"Walking on Thin Ice"

Control, Intimidation and Harassment of Lawyers in China

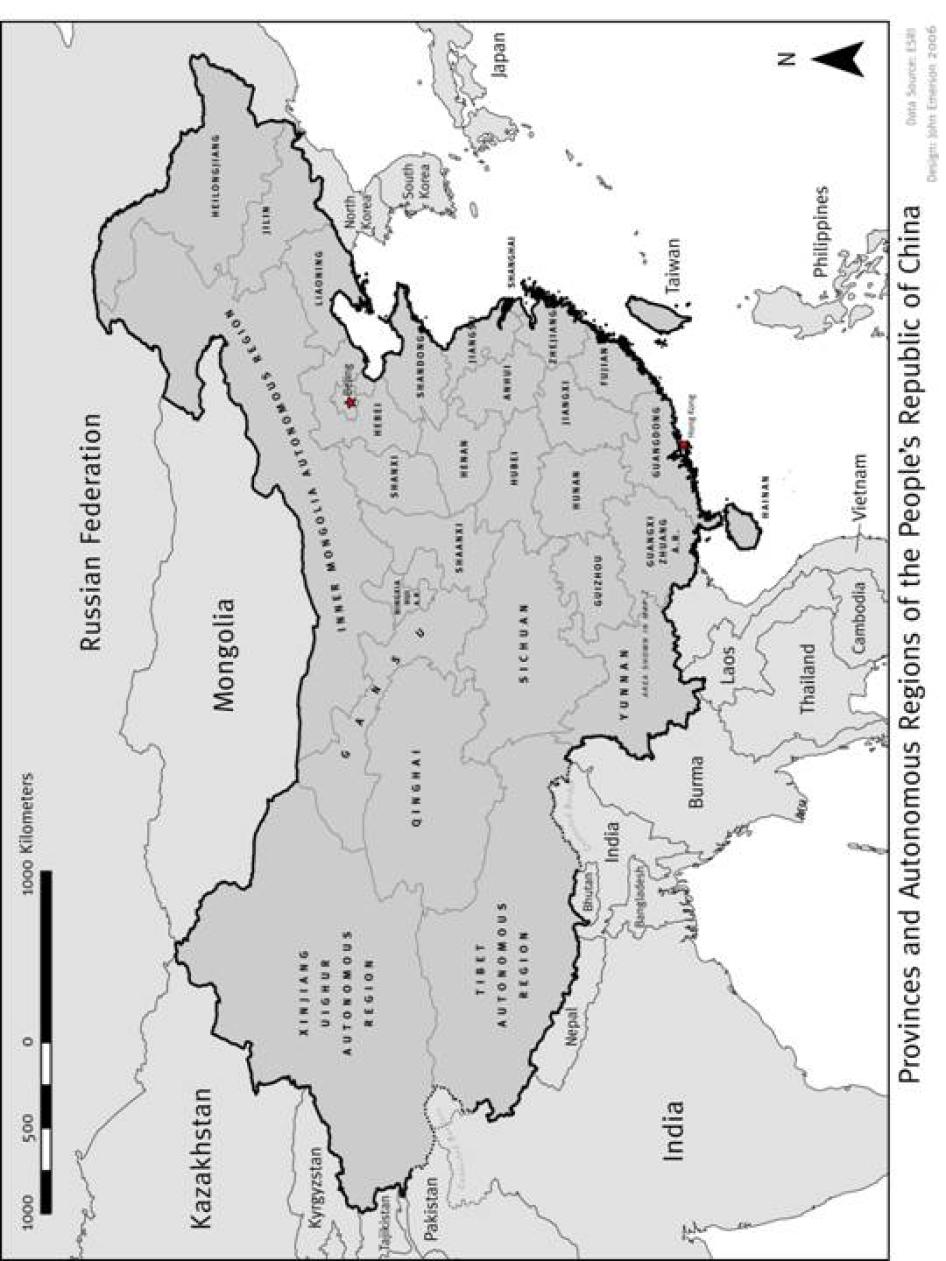

Map of China

I. Summary

The rule of law is important for the promotion, realization and safeguarding of a harmonious society. This principle should be rigorously implemented in all political, administrative and judicial sectors to ensure the powerful be checked and accountable for their misdeeds.

-Hu Jintao, June 26, 2005[1]

You cannot be a rights lawyer in this country without becoming a rights case yourself.

-Lawyer Gao Zhisheng, December 2005[2]

The development of a strong, independent legal profession in China is critical to the promotion and protection of human rights. Lawyers serve a critical function in the administration of justice, a point recognized by China's top leaders themselves,[3] as well as the large international legal reform community working in China.

Over the past two decades, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has progressively embraced the rule of law as a key part of its agenda to reform the way the country is governed. Importing entire pieces of Western-style legal institutions, the CCP is in the process of establishing a modern court system, has enacted thousands of laws and regulations, and has established hundreds of law schools to train legal professionals. It has publicized through constant propaganda campaigns the idea that common citizens have basic rights, elevated the concept of the "rule of law" to constitutional status, and recognized the validity of human rights norms with a new constitutional clause stipulating that "the state respects and protect human rights."

Yet, Chinese lawyers continue to face huge obstacles in defending citizens whose rights have been violated and ordinary criminal suspects. This report shows that lawyers often face violence, intimidation, threats, surveillance, harassment, arbitrary detention, prosecution, and suspension or disbarment from practicing law for pursuing their profession. This is particularly true in politically sensitive cases. Lawyers are often unable to seek redress for these threats and attacks as law enforcement authorities refuse to investigate abuses, creating a climate of lack of accountability for actions against members of the legal profession.

Instances of abuse by the national government or local authorities against lawyers have disproportionately affected lawyers who are part of the weiquan, or "rights protection" movement, a small but influential movement of lawyers, law experts, and activists who try to assert the constitutional and civil rights of the citizenry through litigation and legal activism. Weiquan lawyers represent cases implicating many of the most serious human rights issues that beset China today: farmers whose land has been seized by local officials, urban residents who have been forcibly evicted, residents resettled from dam and reservoir areas, victims of state agents' or corrupt officials' abuses of power, victims of torture and ill-treatment, criminal defendants, victims of miscarriage of justice, workers trying to recoup unpaid wages and rural migrants who are denied access to education and healthcare.

As one lawyer told Human Rights Watch:

All lawyers in China face the same constraints. What makes weiquan lawyers special is that they try to break free from these constraints, and they pay the price for it.[4]

There are also many structural reasons for the vulnerability of lawyers and the weak status of the legal profession. First and foremost is that lawyers and the entire legal system operate within a one-party political system. The legal profession in China, like the judiciary, is still far from attaining either formal or functional independence. More specific but related reasons most often cited by Chinese and foreign scholars are that legal reform is relatively recent, beginning only two years after the end of the Cultural Revolution, in 1978; the even more recent emancipation in 1996 of the legal profession from the Ministry of Justice, when the first Law on Lawyers was promulgated; the fact that bar associations remain under the control of the judicial authorities, which in turn remain under the control and supervision of Communist Party organs; and that the ability of citizens to challenge or sue the government is a very recent development (laws allowing administrative litigation and state compensation date only from 1989 and 1994, respectively).

Lawyers routinely identify lack of independence from the government as the key structural challenge facing their profession. As a comprehensive study on lawyers published in 2005 by the Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences Press points out, "The core question in the reform of the legal profession is the self-governance of the profession. Lawyers should independently carry out their professional duties and not be subjected to interference from state organs, groups or individuals."[5]

Even the objectives and functions of legal aid structures remain closely directed by the judicial authorities. In one typical speech in October 2007, the vice-minister of justice in charge of the administration of lawyers called on the judicial bureaus to "strengthen the direction of legal service employees and legal aid workers" to implement the objectives set by Party leaders,[6] reaffirming that "the key point in the work of lawyers is their role in contributing to the stability of a harmonious society,"and that lawyers "must support the leadership of the Party at all times."[7]

For all these reasons, lawyers are reluctant to work on politically sensitive cases, in particular human rights cases. Lawyers face powerful incentives to avoid work that is perceived by the CCP and government authorities as a threat or as a potential source of embarrassment, including work on cases seeking redress for abuses of power or wrongdoings committed by state or Party authorities. The result is not only abuse of lawyers, both physically and professionally, but a setback for the rule of law and the administration of justice. It also contributes to continuing public unrest as those with political or economic power, both inside and outside the CCP, trample on the rights of average citizens.

