(Istanbul) – The trial on April 13, 2015, over the biggest mine disaster in Turkey’s history is a first step towards justice for the victims, Human Rights Watch said today, but full accountability for the disaster requires an investigation of state responsibility for failure to protect workers’ right to life.

The criminal case is against the director of the Soma Eynez mine company and 44 company employees and engineers for the fire on May 13, 2014, at the Soma Holding Eynez coal mine in western Turkey that resulted in the deaths of 301 miners from carbon monoxide poisoning and injured at least 162 others. Human Rights Watch interviewed numerous survivors of the disaster and families of miners who died, many of whom expressed concern about the lack of effective government oversight for safety problems and work conditions at the mine.

“The Soma trial of mine company employees offers victims a chance to get some measure of justice, but the trial does not address the responsibility of state agents who failed in their duty to protect mine workers’ lives,” said Emma Sinclair-Webb, senior Turkey researcher at Human Rights Watch. “The government’s role in the Soma disaster needs to be investigated and corrected if Turkey is going to be able to reverse its terrible record of preventable mine accidents.”

The criminal investigation into the mine disaster revealed compelling evidence of dangerous working conditions and inadequate infrastructure. Prosecutors found that the mine company had been informed of but apparently ignored clear warning signs of dangerous gas (firedamp) levels and rising heat in the mine, all of which contributed to the deaths.

Soma miners and relatives of miners who died in the accident described to Human Rights Watch the working conditions at the Soma Eynez mine in the years before the disaster. They cited a pattern of ineffective inspections; lack of implementation of health and safety standards; and infrastructure, equipment, and materials inadequate for the large number of mine workers. Those interviewed repeatedly noted the mine company’s emphasis on maximizing production of coal, apparently at the expense of safety.

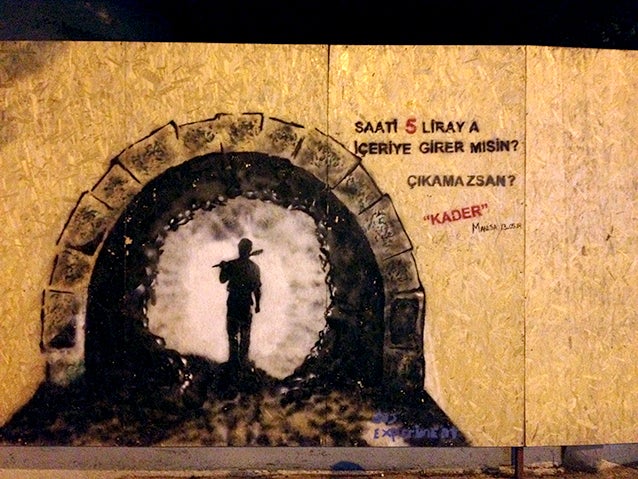

“The prime minister called the accident fate, said it was in the nature of the job, but they won’t make any of us see it that way,” said one retired miner whose son died in the disaster. “It was a massacre. It could have been prevented, and the state is protecting itself.”

The trial in the Akhisar Heavy Penal Court includes charges ranging from “killing with probable intent” to “criminally negligent manslaughter” and “constructive manslaughter.” The defendants include managers and senior technical personnel as well as the head of the board of the company. Eight of the defendants are in pretrial detention.

But the ministers of labor and social security and of energy and natural resources withheld permission to pursue a criminal investigation against officials. They were able to block an investigation based on a controversial law which states that prosecutors need administrative permission to investigate state officials for offenses committed in the course of their public duties.

“It is deeply troubling that the government can block prosecutors’ investigations into state officials for criminal wrongdoing by invoking an old law on administrative permission,” Sinclair-Webb said. “The European Court has in the past raised concerns that this law contributes to impunity for crimes by public officials and urged Turkey to repeal it.”

The Soma mining disaster has starkly exposed Turkey’s harsh and illegal working conditions in mining and other hazardous industries. In August 2014, 18 miners also died in a mine accident in Ermenek, in southern Turkey, and deaths on construction sites occur frequently. The most recent combined official statistics from Eurostat and Turkey’s Social Security Institution in 2011 reveal that the number of deaths in workplace accidents in Turkey was 15.4 per hundred-thousand workers as compared with 2.6 in the 28 EU countries. Mine accidents represent a significant proportion of those deaths in Turkey.

Turkey’s laws and regulations pertaining to mining stipulate health and safety standards and hold government ministries and state institutions responsible for regular inspection and oversight. But the Soma disaster has revealed the shocking lack of implementation of laws and standards to protect workers, Human Rights Watch said.

“When it comes to mining and other hazardous work, the government duty to uphold health and safety in the workplace is a right-to-life issue,” Sinclair-Webb said. “So it is all the more critical for the government to meet its obligation to investigate and hold to account state agents responsible for the Soma disaster. New regulations are not enough.”

