policy is also in breach of Russia’s Constitution, which guarantees freedom of conscience, freedom of religion, and gender equality.

This report describes violence and threats against women in Chechnya to intimidate them into adhering to a compulsory Islamic dress code. The documented attacks and incidents of harassment took place from June through September 2010, when the virtue campaign in the republic intensified. During that time, dozens of women were subjected to attacks by men, including law enforcement officials, in the center of Grozny, for not wearing a headscarf or for dressing in a manner which these men deemed insufficiently modest. While pressure on women seemed to become less aggressive after September the dress requirement remains a live issue and continues to be backed by high-level officials, including Ramzan Kadyrov.

Several victims and witnesses of particularly vicious attacks in June told Human Rights Watch how uncovered women were pelted with paintball guns in the center of Grozny, with law enforcement and security officials being among the perpetrators. They also saw threatening leaflets in the center of Grozny explaining to women that the paintball shootings were a preventive measure aimed at making them cover their hair. If they failed to cooperate, the leaflets said, more “persuasive” means would be used. All of the women interviewed by Human Rights Watch unanimously interpreted this as a threat to use real weapons instead of paintball guns.

In a televised interview in July 2010, Kadyrov expressed unambiguous approval of the paintball attacks by professing his readiness to "give an award to" the men engaged in these activities and arguing that the targeted women deserved this treatment. Then, at the start of the Ramadan holiday in mid-August 2010, groups of men in traditional Islamic dress claiming to represent the republic's Islamic High Council (muftiat)[1] started approaching women in the center of Grozny, publicly shaming them for violating Islamic modesty laws and handing out brochures with detailed descriptions of appropriate Islamic dress for females. They instructed women to wear headscarves and to have their skirts well below the knees and sleeves well below the elbow. The purported envoys from the Islamic High Council were soon joined by aggressive young men who pulled on the women's sleeves, skirts, and hair; touched the bare skin on their arms; accused them of being dressed like harlots; and made other humiliating remarks and gestures. In interviews with Human Rights Watch, dozens of victims and witnesses described a pattern of harassment that continued throughout Ramadan, and that in some cases involved law enforcement authorities as enforcers of the women’s dress code.

Although Russia’s Prosecutor General’s Office has directed Chechen authorities to look into the paintball attacks, the federal authorities have not otherwise taken any steps to put an end to the Chechen leadership’s enforcement of a compulsory Islamic dress code in Chechnya. They have also failed to indicate in any public way that describing women as property and justifying violence against women is unacceptable. This failure even to address the actions of the Chechnya leadership or to hold them to account in any way for policies that violate human rights law amounts to the Kremlin’s tolerance of and acquiescence in Chechnya’s unlawful gender policies.

The Russian authorities should put an end to the enforcement of a compulsory Islamic dress code by the Chechen authorities and other violations of women’s rights in Chechnya. They should publicly condemn the enforcement of a compulsory Islamic dress code on Chechen women, and hold the perpetrators of specific attacks against women to account. Russia should also promptly ensure access to the region for international monitors, including the UN Special Rapporteurs on violence against women and on freedom of religion.

Russia’s international partners should pay close attention to the dramatically deteriorating situation for women’s rights in Chechnya and advance the detailed recommendations for the Russian government contained in this report in multilateral forums and in their bilateral dialogues with the Russian government. They should urge the Russian authorities to take a resolute stand against the enforcement of a compulsory Islamic dress code by the Chechen authorities and other violations of women’s rights in Chechnya; to ensure that women and girls in Chechnya can fully exercise their rights to private life, freedom of religion, and freedom of expression by being able to choose whether to adhere to an Islamic dress code; and to ensure access to the region for international monitors.

Methodology

This report is based on interviews conducted by Human Rights Watch in Grozny, Chechnya’s capital, in September 2010 and follow-up research through December 2010. In the course of the research in Grozny, we interviewed 35 individuals, mostly female, who had experienced or witnessed attacks and/or harassment aimed at forcing Chechen women to adhere to a compulsory Islamic dress code. We also spoke with six NGO activists and conducted additional interviews in Moscow or by phone from Moscow. Human Rights Watch identified victims and witnesses by approaching individual women, both randomly and through our local NGO contacts, who were then able to refer Human Rights Watch to other victims or witnesses. All interviews were conducted in Russian by a Human Rights Watch researcher who is a native speaker of Russian.

Human Rights Watch also examined official documents and media accounts on the issue. Transcripts of statements by President Kadyrov and were translated by a native speaker of Chechen.

All of those interviewed for this report were deeply concerned about possible repercussions for themselves and their families for speaking with Human Rights Watch and asked us not to use their real names. To protect these individuals from possible repercussions, we chose to assign pseudonyms to victims and witnesses quoted in the report who gave us their names (the pseudonyms were chosen randomly from a comprehensive list of Chechen names at a specialized website http://www.n-a-m-e-s.info/dat_imya/chechenu.htm).