China's top leaders now routinely state their commitment to the rule of law. In his report to the 17th Party Congress in October 2007, President Hu Jintao stressed that "the rule of law constitutes the essential requirement of socialist democracy," and pledged to "respect and safeguard human rights, and ensure the equal right to participation and development for all members of society in accordance with the law."[8]

In a one-party system intent on keeping its hold on political power–and in the absence of other independent checks on power such as a free press or an autonomous civil society–this formidable effort at establishing the rule of law is aimed at providing stability and predictability to a rapidly modernizing society, supporting economic development, and imparting legitimacy to the Communist Party and government. Party and government officials have repeatedly stressed the need to develop the legal profession as part of their stated commitment to rule of law, and extolled the role that lawyers can play in the resolution of social contradictions to serve the overall political goal set by Hu Jintao of constructing a "harmonious society."[9]

There have also been benefits for ordinary Chinese. Lawyers are playing a greater role than ever in resolving ordinary disputes and representing victims of human rights abuses. They have helped gain recognition of grievances, promoted legal awareness among victims of abuses, advanced consumer rights, provided legal aid and counsel in both judicial and non-judicial settings, fostered better compliance with statutory requirements from law enforcement agencies and courts, and monitored the enforcement of judicial decisions.

If China's legal reform is to reach the next level, however, authorities need to act much more decisively to remove the obstacles that continue to prevent lawyers from playing their proper role. Lawyers' exercise of their profession-including their vigorous defense of controversial clients and causes-requires increased professional autonomy and protection against arbitrary interference by other judicial system actors, particularly though not exclusively in politically sensitive cases. As this report demonstrates, China still has a long way to go to lift arbitrary restrictions on lawyers and establish genuine rule of law.

Key recommendations

Human Rights Watch urges the Chinese government to address the plight of lawyers and the legal profession by:

·Immediately releasing all lawyers arrested, detained, or under supervision as a result of their professional activities, including as human rights defenders;

·Ending all officially sponsored attacks on lawyers and holding the perpetrators of such attacks accountable under the law;

·Making lawyers associations fully independent, insulated from interference by Party officials, security officials, and the Ministry of Justice;

·Repealing aspects of annual bar registration for lawyers which allow judicial system authorities to put pressure on and arbitrarily retaliate against lawyers for political and other reasons;

·Revising key laws and regulations governing the legal profession to bring them into accordance with international standards;

·Ensuring that arbitrary restrictions are not placed on the press in the coverage of politically sensitive cases; and

·Ensuring that lawyers, like other citizens, are able to exercise their rights to freedom of expression, belief, association, and assembly.

Human Rights Watch also urges key international interlocutors of the Chinese government and Chinese legal community to press the government to keep its commitments to law reform, professionalization of the legal community, and the rule of law. Large sums of money are allocated every year by foreign governments and international organizations to legal aid to China. While these efforts are laudable, their efficacy will remain minimal if restrictions on lawyers identified in this report are not lifted, and the internal dynamic of legal reform thus continues to be unnecessarily held in check. Key international interlocutors should also urge the Chinese government to issue an invitation to the United Nations special rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers to assess the situation of the legal profession and the judiciary.

More detailed recommendations, as well as more immediate steps the Chinese government can take, appear at the end of this report.

Methodology

This report is based on field research conducted over 12 months in Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou. The research included extensive review of Chinese language sources-including news accounts, official publications, and scholarly journals-discussions with scores of experts and analysts both inside and outside China, and 48 in-depth interviews with Chinese lawyers, legal experts, rights activists, and journalists with firsthand knowledge of the cases and issues covered in this report.

The scope of this study is necessarily limited by research constraints in China. China remains closed to official and open research by international human rights organizations. Over the years, Human Rights Watch has received numerous reports of the detention and interrogation of Chinese activists and scholars, including a number of lawyers, because of their contact with international human rights groups. As this study documents, many Chinese lawyers working on human rights or civil rights cases are closely monitored, and some have been interrogated or detained for their work.

As a result, unless otherwise noted, Human Rights Watch has replaced interviewees' names with initials which are not the interviewees' actual initials, and has not included other information that could be used to identify the interviewees. Interviews were conducted in settings that were as private as possible. All interviews in China were conducted in Mandarin without the assistance of interpreters.

Human Rights Watch takes no position on the underlying merits of the legal cases mentioned in this report, but rather focuses on what happens to lawyers who become involved in them.

II. International Standards for Lawyers

The independence of lawyers is a fundamental principle of international law. Lawyers play a key role in the administration of justice and protection of human rights. The importance that the international community places upon the independence of the judiciary and of lawyers is evidenced by their prominence in numerous international and regional treaties,[10] United Nations (UN) resolutions,[11] and international statements,[12] to many of which China has agreed, such as the Beijing Basic Principles on the Independence of the Judiciary.[13]

China has also signed but not yet ratified the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). Many of its provisions are part of international customary law. Among other things, the ICCPR recognizes the right to counsel, the principle of equality before the courts, and the right to a fair and public hearing by an independent court established by law.[14] The United Nations Human Rights Committee, which oversees implementation of the ICCPR, stated in its General Comment that "[l]awyers should be able to counsel and to represent their clients in accordance with their established professional standards and judgment without any restrictions, influences, pressures or undue interference from any quarter."[15]

The most detailed exposition of the rights and responsibilities of lawyers is found in the United Nations Basic Principles on the Role of Lawyers.[16] Among other things, the Basic Principles provide for:

·The independence of lawyers: "Adequate protection of the human rights and fundamental freedoms to which all persons are entitled … requires that all persons have effective access to legal services provided by an independent legal profession."[17]

·Freedom of expression and association: "Lawyers shall be entitled to form and join self-governing professional associations … The executive body of the professional associations … shall exercise its functions without external interference."[18]

·Confidentiality of communications between lawyers and their clients: "Governments shall recognize and respect that all communications and consultations between lawyers and their clients within their professional relationship are confidential."[19]

·Protection from unlawful interference: "Governments shall ensure that lawyers (a) are able to perform all of their professional functions without intimidation, hindrance, harassment or improper interference; (b) are able to travel and to consult with their clients freely both within their own country and abroad; and (c) shall not suffer, or be threatened with, prosecution or administrative, economic or other sanctions for any action taken in accordance with recognized professional duties, standards and ethics."[20]

·Right to due process for lawyers facing disciplinary sanctions: "Lawyers shall be brought before an impartial disciplinary committee established by the legal profession, before an independent statutory authority, or before a court, and shall be subject to an independent judicial review."[21]

In addition, "The accused or his lawyer must have the right to act diligently and fearlessly in pursuing all available defenses and the right to challenge the conduct of the case if they believe it to be unfair."[22]

These principles are now commonly referred to in academic legal studies in China, although they have not been incorporated into domestic law.[23]

III. China's Legal Profession

The President of the Supreme People's Court has issued important written instructions: courts at all levels must respect the professional rights of lawyers according to law…. and jointly protect fairness and justice.

-Notice of the Supreme People's Court, March 13, 2006[24]

The judicial organs will only give you what they want…. This is like a tiger blocking the road. Chinese lawyers are powerless.

-L.W., a Beijing lawyer, November 2007[25]

The development of the legal profession

China's recognition that a functioning legal system is necessary to support economic development, its accession to the World Trade Organization, and external pressure for a rules-based system for business have resulted in significant advances for the legal profession. The number of lawyers has surged dramatically over the past 20 years. In 1986 there were about 21,500 lawyers. This more than doubled to 45,000 by 1992, as the first private law firms emerged, largely to service the growing private business sector. There are now around 143,000 lawyers and 13,000 law offices.[26]Local bar associations have become more vocal in promoting the rights and interests of the legal profession. Academic debates and the internet have contributed to legitimizing the role and value of lawyers in society.