The Search for Justice

Human Rights Watch conducted interviews in the towns of Soma and nearby Kınık and interviewed families of four mine workers who died in the May 13 disaster, nine Soma mine workers, a trade unionist, a lawyer, and a human rights activist. Two of the miners did not want to be identified at all out of concern that they might not get jobs again for speaking out. Others are identified here by their initials.

Relatives of miners who died described their search for justice and of the difficulty of coming to terms with the loss of sons, brothers, and husbands. Their political outlooks varied but their analysis of the causes of the disaster was consistent and matched the findings in the expert report.

A recurring element of their accounts of the disaster and rescue effort was their concern that the mine and its managers prioritized high productivity over obligations to uphold the health and safety of the workforce, and that the state authorities charged with oversight and inspection were fully aware of the situation but ignored it.

Those interviewed cited a lack of precautions to limit dangerous conditions, a lack of implementation of safety standards, and a lack of training for the miners. Above all, they said there was a lack of effective inspections that might have compelled the mine company to address dangerous working conditions and to uphold its legal obligations to protect workers’ health and safety.

Many also were highly critical of other aspects of mine operations in Turkey, such as subcontracting systems, and said that the Mineworkers Union of Turkey (Türkiye Maden İşçileri Sendikası) had failed to defend their rights at the Eynez mine. Both issues were outside the scope of this research.

Almost one year after the disaster, all of those interviewed in Soma and Kınık expressed feelings of hopelessness and depression, with many saying they had problems sleeping and a loss of interest in life. T.Ç. reported having flashbacks:

There are so many life stories, the story of two brothers who each thought the other was in the mine and went in to rescue the other one. The two died there. Can you imagine? There’s the story of a father and son – and I found them myself. The son had been on the shift and the father went in to find him and save him. He died there too, father and son lying dead with their arms wrapped around each other. For years we saw coal pour off that conveyor belt until the day came when it was our friends’ bodies that were coming off the belt. When I see the conveyor belt I suddenly remember that; I am overcome sometimes. How many times I remember it all every day. Sometimes just from a smell, the smell of death in a glass of water. I can suddenly find myself there again.

Families and wives of miners insisted that all those responsible for the conditions that led to the disaster should be brought to justice. At the same time, none of those interviewed had much confidence in the justice system. I.Ç. said:

The prime minister called the accident fate. He said it was in the nature of the job. But they won’t make any of us see it that way. It was a massacre. It could have been prevented and the state is protecting itself. We will do everything to see the state put on trial as well…430 children are without fathers now. Those who wrote reports giving the mine a clean bill of health should be tried. The ministers should have resigned.

N.K., the wife of a miner who died, said:

Is human life so cheap? We didn’t just lose 301. The whole society here has been left with a deep wound. I waited five days for an identification of my husband’s body from DNA tests. Why is the state protecting the inspectors and not letting them be put on trial? I want to see the state take responsibility for this. Our children are without fathers. I have little confidence in justice in Turkey. As well as my husband last year, seven years ago I lost my brother in a mine accident. No one got a prison sentence. And my aunt’s husband also died in a mine accident before that. There is never justice here.

Forcible police dispersal of protests in Soma to seek justice and the negative attitude of authorities had compounded the sense of injustice. One protester, A.S., said:

We did a two-week sit-in in a park last June, and the police and district governor (kaymakam) told us to get up and that it was a crime, and they detained us. The state commits a crime itself and gets away with it, but when I stand up for my rights, use my democratic rights, I am said to be committing a crime. They use the laws to protect themselves. They don’t give permission to investigate their inspectors for a crime, but they investigate me for a sit-in.

Another miner, E.Ç., said:

I never saw a water cannon vehicle in Soma before May 13. Why bring water cannon? Let people live their pain. We had a demonstration in Soma and blocked the traffic. We did no harm to anyone, not to any shopkeeper or any state institution, and for that the police beat us with batons and teargassed us. In this country you can’t demand your rights, there’s no such thing as demanding rights. If you do it you are deemed the guilty party.

One of the miners, who did not want to be identified, expressed reluctance even to lodge a compensation claim:

I very much want to speak out but I can’t because I am afraid I won’t get work. I got out eight hours after the fire started. We got over that, but now they have ended our work, and we don’t have compensation. Because we joined demonstrations, we may not get work. But we have to work.

