Calls to prioritize accountability at the UN Human Rights Council following renewed violence in Sudan were met with strong resistance from Arab states and largely rebuffed by African governments. Western governments were initially reluctant to push for an accountability mechanism in Sudan, unwilling to commit the resources or effort that they had devoted to a similar body for Ukraine immediately after Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022.

A group of countries eventually mustered enough votes to create a mechanism that can collect and preserve evidence of crimes, but not a single African government voted in favor, although some abstained. The Sudanese government has made it clear that it will not cooperate with the mechanism, which will operate outside the country.

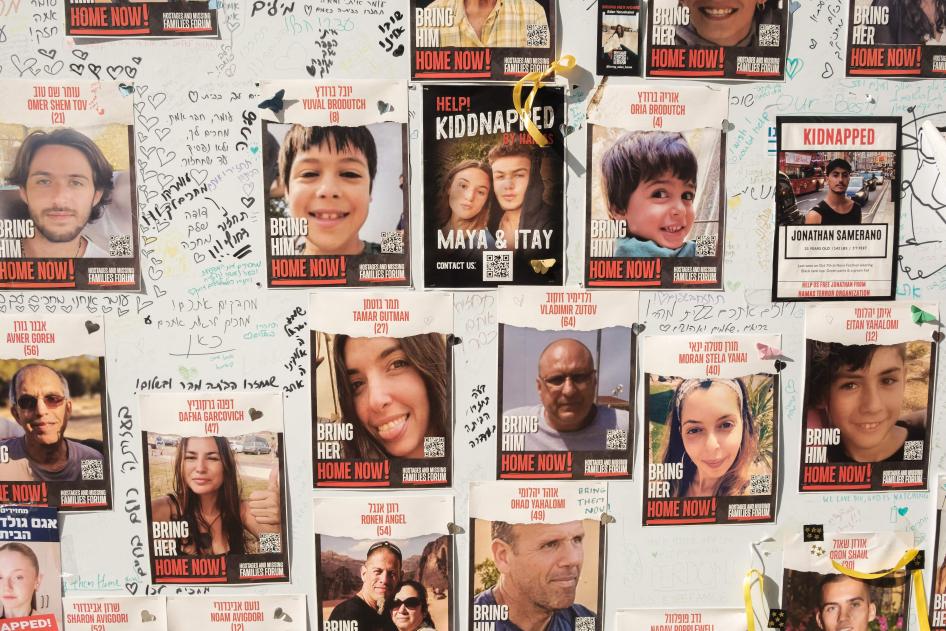

And yet, African governments do take positive action on human rights on some issues. They have tended to overwhelmingly support Human Rights Council resolutions that address the human rights situation in Palestine, while Western states oppose them. And in November, the South African government led an effort, supported by ICC member countries Bangladesh, Bolivia, Venezuela, Comoros, and Djibouti, to back the prosecutor’s investigation in Palestine. And in December, the South African government asked the International Court of Justice to determine whether Israel violated its obligations under the 1948 Genocide Convention in its military operations in Gaza. It also asked the court to impose provisional measures directing Israel to cease acts that could violate the Genocide Convention while the court decides on the merits of the case.

All governments can demonstrate human rights leadership to protect civilians. The challenge – and the urgency – is to do so consistently, in a principled manner, no matter the perpetrator or the victim.

The myopia of transactional diplomacy

Governments should center respect for human rights and the rule of law in their domestic policies and foreign policy decisions. Unfortunately, even normally rights-respecting governments at times treat these foundational principles as optional, seeking short-term, politically expedient “solutions” at the expense of building the institutions that would be beneficial for security, trade, energy, and migration in the long term. Choosing transactional diplomacy carries a human cost that is paid not only within, but increasingly beyond, borders.

Examples of transactional diplomacy abound.