However, the dramatic increase in the number of lawyers has not yet been accompanied by the establishment of an accessible, equitable legal system. Vast numbers of Chinese citizens are still unable to use the system to seek justice. The proportion of lawyers to the total population remains low, at just 0.9 per 100,000.[27] The distribution of lawyers and law firms is disproportionately skewed towards the largest metropolises, such as Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou, with few services available in the western and interior part of the country. Lawyers also remain oddly outnumbered by judges and prosecutors: in 2004 there were 190,000 judges and 125,000 prosecutors.[28]

The role of lawyers under Chinese law

Lawyers are regulated by the Law on Lawyers of the People's Republic of China (hereafter, the Law on Lawyers). This is the primary, but not the only, statute governing the legal profession. It was revised in October 2007 in part to strengthen the rights of lawyers in legal proceedings, but failed to offer better avenues of redress when these rights are violated. Although the revised law will become effective on June 1, 2008, some of its most crucial advances depend ultimately on the revision of now conflicting provisions in the Criminal Procedure Law, which takes precedence over the Law on Lawyerswhen the two are in conflict.

The crucial issue of the lack of independence of the profession remains unchanged. Under Chinese law, lawyers are not free to form their own professional associations. Lawyers, law firms, and bar associations remain under the authority of the Ministry of Justice (MOJ), which gives them "supervision and guidance."[29] The All-China Lawyers Association (ACLA), the Chinese equivalent of a national bar association, is nominally in charge of "self-governing" the profession, but it too is subordinated to the MOJ.[30]

The ACLA and its local branches must comply with instructions issued by the MOJ, and must regulate the profession in accordance with the directives of the MOJ's department in charge of lawyers, the "Lawyers and Notaries Bureau." All lawyers must join the local branch of the ACLA in order to practice,[31] and joining the local branch also means being a member of the ACLA.[32] The head and secretary of the local lawyers association are generally chosen by local judicial authorities.[33]

Lawyers and law firms are therefore placed under a system of joint authority by the MOJ and by the MOJ-controlled lawyers associations. The judicial bureaus, the branches of the Ministry of Justice at the local level, assume "macro-control," including guidance, admissions, administration, and coordination, while the lawyers associations assume "micro-control" of body structure, professional duties, daily affairs, training, and education.[34] Disciplinary proceedings against lawyers by the MOJ or lawyers associations are not subject to independent judicial review.

The emergence of the weiquan movement

Partly in response to the inadequacy of legal remedies for large swathes of the Chinese people, who seem to have few avenues other than bringing their grievances to the streets, a movement of lawyers, law experts, and activists who try to assert the constitutional and civil rights of the citizenry through litigation and legal activism has emerged in past five to six years. The self-named "rights protection movement" (weiquan yundong) remains highly informal, and is mainly characterized by its willingness to take up and publicize cases that are politically sensitive because they involve citizens with grievances against local governments or state agencies.

"In essence," a recent academic study of the movement says, "lawyers and activists in the weiquan movement are generally always on the side of the weaker party: (migrant) workers v. employers in labor disputes; peasants in cases involving taxation, persons contesting environmental pollution, land appropriation, and village committee elections; journalists facing government censorship; defendants subject to criminal prosecution; and ordinary citizens who are discriminated against by government policies and actions."[35]

By circulating articles, maintaining web pages, and mobilizing internet communities, concerned journalists and scholars, and the foreign media, members of the rights protection movement frequently expose the lack of legality in local government decisions and lack of credibility in central government claims to "ruling the country according to law."

Weiquan lawyers and activists are often openly critical of the deficiencies of the legal system, and in particular of the lack of independence of the judiciary. At the same time, the hallmark of the movement has been to keep all activities strictly within the realm of Chinese law.[36] Along with other legal activists, weiquan activists have been involved in providing legal advice in a number of high-profile cases of protests, such as those in Taishi (Guangdong province), Tangshan (Hebei), and Zigong (Sichuan), which have attracted widespread attention, including from the international media.[37]

Weiquan has now become the term now typically used in China to identify the type of legal activities commonly referred as "cause lawyering," or public interest legal work.[38]

IV. Legal Rule and Party Rule: A Deliberate Contradiction

All law-enforcement activities should be led by the Party. All reform measures should be conducive to the socialist system and the strengthening of the Party leadership…. The correct political stand is where the Party stands."

-Luo Gan, Head of the Political and Legal Committee, February 1, 2007[39]

The power of the courts to adjudicate independently doesn't mean at all independence from the Party. It is the opposite, the embodiment of a high degree of responsibility vis-à-vis Party undertakings.

-Xiao Yang, President of the Supreme People's Court, October 18, 2007[40]

China's top leaders have acknowledged that greater demand for rights protection and many social protests are responses to local government abuses, and have promised to enhance access to judicial and administrative remedies, reiterating at every opportunity their commitment to the rule of law.

In October 2007 President Hu Jintao pledgedin his report to the 17th Party Congress to "build a fair, efficient and authoritative socialist judiciary system to ensure that courts and procuratorates [the Procuracy offices] exercise their respective powers independently and impartially in accordance with the law."[41]

Premier Wen Jiabao has made many similar statements. In January 2006, he acknowledged that "some localities are unlawfully occupying farmers' land and not offering reasonable economic compensation and arrangements for livelihoods, and this is sparking mass incidents in the countryside."[42] In March 2006, he promised "effective legal services and legal aid so as to provide effective help to people who have difficulty filing lawsuits," and a "strict, impartial, and civilized enforcement of the law."[43] And in March 2007, he pledged to "do a good job … in providing legal services" and more specifically called onlaw enforcement agencies to "exercise their powers and carry out their duties in strict accordance with legally specified limits of authority and procedures" and "accept the oversight of the news media and the general public."[44]

Yet despite the vigorous development of legal institutions over the past two decades, a basic contradiction remains: the Party pledges to operate under the primacy of the law, yet it insists at the same time on Party supremacy in all matters, including the law. The Constitution is defined as having "supreme legal authority," but also enshrines the principle of the "leadership of the Communist Party." Courts are supposed to adjudicate independently, but the Party opposes the idea of an independent judiciary. Power nominally resides in government organs, yet real power rests with the Party committees that shadow those organs at every level. State organs must carry out the paramount task of protecting "social stability" by offering legal remedies to protesters with legitimate complaints, but they must also suppress them if Party authority risks being undermined.

In practice, this permanent contradiction greatly undermines the effectiveness of the formal legal entitlements of Chinese citizens. Their ability to exercise their rights-or turn to the courts if their rights are violated-remains subject to the arbitrary assessments of Party authorities. Combined with the traditionally extensive powers of the bureaucracy, this creates a high degree of legal uncertainty for plaintiffs. Some social grievances are determined as legitimate while others are seen as destabilizing and must therefore be suppressed. Some protests are tolerated, while others are quashed and their organizers imprisoned. Some environmental, labor, and social activists are tolerated or even encouraged, while others are suppressed and arrested. Some lawsuits against local governments are allowed, while others are proscribed and their initiators punished.

In essence, when the larger goals of the party-state and the processes of a professional judicial system align, the system can function fairly independently. But when the Party decides that its political interests do not coincide with the administration of justice, rule of law considerations are suspended. Internally, Party and government authorities justify these shifts by the Party's own ideological axioms about the need to protect Party rule and political expediency, such as "looking at the big picture," "protecting social stability," or "harmonizing legal and social results." The determination process-in Party parlance, ding xing:"making a determination regarding the [political] nature of a situation"-is intrinsically political and arbitrary. It takes place outside of considerations for the integrity of the rule of law and relegates the role of the judiciary to a simple instrument of the Party.