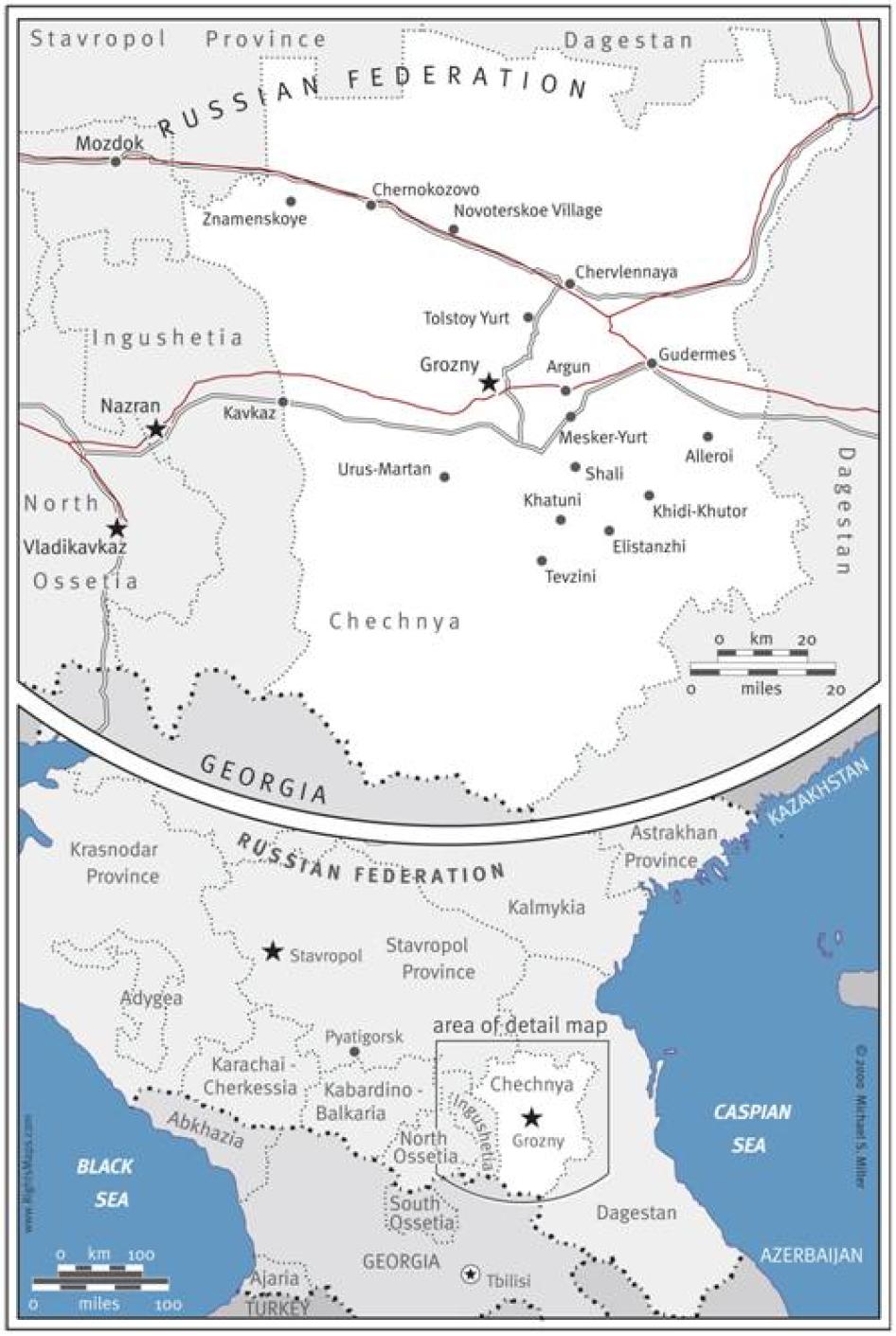

Map of Chechnya

I. Background

The Rise and Role of Ramzan Kadyrov in Chechnya

The “virtue campaign” for women in Chechnya has been a key project for Chechnya’s leader, Ramzan Kadyrov, since he consolidated power in Chechnya. Kadyrov’s trajectory to power began when Russia’s large-scale military operations to bring Chechnya back into Russian federal rule ended in 2000. At that time the federal government gradually began to hand responsibility for governing the republic and carrying out counterinsurgency operations to pro- Kremlin Chechen leaders. This process, which involved handing over the license to violence from federal forces to pro-Kremlin Chechen forces, became known among analysts as “Chechenization.”[2]

Seeking a figure who could gain the trust of important strata within Chechen society, the Kremlin chose Akhmat Kadyrov, the former mufti, or leading religious authority, of Chechnya, who then became president of Chechnya in October 2003 elections organized by the Kremlin.[3] As a security policy, “Chechenization” aimed to place most responsibility for law and order and counterinsurgency operations on republican security structures. An important factor in this process was Akhmat Kadyrov’s personal security service, known as the Presidential Security Service, which was headed by his son, Ramzan. The Presidential Security Service, informally referred to as “Kadyrovtsy,” soon became the most important indigenous force in Chechnya.[4]

In May 2004 a bomb attack killed Akhmat Kadyrov, and Russian authorities organized a presidential election to replace their chosen partner. Twenty-seven-year-old Ramzan, who was already commander of the “Kadyrovtsy,” inherited his father’s influence but could not yet run for president as the Chechen constitution establishes 30 as the minimum age for presidential candidates. Alu Alkhanov, a candidate chosen by the Kremlin, was elected president, and Ramzan Kadyrov was appointed first vice-prime minister in charge of security.[5]

Over the course of 2005, Kadyrov was able to push his allies into key positions in the Ministry of Internal Affairs for Chechnya, and thus gain direct influence over the ministry as a whole.[6] In 2005 and into early 2006, Ramzan Kadyrov’s political power grew substantially. In spring 2006, he became prime minister of Chechnya. In February 2007 his ascent to power was completed through Alu Alkhanov’s apparently forced resignation as president. Taking the place of Alkhanov, Ramzan Kadyrov was sworn in as president of the Chechen Republic in April 2007, following his nomination to the post by Russia’s then-President Vladimir Putin.[7]

In 2008, Kadyrov firmly established himself as the only real power figure in Chechnya.[8] Since that time, there have been persistent, credible allegations that law enforcement and security agencies under Kadyrov’s full de facto control have been involved in abductions, enforced disappearances, acts of torture, extrajudicial executions, and collective punishment practices, mostly against alleged insurgents, their relatives, and suspected collaborators.[9] Numerous experts on the North Caucasus, including those in international organizations, have described Kadyrov’s rule over Chechnya as a “personality cult” regime and stressed that Kadyrov’s orders have become, in essence, the only law in the republic.[10] In 2010, Kadyrov’s title was changed from “president” to “head” of the Chechen Republic[11] but this change was only nominal and has had had no impact on the scope of this authority.

Headscarves and the Evolution of the “Campaign for Female Virtue” under Kadyrov’s Rule

Kadyrov’s first attempt to exercise moral policing of women was carried out in 2006, while he was still prime minister, shortly before his promotion to the presidency of the republic. Early that year, Kadyrov stated that the use of cell phones had a negative impact on female morality supposedly by providing women with an opportunity to flirt with men and arrange dates, after which several young women had their cell phones forcibly taken away from them by law enforcement officials.[12] Around the same time, Kadyrov made his first public calls regarding the necessity for Chechen women to cover their hair.[13]

After his appointment by the Kremlin as president of the Chechen Republic in 2007, Kadyrov began to more actively convey to the public the role he believes females should play in Chechen society and the social and moral rules local women needed to abide by. He openly asserted that women were inferior and should be subjugated to men, equating women with male property. He also openly and uncritically acknowledged polygamy[14] and honor killings as part of Chechen tradition,[15] even though both are unambiguously prohibited by Russian law.[16] For example, in an interview with a leading Russian mainstream daily, Komsomolskaya Pravda, Kadyrov stated:

I have the right to criticize my wife. She doesn’t [have the right to criticize me]. With us [in Chechen society], a wife is a housewife. A woman should know her place. A woman should give her love to us [men]… She would be [man’s] property. And the man is the owner. Here, if a woman does not behave properly, her husband, father, and brother are responsible. According to our tradition, if a woman fools around, her family members kill her… That’s how it happens, a brother kills his sister or a husband kills his wife… As a president, I cannot allow for them to kill. So, let women not wear shorts…[17]

Kadyrov further reflected on Chechen customs on maintaining women’s honor when commenting on the murder of seven women whose bodies were found by the roadside in Chechnya at the end of November 2008. Kadyrov told the BBC:

Here in Chechnya if a woman is running around, if a man is running around with her, then the both of them are killed. According to the information available, there was a woman who was “working” with the killed [women] – she wanted to take them away from the [Chechen] Republic, [she] was in the process of obtaining travel passports for them in order to sell them to brothels [abroad]. It’s being said that the women’s relatives [found out and] killed them… I’m simply talking about [our] customs. Ask anyone, even the youngest boy, “What are you gonna do if your sister starts running around?” Anyone will tell you, “I’ll kill her!”[18]

Several high-level Chechen officials, including the local ombudsman, Nurdi Nukhazhiev, echoed Kadyrov in their assessment of the situation without suggesting that such “traditions” should be changed. “Unfortunately, we have some women who started to forget about the behavioral code of highland women. And their relatives–the men who consider themselves offended [by the behavior of those women]–do lynch them sometimes,” stated Nukhazhiev.[19]

Unwritten rules on headscarves: from public institutions to public space

Issues surrounding modest dress and head coverings for women have been at the core of Kadyrov’s efforts to strengthen “female virtue” in Chechnya. In 2007, he launched a special program for the revival of moral values among Chechen youth, which placed special emphasis on modesty laws for women.[20]

By the autumn of 2007, Kadyrov publicly announced, including on television, that all women working for state institutions had to wear headscarves and expected to see his wishes carried out immediately.[21]

In November 2007 Kadyrov elaborated on the issue of female dress for Grozny and Vainakh republican television channels in November 2007, singling out the Ministry of Culture for its failure to enforce headscarf rules among its own staff:

Today, I’m worried about how our young women dress. Our brides sometimes present themselves to their mother-in-law, to the groom’s relatives–do excuse me–almost naked and with their head uncovered. They show up in the streets in mini-skirts and with their hair loose. The mentality of our people does not allow for these things. I’d really want to see Chechen young women look like true Muslims, who observe the customs and traditions of their people. Here the key role should belong to the republican Ministry of Culture. However, just look how the ministry’s own [female] staff-members dress! We have already issued a directive that all bridal parlors exhibit [our] ethnic [female] dresses. The Committee on Youth Affairs is planning to recruit prominent designers to create one single uniform for youth educational institutions.[22]

By the end of 2007, women employed in the public sector, including television anchors, female officials, teachers, and even staff-members of the ombudsman’s office diligently wore headscarves to work.[23]

In 2007 local education authorities introduced uniforms, which included headscarves for female students, in Chechen schools and universities. Those who tried to resist the headscarf requirement were simply denied entry to their respective offices or academic institutions, despite the absence of any legal basis for the new requirement.[24]

In response to an inquiry by journalists, the deputy head of Chechen State University, Mokhdan Kerimov, vehemently defended the headscarf requirement for female students, but not by reference to any legal basis: “Our girls have been covered up by headscarves since the very day on which the Chechen nation came into being. [We] demand that [they] they wear headscarves. [We] demand for the Chechen State University to have a Chechen face.”[25]

The headscarf requirement for access to the university’s premises extends to non-Chechen and non-Muslim females. The Memorial Human Rights Center reported that in February 2008, security guards denied entry into the university’s compound to one of the organization’s non-Chechen researchers, demanding that she cover her hair. She tried to explain that she was not Muslim, but university officials informed her that it did not matter as the headscarf requirement concerned all females. After approximately one hour of arguing with university officials, the Memorial researcher convinced the deputy head of the university to allow her to enter, in light of her long history of cooperation with the university. However, she was told clearly that no such exceptions would be made for her in the future. The deputy head of the university also refused to show her any written instructions regarding the entry ban for women without headscarves but made a reference to Chechnya being “an Islamic republic with its own national mentality.”[26]

The author of this report had a similar experience when she tried to enter the Chechen State University without a headscarf in May 2008. The security guards refused to let her discuss the matter with the university’s leadership. She told them that she was neither Chechen nor Muslim, and that the ban was not based in law. The security guards insisted that in order to enter the building “all women had to wear headscarves, no matter what.”[27]

Two female staff members of Chechen State University, who asked that their identities be withheld due to possible reprisals, described to Human Rights Watch how young male security guards routinely inspected their clothing for “propriety” and “broke into the classrooms,” including in the middle of a lecture, to check if all women had their hair covered. They described the experience as “deeply humiliating” for them as well as for other female staff at the university.[28]

In a December 2008 interview with the BBC, the deputy head of the university strongly denied that the headscarf requirement for access to the Chechen State University premises contradicted the Russian constitution, saying that “no constitutional breach could be found, as elements of the uniform are accepted in numerous educational institutions in the country and [more broadly]in the world.”[29]

The chair of the Rule of Law and State Building Committee of the Chechen Parliament, Mompash Machuev, also reassured the press that all laws of the Chechen Republic “are in strict compliance with the federal ones. All normative acts already adopted or to be adopted by the Parliament of the Chechen Republic are checked for compliance with federal legislation.”[30] This statement may in fact be accurate, as the headscarf policy, along with many other rules enforced in Chechnya under Kadyrov, are not provided for in law or even tabled before the parliament.[31]

Gradually, throughout 2009 and 2010, the “headscarf rule” spread to public places in general, including entertainment venues, cinemas, and even outdoor areas.[32]

As this report went to press, Human Rights Watch became aware of a written instruction regarding headscarves issued by the Chechen government. In a January 25, 2011 letter to all republican and local government agencies, the Administration for the Head and Government of the Chechen Republic underscored the need to “strictly enforce” an instruction issued by Kadyrov regarding the dress code for civil servants. The dress code consists of: “for male staff, a suit and tie, on Fridays—traditional Muslim dress. For women staff: the appropriate headdress, dress and skirt—below the knees, and three-quarter sleeves.”[33]

Although state authorities may enjoy discretion to establish guidelines on office attire for civil servants, the limits to personal autonomy imposed by such guidelines must be necessary, proportionate and nondiscriminatory. The dress code set out in the January 25, 2011 letter applies to both men and women. However the requirement on all women to wear headscarves and exact types of skirts and shirts based on specific gendered and religious grounds is more onerous and stringent than the requirement imposed on men, and is discriminatory. The obligation on men on Fridays to wear a particular type of religious dress is also incompatible with protections of freedom of religion and expression.

Kadyrov appears very sensitive to public criticism of the headscarf policy. A leading researcher for the Memorial Human Rights Center in Chechnya and a close friend and colleague of Human Rights Watch, Natalia Estemirova – who was abducted near her home in Grozny and brazenly murdered in July 2009[34]– had been vocally protesting the Chechen authorities’ policy to enforce a compulsory Islamic dress code for women since 2007.[35] In early 2008, Estemirova gave a long television interview in which she criticized the headscarf policy, insisting that forcing Chechen women to wear headscarves was wrong, unlawful, and constituted a blatant violation of the right to privacy. The interview, which was part of a program about the Islamic revival in Chechnya, was shown on REN-TV, a television channel that broadcasts to many regions in Russia, on March 30, 2008. The next day, Ramzan Kadyrov personally dismissed Estemirova from the Grozny City Human Rights Council,[36] raising his voice to her, making derisive remarks to try to shame her for not adhering to modesty laws, and threatening her with repercussions for her unyielding criticism.[37]

International Response

In June 2010 the enforcement of unwritten rules for women regarding headscarves and other violations of women’s rights in Chechnya came to the attention of the Council of Europe. In a report presented to the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE), the rapporteur on human rights violations in the Northern Caucasus for the PACE Committee for Legal Affairs and Human Rights, Dick Marty, critically assessed the human rights situation in the region, based on his trip to Chechnya, Ingushetia, and Dagestan in spring 2010. With regard to women’s rights, Marty wrote:

Where the relationship between religious practices and the rights of women is concerned, we heard reports of degrading treatment suffered by women following the introduction of rules directly dictated by the regime run by the current president of the Chechen Republic. Women caught without headscarves in the street have been publicly humiliated on local television. The Chechen courts now apply rules drawn from Sharia law, in contravention of Russian law. As a result, for example, a woman who is widowed may have any children over 12 years of age and her property taken away from her by her deceased husband's family. The prevailing attitudes towards women cannot be justified by putting them down to tradition and culture. This is an intolerable situation, often exacerbated by the behavior and statements of the local authorities… [38]

International, European, and Domestic Legal Standards

The enforcement of a compulsory Islamic dress code on women in Chechnya violates their rights to private life, personal autonomy, freedom of expression and to freedom of religion, thought, and conscience. It is also a form of gender-based discrimination prohibited under international law.