All of those interviewed emphasized the enormous pressure placed on the miners to maximize output and the harsh work conditions. F.Ç. was not on the daytime shift on May 13 but rushed to the site when he heard about the fire, knowing his two brothers were both down the mine. He would never see them alive again:

When I once complained about the heat to the chief, he just said, “Is there coal on the conveyor belt, is there output? Forget the rest.” I spent more time crawling on the ground through those narrow passages on my belly than I did during military service. I used to get very angry sometimes about the pressure we were put under. The chiefs were given incentives to produce more but we didn’t see the benefits.

A.S., who was also not at work that day, emphasized the continuing risks:

I think another such tragedy could happen and will happen at one of the mines still open. I think we should put a camera down the mine by the conveyor belt to show the working conditions, to show how the conveyor belt works, to show how people are treated like animals being herded into a barn. There are very hard work conditions down there…The pressure on people in other mines continues. Just imagine that mining is based on planned projects that specify how many people are going to work in the mine. But whatever the project specifies, it’s not like that in practice: because they want to increase productivity they add more people. If it says you have to have five, you’ll find 20 men; if the project says 1,000, you’ll find 3,000.

S.K. worked as a safety officer at the mine but said the mine’s work regime meant he could barely act as one:

There was continually pressure from above so that they would never agree to stopping work to fix things, as it would have interrupted production…On paper there were safety standards but they were never implemented. For instance, a sign saying “Don’t clean the conveyor belt while operating” hung by the conveyor belt but we always had to clean it while it was operating because the company never wanted to halt production.

In 2013, S.Ç.’s left arm got caught in the conveyor belt, leaving him with permanent damage and ending his working life as a miner. His claim against the mine for compensation is ongoing, and he expressed the enormous frustrations that many workers in Turkey experience because of the obstacles they face in securing legal redress for workplace accidents.

Workers also said that the gas masks they were provided were never inspected, repaired, or replaced. E.Ç. said he had the same mask from 2006 to 2014, without it once being examined. “In 2010 there was a fire at the mine as a result of an electrical fault,” he said. “We had to use the gas masks and half of them turned out not to work.” During the May 2014 fire, some masks failed to be effective against the carbon monoxide.

T.Ç. and several others also said that if miners opened theirs masks and used them unnecessarily or lost the mask, the company docked their wages at an inflated cost:

So you’d end up with 1,250 TL (US$486) at the end of the month instead of 1500 TL ($583). And yet we found out afterward that the masks cost just 30 TL. How do you describe that kind of treatment?

The miners Human Rights Watch interviewed repeatedly focused on the lack of proper inspections. F.Ç. said:

If an inspector came, they gave the company notice of their visit well beforehand. Then we had to clear up before they came. The company wouldn’t show the inspectors the very low passages where you had to crawl on the ground. I never saw an inspector in the mine.

E.Ç. said:

Back in March 2011 Labor Ministry inspectors came to the Eynez mine and gathered all the employees and gave us a talk about introducing safety standards as good as the EU’s and making sure not a single worker got injured. The employers stood there saying nothing. I couldn’t stand it and got angry, got up alone and congratulated the inspectors, then said: “But tell me, will you make that a reality in practice? In Turkey, in the private sector, there is no such practice, let’s not kid ourselves.” They assured us they’d stay in Soma a year to implement standards and, if necessary, to impose penalties on the company. But just five months later a friend of ours dies on the job. No one came. The inspectors don’t go underground; they inform the company of their visit 20 days beforehand. Such an inspection isn’t an inspection.

A.A. said:

There are a lot of accidents just because of the lack of oversight and inspection and no investment by private companies in mines.

The Soma Eynez Mine

The Eynez mine was formerly state-run but, in 2006, the state began to lease the mine to private companies to run. The license to run the mine belongs to the Coal Mining Board of Turkey (TKİ), a nominally autonomous body connected with the Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources. In 2006 the board leased the mine to a private company, Park Holding, which reported great difficulties in running the mine because of fires and, in late 2009, applied to discontinue its contract. In 2011 the mine was leased to another private company, Soma Coal Mining, part of the Soma Holding group.

The single client for the lignite coal from the Soma Holding Eynez mine is the state, and the head of Soma Holding stated in a 2012 newspaper interview that his company had succeeded in reducing the cost of coal from $130 to $24 per ton. Soma Coal Mining more than doubled predicted production at the mine in 2013.

After the May 13 disaster, Soma Coal Mining closed the mine where the fire occurred and two other nearby mines. On November 30, 2014, the company laid off 2,181 miners at the Eynez mine and miners at the other two mines that it closed. While some miners have found employment at other mines in the area, the majority remain unemployed. They are entitled to unemployment benefits for just six to eight months.

Mine Safety Concerns and State Responsibility

A 2011 report into mine safety nationwide by the State Inspectorate Board of the Presidency raised detailed concerns and made concrete recommendations about overhauling the sector to improve safety standards. Reports on the Soma mine disaster by Turkey’s Ombudsman Institution, by a parliamentary commission, and by the Turkish Union of Bar Associations all raised grave concerns about dangerous working conditions and the multiple failures of oversight that led directly to the disaster.