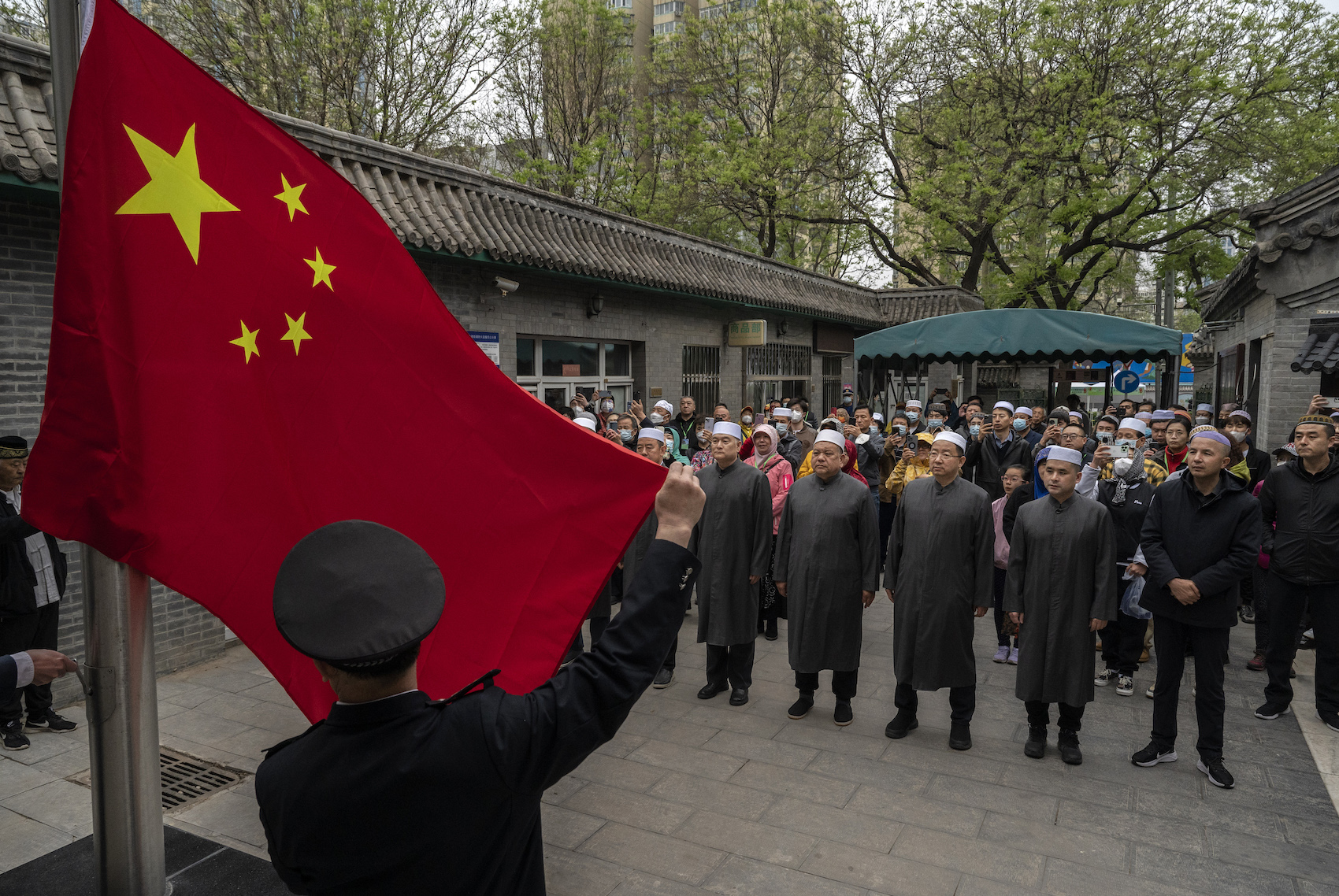

US President Joe Biden has shown little appetite to hold responsible human rights abusers who are key to his domestic agenda or are seen as bulwarks to China. US allies like Saudi Arabia, India, and Egypt violate the rights of their people on a massive scale yet have not had to overcome hurdles to deepen their ties with the US. Vietnam, the Philippines, India, and other nations the US wants as counters to China have been feted at the White House without regard for their human rights abuses at home.

Similarly, on migration, Washington has been reluctant to criticize Mexico, on whom it leans to prevent migrants and asylum seekers from entering the US. The Biden administration and that of Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador have worked in tandem to expel or deport tens of thousands of migrants in the US to Mexico and block thousands more from reaching the US to seek safety, knowing they are targeted in Mexico for kidnapping, extortion, assault, and other abuse. Biden has largely remained silent while López Obrador has attempted to undermine the independence of the Mexican judiciary and other constitutional bodies, demonized journalists and human rights activists, and allowed the military to block accountability for horrific abuses.