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) guarantees people's right to freedom of religion, as reflected in article 18.2, which states that "no one shall be subject to coercion which would impair his [or her] freedom to have or to adopt a religion or belief of his [or her] choice."[39]

Asma Jahangir, former United Nations Special Rapporteur on freedom of religion or belief, and her predecessor, Abdelfattah Amor, have both criticized rules that require the wearing of religious dress in public. In particular, Amor has urged that dress should not be the subject of political regulation. Jahangir has said that the "use of coercive methods and sanctions applied to individuals who do not wish to wear religious dress or a specific symbol seen as sanctioned by religion" indicates "legislative and administrative actions which typically are incompatible with international human rights law."[40]

Article 8 of the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (ECHR), to which Russia is a party, obliges the state to protect the right to privacy and personal autonomy, which includes the right to make decisions over one’s personal attire. Articles 9 and 10 of the Convention protect religious freedom and freedom of expression, and successive European Court of Human Rights rulings have confirmed that such freedoms are protected even in cases where activities “offend, shock, or disturb the state or any sector of the population.”[41] While Article 9 does allow governments some leeway in regulating religious dress in the interest of preserving public order, in order to justify such policies, a government must be able to demonstrate a pressing public need and provide for them in law. Article 9 does not bestow the right on governments to force any individual to wear a particular form of clothing in adherence to a particular religious code. Chechnya’s policy requiring adherence to Islamic dress for women, has no legal basis, yet is maintained by the republic’s government with apparent silent complicity from the federal government, and violates Russia’s obligations as a party to the ECHR.[42]

As a party to the Convention on the Elimination of All forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), Russia has an obligation “to refrain from engaging any act or practice of discrimination against women and to ensure that public authorities and institutions shall act in conformity with this obligation”; and to take all appropriate measures with a view “to achieving the elimination of prejudices and customary and all other practices which are based on …stereotyped roles for men and women.”[43] Russia also has specific positive obligations to put an end to violence against women. Adopting a strict dress code targeted at women, and enforcing it in an arbitrary and abusive manner, is a clear violation of Russia’s obligations in this regard. It also violates Russia’s obligations on equality with respect to Articles 2 and 26 of the ICCPR[44] and Article 14 of the ECHR.[45]

Imposing Islamic dress on women is not only inconsistent with Russia's international human rights obligations but is also contrary to Russia’s constitution, by which Chechnya is bound as a subject of the Russian Federation and which guarantees freedom of conscience in Article 28: “All are guaranteed to freedom of conscience, freedom of religious practice, including the right to practice any religion individually or together with others, or abstain from religious belief altogether, and the freedom to keep and distribute religious and other convictions and act accordance with them.”[46]

Finally, Article 11 of the Constitution of the Chechen Republic, in full compliance with Russia’s Basic Law, maintains that “the Chechen Republic is a secular state. No religion can be made a state religion or a mandatory one.”[47]

II. Enforcing Islamic Dress Code in Chechnya through Attacks and Harassment of Women

In summer 2010 Human Rights Watch received reliable reports of attacks on and harassment of women in public places who did not dress according to the locally applied Islamic code. Coercion to force Chechen women to adhere to a compulsory Islamic dress code has manifested itself in a number of ways, including public shaming, threats, and even physical violence.

The incidents documented below took place from June through September 2010 in Grozny, Chechnya’s capital.

June 2010: Paintball Attacks

In June 2010, Human Rights Watch received credible reports of individuals, including law enforcement agents, shooting pellets from paintball guns at women who were not wearing headscarves in the center of Grozny. According to Caucasian Knot, a prominent Russian Internet news outlet covering the situation in the Caucasus, at least one of the victims was hospitalized as a result.[48]

In September 2010, Human Rights Watch conducted interviews in Chechnya with two victims and three witnesses of paintball attacks.[49]

A 25-year-old woman described her experience of being targeted in a paintball attack by men who, by their dress, appeared to be local security officials. She told a Human Rights Watch researcher:

I was walking down Putin Avenue [the main thoroughfare in Grozny] with a friend. It was a hot day in June—I don’t remember the exact date. We were dressed modestly but not covered up—no headscarves, sleeves a little above the elbow, skirts a little below the knee. Suddenly a car with no license plates stops next to us. The side window rolls down and there is this gun barrel. I was paralyzed with fear and saw nothing but this barrel, this horrid black hole. I thought the gun was real and when I heard the shots I thought, “This is death.” I felt something hitting me in the chest and was sort of thrown against the wall of a building. The sting was awful, as if my breasts were being pierced with a red-hot needle, but I wasn’t fainting or anything and suddenly noticed some strange green splattering on the wall and this huge green stain was also expanding on my blouse. So, I understood it was paint.

My friend’s skirt was also covered in it. She was hit on her legs and stumbled to the ground. I was still trying to get myself together when a man’s face appeared in the [car] window. He was laughing, then leaning out and pointing to us. He was dressed in this black uniform that Kadyrov’s security people wear. And the men in the car with him—they also leaned out to snicker at us—also had those uniforms on… It’s only at home that I could examine the bruise and it was so huge and ugly. Since then, I don’t dare leave home without a headscarf.[50]

Another victim, a woman of 29, told a Human Rights Watch researcher that on June 6 she was walking down the same street in the afternoon with two other young women, all of them without headscarves, when two cars drove up to them. Bearded men in military-style black uniforms, who looked like law enforcement officials, shot at them from the cars’ windows with pink and blue paint, screaming, “Cover your hair, harlots!” Male passersby applauded the attackers and yelled, “Serves you right for having no shame!”[51]

The victims hid in a neighboring shop, from which they called a taxi. Later, they saw through the taxi window that “the avenue was literally splattered with paint—pink, green, yellow, and blue.” The woman also told Human Rights Watch that she personally knows 12 women who were subjected to paintball attacks that week in June. She also indicated that she wanted to make an official complaint to the prosecutor’s office but her family and her work supervisor had talked her out of it, cautioning that such steps might result in serious repercussions for her and for her employer.[52]

Another female resident of Grozny, aged 40, told Human Rights Watch that she witnessed two similar attacks against young girls without headscarves in the center of Grozny. Judging by the number of paintball attack stories that she personally heard from friends and relatives, she believed that “from 50 to 60” women fell victim to such attacks, although Human Rights Watch could not independently confirm this estimate. She also reported that after several days of frequent attacks, many of her friends who did not wear headscarves had put them on and ordered their daughters to do the same.[53]

Concerns about personal security prompted the women we spoke with to wear headscarves. Threatening leaflets soon appeared in the streets of the Chechen capital, explaining to women that the paintball shootings were simply a preventive measure aimed at making them cover their hair – if they failed to cooperate, more “persuasive” means would be used. All of the women interviewed by Human Rights Watch unanimously interpreted this as a threat to use real weapons instead of paintball guns.[54]

The leaflet, a copy of which Human Rights Watch examined, read as follows (bold and capital letters are reprinted as in the original document):

Dear Sisters!

We want to remind you that, in accordance with the rules and customs of Islam, every Chechen woman is OBLIGED TO WEAR A HEADSCARF.

Are you not disgusted when you hear the indecent “compliments” and proposals that are addressed to you because you have dressed so provocatively and have not covered your head? THINK ABOUT IT!!!

Today we have sprayed you with paint, but this is only a WARNING!!! DON’T COMPEL US TO RESORT TO MORE PERSUASIVE MEASURES!!!”

Numerous sources, including women’s NGOs,[55] reported to Human Rights Watch that the punitive paintball campaign ended in mid-June, likely due to the fact that its objective was achieved: for at least several weeks afterwards, women generally refrained from entering the city center without headscarves.[56]

Commenting on the issue on the television station Grozny on July 3, 2010, Kadyrov expressed unambiguous approval of the lawless paintball attacks, claiming he was ready to "give an award" to the men who carried them out. He also stated that the targeted women deserved this treatment and that they should be so ashamed as to "disappear from the face of the earth."[57] This comment amounts to open encouragement, at the highest level of the government of Chechnya, of the physical assault and public humiliation of women.

There is no evidence that federal authorities responded to Kadyrov’s statement in any way.

Harassment and Additional Pressure during Ramadan and Beyond

Several weeks after the attacks subsided, some women cautiously began to appear in Grozny’s center without headscarves.[58] Around the start of Ramadan in mid-August, however, another punitive campaign began, targeting women not wearing headscarves and/or wearing clothes deemed too revealing.