In September 2014, parliament passed a law to improve work conditions in mining, reducing the working day from eight to six-hour shifts (with a maximum 36-hour working week), increasing pay, and lowering the retirement age from 55 to 50. The law also stipulated that the state would pay off the debts of families who had lost members in the mine accident and provide employment for one individual in each family, although reportedly this has not yet been implemented.

In March 2015, Turkey ratified the International Labour Organization Safety and Health in Mines Convention (no. 176). Ratification was a positive move, but it will add little to the existing law on the books. The problem is not Turkey’s laws but lack of implementation, Human Rights Watch said.

Turkey’s laws and regulations assign responsibility to a wide range of authorities for ensuring adherence to appropriate technical standards of construction, engineering, maintenance, and practices in mines to ensure occupational health and safety – and for the regular and effective oversight of those standards and practices.

In addition to Labor Ministry inspectors, the agencies involved include the Coal Mining Board of Turkey (TKİ) and its directly affiliated regional office in Soma, Aegean Lignite Operations (Ege Linyitleri İşletmesi Müessesi Genel Müdürlüğü, TKİ-ELİ), and the Mining Works General Directorate (Maden İşleri Genel Müdürlüğü, MİGEM) attached to the Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources.

Government Blocking Investigation into State Responsibility

The prosecutors’ expert report on the Soma mining disaster holds state inspectors and other civil servants responsible for the mine deaths alongside the mine company and its personnel. However, the minister of labor and social security and the minister of energy and natural resources have both refused permission for a criminal investigation that could lead to the criminal prosecution of state officials.

The expert report found that officials had failed in oversight duties in numerous ways. For example, they failed to compel the mine company to replace an air ventilation system that was insufficient for the number of workers employed at the mine and thus contributed to the high number of deaths during the disaster; and over several years prior to the disaster they failed to ensure implementation of health and safety standards in spite of a greatly increased rate of production that should have alerted them to potential safety problems.

Protesters at a May 15, 2014 demonstration in Ankara criticize the Turkish government for the Soma mining disaster. The banner reads, "Not an accident, not fate, it’s murder!" © 2014 Reuters

In March 2014, two months before the disaster, the record of one government inspection report that Human Rights Watch obtained concludes that over a four-day inspection “no flaw was identified.”

Faruk Çelik, the labor and social security minister, has publicly defended his position:

The prosecutor wanted permission from us for the Soma investigation. I didn’t give it, and why? The perpetrator of the incident was represented as […] my general director of occupational health and safety. He was the man who prepared the law on workers’ safety, so how could he be involved? And they wanted the list of all names of inspectors who had undertaken inspections since 2009 on the grounds that the mine was given its license at that date. But there have been no accidents till this date [May 2014] so why would you want the inspectors’ names. Of course I didn’t accept it. It seems to me ideological to want permission for [investigating] people who were not involved in the incident.

Çelik said that the ministry would conduct its own administrative investigation into two employees instead of agreeing to a criminal investigation, and contended that the disaster was the result of the mine’s outdated structure.

Human Rights Obligation to Conduct a Criminal Investigation

Turkey is a party to the European Convention on Human Rights. The European Court of Human Rights has held, time and time again, that as part of the obligation to protect the right to life in circumstances such as the loss of life at Soma mine there must be an effective investigation capable of identifying all of those responsible with a view to their punishment. The court has emphasized that “any deficiency in the investigation which undermines its ability to establish … the person or persons responsible will risk falling foul of this standard.”

The ministries’ decisions to withhold permission to pursue a criminal investigation of state agents is based on one of Turkey’s most controversial old laws, on the prosecution of civil servants and other public officials (no. 4483). The law stipulates that prosecutors have to secure administrative permission to investigate state officials with a view to prosecuting them for offenses committed in the course of their public duties.

The European Court of Human Rights has repeatedly criticized Turkey for this law on the grounds that state authorities have used it effectively to shield public officials from criminal prosecution and to avoid holding them accountable for serious crimes or abuse of power. Law no. 4483 directly undermines the effectiveness of any investigation, contrary to Turkey’s human rights obligations and its duty to provide victims with an effective remedy, Human Rights Watch said.

In December 2014 Turkey’s highest administrative court, the Council of State, ruled that the labor and social security minister’s decision to withhold permission for a criminal investigation into the ministry’s own inspectors was based on an “insufficient assessment.” The court said the Ministry should conduct a full evaluation of the evidence in the expert report before determining whether to grant permission. This court decision sends the strong message that the ministry should permit an investigation, although it makes no explicit instruction to that effect.