Similarly, appealing to "social stability" is the most common justification given by the government for politically motivated repression of perceived dissenters or critics. Officials often cite the "adverse consequences" of news stories for "social stability" as a reason for censoring media reports about social unrest or punishing news outlets and journalists for reporting on them.[45] The cover-up of public health crises (such as the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome epidemic in 2003)[46]or industrial accidents (such as the chemical spill in the SonghuaRiver in November 2005)[47]have also been justified by the need to preserve "social stability."

At every level, China's key legal institutions are under the authority of the Party's political and legal committees. Through these institutions, corrupt local power holders can easily instruct the police to abandon investigations, foreclose legal challenges, and dictate the outcome of particular cases to judges, or frame protesters and activists on vague charges of threatening state security and social stability.

There are other structural factors that make it especially difficult for ordinary Chinese citizens to get access to justice. Legal institutions remain tightly controlled by state organs, the Party does not rely primarily on the judicial system to investigate corruption and wrongdoing of its members, many grievances are turned toward an ineffective petitioning system, and freedom of expression and the press remain highly constrained.

The low status of the legal profession is particularly salient in relationship to the law enforcement and judicial organs of the state, colloquially referred to as the gongjianfa: the Public Security Bureau (Gong'an, the police), the Procuracy (Jianchayuan, the public prosecution), and the courts (Fayuan). Of these three institutions, the Public Security Bureau is by far the most powerful, as its minister is traditionally a member of the Political Bureau of the Central Committee, the most important part of the party-state.[48] At the local level, the head of the Public Security Bureau is always a member of the Party Committee and generally the head of its powerful Political and Legal Committee in charge of legal affairs.

The imbalance of power between state judicial institutions and the legal profession means that Chinese lawyers depend greatly on cooperation from the former to perform their duties. Standard procedures such as accessing court documents and evidence held by the investigating organs, filing a case in court, or meeting with a client in detention are in practice achieved only at the discretion of these institutions.

The government has recognized the existence of these problems. In 2005, a task force from the National People's Congress was formed to investigate difficulties faced by lawyers and report to the President of the Supreme People's Court (SPC), China's highest judicial body. Subsequently, the SPC acknowledged that "Certain courts and a small number of adjudicators and tribunal staff did not respect sufficiently the rights of lawyers and their role in litigation procedures, and sometimes violated their rights." In March 2006, the SPC promulgated regulations calling courts to "earnestly implement the Law on Lawyers and protect lawyers' professional rights."[49]

But even lodging cases can be difficult for lawyers. Courts have a large degree of discretion in accepting cases, and frequently apply political and legal criteria in determining whether to accept cases.[50]Courts are often instructed by Party or government authorities not to take up certain cases or category of cases.[51] For instance, residents in Beijing have reported that the courts were instructed not to take up cases of residents forcibly evicted for urban redevelopment.[52]

The court structure is also an impediment to meaningful participation of lawyers. Under the current system, cases deemed important or "especially complicated" are internally decided by "adjudicating committees [shenpan weiyuanhui]," composed of senior judges and judges who are often members of the Party's Political and Legal Committee in charge of legal affairs.[53] Judges are then bound by the decision of the adjudicating committee. Lawyers do not participate in adjudicating committee meetings and cannot have their views represented there.[54]

Corruption is also an obstacle to obtaining justice.[55] A corruption case in 2004 in Wuhan, one of the largest courts in the country, exposed a sophisticated scheme of corruption within the court system and showed how multiple levels of judges and administrators were able to form circles of mutual benefit and profit. Rewarded activities in this system of bribe extraction included "taking bribes from the plaintiff and the defendant [chi yuangao, beigao]," "manufacturing court cases [zao jia an]," "selling evidence of the court case [mai zhengju]," "receiving kick-backs for passing cases [chi huikou],""abusing the power of judges to order suspension of businessoperation or confiscation of property [lan zhixing],""demanding commissions for making beneficial judgment [gao youchang fuwu]," and "embezzling court funding [tanwu nuoyong zhixing kuan]."[56] In 2006, a total of 292 judges across the country were found to have abused power for personal interests, and 109 of them were prosecuted and sentenced.

Retrenchment: The campaign for "socialist rule of law"

In April 2006, the authorities launched a large-scale political campaign for "education in socialist rule of law concepts [shehuizhuyi fazhi li'nian jiaoyu]," aimed at "strengthening and improving the Party's leadership over judicial work" and emphasizing the difference between "socialist rule of law" and "Western rule of law." The campaign was introduced by a landmark speech by Luo Gan, a senior member of the Politburo and the head of the Party Central Committee's Legal and Political Committee (the highest policy-making authority in legal matters),[57] on April 11, 2006. Luo announced an initiative to the strengthen the leadership of the Party over the courts, curb liberal ideas about greater independence for judges and lawyers, oppose the "infiltration" of the judiciary by unspecified "hostile foreign forces," and shift collective litigation from the judiciary towards the mediation system.

He also urged tighter control over legal activists, in particular the weiquan movement. Specifically, he urged the adoption of "forceful measures … against those who, under the pretext of rights-protection [weiquan], carry out sabotage … so as to protect national security and the political stability of society."[58]

Although the leadership role of the Party and the need to ward off threats to political stability are common themes in CCP rhetoric, this speech marked a departure from earlier policies and practices regarding the gradual professionalization of the judicial system.

A set of political instructions directed at judges in a provincial court shortly after the launch of the campaign illustrates the retreat from increased professionalization of the courts:

Recently, some judges have started to believe that to be a judge you just have to strictly apply the law in a case. In fact, this kind of concept is erroneous, [as] 'strictly apply the law' can have different explanations … [and] all the legal formulations have a clear political background and direction.[59]

Another target of the campaign was the judges' desire for greater judicial independence. In the same court document cited above, the Party Committee instructed court cadres to "respect political discipline":

We often talk now about giving prominence to the judge's position, but these are only words … we haven't said that the judge can escape political discipline. Court cadres must talk about politics and respect political discipline … We must stamp out the kind of narrow viewpoint that thinks that you can also do court work by having judicial independence, having the courts judge behind closed doors and not communicate with the relevant departments.[60]

In October 2007, a speech from the president of the People's Court, Xiao Yang, reiterated the importance of the shift from judicial independence to Party leadership: "The power of the courts to adjudicate independently doesn't mean at all independence from the Party. It is the opposite, the embodiment of a high degree of responsibility vis-à-vis Party undertakings."[61]

In contrast with the repeated claims that the courts must uphold "justice, [and] fairness, [and] base their decisions on the law only and serve the public," these instructions are clearly designed to make the judiciary even more subservient to the Party.

The socialist rule of law education campaign was also marked by the imposition of additional restrictions on lawyers handling collective cases and by a renewed crackdown on weiquan legal activists.

A few weeks before the formal announcement of the campaign, the government imposed new limitations on the legal profession by adopting regulations that significantly hinder the ability of lawyers to represent collective cases and protesters.[62]

The "Guiding Opinions on Lawyers Handling Mass Cases," promulgated through the All-China Lawyers Association, cited the need to maintain "stability" as a reason for their promulgation. They referred to the "major impact" that land seizures, forced evictions, relocations from dam areas, and lays-offs resulting from state-owned enterprise restructuring-precisely the kinds of problems that give rise to "mass cases"-can have on "the country's stability."[63] In essence, the Guiding Opinions made clear that political considerations were paramount and that lawyers must act as auxiliaries of the judicial bureaus when handling politically sensitive cases involving protesters.[64] The regulations were widely perceived as suppressing weiquan lawyers, who had been representing many collective cases.

At the same time, the government's hostility towards the weiquanmovement was reflected in the arrest and conviction of three of its most outspoken members, Chen Guangcheng, Gao Zhisheng, and Guo Feixiong. All three men had been providing legal advice to protesters and plaintiffs suing government authorities-Gao as a qualified lawyer, Chen and Guo as legal advisers (under Chinese law, it is not necessary to be a qualified lawyer to represent a defendant, including in criminal trials).[65]

The socialist rule of law education campaign also signaled tighter overall controls over the legal profession. In September 2006, the vice-minister of justice in charge of the administration of lawyers, Zhao Dachen, called for "strengthening the management" of the legal profession and guarding against neglecting "the essential attribute of the socialist legal worker."[66] The vice-minister openly stipulated that lawyers consider not only the legal results but also the "social result" of their work, so as to "build a high quality corps of lawyers that reassures the party and makes the people content."