In the first days of Ramadan, groups of men in traditional Islamic dress (consisting of loose pants and a tunic), claiming to represent the republic's Islamic High Council, started approaching women in the center of Grozny, publicly shaming them for violating Islamic modesty laws and handing out brochures with detailed description of appropriate Islamic dress for females. They instructed women to wear headscarves and to have their skirts well below the knee and sleeves well below the elbow. Chechen females were admonished:

Dear sister in Islam! Today Chechnya wants to uphold decency and morality. Your dress, dear sister, should be a demonstration of your purity and your morality, but mainly of your faith. Your clothes and your morality preserve your honor and that of your relatives and parents![59]

The authors of the brochure, a copy of which was obtained by Human Rights Watch, also urged men to take charge of women’s appearance:

It has to be admitted, unfortunately, that a terrible picture is to be seen in the streets. We are not accusing women. The main fault belongs to the men. A woman won't lose her sense of reason if her husband doesn’t [lose his]. Men, we need your help. Of all that we see, the worst is the way some women dress. But what is even more terrible is that the men folk allow their sisters, wives, and daughters to dress in this way and don't consider that it is wrong to do so.[60]

The purported envoys from the Islamic High Council were soon joined in their efforts by aggressive young men who pulled on women's sleeves, skirts, and hair, touched the bare skin on their arms, accused them of being dressed like harlots, and made other humiliating remarks and gestures. This harassment persisted throughout the entire month of Ramadan, until mid-September. Dozens of victims and witnesses spoke about such incidents and confirmed this distinct pattern in their conversations with a Human Rights Watch researcher.[61]

A 27-year-old woman who was visiting relatives in Chechnya told Human Rights Watch that in August 2010 she was walking on the main street of Grozny, carrying her newborn baby and holding her three-year-old-son’s hand when she was surrounded by four threatening men in Islamic dress. The weather was very hot, so she was wearing a knee-length skirt and a light T-shirt with short sleeves. Her head was covered with a kerchief folded over several times instead of a large scarf, leaving most of her hair visible. The men started pointing at her bare arms and shouting that she was behaving indecently and shamefully. It took a while for the woman to react:

At first, I was nearly at a loss for words. It was so disgusting… But then I just pulled myself together, and here I was yelling at them that I was married with two children and had never in my whole life done anything shameful, so they had no right to make such disgraceful comments. I told them I had had a husband and a brother and would ring them up right away to come and sort things out. When I reached for my cell phone, the men sort of retreated. One of them, who acted like a boss, said, “Don’t call anyone. Don't make a fuss. We have our orders from above. We've got to do this, do you understand?”

And you know what? I did understand. I understood clearly that you had to play by their rules or they wouldn’t let you have a life. And as I did not want to play by their rules, I got my tickets back to Moscow the next day and left. But you see, I had a place to go to. And those women whose home is here—they have no place to flee. For them there is no escape and they can only obey and keep silent.[62]

In two cases reported to Human Rights Watch that occurred during Ramadan, law enforcement personnel harassed women for not adhering to the Islamic dress code. In the first case, a group of three police officers walked into a small grocery shop in Grozny and noticed that the woman behind the counter was not wearing a headscarf. They started screaming at her that she was a disgrace, and demanded the telephone number of her boss. They called the boss, demanded that she appear immediately, and instructed her to make sure her entire staff was “properly dressed” lest she face “serious problems.”[63]

In another case documented by Human Rights Watch, a 44-year-old woman, “Kheda” (not the woman’s real name), described a humiliating attack that she witnessed in the center of Grozny at the end of August. Kheda was walking down Putin Avenue when she saw a group of seven to eight armed, bearded men in black uniforms drag a young woman towards a large garbage bin. The young woman, “Fatima” (not her real name), who had long, uncovered hair and wore a long but clingy dress, cried hysterically and tried to resist her attackers, flailing her arms and legs. The attackers were snickering and screaming that she was a slut and belonged in a garbage dump. Shocked by the scene, Kheda intervened on behalf of the young woman, overcoming her own fear. She grabbed Fatima, who was being pulled by her arms and hair, and yelled, “What are you doing? Let her go!” The men tried to shake Kheda off, but she would not let go and continued to shout even more loudly. Ultimately, they dropped Fatima and left.[64]

After the incident, Fatima, who is 19 years of age, told Kheda how it had started. Fatima said that she was walking on her own when she passed two cars parked along the sidewalk. From the windows of the cars, some young men in black uniform who she understood to be “Kadyrov’s men” started shouting after her, as if trying to make her acquaintance. The men then leapt out of the cars and rushed after her. According to Kheda, Fatima said the men surrounded her and starting talking obscenely. When she told them to leave her alone, they became more aggressive, saying that if she had been decently dressed and wearing a headscarf, no one would be pestering her. They told her she was dressed in such a way as to attract men's attention and be a “temptation” to them. Then they tried to throw her into a garbage bin, and might have succeeded had Kheda not intervened.[65]

Several incidents that occurred after Ramadan indicate that the pressure to adhere to a strict Islamic code continued. For example, in mid-October 2010, a staff member from a local NGO working in the House of Print—a large building in the center of Grozny that houses numerous Chechen media outlets and organizations—called Human Rights Watch to report that on October 8, Ministry of Information officials had summoned all tenants to a meeting. During the meeting, women were specifically instructed that that they would not be allowed into the building unless their hair was fully covered with headscarves.[66]

Several dozen women interviewed by Human Rights Watch in Chechnya told Human Rights Watch that they found the virtue campaign deeply offensive but could not protest openly, fearing for their own security as well as that of their relatives.[67] One of them summed up the problem to a Human Rights Watch researcher in the following way:

It’s so humiliating, but you have no other option—you have to put on the headscarf. If, say, they hit you, and that’s not unlikely, then your brothers won’t be able to leave it at that. They’ll have to take action against the aggressors, who will just kill them. You dress according to their rules not so much out of fear for yourself, but to protect your family.[68]

Response by Russia’s Federal Authorities and Reaction of Chechen Officials

Federal authorities lodged a formal inquiry with the Chechen Ministry of Internal Affairs about the paintball attacks. However the response was to deny that such attacks had occurred and no further action was taken. Beyond this inquiry there is no publicly available evidence that Russia’s federal authorities have taken any measures to respond to the unlawful polices regarding forced Islamic dress for women in Chechnya.

To his credit, on September 22, 2010, the Ombudsman of the Russian Federation, Vladimir Lukin, wrote to Russia’s Deputy Prosecutor General, Ivan Sydoruk, demanding that he look into the reports of paintball attacks against women in Chechnya.[69] The Ombudsman of Chechnya, Nurdi Nukhazhiev, denied that there had been any such attacks on women and stressed that his office had not received any complaints on the matter.[70] Earlier, Ilias Matsiev, head of the Grozny mayor’s press service, also denied any knowledge of these attacks.[71]

However, in October 2010, the Federal Deputy Prosecutor General informed Lukin that in 2010 the Chechen law enforcement authorities had in fact received “three communications from citizens about women without traditional Islamic headdress being shot at by unknown men from paintball guns.”[72] However no criminal case was launched because a preliminary inquiry found the complaints lacked criminal content. According to Sydoruk, the Chechen Prosecutor’s Office found the inquiry conducted by the Chechen Ministry of Internal Affairs to be incomplete and requested that the Minister look into the matter and discipline the servicemen responsible.[73]

Sydoruk also assured Lukin that the Chechen prosecutor’s office had examined a video of one of the attacks posted to the Internet[74] and passed it on to the investigative authorities, instructing them to look into the possibility of opening a criminal investigation into hooliganism (Article 213 of Russia’s Criminal Code).[75] At this writing, Human Rights Watch is not aware of any criminal prosecutions for the attacks or disciplinary action against officials for failing to conduct a thorough inquiry into reports about the attacks.