The speech also called for "purifying the thinking" of judicial workers, and imparting to "the teams working on the administration of lawyers and the lawyers at large to 'ideological education.'" It sternly criticized judicial officials who neglected the "political attributes" of legal professionals:

Some comrades unilaterally believe that the legal service of lawyers is a mere legal professional activity, they neglect its intrinsic political attributes; … Some comrades incorrectly indicate that lawyers are a liberal profession, and neglect the essential attribute of the socialist legal worker.[67]

The vice-minister also warned against "ignoring national conditions" when copying foreign legal practices:

On the issue of perfecting the lawyer system, there are some comrades who simply copy from other countries' methods, ignoring the national conditions … It is necessary to strengthen further the concept of the general situation and all the work of the judicial administration must be incorporated in the general situation of the work of the Party and the state.[68]

In November 2006, Wang Shengjun, Secretary of the Political and Legal Committee of the Party, warned lawyers about opposing the Party:

There are people who use the tools of Western legal theory, and put on the hat of 'ruling the country according to law' to negate the leadership of the Party in respect to political and legal affairs; take up the slogan of 'judicial reform' to negate the socialist judicial system; or stir up individual cases to defame the political and legal organs, attempting to bring chaos in the sphere of judiciary ideology.… We must unwaveringly uphold the political socialist direction of China's political and legal work.[69]

In February 2007, warnings about the subversive character of foreign legal concepts were even more explicit in a new landmark speech by Luo Gan, the head of the Political and Legal Committee, and published in Seeking Truth, the theoretical journal of the Central Committee. Luo Gan's speech urged legal organs to guard against "hostile forces (who) have been trying their best to attack and fundamentally transform our judicial system."[70]

All law-enforcement activities should be led by the party. All reform measures should be conducive to the socialist system and the strengthening of the party leadership … There is no question about where legal departments should stand. The correct political stand is where the party stands.[71]

Luo nevertheless acknowledged that social unrest had legitimate causes. In some protests, participants had no direct interest in the cause but were venting accumulated anger, he said, adding that judicial departments should "reflect on this phenomenon" and "safeguard social justice and fairness."[72]

Yet, the crackdown against rights activists continued. In August 2007, the Ministry of Justice ordered the dissolution of the Beijing Bar Association's Constitutional and Human Rights Committee. The committee, established in 2001, was known for its progressive stance and counted several high profile public interest lawyers as members.[73]

On October 28, 2007, the government passed the long-awaited revisions to the Law on Lawyers,[74]a move state media hailed as designed to "make life easier for lawyers."[75] But two days later, on October 30, in an important speech pronounced at the closure of a training session on "Socialist rule of law concepts" held by the All-China Lawyers Association, Vice-Minister of Justice Zhao Dacheng ruled out greater independence for the legal profession, stressing to the contrary the need to further control the work of lawyers as a way to diffuse social unrest.

"Lawyers must guard against the concept of mere professionalism, and carry out in their work the unification of legal and social results," Zhao said.[76]

Mass cases coming from conflicts over land confiscation, demolition and evictions, relocation from dam areas, enterprise reforms, environmental polices are growing by the day. In these circumstances judicial administrative organs and bar associations must conscientiously carry out the guidance and supervisory duties, positively guide lawyers in accordance with the 'Guiding Opinions on handling mass cases' and other regulations and requirements.[77]

In essence, "harmonizing legal and social results" requires that lawyers tailor legal solutions to what the Party thinks best serves social stability.

Against this highly politicized background, lawyers in China face huge obstacles in defending citizens whose rights have been violated. Yet, more and more lawyers are taking such cases, encouraged by profound social dynamics such as rising rights awareness among the populace, repeated expressions of commitment to the rule of law by the authorities, support from legal professors and experts, the growth of a professional culture among judges, prosecutors, and legislative drafters, and, at least for some, the high social status lawyers enjoy when they are commercially successful.

V. Violence Against Lawyers

For the past few years the working environment of the legal profession has become more dangerous day by day.

-Text of an open letter by 53 lawyers, December 2006

For lawyers, retaliation by the local authorities is a big danger. We are all walking on thin ice.

-P.D., a Beijing lawyer, November 2007

Many Chinese lawyers routinely complain that violence, or the threat of violence, is an ever-present risk against which they feel inadequately protected by the state. The majority of cases of violence against lawyers are purely criminal, but many others are linked to their involvement in civil rights or human rights cases, and a few seem abetted by law enforcement personnel or local officials. This chapter documents the failure of the Chinese government to fulfill its responsibility under the law to adequately safeguard the security of lawyers and people who, without having the formal status of lawyer, exercise the functions of lawyers.

The government acknowledges that lawyers play an important role in the administration of justice and has indicated-including through instructions issued by the Supreme People's Court-that legal institutions and law enforcement agencies must ensure that lawyers receive sufficient protection so as to be able to carry out their functions unhindered. But, in practice, lawyers say that criminal threats and assaults against them are a frequent occurrence; that those instances are not vigorously investigated; that bar associations are unwilling or unable to help them; and that they have to keep silent about specific incidents for fear of retribution or loss of business.

Despite lawyers being adamant that the risk of violence against them is an acute problem for the entire legal profession-a claim supported by countless articles in professional and legal publications-there are no recent published empirical studies documenting this. Very few cases have been reported in the official media over the years.[78] Individual cases that have been given publicity in domestic media rarely involve politically sensitive cases and tend to show the government responding to the violation. This pattern suggests that only isolated cases or general and abstract discussions about them are tolerated in professional, academic, and media publications.

Indeed, after the national bar association published for restricted distribution a ground-breaking report on abuses against lawyers in 2002, in the context of a three-year program to study the problems faced by lawyers, Beijing judicial authorities cut the program short and prohibited the publication of similar reports.[79] The report, based on a survey of 598 respondents, exposed severe difficulties for lawyers, and described cases of lawyers harassed, detained, arrested, or prosecuted in the course of carrying out their professional duties.[80] The cases included lawyers assaulted by the opposing party: Yan Yujiu (Sichuan), She Yuanxi (Sichuan), Pei Shan (Xinjiang), Wang Bing (Liaoning), Jia Tianjin (Henan), Wang Fei (Chongqin); lawyers attacked by unidentified aggressors, including Liu Chixian (Guangxi), Yu Haifeng (Shandong), Yang Jianxin (Heilongjian), Teng Kuang (Heilongjiang); and lawyers kidnapped by the opposing party including Ren Shangfei (Hebei) and Chen Guangqiang (Fujian).[81]

In December 2006, 53 lawyers and law experts took the rare initiative of addressing an open letter to the central authorities to ask the government to protect lawyers.[82] The drafters of the letter, lawyers Cheng Hai, Gao Fengquan, Zhang Lihui, Li Heping, Ouyang Zhigang, Li Jinsong, and Meng Xianming, wrote that the environment had grown "day by day more dangerous" over the past year:

For the past few years the working environment of the legal profession has become more dangerous day by day. Not only must lawyers face all sorts of illegal restrictions from the judicial and administrative departments, such as being followed, being, at times violently, prevented access [to clients or witnesses], or being prevented from gathering evidence, but their personal security is also threatened.

These threats are not coming solely from the opposite party: they increasingly come from forces of the Public Security Bureau, the Procuracy, and the courts themselves. Between March and August this year, more than four cases of lawyers being attacked by public security or court personnel have been exposed nationally, this is a frightening development![83]

The government to date has not acknowledged the letter, while domestic Chinese media never reported the initiative. One lawyer told Human Rights Watch that the Party authorities in charge of judicial affairs had instructed the judiciary to maintain vigilance against "people who try to use the legal system to attack the party and the government," and that it would never respond to this type of public appeal.[84]

Gao Zhisheng, Chen Guangcheng, and the crackdown on cause lawyering

The case of the human rights lawyer Gao Zhisheng, sentenced to four years under subversion charges after months of increased harassment, has received extensive international attention, and prompted foreign governments to make regular diplomatic representations to the Chinese government, though with little apparent effect.[85] Along with the arrests of the blind barefoot lawyer Chen Guangcheng and the Guangzhou-based legal activist Yang Maodong (better known under his pen name Guo Feixiong), Gao Zhisheng's arrest marked the peak of a campaign by the Chinese authorities to squash what they perceived as a nascent legal opposition movement in 2006.

Suppression of Gao Zhisheng

Gao was a successful lawyer who specialized in defending cases of corruption, land seizures, police abuse, and religious freedom. In 2001 he was rated by the Legal Daily, a publication operated by the Ministry of Justice, as "one of the top ten lawyers in China." Increasingly outspoken, he started to take on more politically sensitive cases, including torture of practitioners of the banned Falun Gong movement. As the courts systematically refused to lodge his lawsuits, he turned to writing reports and publishing open letters denouncing these abuses, including to the top leadership of the Communist Party.

As 2006 progressed, the Chinese authorities first put Gao Zhisheng and his family under around-the-clock police surveillance, then suspended his law firm license and stripped him of his professional lawyer's license. Then they arrested him, detained him incommunicado for six months, coerced him into pleading guilty and relinquishing the right to choose his lawyer, and tried him in proceedings his family members were not permitted to attend. He was then sentenced to four years' imprisonment for subversion with a five-year reprieve.[86]

According to the court, the reprieve was granted because Gao had cooperated with the investigators and informed on fellow human rights activists. Gao later denied that he had informed on fellow activists, and stated that he had only agreed to the terms forced upon him by the authorities under psychological and physical pressure. The interrogators had questioned him for an extensive period of time under bright lights and openly threatened to retaliate against his family if he did not cooperate, he told a fellow activist.

A long string of violent incidents that had begun in 2005, starting with constant surveillance by plainclothes police officers, gave Gao reason to heed those threats. Those incidents included:

·On October 19, 2005, one day after Gao published a scathing open letter to the top state leaders about abuses against religious and Falun Gong practitioners, he received an anonymous threat by phone: "We know where you live and we know where your daughter goes to school." The next day Gao and his wife verified that their 12-year-old daughter was indeed followed by plainclothes police officers.

·On November 21, 2005, a group of unidentified men followed Gao to a meeting in a restaurant with the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Torture Manfred Nowak, crowding the room they were sitting in and displaying hostile, intimidating behavior. After a UN aide took a picture of the group, the men protested vehemently and forced her to delete the picture. Gao and Novak retreated to a hotel to continue without their meeting being directly observed.

·On March 10, 2006, plainclothes police officers who were monitoring his law firm stopped lawyer Li Heping-who was handling Gao's appeal against the suspension of his professional license-from accessing his office. The men wrestled Li out of the building and threatened Gao.

·On July 30, 2006, Gao was violently beaten by policemen in charge of the surveillance of his home, and then briefly detained at the local police station. Gao had come down from his apartment to request that they turn off the motor of their vehicle. A dispute erupted and three of the seven-man team posted there assaulted Gao. One of them tried to hit him with a large brick. Gao sustained minor injuries to his left arm and to one of his legs.

·On August 15, 2006, Gao was arrested at his sister's home in Dongying municipality, ShandongProvince. He was taken away in a car and disappeared for over a month. His family was finally notified on September 21 that he was in police custody for suspected criminal acts.

·Gao's wife, Geng He, subsequently was warned by police officials not to contact or communicate with anyone, especially the media. If she complied, she was told, she would be able to meet Gao Zhisheng. (Gao remained incommunicado until his trial on December 12.) The family continued to be harassed by agents who monitored them around the clock, followed them everywhere, prohibited friends and visitors from coming to see them, and warned them about communicating with anyone about Gao's case.

·On November 21, 2006, plainclothes policemen made an attempt to pick up Gao's two-year-old son from kindergarten. The officers showed their police badge to the teacher, who refused to comply. Gao's wife's enquiries to the police went unanswered.

·On November 24, 2006, two police officers punched Gao's wife in the street after she challenged them for tailing her. She called the police station, which declined to send a patrol but asked her to report to a station close to her residence.

·On December 16, 2006, a few days before Gao's trial, his 13-year-old daughter refused to be escorted home from school in a police car. Police officers dragged her into the car, bruising her legs and neck.

The violence and intimidation against Gao Zhisheng appears more typical of the tactics used by the authorities against people identified as political dissidents than the forms of intimidation recounted by average lawyers. What made Gao a dissident in the eyes of the authorities was his refusal to yield to pressure and desist from denouncing the lapses of the judicial system and the defects of Party control over the legal system. Gao's outspokenness, his defense of the Falun Gong, his acerbic interviews with foreign media and open letter to the state leaders had clearly made his case the province of the political police-the State Security Bureau and State Protection Bureau-rather than the judicial authorities. The fact that the authorities saw Gao as a dissident was later reflected in his sentence for subversion, based on his having published nine articles that "defamed and made rumors about China's current government and social system, conspiring to topple down the regime."[87]

Yet, even if in the eyes of the authorities Gao was tried as a dissident rather than a lawyer, his work as a lawyer prompted the retaliation. His case became emblematic of the authorities' blatant disregard for legality in the methods used to silence him and the chilling effect his case had on the legal profession.

Attacks against Chen Guangcheng's legal team

The second case that attracted considerable attention in 2006 was the long string of abuses and procedural flaws in the trial of the blind "barefoot lawyer" Chen Guangcheng. A self-taught legal activist, not a licensed lawyer, Chen documented abuses committed by the local family planning authorities of Linyi municipality, ShandongProvince, in a report made public in June 2005.[88] He was first put under house arrest in mid-August 2005 as he was trying to help four villagers to bring a lawsuit against the family planning bureau. By this time, Chen's case had become something of a "cause célèbre" among weiquan and legal activists, and a number of lawyers, legal experts, and rights activists started to organize his defense and publicize his case.

On March 11, 2006, following a confrontation with the police over the beating of a neighbor by unidentified men, Chen was taken away by police and detained incommunicado for six months. After being formally charged with "inciting crowds to disrupt traffic" and intentional destruction of property, Chen was sentenced in August 2007 to four years and three months' imprisonment. In October, the appellate court annulled the first trial, although it did not make clear on what grounds, and ordered the case remanded to the same court, which in December imposed the exact same sentence for the same crimes. The second verdict was upheld in January 2007 by the appellate court.

Lawyers who came to Chen's defense were repeatedly subject to intense harassment and in some cases physical attack every time they came to Linyi to visit Chen, interview relatives and villagers, or prepare for and attend the trial. Incidents included:

·On October 4, 2005, Bejing lawyers Li Fangping and Li Subin, accompanied by law lecturer Xu Zhiyong, attempted to visit Chen, who was then under arbitrary house arrest. They were stopped by over a dozen unidentified men surrounding Chen's house. Xu Zhiyong and Li Fangping were shoved and punched, and the three men were taken to the Shuanghou police station where they were interrogated until the following morning, before being escorted back to Beijing.

·In late June 2006, while Chen was detained at the YinanCountyDetentionCenter, three lawyers accompanied by the Beijing-based human rights activist Hu Jia attempted to visit Chen's family. As they entered the village, unidentified men surrounded their car and flipped it over. The men threatened the group and physically prevented them from reaching Chen's house. Lawyer Li Jingsong started to take pictures but had his camera snatched by the men. Uniformed police present on the site refused to intervene and took Li Jinsong in for questioning.

·On July 10, a few days before Chen's hearing date for the trial, lawyers Li Jinsong, Li Subin, and Zhang Lihui, accompanied by Hu Jia, traveled to Linyi to gather testimonies and visit Chen's relatives. Chen's wife was taken away in a police car before she could meet them.