Neither the Kremlin nor any other federal political body has responded publicly to the virtue campaign or its implications for women’s rights in Chechnya. No federal body has publicly indicated to Kadyrov that his comments on the issue are inappropriate, inconsistent with Russian law, and encourage lawless practices. For example, there was no response to Kadyrov’s statement, described above, describing women as public property and justifying killings of women based on their supposedly provocative behavior.

Nor was there a response to Kadyrov’s public condoning of the paintball attacks. As noted above, Kadyrov justified the attacks several times, including in an October 24, 2010, Newsweek interview, several weeks after Lukin’s letter. At that time Kadyrov insisted that the attacks were not carried out on his order but rather by individuals who “want to blacken my [his] policies.” But he also explained: “Many women walk around Grozny today without covering themselves with scarves! If we were beating or shooting at them, they would not be doing that.” In the same interview, responding to a question regarding appropriate dress for Chechen women, Kadyrov unequivocally stated, “I always remind women what Allah said—it is simple for a woman to get into paradise: she has to cover herself, her hair and her arms, wear a long skirt, fast, pray, and be faithful to her husband. My dream is that all Chechen women should wear headscarves.”[76]

III. Recommendations

To the Government of the Russian Federation

- Publicly condemn the compulsory Islamic dress code for women in Chechnya and the role played by Ramzan Kadyrov and other Chechen officials in promoting, justifying, and enforcing the dress code.

- Put an end to the enforcement of compulsory Islamic dress code by the Chechen authorities and other violations of women’s rights in Chechnya by:

- Instructing Chechnya’s leader to issue public statements making plain that wearing a headscarf and adhering to an Islamic dress code in public is the personal choice of every woman in Chechnya;

- Working with the Chechen authorities on developing a series of public service announcements clarifying women’s rights to privacy and personal autonomy, freedom of expression, and freedom of religion including the right to choose whether to adhere to an Islamic dress code.

- Ensure access to the region for international monitors, including the UN Special Rapporteurs on violence against women and on freedom of religion, and ensure that such monitors are free to travel, make inquiries, and otherwise conduct their visits in full accordance with the terms and conditions set forth in their UN-approved terms of reference.

- Ensure meaningful accountability for violations of the rights of women in Chechnya, including those perpetrated by security services, military, law enforcement and other officials.

- Bring perpetrators of attacks against women to justice; investigations and prosecutions should respect due process and other fair trial rights and be conducted transparently, with the public regularly informed about the progress of cases.

- Provide effective security guarantees to victims and witnesses of attacks against women.

- Ensure effective implementation of rulings on Chechnya cases by the European Court of Human Rights–a major step towards eliminating the climate of impunity for human rights abuses in the region.

- Foster a favorable climate for journalists and human rights defenders to carry out work safely in the region. This can be done by holding accountable perpetrators of attacks and threats on journalists and human rights defenders in the region and by ceasing official efforts to intimidate and harass them.

To the State Duma of the Russian Federation

- The State Duma Committee on the Problems of Families, Women, and Children should hold hearings on the situation of women’s rights in Chechnya, including the policy of enforcing a compulsory Islamic dress code.

- The State Duma Committee for Constitutional Legislation and State Building should issue conclusions on the Chechen leadership’s policy of enforcing a compulsory Islamic dress code for women in context of the freedom of conscience guaranteed by Russia’s constitution and the secular nature of the Russian state.

To the United Nations

- The Special Rapporteurs on violence against women and on freedom of religion should renew their pending requests for invitations to visit Russia, including Chechnya, in the near future. In the meantime, they should request information, in the form of urgent appeals and communications, from the Russian government about enforcement of the compulsory Islamic dress code and other violations of the rights of women and freedom of conscience in Chechnya.

To Russia’s International Partners

Governments, in particular those of European Union member states and the United States, should advance the recommendations contained in this report in multilateral forums and in their bilateral dialogues with the Russian government. They should call on the Russian government to:

- Put an end to the enforcement of a compulsory Islamic dress code by the Chechen authorities and other violations of women’s rights in Chechnya.

- Allow unhindered access to the North Caucasus region for international monitors, including the UN Special Rapporteurs on violence against women and on freedom of religion.

- Ensure meaningful accountability for violations of the rights of women in Chechnya.

- Fully implement rulings handed down by the European Court of Human Rights regarding violations in Chechnya, an essential step toward ending impunity and improving the human rights situation in the region, including the situation of women.

- Ensure the unhindered work of Russian and foreign journalists and human rights defenders in Chechnya and in the broader North Caucasus region.

To the Council of Europe

- The Parliamentary Assembly should include the situation of women in Chechnya in the agenda of its ongoing monitoring of human rights in Russia, with a view to holding, as soon as possible, a public debate on the situation.

- The Secretary General should urge the Russian Prosecutor’s Office to end impunity in Chechnya by fully investigating recent and past human rights abuses, including those of the rights of women. The Secretary General should insist that these investigations fully comply with the standards for investigations into alleged human rights violations developed in the case law of the European Court of Human Rights.

- The Committee of Ministers should closely monitor Russia’s implementation of the European Court’s rulings on Chechnya cases and ensure a sustained, vigorous dialogue with the Russian government on the necessity of full and effective implementation of those rulings.

Acknowledgments

This report is dedicated to the memory of our friend and colleague, Natasha Estemirova, who encouraged HRW to carry out this research and with whom we would have been honored to work on it if not for her murder in July 2009.

This report was researched and written by Tanya Lokshina, researcher in the Europe and Central Asia Division of Human Rights Watch. Essential support was provided by Erica Lally, associate, and Daniel Sheron and Anais Gulko, interns in the Europe and Central Asia Division.

The report was edited by Rachel Denber, acting director of the Europe and Central Asia Division, and Joe Saunders, deputy program director at Human Rights Watch. Aisling Reidy, senior legal advisor, reviewed the report and provided legal analysis. Gauri Van Gulik, women’s rights researcher and advocate, also reviewed the report. Veronika Szente Goldston, Europe and Central Asia Division advocacy director, provided assistance with the recommendations. Anna Lopriore, Grace Choi, and Fitzroy Hepkins provided production support.

The report was translated into Russian by Igor Gerbich. The map of Chechnya was designed by Michael S. Miller. The cover photo was taken by Diana Markosian.

Human Rights Watch expresses its sincere gratitude to all who shared their stories with us. We hope that this report will contribute to ending human rights abuses in the region and will bring those responsible for violence against women and other abuses to justice.

Human Rights Watch gratefully acknowledges the generous support of the individual donors and foundations that have made our work possible. Among them are KENSHINKAI and two other anonymous donors from Japan.

Appendix: Questions and Answers on Restrictions on Religious Dress and Symbols in Europe

December 2010

A growing number of European countries have passed or are contemplating restrictions on religious dress in public places. The impetus for these restrictions is the debate in Europe about the wearing of Muslim veils. The debate reflects tensions in increasingly pluralist societies struggling with integration, national identity and security.

While many of the proposed and adopted measures are purportedly neutral—banning all religious dress or symbols or face coverings on paper —the public and political debate has focused on the different veils worn by Muslim women: the hijab, or headscarf, which covers the hair; the niqab, which covers the face and neck, leaving the eyes visible; and the burqa, a full-face and body covering.

There are no complete and reliable figures on how many women in these countries wear full-face veils, but it is clear that they constitute a very small minority. Estimates in France range from 700 to 2000 women, about 150-200 in Denmark, while in Belgium the figure may be around 300-400.