·On August 17, lawyers Li Fangping and Zhang Lihui, along with legal scholar Xu Zhiyong, arrived in Linyi for Chen's trial, due to be held the following day. Unidentified men physically intimidated the group in a restaurant, and accused Xu of being a pickpocket. The police detained the three lawyers, and held Xu long enough that he was unable to attend the trial.

·On November 27, lawyer Teng Biao, who had traveled to Linyi to attend the re-trial of Chen, was forcibly taken away and detained for five hours by the police. He was handled roughly, with five or six policemen pinning him to the ground while they searched him, confiscated his mobile phone, and questioned him. He was released without explanation as to why he was detained.

·On December 27, lawyers Li Fangping and Li Jinsong were ambushed on their way to meet with Chen to discuss his second appeal. Two cars without license plates stopped the overnight bus on which they were traveling. Eight unidentified men dragged Li Jinsong out of the bus and without a word started hitting him with metal pipes. Li Fangping stepped off the bus and was attacked as well, sustaining head injuries that required emergency care. The lawyers suspected that the local authorities knew of their itinerary, as they had communicated with the judge who had conveyed Chen's request to see them.

As in the case of Gao Zhisheng, the local authorities put under surveillance, harassed and threatened the family of their target. Chen's wife, Yuan Weijing, has been under permanent surveillance since Chen's arrest. She has filed numerous formal and informal complaints, including with the help of some Beijing lawyers, all to no avail. When Yuan attempted to travel to Manila in August 2007 to collect a human rights award from the Ramon Magsaysay Foundation on Chen's behalf, police confiscated her passport and sent her back to Shandong province. A few days later, she was forcibly pulled from the bus she had boarded to return to Beijing by a group of plainclothes policemen.[89] To date she is still under around-the-clock police surveillance and her movements are restricted.[90]

Chinese domestic media never reported on Gao Zhisheng's or Chen Guangcheng's cases except to announce their convictions,[91] and official spokespersons evaded questions from foreign journalists about these cases during the Ministry of Foreign Affairs' weekly press conferences.

The conclusion that weiquan lawyers drew from the cases of Gao and Chen was that the central authorities would condone physical abuses against lawyers if they were involved in cases that could result in significant embarrassment for the government or the Party, even at the expense of damaging the credibility of the legal system as a whole.

"The silence of the central authorities implies that they endorsed the actions of the local officials who beat up lawyers," said one attorney directly involved in the Chen Guangcheng case.

In Beijing it is the state security that was doing the surveillance of some of the lawyers [during the trial]-how could the central government not know about the case? What's more, this case was widely reported by international media-the New York Times, Radio Free Asia, we got calls from media from the world over. And it was a big discussion topic on internet.[92]

According to one account given to Human Rights Watch by a legal expert, the Ministry of Justice in Beijing had initially not paid any attention to Chen Guangcheng's case, and that it was the local authorities in Linyi who were solely responsible for the abuses against Chen and various members of his defense team. But the central authorities then stepped in:

After the international outcry that followed the first trial, the central authorities were forced to take notice. The party authorities at the Ministry of Justice mandated a special small investigative team to review the case. The team concluded that the trial had clearly violated the procedures…. The Political and Legal committee of the Party ultimately decided that it could not uphold the trial but nor could it give encouragement to the weiquan agitators. So it instructed the appellate court to have the case remanded.[93]

It is impossible to verify this account of the central authorities' involvement, given the notorious opacity of decision-making in cases with political overtones. Nevertheless, the Chinese government has a responsibility to uphold the law. The silence of the government and the official media in face of what appears to have been blatant criminal intimidation and unlawful acts over many months indicates that the central government was, at a minimum, abetting the repressive tactics of the local authorities and the political police.

Weiquan lawyers readily acknowledge that Gao's and Chen's cases were out of the ordinary because their prominent standing in international media prompted the highest Party authorities to dictate the outcome.[94] But these lawyers are also adamant that these cases were emblematic of the prevalent problems that lawyers and legal advocates face in their work: physical danger, surveillance and intimidation by state security personnel, refusal by law enforcement agencies to protect lawyers or entertain complaints, impunity for the attackers, and media censorship surrounding the cases.

One lawyer, in reference to Gao and Chen, told Human Rights Watch:

These cases may have been exceptional but the problems they exposed were typical of those that affect the legal profession. Completely typical.[95]

Other lawyers who were not involved in the case shared this view in private discussions.

What do you think? If this can happen when so many people pay attention to the case-lawyers, law professors, the foreign media, the internet community-how could the situation be better in regular cases? The problems shown by the 'Old Gao' and [Chen] Guangcheng cases are really very widespread.[96]

According to another lawyer, it was precisely because Chen Guangcheng's case was so typical that it inspired the legal community to support him.

Personally I don't think this case was well handled [by Chen's legal team], but the hardships faced by the defense were not out of the ordinary for lawyers in China. The local authorities are too powerful-this is why you have to avoid alienating the central authorities in a case like this.[97]

Beyond Gao and Chen: Recurring violence against lawyers

Violence against lawyers is not limited to high profile cases that the authorities see as political. In fact, cases of assault against lawyers appear with disturbing frequency in all types of cases, from commercial disputes to administrative lawsuits. For instance, between 2005 and 2006, at least five cases of physical assaults against lawyers in Shanghai were reported and widely discussed in the domestic media.[98]

The cases of Wang Lin, who was beaten by a court official in Tianjin, and of Mao Liequn, who was attacked by a gang in Shanghai, received nationwide attention among lawyers, with various bar association trying to publicize the incidents to advance the cause of lawyers in public opinion and government circles. More sensitive cases like Gao Weiquan, who was dragged from a petition office, Yang Zaixin, attacked two weeks after having his professional license suspended, and Tang Jingling, who was assaulted in Guangzhou, are well known among weiquan activists but have received no publicity. All these cases were regularly cited by legal professionals interviewed by Human Rights Watch as typical of the dangers faced by lawyers.

Wang Lin, Tianjin

The March 2006 attack on Beijing lawyer Wang Lin is probably the most famous case to be covered by the official media. The fact that the incident took place just a few weeks after the Supreme People's Court had promulgated new measures intended to strengthen "the protection of lawyers carrying their professional duties" was of particular significance.[99]

On March 28, 2006, Wang Lin went to file a collective administrative lawsuit against the government construction bureau at the Tianjin Nankai District court. He was accompanied by 11 plaintiffs who were challenging a decision from the Tianjin Construction Bureau to evict them, arguing that the scope of an eviction order granted two years ago had been broadened without permission to encompass their homes.

The vice-head of the administrative court refused to accept the filing of the case, asserting that the plaintiffs needed to file individual cases, not a collective one. Wang suggested that he would do so, but the court official replied, "Even if you file plaintiff by plaintiff we won't lodge this case." Wang asked for a written court document to that effect, which the official refused as well. "I am the court and the court is me. If I say no filing, that means no filing," the official told Wang.

In the heated discussion that followed, the official tried to punch Wang, and then shoved him outside the court, grabbing him by the back of the neck and warning him: "Be careful when walking in the street at night."

Because Wang was relatively well-known, having been featured in a program by China Central Television that exposed the wrongful eviction of over 7,000 people in central Hunan province, and having worked for an influential law firm, he managed to get a prominent newspaper, the Beijing Youth Daily, to run a detailed exposé of the incident shortly afterwards.

The publication of the article generated a strong debate among lawyers, who spotted an opportunity to highlight their plight and denounce the authorities' inaction. Many articles quoted Wang Lin's comments published on his personal website:

You can beat me up, but please do not beat me up in court; please do not beat me up as I carry out my professional duties. Being beaten in this manner, I feel that not only myself but the law itself is being beaten. And this is what I find difficult to accept.[100]

One online commentator suggested that petty harassment of lawyers by court officials was widespread:

This is far from being the only case. In many local tribunals the personnel are really beyond belief! Last year a certain lawyer was even attacked during the hearing by a court official…. Court personnel make our work difficult and we have to endure countless humiliations.[101]

In early April, media reports announced that the president of the Supreme People's Court, Xiao Yang, had himself issued "internal instructions [pishi]" to investigate the Wang Lin incident "and solve it according to the facts."[102]

On April 15, the Tianjin Party political-legal committee set up an investigation team with members from the committee, the court and the Procuracy.[103] The team concluded that "there was not sufficient evidence to resolve this case," but nevertheless dismissed the court official. Although Wang was personally vindicated, the Nankai court has yet to grant a hearing for the administrative lawsuit of the plaintiffs whose homes were destroyed.

Although the outcome of the episode-the sanction of a court official-is the exception rather than the norm, lawyers interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that "the case was emblematic of the behavior of some local courts."[104]

Gao Weiquan, Shenyang

Gao Weiquan's case is also illustrative. Gao (who is no relation to Gao Zhisheng), a 59-year old lawyer from Shenyang, Liaoning Province, was physically assaulted on April 13, 2006, as he attempted to file a complaint for retrial at the Letters and Visit Office of the Liaoning Province High Court.

According to Gao's account, the staff refused to file his complaint without explanation. Gao then asked to see the head of the Letters and Visits office. He was told to "go look for him outside." Three court staff members then brutally dragged him out of the building, hitting and kicking him with their fists and feet. Gao called the police. The court personnel justified his physical removal from the court on the grounds that Gao had been "petitioning without grounds" and "damaging the door" of the office. The police refused to lodge a formal complaint. The next day, Gao filed a report to the Shenyang lawyers association and the Liaoning High People's court. Three weeks later, on May 8, having still not received an official answer, Gao wrote an open letter to the provincial Liaoning lawyers association and posted it on the internet:

How come I have still not heard a word from the court? … A lawyer is beaten and so what? If even the lawyers association doesn't care, how can we expect the Public Security Bureau to do anything about it?[105]

Despite eliciting much support on internet from fellow lawyers, neither the local judicial authorities nor the Liaoning lawyers association have taken any action to date.

Mao Liequn, Shanghai

Even when local bar associations are more vocal, the results are limited, as illustrated by the attempt by the Shanghai bar association to improve protection for lawyers after a 2006 spate of attacks against attorneys doing their jobs.

In August 2006, lawyer Mao Liequn was severely beaten by a gang of 10 men while representing a Hong Kong company in talks to evict a Shanghai firm illegally occupying a dockside storehouse in Pudong. Mao suffered a broken nose and multiple injuries to his head, hand, and body that required hospitalization. "One man grabbed my clothes, hitting me with his fist on the face, while another one grabbed my hair. Other joined and blows rained all over my body," Mao recounted to a Chinese journalist. His client, who was accompanying him, was also assaulted. Mao was then dragged into a nearby building, where he was again beaten up. An associate of Mao managed to call the police, and, crucially, to film from his car the assailants as they were escaping.[106]

The Shanghai bar association reacted vigorously. A spokesperson told the press that the Mao Liequn attack "came as a warning to all of us," and that the bar association was proposing draft legislation to strengthen the protection of lawyers carrying out their duties. "In recent years many lawyers from Shanghai were assaulted in the course of their professional work," the spokesperson said.[107] "We feel that there should be a law for protecting lawyers."

Local press reports highlighted three other recent cases of lawyers having been assaulted: On September 28, 2005, a lawyer from the Guochen law firm was attacked and threatened by thugs while handling a commercial dispute between rival firms. The harassment continued afterwards, ranging from threats to cutting the water supply to his private home. In two separate incidents in July and August 2005, two lawyers from the Guoxiong and Liancheng law firms, respectively, were attacked by disgruntled parties in front of the court building.

The Shanghai bar indicated that the proposed legislation would seek to guarantee the rights and safety of lawyers during negotiations, investigations, and evidence gathering.[108] Such legislation had been discussed for a number of years and had been recommended for ratification by the judicial affairs committee of the Shanghai People's Assembly as early as 2004, but to no effect. Despite the national attention given to Mao's case, it failed to generate momentum for the adoption of such regulations.

A few months later, on October 19, 2006, another Shanghai lawyer was violently assaulted. He Wei, from the Minjiang law firm, was working free of charge on a labor case, seeking compensation for a worker who had lost three fingers in an accident at a printing company. When He tried to visit the company, the manager reportedly told him: "A lawyer? What kind of thing is that?" and proceeded to beat him with the help of his associates, kicking him repeatedly on the ground.[109] He Wei sustained a perforated eardrum and various other injuries that required hospitalization. Shanghai media reported the case, including on television, and He Wei's attacker was later sentence to a year of imprisonment, but there was no new public appeal from the bar association to enact regulations protecting lawyers.[110]

Despite the inability of bar associations across the country to defend individual lawyers who represent sensitive human rights cases, the associations often do show professional solidarity with the victims of abuses.

Li Heping, Beijing

Li Heping, a lawyer from the Beijing Globe law firm, was kidnapped, detained, and beaten by a group of unidentified men on September 29, 2007. His captors released him after six hours, having threatened him with further violence if he did not leave Beijing permanently.

Initially a specialist in intellectual property and civil law, Li had also participated in a string of sensitive cases, including that of the blind activist Chen Guangcheng; the underground Christian sect leader Xu Shuangfu, who was executed with 11 other members in November 2006;[111] Yang Zili, a member of a university discussion group (New Youth Study Group), who was sentenced in 2001 to eight years imprisonment for "subverting state power";[112] and other cases highlighting abuses by state agencies.

In the few days preceding the attack, Li had reported being followed by police and plainclothes officers he believed he had met before and were from the State Protection Bureau. On September 29, around 5 p.m., one of these officers invited him to get into his car. Li declined. Five minutes later a group of men seized Li, covered his head with a hood, bundled him into a car, and drove out of Beijing. He was then dragged into a basement where he was beaten up by men using electrical batons. They ordered him to leave Beijing with his family or face retribution. Li's captors also copied the contents of his computer, and took his external hard drive, mobile phone chip, and notebook, before detaining him for a day in a Beijing suburb. Li reported the incident the next day, and was promised a "serious investigation" into the incident by the police. "They want all my family to move out of Beijing, to sell my apartment, my car and leave Beijing. In their words, I am to 'get the hell out of Beijing [gunchu Beijing],'" Li recounted to Radio Free Asia the next day.[113] Li has since indicated he intends to continue his work undeterred.

Yang Zaixin, Guangxi

An attorney from impoverished Guangxi province, Yang Zaixin, was dismissed from his law firm in January 2006 after he took a series of sensitive cases, including those of defendants accused of being members of the banned Falun Gong. Yang posted articles online protesting his dismissal and continued his involvement in sensitive cases.

On February 17, 2006, his home was searched by the local police, who confiscated his computer and court case documents, and took him to the police station for 24 hours to question him about his activities and links with overseas media and groups. Undeterred, Yang continued to denounce his dismissal in internet postings and interviews with overseas media as politically-motivated, and announced that he would go to court to challenge it. On April 9, around 9 p.m., Yang was assaulted by a group of unidentified men in front of the school complex where he resides. The men punched and kicked Yang, and took turns hitting him after he fell to the ground.

Yang sustained minor head and ear injuries that required stitches, and bruises on his back, chest, and arms. Yang called the police immediately after the attack, but the police officer declined to send a patrol, requiring him to come first to the police station to report the case even before seeking medical attention. Yang was bleeding and went to the hospital first. When the head of the police station was contacted by a journalist from Voice of America's Mandarin service, he denied knowledge of the attack, stating that, "Last night, nobody came to report such a case."[114]

In August 2006, Yang traveled to Shandong province to attend Chen Guangcheng's trial. The local police apprehended him before sending him back to Guangxi, where he was detained for a few days by the police.[115]

Tang Jingling, Guangzhou

Tang Jingling's case provides another example of physical attacks on and intimidation of lawyers by unidentified agents at the very time that judicial authorities are pressuring the lawyers to drop sensitive cases. Tang, a lawyer from Guangzhou who gained prominence in participating in a notorious case of counterfeited medicine, known as the "qi er yao" case, was working with rights activist Guo Feixiong on a number of election recall cases, including in Taishi, Guangdong.[116]