In France, civil servants, including teachers, are prohibited by law from displaying religious symbols, and students may not attend public schools if they display any kind of “ostentatious” religious symbol, including the headscarf, the Sikh turban, and the Jewish headcovering (kippah). Authorities have said that this ban would also apply to ‘large’ Christian crosses but the ban has not been applied to ‘normal’ sized crucifixes worn around the neck. In Germany, eight out of sixteen Länder (states) have passed laws prohibiting teachers in public schools from wearing visible religious clothing and symbols, with parliamentary debates and explanatory documents making it clear that the Muslim headscarf was the principal target. Two of these Länder impose the same restriction more widely on some or all other civil servants.

In September 2010 the French parliament adopted a law prohibiting the concealment of one’s face in public, with the declared intention to prevent the wearing of Muslim veils that cover the face in public places. The law, which was approved by the French Constitutional Council in October 2010, makes it a crime to coerce women to wear such veils, punishable by a year in prison and a 30,000 Euro fine. Once the law enters into full effect, in the spring of 2011, women who violate the law will be subject to a fine of up to 150 Euros ($209) and/or compelled to attend a “citizenship” course.

A law containing similar restrictions was approved by the lower chamber of the Belgian parliament in April, and remains pending approval by the Senate. The Spanish senate adopted a nonbinding resolution in June 2010 calling on Spain to outlaw in public places clothing or accessories that completely cover the face, saying that a majority in Spain considers the full Muslim veil “discriminatory, harmful, and contrary to the dignity of women and real and effective equality between men and women.” The Spanish government has said it would include a ban in a future reform of Spain’s law on religious freedom. A plan to ban veils was included in the October 2010 coalition government agreement in the Netherlands. Comparable nationwide measures have also been proposed in a variety of other countries, including Italy, the United Kingdom and Denmark, while a number of municipalities in Belgium, Spain, and Italy already have, or are considering implementing, local bans in place.

The debate raises challenging questions about the interplay between different sets of fundamental rights, in particular rights associated with freedom of religion and the rights of women. It also poses questions about the appropriate role of the state in matters of religion and traditional practices, including how, when and where the state can legitimately restrict the wearing of religious dress and the display of religious symbols.

Q: What does international human rights law say about religious dress and symbols?

A: Human rights law guarantees the right to freedom of religion, including the right to manifest one’s religious beliefs through worship, observance, practice and teaching in private and in public. Human rights law requires states to guarantee the right to a private life, which includes the right to autonomy, for example the freedom to choose what to wear, in private and in public. States must ensure the right to equality or non-discrimination, particularly that there should be no discrimination on the grounds of religion or sex. And finally, states are bound to protect the rights of religious minorities within their borders.

The United Nations Human Rights Committee has clarified that the concept of worship includes the display of symbols, and that observance and practice can include the wearing of distinctive clothing or head coverings.

Like the vast majority of rights, neither religious freedom nor the right to autonomy is an absolute right under human rights law. Governments can limit these rights, but only when they can demonstrate convincingly that restrictions are necessary to protect public safety, public order, health, or morals, or the fundamental rights and freedoms of others. This is a high threshold for a government to justify.

The governments attempting to ban the wearing of full-face veils have not demonstrated that the wearing of veils poses such a significant threat under any of the permitted grounds of restrictions, to the extent that would justify outright bans. In addition, under international law any restriction on religious freedom must be nondiscriminatory and proportionate. While proposed and existing bans are crafted in neutral terms—prohibiting concealment of the face in public—the declared aim and logic behind these bans is to counter the wearing of full-face veils, and these bans are likely to have a disproportionate impact on Muslim women. In other words, these bans are discriminatory in practice.

Whereas some of the purported reasons for the bans on veils – the need to ascertain a person's identity, the need to protect women from oppression – may be legitimate aims, the response of a complete and public ban, including the punishment of the women who wear the veil, is disproportionate. Less restrictive measures are possible to meet these aims and some of these are discussed below.

Human Rights Watch is aware of arguments that full-face and body covering veils do not constitute a religious practice sanctioned or prescribed by Islam but is instead a cultural practice with roots in geographically limited areas. It is not our role to enter into a theological debate. The crucial point is that it is not up to the state to define or interpret the meaning of religious symbols; what is decisive is that the individual considers it to be a manifestation of his or her religious belief. The right to freedom of religion and belief protects religious minorities but also dissenters within religious majorities and atheists. Under international human rights law, the state should neither deny nor impose particular religious beliefs or particular manifestations of religious beliefs.

Q: What do international human rights bodies say?

A: International human rights bodies have criticized restrictions on headscarves and veils. The Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights Thomas Hammarberg called general bans on the burqa and niqab “an ill-advised invasion of individual privacy,” stressing also the importance of the right to freely manifest one’s religion and the right to non-discrimination. The secretary general of the Council of Europe and its Parliamentary Assembly also oppose such bans. The UN Committee on the Rights of the Child expressed its concern that the ban on religious symbols in schools may neglect the basic principle of the best interests of the child and the right to education, and called on France to ensure that no child was excluded or marginalized from the school system as a result of its laws.

The European Court of Human Rights gives governments considerable latitude when assessing whether restrictions on religious dress for public servants and in public buildings are compatible with human rights law. In a series of cases, the Court has upheld restrictions on students and teachers wearing headscarves and turbans in schools and universities. It has also upheld a newly-imposed requirement in France that a Sikh remove his turban for his driver’s license photograph. (The Court has yet to hear any cases involving restrictions on the Jewish kippah under the French law.)

Human Rights Watch disagrees with the Court’s interpretation in these cases. Human Rights Watch believes the Court failed to give proper weight to the need for states to have strong justifications for these restrictions, the impact these restrictions have on the lives of the people concerned (including Sikh men and boys in France), and the discriminatory impact of bans that predominantly affect women and girls wearing headscarves. In many of these cases the Court has ruled without requiring the government to produce a justification for its restrictions.

It is also notable that in a February 2010 case against Turkey, the European Court of Human Rights ruled that general restrictions on religious dress in public areas applied against members of a minority group violated their right to freedom of religion. That suggests it would find a general public ban on face-covering veils to be incompatible with human rights law.

Q: What is Human Rights Watch’s position on state interference in religious dress and symbols?

A: Human Rights Watch takes no position on whether the wearing of the headscarf or face covering veils is desirable. We oppose both policies of forced veiling and blanket bans on the wearing of religious dress. Insofar as religious freedom is involved, we defend this right in the same spirit we defend freedom of expression – we uphold the right to express opinions which some deem contrary to the principles of human dignity, tolerance and respect, and which may deeply offend, because of the fundamental importance of freedom of religion and expression in democratic societies.

We also oppose laws prohibiting civil servants, including teachers, from wearing religious symbols at work, unless it has been shown that those symbols have a direct impact on their ability to perform their jobs. Authorities can prohibit teachers in public schools from actively proselytizing their religion to their students, but schools can address this on an individual basis through internal disciplinary procedures. Allowing individual employees of the state to manifest their beliefs by wearing a religious symbol does not constitute endorsement by the state nor does it undermine state neutrality or the ability of the state employee to uphold that duty. On the contrary, it demonstrates respect for religious diversity.

It may be reasonable for the state to prohibit the wearing of full-face veils in certain jobs, when concealment of the face is shown to interfere with essential occupational requirements. For example, it may be legitimate to require civil servants in contact with the public and teachers in public schools to show their faces at all times. But such restrictions should be tailored to where showing one's face is an essential requirement of the job. And such restrictions could not be legitimately applied to the wearing of religious symbols that do not cover the face such as a headscarf, kippah, crucifix or turban.

Q: What about countries where women are forced to wear the headscarf, niqab or burqa?

A: Human Rights Watch is opposed to policies of forced wearing of veils or other religious clothes, such as those in Aceh (Indonesia), Saudi Arabia, Iran, parts of Somalia, Gaza, the Russian republic of Chechnya, and Afghanistan under the Taliban, as a violation of women’s rights to personal autonomy, as well as their freedom of religion, conscience and belief. We recognize and have documented that practices and policies justified on religious grounds sometimes have a negative impact on women’s rights, and that women and girls are subjected to violence and oppression in the name of religion.

Q: When governments ban or mandate religious dress, aren’t they simply reflecting the social consensus in their country?

A: Human Rights Watch rejects the argument that state-imposed rules on veiling in parts of the Muslim world and bans on religious dress in Europe are simply reflections of societal norms in those countries. Human rights principles protect all individuals and give special protection to members of minorities, often against laws that reflect oppressive societal norms. Furthermore many of the laws, both those in Europe attempting to ban certain religious clothing and those in other parts of the world requiring it, are relatively new.

Nor do we find compelling related arguments that policies of forced veiling are expressions of a shared societal concept of decency analogous to laws prohibiting public nudity. It is important to note that decency laws prohibiting public nudity are virtually universal, are not associated with and do not lead to other limitations on rights, and are not the subject of significant dissent. In contrast, forced veiling —and in particular forced wearing of the niqab and the burqa—are associated with serious human rights violations. Moreover, the purpose, meaning and nature of veils vary widely among communities and nations, and are hotly contested issues within Muslim communities.

At the same time, restrictions on wearing the veil in public life are as much a violation of the rights of women as is the forced wearing of the veil. Muslim women, like all women, should have the right to dress as they choose, and to make decisions about their lives and how to express their faith, identity and morals.

Q: But isn’t the veil a symbol of women’s subjugation?

A: One of the principal arguments used in favor of bans is that they help liberate women who are coerced into veiling. For many, full veiling is a powerful symbol of the oppression and subjugation of Muslim women. The burqa has associations with the Taliban, who systematically violated the fundamental rights and freedoms of Afghan women, leaving them with the lowest life expectancy in the region and some of the highest rates of maternal death.

Coercing women to wear the veil is one of an alarmingly vast array of gender-specific abuses committed against women of all religions, traditions, and societies around the world. States have an obligation to eradicate violence and discrimination against women in public and in private, including through an appropriate use of criminal law to punish those responsible.

But generalizations about women’s oppression do a disservice to one of the basic tenets of gender equality: the right to self-determination and autonomy, the right to make decisions about her life without interference from the state or others. There are undoubtedly women who are forced to wear the veil or feel tremendous pressure to do so against their own convictions. There are also European Muslim women who have spoken out to say that veiling was their own decision, citing motivations such as an expression of their faith and a desire to assert their identity. It is important to acknowledge that veiling can be a choice, in the same way that other convictions or conduct that have been shaped by societal, family or religious influences are experienced by the individual as an expression of their personality.

The right to autonomy, a core principle of women’s rights, is understood to be a part of the right to a private life guaranteed under international human rights law. The right to autonomy encompasses the right to make decisions freely in accordance with one’s values, beliefs, personal circumstances and needs. Exercise of this right presupposes freedom from coercion as well as freedom from illegitimate restrictions. It also includes the right to adopt a lifestyle which others in society disapprove of, or deem harmful to the person who pursues it.

At a practical level, it is hard to see how proscriptive laws targeting women serve the cause of women’s equality. Local laws and the nationwide French ban enacted in October 2010 provide for a variety of sanctions on women who violate the terms of the ban, including fines, good “citizenship” courses and community social work. The ban pending final approval in the Belgian Senate envisions up to seven days in prison.

Our research has found that the ban on teachers wearing headscarves in parts of Germany led observant Muslim women to abandon their chosen career, resulting in a loss of independence, social standing and financial wellbeing, although there are no reliable figures on how many women are affected. For women who are coerced by family members into wearing a headscarf, blocking access to these professions will not protect them from oppression. Moreover, this type of state regulation appears to aggravate discrimination against women who wear the headscarf in the private employment sector. Far from empowering them, the bans may lead to a deterioration in their social position.

Even in the case of face-covering veils, the arguments are not convincing. For those women who are compelled to cover themselves, a ban on full-face covering veils in all public spaces may mean they trade what critics call an “ambulatory prison” for one made of brick and mortar: their homes, as their male relatives may refuse to allow them out of the house without their veils. Strong social censure within Muslim communities against the wearing of full-face veils, and against forced veiling generally, will likely do more to empower women than laws and fines. State coercion and punishing the victims will not uproot oppression. What is needed is education, access to support and economic possibilities as well as effective means to seek justice against those who are oppressing them.

For those who cover themselves by choice, a ban forces them to choose between the ability to participate fully in society and the manifestation of their religious faith.

A ban imposed in public buildings and public transportation, as opposed to all public spaces, risks having an equally devastating impact on the ability of veiled women to conduct their lives, making commonplace activities—taking the bus, attending a parent-teacher conference in a public school, filing documents at a municipal office, even getting medical attention in a hospital—impossible while following their religious beliefs.

Q: What about girls who are forced by their families to wear the veil?

A: There is a tension between the rights of parents to educate their children according to their beliefs and the child’s right to personal autonomy (which increases with age). Under international law, states must respect the responsibilities, rights and duties of parents to provide, in a manner consistent with the evolving capacities of the child, appropriate direction and guidance in the child’s exercise of their basic rights. Reasonable people can, and often do, disagree vehemently over what is appropriate parental behavior, including everything from spiritual education to dietary regimes.

States, however, can intervene with parents’ choices on behalf of their children only when there is demonstrable actual or potential physical or psychological harm. Indeed, states must take appropriate legislative, administrative, social and educational measures to protect children where parents are responsible for physical or mental violence, injury or abuse, neglect or negligent treatment, mistreatment or exploitation. It is important to note that under international law, states must also take all appropriate measures to ensure that children are protected against discrimination or cruel punishment on the basis of the beliefs of their parents or family members.

As a general rule, it is inappropriate for the state to regulate whether parents can require their children to wear religious dress in conformity with the parents’ own convictions, unless this compulsion is associated with psychological or physical mistreatment. As a child approaches 18 she or he should have increasing autonomy, including in the choice over what she or he wears.

Human Rights Watch takes the view that blanket restrictions on students wearing religious dress and symbols in schools are contrary to international human rights law. Such restrictions may disproportionately affect religious minorities, stigmatize members of those minorities, and have a negative impact on children’s enjoyment of the right to education, often with a disproportionate impact on girls. Schools may have policies on uniforms but these should accommodate religious requirements, whether the religion is Muslim, Sikh, Jewish, Christian or other. Case-by-case restrictions may be legitimate when the school administration can demonstrate that specific dress, including full-face veils, interferes with the child’s ability to learn or participate fully in the life of the school. In this case, the paramount duty of protecting the best interest of the child may justify a restriction.

Laws requiring female students to wear the headscarf or veil at school equally violate the obligation of state authorities under international law to respect the rights of parents to raise their children in conformity with their own convictions, the rights of the child to personal autonomy, as well as the duty to avoid coercion in matters relating to religious freedom.

Q: Shouldn’t the burqa and niqab be banned for security reasons?

A: A wholesale ban on the full Muslim veil is a disproportionate response to the legitimate and concrete need in a variety of situations to ascertain someone’s identity. Airport checks, school pick-ups, administrative dealings with state officers and cashing a check are all obvious examples of where a person may need to prove their identity. Appropriate and sensitive measures can be adopted to satisfy both the individual’s right to manifest her religious beliefs and her duty to identify herself. In all the situations mentioned above, a woman wearing the full veil can be taken aside to show her face to a female guard, teacher, state or bank employee. Forms of religious dress that do not inhibit identification, such as the wearing of the headscarf or the Sikh turban, should not be the subject of restrictions in the name of security.